1. Introduction

When we find ourselves in distress we seek healing, and that often takes place in the doctor’s office. People visit doctors for a variety of reasons, which often include psychosocial and spiritual concerns (

Gunn and Blount 2009;

Reiter et al. 2018). Primary care is often the first door people walk into for treatment and is often the only level of care that an individual will receive (

Blount and Bayona 1994). Patients are more likely to receive care from a primary care provider than a specialist, including a mental health provider (

Gunn and Blount 2009). Primary care, as a result, is an opportune context to integrate spiritual care across the continuum of prevention, early intervention, intervention, and crisis stabilization for a wide variety of health and mental health concerns. Despite this, there is limited understanding regarding the mechanisms of care to assess and address the spiritual determinants of health within primary care settings.

There are many complex interactions between our experiences, cognitions, emotional health, interpersonal functioning, and the development of illnesses (

Mate 2011). Psychoneuroimmunology has provided the research context for these complex interactions, identifying connections between stress, emotions, cognitions, and our immune responses (

Kiecolt-Glaser et al. 2002). In essence, there are frequently psychological and social determinants influencing symptoms such as insomnia, headaches, multiple sclerosis, and more (

Ader and Cohen 1993). A patient presenting physical symptoms to a doctor may have biological pathology, and there may be psychological factors that include emotional repression and existential distress influencing the presented pathology (

Kiecolt-Glaser et al. 2002).

This paper seeks to operationalize the theoretical mechanisms behind Christian mindfulness and integrated care (a team-based healthcare model which seeks to address psychosocial issues in primary care) to showcase a potential mechanism for performing spiritual intervention within primary care. Integrated care acknowledges individuals are more than the sum of their biological parts. Instead, the health of the individual is contextualized within his or her psychosocial contexts (

Blount and Bayona 1994;

Valentijn et al. 2013). Christian mindfulness is a unique type of intervention suitable for integrated care, as it emphasizes the attunement to one’s emotional state, our cognitive states, and our experience with the transcendent (

Trammel and Trent 2021). Consequently, Christian mindfulness exemplifies a mental status that promotes awareness to the ways our minds, bodies, and souls are interconnected and, therefore, provides empowerment for individuals to make changes in psychological, physical, and spiritual health.

1.1. Reviewing Spiritual Struggles and Strengths in Healthcare

Patients presenting in primary care are not merely seeking help for biological pathologies. In fact, 83 percent of individuals receiving primary care services present mental distress (Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2013), and each primary care visit has an average of five psychosocial problems (

Bikson et al. 2009). Patients do not always present emotional or spiritual distress, but spiritual factors are often operating underneath the surface. Research demonstrates the influence of psychospiritual factors for a range of health and mental health concerns, including chronic pain, insomnia, hypertension, anxiety, substance use, and more (

Koenig 2012). We will review both the mechanisms of spirituality associated with symptoms as well as with improvements in health and mental health. We will then connect how Christian mindfulness works to address and connect each of the determinants represented.

Spiritual struggles are associated with negative health and mental health outcomes and are categorized as (1) divine struggles (negative emotion toward God), (2) demonic struggles (concern that evil spirits are attacking an individual or causing negative events), (3) interpersonal struggles (concern about negative experiences with individuals or institutions), (4) moral struggles (worry or guilt about perceived offenses), (5) doubt (feeling troubled about doubts regarding faith), and (6) ultimate meaning (concern about not having meaning in one’s life) (

Exline 2013;

Exline et al. 2014).

There are myriad ways in which a spiritual struggle could present itself within a healthcare encounter. A clinically relevant spiritual struggle could include one who is diagnosed with cancer and has an automatic thought of “I must have done something wrong to deserve this. God must be punishing me.” This type of cognitive disposition may influence a depressive emotional response while simultaneously shaping one’s overall relation with the transcendent (

Koenig 2007). The individual may begin to experience anhedonia, fatigue, avolition, and a feeling that he or she deserves punishment. This emotional and spiritual state may increase risk for a range of healthcare concerns seen in primary care, including depression, insomnia, chronic pain, anxiety, and more (

Exline 2013;

Koenig 2007;

Koenig et al. 2015).

Conversely, there are spiritual states associated with positive health and mental health.

Koenig (

2014) identified some of the key mechanisms that overlap with positive health and mental health outcomes, including (1) forgiveness, (2) altruism, (3) gratefulness, (4) positive emotions, (5) well-being, (6) quality of life, (7) hope and optimism, (8) meaning and purpose, (9) self-esteem, and (10) personal control.

The same patient who presents a cancer diagnosis and has the automatic thought that “I must have done something to deserve this” may also have spiritual strengths that positively influence his or her health status. For example, the patient may have a theological belief that God draws near and walks with His people during times of suffering. A medical provider may elicit this theological belief, which may change the patient’s cognition to “God promises to be with me” and “He is a God who is well acquainted with suffering.” Therefore, “I can find strength and hope knowing He is with me.” This may then shift one’s psychological disposition, reducing stress, improving health, and facilitating ownership and adherence to the treatment plan.

Theoretical and research support for the integration of spirituality within healthcare settings has not produced any widespread uptake of spiritual integrative practices (

Best et al. 2015,

2016). There are a few whole person care models that emphasize the integration of spiritual assessment and intervention. For example, Koenig’s model utilizes nurses and care managers to perform spiritual assessments while incorporating spiritual care coordinators to link patients to chaplains (

Koenig 2014). Balboni incorporated a similar screening model but emphasized the role of the primary care team in caring for spiritual health needs (

Balboni et al. 2014). These models provide the foundation for the implementation of spirituality in traditional healthcare settings.

What is missing is a healthcare model that (1) creates a treatment team that is equipped to treat the whole person, (2) operationalizes workflows to perform interventions addressing the whole person, and (3) expounds on interventions that can be utilized to address the whole person. The utilization of Christian mindfulness within an integrated care context provides the foundation for the current gaps in the research.

