Crisis, Liturgy, and Communal Identity: The Celebration of the Hispano-Mozarabic Rite in Toledo, Spain as a Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Crisis Points in the History of the Hispano-Mozarabic Rite

2.1. The Need to Forge a Single “Visigothic” Rite

2.2. The Arab Invasions

2.3. The Attempted Suppression of the Hispano-Mozarabic Rite and the Reconquista

2.4. The Reforms of Cardinal Cisneros and Their Legacy

Cisneros’s patronage had far broader implications than the survival of the rite in Toledo. Over the course of the early modern period, the memory of the medieval rite was gradually transformed, through revision, publication, practice, and historical discourse, from the local observance of a medieval community into an early modern symbol of the Spanish nation…In this way the celebration of the neo-Mozarabic rite fostered an imagined community in which the Mozarabs represented the preeminence of Christianity in Iberia.30

[b]y establishing his cathedral as the effective center of the Mozarabic rite, Cisneros effectively reversed the exclusion of the rite from Toledo’s principal church that had occurred so many centuries earlier with the introduction of the Roman rite in 1086. Over the course of the sixteenth century, however, the Mozarabs’ standing changed, as the requirement of purity of blood (limpieza de sangre) and increasing suspicion of converts brought the ancestry of Spanish Christians under closer scrutiny. In the context of heightened anxiety about religious identity, the Mozarabs of Toledo were perceived as tainted by assimilation of Arab customs that had given the community its common name.

Ironically, then, even as contemporary Toledean Mozarabs were resented for their tax exemptions and viewed as potentially suspect because of their earlier cohabitation with Muslims, the Mozarabic liturgy…was extolled as an authentic relic of the earliest peninsular Christianity…By the eighteenth century the Mozarabic liturgy was hardly practiced at all but seems to have been considered something of a national treasure.

Cisneros had created an enduring myth of ritual coherence and antiquity by reaffirming Toledan Mozarabic identity through a reinvention of a medieval liturgy. By the eighteenth century the neo-Mozarabic rite had acquired a symbolic association with the Spanish nation; commentaries on the rite published in this period refer to the luminaries who had attended mass in Toledo’s Mozarabic Chapel.

