Recasting Paul as a Chauvinist within the Western Text-Type Manuscript Tradition: Implications for the Authorship Debate on 1 Corinthians 14.34-35

Abstract

:34 the women should keep silence in the churches. For they are not permitted to speak, but should be subordinate, as even the law says. 35 If there is anything they desire to know, let them ask their husbands at home. For it is shameful for a woman to speak in church.

36 What! Did the word of God originate with you, or are you the only ones it has reached?

-1 Corinthians 14.34-36, RSV, 1946.

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Whose Paul Is It Anyway?

2.2. A Brief Note on Verse Partitions

2.3. Multiple Independent Derivations of the Q/R Hypothesis

2.4. English Translation Issues

3. The Earliest Witnesses to 1 Corinthians Never Mention 14.34-35

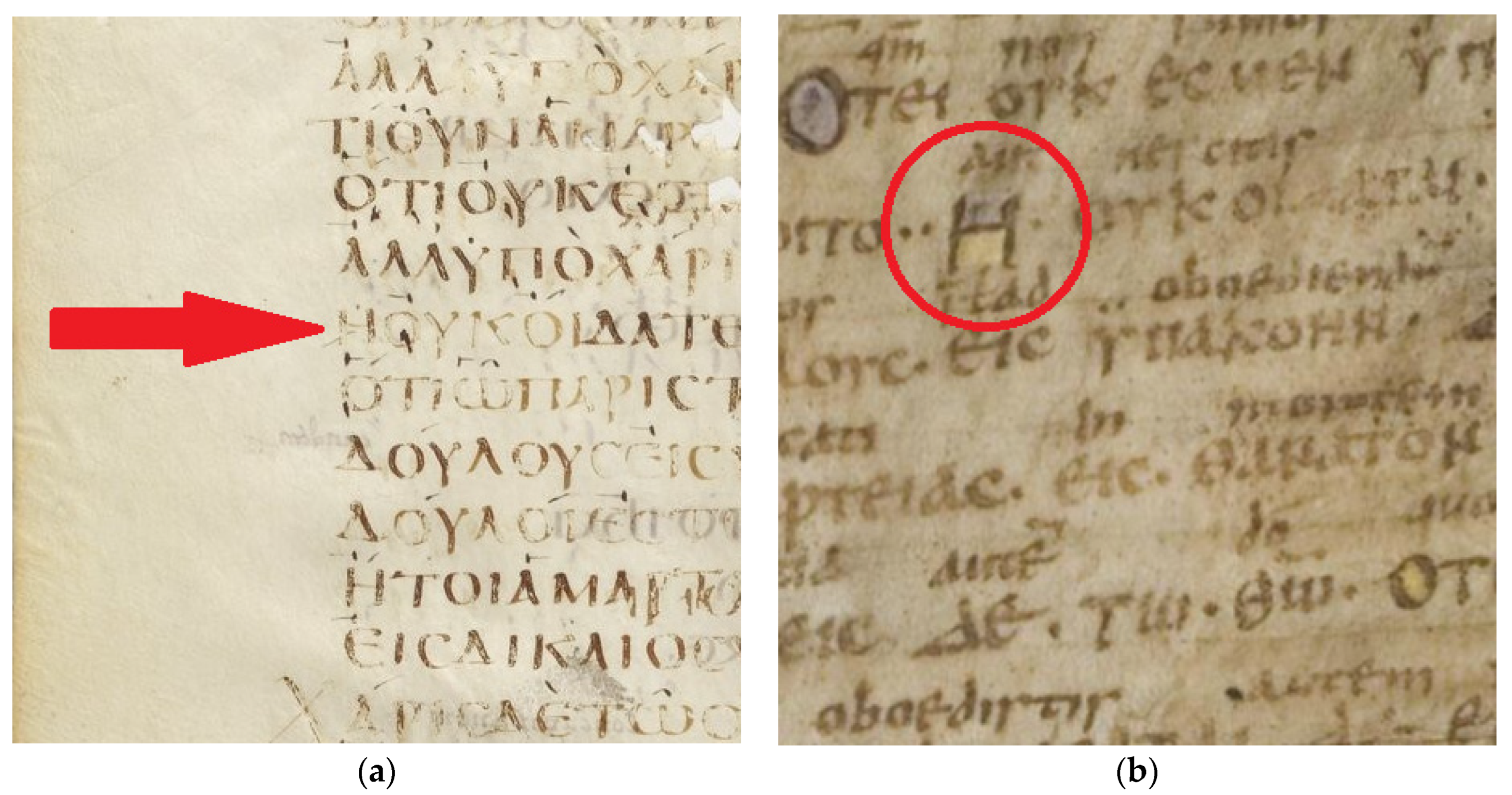

The impressive range, age and variety of witnesses which place the verses after v.33, plead in favour of the originality of this sequence. The witnesses for the alternative sequence (vv.34-35 after v.40) are not only rare, but, more importantly, exclusively “Western”.

4. The Importance of “the Pastor” and 1 Timothy

5. Tertullian vs. Marcion: Discrepant Early Readings of vv.34-35?

Clement [of Alexandria] and the Apostolic Fathers before him knew that 1 Cor 14:34–35 was not Paul’s position but was a quotation of the Corinthians’ position that Paul proceeded to refute. So of course they did not cite 1 Cor 14:34–35 as authoritative.

Tertullian was so determined to deny Christian women the right to teach or baptize that any scriptural text that would support this kind of claim would necessarily be, in his opinion, false, a forgery perpetuated by a poorly-advised and deceitful author.

…when enjoining on women silence in the church, that they speak not for the mere sake of learning (although that even they have the right of prophesying, he has already shown when he covers the woman that prophesies with a veil), he goes to the law for his sanction that woman should be under obedience. Now this law, let me say once for all, he ought to have made no other acquaintance with, than to destroy it.

