Memory of Conflicts and Perceived Threat as Relevant Mediators of Interreligious Conflicts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theories and Hypotheses

2.1. Religious Identity

2.2. Religious Practice

2.3. Religious Beliefs

2.4. Religious Salience

2.5. Memory of Conflicts

2.6. Perceived Threat

3. Materials and Methods

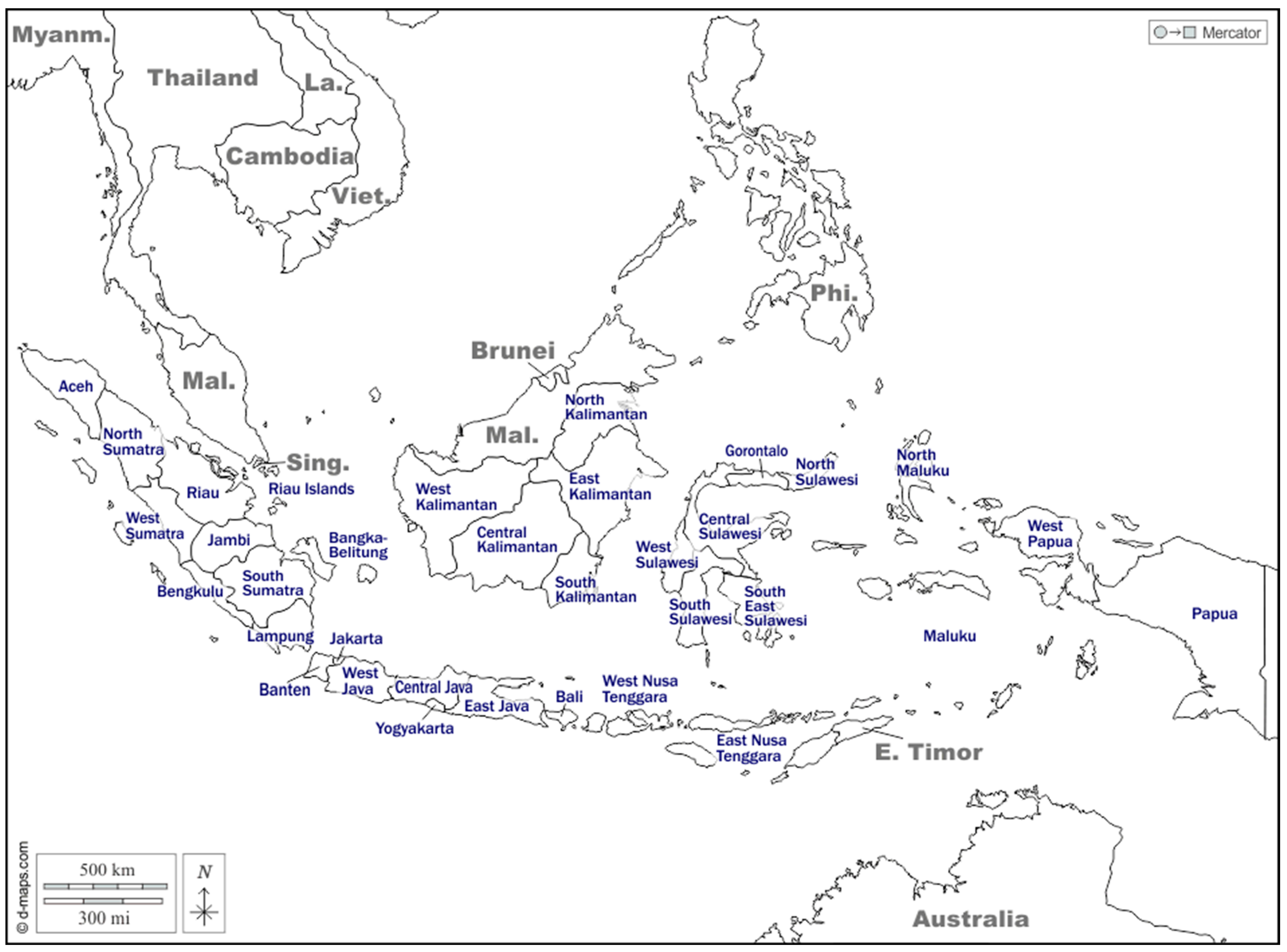

3.1. Participants and Sampling Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.3. Supporting Interreligious Conflicts

