Writing and Worship in Deng Zhimo’s Saints Trilogy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Saints Trilogy

3. Composite Texts: The Saints Trilogy as Multi-Layered Hagiographies

- In the morning I travel to Beihai, in the evening to Cangwu,

- Courageous and irascible, a green snake in my sleeve.19

- Thrice I was intoxicated in Yueyang [but] no one recognized me,

- Thus I fly across Dongting Lake.

If the iron tree blooms, and this demon will revive, I shall return.If the iron tree follows the right path, this demon will be subdued forever.Water demons are now expelled from this site, towns and villages need not worry.

The iron tree controls the streams, in ten thousand years it will never rest.(If) the world is in chaos, this place will have nothing to worry about.(If) a drought pervades the land, this place will receive ample (rain).

4. The Trilogy in the World of Late Ming Publishing

“How to see Patriarch Lü? It is by collating the traces of his life (yishi 遺事) and his poetry, wherein the patriarch’s own voice is preserved. I believe Patriarch Lü is present in his poetry. In the past, Sima Ziwei 司馬子微 [Sima Chengzheng, 647–735] studied the Master Concealed in Heaven [Tianyin zi 天隠子, DZ 1026] for three years, and received the teachings by which to test those who seek the Dao. Every chapter can be verified. How would it be possible that Patriarch Lü won’t reveal himself to those who seek the Dao like Master Sima? To those who admire Lü, he will appear in a dream. If one admires Lü through the real traces of his life and by reciting his poetry, this would be like encountering Patriarch Lü himself. Therefore, it is impossible not to read this compilation (ji 集). I named this compilation The Flying Sword”.

5. Coda

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Throghout this article, I use the term “publishing” when referring to the producers of the works (authors, editors, printers, etc.) and the terms “print culture” and “book culture” to refer more broadly to all those partaking in the production, circulation, and consumption of books (i.e., producers, merchants, and audiences). |

| 2 | The local roots of Xu Xun’s reverence continued to shape his lore during the Ming, centuries after the rise of his cultic worship. For instance, the local gazetteer Jiangxi tongzhi 江西通志 includes over a dozen entries from the Ming alone that describe the local origins of the Xu cult. |

| 3 | Some Lüshan temples in Fujian identify Xu Xun with Jiulang fazhu 九郎法主, though in Jianyang this title is often used to designate two figures: Xu Xun and Xu Jia 徐甲. See (Ye and Lagerwey 2007, pp. 10–11, 362–64). |

| 4 | The anonymous, supposedly thirteenth-century Xu taishi zhenjun tuzhuan is composed of a series of fifty-three units of text and image. Its narrative follows Bai Yuchan’s hagiography very closely. This pictorial hagiography opens with two (unillustrated) prefaces: the first is titled Yulong xizhao 玉陛锡詔 (“the imperial order granted on the jade steps”) which includes an edict from the Jade Emperor delivered to Xu Xun by two immortals, and the second entitled Zhenjun shenggao 真君聖誥 (“granting the divine title Perfected Saint”), which lists Xu Xun’s titles and praises his filiality and humaneness. Akizuki Kanei dates this text around 1295, but Xu Wei argues that it is difficult to ascertain the dating of texts that were later included in the Daoist canon in 1445; see Xu (2011, p. 119). |

| 5 | According to Schipper, the cult of Xu Xun was among the most prominent Daoist traditions of the Song and Yuan Dynasties; see Schipper (1985, p. 813). It is noteworthy that alongside Xu Xun’s portrayals in hagiographic, doctrinal, and liturgical sources, local gazetteers since the Song dynasty propagated Xu reverence and legitimized his temples, bridging Daoist ritual and popular worship of Xu Xun; see Chen and Wang (2014, pp. 56–64). |

| 6 | Schipper argues that the Jingming Dao did not offer any new rituals or liturgies, but was rather a local school within the framework of the Lingbao tradition, whose uniqueness lies precisely in its relationship with a local cult—the Xu Xun cult; see Schipper (1985, pp. 827–28). |

| 7 | The album is housed in the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia. See Boltz (2004, pp. 191–238) and Wang (2012, p. 69, note 46). On Xie Shichen, see Ju-yu (1997, pp. 1–26). |

| 8 | Certain sources describe Deng as a native of Raozhou 饒州, Anren county安仁縣, Jiangxi, whereas other sources claim he hails from Yuzhang, near Nanchang, Jiangxi. The Sikuquanshu zongmu tiyao 四庫全書總目提要 describes Deng as a man of Rao’an (饒安人), though Sun Kaidi, among others, argue that this is unlikely; see Bai (2005, pp. 75–77). |

