2. An Iconography of Suffering

While later medieval depictions tend to focus on the suffering, this is not to say however that the earlier medieval period shunned any and all reference to the violence of Christ’s bloodshed and sacrifice. Celia Chazelle has demonstrated that contemplation of Christ’s suffering and bloodshed was a feature of Carolingian piety and literature. Likewise, Salvador Ryan cautions that the cross as wholly a symbol of Christian triumph should not be taken too far as early medieval poetry in Ireland would suggest that the cross could be accepted simultaneously as both a symbol of triumph and torture (

Chazelle 2001, pp. 23–24;

Ryan 2012, p. 83).

Elements of an iconography of pity and suffering are found in the twelfth century in Ireland. Jenifer Ní Ghrádaigh has argued for a more expressive trend in the sculpture of some of the Romanesque crosses, particularly those at Dysert O’Dea and Inis Cealtra in Co. Clare, citing the twelfth-century spirit of reform as context and potential influence from the cultic image of the

Volto Santo, and from Ottonian crosses, at least one of which may have been housed at Christ Church Cathedral in Dublin (

Ní Ghrádaigh 2013).

4 The head of Christ from Inis Cealtra for example is sombre rather than victorious, and on the Market Cross from Glendalough the head wilts to the side. By the fifteenth century the expression of torment became considerably more intense. The crown of thorns, emaciated frame, and disquieting mixed viewpoints—frontal for the torso and profile for the legs—of the Christ in the

Leabhar Breac (

Speckled Book), Dublin, Royal Irish Academy MS 23 P 16, p166, 1408–1411 (

Figure 3), present a poignant image of suffering. Others, such as the crucifixion plaque from Fertagh, Co. Kilkenny, c.1530s (

Figure 4), offer a more frightening and contorted view of agony.

The power of the symbol of the cross is highlighted in the account of the Passion of Longinus in the

Leabhar Breac. Longinus questions a group of demons about why they chose to inhabit pagan idols and the response he receives claims that they ‘found the stone images […] without the sign of the cross on them, and without being named in the name of God […] for where Christ is not honoured, nor the sign of the cross, there is [their] dwelling forever’ (

Passions and the Homilies from the Leabhar Breac, p. 302). That said, while the cross and crucifixion may be central to Christian doctrine and the idea of salvation, the gospels themselves provide minimal information about the event itself and how the crucifixion took place. The gospel accounts describe aspects of the arrest, trial, death, burial, and humiliation, but none describe the cross itself or the manner in which he was suspended on it. The entire procedure is conveyed in a single word ‘

crucifixerunt’ (‘they crucified him’), but as historical sources and archaeological evidence suggest the methods of crucifixion were considerably varied. Artists and writers have therefore sought inspiration from a range of sources including patristic exegesis, Old Testament texts and prophecies, the Psalms, the lamentations of Jeremiah, and perhaps local laws and customs. The emaciation of Christ’s body so often found in images of the crucifixion, such as on the Shrine of St Caillin, 1536, or a tomb chest in Holycross Abbey, Co. Tipperary (

Figure 5) from the second half of the fifteenth century, is derived from Psalm 21 (Vulgate 22). A sermon of St Bernard on the Passion interprets ‘I can count all of my bones’ (Psalm 21:[22]:17) to mean that Christ was stretched taut on the cross revealing his ribcage (

Merback 1999, p. 69 and chp. 6;

Pickering 1980, p. 6;

Jensen 2017, pp. 6–7;

Viladesau 2006, pp. 115–18).

Irish scenes of the crucifixion make use of both the Latin cross as in the Tomb of Edmund Archer and his Wife, Thurles, Co. Tipperary, c.1520 (

Figure 6), and on the mid fifteenth-century heraldic shield of Dionysius O Congail at Holycross Abbey, Co. Tipperary, and the tau cross as on the Tomb of Sir Walter Bermingham (†1548) in Dunfierth, Co. Kildare. Often, as in the

Leabhar Breac miniature (

Figure 3), a tomb slab from Inistioge, Co. Kilkenny, from the second half of the fifteenth century (

Figure 7), and a tomb chest in Holycross Abbey (

Figure 5), the terminals of the

patibulum (crossbeam) are enlarged and draw further attention to the wounds in the hands. The form of the

stipes (vertical beam) of the cross may also bend to accommodate the twisted body of Christ as on the Fertagh crucifixion plaque (

Figure 4) or the Shrine of the Book of Dimma, which was refurbished c.1380–1407 (

Figure 8). The cross may also be absent from the scene altogether, though typically this only appears on shrines where the overall form of the object stands for the cross, as in, for example, the Domnach Airgid refurbished c.1350 and again in the fifteenth century (

Figure 9), or the Shrine of the Miosach reworked in 1534, though true also of the James MacDonnell Chalice, 1596. While the

titulus board may have been one of the most common features of medieval European crucifixion iconography, it appears very infrequently in Irish examples, the exceptions being the Cornelius O’Sullivan Chalice, 1597, the tomb of Bishop Walter Wellesley, formerly at Great Connell and now at St Brigid’s Cathedral, Kildare, c.1539 (

Figure 10), the Lismullin Wayside Cross from Skreen, Co. Meath, c.1588, and the Arodstown Wayside Cross, now found at the parish church of Moynalvey, Co. Meath, c.1590 (

Figure 11). The

suppedaneum or

sedile (footrest or small seat) is rarely included, but sometimes Christ’s feet appear to be resting on a set of steps, as on the twelfth- to fourteenth-century Cross of Clogher, or propped up by an angel, as on the late fifteenth- or early sixteenth-century indulgence slab in St Brigid’s Cathedral, Co. Kildare (

Figure 12). Such supports were designed to prolong the suffering and lengthen the time taken to die rather than offer relief to the dying and so when incorporated into the scene, serve to heighten the sense of suffering (

Jensen 2017, p. 10).

In some cases, more typically on metalwork, the cross appears as a tree such as on the Bell Shrine of St Conall Cael reworked in the fifteenth century, or with foliate detailing as on the double-head slab at the Cathedral of St Patrick in Trim, c.1325–1350 (

Figure 13), a fragment in Kilcormac, Co. Offaly (

Figure 14), which may have been part of a sixteenth-century tomb chest, or a late fifteenth-century pendant cross in the National Museum of Ireland.

