Abstract

Though rural Protestant missionaries stationed in Cuba routinely reproduced Anglo-American epistemologies and values, often in the service of US corporations, they also worked alongside their parishioners to challenge state and economic violence, as well as break the cyclical nature of Cuban poverty. Shared struggle with Cubans against Fulgencio Batista’s dictatorship proved transformative for many rural missionaries who, in the late 1950s, developed a revolutionary consciousness born through transnational solidarity. Missionaries challenged the dominant narrative coming from the US government and foreign corporations, as the Revolution pursued an increasingly anti-imperial and anti-capitalist agenda after Batista entered exile. While corporate executives and government officials from North America and Europe feared the new government, rural missionaries, often funded by these same corporations, defended the structural changes taking place after 1959. Through oral history and archival research, this article exposes how Cuban Protestants proved particularly influential in shaping the lens by which foreign missionaries came to understand, appreciate, and ultimately support the Cuban Revolution.

1. Introduction

In her 1959 Annual Report to the Methodist Board of Mission back in New York, rural missionary leader Eulalia Cook took note of the radical changes Cuba had recently undergone as a result of the Revolution: “[Being] a part of a church in a country under military rule, in tremendous civil disorder, gave me a new understanding of The Light that Shineth in Darkness and the Darkness cannot overcome”. Cook compared Batista’s flight from Cuba as, “the sunrise after a long, dark night”.1 For Cook and many rural missionaries throughout the island in 1959, the Cuban Revolution was much anticipated, representing a moral, spiritual, political and material transformation they had dedicated their lives to attaining.

Scholars have long exposed how foreign missionaries acted as agents of US cultural imperialism in Cuba between the end of the nineteenth century and the 1960s.2 This article inverts the lens typically used to study US influence in Cuba by exploring how these religious agents of empire were impacted by those to whom they preached. In 1950s rural Cuba, the priorities and commitments of foreign Protestant evangelizers were fundamentally altered by intimate relations with Cuban and Caribbean Protestants. Rural foreign missionaries’ relationships with vulnerable populations in Cuba proved radically different from the deeply stratified contact between Anglo-American executives and their employees.3 Where a foreign administrator treated most Cuban and Caribbean laborers as disposable, but necessary tools in their pursuit of capital, foreign missionaries from ecumenical denominations saw a potential student, parishioner, or fellow Protestant worker helping to transform Cuban society by reducing rural dependency.4

Informed by Cuban and Caribbean Protestants, throughout the 1950s Anglo-American missionaries began to link their own spiritual commitments to the revolutionary movement taking hold on the island. As historian Marcos Ramos documents, a disproportionate share of Cubans who identified as Protestant or attended Protestant schools participated in the struggle against the Fulgencio Batista government (Ramos 1989). Evidence drawn from oral histories, diaries, memoirs and letters suggests that a deep solidarity developed between foreign evangelizers and Cuba’s marginalized populations over time, as they collectively bore witness to brutal manifestations of desperation and violence, imperialism and capitalism, during the late-1950s. Many rural missionaries, and particularly women missionaries, witnessed the abuses of the Batista government and the exploitation by US corporations firsthand. They came to understand both as obstacles to the moral and equitable society they hoped to construct with their fellow Protestants in Cuba.

While religious scholars have detailed the critical gaze that evolved in the ecumenical missionary movement over the first half of the twentieth century, leading works such as David Hollinger’s Protestants Abroad center the experiences of missionaries outside of Latin America (Hollinger 2017). Hollinger convincingly describes how many missionaries pushed back against the sense of cultural superiority inherent to missionary work. In the process, Hollinger shows how the most influential missionaries and their children altered US society by promoting an anti-racist and often anti-imperialist ethos.5 This article builds on Hollinger’s arguments by highlighting the robust missionary project in Cuba during times of revolution. In 1925, Hollinger notes there were around 4000 missionaries in China, serving a population of nearly 475 million people. Thus, for every missionary stationed in China there were nearly 120,000 Chinese. By contrast, Marcos Ramos estimates there were 225 missionaries in Cuba by end of the 1950s serving a population of seven million. This means there was a missionary for every 31,000 Cubans (Hollinger 2017, p. 71). In Cuba, these missionaries served a Protestant community that had blossomed to six percent of the total population by the mid-1950s in no small part due to the failures of the Catholic Church on the island. Still, Cuban Protestants remained almost exclusively under the domain of US mission boards before the Revolution took power (Ramos 1989, pp. 34, 134). Cuba as a case study creates a better understanding of the introspective anti-imperialist agenda that developed among missionaries because of the extensive US imperial project in Cuba and the island’s radical break from US empire that began in 1959.

This article begins by identifying the revolutionary foundations of Protestantism on the island before turning to the competing and often contradictory goals of rural foreign missionaries and their corporate benefactors. It then explores why rural missionaries felt motivated to address local suffering, a result of the dictatorship and the foreign-dominated sugar economy. The work proceeds by detailing the contexts that made women missionaries particularly sympathetic to the revolution enveloping Cuba in the late 1950s. The article then examines the specific ways in which rural evangelizers supported Cubans revolting against their government. The penultimate section argues that Protestant values deeply influenced revolutionaries, which rendered the Cuban Revolution legible to many missionaries. Finally, tracing the fall of their privileged status, the final section chronicles the growing vulnerability of Protestants on the island in the early 1960s.

Though rural missionaries stationed in Cuba routinely reproduced Anglo-American epistemologies and values, often in service of US corporations, they also worked alongside their parishioners to challenge state violence and break the cyclical nature of Cuban poverty. In this way, rural missionaries proved somewhat of an exception to a phenomenon, correctly identified by Cuban historian José Vega Suñol, that Anglo-Americans in Cuba accumulated economic and social advantages, while avoiding integration into Cuban society (Vega-Suñol 2004). Postcolonial theorist Sandra Harding argues that “[only] through…struggles can we begin to see beneath the appearances created by an unjust social order to the reality of how this social order is in fact constructed and maintained” (Harding 1991, p. 127). By struggling together with Cuba’s marginalized populations against Fulgencio Batista’s dictatorship, many rural Anglo-American missionaries developed a revolutionary consciousness in the late 1950s. While corporate executives and government officials from North America and Europe feared the new Cuban government, foreign missionaries, often funded by these same corporations, defended the anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist structural changes taking place after 1959. Cuban Protestants proved particularly influential in shaping the lens by which Anglo-American missionaries came to understand, appreciate and ultimately support the Revolution, even as some grew disillusioned with the Revolution by the mid-1960s.

2. Revolutionary Foundations of Protestantism in Cuba

Protestantism in Cuba was largely introduced by Cuban Protestants at the end of the 19th century, with foreign missionaries arriving later than missionaries elsewhere due to the persistence of Spanish colonial rule until 1898. During the Cuban Wars of Independence, between 1868 and 1898, an estimated 100,000 Cubans, or one tenth of the population, spent time off the island. Most emigrated north to escape the violence that enveloped Cuba and/or to plot the overthrow of the colonial government (Pérez 1995, p. 55). Frustrated with continued Spanish rule, as well as the crown’s collusion with its close allies in the Catholic Church, many Cuban revolutionaries converted to various Protestant denominations while in exile.6 Because the predominantly Spanish Catholic clergy collaborated so explicitly with the Spanish Crown to sustain their shared authority in Cuba, Catholicism became identified with Spain and the old order.7 Cuban national hero José Martí condemned the Church in Cuba for its complicity with Spanish rule, declaring that “Catholicism must perish” (Kirk 1982, p. 119). Becoming a Protestant in many ways signified a revolutionary act in defiance of the ruling order.8

US Protestants saw an advantage in linking the cause of independence with the downfall of Catholicism and the spread of Protestantism in Cuba. Baptist Pastor Henry L. Morehouse explained that Cubans “in their long and fearful struggle for independence, had a hearty hatred for the Roman hierarchy in league with the tyrannical power of Spain to keep Cubans under the yoke…there was little devotion to the church” (Morehouse 1910, p. 10). Protestant publications in the United States celebrated Cuban revolutionary efforts. In 1896, The Christian Index reported that Cuba’s “struggle for religious freedom is inseparably linked with that of political deliverance…. The fall of Spanish power is the overthrow of the State Church in Cuba…. Her priesthood, who are all of Spanish birth, must follow the footsteps of the Spanish soldiery, and find a refuge in other land” (Pérez 1995, p. 61).

While Cuban and North American Protestants supported Cuba’s fight for independence from the Catholic Church and Spanish authorities before 1898, Cuban demands for sovereignty became a nuisance for foreign mission boards attempting to take over Cuba’s Protestant institutions after 1898. North American mission boards assumed control and demoted the leaders of Cuban Protestantism to subordinate roles within the church hierarchies. While US Protestant publications cheered the US intervention in 1898, they proved less tolerant of challenges to US domination in the years that followed (Urbanek 2012, pp. 47–51; Ramos 1989, p. 23). It would be the missionaries themselves, over the course of the next six decades, who would become critical of US influence, and by extension their own influence, in Cuba.

3. Entangled with Corporate Sponsorship

Anglo-American missionaries gained influence in Cuba because of their nationalities, their whiteness and their ties to foreign capital and Cuban power brokers. They entered arrangements with foreign corporations to provide educational, health and religious services to desperate populations. Their corporate and political benefactors encouraged missionaries to stitch a social safety net in rural Cuba designed, in part, to mollify critiques of social and economic hierarchies.

The tensions between foreign evangelizers and their corporate patrons were obvious prior to 1959. Rural missionaries often hoped to transform Cuban society through their spreading of the gospel and improvement of opportunities for Cubans. Meanwhile, Anglo-American executives, as well as those Cubans who benefited from US influence, sought to maintain the status quo. These foreign administrators worked to sustain corporate profits and an elite lifestyle unavailable to them in their home societies. Foreign influence over the economy left much of the Cuban and Caribbean workforce in perpetual poverty. Through service-oriented activities, Anglo-American missionaries worked to limit suffering where they could.

