Abstract

Continuing the long tradition of the allegorical interpretation of the Mass, the seventeenth- and eighteenth century ideal of proper mass attendance was devotion to the suffering Christ, inextricably linked to each step of the liturgy. In this article, post-Tridentine mass books, booklets, or chapters on the mass in devotional books for lay people, are investigated to understand the praxis pietatis in which they were embedded. These texts served devotional and educational purposes outside mass as well, but primarily they reveal a concerted effort to promote active participation of lay people at mass. In the post-Tridentine era, the mass books for lay people became a kind of Passional, serving active participation of the faithful at mass as a devotional practice configured to the actions of the priest as mass progressed. Joining Ordo and Passion, the mass books combined two dimensions of the one sacrifice with the main objective being to support a heartfelt, attentive focus on both. Based on the mass books and other devotional texts investigated, no sharp distinction can be made between attending the formal liturgy and engaging in a devotional practice as the Passion narrative unfolded in, and by, the actions of the priest.

1. Introduction

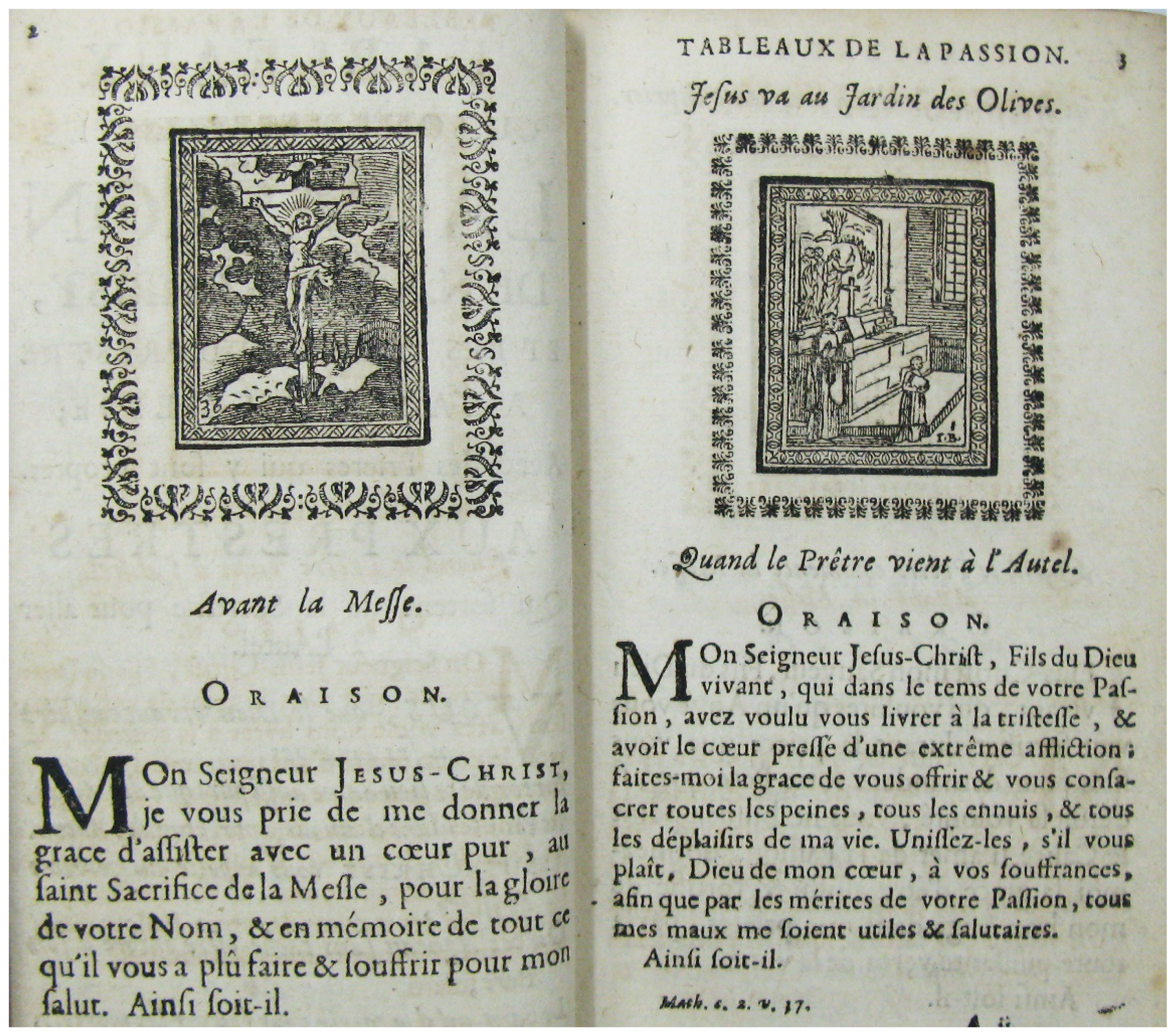

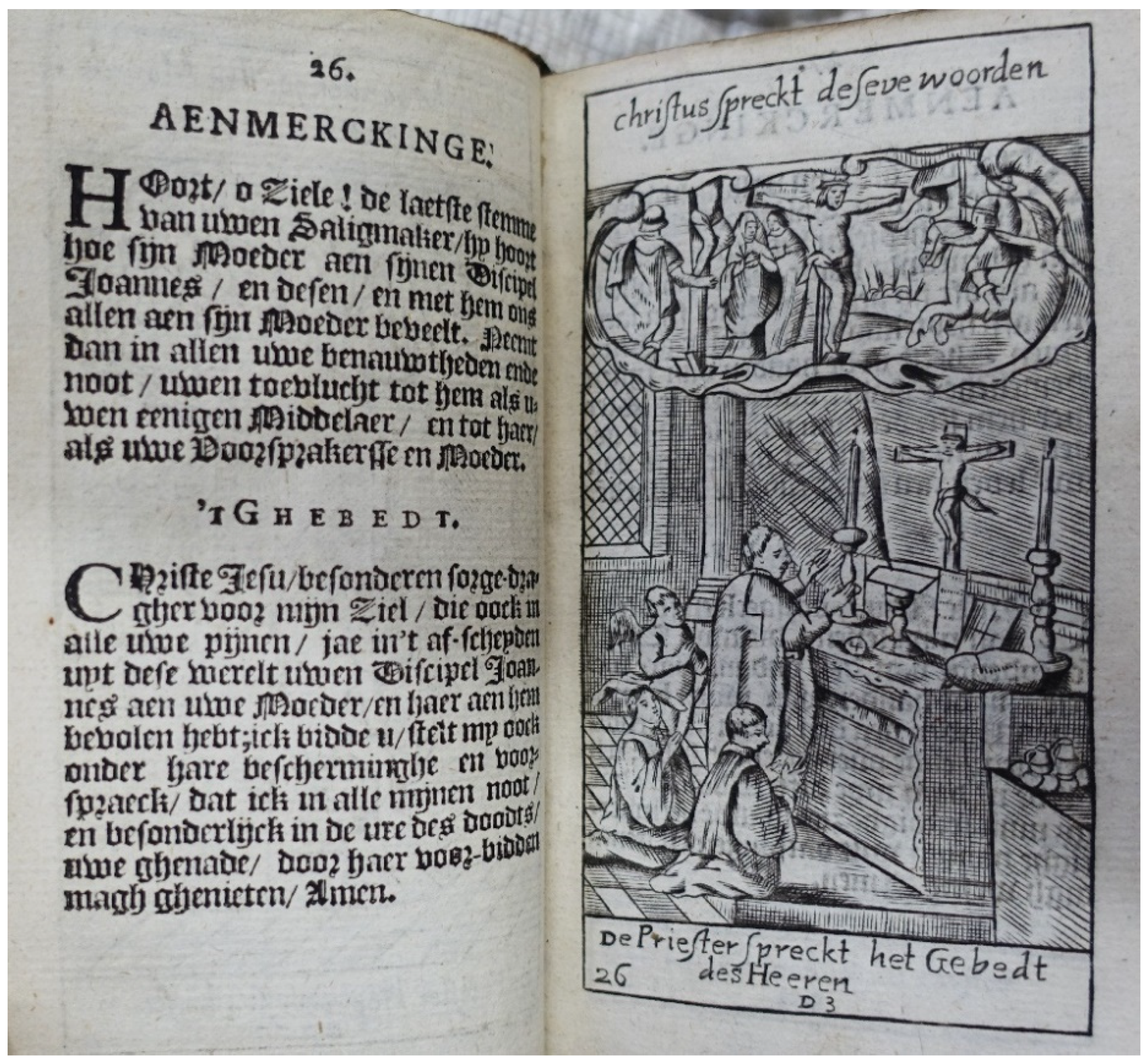

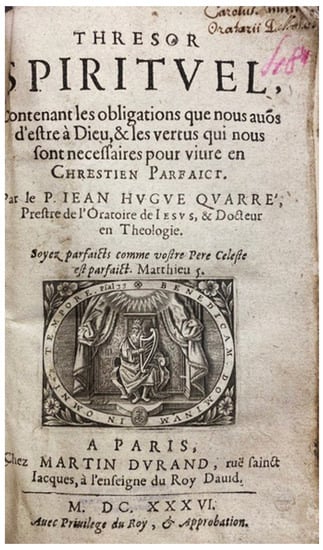

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, active participation of the Catholic faithful at mass consisted of being present with a devout affection of the heart.1 To properly attend mass was to focus on the celebration at the altar, while simultaneously practicing a pious devotion to the suffering Christ, blurring the border between participating in the formal liturgy and engaging in a personal devotional exercise. Through a complex of explanations, descriptions, images and pious exercises, mass books were meant to cultivate the proper kind of mass attendance, important in the wake of the efforts of reform encouraged by the Council of Trent. Thus, the images in such books became true “tableaux de la Croix” (Mengin 1657), presenting the celebration of the mass as the “Perpetuum Sacrificium Crucis et Altaris”, according to the inscription on each double page in the Altera Perpetua Crux Iesu Christi, published in 1649 by the Jesuit Father Joost Andries (1588–1658).

