The Political Discourse of the Church of Greece during the Crisis: An Empirical Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Religion and Politics in Greece

3. Data, Methodology, and Research Questions

4. Discussion and Findings

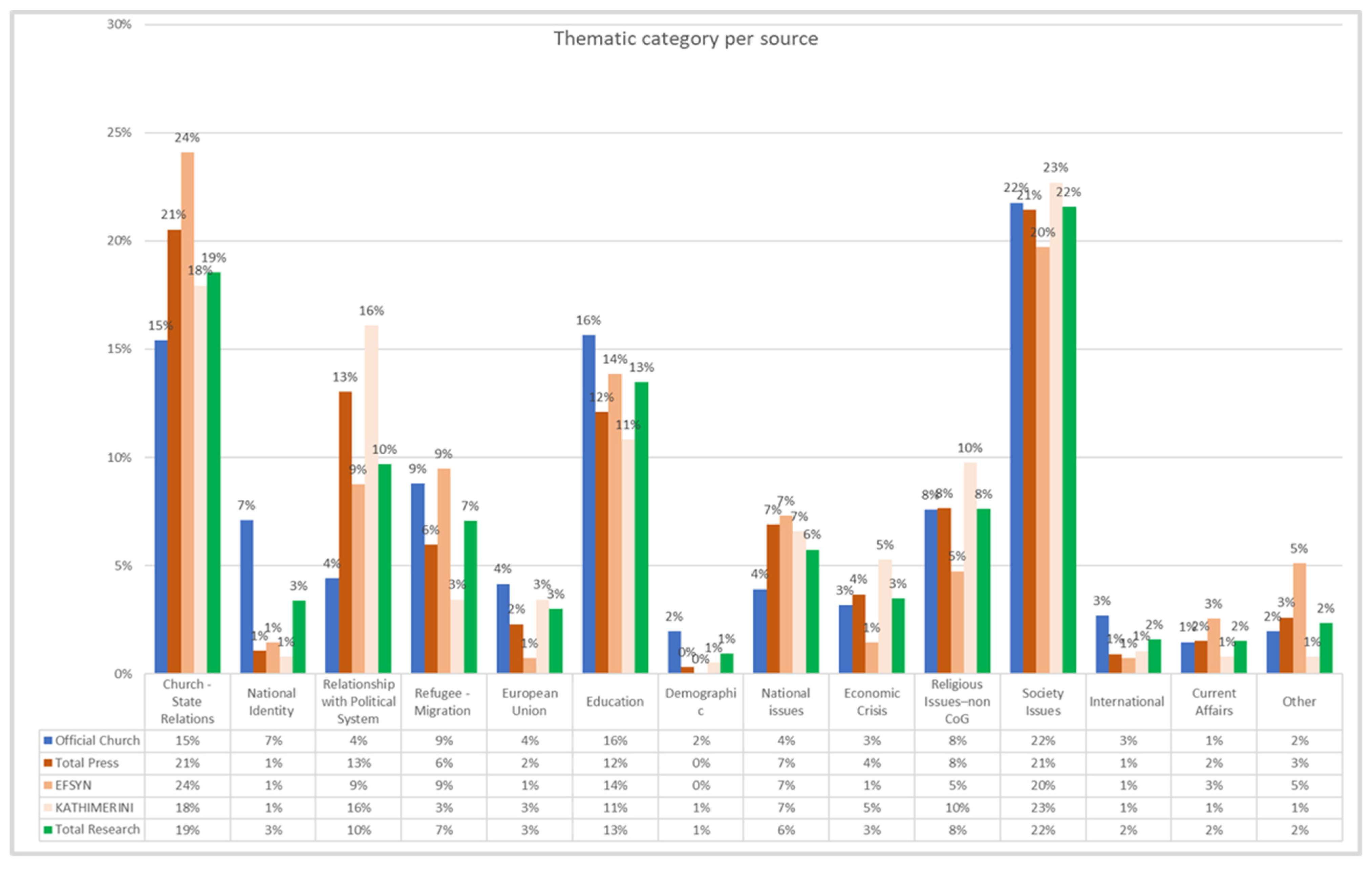

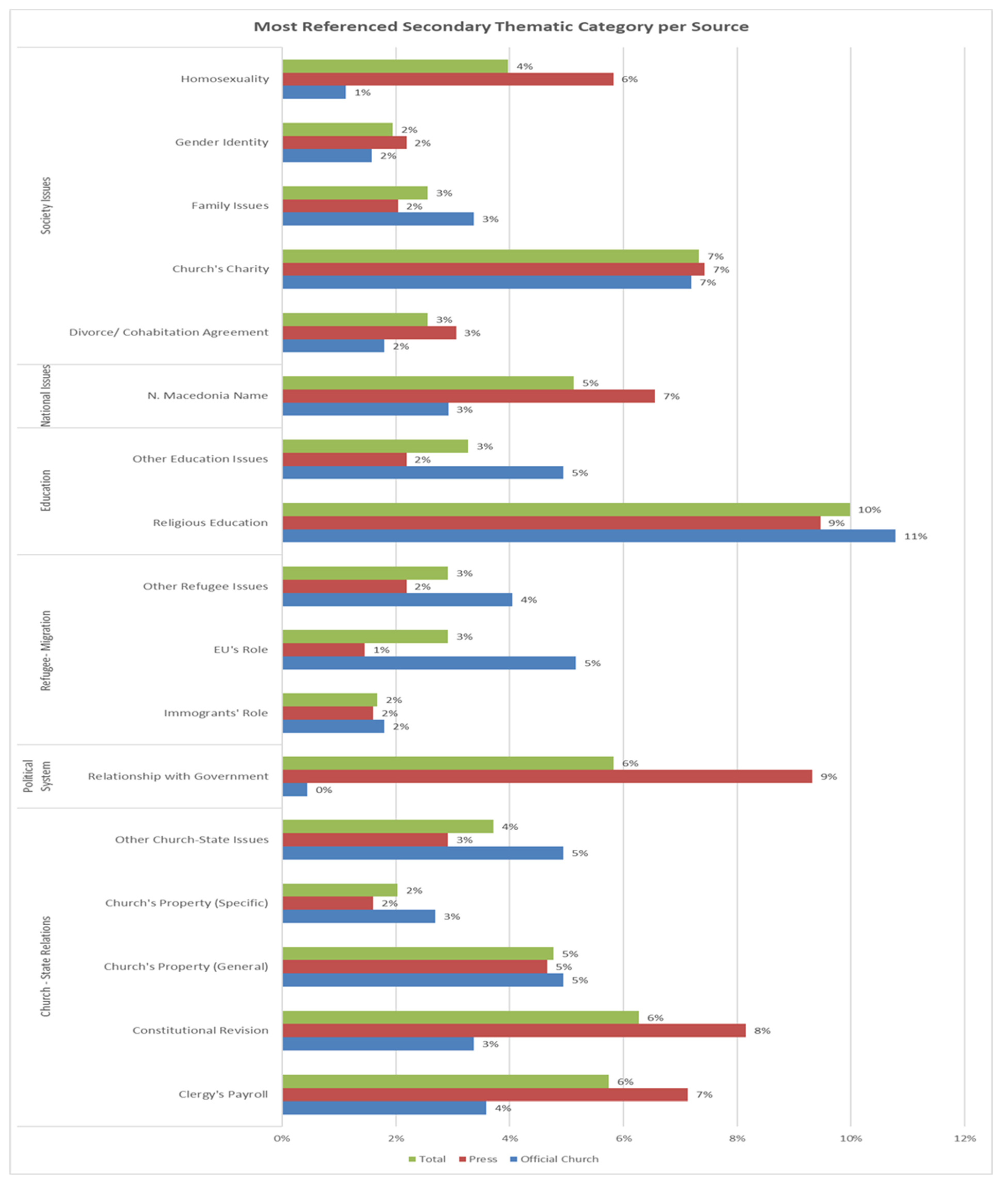

4.1. Main Issues Discussed by the Church of Greece

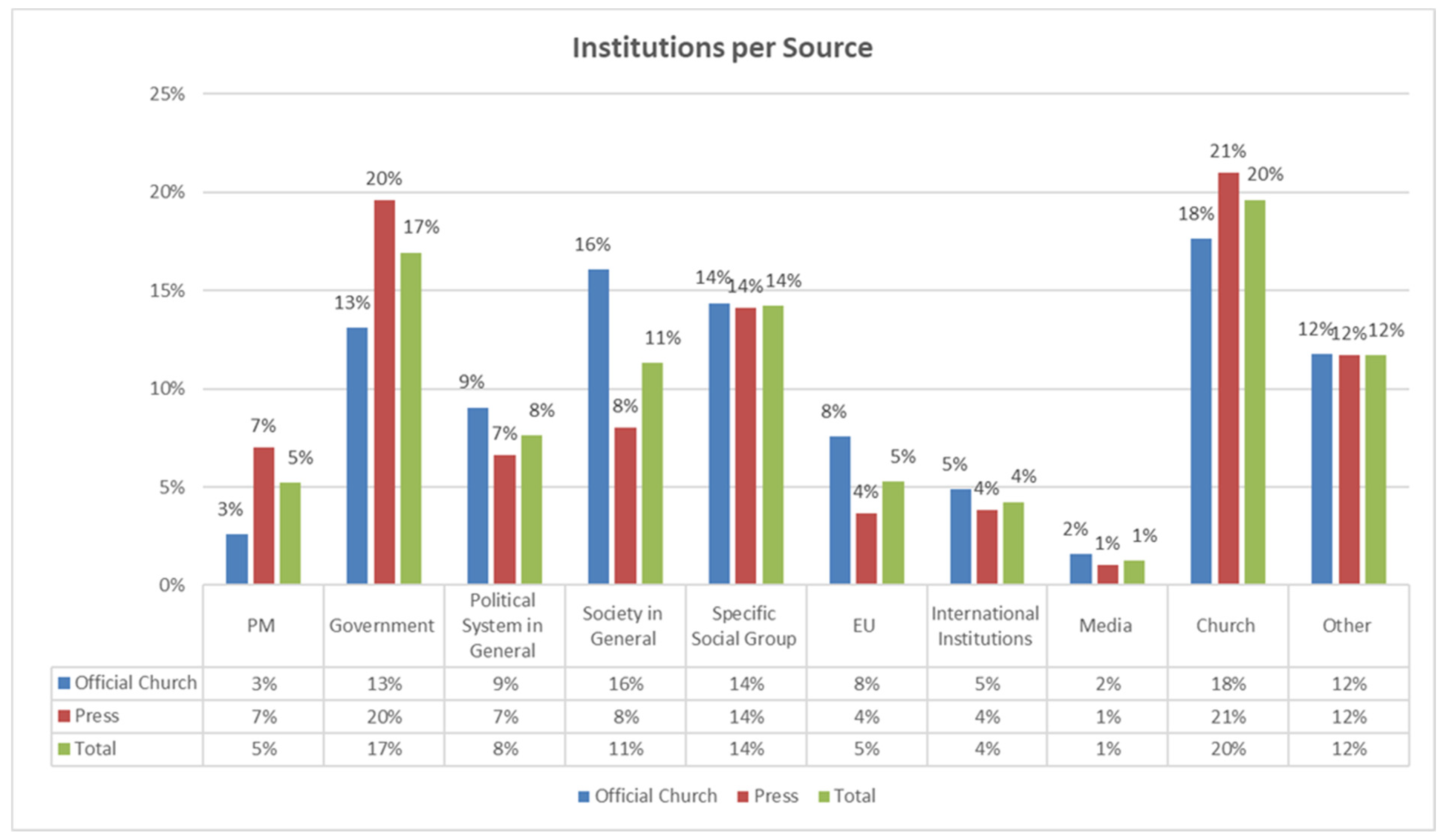

4.2. Main Institutions Discussed by the Church of Greece

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | For the ideological orientation of the EFSYN and Kathimerini, see (Nikisianis et al. 2019; Papathanassopoulos et al. 2021). As for the relation between the political discourse of the CoG and the two newspapers monitored in our research, there are no studies concentrating specifically on this relation. A few papers use the two newspapers as sources in order to cover specific research questions as case studies (e.g., the Greek ID card controversy, church–state relations) within