3. Modern Celebration: An Ethnographic Perspective

3.1. Shut Doors and the Prioritization of the Roman Rite

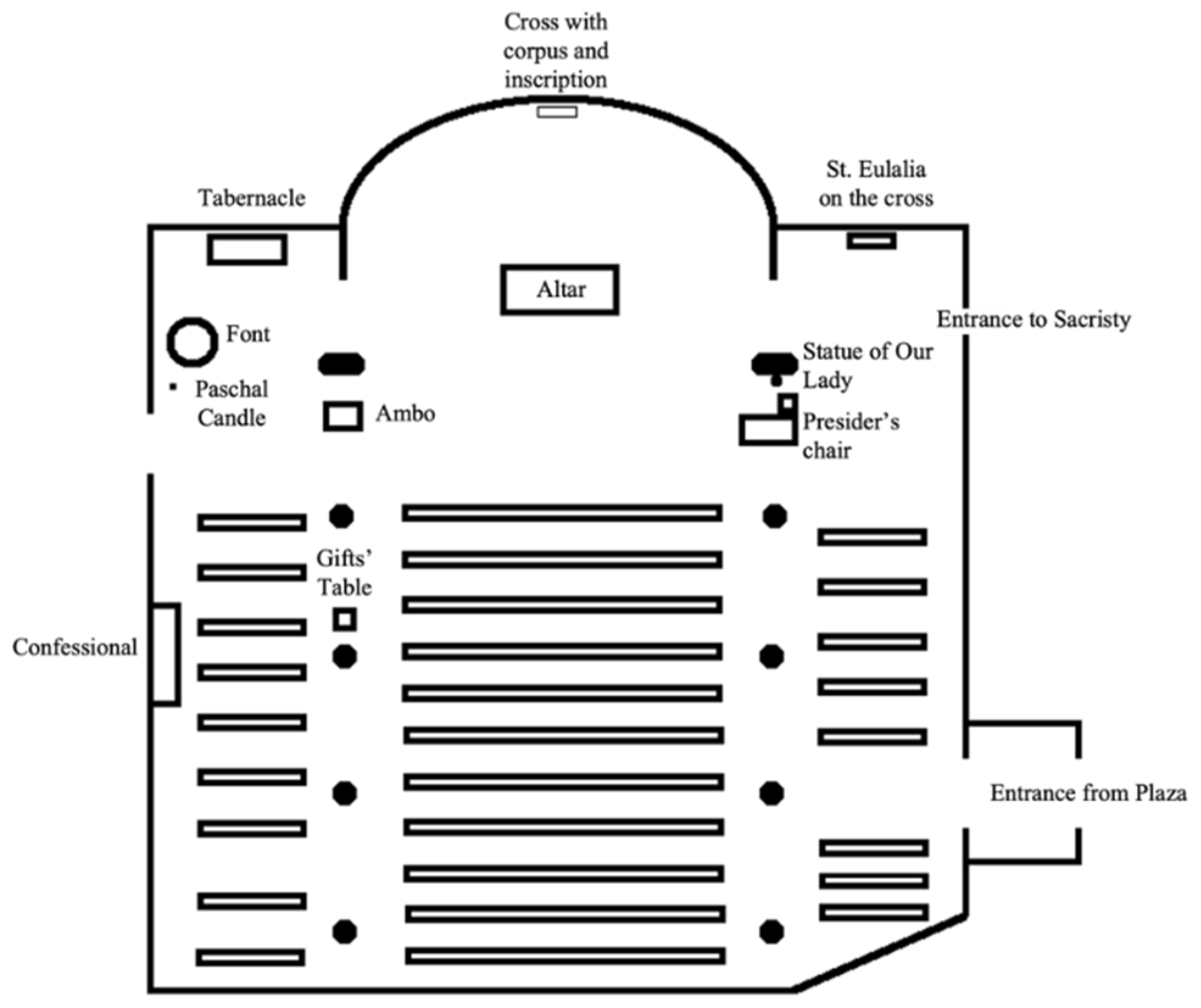

3.2. The Mozarabic Chapel in the Cathedral of Toledo

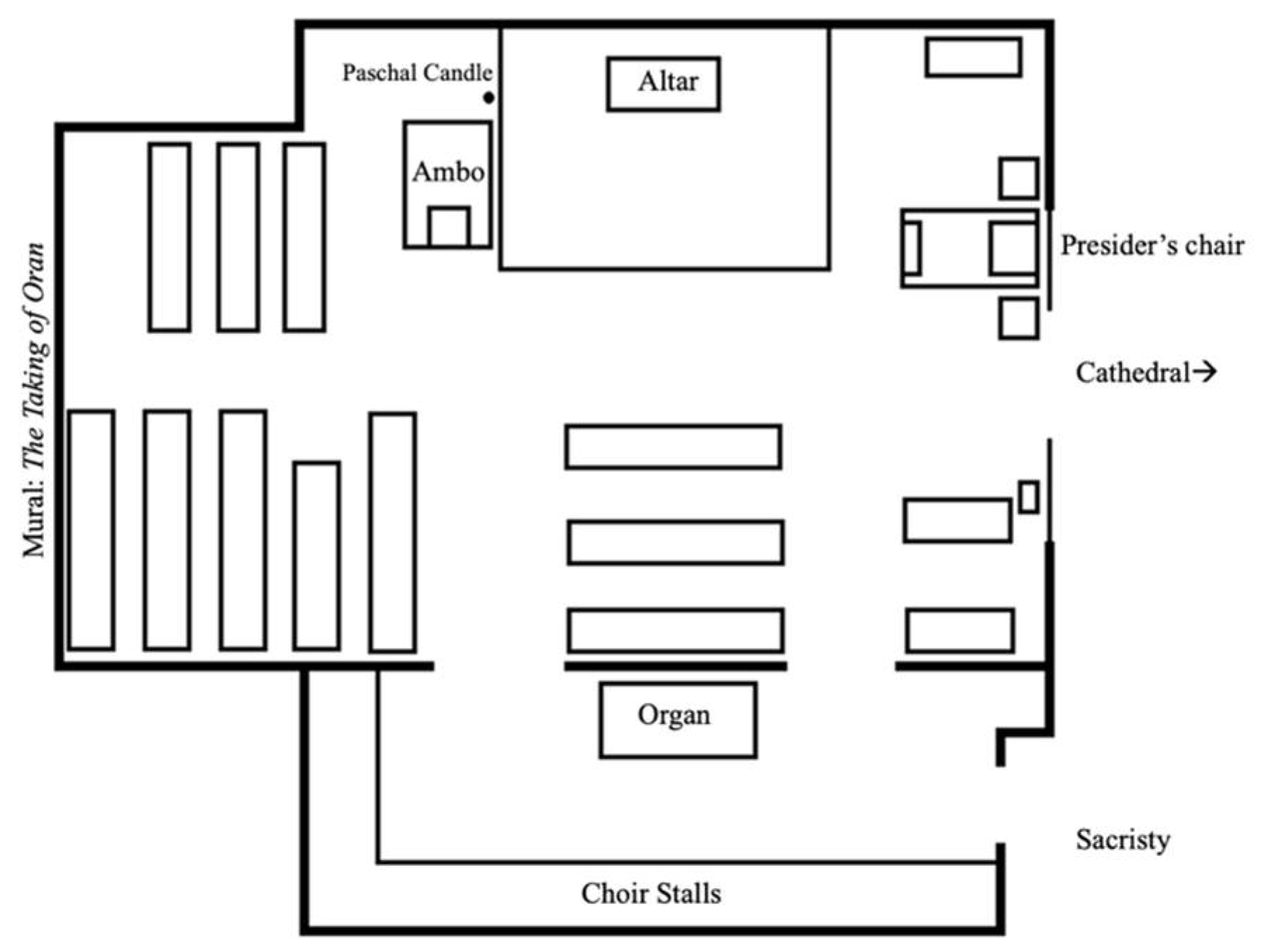

3.3. Parish Church of Santa Eulalia y San Marcos

4. Analysis of the Modern Celebration

4.1. The Hispano-Mozarabic Rite Remains Central to the Mozarab Community’s Identity

4.2. The Different Functions of the Cathedral and Parish Celebrations: Political vs. Mozarab

Irish speakers may be a minority, but the fact that many of the indicators of a socio-political ‘centre’ confirm Irish-speaking as normative suggests that they are not ‘marginal’: the constitution of the nation is written in Irish (with an English translation), road signs are all in Irish (with an English translation), Irish is a non-negotiable required subject in school: every English-speaking Irish child has to learn how to speak, read and write it. However, native Irish speakers have been shown to be ‘not-central’ in a host of ways that those grand gestures may serve to mask.