This article explores how the mass books reveal the post-Tridentine spirituality of active participation at mass as the most prominent praxis pietatis in which people could engage. Since the mass sacrifice was regarded as a re-enactment of the Passion, the objective is to investigate the spirituality and imagery embedded in the kind of post-Tridentine mass books that taught the faithful how proper mass attendance should become a devotion to Christ crucified. Such texts promoted a “Devout way to attend Mass in a profitable and attentive manner, by reflections, meditations or contemplation on the Passion of Christ which is signified throughout the entire Mass”, as one could read in the early eighteenth century Het goddelyck Camerken.2 In his seminal dissertation from 1988, Theo Clemens brought forward the immense wealth of mass books, kerk-boeken, in the Netherlands between 1680 and 1840, but he also invited further research.3 The main focus in this article is the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century ideal mass attendance, revealed and promoted by these texts, thus presenting an important part of the multiform image of religious fervor in the age of the Baroque (see Dinet 1993, p. 282). French and Dutch texts are primarily examined in this essay as a pars pro toto. Focusing on the relation between devotion to the suffering Christ and the progress of mass, rather than on the more formal expositiones missae, the essay targets the spirituality of mass attendance, what Bernard Chédozeau in 1996 regarded as “une autre forme de traduction par l’esprit” of the reality of the mass (Chédozeau 1996, p. 217). Though this essay does not deal extensively with the art history of the illustrations, special interest is shown in a much-used series of thirty-five pictures, appearing around the middle of the seventeenth century, in the tradition of the mass allegory describing the progress of the ordo and the Passion, the unbloody re-enactment of the bloody sacrifice of Christ on the Cross. Varying only in the details, the various sequences of this imagery simultaneously rendered the actions of the celebrant and how they re-enacted the Passion of Christ, making it easier to follow the progress of the mass and “fixer l’imagination”, facilitating an almost Ignatian composition of place.

The rather ekphrastic texts lead the faithful from stage to stage through the double proceedings of Holy Mass and Passion. Hence, there are two defining criteria: structure closely connected with the ordo of mass liturgy, and devotion to the suffering Christ as the Passion narrative unfolds, configured to the ordo. Typically, such presentations of the mass were found as chapters in devotional books, or in the form of independent booklets. When the term ‘mass book’ is used here, it denotes any devotional text on the mass, structured by the liturgical stages of the ordo and their corresponding scenes from the Passion. A ‘spirituality of mass attendance’ is revealed in these mass books, what Philippe Martin has called “une pastorale par l’imprimé” and a “spiritualité par le livre” (Martin 2016, sct. 1 and 33). In this context, it may be expedient to point to the fact that many of the books enjoyed numerous editions and translations, constituting a considerable part of the market of such books. In terms of representativity and reception, this means that the prolonged life of, for instance, an early seventeenth-century text ensured its continuous influence, often into the nineteenth century, by being re-edited, re-read and re-viewed.4

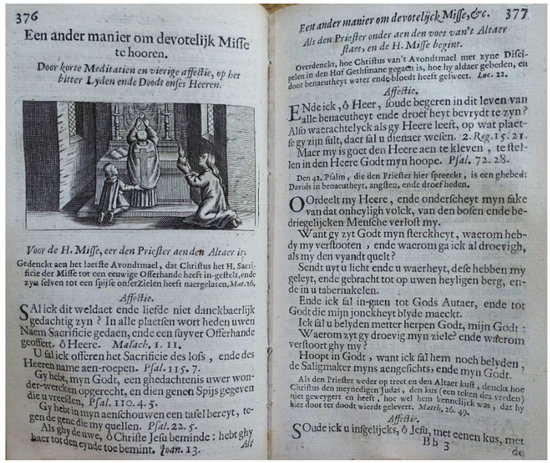

Our concern is the configuration of the devotion to the progress of the mass ordo by describing the actions of the priest during the celebration, and how these correspond to the various stages of the Passion narrative. This was executed by words painting images in the minds of the faithful, a well-known practice in the Baroque era, either by ‘word paintings’, associating with the multitude of current religious representations, or, by real images, in both cases to trigger an emotional response and provide access to the inner reality of the liturgy (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Tableau ou sont represente’s la Passion de N. S. Jesus-Christ, et les actions du prestre a la Sainte Messe, pp. 2–3. Anonymous “mass-book” c. 1740, with woodcut copies of Le Clerc. RG 3062 D13.

In a certain sense, therefore, the mass books were always “illustrated” by the ceremonies unfolding, based on the memory and familiarity with the religious iconography of the faithful. In view of the abundance of seventeenth and eighteenth century crucifixions, where a kneeling Saint Mary Magdalen embracing the cross had become part of the traditional Calvary Group, we have the model for any devout Christian, “Oh, My Saviour, would that I could remain the rest of my days like Magdalen, embracing your sacred feet!” the author exclaimed in 1672 in Pratiqve de l’amour de Dieu.5 Though without pictures, Christelyck handt-boecxken voor eenen christen mensch, published in 1706, had at each stage a description of what one saw, followed by an interior image/meditation, and a prayer, thus promoting the ideal of proper mass attendance, embedded in the Passion piety of that age. Here is the first stage, the beginning of the mass:

“When you see the priest with his servant go to the altar. Imagine that you see Jesus Christ in the person of the priest walk with his disciples to the garden, there to begin his bitter suffering and his work of our redemption; imitate him faithfully with a living faith, with love and compassion”.

Then the prayer:

“Lord Jesus, uniting with your love, through which you have sacrificed yourself on the altar of the cross for our sins, and daily grant [us] a renewal of the same sacrifice on our altars in an unbloody fashion, move my soul, that I, through sweet meditation on your holy suffering, may enjoy the fruits of it.”

Having so far introduced the scope and objective of this article, four basic phenomena relevant to this investigation will be briefly introduced. Then, an outline of the organic connection between seventeenth-century mass books and pre-Tridentine history of mass interpretation follows, including a short survey of the emergence of illustrated mass books in the middle of the seventeenth century. The article then moves on to the texts themselves. Describing the personal involvement of the faithful at mass as participation in the suffering of Christ, in devotion and individual application, it should become clear how such texts, in effect, were closely related to the Passion. The final section discusses the practical use of such devotional mass-related texts.

