1. Introduction

The passage of the International Religious Freedom Act (IRFA) in 1998 marked the culmination of efforts by Christian advocacy groups and prominent American evangelicals to address what was perceived as growing persecution of Christians worldwide following the end of the Cold War. Although beginning with this relatively narrow agenda, key proponents sought to expand the international religious freedom (IRF) agenda to include positive affirmation and promotion of religious freedom worldwide for all faiths, rooted in the “first freedom” in the American canon (

Farr 2008;

Hertzke 2008;

Marsden 2020). This broadened appeal was instrumental in drawing support, at least in the short term, across partisan and ecumenical divides, setting IRF as a core objective of American foreign policy.

These efforts have been embodied in the establishment of the Office for International Religious Freedom (OIRF) in the US State Department, the creation of the position of Ambassador at Large for International Religious Freedom under the American Secretary of State, and the formation of the independent United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF), staffed equally by representatives from both parties and both houses of Congress. The USCIRF has also sought to represent a wide range of religions including Hinduism, Islam, and Judaism, as well as evangelical and mainline Protestants and Catholics as its commissioners and ambassadors at large. The USCIRF in turn produces annual reports on IRF, designating “countries of particular concern” (CPCs) and proposing policy actions. These reports have been instrumental in raising awareness regarding religious repression worldwide, ostensibly contributing to American efforts to support South Sudanese independence, sanction Iranian officials for human rights abuses, encourage Russia to pass hate crime legislation, and demand the release of prisoners of conscience in Pakistan and Saudi Arabia (

Leo and Argue 2012;

Marsden 2020).

The extent to which these efforts have produced meaningful progress in broader terms, however, remains an open question. As a soft power instrument, IRF promotion relies not only on convincing targets of the “righteousness” of religious freedom but that the United States indeed prioritizes IRF as a core value in its diplomatic relations with other states. Yet, in the past two decades, IRF has often been devalued, ignored, or subsumed under other more “pressing” policy objectives under successive administrations from Clinton to Bush to Obama. Efforts made under the Obama administration in particular to more positively engage with the Muslim world have been complimented as explicitly expanding beyond IRFA’s initial evangelical-supported agenda while also criticized as deeply ineffectual by avoiding direct critique of some of the world’s harshest violators of religious freedom (

Birdsall 2012;

Farr and Saunders 2009;

Finke and Mataic 2019). The late Trump administration’s approach of prioritizing religious freedom “first in the hierarchy of human rights, while relegating others, especially equality for females and sexual minorities, to a lesser position” has, in turn, done little to advance the cause of IRF worldwide (

Haynes 2020). While the current Biden administration has made efforts to redress Trump’s religiously discriminatory policies at home and abroad and rejected its religious freedom first approach to human rights (

Siddiqi et al. 2022), it has also been criticized—as with its predecessors—for failing to pursue IRF advocacy in countries with whom the US has pressing security interests (

Basu 2021).

These developments raise a larger question: to what extent does foreign approval of the United States, a key prerequisite of soft power influence, actually contribute to America’s ability to persuade its partners or adversaries of the moral imperative of religious freedom? Indeed, if the United States tends to devalue IRF promotion in instances where policymakers most believe they need to cultivate American influence and express disapproval of religious repression, primarily regarding states with which its relations are the poorest, a greater magnitude of (potential) American soft power is likely to correlate with less rather than more religious freedom. It is precisely this puzzle this article seeks to explore.

In the sections that follow, we survey the literature, theorizing the benefits and challenges of IRF promotion. We then design and test measures examining the extent to which popular approval for the United States has correlated with decreases in religious freedom observed worldwide since the IRFA’s passage in 1998. Altogether, our findings are depressing ones for IRF advocates, revealing strong correlations between growing restrictions on religious freedom and increasing popular approval for the United States worldwide. We further break down our sample between states with whom America should enjoy the least a priori soft power influence, namely non-democracies, versus where they should have the greatest influence: democracies. Here, we see that although popular approval for the United States in non-democracies does not meaningfully correlate with restrictions on religious minorities, growing support for America is strongly and significantly correlated with the increasing magnitude of such restrictions among democracies. We close by discussing the significance of these findings for IRF advocates and soft power influence in general.

