Abstract

This article seeks to contribute to the study of migration and religion in two EU countries, Croatia and Italy, by examining the impact of religiosity and cultural identification on negative attitudes toward immigrants. In many European societies, the increasing diversification within different levels of society stemming from recent migrations has turned immigrants’ reception and integration into a key issue, whereby migrants are often perceived as a threat to the dominant religion and culture, thus aggravating the process of migrant integration within society. Our article follows recent empirical research on migration and religion, which determined that higher levels of religiosity are positively correlated with negative out-group attitudes. Conducting quantitative research in Croatia (N = 603) and Italy (N = 714) and based on the analysis of primary data, firstly, we assess whether there is an association between negative attitudes towards immigrants depending on different degrees of religiosity and levels of cultural identification. Secondly, we examine the differences of the socio-religious contexts of Croatia and Italy, with a focus on the interplay between religion, national identity, and migration patterns. In line with this, our research shows that religiosity has the largest influence on negative attitudes toward immigrants, implying that higher levels of religiosity result in higher levels of negative attitudes toward immigrants. Furthermore, the results of our research show that Croatian participants have more negative attitudes toward immigrants than Italian participants, whereby Roman Catholic participants in both countries are more negative than non-religiously declared participants.

1. Introduction

Croatia and Italy, even though they are both predominantly Catholic, are marked by different paths of establishing democratic values, different levels of religious diversity, and different experiences of migration. While in Croatia, the legacies of the fallen communist regime produced divisions among different religious groups, Italy has a longer history of interreligious cooperation. While in Croatia, religious and national diversification stayed tied to the socio-demographic structure of the former regime, and migration flows are only recent and still in lower numbers; in Italy, it is mostly the outcome of the last decades’ new immigration waves and constant increase in migrant population. The main aim of this research is to analyze the influence of religious and cultural identification on the negative attitudes toward immigrants. This study has a quantitative approach and analyses the results of a survey that applied a revised version of the Social Perception of Religious Freedom (SPRF) questionnaire (Breskaya and Giordan 2019), which we have submitted to a convenience sample of Croatian and Italian University students in 2021. For the purposes of our research, the SPRF questionnaire was further developed by adding sections on cultural identification, belonging, and citizenship.

Within this, we firstly focus on the linkage between culture and religion, in order to examine whether there is an association between negative attitudes towards immigrants depending on different degrees of religiosity and cultural identification. Secondly, we examine the effect of socio-religious context, with a focus on the interplay between religion, national identity, and migration patterns between Croatian and Italian participants. Following this, we give a short introduction to the interrelatedness of migratory issues and the role of religion, which only is a scratch on the surface, while in the following two subparagraphs, we analyze the specifics and the issues concerning migration dynamics and religion in two predominantly Catholic countries—Croatia and Italy. For the purposes of our study, we focus more specifically on the differences between these two countries, revealing two different backgrounds and experiences of migration dynamics and diversity, along with two different embodiments of religious identity.

Considering immigrant issues in relation to religiosity, a range of studies have shown that higher levels of religiosity are linked with negative attitudes toward immigrants (Bohman and Hjerm 2014; Kumpes 2018; Čačić Kumpes et al. 2012; Scheepers et al. 2002). Indeed, this kind of relationship depends on the various contextual factors within sociopolitical dimensions and is influenced by various characteristics of country’s religious landscape (Bohman and Hjerm 2014). Bohman and Hjerm (2014) examined the influence of different religious contexts on negative out-group attitudes and found that strongly religious people, on average, oppose immigration more than non-religious people. Additionally, countries with prevailing Catholicism tend to be more averse to immigration, while Hall, Matz, and Wood emphasize that where the attachment to certain religious identity is stronger, the stronger the resistance is toward other groups (Hall, Matz, and Wood in Bohman and Hjerm 2014). Along with this, leaning on group threat theory and devolving into the problem of contextual differences, Bohman and Hjerm (2014) emphasize that specific contextual factors can become one of the main triggers for negative out-group attitudes. For example, social cohesion based on ethnicity or religion, religious homogeneity, policies of state–religious relations in terms of favoring or restrictions, or type of the religion prevailing in a country, can be strong mediators of how attitudes will be articulated toward other groups. Kumpes (2018), exploring religiosity and attitudes toward immigrants in Croatia, came to a conclusion similar to both previous research and the findings in our research. In short, according to Kumpes (2018), those identifying as highly religious express more negative attitudes toward immigrants, and mainly perceive them as a cultural threat, while exploring the linkage between national identity and religiosity, Kumpes (2018) emphasizes that these two concepts are highly interconnected, thus concluding that negative attitudes toward immigrants are more expressed with participants that identify themselves as Roman Catholic and believe that nationality and religiosity are strongly connected; while those identifying themselves as non-religious, tend to have significantly lower levels of negative perception toward immigrants as a socio-cultural threat.

Following these theoretical observations, we provide the results of our analysis, testing two hypotheses. Firstly, we hypothesize that negative attitudes towards migrants are positively correlated with higher levels of religiosity and stronger cultural identification. Hereby, we lean on the empirical research mentioned before, testing the linkage between high religiosity, national identity, and negative attitudes toward immigrants (Bohman and Hjerm 2014; Kumpes 2018). Secondly, we hypothesize that there is a difference between Croatian and Italian participants in their views of immigrants, as well as focusing on the difference between those declared as Roman Catholic and non-religious in Croatia and those declared as Roman Catholic and non-religious in Italy. More specifically, we hypothesize that negative attitudes toward immigrants are stronger in Croatia than in Italy and are more negative among participants affiliated with the Roman Catholic Church in Croatia than those affiliated with the Roman Catholic Church in Italy. Within the framework of our second hypothesis, we lean on the contextual differences between these two countries, whereby countries with a communist historical background, such as Croatia, tend to be less receptive and hospitable to diversity, than countries with a longer tradition of democracy, such as Italy (Scheepers et al. 2002; Kumpes 2018). In this sense, regardless of both being pre-dominantly Catholic, Croatia and Italy have a different background of religious and national diversity, different historical encounters with migratory groups, and have built their national and religious identities differently, which evolved as a consequence of different historical events of establishment and development of democratic values and norms, eventually producing two different relationships between religious and national identity (see Figure 1).

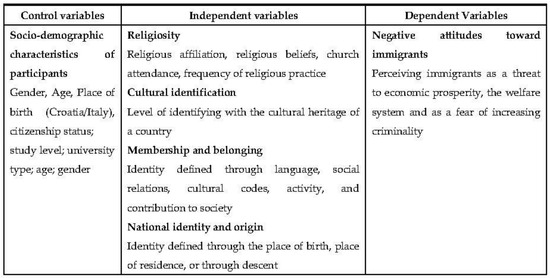

Figure 1.

Conceptual model for the study of attitudes toward immigrants and religiosity.

2. The Dynamics of Migration Issues Burdened by Religion

The dynamics of migration in Europe has become a major issue in the past few decades. The main reason why migration is mostly perceived as a problem refers to the capability of social reception of migrants within societies, whereby migrants and refugees are mostly perceived negatively due to the cultural and identity differences they bring along. As Žagi (2021) claims, migrants in relation to the dominant society are always “othered” by the majority, while the level of this “otherness” depends on the specificities of migrants groups in terms of language and racial differences, religious affiliation, and cultural and social divergences from the dominant society. Considering group identities and interaction produced between them, Modood and Thompson (2021) examine what is encompassed by the process of “othering”. This usual process of constructing and deconstructing social identities through the interaction of two or various groups regardless of its habitually, can sometimes evoke the “otherness” of the groups subordinate to the dominant one (Modood and Thompson 2021). As Modood (2019) claims, “otherness” represents a perception of minority groups by the dominant group, as being something ‘inferior and threatening’ (Modood 2019, p. 78), producing negative connotations and exclusion of the specific “other”, as a result of fear and necessity to keep the leading position within society (Modood 2019; Modood and Thompson 2021). Since religious groups within societies are mostly competing with each other for the same goods, whether it is between dominant and minority groups or on the majority–minority group level, this is precisely why religious people perceive others, who are allegedly trying to take what is theirs, as a potential threat and danger to the sustainability of their own religious identity (Bohman and Hjerm 2014). Thus, these negative attitudes toward the specific “other” may vary, depending on the dominant religion of the country, the levels of religious homogenization and how the state–religious relations are regulated (Bohman and Hjerm 2014), along with influencing factors such as the geo-political position of the country, its demographical structure and historical background of religious and national relations.