2. The Ordo

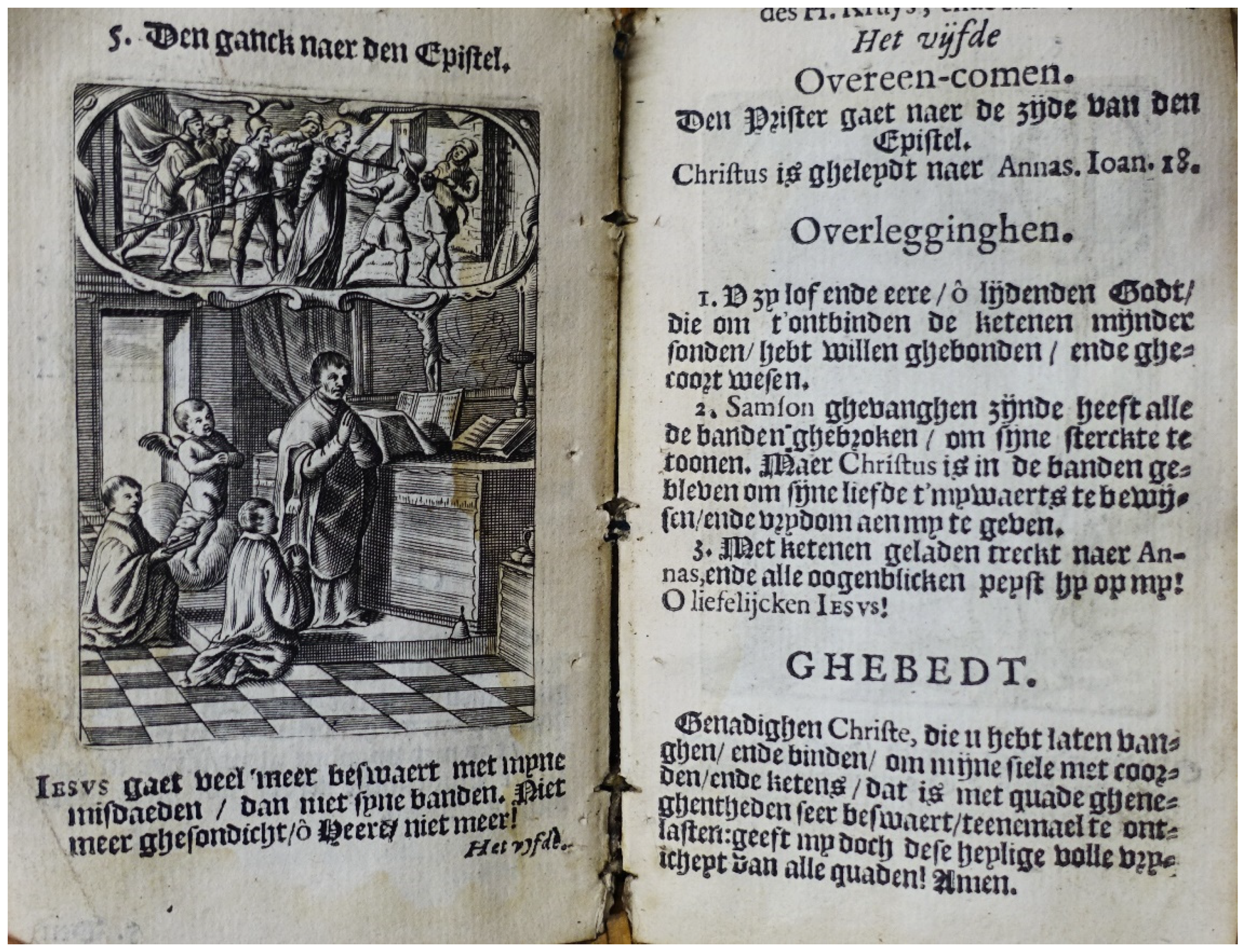

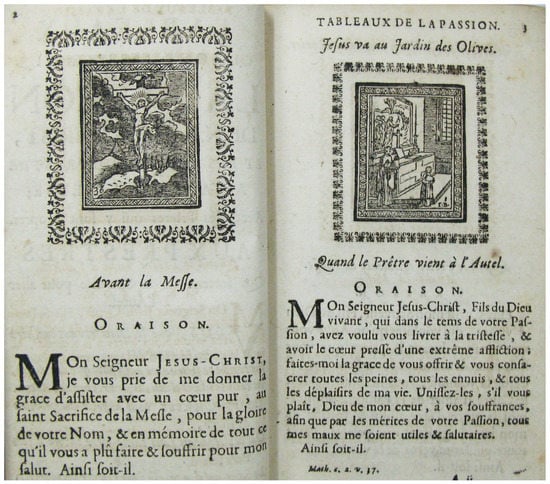

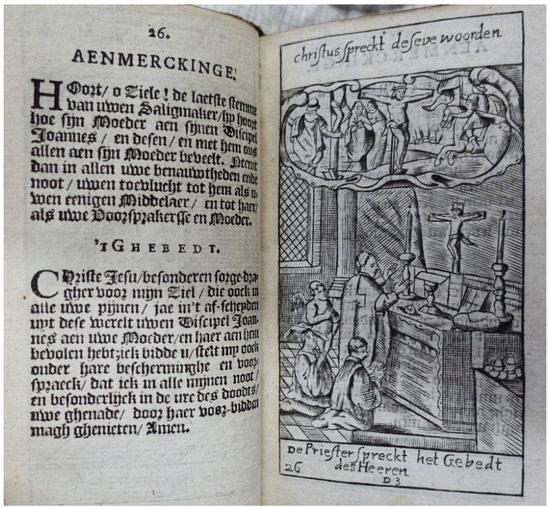

In its doctrine on Holy Mass, 1562, the Council of Trent acknowledged the role played by “external helps” (adminiculis exterioribus) in raising the meditations of the congregations to divine matters, sanctioning the very materiality of the liturgies and liturgical spaces.7 As Father Jean Jacques Olier (1608–1657), who was deeply engaged in the missions and the formation of clergy, put it in 1657, “We do not have the power to penetrate and see clearly the mysteries taking place in front of us, and that is why we need figures and ceremonies to show us outwardly what happens inwardly; to make us see in the images what we cannot see in real life”.8 Traditionally regarded as a concession to human weakness, this view had by then become a fixture in Counter-Reformation apologetics. A detail, such as the moving of the missal, offers an example of how each exterior part of the mass ordo became a source of allegorical interpretation. Since the high Middle Ages, the altar had had an epistle side (south) and a gospel side (north). In 1608, Luca Pinelli made the readings and the moving of the book on the altar into a three-phased devotional practice:

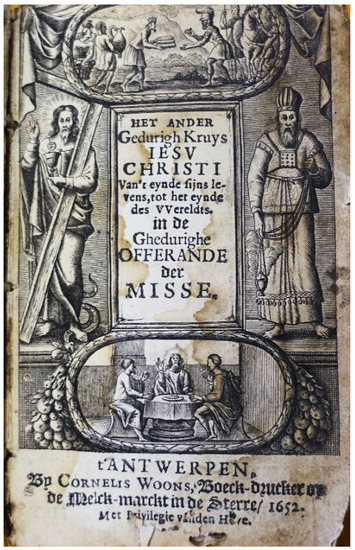

“When the epistle is read, consider in your mind how much work the prophets, apostles and other of Christ’s disciples who wrote these epistles put into leading the Jews to the recognition of Christ, yet since they would not accept him as their Messiah, they were themselves forsaken by God. So, you pray, that he does not abandon you also. As the book is moved to the other side of the altar, you will consider how the doctrine of the Gospel, which opens the road to eternal salvation, was transferred to the Gentiles, as the Jews were not willing to accept Christ due to the hardness of their hearts. When the Gospel is read, you will imagine for yourself Christ preaching and showing the way to eternal salvation. You thank him, and you will listen to the Gospel with devotion”. Figure 2. Joost Andries: HET ANDER Gedurigh Kruys IESV CHRISTI, Antwerp 1652. The priest goes to the epistle side of the altar, corresponding to Jesus being brought before Annas. RG 3073 D15.

Figure 2. Joost Andries: HET ANDER Gedurigh Kruys IESV CHRISTI, Antwerp 1652. The priest goes to the epistle side of the altar, corresponding to Jesus being brought before Annas. RG 3073 D15.

The focus of the faithful should be on what was going on at the altar, as the “figures and ceremonies” unfolded the sacrifice, the mass books contributed to improving the laxness of the age. The mass had not changed that much; what needed to change now was the attitude of the faithful. The mass books were meant to support and promote the concentration and attentiveness needed for assisting at mass properly; their descriptions of the scene from the Passion were at times a veritable emotional ekphrasis. As a direct result of the Council of Trent, the “Tridentine” mass ordo was promulgated in 1570 by Pope Pius V (1504–1572) in his apostolic constitution, Quo Primum.10 The constitution regarded the “new rite” as a restoration of the old missals “to the original form and rite of the holy Fathers”, creating a liturgical uniformity on a level probably never experienced before in the history of the Western Church.11 For all practical purposes, the ordo of the mass was now fixed, to be celebrated and recognized everywhere. For 400 years, it remained unchanged, the mass that every Catholic knew and attended on at least Sundays (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Title page of Dutch translation of Luca Pinelli: De chracht ende misterie de H. Misse met verklaringhe der selve, with a wood cut of mass celebration, Antwerp 1620. RG 3071 L5.a.

Since the ordo remained the same, the variations are only found in the text apparatus attached to the images/stages. The images and texts should not be separated; stage by stage, inscriptions, images, subscriptions, descriptions, meditations, and prayers constituted a whole, a complex, a tableau, a devotion.12 In terms of book production, the enhanced uniformity of the mass celebration ensured a common basis for all of the editions, not least due to the uniformity of the rubrics and their corresponding images. As before the Council of Trent, every mass sacrifice remained a commemoration of the passion, death, and resurrection of Christ. Nothing new was introduced in 1570, but, aligned with the endeavors to reform, more emphasis was put on proper participation. Those with the responsibility for souls, the Council stated, should take care to explain the ceremony and mysteries of the mass sacrifice.13 The mass books did just that, and almost immediately, translations of the Latin text of the ordo were to be found in various devotional books. One such example is Adam Walasser’s (c. 1520–1581) Messbüchlein from 1573, where the ordo, including the Canon prayer, was translated into German; the book itself, however, was based on a late medieval mass explanation published in Nürnberg c. 1480, employing the allegorical method, and aiming at devotional participation (Walasser [1573] 1575; see Reichert 1967). In 1661, however, Pope Alexander VII (1599–1667) forbade all translations of the Roman missal, reacting to the protests of the French clergy to a five-volume translation of the Missal, published by Joseph de Voisin (1610–1685) in 1660. In 1682, however, the Jesuit Father Nicolas Tourneux (1640–1686) could still offer a complete translation in his L’Année chrétienne, precisely to promote a more devotional approach to the ordo.14 The actual reception of the Body of Christ was limited to a few Sundays during the year—the stipulations of the Council and its catechism not so much establishing a practice rather than reflecting it. For most people, before and after the Council of Trent, this would be one of their devotional exercises, whether they attended mass in the church, or, if sick or otherwise indisposed, spiritually at home.

3. Devotion

To some extent, all Catholics were expected to engage in devotional practices, attending mass being the most prominent and necessary of these, and until the end of the eighteenth century, almost everybody attended mass on Sundays and on several feast days (Cloet 1986, p. 612). In almost any devotional practice, tangible and intangible components are inextricably entwined. In his catechism of 1555, Summa doctrinae christinae, Petrus Canisius (1521–1597) regarded the visible ceremonies to be signs, testimonies, and exercises pertaining to the inner cult (cultus interioris), which was always the main achievement.15 Even when one beholds the crucifix with respect, bows to it in reverence, kisses it out of love, touches it in faith, it is not the object, but He whom it places before our eyes that one’s soul worships in the spirit, as explained by the Jesuit Father Richiome (1544–1625), employing the Catholic standard defense against accusations of idolatry.16 The objective of religious instruction was precisely to cultivate this inner cult, and its relation to the outer cult represented by the ordo. In 1573, Walasser pointed out that the devil knows full well how powerless he is against Christians who engaged in “daily and constant meditation on and remembrance of the unique sacrifice on the Cross”. We should, he said, decorate the church with paintings, or at least have a Calvary group, yet “first and foremost we should paint or draw in our soul the Lord Jesus on the Cross, that we may never forget the suffering of our dear Lord Jesus Christ, but everyday behold it with devotion, from the beginning of his life until his bitter death”.17

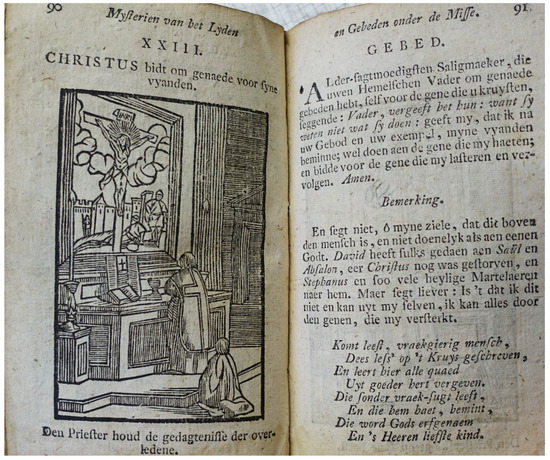

Such pious prayers and meditations are not, however, ‘a devotion’, but devotion as a general spiritual disposition expressing and nurturing one’s faith. A devotion in our sense, on the other hand, while certainly a way to serve one’s God, is a religious practice, consisting of an established structured expression of personal faith, focusing on a specific element, employing appropriate instruments, such as actions, prayers, and objects (see von Achen 2007, pp. 24, 28). The distinction between the inner and outer cult formed the basis of an almost phenomenological perspective on devotion, the various (exterior) devotions being nothing but specific expressions of the (interior) devotion. In the second edition, 1636, of his Thresor spiritvel, this was explicitly expressed by the Oratorian, Father Jean-Hugues Quarré (1580–1656):

“Concerning true piety, there are two thing to consider, one is interior and at the bottom of the soul, the other is exterior and consist of actions: we regard the interior as the principle, the root and cause of true piety, and the exterior is like the flower or fruit, since all devotional exercises visible to human eyes are just outward marks of the piety, but true piety is an interior matter (…) that is why those who study only the exterior, and those who only care about producing a thousand exercises, beautiful in appearance, they catch (ont bien) only the image or shadow of piety”. Figure 4. Title page of the second edition of Jean-Hugues Quarré: Thresor spiritvel, Paris, 1636. RG 3037 D.10.