1.2. Review of Integrated Care

Integrated care emerged in the 1970s and began to be researched in the 1990s (

Blount and Bayona 1994). Integrated care can be defined as a patient-centered approach which attempts to care for the psychosocial aspects of care within traditional medical settings (

Miller et al. 2017). Integrated care occurs on a continuum that begins with (1) care coordination, with separate mental and physical health systems that have close collaboration, (2) increases to co-located mental and physical health services, where there are shared workspaces but separate workflows, and ends with (3) fully integrated treatment with coordinated workflows and treatment plans (

Bikson et al. 2009). Integrated care is achieved through expanding traditional primary healthcare teams (medical provider, medical assistant, and nurse) to include a behavioral health provider (LCSW, psychologist, LMFT, etc.). The behavioral health provider works as an additional care team member who provides interventions to primary care patients.

Within this paper, we will focus on a fully integrated model of care called primary care behavioral health (PCBH). The PCBH model was intentionally structured to mimic the primary care workflow and therefore provide the best context for conceiving how to disseminate whole person care within primary care (

Reiter et al. 2018). PCBH also has a strong research base, is implemented broadly throughout the country, and is shown to be effective for addressing a wide range of health and mental health conditions (

Hunter et al. 2018).

1.3. Reviewing the Purpose of This Study

The purpose of this study is to build on the existing models that seek to integrate the psychosocial and spiritual determinants of health within primary care settings. We will review the current seminal works that review both the integrated and whole person care models while identifying innovations to expand these models. To accomplish this purpose, this study will (1) summarize the efforts to ingrate spirituality within primary care (whole person care), (2) summarize integrated care efforts to promote psychosocial integration, (3) identify Christian mindfulness as a potential intervention to address spirituality within integrated care models, and (4) operationalize the delivery of Christian mindfulness within a fully integrated care model. The conclusions from the conceptual review include both practice innovation for the assessment and intervention of spirituality in integrated care as well as a potential direction for future research to study Christian mindfulness within integrated care settings.

2. Spirituality in Primary Care

Addressing spirituality is important to patients. In fact, 69 percent of individuals identify as being very or moderately religious, and 83 percent indicated they would want their healthcare providers to ask about their spiritual beliefs (

McCord et al. 2004). Despite the patient’s desire to discuss spirituality, many healthcare settings do not discuss spirituality with patients (

Best et al. 2015,

2016). To better care for people, ways to more generally integrate spirituality within healthcare settings need to be considered.

2.1. Review of Whole Person Care Models

Whole person care models emphasize a provision of healthcare that addresses every aspect of the person (biological, psychological, sociological, and spiritual). The mechanisms associated with whole person care include a system that (1) treats patients as multidimensional persons, (2) schedules sessions with appropriate length, breadth, and depth of scope, (3) builds on the foundation of a doctor–patient relationship, and (4) involves team-based care (

Thomas et al. 2020). There are a few whole person care models that were either designed with primary care in mind or are comparable to ambulatory care settings. We will now review these models briefly. Later, we will explore integrated care models which discuss whole person care from a different angle. We will identify how both integrated and whole person care expand the determinants of health cared for within primary care while acknowledging their limitations. We will then identify how the integration of Christian mindfulness within PCBH may provide a model that truly address the whole person.

2.1.1. Koenig’s Model

Koenig conceptualized the functions of a treatment team that address the whole person as (1) identifying the spiritual needs of an illness (assessment), (2) addressing those spiritual needs (intervention), (3) creating an atmosphere where individuals feel comfortable with talking about their needs, (4) addressing the whole person needs of healthcare team members (training and staff support), and (5) providing whole person care to all patients (

Koenig 2014).

Koenig emphasized the need for care to be provided within a team-based context and defined the spiritual care team as consisting of a physician who performs spiritual assessment, a spiritual care coordinator (nurse or clinic manager) who reviews the assessments and identifies methods to connect the patient to resources, and a chaplain who addresses the spiritual needs of the patient. It is notable to mention that the chaplain is referenced as a resource outside of the clinic setting who is contacted by the spiritual care coordinator.

Koenig’s model provides helpful insights for conceptualizing whole person care teams for outpatient care settings. There are, on the other hand, some limitations to the model. For example, Koenig’s model retains the traditional care team within the walls of the clinic and seeks to intentionally utilize a chaplain for the means of coordinating care. This will meet the needs of some patients but not all of them. Patients often have challenges with completing referrals, and there is therefore a need to attempt to provide as much care for the patient as possible within the primary care context. In addition, this model seems to address the biological and spiritual determinants of care yet lacks team members to address the psychosocial factors.

PCBH includes psychological treatment for the patient’s emotions, cognitions, and behavioral needs. Christian mindfulness is an intervention that expands treatment by addressing the patient’s spiritual life while simultaneously prompting a connection between the individual’s physical and psychological life. Christian mindfulness within an integrated care context, as a result, provides a context for considering how to expand Koenig’s model to address the whole person.

2.1.2. Isaac et al.’s Model

Isaac et al. (

2016) developed a whole person model with an emphasis on integrating spirituality within primary care settings. Their work adds to the work of Koenig et al. by further elucidating ways that the integration of spirituality into primary care settings may support the primary care system in caring for patients to be seen as described below:

The integration of spirituality is influential in the patient’s perception of an illness: This can result in either positive or negative influences on health and mental health. For example, a patient may believe that their illness is related to a sin that has occurred within his or her life or family, leading to increased stress and poor health compliance. A patient could simultaneously relate to God as one who is with them during suffering and who provides for their needs. This spiritual posture may provide a sense of resilience, coping, and improved health (

Isaac et al. 2016).