As Bohman and Hjerm explain, religion has always been a great factor in the ‘creation and sustainment of social cohesion’ (Durkheim in: Bohman and Hjerm 2014), especially in countries with a Catholic dominance, causing the religious context to partly be a factor that affects attitudes toward foreigners. In this sense, the cultural values and religious homogeneity of certain society becomes challenged by foreigners, which finally produces a fear among the dominant society that important aspects of their identity, values, and belief system could be potentially damaged (Bohman and Hjerm 2014). While religiosity can present an obstacle to the integration of migrants in different ways, on the other hand, religious institutions can offer a sense of belonging and acceptance, providing help and connections that can serve for an easier process of assimilation within the new community, at the same time offering a place where migrants can stay linked to their own cultural values and traditions, while accepting the transformation of their own identities (Foner and Alba 2008). As Zanfrini (2020) claims, religious affiliation becomes an element of vulnerability, whereby religion is used as a factor for filtering in terms of inclusion or exclusion, thus only giving the chance to those foreigners that can more easily cross cultural and social frontiers of a specific society.

In this sense, religion has two contradictory faces, on one hand, it can represent a strong voice in defending and advocating for the rights of those in need; on the other hand, it can be a burden in the process of the assimilation of the migrant population (Zaccaria et al. 2018; Zanfrini 2020). The sole process of assimilation also depends on the socio-political and religious context of a specific country, thus defining the desirable aspects of migrant assimilation within a specific country, influencing whether the process of integration is facilitated more easily for those with the same religious background as it is for the majority part of the society, regardless of them being foreigners. With this in mind, the State’s position and its governing mechanisms represent a weight that directs the balance within this tension, guiding the way to approach immigrant issues and migrant reception within societies. Most EU country migration policies are guided by the practice of integrating migrants into society, implying a two-way process of integration and adjustment—assimilation and pluralism, whereby both practices have a goal of establishing the balance between the recipient society and migrant population for both sides (Knezović and Grošinić 2017). The practice of assimilation is related to the process of foreigners’ adaptation to the values and norms of the recipient society based on a peaceful coexistence within a diversified society (Knezović and Grošinić 2017). The pluralist practice of migration policies fundamentally revolves around the acceptance of cultural differences, their freedom and equality within society, supporting openness, dialogue, and tolerance toward cultural diversification (Knezović and Grošinić 2017).

Research on the dynamics of migrations and the effect of religion has long been one of the main interests in the field of sociology, especially in the 20th and 21st centuries during the increase in migratory trends (Foner and Alba 2008; Kvisto in Kumpes 2018). There are three main aspects of researching the role of religion in the sphere of migrations—the differentiation of immigrants based on their origin and country of origin; the characteristics of religiosity of the dominant society; and the establishment of an institutional legal framework that usually reflects certain historical relations between majority and minority groups (Foner and Alba 2008; Kvisto in Kumpes 2018). Additionally, Kumpes (2018) highlights the importance of contextual differences when studying migration topics, while Bohman and Hjerm (2014) emphasize the significant lack of comparative studies in terms of empirical research on the interrelation of migration and religion. Most research studies imply that immigrants are mainly perceived as a cultural threat (Mc Laren 2003; Sides and Citrin 2007, 2008; in Kumpes 2018), while according to the study by Pew Research Centre, European refugees are seen as a danger factor for possible terrorism, a threat to certain social and economic privileges, and a cause of increased criminal (Kumpes 2018). Additionally, Scheepers et al. (2002), determined that certain religious aspects such as belonging to Christian denominations, church attendance, and levels of religious differentiation are connected to ethnic prejudice (at least in the case of European countries), while low levels of socio-economic inclusion is to a great extent connected to higher levels of religious practice (Zanfrini 2020). Indeed, for most researchers, religion represents a main obstacle in the process of integration of migrants, especially in the case of migrants affiliated with Islam (Foner and Alba 2008; Kumpes 2018).

The entanglement of Europe in the issues of migratory crises is becoming more and more evident each day and, above all, necessary. Starting with the huge migrant crisis in 2015 and with the recent violent conflict in Ukraine, which has already disturbed social and economic spheres on the global level, these crises are unquestionably testing Europe’s preparedness (legal and on the ground) for the changes that are already happening. Regardless of the support of various organizations and institutions, it seems that below the surface, Europe is practicing the “not in my yard” rhetoric. As Zanfrini (2020) claims, the view of the European public on migrants usually comes down to something that Europe needs to defend itself from, while these alarms that are invoking defense systems usually do not regard only economic issues and the labor market, but above all the fear of cultural fading. Considering all of these points, the arrival of migrants with various national, religious, and cultural backgrounds can indeed verify the true embodiment of democracy, democratic values, and the spectrum of religious freedoms in a specific society (Zanfrini 2020).

2.1. Croatia

When it comes to Croatia, the problematic background of migration issues are connected to regional disturbances and internal displacements caused by the fall of Yugoslavia and the war in 1990s, which ultimately produced changes within social, political and cultural domains of Croatian society. According to Kumpes (2018), there are three main aspects that highly influenced the dynamics of migration in Croatia. The first aspect is the long-term historical presence of various ethnic, confessional, and cultural identities of the Balkans, which shape today’s relations among different entities. Even before the collapse of the Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY), most of the foreigners that Croatia received were coming from other Balkan territories, which were largely similar to Croatia in terms of language or cultural and social customs (Kumpes 2018). The second aspect of migration dynamics in Croatia is connected to the events of the war in the 1990s, the process of transitioning to democracy, and the national homogenization of Croatian society. Finally, the third aspect is the process of the preparation and entrance into the EU, a factor which transformed the sole dynamics of migration, whereby Croatia became more open to new foreigners, but more importantly, led to an easier process for emigrating Croatian citizens (Kumpes 2018). ‘Socialist era constitutions had placed all citizens on formally equal footing, guaranteeing the rights and proportional representation of national minorities’ (Verdery 1998, p. 4), as was the case with the former Federative Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY), whose end signified the beginning of a hard period of transition to democracy marked by the beginning of the total collapse of constitutional rights and protections of minority groups, turning today’s citizens into tomorrow’s foreigners (Bogdanić 2004; Štiks 2015; Koska and Matan 2017). Changes within legal aspects of citizenship status and rights were particularly problematic for those living in zones of conflict, those of a different ethnicity, or for families with mixed nationalities (Štiks 2015).

The Croatian War of Independence resulted in massive regional displacements, which were estimated to be between 250,000 and 500,000, while larger military actions in 1995 mostly targeted the Serbian population, resulting in a mass exodus of more than 200,000 Serbs (Stubbs and Zrinščak 2015). According to Štiks (2010), the legal framework of the constitutional laws and formulation of rights reserved for citizens of Croatia was used as an effective tool for nation building in the 1990s and a tool for controlling and influencing the ethnic composition of the population residing in the territories of Croatia.

The sole process of EU accession and the requirements of the international community played a significant role in defining the legislative framework and institutional set-ups that would protect and guarantee the rights of foreigners (Knezović and Grošinić 2017). In the light of Croatia’s aspirations to enter the EU and under the pressure of external factors of international communities, Croatia was demanded to start working on lowering the ethnic component within the legal framework of its constitution and to abound the explicit ideas of national constitutionalism (Dimitrijević 2012). This mostly concerned the Serbian ethnic minority, as it was one of the most affected minorities during The Croatian War of Independence. In this sense, regardless of the minimized existence of the Serbian minority within Croatian society, the State still needed to find an adequate way to set the relations and legal framework to minimize the ethnic intolerance within the frame of majority–minority relations (Štiks 2010, 2015; Dimitrijević 2012). Even though the accession to the EU certainly had a positive effect on the legal framework of citizenship policies and regulations of migrant issues, it is questionable whether Croatia engaged in profound reforms of its issues and lowered the ethnocentric character of the State, or whether these changes only satisfied the more general and easier-to-handle issues, without carrying out a real change on the ground (Štiks 2015).