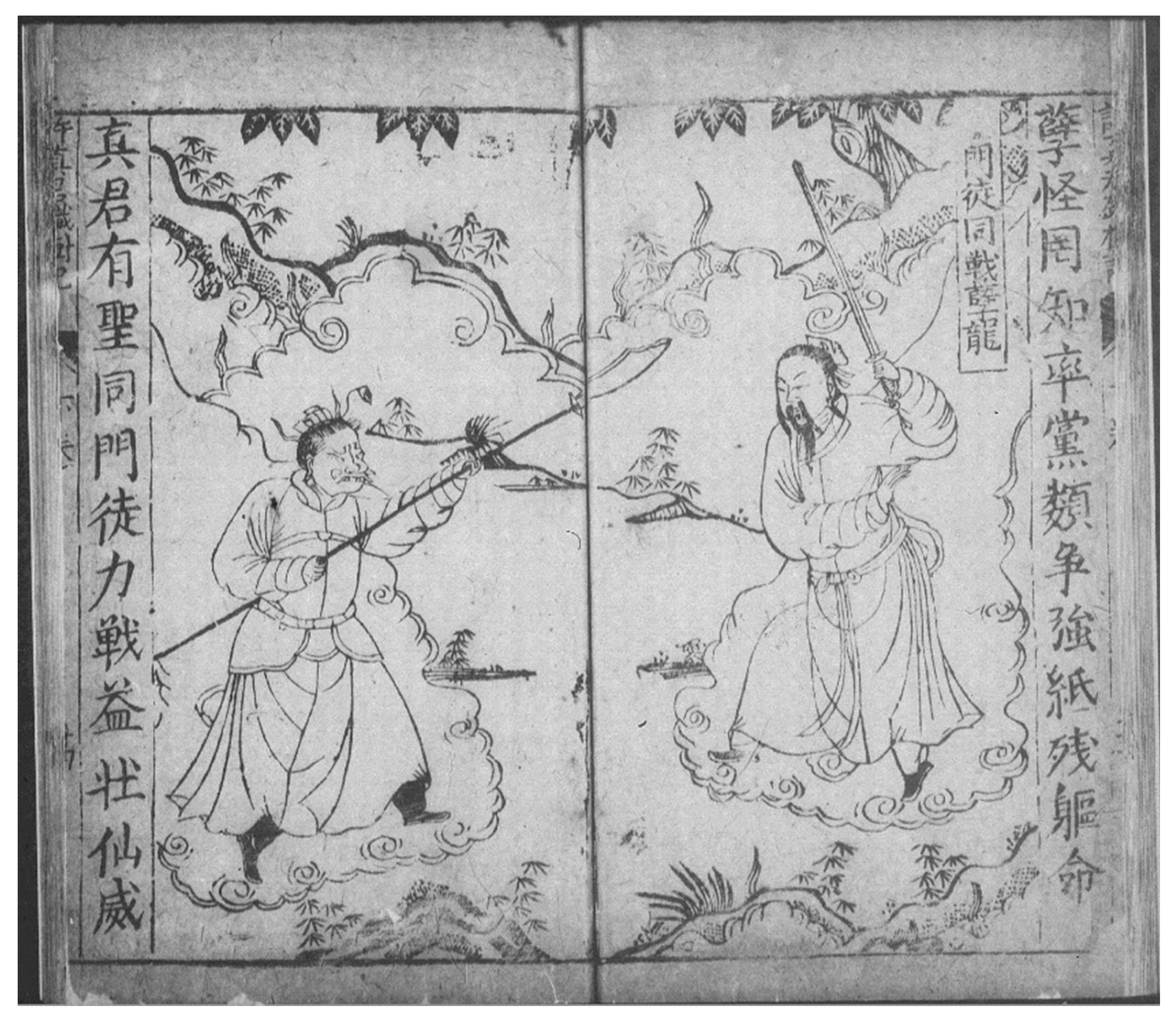

| 9 | Among the pre-existing hagiographic sketches of Sa Shoujian that Deng seems to have drawn upon are found in Zhao Daoyi’s Lishi zhenxian tidao tongjia and Wanli-era editions of Soushenji, such as Xinke chuxiang zengbu soushen ji Daquan 新刻出像增補搜神記大全 and Sanjiao yuanliu shengdi fozu soushen daquan 三教源流聖帝佛祖搜神大全. It is noteworthy that Sa is also celebrated in an anonymous drama that probably dates to early Ming titled Sa zhenren yeduan bitaohua 薩真人夜斷碧桃花, as well as in another drama from the period, now lost, titled Sa zhenren bairi shengtian 薩真人白日升天. |

| 10 | The group known as the Eight Immortals became a recurring theme in storytelling and cultic worship, as well as a staple motif in art, since the Tang Dynasty at the latest. Its members usually include Zhongli Quan 鍾離權, Tieguai Li 鐵拐李, Lü Dongbin 呂洞賓, He Xiangu 何仙姑, Lan Caihe 藍采和, Han Xiangzi 韓湘子, Cao Guojiu 曹國舅, and Zhang Guolao 張果老. On the Eight Immortals as a group, see (Clart 2009; Han 1992; Pu 1936; Wu 2006; Yetts 1916, 1922a, 1922b; Zhu 2014). |

| 11 | Interestingly, altruistic action is central to the immortals’ depiction in contemporaneous, non-“literary” sources as well. For instance, a stele inscription by Chen Wenzhu 陳文燭 (1536–1595), recorded in a Wanli-era Nanchang local gazetteer, argues that Xu Xun became a subject of local worship in recognition for his contribution to mankind, not his celestial status. See “Xu zhenjun miao bei” 許真君廟碑, in the 1588 Xinxiu Nanchang fu zhi 新修南昌府志, juan 28. |

| 12 | This line of narration invokes jātaka stories depicting the virtuous deeds of the Buddha in his previous incarnations (Kleine 1998, p. 328). |

| 13 | Local gazetteers describe the popularity of Xu Xun temples in the Jianyang area and attest to the profound influence of his reverence on the region; see for instance the Jianjing fu zhi 建寧府志, juan 48, p. 2797, and juan 50, p. 3042; Guihua xianzhi 歸化縣志, juan 10, p. 206; Tingzhou fu zhi 汀州府志, juan 3, p. 701, and others. |

| 14 | Regarding Lü Dongbin and the Yellow Crane Tower, see Zhu (2014, pp. 457–58, 481). |

| 15 | See for instance encyclopedic projects and geographical compendia in Wanli-era print culture such as Hainei qiguai 海内奇觀 by Yang Erzeng and Sancai tuhui 三才圖會 by Wang Qi 王圻 and his son Wang Siyi 王思義, among others. |

| 16 | The “Yellow Millet Dream” is not only a mainstay in the Lü Dongbin myth-cycle, but also a recurring trope in Chinese literature and drama, often referred to as “yellow millet” or “life in a pillow” tales. In the Lü Dongbin lore, see for instance the chuanqi play Lü zhenren huangliang mengjing ji 呂真人黃梁夢境記. |