3.4. Religious Practices

3.5. Religious Beliefs

3.6. Salience

3.7. Memory of Conflicts

3.8. Perceived Threat

3.9. Individual Characteristics

3.10. Measurement Invariance

3.11. Strategy for Analyses

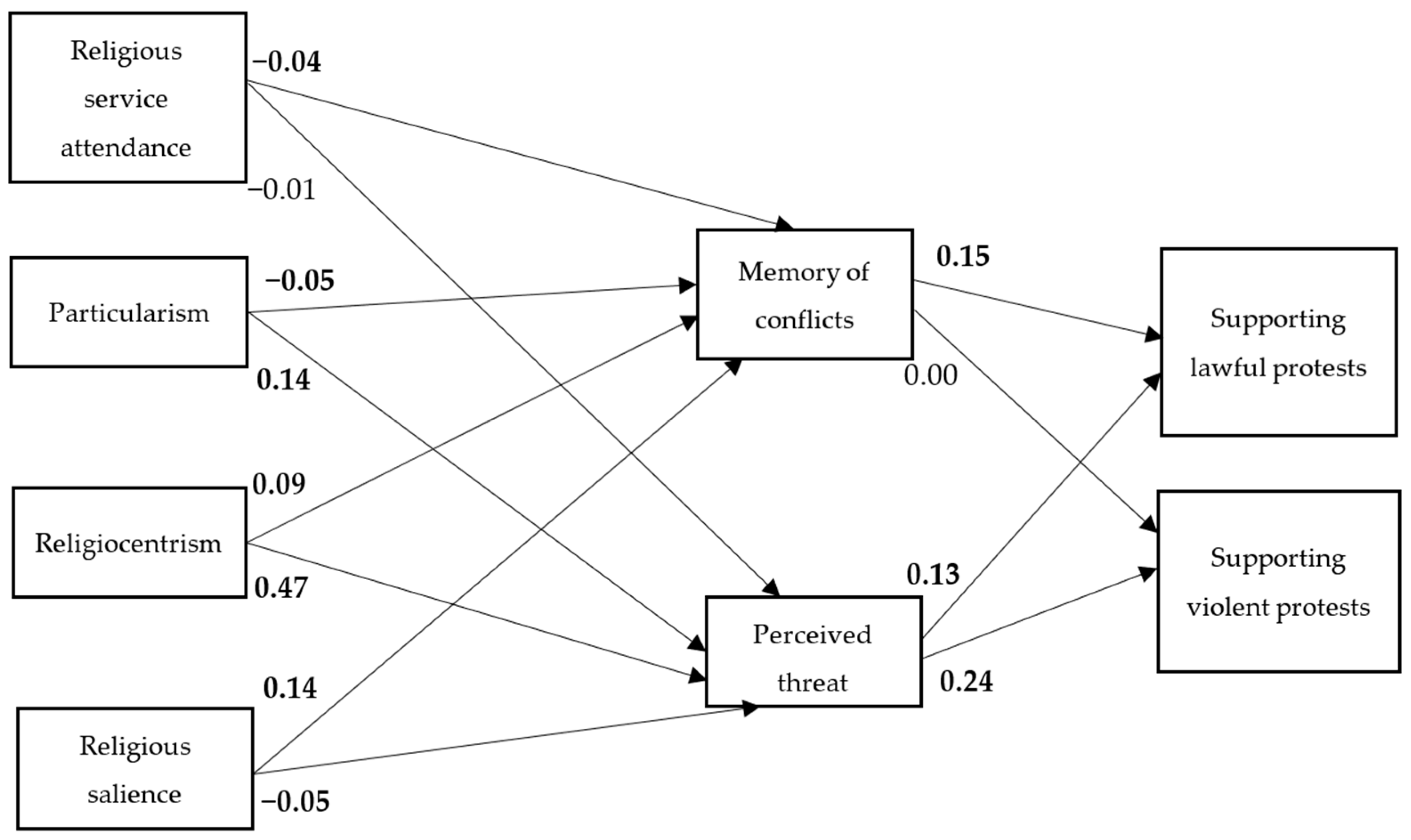

4. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Items | Muslims | Christians | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | F2 | F1 | F2 | |

| 80. …demonstrations that protest against job discrimination in case of my religious group experiences it | 0.71 | 0.72 | ||

| 83. …public criticism of abuse of political power that threatens my religious group | 0.68 | 0.74 | ||

| 84. …public criticism of actions that undermine the political influence of my religious group | 0.60 | 0.67 | ||

| 86. …demonstrations that protest against abuse of political power that threatens my religious group | 0.78 | 0.83 | ||

| 88. …demonstrations that protest against my religious group’s lack of free access to education | 0.85 | 0.87 | ||

| 90. …public criticism of my religious group’s lack of free access to education | 0.71 | 0.75 | ||

| 81. …the damaging of property to enforce the political influence of my religious group | 0.73 | 0.69 | ||

| 82. …harm to persons to obtain more jobs for my religious group | 0.77 | 0.69 | ||

| 85. …the damaging of property to enforce free access to education for my religious group | 0.77 | 0.77 | ||

| 87. …harm to persons to fight abuse of political power against my religious group | 0.79 | 0.86 | ||

| 89. …support harm to persons to enforce the political influence of my religious group | 0.87 | 0.91 | ||

| 91. …harm to persons to enforce free access to education for my religious group | 0.85 | 0.86 | ||

| CR | 0.87 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.91 |

| AVE | 0.53 | 0.64 | 0.59 | 0.64 |

| Number of valid cases | 1452 | 574 | ||

References

- Anthony, Francis-Vincent, Chris A. M. Hermans, and Carl Sterkens. 2015. Religion and Conflict Attribution. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Babbie, Earl R. 1989. The Practice of Social Research, 5th ed. Belmont: Wadsworth Pub. Co. [Google Scholar]

- Badan Pusat Statistik. 2021. Statistik Indonesia; Jakarta: Badan Pusat Statistik.