None of our sources point out any omissions or significant variants in the text of 1 Corinthians found in the Apostolikon. In fact nearly every section of the letter finds mention, and the sequence of Tertullian’s remarks prove that Marcion’s text had the same order as the catholic one. Therefore, the evidence of the Apostolikon does not support any hypothesis that the letter is a composite, or originally had a different order, or has substantive interpolations.

6. Answering Philip Payne’s Objections to the Q/R Hypothesis

Given the view of women that was becoming common among western Christians in the end of the second century, the interpolation of verses 34 and 35 from the location at 33/36 to the end of verse 40, would bring the text in line with emergent orthodox gender convictions. […] So placed, the reader is led to assume that the subordination and silence of women are expressive of the decency and order which Paul asserts is proper in worship.

| Biblical Reference | Western Text-Type Redaction/Corruption Summary | Manuscript Witness * | Scholarly Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acts 1.14 | Women are not mentioned as an independent group but are only identified as the wives of male apostles. | (Dea/Unical 05) | (Witherington 1984) |

| Acts 16.13-15 | Lydia’s group of women are implied to be pagans (not God-Fearers). They are not necessarily introduced within a synagogue context. | (Dea/Unical 05) | (Epp 1966, pp. 89–90) |

| Acts 17.4, 17.12, 17.34. | Prominent women are reduced in status to wives of male apostles. Men’s status is elevated. A woman (Damaris) is deleted. | (Dea/Unical 05) | (Witherington 1984) |

| Acts 18 (Numerous verses) | Aquila (husband) is transposed prior to Priscilla (wife) in most cases. Aquila’s name alone is interpolated in v.3. Aquila’s prominence is raised above that of Priscilla’s. | (Dea/Unical 05) (gig/Codex Gigas) | (Ropes 1926, p. 178) |