The integration of spirituality aids in health promotion: Not only does spirituality impact the perception of illness but also the behaviors associated with health. Spirituality shapes one’s values, core ways of thinking, and as a result, how one behaves. The authors identify the importance of assessing and targeting spirituality for efforts of health promotion (

Isaac et al. 2016).

Spirituality and mechanisms of health behavior: The authors further depict the links between spirituality and health while identifying some of the challenges with assessing the mediating and moderating effects that spirituality has on health. Many of these are psychological in nature and include emotional and cognitive experiences. Our cognitive and emotional lives are where much spiritual content is processed, and they are therefore important to consider. An individual has experiences which prompt thoughts related to the transcendent. These experiences and thoughts are connected with deeper emotional content. Psychological and interpersonal determinants heavily overlap with spirituality and are not able to be adequately understood apart from understanding one’s inner life (

Isaac et al. 2016).

Isaac et al. (

2016) provided some context for the operationalization and implementation of the theoretical links they made between primary care practice and spirituality. Specifically, the authors outlined the following interventions to include (1) having spiritual conversations with patients regarding their health, (2) encouraging coping strategies that emphasize spiritual strengths, (3) taking spiritual histories with patients, and (4) referring to chaplains or spiritual directors as needed. The authors also referenced the importance of team-based collaboration for the integration of spirituality.

This model has some strengths, which include explanation of the spiritual dynamics that influence health. The authors identified practical ways in which one’s theological orientation may influence healthcare adherence and utilization. Similar to Koenig’s article, the authors did not, on the other hand, operationalize innovations to the treatment team that would alter treatment workflows. Christian mindfulness within PCBH expands the healthcare team, identifies workflows that are consistent with primary care, and provides concrete intervention to engage the whole person. We will now review one last model before reviewing the integrated care models.

2.1.3. Balboni’s Model

Balboni et al. (

2014) provided three well-defined structures for integrating spirituality within healthcare settings. These include (1) a generalist specialist model, (2) an existential functioning model, and (3) an open pluralism model. We will review each of these in some detail:

Generalist specialist model: The authors referenced the biopsychosocial-spiritual model of care and the importance of team-based care. The generalist specialist model assumes that every member of the care team shares responsibility for the provision of spiritual care. Simultaneously, the model identifies each team member as having varying expertise. Medical providers have unique expertise for addressing biological concerns, while clinical social workers have expertise in addressing psychosocial concerns. There is some discussion of workflow where the patient is (1) screened for spiritual needs, (2) seen by a social worker, nurse, or doctor who assesses their spiritual history, (3) receives further spiritual assessment and treatment from a chaplain, and then (4) engages in reassessment (

Balboni et al. 2014).

Existential functioning model: This model emphasizes what traditional healthcare providers can do to provide whole person care. The authors reviewed occasions where a clinician may have had more in-depth engagement with a patient, asking him or her about his or her spiritual life. There is acknowledgement that the clinicians may not have the same expertise as chaplains, but continued consultation and practice can increase the clinicians’ ability to engage in high-quality whole person care. The essence of this model is to equip clinicians to better address the spiritual aspects of the patient (

Balboni et al. 2014).

An open pluralism view: Within this view, there is a broader conceptualization of how to view spirituality. This model provides potential for increased inclusivity for both the providers who are performing interventions as well as the individuals who are receiving care (

Balboni et al. 2014).

There have been myriad theoretical links found within the models reviewed that provide support for the integration of spirituality within healthcare generally and within primary care more specifically. Further, there is some degree of structure regarding how to construct care teams within primary care to provide spiritually integrated care for patients. Simultaneously, the models lacked some specificity regarding how to assess and address spirituality in primary care, and none of them operationalized the roles and workflows for a behavioral health professional seeking to integrate spirituality in a primary care team. Furthermore, there are references to a few different interventions and treatment models, but there is not much information about the utilization of these within the whole person care model.

The current paper will seek to outline the specificity found within integrated care models while operationalizing the provision of Christian mindfulness intervention within a fully integrated care model. This may provide a step forward in the research regarding spiritual integration within primary care settings.

3. Review of Integrated Care Models

The majority of individuals with behavioral health needs do not receive treatment, and those that do most frequently receive treatment within primary care settings (

Hunter et al. 2018). There have been a handful of integrated care models that have strong research support, which we will review below.

3.1. Primary Care Behavioral Health (PCBH)

The PCBH model is a population-based model that aims to increase the primary care system’s ability to provide behavioral healthcare. The behavioral health provider functions as a generalist who is accessible to healthcare staff, engages in team-based care, works to educate the healthcare system on whole person care, and provides care as a routine facet of treatment (

Reiter et al. 2018). Within the PCBH model, there is an emphasis on the behavioral health provider adapting their practice style to match primary care. Consequently, the behavioral health provider performs assessments and interventions like a primary care provider would and not like a specialty mental health provider, increasing accessibility.

A strength of the PCBH model is that it expands the healthcare team to address the psychosocial determinants of health and provides a well-defined workflow for the behavioral health provider. A limitation is that it does not provide a specific context for spiritual integration.

3.2. Other Integrated Models

The collaborative care model (CCM) utilizes care managers and registry systems to link patients with psychiatric care to provide high quality and efficient medication management (

Goodrich et al. 2013). The care manager would perform assessments, psychosocial intervention, and share the assessment results with a psychiatrist. The psychiatrist would make medication recommendations and conduct training for primary care providers to support them with managing illnesses.

Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) addresses substance use disorders within non-substance use disorder settings (emergency room, medical settings, etc.). SBIRT provides a system of care which implements universal screenings, brief interventions, brief treatment, and when needed, referral for those who experience substance misuse (

Agerwala and McCance-Katz 2012). SBIRT has gained wide popularity due to the efficacy in addressing substance use disorders across the continuum of prevention, early intervention, and beyond.

