1. Introduction

Soft power has been a valuable instrument for the international relations and foreign policy of small states (

Chong 2010). The United Arab Emirates (UAE) has used many tools in line with small state theory, such as foreign aid, investment, and public diplomacy (

Krzymowski 2022;

Ulrichsen 2016). Since the beginning of the 2000s, particularly after the mass protests in the Middle East, the UAE has been involved in hard power initiatives in addition to its soft power tools, both directly and with proxies (

Salisbury 2020). The involvement has been twofold: political and ideological. The political involvement has been through military and financial tools, such as funding Egypt’s Abdel Fattah el-Sisi (overthrowing the first democratically elected Muslim Brotherhood (MB)-affiliated president, Mohammed Morsi) and initiating a blockade on Qatar (

Telci and Öztürk Horoz 2021).

The ideological involvement has included religious discourse to counter the thoughts of the Muslim Brotherhood and political Islam more broadly (

Davidson 2019). Tolerance, moderate Islam, multiculturalism, fighting extremism, and the fight against terrorism are among the rhetoric being promoted in the Emirati desired version of Islam (

Kourgiotis 2020). The UAE has used these notions through different means, such as creating the first-ever Ministry of Tolerance and reserving a full year for tolerance (Year of Tolerance 2019). Creating alternative Muslim institutions, such as the Forum for Promoting Peace in Muslim Societies, the Emirates Fatwa Council, and the Jurisprudence of Peace, is among the initiatives that the UAE has implemented to achieve its goal. The UAE has also supported well-known scholars such as Hamza Yusuf and Abdallah bin Bayyah (

Diwan 2021;

Guéraiche 2019;

Warren 2021). Therefore, this study examines how the UAE has utilized peaceful discourse by religious individuals and institutions to create a fallacy of uniting all ideologies as extremist or terrorist. The UAE, by taking these measures, aims to counter domestic and regional rivals and appeal to the West by constructing an image that complies with the standards of the international community (

Kourgiotis 2020).

Several interdisciplinary methodologies have been applied throughout the research to elucidate how the UAE utilized its version of Islam through institutions and individuals. The critical discourse analysis method is preferred, as the study mainly deals with the speeches and fatwas of selected scholars. The analyzed information is principally excerpted from the institutions’ websites, scholars’ social media accounts, religious events, declarations, conferences, and publications using search engine optimization tools.

This study benefits from the online sphere in a dramatic way, including online fatwas, preaching with the help of digital platforms (YouTube and other social media), and the merging of traditional activities (symposiums and conferences) with online technology, as social media has emerged as a new tool that is relevant to both quantitative and qualitative methods (

Snelson 2016;

Marcotte 2016). The analyzed fatwas, videos, and texts are in both Arabic and English. The videos and appearances of Yusuf and bin Bayyah are the primary sources, as their discourse is the main concern of this study. The Arabic sources were transcribed and translated by the authors, unless otherwise specified. Even in English videos, the individuals occasionally use Arabic statements, especially when they provide quotations from verses of the Qur’an or narrations of the Prophet Muhammed.

Because fatwas remain an important concept for Muslims, and even for non-Muslims in the West, this study deals with fatwas, as well as fatwa-like statements (

Maravia et al. 2021). The fatwas of bin Bayyah and Yusuf, important religious figures in UAE-based institutions, aim to reverse the unfavorable status of previous fatwas by promoting “tolerant” and “peaceful” discourse. In this study, fatwas issued by these scholars, along with their signatories’ texts, are examined under specific themes including obedience to the leadership and inter-religious dialogue.

In order to elucidate the main argument, this study is divided into three main parts. The first part introduces the theoretical background of religious soft power with the specific literature regarding the UAE. The second and third parts of the study examine the UAE’s religious soft power through individuals and institutions, respectively. The former focuses on bin Bayyah and Yusuf, while the latter discusses the Forum for Promoting Peace in Muslim Societies and the Emirati Fatwa Council.

By studying the UAE’s religious soft power, this study seeks to contribute to a number of different areas of research. Firstly, regarding the religious soft power literature, it contextualizes how the UAE created a transnational religious network by co-opting Western concepts and legitimizing its conflicts with Western terms. In this sense, the study presents how non-Western states negotiate a place in international relations. Secondly, in terms of the published research on small states, the UAE’s religious soft power shows how a small, young state can brand itself as a religious hub despite being situated between Iran and Saudi Arabia. Thirdly, the Gulf literature is rich in studies on the use of tools such as foreign aid, foreign direct investments, and diplomacy by the UAE and other small Gulf states. However, there is a substantial lack of studies on the use of religion as a tool, particularly in the UAE. While some studies examined Qatar’s use of religious soft power by focusing on the Muslim Brotherhood and Al Jazeera’s religious shows, most of the literature on the UAE is about how the country fought with the MB’s ideology and, in this case, Qatar (

Freer 2015,

2017,

2018;

Obaid 2019;

Roberts 2014a,

2014b,

2017,

2019).

2. Theoretical Conceptualization of Religion as Soft Power

The role of religion in political science and international relations was mainly undermined by the inspired social science theories of Marx, Weber, and Durkheim, which suggest that religion is a matter of the past, leading to the popularization of secularization theory (

Bellin 2008). The expectation that religion would fade away in the face of advanced industrialization, urbanization, and bureaucratization proved to be wrong, as many issues regarding religion still have a significant role in domestic and international affairs, from the religious legitimacy of leaders to the existence of religious states, and from transnational religious movements to nonstate religious actors, including religious fundamentalism, ideologies, and holy places (

Sandal and Fox 2013, pp. 12–29). The most important event was 9/11, with the subsequent securitization of Islam in the West (

Haynes 2021a), and these are important for this study for two reasons: (1) the fact that some of the hijackers on 9/11 were Emirati nationals, and (2) the UAE participated in other forms of securitization of Islam whenever it needed to legitimize its actions, just like Bush’s “War on Terror” and counter-extremism laws in the UK and France (

Breeden 2021;

Greer 2010).

Post-9/11, the UAE found an opportunity to co-opt its own version of Islam to avoid US pressure and also to repress alternative Islamic groups and thoughts, which finally left the UAE as a monopoly in religious affairs as well (

Ozgen and El Shishtawy Hassan 2021). The state increased its pressure on members of the General Authority for Islamic Affairs and Endowments (responsible for all mosques and religious institutions in the country) to reveal whether they had any links to “prohibited political groups”, while prohibiting unofficial religious activities and establishing antiextremism organizations such as the Hedaya Foundation and Sawab Centre. Additionally, it was argued that the Muslim Council of Elders and the Federal Fatwa Council were established to ensure the control of fatwas (

Ozgen and El Shishtawy Hassan 2021, p. 1185).

The emerging literature aims to bring an understanding of religion to the discipline of international relations and political science and to conceptualize religion within theoretical and empirical works in Western states (

Bellin 2008;

Haynes 2021a;

Ozkan 2021;

Sandal and Fox 2013;

Snyder 2011;

Toropova 2021). Some of the Gulf states, particularly Iran and Saudi Arabia, have been particularly important in terms of using religion in foreign affairs, Shi’ism for the former and Wahhabism for the latter (

Mirza et al. 2021;

S. Yakar 2022, pp. 2–5). Both states have a goal to represent their country as a center of Islamic teachings and to initiate spreading it beyond their boundaries (

S. Yakar 2020, pp. 226–27). Situated between these two countries, the UAE initially filled the lacuna of a lack of ideology with borrowed ideologies and Muslim Brotherhood-led Islamism, and sometimes by leaning towards Arabism, particularly when it needed to sympathize with Arab cases such as Palestine (

Freer 2015;

Winter 2022).

Moyser developed three kinds of relationships between religion and politics: (1) politics controls religion and religious institutions, (2) religious authority controls politics, and (3) both coexist together (

Beyers 2015;

Moyser 1991). While any generalization would be problematic, the Gulf states have experienced different kinds of relationships, as the region, in a broader sense, contains Iran, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Qatar, and the UAE. While Iran and Saudi Arabia are controversial in terms of their relations (

E. E. Yakar 2020), the UAE undisputedly opted for the first type, in which political power is the sole authority and is legitimized by religion. The cases in this study will show how the activities of individuals and institutions are used to increase obedience to the rulers (

al-Azami 2019). This obedience went as far as persecuting the Syrian protesters, as they did not obey the rulers (

Hamza Yusuf Issues Apology for ‘Hurting Feelings’ with Syria Comments 2019) and placing all protestors during the Arab Spring under one umbrella by calling them illegitimate (

al-Azami 2019).