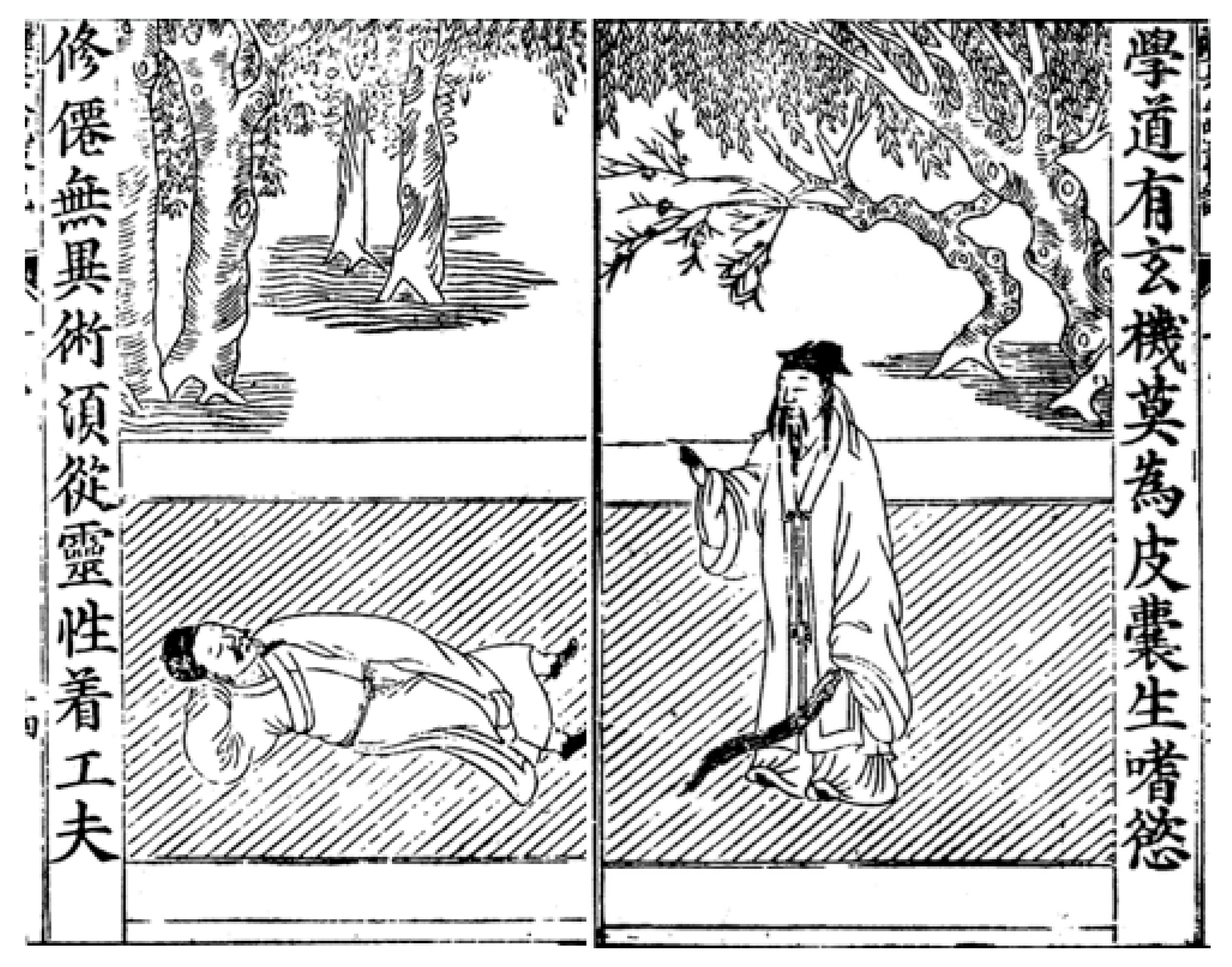

| 17 | Among other instances, Chapter 3 of The Flying Sword quotes numerous lines from the Qiyan 七言, attributed to Lü Dongbin, included in volume 856 of the Quan Tang Shi. Furthermore, in The Iron Tree, Deng modeled the conversations of Xu Xun and Wu Meng after conversations about inner alchemy between Zhongli Quan and Lü Dongbin in the Zhong-Lü chuan dao ji. |

| 18 | The Record of Patriarch Lü (Lüzu zhi 呂祖志) was compiled in the late sixteenth century shortly before the printing of the Continuation of the Daoist Canon (Xu Daozang 續道藏) in which it was included. It remains the largest corpus of texts related to Lü Dongbin in the Daoist canon (regarding poems taken from earlier collections, see Wu 2007, p. 585). |

| 19 | The “green snake” refers to a sword (or rather a dagger) which, according to legend, Lü Dongbin carries inside his sleeve. Song-era sources link this double-edged dagger to medical and exorcistic usages. One legend claims that this sword was originally a huge snake which Lü Dongbin encountered in Yueyang and managed to insert it into his sleeve, transforming it into a dagger (Baldrian-Hussein 1986, pp. 140–42). |

| 20 | See for instance Sandong qunxian lu 三洞群仙錄 (DZ 1248), Yueyang fu tu ji 岳陽府土記, Yuan qu xuan 元曲選, and Quan Tang shi 全唐詩, and the appendix of Tale of the Eight Immortals (Baxian chuchu dongyou ji 八仙出䖏東遊記/Shang dong baxian zhuan上洞八仙傳), among others. |

| 21 | The Yüfu ci also appears in the abovementioned Lüzu zhi and Tale of the Eight Immortals, among other sources. |

| 22 | The dragon and tiger as a metaphor for the duality of yin and yang in inner alchemy is used extensively in the Zhong–Lü school and in the in Wuzhen pian by Zhang Boduan. |

| 23 | The “Leather Bag Song” is also known popularly as the “Dharma Master’s Song of the Leather Bag”, Damo dashi pinang ge 達摩大師皮囊歌. |

| 24 | Bai Yuchan’s hagiography, which ties Xu Xun to Jingming or Filial Daoism and especially its politically oriented zhongxiao 忠孝 strain, was a particularly important source for Deng’s understanding of Xu Xun’s role as the patriarch in Jingming Daoism. Explicit references to Xu Xun’s filiality are scant before the Ming. The Taiping Yulan 太平御覽 (984) quotes the lost text Xu Xun biezhuan 許遜別傳 which portrays Xu Xun’s devotion to his family after the death of his father, despite the cruel treatment he suffered from his mother and sister-in-law, whereas another entry from Taiping Yulan, quoting the Youming lu 幽明録, narrates an encounter between Xu Xun and the ghost of his deceased father, who appealed to Xu Xun’s filial duty (xiaoti 孝悌) to ensure a proper burial. See Taiping Yulan, juan 424: 65, p. 2604 and juan 519: 9, p. 3139. |