Though the integrated models have expanded the number of determinants addressed in primary care, integrated models of care are not set up to adequately address the spiritual determinants of care. In fact, there were no articles identified that explicitly conceptualized the provision of spiritual care within an integrated care model.

PCBH integrates a behavioral health provider as a team member who has expertise in the psychosocial determinants of health, which heavily overlap with the interventions often utilized to assess and address spirituality Behavioral health providers are well trained in the provision of mindfulness interventions and can easily be trained to perform Christian mindfulness interventions. We will now review the theoretical foundations for Christian mindfulness. We will then operationalize the utilization of Christian mindfulness within a fully integrated care model.

4. Mindfulness and the Interconnection of One’s Mind, Body, and Soul

Mindfulness is a spiritual and psychological practice that has been the subject of myriad research initiatives. Mindfulness is “the awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment by moment” (

Kabat-Zinn 2003, p. 145). Paying attention to one’s thoughts and attitudes increases one’s awareness of what they are thinking, their affective states, what they are feeling in their body, and the connection between the cognitive, emotional, and physical (

Shapiro et al. 2006). In addition, mindfulness is associated with increasing the connection to the transcendent (

Carmody et al. 2008). The spiritual benefit is experienced by those from various faith traditions, as well as those who do not claim a faith tradition. Mindfulness practice is associated with spiritual and psychological health (

Carmody et al. 2008;

Lazaridou and Pentaris 2016;

Ludwig and Kabat-Zinn 2008).

The origins of mindfulness are associated with Christian and Buddhist philosophy and therefore have spiritual roots (

Kabat-Zinn 2003;

Trammel 2017). Mindfulness practice positively correlates with spirituality, which showcases the overlap between the two constructs (

Carmody et al. 2008). Contemplative Christians and Buddhists alike identify mechanisms such as cognitions, emotions, and physiological experiences as the vehicles through which spirituality occurs. This is not radically different from the faith traditions that are influenced by the Hebrew Bible, as the words for soul translate as neck, breath, stomach, heart, flesh, and bowels. These Hebrew translations demonstrate the ways one’s spiritual life is animated through his or her cognitive, affective, and physiological experiences (

Cooper 2000). The mind, body, and soul are connected and are constantly influencing one another.

The roots of mindfulness utilize the philosophies of Buddha (

Kabat-Zinn 2003). In addition, Christians have historically utilized contemplative practices which emphasize mindfulness interventions and concepts (

Trammel 2017). In both cases, mindfulness philosophy adapts teachings that the spiritual life is one that is embodied and not merely transcendental. The soul is not merely a facet of ourselves that is decontextualized from our thoughts, feelings, and bodies. Instead, the soul animates itself through our thoughts, physical experiences, and emotions. Mindfulness, as a result, has both cognitive and physiological implications in both what one pays attention to and the types of benefits received from the practice (

Lazaridou and Pentaris 2016).

