Abstract

Among the general population, frontline workers have been identified to be at heightened risk for negative mental health consequences related to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Catholic priests, who minister to approximately 30% of Canadians, in their role as frontline workers, have been profoundly limited in the provision of pastoral care due to public health restrictions. However, little is known about the impact pandemic distress has on this largely understudied population. Four hundred and eleven Catholic priests across Canada participated in an online survey during May and June 2021. Multiple regression analysis examined how depression, anxiety, traumatic impact of events, loneliness, and religious coping style affect the psychological well-being, satisfaction as a priest, and priestly identity of participants. Results demonstrated that pandemic distress significantly impacts the psychological well-being of priest participants. Depression and loneliness surfaced as significant considerations associated with lowered psychological well-being. While neither anxiety nor traumatic distress reached a significance threshold, the religious coping style of participants emerged as an important factor in the psychological well-being of priests. Results of the study contribute to the understanding of how the pandemic has impacted a less visible group of frontline workers.

1. Introduction

Since the World Health Organization declared the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) a global pandemic on 11 March 2020 (Cucinotta and Vanelli 2020), the Government of Canada, as well as provincial governments, implemented a wide range of stringent emergency public health measures to mitigate the spread of the disease. By the end of March 2020, all Canadian provinces and territories had declared either a State of Emergency or a Public Health Emergency (Canadian Civil Liberties Association 2021). Among other measures, travel restrictions, stay-at-home orders, mandatory physical distancing, suspension of non-essential services, directives regarding the use of personal protective equipment (PPE), and restrictions or suspensions of public gatherings were imposed on the population at large. These restrictions substantially altered people’s lives (Dozois and MHRC 2021) and mental health experts raised a critical awareness about an impending “echo pandemic of mental health problems” (Favaro et al. 2020, p. 137).

Internationally, studies have highlighted an increase in mental health needs (Holmes et al. 2020), as well as decreased quality of life (Shamblaw et al. 2021). A 2020 survey conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO 2020) indicated that “bereavement, isolation, loss of income and fear are triggering mental health conditions or exacerbating existing ones”. Levels of anxiety, depression, self-harm, and suicide attempts have increased during the pandemic (Holmes et al. 2020), with 45% of North American adults reporting stress and worry related to the pandemic is negatively affecting their mental health (Panchal et al. 2021). A COVID-19 resilience survey, conducted online on behalf of the American Psychological Association in August 2021 with more than 3000 adults living in the United States, indicated that “nearly one-third of adults (32%) said sometimes they are so stressed about the coronavirus pandemic that they struggle to make basic decisions” (APA 2021, p. 2).

In Canada, a number of studies have underscored the negative impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the mental health of Canadians. Among them, conducting a national survey of Canadian adults, Dozois and MHRC (2021) found an increase in self-reported depression, as well as an increase in alcohol and cannabis use. Kutana and Lau (2021) found an increase in sleep disturbances. Best et al. (2021) reported on “increased psychological distress, including elevated levels of overall distress, such as panic, emotional disturbances, and depression” (p. 1).

Other research has been conducted with Canadian frontline healthcare workers. A nation-wide crowdsourcing survey, which was completed by approximately 18,000 health care workers, indicated that 70% reported their mental health was “somewhat worse now” or “much worse now” than before March 2020 (Statistics Canada 2021, p. 1). Among health care workers who worked in direct patient care with confirmed COVID-19 patients, 77% reported worsening mental health when compared to pre-pandemic conditions (Statistics Canada 2021). In an Ontario-based study, Maunder et al. (2021) highlighted a rising psychological burden and emotional exhaustion among health care workers, and Best et al. (2021) found symptoms of moderate to severe depression in 50% of their sample of Canadian frontline health care workers.

The Present Study

Catholic priests, responsible for providing support and accompaniment to approximately 30% of Canadian adults who identify as Catholic (Lipka 2019), address the pastoral and spiritual needs of their parishioners. Identified as another group of pastoral frontline workers, Catholic priests share in the commonly reported characteristics of frontline health care workers, who are often described as “brave individuals who accept the heightened importance of their jobs and the danger associated with them” (Sorensen 2021). The aim of this present study is to explore how the COVID-19 Pandemic has psychologically impacted Catholic priests across Canada.

Priests, in an effort to serve their parishioners, heard a heightened call to be proactive in their ministerial and pastoral response to the crisis, but the very possibility to do so was severely limited. The above referenced public health-related suspension or restrictions of public gatherings across Canada included public worship. As such, to varying degrees, priests were unable to celebrate Mass with their congregations in person; instead, livestream services became the permitted route of connection. Provision of essential sacramental services—such as baptisms, first communions, confirmations, weddings, funerals, reconciliation, and the Anointing of the Sick—were either rendered impossible or could only take place under limiting circumstances.

There is limited research available regarding the impact of the current pandemic on church life in the United States. A national survey of United States Catholic bishops, conducted in the Spring of 2020 by the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA 2020), found that the provision of ministry was “very much affected” in more than half of the participating dioceses. The survey also indicated a negative effect on the morale of priests and other ministerial staff. Similarly, in an Italian study, Crea et al. (2021) examined the increase in “emotional distress, anxiety, fear, depression, and psychosomatic symptoms” (p. 729) in Catholic priests and religious sisters during the current pandemic.