5 Processional and altar crosses in particular are notable for their floriated outlines such as the Ballymacasey Cross, c.1479 (

Figure 15), Sligo Friary Cross, c.1450 (

Figure 16), and Sheephouse Cross, c.1450 (

Figure 17). Colum Hourihane commented that this is a frequent form for processional crosses in late medieval Ireland and, while also popular in Britain from the opening decades of the fifteenth century, it is not found with the same frequency elsewhere (

Hourihane 2000, p. 34). This motif of the

lignum vitae (wood of life) is identified with the tree of life, which had its origin at Creation (Genesis 2:9). The identity of the

lignum vitae was, however, multifaceted and was also associated with the water of life (Revelation 22:1–3) and the cross of crucifixion. St Bonaventure’s influential mid thirteenth-century treatise,

Lignum Vitae, clearly identifies Christ with the tree of life (

O’Reilly 2019, pp. 343–50). The text acts as an aid to contemplation on the suffering and glorification of Christ. Diagrams based on the

lignum vitae quickly spread throughout Europe. A late thirteenth- or fourteenth-century example from Durham, London, British Library Harley MS 5234, f5v (

Figure 18), shows Christ crucified on a tree sprouting twelve branches. The branches are labelled with stages of the Passion and at the end of each branch, the leaves or ‘fruits’ of the tree represent the virtues. At the top, the pelican, a symbol of Christ, wounds herself so that her young may feed from her blood. The motif of the cross of crucifixion as a fruit-bearing tree or an arbour also occurs in contemporary Irish bardic poetry.

6 Diarmuid Ó Cobhthaigh, for instance, regards the cross as ‘the great sheltering tree’ on which Christ shed blood. An anonymous poem, ‘A fruitful tree is the Lord’s cross,’ likely composed in honour of the shrine of the true cross at Holy Cross Abbey, Co. Tipperary, describes the cross as both ‘our saving herb, our flower of blessing, our bond of perfect peace’ and ‘tree of salvation’, which ‘heals the world and can save both body and soul’ but also as the ‘torture-tree’ (

Aithdioghluim Dána, poem 67, stanza 25, and poem 88, stanzas 9, 26a, and 28;

Ryan 2012, p. 102).

Despite the traditional representation of nails as instruments of the Passion, none of the gospel accounts actually describe Jesus as nailed to the cross. The story of Doubting Thomas is the first mention of nails when he asks to see the ‘mark of the nails in his hands’ (John 20:25). This may have been a mistranslation for ‘wrists’

7, but it is also possible that Jesus was both nailed and tied to the cross. It was both more common and more practical for Romans to bind the arms of the person being crucified to the crossbeam with ropes and then nail or bind the feet afterwards (

Jensen 2017, pp. 7, 10). An example of this can be found in a French manuscript illumination from c.1500, New York, Morgan Library MS H 5, f57r, where soldiers both bind and nail Christ’s feet to the cross. In an early medieval Irish context, the eighth-century

Irish Gospels of St Gall, Saint Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek MS 51, p. 266, show Christ bound to the cross with elaborately stylised ropes. That this tradition continued into the later period is demonstrated in a poem attributed to Donnchadh Mór Ó Dálaigh (†1244) when he writes that ‘God’s son was bound on that tree—divine suffering!’ (To a crucifix, p. 252).

As has already been mentioned, however, the prevailing theory of atonement in medieval theology held that Christ saved mankind through self-sacrifice, shedding his own blood to wash away the sins of the world. That this tradition was held in Ireland is clearly demonstrated in contemporary bardic poetry, as one poet writes: ‘a man like me can not repay Thee for the blood Thou didst shed for my sins.’ Following this, medieval theology demanded that nails rather than ropes bound Christ to the cross as only nails could produce the necessary blood loss. As such, nails became an inexpungable element of the iconography of the crucifixion (

Aithdioghluim Dána, poem 92, stanza 25;

Merback 1999, p. 74). Depictions of the crucifixion in Ireland prior to c.1200 typically show the body of Christ as pierced by four nails with the feet placed in parallel and nailed individually as in the twelfth-century High Cross at Dysert O’Dea, Co. Clare, or on the late eleventh- or twelfth-century Kells crucifixion plaque now in the British Museum.

8 The arrival of the Gothic style in the thirteenth century brought about a change in the iconography, preferring a single nail through both feet as on the

Domnach Airgid (

Figure 9), the Sheephouse processional cross (

Figure 17), or the fourteenth- or fifteenth-century Shrine of St Patrick’s Tooth. This imagery is also found in the Irish literature of the later period. That three nails were used rather than four is precisely stated by Tadhg Óg Ó hUiginn (†1448): ‘Of [the third of Christ’s fifteen sorrows] I shall mention the four wounds of the three nails, the wounds in His feet and hands, wounds heavy with torture.’ Likewise, Diarmuid Ó Cobhthaigh describes Christ as ‘lifted up on three nails’ (

Aithdioghluim Dána, poem 78, stanza 13, and poem 64, stanzas 5–6).

Liturgical changes and the emphasis of physical suffering and torture in Passion texts of the thirteenth century are generally thought to have been instrumental in the change in iconography. The

Meditationes Vitae Christi, for example, stress that ‘He is so tortured that He can move nothing except His head. Those three nails sustain the whole weight of His body. He bears the bitterest pain and is affected beyond anything that can possibly be said or thought.’ It has also been suggested that the emphasis on physical pain in the Passion texts was reflective of the revival and spread of judicial torture between 1150 and 1250 (

Meditations on the Life of Christ, p. 334;

Bestul 1996, pp. 153–64).

The majority of fourteenth- and fifteenth-century images of the crucifixion typically present the hands of Christ as outstretched and frequently considerably enlarged to draw the eye to the wounds, as on the Tomb of Walter Brenach and Katherine Poher in Jerpoint Abbey, c.1501 (

Figure 19), the tomb of Archbishop Tregury in St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin, c.1471 (

Figure 20), and a carving of the crucifixion at Ballinacarriga Castle, Co. Cork, c.1585. In contrast, the feet are generally afforded less importance, and frequently the lower section of the body is depicted as disproportionately small in comparison to the upper section. The proportions are especially distorted on the sixteenth-century Purcell tomb surround in St John’s, Co. Kilkenny (

Figure 21), and the Soldierstown Cross, c.1480–1490. Typically the legs appear bent to Christ’s right or straight down beneath the torso. The right foot is placed across the left and a single nail pierces both. Some variety appears in the iconography: the legs on the Fertagh crucifixion plaque (

Figure 4) are crossed twice, once at the knees and then again at the ankles. Occasionally the left foot is crossed in front of the right as in the

Leabhar Breac miniature (

Figure 3), the indulgence slab in St Brigid’s, Co. Kildare (

Figure 12), and the double-head slab in the Cathedral of St Patrick in Trim, Co. Meath (

Figure 13). The feet may also sit parallel pierced with two nails such as on the Turlough Cross, c.1470–1480, and the early sixteenth-century image of the Trinity originally from a tomb sculpture in the Augustinian House of the Holy Trinity, Ballyboggan, now at the Church of the Assumption in Ballynabrackey, Co. Meath (

Figure 22).