Religion has been a matter of discussion with regard to both soft and hard power. The most common examples of using religion as a topic for hard power can be seen in both historic and modern cases. Historical cases include the Crusades, the French Wars of Religions in the 16th century, and a series of wars that ended with the Peace of Westphalia, an agreement that is considered to be the foundation for current secular international relations (

Knecht 2002, pp. 1562–98;

Kouri and Scott 1987;

Latham 2011). However, supposedly secular post-Westphalia was also awash with religious hard power initiatives. Even though all have different interpretations, many incidents which involve hard power revolved around religious discourse, from the Iranian Revolution of 1979 to the events of 9/11, from the US invasion of Afghanistan to its infamous war on terror, from state repression of Muslims in Sri Lanka to war in Yemen (

Devotta 2018;

Ozkan 2021;

Yang and Li 2021).

Even though not all of the above events are clear-cut examples, whether they were mainly religiously motivated or not, it is an indisputable fact that religion has been significant in terms of discursive and practical aspects. The soft power aspect of religion is also problematic in terms of drawing a line between its soft and hard sides. Therefore, the use of religion in power is not always straightforward and may have an ambiguous status if it eases the state’s use of hard power and authoritarianism (

Ozturk 2021). The UAE’s relationship with religion is also similar to Ozturk’s definition of ambiguity. For example, the UAE has used religion as a reason to cut its diplomatic relations with Qatar for more than three years. Its military operation in Libya was justified by the rise of that country’s Islamists, and the Yemeni operation was shown as the counter to Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). Government propaganda attempts to label outsiders as extremists and promote its own “tolerant” Islam (

Mason 2018).

Soft power was defined by Joseph Nye as “getting others to want the outcomes that you want—co-opts people rather than coerces them” (

Nye 2004). Nye considers three resources of primary importance for a country’s soft power: culture, political values, and foreign policies (

Nye 2004, p. 11). Religion, however, does not receive enough attention in Nye’s conceptualization of soft power. Even in culture, Nye examines the roles of education, popular culture, media, literature, and art (

Nye 2004, p. 11). In other parts, how Nye deals with religion relates how the media and the movie industry can change perceptions regarding religion among the general public, such as the evil image of Islam in Hollywood movies (

Nye 2004, p. 15). Nye does not ignore religion as a soft power. Rather, he considers it as a concept that can harm soft power by increasing it. Nye states:

For centuries, organised religious movements have possessed soft power. The Roman Catholic church is organised on a global scale, and many Catholics around the world adhere to its teachings on issues like birth control and abortion because of attraction, not coercion. Other religious organisations—among them Protestant, Islamic, and Buddhist—have extensive missionary efforts that have attracted millions of people to adhere to their teachings, particularly in Latin America and Africa in recent decades. But as we saw in the last chapter, intolerant religious organisations can repel as well as attract. In some circumstances, aggressive proselytising can destroy rather than create soft power.

Jeffrey Haynes is among the first scholars that attempted to fill the gap of what Nye neglects in soft power, i.e., religious soft power (

Haynes 2021a,

2021b). Haynes suggests that 9/11 and subsequent conflicts were not merely the West versus Islam, but conflicts within Islam (a minority version versus the mainstream) (

Haynes 2010). Haynes argues that while the US suppresses extremists, referring to Al Qaeda, it is necessary to use soft power tools to avoid the fight being presented as the religious US against Islam (

Haynes 2010). This is an important point of awareness for the UAE as well. Aware of this suggestion, the UAE promoted its version of Islam as the tolerant and moderate one which fights against extremism even if it includes hard power in its foreign affairs, such as in Libya and Yemen, which uses the rhetoric of fighting against extremism.

By analyzing annual soft power reports, one can see that the UAE has had a successful soft power campaign. The Global Soft Power Index 2020 by Brand Finance shows that the general public is more positive towards the UAE than the experts. While the report attributes the UAE’s biggest soft power success to its business and economic environment, it states that the experts and the audience differ in their perception of international relations. The report states, “International relations are not seen as especially strong by specialist audiences, but the general public is less aware of this and acknowledges the UAE’s international engagement” (

Global Soft Power Index 2020 2020).

Being a small state surrounded by two militarily and ideologically superior powers, Iran and Saudi Arabia, pushed the UAE to develop an alternative strategy for survival (

Miller and Verhoeven 2020). The UAE’s small state strategy includes promoting moderate Islam both domestically and throughout the region (

Kourgiotis 2020). Moderate Islam domestically legitimized the crush of the Islah movement, a branch of the Muslim Brotherhood, while regionally legitimizing its interference in Yemen, Libya, and Bahrain, in the fight against extremism and terrorism, either through Shi’a- or MB-led movements.

The UAE’s quest to use religion for domestic and regional legitimacy should not be underestimated. As Nukhet Sandal and Jonathan Fox argue:

Legitimacy has proved to be a powerful tool in international relations. The key in this process is to make the other actor feel morally obligated to support one’s policies. While it would be naive to argue that all actors in international politics behave morally, it would be equally naive to argue that engaging in an action that is seen as immoral and illegitimate does not have consequences. Thus, legitimacy and morality clearly have an impact on behaviour.

However, the aspects of public diplomacy and soft power involved in the promotion of moderate Islam are beyond pure legitimization. We should remember that the UAE’s increasing influence is a new phenomenon in the region, partly as a result of the fall of other regional powers and partly due to the investments that it made to gain this influence, with either foreign aid, diplomatic initiatives, or foreign direct investments. All of these tools challenge the limited capacity of small states, as expected by traditional international relations theory (

Almezaini 2012;

Antwi-Boateng and Alhashmi 2021;

Cochrane 2021;

Gokalp 2020;

Krzymowski 2022).

3. The UAE’s Attempt to Create a Network of Scholars: Hamza Yusuf and Abdallah bin Bayyah

Individual activities remain important in strengthening religious doctrines. The UAE, aware of the importance of scholars, aims to associate with renowned worldwide scholars with its Islamic doctrine. Since the beginning of Arab Spring, the UAE has promoted several people, including Hamza Yusuf, Abdallah bin Bayyah, Wassem Yusuf, and Habib al-Jifri.

The scholars who are affiliated with UAE-based institutions share common ideas and thoughts. Some of the mutual purposes are to promote inter-religious dialogue and tolerance, support rulers at the expense of revolutions and mass protests (obedience to the rulers), foster close relations with the West, and promote the UAE by either praising it or taking a role in state-funded projects and institutions (

Davidson 2019;

Miller and Verhoeven 2020). Yusuf and bin Bayyah are two significant religious figures through whom the UAE’s version of Islam can be understood by their identical interpretations and mutual support of the same institutions and projects.

3.1. Hamza Yusuf: Ultimate Legitimizer of the Regimes

Hamza Yusuf is one of the most influential Muslim scholars in the Western world. In 2009, he cofounded Zaytuna College in Berkeley, the first accredited Muslim college in the US. Yusuf has been in a position in which he is assumed to represent Muslims in the US. Yusuf has had deep and profound connections to several US administrations (

Edah-Tally and Ullah 2019;

Schleifer et al. 2021, p. 89;

Zaytuna College 2019b, mint. 39:38–51:52). Having engaged with the US administration since the 1990s, he became popular in the West in terms of the representation of Muslims (

Alfaham 2019;

Zaytuna College 2019a, mint. 1.35–7.00). The Guardian described Yusuf as “arguably the West’s most influential Islamic scholar” (

O’Sullivan 2001). His Islamic views and interpretations are considered to be representative of the UAE’s official Islamic doctrine. The close connection is supported by the opinion that Yusuf takes part in Emirati-funded organizations and activities. Like bin Bayyah, Yusuf supports obedience to the political power and the discourse behind the coexistence of Abrahamic religions.