Figure 4. Title page of the second edition of Jean-Hugues Quarré: Thresor spiritvel, Paris, 1636. RG 3037 D.10.

To Quarré, devotion is the inner source of the various outer actions and as such it appears in the exterior forms of various ‘devotions’. He did not imply that such devotions were unimportant—they were the fruits of devotion—only that one should be aware of the relationship between them and their source. Another Jesuit, Father Barthélemy Le Maîstre (1642–1679), found devotion a necessary virtue to practice, yet to be controlled by prudence. In addition to this (general) devotion, a Christian had to have “exercises de pieté reglez”.19 To be ‘a devotion’, then, requires a pre-established processual structure and props, that is why the Dictionnaire de spiritualité mentions two distinct features found in the definition given above, namely concretization, and organization.20 A devotion can be practiced alone or collectively, though ideally, even collectively, it always presupposes a strong personal attachment to the element in focus. The explicit, structured focus and inner disposition needs devotional instruments, be they images, books, rosaries, gestures, or acts, intimately connected with the structure of the practice.21 As we shall see, attending the mass as a devotion to the suffering Christ is covered by the definition given above.

Through the anamnesis, the spiritual presence at biblical scenes remained part of the charisma of liturgical celebrations and formed the core of the important devotions, such as the late medieval Stations of the Cross, or, indeed, an entire spiritual pilgrimage to the Holy Land, not least with ample focus on the Passion; thus, the Carmelite Father Jan Pascha’s (c. 1459–1539) manuscript on the spiritual pilgrimage to the Holy Land was published by Pieter Calentijn in 1563, illustrated with rather crude woodcuts. Pascha offered a reason which is valid for our mass books as well: since we cannot actually (bodily, lichamelÿcken) visit the holy places, we can still do so “bÿder gratien godts met deuote meditatien» (Pascha [1530] 1563, p. 1a). In that respect, however, the mass was not only the most prominent of such devotions, but unique, since it simultaneously created an actual and spiritual presence of that which is commemorated and represented, a “renouvellement effectif”.22 Similar to what a painter does, the Dutch Jesuit, Lodewijk Makeblijde (1565–1630), told the readers in his preface to Den hemelschen handel der devote zielen, published in 1625, the contemplative is painting and impressing on the panel of the forces of his soul, reason, mind, and will, the things upon which he meditates.23 The mass books endeavored to support such procedures, while the main image, the source of all other imagery, remained in front of everybody: the unbloody re-enactment of the bloody sacrifice on the Cross. This was not, however, an analogy to the traditional concept of how the religious image worked, namely as a (material) object pointing (depicting) to the original. The connection between the mass and the Passion was much more intimate, much more immediate, like two dimensions of the same thing. Likewise, while the liturgy of mass may be called a ‘Divine theatre’, due to its obvious theatrical aspect, the suffering of Christ being a true “theatrum doloris et amoris” or “theatrum humilitatis”, it was much more intimately connected with the story it renders than any work of art. It was what it represented.24 Thus, at the mass, the congregation did not adore Christ through the image presented by the mass, but Christ himself as image.

4. Active Participation

Based on erudition and devotion alike, the promotion of active participation at the mass was an important issue for the Council of Trent. To restore the dignity and cult for the glory of God and the edification of the faithful, anybody with responsibility for souls should see to it that what happened at the mass was explained, ensuring that those attending “were present not only in body, but also in mind and devout affection of heart”.25 As we shall see, this was followed up by religious missions as efforts to boost spiritual life in parishes (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Willem Kerricx (1652–1719): Model 1687 for a bas-relief for the Dominican St. Paul’s church, now in St. James’ church, Antwerp.

It is, however, expedient to make a distinction between the post-Tridentine ideal of active participation to be investigated here, and the actuosa participatio as a term in the Constitution on Sacred Liturgy of the Second Vatican Council.26 The specific context of the term was provided by the Liturgical Movement, since the later part of the nineteenth century, which advocated a different kind of active participation, and a different ecclesiological view on lay people in general, and which eventually came to be articulated in the Council’s Dogmatic Constitution on the Church. This article concentrates on the quite different design of the participatory dimension of the mass celebration in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In 1608, the Jesuit Father Luca Pinelli (1542–1607) presented the inner disposition necessary to achieve proper participation, namely that the faithful “ought to be well prepared and organized in terms of intention, attention and devotion, that mass may be nothing but a commemoration and representation of the Passion of the Lord”.27 It was not two parallel events taking place, but active participation demanded the conscious and devotional mutual configuration of ordo and Passion. At the end of the same century, Oratorian Father, Julien Loriot (1633–1715) mentioned three important components of perfect attentiveness during mass: to sacrifice one’s spirit by earnest attention; one’s heart by fervent love; and one’s body by total mortification of the senses.28 The last point served the omission of distractions, that the faithful be truly present, body and mind. To participate actively at mass was to be absorbed in the devotional reception of the original sacrifice re-enacted on the altar.

Despite the considerable difference between the way the Council of Trent and Vatican II defined active participation at mass, it was always expected of Catholics. In the post-Tridentine era it did have a concelebrational aspect as it joined the faithful to the priest, the mass book making it easier for them to unite with him in the sacrifice, which was theirs with him, “ce Sacrifice qui leur est commun avec lui”, as stated in a mass book 1722.29 Yet, if those attending mass were “circumstantes” a term already used by Guillaume Durand (1230–1296)30, they were certainly not “concelebrantes” in the sense of Vatican II, despite some similarities of expression. Moreover, during the Latin mass, participation of the people may well have been active, but it also seems to have been largely silent. In that respect it is interesting that the common series of images, introduced in mid seventeenth-century mass books, included an allegorical figure, anima humana, representing the proper (spiritual) attendance, and also always the altar servers, since they were giving the Latin answers on behalf of, and thus representing (bodily), the otherwise silent congregation.

5. Missions

If we ask why our illustrated mass books appeared when they did, and even if we follow Clemens concerning van der Kruyssen’s Misse. Haer korte uytlegginge, 1651, as a book for the lay elite, we might suggest that the sudden outburst of illustrated mass books around the middle of the seventeenth century may have been motivated by the pastoral experience gained from the “missions” in the first part of the seventeenth century, the first in Northern France, in 1617 (Clemens 1990, p. 207). Such missions targeted entire regions to boost the Catholic faith and practice, providing a basic religious education for the rural population. The religious education of children and instruction of congregations were part of such missions as intensive educational efforts adapted to the various groups of rural recipients. Yet, the laxity of the congregations was not due to a lack of religious erudition alone, but to indifference and lack of devotion as well. The clerical authors certainly complained enough about this, such as the Jesuit Father René Rapin (1621–1687) who, in 1679, described his own time in quite unflattering terms, lamenting how the fervor of earlier times had grown cold.31 Indeed, the missions grew out of the need for the rekindling of the flame. Even if the earliest illustrated mass books with their engraved suites of thirty-five images appeared in works for the middle or upper class, they soon belonged to everyone through the cheaper editions with copies of the originals. In addition to a general Counter-Reformation enthusiasm for visualization, one may well imagine that our prayer books were suited to instruct the youth in what the mass was and how to attend properly, assisted through images of what the people saw happening at the altar, including short texts or prayers of a devotional character.32 The idea behind the missions was an almost systematic revitalization of faith, battling the religious ignorance of common folk and reviving their Christian devotion and practices. In a post-Tridentine perspective, such endeavors made sense, since Protestant heresies were regarded by the Catholic church as due to ignorance, sin, and a lack of proper instruction (Dompnier 1997, pp. 621–52, here p. 624). Part of creating a Catholic awareness was to emphasize the priestly role, as the mass books certainly did (Dompnier 1997, p. 629). In his preface, van der Kruyssen expected his book to “increase the piety and erudition of the unknowing”, and, as a devotional manual, it could even serve the necessary instruction of people without interrupting the liturgy. No wonder that the part with the various stages of celebrated mass became very popular, due to its illustrations and brevity alike.33 Though educational rather than devotional, the exercises, catechisms, and catechesis prepared the ground for our mass books in emphasizing the need for devotion to the suffering Christ. Thus, the catechism of the diocese of Meaux (1764) invited the faithful to “contempler Jésus Christ mourant comme si on étoit sur le Calvaire”, while the catechism of Montaubant (1765) admonished the faithful to “réfléchir sur les sounffrances et la mort de Jésus Christ” (quoted in de Viguerie 1996, p. 100).

Initiated above all by the Jesuits in the first half of the eighteenth century, “Volksmissionen” took place in German-speaking areas as well, in Southern Germany, Rhineland and Austria. In the same way as in France and Flanders, the main purpose was to strengthen Christian doctrine and devotion. In a catechetical mission taking place in the diocese of Passau, Bavaria, in the later part of that century, a Jesuit would instruct the people during the mass in the mysteries of the suffering of Christ, connected with the ceremonies and the actions of the celebrant, illustrating the practice endorsed by the Council of Trent.34 Already published devotional texts reappeared again and again in new and rather modest editions, with only slight changes throughout the eighteenth century. Moreover, in the eighteenth century it was not uncommon that book sellers accompanied the mission priests, since the distribution or selling of devotional books formed part of many missions, not least to prolong their effects (Châtellier 1997, pp. 758–60). It is not difficult to see how popular, illustrated booklets on the mass, accessible to most families, could work as expedient visual instruments during and after such missions. A German parallel to our mass books may well have been sold during the mission in Passau to support the instructions. Their small size made them ideal as a combination of devotional book and a guide to the theatre of the Holy Mass (see Jungmann [1948] 1952, p. 199). Once introduced, they seemed to have appeared in great numbers as rather plain, small-sized leaflets of less than a hundred pages with simple illustrations, fitting into most pockets.

