Indonesian Islamic Students’ Fear of Demographic Changes: The Nexus of Arabic Education, Religiosity, and Political Preferences

Abstract

:1. Introduction

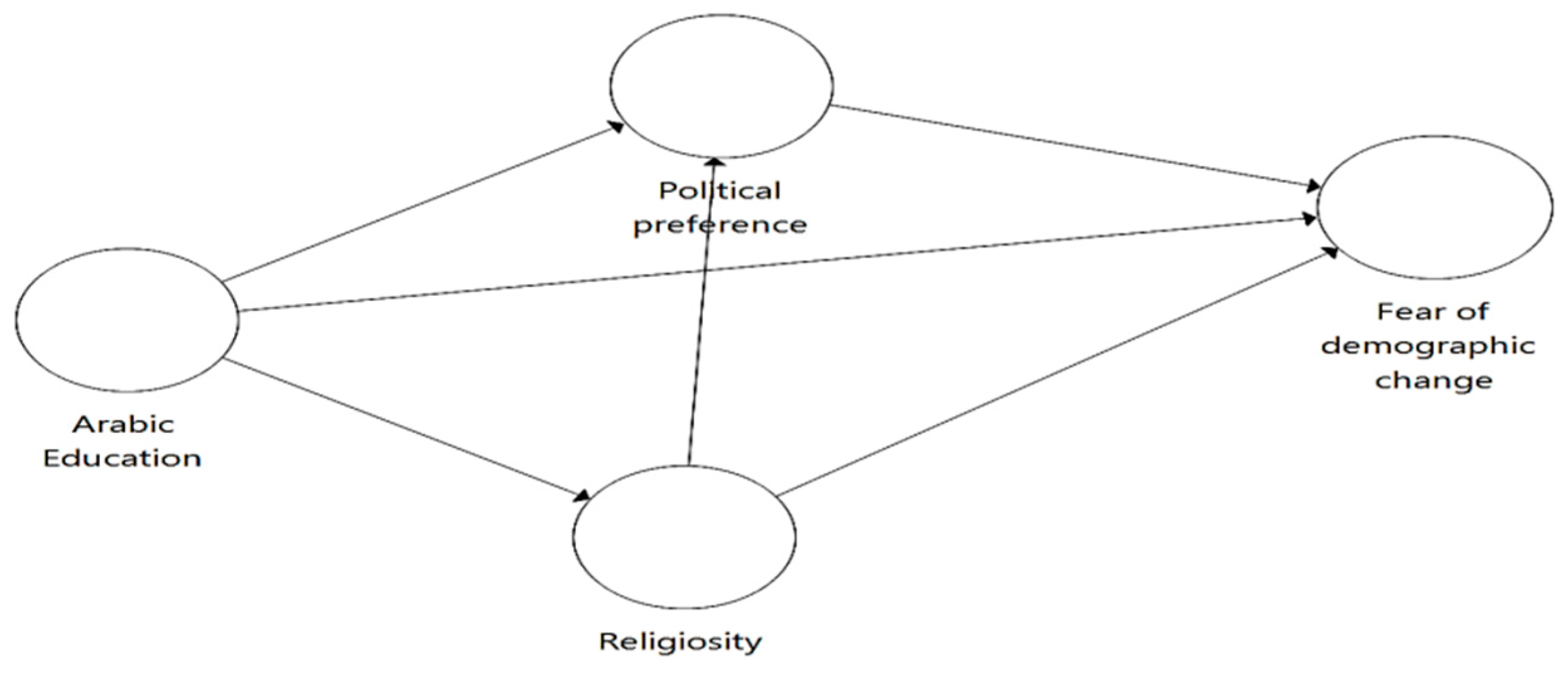

Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Sample

2.3. Measures

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Items | Statements | Source |

| Arabi2 | I can read basic Arabic | |

| Arabi3 | I learned basic Arabic | Self-designed |

| Arabi5 | I learned basic Arabic from my childhood | |

| FearDem1 | I am a proud native of my region | |

| FearDem2 | I am concerned if newcomers taking advantage of my region | Self-designed |