In comparison to some of the more gory and graphic representations from Northern Europe, late medieval Irish depictions of the crucifixion tend to be more reserved in their depiction of blood and horror, though this may be due, in part at least, to the surviving media. The Ballymacasey Cross (

Figure 15) depicts droplets of blood in the palms of the hands. While not strictly a crucifixion scene, a miniature in the

Seanchas Burcach (

History of the Burkes), Dublin, Trinity College MS 1440, f18v, c.1570 (

Figure 23a), of Christ carrying the cross is an unusually gruesome image in an Irish context. The scene shows blood streaming down Christ’s face from the wounds of the crown of thorns and the cross itself is already heavily bloodstained in a foreshadowing of the event. The European influence on the artist of the

Seanchas Burcach miniatures has, however, been widely noted. Françoise Henry and Genviève Marsh-Micheli noted the influence from German woodcuts as ‘[l]ike them, they are gaudy and violently realistic’, and Bernadette Cunningham noted stylistic associations with wall paintings from Pickering in Yorkshire and stained glass from Long Melford in Suffolk (

Henry and Marsh-Micheli 1987, 810;

Cunningham 2015, p. 425;

2006, p. 21n).

Devotion to the five wounds of Christ emerged in Ireland at least as early as the late thirteenth century. A tomb in St Canice’s Cathedral, Co. Kilkenny, believed to be that of Bishop Hugh de Mapilton (1251–1260) or Bishop Geffrey St Ledger (1260–1287) is ornamented with a scene of the five wounds. Frequent appearances of the motif in bardic poetry attests to the developing cult during the fifteenth century. Tadhg Ó hUiginn writes of a ‘burning affliction’ as ‘the depth of his wounds, the bursting of His breast, the splitting of His feet’s white skin and His hand’s reddened palms.’ Philip Bocht Ó hUiginn (†1478) elaborates on the tortured body of Christ to consider ‘the dislocation of his limbs’ and how ‘the bursting of His sinews could be heard.’

9 Máire Ní Mháille’s early sixteenth-century

Book of Piety, Dublin, Royal Irish Academy MS 24 P 25, contains fifteen prayers of meditation on the fifteen pains of Christ’s Passion (

Aithdioghluim Dána, poem 78, stanzas 24;

Philip Bocht Ó hUiginn, poem 3, stanza 15;

Cunningham 2006, p. 22;

Ryan 2006, p. 7;

Ryan 2016, especially pp. 296–300;

Connaughton 2012, pp. 154–55). These prayers follow in the tradition of the Fifteen Oes, which became popular in late medieval England and Europe and were closely associated with the wounds of Christ. The popularity of this devotion is in part due to the extravagant indulgences associated with it, offering remission of 32,755 years in Purgatory in return for the recitation of five

Pater Nosters, five

Ave Marias, and a Creed before the image (

Duffy [1992] 2005, p. 214). The perceived power of this particular devotion in the earthly realm, however, was also highly valued, and this is perhaps best illustrated in a contemporary account of the battle of Knockdoe in 1504. In preparation for battle against the O’Briens and MacWilliam Burkes, Gerald FitzGerald, Earl of Kildare requested the chancellor of St Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin to sing the mass of the five wounds ‘successively for his godspeed.’ Sometime later, Ellen, the daughter of MacWilliam Burke, requested a monk to likewise sing the mass of the five wounds successively in order to ensure victory for her side. As the monk sang his mass, however, an angel appeared to him stating that the petition had already been granted to the Earl of Kildare. Six days later, Kildare was victorious at Knockdoe (London, British Library, MS Add 40674, f. 54v;

Flower 1931, p. 326;

O’Carroll 2004, p. 53).

Given the power of the devotion to the five wounds, and the insistence in the literature of the power of Christ’s blood in the remission of sins, it is notable that the wound in the side appears relatively infrequently in Irish art of the period. The Creagh tomb in the Franciscan friary in Ennis, c.1470–1480 (

Figure 24), for example, incorporates the moment of spearing in the scene of crucifixion,

10 angels on the indulgence slab in Kildare (

Figure 12) collect the blood flowing from the side and hand wounds in cups, and two processional crosses, those from Sligo Friary (

Figure 16) and Multyfarnham Friary, c.1480–1490, both depict the side wound, but by and large this wound is absent in Irish depictions. This is a further demonstration of the restraint on behalf of Irish artists described above. While violent imagery was present in contemporary bardic poetry—vividly describing the excruciating torment and enumerating each individual wound, ‘On God, Mary’s son were sixteen wounds and six hundreds and fifty-six thousand’—visual artists preferred a more introverted and devotional representation of pain and suffering (

Aithdioghluim Dána, poem 78, stanza 26).

Earlier Irish representations of the crucifixion such as that on the Romanesque cross at Moinancha, Co. Tipperary and the Clonmacnoise Crucifixion Plaque (

Figure 2) depicted Christ fully dressed in a long perizonium. In the later period this gave way to a much shorter garment and ultimately the loincloth. The figures of Christ on the Shrine of the

Domnach Airgid (

Figure 9) and in Kilcooley Abbey, Co. Tipperary (

Figure 25) from the fifteenth century, for example, wear their loincloths past their knees. The figures of Christ on a late fifteenth-century tomb chest at the Augustinian Priory at Mohel, Co. Waterford, Ballinacarriga Castle, Co. Cork, and at the Carmelite Priory in Kildare from the sixteenth century (

Figure 26), on the other hand, wear a much shorter garment. From a theological perspective, the shorter garment signifies the humiliation of Christ during the Passion. A passage in the

Meditationes Vitae Christi states that when Christ was stripped of his clothing that the Virgin was filled with sorrow at his shame and nakedness and ran to cover him with her veil. This passage is retained in Nicholas Love’s fifteenth-century English language translation,

The Mirrour of the Blessed Lyf of Jesu Christ, and in the

Smaointe Beatha Chriost, the first Irish language version of the

Meditationes Vitae Christi, translated c.1450 by Tomas Gruamdha O Bruachain. The Virgin’s actions are also recorded in a similar manner in the

Dialogus Beatae Mariae et Anselmi de Passione Domini, which was circulating in translation in Irish by the fourteenth century (

Meditations on the Supper of Our Lord, p. 20; Nicholas Love, p. 237;

Smaointe Beatha Chriost;

Connaughton 2012, p. 83;

Skerrett 1966, p. 163).