Taking all these points into account, it seems that a situation of conflict disturbances combined with undermined standards of living and confrontation with economic difficulties, which emerged as a consequence of a post-conflict environment, largely put Croatia on the map as a country with the highest levels of emigration rates (Knezović and Grošinić 2017). Even though the exact data on immigration/emigration levels of Croatia have not been revealed, the numbers reflect the notion of Croatia as not being a chosen destination for foreigners, but mostly serving as a transitional country. This was also the case in the big migrant crisis in 2015, when neighboring countries started closing their borders, thus making Croatia a passing-through point, whereby migrants often did not even know where they were passing through, let alone perceived Croatia as their final destination (Giordan and Zrinščak 2018). Except for the crisis in 2015, Croatia mostly experienced emigrational trends, whereby the accession to the EU opened the borders for Croatian citizens, facilitating the flow of emigration, thus creating a trend of negative migration saldo (Knezović and Grošinić 2017). According to the Croatian Bureau of Statistics, the data from 2020 indicate that 34,046 people moved abroad from Croatia, which is less in comparison to 2019 numbers, even though COVID-19 limitations probably had quite an effect on the numbers in the past two years. More than half of the citizens who emigrated from Croatia (54.8%) chose Germany as their destination country, assuredly for economic and employment reasons, and in search of better living standards. The data on immigration levels from 2020 indicate that 37,726 people immigrated to Croatia, which is around 27,000 more than in 2014 (Knezović and Grošinić 2017)1. As Knezović and Grošinić (2017) imply, Croatia was always seen as more of an emigrating state rather than a chosen destination for foreigners, so Croatia never fully experienced its ability and capacity to receive foreign population. However, recent events in Ukraine could significantly change the patterns of migration dynamics in Croatia. On the other hand, even though the EU conditioned a range of changes concerning the policies and management of migration in Croatia, there are still many gaps to fill within the system, which were especially visible in the immigrant crisis in 2015 when more than 600 thousand people crossed through Croatia, and the State did not have an adequate response in terms of policies or how to manage the crisis on a national level (Knezović and Grošinić 2017). The whole legislative framework concerning refugees and immigrants reflects Croatia emigrating policy and the fact that Croatia’s migration dynamics were mostly connected to regional movements within the Balkans. This is also reflected in the statistical numbers concerning migratory dynamics (Knezović and Grošinić 2017).

One of the main identity markers in former Yugoslavia was religious affiliation, thus making the region of the Balkans a mixture of Catholicism, Islam, and Christian Orthodoxy, whereby each country had one of these religions as a dominant one. As Kumpes (2018) claims, the multi-ethnicity, multiculturality, and multi-religiosity forms a crucial part of Croatian society, thus making the long history of coexistence, lingual and cultural similarity a fundamental part of relations between dominant majority and minority groups in Croatia. The events of the war in the 1990s had a great impact on how religious identities will be seen in the future time, and how religious minorities will position themselves within the religious sphere of dominant Catholicism. These socio-political changes, empowered by war events and intolerance, created a social and psychological need for belonging and a need to claim a certain identity as its own, whether it regards the religious or national one (Maldini 2006). In this sense, national identity became intertwined with the religious one, thus being Croatian meant being Catholic.

These equalizations of religious and national identity position religion as one of the main tools for creating and building a new identity, empowered by Catholicism. With the ‘rise of religion’ (Zrinščak 2006), old traditional values and customs became the new main remarks of the new Croatian identity (Radović 2013; Zrinščak 2006; Jerolimov and Zrinščak 2006). As Marianski (2006) claims, the revival of religion was manifesting in a way that people were attempting to save their national identity, in contrast to the times when their identity was jeopardized by the enemy, which caused disturbances within the sphere of belonging, initiating the ‘rebirth of religion’ (Marianski 2006). During the events of transition and socio-political disturbances, the Catholic Church saw as its own opportunity to become the religion of the people and the official religion of the State, thus playing an extremely important role in supporting Croatia’s aspirations for full independence, democracy, and transformations that caused the process of “Croatisation” (Jerolimov and Zrinščak 2006; Marinović-Bobinac and Jerolimov 2006). Even though, declaratively, religion was defined as an institution separated from the State, the Catholic Church saw the fall of SFRY as a prosperous moment to achieve not only national but also religious liberation. This gave the Church the ability to define collective identity (Maldini 2006; Zrinščak 1998) and serve as a guardian of Croatian cultural identity, hence positioning religious and national minorities in an undesirable place (Jerolimov and Zrinščak 2006). As Maldini (2006) notes, the sole confessional identification was not narrowed only to religiosity; moreover, it represented the sphere of national identity, culture, tradition, and nation building, while the increased religious practice illuminated the liberation from the former regime, welcoming the long-awaited social acceptance of religion (Maldini 2006), at least for the Catholic majority.

In the period of Croatia’s nation-building, from 1991 until 2000; the Orthodox Serbian Church suffered a significant decrease in the number of people facilitated with it, which basically corresponds to a general decrease in Serbian population in Croatia, while the empirical data from the early 1990s imply a significant increase in Catholicism and the revitalization of religion. For example, in 1991, 11.1% of people were declared as Christian Orthodox; while in 1996, only 2% of Croatia’s population belonged to the Christian Orthodox community (Zrinščak 1998; Kompes 2018; Župarić-Iljić 2013). According to the latest census data from 2011, most of Croatia’s population affiliated as Roman Catholic (86.3%), 4.4% belonged to Christian Orthodox community, 1.6% were Muslim, while 4.6% affiliated as non-religious. A strong vision for the chosen religion of the State, enforced by nationalism, brought about new social circumstances, whereby religious rights and freedoms were conditioned by political disputes and an atmosphere of intolerance toward the significant other (Zrinščak 1998).

This tension between the majority and minorities, whether it was religious or national, and the necessity to protect the main symbols of nationhood, produced notions of a dominant society feeling jeopardized and threatened by foreigners and the cultural customs they brought along (Marinović-Bobinac 1996). This feeling of threat was reflected in a hostile and negative attitude toward foreigners, regardless of their cultural similarity with the dominant society (Marinović-Bobinac 1996). Strong nationalist ideas and the ethnic-centered character of the nation-building process in the 1990s, created as claimed by Knezović and Grošinić (2017), led to a strong sense of national and religious ‘we-ness’ (Knezović and Grošinić 2017, p. 23), which is reflected in the migratory policies of Croatia and an inability to accept cultural differences, thus producing a rejection towards the migrant population. For this reason, Maldini (2006) highlights the significance of intertwining religious and national identification, implying that confessional identification reflects the complexity of religious identities in Croatia, whereby confessional identification encompasses a broader meaning of identity, which is connected to a strong sense of social and cultural identification (Maldini 2006).

2.2. Italy

The migration flows that marked Italy’s socio-demographic structure in the last two decades most simply could be defined as a change that turned Italy, a country of emigration, into a country of mass immigration. Of course, it must be understood that these changes brought by new cultures, religions, and nationalities did not have an immediate effect, but slowly and gradually changed the structure of society until the diversification of the society became visible and tangible, resulting in the clash between the values of the dominant culture and the demands of new minority groups and their right to nurture and acknowledge their own values (Pace 2014; Giordan and Zrinščak 2018; Zaccaria et al. 2018). As Zincone (2010) claims, several factors of past and historic events have influenced how immigrant issues are handled today—such as the late and unfinished unification of state territories, the experience of mass emigration at the beginning of the twentieth century, a long period of “searching a state” and recovering from an authoritarian regime. The legal framework concerning migrant issues (especially the 1992 Citizenship Law), reflected the policy of Italy as a country of emigration and was based on the idea of protecting citizens who left the country (Zincone 2010; Zincone and Basili 2013). All of this shaped policies toward migrants’ issues, focalizing the legal framework handling migration issues (1992 Citizenship Law) around Italian’s living abroad and the principle of ius sanguinis, with the goal to nurture the linkage between Italy and its citizens living abroad (Zincone 2010; Zincone and Basili 2013).