| 25 | Bai Yuchan 白玉蟾, “Jingyang Xu zhenjun zhuan” 旌陽許真君傳 in Bai (2013, pp. 61–72) and Bai (1969, vol. 3, pp. 1013–40). Interestingly, the anthology of Bai Yuchan’s writings is titled Yulong ji 玉隆集 (preserved in the anonymously compiled Xiuzhen shishu 修真十書), alluding to Xu Xun’s cult center, the Yulong gong—the name that Emperor Song Zhenzong bestowed on Xu Xun’s shrine. Bai Yuchan dedicated three essays to his visits to Xishan and the Yulong gong: “Longsha xian hui ge ji: Yulong gong” 龍沙仙會閣記: 玉隆宮, “Yulong wanshou gong Yunhui tang ji” 玉隆萬壽宮雲會堂記, and “Yulong wanshou gong Dao yuan ji” 玉隆萬壽宮道院記. Regarding Bai Yuchan’s life and writing, see (Liu 2012; Skar 2008, pp. 203–6). |

| 26 | The full title of this text reads The Record of the Eighty-Five Transformations of the Perfected Lord Xu of West Mountain (Xishan Xu zhenjun bashiwu hua lu 西山許真君八十五化錄, preface dates 1246). It is attributed to Shi Cen 施岑, a prominent disciple of Xu Xun and a member of the group known as the Twelve Perfected (十二真君). |

| 27 | Hagiographies of Langong and Chenmu also circulated independently from the Xu Xun cycle as early as the Tang Dynasty; a hagiography of Chenmu is included in Du Guangting’s Yongcheng jixian lu 墉城集仙錄 and a hagiography of Langong is included in the Taiping guangji 太平廣記, for instance. |

| 28 | See for instance its inclusion in Bai Yuchan’s Jingyang Xu zhenjun zhuan and the album Zhenxian shiji, among other sources. The use of iron for the construction of Xu Xun’s iron tree is rooted in popular practices relating to the subjugation of water-related threats by placing iron pillars or iron oxen near lakes and waterways, in accordance with the theory of the Five Phases. This scene of subjugation also brings to mind the legend of Yu suppressing the god of the Huai and Guo rivers, Wuzhiqi 無支祁, by chaining him to the base of Turtle Mountain 龜山 (see Andersen 2001), as well as the imprisonment of Sun Wukong under the Five Elements Mountain in Journey to the West. |

References

Archival Sources

List of texts from the Daoist Canon (Daozang 道藏, abbreviated as DZ)DZ 263 Zhong-Lü chuan dao ji 鐘呂傳道集DZ 296 Lishi zhenxian tidao tongjian 歷世真仙體道通鑑 by Zhao Daoyi 赵道一DZ 305 Chunyang dijun shenhua miaotong ji 純陽帝君神化妙通紀 by Miao Shanshi 苗善時DZ 440 Xu taishi zhenjun tuzhuan 許太史真君圖傳DZ 448 Xishan Xu zhenjun bashiwu hua lu 西山許真君八十五化錄DZ 449 Xiaodao Wu Xu er zhenjun zhuan 孝道吴許二真君傳DZ 1026 Tianyin zi 天隠子DZ 1103 Jingming dongshen shangpin jing 淨明洞神上品經DZ 1110 Jingming zhongxiao quanshu 净明忠孝全書DZ 1248 Sandong qunxian lu 三洞群仙錄Secondary Sources

- Akizuki, Kanei 秋月観暎. 1978. Chugoku kinsei Dōkyō no keisei: Jōmyōd ō no kisoteki kenkyu 中國近世道教の形成: 浄明道の基礎的研究 [The Formation of Modern Daoism: A Study of the Roots of Jingming Daoism]. Tokyo: Sobunsha. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, Poul. 2001. The Demon Chained under Turtle Mountain: The History and Mythology of the Chinese River Spirit Wuzhiqi. Berlin: Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, Isabelle. 1993. Le Culte de Lu ō Dongbin des Origines Jusqu’au Début du XIVe Siècle: Caractéristiques et transformations d’un Saint Immortel dans la Chine pré-moderne [The Cult of Lü Dongbin, from Its Inception until the Fourteenth Century: Characteristics and Transformations of an Immortal-Saint in Premodern China]. Ph.D. dissertation, l’Université Paris VII, études de l’Extrême-Orient, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, Isabelle. 1997. Le Culte de Lü Dongbin sous les Song du Sud [The cult of Lü Dongbin during the Southern Song]. Journal Asiatique 285: 473–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, Isabelle. 2016. Le palais des Dix Mille Longévités et de la Bienfaisance de Jade à Xishan au Jiangxi: De l’origine d’un tissu économique et cultuel et de son expansion au Sichuan sous les Qing jusqu’au XVIIIe siècle [The palace of ten thousand longevities and jade beneficence at Xishan in Jiangxi: From its origins, economic and cultural fabric, and its expansion to Sichuan during the Qing until the eighteenth century]. Études Chinoises XXXV-1: 197–240. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Yuchan 白玉蟾. 1969. Bai Yuchan quanji 白玉蟾全集 [Complete Writings of Bai Yuchan]. Taipei: Ziyou chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Yiwen 白以文. 2005. Wanming xian chuan xiaoshuo zhi yanjiu 晚明仙傳小說之研究 [Study of Late-MING Hagiographic Narratives of Immortals]. Taipei: Guoli Zhengzhi Daxue Zhongguo Wenxue Yanjiusuo. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Yuchan 白玉蟾. 2013. Bai Yuchan Quan Ji: Daojiao Nanzong Bai Yuchan Zhenren Xiulian Dianji 白玉蟾全集: 道教南宗白玉蟾真人修炼典籍 [Complete Writings of Bai Yuchan: Cultivation Records by the Perfected Bai Yuchan of the Southern Daoist Branch]. Beijing: Zongjiao Wenhua Chuban She. [Google Scholar]

