Combating Sex Trafficking: The Role of the Hotel—Moral and Ethical Questions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Source of Cases

2.2. Background of Hotels and Corporations

3. Results

3.1. Case Analysis

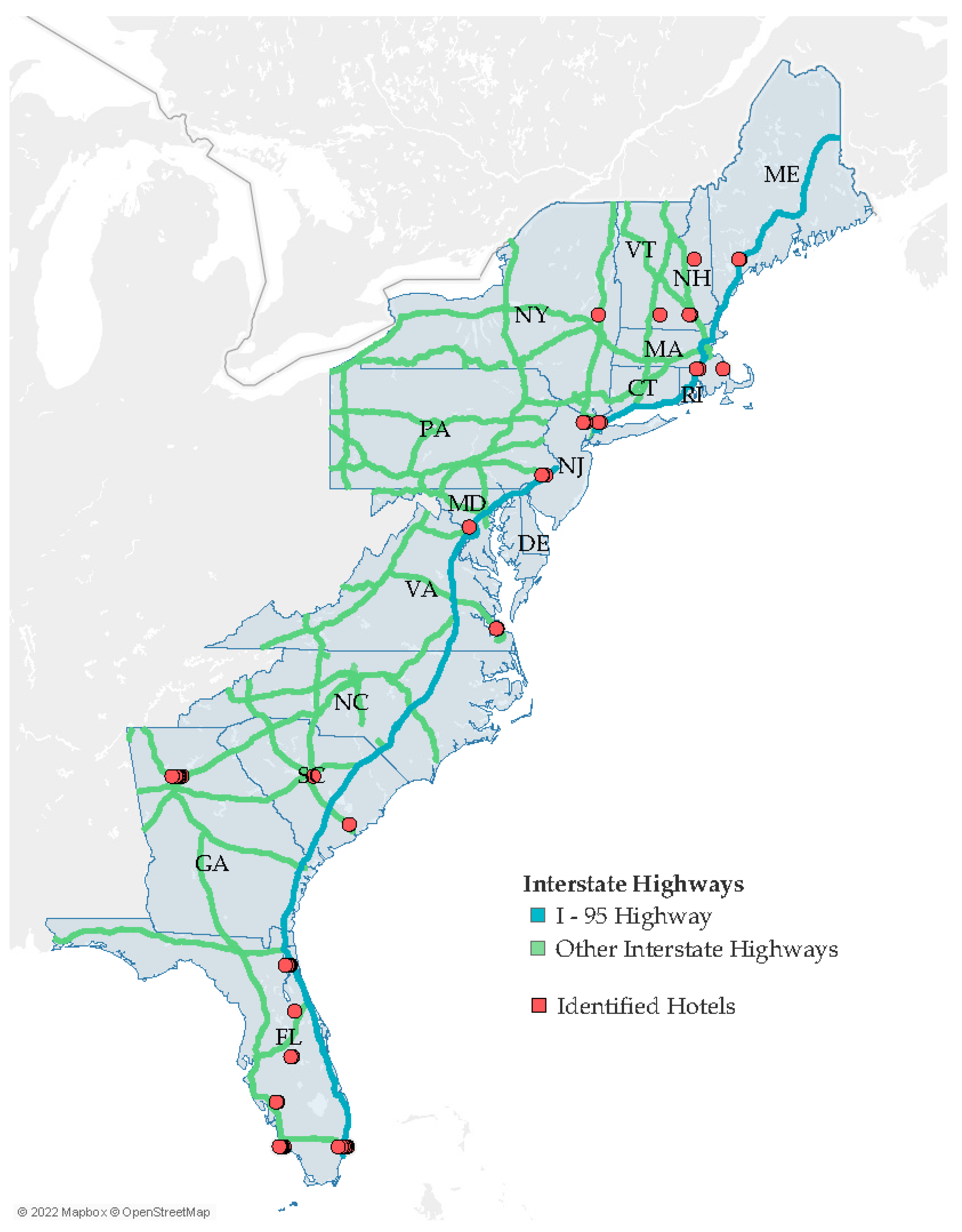

3.2. Location Analysis of the Identified Hotels

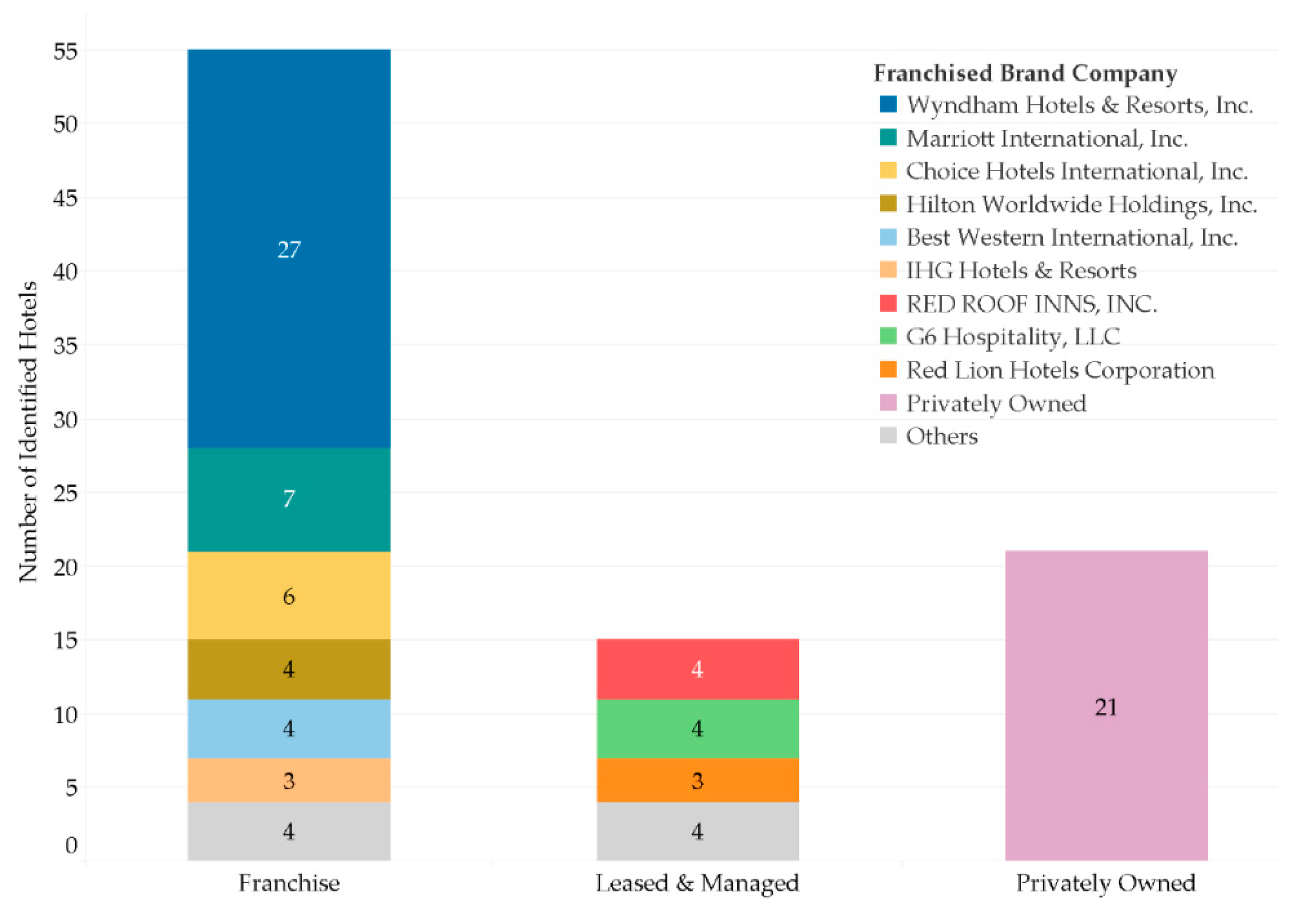

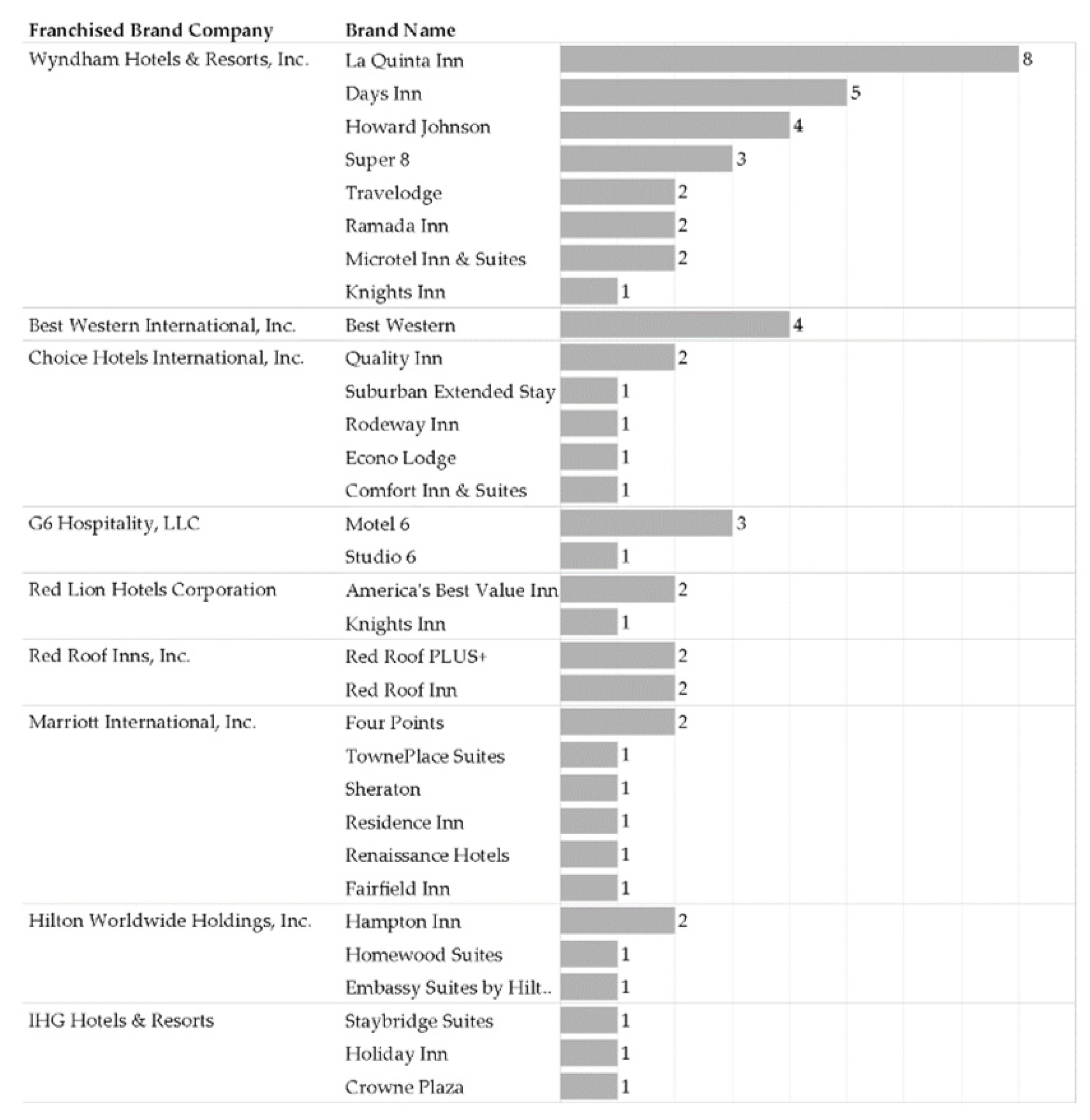

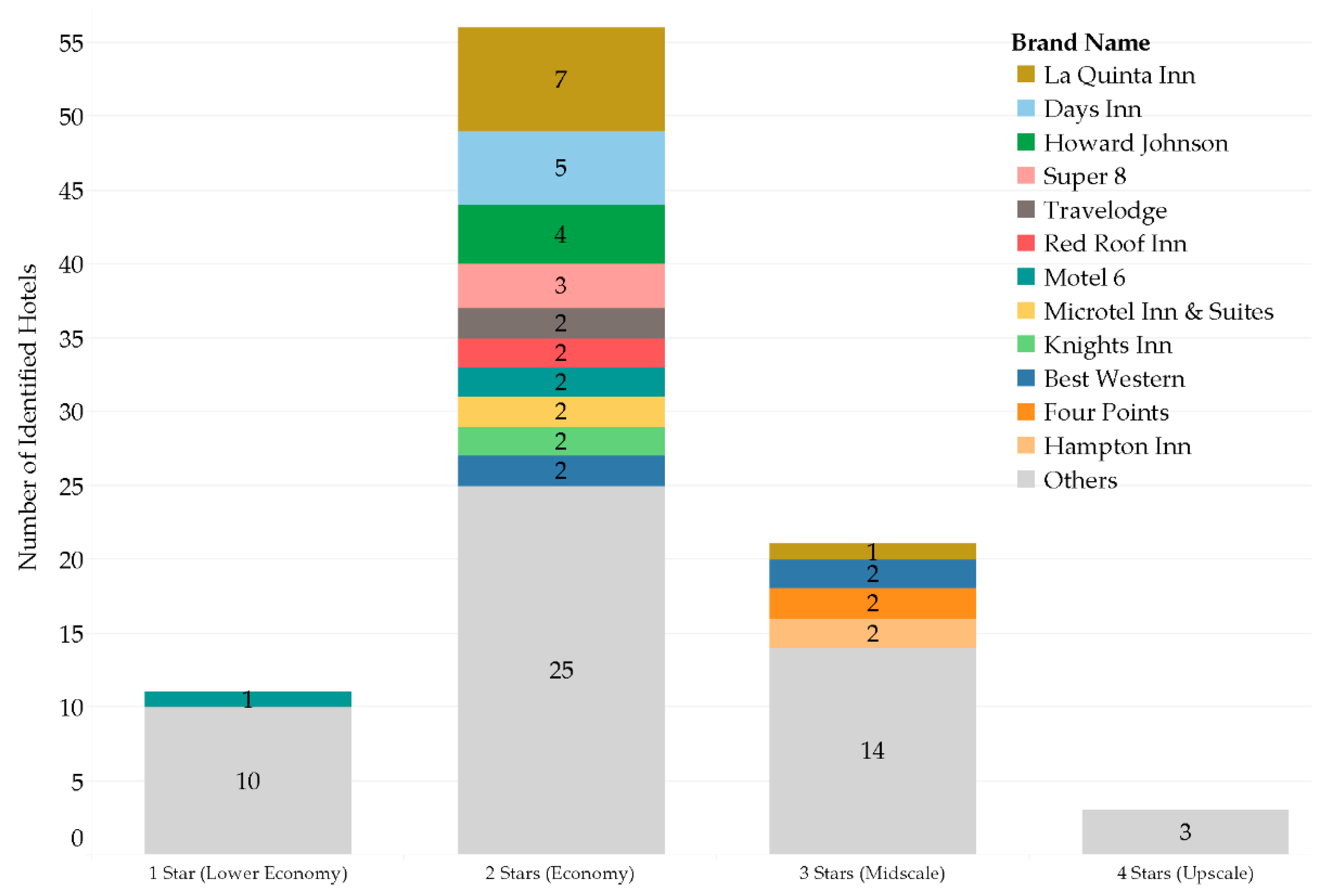

3.3. Hotels/Motels Brand and Chain Analysis