2. Challenges in Promoting International Religious Freedom

International religious freedom (IRF) is clearly in trouble. Nearly every study that examines global trends shows a decrease in IRF, though in most cases they technically measure increases in violations of religious freedoms (

Ettensperger and Schleutker 2022;

Fox 2015,

2016,

2019,

2020,

2021;

Fox and Topor 2021;

Finke and Mataic 2019;

Grim and Finke 2011;

Majumdar and Villa 2021;

Marshall 2009;

Peretz and Fox 2021;

Pew Research Center 2019). This is important because studies show religious freedom has many benefits. For example, Anthony

Gill (

2008,

2013;

Gill and Owen 2017) argues that IRF promotes economic prosperity by facilitating an open society where people of different religious groups can engage in joint economic activities more freely. It also encourages proliferation of religious institutions, which themselves can contribute to economic development.

Grim et al. (

2014) similarly argue that freedom in general is good for the economy, as religious freedom reduces corruption and increases human and social development. Nilay

Saiya (

2019,

2021;

Saiya and Manchanda 2020;

Henne et al. 2020) argues that a lack of religious freedom encourages religious extremists among the majority to engage in violence against religious minorities. In contrast, religious freedom empowers moderates and reduces the influence of religious extremism (

Khan 2013;

Philpott 2013).

Grim and Finke (

2011, pp. 2–3) similarly argue that the higher the degree to which governments and societies ensure religious freedoms for all, the less violent religious persecution and conflict along religious lines there will be (also Inboden 2013, p. 173).

On a more basic level, religious freedom is a core freedom deeply connected to other freedoms, such as freedom of speech and assembly, yet distinct from them. As argued by

Finke (

2013, pp. 301–2):

Virtually all of the freedoms listed in the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights can offend or threaten a cultural majority, and, as a result, all require state support to ensure the freedom is protected. Religious freedoms are no exception. Like other freedoms, protecting religious freedoms can be both inconvenient and costly. Even when the state lacks explicit motives for restricting religious freedoms, the state often allows restrictions to arise because it lacks either the motive or the ability to protect such freedoms.

In fact, “when stripped to the core, religious freedoms can be viewed as an extension or even a duplication of other human rights” (

Finke and Mataic 2020, p. 128). Yet, despite similarities with other freedoms, “religion holds a distinctive relationship with the state and larger culture. While all human rights depend on political support and state protections, the nature of religion-state relationships poses unique challenges for protecting religious freedoms and carries increased risks if these freedoms are not protected” (

Finke and Mataic 2019, p. 687).

The original passage of the International Religious Freedom Act (IRFA) by the United States government in 1998 was inspired in large part to protect Christian minorities abroad (

Joustra 2018;

Marsden 2020), yet it was also motivated by an understanding of religious freedom’s many benefits. Even before the passage of the IRFA, religious freedom was an element of US foreign policy. For example,

Joustra (

2018, p. 13) argues that “religious liberty, on the one hand, was a first right, a fundamental piece of the package of liberal politics; on the other hand, it was a banner under which to oppose the Soviets, a moral high ground from which to ideologically shell the opposition during the Cold War” (also Hertzke 2008). In fact, the idea of containment was infused with religious purpose to defend the world’s God-given freedoms and rights; that is, religion was a critical element in shaping the worldview which helped the US win the Cold War (

Inboden 2008).

Bettiza (

2019) argues that after the end of the Cold War, three interrelated groups emerged and lobbied the US government to become increasingly active in IRF promotion (also Farr and Saunders 2009; Haynes 2008). The first was religious Christians, mostly evangelicals, who were concerned with the persecution of Christians around the world (

McAlister 2014). This group emerged in the context of the growing politicization of evangelicals, who had become increasingly engaged in international issues. The second was a group of many who saw IRF as a human rights issue. The third emerged particularly after the events of 11 September 2001, with lobbyists who saw religious freedom as a national security issue. Obviously, the latter were not part of the coalition which initially supported IRFA’s passage but became active in supporting its application. All of this compelled the US State Department to “build greater capacity in US foreign policy to understand the role of religion in world politics and, based on this understanding, to engage and mobilize religious actors and voices in pursuit of American values and interests globally” (

Bettiza 2019, p. 174).