- Baldrian-Hussein, Farzeen. 1986. Lü Tung-pin in Northern Sung Literature. Cahiers d’Extrême-Asie 2: 133–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantly, Francisca Cho. 1989. Buddhist Allegory in the Journey to the West. The Journal of Asian Studies 48: 512–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, Daria. 2003. What the Messenger of Souls Has to Say: New Historicism and the Poetics of Chinese Culture. In Reading East Asian Writing: The Limits of Theory. Edited by Michel Hockx and Ivo Smits. London and New York: Routledge-Curzon, pp. 171–203. [Google Scholar]

- Bisetto, Barbara. 2012. The Composition of Qing shi (The History of Love) in Late Ming Book Culture. Asiatische Studien/Études Asiatiques 66: 915–42. [Google Scholar]

- Boltz, Judith Magee. 1987. Survey of Taoist Literature: Tenth to Seventeenth Century. Berkeley: Institute of Asian Studies, University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Boltz, Judith Magee. 2004. Reconsidering the Story of Xu Xun, Patriarch of Jingming Dao. Unpublished Conference paper presented at the International Symposium on Chinese Religious Texts. Kyoto, Japan, pp. 191–238. Available online: https://www.pdffiller.com/jsfiller-desk12/?requestHash=740e6ecba27fbf6647ae67b1a96d0f04c88cac4caa817838d06f970e00c5f8d8&projectId=914006886&loader=tips&replace_gtm=false#c66a1479c9bc508626fc924f760de94f (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- Boltz, Judith Magee. 2008. Sa Shoujian. In Encyclopedia of Taoism. Edited by Fabrizio Pregadio. London: Routledge, pp. 825–26. [Google Scholar]

- Campany, Robert Ford. 2002. To Live as Long as Heaven and Earth: A Translation and Study of Ge Hong’s Traditions of Divine Transcendents. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cedzich, Angelika-Ursula. 1995. The Cult of Wu-t’ung/Wu-hsien in History and Fiction: The religious roots of the Journey to the South. In Ritual and Scripture in Chinese Popular Religion: Five Studies. Edited by David Johnson. Berkeley: University of California, pp. 137–218. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Dakang 陈大康. 1993. Tongsu xiaoshuo de lishi guiji 通俗小说的历史轨迹 [A History of Popular Fiction]. Changsha: Hunan Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Xudong 陈旭东. 2012. Deng Zhimo zhishu zhijian lu 邓志谟著述知见录 [Guide for the Writings of Deng Zhimo]. Fujian Shiyuan Daxue Xuebao 4: 132–39. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Xi 陈曦, and Zhongjing Wang 王忠敬. 2014. Song Ming difangzhi yu Nanchang diqu Xu Xun Xinyang de bianqian 宋明地方志与南昌地区许逊信仰的变迁 [Song-Ming Local Gazetteers and the Development of Xu Xun Reverence in the Nanchang Region]. Wuhan Daxue Xuebao 67: 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Lili 陈立立, and Fushui Zou 邹付水. 2009. Jingming Zongjiao Lu 净明宗教录 [Book of Jingming teachings]. Nanchang: Jiangxi Renmin Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Chia, Lucille. 2002. Printing for Profit: The Commercial Publishers of Jiangyang, Fujian (11th–17th Centuries). Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center for Harvard-Yenching Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Clart, Philip. 2009. The Eight immortals between Daoism and Popular Religion: Evidence from a New Spirit-Written Scripture. In Foundations of Daoist Ritual: A Berlin Symposium. Edited by Florian C. Reiter. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