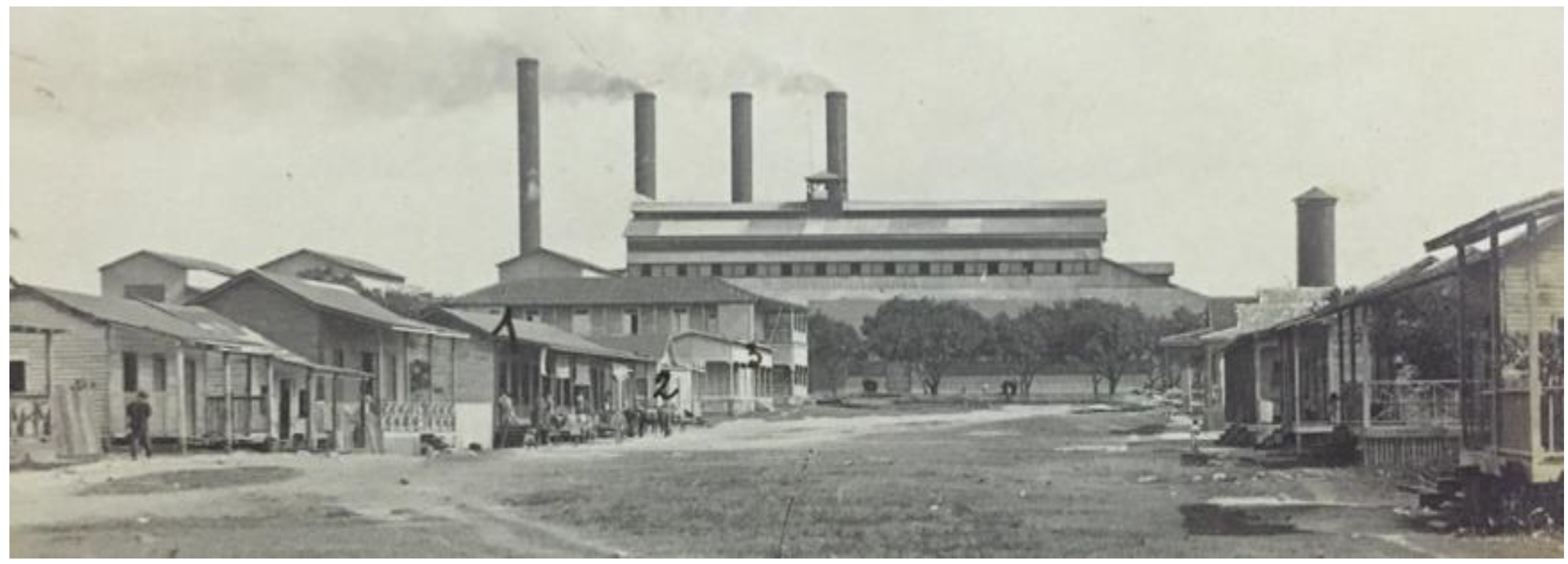

Figure 1.

Cuban American Sugar Company, Chaparra Mill.9

Figure 1.

Cuban American Sugar Company, Chaparra Mill.9

In the first half of the twentieth century, Anglo-American corporations came to dominate the Cuban economy. By the 1920s, North American and British executives controlled Cuba’s communication, electrical and transportation networks, while consolidating their influence over both the sugar and banking industries (See Figure 1).10 Cuban sugar sales became dependent on the US market, making Cubans extremely vulnerable to the whims of US policymakers.11 The dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista (1952–1958) extended dependence on US corporations in Cuba. During this period, Batista promoted foreign investment through “giveaway programs” to mostly US corporations (Farber 2006, p. 29). In 1957, US investment in the Cuban economy surpassed $800 million, revealing what the President of the American Chamber of Commerce in Cuba explained as “the confidence of our investors in [Cuba] and their belief in her future”.12 Batista worked hard to assure Anglo-Americans that their investments on the island were safe and would prosper under his rule. Under the leadership of Eusebio Mujal, Cuba’s largest labour union, the Confederación de Trabajadores de Cuba, functioned as an apparatus of the Batista government to protect foreign and domestic capital. Armed patrols prevented worker uprisings during the mid–late 1950s, especially in sugar zones during harvest (Alexander 2002, p. 143).

Throughout this period, foreign corporations sponsored US missionary efforts to mollify local suffering, which was exacerbated by corporate and political policies aimed at maximizing sums of capital extracted from the island. Similarly to their corporate sponsors and compatriots, foreign Protestant missionaries (largely from the United States) benefited substantially from the influence US capital cultivated during the first six decades of the twentieth century. US sugar and mining corporations often sustained rural missions by donating land and resources, and, as such, the corporations dictated the locations and influenced the goals of Protestant schools, clinics, and churches.13 Rural Protestant missionaries were dependent on corporate support as they maintained their economic stability through access to foreign capital. These resources allowed service-oriented missions to remain fiscally viable even in times of economic downturn when Cuban educational or health ventures that were dependent on local funds collapsed.

Foreign missionaries raised large sums in Cuba and abroad because of their relationship with Anglo-American financial networks, even as these missionaries feared the relationships compromised their work. As the head missionary in Cuba’s eastern mill town of Báguanos, Eulalia Cook expressed serious reservations about missionary and service work in a setting dominated by a foreign corporation. In 1942, she acknowledged discomfort ministering under the shadow of empire: “I had studied too much about ‘American Imperialism’ to feel enthusiastic about working by grace of the permission of a big capitalist”.14 Yet, Anglo-American networks, and capital, proved essential to Cook’s mission. The North American executives at the Báguanos mill, owned by a subsidiary of the Royal Bank of Canada, provided the space and material goods to found the mission in Báguanos, and their endorsement garnered early legitimacy for the rural women missionaries stationed there (Jiménez Soler 2014, pp. 37–38). Eulalia Cook expressed her appreciation of the corporation for enhancing the social position of the Methodist mission in Báguanos: “[The] company’s cooperation made it easier for townspeople to accept the ‘American nuns’, as some liked to call us”.15 Mr. Miller, the chief executive at the mill in Báguanos, ensured a home for the missionaries, funding for their projects, and access to a plot of land for a church and a school.16 Cook and other rural missionaries navigated strategically between their missionary work and their corporate sponsors.

Sixty-five kilometers east of Báguanos, the United Fruit and Sugar Company (UFSC) sponsored both Quaker and Methodist missions in their territory surrounding Bahía de Nipe, provoking the anxieties of missionaries that mirrored those expressed by Eulalia Cook. At the turn of the 20th century, United Fruit entered arrangements with Quakers seeking to evangelize in eastern Cuba. While this partnership was deemed fiscally essential for the Quakers, ties to the UFSC made mission head Zenas Martin uneasy. Martin decided he would not locate the Quaker mission at the UFSC mill in Banes fearing it would become beholden to a “great soulless corporation”. The Quakers would instead begin their work in nearby Gibara. However, corporate sponsorship proved difficult to avoid and within a few years, a Quaker mission would be founded in Banes, with Colegios los Amigos established in 1905. The UFSC leased land in Banes to the American Friends community for 99 years, charging a sum of $1.00. Former Quaker missionary Hiram Hilty explained, “The cynic may say that the United Fruit Company—which literally owned the town—was simply demanding service for value received when it urged English-speaking educational and religious work on Friends at Banes, and there were indeed times when it looked as if [the mission was] merely a part of the company as Zenas Martin had feared they would be” (Hilty 1976, pp. 1–10, 20–22, 58, 117–118).

The success of the Quaker mission at Banes likely influenced UFSC to enter a partnership with Methodists hoping to establish an Agricultural and Industrial School in the company’s vast domain surrounding Bahía de Nipe. In July 1946, the school, nicknamed la granja (the farm), began a ninety-nine-year lease with UFSC at a token cost. Chosen to head the project were missionaries Richard Milk and his wife Juliet, an expert in John Dewey’s program of progressive education. Soon after their arrival, Richard Milk would lament the project was “too completely dependent upon the sugar company for its existence”.17 United Fruit provided water, electricity, telephones, roads, railroad service, building materials, technical workers, and capital to compensate the teachers at la granja.18 The Milks feared that the location of the project, determined by UFSC, would undermine the school’s progressive pedagogical goals.19