At the time of this present study, no research data were available regarding the current pandemic distress on Catholic priests in Canada. Thus, the purpose of this current study was to determine the extent to which the stressors of the COVID-19 Pandemic have impacted the psychological well-being of Catholic priests across Canada. Clinical observations with this population have indicated that, in addition to the experience of depression and anxiety, loneliness may be an important research variable, as increasing number of priests across Canada live alone. Furthermore, religious coping has emerged as an important variable in the psychological well-being of priests (Kappler et al. 2020). In addition, as a group, priests frequently associate their personal identity with their ministry and their capacity to engage in ministry. Since the pandemic limited priests’ ability to minister at pre-pandemic levels, professional identity was seen as another important variable for the psychological well-being of priests. Therefore, based on these considerations, the specific hypotheses for this study were defined as follows: H1: The psychological distress of COVID-19 (measured by combined scores on the IES-R, PHQ-9, GAD-7, UCLA Loneliness) will be negatively associated with the psychological well-being of priests in Canada (measured by scores on the PWBS). H2: The religious coping of priests (measured by scores on the RCOPE) will be positively associated with the psychological well-being of priests in Canada (measured by scores on the PWBS). H3: The distress of COVID-19 (measured by scores on the IES-R) will be negatively associated with the professional identity of priests in Canada (measured by scores on item 17.2 on the SDI Research Project Questionnaire). H4: The experience of loneliness (measured by scores on the UCLA Loneliness) will be negatively associated with the psychological well-being of priests in Canada (measured by scores on the PWBS).

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Procedure and Participants

Institutional approval to conduct this study was provided by the Institutional Review Board of The Southdown Institute. The researchers reached out to Catholic priests, both diocesan and vowed religious, assigned to ministry in a Canadian diocese or archdiocese or eparchy. Bishops/archbishops (local ordinaries) in all ecclesial regions of Canada were emailed a courtesy letter requesting formal permission to invite the respective priests to participate in this voluntary research study. Upon receiving the permission of 27 bishops/archbishops (local ordinaries), the identified diocesan contact person was emailed the formal research study invitational email, to be sent out by that contact person to his/her email list of priests. The priests were given the opportunity to open the personal email sent to them and decide to participate or decline participation. Priests who agreed to participate were provided with information about the study and the risks and benefits of completing the study. They were offered a list of support resources in case of increased distress as a result of completing the survey. Each participant was apprised of informed consent being implied if they chose to continue with the survey, before they proceeded to the anonymous online survey.

All identified email communications were sent in both an English and French language version, for each participating priest to choose. All psychological self-report questionnaires used in this study have published versions/editions in both English and French. One of the researchers, a first-language French speaker, composed the French language version of the study’s demographics self-report questionnaire, reviewed by another researcher, who has bilingual English-French fluency. The final English language version of the demographics self-report questionnaire was reviewed by The Southdown Institute’s quality control editor.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Predictor Variables

- Demographics. Participants were asked to provide demographic information. For the purposes of this study, the following control variables were retained: age (in six groups but treated as a continuous variable), first-generation migrant status (binary variable inferred through country of birth), diocesan versus religious-order priest (binary)1, rural versus (sub-)urban location of ministry (binary), region of residence (eight Canadian provinces and one residual category;2 all inferred through respondents’ location at time of survey), professional counseling in the year prior to survey (binary), spiritual direction during pandemic (binary), helpful activities undertaken during the pandemic (specifically, group activities, friendship-related activities, spiritual activities; all binary). As an additional covariate in the context of loneliness, the living situation (alone or in a group setting; binary) for 211 participants was elicited, despite the lack of direct question in the survey3.

- Religious Coping. The religious coping was measured by scores on the Religious Coping Scale–Brief Version (RCOPE), a 14-item self-report measure (Pargament et al. 2011) used to assess the positive and negative religious coping strategies of an individual in response to a negative event, on a 4-point rating scale, ranging from 1 (‘Not at all’) to 4 (‘A great deal’)4. In terms of internal consistency, positive RCOPE reached a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86, while negative RCOPE reached the value of 0.75.

- Psychological Distress. Depression was measured by scores on the Patient Health Questionnaire for Depression (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al. 2001), a 9-item self-report measure used to assess the severity of depressive symptoms on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (‘Not at all’) to 3 (‘Nearly every day’). The recommended cut-off score on the PHQ-9 is 10 (Manea et al. 2012). The scores on the PHQ-9 correspond to minimal (0–4), mild (5–9), moderate (10–14), moderately severe (15–19), and severe depression (20–27). The internal consistency for the PHQ-9 was 0.86.

Anxiety was measured by scores on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7; Spitzer et al. 2006). The GAD-7 is a 7-item self-report measure that assesses the generalized anxiety level on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (‘Not at all’, ‘Not at all sure’) to 3 (‘Nearly every day’) during the previous two weeks. The GAD-7 yields a total score ranging from 0–21 with the recommended cut-off score of 5 (mild), 10 (moderate), and 15 (severe) anxiety. The internal consistency for the GAD-7 was 0.90.

Distress was measured by scores on the Impact of Event Scale–Revised (IES-R; Weiss 2007), a 22-item self-report measure that assesses subjective distress caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic as the identified stressor within the past seven days, on a rating scale ranging from 0 (‘Not at all’) to 4 (‘Extremely’). The IES-R yields a total score ranging from 0–88, with the recommended cut-off score of 33, suggesting a probable diagnosis of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and 24–32 suggesting partial PTSD or clinical concern for PTSD. In addition to the total score, and in accordance with the scale documentation, the IES-R total mean score as the sum of its mean subscales (avoidance, intrusion, and hyperarousal) was computed. This total mean score ranges from zero to 12, and the IES-R total mean score was used in our regressions. Cronbach’s alpha for the IES-R total score was 0.94.

Loneliness was measured by scores on the University of California Los Angeles Loneliness Scale–Short Form (UCLA Loneliness; Hughes et al. 2004), a 3-item self-report measure used to assess the feeling of loneliness, ranging from 1 (‘Hardly ever’) to 3 (‘Often’). The scale reached a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.83.

2.2.2. Outcome Variables

- Psychological Well-Being. The psychological well-being of the priests in Canada was measured using the 42-item self-report version of Ryff’s Psychological Well-being Scale (PWBS; Ryff and Keyes 1995). The PWBS measures six aspects of well-being and happiness, namely autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance. The PWBS is assessed on a 6-point scale ranging from ‘Strongly Disagree’ to ‘Strongly Agree’. In our sample, Cronbach’s alpha for the PWBS was 0.90.