- Bagozzi, P. Richard, and R. Jeffrey Edwards. 1998. A General Approach for Representing Constructs in Organizational Research. Organizational Research Methods 1: 45–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, Patrick, Kai Kaiser, and Menno Pradhan. 2009. Understanding Variations in Local Conflict: Evidence and Implications from Indonesia. World Development 37: 698–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-tal, Daniel. 1998. Societal Beliefs in Times of Intractable Conflict: The Israeli Case. International Journal of Conflict Management 9: 22–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-tal, Daniel. 2007. Sociopsychological Foundations of Intractable Conflicts. American Behavioral Scientist 50: 1430–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Tal, Daniel, Lily Chernyak-Hai, Noa Schori, and Ayelet Gundar. 2009. A sense of self-perceived collective victimhood in intractable conflicts. International Review of the Red Cross 91: 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beller, Johannes, and Christoph Kröger. 2017. Religiosity, Religious Fundamentalism, and Perceived Threat as Predictors of Muslim Support for Extremist Violence. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 10: 343–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Nun Bloom, Pazit, Gizem Arikan, and Marie Courtemanche. 2015. Religious Social Identity, Religious Belief, and Anti-Immigration Sentiment. American Political Science Review 109: 203–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blalock, Hubert M., Jr. 1967. Status Inconsistency, Social Mobility, Status Integration and Structural Effects. American Sociological Review 32: 790–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumer, Herbert. 1958. Race Prejudice as a Sense of Group Position. The Pacific Sociological Review 1: 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobo, Lawrence D. 1999. Prejudice as Group Position: Microfoundations of a Sociological Approach to Racism and Race Relations. Journal of Social Issues 55: 8–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobo, Lawrence, and Vincent L. Hutchings. 1996. Perceptions of Racial Group Competition: Extending Blumer’ s Theory of Group Position to a Multiracial Social Context. American Sociological Review 61: 951–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, John, and With Leah. 2010. Maluku and North Maluku. In Anomie and Violence: Non-Truth and Reconciliation in Indonesian Peacebuilding. Canberra: ANU Press, pp. 147–242. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, Marilynn B. 1999. The Psychology of Prejudice: Ingroup Love or Outgroup Hate? Journal of Social Issues 55: 429–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, Marilynn B. 2001. Ingroup Identification and Intergroup Conflict. Social Identity, Intergroup Conflict, and Conflict Reduction 3: 17–41. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, James E. 2004. A Three-Factor Model of Social Identity. Self and Identity 3: 239–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Gordon W., and Roger B. Rensvold. 2002. Evaluating Goodness-of-Fit Indexes for Testing Measurement Invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 9: 233–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coser, Lewis A. 1956. The Functions of Social Conflict. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Croucher, Stephen M. 2017. Integrated Threat Theory. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, Ohad, and Daniel Bar-Tal. 2009. A Sociopsychological Conception of Collective Identity: The Case of National Identity as an Example. Personality and Social Psychology Review 13: 354–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, Gordon F., Joseph E. Faulkner, and Rex H. Warland. 1976. Dimensions of Religiosity Reconsidered; Evidence from a Cross-Cultural Study. Social Forces 54: 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Juan, Alexander, Jan H. Pierskalla, and Johannes Vüllers. 2015. The Pacifying Effects of Local Religious Institutions: An Analysis of Communal Violence in Indonesia. Political Research Quarterly 68: 211–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d-maps.com. 2022. Indonesian Map with Provinces. Available online: https://d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=5485&lang=en (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- Duckitt, John. 2003. Prejudice and Intergroup Hostility. In Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 559–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisinga, Rob, Albert Felling, and Jan Peters. 1991. Christian Beliefs and Ethnocentrism in Dutch Society: A Test of Three Models. Review of Religious Research 32: 305–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, Andy. 2009. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginges, Jeremy, Ian Hansen, and Ara Norenzayan. 2009. Religion and Support for Suicide Religion Attacks. Psychological Science 20: 224–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glas, Saskia, Niels Spierings, and Peer Scheepers. 2018. Re-Understanding Religion and Support for Gender Equality in Arab Countries. Gender and Society 32: 686–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadiz, Vedi R. 2017. Indonesia’s Year of Democratic Setbacks: Towards a New Phase of Deepening Illiberalism? Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 53: 261–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halili. 2016. Laporan Kondisi Kebebasan Beragama/Berkeyakinan Di Indonesia 2015. Politik Harapan: Minim Pembuktian. Jakarta: Pustaka Masyarakat Setara. [Google Scholar]