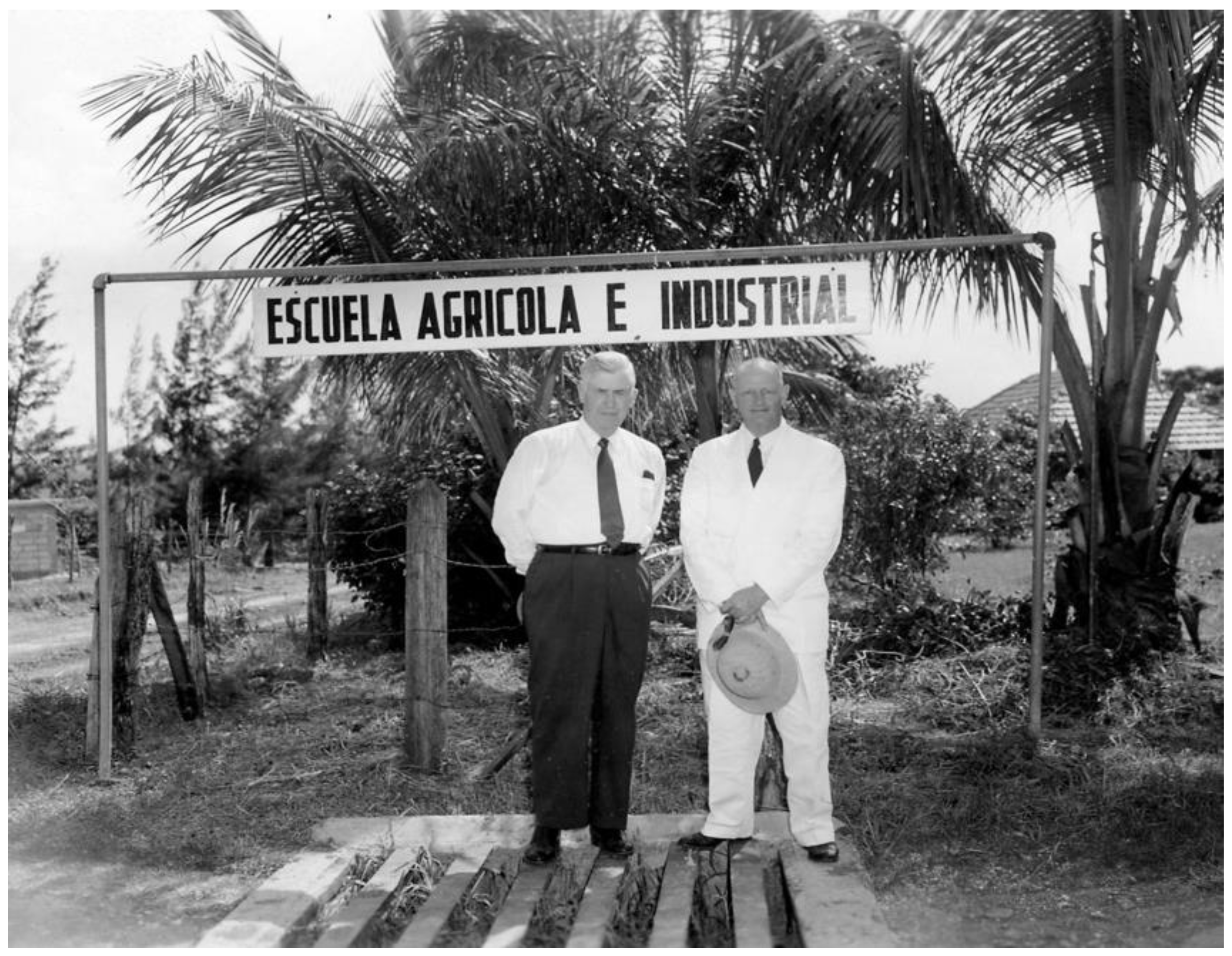

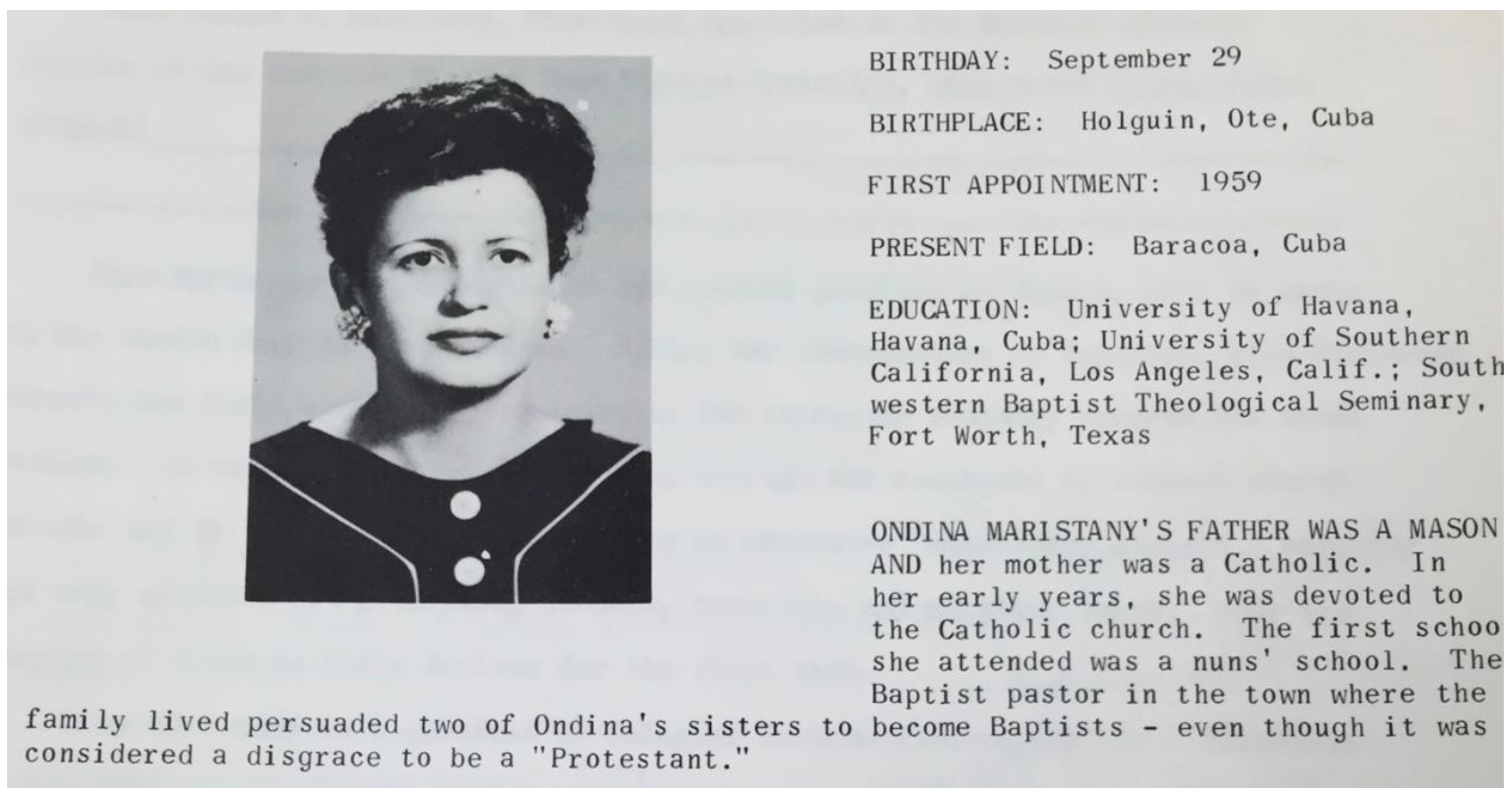

Figure 2.

Richard Milk and Former Vice President Henry A. Wallace 1957.20

Figure 2.

Richard Milk and Former Vice President Henry A. Wallace 1957.20

Despite the anxieties expressed by missionaries, access to Anglo-American networks within Cuba and abroad garnered prestige and financial stability for Protestant institutions. Understanding this, US leaders of la granja purposefully shaped their message for a corporate audience when soliciting financial support from Anglo-American executives in the region, elsewhere in Cuba, and in the United States (See Figure 2). In a fundraising pamphlet, the US leadership of the school appealed to the national myths surrounding the “American Dream” and the entrepreneurial spirit of the United States. The letter encouraged patrons to contribute funds so that Cuban youths could “EARN their way and learn how to live in that part of Cuba”.21 Hundreds of UFSC employees donated both time and money to the school, as had a number of other foreign executives in Cuba.22 Nicholas Rutz, a US rancher and citrus farmer in Cuba whose children attended the Methodist Pinson College in Camagüey, donated a large tractor to the Agricultural School.23 Milk also secured the purchase of a second hand mechanical corn planter from a North American farmer in Omaja, Cuba.24 A friend of Methodist Bishop Roy Short based in Nashville, donated a Ford tractor.25 In 1947, Emily Towe of the Methodist publication World Outlook referenced support from “Many farmers of the southern United States [who] sent over livestock and money”.26 These gifts supplemented a budget dependent on “philanthropic” financial contributions, the limited tuition that could be paid by those students whose families could afford it, as well as the selling of farm produce, including corn and milk.27 While la granja was able to raise a substantial portion of the funds needed to run the school, the administration still depended upon support from Anglo-American networks (Yaremko 2000, pp. 53–54).

The Milks expressed their frustration with juggling competing interests. They felt beholden to the Cuban community, yet dependent on Anglo-American capital. With seats on the board of directors, and as mjor contributors to the school’s stability, the United Fruit and Sugar Company–and to a lesser extent the Bethlehem Steel Company–made their influence felt.28 Edgar Nesman recalled, “Dick Milk returned from [board] meetings very frustrated over some of the restrictions that were imposed.... Milk had a strong feeling for the need of agrarian reform if there was to be good land available for family farms..”.29 While Anglo-American corporate employees sought to profit from the existence of this school through the hiring of semi-skilled labor, Milk aligned with the Cubans who sought to create an economically self-sufficient rural society, infused with Protestant ethics.

Robert Milk, Richard and Juliet’s son, described hearing his father express disgust with UFSC. Robert explained, “United Fruit did not reflect the values that [the Milk’s] would want their children to pursue. They believed in a life of service… not about how can I make the most money in the world”. Robert Milk attended the Preston Lee School for the Anglo-American children of United Fruit executives, but his father warned him that among the Anglo-American employees at UFSC, there were “bigots, racists, drunks…my father did not consider them good role models. It was us and them…. We were not considered them”.30 Even before the Revolution reached their missions, Anglo-American Protestant workers viewed their roles in Cuba as distinct from, and often at odds with, their corporate sponsors.

4. Suffering in the Cuban Countryside

Seemingly forgotten by the Cuban government, exploited by foreign capital, and often visited less than once a year by a Catholic Priest, as well as diverse lives of dependency, hundreds of miles from Havana—the same conditions that made the region fertile grounds for Anglo-American Protestants seeking to build a following—contributed to the context for revolution (Schmidt 2015; Ramos 1989, p. 51). The daily experiences of rural missionaries in Cuba, who hoped to ameliorate Cuban suffering in this life and the next, proved both humanizing and humbling. Many missionaries lived and labored in close contact with Cuba’s disenfranchised populations. In relative isolation from larger communities of Anglo-Americans, rural missionaries often became a part of the Cuban communities they served. An evolving emphasis on the social gospel among the ecumenical Protestant traditions led missionaries to focus on service-oriented projects, opening paths to more intimate forms of contact with Cubans. Rural missionaries, who were disproportionately women, spread their faith through health and educational initiatives, leading to personal, as well as professional engagements with Cubans.31 They witnessed Cuban dependency on, and exploitation by, foreign corporations, such that many would come to re-examine their purpose in Cuba and the structures that sustained the privilege of Anglo-American residents. Further, by the 1950s, a growing number of Cuban pastors achieved leadership positions in Protestant institutions, often as the superiors of foreign women missionaries. This structural shift in Cuba’s Protestant hierarchy forced Anglo-American evangelizers to grapple with the frustrations and aspirations of Cuban Protestants. In these material, social and spiritual contexts, Cuban pastors, Protestant parishioners and North American missionaries developed ethical and political intimacies and empathies, as they collectively pursued remedies for Cuban suffering.