From an artistic perspective, the loincloth afforded artists a greater opportunity to convey the suffering of Christ through the wounds, blood, and the emaciation of the frame. The loincloths themselves present a great variety of styles in terms of the length, the folds, the drape, and the type of knotting. One particular style roughly localised in the Ormond area does, however, stand out. Monuments belonging to both the Ormond and O’Tunney groups

11 including the Tomb of Walter Brenach and Katherine Poher in Jerpoint Abbey (

Figure 19); the Purcell Tomb Surround in St John’s Priory (

Figure 21); and the Tombs of John Grace c.1552 (

Figure 27), and Piers and Margaret Butler c.1539 (

Figure 28), in St Canice’s, Co. Kilkenny, as well as a fragment of a sixteenth-century tomb chest in St Patrick’s Cathedral, Cashel, Co. Tipperary, all have rather striking loincloths that billow out to the sides in line with contemporary Northern European depictions.

The gospels mention the crown of thorns as given to Christ at the mocking (Matthew 27:29), and the apocryphal gospel of Nicodemus describes it being placed on his head at the crucifixion (

Schneemelcher and Wilson 1963, vol. 1, p. 459). From the Carolingian era, theologians interpreted the crown of thorns as Christ bearing the sins of humanity on his head, and it was in these terms that it was understood by the fifteenth-century poet Maolmhuire mac Cairbre Ó hUignn when he wrote ‘twas (our) sin which the (wounded) breast and the crown (of thorns) forgave us’ (

Aithdioghluim Dána, poem 77, stanza 32;

Jordan 2011, p. 61). As a motif, however, the crown of thorns appeared infrequently in western art of the earlier Middle Ages which preferred a royal crown or bare head as in the

Southampton Psalter (

Figure 1) or the Romanesque crucifixion figures in the National Museum of Ireland. The cult of the crown of thorns became increasingly popular after St Louis acquired the crown of thorns (and numerous other relics of the crucifixion) and built the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris in its honour in the late 1230s and 1240s. The influence of this event on the spread of crown of thorns imagery has been widely documented. In thirteenth-century England the crucified Christ is occasionally depicted wearing the crown of thorns, but by the fifteenth century the motif had become universal (

Herbermann et al. 1908, vol. 4, p. 541;

Jordan 2011, p. 62;

Kauffmann 2003, p. 181;

Roserot de Melin 1939, pp. 200–6).

The majority of images of the crucifixion in the later period in Ireland depict the crown of thorns. The preferred mode is a rope-like circlet as on a cross from Kilmore Churchyard, Co. Meath, c.1575 (

Figure 29a), the fifteenth-century Effigy of Two Butler Knights in Gowran, and the tombs of Walter Brenach and Katherine Poher in Jerpoint Abbey (

Figure 19) and Piers Butler and Margaret Fitzgerald in St Canice’s, Co. Kilkenny (

Figure 28), though interlaced versions occur in the

Leabhar Breac (

Figure 3) and Holycross Abbey (

Figure 5), and spiked versions appear on the Sheephouse (

Figure 17) and Sligo Friary (

Figure 16) processional crosses. Passion narratives across Europe in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries elaborated on the torments of Christ, describing his beard being pulled, his cloak removed with such violence that it pulled pieces of flesh with it, and the thorns in the crown ‘so sharp and long that they pierce his brain-pan.’ This elaboration in text is paralleled in the contemporary elaboration in imagery with the introduction of new themes and motifs including the Man of Sorrows and Pietà, and an increased attention paid to the role of the Virgin in the Passion (

Bestul 1996, p. 146;

Viladesau 2006, p. 155).

Whether Christ bears the crown of thorns, is nimbed, or bare-headed, in nearly all cases he wears his hair long to his shoulders or beyond, often curled or terminating in a roll as on a slab from the tomb of James Shortall, now on that of Piers Butler and Margaret Fitzgerald in St Canice’s, Co. Kilkenny, 1507 (

Figure 30). He is usually, though not always, bearded. Typically, Christ’s head wilts to the side as on the Tomb of Edmund Archer and his wife, Thurles, Co. Tipperary (

Figure 6), sometimes to the point of resting on his right shoulder as in Kilcooley Abbey, Co. Tipperary (

Figure 25) and on a fragment of an early sixteenth-century bronze crucifixion plaque from Dunbrody Abbey, Co. Wexford. The eyes are closed, life extinguished.

It is worth noting here that while the extant examples are largely in stone and metalwork, crucifixions would have been commonplace images in other media including wood carvings, wall paintings, textiles, and prints. In 1361, Thomas FitzMaurice, Earl of Kildare, recorded the expenditure of Dublin Castle and the Royal Chapel including ‘one small Crucifix painting newly made for the Chapel, and also a large Crucifix painting, an image of Mary and John, and an image of the Virgin Mary’. Ennis Friary is known to have had a rood screen with an image of the crucifixion in the late fifteenth century. Fragments of a wall painting of the crucifixion may be found in St Patrick’s Cathedral, Cashel, Clare Island, Co. Mayo, Muckcross Friary, Co. Kerry, and Court Friary, Co. Sligo (

Gilbert 1865, pp. 544–45;

Krasnodębska-d’Aughton 2016, p. 76;

Morton 2006, p. 55). Two large wooden crosses, probably gilt and ornamented with precious gems, were venerated in Donegal during the period. The ‘Holy Cross’ of Raphoe Cathedral was said to have cured the eyesight of Aodh mac Mathghamhna in 1397 and to have rained blood miraculously from the wounds in 1411. Another, the Great Cross of Colmcille or

crux magna, reputedly a gift from Pope Gregory the Great to St Colmcille, was kept on Tory Island during the time of Manus O’Donnell (†1564). The dissolution of the monasteries and associated iconoclasm of the mid sixteenth century was responsible for the loss of the well-known crucifixes of Holy Trinity Cathedral, Trim, and of Holy Cross, Ballyboggan, Co. Meath. The scribe of the