a qualitative methodological framework (Molokotos-Liederman 2007) or from the point of view of conceptual analysis (Kessareas 2019) without focusing on the newspaper coverage of the discourse of the CoG. These articles are already included in our analysis and appear in the reference list of the paper. |

| 2 | For the newspaper circulation statistics in Greece see: https://www.eihea.com.gr/eihea.php?contentid=67 (Athens Daily Newspaper Publishers Association, accessed on 17 March 2022) and http://www.argoscom.gr/index.php?page=17 (ARGOS SA: Press & Book Distribution Agency, accessed on 17 March 2022). See also Papathanassopoulos et al. (2021, p. 200). |

| 3 | The statistical program used for the current research is IBM SPSS Statistics 26. |

| 4 | Due to space limitations and for better understanding of the analysis, in several cases, only the definition “official church” or “press” is used. In all these cases, the two identifications should be understood as referring to statements and positions made by CoG representatives and either expressed through the official website of the CoG (“official church”) or through the two newspapers (“press”) included in our research. |

References

- Alivizatos, Nikos. 1999. A New Role for the Greek Church? Journal of Modern Greek Studies 17: 23–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benford, Robert D., and David A. Snow. 2000. Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment. Annual Review of Sociology 26: 611–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, Porismita. 2011. Conceptual Issues in Framing Theory: A Systematic Examination of a Decade’s Literature. Journal of Communication 61: 246–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, José. 1994. Public Religions in the Modern World. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, José. 2003. What is Public Religion. In Religion Returns to the Public Square: Faith and Policy in America. Edited by Hugh Heclo and Wilfred M. McClay. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, pp. 111–39. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, Juliet, and Anselm Strauss. 2008. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Demertzis, Nikos. 2001. “Hē ethnothreskeftikē kai epikinōniakē ekkosmíkefsi tēs Orthodoxías”. [The Ethno-Religious and Communicative Secularisation of Orthodoxy]. Epistēme kai koinōnía [Science and Society] 5–6: 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirikx, Astrid, and Dave Gelders. 2010. To Frame is to Explain: A Deductive Frame–Analysis of Dutch and French Climate Change Coverage during the Annual UN Conferences of the Parties. Public Understanding of Science 19: 732–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragonas, Thalia. 2013. Religion in Contemporary Greece—A Modern Experience? In The Greek Crisis and European Modernity. Edited by Anna Triandafyllidou, Ruby Gropas and Hara Kouki. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 110–31. [Google Scholar]

