Transformations of Religiosity during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic—On the Example of Catholic Religious Practices of Polish Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Aim of This Study

1.2. These Social and Psychological Functions of Religion

1.3. Religiousness of Catholic Youth

1.4. The Pandemic in Poland and the Ability to Practice Religion

In view of the danger to health and life (according to can. 87 § 1, can. 1245 and can. 1248 § 2 of the Code of Canon Law), we recommend that diocesan bishops grant dispensations from the obligation to attend Mass on Sundays until March 29 to the following faithful: a. the elderly, b. persons with symptoms of infection (e.g., cough, runny nose, elevated temperature, etc.), c. school children and youth and their adult caregivers, d. persons who are afraid they will get infected. Dispensation means that it is not a sin to be absent from Sunday Mass at the indicated time. At the same time, we encourage those making use of the dispensation to practice individual and family prayer. We also encourage spiritual communion with the community of the Church through radio or television broadcast, or online streaming

2. Methods

2.1. Analyses

2.2. Participants

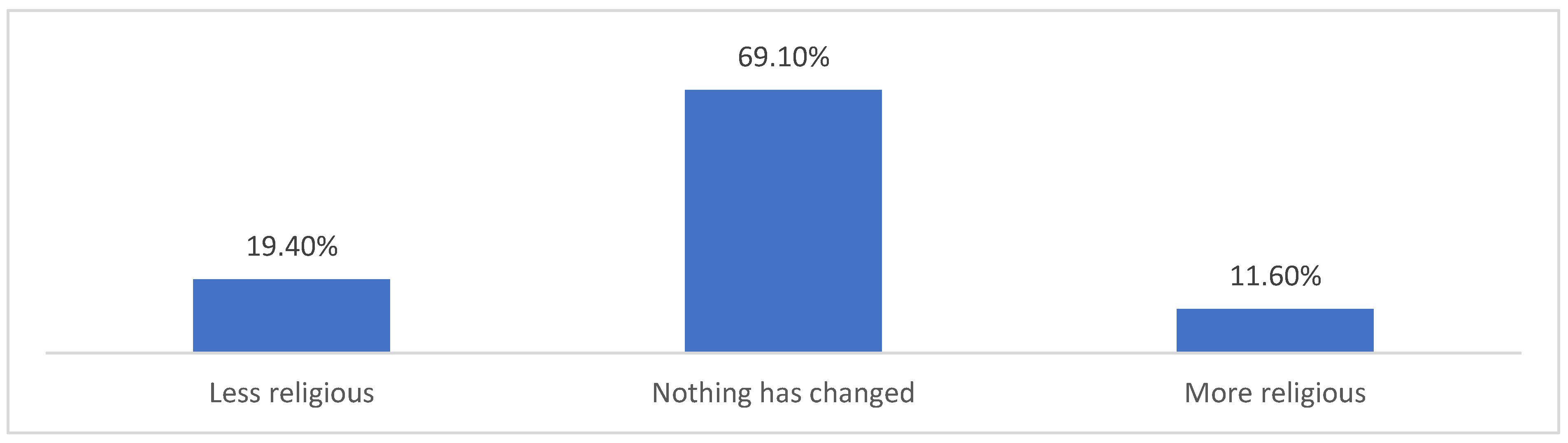

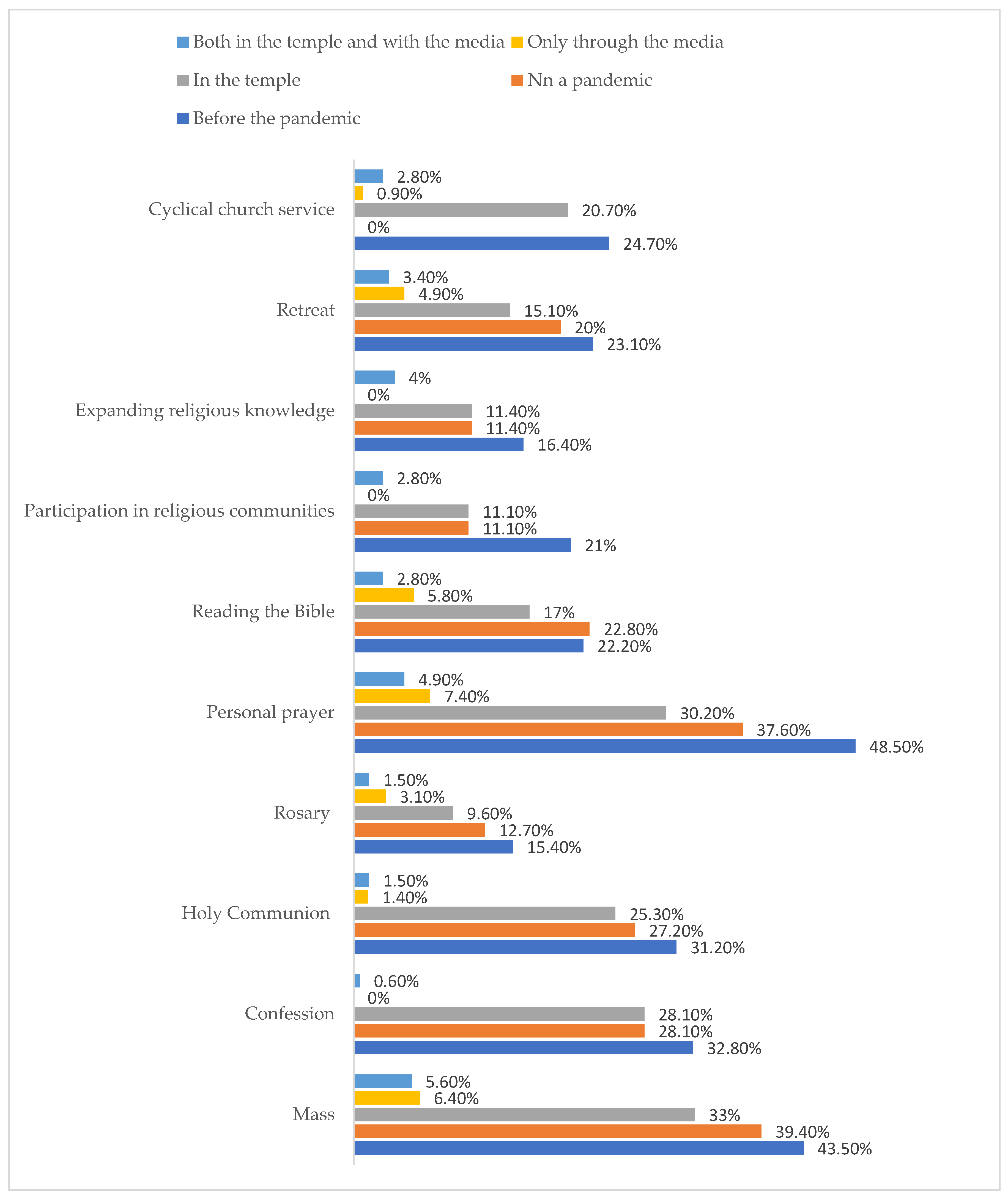

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Found them unhelpful in coping with the stress of the pandemic, religiosity ceased to be a coping strategy for them;

- Did not treat the pandemic as a limit situation which they coped with through religious practices, they did not feel directly threatened;