Born in the US as a practicing Irish Catholic Christian, Yusuf converted to Islam in 1977, after a car accident in which he nearly died. Before becoming a Muslim, he was a student in the Western educational system. After his conversion, Yusuf received Islamic education in Tunisia, Saudi Arabia, Mauritania, Algeria, and the UAE. During his trainings in Middle Eastern countries, Yusuf directly engaged with prominent Islamic scholars, including Abdallah bin Bayyah, Sheikh Murabit al-Hajj, and Sheikh Salih al-Ghursi, who influenced him greatly.

Yusuf is among the most influential Islamic figures in the Western world, for three reasons. Firstly, he has engaged with administrations in the White House with both Democrat and Republican administrations. Secondly, he knows American society well, since he has lived there. Yusuf promotes liberal Islam in the US, which totally complies with the norms and standards there. Therefore, the Islam that is proposed and presented by Yusuf does not collide with US society, allowing him to gain influence. Thirdly, Yusuf is a cofounder and the current president of Zaytuna College in Berkeley, the first and only accredited Muslim liberal arts college in the USA. In this regard, Yusuf’s educational activities are easily distributed into US society.

3.1.1. Emphasis on Leadership and Obedience Doctrine

Right before the invasion of Iraq during the Bush administration, Yusuf was invited to the White House with other religious leaders and thus is widely known as a legitimizer of the war. Even though Yusuf later claimed that he wrote a letter recommending not going to war against any Muslim state, as 9/11 was not a state act, he is widely known for his legitimization (aware of this fame, Yusuf claimed it was a result of misinformation). He stated that there was no war during his visit to the White House, and Bush only informed him about a limited operation named Infinite Justice, which was intended to find out who was responsible for 9/11. Yusuf proudly recounted the anecdote that he rejected the proposed name Infinite Justice, as he thought only God has infinite justice. He and other religious scholars discussed the name, and it was only Yusuf who had the courage to suggest a name change (

Zaytuna College 2019b, mint. 40.00–45.00).

Yusuf’s engagements with the White House were not limited to Bush’s invitation. He engaged with the Obama and Trump administrations, which is legitimized by religious reasoning as it emphasizes obedience to the political power. He quoted a Prophetic narration in Arabic which states, “Whoever wants to give sincere advice to political authority, let him not do it openly. If he listens, the man gets the reward of providing sound advice. If he does not, you have fulfilled your responsibility of just giving sincere advice”. Moreover, he said, “My only intention was to give sincere advice”. Yusuf also referred to another quotation from the Prophetic narration which states, “Don’t curse people in authority, don’t deceive/cheat them, don’t hate them because God put them over you. Have patience and know the day of judgment is very close” (

Zaytuna College 2019a).

His view regarding the legitimacy of authority and obedience to it is also desirable for the UAE’s version of Islam. For example, Yusuf considers US laws to be the legitimate rules for the US, similar to Islamic law (

sharī’a). He claims that Muslims must obey God, the Prophet, and those in their authority (

Zaytuna College 2019b, mint. 49.50–47.00). Because the UAE’s political system lacks significant religious justification, Yusuf’s emphasis on political leadership itself is important for the UAE to rectify the lack of religious power. Yusuf later praised the UAE’s project of creating the Emirates Fatwa Council as being solely responsible for Islamic issues in the country.

Yusuf shared an anecdote about something that shocked him regarding the attitude of Muslim communities towards obedience to leadership. The fact that he was shocked shows how important obedience to the rulers is to him. The incident he shared occurred in the Mecca Great Mosque. When the Imam prayed for the Quds, the audience said “Amin” with enthusiasm, but when the Imam prayed for the rulers, the “Amin” was unenthusiastic, which surprised him, as he considered prayer for the rulers more important than prayer for the Quds (

Quran Vid 2018a, mint. 17).

He said, “Muslims, by consensus of our scholars, are obliged to obey the laws of the land. If they are secular laws, they have to obey them. Everything else excluding committing the forbidden must be done” (

Zaytuna College 2019b). His view of secularism is also worth mentioning, as he considers the secular government to be the most similar to Islam. Regarding secularism, Yusuf has said, “I found seculars more moral than most conservatives” (

سكاي نيوز عربية 2018, mint. 32.00).

1 He differentiates secularism and laicism and argues that secularism does not launch wars against religion. In this sense, Yusuf legitimizes the UAE’s secularism-oriented foreign policy.

Yusuf sides with a counter-revolutionary policy that the UAE supported during most of the Arab Spring. For example, speaking about the Syrian revolution in 2016, he said, “If you humiliate a ruler, God will humiliate you”. This statement partly legitimized the status of immigrants, including the protestors, especially those who sought refuge in other countries. During the first phase of the protest, the Syrian people shouted that they would not be humiliated. Yusuf mocked the refugees by stating, “Now, they are, Syrians, poor and begging non-Muslims to let them into their countries” (though he later apologized for his remarks) (

Hamza Yusuf 2019).

He has said that he is not a fan of Saddam or other authoritarian leaders, but says he understands why they were in those palaces. He also claims that Muslims are not capable of governing themselves. By supporting these ideas, he promotes political quietism (

Al-Anani 2020). He submits to dictators and human rights violators by referring to a commentary in the Qur’an: “The dumbest person is the one who prays against the ruler” (

Quran Vid 2018a, mint. 16.40–18.00). He clarifies his view on revolution by quoting Malik ibn Anas (d. 179/795): “Our scholars are very opposed to revolution because they believe that if you are under pressure and can’t change it, be patient; rewards will be in paradise. Oppression is a test or exam” (

Ahmed Elabyad 2021).

Yusuf’s view of political Islam parallels the UAE’s foreign policy. Yusuf blamed political Islam for seeking “the chair of the ruling”. Regarding this desire, he claims that Muslim rulers avoid being involved with Islam, as they fear that political Islam will benefit from such involvement. However, Muslim scholars in the past never aimed to rule, since their main purpose was to lead the community in the Islamic way (

Quran Vid 2018a, mint. 12). Therefore, he opposes the idea of political Islam and blames political Islamists as being the reason for or source of communists and fascists (فرانس 24/FRANCE 24 Arabic 2019, mint. 14.00–15.00).

2Yusuf categorizes Islamic groups in three ways: the first is the political Islamist group, the second group comprises people who reject the Islamic inheritance, and the third group consists of moderate people who do not reject the inheritance while also adopting contemporary conditions. Yusuf considers himself as the member of the third group, which he believes is the most accurate one, and considers the combination of the first two as dangerous, given that ISIS-like groups emerged from this combination (

سكاي نيوز عربية 2018, mint. 36.00).

3 3.1.2. Coexistence, Tolerance, and Interfaith Dialogue

Speaking at the Muslim Peace Forum in 2018 in Abu Dhabi, Yusuf promoted the idea of living in harmony (with other religions) by referring to the life of the Prophet Mohammad. He said that the whole life of the Prophet was about constructing or regaining what had been lost about civil society. The Prophet’s ultimate message in Madinah was to spread peace (

Islam Rewards 2018). During his speech at the Muslim Peace Forum, as vice president of the organization, Yusuf stated that Ibrahimic faiths do not exclude the faiths of other believers because they share profound areas (

Islam Rewards 2018). Regardless of the theological reasoning or debate, the “Abrahamic” discourse is important, as the UAE frequently uses it; for example, the agreement which normalized relations between the UAE and Israel was named the Abrahamic Accords to indicate that it was a result of tolerance and inter-religious dialogue.

Yusuf considers that war (

jihad) is not a concept that can be used all the time. In promoting peace more than war, he said that the Prophet was not a warrior, but he was allowed to fight (فرانس 24/FRANCE 24 Arabic 2019, mint. 24.00).