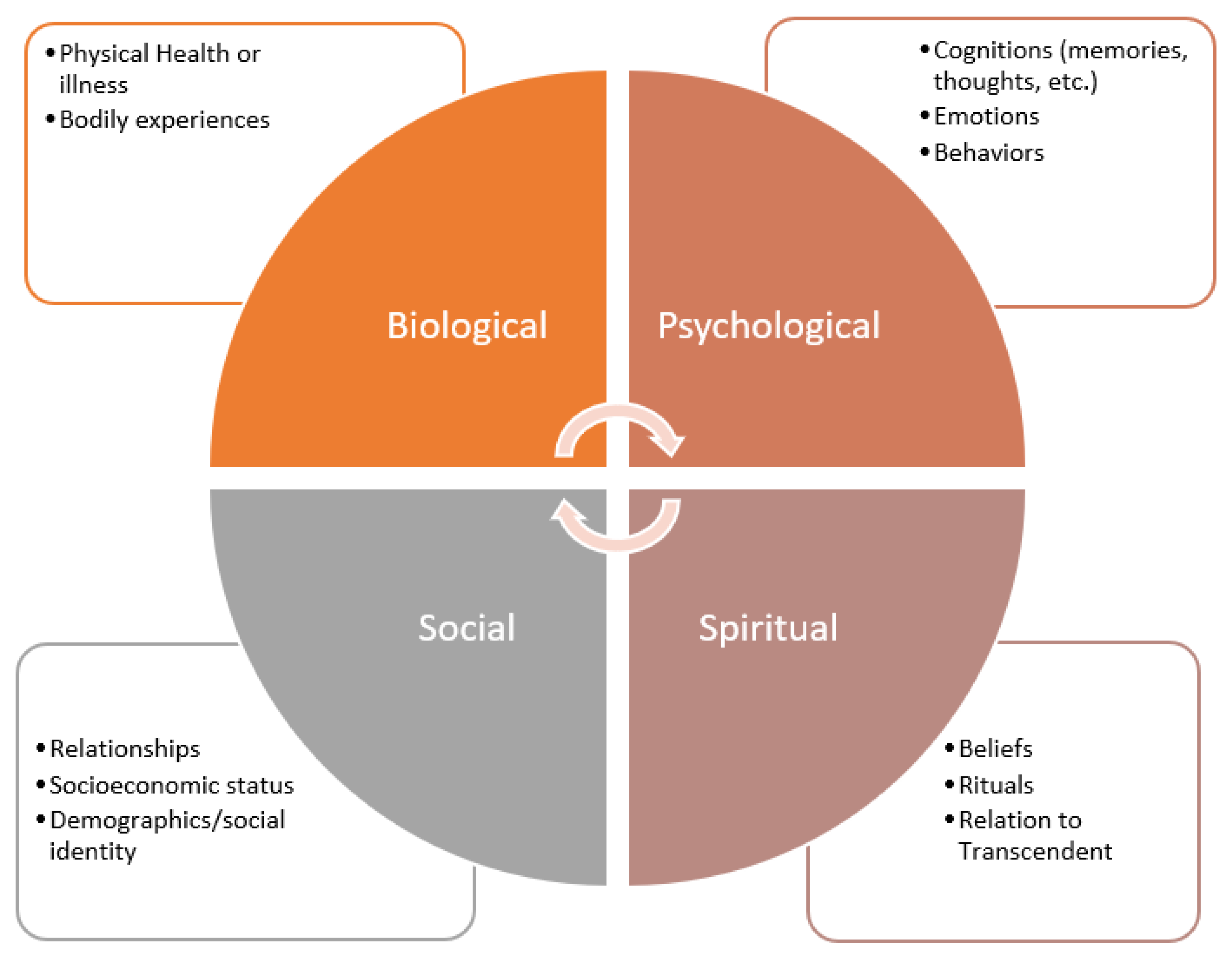

Understanding these overlapping qualities provides context for why psychologists, clinical social workers, and medical providers have both responsibility and expertise that can be utilized to address spirituality (see

Figure 1). Spirituality is not merely about knowing the right theological facts; it is about understanding how the experiences of a person’s thoughts, emotions, and body have intersected with parts of one’s story and have come to shape his or her relationship to the transcendent (

Anandarajah and Hight 2001). As a result, clinical social workers who have expertise in engaging the psychological and sociological implications of a person have a part to play in spiritual care. Likewise, a doctor who has expertise in the biological determinants of health has skills that can be utilized to support a patient’s spiritual health. One’s spirituality is embodied, and it is contextualized. This does not mean that chaplains do not have expertise that is unique; it just means that the integration of spirituality is nuanced.

Though mindfulness has spiritual roots, researchers and clinicians have sought to despiritualize mindfulness for wider research and clinical application (

Ludwig and Kabat-Zinn 2008). Kabatt-Zinn and others have secularized mindfulness to be used as a clinical tool rather than a spiritual practice (

Kabat-Zinn 2003;

Ludwig and Kabat-Zinn 2008;

Trammel 2017). This secularization has emphasized psychological concepts such as affect and cognition to support the application of mindfulness in more secular settings. This secularization mixed with the utility of mindfulness intervention has led to many theoretical practices such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, and Dialectical Behavioral Therapy adopting mindfulness. We will now review research regarding the ways mindfulness has been utilized within healthcare settings as a means of promoting health and mental health.

Mindfulness and Healthcare

Kabatt-Zinn’s research in mindfulness for reducing stress has prompted the utilization of mindfulness within healthcare settings. Mindfulness is efficacious in addressing a range of medical concerns to include depression, inflammation, drug and alcohol use, and more (

Crenswell and Lindsay 2014). Equipping the healthcare system to utilize mindfulness to address stress and other healthcare concerns within primary care and other healthcare settings provides a unique strategy for providing mindfulness interventions for individuals who may not receive services within mental health settings. Addressing these issues in healthcare settings also provides an opportunity for prevention and early intervention to help people become well and stay well (

Irving et al. 2009).

5. Christian Mindfulness in Primary Care

Mindfulness is a treatment approach which facilitates awareness of the affective, cognitive, and physiological states (

Crenswell and Lindsay 2014;

Ludwig and Kabat-Zinn 2008). Further, mindfulness prompts the individual to not only become aware of each of these concepts individually but the way in which these constructs interact. For example, a mindfulness participant may notice thoughts related to work duties occupying his or her awareness. This person may also recognize that when these thoughts emerge, there is a tightness felt within the chest and a churning within the gut of the participant. These experiences may be associated with an affective state of anxiety. Developing awareness of these states provides participants with insight into how their experiences are connected with cognitions, affective states, and physiological experiences. Recognizing these interactions also provides multiple sources where an intervention can occur.

Christian mindfulness incorporates many of the same processes as mindfulness in general but explicitly facilitates an attunement to God’s work within the person.

Trammel and Trent (

2021) defined the primary purpose of Christian mindfulness as being “about making time to turn our whole attention to God so that we can hear and abide in his voice above the chatter and stress of our lives (17).” The goal of Christian mindfulness is not detachment but rather an attaching to the presence of God the Father, Son, and Spirit. Developing further awareness regarding one’s affective, cognitive, and physiological status allows a person to better understand God’s involvement in his or her life.

This is confirmed within the Hebrew Bible, as Hebrew words for soul include nephesh (neck, stomach, or throat), ruach (breath or spirit), qureh (inner parts or bowels), and leb (heart). The theme of the interconnectedness of humans is carried forward within the New Testament Bible, as soul is translated as psyche (breath of life), soma (body), and kardia (the heart) (

Cooper 2000). These terms demonstrate that the soul is not a metaphysical structure that cannot be named or touched but rather an embodied entity that emerges from complex interactions between people’s bodies (to include the brain), minds (to include cognitions and affective states), and physical selves. The healthcare implications for whole person care that derive from these spiritual insights cannot be understated. As a result of the connections between each determinant of health, we will utilize Christian mindfulness as a mechanism of intervention to explore.

There is a realization that Christianity is only one religion and that individuals that do not share the Christian faith would not be appropriate for using Christian mindfulness intervention. Many individuals who integrate spirituality into healthcare identify the need to do this explicitly (

Johnson 2007). We, as a result, recognize that there are other specific mechanisms to engage individuals of Jewish, Hindu, Muslim, and a myriad of other faith traditions. The focus on Christian faith is not to elevate one faith over another but rather to provide an example of a mechanism for explicitly engaging in an individual’s faith tradition.