- Loss of Priestly Identity. As another measure of priestly well-being, a potential COVID-19-related loss of priestly identity (item 17.2 on the SDI Research Project Questionnaire) was elicited. This 1-item measure asked respondents to which degree they experienced distress related to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Specifically, participants had to rate the level of distress associated with a loss of aspects of priestly identity on a 5-point scale ranging from ‘Very mild’ to ‘Very severe’.

- Life Satisfaction as a Priest. An additional measure of priestly well-being, life satisfaction as a priest was assessed using a single item on the survey (item 26 on the SDI Research Project Questionnaire) by asking participants to respond to the question: How satisfied do you feel as a priest right now? This was scored on a 5-point scale ranging from ‘Not at all satisfied’ to ‘Extremely satisfied’.

3. Results

3.1. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using Stata as the statistical software. The two maps (Figure 1 and Figure 2) were created using the Stata MAPTILE package (Stepner 2017). All main results are based on multiple regression analysis using ordinary least squares (OLS). Multiple regression is the tool of choice for a non-causal analysis of survey data with an adequate sample size. An exploratory analysis of the psychological well-being of priests was conducted. OLS is particularly appropriate in this context as it allows a comparison of the strength and significance of the relationship between different aspects of COVID-19-related distress and well-being across different model specifications. Additionally, the regression coefficients are readily interpretable in a quantitative way, which immediately adds to the understanding of the psychological significance of each relationship between a facet of COVID-19-related distress and well-being. Simple bivariate correlations or other descriptive analyses come with an important caveat in such an exploratory setting: Demographic variables as well as context-relevant behaviors may well affect both the regressor of interest (IES-R, GAD-7, UCLA Loneliness, PHQ-9, and RCOPE, respectively) and the outcome of the regression (PWBS), leading to omitted variable bias. OLS allows for easy and explicit inclusion of a number of pandemic-related behaviors (e.g., helpful activities) and key demographic information (e.g., age and location) as control variables.

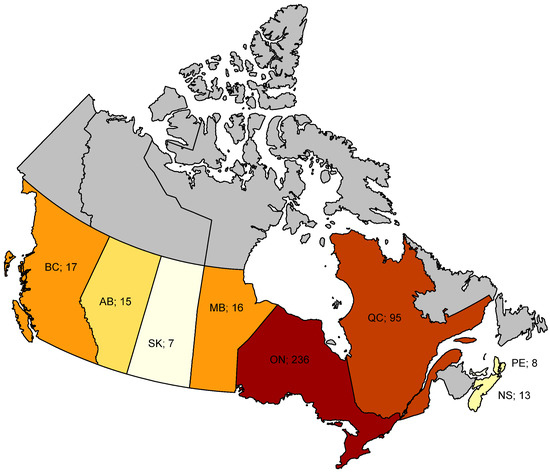

Figure 1.

Number of respondents by province. The figure shows the number of survey participants for each Canadian province with more than five participants. It includes respondents who did not complete the entire questionnaire.

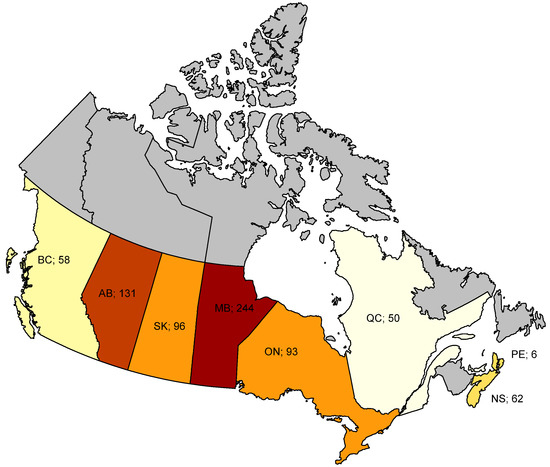

Figure 2.

COVID-19 incidence by province. The figure shows the COVID-19 incidence for calendar week 20, 2021, for each Canadian province with more than five participants. Source: Public Health Agency of Canada (2021).

While all potential sources of bias cannot be fully eliminated—and, thus, results cannot be interpreted as causal effects by any means—the rich set of individual-level controls is adding immense value to the simple bivariate relationships. In the preferred specifications, region fixed effects were introduced, thereby only comparing priests within the same part of Canada (Figure 1 provides an overview of the number of participants by Canadian province). This is particularly relevant in the context of the pandemic, since both regulations and incidences (Figure 2)—that matter for the severity of the distress experienced by the priests—vary at the regional level. The specific restrictions relevant for the priests’ pastoral well-being varied at the provincial level and are depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

COVID-19 restrictions by province. The figure shows the level of ‘normal’ operations permitted in each respective province for May 2021. Level 1: No public mass. Level 2: Public mass at 10–30 people. Level 3: Public mass at 50% capacity. Source: Information gathered from Church authorities in participating provinces.

In all regression tables, bivariate (‘raw’) relationships between outcome and regressor of interest are augmented by a step-by-step introduction of control variables and region fixed effects. Since there are not enough regions in Canada to allow for region-level clustering, heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors (HC3) were chosen and are reported in parentheses. Sample size is kept constant within each table. For expositional purposes, the regression constant and fixed effect coefficients are omitted in all tables. Table notes contain further information on all variables included in each model.