Annals of Loch Cé goes as far as to state that ‘there was not in Erinn a holy cross, or a figure of Mary, or an illustrious image, over which [English protestant] power reached, that was not burned.’ An early seventeenth-century description of the since lost stained glass in St Canice’s, Kilkenny, speaks of a ‘most skilfully depicted […] Life, Passion, Resurrection, and Ascension.’ Crucifix pendants were worn by both men and women as recorded in sixteenth-century wills and drawings of Irish dress. The carving of Sir Walter Bermingham (†1548) on his tomb at Dunfierth, Co. Kildare, for example, shows him wearing a crucifix pendant around his neck. A small number of such pendants survive in the National Museum of Ireland. Monastic seals, such as those of Holycross Abbey, would have widely disseminated crucifixion imagery. In fact, Roger Stalley has highlighted a close similarity in the treatment of the crucifixion on the seal in use at the abbey by 1429 and the crucifix figure on the Shrine of the Book of Dimma (

Figure 8). Imported items were also ornamented with depictions of the crucifixion. Waterford Cathedral for example had a collection of copes of Italian and Flemish work in the fifteenth century, one of which is embroidered with a scene of the crucifixion (

Annals of the Four Masters for the year 1397;

Annals of the Four Masters and

Annals of Ulster for the year 1411;

Ó Floinn 1995, pp. 132–33;

Annals of Loch Cé and the

Annals of Ulster for the year 1538;

MacLeod 1947, pp. 54–55;

Buckley 1896, p. 241;

Moran 2006, p. 132;

Flavin 2014, pp. 76, 111–14;

Stalley 1987, p. 225;

McEneaney 2006, p. 42).

3. Devotion before Narrative

In the earlier medieval period in Ireland, the crucifixion was frequently depicted as a narrative scene or element within a narrative sequence. On the late ninth- or early tenth-century Cross of Muiredeach at Monasterboice, Co. Louth, the scene of the crucifixion is part of a sequence that includes the mocking of Christ, the resurrection, and ascension. Various other figures are also included such as angels and the soldiers, Stephaton and Longinus. A group of eight crucifixion plaques dating to the eleventh and twelfth centuries all depict the crucified Christ attended by angels and flanked by the soldiers. An elaborate version of the scene appears on a Romanesque lintel at St Lurach’s Church, Maghera, Co. Derry, incorporating eleven figures, including the two thieves crucified alongside Christ (

Bourke 1993, p. 175l;

McNab 1987, pp. 19–33;

Stalley 2020, especially chp. 8). By the later period, the iconographic focus had shifted away from narrative towards a more devotional approach.

Later medieval depictions of the crucifixion frequently show Christ on the cross alone, highlighting the pity and isolation of his sacrifice, as on the Shrine of the Book of Dimma (

Figure 8), the

Leabhar Breac miniature (

Figure 3), and the Kilcormac fragment (

Figure 14), or as accompanied by the Virgin and St John the Evangelist at the foot of the cross as on the tomb slab in Inistioge, Co. Kilkenny (

Figure 7), or the tomb of John Grace in St Canice’s, Co. Kilkenny (

Figure 27). Devotional literature such as Bonaventure’s

Lignum Vitae, the

Dialogue of Pseudo-Anselm, and the

Meditations emphasised the emotional suffering of the Virgin at the death of her son. The efforts of the Virgin to restore Christ’s dignity and modesty with her veil were mentioned earlier. The

Lignum Vitae likewise details Christ’s death and encourages the reader to empathise with the Virgin and share in her distress at the scene of the crucifixion. In line with this thinking, distilling the iconographic moment to present just these two figures at the foot of the cross offers a more devotional treatment of the subject, provoking a sense of grief, reflection, and personal interaction: ‘the two living witnesses invite the beholder to emulate their mourning as they point to the dead hero’ (

Cousins 1987, pp. 384–86;

Belting 1994, p. 358).

Where the crucifixion does appear as part of a cycle or sequence, the choice of subjects tends to highlight the suffering of Christ rather than provide a simple narrative or biblical chronology. Alongside the Virgin and St John, the sun (

sol) and moon (

luna) are presented on a wayside cross from Lismullin, Co. Meath. This iconography of darkness serves to heightens the drama, imbuing the scene with a sense of foreboding and the awesome power of God. The crucifixion on the O’Fogarty Chalice, 1598, is surrounded by the

arma Christi and the skull of Adam. The tomb of Piers and Margaret Butler in St Canice’s (

Figure 28) presents the crucifixion alongside the

arma Christi and a scene of the flagellation. A cross in Kilmore Churchyard, Co. Meath (

Figure 29a,b), pairs a scene of the crucifixion on the south side, with the five wounds in a circular arrangement, with the crown of thorns, ladder, scourge, hammer, three nails, and pliers on the north side. The McGrath tomb in St Carthage’s Cathedral, Lismore, Co. Waterford, 1534, depicts the crucifixion alongside numerous devotional images including the

Ecce Homo,

arma Christi, Mass of St Gregory, and the Seven Sorrows of the Virgin. The indulgence slab at St Brigid’s Cathedral, Kildare (

Figure 12), depicts the crucifixion in conjunction with an image of the five wounds complete with the words ‘

ecce homo’ and an inscription granting twenty-six years and twenty-six days of indulgence to those who recite five

Pater Nosters and five

Ave Marias in front of it. Małgorzata Krasnodębska-d’Aughton has likewise commented that the Passion scenes in the fifteenth-century iconographic programme at the Franciscan friary in Ennis were not simply following their sources but specifically chosen ‘to stress the humility of Christ’ (

Krasnodębska-d’Aughton 2016, p. 88).