[A]ll should hold in the greatest esteem the liturgical life of the diocese centered around the bishop, especially in his cathedral church. They must be convinced that the principal manifestation of the church consists in the full, active participation of all God’s holy people in the same liturgical celebrations, especially in the same Eucharist, in one prayer, at one altar, at which the bishop presides, surrounded by his college of priests and by his ministers.

4.3. The Hispano-Mozarabic Rite, the Roman Rite, and the Broader Catholic Church

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The term “Rite” should be distinguished from the term “rite.” The Church’s liturgies are made up of a number of “rites”: the sacraments, the funeral rites, rites of blessing, etc. The various ways in which these rites are celebrated form distinct liturgical traditions known as “Rites.” A “Rite” is a coherent and autonomous form of the Christian ritual system in which various “rites” are celebrated. For more, see (Chase 2021, pp. 28–30). With regard to the Hispano-Mozarabic Rite, the Rite has been given a number of names. Scholars studying the Visigothic or pre-Visigothic eras tend to prefer “Old Spanish” or “Old Hispanic.” Those studying the Rite from the 8th century onwards often call it the “Mozarabic,” and the current liturgical books use the term “Hispano-Mozarabic.” In the interests of rooting this liturgical tradition in a living tradition, I will use the term “Hispano-Mozarabic” precisely because this name spans both the Visigothic and Mozarabic periods, while at the same time pointing to the modern community who claims this tradition as their own. The Hispano-Mozarabic Rite is one of the last few ancient Western liturgical Rites in communion with the Catholic Church still preserved today. Before the Council of Trent in the 16th century, there were a number of regional liturgical traditions. However, after the council, almost every local church was required to adopt the Roman Rite. In only a few instances were older local liturgical traditions preserved. For more, see (Chase 2018). |

| 2 | Boynton notes that “the idea of the reconquista has been revised by historians of the Iberian peninsula, who distance themselves from uses of the term that cast what were in fact diverse and sporadic endeavors as a single, coherent movement lasting for centuries.” (Boynton 2015). My use of the term reconquista is not meant to denote a single coherent movement but rather the process of constructing a myth of reconquest from the 9th century onwards. For more, see (O’Callaghan 2013). |

| 3 | The Mozarab community is the successor to the community of Christians who lived in Spain during the Muslim rule of the southern part of the Iberian Peninsula. For more background on this community and the name, see (Gómez-Ruiz 2007, chp. 1). |

| 4 | For a quick summary of this, see (Gómez-Ruiz 2007, pp. 2, 26–33). See also Section 2.3. |

| 5 | Translation from (Gómez-Ruiz 2007, p. 8). Original in (Muñoz Perea 2005, p. 9). |

| 6 | For more information on the importance of the Ilustre Hermandad de Caballeros y Damas mozárabes and the way that it influences and determines Mozarab membership and meaning, see (Gómez-Ruiz 2007, pp. 3–7). It also has a role in the new Congregation for the Hispano-Mozarabic Rite, see (Sierra López 2020). See also the Hermandad’s website: http://www.mozarabesdetoledo.es/ (accessed on 21 Feburary 2022). |

| 7 | See note 34. |

| 8 | This is an ecclesial question about the various ecclesiologies at work in the Church. To use the helpful categories of Avery Dulles, this highlights the tension between “the Church as Institution” and “the Church as mystical communion,” see (Dulles 2002). Elsewhere, I have also tried to talk about “ecclesial succession” in concert with “episcopal succession,” see (Chase 2018). |

| 9 | For standard works, see (Searle 1992; Mitchell 1999, 2009; Grimes 2010). See also the recent work by (Marx 2013; Barnard et al. 2014; Ross 2014; Seah 2021; Johnson 2021). |

| 10 | The prolonged marginalization of the Western Non-Roman Rites—and even Eastern Rites—vis à vis the Roman Rite is a hallmark of liturgical history in the West, see (Chase 2021). |

| 11 | Here, I am following the work of (Phelan 2014). |

| 12 | For scholarship on this period, see (García Moreno 1989, pp. 317–24, Part 4; Orlandis 1976, 1977, chp. 9; 1984, chp. 2; 1992, pp. 57–59, 117–24; Stocking 2000; Collins 1995, chps. 2–4; 2006, chps. 2 and 3; Koon and Wood 2009, pp. 793–808; Wood 2006, pp. 3–17; 2012). |

| 13 | Visigothic Spain was not the only place where baptism was used to bolster communal identity and kingdom-wide cohesion. Owen Phelan has shown the central role that baptism also played in the formation of the Carolingian Empire, see (Phelan 2014, pp. 49, 262). |

| 14 | Regional variations did still exist, see (Chase 2021, pp. 39, 47–51). |

| 15 | |

| 16 | For a recent and helpful summary, see (Maloy 2020, pp. 15–18, 220–26). |

| 17 | See (Gonzálvez 1985, p. 165). See also (Maloy 2020, pp. 14–18). For a look at other factors besides the liturgy constructing Mozarab identity in this period, see (Hitchcock 2016). |