- Druckman, James N., and Kjersten R. Nelson. 2003. Framing and Deliberation: How Citizens’ Conversations Limit Elite Influence. American Journal of Political Science 47: 729–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Issawi, Fatima. 2021. Media Pluralism and Democratic Consolidation: A Recipe for Success? The International Journal of Press/Politics 26: 861–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, Satu, and Helvi Kyngäs. 2008. The Qualitative Content Analysis Process. Journal of Advanced Nursing 62: 107–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, Robert M. 1993. Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. Journal of Communication 43: 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokas, Effie. 2009. Religion in the Greek Public Sphere: Nuancing the Account. Journal of Modern Greek Studies 27: 349–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokas, Effie. 2010. Religion and Welfare in Greece: A New, or Renewed, Role for the Church? In Orthodox Christianity in 21st Century Greece: The Role of Religion in Culture, Ethnicity, and Politics. Edited by Victor Roudometof and Vasilios N. Makrides. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 175–92. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiadou, Vassiliki. 1995. Greek Orthodoxy and the Politics of Nationalism. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 9: 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiadou, Vassiliki. 2009. Dieurínontas tēn oratótita tēs Ekklesías stē demósia sphéra. Schésis Orthódokses Ekklesías kai ellenikēs koinōnías epí Archiepiskópou Christódoulou. [Broadening the Visibility of the Church in the Public Sphere: The Relations between Orthodox Church and Greek Society under Archbishop Christodoulos]. Epistēme kai koinōnía [Science and Society] 21: 129–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Georgiadou, Vassiliki, and Elias Nikolakopoulos. 2002. Typoi threskephtikēs désmefses kai ekklesiastikē praktikē. Mia empirikē análysi [Types of Religious Engagement, Ecclesiastical Practice, and Political Preferences. An Empirical Approach]. In Threskíes kai politikē ste neoterikóteta [Religions and Politics in Modernity]. Edited by Thanos Lipowatz, Nikos Demertzis and Vassiliki Georgiadou. Athens: Kritiki, pp. 254–79. [Google Scholar]

- Guzek, Damian. 2019. Mediatizing Secular State: Media, Religion and Politics in Contemporary Poland. Berlin: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Hallin, Daniel C., and Paolo Mancini. 2004. Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Iosifidis, Petros, and Dimitris Boucas. 2015. Media Policy and Independent Journalism in Greece. New York: Open Society Foundations. [Google Scholar]

- Itçaina, Xabier. 2019. The Spanish Catholic Church, the Public Sphere, and the Economic Recession: Rival Legitimacies? Journal of Contemporary Religion 34: 153–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, Shanto. 1991. Is Anyone Responsible? How Television Frames Political Issues. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar, Shanto. 1996. Framing Responsibility for Political Issues. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 546: 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, Hank, and John A. Noakes. 2005. Frames of Protest: Social Movements and the Framing Perspective. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Karagiannis, Evangelos. 2009. Secularism in Context: The Relations between the Greek State and the Church of Greece in Crisis. European Journal of Sociology 50: 133–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessareas, Efstathios. 2019. The Orthodox Church of Greece and Civic Activism in the Context of the Financial Crisis. In Religious Communities and Civil Society in Europe. Edited by Rupert Graf Strachwitz. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, pp. 61–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kountouri, Fani, and Afroditi Nikolaidou. 2019. Bridging Dominant and Critical Frames of the Greek Debt Crisis: Mainstream Media, Independent Journalism and the Rise of a Political Cleavage. Journal of Contemporary European Studies 27: 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesniczak, Rafal. 2016. The Communicative Role of the Catholic Church in Poland in the 2015 Presidential Election and its Perception by the Public. Church, Communication and Culture 1: 268–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makrides, Vasilios N. 2010. Scandals, Secret Agents and Corruption: The Orthodox Church of Greece during the 2005 Crisis—Its Relation to the State and Modernisation. In Orthodox Christianity in 21st Century Greece: The Role of Religion in Culture, Ethnicity, and Politics. Edited by Victor Roudometof and Vasilios N. Makrides. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 61–87. [Google Scholar]

- Makris, Gerasimos, and Dimitris Bekridakis. 2013. The Greek Orthodox Church and the Economic Crisis since 2009. International Journal for the Study of the Christian Church 13: 111–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makris, Gerasimos, and Vasilios Meichanetsidis. 2018. The Church of Greece in Critical Times: Reflections through Philanthropy. Journal of Contemporary Religion 33: 247–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manitakis, Antonis. 2000. Oi Schésis tes Ekklesías Me to Krátos-Ethnos. [The Relations between the Church and the Nation-State]. Athens: Nefeli. [Google Scholar]

- Mavrogordatos, George. 2003. Orthodoxy and Nationalism in the Greek Case. West European Politics 26: 117–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombs, Maxwell, and Tamara Bell. 1996. The agenda-setting role of mass communication. In An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research. Edited by Michael B. Salwen and Don W. Stacks. Mahwah: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates, pp. 93–110. [Google Scholar]