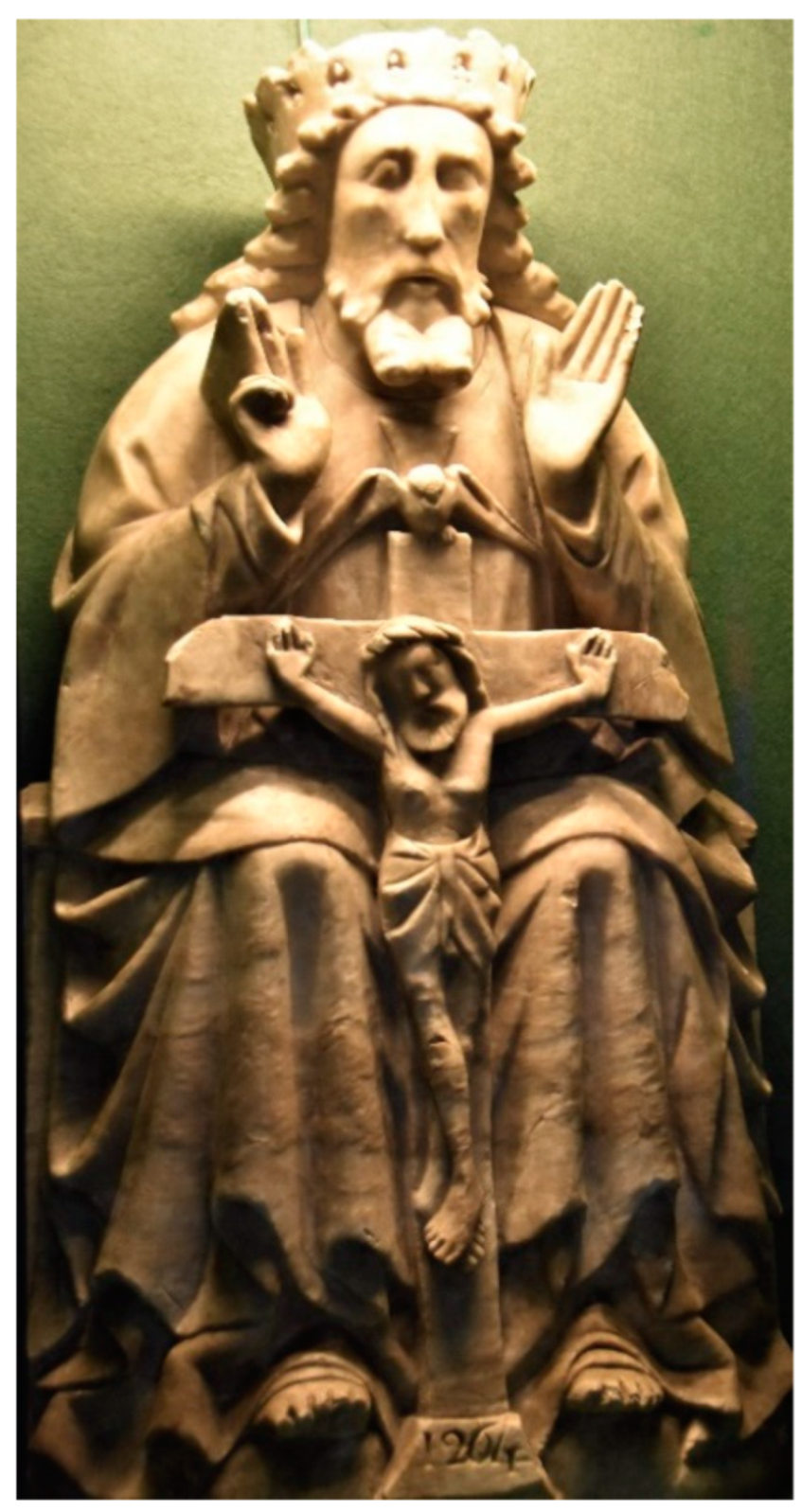

Images of the crucifixion also appear as part of depictions of the Holy Trinity during the period. Typically, the three persons were depicted as the Throne of Grace, whereby God the Father and the Holy Spirit appear in a vertical formation with Christ on the cross. Fifteenth-century examples may be found in an alabaster statue group in the Black Abbey, Kilkenny (

Figure 31), on the tomb of James Rice in Christ Church Cathedral, Waterford, 1482, and a wooden statue group from Fethard, Co. Tipperary, c.1490–1520, of which only God the Father survives. Sixteenth-century examples are found in Callan, Co. Kilkenny, the Purcell tomb in St Werburgh’s Church in Dublin, and in the Church of the Assumption, Ballynabrackey, Co. Meath, originally from a tomb sculpture in the Augustinian House of the Holy Trinity, Ballyboggan (

Figure 22). While these images are restrained rather than gruesome, the depiction of the cross emphasises Christ’s suffering. The iconography is designed to evoke an emotional response from the viewer, to move the viewer to penance and contemplation both of Christ’s sacrifice for the salvation of mankind as the result of a decision by all three persons and of the fate of the viewer’s own mortal soul. A number of the examples mentioned occur on tombs or fragments from tombs and this is consistent with a rise in funerary Trinitarian imagery across Europe from the second half of the fourteenth century. François Boesflug associates this concern with the consolatory power of the Holy Trinity: devotees at their hour of greatest need seek comfort directly from the three persons and pity and understanding from a suffering Christ (

Boesflug 2001;

Roe 1979).

This trend is typical of the broader European shift in devotional focus during the period. While earlier medieval imagery tended to portray the crucifixion in a narrative sequence culminating in the resurrection in the earlier period, by the later period the emphasis had turned to Christ’s human sacrifice. As Richard Viladesau states:

in the Romanesque period, the cross is primarily portrayed not merely as an element in the earthly story of Jesus but in the light of his resurrection and his divinity. In the Gothic crucifix, by contrast we see an increasing emphasis on the human story of Jesus, and on a particular moment in that story. […] Such portrayal is in line with the tendency to see in art not merely a presentation of doctrines or facts but a dramatic reliving of events.

This acute emphasis on suffering is also apparent in Irish depictions of the Instruments of the Passion or

Arma Christi during the period. In keeping with the wider European context as mentioned earlier, throughout the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries the number of instruments of the Passion depicted in Ireland increased leading to increasingly graphic imagery. The tomb of abbot Philip O’Molwanayn (†1463) at Kilcooley Abbey, Co. Tipperary (

Figure 32) contains a shield with two nails, a crown of thorns on a cross, a ladder, pincers, a cock on a pot, a spear, a pillar, a seamless garment, three dice, two scourges, and a hammer. As Salvador Ryan has demonstrated, this emphasis on suffering and the enumeration and proliferation of the tools of the torment transformed the earlier conception of Christ in art and bardic poetry as warrior and triumphator over death into the pitiful and evocative Man of Sorrows (

Ryan 2007, pp. 119–20,

2014, p. 246).