| FearDem3 | The native and indigenous people must most benefit from the economy | |

| PolP1 | I support a congressman advocating early sex education | (Haidt and Graham 2007) |

| PolP2 | I support the future president with a strong position against radicalism | |

| PolP3 | the government must support the LGBT rights | |

| Religio1 | My religion has clear directions toward permissible consumption | (Dali et al. 2019) |

| Religio2 | I cannot obtain something unpermissible | |

| Religio4 | My life strictly follows Islamic teaching | |

| Religio5 | I maintain my time to pray and contemplate my life | |

| Religio6 | I firmly believe Islamic teaching as the afterlife live-saver |

References

- Alfa, Muhammed Salisu, Hanafi Dollah, and Nurazzelena Abdullah. 2015. Analysis of the Impact of Arabic-Malay Bilingual Dictionaries in Malaysia. UMRAN—International Journal of Islamic and Civilizational Studies 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwi, Zulfahmi, Rika Dwi Ayu Parmitasari, and Alim Syariati. 2021. An Assessment on Islamic Banking Ethics through Some Salient Points in the Prophetic Tradition. Heliyon 7: e07103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Wreikat, Asma, Pauline Rafferty, and Allen Foster. 2015. Cross-Language Information Seeking Behaviour English vs Arabic. Library Review 64: 446–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amodio, David M., and Mina Cikara. 2021. The Social Neuroscience of Prejudice. Annual Review of Psychology 72: 439–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ananta, Aris. 2020. Gagasan Konseptual Prospek Mega-Demografi Menuju Indonesia Emas 2045 (the Outlook of Mega-Demography Toward Indonesian Golden Era 2045). Jurnal Kependudukan Indonesia 15: 119–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwari, Moh. Kanif. 2012. Pandangan Adonis terhadap Puisi dan Modernitas. Adabiyyāt: Jurnal Bahasa Dan Sastra 11: 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbruster, Heidi, and Souhila Belabbas. 2021. Between Loss and Salvage: Kabyles and Syrian Christians Negotiate Heritage, Linguistic Authenticity and Identity in Europe. Languages 6: 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyad, Essam. 2022. Re-Evaluating Early Memorization of the Qurʾān in Medieval Muslim Cultures. Religions 13: 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassarri, Delia, and Amir Goldberg. 2014. Neither Ideologues nor Agnostics: Alternative Voters’ Belief System in an Age of Partisan Politics. American Journal of Sociology 120: 45–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barabadi, Elyas, Mohsen Rahmani Tabar, and James R. Booth. 2021. The Relation of Language Context and Religiosity to Trilemma Judgments. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 52: 583–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmihoub, Kamal. 2018. Language Attitudes in Algeria. Language Problems and Language Planning 42: 144–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benstead, Lindsay J., and Megan Reif. 2013. Polarization or Pluralism? Language, Identity, and Attitudes toward American Culture among Algeria’s Youth. Middle East Journal of Culture and Communication 6: 75–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boomsma, Anne. 1985. Nonconvergence, Improper Solutions, and Starting Values in Lisrel Maximum Likelihood Estimation. Psychometrika 50: 229–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Rupert, and Miles Hewstone. 2005. An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Contact. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Cambridge: Elsevier Academic Press, vol. 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burge, Stephen R. 2015. The Search for Meaning: Tafsīr, Hermeneutics, and Theories of Reading. Arabica 62: 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, Nick, and Michał Białek. 2021. Your Health vs. My Liberty: Philosophical Beliefs Dominated Reflection and Identifiable Victim Effects When Predicting Public Health Recommendation Compliance during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Cognition 212: 104649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calafato, Raees. 2020. Learning Arabic in Scandinavia: Motivation, Metacognition, and Autonomy. Lingua 246: 102943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelos, Tereza, and Alexia Katsanidou. 2018. Reactionary Politics: Explaining the Psychological Roots of Anti Preferences in European Integration and Immigration Debates. Political Psychology 39: 1271–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrani, Brahim. 