3.4. Summary of Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Hotels Become a Hotspot of Sex Trafficking

4.2. Ethical and Moral Questions in Reference to Hotels and Hotel Chains

4.3. The Commitment to End Human Trafficking by Hotel Groups

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Public Company Defendants | Private Company Defendants | Hotel Brands Identified |

|---|---|---|

| N/A | Best Western International, Inc.; R&M Real Estate Co. Inc. | Best Western; Best Western Plus |

| Choice Hotels International, Inc. (CIK#1046311) | Jav, Inc.; R&M Real Estate Co. Inc.; Rosen International, Inc. (d/b/a Rodeway Inn International); SUB-SU Hotel GP, LLC; Westmont Hospitality Group; WHG SU Atlanta LP | Comfort Inn & Executive Suites; Econo Lodge; Quality Inn; Rodeway Inn; Suburban Extended Stay |

| Blackstone Group, Inc. (CIK 0001393818) | G6 Hospitality LLC; Aarshivard LLC; Motel 6 Corporation | Motel 6; Studio 6 |

| Hilton Worldwide Holdings, Inc. (CIK#1585689) | 2014 SE Owner 5-Emory, LLC; Auro Hotels Management, LLC; Hilton Domestic Operating Company, Inc.; Hilton Franchise Holdings, LLC; JHM Hotels Management, Inc.; Laxmi Druid Hills Hotel, LLC | Embassy Suites; Hampton Inn; Homewood Suites |

| Hyatt Hotels Corporation (CIK#1468174) | N/A | Hyatt Regency |

| Inter-Continental Hotels Corp. (listed in this Appendix as Inter-Continental Hotels Group PLC (CIK#858446)) | Holiday Hospitality Franchising, LLC; Naples CFC Enterprises, Ltd. | Crowne Plaza; Holiday Inn; Staybridge Suites |