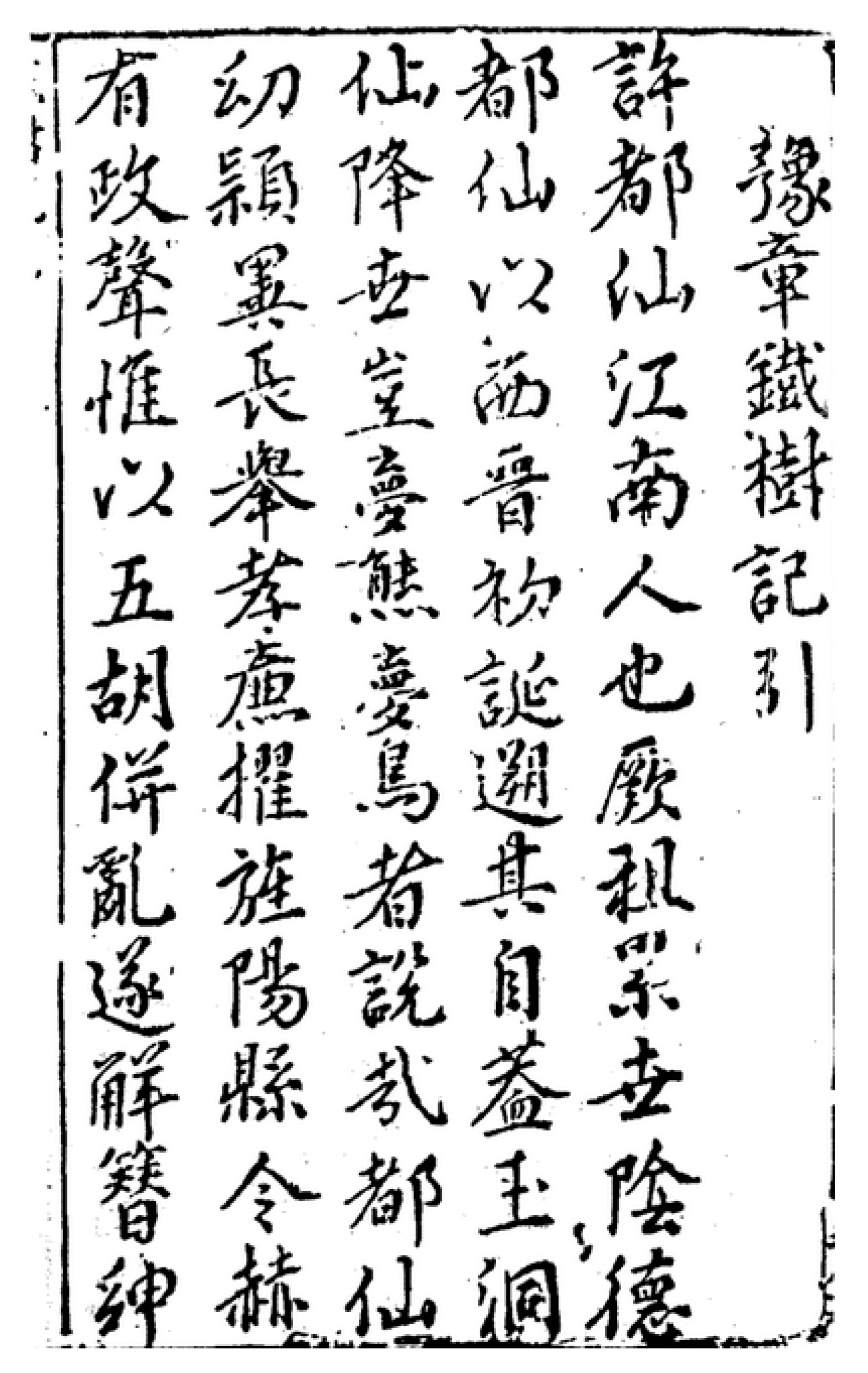

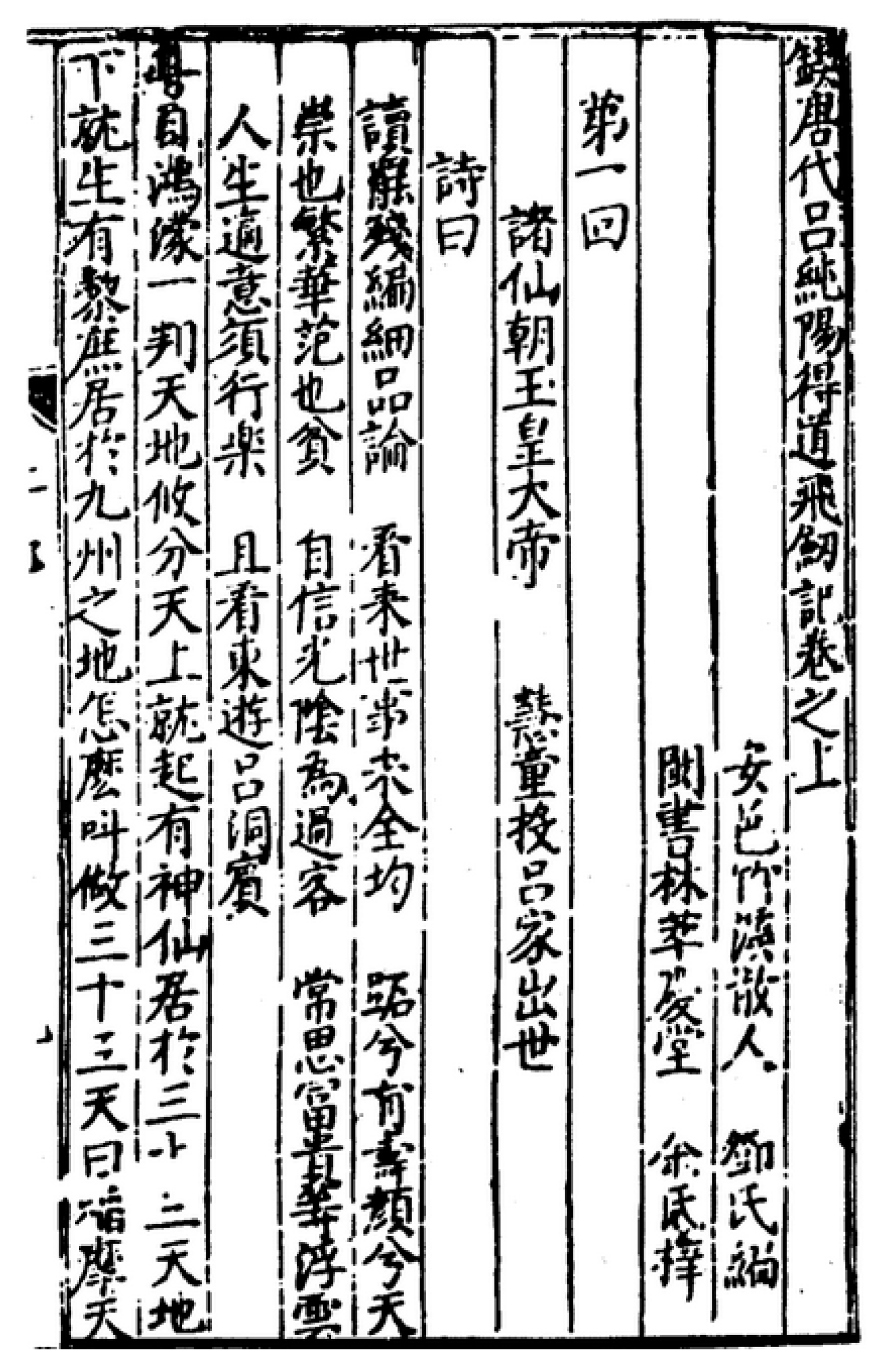

- Deng, Zhimo 鄧志謨. 1603a. Jindai Xu Jingyang dedao qinjiao tieshu ji 晉代許旌陽得道擒蛟鐡樹記 [Tale of the Iron Tree of Jin-era Xu of Jingyang Attaining the Dao and Capturing the Dragon]. Reprint in Guben Xiaoshuo Congkan. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. Jianyang: Cuiqing Tang, vol. 10, p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Zhimo 鄧志謨. 1603b. Wudai Sa zhenren dedao Zhouzao ji 五代薩真人得道咒棗記 [The Story of the Perfected Sa of the Five Dynasties Attaining the Dao, the Enchanted Date]. Reprint in Guben Xiaoshuo Congkan. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, vol. 10, p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Zhimo 鄧志謨. n.d. Tangdai Lü Chunyang dedao Feijian ji 唐代呂純陽得道飛劍記 [The Story of Lü Chunyang Attaining the Dao, the Flying Sword]. Reprint in Guben Xiaoshuo Congkan. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, vol. 10, p. 5, Reprint in Guben Xiaoshuo Congkan.