| 18 | See (Pinell I Pons 1997, p. 190). For a helpful and recent summary, see (Maloy 2020, pp. 17–18, 189–92). |

| 19 | For a helpful overview of the sources, see (Walker 1998, pp. 30–34). |

| 20 | For more on this debate, see (Cavadini 1993; King 1957, pp. 467–68, 494–98; Gómez-Ruiz 2007, pp. 30–33, 125–38.) |

| 21 | “De Romano autem officio, quod tua iussione accepimus, sciatis nostrum terram admodum desolata esse” (Gambra 1997, vol. II, p. 93). |

| 22 | Slight variations on this story exist, with some stories recounting that the Roman book was the one that leapt from the flames, while the Hispano-Mozarabic book remained in the fire unharmed, see (Bosch 2010, p. 57). |

| 23 | For more on the historiography, see (Rubio Sadia 2006; Deswarte 2007, pp. 533–44). |

| 24 | This also seems confirmed by the manuscript evidence, see (Maloy 2020, pp. 220–26). |

| 25 | |

| 26 | While it has historically been thought that Alfonso VI’s fuero informally allowed for the continuance of the Hispano-Mozarabic Rite “by informal agreement in the six Mozarabic parishes later named by Rodrigo Jiménez de Rada (archbishop of Toledo from 1210 to 1249),” some scholars have recently argued “that the six Mozarabic parishes named by Jiménez de Rada are unlikely to have existed before 1085, proposing instead that they were built to accommodate an influx of Andalusi immigrants fleeing the Almohads in the 1140s” (Maloy 2020, p. 221). This may be borne out by the manuscript evidence; see (Maloy 2020, pp. 220–23, 225). Maloy does note, however, that some evidence may suggest that the Rite was still practiced in Toledo and/or its environs before the 1140s, see (Hornby and Maloy 2013, pp. 304–5; Maloy 2020, p. 225). |

| 27 | For more, see (Hornby and Maloy 2013, p. 304). Possible reasons why the fuero does not directly take up the Rite are given by Gonzálvez, see (Gonzálvez 1985, pp. 174–75). |

| 28 | See (Ruiz 2004; Bosch 2010, pp. 60–64; Boynton 2011, 2015, p. 49). For more on the Mozarab community in this period, see (Dávila y García-Miranda 2003, pp. 95–120). |

| 29 | See (Ruiz 2004; Boynton 2015). The Hispano-Mozarabic Rite even made it to Mexico, where “the archbishop of Mexico (and future archbishop of Toledo) Francisco Antonio Lorenzana (1772–1804), published an edition of the Mozarabic Mass for Saint James (Santiago) in Puebla” (Boynton 2015, p. 7). The missal is discussed above, see (Lorenzana 1770). |

| 30 | See (Boynton 2015, pp. 6–7). Outside of a liturgical context, see (Hillgarth 2009). |

| 31 | Boynton provides a helpful summary, see (Boynton 2011, 2015). For a more detailed treatment, see (Bosch 2010, pp. 60–64). See also (Gómez-Ruiz 2007, chp. 3). |

| 32 | See (Boynton 2011). This is in keeping with J. N. Hillgarth’s study, see (Hillgarth 2009). See also (Ferrer Gresneche 2018, pp. 235–54). |

| 33 | For a history of the modern reform of the Rite, see (Chase 2021, pp. 47–50). |

| 34 | The publication of the new Missale Hispano-Mozarabicum, extended the celebration of the Rite throughout Spain, cf. Decree of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments No. 763/92 of 23 January 1994; Praenotandos of the Missale Hispano-Mozarabicum, nos. 159–160. For more on the recently established “Congregation for the Hispano-Mozarabic Rite,” see (Sierra López 2020). For more on the celebration of this Rite outside of Toledo, see (Fernández Serrano 1978; Sánchez Montealegre 1988, p. 3). In more recent history, and in regard to Madrid, see (Rouco Varela 2001; Ferrer Gresneche 2018). More information at http://www.mozarabia.es/ (accessed on 13 August 2021). I also know that the liturgy has been celebrated frequently for centuries in Salamanca. On a recent trip of mine to Spain in 2019, a woman at the diocesan bookstore in Granada enthusiastically told me that the Hispano-Mozarabic Rite is sometimes still celebrated there too. |

| 35 | The parishes in Toledo are: Parroquia Mozárabe de las Santas Justa y Rufina and La Iglesia Mozárabe de San Lucas http://www.santasjustayrufina.org (accessed on 21 Feburary 2022), as well as the Parroquia Mozárabe de Santa Eulalia https://www.facebook.com/Parroquia-Moz%C3%A1rabe-de-Santa-Eulalia-Toledo-1415030855486603/ (accessed on 21 Feburary 2022). |

| 36 | For a helpful introduction to the performative and ritual reality of the liturgy, see (Bradshaw and Melloh 2007). |