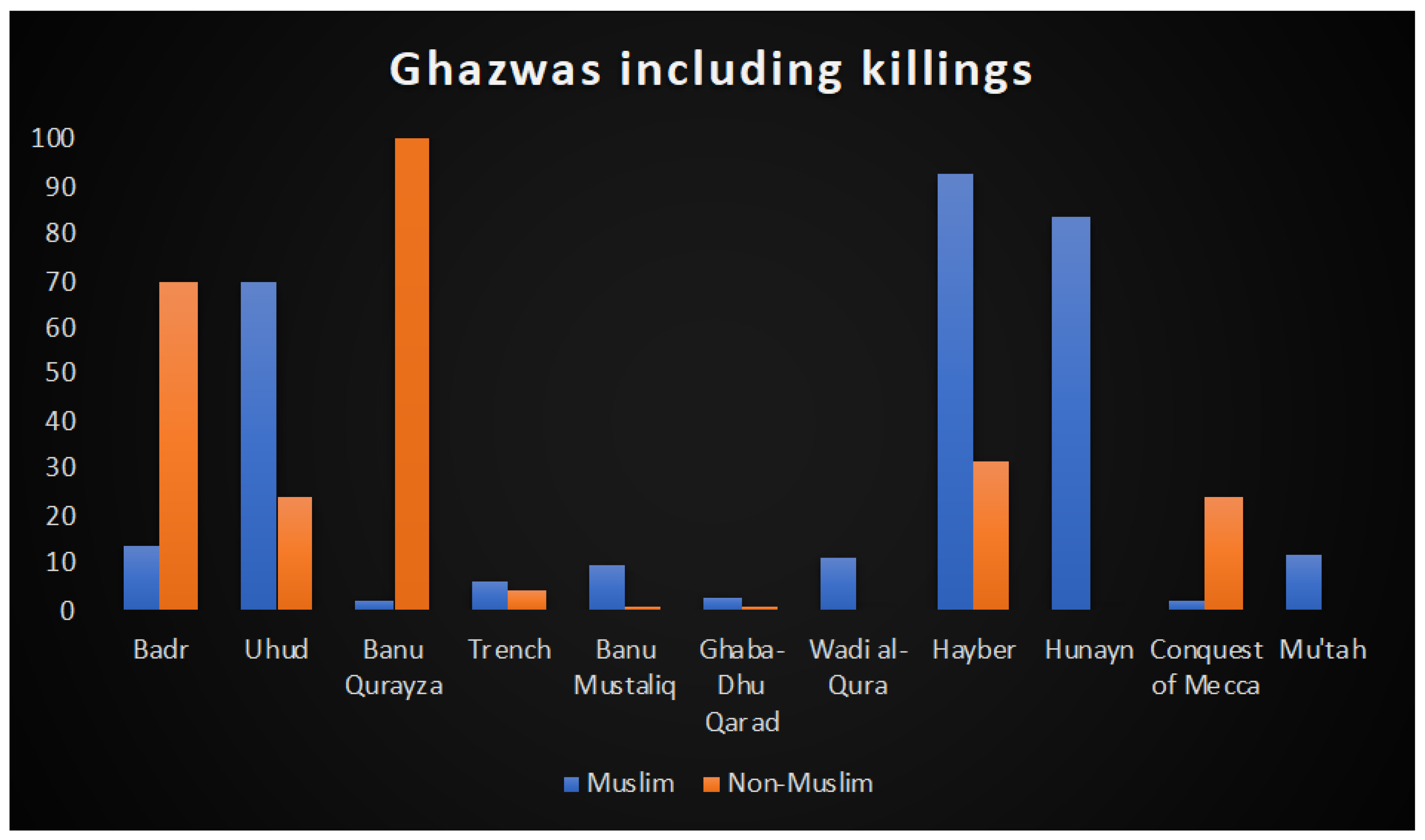

4 Over 23 years, the Prophet participated in 29

ghazwas, and in only 11 of them killing took place (

Quran Vid 2018a, mint. 6.00). In the Battle of the Trench, one of the deadliest battles, only six companions died. During those 23 years, only 200 companions died during the conflicts (

Quran Vid 2018a, mint. 7.00).

In this sense, Yusuf gave a presentation titled “The third axis: Rooting peace in Islam: the ruling texts (values–concepts–rules–means)”, in which he showed some of the historical realities. He said that the time of Mecca was full of patience, tolerance, and worship. Muslim companions were tortured by unbelievers and infidels. It was at the time of Madinah that Muslim believers were allowed to fight against unbelievers. Therefore, the jihad against infidels was by permission rather than an order (Forum for Promoting Peace

منتدى تعزيز السلم 2015a).

5Yusuf argues that even during the time of Holy Battles, killing was considered an undesired result. That is why most of the Holy Battles of the Prophet did not end with killings. During his presentation, which was in Arabic, Yusuf stated that “if we don’t include Holy Battle of Banu Qurayza, more Muslims dead than non-Muslims”.

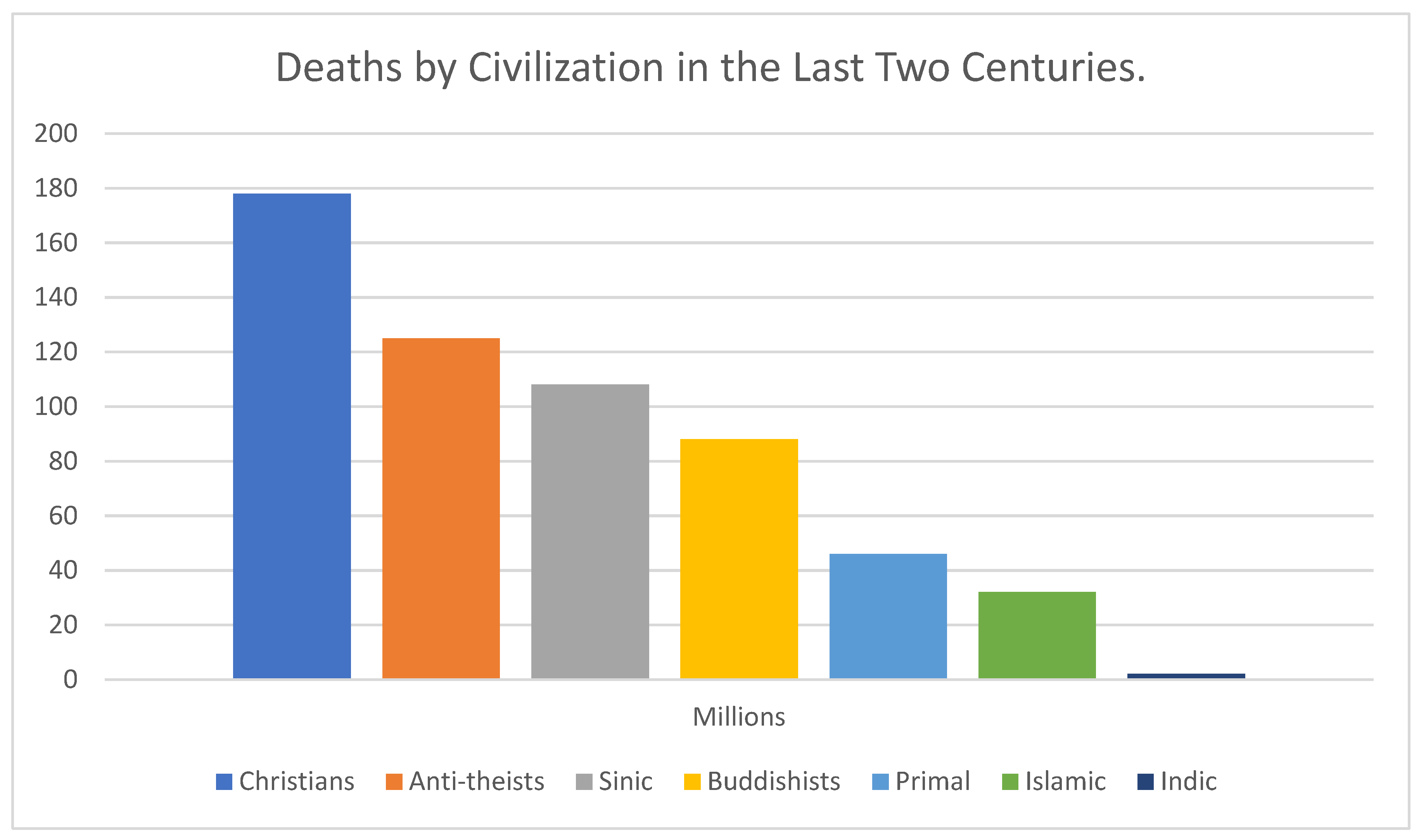

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 illustrate that Islam as a religion and civilization is less violent and murderous than other religious civilizations according to Yusuf (Forum for Promoting Peace

منتدى تعزيز السلم 2015a, mint. 10.00).