The ideals of the 1998 IRFA and the increase in American institutional capacity to support it were certainly intended to increase US religious freedom promotion. The IRFA created the Ambassador-At-Large for Religious Freedom and a bureaucracy to support him or her. It also mandated yearly religious freedom reports on each country in the world (other than the US) to document, name, and shame violations of religious freedom. These efforts were clearly intended to employ US soft power to advocate for religious freedom. As

Haynes (

2008, p. 80) argued in his early evaluation of American IRF promotion, “Overall we have seen that the strength of religio-moral persuasion lies in its ability to co-opt people, not in the ability to coerce others into doing what you want them to do”. Indeed, consecutive administrations, diplomats, and other practitioners have acknowledged that IRF promotion efforts that seek to coerce rather than persuade are destined to fail (

Birdsall 2012;

Farr and Saunders 2009;

Leo and Argue 2012;

Thames 2014).

Yet, there has been a considerable critique that religious freedom has not been a priority for US foreign policy in practice. For example, Thomas F.

Farr (

2008), the first director of the US State Department’s IRF office, argues that “neither scholars of U.S. foreign policy nor its practitioners have taken religion very seriously”. While he believes that “U.S. diplomacy should move resolutely to make the defense and expansion of religious freedom a core component of U.S. foreign policy”, he observes that “neither Democratic nor Republican administrations, nor the U.S. State Department, have seen the IRF Act as a broad policy tool—indeed, as anything more than a narrow humanitarian measure unrelated to broader U.S. interests”.

Farr (

2008) is likely correct, as there are several obstacles both within the US government and outside of it for employing American soft power to advocate for IRF. The first is secularism.

Farr (

2008) himself notes that “the problem is rooted in the secularist habits of thought pervasive within the U.S. foreign policy community”. Many members of this community are “suspicious of religion’s role in public life, viewing religion as antithetical to human rights and too divisive to contribute to democratic stability”. They see religion as emotional and irrational, which makes it a poor basis for policy. They also generally have a poor understanding of the relationship between religion, politics, and society outside of the US.

Many others note this reluctance and inability of the US foreign policy community to engage with religion.

Inboden (

2013, pp. 162–63) argues that “most American national security policymakers do not personally possess strong religious commitments, especially in comparison to the much more religiously observant broader American public”. He also notes that the US tradition of separation of religion and state as well as the more general “post-Enlightenment tradition in the West of treating religion as an exclusively private and personal matter sometimes prevents policymakers from perceiving the public and corporate nature of religion in many non-Western societies (as well as portions of some Western societies)” (

Inboden 2013, p. 164). However, he is less pessimistic than Farr in arguing that “the religion allergy among policymakers has declined considerably in the past decade” (

Inboden 2013, p. 164).

Petito (

2020, p. 275) argues that the secularist perspective is limiting because it encourages policymakers to see religious actors “as either the victims or the perpetrators of FoRB [Freedom of Religion or Belief] violations—and not as partners in building long-term strategies to advance FoRB for all and foster pluralism, social cohesion and sustainable peace”. It also promotes a view that “the growing role of religion in international affairs is always a militant and violent-prone form of politics or that religion poses an inherent threat to international order and stability” (

Petito 2020, p. 276; also

Albright 2007;

Marsden 2020, p. 9).

Second, IRF competes with other US foreign policy goals and concerns. Many important US allies such as Saudi Arabia are among the world’s worst violators of religious freedom. While these countries are regularly named and shamed in the IRF reports, and US diplomats often raise pro forma IRF issues with them, experience shows that there are few US-imposed consequences for these violations of religious freedom. Some, such as

Rieffer-Flanagan (

2015, p. 45) explicitly argue that “the United States, despite its rhetoric about religious freedom pursued a policy of realism and often allowed national and strategic interests to trump the human right of religious liberty”. She notes that the IRF office has been given a limited budget and argues that the US State Department has “attempted to weaken the Office of International Religious Freedom and its director by making the director answer to other State Department officials and limiting the personnel in the office” (

Rieffer-Flanagan 2015, p. 47).

Rieffer-Flanagan (

2015, p. 48) reinforces the arguments that IRF is subordinated to other policies, confirming IRF promotion’s delimited role as a soft power foreign policy instrument when she notes that “rarely has the president used economic sanctions to promote religious freedom. In fact President G. W. Bush and President Obama have either used sanctions already in place to fulfill the IRFA requirement or they have waived the requirements altogether citing the importance of national interests”.