| 37 | In my first trip to Toledo on Sunday 23 November 2014 and Monday 24 November 2014 (last week of Tiempo de Cotidiano), I was only able to experience the Hispano-Mozarabic Rite at the Mozarabic Chapel. In my second trip on 16 and 23 October 2016 (XXVI and XXVII Domingos de Cotidiano), I decided to visit both the Mozarabic Chapel and the Mozarabic parish of Santa Eulalia y San Marcos. On my third trip on 11 June 2017 (IX Domingo de Cotidiano), I attended mass at the Mozarabic parish of Santas Justa y Rufina, and I tried to attend the liturgy at the Mozarabic church of San Lucas. Finally, on my last trip on 13 August 2017 (XVI Domingo de Cotidiano), I went to mass at the Mozarabic Chapel and the Mozarabic parish of Santa Eulalia y San Marcos. I also tried to attend mass at the parish church of Santas Justa y Rufina, because the schedule of masses posted at the cathedral seemed to imply that there would be mass that day, but mass was not offered. |

| 38 | For more on this church and a longer description of it, see (Gómez-Ruiz 2007, pp. 81–84). |

| 39 | The book is titled “Rito Hispano-Mozárabe: Libro dl Coro”. |

| 40 | I am not sure exactly what chant was used for the Antiphonam ad Pacem because I do not have access to the community’s newly published Latin/Spanish missalette (2015)—“Rito Hispano-Mozárabe: Libro dl Coro.” But upon returning from my trip, I looked through the worship booklet for the 900-year anniversary celebration of reconquest of Toledo, which includes a number of chants, see (Cabrera and Silveira 1985). See the chant on p. 40. I am not sure if this was the same chant, but it did seem similar. |

| 41 | This was also my experience at the Mozarabic Chapel and at Santas Justa y Rufina. |

| 42 | Gómez-Ruiz’s whole study is about this, but see in particular (Gómez-Ruiz 2007, pp. 3–4, 7–9). |

| 43 | See notes 47 and 48 below. |

| 44 | For the importance of the assembly in the post-Vatican II reforms, see (Janowiak 2011). |

| 45 | |

| 46 | Gómez-Ruiz highlights this throughout his study. |

| 47 | Translation from (Gómez-Ruiz 2007, p. 33). |

| 48 | Constituciones de la Ilustre y Antiquísima Hermandad de Caballeros y Damas Mozárabes de Nuestra Señora de la Esperanza de la Imperial Ciudad de Toledo (Toledo 2009), http://www.mozarabesdetoledo.es/cmt_constituciones.htm (accessed on 23 February 2022). |

| 49 | These acclamations are especially pronounced in the Eucharistic prayer, where the faithful say “Amen” after the words over the bread, and then again after the words over the cup. |

| 50 | Discussions in liturgical studies on center and periphery have been shaped by the work of Stefano Parenti, Robert Taft, and Gabriele Winkler (Parenti 1991, 1997, 2010; 2014, pp. 289–304; 2020; Taft 2001, pp. 214–16; Winkler 1982). Parenti has argued that the center and periphery cannot be so easily identified with either innovation or preservation. |

| 51 | Here, Galadza is building on the work of others, but especially Stefano Parenti; see (Parenti 1991, 1997, 2010, 2014, 2020). |

| 52 | For a very helpful summary, see (Galadza 2018, pp. 2–3, 75). |

| 53 | The archbishop of Toledo also frequently presides at the liturgies of the Hermandad; see (Ferrer Gresneche 2018). The Mozarabs also participate in the Lignum Crucis on Good Friday with the rest of the church in Toledo; see (Gómez-Ruiz 2007, chp. 7). |

| 54 | Gómez-Ruiz also points to this in his study; see (Gómez-Ruiz 2007, p. 122). |

References

- Barnard, Marcel, Johan Cilliers, and Cas Wepener. 2014. Worship in the Network Culture: Liturgical Ritual Studies. Fields and Methods, Concepts and Metaphors. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Belcher, Kimberly. 2010. Ritual Identity and Cultural Transitions in the Syro-Malabar Rite Catholic Church in Chicago. In Ritual Dynamics and the Science of Ritual. Edited by Axel Michaels. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Belcher, Kimberly. 2015. Overflowing the Mar Thoma Cathedral: Ritual Dynamics and Syro-Malabar Identity. Ecclesia Orans 32: 167–87. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Catherine. 1990. The Ritual Body and the Dynamics of Ritual Power. Journal of Ritual Studies 4: 299–313. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Catherine. 2009. Ritual: Perspectives and Dimensions. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, Lynette. 2010. Art, Liturgy, and Legend in Renaissance Toledo: The Mendoza and the Iglesia Primada. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bouley, Allan. 1981. From Freedom to Formula: The Evolution of the Eucharistic Prayer from Oral Improvisation to Written Texts. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boynton, Susan. 2011. Silent Music: Medieval Song and the Construction of History in Eighteenth-Century Spain. Currents in Latin American and Iberian Music. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boynton, Susan. 2015. Restoration or Invention? Archbishop Cisneros and the Mozarabic Rite in Toledo. Yale Journal of Music & Religion 1: 5–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, Paul. 2002. The Search for the Origins of Christian Worship: Sources and Methods for the Study of Early Liturgy. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, Paul F., and John Melloh, eds. 2007. Foundations in Ritual Studies: A Reader for Students of Christian Worship. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, Antonio, and Delgado Silveira, eds. 1985. Novus Ordo Ritus Hispano-Mozarabici: Misa Celebrada Solemnemente en la Clausura del II Congreso Internacional de Estudios Mozárabes, con Motivo del IX Centenario de la Reconquista de Toledo, el 26 de Mayo de 1985. Toledo: Instituto de Estudios Visigótico Mozárabes. [Google Scholar]