- Durand-Dastès, Vincent. 2013. Late Qing Blossoming of the Seven Lotus: Hagiographic novels about the Qizhen. In Quanzhen Daoists in Chinese Society and Culture, 1500–2010. Edited by Liu Xun and Vincent Goossaert. Berkeley: Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California at Berkeley, pp. 78–112. [Google Scholar]

- Durand-Dastès, Vincent. 2016. Rencontres hérétiques dans les monastères de Kaifeng: Le bouddhisme tantrique vu par le roman en langue vulgaire des Ming et des Qing [Heretical encounters in the monasteries of Kaifeng: Tantric Buddhism as seen in vernacular novels of the Ming and Qing]. In Empreintes du Tantrisme en Chine et en Asie Orientale: Imaginaires, Rituels, Influences. Edited by Vincent Durand-Dastès. Leuven: Peeters, Mélanges chinois et bouddhiques, vol. 32, pp. 27–62. [Google Scholar]

- Eskildsen, Stephen Edward. 1989. The Beliefs and Practices of Early Chuan-Chen Taoism. Master’s thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Eskildsen, Stephen Edward. 2008. Do Immortals Kill?: The Controversy Surrounding Lü Dongbin. Journal of Daoist Studies 1: 28–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Zhiming 范致明. 1104. Yueyang Fengtu Ji 岳陽風土記. Beijing: Airusheng Shuzi Hua Jishu Yanjiu Zhongxin. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, Siyen. 2010. Ways of Looking: The creation and social use of urban guidebooks in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century China. Urban History 37: 226–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganany, Noga. 2018. Origin Narratives: Reading and Reverence in Late-Ming China. Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ganany, Noga. 2021. Journeys Through the Netherworld in Late-Ming Hagiographic Narratives. Late Imperial China 42: 137–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goossaert, Vincent. 2021. Vie des Saints Exorcistes: Hagiographies taoïstes XI-XVIe siècles [Lives of Exorcistic Saints: Daoist Hagiographies, Eleventh to Sixteenth Centuries]. Paris: Les Belles Lettres. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Wu 郭武. 2005. Jingming zhongxiao quanshu yanjiu: Yi Song, Yuan shehui wei beijing de kaocha 净明忠孝全书研究: 以宋元社会为背景的考察 [A Study of the Jingming Zhongxiao Quanshu: Examination of Its Social Context in the Song and Yuan]. Beijing: Zhongguo Shehui Kexue Chuban She. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Xiduo 韩锡铎. 1992. Baxian xilie xiaoshuo 八仙系列小说 [Novels of the Eight Immortals]. Shenyang: Liaoning Jiaoyu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Hanan, Patrick. 1981. The Chinese Vernacular Story. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hegel, Robert E. 1977. Sui-Tang yen-i and the Aesthetics of the Seventeenth-Century Suchou Elite. In Chinese Narrative: Critical and Theoretical Essays. Edited by Andrew H. Plaks. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 124–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hegel, Robert E. 1981. The Novel in Seventeenth Century China. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Zhigang 黄芝崗. 1973. Zhongguo de shuishen 中國的水神 [Water Deities of China]. Taipei: Dongfang Wenhua Shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, Andrew. 2015. Wordless Texts, Empty Hands: The Metaphysics and Materiality of Scriptures in Journey to the West. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 75: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idema, Wilt L. 1974. Chinese Vernacular Fiction: The Formative Period. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Ju-yu, Scarlett Jang. 1997. Form, Content, and Audience: A Common Theme in Painting and Woodblock-Printed Books of the Ming Dynasty. Ars Orientalis 27: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Paul R. 1999. Images of the Immortal: The Cult of Lu Dongbin at the Palace of Eternal Joy. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kleine, Christoph. 1998. Portraits of Pious Women in East Asian Buddhist Hagiography: A Study of Accounts of Women Who Attained Birth in Amida’s Pure Land. Bulletin de l’Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient 85: 325–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Dorothy. 1994. Teachers of the Inner Chambers: Women and Culture in Seventeenth-Century China. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Fengmao 李豐楙. 1993. Deng Zhimo Daojiao xiaohuo de zhexian jiegou—jianlun zhongguo chuantong xiaoshuo de shenhua jiegou 鄧志謨道教小說的謫仙結構—兼論中國傳統小說的神話結構 [The banished-immortal structure of Deng Zhimo’s Daoist narratives: Discussion of the mythical structure of Chinese traditional narratives]. Xiaoshuo Xiqu Yanjiu 4: 60–78. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Fengmao 李豐楙. 1997. Xu Xun yu Sa Shoujian: Deng Zhimo daojiao xiaoshuo yanjiu 許遜與薩守堅: 鄧志謨道敎小說硏究 [Xu Xun and Sa Shoujian: A Study of Deng Zhimo’s Daoist Novels]. Taipei: Guojiao Tushuguan Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Fengmao 李豐楙. 2003. Chushen yu xiuxing: Mingdai xiaoshuo shang fan xushu moshi de xingcheng jiqi zongjiao yishi 出身與修行: 明代小說謪凡敘述模式的形成及其宗教意識 [Origin Stories and Self-Cultivation: The Narrative Mode of the Descending-to-Earth fiction In Late Ming and Its Religious Significances]. Guowen Xuezhi 7: 85–113. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Qiancheng, and Robert Hegel, trans. 2020. Further Adventures on the Journey to the West. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Cunren 柳存仁. 1985. Xu Xun yu Langong 許逊與蘭公 [Xu Xun and Langong]. Shijie Zongjiao Yanjiu 3: 40–59. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Liang 刘亮. 2012. Bai Yuchan shengping yu wenxue chuangzuo yanjiu 白玉蟾生平与文学创作研究 [A Study of the Life and Writing of Bai Yuchan]. Nanjing: Feng Huang Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry, Kathryn A. 2003. Duplicating the Strength of Feeling: The Circulation of Qingshu in Late Ming. In Writing and materiality in China: Essays in honor of Patrick Hanan. Edited by Judith T. Zeitlin, Lydia H. Liu and Ellen Widmer. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Asia Center, pp. 239–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry, Kathryn. 2005. The Tapestry of Popular Songs in 16th- and 17th-Century China: Reading, Imitation, and Desire. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Xiaohong 马晓宏. 1989. Lü Dongbin shici kao 吕洞宾诗词考 [A study of Lü Dongbin’s poetry]. Zhongguo Daojiao 1: 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Meulenbeld, Mark. 2007. Civilized Demons: Ming Thunder Gods from Ritual to Literature. Ph.D. dissertation, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Meulenbeld, Mark. 2015. Demonic Warfare: Daoism, Territorial Networks, and the History of a Ming Novel. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, Yonghe 缪咏禾. 2000. Mingdai Chuban Shi Gao 明代出版史稿 [A Historical Sketch of Ming Dynasty Publishing]. Nanjing: Jiangsu Renmin Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Pu, Jiangqing 浦江清. 1936. Baxian kao 八仙考 [A Study of the Eight Immortals]. Tsinghua Xuebao 11: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Schipper, Kristofer. 1985. Taoist Ritual and the Local Cults of the T’ang Dynasty. In Tantric and Taoist Studies in Honour of R.A. Stein. Edited by Michel Strickmann. Brussels: Institut Belge des Hautes Etudes Chinoises, vol. III, pp. 812–34. [Google Scholar]