3.2. Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics of the analytical sample. Panel A shows mean, standard deviation, and the number of non-missing observations for key variables. Panel B shows the raw correlations between all psychological measures used in the study. The sample was comprised of 411 Catholic priests, of whom approximately 80% were diocesan priests and 20% vowed religious priests. A little over half of the group were above 60 years of age (54.74%), followed by those who were between 40 and 59 years old (35.04%), and 10.22% who were below age 40. The sample was predominantly of European ethnic descent (79.20%) and 20% self-identified in the group consisting of Asian, African, Latino, Middle Eastern, and Indigenous/First Nation origin. The sample was predominantly well-educated, with 66.42% of participants holding a master’s degree, and 17.27% holding a doctoral or professional degree. Twenty-eight percent of respondents were first-generation migrants and 27% were based in a rural location. Sixty-five percent of priests had received spiritual direction during the pandemic, while only 9% had received professional counseling in the 12 months prior to the survey. Sixty-two percent reported spiritual activities as being helpful during the pandemic and 56% reported helpful friendship activities, while only 27% reported helpful group activities.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

3.3. Hypothesis Testing

According to Hypothesis 1, the psychological distress of COVID-19 will be negatively associated with the psychological well-being of priests in Canada. Table 2 contains our main results on COVID-19-related well-being among Canadian priests. It evidences the relationship between the various non-religion-specific psychological scales and the psychological well-being score in a linear regression framework. As these regressions rely on survey data and do not exploit any exogenous variation in the determinants of psychological well-being, our results cannot be interpreted as causal effects. However, due to the large number of controls in the more sophisticated specifications, meaningful correlations were uncovered by holding constant some of the most substantial confounders.

Table 2.

Aspects of COVID-19 distress and psychological well-being.

First, columns (1) through (4) show the raw bivariate relationships between the PWBS score and, respectively, the IES-R scale, the PHQ-9 scale, the GAD-7 scale, and the UCLA Loneliness scale. As expected, all four scores are strongly negatively related to psychological well-being. These negative coefficients are very precisely measured and therefore statistically significant at the 1% level with heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors. In particular, the IES-R shows a large coefficient. If the IES-R total mean score (as measured by the sum of the means of the three subscales) increases by one point, the PWBS score decreases significantly by approximately 5.4 points. This amounts to a 3% decrease relative to the 195-point average of the PWBS score in our sample. This seemingly strong relationship did not survive in the richer specifications. Analogously to the IES scale, an increase in the depression (column 2), anxiety (column 3), and loneliness (column 4) scores by one point is associated with a significant decrease in well-being, by 3.1, 2.6, and 5.6 points, respectively.

The picture changes once all four scores were included simultaneously in column (5) to assess their relative importance. Now, only the coefficients on depression and loneliness remain (highly) significant, even though, in absolute terms, both decrease in size. It appears that depression and loneliness are more predictive of psychological well-being in the context of the pandemic than the impact of event score in itself. The high R-squared of 0.30 in column (2) compared to columns (1), (3), and (4) suggests that this finding is mainly driven by the high predictive power of the depression scale.

Specifications in columns (6) and (7) confirm this main finding when control variables and fixed effects were introduced. In the absence of experimental variation in the independent variables, some of the most obvious potential confounders of the relationship between our psychological distress scores and psychological well-being of priests scores were accounted for. These controls include simple demographics (e.g., age or rural location) as well as pandemic-related behaviors (e.g., helpful activities). Importantly, region-fixed effects were introduced in column (7). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on personal well-being likely depends on the specific rules, regulations and, most notably, incidence in the region of residence (see Figure 2 for the regional incidences at time of survey). The introduction of region fixed effects allows to only compare priests who reside in the same Canadian province and are thus exposed to similar pandemic-related circumstances. While the regional fixed effects do not add much predictive power, their introduction is conceptionally important in an epidemiological context. Keeping our major control variables as well as the region of residence constant in our preferred specification (column 7), once again the depression score was found to be most strongly related to psychological well-being. A 1-point increase in the PHQ-9 score is associated with a highly significant decrease in individual well-being of a priest by 2.7 points, which corresponds to a decrease by 1.4% of the average PWBS score in the sample.

The only other significant psychological distress score comes from the UCLA Loneliness scale. According to the specification in column (7), psychological well-being decreases by roughly two points when the loneliness score increases by one point. However, this coefficient is only significant at the 5% level and somewhat sensitive to the choice of control variables. Out of these control variables, only the dummy variable indicating whether a priest has been involved in helpful spiritual activities during the pandemic is consistently significant (at the 5% level), and it was found to be positively related to psychological well-being.

Overall, our preferred model—column (7) of the regression table—can explain 36% of the total variation in the PWBS score. Rather than the IES-R scale in itself, it seems to be the depression and loneliness scores that are most predictive of the psychological well-being of Canadian priests in the context of the pandemic.

Hypothesis 2 stated that the religious coping of priests (measured by scores on the RCOPE) will be positively associated with the psychological well-being of priests in Canada (measured by scores on the PWBS). The results reported in Table 3 support this hypothesis with respect to positive religious coping behavior (positive RCOPE) and call for a nuanced interpretation of the different RCOPE subscales. A 1-point increase in the positive RCOPE scale is associated with an increase in the PWBS score by approximately one point. While this result is highly significant, it is substantially smaller in absolute size than the impact of negative religious coping behavior (negative RCOPE). For a 1-point increase in negative religious coping, psychological well-being decreases by approximately four points, which corresponds to 2% of the PWBS mean. Notably, in addition to spiritual activities, age- and friendship-based activities are also significant at the 5% level once they were included in the model together with the RCOPE measures. Both age and helpful activities are positively related to psychological well-being when we keep religious coping mechanisms constant. Overall, Table 3 suggests that religious coping is important for the psychological well-being of priests in Canada. However, the influence of negative religious coping is significantly more powerful in size than the influence of positive coping.

Table 3.

Religious coping and psychological well-being.

Hypothesis 3 posited that the distress of COVID-19 (measured by scores on the IES-R) will be negatively associated with the professional identity of priests (measured by scores on item 17.2 on the SDI Research Project Questionnaire). Indeed, Table 4 shows a positive relationship between the distress of COVID-19 and the degree to which a loss of priestly identity was experienced. Specifically, a higher IES-R score is associated with a greater loss of identity, supporting Hypothesis 3. The coefficients seem small in size (though high in significance) at first glance. However, in column (3), an increase in COVID-19 related distress by one unit (i.e., an increase in the total mean score by one point) is associated with an increase in reported priestly identity loss by approximately 0.23 points on the respective Likert scale, which corresponds to a sizeable 10% of the outcome mean. Exploratively, self-reported satisfaction as a priest (as measured by score on item 26 on the SDI Research Project Questionnaire) was investigated as an additional outcome in columns (4) through (6). As expected, pandemic-related distress, as captured by the IES-R, is significantly negatively related to general satisfaction as a priest. In addition to the COVID-19 distress, the coefficients on spiritual activities and counseling are also significant in predicting overall satisfaction. Priests who engage in spiritual activities during the pandemic score higher on satisfaction, while priests who received counseling in the 12 months prior to the survey score significantly lower. Due to missing values in both outcome variables, the sample size is lower than in previous tables.