The Social Gospel forwarded by Protestant intellectuals such as Dr. John Merle Davis inspired many rural missionaries in Cuba.32 With input from renowned Cuban scholar Fernando Ortiz, Davis’ far-reaching 1942 text, The Cuban Church in a Sugar Economy, urged the pursuit of service-oriented and independent Cuban Protestant institutions (Ramos 1989, p. 32). As would be the case for missionaries who lived among rural Cuban poverty, Davis accused the North American sugar companies of undermining the potential for Cuban leadership and autonomy: “The Church of Christ in Cuba is a Church of the lower classes and thus it is that one of the chief obstacles to the progress and usefulness of the Church is the poverty arising from a sugar economy”. Davis advocated for “popular use of land, the diversification of crops, the use of spare time, training in farming and industries, the rehabilitation of the individual and the home” (Davis 1942, p. 140). In the early 1940s, Davis helped inspire the expansion of rural work in eastern Cuba.33

In marked contrast to the Protestant institutions serving wealthy Cubans in western Cuba’s urban centers, rural missionaries in eastern Cuba hoped to attract converts by sponsoring service-oriented projects that would provide a basic social safety net for Cuban communities and, over time, transform Cuban society.34 Rural Protestant evangelizers centered their goals on helping Cubans cope with the difficult conditions forged by the foreign-dominated sugar economy (Pérez 1995, p. 65). The Presbyterians operated medical clinics, waged literacy campaigns and maintained transportation, meteorological, educational and social services on the island (Corse 2007, p. 4). The Quakers established a set of schools and churches surrounding Bahía de Nipe (Hilty 1976, pp. 2–10, 20–22, 58). American Baptists provided health, food and elderly services to those impoverished by the foreign-dominated economy.35 Many denominations organized short service trips for faith groups from the United States to visit Cuba for a few weeks and volunteer before returning home.36 The rural work conducted by denominations including the American Baptists, Jehovah Witnesses, Quakers, Presbyterians and the West Indies Mission, likely pressured the Methodists to accelerate plans for the development of rural service projects, which would often be maintained by women missionaries.37 By the 1950s, Methodists were the most active missionary community in rural Oriente, an extraordinarily diverse region comprised of poorer residents with darker complexations than elsewhere on the island. Oriente’s Cubans, alongside Haitian and West Indian migrants, often labored for foreign sugar and mining interests, which were extremely influential in the region, or worked at the US Naval Base at Guantánamo.38

The significant differences between life in urban and rural Cuba provide important context for understanding the development of distinct Anglo-American subjectivities. In urban areas, and particularly in the capital, access to material goods, health care and education facilitated upward mobility for local Cubans. Despite a national illiteracy rate of 23.6 percent, in Havana only 7.5 percent of the population could neither read nor write.39 Havana accounted for 21 percent of the island’s population, but 60 percent doctors and dentists along with 80 percent of its hospital beds (Pérez-Stable 1999, p. 29). By virtue of geography and relative advantages, Anglo-Americans living in Havana for the most part remained unaware of the devastating ramifications of a mono-crop economy controlled directly by foreign capital, or indirectly by dependence on the US market. Most Anglo-Americans in Havana were incapable of fully grasping, and perhaps uninterested in understanding, the harsh realities faced by rural laborers on Cuba’s sugar plantations (Mills 2007, pp. 11–38).

By contrast, rural missionaries in Cuba found themselves immersed in, and transformed by, encounters with socio-economic desperation and the revolutionary energy such desperation inspired. By 1945, 52 percent of Cuban agricultural workers were employed for fewer than four months per year, a consequence of the seasonal nature of sugar production. With the harvest season shortening throughout the first half of the twentieth century due to automation, in the 1950s, many rural Cubans faced perpetual poverty. Three-quarters of the children living in rural regions did not attend school and by some estimates 95 percent of them suffered from parasites (Spalding 1977, p. 233). Most rural households were without running water and over 90 percent of rural Cubans had no access to baths or showers (Oficina Nacional de los Censos Demográfico y Electoral 1953, p. XLV). A 1956–1957 study conducted by the University of Havana found that 34 percent of the nation worked in rural agriculture, but this sector of workers earned only 10 percent of the national income and 69 percent of their income was spent on food. Despite a national illiteracy rate of 23.6 percent, 43 percent of rural workers could neither read nor write (Farber 2006, pp. 20–21).

Figure 3.

La Granja, Late 1940s.40

Figure 3.

La Granja, Late 1940s.40

Rural missionaries expressed shock at the desperation of Cubans in the countryside. In 1949, the Methodist journal World Outlook reported on conditions in rural Cuba: “[The] losers are the children of the poor. One sees them everywhere. Half-starved and listless they go about their games in slow motion, as though every move were an effort…. Most of them are far too thin, except for their huge protruding stomachs, the result of malnutrition and parasites”.41 An article in the same publication written a few years earlier referenced similar dynamics of exploitation: “The workers who have enabled Cuba to become the greatest producer of sugar for export are among the most impoverished people in the world. At the best, they can labor only six months in the fields. The remainder of the year must be spent picking up odd jobs or in idleness”.42 Methodist missionary Edgar Nesman and his wife Margaret, based at la granja, were appalled that education and medical facilities, widely available in urban centers and at foreign-owned sugar mills, “were almost non-existent in the small towns, rural countryside, and mountainous areas”.43 Even where these institutions were present in rural Cuba, accessing them was a privilege often based on nationality and one’s standing in society. For instance, while the staff at la granja had full access to the UFSC hospital in Preston, only “under certain conditions” did the school’s Cuban students enjoy the same courtesy.44

For Anglo-American missionaries integrated into foreign-operated mill towns, the persistent anguish of their neighbors, students, and parishioners, due to the double neglect of the Cuban state and foreign executives, grew increasingly personal (See Figure 3). Speaking of the suffering she witnessed around her, in 1945 Eulalia Cook, head of the Methodist women’s mission in Bagúanos lamented the fate of Bobby Contes, the “twelve-year-old Methodist, oldest of eight children…[who] has to be taken out of school to help his father in the struggle to find food”.45 Rural missionaries such as Cook would recognize, and eventually mobilize against the cruelty endured in Cuba before 1959.

5. Women Missionaries’ Empathy for Suffering Cuban

In the early 1940s, after the publication of The Cuban Church in a Sugar Economy, John Merle Davis was in close contact with the Executive Secretary of the Woman’s Division of the Methodist Missions Board based in New York City. Elizabeth M. Lee reported to Eulalia Cook, head of the Báguanos mission, that Davis “is very much pleased that several of you are following some of the lines he laid down”. 46 After the female-run Methodist circuit of Báguanos was established in 1941, three North American Methodist women oversaw sixteen churches, as well as multiple day and Sunday schools in the region (See Figure 4) (Whitehurst and Whitehurst 2010). These single women missionaries inoculated Cubans against diseases, tested them for parasites, helped with home improvement and organized literacy campaigns. Operating in a company-run mill town, women missionaries often offered the only social services available to community members. In 1943, Methodist missionary Eulalia Cook articulated one of the reasons for the success of the Methodist missionary work at the sugar mill of Báguanos, Oriente: “The missionaries have not tried to carry through any set program, but rather to meet the needs of the community as they have arisen”. Cook’s goals for the mission were shaped by her desire to help rural workers endure the conditions of the sugar economy. Rooted in a participatory ethic, “We have tried to let the people know that the church is interested in all of their problems” (Cook González 2004, pp. 30–31).

Figure 4.

The Báguanos Valley.47

Figure 4.

The Báguanos Valley.47

In the first half of the twentieth century, Protestant mission boards sent single women missionaries to the Cuban countryside where they focused on educational and health projects. By contrast, most male missionaries became pastors and lived in cities with their families, directing their own institutions often designed to attract wealthy Cubans.48 Style and circumstance mattered. In Cuba’s most isolated posts, rural female missionaries lived primarily among Cubans, with few Anglo-Americans in their immediate surroundings. Larry Rankin remembers that male missionaries “tended to hang out in the cities [while] the women were out among the very poor…”.49 Rankin continues that in these roles

Single women missionaries had a profound impact on the development of Cuban leaders. They founded community centers, schools, clinics, and chapels. They worked mostly in rural areas. They were multi-taskers, able to administer in a variety of ministries, serving as nurses, chaplains, teachers, and mechanics. Their influence among young men and women was profound…50

Due to their separation from other Anglo-Americans, their proximity to Cuban poverty, and their focus on ameliorating suffering, rural female missionaries shaped their ministry to serve the Cuban community that surrounded them, which they often embraced as their own.51

Historically, Protestant denominations placed severe limitations on the ability of women to preach from the pulpit. However, isolation and desperation served, ironically, to liberate religious women to a degree from gendered hierarchy and surveillance. Rural women missionaries enjoyed a fair amount of independence from male oversight.52 The isolation of rural female missionaries positioned them for power and influence secured by few North American women of the time.53 Without a male missionary counterpart in Báguanos, Cook preached to her congregation regularly.54

Transformed by their proximity to rural suffering and their ethical foundations, many rural women missionaries in eastern Cuba described with empathy the Revolution’s socio-economic and anti-imperialist origins. In the mid-1950s, Carroll English served as a teacher at the Agricultural and Industrial School in Playa Manteca, a few miles from the United Fruit and Sugar Company mill at Preston. In the mornings, before undertaking her duties at la granja, English ventured to the nearby batey and instructed the children of Cuban cane-cutters. Without the efforts of Methodist missionaries such as English, it is unlikely that these children would have been formally educated at all. The school-day ended at noon and English served as its sole instructor. In her limited time with these children, English sought to expand upon the world they knew by taking them to the UFSC mill at Preston as, “most, if not all, of the students had never been anywhere other than around the batey”.55 This small cane-cutting village and the lives endured by these cane-cutting families contrasted wildly with the luxury enjoyed by Anglo-Americans in Preston.