Gill (

2005,

2008) also argues that religious freedom has tended to be advanced only when politicians perceive them as serving their interests.

To counter IRF’s subordination to other foreign policy agendas, many have attempted to frame IRF as a national security issue. Proponents of this argument specifically claim that “where countries are not persecuting domestic minorities and are accepting of those of other beliefs or no beliefs, then […] they are more likely to live peaceably with other countries, and to increase the wellbeing of their own citizens” (

Marsden 2020, p. 5; also

Saiya 2019,

2021). Such securitization of IRF promotion may, however, undermine the very soft power instruments of persuasion that its proponents argue are necessary for its success.

Third, many secularists outside of the US government actively oppose the promotion of IRF in US foreign policy for ideological reasons beyond a lack of interest or knowledge of religion among the US foreign policy community.

Hurd (

2009,

2015), perhaps the most notable of this group, makes several interrelated arguments. Religious freedom is a Western construction, and promoting it constitutes an imposition of Western values on the non-West. For many religious believers, religious freedom therefore means the ability to impose their religion on others and restrict the freedoms of others. In this sense, the IRF office is understood as a proselytizing institution in disguise. She also argues that IRF only promotes freedom for particular kinds of religions, effectively repressing other (mostly non-Western) brands of religion. Power structures in the US accordingly shape American religious engagement in a manner that groups which the US disfavors will be more likely to be labeled as “extremists” and therefore more likely to be the targets of sanctions than those the US favors. Thus, in this respect, she overlaps with previous arguments that other interests dominate US foreign policy, but advocates of these policies tend to use IRF as a weapon against groups disfavored by the US. For these reasons, Hurd feels religious rights advocacy does more harm than good, applying this same critique to the American advancement of “human rights” broadly defined (see also

Mahmood 2015;

Sullivan et al. 2015).

There is some evidence that at least some policymakers outside the US see American IRF policy precisely as an imposition of US power.

Teater (

2020, p. 1), for example, posits that “that U.S. involvement in defense of religious freedom meets counter-narratives. These counter-narratives include the preservation of state sovereignty, the protection of national interest, and the privileging of religious tolerance over religious freedom”. She discusses this in the context of India’s explicit policy of limiting foreign influence on its religious organizations to protect India’s national security and cultural integrity.

Fox (

2020) also notes a widespread trend worldwide of states seeking to protect their national cultures from outside religious influences.

Marsden (

2020) similarly argues that secularists oppose religious freedom advocacy for a number of reasons. In principle, it desecularizes international politics, which they consider to be a harmful and particularistic trend. It universalizes Western interpretations of religion at the expense of non-Western interpretations. More explicitly, it has a Western Christian bias. It also presumably undermines separation of religion and state both domestically and internationally. However, Marsden notes that as IRF promotion is a soft power instrument, arguments of US imposition of its values on the world are exaggerated, and evidence that US IRF policy is biased toward Christians and neglects other religions is weak. Nonetheless, evangelical influences on IRF policy are undeniable, being particularly apparent under the Trump administration (

Haynes 2020).

Philpott (

2019) similarly argues, in a reply to the above secularist arguments, that while different cultures see religion and religious freedom differently, this does not mean these concepts have no core universal meaning. He also asks that if religious freedom were exclusively an exercise in power, why is it that it is so often trumped by other foreign policy goals? He points out “to the weak extent that the United States promotes religious freedom in its foreign policy, it does so on behalf of all religions, not just Christians” (

Philpott 2019, p. 43). He also observes that the IRFA is nearly always invoked on behalf of the powerless.

A fourth critique regards the general limitations of soft power. For example,

Glendon (

2018, p. 4) argues the following:

One of the most frustrating obstacles encountered by international religious freedom advocates is the difficulty of convincing governmental actors to pay attention to even the most shocking cases. Moreover, even when political leaders in one country are willing to speak out or act, the fact is that a single country acting alone will always be suspected, rightly or wrongly, of being motivated primarily by its own geopolitical concerns.

Marsden (

2020, p. 14) argues that with a few notable exceptions, such as the release of numerous prisoners of conscience, American IRF policy has had few tangible results.