2017. Between Profit and Identity: Analyzing the Effect of Language of Instruction in Predicting Overt Language Attitudes in Morocco. Applied Linguistics 38: 215–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Chao Min, Meng Hsiang Hsu, and Eric T. G. Wang. 2006. Understanding Knowledge Sharing in Virtual Communities: An Integration of Social Capital and Social Cognitive Theories. Decision Support Systems 42: 1872–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichocka, Aleksandra, Michał Bilewicz, John T. Jost, Natasza Marrouch, and Marta Witkowska. 2016. On the Grammar of Politics—or Why Conservatives Prefer Nouns. Political Psychology 37: 799–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen, Joel E. 2003. Human Population: The Next Half Century. Science 302: 1172–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, Kathleen, and Erica Owen. 2012. Islamic Religiosity and Regime Preferences: Explaining Support for Democracy and Political Islam in Central Asia and the Caucasus. Political Research Quarterly 65: 499–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dali, Mohd, Nuradli Ridzwan Shah, Shumaila Yousafzai, and Hanifah Abdul Hamid. 2019. Religiosity Scale Development. Journal of Islamic Marketing 10: 227–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgell, Penny. 2017. An Agenda for Research on American Religion in Light of the 2016 Election. Sociology of Religion: A Quarterly Review 78: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellermann, Antje, and Agustín Goenaga. 2019. Discrimination and Policies of Immigrant Selection in Liberal States. Politics and Society 47: 87–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshakry, Marwa S. 2008. Knowledge in Motion: The Cultural Politics of Modern Science Translations in Arabic. ISIS 99: 701–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitriani, Lili Karmela, and Linda Wulandari. 2021. Organizational Citizenship Behavior in the Construction of Islamic Boarding School: A Structural Model. Jurnal Minds: Manajemen Ide Dan Inspirasi 8: 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregson, Simon, Tom Zhuwau, Roy M. Anderson, and Stephen K. Chandiwana. 1999. Apostles and Zionists: The Influence of Religion on Demographic Change in Rural Zimbabwe. Population Studies 53: 179–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeri, Niloofor. 2003. Sacred Language, Ordinary People: Dilemmas of Culture and Politics in Egypt. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidt, Jonathan, and Jesse Graham. 2007. When Morality Opposes Justice: Conservatives Have Moral Intuitions That Liberals May Not Recognize. Social Justice Research 20: 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joe F., Jr., Lucy M. Matthews, Ryan L. Matthews, and Marko Sarstedt. 2017. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated Guidelines on Which Method to Use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis 1: 107–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joe F., Jr., Tomas M. Hult, Christian M. Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2014. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publisher. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joe F., Jr., William Black, Barry Babin, and Rolph Anderson. 2010. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective. In Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective. London: Pearson Education, vol. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Hatemi, Peter K., Rose Mcdermott, Lindon J. Eaves, Kenneth S. Kendler, and Michael C. Neale. 2013. Fear as a Disposition and an Emotional State: A Genetic and Environmentala Approach to Out-Group Political Preferences. American Journal of Political Science 57: 279–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, Marc D., Noam Chomsky, and W. Tecumseh Fitch. 2002. Neuroscience: The Faculty of Language: What Is It, Who Has It, and How Did It Evolve? Science 298: 1569–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hefner, Robert W. 2011. Civil Islam: Muslims and Democratization in Indonesia. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, Jörg, Christian M. Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2015. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 43: 115–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Herniti, Ening. 2016. Sapaan Dalam Ranah Keagamaan Islam (Analisis Sosiosemantik). Thaqafiyyat 15: 22–38. [Google Scholar]