- Herriot, Peter. 2014. Religious Fundamentalism and Social Identity. London: Routledge, pp. 1–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdcroft, Barbara. 2006. What Is Religiosity? Catholic Education: A Journal of Inquiry and Practice 10: 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, Daire, Joseph Coughlan, and Michael R. Mullen. 2008. Structural Equation Modelling: Guidelines for Determining Model Fit. The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 6: 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Li Tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 2009. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6: 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humaedi, M. Alie. 2014. Kegagalan Akulturasi Budaya Dan Isu Agama Dalam Konflik Lampung. Analisa 21: 149–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Rights Watch. 2013. Religion’s Name: Abuses against Religious Minorities in Indonesia. New York: Human Rights Watch. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski, Peter J., Andy J. Johnson, Jillian E. Holtz Damron, and Tegan Smischney. 2011. Religiosity, Intolerant Attitudes, and Domestic Violence Myth Acceptance. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 21: 163–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanas, Agnieszka, Peer Scheepers, and Carl Sterkens. 2015. Interreligious Contact, Perceived Group Threat, and Perceived Discrimination: Predicting Negative Attitudes among Religious Minorities and Majorities in Indonesia. Social Psychology Quarterly 78: 102–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Hae-Young. 2013. Statistical Notes for Clinical Researchers: Assessing Normal Distribution (2) Using Skewness and Kurtosis. Restorative Dentistry & Endodontics 38: 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipgen, Nehginpao. 2013. Conflict in Rakhine State in Myanmar: Rohingya Muslims’ Conundrum. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs 33: 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, Taciano L., and Ronald Fischer. 2010. Testing Measurement Invariance across Groups: Applications in Cross-Cultural Research. International Journal of Psychological Research 3: 111–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulia, Musdah. 2011. The Problem of Implementation of the Rights of Religious. Salam 14: 39–60. [Google Scholar]

- Muluk, Hamdi, Nathanael G. Sumaktoyo, and Dhyah Madya Ruth. 2013. Jihad as Justification: National Survey Evidence of Belief in Violent Jihad as a Mediating Factor for Sacred Violence among Muslims in Indonesia. Asian Journal of Social Psychology 16: 101–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olzak, Susan. 2013. Competition Theory of Ethnic/Racial Conflict and Protest. In The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements. Edited by David A. Snow, Donatella della Porta, Bert Klandermans and Doug McAdam. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamungkas, Cahyo. 2015. Intergroup Contact Avoidance in Indonesia. Nijmegen: Radboud University Nijmegen. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, Thomas F., Oliver Christ, Ulrich Wagner, and Jost Stellmacher. 2007. Direct and Indirect Intergroup Contact Effects on Prejudice: A Normative Interpretation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 31: 411–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. 2015. The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010–2050. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney, Jean S., and Anthony D. Ong. 2007. Conceptualization and Measurement of Ethnic Identity: Current Status and Future Directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology 54: 271–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieterse, H. J. C., Peer. L. H. Scheepers, and Johannes A. Van Der Ven. 1991. Religious Beliefs and Ethnocentrism: A Comparison between the Dutch and White South Africans. Journal of Empirical Theology 4: 64–85. [Google Scholar]

- Putnick, Diane L., and Mark H. Bornstein. 2016. Measurement Invariance Conventions and Reporting: The State of the Art and Future Directions for Psychological Research. Developmental Review 41: 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quillian, Lincoln. 1995. Prejudice as a Response to Perceived Group Threat: Population Composition and Anti- Immigrant and Racial Prejudice in Europe. American Sociological Review 60: 586–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roof, Wade Clark, and Richard B. Perkins. 1975. On Conceptualizing Salience in Religious Commitment. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 14: 111–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Yves. 2018. The Lavaan Tutorial. Ghent: Department of Data Analysis Ghent University. Available online: http://lavaan.ugent.be/tutorial/tutorial.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2022).