Rieffer-Flanagan (

2015, p. 48) similarly argues that “while policymakers may point to numerous activities undertaken to promote religious freedom there is little clear evidence of the positive impact of these policies in the short term”. Both attribute this lack of influence to the limits of soft power.

Given all of the above, a few things are clear. First, American IRF policy is clearly an attempted exercise in soft power rather than hard power. Second, there are questions regarding the US’s commitment to this policy from both the political and administrative angles. Third, there are questions regarding the motivations for this policy which have implications for whether the US is actually following a policy of religious freedom promotion. Fourth, all of the above notwithstanding, there are questions as to whether any such policy can be truly effective. Given this, the question of whether US soft power does, in fact, have an influence on religious freedom in the world is highly pertinent.

3. Hypotheses: Evaluating IRF Promotion as a Soft Power Instrument

The central objective of this article, therefore, is to empirically evaluate the extent to which American efforts to advance IRF have been an effective instrument of American soft power. We generally hypothesize that if the United States’ IRF program has been a success, increasing levels of popular approval for the United States should be associated with decreasing levels of governmental discrimination against religious minorities (GRD) since 1998.

A particularly hard test of this hypothesis is if these patterns hold when focusing on less democratic countries. Although non-democracies should presumably be the countries American IRF initiatives are most likely to target, they are also the countries over which the United States probably has the least soft power influence, owing to more disparate cultural, political, and societal values (

Ciftci and Tezcür 2016;

Goddard and Nexon 2016;

Henne 2022;

Mattern 2001). That is to say, if we find that popular approval for the United States is associated with significantly diminishing levels of GRD, we can assert with great certainty that IRF initiatives are having a meaningful effect.

Alternatively, a rather easy test of our hypothesis is if greater popular approval for the United States in more democratic countries is associated with decreasing levels of GRD. Just as the United States is likely to enjoy relatively less cultural cache in non-democratic countries, it should have significantly greater soft power influence in democratic states, namely those with which it has the most culturally, politically, and socially in common (

Brannagan and Giulianotti 2018;

Sheafer et al. 2014;

Thames 2014). Given the prevalent criticism (cited above) that IRF initiatives are having little to no influence on receiving states’ commitments to religious freedom, a failure to find a meaningful effect in the context of democratic states should be particularly damning.

We formalize these hypotheses as follows:

Hypotheses 1 (H1). Higher levels of popular approval for the United States should be associated with decreasing levels of GRD since 1998.

Hypotheses 2 (H2) (Hard Test). Higher levels of popular approval for the United States in non-democracies should be associated with decreasing levels of GRD since 1998.

Hypotheses 3 (H3) (Easy Test). Higher levels of popular approval for the United States in democracies should be associated with decreasing levels of GRD since 1998.

4. Research Design

We evaluate these hypotheses by quantitatively examining the correlation between popular approval for the United States in 148 countries surveyed by various polling agencies between 2002 and 2014 and country-level changes in governmental religious discrimination (GRD) for each year since 1998, the year in which Congress passed the International Religious Freedom Act (IRFA). Our dependent variable is derived from aggregate calculations of annual state-level discrimination against religious minorities, collected by the Religion and State Project, round 3 (RAS3), for all countries with a population of at least 250,000 from 1990 to 2014 (

Fox 2015). The GRD variable is an additive index of 36 distinct forms of discrimination at four levels of increasing severity from absence to severe discrimination, with an observed maximum of 80. Our measure for change in GRD is an annual calculation of the difference between each country’s score in 1998 and each surveyed year with an observed range of −36 to +34 on the intuition that if America’s religious freedom promotion agenda is successful, higher levels of American soft power should be associated with decreasing GRD since IRFA’s adoption.

Our primary independent variables are derived from country-level popular approval for the United States based upon polling data by the Gallup World Poll, Pew Research Center, and the BBC/GlobeScan, as well as a combined measure drawn from all three sources. In turn, these data were originally compiled by

Rose (

2019) for his study on soft power’s positive contributions to global trade.