This image of the Man of Sorrows surrounded by the instruments of the Passion was designed to move viewers to tears and repentance, and it gained in popularity during the later period. Much of its popularity is believed to have derived from the origin story of the image. It was said that while celebrating mass at Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, Rome, that Pope Gregory the Great (†604) had a vision of the Man of Sorrows emerging from the tomb. The revelation was recorded in a Byzantine painting, which then supposedly made its way to Rome in the late fourteenth century and an indulgence of some 20,000 years was made available to those who prayed before it. This indulgence was then extended by Pope Urban VI to apply to licenced copies of the image, and over time the remission increased to 45,000 years (

O’Kane 2005, p. 69;

Ridderbos 1998, p. 145). This promising incentive promoted the wide dissemination of the image across Europe. A sixteenth-century fragment from the Carmelite Priory, Co. Kildare (

Figure 33) depicts a dejected Christ, feet and hands bound, his head drooping under the crown of thorns and the words ‘

Ecce Homo’ inscribed next to him. The Tomb of Bishop Wellesley, Co. Kildare, c.1539, presents a poignant image of Christ: beaten, emaciated, feet and hands bound, eyes cast downwards, and seated among the instruments of his torture (

Figure 34). The fifteenth-century Man of Sorrows image in Ennis Friary depicts an isolated Christ looking outward from the tomb and surrounded on all sides by the arma Christi. The late fifteenth- or early sixteenth-century wooden sculpture of the Christ on Calvary from Fethard, Co. Tipperary presents a tragic figure, knees torn, seated next to a skull, awaiting death. A miniature in the

Seanchas Burcach, f18r (

Figure 23b), presents a devotional image of the Man of Sorrows or the five wounds, depicting a bound, wounded, and heavily bleeding Christ gazing outwards at the viewer and carrying the staff from his mocking. Christ stands on a dais surrounded by figures pointing at him. Through their gestures and gazes, these figures invite the viewer to behold the broken body and contemplate the humiliation of their Saviour.

It is evident from the increased emphasis on the suffering of Christ, the proliferation of the Instruments of the Passion, and the emergence of new types of imagery such as the

Ecce Homo, that the iconographic intent of such imagery was to move the viewer at the piteous sight of a tortured and humiliated Christ. At the same time, however, there was also a concern demonstrated for amalgamating the types of Christ as victor and Christ as sacrificial victim in the one image. Christ’s eyes on the Sligo Friary Processional Cross (

Figure 16), for instance, are shown as open and his head is upright, stressing his victory over death. On the other hand, he wears a spiky crown of thorns and the spear wound in the side is shown indicating the pain and suffering inflicted. The Fertagh Christ (

Figure 4), despite offering one of the most harrowing depictions of emaciation and contortion of the legs and mouth, clearly has his eyes open, his head is upright, and his arms are outstretched rather than sagging under the weight of his body. The fifteenth-century Market Cross in Athenry likewise shows Christ with his head held vertically and his arms in a strong position. The head of Christ on the tomb of Bishop Walter Wellesley (

Figure 10) is inclined to the side and his eyes are closed; however, Christ smiles sweetly and next to him St John beams at his triumph over death. A similar trend occurs in bardic poetry, utilising motifs of torture and those of triumph in the same poem. The poetry of Tadhg Óg Ó hUiginn offers the earliest examples of the Charter of Christ in Ireland. This gruesome allegory describes a charter granted by Christ to mankind, which is written not on parchment but Christ’s own skin. The writing implements are the Instruments of the Passion and the inkwell the blood oozing from his side wound. The wounds are thus both acts of torture and acts of love and redemption. In his analysis of the motif of the five wounds in bardic poetry, Salvador Ryan has noted that in the sixteenth century, the image of the Christ hero evolved into that of a prince striding to victory, both despite and because of the deadly wounds he has suffered. ‘This was the marvel […]’ Ryan writes, ‘the paradox of Christ winning a stunning victory precisely at the moment when he receives what was considered to be a death-wound. In spite of the preoccupation with Christ’s physical suffering and abject humiliation in late medieval devotional literature, the figure of

Christus triumphans had not left the stage’ (

Breeze 1987, pp. 111–20;

Ryan 2016, pp. 300–1, 305–6).

12 4. Immediacy, Indulgence, and Interaction

This violent, graphic, and often gruesome imagery in both art and the literature helps to create a sense of immediacy, to bring alive the message, and to jolt the viewer or reader into meaningful contemplation of the event and its implications. The importance of this immediacy in literature is evident where authors directly address their audience and instruct them to act in a particular manner. The

Smaointe Beatha Chriost encouraged the reader to meditate on the various stages of Christ’s death by considering the Instruments of the Passion: ‘raise the eyes of your mind now and you will see a band of them thrusting the cross into the ground, and another group preparing a sign and another gang readying a hammer and another crew preparing a ladder and other instruments’ (

Smaointe Beatha Chriost, p. 146;

Meditations on the Life of Christ, p. 333;

Ryan 2007, p. 113). The text directs the reader to visualise the horror step by step in order to participate and ultimately share in the suffering. Likewise, Tadhg Óg Ó hUiginn, writing in the fifteenth century, instructs his readers to:

Behold the wounds on Christ, the three nails, the Cross with the crown on it; great even yet is the pain pictured by it.

Every Christian believes in Him; behold then His crown on His head; to see the King thus placed before you is a testimony that pains thee.

Before us is the wound in His heart kept open through (God’s) wrath, and the red blood welling up over its edge; (God’s) anger and vengeance is stirred at the sight of that blood.

(Aithdioghluim Dána, poem 78, stanzas 35–37)

Such direct instruction expects a deeply emotional engagement with the reader. The experience of devotion should be so vivid as to elicit a physical response and to participate in the suffering of Christ. This helps to create a sense of immediacy, making a past event a present event.

May I mount the cross for Thy sake and suffer death for Thy death; may my blood be shed in Thine; may I be wounded in Thy wounding.

(Aithdioghluim Dána, poem 92, stanzas 12–18)

Direct interaction between the supplicant and a physical object played a regular role in devotional and commemorative practice in medieval Ireland. Personal devotional pendants worn on the body permitted the owner to contemplate the suffering of Christ where and whenever they chose. Upon opening one such pendant, likely dating to the mid sixteenth century and now housed in the National Museum of Ireland, images of the Man of Sorrows and the Virgin and Child are revealed to the supplicant. As witness to the distress of her son, the Virgin encourages the owner to bear witness also. Books were performative objects, expecting the scribe to bring alive a moral, character, or history, and expecting the reader to engage in an active, meaningful way. Scribal notes in the

Book of Lismore, Cork, University College Library, sought prayers for the patrons, Finghin Mac Carthaigh Riabhach and his wife, Catherine, daughter of Thomas, eighth Earl of Desmond, of all who read the hagiographies of Sts Brigid, Patrick, and Colmcille: ‘Let everyone who shall read this Life of Brigid give a blessing to the souls of the couple for whom this book was written’ (

Book of Lismore ff. 53r, 42e, 49r;

The Lives of the Saints from the Book of Lismore, pp. 34, 182 for Brigid, pp. 1, 149 for Patrick, pp. 20, 168 for Colmcille;