- Savelkoul, Michael, Maurice Gesthuizen, and Peer Scheepers. 2014. The Impact of Ethnic Diversity on Participation in European Voluntary Organizations: Direct and Indirect Pathways. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 43: 1070–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheepers, Peer, and Rob Eisinga. 2015. Religiosity and Prejudice against Minorities. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier, vol. 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheepers, Peer, Mèrove Gijsberts, and Evelyn Hello. 2002a. Religiosity and Prejudice against Ethnic Minorities in Europe: Cross-National Tests on a Controversial Relationship. Review of Religious Research 43: 242–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheepers, Peer, Mérove Gijsberts, and Marcel Coenders. 2002b. Ethnic Exclusionism in European Countries: Public Opposition to Civil Rights for Legal Migrants as a Response to Perceived Ethnic Threat. European Sociological Review 18: 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlueter, Elmar, and Peer Scheepers. 2010. The Relationship between Outgroup Size and Anti-Outgroup Attitudes: A Theoretical Synthesis and Empirical Test of Group Threat- and Intergroup Contact Theory. Social Science Research 39: 285–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, Tery, Abritaningrum Tsalatsa Yam’ah, de Jong Edwin, Scheepers Peer, and Sterkens Carl. 2018. Interreligious Conflicts in Indonesia 2017: A Cross-Cultural Dataset in Six Conflict Regions in Indonesia (DANS Data). Amsterdam: Pallas Publication, Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, Tery, Edwin B. P. De Jong, Peer L. H. Scheepers, and Carl J. A. Sterkens. 2020. The relation between religiosity dimensions and support for interreligious conflict in Indonesia. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 42: 244–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, Rodney, and Charles Y. Glock. 1968. American Piety: The Nature of Religious Commitment Vol. 1. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan, Walter G., Rolando Diaz-Loving, and Anne Duran. 2000. Integrated Threat Theory and Intercultural Attitudes: Mexico and the United States. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 31: 240–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterkens, Carl, and Francis-Vincent Anthony. 2008. A Comparative Study of Religiocentrism among Christian, Muslim and Hindu Students in Tamil Nadu, India. Journal of Empirical Theology 21: 32–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryker, Sheldon, and Richard T. Serpe. 1994. Identity Salience and Psychological Centrality: Equivalent, Overlapping, or Complementary Concepts? Social Pyschology Quarterly 57: 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subagya, Y. Tri. 2015. Support for Ethno-Religious Violence in Indonesia. Nijmegen: Radboud University. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, Henri. 1974. Social Identity and Intergroup Behaviour. Information (International Social Science Council) 13: 65–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, Henri, and John Turner. 1979. An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Edited by William G. Austin and Stephen Worchel. Monterey: Brooks/Cole, pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, Henri. 1981. Human Groups and Social Categories. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, Tania, Miles Hewstone, Jared Kenworthy, and Ed Cairns. 2009. Intergroup Trust in Northern Ireland. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 35: 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, John C. 1975. Social Comparison and Social Identity: Some Prospects for Intergroup Behavior. European Journal of Social Psychology 5: 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Department of State. 2017. Indonesia 2017 International Religous Freedom Report. United States Department of State. Available online: https://www.state.gov/reports/2017-report-on-international-religious-freedom/ (accessed on 2 January 2022).

- van Bruinessen, Martin. 2018. Indonesian Muslims in a Globalising World. Singapore: S. Rajaratman School of International Studies, p. 311. [Google Scholar]

- Wibisono, Susilo, Winnifred Louis, and Jolanda Jetten. 2019. The Role of Religious Fundamentalism in the Intersection of National and Religious Identities. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology 13: e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohl, Michael J. A., and Nyla R. Branscombe. 2008. Remembering Historical Victimization: Collective Guilt for Current Ingroup Transgressions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 94: 988–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, Joshua D. 2016. More Religion, Less Justification for Violence. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 38: 159–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Joshua D., and Jason R. Young. 2017. Implications of Religious Identity Salience, Religious Involvement, and Religious Commitment on Aggression. Identity 17: 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Myeongsun M., and Mark H. C. Lai. 2018. Testing Factorial Invariance with Unbalanced Samples. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 25: 201–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ysseldyk, Renate, Kimberly Matheson, and Hymie Anisman. 2010. Religiosity as Identity: Toward an Understanding of Religion from a Social Identity Perspective. Personality and Social Psychology Review 14: 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zárate, Michael A., Berenice Garcia, Azenett A. Garza, and Robert T. Hitlan. 2004. Cultural Threat and Perceived Realistic Group Conflict as Dual Predictors of Prejudice. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 40: 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Range | Muslims | Christians | t-Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Lawful protests | 1–5 | 3.40 | 0.86 | 2.98 | 0.94 | −9.17 |