| Marriott International, Inc. (CIK#1048286) | CSM Corporation; CSM RI Naples, LLC; Residence Inn by Marriott, LLC | Four Points by Sheraton; Renaissance; Residence Inn; Fairfield Inn; TownePlace Suites |

| N/A | Red Lion Hotels Corp. (acquired by Sonesta International Hotels Corporation in March 2021); Vad Property Management, LLC; Vantage Hospitality Group, Inc. | America’s Best Value Inn Knights Inn (4 April 2018-present)9 |

| N/A | Red Roof Inns, Inc.; FMW RRI NC, LLC; Red Roof Franchising, LLC RRI III, LLC; RRI West Management, LLC; R-Roof Asset, LLC; Varahi Hotel, LLC; Westmont Hospitality Group, Inc.; | Red Roof Inn; Red Roof Plus+ |

| Wyndham Hotels & Resorts, Inc. (CIK#0001722684); CorePoint Lodging, Inc. (CIK#0001707178) | CPLG Holdings, LLC; CPLG LLC; CPLG Properties, LLC; Days Inn Worldwide, Inc.; Hanuman of Naples, LLC; H.I. of Naples, LLC; Howard Johnson International, Inc.; Jeet & JJ LLC; Kuzzins Buford, Inc.; La Quinta Holdings, Inc.; La Quinta Properties, Inc.; La Quinta Worldwide, LLC; Laxmi of Naples, LLC; Lincoln Hospitality Group, LLC; Lincoln Hotels, LLC; LQ Management LLC; LQ FL Properties, LLC; Microtel Inns and Suites Franchising, Inc.; Newtel V Corporation; Ramada Worldwide, Inc.; Rist Properties LLC; Shanta Hospitality, LLC; Shree Siddhivinayak Hospitality, LLC | Days Inn; Howard Johnson; Knights Inn (2006–3 April 2018: see note 9); La Quinta; Microtel Inn & Suites; Ramada; Super 8; Travelodge |

| 1 | Ricchio v. McLean et al., 2015. United States District Court for Massachusetts. 1:15-cv-13519. |

| 2 | Doe C.D. v. R-Roof Asset. 2019. United States District Court for Massachusetts. 1:19−cv−11192−NMG. |

| 3 | R.E. v. Lincoln Hotel, LLC et al., 2020. United States District Court for Georgia Northern. 1:20-cv-03335. |

| 4 | W.K. v. Red Roof Inns Inc. et al., 2020. U.S. District Court for Georgia Northern. 1:20-cv-05263. |

| 5 | S.J. v. Choice Hotels Corporation et al., 2019. United States District Court for the New York Eastern. 1:19-cv-06071-DG-PK. |

| 6 | Highway Ramp: This ramp of the main interstate (I-95), the major intersections (I-4, 10, 16, 20, 26, 40, 64, 74, 76, 78, 80, 85, 87, 90, 91, 93), auxiliary routes (I-195, 295, 395, 495, 595, 695, 795, 895) and the other routes (I-276, 476, 676, 287, 278, 678, 280). |

| 7 | B. v. Inter−Continental Hotels Corporation et al., 2019. United States District Court for New Hampshire. 1:19-cv-01213-AJ; E.B. v. Howard Johnson by Wyndham Newark et al., 2021. United States District Court for New Jersey. 2:21-cv-02901-SDW-LDW; R.E. v. Lincoln Hotel, LLC et al., 2020. United States District Court for Georgia Northern. 1:20-cv-03335. |

| 8 | Parent/Major Hotel Companies marked in bold. |

| 9 | Red Lion Hotels Corporation announced its acquisition of Knights Inn from Wyndham Hotel Group on 4 April 2018. The acquisition was completed on 14 May 2018. |