- Cavadini, John C. 1993. The Last Christology of the West: Adoptionism in Spain and Gaul, 785–820. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chase, Nathan. 2018. A Chrismatic Framework for Understanding the Intersection of Baptism and Ministry in the Roman Catholic and Eastern Churches. Journal of Ecumenical Studies 53: 12–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, Nathan. 2020a. From Arianism to Orthodoxy: The Role of the Rites of Initiation in Uniting the Visigothic Kingdom. Hispania Sacra 72: 427–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, Nathan. 2020b. The Homiliae Toletanae and the Theology of Lent and Easter. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Chase, Nathan. 2021. A Frayed Tapestry: The Future of the Western Non-Roman Rites. Questions Liturgiques/Studies in Liturgy 101: 27–74. [Google Scholar]

- Collado, Angel Fernández, ed. 2009. Cathedral of Toledo: Chapterhouse and Mozarabic Chapel. Toledo: Cabildo Catedral Primada. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Roger. 1995. Early Medieval Spain: Unity in Diversity, 400–1000, 2nd ed. New Studies in Medieval History. New York: St. Martin’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Roger. 2000. The Arab Conquest of Spain: 710–797. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Roger. 2002. Continuity and Loss in Medieval Spanish Culture: The Evidence of MS Silos, Archivo Monástico 4. In Medieval Spain: Culture, Conflict, and Coexistence, Studies in Honour of Angus Mackay. Edited by Roger Collins and Anthony Goodman. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Roger. 2006. Visigothic Spain, 409–711. A History of Spain. Edited by John Lynch. Malden: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Conferencia Episcopal Espanola. 1991a. Missale Hispano-Mozarabicum. Toledo: Arzobispado de Toledo, vols. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Conferencia Episcopal Espanola. 1991b. Liber Commicus. Toledo: Conferencia Episcopal Espanõla Arzobispado, vols. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Dávila y García-Miranda, José Antonio. 2003. Desarrollo de la comunidad mozárabe de Toledo, desde la concesión de Alfonso VI, hasta nuestros días. In Conmemoración del IX Centenario del Fuero de los Mozárabes. Toledo: Comunidad Mozárabe de Toledo, Instituto de Estudios Visigótico-Mozárabes, Diputación Provincial de Toledo, pp. 95–120. [Google Scholar]

- Deswarte, Thomas. 2007. Justifier l’injustifiable? La Suppression Du Rit Hispanique Dans La Littérature (XIIe-Milieu XIIIe Siècles). In Convaincre et Persuader: Communication et Propaganda Aux XIIe et XIIIe Siècles. Edited by Martin Aurell. Poitiers: Université de Poitiers, Centre d’études Supérieures de Civilisation Médiévale, pp. 533–44. [Google Scholar]

- Dolphin, Erika. 2008. Archbishop Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros and the Decoration of the Chapter Room and Mozarabic Chapel in Toledo Cathedral. Ph.D. dissertation, New York University, Institute of Fine Arts, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Dulles, Avery. 2002. Models of the Church. Garden City: Image Books. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Serrano, Franciso. 1978. Documentos del Rito Mozarabe en el Entorno del Concilio Vaticano II. In Liturgia y Música Mozárabes: Ponencias y Comunicaciones Presentadas Al I Congreso Internacional de Estudios Mozárabes, Toledo, 1975. Toledo: Instituto de Estudios Visigótico-Mozárabes de San Eugenio, pp. 225–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer Gresneche, Juan Miguel. 2018. La liturgia Hispano-Mozárabe en Toledo. In Nasara, Extranjeros en Su Tierra: Estudios Sobre Cultura Mozárabe y Catálogo de la Exposición. Edited by Eduardo Cerrato and Diego Asensio. Córdoba: Cabildo Catedral de Córdoba, pp. 235–54. [Google Scholar]

- Flannery, Austin, ed. 1996. Vatican Council II: Constitutions, Decrees, Declarations, the Basic Sixteen Documents. Northport: Costello Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Gaillardetz, Richard R. 2008. Ecclesiology for a Global Church: A People Called and Sent. Maryknoll: Orbis Books. [Google Scholar]

- Galadza, Daniel. 2018. Liturgy and Byzantinization in Jerusalem. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gambra, Andrés. 1997. Alfonso VI: Cancillería, Curia e Imperio. León: Centro de Estudios e Investigación “San Isidoro”, Caja de España de Inversiones, Caja de Ahorros y Monte de Piedad. [Google Scholar]

- García Moreno, Luis A. 1989. Historia de España Visigoda. Madrid: Cátedra. [Google Scholar]

- Garrigan, Siobhán. 2017. Beyond Ritual: Sacramental Theology after Habermas. Aldershot: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Ruiz, Raúl. 2007. Mozarabs, Hispanics, and the Cross. Maryknoll: Orbis Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzálvez, Ramón. 1985. The Persistence of the Mozarabic Liturgy in Toledo after A.D. 1080. In Santiago, Saint-Denis, and Saint Peter: The Reception of the Roman Liturgy in León-Castile in 1080. Edited by Bernard Reilly. New York: Fordham University Press, pp. 157–86. [Google Scholar]