Table 4.

COVID-19 distress, identity, and general satisfaction.

Finally, Hypothesis 4 proposed that the experience of loneliness (measured by scores on the UCLA Loneliness) will be negatively associated with the psychological well-being of priests in Canada (measured by scores on the PWBS). Table 2 already provided relevant insights here by showing a negative relationship between loneliness and well-being, even when other scales and controls are included. Table 5 adds to this evidence by analyzing loneliness in combination with aloneness. For 211 survey participants, their living status (either alone or in a group setting) was inferred. While the dummy variable indicating whether a priest lives alone does not significantly predict the well-being score by itself (column (2)), the coefficient turns significant once the UCLA Loneliness measure (which in itself remains almost unchanged in terms of coefficient size) was added: Loneliness is strongly negatively associated with well-being throughout all specifications. However, when loneliness was kept constant, living alone became positively related to well-being of priests. With other conditions remaining the same, priests who live alone scored 8.5 points higher on the PWBS measure, which corresponds to 4% of the PWBS mean. It appears that differentiating between living alone versus living in loneliness is crucial for the assessment of psychological well-being among priests in Canada.5

Table 5.

Loneliness, living alone, and psychological well-being.

4. Discussion

Based on data from an online survey of 411 clergy participants, this study sheds light on the impact of distress from the COVID-19 Pandemic on the psychological well-being of Catholic priests across Canada. While much research has been devoted to the impact of pandemic distress on various population groups, particularly first responders and frontline workers, this present study was the first one conducted in Canada with a focus on Catholic priests, who can be considered pastoral frontline workers, who serve a large segment of the Canadian population.

The data were collected in May and June of 2021, during a time when Canada was in a phase in which it reacted to the second and third waves of COVID-19 infections (Detsky and Bogoch 2021) as reported in Figure 2, which illustrates the province-specific relevant pandemic data.

In the study, we found support for Hypothesis 1, that the psychological distress of the COVID-19 Pandemic is having a negative association with the psychological well-being of priests in Canada. However, the impact of anxiety and traumatic distress were not significantly related to well-being once other psychological measures were controlled for, while depression and loneliness surfaced as the major factors which lessened the psychological well-being of priests. This result was partially a surprise, as one would expect the cluster of worry and anxiety to negatively impact psychological well-being even in the presence of other measures and various control variables. Since the data collection occurred 13 months into the pandemic, it could be argued that the initial worry, stress, and anxiety that may have been present at the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, may have subsided by that time. Priests, like other population groups, may have had time to adjust to living with the crisis and restrictions. This corresponds to clinical observations with many clergy members reporting struggling initially with the learning curve of how to meaningfully connect with parishioners via virtual/online means, as in how to livestream services and conduct webinars to maintain pastoral care. The findings of this study are partially supported by recent studies that reported an increase in anxiety and depression as a result of the COVID-19 Pandemic (COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators 2021; Prout et al. 2020). The fact that anxiety did not emerge as a significant negative contributor to Canadian priests’ mental health in this study may be related to priests’ job security, during a time when other populations feared for the loss of their employment. In other words, while the capacity to meaningfully minister was profoundly affected, priests as a group did not share in a major source of anxiety, namely job loss or being placed on employment leave. In addition, the questions asked on the IES-R aim at a particularly traumatic event and measure an individual’s hyperarousal and avoidance in response to the event, as well as the level of intrusive thoughts related to the event. Again, by the time the data were collected, participants were 13 months into the experience of being exposed to an ongoing, stressful event. The wording of the questions on the measure elicits answers to a singular and specific event, and it may be the case that priests in their responses did not classify the ongoing level of distress as fitting questions seemingly aimed at a singular event. The fact that depression, as measured on the PHQ-9, was significantly associated with lessened psychological well-being reflects the more chronic nature of the distress, resulting in classic symptoms of depression, such as fatigue, hopelessness, sadness, difficulties sleeping, difficulties concentrating, loss of appetite, and loss of energy.

Loneliness emerged as the second aspect of the pandemic distress that was negatively associated with the psychological well-being of priests, which is a significant finding as Catholic priests by nature of their priestly promises live in chaste celibacy, foregoing a partnered or married life. In addition, slightly more than half of the priest participants lived alone at the time of data collection, and further aspects of a potential difference between loneliness and aloneness are discussed later, when Hypothesis 4 is reviewed.

The results of our survey affirm Hypothesis 2, that the religious coping of priests will be positively associated with their psychological well-being. Indeed, on review of the subscales of religious coping, it emerged that the data on positive religious coping aligned with previous research by Wilt et al. (2019), positing that positive religious coping built on a belief in “a personal, relational God, seeing God as an active partner in the resolution of problems” (p. 284) is generally associated with improved well-being. Conversely, the data on negative religious coping builds on a tenuous relation to the sacred and an ominous view of the world and is generally associated with worsened well-being (Pargament 2001). This implies that priests who engaged in a more negativistic coping, viewing their relationship to God as distant, or sensing an abandonment by God in the midst of crisis, had significantly lessened psychological well-being when compared to those who engaged in a coping style that viewed God as accompanying them in a benevolent and close manner in the midst of crisis. A closer examination of the items that build negative coping on the RCOPE may shed some light. Priests with mainly negative religious coping style endorsed, for example, some or all of the following items: (a) Wondered whether God had abandoned me, (b) Felt punished by God for my lack of devotion, (c) Wondered whether my Church has abandoned me, and (d) Questioned God’s love for me. These items reflect an individual’s struggle with positive self-appraisal, a sense of rejection or abandonment, a lacking sense of agency, and an absence of hope, which all are contributing elements of depression. This finding also has important implications for the initial and ongoing spiritual formation of priests, as negative religious coping styles could be assessed, addressed, and improved upon. Results also indicated that age and both spiritual as well as friendship activities were positively related to psychological well-being when religious coping mechanisms were kept constant. This result speaks to the importance of engaging in helpful activities as an important factor in achieving improved mental health. Previous research has consistently listed staying active, both physically as well as mentally (Mayo Clinic 2021), as an essential coping strategy in times of distress. Priests who engaged in actively seeking out support through friendships as well as spiritual activities had more positive well-being than those who remained inactive. The results suggesting that older priests had better overall psychological well-being, when compared to younger priests, when religious coping was kept constant, corresponds to the findings of previous research, which found “counter to expectation, older adults as a group may be more resilient to the anxiety, depression, and stress-related mental health disorders characteristic of younger populations during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic” (Vahia et al. 2020, p. 2253). Having gained life experience by navigating through previous significant periods of distress in their lives, may also contribute to older priests’ more favorable outcome.