References

- Anthony, Brittany, Sara Crowe, Caren Benjamin, Therese Couture, Elaine McCartin, Elizabeth Gerrior, Lillian Agbeyegbe, Mary Kate Kosciusko, Lyn Leeburg, and Hanni Stoklosa. 2018. On-Ramps, Intersections and Exit Routes: A Roadmap for Systems and Industries to Prevent and Disrupt Human Trafficking: Hotels and Motels; Polaris. Available online: https://polarisproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/A-Roadmap-for-Systems-and-Industries-to-Prevent-and-Disrupt-Human-Trafficking-Hotels-and-Motels.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Atkins, Sabrina, and Pamela Lee. 2021. Key Factors in the Industry’s Fight against Human Trafficking. Hotel Management. April 24. Available online: https://www.hotelmanagement.net/legal/4-ways-to-protect-hotels-from-human-trafficking-lawsuits (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Bailey, Analis. 2020. Major League Baseball Umpire Brian O’Nora Was Arrested in Ohio in Human Trafficking Sting. December 7. Available online: https://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/mlb/2020/12/07/brian-onora-mlb-umpire-arrested-sex-sting-operation/6483082002/ (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Bain, Christina, and Louise Shelley. 2015. Hedging Risk by Combating Human Trafficking: Insights from the Private Sector, World Economic Forum. Available online: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Human_Trafficking_Report_2015.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Blackstone Inc. 2021. Our Approach to ESG. Blackstone Inc. Available online: https://www.blackstone.com/our-impact/our-approach-to-esg/ (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Blue Lightening Initiative. 2021. U.S. Department of Transportation. Available online: https://www.transportation.gov/administrations/office-policy/blue-lightning-initiative (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Buzzfile Media LLC. 2021. The Most Advanced Company Information Database; New York: Buzzfile Media LLC. Available online: https://www.buzzfile.com/ (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Carlson. 2018. Carlson’s Leadership in the Prevention of Human Trafficking; Bangkok: ECPAT International. Available online: https://ecpat.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Expert-Paper-Carlson.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- EDGAR. 2021. Company and Person Lookup; Company Filings. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Available online: https://www.sec.gov/edgar/searchedgar/companysearch.html (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Feehs, Kyleigh, and Alyssa Currier. 2019. 2018 Federal Human Trafficking Report. Fairfax: Human Trafficking Institute, Available online: https://www.traffickinginstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/2018-Federal-Human-Trafficking-Report-Low-Res.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Feehs, Kyleigh, and Alyssa Currier. 2020. 2019 Federal Human Trafficking Report. Fairfax: Human Trafficking Institute, Available online: https://www.traffickinginstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/2019-Federal-Human-Trafficking-Report_Low-Res.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Feehs, Kyleigh, and Alyssa Currier Wheeler. 2021. 2020 Federal Human Trafficking Report. Fairfax: Human Trafficking Institute, Available online: https://www.traffickinginstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/2020-Federal-Human-Trafficking-Report-Low-Res.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- G6 Hospitality LLC. 2020a. Combating Human Trafficking. G6 Hospitality LLC. Available online: https://g6hospitality.com/about-us/combating-human-trafficking/ (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- G6 Hospitality LLC. 2020b. Motel 6 Expands Human Trafficking Awareness and Prevention Efforts through Partnerships with Truckers Against Trafficking and New Friends New Life. G6 Hospitality LLC, January 16. Available online: https://g6hospitality.com/motel-6-expands-human-trafficking-awareness-and-prevention-efforts-through-partnerships-with-truckers-against-trafficking-and-new-friends-new-life/ (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Gamiz, Manuel, Jr. 2019. Backpage is gone, but a more graphic version is again fueling prostitution busts in the Lehigh Valley. The Morning Call. April 5. Available online: https://www.mcall.com/news/breaking/mc-pol-sex-trafficking-backpage-shutdown-skip-the-games-20190322-story.html (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Graif, Corina, Andrew S. Gladfelter, and Stephen A. Matthews. 2014. Urban Poverty and Neighborhood Effects on Crime: Incorporating Spatial and Network Perspectives. Sociology Compass 8: 1140–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilton Worldwide Inc. 2011. Hilton Worldwide Signs Tourism Code of Conduct, Joins ECPAT-USA in Fight against Child Trafficking in the Travel Sector. Hilton Worldwide Inc., April 14. Available online: https://perma.cc/7XL2-MZWJ (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Leary, Mary Graw. 2019. History Repeats Itself: Some New Faces Behind Sex Trafficking Are More Familiar Than You Think. Emory Law Journal Online 68: 1083–108. Available online: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj-online/9/ (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Marriott International Inc. 2021a. Marriott International Launches Enhanced Human Trafficking Awareness Training. News Center. Marriott International, Inc., July 28. Available online: https://news.marriott.com/news/2021/07/28/marriott-international-launches-enhanced-human-trafficking-awareness-training (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Marriott International Inc. 2021b. Marriot International Reports on Environment, Social, and Governance Progress. News Center. Marriott International, Inc., September 14. Available online: https://news.marriott.com/news/2021/09/14/marriott-international-reports-on-environmental-social-and-governance-progress (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Milrod, Christine, and Martin A. Monto. 2012. The Hobbyist and the Girlfriend Experience: Behaviors and Preferences of Male Customers of Internet Sexual Service Providers. Deviant Behavior 33: 792–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PACER. 2021. Public Access to Court Electronic Records. Available online: https://pacer.uscourts.gov/ (accessed on 31 August 2021).