Fostering the relationship with the emigrant population as a member of the political community, positioned the issue of immigrants on the margins of the legal framework and current dilemmas, thus resulting in a system with an enormous flaw once Italy started experiencing mass immigration flows (Zincone 2010). Once different cultures, languages, and religions stopped being only something surrounding the margins of society, but became something visibly evolved within social, political, and cultural life of Italy, the flaws of the established system started to become more evident and tangible (Zincone 2010). The unpreparedness of Italian society and unsuitable legal framework caused uncertainty and intimidation within different levels of society, reflected in the perception of migrants as a threat to dominant culture, values, and heritage, and resulting in an inability to adequately respond to demands for the diversification of society. Rising issues evolved around questions on how to protect the existing values deeply rooted within Italian society but have the capacity to embrace the changes brought by new foreigners.

According to ISTAT (Istituto Nazionale di Statistica), in 20112, Italy officially reached an immigrant population of over four and half million, which placed Italy among the countries with the highest rates of immigrant population. According to ISTAT (Istituto Nazionale di Statistica) report from 20193, the number of immigration flows decreased by 8.6%, while the number of people leaving Italy continuously increased. The trend of the decrease in the number of residents started in 2015, but on the other hand, the population of foreign citizens residing in Italy increased, although with a relatively small number in comparison to the period before, thus occupying 8.8% of the total residing population. Additionally, when it comes to the number of foreigners who managed to obtain citizenship status, the number went from a position of decreasing in 2017 and 2018, to a substantial increase of 13% in 2019 in comparison to 2018. In terms of overall numbers, for the period from 2015 until 2019, about 766,000 foreigners became Italian citizens. Furthermore, the analyzed data from ISTAT show that Italy is a multi-ethnic country, counting more than two hundred different nationalities. The balance within the socio-demographic structures of national minorities groups remained stable in the sense that Romanians are still the largest minority, accounting for over one million of population. In second place are Albanians, followed by people emigrating from Morocco. China are in fourth place, and Ukrainians are in fifth place, which with the recent events in Ukraine, could change the overall picture of the immigrant population in Italy. The annual immigration inflow of non-EU citizens in 2020 was estimated to 106,503, and the number of foreigners that acquired Italian citizenship in the same year was 131,803, higher than in 2019. The process of acquiring citizenship for 66,211 people went through residency requirement, 14,044 people acquired it through marital status, and around 51 thousand through other requiring conditions4. Furthermore, according to ISTAT Annual report from the year 20215, the number of foreign people residing in Italy was estimated 5,171,894, while the emerging and continuing crisis of COVID-19 had a severe impact on the demographical balance of Italy, not only producing high rates of mortality but also impacting the number of immigration and emigration flows in the past two years. The restraint on the mobility and movement of people produced a decrease of 30.6% in immigration flow, while the number of people emigrating from Italy decreased by 10.8% in comparison to the 2015–2019 average.

The effect of migration changes has changed the socio-demographic structure of the country producing tensions within the religious sphere as well. A country monopolized by Catholicism is now challenged by increased religious diversification and confronted with the demands of new religious minority groups, which produces tension not only within majority–minority relations but also within state-religion relations (Pace 2014; Giordan and Zrinščak 2018; Zaccaria et al. 2018). Socio-religious image of Italy was changing gradually over the last twenty decades, but with the increased religious pluralism and mass immigration flows Catholic Church needed to find a way to assimilate to challenges brought by new religious diversification (Pace 2014). Following the path of assimilating to a changed socio-religious structure of the society, and acknowledging the existence of other religious groups, Catholic Church remained its strong and vivid presence in the public life of Italy, not only due to its strong historical and cultural roots but also due to its capacity to resist religious transformations and challenges brought by religious diversification (Pace 2014; Garelli 2012). In this sense, the Catholic Church started working on a strategy to maintain its strong position and started replacing the disinterest toward other religious communities with openness to interreligious dialogue and religious tolerance (Pace 2014). Following the path of social Catholicism, which was initially a response of the Catholic Church to capitalism and changes within society, thus incorporating the ideas of the Church within different public dimensions of society (Shadle 2018), the Catholic Church started performing various social roles within the public sphere, and one of these roles included the care of and active contribution to the migrant population. This presented one way to strategically maintain its main position within society, but at the same time showed its ability to embrace others by providing a support system to migrants through welfare organizations, highlighting social injustices, and openly criticizing discriminatory government practices (Pace 2014). As Zaccaria et al. (2018) claim, a strong religious authority can indeed serve in promoting the rights of refugees and immigrants. Following the path of interreligious dialogue and openness, the Catholic Church in Italy directed its power in advocating for those in need, thus becoming a voice advocating for the rights of refugees and immigrants, promoting the idea of tolerance, inclusivity, and interreligious cooperation, and opposing discriminatory and xenophobic political discourses (Zaccaria et al. 2018). In this sense, the Catholic Church served as a neutralizer between the needs of migrants and the needs of many faithful Italians, trying to alleviate the feeling of threat among dominant society (Giordan and Zrinščak 2018). Nevertheless, increased religious pluralism and socio-demographic changes within society have not unsettled the strongly embedded Catholic identity of Italians (Garelli 2012). As Pace (2014) sees it, the population of Italian society still holds on to the old-fashioned Italian Catholic identity but with less practical involvement than before. As Garelli (2012) claims, for the people of Italy, religion, or rather Catholicism, represents a reference point of their identity and indeed, Italians do love the ‘spectacle of faith’ (Garelli 2012), the experience of the accompanying content that comes with public religious celebrations. In this sense, the relationship of Italians and the Church could be explained as close and, at the same time, distant, signifying a certain paradox of this relationship—the strong power of the Catholic Church to occupy and focus on the public sphere, but emptiness when it comes to church attendance (Garelli 2012). Following these notions, together with the historical and cultural background of religion in Italy, it is not strange that the majority of Italian citizens still proudly identify as Catholic (Ferrari in: Giorda 2015), whereby being Catholic represents a central point of Italian collective identity as a part of cultural and national heritage (Giorda 2015). According to the latest data of ARDA from 2015, Italy’s religious landscape encompassed 78.28% of people identifying as Catholics, 16.55% of specified and unspecified religiously non-affiliated, 2.66% of Muslims, 1.05% of Protestants and 0.24% of Orthodox Christians6. Even though various religious communities were long present within Italian society, the consequences of immigration flows have affected and changed the religious landscape of the country, while the most visible change is noticeable in the increase in Islam and Orthodox Christian communities (Garelli 2012). Foreign immigrants, who form part of religious minority groups, use these organizations as a cultural bond with their nationality and heritage in order to distinguish themselves from the dominant majority and, at the same time, utilize these groups as a channel to achieve their collective and individual rights within the public sphere (Garelli 2012).