6 Because Islam represents only 5% of killings and violence, it is a religion that complies with the coexistence of other religions. In this sense, Yusuf utilizes Islamic historical reality to reflect what the UAE targets.

In this sense, Islam is one of the least violence-oriented religions. Moreover, Yusuf argues that Islam has never promoted killings and violence.

The Alliance of Virtue (known as

Hilf al-Fudul, League of the Virtuous) came out of the matrix of Islam and is not alien to other traditions. Yusuf says the Prophet allied with the Jews and the Christians, which means he does not consider religion as something that left believers in an antagonistic relationship with others (

Islam Rewards 2018, mints. 3.50). The Prophet worked with a pagan believer to solve the issue. By referring to the Prophetic example, he supports the idea that a Muslim believer can work with trustworthy Jews or Christians. When the Prophet migrated to Madinah and established a state, he did not bind these entities according to their faith. Instead, he constructed the forms based on citizenship. According to Yusuf, bin Bayyah considers that the US Declaration of Independence is based on the same mentality (

Islam Rewards 2018, mint. 5.00).

He says the Prophet sat in the house of Midrash, the masjid for the Jews in Madinah, and engaged with the Jews and Christians. He allowed them to practice their worship at the Masjid al-Nabawi. Yusuf says the Prophet was a dialogist called to the dialogue. He refers to a verse from the Qur’an: “Argue with them in a way that is best”. Exegetical scholars interpret “argue” to mean “dialogue”. He says that, here, we understand that Allah calls Muslims to use a good method for making a dialogue with non-Muslims (24

فرانس/FRANCE 24 Arabic 2019, mint. 41.00).

7 Yusuf attended another seminar in the US that talked about the Ibrahimic faith. Robert George, with whom Yusuf worked on many issues, says that Ibrahimic belief is common within divine or Abrahamic religions (

Berkley Center 2012;

Hamza Yusuf 2017a, mint. 10.00;

Rabwah Times 2015).

3.2. Abdallah bin Bayyah: Ultimate Supporter of Tolerance

Abdallah bin Bayyah, a Mauritanian scholar, has political experience and global religious fame. Bin Bayyah is one of the key persons whom Yusuf admires and takes as an exemplary role model. Yusuf considers bin Bayyah to be the second most influential person with regard to his intellectual enhancement, after Murabit al-Hajj. Bin Bayyah was the Minister of Justice in Mauritania, and his father was a judge during the French colonial period. Bin Bayyah went to Tunisia to study French law and earned a master’s degree in European and Islamic law. He has served in many ministerial positions in Mauritania, in addition to writing the country’s constitution.

He worked as the senior member of the ruling party, the Mauritanian People’s Party, for eight years (

Parker 2018), which gave him experience in political engagement (

Zaytuna College 2019b, mint. 18.00). As Yusuf said, “Bayyah is one of the scholars that have political experience as well” (

Zaytuna College 2017, mint. 1.00). He was among the founders of the International Union of Muslim Scholars. He served as vice president of the IUMS and the European Council for Fatwa and Research. The council was established to provide guidance to Muslims in Europe by transmitting religious opinions. He was also on a program at Al-Jazeera, a Qatar-funded TV channel, about sacred law and life (AlJazeera Channel

قناة الجزيرة 2009).

8 After the denouncement of the IUMS, which condemned the coup and the brutal repression of the Muslim Brotherhood, bin Bayyah wrote a letter resigning from his position in 2013. It was after this resignation that his alliance with the UAE intensified, and he became the de facto leading religious figure in the UAE.

Since then, bin Bayyah has become a religious legitimizer of the UAE. In this sense, his legal opinions and actions comply with the objectivities of the UAE’s foreign policy. Bin Bayyah’s approach presents a peaceful environment, which creates a new image for the UAE. Many initiatives (including the Emirates Fatwa Council and Promoting Peace in Muslim Societies) and principles have been launched and implemented by bin Bayyah in line with the UAE’s Islamic vision supporting inter-religious thoughts and the status quo.

3.2.1. Inter-Religious Discourse

Bin Bayyah suggests that there are at least two dimensions involved in the consideration and evaluation of non-Muslims. The first one is relevant to the humanitarian perspective of Islam: All humans were created from Adam, and Adam was created from clay. Therefore, no one is superior to anyone else. The second dimension is relevant to the religious perspective: Islam, as a religion, respects all other religions. Bin Bayyah noted that it is a fact that no temples were destroyed during the time of the Prophet. Therefore, he said, “Islam’s relations with the other religions are integration and appreciation”. War is only for responding to oppressive and aggressive actors (

عبدالله بن الشيخ المحفوظ بن بيه 2016a).

9Bin Bayyah describes the UAE as a country of tolerance, which means acceptance of others and leniency, which means generosity (

Quran Vid 2018b, mint. 1.00). Bin Bayyah believes that both values are manifested in the UAE. The UAE hosts the Forum for Promoting Peace in Muslim Societies, which brings together people from different backgrounds, cultures, ethnicities, and religions. The Forum aims to bring all humankind together with all its diversities so that the differences will be a source of enrichment and natural beauty. Humans cannot bear the varieties that Allah has put in the universe, but want to remove differences by force. By emphasizing the value of peace in Islam, he considers “people who fight each other as children”. According to Yusuf, the Abrahamic faiths therefore tell believers about the idea of living together, show the true path by preventing them from fighting each other and waging war, and clarify the ways to achieve these goals through dialogue.

Bin Bayyah considers that the initiative of the Forum resembles

Hilf al-Fudul, which represents a special symbolism. In fact, this

Hilf was established in the past and was based on values, virtues, and solidarity in living, which was quite different from the contemporary tribal or religious alliances. Therefore, people were against injustice and helped in each other’s lives. Bin Bayyah refers to a Prophetic narration which states: “If there was an alliance in the

Jahiliyyah [days of ignorance], Islam has only strengthened it”. He thinks that the Prophet only proves the alliance regarding the no violence policy and claims that these teachings need to be applied in the current environment. The Forum, therefore, is a kind of alliance based on tolerance and peace, which is quite similar to the alliance. It calls for peace and solidarity within the Abrahamic family and the family of humankind to face the dangers surrounding us. He says, “from the depths of our religions, we draw evidence calling for peace. We must search, each in his traditions, his religion, to present the right version that calls for peace. We must reject fanaticism and war because nothing good comes from it. Today, there is no winning side in the war. All belligerents are losers. We call the press to cover their activities” (

Quran Vid 2018b;

عبدالله بن الشيخ المحفوظ بن بيه 2022).

10 Bin Bayyah has been calling for and focusing on peace before justice (

Parker 2018). He quotes Kant’s idea of perpetual peace and states that without justice, there can be no peace (

Hamza Yusuf 2014, mint. 15.00). Bin Bayyah argues that it is more important to have peace, so that people can address the problem of justice within the context of peace: “We need a dialogue of civilizations or societal dialogue so that the alternatives to war can be examined. Religion is energy that enables us to produce both destructive and constructive things. Our approach is to use all these means to promote peace” (

Hamza Yusuf 2014, mint. 20).

Bin Bayyah has served as a representative at many international forums, including the Council on Foreign Relations and the United Nations General Assembly (

Council on Foreign Relations 2015). Bin Bayyah also thanked Obama for his call about acting out of goodness for everyone’s sake. He says, “We must cooperate because the ship is sinking, and the house is burning. Today we are trying to save the world ship”. As mentioned in the Prophetic narration, “We are trying to put off the fire that has burned in a house of earth. We are rescuers. We must work together. Works must be complementary in accordance with our levels and duties. The duty of the religious people is to fight and put off the fire in the hearts of people. To do that, we must teach people. The problem of peace has priority over rights”.

In this sense, bin Bayyah disagrees with Kant. Kant promoted the idea that justice comes first. Bin Bayyah supports Hobbes, who put peace first. This does not diminish the importance of justice, but recognizes that peace provides opportunities for restoring rights in the correct way that war can never provide. Bin Bayyah also quotes Nietzsche, who believed that when civilizations fall ill, philosophers are their physicians. Bin Bayyah says, “Our civilizations are currently suffering from sickness. We are prescribing a treatment. We are trying to treat civilization. The job of Islamic scholars is to protect the holiness of the holy texts and to make sure that they are accurately interpreted and translated into correct actions. The job is also to make sure that the holy texts are protected against tyranny aren’t extremism”.