Many patients have a desire to have their spiritual lives assessed and addressed in the mental health setting (

Oxhandler et al. 2018). In addition, there is an association between the utilization of spirituality and positive health outcomes (

Koenig 2012). Christian mindfulness is a promising form of intervention that can be utilized in integrated care models that seek to provide interventions that address spirituality in an efficient manner. There is now a resource for behavioral health providers which provides the theoretical foundation and practice tools as a means of equipping behavioral health providers to engage in Christian mindfulness with patients (

Trammel and Trent 2021). We will briefly review the unique context endemic to primary care settings while identifying why Christian mindfulness provides a promising intervention for integrated care settings.

5.1. Understanding the Primary Care Workflow

Primary care and family medicine utilize workflows that allow medical providers to see a high volume of patients (

Valentijn et al. 2013). As a result, the primary care system utilizes a population health framework that shapes the workflow of primary care. One of the core concepts that differs from specialty mental health settings is that primary care and family medicine providers often see 30 or more patients daily (

Dobson et al. 2011). In comparison, a traditional therapist may see an average of 5–6 patients daily. Mental health professionals functioning in primary care settings must therefore adopt a population health mindset, seeing a higher volume of patients within these settings (

Reiter et al. 2018). Consequently, behavioral health providers within primary care must utilize interventions that fit within the primary care setting. Below are some of the reasons why Christian mindfulness is an ideal type of intervention to utilize within integrated care settings.

5.2. Christian Mindfulness Can Be Efficiently Utilized in Clinics

Christian mindfulness interventions can be performed in as little as 5 min and therefore provide an efficient method for addressing spirituality within primary care settings. Behavioral health providers can quickly assess a patient’s presenting symptoms, whether the patient wants to incorporate spirituality into his or her care, and whether Christian mindfulness could be beneficial to the patient. The provider can then facilitate a Christian mindfulness intervention followed by a debriefing of what the patient noticed during the experience. The provider can then engage with a plan of how to utilize the interventions within the patient’s daily life. This kind of assessment and intervention process fits with the typical 20-min interventions performed within integrated care settings.

5.3. Patients Can Utilize Modules Outside of a Clinic

Primary care relies on patients engaging in behavior changes outside of clinic sessions. There are guided Christian mindfulness meditation resources that can be utilized outside of clinics so that patients gain the skills to eventually guide themselves through Christian mindfulness practices (

Trammel 2018). Similar to the homework provided within CBT, behavioral health providers can guide patients through Christian mindfulness practices, provide them with resources to utilize outside of the clinic, and then create a treatment plan for the patient. Behavioral health providers can coach the patient through methods of utilizing the intervention while paying attention to his or her cognitive and emotional states while engaged in the intervention.

5.4. Christian Mindfulness Addresses the Whole Person

As mentioned above, Christian mindfulness is a type of intervention that addresses the mind, body, and soul. Furthermore, Christian mindfulness prompts the participant to identify how these structures are connected (

Trammel and Trent 2021;

Trammel 2017). This has significant implications for a patient of faith who presents with a healthcare concern. For example, a patient may be having fears about a loved one who has been diagnosed with a newfound illness. The individual may have unrealized cognitions, such as fear that the disease may progress and lead to the death of said loved one. This may generate existential concerns about the eternal status of their loved one. This spiritual anxiety perpetuates stress that is embodied and manifests as tension headaches (

Exline 2013;

Mate 2011). The patient presents a chief complaint of continued headaches and has exacerbating factors of stress, anxiety, and spiritual questions operating underneath the surface.

A primary care clinic which is equipped with a structure to disseminate Christian mindfulness would have the competence to support the patient with making these connections (

Balboni et al. 2014;

Isaac et al. 2016). A patient who experiences an intervention of Christian mindfulness would likely be able to identify the connections between his or her experiences and the psychological, spiritual, and physical health consequences (

Trammel and Trent 2021). The patient would also be provided with resources to include Christian mindfulness to manage these healthcare concerns that contextualize the symptom presentation through a whole person care model. Ultimately, the patient would identify that he or she is able to shift the focus from the distressing thought to God. Experiencing the presence of God may provide the individual with a sense of peace and safety, having an impact on his or her emotional and physical selves.