- Heyat, Farideh. 2006. Globalization and Changing Gender Norms in Azerbaijan. International Feminist Journal of Politics 8: 394–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hout, Michael, and Claude S. Fischer. 2002. Why More Americans Have No Religious Preference: Politics and Generations. American Sociological Review 67: 165–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Howell, Julia D. 2005. Muslims, the New Age and Marginal Religions in Indonesia: Changing Meanings of Religious Pluralism. Social Compass 52: 473–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, Lindsay Pérez. 2016. Make America Great Again_Trump, Racist Nativism. Charleston Law Review 10: 215–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, Nur Amali. 2011. Producing Believers, Contesting Islam: Conservative and Liberal Muslim Students in Indonesia. Doctoral dissertation, New York University, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Imtyas, Rizkiyatul, Kusmana Kusmana, Alvin Rizal, and Didin Saepudin. 2020. Religional Source and Politics: A Case Study on The Hadith of ‘Loving The Arabs Is Faith and Hating Them Is Infidel’ and It’s Relevance in Indonesia Context. no. January. Available online: http://eprints.eudl.eu/id/eprint/1970/ (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Jost, John T., Chadly Stern, Nicholas O. Rule, and Joanna Sterling. 2017. The Politics of Fear: Is There an Ideological Asymmetry in Existential Motivation? Social Cognition 35: 324–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junusi, Rahman El, and Ferry Khusnul Mubarok. 2021. The Mediating Role of Innovation between Transglobal Leadership and Organizational Performance in Islamic Higher Education. Jurnal Minds: Manajemen Ide Dan Inspirasi 8: 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, Hanane. 2018. The Hijab and Work: Female Entrepreneurship in Response to Islamophobia. International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society 31: 421–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Käsehage, Nina. 2022. No Country for Muslims? The Invention of an Islam Républicain in France and Its Impact on French Muslims. Religions 13: 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, Rex B. 1998. Software Review: Software Programs for Structural Equation Modeling: Amos, EQS, and LISREL. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 16: 343–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, Ned. 2017. Common Method Bias: A Full Collinearity Assessmentmethod for PLS-SEM. In Partial Least Squares Path Modeling: Basic Concepts, Methodological Issues and Applications. Cham: Springer, pp. 245–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layman, Geoffrey C., and Thomas M. Carsey. 2002. Party Polarization and ‘Conflict Extension’ in the American Electorate. American Journal of Political Science 46: 786–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, Marie Nathalie. 1999. The Production of Islamic Identities through Knowledge Claims in Bouake, Cote d’Ivoire. African Affairs 98: 485–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Jamie Shinhee. 2004. Linguistic Hybridization in K-Pop: Discourse of Self-Assertion and Resistance. World Englishes 23: 429–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, Diana J., Diane M. Mackie, and Eliot R. Smith. 2011. Emotional Responses to Intergroup Apology Mediate Intergroup Forgiveness and Retribution. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 47: 1198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levchak, Philip J., and Charisse C. Levchak. 2020. Race and Politics: Predicting Support for 2016 Presidential Primary Candidates among White Americans. Sociological Inquiry 90: 172–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippold, Julia V., Julia I. Laske, Svea A. Hogeterp, Eilish Duke, Thomas Grünhage, and Martin Reuter. 2020. The Role of Personality, Political Attitudes and Socio-Demographic Characteristics in Explaining Individual Differences in Fear of Coronavirus: A Comparison Over Time and Across Countries. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacMaster, Neil. 2011. The Role of European Women and the Question of Mixed Couples in the Algerian Nationalist Movement in France, circa 1918–1962. French Historical Studies 34: 357–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maoz, Ifat, and Roy J. Eidelson. 2007. Psychological Bases of Extreme Policy Preferences: How the Personal Beliefs of Israeli-Jews Predict Their Support for Population Transfer in the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. American Behavioral Scientist 50: 1476–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavisakalyan, Astghik, Yashar Tarverdi, and Clas Weber. 2021. Heaven Can Wait: Future Tense and Religiosity. Journal of Population Economics, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menchik, Jeremy. 2016. Islam and Democracy in Indonesia: Tolerance without Liberalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscat, Danielle Marie, Roshana Kanagaratnam, Heather L. Shepherd, Kamal Sud, Kirsten McCaffery, and Angela Webster. 