| Romans 16.3-5 | Verse 5a is displaced prior to verse 4, so that Paul praises the entire congregation for “risking their necks” for him, thus reducing the prominence of Priscilla and Aquila. | (Dp/Unical 06) (Fp/Unical 010) (Gp/Unical 012) | (Abbott 2015, p. 128) |

| Romans 16.7 | A conjunction and article is adjusted to limit the esteem of the apostles Andronicus (a man) and Junia 15 (a woman), by expanding Paul’s praise “in Christ before me” to the other apostles. | (Dp/Unical 06) (Fp/Unical 010) (Gp/Unical 012) | (Abbott 2015, p. 130) |

| 1 Corinthians 14.34-35 | Verses 34-35 are disjoined from Paul’s critical response at v.36 and sheltered after v.40. The mandate for women’s silence thus stands unchallenged at the conclusion of the chapter. | (Dp/Unical 06) (Fp/Unical 010) (Gp/Unical 012) | (Odell-Scott 2000) |

| Colossians 4.15 | Nympha, proprietor of the house-church in Laodicea, is changed from a woman to a man. | (Dp/Unical 06) (Fp/Unical 010) (Gp/Unical 012) | (Witherington 1984) |

7. Discussion: The Enduring Influence of the Western Displacement

8. A Note of Caution against Anti-Judaic Bias

Hellenistic moralists, from the time of Aristotle, taught that some virtues were appropriate for men, others for women. … In such a Hellenistic society, it was important that the Pastor have something to say about the qualities of women who would serve in God’s household.

9. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Quoted by Levine (2015, p. 9). |

| 2 | Henceforth all verses mentioned without book/chapter designations are presumed to be from 1 Corinthians 14. |

| 3 | See 2 Peter 3.16 on early Christian awareness of discrepant readings of Paul. |

| 4 | Complementarian exegetists demand a gender-neutral reading of the masculine plural pronoun to ensure Paul doesn’t exclude women from his rebuke. Conceding this, a subtle shift in audience remains explicit. Greek masculine pronouns must imply the presence of some males. English gender-neutral pronouns need not include any males. |

| 5 | Acts of Paul was regarded as orthodox by Hippolytus of Rome (c.170-235 CE) and listed in the canon of Codex Claromontanus (Dp/Unical 06) alongside a complete Western text-type of the Epistles. |

| 6 | William Richards (2002, pp. 208–9) posits 1 Timothy was written by an author emulating both 2 Timothy and Titus. |

| 7 | “I permit no woman to teach or to have authority over a man; she is to keep silent.” 1 Timothy 2.12, NRSV. |

| 8 | The oldest epistolary codex, 𝔓46 (c.175-225 CE) lacks 1 and 2 Timothy and Titus, but includes vv.34-35 in canonical verse order. The oldest manuscript of 1 Timothy, 𝔓133 (c. third century CE), includes fragments of chapters 3-4 (Shao 2016). Both 𝔓46 and 𝔓133 have distinct affinities with the Alexandrian text-type. |

| 9 | The Western text-type manuscript tradition is multilingual (witnessed in Greek, Latin, and Syriac). Bilinguals often show complex interdependence between Latin and Greek. Early scribes and editors used multiple languages. |

| 10 | Clement of Alexandria (c.150-215 CE) acknowledged that women deacons served as co-ministers with men during the apostolic era (Stromata 3.6.53.3-4; Wilson 1869, p. 109). His interpretation of 1 Timothy 3.8-13 was more egalitarian than his successors’ interpretations. But he was not egalitarian with respect to marriage and household order (Reydams-Schils 2012). His writings can thus be selectively cited to support both complementarian and egalitarian arguments. |

| 11 | In addition to the displacement of vv.34-35, Antoinette Wire (1990, p. 152) notes that “woman” [γυναικὶ] is pluralized [γυναῖκας] in the Western text-type of v.35, matching the previous verse 34, but also reflecting a pattern associated with the distinctly domestic concerns of several deutero-Pauline texts (including 1 Timothy 2.9 and 3.11, e.g.). |