We further stipulated in Hypothesis 3 that the distress of COVID-19 will be negatively associated with the professional identity of priests in Canada. Results supported this hypothesis and found not only that the priestly identity of clergy participants across Canada was negatively impacted, but furthermore that it lessened the priests’ sense of feeling satisfied as a priest. Many priests draw much of their sense of identity, meaning, and purpose from their work—their pastoral ministry—regardless of the type of ministry they are assigned to. In the beginning of the pandemic, when the first general lockdown went into effect in most of the provinces, clinical conversations with priests reflected a strong sense of loss and confusion, with many expressing a strong sense of bereavement as they were unable to engage in what gives meaning to their lives of service—pastoral ministry, communal prayer, celebrating public Mass, and assisting parishioners in need with Sacramental celebrations of baptisms, weddings, or funerals. For many, the challenges faced in ministering to the sick in hospitals or long-term care homes all were reported anecdotally as major stressors. The results of this study confirmed these reports, indicating how much the active engagement in ministry is a life-giving, meaning-offering aspect of priestly identity for Catholic priests. In addition to the COVID-19 distress, results also indicated that priests who engaged in spiritual activities during the pandemic score higher on satisfaction, while priests who had received counseling in the 12 months prior to the survey scored significantly lower. As previously discussed, the positive association between helpful spiritual activities and satisfaction is intuitive, but the result indicating a negative association between counseling received and priestly satisfaction requires further attention. However, this result likely captures a simple selection effect of priests with pre-pandemic low satisfaction opting for professional counseling. Furthermore, it is important to consider the small number of priests who indicated having received professional counseling within the last 12 months—less than 9% of priests reported receiving professional therapeutic support, and these priests, all other things being equal, scored lower on measures of priestly satisfaction than their colleagues.

In Hypothesis 4, we posited that the experience of loneliness will be negatively associated with the psychological well-being of priests in Canada. As discussed earlier, this hypothesis was supported by the findings. However, an interesting and unexpected point emerged from the data; namely, that while results indicated the negative association between loneliness and psychological well-being, living alone was classified by many priests as a positive association toward psychological well-being when loneliness was kept constant. At first sight, this seems counterintuitive and even contradictory; however, previous work by Okozi (2020) referenced a distinction between loneliness and aloneness. According to him, “one of the stark differences between loneliness and solitude is that loneliness is the experience of feeling isolated or disconnected from others or rejected by others, including by family members, colleagues, friends, or random acquaintances” (Okozi 2020, p. 3). For him, some possible outcome of the impact of loneliness on a person’s psychological well-being includes anxiety, depression, frustration, anger, high blood pressure, hopelessness, and helplessness. In our results, living alone is significantly beneficial for well-being when the level of loneliness is kept constant. In other words, if we compare priests who are equally lonely (and otherwise comparable), those who live alone will score higher on well-being.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

A substantial limitation with the current study concerns the timeline of data collection, in relation to the overall trajectory of the pandemic. Priest participants completed the survey at a time when the unknown factors of COVID-19 were changing rapidly, being adapted based on the current data of cases in each province. Consequently, there was no attempt to investigate emotional differentiation in priests’ range of well-being between the beginning of the study and the write-up of the findings and how the evolution of the new activities they engaged in altered positively or negatively the impact of COVID-19 crisis on each of them. Closely related, but a further limitation of research like this being conducted a pandemic lies in the lacking ability to control for precipitating causes of distress. There was no comparable study of the well-being of Catholic priests across Canada prior to the pandemic. This might be a significant shortcoming of research with this population, as Catholic priests across Canada have been exposed to major societal crises, with strong implications for the Catholic Church, such as the Residential Schools crisis, or the continued fallout from the clergy sexual abuse crisis. Future research would benefit from studies that would measure the psychological well-being of priests before and after a crisis.

This study shed light on the psychological well-being of a largely understudied population. While valuable insight was gained into a cross-section of Catholic priests across Canada, many of the demographic variables remained unexplored. For example, while it was noted that priests across Canada are a culturally diverse population, the study did not investigate how a priest’s cultural background may be related to his resilience. Future research could investigate whether priests from collectivistic cultural backgrounds, whose cultural values emphasize the positive aspects of a supportive community, experienced—for example—loneliness, anxiety, and depressive symptoms to a greater degree due to the COVID-19 restrictions than priests from individualistic cultural backgrounds. Furthermore, how cultural background, time of acculturation process, ordination cohort, style of seminary formation, and location of seminary formation—either within or outside Canada—relate to a priest’s religious coping strategies, or his sense of isolation/loneliness, remained largely unexplored. Future research could explore how priests cope with loneliness and what strategies they employ to navigate successfully through a sense of aloneness, versus developing loneliness. Since Roman Catholic priests live with compulsory celibacy/chastity, studies could compare how loneliness, religious coping, and psychological well-being present in a cohort of priests who are married, such as Anglican priests across Canada. Future studies could explore correlations between the wanted or unwanted loneliness of Canadian priests living alone in rectories and the vulnerability to the impact of crisis distress and/or boundary violations. In addition, future studies could investigate whether a more negativistic, scrupulous, or perfectionist outlook on one’s relationship with the Divine, or a more punitive and judging image of God—as seen in negative religious coping—may add to an individual’s vulnerability in regard to boundaries.