6. Allegorical Interpretation and Seventeenth-Century Illustrated Mass Books

Since the early Middle Ages, the anamnetic re-enactment of the life of Christ had been a central theme in the liturgy of the eucharist, fostering an allegorical interpretation most prominently presented in the Liber Officialis from the 820s by Amalarius of Metz (c. 775–c.850). Each stage of the actual physical ceremony of celebrating the mass pointed to a certain event or scene from the life of Christ, or from his suffering, death, and resurrection. Thus, the ceremonies, with their visible actions and tangible objects, were seen as allegories revealing the invisible realities embedded in them. The most influential later expositio missae was written around 1285 by Guillaume Durand, Rationale divinorum officiorum, from which a single quote suffices, “the office of the mass is arranged in such a way that the things achieved by Christ and in Christ, from [when] he descended from heaven until he ascended, largely exist and are represented in an admirable way by words as well as signs”.35 In the Late Middle Ages, the mass had become ever more a liturgical commemoration and re-enactment of the Lord’s Passion (see Dlabacova 2019, pp. 199–226). Benefitting from the introduction of print and printed books, the mass books meant for lay people were already on the market long before the Council of Trent. In that respect, the texts and imagery investigated here continued a long devotional tradition of the allegorical interpretation of the ceremonies taking place in front of the congregation, as the liturgical “now” was inextricably linked to the biblical past as its true re-enactment.

A regular illustrated mass book, “Dat boexken vander missen”, was published in 1506 by the Franciscan, Father Gerrit van der Goude. We may regard it as a typical late medieval forerunner of the post-Tridentine mass book, with allegory endeavoring to unite interiorization and institutionalization as the two roads to piety (see Angenendt [1997] 2009, pp. 190–91, and Reichert 1967, in general). Images showed each stage of the liturgy and what it signified, supporting meditation and personal application in the form of prayer, and an Our Father and Hail Mary.36 In his preface, van der Goude made it clear that the book was meant for laypeople who wanted to attend mass with devotion:

“Those who want to attend mass with much profit read the prayers to each article; or if he cannot read, then he can meditate devoutly on the life of our Lord and pray at each article an Our Father and a Hail Mary, then he would have prayed as many Our Fathers as the years our dear Lord lived on earth”.

The spiritual gain depended not only on what you read, but also on how you read it. This is the tradition of lectio divina, on the very threshold of the post-Tridentine era, around 1560, expressed in the Thresor ou coffret spirituel by Benedictine Father Louis de Blois (1506–1566). He stated that the devout reader should recite the meditations and prayers slowly, and with attention, and also add what God and the devotion inspired, since, if recited attentively with heart and mouth, the meditations would soften hardened hearts, and thaw frozen hearts.38 As we shall see, using the mass books as devotional literature demanded the same way of reading them.

A stream of mass books for lay people, structured by the Tridentine Ordo of 1570, might have been expected in the decades around 1600 as a move to establish the new ordo and reform the faithful. One reason that this did not occur may be that the mass had not changed that much, and the older books, for a time, supplied the market adequately. Meditations with points to consider, an image, a description of the fruit of the meditation, and a long prayer as a conversation with Christ, appeared rather early, namely Luca Pinelli’s Libretto di brevi meditationi del santiss. Sacramento from 1598 (Pinelli 1598). It has several woodcuts illustrating mass, but it was not structured by the ordo, which is one of our two defining criteria. Our other criterion is the connection between the mass ordo and the Passion. Both these requirements were met by Matthias Pauli in Ghebeden ende Meditatien op de Ceremonien vande Heylighe Misse nae het Roomsch ghebruyck, published in 1618. Apart from lacking illustrations, it had all the characteristics of our mass books. Presenting the reader with a devotional complex of verbal imagery, meditations, and prayers, it provided the components and the structure of devout mass attendance that were to appear in so many variations (see Cousinié 2008, pp. 120 and 122). In 1646, Claude Bazot published a leaflet on the mass, L’Explication des ornemens et cérémonies de la sainte messe, explaining how it represented the passion and death of Christ, but still without illustrations of the ordo.39

In 1651, however, a Flemish priest, Andreas van der Kruyssen (1610–1663), published an illustrated mass book for lay people, Misse. Haer korte uytlegginghe. In the preface, he mentioned that, at that time, several mass books, with or without illustrations, were on the market. Some of them “rendered the [ceremonies] through pictures and comparisons with the Passion of our Saviour”, but even though they pleased him, they were either too long or needed better illustrations.40 In the very same year, a similar work by Francois Mazot appeared in France, Tableaux de la croix representé dans les cérémonies de la Ste. Messe, in Latin and French, illustrated by 98 engravings by Collin, de Gheyn and Durant.41 It was far more extensive and sophisticated than its Flemish counterpart in terms of imagery and selection of additional texts. The following year, Joost Andries published a mass book, Het ander gedurigh Kruys Iesv Christi, 1652, with the same kind of illustrations of the ordo/Passion42 (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Engraved title page to Joost Andries: HET ANDER Gedurigh Kruys IESV CHRISTI, Antwerp, 1652. RG 3073 D15.

Andries introduced his book to the reader by stating that in describing the two aspects of the mass sacrifice, one had “until now used the same 40 images and issued them in various languages mixed with god-fearing prayers and intentions”. He himself had used them in Altera Perpetua crux Iesu Christi a fine vitæ usque ad finem mundi, in perpetuo altaris sacrificio, published in Antwerpen 1649 and Köln 1650. However, now, Andries had decided to use a different suite of images, for the sake of novelty, but also to illustrate more conveniently the correspondence between the ordo and the Passion. To achieve this, he had employed the very suitable images recently used by the Jesuit Father Amable Bonnefons (1600–1653), “in which one could see clearly the correspondence between the entire Passion and Holy Mass”.43 Since the 1620s, Bonnefons had almost exclusively been engaged in the religious instruction of young people, servants, and children from poor families. Drawing on his long experience, he stated that the best way of attending mass was to meditate on the Passion of the Son of God and attach this meditation to the ceremonies of the mysteries of his Passion, performed by the priest.44 In view of this, it was hardly surprising that he should have commissioned such very direct and instructive combinations of the ordo and the Passion. The engravings in Het ander gheduurigh kruys are unsigned, conceptually similar to those published by van der Kruyssen and Mazot, separating the ordo and the Passion by cartouches and wreaths instead of clouds. Most likely it was Bonnefons’ Le calvaire mystique pour méditer sur la passion de Jésus-Christ from 1650 which provided the series copied and published in 1652 by Andries, the term “calvaire mystique” at that time indicating the altar.45

A few years later, in 1657, a third similarly illustrated mass book was published, namely Louis Mengin’s Tableaux ou sont représentées la Passion de N.S. Jésus Christ & les actions du Prestre à la S. Messe, presenting the now familiar suite of 35 engravings, this time made by Sebastien Le Clerc.46 Mazot, van der Kruyssen, and Andries all had images simultaneously depicting the liturgy and the Passion in the form of a priest at the altar with the respective Passion scenes above, separated by clouds or in a cartouche. Thus, the series provided a pedagogically apt illustration of the mass allegory. Le Clerc introduced the scenes from the Passion as changing motifs of the altarpiece. By these publications, the devotions on the suffering Christ, aligned with the sacrifice of the mass, were firmly established within a distinct category of mass books.47 Adrianus Poirters used copies of the engravings in Het ander gheduurigh kruys for his Christi Bloedige Passie verbeeld in het onbloedig sacrificie der H. Misse, published in 1675.48 Though we lack the definitive proof, it seems most likely that the suites in our mass books were introduced in France in 1650 by Amable Bonnefons as a visual pedagogical tool serving religious instruction for lay people. They were to be copied again and again for the next two hundred years.

7. The Tridentine Mass and the Passion of Christ

The Council of Trent changed nothing concerning the relationship between the mass and the Passion. The post-Tridentine mass books continued to describe and visualize how proper lay attendance amounted to a devotion to the suffering Christ, aligned with the progress of the mass. On that point, the Catechismus ex Decreto Concilii Tridentini ad Parochos Pii V Jussu Editus (1566) was clear:

“The Sacrifice of the Mass is and ought to be considered one and the same Sacrifice as that of the cross, for the victim is one and the same, namely, Christ our Lord, who offered Himself, once only, a bloody Sacrifice on the altar of the cross. The bloody and unbloody victim are not two, but one victim only, whose Sacrifice (…) is daily renewed in the Eucharist”.

The main character in the pictures of the illustrated booklets is the priest, the focus drawn to him by his visible actions making it possible to follow the progress of the mass, its importance furthermore due to the fact that “the priest is also the same, Christ our Lord” as he offered the sacrifice in persona Christi.50 The blood of Christ consecrated separately, the catechism stated, can “better and with greater power set before our eyes the Passion and Death of our Lord”.51 The mass books visualized and described the actions of the celebrant and related them to the Passion of Christ as a juxtaposition of bloody (cruenta) and unbloody (incruenta) sacrifice. The title of a devotional book by the Adrianus Poirters, was truly programmatic in that respect, The bloody suffering of Christ, represented by the unbloody sacrifice of Holy mass, published in 1675. Poirters described the two quasi “parallel” sacrifices taking place during the celebration of the Eucharist.52 From a Counter-Reformation perspective, the intimate relationship between the bloody and the unbloody sacrifice was a central argument against the criticism of the Roman mass, that it claimed to repeat what was achieved by Christ once and for all, not least from Calvin who attacked the double reality of the celebration. Due to the necessity of defending the Catholic concept of the Eucharist as a sacrifice, all efforts converged on that point, strengthening the already existent correspondence between reenacting the Passion and celebrating mass (Jungmann [1948] 1952, pp. 187–88). Emphasizing this relationship was the very point of the mass books considered here (see Bridges 2019, p. 110). “Of all exercises and devotions a Christian may engage in, frequent and devout meditation on the Passion of Jesus Christ, our Saviour, is among the most fruitful and pleasing to God”, the Spanish Jesuit, Gaspard Loarte (1498–1578), stated the very year that the new Ordo for the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass was issued in Rome.53