- Ramey, Corinne. 2020. Lawsuits Accuse Big Hotel Chains of Allowing Sex Trafficking: Dozens of Women Say Hilton, Marriott, Wyndham and Others Turned a Blind Eye to Organized Prostitution at Their Establishments, March 4. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/lawsuits-accuse-big-hotel-chains-of-allowing-sex-trafficking-11583317800 (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Ratzesberger, Oliver, Sarah Arana-Morton, Chris Taggart, Julia Apostle, and Alessia Falsarone. 2021. Opencorporates: The Largest Open Database of Companies in the World. Available online: https://opencorporates.com/ (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Roe-Sepowitz, Dominique, Stephanie Bontrager, Justin T. Pickett, and Anna E. Kosloski. 2019. Estimating the sex buying behavior of adult males in the United States: List experiment and direct question estimates. Journal of Criminal Justice 63: 41–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagduyu, Cory. 2020. Nightmare in Shangri-La: Consequences Likely for Entities Who Benefit from Human Trafficking. Trafficking Matters. Available online: https://www.traffickingmatters.com/nightmare-in-shangri-la-consequences-likely-for-entities-who-benefit-from-human-trafficking/ (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Shavers, Anna Williams. 2012. Human trafficking, the rule of law, and corporate social responsibility. The South Carolina Journal of International Law and Business 9: 39–88. Available online: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/scjilb/vol9/iss1/6/ (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Shelley, Louise. 2010a. Categorization of Trafficking Groups as Different Business Types or Criminal Enterprises. In Human Trafficking: A Global Perspective. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, p. 114. ISBN 978-0-521-11381-6. [Google Scholar]

- Shelley, Louise. 2010b. Trafficking in the United States. In Human Trafficking: A Global Perspective. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 229–64. ISBN 978-0-521-11381-6. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Linda, and Samantha Healy Vardaman. 2010. The Problem of Demand in Combating Sex Trafficking. Revue Internationale de Droit Pénal 81: 607–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- THECODE.ORG. 2021. Our Members. We Protect Children in Travel and Tourism. THECODE.ORG. ECPAT. Available online: http://thecode.org/ourmembers/ (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- The New York Times. 2021. Private Equity Funds, Sensing Profit in Tumult, Are Propping Up Oil. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/13/climate/private-equity-funds-oil-gas-fossil-fuels.html?searchResultPosition=1 (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- United Nations University. 2019. Unlocking Potential: A Blueprint for Mobilizing Finance against Slavery and Trafficking. New York: United Nations University Centre for Policy Research, ISBN 978-92-808-6508-0. Available online: https://www.fastinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/Blueprint-DIGITAL-3.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- UNODC. 2021. The Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Trafficking in Persons and Responses to the Challenges: A Global Study of Emerging Evidence. Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Available online: https://www.unodc.org/documents/human-trafficking/2021/The_effects_of_the_COVID-19_pandemic_on_trafficking_in_persons.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Weisburd, David. 2015. The Law of Crime Concentration and The Criminology of Place. American Society of Criminology 53: 133–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act. 2008. Pub. L. No. 110-457, 122 Stat. 5044. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-122/pdf/STATUTE-122-Pg5044.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- World Travel & Tourism Council. 2021. Economic Impact Reports. London: World Travel & Tourism Council, Available online: https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact (accessed on 18 October 2021).