| 12 | Tertullian wrote over the course of approximately two decades. His uncompromising stance against women in Christian authority is characteristic of the early orthodox phase of his career, while his later writings in the rigorist-charismatic Montanist sect are characterized by a notable softening of several of these positions (Carnelley 1989, p. 33). |

| 13 | Markus Vinzent (2015, p. 76) asked virtually the same question; “why should we trust Marcion’s view more than that of Tertullian?” Vinzent and Guthrie answered this rhetorical question in opposite ways (Vinzent favoring Marcion and Guthrie favoring Tertullian), reminding us of the ambiguity of open-ended rhetorical queries. Marcion and Tertullian may have read Paul’s rhetorical query (v.36) in very different ways. |

| 14 | See note 11 above. |

| 15 | Giles of Rome (1243-1316 CE) revised/recast “Junia” as “Junias” in medieval Latin, presuming male-exclusive apostolic authority. Only one ancient exegetist supported this, Epiphanius of Salamis (c. 315-403 CE)—who also asserted Priscilla was a man. Epiphanius is therefore an unreliable witness on apostles’ gender (Epp 2002). Epiphanius’ early Byzantine text-types were “marred by his paraphrases and extremely loose citations.” (Waltz 2013, p. 1338). Rare editions of Origen likewise masculinize Junia/Junias but these are exclusively medieval Latin editions (Epp 2002, p. 253). This has not discouraged complementarians from fallaciously asserting “Church Fathers were evenly divided” (Piper and Grudem 2021, p. 98). |

| 16 | |

| 17 | Abbott (2015, p. 57) states “‘Western Fathers’ denotes those from the Western Roman Empire who wrote primarily in Latin. … ‘Eastern Fathers’ refers to those from the Eastern Roman Empire who wrote mainly in Greek or Syriac.” |

| 18 | Origen’s use of this passage is found in his Fragmenta ex commentariis in epistulam i ad Corinthios 71.1-3 and 74.1-4 (Jenkins 1908). |

| 19 | James F. McGrath (2021, pp. 253–73) discusses the possibility that Paul’s female kinsfolk may have influenced his decision to join the Jesus movement. |

| 20 | Lane Fox’s (1986, p. 281) inferrence is derived from the greater than 5-to-1 ratio of women’s garments to men’s, recorded in the large seizure of church property at Cirta, Numidia (Constantine, Algeria) during the Diocletianic persecution in May of 303 CE as mentioned in “Trial before Zenophilus” [Gesta apud Zenophilum], 320 CE (Luijendijk 2008, p. 350). |

References

- Abbott, Philip J. 2015. Bringing Order to 1 Corinthians 14: 34–35. Master thesis, Pepperdine University, Malibu, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Aland, Kurt, Matthew Black, Carlo M. Martini, Bruce M. Metzger, and Allen Wikgren. 1975. Greek New Testament. London: United Bible Societies. [Google Scholar]

- BeDuhn, Jason D. 2013. The First New Testament: Marcion’s Scriptural Canon. Farmington: Polebridge. [Google Scholar]

- Berding, Kenneth. 1999. Polycarp of Smyrna’s view of the authorship of 1 and 2 Timothy. Vigiliae Christianae 53: 349–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooten, Bernadette H. 1982. Women Leaders in the Ancient Synagogue. Chico: Scholars Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bushnell, Katharine C. 1889. Keep silence. The Union Signal 15: 7. Available online: https://archive.org/details/mdu-043103/page/n558/mode/1up (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Carnelley, Elizabeth. 1989. Tertullian and feminism. Theology 92: 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, Donald A. 2021. Silent in the churches. In Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood: A Response to Evangelical Feminism, 3rd ed. Edited by John Piper and Wayne Grudem. Wheaton: Crossway, pp. 179–97. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Adam. 1836. The Holy Bible with a Commentary and Critical Notes: The New Testament, 2nd ed. London: Tegg & Son. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Raymond F. 2001. The origins of church law. The Jurist 61: 134–56. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Raymond F. 2002. 1 & 2 Timothy and Titus: A Commentary. Louisville: Westminster John Knox. [Google Scholar]

- A. Cleveland Coxe, trans. 1885, Fathers of the Second Century: Hemas, Tatian, Athanagorus, Theophilus, and Clement of Alexandria. Edinburgh: T&T Clark.