The Catechism of Trent made a qualitative distinction between the mass and all of the other devout activities, including between sacrament and sacrifice.54 This was important, because if meditating on the Passion of Christ was the only point, one might easily regard the Stations of the Cross or devotion to the Five Sacred Wounds as being more efficacious pious exercises than the mass with its (liturgical) distractions, a point raised by Arnold Angenendt in his seminal work on medieval spirituality (Angenendt [1997] 2009, p. 501). Precisely here, however, the configuration of the Passion to the progress of the liturgy was crucial, articulating the essential difference between a painting of the Crucified and the mass as a “Tableau de la Croix”. The mass books insisted that the Passion and ordo were integrated, rather than parallel events. Sometimes, though, the borders were blurred, for instance when a later edition of Parvilliers’ Passional from 1674, published in 1701, included the ordo and the exercises to attend mass piously, or, when a German late eighteenth-century devotional tract on the “Way of the Cross” explicitly mentioned that it was not only meant for private devotion, but “auch bey Anhörung der H. Mess zu gebrauchen”.55

8. Joining the Passion, the Mass Book as a Passional

Combining devotion and explanation in Ghebeden ende Meditatien op de Ceremonien vande Heylighe Misse, 1618, Matthias Pauli (1580–1651), Prior of the Augustinian convent in Brugge, related that “Holy Mass is nothing but the outward sacrifice which presents to us anew the life, suffering and death of Christ, (…) which by the priest is offered unto God his heavenly Father for the living and the dead”.56 The task of the mass books was to integrate Catholics into the re-enactment of this sacrifice.57

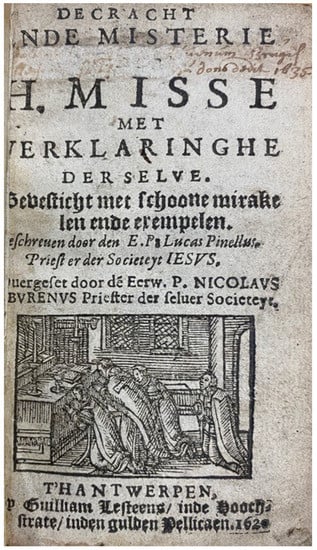

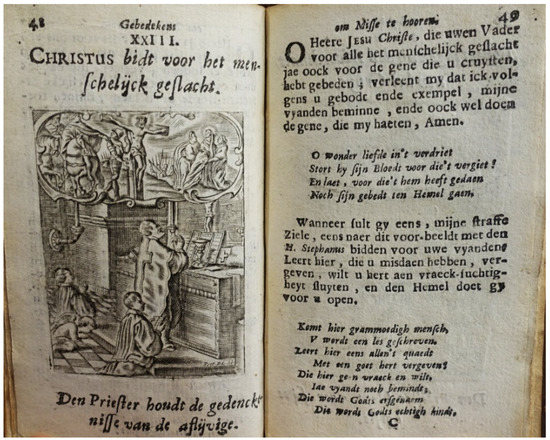

The Jesuit Father Claude Texier (1611–1687) admonished the readers of his sermons on the Passion in the following words, “The bell rings for mass; it tells you to prepare to climb Calvary (…) to fix your imagination and keep your thoughts focused; let us visualize Jesus (…), the picture (tableau) that will shape our imagination will be the indulgent Jesus in chains”.58 Indeed, to attend mass was to join the sacred events of the Passion, to insert oneself into each stage through attention to the actions of the priest (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Adrianus Poirters: Christi bloedige Passie, Antwerp 1675. From the Cross, Christ asks for mercy for his enemies, corresponding to the remembrance of the dead during the Canon Prayer. Engravings by Pieter de Loose, copied from Het ander gedurigh Kruys, 1652. RG 3048 E9.

Go to mass, the eighteenth century Christelyk onderwysingen en Gebeden (Anonymous 1770) told the reader, “as if you went with Christ to the mount of Calvary. Be there, present, like the Mother of Jesus, his beloved disciple and the holy women who stood under the Cross, to unite yourself with Christ with a heart filled with faith and love”.59 At the time of the French Revolution, Johann Michael Sailer (1751–1832) still saw mass attendance inscribed in an imaginative presence at the Passion of Christ:

“…anyone who wants to attend mass should be as if present on Calvary outside Jerusalem and truly see the dying Saviour fulfill his sacrifice of world-redemption for us and all men before the face of the heavenly Father. Anybody hearing mass should be in the mindset as if the Lamb of God who took away the sins of the world was really slaughtered before his eyes”.

Like the Passional, each stage, at times supported by an image, would lead one into the event, drawing on a long tradition going back to the Devotio Moderna of the fourteenth century, yet once again emphasizing the Ignatian practice of ‘composition of place’, compositio loci, which Texier had used. As the faithful were already physically present at the mass, the locus in question would necessarily be a certain scene from the Passion.

Imagining through the use of images was certainly no novelty in the sixteenth century, yet the interesting thing about the Ignatian way of the Exercitia Spiritualia, 1548, was that the imaginative gaze, “la vista de la imaginación”, was a structured imagination, intimately linked with contemplation—just like the mass books linked the priest at the altar to the locus depicted above the altar, creating a heartfelt devotion to what was visualized.61 If the mass was regarded as an encounter with the self-sacrifice of Christ, the images and imaginations supported, or even created, such an encounter. Having imagined the actual (historical) scene, Ignatius wanted the faithful to ask for the appropriate feelings, at the Passion, for instance, “suffering, tears and torture together with the suffering Christ”, basically the late medieval conformitas Christi.62 In 1669, the Jesuit Thomas Le Blanc (1599–1669) described the enabling quality of such imagination, “While memory tells us this story, the imagination forms an idea and a picture of it, and contemplates it, as if we were actually present and as if it were happening before our eyes; this holds and concentrates the mind and prevents it from being distracted.”63 Whether painted with words or engraved, at mass the images had become reality, combining the two dimensions of the mass sacrifice. Though the mass attendance remained a devotional practice, this did not necessarily lead to a separation between the respective foci on liturgy and devotion. Illustrations, or the rubric-like written instructions, were there to join these two aspects, which might be separated analytically but were integral parts of one and the same event. Even allowing for the ever-existent distance between ideal and reality, it remains questionable whether Clemens covered the reality adequately by stating that “The illustrations hardly encouraged its user to develop a real interest in the liturgical celebration of the mass. (…) piety went its own way, following the actions of the priest, but not touched by their proper meaning or by the text of the lessons and prayers”.64

In the mass books investigated here, several elements came together: the post-Tridentine promotion of the proper way of attending mass; the Ordo of Pope Pius V; the existing notion of mass as an allegory of the Passion of Christ; the ‘composition of place’ of the Jesuit Spiritual Exercises; and Baroque emotionality. If we imagine the mass book as a kind of devotional literature outside the mass as well, it is interesting that, in 1630, Zachmoorter recommended his Stations of the Cross as suitable devotional reading outside this particular practice, “also during mass”.65 Through their devout application of the suffering Christ to the individual faithful, their focus on the gospels and the use of images to transport the mind from what one saw to the spiritual meaning of it, the mass books contributed to the promotion of the religious culture of reformed Catholicism (see Moran 2013, pp. 219–56, here p. 248). In this perspective, Joseph Jungmann seemed to exaggerate when he explained the emergence of post-Tridentine mass books by a situation in which the allegorical interpretation of Holy Mass had lost its power to captivate people in the pews; and too influenced by the perspective of the Liturgical Movement when he thought that the people in the pews could only in a very limited sense follow the progress of the mass (Jungmann [1948] 1952, pp. 192 and 196).

The composition of place certainly needed imagination, yet not necessarily physical images. Given that the mass and the Passion of Christ could not be separated, devotion to the suffering Christ was not a distraction from what was going on, but a focus on the salvific core of it. It is important to keep that in mind when regarding the objective of the mass books investigated here. Texts, illustrated or not, were keen to explain how the two chains of events were inextricably entwined; the faithful following the unfolding as they devotionally applied each stage and each scene to their personal life and responded to it with heartfelt prayers. The illustrations were there to make it possible to recognize what was going on, and to support the focus of an otherwise volatile meditation, what Pierre Lorrain de Vallemont (1649–1721) called “pour fixer l’imagination”.66 At least, this was how proper mass attendance was meant to be, and even if the reality fell short of the ideal, this was what the mass books aimed at promoting. The personal application of the Passion, and its interiorization, promoted by the mass books as a devout presence at each stage signaled by the liturgy, depended on the attentiveness of the faithful. A clear expression of this concern about attention is found in the introductions to each meditation or prayer in Makeblijde’s Den hemelschen handel, 1625, “imagineert, aensiet, aenschouwt met uwe uytwendighe ooghen, ondersoecht, grondeert, slaet d’ooghen uwes verstandts rondt-om, aenmerckt, oversiet, hoort, siet, contempleert, overleght, and neemt acht”, or in Elswyck’s Christelyck handt-boecxken, 1706, in the words “bemerkt, peyst, overleght, aenmerckt, gedenckt, over-oeyst, wordt indachtigh, and aensieht”. As Pinella had stated in 1608, “Truly, above all, attention is necessary”.67 The prayers in Francois Mazot’s Tableaux de la Croix, 1651, are typical of the way the faithful were intended to apply themselves to the suffering of Christ, the liturgy of the mass at the same time “creating”, as it were, the various scenes of the Passion and transporting their soul and mind to them. As the priest approached the altar, the faithful would pray, “My Lord Jesus Christ, in the hour of your death you submitted yourself to fear and sadness, united with your sufferings I offer all worries and pains in my life, that by the merit of your blood, they may be salvific and profitable to me. Amen”.68 Proper mass attendance was never just a question of attending and watching, but of applying it to one’s own life, to let it inflame one’s heart.

The mass books make it clear how the inner and outer cult promoted each other, piety simultaneously shaped by faith and shaping it. Since the mass was a true re-enactment of the sacrifice once made by Christ through his suffering and death on the cross, active participation at mass consisted in imagining oneself following Christ from the Garden of Gethsemane to Calvary, applying this Divine exemplar virtutis to one’s own life. Such personal application is, for instance, voiced in the prayer from Het gulden Paradys (Anonymous 1761/1762), when the priest prays for the dead, corresponding to Christ on the cross praying for his enemies:

“Oh, most meek Saviour, who have asked mercy of your heavenly Father, even for those who crucified you, as you said: Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do; grant me that I, according to your commandment and your example, love my enemies, do well to those who hate me, and pray for those who slander and persecute me. Amen”.