2018. Beyond Dialysis Decisions: A Qualitative Exploration of Decision-Making among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Adults with Chronic Kidney Disease on Haemodialysis. BMC Nephrology 19: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordenson, Jon. 2017. The Language of Online Activism. In The Politics of Written Language in the Arab World. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Outten, H. Robert, Michael T. Schmitt, Daniel A. Miller, and Amber L. Garcia. 2012. Feeling Threatened about the Future: Whites’ Emotional Reactions to Anticipated Ethnic Demographic Changes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 38: 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, Krystal M., Alexia Toskos Dils, and Stephen J. Flusberg. 2022. The Perceived Threat of Demographic Shifts Depends on How You Think the Economy Works. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations 25: 227–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, Mary Elizabeth. 2013. The Handless Maiden: Moriscos and the Politics of Religion in Early Modern Spain. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, Philip M., Scott B. MacKenzie, Jeong Yeon Lee, and Nathan P. Podsakoff. 2003. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology 88: 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzolatti, Giacomo, and Laila Craighero. 2004. The Mirror-Neuron System. Annual Review of Neuroscience 27: 169–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roscoe, John. T. 1975. Fundamental Research Statistics for The Behavioural Sciences, 2nd ed. New York: Holt Rinehart & Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Sanghro, Rafi Raza, and Jalil Ahmed Chandio. 2019. Emerging the Concept of Islamic Socialism in Pakistan: Historical Analysis on Political Debates of 1970-1971 Election Campaign. Journal of History Culture and Art Research 8: 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schuberth, Florian, Jörg Henseler, and Theo K. Dijkstra. 2018. Confirmatory Composite Analysis. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwörer, Jakob, and Xavier Romero-Vidal. 2020. Radical Right Populism and Religion: Mapping Parties’ Religious Communication in Western Europe. Religion, State and Society 48: 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, Heather J. 2008. Arab Identity and Ideology in Sudan: The Politics of Language, Ethnicity, and Race. African Affairs 107: 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shehata, Ahmed Maher Khafaga. 2019. Understanding Academic Reading Behavior of Arab Postgraduate Students. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science 51: 814–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherkat, Darren E., Melissa Powell-Williams, Gregory Maddox, and Kylan Mattias de Vries. 2011. Religion, Politics, and Support for Same-Sex Marriage in the United States, 1988–2008. Social Science Research 40: 167–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skitka, Linda J., Christopher W. Bauman, and Elizabeth Mullen. 2004. Political Tolerance and Coming to Psychological Closure Following the September 11, 2001, Terrorist Attacks: An Integrative Approach. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 30: 743–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, Eliot R., Charles R. Seger, and Diane M. Mackie. 2007. Can Emotions Be Truly Group Level? Evidence Regarding Four Conceptual Criteria. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 93: 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thomas, Justin, Aamna Al Shehhi, and Ian Grey. 2019. The Sacred and the Profane: Social Media and Temporal Patterns of Religiosity in the United Arab Emirates. Journal of Contemporary Religion 34: 489–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufan, Pinar, Karel De Witte, and Hein J. Wendt. 2019. Diversity-Related Psychological Contract Breach and Employee Work Behavior: Insights from Intergroup Emotions Theory. International Journal of Human Resource Management 30: 2925–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlmann, Allon. 2011. Policy Implications of Arabic Instruction in Israeli Jewish Schools. Human Organization 70: 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, Amritha. 2007. Religious Basis for Islamic Terrorism: The Quran and Its Interpretations. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 30: 229–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkuyten, Maykel. 2013. Justifying Discrimination against Muslim Immigrants: Outgroup Ideology and the Five-Step Social Identity Model. British Journal of Social Psychology 52: 345–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Xiaomei, and Daming Xu. 2018. The Mismatches between Minority Language Practices and National Language Policy in Malaysia: A Linguistic Landscape Approach. Kajian Malaysia 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winarni, Leni, Dafri Agussalim, and Zainal Abidin Bagir. 2019. Memoir of Hate Spin in 2017 Jakarta’s Gubernatorial Election; A Political Challenge of Identity against Democracy in Indonesia. Religió: Jurnal Studi Agama-Agama 9: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, Taro. 1967. Statistics, An Introductory Analysis. New York: Harper and Row Co. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Variable | Mean | St. Dev. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Political Preference | 3.569 | 0.841 | 1.000 | |||