Bin Bayyah says, “We have been trying to correct the Islamic memory and the historical memory by establishing the correct path of the Prophet”. From the UNGA, bin Bayyah assigned the responsibility of protecting peace and security to all governments, and especially the superpowers, which have a special duty to correct and address historical injustices. The initiative was launched in 2012 with a symposium (

Hamza Yusuf 2015,

2017b,

2017c). The second initiative was organized in Tunisia. The same topic was discussed at a conference held in Morocco. These steps culminated in a declaration of the rights and responsibilities of citizens and religious minorities that was derived from the constitution of Madinah concerning relationships among Muslims, Jews, and others. Bin Bayyah says, “We make sure that Islam does not call for the extermination of all minorities. They would continue to work with Islamic scholars with the blessing of the UAE” (Forum for Promoting Peace

منتدى تعزيز السلم 2015b).

11 President Obama welcomed the Forum during his UNGA speech by stating, “Look at the new forum of promoting peace among Muslim societies. Sheikh bin Bayyah described its purpose. We must declare war on war. So, the outcome will be peace upon peace” (

عبدالله بن الشيخ المحفوظ بن بيه 2014).

12 Bin Bayyah was then introduced as a voice of moderate Islam on CNN. In his interview with CNN, he said, “Islam does not call to war. Islam invites peace”. He denied the accusation that a fatwa had been issued to kill US soldiers by stating: “I call to the life, not to the death” (

عبدالله بن الشيخ المحفوظ بن بيه 2014).

13When bin Bayyah attended the G20 Interfaith Forum in 2020, he said, “We participate in this forum to raise awareness to achieve of goals of coexistence and peace. I share this vision with you. I work to establish a world in which principles, values, and space of religion, partnership, coexistence will be seen not competitions”. Since he is the head of the UAE-based Promoting Peace in Muslim Societies, his presence at such events can be considered as part of a PR campaign for the UAE as well. Bin Bayyah stated: “We want religions as a part of the solution, not the problem. Religions are a great power that can be a bridge for communication between people”.

Bin Bayyah said that “without tolerance of others, wars will occur” (

Hamza Yusuf 2017d, mint. 11.00). He quoted a verse from the Qur’an: “O humanity! Indeed, we created you from a male and a female and made you into peoples and tribes so that you may ˹get to’ know one another” (Surah al-Hujurat/13). By emphasizing mutual values, he used the verse to increase engagement with others. Tolerance, according to him, means that people accept and bear diversity. However, acknowledging and recognizing others is something higher than the concept of tolerance. He gathered a group of scholars to solve the problems that occurred after the Arab Spring. He referred to convenience in the time of the Prophet which established equality among the believers of the different religions in the city of Madinah. The Charter of Madinah encouraged him to bring Muslims, Jews, Christians, Yezidis, and Hindus together. In this sense, bin Bayyah co-organized a meeting in Marrakesh that published a declaration emphasizing the importance of tolerance (

Garba 2018;

Marrakesh Declaration 2016).

Regarding the concept of coexistence, bin Bayyah became friends with Zionists and a legitimizer of UAE–Israel normalization (

Rosenberg 2019). A movie titled “The Sultan and the Saint”, funded by the UAE, delivers the same message. In an interview, bin Bayyah and Yusuf endorsed the movie’s message of supporting interfaith dialogue by using Qur’anic verses (

iLM STREAM 2018).

Moreover, bin Bayyah said, “Dialogue is a religious duty and a humanitarian necessity, not a seasonal matter. The dialogue has a religious origin. It is said in the Holy Qur’an, ‘Invite to your Lord’s Way with wisdom and good advice, and debate with them in the most dignified manner.’ (Surah an-Nahl/125); ‘Do not argue with the People of the Book unless gracefully, except with those of them who act wrongfully’ (Surath Ankebut/46)” (

عبدالله بن الشيخ المحفوظ بن بيه 2016c).

14 When bin Bayyah’s attempt at legitimizing dialogue with Christians and Jews sparked great discussion, he said that dialogue is in order even with the oppressive (Social Media

سوشيل ميديا 2021).

15Attending the Washington Hebrew Congregation in 2018, bin Bayyah said that the provenance of the event was the idea of an alliance of virtue amongst the Abrahamic family (

Washington Hebrew Congregation 2018, mint. 55.00). There should always be a voice calling for peace, even if, at times, it might sound like a weak voice. The voice of peace is stronger than the voice of war. Since people are exhausted from wars, the Abrahamic family can once again bring people together and bring the hope of peace back to a conflicted world. Bin Bayyah’s first target is to remove the legitimacy of religion from the advocates of hatred and war. This can be accomplished not just with people’s words, but also with actions and relations. Showing love, respecting beliefs, and having sincere friendships and integrity are among the main principles and understandings according to bin Bayyah. With these priorities, bin Bayyah eased the engagement with non-Muslims and committed to end the war. According to him, while dialogue is a way to conduct peace, speech is an instrument for seeking peace, referring to the event when Allah spoke with Moses.

3.2.2. Serving the Status Quo and His Stance on the Arab Spring

During the initial stages of the Arab Spring, bin Bayyah partly supported the demonstrations. However, soon after, he shifted his stance on revolution and became one of the counter-revolutionary actors mainly allied with the UAE. During the first phase of the Arab Spring, he was a guest on an Egyptian TV channel. When he was asked about his view on riots against the ruler, he said that the issue is complicated (

عبدالله بن الشيخ المحفوظ بن بيه 2011).

16 He emphasized allegiance and jurisprudence as two vital aspects that affect the revolution. The first one, allegiance, is a contract that binds both sides, the ruler and the ruled (

E. E. Yakar and S. Yakar 2021, pp. 24–28). This contract prevents society from going against the ruler. On the other hand, society can only go against the ruler by invitation or by being advised, such as with a call by a council for restoring justice. The second one, jurisprudence, focuses on the consequences of actions (فقه اعتبار مآلات الأفعال—

fiqh “tibār m”ālāt al“a”āl).

Bin Bayyah has said that he was not antirevolutionist, but he changed his position regarding the results of revolutions (the second point he mentioned). The result of the current attempts, according to him, is not among the desired expectations of revolutions. Rather, he considers revolution to be like a bulldozer crashing and destroying whatever was there before it. He argued that people need engineers to build new systems rather than revolutions when he criticized the Arab revolution due to the lack of intellectual leadership or originality. He argued that wars do not implement justice but increase the level of killing, which is an undesirable outcome. He therefore believes that tranquillity is one of the means to reach peace, and that even jihad is not the target, but instead a means to reach or settle justice (

خليجية 2014, mint. 1.00–11.00).

17 3.2.3. Pro-Israeli Stance

When asked about the frustration of Palestine and Jerusalem, bin Bayyah said: “I don’t think this turmoil will liberate Palestine. A Muslim must be rational and must look for positive results. I think that unrest and indiscriminately killing people will not liberate Palestine. The British Parliament voted to recognize Palestine, which is good. Why don’t we go in this direction? And argue for the Palestinian cause in Britain. Rather than indiscriminate actions that do more harm than good? This is from experience; they must look around. No matter how disappointed an individual is, they must not commit suicide” (

Imams Online 2015).

Bin Bayyah approved the normalization attempts with Israel, describing the deal as holy (

5Pillars 2020). Emphasizing the aspects of promoting peace and stability across the world, bin Bayyah said that normalization prevents Israel from occupying Palestinian lands. Moreover, he stated that international relations and treaties are among the initiatives that fall within the policy-making purview of rulers. This means that bin Bayyah allows rulers the freedom to choose whatever they want to employ or implement. To provide Islamic legitimization to the normalization of a treaty, bin Bayyah uses the Qur’anic verses and Prophetic narrations. He says the Treaty of Hudaybiyah is a great example of how Muslims can agree with Jews. Specifically, he uses this Qur’anic verse (61st verse of The Spoils of War): “If they should incline to peace, then incline to it too”. On the other hand, bin Bayyah’s statements include Islamic references, such as public interest (

maslaha) and Islamic law (

sharī‘a). The Council’s fatwa stated that the normalization of the treaty protects the interests of the UAE and abides by Islamic law. Bin Bayyah also confirmed that signing a deal is within the responsibility of the ruler. In other words, he says that signing an agreement or waging a war is under the authority of the ruler (

عبدالله بن الشيخ المحفوظ بن بيه 2016b).