3. Research Procedure and Methodology

The instrument used in this study was tested in two countries, Croatia and Italy, and the questionnaires were submitted to university students during the period from March 2021 to February 2022. Due to COVID-19 limitations and our dependence on university classes and students, we collected questionnaires using three different methods, depending on which was best suitable for the given situation in each country at each specific period of the time. In Croatia, we collected 603 questionnaires through online software which allowed students to anonymously respond to the questionnaire. In the case of Italy, we collected 546 questionnaires by paper–pencil method and 168 questionnaires by conducting telephone interviews, reaching a total number of 714 submitted questionnaires to university students in Italy. Taking all of this into account, we collected 1317 questionnaires completed by university students in Croatia and Italy. The collected data were analyzed by SPSS using frequencies, Pearson correlation coefficient, exploratory factor analysis, regression analysis, and ANOVA. In our analysis of the data, each of the conducted scales was tested in terms of Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, as well as demonstrating means and standard deviation for each item. Following this, we computed the Pearson correlation coefficient to determine the level of correlation between our dependent variable, ‘Negative attitudes toward immigrants’, and all our independent variables. Furthermore, each of the computed scales was tested by exploratory factor analysis (EFA), computing the principal components method (PCA). Finally, in order to determine the effect of religiosity and cultural identification on ‘Negative attitudes toward immigrants’, we carried out a regression analysis, while ANOVA was performed in order to determine the differences in ‘Negative attitudes toward immigrants’ between Croatian and Italian samples.

3.1. Socio-Demographic Structure of Participants

In our sample, 24.6% of participants are males (N = 324), while 75.4% are females (N = 991), on average between 18 and 24 years old (85.4%). The majority of participants in our research holds Croatian or Italian citizenship (99.5% in Croatia and 94% in Italy), while 93.7% of participants are born in Croatia and 91.4% are born in Italy. In the case of Croatia, the majority of students were 1st year students studying for bachelor’s degrees (78.8%), including law, economics, as well as social and other sciences. In the case of Italy, the vast majority of students were 1st year students studying for bachelor’s degrees (77.3%), including international relations and political sciences, humanities and cinema, music, and art sciences. Regarding the religious affiliation of the participants, in Croatia, 77.4% of university students declared themselves as Roman Catholic; 19.4% as non-religious and 3.2% belonged to other religious groups, from which 1.3% were Islam. In Italy, from 714 respondents, 54.2% declared themselves as Roman Catholic, 39.1% as non-religious, while 6.8% belong to other religious minorities, from which 2.4% are Muslim and 1.7% Christian Orthodox.

The sampling in our study includes only university students from both Croatia and Italy, thus enabling us to conclude our findings on a general level. Though our sample is not considered a small size sample, its limitation is that it targets only a young age cohort and only university students, who come from different educational backgrounds, such as law, economy, social sciences, humanities, arts, etc., though with a lack of students studying natural sciences.

4. Results of the Analysis

The Cronbach’s alpha reliability test measures the reliability of the questionnaire, or rather the reliability of the scales used to measure a particular construct (Brownlow et al. 2014): ‘Negative attitudes toward immigrants’, ‘Cultural identification’, ‘Religiosity’, etc., in our case, and it is one of the most valuable methods for examining reliability. Cronbach’s alpha reliability test is a necessary part of any quantitative study since all of the analysis results would not be meaningful if the scales used in our questionnaire are unreliable (Brownlow et al. 2014). Following these criteria for testing reliability, our scale for measuring negative attitudes toward immigrants is composed of three items: ‘Immigrants take jobs away from Italians’; ‘Immigrants make problems with crimes worse’ and ‘Immigrants are a strain on a country’s welfare system’7, while the reliability of this scale is 0.86 according to Cronbach’s alpha, which implies that the scale has a very good level of reliability. Since this scale consists of only three items, we also refer to the inter-item correlation mean (0.68), which implies that items are correlated to a greater extent, and this scale has good reliability. For measuring element of ‘Membership and belonging’, we computed a scale consisting of four items: ‘Croatian/Italian citizen is a person who speaks Croatian/Italian’; ‘Croatian/Italian citizen is a person who keeps strong social relations with Croatians/Italians’; ‘Croatian/Italian citizen is a person who shares Croatian/Italian cultural codes’; ‘Croatian/Italian citizen is a person who donates money for civic purposes’. The reliability test for this scale according to Cronbach’s alpha is 0.77, which implies a good reliability of the computed scale. Additionally, we conducted a scale regarding specifics of nationality and origin consisting of three items: ‘Croatian/Italian citizen is a person who lives in Croatia/Italy’; ‘Croatian/Italian citizen is a person who was born in Croatia/Italy’; ‘Croatian/Italian citizen is a person who has Croatian/Italian descent’. The reliability test for this scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.61. Even though Cronbach’s alpha measured below 0.7, according to Pallant (2013), a scale reliability above 0.6 is considered an acceptable and moderate level of reliability8 (Brownlow et al. 2014). Finally, we composed a scale that measures how participants perceive their own religiosity, which is composed of four items measuring their levels of religiosity: ‘I am a religious person’; ‘I believe in God’; ‘My religious beliefs give my life a sense of significance and purpose’; and ‘My religious beliefs have a great influence on my daily life’. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale measures excellent reliability, previously 0.94 and with a good inter-item correlation 0.80) (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Reliability of computed scales, means and standard deviation for each item.

Furthermore, the Pearson correlation coefficient was computed to determine the relationship between each conducted scale and its variables. The Pearson correlation coefficient shows how much the ‘scores of two vary together and then contrast with how much they vary on their own’ (Brownlow et al. 2004, p. 297). Essentially, it shows the relationship between two variables, in our case between our dependent variable—‘Negative attitudes toward immigrants’ and all our independent variables, such as, cultural identification, religiosity, membership and belonging, etc. If the Pearson correlation shows a significant positive relationship between two specific variables, which is the case with all our variables (which can vary between low, medium, and high), meaning that as the level of agreement with one variable increases, the level of agreement with other variables in correlation increases as well. The results of the Pearson correlation test showed a significant relationship between our dependent variable ‘Negative attitudes toward immigrants’ and all our independent variables composing the scales, as well as with our single independent variable ‘Level of cultural identification’. More specifically, the results indicate that the relationship between ‘Negative attitudes toward immigrants’ and ‘Level of cultural identification’ is statistically significant and positive, measuring a small level of correlation (r = 0.13). Additionally, the results of the Pearson correlation coefficient showed a significant positive relationship between ‘Negative attitudes toward immigrants’ and ‘Level of religiosity’, indicating a medium correlation of 0.32. This means, the more they agree with the statements ‘I am a religious person’, ‘I believe in God’, ‘My religious beliefs give my life significance and purpose’, ‘My religious beliefs have a great influence on my life’, the more they have negative attitudes toward immigrants. With regard to the variables included in the scale, ‘Membership and belonging’, and our dependent variable, ‘Negative attitudes toward immigrants’, the Pearson correlation coefficient showed a small, but statistically significant positive relationship as well (r = 0.10). Finally, the Pearson correlation test showed a significant positive relationship between scale ‘Negative attitudes toward immigrants’ and ‘Elements of national identity and origin’, measuring a Pearson coefficient of 0.16; indicating a small correlation. Regarding the relationship between the developed scales, the highest Pearson coefficient was found between ‘Elements of national identity and origin’ and ‘Membership and belonging’, indicating a significant positive correlation of 0.37. For all scales and their items, the correlation between variables was indicated as positive, signifying that as the level of agreement with one variable increases, the level of agreement with the other variable also increases in correlation (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Pearson correlation coefficient of conducted scales9.

When it comes to cultural identification, we asked the participants to identify themselves with the culture of their country on a scale from 1 to 10 (1—weak identification with Croatian/Italian culture; 10—strong identification with Croatian/Italian culture). Only 1.2% of participants identified with 1 (weak identification) and 7.4% with 10 (strong identification), while the average answer of participants was around 7 (mean = 6.96) on the cultural identification scale. For participants who are not Croatian or Italian by citizenship, or have a different family origins, we also questioned to what extent (1–10) they identify with their culture of origin. From 484 respondents, some of whom do not hold citizenship (foreigners) and others culturally identified with their home country based on their family origins, 10% of the respondents weakly identified with their culture, scoring 1; 2.5% identified strongly with the culture of their origin and 4.7% marked their identification with 5 on a scale from 1 to 10.