Another limitation of the current study is the fact that the findings regarding priestly identity and life satisfaction as a priest were based on 1-item measures included in the survey. Future longitudinal research could investigate empirically what a priest’s identity looks like throughout the span of his priesthood and as they age, have fewer responsibilities and engage in fewer ministry activities. A longitudinal study may allow the possibility to more accurately trace the type of social conditions, factors, and activities that positively or negatively alter priests’ identity during a crisis. It would also allow for use of a fully validated measure.

5.2. Summary

The current study set out to investigate the impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the psychological well-being of 411 Catholic priests across Canada. In accord with other research into the impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Canadian population in general, and Canadian frontline workers in particular, this study demonstrates that pandemic distress significantly impacts the psychological well-being of priest participants. The work of the current study indicates that priests who engaged in positive religious practices during the pandemic experienced less distress and higher psychological well-being than those who engaged in negative religious coping. Some priests experienced a closer relationship to God and a higher satisfaction as a priest, especially when they engaged in helpful friendship and spiritual activities; a finding that was in accord with clinical observations of the research team during virtual meetings and workshops around the country during the pandemic. In this study, while depression and loneliness were significant factors in lower psychological well-being in Catholic priests across Canada, the results exhibit that religious coping also had a strong impact as a source of distress, which greatly affected the psychological well-being of priests. Priests who endorsed negative religious coping reported signs of loss of meaning in relation to their identity and ministry, combined with an absence of hope, and questioned God’s action in their lives.

These findings raise questions regarding the psychological well-being of Catholic priests in Canada. Are the findings related strictly to the present distress of the long-lasting COVID-19 Pandemic and the obstacles that surfaced for priests’ ability to minister in their role as frontline workers, or do they reflect more fundamental challenges to priests’ psychological well-being linked to societal factors, such as the distress related to the declining sense of esteem for them as a group in an increasingly secular society? Do the findings reflect distress related to the declining number of priests paired with increasing demands on priests? Do the findings reflect distress related to the Residential Schools crisis, or the sexual abuse crisis, and a resulting shame or other difficult emotions priests may be experiencing as leaders in the institution that carries responsibility for these crises?

The study also raises important questions for bishops and other leadership representatives regarding the importance of loneliness as a factor that negatively impacts psychological well-being. Since a distinction emerged in the results among loneliness versus aloneness, it will be essential to explore further how priests can be supported in adaptively navigating their way through aloneness, without experiencing loneliness. The capacity for aloneness, which is included in the concept of affective maturity, might become a more closely monitored criterion for candidate assessments. In addition, continued work is necessary to help lower stigma associated with seeking professional help, including psychotherapy or even regular spiritual direction.

The priest participants in this study seem to treasure their role as pastoral frontline workers, holding an intrinsic value of ministering to those entrusted to them, suffering when they are unable to meaningfully connect with their parishioners, especially in times of crisis. The findings of this study may help illuminate factors that enhance the psychological well-being of Catholic priests not only across Canada, but globally.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K., I.O. and F.D.; Methodology, S.K., I.O., F.D. and K.H.; Software, K.H.; Formal analysis, K.H.; Writing—original draft preparation, S.K., I.O., F.D. and K.H.; Writing—review and editing, S.K., I.O., F.D. and K.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee of The Southdown Institute (29 March 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

Data collection was supported by Christine Dodgson, Research Assistant, The Southdown Institute, and editing was supported by Michelle Colangelo, Quality Control Editor, The Southdown Institute. We also wish to express our gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments that helped us immensely in improving our paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | A diocesan priest commits himself to a certain geographical area, called a ‘diocese’, and makes promises of celibacy and obedience to his local bishop. A diocesan priest usually lives alone or with other diocesan priests in a Church-provided rectory. A religious-order priest makes vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience to a superior, who is the elected leader of that religious order. The religious-order priest serves in fulfillment of the charisms and the mission of his order. A religious-order priest usually lives in community with other religious-order priests. |

| 2 | Respondents from provinces with fewer than five total respondents as well as respondents who were located outside of Canada at the time of survey (e.g., for vacation purposes) were combined into a ninth province labelled ‘other’ for privacy reasons. |

| 3 | As all respondents were asked whether they found a solitary or group living situation helpful during the pandemic, those who exclusively answered one of these two items were credibly assigned the respective living situation. |

| 4 | For all psychological scales, an observation was coded as missing if the respondent did not complete at least 80% of items of the respective (sub-)scale. For those respondents with missing items accounting for less than 20% of the (sub-)scale, the missing values as the mean of all completed (sub-)scale items were imputed. |

| 5 | In addition to these results, the relationship between the type of ministry (pastor versus chaplain, for example) and psychological well-being was analyzed. No statistically or psychologically significant connections were detected. |

References

- American Psychological Association. 2021. Stress in America™ 2021: Stress and Decision-Making during the Pandemic. Available online: https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2021/10/stress-pandemic-decision-making (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Best, Lisa A., Moira A. Law, Sean Roach, and Jonathan M. P. Wilbiks. 2021. The psychological impact of COVID-19 in Canada: Effects of social isolation during the initial response. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne 62: 143–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Civil Liberties Association. 2021. Emergency Measures by Province. Available online: https://ccla.org/fundamental-freedoms/mobility/emergency-orders-declared-across-the-country/ (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA). 2020. Ministry in the Midst of Pandemic: A Survey of Bishops. Washington, DC: Georgetown University. [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators. 2021. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet 398: 1700–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crea, Giuseppe, Lorenzo Filosa, and Guido Alessandri. 2021. Emotional distress in Catholic priests and religious sisters during COVID-19: The mediational role of trait positivity. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 24: 728–44. [Google Scholar]