- Coyle, J. Kevin. 1983. The fathers on women and women’s ordination. In Women in Early Christianity. Edited by David M. Scholer. New York: Garland, pp. 117–67. [Google Scholar]

- David, Ariel. 2021. Byzantine basilica with graves of female ministers and baffling mass burials found in Israel. Haaretz. November 15. Available online: https://www.haaretz.com/archaeology/MAGAZINE-byzantine-basilica-with-female-ministers-and-baffling-burials-found-in-israel-1.10387014 (accessed on 6 March 2022).

- Delobel, Joël. 1994. Textual criticism and exegesis: Siamese twins? In New Testament Textual Criticism, Exegesis and Early Church History: A Discussion of Methods. Edited by Barbara Aland and Joël Delobel. Campen: Kok Pharos, pp. 98–117. [Google Scholar]

- Deming, Will. 2004. Paul on Marriage and Celibacy: The Hellenistic Background of 1 Corinthians 7. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- den Dulk, Matthijs. 2012. I permit no woman to teach except for Thecla. Novum Testamentum 54: 176–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dowd, Sharyn. 1992. Helen Barrett Montgomery’s ‘Centenary Translation’ of the New Testament: Characteristics and influence. Perspectives in Religious Studies 19: 133–50. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, Geoffrey. 2004. Tertullian. Routledge: London. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, Geoffrey. 2005. Rhetoric and Tertullian’s “De Virginibus Velandis”. Vigiliae Christianae 59: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, G. B. 1977. The Shorter Works of Guy B. Dunning. Huron: Dakota Bible College. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrman, Bart D. 1993. The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbaum, Pamela. 2009. Paul Was Not A Christian: The Original Message of a Misunderstood Apostle. New York: HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- Ekonomou, Andrew J. 2007. Byzantine Rome and the Greek Popes: Eastern Influences on Rome and the Papacy from Gregory the Great to Zacharias, A.D. 590–752. Lanham: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, Neil. 2006. Liberating Paul: The Justice of God and the Politics of the Apostle, 2nd ed. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elmer, Ian J. 2015. The Pauline letters as community documents. In Collecting Early Christian Letters from the Apostle Paul to Late Antiquity. Edited by B. Neil and P. Allen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Epp, Eldon Jay. 1966. The Theological Tendency of Codex Bezae Cantabrigiensis in Acts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Epp, Eldon Jay. 2002. Text-critical, exegetical, and sociocultural factors affecting the Junia/Junias variation in Rom 16.7. In New Testament Textual Criticism and Exegesis. Edited by A. Denaux. Leuven: Leuven University Press, pp. 227–92. [Google Scholar]

- Epp, Eldon Jay, and Gordon Fee. 1993. Studies in the Theory and Method of New Testament Textual Criticism. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, Louis H. 1992. Some observations on rabbinic reaction to Roman rule in third century Palestine. Hebrew Union College Annual 63: 39–81. [Google Scholar]

- Finlayson, Cynthia. 2013. New perspectives on the ritual and cultic importance of women at Palmyra and Dura Europos: Processions and temples. Studia Palmyreńskie 12: 61–85. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzer, Gottfried. 1963. Das Weib schweige in der Gemeinde: über den unpaulinischen Charakter der Mulier-Taceat-Verse in 1. Korinther 14. Munich: Christian Kaiser. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan, Neal M., and Edwina Hunter Snyder. 1981. Did Paul put down women in 1 Cor. 14:34–36? Biblical Theology Bulletin 11: 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, Donald. 1990. New Testament Introduction. Downers Grove: InterVarsity. [Google Scholar]