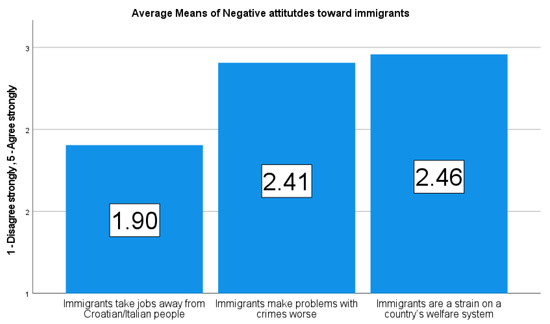

Additionally, we compared those participants (N = 337) that identified themselves with the culture of Croatia or Italy on a scale from 1 to 10, with 8 signifying a higher level of cultural identification, and explored their level of negative attitudes toward immigrants. For the statement ‘Immigrants take jobs away from Croatian/Italian people’, from 337 participants, 3.9% strongly disagree with the statement, 32% disagree, 15% are not certain, while 7.4% agree and 1.5% strongly agree. Additionally, regarding the statement ‘Immigrants make problems with crime worse’, from those that rated their cultural identification with an 8, 28.7% strongly disagree, 18.3% are not certain, while 18.9% agree and 3.6% strongly agree. Finally, with regard to the statement ‘Immigrants are a strain on country’s welfare system’, 28.4% of participants rating their cultural identification with an 8 strongly disagree, 24.3% only disagree, 24.9% are not certain, while 17.8% agree and 4.7% strongly agree. In terms of negative attitudes toward immigrants, on average, participants (N = 1227) disagree with the statement that immigrants increase criminality, are a strain on the country’s welfare system, and negatively influence job opportunities for Croatian and Italian people (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Average means of negative attitudes toward immigrants.

Regarding the frequency of church attendance as one of the aspects of religiosity and the relation to attitudes toward immigrants, among those that attend church almost every week, 27.9% are not certain and 18.9% agree that ‘Immigrants make problems with crime worse’; while 19.7% agree and 23.9% are not certain if immigrants represent a strain on country’s welfare system. Looking at some other aspects of attitudes when it comes to the position and purpose of religion and attitudes toward religious diversity, our participants usually had open minds and tolerance toward these issues. For example, 39.8% disagree and 5.8% of our participants agree that it is better to pay attention to the dominant religion and culture, while 44.2% believe that having people of different religiosity in the country is enriching.

4.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis of the Computed Scales

In our analysis of the data, each of the conducted scales was tested by exploratory factor analysis (EFA), computing the principal components method (PCA). Exploratory factor analysis is a statistical technique that relies on the linear correlation between variables in large sets of data (Brownlow et al. 2014). As Brownlow et al. (2014) claim, it is a procedure of summarizing or reducing data by analyzing the associations between variables to examine whether there are underlying factors (similar response patterns) and which factors are most important. EFA requires a sample of minimum 100 participants, and there should always be more participants than the variables (Brownlow et al. 2014), which is the case with our research. The principal component method (PCA) serves to obtain the clearest idea of how the original variables are associated with their factors, performing a method of rotating factors (Brownlow et al. 2014). In terms of computing the exploratory factor analysis, the authors Brown (2012) and Coolican (2014) highlight the need that the results of the EFA must fulfill two key criteria, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (KMO) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity, which measure the homogeneity of variance between test matrix and identity matrix. Following the assumptions for these two key criteria, Harrington (2009) suggests that the KMO statistics should be above 0.5, while according to Pallant (2013), Bartlett’s test must be statistically significant at the p < 0.05 level. Once these two key criteria were fulfilled, we proceeded with further aspects of the factor analysis, whereby, the total ought to be at minimum of 50% (Hair et al. 2010), while the communalities, which measure the amount of variance for each variable and should have a high common variance, usually a minimum of 0.4 or above (Yong and Pearce 2013; Costello and Osborne 2005). For our analysis, factor loadings below 0.3 were suppressed, and the Guttman–Kaiser criterion was applied, considering only the components whose eigenvalue would be 1.0 or above. For the scale ‘Negative attitudes toward immigrants’, the KMO statistic was 0.723 > 0.50, while the p-statistic for Bartlett’s test was statistically significant (p < 0.001), satisfying the criteria for both assumptions needed in order to carry out the analysis. According to the results of the conducted factor analysis, one factor was extracted, which explains 79.28% of the variance. Additionally, the results indicate that none of the communalities were less than 0.4, whereby for this specific scale, the minimum measurement was 0.723, followed by 0.821 and 0.826 for the third item in the scale, indicating that all of the communalities were much higher than the minimum expected and important for the efficient factor extraction. Following these assumptions, we proceeded with the analysis.

According to the exploratory factor analysis for the ‘Level of religiosity’ scale, the results of the KMO statistic are 0.822 > 0.50 and statistically significant, while Bartlett’s test of sphericity was statistically significant (p < 0.000), satisfying both criteria needed to proceed with the factor analysis. The analysis extracted one factor consisting of four items, which explains 85% of the variance, whereby all of the communalities were measured above 0.8, indicating that variables are well-represented by this one factor. The minimum measured communality was 0.812 for the item ‘I believe in God’; followed by 0.824 for ‘My religious beliefs have a great influence on my daily life’; 0.873 for ‘I am a religious person’, and finally, 0.891 for ‘My religious beliefs give my life a sense of significance and purpose’.

Furthermore, we computed a factor analysis for the following scales: ‘Membership and belonging’ and ‘Elements of national identity and origin’. Originally, we conducted one scale that consisted of seven items in total, listed in ‘Membership and belonging’ together with the items concerning ‘Elements of national identity and origin’, which on the reliability test measured a good reliability (0.74); however, the EFA extracted two factors for the composed scale, from which Factor 1 consisted of four items included in ‘Membership and belonging’ and Factor 2 consisted of three items included in ‘Elements of national identity and origin’ (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Rotated component matrix a.

According to this, we divided the seven items of membership, belonging, and national elements into two separate scales (see Table 2 for Cronbach’s alpha for each scale), and conducted an exploratory factor analysis separately for the scales. In the case of the scale—‘Membership and belonging’, which consisted of four items, the KMO statistic was 0.757 > 0.50, while Bartlett’s test indicated a statistical significance (p < 0.001), and in line with this, having met both assumptions, we proceeded with the analysis. The factor analysis resulted in extracting these four items of the scale as one factor, which explains 59.89% of the variance. All of the communalities measured above 0.4, whereby the minimum measured was 0.428; followed by 0.558 for the second item; 0.671 for the third; and finally, 0.738 for the last item of the conducted scale. Following this, we computed EFA for the scale ‘Elements of the national identity and origin’, and according to the results, KMO statistic measured 0.554 > 0.50, while Bartlett’s test of sphericity was statistically significant (p < 0.001). In line with these results, we proceed with the analysis, according to which one factor was extracted, explaining 59.96% of the variance. The lowest communalities measured 0.35710; followed by 0.612; and 0.739 for the third item (for Factor analysis results of all scales see Table 4).

Table 4.

Factor analysis results for computed scales—KMO, Bartlett’s test; variance explained.

4.2. The Effect of Religiosity and Cultural Identification on ‘Negative Attitudes toward Immigrants’—Regression Analysis

Bivariate regression analysis is a statistical method used to analyze whether one variable predicts another variable, specifically determining whether one variable will be more important in predicting variation within the dependent variable than the other, while the multiple correlation coefficient shows us the strength of this relationship (Brownlow et al. 2004). In our research, we used a bivariate regression analysis to see to what extent our independent variables can predict the variations in our dependent variable ‘Negative attitudes toward immigrants’. In our case, bivariate regression analysis was conducted for two different models examining its effect on negative attitudes toward immigrants. The first model included ‘Cultural identification’, ‘Level of religiosity’, ‘Membership and belonging’, and ‘Elements of national identity and origin’ in order to determine how these items predict ‘Negative attitudes toward immigrants’. For the second model, we added the variable ‘Frequency of religious practice’, which encompassed the frequency of church attendance and frequency of religious prayer. Cronbach’s alpha for the scale measuring the frequency of religious practice is 0.77, implying a good reliability of the computed scale.11 In the case of our first model, religiosity was defined through religious beliefs, while items measuring religiosity in the second model also encompassed the aspect of religious behavior/practice along with items measuring religious beliefs.

del 2 alysis for Model 1 and MOd origineach of the varibale icant positive relationship between all our variables, including as.