Our first measure, taken from Gallup, is derived from responses to the question, “Do you approve or disapprove of the job performance of the leadership of the United States?” This question was fielded by the polling agency beginning in 2006 in up to 157 counties. Average approval levels were calculated as the percentage of approving respondents divided by the sum of the percentage of both approving and disapproving respondents. Our second measure is derived from responses to the question fielded by Pew beginning in 2002 in up to 64 countries annually: “Do you have a very favorable, somewhat favorable, somewhat unfavorable, or very unfavorable opinion of the United States?” The response categories were collapsed to favorable versus unfavorable and average favorability was calculated using the procedure described above for average approval. Our third measure is derived from responses to the question fielded by the BBC/GlobeScan in up to 46 countries between 2006 and 2017: “Is the United States having a mainly positive or negative influence in the world?” The average scores were calculated as above. Finally, we constructed a combined measure of popular approval for the United States using all three measures, based first upon the Gallup data, with year-level gaps filled by Pew and then BBC/GlobeScan. Although hardly identical, all three measures speak to common concerns regarding popular perceptions of the United States, and as we demonstrate, they are nearly identically correlated with change in GRD both separately and together.

The control variables considered in each model are as follows. We included RAS3’s religious support index, which additively measures whether a state engages in 52 distinct forms of religious support, including laws and policies mandating religious precepts, funding religious institutions, ensuring religious monopolies on particular aspects of law or policy, and giving religious clergy or institutions official power or influence. The observed scores in our data range from 0 (states which provide no support for religion) to 46. As state support for its majority religion in particular is often highly correlated with religious discrimination, its inclusion was particularly important so as to not over- or underestimate the influence of soft power. We also considered V-Dem Polyarchy scores ranging from 0 to 1, indicating each state’s annual level of procedural democracy (

Pemstein et al. 2019), annual American exports to each country in millions of US dollars, each state’s annual real GDP per capita, population size, and log distance from the United States (sourced from

Rose 2019). Finally, we included dichotomous indicators for whether each state is primarily English-speaking (

Central Intelligence Agency 2022) or has a Christian majority (

Fox 2015).

Our models, in turn, employ random effects linear panel regressions with standard errors clustered by state. All explanatory variables excluding time-invariant ones—distance, Anglophone, and majority Christian—were lagged by 1 year to minimize endogeneity concerns. Robustness checks employing fixed effects models, which necessarily exclude time-invariant indicators, returned nearly identical results. Our first set of results in Table 1 includes four models which alternatively employ each of our soft power indicators (mean approval of American leadership, mean favorable opinion of the United States, mean positive influence of the United States in the world, and our combined approval measure detailed above) in turn. Table 2 includes these same models but restricts analysis to states deemed strong democracies (i.e., those states with a V-Dem Polyarchy score of 0.8 or higher). Table 3 again employs these same models but restricts analysis to non-democracies, or those with a V-Dem Polyarchy score of less than 0.8.