6. Operationalizing Christian Mindfulness within the PCBH Workflow

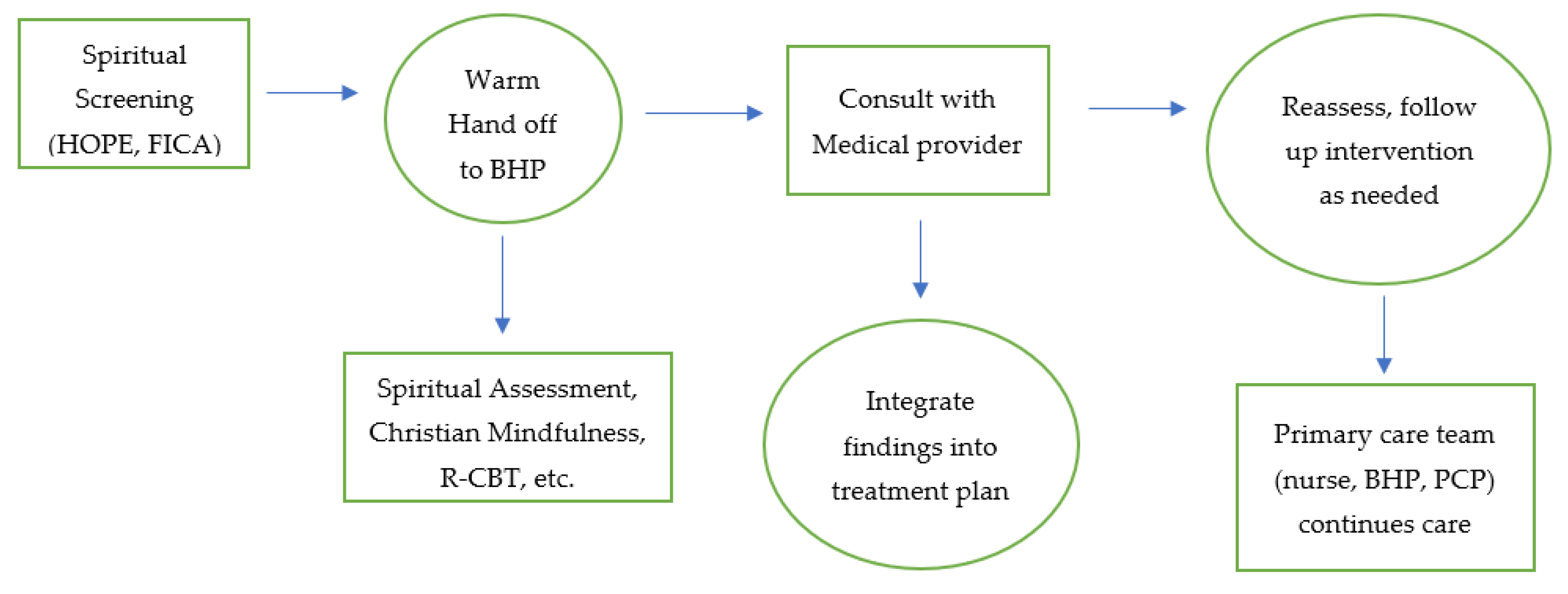

We will now operationalize the use of Christian mindfulness within a PCBH model (see

Figure 2). The PCBH model could be utilized to enhance the primary care team’s ability to provide care for the whole person, and PCBH could be expanded by integrating facets from whole person care models. PCBH includes screening tools to identify psychosocial complaints to include anxiety, depression, substance use, adverse childhood experiences, experiences with trauma, and more. A PCBH model that explicitly integrates spirituality could utilize spiritual screening tools to include the HOPE and FICA (

Borneman et al. 2010;

Anandarajah and Hight 2001). These screening tools would either be provided by a medical assistant or nurse as a part of the initial intake or in the waiting room while the patient fills out forms. Patients who are identified as having health distress and who are interested in including spirituality within their care would be flagged as a potential patient to consult with a behavioral health provider via a warm handoff. We will identify the process and content of warm handoffs below.

Central to the functioning of PCBH is the utilization of warm handoffs (

Reiter et al. 2018). Warm handoffs occur when a behavioral health provider provides a visit with a patient within the context of a visit with a medical provider. Warm handoffs can occur before or after the primary care provider sees the patient. Warm handoffs may be initiated by a nurse, medical assistant, primary care provider, front office staff, lab staff, or others. The behavioral health provider is then prompted to see the patient. The behavioral health provider will engage in the assessment and intervention while contextualizing important life factors to include spirituality within the visit. Warm handoff visits are typically 20–30 min long and prioritize the provision of care in a manner that is convenient for the patient (same-day visits that are a part of the primary care visit).

Patients sometimes will follow up with the behavioral health provider for episodes of care. An episode of care would occur when a patient has a particular issue he or she wants to work with the behavioral health provider on outside of their routine medical visits (sleep, stress management, depression, anxiety, grief, etc.) The behavioral health provider may meet with the patient for a series of several visits until adequate progress is made. Within follow-up care, a patient may receive a brief trial of CBT, narrative-focused therapy, Christian mindfulness, or other treatments.

Behavioral health providers function as generalists, addressing the issues of stress, sleep, anxiety, hypertension, grief, and so on. Since the PCBH model emphasizes high productivity and providing care across the continuum for a range of healthcare needs, it also provides the opportunity to utilize Christian mindfulness for large populations and for a variety of healthcare challenges. Providing this in primary care provides a care context designed to ensure accessibility to Christian mindfulness interventions.

Christian Mindfulness within PCBH

A behavioral health provider could provide a Christian mindfulness intervention during a warm handoff. A patient may come in to see a primary care provider for hypertension. Though the presented concern is his or her blood pressure, the patient scores positive on a screening for anxiety, identifies as Christian via the HOPE screening tool, and indicates that the patient’s faith is important to his or her life (

Anandarajah and Hight 2001). The behavioral health provider is able to see the patient while the primary care provider is finishing with another patient. The behavioral health provider identifies the challenges the patient has had with controlling worry, with increased stress and challenges with boundaries, and with the experience of anxiety that presented through physiological signs such as racing heart and sweaty palms. The patient, upon completing a body scan, identifies a tightness in the chest, a heaviness on his or her shoulders, and distracting thoughts about not doing enough. When explored further, the patient identifies challenges with worries that he or she will lose his or her salvation. The patient is able to explore his or her theological beliefs about assurance of salvation and are able to utilize Christian mindfulness interventions to become more in tune with the Spirit’s presence within his or her life. The patient utilizes centering prayer techniques to allow Gospel truths to work their way into his or her mind, body, and soul and experience not only psychological and spiritual benefits but improvements in his or her blood pressure readings (

Timbers and Hollenberger 2022).

This is one of thousands of potential examples of the ways in which Christian mindfulness can be utilized within a fully integrated care context. This has the potential to truly change thousands of people’s lives. Stigma, challenges with time, financial concerns, and more prevent individuals from receiving help from specialized mental health providers. In addition, there is a growing number of individuals who feel uncertain about seeking care from spiritual leaders. Providing Christian mindfulness within integrated care could greatly expand the amount of people receiving whole person treatment.

7. Future Research

There are myriad studies that review the connection between spirituality and health. In addition, there are several studies that draw attention to the overlap of our mental health and spiritual interventions. There is, on the other hand, a limited amount of studies and knowledge regarding how to disseminate spiritual interventions within primary care. Christian mindfulness is a promising form of spiritual intervention for supporting people of faith and, as stated above, fits with the utilization of primary care services. The following studies will provide further understanding regarding the potential utilization of Christian mindfulness, along with its potential efficacy.