For our first model, the Pearson correlation coefficient results indicated a statistically significant positive relationship between all our independent variables (‘Level of Cultural identification’, ‘Level of religiosity’, ‘Membership and belonging’, and ‘Elements of national identity and origin’) and our dependent variable, ‘Negative attitudes toward immigrants’. The highest level of Pearson correlation coefficient was found between the variable ‘Level of religiosity’ and ‘Negative attitudes toward immigrants’ (r(1167) = 0.32, p < 0.001). In ‘Negative attitudes toward immigrants’ scores, 12.3% of the variance was explained by ‘Cultural identification’, ‘Level of religiosity’, ‘Membership and belonging’, and ‘Elements of national identity and origin’ (R square = 0.123) The results of ANOVA were statistically significant (p < 0.001), so the slope of our regression line is not zero, and ‘Cultural identification’, ‘Level of religiosity’, ‘Membership and belonging’ and ‘Elements of national identity and origin’ significantly predict ‘Negative attitudes toward immigrants’ (F(4, 1162) = 40.90, p < 0.001.12

The linear regression results show that the ‘Level of cultural identification’ has a statistically significant positive effect (p = 0.05), indicating that with higher levels of cultural identification, the levels of negative attitudes toward immigrants increase (B = 0.028); if ‘Level of cultural identification’ increases by one unit, negative attitudes toward immigrants will increase for 0.028 units, while all other conditions remain unchanged. Furthermore, a regression analysis indicated that ‘Level of religiosity’ also has a significant positive effect on ‘Negative attitudes toward immigrants’ (p < 0.001), which implies that a higher level of religiosity influences higher levels of negative attitudes toward immigrants (B = 0.205); if the level of religiosity increases by one unit, negative attitudes toward immigrants will increase by 0.205, while all other conditions remain the same. ‘Membership and belonging’ was non-significant, (p = 0.98), with a negative effect on negative attitudes toward immigrants (B = −0.001). Additionally, in the case of ‘Elements of national identity and origin’, the regression analysis showed a statistically significant, positive effect on negative attitudes toward immigrants (p = 0.001). In this sense, the more participants that perceive a citizen is a person who is born, lives, and comes from a specific country, the more they have negative attitudes toward immigrants (B = 0.127); According to Standardized Beta Coefficient, ‘Level of religiosity’ has the largest influence on ‘Negative attitudes toward immigrants’ (0.297).

The Durbin–Watson statistic is 1.787, whereby values ranging from 1 to 3, are acceptable according to Field (2009), signifying no autocorrelation between variables. According to the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test of normality, a significant finding of p < 0.001; indicates that the sample distribution is significantly different from the normal distribution. In this case, if the test shows that the data cannot be normally distributed and if the sample is larger than 30—that is, each empirical distribution of data weighs the normal amount by the central limit theorem: N > 30—the distribution of the data can be considered as normally distributed (Jovetić 2015). This was the case with our data, so we call upon the central limit theorem in the case of our sample, whereby for each item the number of participants exceeded 1000. The residuals are homoscedastic, meaning the assumption has been met.

For our second model, the Pearson correlation coefficient indicated a statistically significant positive relationship between all our variables, including the added variable—frequency of religious practice and our dependent variable ‘Negative attitudes toward immigrants’. The ANOVA was statistically significant, indicating that model 2, which includes ‘Frequency of religious practice’ significantly predicts ‘Negative attitudes toward immigrants, while the linear regression results for each of the variables shows that ‘Frequency of religious practice’ was non-significant (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Results of regression analysis for model 1 and model 2.

4.3. Differences between Croatian and Italian Participants in Negative Attitudes toward Immigrants—ANOVA

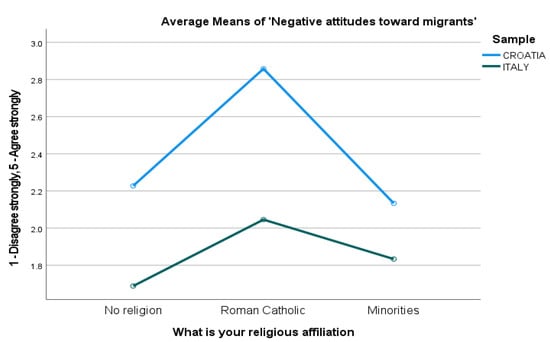

Conducting ANOVA allows us to compare various conditions of independent variables and to explore the effect of these conditions on our dependent variable, and as in other analyses, various assumptions must be met in order to perform it (Brownlow et al. 2014). In ANOVA, the null hypothesis indicates that there is no difference among group means. If the ANOVA results as statistically significant, means from the analyzed groups (in our case—‘Croatian/Italian participants’ and ‘Religious affiliation’) differ from the overall group means. In our research, ANOVA was performed to analyze the effect of ‘Religious affiliation’ and ‘Croatian/Italian participants’ on ‘Negative attitudes toward immigrants’. The results of ANOVA revealed that there was a significant interaction effect of ‘Religious affiliation’ and ‘Croatian/Italian participants’ (F(2, 1214) = 3.842, p = 0.022, η = 0.006. A simple main effects analysis showed that ‘Religious affiliation’ has a statistically significant effect on ‘Negative attitudes toward immigrants (p = 0.001, η = 0.057). Additionally, the main effect of ‘Croatian or Italian participants’ also has a statistically significant effect on ‘Negative attitudes toward immigrants’ (p = 0.001, η = 0.026).

In the case of participants from the Croatian sample, all three groups of religious affiliation (Roman Catholic, minorities and non-religious), on average have more negative attitudes than participants from Italy (see Figure 2). Croatian participants who affiliate as non-religious have lower levels of negative attitudes (mean = 2.23), than those affiliating as Roman Catholic (mean = 2.86), while participants belonging to minority groups have the lowest levels of negative attitudes toward immigrants in our Croatian sample (mean = 2.13).

Regarding Italian participants, those declared as Roman Catholics have higher levels of negative attitudes toward immigrants (mean = 2.05), while minority groups are more negative toward immigrants (mean = 1.83) than non-religious participants (mean= 1.69) (See Figure 3). Looking at the specific difference between Croatian and Italian participants, the results show that Croatian participants have more negative attitudes toward immigrants, and specifically, participants affiliated with Roman Catholic Church in Croatia are more negative than participants declared as Roman Catholic in Italy. The results show the same difference for those declared as non-religious in Croatia and non-religious participants in Italy (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Estimated means of ‘Negative attitudes toward immigrants’ of Croatian and Italian participants in three different groups (Non-religious, Roman Catholic and minorities).