Not least for the Jesuits, active participation was paramount; the personal prayer and participation in the cult, the inner life, and the liturgy, were intimately connected (Martin 2016, sct. 18). Without disregarding all of the other forms of devotions, the focus on the mass may be seen as part of the “sacramentalisering van de vroomheid”, described by Clemens, designed to answer the Jansenists and their concentration on the sacraments. It certainly encompassed a ritualization which was already an integral part of devotional practices since the Late Middle Ages. Apart from that, Jansenism seemed to have little impact on the praxis pietatis of ordinary Catholics (Clemens 1988, p. 165, see also Martin 2016, sct. 18–19).

The focus on the Passion and the Cross was not exclusively practiced at mass, but was also, in a general sense, a prominent part of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century devotion. It was a basic disposition for any devout Catholic, expressed in the devotions to the suffering Christ, such as the Passionals, the Five Sacred Wounds, the Passion Clock, the Way of the Cross, and the Passion rosary. Such devotions were practiced everywhere, and they materialized in chapters, books, or leaflets, creating a considerable body of ascetic literature. The wish to relive the Passion was a constant and fundamental feature of seventeenth-century spirituality, the faithful happily sharing the suffering of Christ (see Chédozeau 1996, p. 214) (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Het Gulden Paradys, ofte christelyk hand-boekxken, Gent, Jan Meyer (1761) (Anonymous 1761/1762), Christ prays for his enemies, woodcut copies of the suite by Le Clerc. RG 3096 B11.

In 1608, for instance, Pinelli suggested a devotion to the Five Sacred Wounds as preparation for mass. One should enter the church and then go before the crucifix and pray an Our Father and add a prescribed petition for each of the wounds.70 Indeed, in his preface to the readers of Tableaux de la croix, 1651, Mazot seemed to suggest a combination of two already existing practices, the mass and devotions to the suffering Christ, when he presented the book as a “collection of devout meditations on the Passion, applied to the holy sacrifice of the mass”.71 In 1678, the Dominican Father Carl Myleman, (c.1608–1688), described various ways to honor the suffering Christ. Among others, there were some “who in their chamber or house have hung seven images in honor of the seven stations where Christ has suffered the most (…) and greet these daily on their knees with an Our Father and a Hail Mary”.72 Prayers for such a devotion, then, were offered by a small booklet, Cabinet der devotien, or, by Myleman himself, in his book on the Passion, 1686.73 This practice, and others using imagery, were exactly what the Jesuit Father Augustin van Teylingen (1587–1669) had suggested in 1630 (van Teylingen 1630, pp. 244–45). While spiritual prayer in the “chamber of our heart” may have been considered superior to those depending on material means or fixed devotions, such instruments effectively supported prayer itself as the one essential practice (see Choné 2000, pp. 577–92). Thus, the mass books or texts provided most useful spiritual reading outside the mass as well, some of the books explicitly suggesting that the explanations should rather be read outside mass, be it at home or in the church.74

In his Regel der Volmaecktheyt from 1650, the Dominican Father Johannes de Lixbona, (c. 1600–1670), suggested that the devout might go to the church to meditate on the presence of God or on the Passion of Christ. If possible, one should even attend mass spiritually twice a day, to meditate on the Passion following the ordo, and to read the hours and the rosary.75 Such praxis pietatis was well served by the mass books or mass-related texts in the devotional books, covering the double setting that characterized devotional life, just as it had been characterized since the Late Middle Ages, where devotional practices took place in public spaces, often in churches, thereby gaining a collective, quasi-liturgical, character as shown by Eamon Duffy (2006, pp. 53–64).76 Acts of piety, including mass attendance, were increasingly performed communaly (Châtellier 1991, p. 149). In 1674, the Jesuit Father Andrien Parvilliers, (1619–1678), assumed that those practicing the “Way of the Cross” did so in “churches chapels, oratories, or other such places”(Parvilliers [1674] 1729, p. 12). It was private prayer, yet often including the entire household. Ideally, at least, the house became an oratory (de Viguerie 1996, p. 101). A late eighteenth century prayerbook, Godvruchtig gebede-boeksken (Anonymous 1790), admonished the faithful:

“Everybody must take care that a place for prayer is suitably decorated and as much as possible separated from the other places [in the house]. In such places one shall have a crucifix and an image of the Most Holy Virgin, be it a painting or a print. If one does not have a separate space, one should use an altar or small chapel somewhere else. (…) Daily, one should also in such places of prayer attend mass spiritually”.

Attending mass spiritually, including spiritual communion, “communier par le desir du Coeur” (Tourneux), was nothing new, but well known from late medieval spirituality. It was described in the Catechism of Trent as those who “inflamed with a lively faith, which works by charity, participate in desire of this celestial food”.78 Therefore, “to receive in one’s soul the virtue and grace of the most holy sacrament” continued to be part of a devout life in the post-Tridentine era.79 The unassuming prayerbook we have just quoted considered this a proper daily spiritual morning exercise:

“As it is quite certain that the holy mass sacrifice will always be celebrated in some Catholic church every morning, anybody who has no opportunity to attend mass, due to sickness or lack of a priest, can spend half an hour in their space dedicated for prayer, if they do not have opportunity to go to the church”.

During such spiritual attendance, the devout would need a book like our mass books, as it says explicitly in the book, to hear mass spiritually “as it is shown here above”, referring to how to attend when there is no priest or if one is sick.81 An eighteenth century booklet with primitive woodcuts, seemingly a simplified version of van der Kruyssen’s Misse, haer korte uytlegginge, has the following prayer to be said as the priest communicates at the altar, “I ask you, make me capable of preparing my heart with a true love in such a way that it may become a worthy dwelling for you and the holy Trinity”.82 Since Baroque interest in the Eucharist resulted in a devotional approach, rather than more frequent reception of communion, such a prayer was equally suited to spiritual communion, since personal application was no less possible if the mass was attended spiritually. Both inside and outside mass, the mass books intended to foster devout participation in which spiritual communion was often an important part. “Going in the spirit to the altar of God”, as Godvruchtig gebede-boeksken (Anonymous 1790) called it, was an important pious practice and would, of course, demand precisely our kind of books, and, if illustrated, they would make the “attendance” even more real, supporting the imagination of the devout and providing an almost “virtual mass”. In 1697, having described four different aspects of mass, none of them as a devotional exercise, Julien Loriot stated that there were “other ways to attend (d’assister) mass profitably and usefully, “like following the priest in the words and acts of this sacrifice”, but he would say nothing of these, “since there were several small devotional books explaining them”.83

9. The Two Ways of Attending Mass

As we have seen, to the Council of Trent the active participation of lay people in the mystery of the mass sacrifice was most essential. As a mystery, and in the celebration among the faithful, its accessibility did not depend on intellectual reflection, but rather on devout participation, responding to the passion with compassion—in the tradition of devotio moderna. Moreover, the prohibition of 1661 against the translations of the ordo, hit texts like the one that van der Kruyssen had added to the illustrated devotion to the suffering Christ. While not enforced with any vigor, it still presented the mass books with a problem which the Jesuits solved by presenting two ways of attending mass, or rather, two ways of using the mass books. The mass was no purely spiritual matter, and to preserve the material aspect of the mass, in both cases the devotional dimension was configured to the liturgical activity of the celebrant. One way was a sequence of prayers during the mass concentrating on the words of the priest, the other a devotion to the suffering Christ aligned with the progress of the liturgy. In Het Kleyn Paradys, for instance, the first is “Prayers during the mass”; the other was “Another way of piously attending mass by meditating on the suffering of Christ which is rendered through the ceremonies of the mass”.84 Perhaps we might, with Chédozeau, call one the ‘literal’ way, and the other the ‘spiritual’ way.

The first way to attend the mass was to join the priest and the prayers of the liturgy. It was regarded the better way since it aligned itself more directly with the liturgy as “le Sacrifice commun du Prêtre & des Fidelles” where the Church “méle la voix des assistans avec celle du Prétre”. In 1680, in De la meilleure maniere d’entendre la sainte messe, Nicolas Tourneux referred to another Jesuit, Alonso Rodriguez, (1538–1616), in presenting three of the various kinds of devotions during mass, namely “s’occuper de la Passion de Jesus-Christ”, “d’offrir & de sacrifier avec le Prétre”, and “de communier au moins spirituellement pendant que le Prestre communie”, agreeing with Rodriguez that the two last were the better. This certainly did not mean, however, that alignment with the Passion was less proper. “The mass is the representation of the sacrifice of the Cross, and there Jesus Christ wishes that one commemorates his death. Therefore, he who does not think of the death of Jesus Christ at all, does not attend the mass the way Jesus Christ wants him to attend it”.85 It was best to follow the priest closely, Father Adrian van Loo advised in 1713, avoiding distraction by reading no prayers other than those suited to each part of the mass.86 His point was that proper attendance was to focus on the liturgy, and thereby the Passion of Christ. The mass books should serve nothing but focus and devotion. The people in the pews were instructed to imagine two celebrants at work during the mass, Christ and the Priest who emulated him, or rather only one, who was Christ himself.87 To follow what was going on attentively made sense, since the two illustrated events were not only happening at the same time through remembrance, but were also two dimensions of the one and same event. Since the priest was not only acting in persona Christi, but as a visible imago Christi, the actual and spiritual presence came together as dimensions of time when the past was transported into the liturgical present.88 Therefore, the faithful should, Nicolas Tourneux stated, again referring to Rodriguez, “attach themselves attentively to everything the priest says or does, and at his side on their part, then, as much as possible do and say the same things”.89 In 1710, another Jesuit, Nicolas Sanadon, (1651–1720), spoke of this as the usual method “consisting of a great number of [devotional] acts conformed to the prayers and actions of the priest”.90 Apart from such mass books, there were other books to use for those wishing to follow the changing texts even closer, like the various editions of Tourneux’s L’Année chrétienne, 1682. The devout could do nothing better than read the collect prayers with the priest, “for all parts of the year these prayers may be found in various good mass books”, van Loo told the readers; the epistles were found in the small books called “Epistles and Gospels”, “in which one may also find the collects for the entire year” (Le Tourneux 1713, Voor-reden by van Loo, sct. V and VI). The attention to the actions of the celebrant and their immense significance, was also a move against the rejection of the sacramental priesthood by Protestants (Jungmann [1948] 1952, p. 188). Therefore, the role of the priest was the exclusive focus, the people, then, admonished to join his actions and words, participatorily watching the mysteries unfold (see Hache 2017, sct. 2). The devout should pray, Bonnefons suggested, “I offer you, my God, all the words spoken by the priest as if said with my (own) mouth”.91 This focus on the priest did not so much express clericalization, but primarily an effort to keep the devotional aspect of mass united to the liturgy.