| Violent protests | 1–5 | 2.28 | 0.84 | 1.86 | 0.64 | −12.20 |

| Religious service attendance | 1–7 | 3.58 | 1.63 | 4.02 | 1.01 | 7.29 |

| Particularism | 1–5 | 3.99 | 0.72 | 3.26 | 1.05 | −15.34 |

| Religiocentrism | 1–5 | 3.18 | 0.66 | 2.76 | 0.75 | −11.63 |

| Salience | 1–5 | 4.01 | 0.85 | 4.20 | 0.83 | 4.51 |

| Memory of conflicts | 1–5 | 1.46 | 0.78 | 1.67 | 0.91 | 5.01 |

| Perceived threat | 1–5 | 2.72 | 0.95 | 2.19 | 0.74 | −13.48 |

| Individual characteristics | ||||||

| Age | 17–65 | 33.07 | 12.22 | 31.03 | 11.49 | −3.53 |

| Sex | 0/1 | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.50 | - |

| Education | 1–6 | 3.47 | 1.08 | 3.95 | 0.97 | 9.78 |

| Income | 1–8 | 3.50 | 2.04 | 4.11 | 1.96 | 6.20 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Lawful protests | - | 0.32 | −0.06 | 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.22 |

| 2. Violent protests | −0.03 | 0.14 | 0.28 | −0.10 | −0.02 | 0.35 | ||

| 3. Religious service attendance | −0.04 | −0.02 | 0.11 | −0.05 | −0.03 | |||

| 4. Particularism | 0.50 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.30 | ||||

| 5. Religiocentrism | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.42 | |||||

| 6. Salience | 0.13 | 0.00 | ||||||

| 7. Memory of conflicts | −0.01 | |||||||

| 8. Perceived threat | - | |||||||

| AVE | 0.55 | 0.65 | - | 0.58 | 0.34 | 0.64 | - | 0.62 |

| Scale | Differences | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | df | p | ΔCFI | Conclusion | |

| 1. Supporting interreligious conflicts | 36.90 | 10 | 0.000 | −0.002 | Invariant |

| 2. Religious beliefs | 13.12 | 6 | 0.041 | −0.002 | Invariant |

| 3. Religious salience | 4.18 | 1 | 0.041 | −0.001 | Invariant |

| 4. Perceived threat | 0.47 | 3 | 0.925 | −0.001 | Invariant |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Setiawan, T.; Tjandraningtyas, J.M.; Kuntari, C.M.I.S.; Rahmani, K.; Maria, C.; Indrianie, E.; Puspitasari, I.; Dwijayanthy, M. Memory of Conflicts and Perceived Threat as Relevant Mediators of Interreligious Conflicts. Religions 2022, 13, 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13030250

Setiawan T, Tjandraningtyas JM, Kuntari CMIS, Rahmani K, Maria C, Indrianie E, Puspitasari I, Dwijayanthy M. Memory of Conflicts and Perceived Threat as Relevant Mediators of Interreligious Conflicts. Religions. 2022; 13(3):250. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13030250

Chicago/Turabian StyleSetiawan, Tery, Jacqueline Mariae Tjandraningtyas, Christina Maria Indah Soca Kuntari, Kristin Rahmani, Cindy Maria, Efnie Indrianie, Indah Puspitasari, and Meta Dwijayanthy. 2022. "Memory of Conflicts and Perceived Threat as Relevant Mediators of Interreligious Conflicts" Religions 13, no. 3: 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13030250

APA StyleSetiawan, T., Tjandraningtyas, J. M., Kuntari, C. M. I. S., Rahmani, K., Maria, C., Indrianie, E., Puspitasari, I., & Dwijayanthy, M. (2022). Memory of Conflicts and Perceived Threat as Relevant Mediators of Interreligious Conflicts. Religions, 13(3), 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13030250