Ralph forthcoming). A wayside cross in Summerhill, Co. Meath, features a scene of the crucifixion, and the inscription requests the viewer to: ‘ORATE/PRO A/NIMA/PETRI/LINCE/AD 1554.’ The positioning of such crosses along thoroughfares encouraged a promising number of passers-by to engage with and pray for the souls of their patrons. Other crosses, such as those at Sarsfieldtown, c.1500, and Rathmore, 1519, offered indulgences of thirty and two hundred days, respectively, for those who paused to say a prayer for the donors of the crosses (

King 1984, pp. 102–3, 111). The faithful were encouraged to kneel before, meditate upon, and kiss devotional imagery in the fifteenth century. At the opening of the canon of the mass, the priest would repeatedly kiss the canon page of his missal and touch the page with nose and forehead. The kissing of manuscript miniatures was such standard practice that illuminators might provide a sacrificial substitute in the form of a simple gilded cross in the lower margin in order to preserve the image of the crucifixion as in London, British Library Stowe MS 10, f113v and Haarlem, Stadsbibliotheek MS 184 C 2, 149v. The touching and kissing of devotional imagery and relics was a wide enough practice in Ireland that in 1539 instructions were given to the Commissioners in Ireland to investigate and root out such superstitious and idolatrous traditions (

Duffy [1992] 2005, p. 214;

Rudy 2010, pp. 1–2;

MacLeod 1947, p. 53).

The ritual recitation of prayers for indulgence, as mentioned above, is a prime example of this interaction. The remission of sins offered by the indulgence slab in Kildare pales in comparison to some of the indulgenced images of the crucifixion in circulation during the later Middle Ages. A graphic depiction of the crucifixion with blood spurting from Christ’s body, Cambridge University Library MS Additional 5944(11) (

Figure 35), is thought to have been produced c.1480–1490. The indulgence is written in Dutch and offers the bearer an astonishing 80,000 years’ remission from purgatory. A note in a fifteenth-century Book of Hours, Cambridge University Library MS Dd.15.19, f158v, records a prayer to be said in front of a scene of the crucifixion that supposedly offers a papal dispensation of ‘as many dayes of pardon as be gravel stonis in the see and herbis grewyng on the erth.’ Such promises may well have been ‘dubious’ and theologically ‘highly questionable’, but they are nevertheless ‘revealing of the mix of aspirations and attitudes’ of the society who made and followed them. Indulgences, while obviously highly rewarding and desirable, were also very complex. As Robert Swanson relates, ‘the dissemination and reception of prayer indulgences was highly complex, particularly in manuscripts. A prayer carrying an indulgence in one volume may lack it elsewhere, yet readers maybe knew of the pardon’s existence from another source, or among their cultural baggage of personal devotions, and took its availability for granted: indulgences absent from books might still be present in minds’ (

Swanson 2007, pp. 248–49). Some of the tombs mentioned earlier also carry indulgences. The tomb of James Shortall and Katherine Whyte in St Canice’s for example offers an indulgence of eighty days to ‘everyone who shall say the Lord’s Prayer and the Hail Mary for their souls and the souls of their parents.’ The tomb of Walter Brenach and his wife Katherine Poher in Jerpoint Abbey likewise offers an indulgence of forty days for those who say the Lord’s Prayer, Hail Mary, and the Apostles Creed for their souls (

Rae 1971, pp. 20, 33). In combining the moving iconography of the crucified Christ with the enticing rewards on offer, the patrons perhaps hoped to at once record their own devotion to Christ’s sacrifice as well as spurring on those left behind to pray for their souls, in an appeal to both their emotive and pragmatic sides.

The tangible benefits of prayer and contemplation on the crucifixion were clear to the scribe of the mid fifteenth-century

Liber Flavus Fergusiorum, Dublin, Royal Irish Academy MS 23 O 48, f36v, who writes ‘If you go to Mass out of love and pray before the cross of crucifixion, the doors of Heaven will open to you and the doors of Hell will close and all the demons will not be able to attack you.’ Similar rewards are also recorded in the

Leabhar Chlainne Suibhne, Dublin, Royal Irish Academy MS 24 P 35, p45. Likewise, the power of images was well understood by the scribe of the

Leabhar Breac (

Ryan 2002, vol. I, p. 362;

MacNiocaill 1956–1957, pp. 74–75). The narrative of the Passion of the Image of Christ relates not only the intense vitriolic emotion roused in the community of Berytus in Syria upon discovery of a secret image of Christ—causing the townspeople to spit on it, drive nails through it, and spear it in the side—but also of the miraculous deeds associated with it. As at the time of ‘the first Passion,’ when the image was crucified, ‘the elements shook [and] heaven rocked.’ When the image was pierced in the side, the wound issued blood and water that ‘healed people of every sickness and disease throughout Asia Minor’ (

The Passions and the Homilies from the Leabhar Breac, pp. 278–86, 282–83).

The iconography of the crucifixion in late medieval Ireland is one of suffering and humiliation. In line with contemporary European iconography and thinking, Irish artists emphasised Christ’s sacrifice, his pain, his blood loss, and his humiliation in order to save mankind. Unlike the graphic, bloody imagery present in Irish bardic poetry and typical of Northern European art, however, Irish artists generally preferred a more poignant and devotional approach to the scene of crucifixion. Depictions of the crucifixion were designed to move the reader, to prompt their prayers and contemplation, and to provoke their devotional gaze. Images could be powerful objects, and a scene of the crucifixion could demand an active response from the viewer: a direct interaction between object, viewer, and the suffering Christ. This is made plain in the example of the indulgenced image or devotional image where the devotee recites prayers ritualistically over a scene of the crucifixion or the five wounds hoping to receive a tangible benefit in this life or the next. On funerary monuments, imagery of the crucifixion demonstrates both the supplicant’s continued devotion to the Passion and their appeal to Christ and the Trinity to aid their journey in the afterlife. Images within the church, hanging on walls, forming the windows, ornamenting the chalices, or dressing the priest or altar present a visual anchor to the congregation’s prayers and help to bring alive the mystery of the Eucharist. Images in the hand or at the lips provide for a multisensory devotional experience—seeing, touching, kissing the object, and speaking the words of a prayer. Disquieting imagery of the crucifixion was designed to elicit a deeply emotional response from the viewer, to help them to imagine themselves before an agonised Christ on the cross. A more nuanced reading of some of the imagery, however, illustrates that crucifixion scenes were also designed to remind the viewer that it was in the moment of Christ’s greatest suffering that he achieved his greatest triumph.