- Hagner, Donald Alfred. 1973. The Use of the Old and New Testaments in Clement of Rome. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Hahneman, Geoffrey Mark. 1992. The Muratorian Fragment and the Development of the Canon. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Herzer, Jens. 2019. Narration, genre, and pseudonymity: Reconsidering the individuality and the literary relationship of the Pastoral Epistles. Journal for the Study of Paul and His Letters 9: 30–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, Joel M. 2016. The Bible Doesn’t Say That: 40 Biblical Mistranslations, Misconceptions, and Other Misunderstandings. New York: St. Martin’s. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, R. Joseph. 1984. Marcion: On the Restitution of Christianity: An Essay on the Development of Radical Paulinist Theology in the Second Century. Chico: Scholars Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peter Holmes, trans. 1870, The Five Books of Quintus Sept. Flor. Tertullianus against Marcion. Edinburgh: T&T Clark.

- Horrell, David G., and Edward Adams. 2004. The scholarly quest for Paul’s church at Corinth: A critical survey. In Christianity in Corinth: The Quest for the Pauline Church. Edited by Edward Adams and David G. Horrell. Louisville: Westminster John Knox, pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ieraci, Laura. 2012. 2 Timothy: A Pauline text. KannenBright 2: 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Inglis, David. 2016. First Corinthians. Tricky NT Textual Issues. Available online: https://sites.google.com/site/inglisonmarcion/home/paul/marcions-apostolicon-the-pauline-epistles/first-corinthians (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Jenkins, Claude. 1908. Origen on 1 Corinthians. IV. Journal of Theological Studies 10: 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnson, Luke T. 1999. Oikonomia Theou: The theological voice of 1 Timothy from the perspective of Pauline authorship. Horizons in Biblical Theology 21: 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, William A. 2000. Toward a sociology of reading in classical antiquity. American Journal of Philology 121: 593–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kateusz, Ally. 2020. Women leaders at the table in early churches. Priscilla Papers 34: 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- LaFosse, Mona Joy. 2001. Situating 2 Timothy in Early Christian History. Master thesis, Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Lane Fox, Robin. 1986. Pagans and Christians. New York: Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Lavrinoviča, Aļesja. 2017. 1 Cor 14.34–5 without ‘in all the churches of the saints’: External evidence. New Testament Studies 63: 370–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, Amy-Jill. 2015. Short Stories by Jesus: The Enigmatic Parables of a Controversial Rabbi. New York: HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- Luijendijk, AnneMarie. 2008. Papyri from the great persecution: Roman and Christian perspectives. Journal of Early Christian Studies 16: 341–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, Margaret. 1999. Reading real women through undisputed letters of Paul. In Women and Christian Origins. Edited by Ross Sheppard Kraemer and Mary Rose D’Angelo. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 199–220. [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor, Kirk R. 2018. 1 Corinthians 14: 33b–38 as a Pauline quotation-refutation device. Priscilla Papers 32: 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Ralph P. 1984. The Spirit and the Congregation: Studies in 1 Corinthians 12-15. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, James F. 2021. What Jesus Learned from Women. Eugene: Cascade. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger, Bruce. 1987. The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance. Oxford: Clarendon. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger, Bruce. 1994. A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, 4th ed. London: United Bible Societies. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J. Edward. 2003. Some observations on the text-critical function of the umlauts in Vaticanus, with special attention to 1 Corinthians 14.34-35. Journal for the Study of the New Testament 26: 217–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, Matthew W. 2006. In the footsteps of Paul: Scriptural and apostolic authority in Ignatius of Antioch. Journal of Early Christian Studies 14: 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helen Barrett Montgomery, trans. 1924, Centenary Translation of the New Testament. Philadelphia: American Baptist Publication Society.

- Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome. 1979. 1 Corinthians. Wilmington: Michael Glazier. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome. 1986. Interpolations in 1 Corinthians. Catholic Biblical Quarterly 48: 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome. 1996. Paul: A Critical Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome. 1999. Daily Bible Commentary: 1 Corinthians. Peabody: Hendrickson. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy-O’Connor, Jerome. 2009. Keys to First Corinthians: Revisiting the Major Issues. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Neutel, Karin B. 2019. Women’s silence and Jewish influence: The problematic origins of the conjectural emendation on 1 Cor 14.33b–35. New Testament Studies 65: 477–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niccum, Curt. 1997. The voice of the manuscripts on the silence of women. New Testament Studies 43: 242–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odell-Scott, David W. 1983. Let the women speak in church: An egalitarian interpretation of 1 Cor. 14:33b–36. Biblical Theology Bulletin 13: 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Odell-Scott, David W. 1987. In defense of an egalitarian interpretation of 1 Cor 14: 34-36: A Reply to Murphy-O’Connor’s critique. Biblical Theology Bulletin 17: 100–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odell-Scott, David W. 2000. Editorial dilemma: The interpolation of 1 Cor 14: 34-35 in the Western manuscripts of D, G and 88. Biblical Theology Bulletin 30: 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odell-Scott, David W. 2018. The Sense of Quoting: A Semiotic Case Study of Biblical Quotations. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, Philip B. 1998. MS. 88 as evidence for a text without 1 Cor 14.34-5. New Testament Studies 44: 152–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, Philip B. 2009. Man and Woman, One in Christ: An Exegetical and Theological Study of Paul’s Letters. Grand Rapids: Zondervan. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, Philip B. 2019. Is 1 Corinthians 14: 34–35 a marginal comment or a quotation? A response to Kirk MacGregor. Priscilla Papers 33: 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Piovanelli, Pierluigi. 2018. What has pseudepigraphy to do with forgery? Reflections on the cases of the Acts of Paul, the Apocalypse of Paul, and the Zohar. In Fakes, Forgeries and Fictions: Writing Ancient and Modern Christian Apocrypha. Edited by Tony Burke. Eugene: Cascade, pp. 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Piper, John, and Wayne Grudem. 2021. An overview of central concerns. In Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood: A Response to Evangelical Feminism, 3rd ed. Edited by John Piper and Wayne Grudem. Wheaton: Crossway, pp. 73–115. [Google Scholar]

- Reichardt, Alexander. 1909. Der Codex Boernerianus. Der Briefe des Apostels Paulus. Leipzig: Verlag von Karl W. Hiersemann. [Google Scholar]

- Reydams-Schils, Gretchen. 2012. Clement of Alexandria on women and marriage in the light of the New Testament household codes. Novum Testamentum Supplements 143: 113–43. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, William. 2002. Difference and Distance in Post-Pauline Christianity. Bern: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander Roberts, and W. H. Rambaut, transs. 1868, The Writings of Irenaeus, 1st ed. Edinburgh: T&T Clark.

- Ropes, J. Hans. 1926. The Beginnings of Christianity. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, Ulrich. 1995. Marcion und sein Apostolos: Rekonstruktion und historische Einordnung der marcionitischen Paulusbriefausgabe. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer, Eduard. 1959. The service of worship: An exposition of I Corinthians 14. Interpretation 13: 400–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shack, Jennifer. 2014. A text without 1 Corinthians 14.34–35? Not according to the manuscript evidence. Journal of Greco-Roman Christianity and Judaism 10: 90–112. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, J. 2016. 1 Timothy 3:13–4:8. In The Oxyrhynchus Papyri LXXXI. Edited by J. H. Brusuelas and C. Meccariello. London: Egypt Exploration Society, pp. 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Sly, Dorothy I. 1987. The Perception of Women in the Writing of Philo of Alexandria. Ph.D. dissertation, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Talbert, Charles. 1987. Reading Corinthians: A Literary and Theological Commentary on 1 and 2 Corinthians. New York: Crossroad. [Google Scholar]