Witnessing the stark inequities in Cuba influenced English’s understanding of the US presence on the island. English explained, “Americans were often tied into the sugar industry…. President Batista protected those interests to keep himself in power and to keep the companies happy to be there”.56 English argued that Cuban politicians’ prioritization of North American interests served to radicalize the Cubans most marginalized by this arrangement; she explained the path from socio-economic inequality to political unrest:

As long as capitalism can rape the forests and soils and waters of the world, the indigenous peoples will forever be obliged to toil to serve their money-making interests without sufficient compensation to the people of the land. Their experience is of being oppressed with little or no opportunity to share in the wealth that capitalism creates. This feeling of being suppressed makes for revolution.57

Operating on land donated by North American corporations, English and other rural women missionaries in 1950s Cuba became acutely aware of the economic, social and political injustices resulting from foreign influence, aggravated by the priorities of the Batista government in times of revolution (Alexander 2002, p. 143). They grew sympathetic to, and over time engaged with, the politics of revolution.

6. Rural Missionaries and the 1959 Cuban Revolution

…[Surely] you realise there are people who expect to be tortured and others who would be outraged by the idea. One never tortures except by a kind of mutual agreement…. The poor in my own country, in any Latin American country. The poor of central Europe and the Orient. Of course in your welfare states you have no poor, so you are untorturable. In Cuba the police can deal as harshly as they like with émigrés from Latin America and the Baltic States, but not with visitors from your country or Scandinavia. It is an instinctive matter on both sides…One reason why the West hates the great Communist states is that they do not recognise class-distinctions. Sometimes they torture the wrong people…Captain Segura to Mr. Wormhold (Greene 1958, pp. 164–65)

Between 1956 and 1958, female rural missionaries found themselves living in a war zone. Betty Campbell Whitehurst, a Methodist missionary stationed in Báguanos remembers during the last four months of 1958, “There was no mail delivery, the company store soon ran out of food and most other merchandise, and even medical supplies were almost depleted”. Suffering alongside their Cuban students, parishioners and colleagues provoked a revolutionary consciousness among many rural missionaries. Whitehurst explains that in the late 1950s, “The rebels were burning cane fields in an attempt to cripple Cuba’s economy. The Báguanos sugar mill began work, but was producing hardly any sugar, because the cane-cutters were afraid to go into the fields. The army then said it would kill anyone who refused to work, so the workers were forced to go into hiding or join the rebels. Meanwhile, their families were starving” (Whitehurst and Whitehurst 2010). Economic and living conditions deteriorated drastically in large sections of eastern Cuba between 1956 and 1959. Agricultural production dwindled, further crippling the economic stability of many communities. In this context, rural missionaries and Cuban Protestants shared fears and frustrations with the violence and desperation that accompanied their shared realities. Together, they lay the foundations for a “new” Cuba (Ramos 1989, p. 134).

In the late 1950s, Batista’s forces regularly tortured, murdered, and terrorized Cuban pastors, students and parishioners, for both alleged and actual aid to the Revolution. Cubans who participated in rural Protestant institutions belonged to what Graham Greene’s anti-hero Captain Segura referred to as the “torturable class” of Cubans (Greene 1958, pp. 164–165). Stationed in Báguanos Oriente, Betty Campbell Whitehurst memorialized in her diary how expendable her parishioners seemed to Cuban authorities, “Soldiers would go to a house after midnight to arrest someone, take him out and shoot him. The people they killed were ‘the enemies of Batista’—often boys of 16 to 18, usually high school students”. A state of fear gripped the region: “College and high school students were considered revolutionaries, and it was a crime punishable by death to be seen in a high school uniform. The Constitution had been suspended and there was no freedom of speech, press, or assembly…” (Whitehurst and Whitehurst 2010).

On 1 December 1957, the violence reached Báguanos, devastating Whitehurst. Her diary reads: “[We] found the bodies of four missing boys from Báguanos, mutilated but recognizable. After torturing them for a day and half the night, the soldiers shot them…. Big chunks of flesh had been cut off in various places. Knives had been shoved into the front of their arms and pulled out the back…before killing the boys [soldiers] put out their eyes” (Whitehurst and Whitehurst 2010). To Whitehurst, these were not just anonymous victims of Batista’s war against civilians; these were youths whose families she knew well.

Because the Methodist mission in Báguanos directed most of the cultural institutions in a town of close to 1000 people, the families of the victims asked Whitehurst and her fellow female missionaries to deliver the eulogies for three out of the four young men. As a spiritual and educational leader, Whitehurst tried “to console Mongo’s mother and one sister. The other sister was in another house, completely crazed. In every family there is at least one person who has gone crazy”. Whitehurst continued, “I had seen and heard so much that I felt heartbroken” (Whitehurst and Whitehurst 2010).

Word of the horrors of Batista’s rule spread quickly throughout the Anglo-American rural missionary community. Across the Cuban countryside, rural missionaries recognized a pattern of government repression in support of the interests of the state and foreign corporations. Having heard many stories about acts of violence, at the end of 1957 Whitehurst recounted the brutality in her diary: “In Cienfuegos, after a big massacre, people were buried who weren’t even dead yet…. The four who were killed this week in Marcané, between Cueto and Mayarí, were skinned alive, their hands were cut off…” (Whitehurst and Whitehurst 2010).

Far away from the violence and carnage, most of the nearly 10,000 Anglo-American residents of Cuba remained unaware of the horrors of the conflict until the last months of the Revolution. Betty Campbell Whitehurst found the 1958 Methodist Conference in Havana to be “a difficult one, as we were divided into two groups: those loyal to Batista and those affirming the Castro revolution” (Whitehurst and Whitehurst 2010). Her North American colleagues who worked in the male-dominated Protestant institutions in Havana did not know, and could not fathom, the terror Whitehurst described.58

Beyond bearing witness to the suffering and indiscriminate state violence, rural North American missionaries knew and respected many of the participants and leaders of the revolutionary movement, a disproportionately high number of whom were Protestant. Cuban Protestants including Frank País, Rolando Cubela, Oscar Lucero Moya, Mario Llerena, Manuel Ray Rivero and Samuel Salabarría all played significant roles in the struggle against Batista with some assuming high-ranking positions in the Cuban government after 1959. Commander of the Army in the province of Camagüey Huber Matos, Minister of Recuperation of Misappropriated Goods Faustino Pérez Hernández, Minister of Social Welfare Daniel Álverez, Minister of Education Armando Hart, Minister of Interior José A. Naranjo, and Undersecretary of Labor Carlos Varona, all attended Protestant schools or were themselves practicing Protestants.59

American Baptist Kathleen Rounds taught at El Cristo’s Colegios Internacionales where she developed significant relationships with Cubans active in the revolutionary struggle against Fulgencio Batista. The director of Colegios Internacionales, Agustín González became a key figure in the Santiago resistance and a mentor to revolutionary leader Frank País. Rounds also worked for Mario Casanella who presided over País’ funeral in 1957 (Ramos 1989, p. 52). Responding to the assassination of a former Colegios student by Batista’s forces in the late 1950s, Rounds’ students blocked the highway in front of the school (Corse 2007, p. 11). Before 1959, when Rounds read Castro’s name in the paper or heard it from the supportive Cuban citizens of Oriente, she likely remembered her former pupil Agustina Castro, the sister of the rebel leaders Fidel and Raúl, whom she described as “faithful to her evangelical faith” having been baptized at the school.60 The labor, dreams, aspirations and struggles of Cubans gave meaning to the lives of rural evangelizers such as Rounds, especially in times of conflict.61

The experiences and relationships developed by missionaries in eastern Cuba led some to take substantial risks, engaging in subversive activity for what they viewed as a moral imperative. In the late 1950s, Ira E. Sherman protected Cubans threatened by Batista’s authorities by helping a Cuban pastor on a government “death list” escape the country. Sherman subsequently feared for his own safety and sent his family back to the United States in late March 1958. For a time, Sherman himself felt it necessary to hide from Batista’s security forces at the Guantánamo Bay Naval Base, despite his scorn for the exploitative dynamics on and around the base. 62 Even as Sherman challenged US authority in the region, his nationality operated as a shield against reprisals from the Cuban authorities. 63

Rural missionaries’ relationships with anti-Batista activists and their family members humanized the radical visions of revolutionaries. These missionaries became supportive not only of the democratic goals of the Revolution, but also the socio-economic aims of the struggle. The Revolution argued for egalitarianism, as well as educational, health and “moral” initiatives that many missionaries recognized as political extensions of Protestant service projects throughout the island. Unlike more secular elements of the Anglo-American colony residing in Havana and elsewhere, between 1959 and 1960 rural missionaries almost uniformly cheered the overthrow of Batista and the curbing of foreign influence.

7. A Revolution Rooted in Protestant Values

In July 1959, an interdenominational group of Protestant Cuban youths composed a letter in English addressed to the US President, Congress, the State Department, and the US Ambassador to Cuba articulating their shared vision of a Christian revolution: “The pillars that will sustain this building are: politically—Freedom and democracy; economically—Land Reform and Industrialization; Socially—To redeem the poor people and applying the Christian principles of social justice”.64 The Cuban students ridiculed the hypocrisy and “false Christianity” of landowning elites who would claimed religious ethics, while ignoring rural suffering. They linked Latin American radicalism to US imperialism, and honored revolutionary values as Protestant: “…being Protestants, how could we keep from backing this revolution if, as a consequence of it, the moral standards of the country have been raised?... Cuba may be and appear before the world as a nation where dignity, democracy, freedom, justice and love prevail”.65

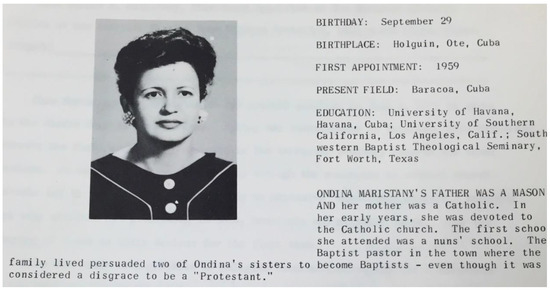

Figure 5.

Ondina Maristany Cervantes.66

Figure 5.