- Molokotos-Liederman, Lina. 2007. The Greek ID Card Controversy: A Case Study of Religion and National Identity in a Changing European Union. Journal of Contemporary Religion 22: 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molokotos-Liederman, Lina. 2016. The Impact of the Crisis on the Orthodox Church of Greece: A Moment of Challenge and Opportunity? Religion, State and Society 44: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molokotos-Liederman, Lina. 2019. L’Église orthodoxe de Grèce face à la crise économique. [The Orthodox Church of Greece in View of the Economic Crisis]. Archives de Sciences Sociales de Religions 185: 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikisianis, Nikos, Thomas Siomos, Yannis Stavrakakis, Titika Dimitroulia, and Grigoris Markou. 2019. Populism Versus Anti-Populism in the Greek Press: Post-Structuralist Discourse Theory Meets Corpus Linguistics. In Discourse, Culture and Organization: Inquiries into Relational Structures of Power. Edited by Tomas Marttila. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 267–95. [Google Scholar]

- Papastathis, Konstantinos. 2015. Religious Discourse and Radical Right Politics in Contemporary Greece, 2010–2014. Politics, Religion, and Ideology 16: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathanassopoulos, Stylianos, Achilleas Karadimitriou, Christos Kostopoulos, and Ioanna Archontaki. 2021. Greece: Media Concentration and Independent Journalism between Austerity and Digital Disruption. In The Media for Democracy Monitor 2021: How Leading News Media Survive Digital Transformation (Vol. 2). Edited by Josef Trappel and Tales Tomaz. Gothenburg: Nordicom/University of Gothenburg, pp. 177–230. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, Daniel P. 2003. The Clash of Civilisations: The Church of Greece, the European Union and the Question of Human Rights. Religion, State, and Society 31: 261–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodromou, Elizabeth H. 2004. Christianity and Democracy: The Ambivalent Orthodox. Journal of Democracy 15: 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roudometof, Victor. 2008. Greek Orthodoxy, Territoriality, and Globality: Religious Responses and Institutional Disputes. Sociology of Religion 69: 67–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roudometof, Victor. 2011. Eastern Orthodox Christianity and the Uses of the Past in Contemporary Greece. Religions 2: 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheufele, Dietram A. 1999. Framing as a Theory of Media Effects. Journal of Communication 49: 103–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheufele, Dietram A., and Matthew C. Nisbet. 2008. Framing. In Encyclopedia of Political Communication. Edited by Lynda L. Kaid and Christina Holtz-Bacha. Los Angeles: Sage Publications, pp. 254–57. [Google Scholar]

- Semetko, Holli A., and Patti M. Valkenburg. 2000. Framing European Politics: A Content Analysis of Press and Television News. Journal of Communication 50: 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, David A. 2001. Collective Identity and Expressive Forms. UC Irvine: CSD Working Papers. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2zn1t7bj (accessed on 26 January 2022).

- Stathopoulou, Theoni. 2010. Faith and Trust: Tracking Patterns of Religious and Civic Commitment in Greece and Europe. An Empirical Approach. In Orthodox Christianity in 21st Century Greece: The Role of Religion in Culture, Ethnicity, and Politics. Edited by Victor Roudometof and Vasilios N. Makrides. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 193–216. [Google Scholar]

- Stavrakakis, Yannis. 2003. Politics and Religion: On the “Politicization” of Greek Church Discourse. Journal of Modern Greek Studies 21: 153–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verloo, Mieke. 2005. Mainstreaming Gender Equality in Europe. A Critical Frame Analysis Approach. The Greek Review of Social Research 117 B: 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Official Church | Press | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identity Frame | Blame Frame | Prognosis Frame | Moral Frame | Mobilisation Frame | Identity Frame | Blame Frame | Prognosis Frame | Moral Frame | Mobilisation Frame | |

| Church—State Relations | 24% | 8% | 32% | 3% | 32% | 11% | 9% | 36% | 0% | 43% |