5. Empirical Results

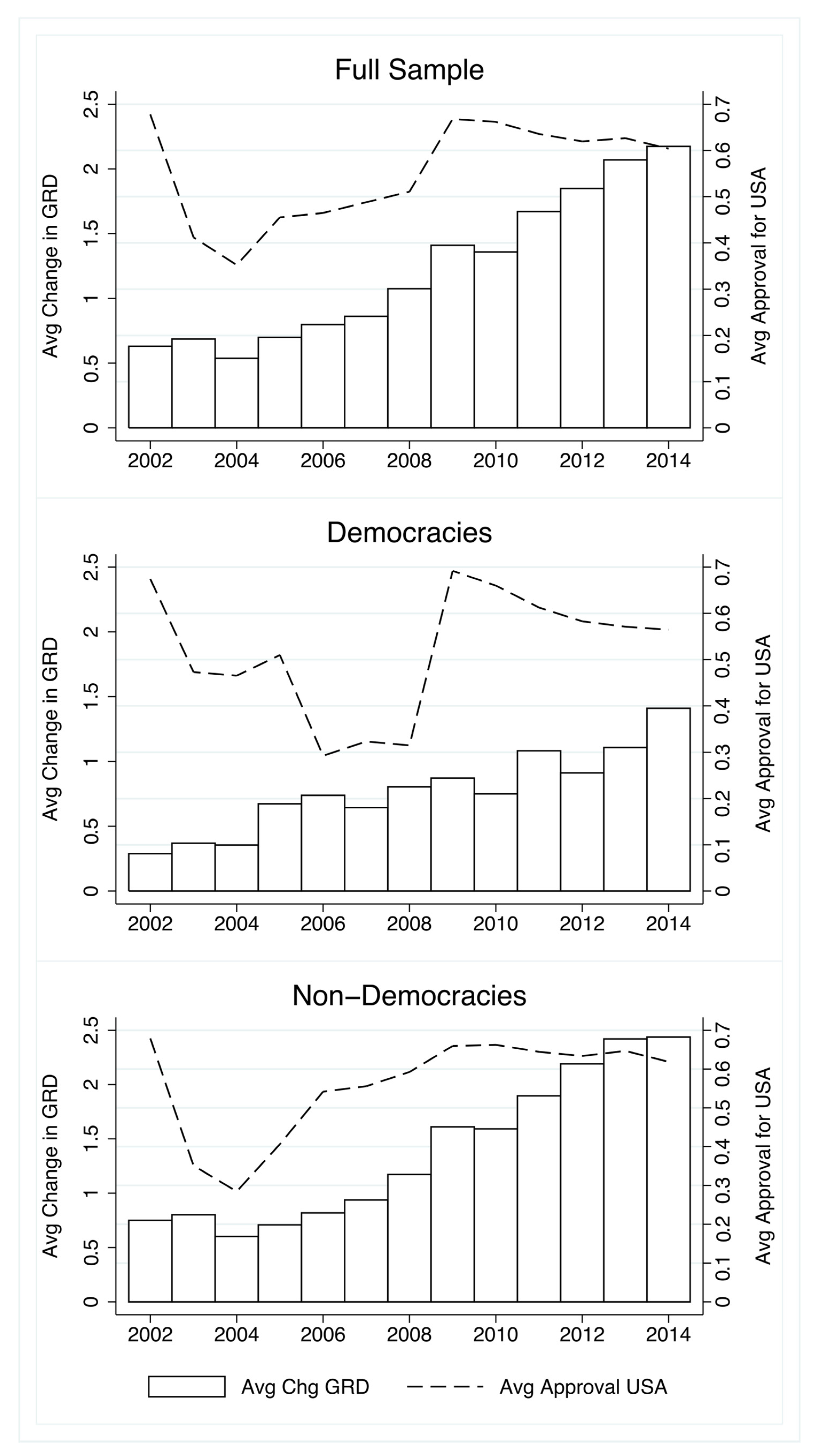

When examining the general trends via

Figure 1, it is readily apparent that governmental discrimination against religious minorities is on the rise globally, both in democratic and non-democratic states, confirming research conducted elsewhere (

Fox 2019,

2020,

2021). It is also clear that whereas popular approval of the United States among the surveyed states is also generally on the rise, these patterns vary considerably between democracies and non-democracies.

Among democratic countries, a precipitous decline in support for the United States is evident after 2002, correlating with the American invasion of Iraq. Such attitudes remarkably improve following 2008, correlating with the presidential election of Barack Obama, albeit again with a gradual decline in support until 2014 (

Lindsay 2011). Among non-democracies, however, a similar decline occurs following 2002, yet attitudes begin to consistently recover from 2004 following the reelection of President George W. Bush. This improvement may also be associated with Iraq’s election establishing a transitional government in January 2005, followed by the ratification of a new Iraqi constitution and election of a new Iraqi National Assembly with relatively broad popular participation (

Farber 2009). Whether or not increasing popular approval for the United States is indeed best explained by American efforts to restore its global democratic commitments (

Entman 2008;

Goldsmith and Horiuchi 2012), one thing is clear. These developments seem to have had little to no influence on America’s capacity to promote international religious freedom.

These troubling intuitions regarding the failures of American IRF promotion are further confirmed in our regression models. Whether considering mean approval for American leadership, favorable attitudes toward the United States, belief in America’s positive influence on the world, or our measurement combining these indicators,

Table 1 reveals consistently strong and significant correlations between positive attitudes toward the United States and increases in GRD since the IRFA’s passage in 1998. While these results hardly indicate that international religious freedom promotion “causes” increasing levels of governmental religious discrimination, it is readily apparent that positive impressions of the United States (i.e., American soft power) have not been a catalyst for greater religious freedom. We also find, generally consistent with analyses elsewhere in the politics and religion literature, that greater state support for the majority religion and larger state populations are correlated with increases in GRD (

Fox 2008,

2016,

2020).