Ondina Maristany Cervantes.66

The discursive linkage of Protestant values and revolutionary demands could be heard from Cuban Protestant leaders as well. Ondina Maristany graduated from Colegios Internacionales in 1941 and by the late 1950s became a leader in the American Baptist Church in Cuba (See Figure 5). Similarly to other Cuban Protestant leaders, Maristany was very well educated in Cuba and the United States.67 She taught Faustino Pérez, a revolutionary leader and a Protestant.68 After 1959, Maristany embraced the intertwined missions of the Revolution and the Baptist church. Southern Baptist Superintendent Herbert Caudill praised Maristany’s ambition to fulfill the goals of the Revolution through missionary work in Oriente in May 1959: “Naturally she has been greatly interested in the political situation in Cuba, and since the change of government she has felt called to the Sierra Maestra…. She is interested in doing something to improve the backward educational and social condition in the Sierra Maestra. She has definite convictions about what she wants to do and I believe she can be useful to the work in Oriente”.69

The ambitions of North American missionaries for moral, economic and political change developed within the same spaces that inspired the solidarity of Cuban Protestants engaged in the Revolution. These transnational religious communities embraced a vision of Cuban political autonomy, economic redistribution and moral clarity. While US corporate and political leaders grew alarmed by the Revolution’s demands, rural missionaries followed the lead of Cuban Protestants, promoting policies pursued by the new Cuban government including mandates to curb the influence of foreign corporations, regulate the tourism industry, and redistribute resources to disenfranchised Cubans.

In early 1959, officials in Washington, the US press and other elements of the Anglo-American colony decried the executions of Batista’s officials. Importantly, rural missionaries responded boldly to these charges of revolutionary brutality. They contextualized the Revolution’s use of capital punishment by exposing the violence of the Batista years. After seventeen years in Cuba Methodist missionary, Christine Stout Evans wrote in February 1959, “I don’t believe in capital punishment…but what else would you have done with men who have caused so much torture and misery?” In February 1959, American Baptist Secretary Wilbur Larson challenged the double standard at play: “The trials and executions of those responsible for atrocities under the old regime have been given wide publicity. However, the atrocities for which they are being punished were not given this publicity and are not now being given publicity”.70 Larson admonished US officials: “The people of the United States were in no moral position to express any kind of judgment on the activities of the new government since they had said nothing about the atrocities of the Batista regime”.71

Because of their experiences with US influence in Cuba, rural Protestant missionaries understood and anticipated the rise of anti-US sentiment in ways that other Anglo-Americans could not. In 1959, Edgar Nesman warned that while US individuals are warmly welcomed, “official US government policy, which includes all business and military associations, is not considered at all in friendly terms…. The primary cause of this feeling appears to Cubans to be that our foreign policy is based to a degree on self-interest and run by big business and the military”.72 Morrell and Lois Robinson, a Methodist missionary couple based in Mayarí, Oriente, lambasted US officials for their “callous indifference to the terror and death that stalked our cities and towns for six long years” during the Batista government.73

Throughout 1959, frustration with Washington swelled among rural missionaries, as US officials demanded that revolutionary leaders temper their restructuring of Cuban society. Founder of the Agricultural and Industrial School, John Edgar Stroud, explained, “We must remember that much of the land in Cuba has been owned by United States corporations that have made…four times what they could make in this nation because of cheap labor and taxes. When the much talked ‘land reforms’ were enforced our American economic concerns have not been able to take it”. Comparing the Cuban experience to a US-sponsored initiative to redistribute property in Japan after World War II, Stroud wrote, “Didn’t McArthur introduce land reforms in Japan? We didn’t fuss there because American Companies did not own land…”74 These missionaries and religious educators were quick to expose the hypocritical North American denunciation of executions, land reform, and the socio-economic transformations underway.

As the revolutionary policies reflected Protestant goals, many rural missionaries viewed the Revolution as an extension of their educational, agricultural, and moral work in Cuba. Richard Milk noted, “The earliest major revisions of the educational program by the Revolutionary government seemed ‘right down our alley.’”75 Edgar Nesman lauded plans for a self-sustaining Cuban agricultural system: “[Diversification] of agriculture is a partial solution. Our school has been stressing this from the beginning…[diversification] is one of the major aspects of the agrarian reform laws. Castro and his government would like to see increased production of rice, corn and eggs eliminate the importation of these items”.76 Methodist missionary Ira Sherman concluded that the Naval Base at Guantánamo had crippled the non-service-oriented economies of Caimanera and Guantánamo, ripening those communities for sexual exploitation by US naval personal. Decades after leaving Cuba, Sherman noted with satisfaction that the revolutionary government made a “successful effort to wipe out prostitution and to train the women involved in it in some other ways of earning a living”.77 For many missionaries, the Revolution was an embodiment and extension of their teachings.

8. Aftermath

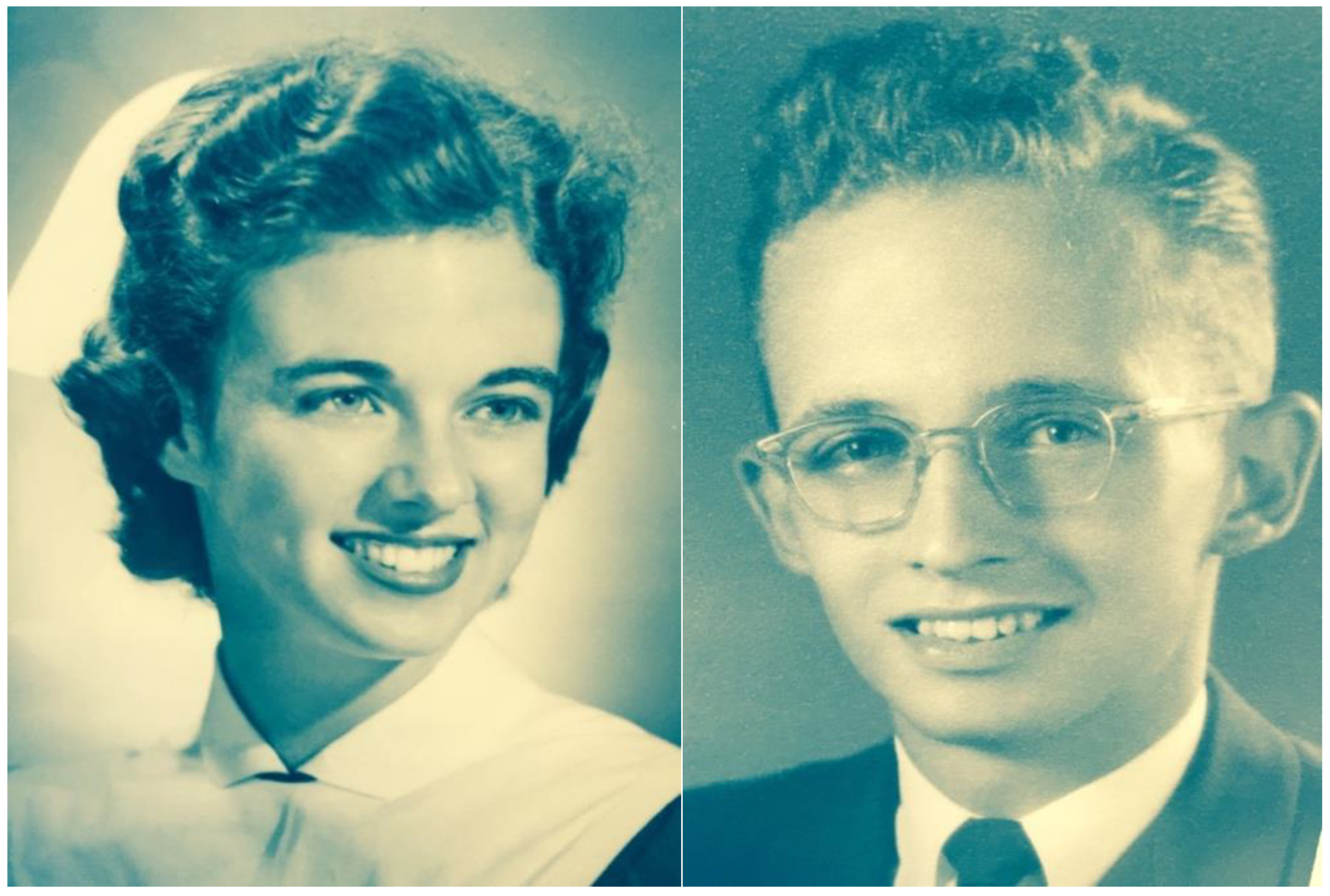

Arriving in the mid-1950s, Lois Robinson served the Methodist Churchwell Clinic in Mayari, Oriente, responsible for tending to the sick, malnourished and injured. Her husband Morrell served as pastor of the Methodist Church in the midst of a war zone. In 1960, having experienced the Revolution and the nationalist fervor in its aftermath, the Robinsons began to reflect on their complicity in maintaining ethnonational and religious imperialism (See Figure 6). They decided to leave the island. In a letter to his superior James Ellis, Morrell Robinson wrote

I’ve been struggling with decisions concerning our future relations to work here…. [A]side from present nationalism, I doubt that the Cuban church needs what we can offer it. I feel that a missionary, in order to warrant his presence in another country, must be able to contribute something that possibly no other national might contribute at that particular time. He should be an expert in some line or pioneer in some field. Unless he can do that, he is competing with national pastors with the cards stacked against them for their salary is much lower and he often does not have access to funds from the states.78

Figure 6.

Lois and Morrell Robinson.79

Figure 6.

Lois and Morrell Robinson.79

The concerns of the Robinsons over the imperial legacy of Protestant missionaries challenged the self-assured logic of benevolence long held by Anglo-American religious institutions in Cuba and back in the United States. Living through the terror of war, working in close proximity to Cuban suffering, and exposed to intimate lessons about the devastating consequences of nationalism, capitalism and imperialism, missionaries struggled with their purpose, complicity and legacy. Many vocally rejected Cold War narratives being spun by US policymakers.