18 Therefore, the UAE has earned religious legitimacy for the normalization deal.

Bin Bayyah’s attempt to legitimize normalization or formalization has sparked great interest among Muslim scholars, including members of the Forum. For example, the American Muslim activist Aisha al-Adawiya, founder of the human rights group Women in Islam, did not agree with the statement and resigned from the Forum (

Farooq 2020). On the other hand, bin Bayyah’s endorsement regarding normalization intensified the divergence among Muslim scholars, including Sheikh Mohammad al-Hassan Dadow (محمد الحسن الددو Cheikh Mohamed El Hassan Ould Dedew Channel 2020).

19 Therefore, the UAE tried to gain the support of influential Muslim scholars for the normalization attempts (

Al-Anani 2020;

Dorsey 2020). Upon finding supportive scholars, they were hired to serve the regime’s interest (

UAE Attempt to Get Muslim Scholars to Endorse Israel Deal Falls Flat 2020).

4. Institutionalization of UAE’s Version of Islam

The UAE has experienced a lack of ideology to unite its citizens since its foundation. To overcome this obstacle, the elites in the country have allied themselves with different ideologies, such as Pan-Arabism and Islamism. For example, the UAE was a prominent supporter of oil boycotts to the West due to the Palestinian issue (

Joffe 2004). Zayed’s stand on the Palestinian issue has always been to show support for the Arab cause. Another example is the deep influence of the Muslim Brotherhood on the UAE until the beginning of the 2000s. The Muslim Brotherhood was welcomed in the UAE both to balance Arabists in the country and to give a level of legitimacy to the ruler (

Freer 2015).

During the 2000s, the UAE has changed its stance from borrowing legitimacy from regional ideologies to creating its own version of Islam and thus establishing legitimacy in domestic affairs as well as international relations. This was related to the fact that several hijackers on 9/11 were from the UAE. Because of this, the UAE was afraid that it would be held responsible for the attack. Since then, the UAE has co-operated with the popular US concept of war and terror and fighting extremism, and has become a prominent supporter of “moderate Islam” (

Al Sayegh 2004). The events of 9/11 and subsequent affairs in the world, such as the fight against terrorism and antiextremism discourse, give more legitimacy to the UAE in its aggressive way of creating a version of Islam, which claims to be antiextremist, moderate, and based on interfaith dialogue.

After the Arab Spring, the UAE increased its initiation by institutionalizing its version of Islam. Several figures, including Yusuf and bin Bayyah, have played prominent roles in these institutions and share similar messages revolving around political quietism, obedience to the ruler, and interfaith dialogue, with a special focus on Abrahamic religions.

4.1. Forum for Promoting Peace in Muslim Societies

The Forum for Promoting Peace in Muslim Societies is an organization that was established in 2014 to increase the UAE’s influence on Islamic thoughts globally. Feeling the need to compete with the Wahhabi thoughts of Saudi Arabia and Qatar’s support of the Muslim Brotherhood, the UAE initiated a “moderate” Islam campaign.

[The Forum] aims to promote peace in Muslim societies, to strengthen efforts to unify Islamic societies and douse the fire spread by extremist ideologies that are contrary to human values and principles of Islam. The Muslim nation’s scholars and wise men must take their full responsibilities at this historical juncture and save the nation through careful planning and perseverance. They now have the opportunity to make increased efforts for the promotion of peace in this region through moderate Islamic means that harmonise understanding of the text and jurisprudence instead of its distorted version.

The Forum was sponsored by Abu Dhabi under the patronage of Abdullah bin Zayed Al-Nahyan and chaired by bin Bayyah (Forum for Promoting Peace

منتدى تعزيز السلم 2018).

20 Bin Bayyah, as a prominent figure among Muslim and non-Muslim audiences, has helped the UAE to enhance its version of Islam, competing with those who were once his allies in Qatar (he was a vice president of the International Union of Muslim Scholars, funded in Qatar by scholars close to Salman al-Ouda and Yusuf al-Qaradawi’s leadership).

Bin Bayyah’s diversion with al-Ouda and al-Qaradawi corresponds to the height of the Arab Spring, when the two small Gulf states situated each other on opposite poles. Since then, bin Bayyah has emphasized the antirevolution stance with Islamic justifications and used the Forum as a way to criticize and delegitimize the opposite pole. Bin Bayyah clearly stated in an interview with Al Jazeera that he is not amongst the supporters of the revolution (

أخلاق الثورة 2011).

21In this regard, during his alignment with al-Qaradawi in the International Union of Muslim Scholars, bin Bayyah was a part of a team sent to Yemen aimed at ending the war by bringing belligerent parties together. However, since bin Bayyah intensified his engagement with the UAE, he hesitated to announce his stance on the war in Yemen (

علماء دين يتوسطون لانهاء الحرب بين اليمن والحوثيين 2010).

22 Bin Bayyah’s student Yusuf had the same stance on Yemen. In an interview with Sky News Arabic, a pro-UAE media outlet, Yusuf highlighted that the war in Yemen was a humanitarian disaster and must be ended. While Yusuf insisted on calling an end to the war in Yemen, he avoided even touching upon the UAE’s role in it (24

فرانس/FRANCE 24 Arabic 2019, mint. 30.00–33.00).

23 Bin Bayyah and Yusuf’s silence (or emphasis on humanitarian aid by neglecting the UAE’s role in the conflict) over the UAE’s role in the conflict in Yemen was highly criticized (‘Involvement of High Profile Muslim Scholars in the 2018 UAE Peace Forum Provokes Accusations of Religious Legitimation in Light of the Yemen War’—

Euro-Islam 2019).

The Forum’s funding and headquarters are not the only links to the UAE. The supported notion of the Forum is that the UAE aims to brand itself as the representative of that version of Islam. At the 2018 Forum, Yusuf, an individual close to the UAE, made a speech regarding the interfaith dialogue, and particularly about Abrahamic religions (

Islam Rewards 2018). In another interview, Yusuf quoted a verse from the Qur’an (the Baqara/208) and noted the importance of peaceful relations with Christians and Jews since they are the recipients of the books as well (فرانس 24/FRANCE 24 Arabic 2019, mint. 24.00–26.00).

24 Yusuf acknowledged bin Bayyah’s efforts to act in line with the verse and his desire to create peace among nations (فرانس 24/FRANCE 24 Arabic 2019, mint. 24.00).

25In addition to the Forum, bin Bayyah (along with the al-Nahyan family) established several organizations and institutions parallel to Qatar and Qaradawi’s institutions. Jurisprudence of Peace (

fiqh al-silm) was initiated to counter Qaradawi’s Jurisprudence of Revolution (

Warren 2021).

The Forum serves as a place where the UAE has an opportunity to conduct PR campaigns. For example, during bin Bayyah’s visit to London, where he met the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, he touted the UAE as a promoter of science and moderatism, which will hinder the spread of extremism. On bin Bayyah’s website, the meeting was described as follows:

He also introduced the scientific projects that were organised by the Forum, with the UAE’s generous support and patronage, to apply its vision, most notably the Peace Encyclopaedia, which will discuss concepts that were originally intended to promote peace, but were used by those with extremist ideologies to justify their actions.

The Encyclopaedia of Peace in Islam was established on 30 April 2015 during the second session of the Forum. The encyclopedia aims to collect “the jurisprudence, maxims, means, and values of peace according to the method of the Forum in dealing with religious texts. The Forum has launched the project of encyclopaedia in response to the challenges that threaten Muslim societies and the international community” (

Peace Encyclopedia 2019).