The results in

Table 2 for more democratic states, our “easy” test of IRF promotion, are even less encouraging. Here, we find that even in those countries in which we most expected greater American cultural influence, we again find nearly across-the-board significant correlations between positive attitudes toward the United States and increases in GRD. This increase is also distinctly correlated with state support for the majority religion and population size, as in

Table 1, as well as greater GDP per capita. This implies that among more democratic states, positive attitudes toward the United States, an often-assumed critical indicator of American soft power, have done little to nothing to prevent greater restrictions on international religious freedom.

Finally, the results in

Table 3 strongly suggest that for less democratic states, positive attitudes toward the United States are in no way meaningfully associated with changes in GRD. We also find in these models, unlike in the general sample and the democratic sample, that increasing American exports to non-democratic countries are associated with a significant rise in GRD. Although perhaps a cruder measure of soft power than popular attitudes, it has often been argued that greater economic interdependence should foster greater cultural influence (

Nye 1990;

Rose 2019;

Trunkos 2021). Trade may also be a more effective means for democratic states to influence the interests and societal preferences of less democratic states without directly challenging the illiberal attitudes or policies of authoritarian rulers (

Gallarotti 2011;

Milner and Kubota 2005;

Nye 2009). Our results therefore suggest that even this soft power instrument has generally been ineffective in advancing religious freedom.

In summary, our analyses strongly indicate that increases in American soft power, whether measured via popular attitudes toward the United States or increased economic interdependence, have done little if anything to advance the cause of religious freedom. This appears to be true not only when all countries in our sample are taken in aggregate but also for the seemingly hard cases of less democratic states and even the easy cases of highly democratic states. Alternatively, it may be that American devaluation of IRF promotion has resulted in a situation in which avoiding aggressive critiques of religious repression has encouraged the publics of those very states that engage in high levels of religious repression to look upon the United States more favorably. Either conclusion should be deeply troubling for IRF advocates.

6. Implications

This article sought to test the extent to which popular approval for the United States has correlated with a rise or fall in states’ levels of GRD against religious minorities since the IRFA’s passage in 1998. In particular, we differentiated between highly democratic and non-democratic states on the intuition that American soft power influence should be greater over those countries with which it shares democratic values. As such, any significant reduction in GRD correlated with a rise in support for the US among non-democratic states should be a very hard test of American IRF promotion efforts, whereas the failure to find any such reduction among democratic states given improvement in public esteem for America should be particularly damning.

Altogether, we found that our models failed not only our hard test but also our soft one, suggesting, at the very least, a very low efficacy for American IRF promotion. Alternatively, our findings hint that American deprioritization of IRF may indeed improve US soft power resources, broadly speaking, but in a manner that significantly impinges upon its abilities to press IRF and other moral and normative agendas. Both conclusions support longstanding critiques of IRF promotion from opponents and advocates alike, with religious freedom being a potentially effective tool for mobilizing domestic political support from religious conservatives but ineffectual if not counterproductive for actually redressing religious repression.

Given the absence of a critical counterfactual, namely an American administration that has truly and unreservedly supported the advancement of IRF, it is difficult to know if our results follow from policy neglect or from negative externalities of what limited IRF promotion efforts have been made. What is apparent, contrary to the aspiration of IRF proponents, is that American efforts to date are not succeeding in advancing religious freedom. Rather, the world has seen an across-the-board reduction in IRF, even as popular attitudes regarding the United States have generally improved from their nadir in 2004–2006.

What should soft power advocates make of these developments? We propose three takeaways. First, improved regard for a state seeking to exercise soft power by a state targeted by soft power initiatives does not necessarily influence the likelihood that their policymakers will be persuaded to shift their policy agendas, even in democratic regimes where we would most expect this to be the case. Second, cultivating soft power resources may entail substantial concessions by influence-desiring states on moral-normative objectives. In other words, turning a blind eye to objectionable practices may actually lift popular esteem for the potential influencer, granting it greater leverage in other policy arenas. Finally, influencer states must sharply consider the extent to which they value a desired policy change in a target. As may be the case in IRF promotion, the stick can be equally important to the carrot such that overreliance or sole reliance on moral influence or popular reputation appears to be a disturbingly counterproductive means to promote policy change in the short-to-medium term.