- Participants have made their previous practice of religion dependent on a physically experienced connection with other church members. When they lost it through the closing of the churches, the experience of loss of a personal relationship with the community was equated with the loss of a personal relationship with God. Participation in the practice of religion through the media did not prove to be an alternative to maintaining a personal relationship with God.

- d.

- Have relativized the so-called “church going” which is the essence of Polish Catholic life thus far. The bishops’ dispensation contributed to increasing doubt in the previous rules of religious life and proved to be an expected precedent.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bell, Daniel. 1993. Powrót sacrum. Tezy na temat przyszłości religii. In Człowiek–Wychowanie–Kultura. Edited by Franciszek Adamski. Kraków: WAM. [Google Scholar]

- Bentzen, Jeanet Sinding. 2021. In crisis, we pray: Religiosity and the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 192: 541–83. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter. 1969. A Rumor of Angels: Modern Society and the Rediscovery of the Supernatural. New York: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter. 2019. Refleksje o Dzisiejszej Socjologii Religii. Teologia Polityczna Co Tydzień 158. Available online: https://teologiapolityczna.pl/peter-l-berger-refleksje-o-dzisiejszej-socjologiireligii (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- Bożewicz, Marta. 2020a. Religijność Polaków w Ostatnich 20 Latach. Raport CBOS nr 63. Warszawa: Fundacja Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej. [Google Scholar]

- Bożewicz, Marta. 2020b. Religijność Polaków w Warunkach Pandemii. Raport CBOS nr 137. Warszawa: Fundacja Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej. [Google Scholar]