- Grimes, Ronald L. 2010. Ritual Criticism: Case Studies in Its Practice, Essays on Its Theory. Waterloo: Ritual Studies International. [Google Scholar]

- Hillgarth, Jocelyn N. 2009. The Visigoths in History and Legend. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Hitchcock, Richard. 2016. Mozarabs in Medieval and Early Modern Spain: Identities and Influences. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hornby, Emma, and Rebecca Maloy. 2013. Music and Meaning in Old Hispanic Lenten Chants Psalmi, Threni and the Easter Vigil Canticles. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. [Google Scholar]

- Janowiak, Paul. 2011. Standing Together in the Community of God: Liturgical Spirituality and the Presence of Christ. Collegeville: Liturgical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Sarah. 2021. The Roles of Christian Ritual in Increasingly Nonreligious and Religiously Diverse Social Contexts: The Case of Anglican Baptisms and Funerals in Toronto. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- King, Archdale A. 1957. Liturgies of the Primatial Sees. London: Longmans, Green and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Knoebel, Thomas L., ed. 2008. Isidore of Seville: De Ecclesiasticis Officiis. New York: Newman Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koon, Sam, and Jamie Wood. 2009. Unity from Disunity: Law, Rhetoric and Power in the Visigothic Kingdom. European Review of History: Revue Européenne D’histoire 16: 793–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linehan, Peter. 1993. History and the Historians of Medieval Spain. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzana, Francisco. 1770. Missa Gothica seù Mozarabica, et Officium itidèm Gothicum, diligentèr ac dilucidè explanata ad usum percelebris Mozárabum Sacelli Toleti á munificentissimo Cardinali Ximenio erecti. Angelopoli: Typis Seminarii Palafoxiani. [Google Scholar]

- Maloy, Rebecca. 2020. Songs of Sacrifice: Chant, Identity, and Christian Formation in Early Medieval Iberia. AMS Studies in Music Series; New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, Nathaniel. 2013. Ritual in the Age of Authenticity: An Ethnography of Latin Mass Catholics. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, Nathan. 1999. Liturgy and the Social Sciences. Collegeville: Liturgical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, Nathan. 2009. The Significance of Ritual Studies for Liturgical Research. In Die Modernen Ritual Studies Als Herausforderung für die Liturgiewissenshaft/Modern Ritual Studies as a Challenge for Liturgical Studies as a Challenge for Liturgical Studies. Edited by B. Kranemann and P. Post. Dudley: Peeters, pp. 63–85. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, Aaron Michael. 2012. Arabicizing, Privileges, and Liturgy in Medieval Castilian Toledo: The Problems and Mutations of Mozarab Identification (1085–1436). Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Perea, Antonio. 2005. Escrito de nuestro Hermano Mayor. Crónica Mozárabe 62: 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan, Joseph F. 2013. Reconquest and Crusade in Medieval Spain. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Orlandis, José. 1976. La Iglesia en la España Visigótica y Medieval. Colección Historia de la Iglesia 8. Pamplona: Ediciones Universidad de Navarra. [Google Scholar]

- Orlandis, José. 1977. Historia de España: La España Visigótica. Madrid: Gredos. [Google Scholar]

- Orlandis, José. 1984. Hispania y Zaragoza En La Antigüedad Tardía: Estudios Varios. Zaragoza: Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Orlandis, José. 1992. Semblanzas Visigodas. Madrid: Ediciones Rialp. [Google Scholar]

- Parenti, Stefano. 1991. Influssi italo-greci nei testi eucaristici bizantini dei ‘Fogli Slavi’ del Sinai (XI sec.). OCP 57: 145–77. [Google Scholar]

- Parenti, Stefano. 1997. L’Eucologio Slavo del Sinai Nella Storia Dell’eucologio Bizantino. Rome: Università di Roma “La Sapienza”. [Google Scholar]

- Parenti, Stefano. 2010. Towards a Regional History of the Byzantine Euchology of the Sacraments. Ecclesia Orans 27: 109–21. [Google Scholar]

- Parenti, Stefano. 2014. L’eredità liturgica di Gerusalemme nelle periferie di Bisanzio e tra gli Slavi meridionali. In Una Città tra Terra e Cielo. Gerusalemme: Le Religioni, le Chiese. Edited by Cesare Alzati and Luciano Vaccaro. Vatican City: Libreria Ed. Vaticana, pp. 289–304. [Google Scholar]