The Forum (co)organized many events all around the world. For example, the Marrakesh Declaration was signed on 27 January 2016 at the end of a conference hosted by the Ministry of Endowments and Islamic Affairs of the Kingdom of Morocco and co-organized by the Forum (

Marrakesh Declaration 2016). The Declaration’s discourse is very similar to the UAE’s promoted version of Islam in its overgeneralization of violence in the Islamic world and its support of moderation, tolerance, and interfaith dialogue as the solution against it. The Declaration refers to the importance of rulers and governments in guaranteeing stability of the land, an idea that was supported by the UAE’s Islamic network during the Arab Spring. The declaration states:

WHEREAS, this situation has also weakened the authority of legitimate governments and enabled criminal groups to issue edicts attributed to Islam, but which, in fact, alarmingly distort its fundamental principles and goals in ways that have seriously harmed the population as a whole.

There is further reference to the Charter of Medina as guaranteeing every citizen’s rights during the time of the Prophet. The UAE, domestically, promotes the idea of tolerance among religious groups and sets itself as an example to the Muslim world. The declaration states:

Call upon politicians and decision-makers to take the political and legal steps necessary to establish a constitutional, contractual relationship among its citizens, and to support all formulations and initiatives that aim to fortify relations and understanding among the various religious groups in the Muslim World; call upon the educated, artistic, and creative members of our societies, as well as organisations of civil society, to establish a broad movement for the just treatment of religious minorities in Muslim countries and to raise awareness as to their rights, and to work together to ensure the success of these efforts.

The declaration, as the UAE did after the 9/11, asks “Muslim educational institutions and authorities to conduct a courageous review of educational curricula that addresses honestly and effectively any material that instigates aggression and extremism, leads to war and chaos, and results in the destruction of our shared societies” (

Marrakesh Declaration 2016).

4.2. Emirates Fatwa Council

The Emirates Fatwa Council is an example of what the UAE has created to have full control over religious issues. The Council operates as a governmental body of the UAE. It was established in 2018 and is responsible for issuing Islamic opinions, or fatwas. Even though the Council was created to empower the UAE in Islamic affairs, it sometimes sides with fatwas issued by the Saudi Council of Senior Scholars. For example, when the Saudi Council denounced the MB as a terrorist organization, the Emirati Council followed them (

UAE Fatwa Council Labels Muslim Brotherhood as Terrorist Group 2020).

The Council was established as a part of a religious ecosystem that shares many common themes, ideologies, and figures with other institutions. The chair of the Council, for example, is bin Bayyah, who has also been involved in different UAE initiatives, such as the Forum for Promoting Peace in Muslim Societies, and is known for his close relations with Emirati elites. Another key part of the hierarchical system is the well-known American scholar, Yusuf, who is famous for his legitimization of rulers, specifically of the UAE, by his praise of and involvement in the UAE’s initiatives.

Yusuf was asked about his opinion of the Emirates Fatwa Council in an interview with Sky News Arabia, an Emirati-based news channel. After explaining the importance of the state (and political power) to religion, Yusuf explained the significance of the Council by citing bin Bayyah’s three types of

fatwa. The first type,

fatwa Elif, is about common questions that many scholars can provide answer to regarding pilgrimage, worship, or fasting issues. The second type,

fatwa B, is about social transactions (

muāmalāt), for which experts can provide solutions regarding marriage, divorce, or inheritance issues. When explaining

fatwa B, Yusuf used as an example an American woman who converted to Islam. When she consulted with scholars regarding the status of her non-Muslim husband, most of them considered this marriage to be invalid and illegal. When this issue came to Yusuf, he referred to bin Bayyah, who issued a fatwa with weak reasoning. After Yusuf issued a fatwa permitting the marriage with the non-Muslim husband, the marriage continued. Regarding the wife’s happiness, the husband converted to Islam six months later. Yusuf considered the deep knowledge of bin Bayyah, by allowing the woman to stay in a marriage with weak evidence from a religious perspective, as something important and reasonable for the establishment of the Council. The third type,

fatwa Cim, is about political affairs, such as announcing

jihad. This type of fatwa is reserved for the leader (

سكاي نيوز عربية 2018, mint. 14.00–17.00).

26The fatwas of the Council have a direct link to the UAE’s policy towards divergent religious groups. By creating this Council, the UAE can compete with its neighbors in terms of religious institutions, such as the Saudi Council of Senior Scholars (

E. E. Yakar 2020,

2022). The Council is devoted to providing Islamic legitimization of the UAE’s policies. In this sense, quoting many verses from the Qur’an and the narrations of Prophet, the Council indicates that pledging to any ruler other than the current ruler is illegal and invalid (

ḥaram). Obedience to the ruler is therefore widely supported by Yusuf as well.

This organization is important, as it aims to be the sole entity responsible for the UAE’s religious affairs and ending the country’s reliance on outside institutions, including Saudi Arabia. When the UAE normalized its relations with Israel, the Emirates Fatwa Council considered this recognition permissible in terms of Islamic law, pointing out the public interest. The fatwas, which were led by bin Bayyah, emphasize several fundamental ideas which are mainly in line with the view of UAE-supported figures and institutions, such as acknowledging the sole authority of the ruler, encouraging peace and harmony, and preventing the negative effects of war and pandemics (

Winter and Guzansky 2020).

The Emirates Fatwa Council ultimately aims to become the sole religious authority within the UAE. For example, during the COVID-19 outbreak, the Council issued a fatwa permitting the closing of mosques for congregational worship. It issued another fatwa stating that the vaccine is permissible even if it contains non-permissible substances (

Myrzabekova 2021).

5. Conclusions

Small states have been looking for ways to overcome their weakness in the anarchic international system (

Miller and Verhoeven 2020). Founded in 1971 between ideologically and militarily powerful states, the UAE has struggled to enhance its material power. Initially, it secured a place within the Western security system (mainly with the US and UK) and bandwagoned with a powerful neighbor (Saudi Arabia). While it secured its hard power by allying with the West and bandwagoning with Saudi Arabia, it invested in its soft power to enhance its capabilities. Over time, however, the UAE increased its material stance while regional powers decreased their power (mainly Iran, Iraq, and Egypt).

The mass protests that have spread all over the Arab world since 2010 are among the milestones that show the UAE’s enhanced capacity. As hostile powers have fallen one after another, the UAE (along with other Gulf states) has emerged as the new regional power. Contrary to its traditional foreign policy, which was based on foreign aid, diplomatic initiatives, and foreign direct investments, the UAE conducted many hard power initiatives in Bahrain, Libya, and Yemen.

Although the UAE has commenced hard power initiatives, it has not abandoned soft power. The country aims to establish a version of Islam that will help its campaigns at the domestic, regional, and global levels. This version of Islam stresses the importance of rulership and leadership while discouraging the idea of revolt and disobedience against the ruler. The UAE established a network to promote its Islamic version with many individuals and institutions. Yusuf and bin Bayyah have had significant roles and responsibilities in initiatives such as the Forum for Promoting Peace in Muslim Societies and the Emirates Fatwa Council. Yusuf frequently emphasizes the illegitimacy of political Islam and quotes Islamic texts to preserve the stability of the current regime. Moreover, he and bin Bayyah, his role model, disagree with resistance against the rulers. They legitimized the UAE’s foreign policies, including the most controversial ones, such as UAE–Israel normalization, and backed the normalization deal by saying that peace comes before justice. These individuals and organizations also use history as a reference to promote the tolerant aspect of religion. In this sense, they have expressed that the Alliance of Virtue is based on the same mentality with which Hilf al-Fudul was constructed. Therefore, the UAE has benefitted from state-controlled and diverted Islam.

It can be stated that the UAE has several goals in supporting these scholars and organizations. While it aims to establish its own institutions to rival its neighbors Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Iran, it is also legitimizing its hard power initiatives in the region by labeling all others as extremists and radicals. The labels echo the post-9/11 Western discourse promoted by the US and other Western allies. Since these states also legitimized their foreign and domestic abuse with interpretations of religious texts (the invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan and anti-Muslim laws, respectively), the UAE’s initiatives were not considered alien. It is noteworthy that religion is being used to present the UAE as a model. By launching a network consisting of religious individuals and institutions, the UAE can utilize religion as a soft power. Rhetoric and actions fueled by Emirati agents activated the UAE as a model and representative of tolerance. These institutions and organizations, therefore, have an organic link with the official Emirati understanding of religion and politics, which promotes a moderate Islam.