7.1. Utilization of Christian Mindfulness

In order to assess the efficacy of an intervention, we have to first identify interventions to support the implementation of the intervention. There is a need to construct studies that would assess behavioral health providers’ willingness and ability to implement Christian mindfulness within PCBH settings. The study could also identify any barriers within the clinic systems for performing Christian mindfulness. Furthermore, it would be worth exploring the primary care providers’ (PCPs’) perception of spiritual integration and whether the PCPs’ perceptions influence the utilization of behavioral health to perform this service. Last, there is a need to assess the patient’s perception of the usefulness of the intervention. This is perhaps one of the most important areas of study. If patients identify that they both desire and benefit from the intervention, then there is a compelling case that systems need to adjust to ensure they are structured to provide this for patients.

7.2. Efficacy of Intervention

After understanding the mechanisms that increase the uptake of Christian mindfulness within PCBH settings, there is a need to understand the efficacy of the interventions for various health and mental health conditions. As stated above, there are multiple conditions in which behavioral health providers can utilize Christian mindfulness. In addition, behavioral health providers can utilize Christian mindfulness across the treatment continuum to include prevention, early intervention, or treatment. Assessing the efficacy of Christian mindfulness interventions for these various conditions such as depression, anxiety, grief reactions, adjustment disorders, hypertension, and so on would be helpful in understanding the nuances in how Christian mindfulness works and what it is effective for treating them.

Furthermore, there could be benefits to assessing the difference in efficacy for individuals who identify as Christians receiving Christian mindfulness interventions versus mindfulness interventions as usual. There has been one previous study which was performed within a Christian college (

Trammel 2018). Performing a similar study within an integrated context could build on the current understanding of the efficacy of Christian mindfulness for a different population and through a different mechanism. Performing a randomized control trial that assesses these differences may provide some of the specific mechanisms of action associated with the benefits of integrating spirituality into healthcare.

7.3. Expansion of Skillsets

Core to the implementation of integrated care are the ways that whole person care provided through integrated care teams enhance the skillsets of team members. Primary care providers who work with behavioral health providers will likely get better at managing psychosocial concerns. Conversely, behavioral health providers working with primary care providers will develop enhanced understanding regarding the ways biology and psychology are interconnected. As behavioral health providers integrate spiritual assessment and Christian mindfulness, the whole care team may grow in their ability to provide spiritual care to patients. Like

Balboni et al. (

2014) depicted in the generalist specialist model, each of these team members are generalists as they relate to the provision of spiritual care, but they have the potential to expand their skills in performing spiritual care. Researching the core skills associated with spiritual care along with their improvement as these are engaged would be a contribution to the literature.

7.4. Chaplains as Consultants

As referenced by

Balboni et al. (

2014), chaplains are experts for the provision of spiritual care. Integrated care utilizes behavioral health providers as consultants to primary care providers and also includes psychiatry providers as consultants. There are currently no identified models which integrate chaplains in a consulting role. Since behavioral health providers have many of the core skills to engage patients psychologically, consulting with a chaplain may provide additional benefits, with behavioral health providers seeking to enhance their ability to provide spiritual care. Further conceptualizing and researching such a model would be beneficial. In addition, identifying the ways this improves healthcare outcomes and the skillsets of clinicians would be of interest.

8. Conclusions

Primary care is a population-based model of healthcare designed to address a wide range of healthcare concerns. Spirituality is often influential in the presentation of symptoms and is simultaneously a powerful intervention tool that is essential for the provision of high-quality healthcare. Though spirituality is integral to healthcare, it has seldomly made its way within the walls of health centers.

Christian mindfulness is a type of intervention that promotes awareness of the whole person. Furthermore, Christian mindfulness facilitates the realization that our minds, bodies, and souls are connected and influence one another. Consequently, individuals are able to increase their understandings of how their physical symptoms are connected to their emotional, spiritual, and interpersonal health as they engage in Christian mindfulness practices. There is also an increased ability to become more intentional in how to focus and shift one’s attention after becoming more familiar with Christian mindfulness practices.

People are able to experience an increased sense of peace when shifting their awareness to God and meditating on the core truths found within the Bible. This increased sense of peace has a significant influence on one’s mental and physical health and is therefore incredibly relevant to one’s healthcare. Many individuals acknowledge a need to have every aspect of their health addressed, and there are myriad health conditions that are influenced by emotional states, spirituality, and interpersonal functioning. Christian mindfulness provides practitioners with a powerful tool to support the care of patients.

The majority of healthcare concerns that patients present could benefit from Christian mindfulness. As mentioned above, there is an average of five psychosocial needs included within each primary care visit. We see that our health is interconnected and that our social, psychological, and spiritual determinants influence our physical health. Consequently, the provision of Christian mindfulness helps address these concerns.

I have experienced anecdotal evidence of Christian mindfulness being effective within the clinic where I see patients. Each time I perform a Christian mindfulness intervention, the patients indicate that they experience (1) increased awareness regarding their physiological experiences, (2) increased awareness regarding their affective states, (3) a feeling of peace and relaxation, (4) the experience of a connection with God, (5) a connection between the emotional, physical, and spiritual constructs, and (6) an ability to shift one’s awareness, influencing the emotional, physical, and spiritual states. These impacts have supported treatment for a range of healthcare issues that include hypertension, depression, diabetes, anxiety, chronic pain, insomnia, headaches, and more.

There is a need to understand how to perform empirical studies that provide context to the benefits of Christian mindfulness. Increasing this understanding has the potential to transform the healthcare system to reflect a biopsychosocial-spiritual model of treatment. The consequence of this would likely be patients who experience improved outcomes and satisfaction.