- Parenti, Stefano. 2020. L’anafora di Crisostomo. Münster: Aschendorff Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan, Owen Michael. 2014. The Formation of Christian Europe: The Carolingians, Baptism, and the Imperium Christianum, 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pinell I Pons, Jordi. 1997. History of the Liturgies in the Non-Roman West. In Introduction to the Liturgy. Edited by Anscar J. Chupungco. Handbook for Liturgical Studies 1. Collegeville: Liturgical Press, pp. 179–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, Melanie C. 2014. Evangelical versus Liturgical? Defying a Dichotomy. Calvin Institute of Christian Worship Liturgical Studies Series; Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Rouco Varela, Antonio Mª. 2001. Decreto sobre la celebración de la Eucaristía en rito hispano-mozárabe en Madrid. Madrid: Archidiócesis de Madrid—Boletín Diocesano. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio Sadia, Juan Pablo. 2004a. La introducción del rito romano en la iglesia de Toledo: El papel de la órdenes religiosas a través de la fuentes litúrgicas. Toletana 10: 151–77. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio Sadia, Juan Pablo. 2004b. Las órdenes religiosas y la introducción del rito romano en la iglesia de Toledo: Una aportación desde las fuentes litúrgicas. Toledo: Instituto Teológico San Ildefonso. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio Sadia, Juan Pablo. 2006. El Cambio de Rito en Castilla: Su Iter Historiográfico en los Siglos XII y XIII. Hispania Sacra 58: 9–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rubio Sadia, Juan Pablo. 2011a. Del rito hispano al rito romano: La transición litúrgica de los reinos ibéricos en la España Sagrada de Enrique Flórez. Ciudad de Dios: Revista agustiniana 3: 680–719. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio Sadia, Juan Pablo. 2011b. Introducción del rito romano y reforma de la Iglesia hispana en el siglo XI: De Sancho III el Mayor a Alfonso VI. In La Reforma Gregoriana en España. Edited by J. M. Magaz and N. Alvarez. Madrid: Publicaciones de la Facultad de Teología San Dámaso, pp. 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio Sadia, Juan Pablo. 2011c. Narbona y la romanización litúrgica de las iglesias de Aragón. Miscel·Lània Litúrgica Catalana 19: 267–321. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio Sadia, Juan Pablo. 2018a. La Transición al Rito Romano en Aragón y Navarra: Fuentes, Escenarios, Tradiciones, I Edizione. Napoli: EDI. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio Sadia, Juan Pablo. 2018b. Los mozárabes frente al rito romano: Balance historiográfico de una relación polémica. Espacio, Tiempo y Forma. Serie III, Historia Medieval 31: 619–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruff, Anthony. 2007. Sacred Music and Liturgical Reform: Treasures and Transformations. Chicago: Liturgy Training Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, Ramon Gonzalvez. 2004. Cisneros y la Reforma del Rito Hispano-Mozarabe. Anales Toledanos 40: 165–207. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Montealegre, Cleofé. 1988. Aprobada la Reforma del Rito Mozárabe. Crónica Mozárabe 22: 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Seah, Audrey. 2021. Signs of Hope: Narratives, Eschatology, and Liturgical Inculturation in Deaf Catholic Worship. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Searle, Mark. 1992. Ritual. In The Study of Liturgy. Edited by Cheslyn Jones, Edward Yarnold S. J., Geoffrey Wainwright and Paul Bradshaw. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra López, Juan Manuel. 2020. Delegación Diocesana para el Rito Hispano-Mozárabe: Una Nueva Congregación del Rito Hispano-Mozárabe. Boletín Oficial del Arzobispado de Toledo 174: 208–16. [Google Scholar]

- Stocking, Rachel L. 2000. Bishops, Councils, and Consensus in the Visigothic Kingdom, 589–633. History, Languages, and Cultures of the Spanish and Portuguese Worlds. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taft, Robert. 2001. Anton Baumstark’s Comparative Liturgy Revisited. In Comparative Liturgy Fifty Years after Anton Baumstark (1872–1948). Edited by Robert Taft and Gabriele Winkler. Rome: Pontificio Istituto Orientale, pp. 191–232. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Rose. 1998. Views of Transition: Liturgy and Illumination in Medieval Spain. The British Library Studies in Medieval Culture. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, Gabriele. 1982. Das Armenische Initiationsrituale: Entwicklungeschichtliche und Liturgievergleinchende Untersuchung der Quellen des 3. bis 10. Jahrhunderts. Roma: Pont. Institutum Studiorum Orientalium. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Jamie. 2006. Elites and Baptism: Religious ‘Strategies of Distinction’ in Visigothic Spain. In Elite and Popular Religion: Papers Read at the 2004 Summer Meeting and the 2005 Winter Meeting. Edited by Kate Cooper and Jeremy Gregory. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Jamie P. 2012. The Politics of Identity in Visigoth Spain: Religion and Power in the Histories of Isidor of Seville. Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Susan K. 2000. Sacramental Orders. Collegeville: Liturgical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Susan K., and Michael Downey, eds. 2003. Ordering the Baptismal Priesthood: Theologies of Lay and Ordained Ministry. Collegeville: Liturgical Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chase, N.P. Crisis, Liturgy, and Communal Identity: The Celebration of the Hispano-Mozarabic Rite in Toledo, Spain as a Case Study. Religions 2022, 13, 216. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13030216

Chase NP. Crisis, Liturgy, and Communal Identity: The Celebration of the Hispano-Mozarabic Rite in Toledo, Spain as a Case Study. Religions. 2022; 13(3):216. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13030216

Chicago/Turabian StyleChase, Nathan P. 2022. "Crisis, Liturgy, and Communal Identity: The Celebration of the Hispano-Mozarabic Rite in Toledo, Spain as a Case Study" Religions 13, no. 3: 216. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13030216

APA StyleChase, N. P. (2022). Crisis, Liturgy, and Communal Identity: The Celebration of the Hispano-Mozarabic Rite in Toledo, Spain as a Case Study. Religions, 13(3), 216. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13030216