| 2 | Fear of Demographic Change | 4.127 | 0.781 | −0.108 | 1.000 | ||

| 3 | Arabic Education | 3.513 | 0.68 | −0.265 | 0.229 | 1.000 | |

| 4 | Religiosity | 4.229 | 0.704 | −0.134 | −0.077 | 0.140 | 1.000 |

| Constructs | Indicators | Loading | Alpha | rho_A | CR | AVE | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabi2 | 0.607 | 1.118 | |||||

| Arabic Education | Arabi3 | 0.728 | 0.567 | 0.612 | 0.773 | 0.536 | 1.195 |

| Arabi5 | 0.843 | 1.270 | |||||

| FearDem1 | 0.859 | 1.267 | |||||

| Fear of demographic change | FearDem2 | 0.711 | 0.676 | 0.753 | 0.813 | 0.594 | 1.343 |

| FearDem3 | 0.733 | 1.345 | |||||

| PolP1 | 0.677 | 1.423 | |||||

| Political preference | PolP2 | 0.424 | 0.61 | 0.764 | 0.728 | 0.492 | 1.323 |

| PolP5 | 0.916 | 1.127 | |||||

| Religio1 | 0.816 | 1.600 | |||||

| Religio2 | 0.687 | 1.430 | |||||

| Religiosity | Religio4 | 0.821 | 0.743 | 0.808 | 0.824 | 0.490 | 1.775 |

| Religio5 | 0.611 | 1.306 | |||||

| Religio6 | 0.516 | 1.225 |

| Constructs | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Arabic Education | |||