- Vinzent, Markus. 2015. Marcion’s gospel and the beginnings of Early Christianity. Annali di Storia dell’esegesi 32: 55–87. [Google Scholar]

- Waltz, Robert B. 2013. The Encyclopedia of New Testament Textual Criticism, last prelim. ed. St. Paul: Robert B. Waltz. [Google Scholar]

- Westfall, Cynthia Long. 2016. Paul and Gender: Reclaiming the Apostle’s Vision for Men and Women in Christ. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner-Hanks, Merry E., Patricia B. Ebrey, Roger B. Beck, Jerry Dávila, Clare H. Crowston, and John P. McKay. 2021. A History of World Societies, 12th ed. Boston: Bedford. [Google Scholar]

- William Wilson, trans. 1869, The Writings of Clement of Alexandria, 2nd ed. Edinburgh: T&T Clark.

- Wire, Antoinette C. 1990. The Corinthian Women Prophets: A Reconstruction Through Paul’s Rhetoric. Minneapolis: Fortress. [Google Scholar]

- Witherington, Ben. 1984. The anti-feminist tendencies of the “Western” text in Acts. Journal of Biblical Literature 103: 82–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamfir, Korinna, and Joseph Verheyden. 2008. Text-critical and intertextual remarks on 1 Tim 2:8-10. Novum Testamentum 50: 376–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuntz, Gunther. 1953. The Text of the Epistles: A Disquisition upon the Corpus Paulinum. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

| Translation Name | Date Published | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|

| King James Version | 1611 | KJV |

| American Standard Version Montgomery New Testament Confraternity Bible Revised Standard Version New American Standard Bible New American Bible New King James Version New Revised Standard Version | 1900 1924 1941 1946 1963 1970 1979 1989 | ASV MNT CB RSV NASB NAB NKJV NRSV |

| Edition | Text * | Date |

| KJV | What? Came the word of God out from you? Or came it unto you only? | 1611 |

| ASV | What? was it from you that the word of God went forth? or came it unto you alone? | 1900 |

| MNT | What, was it from you that the word of God went forth, or to you only did it come? | 1924 |

| CB | What, was it from you that the word of God went forth? Or was it unto you only that it reached? | 1941 |

| RSV | What! Did the word of God originate with you, or are you the only ones it has reached? | 1946 |

| New/Revised Edition | Text * | Date |

| NASB (Revised ASV) | Was it from you that the word of God first went forth? Or has it come to you only? | 1963 |

| NAB (Revised CB) | Did the word of God go forth from you? Or has it come to you alone? | 1970 |

| NKJV (Revised KJV) | Or did the word of God come originally from you? Or was it you only that it reached? | 1979 |

| NRSV (Revised RSV) | Or did the word of God originate with you? Or are you the only ones it has reached? | 1989 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wilson, J.A.P. Recasting Paul as a Chauvinist within the Western Text-Type Manuscript Tradition: Implications for the Authorship Debate on 1 Corinthians 14.34-35. Religions 2022, 13, 432. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13050432

Wilson JAP. Recasting Paul as a Chauvinist within the Western Text-Type Manuscript Tradition: Implications for the Authorship Debate on 1 Corinthians 14.34-35. Religions. 2022; 13(5):432. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13050432

Chicago/Turabian StyleWilson, Joseph A. P. 2022. "Recasting Paul as a Chauvinist within the Western Text-Type Manuscript Tradition: Implications for the Authorship Debate on 1 Corinthians 14.34-35" Religions 13, no. 5: 432. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13050432

APA StyleWilson, J. A. P. (2022). Recasting Paul as a Chauvinist within the Western Text-Type Manuscript Tradition: Implications for the Authorship Debate on 1 Corinthians 14.34-35. Religions, 13(5), 432. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13050432