| National Identity | 76% | 0% | 0% | 12% | 12% | 63% | 0% | 0% | 13% | 25% |

| Relationship with Political System | 18% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 82% | 18% | 8% | 1% | 1% | 71% |

| Refugee—Migration | 2% | 20% | 7% | 17% | 54% | 5% | 12% | 2% | 15% | 66% |

| European Union | 21% | 11% | 5% | 32% | 32% | 16% | 11% | 0% | 32% | 42% |

| Education | 25% | 6% | 33% | 4% | 32% | 17% | 1% | 28% | 5% | 49% |

| Demographic | 7% | 14% | 21% | 14% | 43% | 0% | 50% | 0% | 0% | 50% |

| National Issues | 24% | 12% | 12% | 0% | 53% | 21% | 11% | 21% | 0% | 47% |

| Economic Crisis | 8% | 38% | 0% | 15% | 38% | 0% | 0% | 4% | 22% | 74% |

| Religious Issues–non-CoG | 31% | 6% | 16% | 6% | 41% | 15% | 4% | 17% | 6% | 59% |

| Society Issues | 16% | 1% | 10% | 20% | 53% | 7% | 7% | 10% | 18% | 59% |

| International | 9% | 0% | 0% | 27% | 64% | 17% | 0% | 17% | 0% | 67% |

| Current Affairs | 17% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 83% | 33% | 11% | 11% | 0% | 44% |

| Other | 13% | 38% | 0% | 0% | 50% | 29% | 12% | 0% | 6% | 53% |

| Total | 23% | 8% | 16% | 11% | 43% | 13% | 7% | 17% | 8% | 55% |

| Official Church | Press | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identity Frame | Blame Frame | Prognosis Frame | Moral Frame | Mobilisation Frame | Identity Frame | Blame Frame | Prognosis Frame | Moral Frame | Mobilisation Frame | |

| PM | 12% | 12% | 36% | 0% | 40% | 13% | 8% | 20% | 0% | 60% |

| Government | 17% | 5% | 34% | 6% | 39% | 13% | 9% | 23% | 4% | 51% |

| Political System in General | 28% | 10% | 18% | 6% | 38% | 18% | 7% | 21% | 6% | 48% |

| Society in General | 26% | 11% | 8% | 20% | 35% | 11% | 6% | 14% | 15% | 54% |

| Specific Social Group | 17% | 6% | 11% | 12% | 54% | 6% | 7% | 9% | 16% | 62% |

| EU | 20% | 16% | 15% | 18% | 32% | 15% | 14% | 10% | 15% | 46% |

| International Institutions | 10% | 12% | 10% | 10% | 60% | 11% | 4% | 15% | 11% | 59% |

| Media | 31% | 38% | 8% | 0% | 23% | 7% | 29% | 0% | 7% | 57% |

| Church | 25% | 5% | 18% | 7% | 45% | 15% | 7% | 16% | 4% | 58% |

| Other | 24% | 3% | 19% | 4% | 50% | 16% | 7% | 15% | 3% | 58% |

| Total | 22% | 8% | 17% | 10% | 43% | 13% | 8% | 16% | 7% | 56% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaltsas, S.; Karoulas, G.; Karayiannis, Y.; Kountouri, F. The Political Discourse of the Church of Greece during the Crisis: An Empirical Approach. Religions 2022, 13, 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040273

Kaltsas S, Karoulas G, Karayiannis Y, Kountouri F. The Political Discourse of the Church of Greece during the Crisis: An Empirical Approach. Religions. 2022; 13(4):273. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040273

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaltsas, Spyridon, Gerasimos Karoulas, Yiannis Karayiannis, and Fani Kountouri. 2022. "The Political Discourse of the Church of Greece during the Crisis: An Empirical Approach" Religions 13, no. 4: 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040273

APA StyleKaltsas, S., Karoulas, G., Karayiannis, Y., & Kountouri, F. (2022). The Political Discourse of the Church of Greece during the Crisis: An Empirical Approach. Religions, 13(4), 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13040273