| 2 | Fear of demographic change | 0.378 | ||

| 3 | Political preference | 0.419 | 0.173 | |

| 4 | Religiosity | 0.247 | 0.177 | 0.190 |

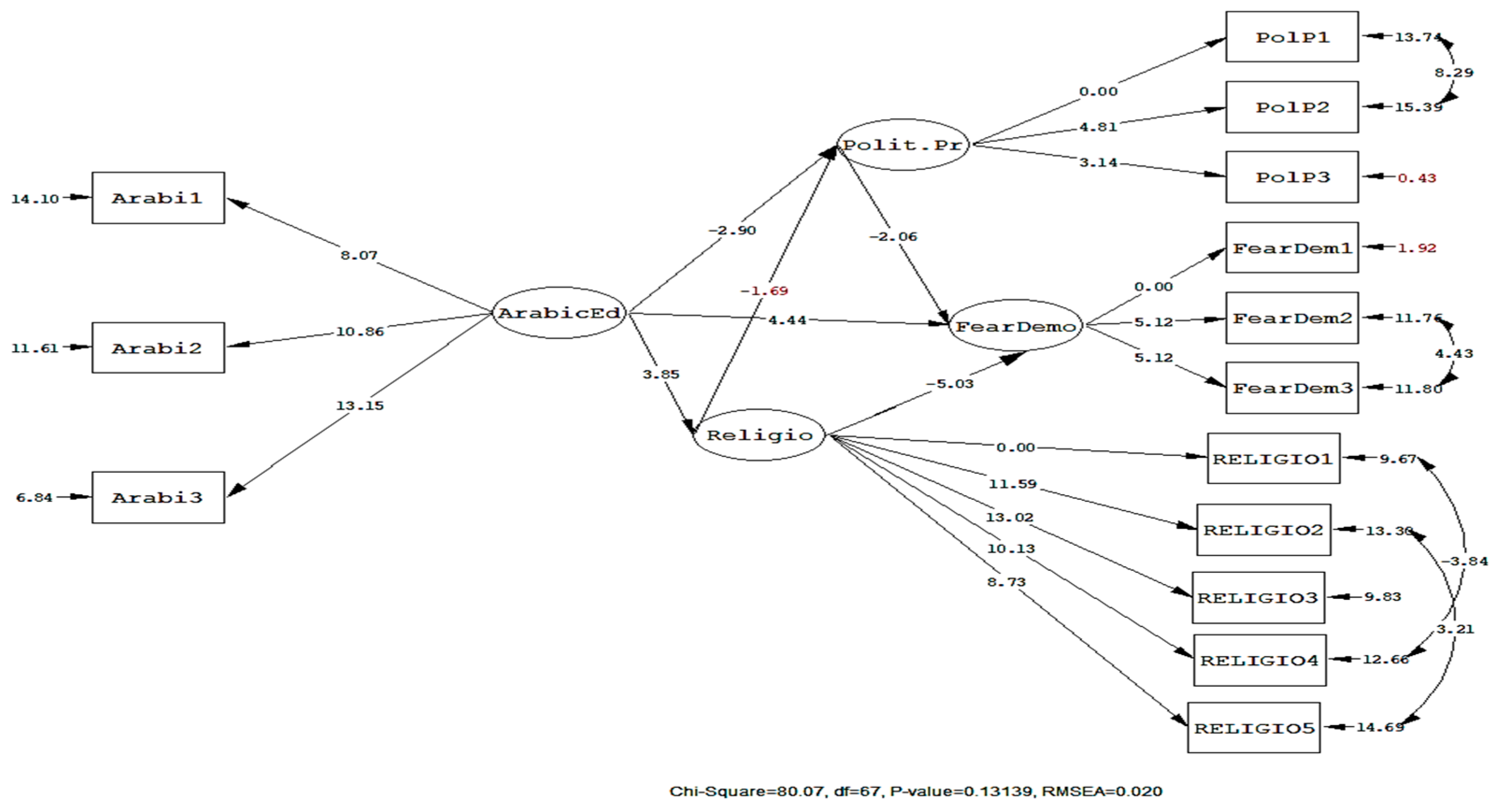

| Relationships | Effect | t-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Arabic Education -> Religiosity | 0.257 | 3.854 |

| Arabic Education -> Political preference | −0.216 | −2.903 |

| Arabic Education -> Fear of demographic change | 0.518 | 4.439 |

| Religiosity -> Political preference | −0.051 | −1.687 |

| Religiosity -> Fear of demographic change | −0.428 | −5.033 |

| Political preference -> Fear of demographic change | −0.398 | −2.056 |

| R2 to religiosity | 0.056 | |

| R2 to political preference | 0.204 | |

| R2 to fear of demographic change | 0.198 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nawas, K.A.; Masri, A.R.; Syariati, A. Indonesian Islamic Students’ Fear of Demographic Changes: The Nexus of Arabic Education, Religiosity, and Political Preferences. Religions 2022, 13, 320. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040320

Nawas KA, Masri AR, Syariati A. Indonesian Islamic Students’ Fear of Demographic Changes: The Nexus of Arabic Education, Religiosity, and Political Preferences. Religions. 2022; 13(4):320. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040320

Chicago/Turabian StyleNawas, Kamaluddin Abu, Abdul Rasyid Masri, and Alim Syariati. 2022. "Indonesian Islamic Students’ Fear of Demographic Changes: The Nexus of Arabic Education, Religiosity, and Political Preferences" Religions 13, no. 4: 320. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040320

APA StyleNawas, K. A., Masri, A. R., & Syariati, A. (2022). Indonesian Islamic Students’ Fear of Demographic Changes: The Nexus of Arabic Education, Religiosity, and Political Preferences. Religions, 13(4), 320. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040320