- Bullivant, Stephen. 2018. Europe’s Young Adults and Religion Findings from the European Social Survey (2014–16) to Inform the 2018 Synod of Bishops. Available online: https://www.stmarys.ac.uk/research/centres/benedict-xvi/docs/2018-mar-europe-young-people-report-eng.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- CBOS. 2015. Zmiany w Zakresie Podstawowych Wskaźników Religijności Polaków po Śmierci Jana Pawła II. Available online: http://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2015/K_026_15.PDF (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- CBOS. 2021. Religijność młodych na tle ogółu społeczeństwa. Available online: https://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2021/K_144_21.PDF (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- Chmura, Paweł Jan. 2009. Praktyki religijne w nauczaniu Kościoła ostatnich lat. Łódzkie Studia Teologiczne 18: 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ciesielski, Remigiusz. 2021. Oblicza prywatyzacji religijności w czasie pandemii. Przegląd Religioznawczy 2: 143–60. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, Emile. 1898. Représentations individuelles et Représentations collectives. Revue de Métaphysique et de Morale 6: 273–302. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, Emile. 1990. Elementarne Formy Życia Religijnego. Translated by Anna Zadrożyńska. Warszawa: PWN. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman, Susan, and Judith Tedlie Moskowitz. 2004. Coping: Pitfalls and promise. Annual Review of Psychology 55: 745–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giddens, Anthony. 2004. Socjologia. Warszawa: PWN. [Google Scholar]

- Grabowska, Mirosława. 2018. Bóg a sprawa polska. Poza granicami teorii sekularyzacji. Warszawa: Scholar. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, Daniel R. 1971. Ritual and Conformity: A Religious Pilgrimage to Northeastern Brazil. Ethnology 10: 129–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzik, Aldona, and Radosław Marzęcki. 2018. Niemoralna religijność. Wzory religijności i moralności młodego pokolenia Polaków. Roczniki Nauk Społecznych 10: 123–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hall, Dorota, and Marta Kołodziejska. 2021. Covid-19 pandemic, mediatization and the Polish sociology of religion. Polish Sociological Review 213: 123–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horx, Matthias. 1993. Trendbuch. Munchen: Econ. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington, Samuel P. 2005. Zderzenie cywilizacji i nowy kształt ładu światowego. Translated by Hanna Jankowska. Warszawa: Zysk i S-ka. [Google Scholar]

- Hutsebaut, Dirk. 1980. Belief as livd relations. Psychologica Belgica 20: 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacyniak, Aleksander, and Zenomena Płużek. 1996. Świat Ludzkich Kryzysów. Kraków: WAM. [Google Scholar]

- Jarosz, Marek. 2004. Interpersonalne Uwarunkowania Religijności. Lublin: Towarzystwo Naukowe KUL. [Google Scholar]

- Knoblauch, Hubert. 1996. “Niewidzialna religia” Thomasa Luckmanna, czyli o przemianie religii w religijność. In Niewidzialna Religia. Edited by Thomas Luckmann. Kraków: Nomos, pp. 7–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kracht, Benjamin. 2018. Religious Revitalization among the Kiowas: The Ghost Dance, Peyote, and Christianity. Lincoln: The University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krok, Dariusz. 2005. Religia a funkcjonowanie osobowości człowieka. Studia Teologiczno-Historyczne Śląska Opolskiego 25: 87–112. [Google Scholar]

- Le Bras, Gabriel. 1969. Problemy socjologii religii. Człowiek i Światopogląd 1: 70–79. [Google Scholar]

- Lienkamp, Christoph. 2003. Wiederkehr der Religion als Zeichen epochalen Umbruchs—Leistung und Grenzen religionssoziologischer Deutungen in philosophischer und systematisch-theologischer. JCSW 44: 273–301. [Google Scholar]

- Mariański, Janusz. 2010. Religia w społeczeństwie ponowoczesnym. Studium socjologiczne. Warszawa: Oficyna Naukowa. [Google Scholar]

- Mayrl, Damon, and Jeremy E. Uecker. 2011. Higher Education and Religious Liberalization among Young Adults. Social Forces 90: 181–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meza, Diego. 2020. In a Pandemic Are We More Religious? Traditional Practices of Catholics and the COVID-19 in Southwestern Colombia. International Journal of Latin American Religions 4: 218–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikołajczak, Sylwia. 2021. Uczestnictwo w niedzielnej Mszy świętej podczas trwania pandemii Covid-19. Studium empiryczne, Studia Warmińskie 58: 371–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewska-Dyoniziak, Babara. 2002. Człowiek i Religia. Studium z Zakresu Genezy i Społecznej Funkcji Religii. Wrocław: Atla 2. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, Rudolf. 1993. Świętość. Elementy Racjonalne i Irracjonalne w Pojęciu Bóstwa. Wrocław: Thesaurus Press. [Google Scholar]