5. Conclusions

Throughout this article, we attempted to look into the complexities of religious identities of two European, both predominantly Catholic countries, their different experiences of migratory issues, and how these affect attitudes toward immigrants. While Croatia still holds the position of a mostly emigrating country, Italy has experienced the opposite migratory events in the last two decades. These different developments, together with different historical encounters with democracy, have shaped the socio-political dimensions of these two societies, and consequently transformed national and religious identities, resulting in different levels of accepting multiculturality and religious pluralism. The aim of our study was to explore the interconnection and effect of religiosity and cultural identification on negative attitudes toward immigrants, among 1317 Croatian and Italian university students, with a tendency to examine the differences among students of these two countries. As different empirical studies have shown (Bohman and Hjerm 2014; Kumpes 2018; Čačić Kumpes et al. 2012; Scheepers et al. 2002) and as the results of our analysis indicate, religion and levels of religiosity proved to have a quite impact on the levels of negative attitudes toward immigrants. In our research, we tested two hypotheses, one concerning the correlation and the impact of religiosity and cultural identification on negative attitudes toward immigrants; and the other concerning differences between Croatian and Italian participants in their views toward immigrants, as well the differences based on religious affiliation. The first hypothesis: ‘Negative attitudes towards migrants are positively correlated with higher levels of religiosity and stronger cultural identification’, was tested by conducting a bivariate regression analysis, and the results show that higher levels of religiosity together with higher levels of cultural identification cause more negative attitudes toward immigrants. Our analysis showed that levels of religiosity, the level of cultural identification, elements of national identity and origin predict negative attitudes toward immigrants, while the Pearson correlation coefficient indicated a statistically significant, positive relationship between all our independent variables and our dependent variable—negative attitudes toward immigrants. More specifically, according to the results, the levels of religiosity proved to have the largest influence, implying that higher levels of religiosity result in higher levels of negative attitudes toward immigrants. Participants’ cultural identification with their country (Croatia/Italy) also proved to be statistically and positively significant, indicating that higher levels of cultural identification result in more negative attitudes toward immigrants, though with lower impact. For our second hypothesis: ‘Negative attitudes toward immigrants are stronger in Croatia than in Italy, and participants affiliated with the Roman Catholic Church in Croatia are more negative toward immigrants than participants affiliated with the Roman Catholic Church in Italy’, we conducted ANOVA, which implied that different religious affiliation (Catholicism, minorities, and non-religious) and differentiation based on country of origin (Croatia/Italy) has a significant effect on negative attitudes toward immigrants. More precisely, the results indicated that Croatian participants have more negative attitudes toward immigrants than Italian participants. This difference might be traced down to the fact that citizens of former communist countries tend to be more prejudiced, than the citizens of the countries with a longer tradition of democracy, thus the have more difficulty in accepting the diversification of society (Scheepers et al. 2002; Kumpes 2018). Furthermore, the analysis showed that Roman Catholic participants of both countries are generally more negative toward immigrants, while participants of Croatia declared as Roman Catholic have higher levels of negative attitudes than those of Italy. The same outcome was found for non-religiously declared students and students belonging to minority groups. Participants belonging to minorities in Croatia proved to be less negative than non-religious participants; while in the case of Italy, non-religiously declared participants were the least negative of all analyzed religious groups.

There are several empirical research studies that analyze the impact of religiosity on negative attitudes toward immigrants, but there is a significant lack of studies comparing two countries and exploring the topic of migration dynamics and religiosity. Any research attempt carries a range of limitations and biases whether it concerns data collection, methods, and procedures concerning analysis, sample size or sample type, or the sole interpretation of the results of the research. Regardless of this, each study, if it is conducted within the framework of research ethics, should be considered as a new horizon and new perspective in studying a certain phenomenon, and each research can open a range of questions and reflections that can lead to more profound research in future. Even though the sample used in our study is not representative, which certainly is a limitation when it comes to research methodology, our data provide an interesting window into something that is yet to be explored. Our research reveals only the surface of many unexplored topics, which leads us to pose several questions. Young people, usually identify more as non-religious, while they tend to endorse more the idea of freedom to change religion and freedom to have no religion (Giordan et al. 2020), which interestingly directs how these views and beliefs of young people could be reflected onto the views on immigrants and their reception within society. Focusing on young generations of students in two European Catholic countries and how religion can have an impact on their views toward immigrants, it is questionable to what extent the differences between young Croatians and young Italians are the result of two different historical encounters with the dynamics of migrations. Is it possible that Croatia’s non-migrant history produced more negativity toward immigrants due to the unfamiliarity, while Italy gradually assimilated to diversity due to constant immigrant flows? Did the Croatian war events in the 1990s produce such a strong sense of nationhood that the significant ‘other’ is not welcome anymore, while Italy’s long tradition of democratic values with a combination of constant immigrant flows caused Italy to more easily assimilate the challenges brought by migration dynamics? All of these questions are intertwined with the role of religion, the Church, and religious identities in both Croatia and Italy. In both countries, religion and the Catholic Church play an extremely significant role, not only within the public sphere of society but also within the individual private domain of life, though in different ways. The Catholic Church in both countries had significantly different answers and approaches to immigrant issues. The questions mentioned above emphasize the importance of exploring the issue of migration dynamics in relation to religion, especially within the sphere of comparative studies. In terms of future research and contributions to the study of the phenomena of religion and migrations, it could be interesting to broaden the spectrum of comparison, for example, to another country of former SFRY with different dominant religion than Catholicism, thus exploring more deeply the contextual differences and the impact of different religious contexts on negative out-group views. Additionally, the interconnection of the views on immigrants and religiosity could be further developed and explored by looking into the views on different dimensions of religious freedoms, in different country contexts.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data from this study are not publicly available or archived, the data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | National Bureau for Statistic, Croatia, https://podaci.dzs.hr/2021/hr/9939, accessed on 29 April 2022. |

| 2 | ISTAT Italy’s Resident Foreign Population 2011 https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/40658#:~:text=Resident%20foreigners%20in%20Italy%20totalled,previous%20year%20(%2B7.9%25), accessed on 26 June 2022. |

| 3 | ISTAT National Demographic Balance Report 2019 https://www.istat.it/it/files//2020/07/Statistica-report_Bilancio-demografico_anno-2019-EN.pdf, accessed on 20 January 2022. |

| 4 | ISTAT Residence Permits of non- EU citizens 2020 http://dati.istat.it/Index.aspx?QueryId=19721&lang=en, accessed on 20 January 2022. |

| 5 | ISTAT Annual Report 2021 https://www.istat.it/it/files//2021/09/Annual-Report-2021_Summary_EN.pdf, accessed on at 20 January 2022. |

| 6 | https://www.thearda.com/internationalData/countries/Country_115_2.asp, accessed on on 28 January 2022. |

| 7 | These items were incorporated into the SPRF instrument from the European Values Study (EVS) https://europeanvaluesstudy.eu/, accessed on on 28 January 2022. |

| 8 | Originally we conducted one scale which consisted of items listed in ‘Membership and belonging’ together with the items concerning ‘Elements of national identity and origin’, which on the reliability test measured good reliability (0.74), but the EFA extracted two factors for the composed scale, from which Factor 1 consisted of items included in ‘Elements of national identity and origin’ and Factor 2 consisted of items included in ‘Membership and belonging’ (see Section 3.1 for the detailed explanation). |

| 9 | If the test shows that the data cannot be distributed normally and if the sample is larger than 30, that is, each empirical distribution of data, by the central limit theorem, weighs the normal, and by that for N > 30, the distribution of the data can be considered as normally distributed (Jovetić 2015). This was the case with our data, so we call upon the central limit theorem in the case of our sample whereby for each item in our scales the number of participants exceeded 1000, which allows us to conduct the Pearson Correlation coefficient test. |

| 10 | It is advisable to remove any item with a communality score less than 0.2 (Child 2006). Items with low communality scores may indicate additional factors which could be explored in further studies by developing and measuring additional items (Costello and Osborne 2005). |

| 11 | Scale measuring ‘Frequency of religious practice is consisted of two items: ‘How often do you pray at home or by yourself’ (Mean = 2.56; SD = 1.95) and ‘How often do you attend a religious worship service’ (Mean = 2.26; SD = 1.40); * Response scale for ‘How often do you pray’: 1—never; 2—Occasionally; 3—A few times a year; 4—At least once a month; 5—Nearly every week; 6—Several times a week. * Response scale for ‘How often do you attend religious service’: 1—Never; 2—Occasionally; 3—A few times a year; 4—At least once a month; 5—Nearly every week; 6—Several times a week. |

| 12 | The equation for the regression line is: Negative attitudes toward immigrants = 1.090 + 0.028 × ‘Level of cultural identification’ + 0.205 * ‘Level of religiosity’ − 0.001 * ‘Membership and belonging’ + 0.127 * ‘Elements of identity and origin’. |

References

- Bogdanić, Ana. 2004. Multikulturalno građanstvo i Romkinje u Hrvatskoj. Migracijske i etničke teme 20: 339–65. [Google Scholar]