In 2016, when I asked Methodist missionary Betty Campbell Whitehurst, “What led to your disillusionment with the Cuban Revolution?” she answered: “I was never really disillusioned; the Revolution was doing wonderful things”.80 When her missionary term expired in 1959, Whitehurst returned to her childhood home of Lemesa, Texas. There she found a town segregated into by race, divided into white, black and Mexican-American sections. At the time, Whitehurst and her former Cuban student from Báguanos, Ceferino Pavón had planned to reunite and marry, but Cold War tensions developing between Havana and Washington undermined their plan. Whitehurst settled in as a teacher in Lemesa’s school for Mexican-American children as the only staff member who spoke Spanish. “I was back in very familiar territory, but I now saw it with different eyes”.81

When Sara Fernández, the Mexican-American Methodist missionary from Texas first arrived in Omaja, Cuba, she found a community impoverished–without drinking water, schools, clinics, or jobs.82 Fernández created cultural institutions, resembling those operated by Cook and Whitehurst in Báguanos. Respected and accepted by the Cuban community of Omaja, Fernández chose not to return to Texas after the Revolution, where she would resume her status as a second-class citizen. She chose, instead, to continue her work in a new context where her service-oriented goals were being prioritized by the Cuban government. It was not until 1963 that she permanently left the island, working first with Cuban refugees in Miami and then returning to missionary work in Costa Rica. After years in Cuba, Whitehurst and Fernández came to view both the Revolution and the United States with a new critical lens.

Over time, the majority of foreign missionaries and many of their Cuban counterparts grew frustrated as the Revolution increasingly positioned religion as an obstacle to radical social change. By the mid-1960s the revolutionary government would persecute those who could not or would not adjust to the new order, placing religious leaders, homosexuals, counterrevolutionaries and other “anti-socials” in labor camps under the Unidades Militares de Ayuda a la Producción (UMAP) program. It was in this context that US Protestant organizations transferred power to their Cuban counterparts.

For Cuban Protestants, the original benefits garnered from their association with North Americans and access to foreign capital morphed into a burden by the mid-1960s. Cuban Methodists became independent of US Methodists in 1968, according to Bishop Armando Rodríguez, “at the worst possible moment”. Rodríguez argued that propaganda efforts by the Cuban state sought to undercut religious authorities. By claiming religion to be the opiate of the masses, across a number of media platforms, the Cuban government framed socialism as the path to spiritual liberation. During this period, Cuban pastors were often accused of working for the CIA, which had been attempting to overthrow the government since the start of the decade. These developments led to an exodus of the Cuban Methodist leadership and a decline in the number of Cubans who identified as Protestant. Close to 90 percent of Cuban Methodist pastors fled Cuba, most to the United States. In 1959, the Methodist denomination claimed 11,000 members. By 1968, 3000 remained.83 The Protestant identity that garnered material and social advantages before 1959 now carried the risk of imprisonment. Cuban Protestants often found themselves buried in the rubble as preexisting value systems and socio-economic hierarchies were demolished by the Revolution.

9. Conclusions

Despite their entanglements with US capital, many rural Anglo-American missionaries living and laboring in Cuba mobilized their status as privileged outsiders to shield Cuban revolutionaries from Batista’s forces. They challenged the local and transnational narratives forwarded by Batista, foreign corporations, and counter-revolutionary forces that framed the Revolution as illegitimate. Rural foreign missionaries often worked in concert with Cuban revolutionary leaders, who were their former students and parishioners, fellow pastors and Protestant teachers. They undertook an unofficial letter-writing campaign to turn Anglo-American opinion against Batista, and later to defend the early actions of the revolutionary government. After 1959, as their government and foreign corporate benefactors attempted to destabilize the Cuban revolutionary government through economic, political and military sabotage, many rural missionaries followed the lead of Cuban Protestants in championing the new government’s early policies. Missionaries of eastern Cuba, and especially the region’s women missionaries, bore witness to Cuban desperation and suffering and were inspired by the Revolution’s political and socio-economic goals.

While Cuba’s self-titled “Anglo-American colony” relentlessly reproduced foreign influence through Cuba’s Anglo-American-controlled businesses, social clubs, schools and segregated institutions, as well as through relationships with Cuban powerbrokers, the archival materials and oral histories introduced in this article reveal important counter narratives about solidarities forged in struggle. By nature of their proximity to suffering and intimate relationships with impoverished Cuban and Caribbean families, rural foreign missionaries on the island became advocates for revolution, and for those disenfranchised by the existing order.

Cuba’s most marginalized communities altered the identities of missionaries, who were often sponsored by foreign corporations to develop a malleable and efficient workforce. In interviews, diaries, letters, memoirs, and recent online exchanges, former missionaries detailed the hardship faced by Protestants persecuted under Batista, as well as those who were subjected to the tortures of the Unidades Militares de Ayuda a la Producción (UMAP) program in the mid-1960s. While the former rural missionaries interviewed for this project expressed different degrees of disappointment over the lack of “democratic reforms” instituted in Cuba since 1959, all praised the early socio-economic policies of the Revolution. They viewed the revolutionary government’s material redistribution and nationalization of foreign property as an extension of their own spiritual and ethical work. Ironically, and with pain, they embraced the very policies that led to their expulsion.

Funding

This research was funded by the following awards and fellowships: Mellon Dissertation Award, University of North Carolina, Institute for the Study of the Americas (2017). Cuban Heritage Collection Fellowship, University of Miami, Goizueta Foundation (2016). Florence Ellen Bell Scholar Award, United Methodist Archives and Historical Center (2015).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Original data collected by the author and used for this article can be accessed at Cuba’s Anglo-American Colony in Times of Revolution (1940–1961): A Digital Archive.

Acknowledgments

Seventy-seven oral histories were collected for this project, yet that number would have been fewer than twenty if not for the incredible contributions of Carroll English and Chris Baker. Carroll English opened a network of former missionaries in Cuba and Cuban Protestants that added texture to this article through their oral testimonies, as well as their contributions of letters, diaries, memoirs, and photos. I want to thank Louis A. Pérez, Jr. who molded in me the values of scholarship necessary to pursue this project. Further, I want to thank my father who nurtured my appreciation of history throughout my academic life. My mother made this piece possible by repeatedly offering ideas and suggestions with unwavering positivity. Finally, I want to thank my wonderful partner and editor extraordinaire Alyssa Bowen, and my incredible daughter Rosie Akennsey, both of whom encouraged me throughout this process.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Eulalia Cook to Miss Marion Derby, ‘Missionary’s Annual Report—1958’, United Methodist Archive and Historical Society (hereafter UMAHS), Drew University, Madison, NJ, Board of Missions—New York City, 1189-2-1.29. |

| 2 | US corporations hoped to secure substantial investments in the Cuban economy by sponsoring foreign-managed schools, churches and clinics. These cultural institutions provided Cuba’s Anglo-American executives the social and religious comforts they expected as privileged outsiders. Further, they prepared a Cuban workforce for US companies by training Cuban and Caribbean students in Anglo-American ways of thinking, communicating and working. Finally, they created opportunities for socio-economic partnerships between Anglo-American and Cuban professionals who would become fluent in English and comfortable with Anglo-American norms. Cubans educated by US nationals, and to a lesser degree by Brits and Canadians, became personally invested in cultivating the authority of Anglo-American knowledge and culture as their own elevated position in Cuban society depended on the persistence of foreign influence, which they were trained to accommodate. Thus, many Cubans became eager to participate in the “development” of their nation by acquiring foreign skills-sets that would enhance their financial and social prospects. Cubans from a range of socioeconomic backgrounds enthusiastically enrolled themselves (or their children) in institutions managed by Anglo-Americans. Most of these influential cultural institutions were affiliated with a diverse assortment of US Protestant traditions. Missionaries thereby played a crucial role in attempts to reproduce and normalize US imperialism. (Crahan 1978; Vega-Suñol 2004; Yaremko 2000); Samuel Finesurrey, Cuba’s Anglo-American Colony in Times of Revolution (1952–1961), Unpublished Dissertation, University of North Carolina, (Chapel Hill, NC: Carolina Digital Repository, 2018). |

| 3 | The term Anglo-American will be used throughout this article because English speaking Caucasians from the US, UK, and Canada considered themselves a cohesive community on the island. The North American and British administrators of mostly US corporations in Cuba, along with their families made up a vast the majority of the Anglo-American population on the island. The 1953 Census indicates that in the province of Oriente, around which this article focused, only 39 Canadians established residence. British subjects in the region totaled 7047, including low-paid black labor from the British Caribbean. At this time, there were 1624 US nationals in the region of Oriente—close to a quarter of the total US residential community on the island (6503). On the entire island, there were 272 Canadians and 14,421 documented British subjects in total (Oficina Nacional de los Censos Demográfico y Electoral 1953). |

| 4 | There is a significant divide in the ecumenical and evangelical missionary traditions. The ecumenical denominations, which are the focus of this article, worked to address the social needs of those they served, while the evangelical communities centered their attention on conversion to save the souls. |

| 5 | Hollinger is certainly not alone in showing the influence of missionaries and Protestantism more generally over the foreign policy of the United States. Andrew Preston’s significant work, The Sword of the Spirit, Shield of Faith exposes that Protestant influence over US foreign policy remained consistent throughout US history. (Preston 2012). |

| 6 | A shared hatred for the Catholic Church between Protestants and Free Masons led to an “unofficial alliance” between the two groups with many early Cuban pastors being active Masons. The tensions between Catholics and Protestants would last until the overwhelmingly Spanish clergy began being replaced by French Canadians. Far more comfortable with Protestants, especially those from the United States and Canada, relations between the two groups improved after the arrival of the North American clergy. (Ramos 1989, pp. 37, 45). |

| 7 | While before 1898 Cubans became pastors and leaders in Protestant institutions, Spanish priests still filled the ranks of the conservative Catholic Church in Cuba. (Pérez 1999, p. 255). |

| 8 | Louis A. Pérez explains, “The Protestant call for religious freedom complemented the Cuban demand for national independence, and increasingly one became the extension of the other: Cuban anti-Spanish politics generalized easily to anti-church sentiments, and Protestant anti-church sentiments expanded naturally to anti-Spanish views”. (Pérez 1995, p. 58). |

| 9 | Provided by Rafael Manuel Rábade Guntin. |

| 10 | By the 1950s, most foreign corporations supporting Anglo-American missionaries—just as most, though not all of the missionaries themselves—came from the United States. In 1939 Canadian enterprises held ten sugar mills in Cuba and English entities held four. Meanwhile, US capital held sixty-six. By 1959, the increase in Cuban control of sugar production meant no sugar mills were held by countries of the British Commonwealth, and only 39 belonged to US capital. (Nelson 1972, pp. 61–62). |