- Özer, Zülfünaz, Meyreme Aksoy, and Gülcan Bahcecioglu Turan. 2022. The Relationship Between Death Anxiety and Religious Coping Styles in Patients Diagnosed With COVID-19: A Sample in the East of Turkey. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying 2021: 00302228211065256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Crystal L. 2005a. Religion and meaning. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Edited by Raymond F. Paloutzian and Crystal L. Park. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 295–314. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Crystal L. 2005b. Religion as a meaning-making framework in coping with life stress. Journal of Social Issues 61: 707–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Crystal L. 2007. Religious and spiritual issues in health and aging. In Handbook of Health Psychology and Aging. Edited by Carolyn M. Aldwin, Crystal L. Park and Avron Spiro. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 313–40. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Crystal L., and Lawrence H. Cohen. 1993. Religious and nonreligious coping with the death of a friend. Cognitive Therapy and Research 6: 561–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Crystal L., Marc R. Malone, D. P. Suresh, D. Bliss, and Rivkah I. Rosen. 2008. Coping, meaning in life, and quality of life in congestive heart failure patients. Quality of Life Research 17: 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PC of the Polish Bishops’ Conference. 2020. Ordinance 1/2020. Available online: https://archwwa.pl/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Zarz%C4%85dzenie-nr-1_2020-Rady-Sta%C5%82ej-KEP-z-12-marca-2020.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- Pew Research Center. 2021. “More Americans Than People in Other Advanced Economies Say COVID-19 Has Strengthened Religious Faith” by Neha Sahgal, Aidan Connaughton. Available online: https://www.pewforum.org/2021/01/27/more-americans-than-people-in-other-advanced-economies-say-covid-19-has-strengthened-religious-faith/ (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- Piwowarski, Władysław. 1977. Religia Miejska w Rejonie Uprzemysłowionym. Studium Socjologiczne, Warszawa: Biblioteka Więzi. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, Keisha, Paul J. Handal, Eddie M. Clark, and Jillon S. Vander Wal. 2009. The Relationship Between Religion and Religious Coping: Religious Coping as a Moderator Between Religion and Adjustment. Journal of Religion and Health 48: 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Różański, Tomasz. 2016. The Faces of Religiousness of Student Youth—The Analysis of Selected Components. Paedagogia Christiana 35: 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydz, Elżbieta. 2014. Development of religiousness in young adults. In Functioning of Young Adults in a Changing World. Edited by Katarzyna Adamczyk and Monika Wysota. Kraków: Libron, pp. 67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Sliwak, J. 2006. Niepokój a religijność. Roczniki Psychologiczne 11: 53–81. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Christian, and Patricia Snell. 2009. Souls in Transition: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of Emerging Adults. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stachowska, Ewa. 2019. Religijność młodzieży w Europie—Perspektywa socjologiczna. Kontynuacje. Przegląd Religioznawczy 3: 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Walesa, Czesław. 2005. Rozwój religijności człowieka. Lublin: Wydawnictwo KUL. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Max. 1993. The Sociology of Religion. Boston: Beacon Press. First published 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Max. 1968. Economy and Society. Bedminster: Bedminster Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Max. 1994. Etyka Protestancka a Duch Kapitalizmu. Translated by J. Miziński. Lublin: Wydawnistwo TEST. [Google Scholar]

- Zaręba, Sławomir Henryk, and Janusz Mariański. 2021. Religia jako wartość w czasie pandemii. Analizy socjologiczne. Journal of Modern Science Tom 46: 13–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaręba, Sławomir Henryk, and Marcin Zarzecki, eds. 2018. Między konstrukcją a dekonstrukcją uniwersum znaczeń. Badanie religijności młodzieży akademickiej w latach 1988–1998–2005–2017. Warszawa: Warszawskie Wydawnictwo Socjologiczne. [Google Scholar]

- Zdybicka, Zofia. 1977. Człowiek i Religia. Lublin: Towarzystwo Naukowe KUL. [Google Scholar]

- Zulehner, Paul Michael. 2004. Spiritualität—Mehr als ein Megatrend. Ostfldern: Schwabenverlag. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dobosz, D.; Gierczyk, M.; Janiak, A.; Piasecki, D.; Rajba, B. Transformations of Religiosity during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic—On the Example of Catholic Religious Practices of Polish Students. Religions 2022, 13, 308. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040308

Dobosz D, Gierczyk M, Janiak A, Piasecki D, Rajba B. Transformations of Religiosity during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic—On the Example of Catholic Religious Practices of Polish Students. Religions. 2022; 13(4):308. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040308

Chicago/Turabian StyleDobosz, Dagmara, Marcin Gierczyk, Agnieszka Janiak, Dariusz Piasecki, and Beata Rajba. 2022. "Transformations of Religiosity during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic—On the Example of Catholic Religious Practices of Polish Students" Religions 13, no. 4: 308. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040308

APA StyleDobosz, D., Gierczyk, M., Janiak, A., Piasecki, D., & Rajba, B. (2022). Transformations of Religiosity during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic—On the Example of Catholic Religious Practices of Polish Students. Religions, 13(4), 308. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040308