- Cucinotta, Domenico, and Maurizio Vanelli. 2020. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Bio Medica: Atenei Parmensis 91: 157–60. [Google Scholar]

- Detsky, Allan S., and Isaac I. Bogoch. 2021. COVID-19 in Canada: Experience and Response to Waves 2 and 3. JAMA 326: 1145–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dozois, David J. A., and Mental Health Research Canada. 2021. Anxiety and depression in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national survey. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne 62: 136–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favaro, Avis, Elizabeth St. Philip, and Meredith MacLeod. 2020. Is an “Echo Pandemic” of Mental Illness Coming after COVID-19? CTV News. Available online: https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/coronavirus/is-an-echo-pandemic-of-mental-illness-coming-after-covid-19-1.4878433 (accessed on 6 October 2021).

- Holmes, Emily A., Rory C. O’Connor, V. Hugh Perry, Irene Tracey, Simon Wessely, Louise Arseneault, Clive G. Ballard, Helen Christensen, Roxane Cohen Silver, I. Everall, and et al. 2020. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. The Lancet Psychiatry 7: 547–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, Mary Elizabeth, Linda J. Waite, Louise C. Hawkley, and John T. Cacioppo. 2004. A Short Scale for Measuring Loneliness in Large Surveys. Research on Aging 26: 655–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kappler, Stephan, Eran A. Talitman, Carol Cavaliere, Greta DeLonghi, Michael Sy, Marc Simpson, and Susan Roncadin. 2020. Underdeveloped affective maturity and unintegrated psychosexual identity as contributors to clergy abuse and boundary violations: Clinical observations from residential treatment of Roman Catholic clergy at the Southdown Institute. Spirituality in Clinical Practice 7: 302–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, Kurt, Robert L. Spitzer, and Janet B. Williams. 2001. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine 16: 606–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutana, Samlau, and Parky H. Lau. 2021. The impact of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic on sleep health. Canadian Psychology 62: 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipka, Michael. 2019. Five Facts about Religion in Canada. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/07/01/5-facts-about-religion-in-canada (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Manea, Laura, Simon Gilbody, and Dean McMillan. 2012. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): A meta-analysis. Canadian Medical Association Journal 184: E191–E96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maunder, Robert G., N. Heeney, Gillian Strudwick, Hwayeon Danielle Shin, Braden O’Neill, Nancy Young, Lianne Jeffs, Kali Barrett, Nicolas S. Bodmer, Karen Born, and et al. 2021. Burnout in Hospital-Based Healthcare Workers during COVID-19. Health Equity & Social Determinants of Health. Available online: https://covid19-sciencetable.ca/sciencebrief/burnout-in-hospital-based-healthcare-workers-during-covid-19/ (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Mayo Clinic Staff. 2021. COVID-19 and Your Mental Health. Available online: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/in-depth/mental-health-covid-19/art-20482731 (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Okozi, Innocent F. 2020. Lessons from the psychological impact of loneliness and solitude. Covenant. July. Available online: https://southdown.on.ca/new_covenant/lessons-from-the-psychological-impact-of-loneliness-and-solitude/ (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Panchal, Nirmita, Rabah Kamal, Rachel Garfield, and P. Chidambaram. 2021. The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use. Available online: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Pargament, Kenneth I. 2001. The Psychology of Religion and Coping: Theory, Research, Practice. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament, Kenneth I., Margaret Feuille, and Donna C. Burdzy. 2011. The Brief RCOPE: Current psychometric status of a short measure of religious coping. Religions 2: 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prout, Tracy A., Sigal Zilcha-Mano, Katie Aafjes-van Doorn, Vera Békés, Isabelle Christman-Cohen, Kathryn Whistler, Thomas Kui, and Mariagrazia Di Giuseppe. 2020. Identifying Predictors of Psychological Distress During COVID-19: A Machine Learning Approach. Frontiers in Psychology 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. 2021. Canada COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiology Report 16 May to 22 May 2021 (Week 20). Available online: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/ (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Ryff, Carol D., and Corey Lee M. Keyes. 1995. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69: 719–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamblaw, Amanda L., Rachel L. Rumas, and Michael W. Best. 2021. Coping during the COVID-19 pandemic: Relations with mental health and quality of life. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne 62: 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, Jeffrey. 2021. Characteristics of Frontline Essential Workers in New York State, New York State. Available online: https://dol.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2021/09/characteristics-of-frontline-workers-09-22-21.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Spitzer, Robert L., Kurt Kroenke, Janet B W Williams, and Bernd Löwe. 2006. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine 166: 1092–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Statistics Canada. 2021. The Impact of COVID-19 on Health Care Workers: Infection Prevention and Control. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/daily-quotidien/210202/dq210202a-eng.pdf?st=p_SEeDMm (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Stepner, Michael. 2017. MAPTILE: Stata Module to Map a Variable. Statistical Software Components. Available online: https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:boc:bocode:s457986 (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Vahia, Ipsit V., Dilip V. Jeste, and Charles F. Reynolds III. 2020. Older Adults and the Mental Health Effects of COVID-19. JAMA 324: 2253–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, Daniel S. 2007. The Impact of Event Scale: Revised. In Cross-Cultural Assessment of Psychological Trauma and PTSD. International and Cultural Psychology Series. Edited by John. P. Wilson and Catherine S. Tang. Boston: Springer, pp. 219–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilt, Joshua A., Nick Stauner, Valenica A. Harriott, Julie J. Exline, and Kenneth I. Pargament. 2019. Partnering with God: Religious coping and perceptions of divine intervention predict spiritual transformation in response to religious−spiritual struggle. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 11: 278–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 2020. COVID-19 Disrupting Mental Health Services in Most Countries, WHO Survey. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-10-2020-covid-19-disrupting-mental-health-services-in-most-countries-who-survey (accessed on 3 August 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).