| States or Federal District | Number of Civil Cases | Number of Entity Defendants | Number of Sex Trafficking Cases That Involve Hotels | Number of Defendants Categorized as “Hotels” | Number of Identified Hotels |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connecticut | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Delaware | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| District of Columbia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Florida | 7 | 75 | 5 | 51 | 42 |

| Georgia | 9 | 58 | 6 | 42 | 14 |

| Maine | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Maryland | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Massachusetts | 3 | 11 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| New Hampshire | 1 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 5 |

| New Jersey | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| New York | 26 | 173 | 2 | 8 | 3 |

| North Carolina | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pennsylvania | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Rhode Island | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| South Carolina | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Vermont | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Virginia | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| West Virginia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Grand Total | 53 | 225 | 21 | 114 | 77 |

| States or Federal District | City/County of the Hotel Location (Number of the Identified Hotels in Each City/County) | Number of the Identified Hotels |

|---|---|---|

| Connecticut | None | 0 |

| Delaware | None | 0 |

| District of Columbia | None | 0 |

| Florida | Coral Springs (1), Fort Lauderdale (4), Fort Myers (5), Jacksonville (9), Kissimmee (2), Naples (20), Orlando (2), Plantation (3), Sunrise (1) | 47 |

| Georgia | Alpharetta (2), Atlanta (4), Chamblee (1), Conley (1), Decatur (1), Jonesboro (2), Marietta (1), Morrow (1), Smyrna (1) | 14 |

| Maine | Portland (2), South Portland (2) | 4 |

| Maryland | None | 0 |

| Massachusetts | Framingham (1), Marshfield (1), Seekonk (1) | 3 |

| New Hampshire | Concord (2), Keene (1), Tilton (1), Gilford (1) | 5 |

| New Jersey | Elizabeth (6), Newark (1) | 7 |

| New York | Bronx (1), Queens (1), Albany (1) | 3 |

| North Carolina | None | 0 |

| Pennsylvania | Philadelphia (3) | 3 |

| Rhode Island | None | 0 |

| South Carolina | Charleston (1), Columbia (1), North Charleston (1) | 3 |

| Vermont | None | 0 |

| Virginia | Hampton (2) | 2 |

| West Virginia | None | 0 |

| Grand Total | 91 |

| Case Source | Filed Year | Number of Filed Cases | Number of the Identified Hotels from the Cases | Number of Case Terminated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Trafficking Institute | 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2019 | 10 | 36 | 6 | |

| 2020 | 10 | 40 | 7 | |

| Individual Search | 2021 | 3 | 14 | 0 |

| Total | 24 | 91 | 14 |

| Period of Time Until the File Closed | Number of Cases Terminated |

|---|---|

| Around 4 years | 1 |

| Around 2 years | 1 |

| Around 1 year | 11 |

| Less than 1 year | 1 |

| In Progress | 10 |

| States or Federal District | Number of the Identified Hotels | Near Highway Ramp6 | Near International Airport | Near Casinos | Near Resorts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connecticut | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Delaware | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| District of Columbia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Florida | 47 | 47 | 27 | 43 | 45 |

| Georgia | 14 | 14 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| Maine | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Maryland | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Massachusetts | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| New Hampshire | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| New Jersey | 7 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 0 |

| New York | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| North Carolina | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pennsylvania | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Rhode Island | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| South Carolina | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Vermont | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Virginia | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| West Virginia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Grand Total | 91 | 89 | 61 | 57 | 48 |

| Percentage | 100% | 98% | 67% | 63% | 53% |

| Hotel & Motels | Management | Facilities Service | Real Estate | Investment | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 61% (74) | 17% (20) | 7% (8) | 6% (7) | 3% (4) | 7% (8) |

| Name of the Hotel Chain | Starting Year of Signed Agreement with ECPAT | Implementation Status as of July 2021 |

|---|---|---|

| Wyndham Hotels & Resorts | 2011 | 50% |

| Hilton Worldwide | 2011 | 33% |

| Choice Hotels International | 2015 | 67% |

| Red Roof Inns | 2016 | 67% |

| Marriott International, Inc. | 2018 | 17% |

| InterContinental Hotels Group (IHG) | 2019 | 17% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeng, C.-C.; Huang, E.; Meo, S.; Shelley, L. Combating Sex Trafficking: The Role of the Hotel—Moral and Ethical Questions. Religions 2022, 13, 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13020138

Jeng C-C, Huang E, Meo S, Shelley L. Combating Sex Trafficking: The Role of the Hotel—Moral and Ethical Questions. Religions. 2022; 13(2):138. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13020138

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeng, Chu-Chuan, Edward Huang, Sarah Meo, and Louise Shelley. 2022. "Combating Sex Trafficking: The Role of the Hotel—Moral and Ethical Questions" Religions 13, no. 2: 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13020138

APA StyleJeng, C.-C., Huang, E., Meo, S., & Shelley, L. (2022). Combating Sex Trafficking: The Role of the Hotel—Moral and Ethical Questions. Religions, 13(2), 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13020138