| 11 | United States Bureau of Foreign Commerce, American Republics Division, ‘Investment in Cuba: Basic Information for United States Businessmen’ (Washington: US Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign Commerce, 1956), 9–10, 35, Cuban Heritage Collection (CHC), University of Miami. |

| 12 | ‘US Investment Tops 800 Million’, Times of Havana, 17 April 1958, 4. |

| 13 | Eulalia Cook González, ‘El trabajo rural de la iglesia Metodista en Cuba, 1940–1960’, 28 November 1998, 1, provided by (Yaremko 2000, pp. 11–12). |

| 14 | Eulalia Cook to Elizabeth Lee, 17 June 1942, UMAHS, Drew University, Madison, NJ, Missionary Files, 1189-2-1.26; Cook González, ‘El trabajo rural de la iglesia Metodista en Cuba, 1940–1960’, 28 November 1998, 13; Betty Campbell Whitehurst, interview by author, 1 September 2016, Telephone. |

| 15 | Eulalia Cook Gonzaléz, ‘Reasons for Growth in Báguanos, Cuba, 1952’, in Eulalia Cook González, ‘El trabajo rural de la iglesia Metodista en Cuba, 1940–1960’, 30, provided by Edgar Nesman; Eulalia Cook to Elizabeth Lee, 22 September 1948, UMAHS, Missionary Files, 1189-2-1.26. |

| 16 | Eulalia Cook to Emmeline Crane, 3 May 1950, UMAHS, Missionary Files, 1189-2-1.26; Eulalia Cook to Elizabeth Lee, 12 December 1944, UMAHS, Missionary Bio Files, 1470-3-1.45. |

| 17 | Richard Milk to Dr. A.W. Wasson, 7 November 1946, UMAHS, Microfilm Roll 341. |

| 18 | Robert Milk, the son of former school director Richard Milk, remembers the lease to be around a dollar per annum. Robert Milk, interview by author, 8 September 2016, Telephone; ‘Escuela agrícola e industrial, Cuba’s Only Private Vocational School for Rural Youth: Progress Report for the First Ten Years’, provided by Carroll English; Richard Milk to Dr. A.W. Wasson, 7 November 1946, UMAHS, Microfilm Roll 341; Fundraising Pamphlet, ‘Agricultural and Industrial School’, UMAHS, Microfilm Roll 341. |

| 19 | Seen note 17 above. |

| 20 | Provided by Robert Milk. |

| 21 | Fundraising Pamphlet, ‘Agricultural and Industrial School’, UMAHS, Microfilm Roll 341. |

| 22 | Richard Milk, ‘An Evaluation of the Education Offered at The Escuela Agrícola e Industrial of Preston’, March 1959, provided by Carroll English. |

| 23 | Darryl Rutz, interview by author, 17 October 2016, Miami, FL; Edgar Nesman, ‘Memoir’, 32, provided by Edger Nesman. |

| 24 | A town settled by US Methodists at the start of the twentieth century, Omaja served as a center for rural work under the guidance of Mexican-American missionary Sara Fernández. UMAHS, Missionary Files: 1912–1949, Microfilm Roll 338; (Leuenberger 2013). |

| 25 | Richard Milk, ‘Cuba Testimony’, 32, provided by Carroll English. |

| 26 | Emily Towe, ‘Expansion in Cuba’, World Outlook 37, no. 2 (February 1947), 5. |

| 27 | ‘Escuela agrícola e industrial, Cuba’s Only Private Vocational School for Rural Youth: Progress Report for the First Ten Years’, provided by Carroll English. |

| 28 | Despite occasional setbacks, the school seems to have mostly gotten its way. Milk wrote, “In general, the board concerned itself almost entirely to broad policies and to financial matters. The development of specific educational, extra-curriculum, and religious plans they left to the faculty under my direction”. Richard Milk, ‘Cuba Testimony’, 21, provided by Carroll English. |

| 29 | Edgar Nesman to author, 14 September 2016, Email. |

| 30 | Robert Milk, interview by author, 8 September 2016, Telephone. |

| 31 | David A. Hollinger exposes that globally women represented around two-thirds of all Protestant missionaries from the United States. (Hollinger 2017, p. 7) |

| 32 | After reading Davis’ work the year it was published, Methodist missionary Maurice Daily reflected critically upon earlier Methodist evangelizing efforts, “We have tried to save individuals without interpreting adequately…what that salvation means in terms of their own community life…. They are in the community and incidentally in the Church; they should be in the church so as to live purposefully in the community”. Maurice Daily to Dr. A.W. Wasson, June 26, 1942, UMAHS, Microfilm Roll 338; (Davis 1942, p. 8). |

| 33 | Missionary F.A. Flatt explained, “Now after reading Dr. Davis’ book I am more impressed with our need for a rural program”. FA Flatt to Dr. A.W. Wasson, 14 May 1942, UMAHS, Microfilm Roll 338. |

| 34 | Both Candler College (Methodist, Havana) and La Progresiva (Presbyterian, Cárdenas) were ranked in the top ten high schools on the island serving children from middle class and wealthy Cuban families. (Ramos 1989, p. 36). |

| 35 | ‘Kathleen A. Rounds’, 9 September 1962, American Batista Home Mission Society (hereafter ABHMS), Mercer College, Atlanta Georgia, 340-1; ‘Kathleen A. Rounds’, 23 August 1963, ABHMS, 340-1; (Corse 2007, p. 4). |

| 36 | As with their access to foreign capital, access to volunteer labor from foreigners boosted the stability and prestige of Anglo-American mission projects. Peter I. R. Skanse, ‘The Rural Betterment Campaigns of the Eastern Cuban Baptist Convention’, Eastern Cuba Baptist News 2 (March 1955), 3. Hoping to gain recruits to work for the Methodist projects of eastern Cuba, Pastor John Stroud requested short-term Christian recruits, explaining, “Activities will include the teaching of classes in Bible, health, canning and food projects, and the manual work of road repair, improvements for the local school, building a church…”. ‘Four Work Camps Planned for Methodist Students’, World Outlook 37, no. 7 (July 1948), 46–47. |

| 37 | Conversation with United Methodist Archivist L. Dale Patterson, 25 August 2017, Telephone; (Ramos 1989, pp. 31, 34). |

| 38 | While American Baptists and Quakers arrived in rural eastern Cuba at the turn of the century, the Methodist Episcopal Church, South limited their rural service activities until they united with the northern Methodist Episcopal Church in 1939. At the turn of the century, Southern Methodists established influential religious and educational institutions in western Cuba. A dedication to the most impoverished elements of Cuban society, however, would not emerge until later. The Methodists split over the issue of slavery in the mid-1840s. Before reunification, the two Methodist traditions developed along divergent paths. Southern Methodists dedicated themselves to spreading the gospel through evangelism, and northern Methodists prioritized service projects in the realms of health, education, and agriculture. Following the War of 1898, they divided Spain’s former colonies between themselves. Cuba was allocated to the Methodist Episcopal Church, South while the northern Methodist Episcopal Church acquired Puerto Rico. The Methodist mission to Cuba seems to have been reinvigorated with unification in 1939. World War II and the post-war mentality that framed North Americans as “protectors of the free world” further catalyzed the new Methodist commitment to rural development projects. Of the estimated 225 foreign Protestant missionaries in the country, the 38 Methodists may have represented the largest foreign presence for a Protestant denomination on the island in the late 1950s and early 1960s. At this time the Methodists introduced themselves to a new, poorer and darker audience in eastern Cuba. Lawrence Rankin, the son of Methodist missionaries Victor and Kathleen Rankin based in Camagüey, explains unification led to “a more global theology toward missions”. His father Victor Rankin chronicled the theological evolution of the Methodist commitment to structural transformation; Methodists, according to Rankin, came to Cuba during the 1940s and 1950s “to train Cubans, while eliminating dependency, promoting financial independence, and self-sufficiency”. This new emphasis on rural service reinvigorated the foreign character of the Methodists, while other denominations were pursuing greater dependence on Cuban workers by the 1940s and 1950s. (Hart and Meuther 2007, p. 150); Conversation with United Methodist Archivist L. Dale Patterson, 25 August 2017, Telephone; ‘History of the Methodist Church in Cuba’, provided by Edgar Nesman; (Ramos 1989, pp. 27, 34, 71); Lawrence A. Rankin, ‘Early Methodism in Cuba–Towards a National Church, 1883–1958’, provided by Lawrence Rankin; ‘History of the Methodist Church in Cuba’, provided by Edgar Nesman; (Ramos 1989, p. 71); (Yaremko 2000, p. 3). |

| 39 | (Farber 2006, pp. 20–21); Agrupación Católica Universitaria, Encuesta de trabajadores rurales, 1956–57, reprinted in Economía y desarrollo (La Habana, Cuba: Instituto de Economía de la Universidad de la Habana, July–August 1972), 188–212; (Ibarra 1998, p. 162). |

| 40 | Seen note 20 above. |

| 41 | Betty Burleigh, ‘Half a Century in Cuba’, World Outlook 34, no 5 (May 1949), 9. |

| 42 | Emily Towe, ‘Expansion in Cuba’, World Outlook 37, no 2 (February 1947), 5–7. |

| 43 | Edgar Nesman, ‘Memoir’, 7–8, provided by Edger Nesman. |

| 44 | Though Mayarí stood near to the domain of the United Fruit and Sugar Company, the town of 70,000 in the late 1940s, was considered a “free town”, or not on UFSC land. The Methodist Churchwell clinic could refer the seriously ill to the nearby United Fruit and Sugar Company hospital in Preston where several clinic patients would be treated each year, free of charge. The Anglo-American-run Mayarí clinic served as a gatekeeper, and an advocate, for Cuban children in need of medical assistance at the UFSC hospital. Staff of Agricultural and Industrial School to Mr. and Mrs. W.D. Carhart, 22 September 1948, UMAHS, Microfilm Roll 341; ‘Facts about the Churchwell Dispensario Infantil 1949’, UMAHS, Microfilm Roll 341; Betty Burleigh, ‘Half a Century in Cuba’, World Outlook 34, no. 5 (May 1949), 9. |