Another way of attending mass, the spiritual or devotional way, was preoccupied with creating a communion of senses and devotions, a spiritual engagement in the unfolding of the mystery which they attended. Moreover, it served as a defense against Protestant, and later Jansenist, critique of the inaccessibility of mass for lay people. How the devotional way of attending mass was meant to work was illustrated most instructively in 1743, by a self-explanatory commentary in Het Kleyn Paradys, ofte Christelyk handboeksken. The commentary introduced the common “other way of attending mass”, and deserves to be rendered in extenso:

“We have presented a mass, decorated by small devout printed images showing the mysteries of the suffering Christ, which are signified by the vestments of the priest and the outward ceremonies, that the faithful themselves simply by looking at these small pictures internally should be mindful of what the priest does at the altar, what mysteries he visualizes, that they may thus receive a livelier impression of all parts of the suffering of Christ. The prayers and meditations attached show how they may ask for the fruits of the mysteries. Yet, since these may sometimes be too long, people can skip the meditations during mass and use them if one wants to meditate on the holy suffering of Christ”. Figure 9. Wilhelmus Nakatenus: Hemels Palmhof beplant met godtvruchtige oeffeningen, Antwerp, (Nakatenus [1662] 1683). With her flaming heart, the woman embodies devout attendance. Engraving in RG 3046 B9.

Figure 9. Wilhelmus Nakatenus: Hemels Palmhof beplant met godtvruchtige oeffeningen, Antwerp, (Nakatenus [1662] 1683). With her flaming heart, the woman embodies devout attendance. Engraving in RG 3046 B9.

The various dimensions of the mass and of the categories of religious practice merged, as individual devotion to the suffering Christ was combined with the formal structure of mass liturgy for the collective to create a devotional practice which was simultaneously individual and collective, emotional and regulated, meditative and participatory.

We may regard this ‘other way’ as the more popular method, more devotional in its character, the illustrations echoing the Ignatian composition of place (Chédozeau 1996, p. 216). As a spiritual pilgrimage, the faithful were present in the Garden of Gethsemane, in the Praetorium, on Calvary, etc., indeed, going to church was like going to Bethlehem or climbing Calvary.93 The difference from the spiritual pilgrimage, was, however, that by attending the mass, the events and places were much more actually and immediately present. The mass was no image or memory of the original sacrifice, but that very sacrifice itself, Andries told his readers in Het ander gheduurigh kruys.94 Thus, ‘the other way’ was to use the liturgy as a vehicle for meditating on the Passion. This second way was usually the one illustrated, often including descriptions of the actions of the priest, which may indicate that the illustrations, verbal or visual, were meant for a less sophisticated audience. Undoubtedly, “the other way” of hearing the mass was more immediately based on the allegorical interpretation of the ceremony and more intimately related to existing devotions. In that perspective, it is interesting what Ronald Surtz pointed out, fifty years ago, that already in the time of Amalarius it was remarked that the allegorical interpretation of the liturgy appealed particularly to the simpliciores, the unlearned, because it provided a sense of imaginative participation in the mass (Surtz 1982, p. 228). Such vivid imagination, promoted by ekphrastic descriptions and imagery alike, particularly marked “the other way” of attending mass.

Any mass attendance would, however, have a strong element of devotion to the suffering Christ. In abandoning a literal translation of the ordo and inviting the faithful to share simultaneously in both dimensions of the one sacrifice, one tends to agree with Chédozeau that the second way of attending mass was the one where the sense of the celebration was better captured, or, perhaps, the spirit of the mass better translated into active participation, than by following the words of the ordo (see Chédozeau 1996, p. 217). In 1620, a Dutch translation of Pinelli, De chracht ende misterie de H. Misse, found that to contemplate and follow the ceremony and everything the priest does was inferior to remembering all that the Lord has done for us and to contemplate God himself.95 To a certain extent, the devotional or spiritual approach did that, rather than the more literal. Thus, Maria Hérnandez was certainly right in regarding mass attendance as a devotional practice, yet wrong in disregarding the repeatedly expressed ideal of “interior attentiveness”, and its external, behavioral, shape, as she seemingly reduced the endeavors of the faithful of the post-Tridentine era to acquire and master a certain repertoire of religious gestures expressing their proper mass attendance (Hérnandez 2019, p. 127).

10. Reading Mass Books

The mass books for lay people were not only a kind of lay missal, but as we have seen, they could be used outside mass as well, to understand the mass better, to learn its structure, and to recognize the liturgical stages and their correspondent scenes from the Passion narrative. In this respect, the mass books might serve as preparation for mass, accompany the faithful during mass, and, obviously, guide spiritual mass attendance following the mass sacrifice. They transported the devout to the Passion of Christ, applied it to their personal lives to imitate the Savior and to address him fervently. In the same way as devotions, devotional literature both formed and expressed faith.

In 1722, the introduction in a devotional book, Sainte messe ou ordinaire de la messe, rendering the entire ordo in Latin and French as “Sainte Offices de l’Eglise et pratiques de pieté”, offered several reasons for illustrating the ordo: to support the memory; to create the proper emotional responses; and to be practical instruments for those with a poor view of the altar, or those absent, that they may attend mass more efficiently, attentively, and piously:

“In this book one has wanted to collect those prayers which are most in use among the faithful, and which are best suited to nourish their piety. What constitutes the main part is the Mass ordo in Latin and French. One has decorated it with prints that show the different actions of the priest, and the situations of the mysteries in which memory one especially celebrates [offre] the holy sacrifice. The images are thought to be a help to those attending [mass], to call forward the memory of the mysteries, and to awaken feelings of love and gratitude towards Jesus Christ. They could also be useful for those who are placed with the altar out of sight, to make it easier for them to follow the priest and to unite themselves with him in this sacrifice, which is theirs with him. These prints are even more useful for those who, through sickness or any other reason, are prevented from being among the gathering of the faithful, and who nevertheless engage in the pious practice of taking some time to unite at a distance with masses being celebrated. At least they would in these pictures see what happens at the altar, that which could give their attention more life and their prayers more fervour”.

The complex phenomenon of such books was not accessed through reading alone, but through the convergence of received instruction, socialized knowledge, images, texts, and liturgy into one devotional experience, the “choses exterieures & sensibles” indistinguishable from their imprint “dans l’esprit des plus pauvres & des plus ignorans” (Olier [1657] 1661, pp. 15–16). As devotional instruments, they were useful in various settings, including educational ones. A wide range of purposes was mentioned by Andries promoting his book Het ghedurigh cruys ofte Passie Jesu Christi, published in 1649, “O, lover of the continuously-crucified Saviour, here you have a nice opportunity to promote his honour and love, not just in the household, but also in the churches, inns, and monasteries, in ships, schools for the poor; in villages: for the lord pastors, those who receive religious instruction, etc.”.97 Even if the mass books meant for mass, they were also devotional books to be used outside the mass, and in addition they were also expedient educational tools during catechesis and missions, not least when illustrated. This additional use, mentioned explicitly in 1649, was repeated almost a hundred years later in the introduction to the reader in Het Kleyn Paradys (Anonymous 1743):

“Images are the books of the ignorant the holy fathers say. Therefore, these small images could also profitably serve the instruction of children from a young age, before they can read, about the mysteries of Holy Mass and the suffering of the Saviour; as well as for sick people and others that they may with one look and without much headache bring the devout matters before their eyes, that can help them to attend mass in the spirit and to join all their suffering with the suffering Jesus”. Figure 10. Woodcut on the title page of Het gulden Paradys, Gent 1770. RG 3096 B8 (Anonymous 1761/1762).

Figure 10. Woodcut on the title page of Het gulden Paradys, Gent 1770. RG 3096 B8 (Anonymous 1761/1762).

If the spirituality of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century mass attendance as a kind of practical theology is revealed in the books presenting the mass or various other devotions, the general literacy needed for such printed material to make an impact is of interest. While it is clear that some of the devotional books assumed a certain status of its readers, relatively recent research has shown that in the centuries treated here, reading was more widespread than earlier notions of common illiteracy among ordinary people, let alone peasants, would have it. An important part of religious literacy would have been hymns and songs, which seem to have played an integral part in the devotional life outside mass. In Protestant services, however, congregational song was from the very start an important feature. In the German-speaking areas, some hymnals were explicitly meant to accommodate re-catholicized people who had grown fond of devout singing, though such collections were seldom used specifically at mass.99 Even when verses do appear in some of the mass book editions, they probably functioned more like familiar prayers, rather than being meant to be sung collectively. In the preface to the reader, a Catholic hymnal published in 1587, Het prieelken der gheestlycker wellusten, the verses were explicitly said to be read or sung.100 In 1675, however, Catholic congregations might have sung the following verse at the beginning of the mass: “The mass shows us the death of Christ/That he suffered for our great sins/Oh, Soul, learn here at the altar of God/All that the Son of God suffered on Calvary”.101

If not exclusively, reading would largely have been for religious edification and education. In this article, we cannot delve into the considerable amount of recent research on literacy in Europe, but there is ‘literacy’ as such, the ability to read a book, and then how the content of books was spread. Those who could not read did not depend on literacy to share the spirituality of devout mass attendance. Assigning a participatory role for the rosary at mass, the Dominican Johannes de Lixbona, related the various parts of the mass to the mysteries of the rosary (de Lixbona [1662] 1673, pp. 72–98; [1647] 1693, pp. 100, 104 and 106):

“Praying your rosary during Mass (…) shall not greatly hinder the way of attending Mass and the exercises, given above, on the condition that, during your prayer, you still follow the mysteries and exercises of the Mass, and while praying your rosary, you ask Mary that she may obtain from her Son for you the attention and disposition which the mysteries and exercises of Mass deserve”.