- Shahar, Meir. 1998. Crazy Ji: Chinese Religion and Popular Literature. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shahar, Meir. 2015. Oedipal God: The Chinese Nezha and His Indian Origins. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, Wei. 2003. Jin Ping Mei and Late Ming Print Culture. In Writing and Materiality in China: Essays in Honor of Patrick Hanan. Edited by Judith Zeitlin, Lydia Liu and Ellen Widmer. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Asia Center, pp. 187–238. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, Wei. 2005. The Making of Everyday World: Jin Ping Mei cihua and encyclopedias for daily use. In Dynastic Crisis and Cultural Innovation from the Late Ming to the Late Qing and Beyond. Edited by David Der Wei Wang and Wei Shang. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Asia Center, pp. 63–92. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, Wei. 2014. Writing and Speech: Rethinking the Issue of Vernaculars in Early Modern China. In Rethinking East Asian Languages, Literacies, and Vernaculars: 1000–1919. Edited by Benjamin Elman. Leiden: Brill, pp. 254–301. [Google Scholar]

- Skar, Lowell. 2008. Bai Yuchan. In Encyclopedia of Taoism. Edited by Fabrizio Pregadio. London: Routledge, pp. 203–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Kaidi 孙楷第. 1933. Zhongguo tongsu xiaoshuo shumu 中国通俗小說書目 [Bibliography of Chinese Popular Fiction]. Beijing: Guo li Beiping Tu Shu Guan. [Google Scholar]

- Teiser, Stephen. 1986. Ghosts and Ancestors in Medieval Chinese Religion: The Yü-lan-p’en Festival as Mortuary Ritual. History of Religions 26: 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Eugene Y. 2003. Tope and Topos: The Leifeng Pagoda and the Discourse of the Demonic. In Writing and Materiality in China: Essays in Honor of Patrick Hanan. Edited by Judith Zeitlin, Lydia Liu and Ellen Widmer. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Asia Center, pp. 488–535. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Richard Gang. 2012. The Ming Prince and Daoism: Institutional Patronage of an Elite. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Guangzheng 吴关正. 2006. Baxian Gushi Xitong Kaolun 八仙故事系统考论. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Guangzheng 吴关正. 2007. Buddhist-Taoist rivalry and the evolution of the story of Lü Dongbin’s slaying the Yellow Dragon with a flying sword. Frontiers of Literary Studies in China 1: 581–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Wei 熊威. 2016. Sa Shoujian xingxiang jiangou yanjiu 萨守坚形象建构研究 [A study of the development of the figure of Sa Shoujian]. Zongjiao Xue Yanjiu 2: 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Wei 許蔚. 2011. Jingming Dao zushi tuxiang yanjiu: Yi “Xutaishi zhenjun tuzhuan” wei zhongxin 淨明道祖師圖像研究 —以《許太史真君圖傳》為中心 [A study of the iconography of Jingming patriarchs, focusing on the pictorial hagiography of the Perfected Xu]. Hanxue Yanjiu 29: 119–52. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Erzeng. 2007. The Story of Han Xiangzi: The Alchemical Adventures of a Daoist Immortal. Translated and Introduced by Philip Clart. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Mingsheng 葉明生, and John Lagerwey 勞格文. 2007. Fujian sheng Jianyang Shi Lüshan Pai Keyi Ben 福建省建陽市閭山派科儀本 [The Origins of the Ritual Practices of the Lüshan Sect in Jianyang, Fujian Province]. Taipei: Xinwen Feng Chuban Gongsi. [Google Scholar]

- Yetts, Perceval. 1916. The Eight Immortals. Journal of Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 48: 773–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetts, Perceval. 1922a. More Notes on the Eight Immortals. Journal of Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 3: 397–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetts, Perceval. 1922b. Pictures of a Chinese Immortal. The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 39: 113–21. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Huoqing 張火慶. 2006. Gudian xiaoshuo de renwu xingxiang 古典小說的人物形象 [The Conceptualization of Protagonists in Classic Fiction]. Taipei: Li Ren. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Yueli 朱越利. 2014. Daozang Kao Xin Ji 道藏考信集 [Collection of Studies of the Daoist Canon]. Jinan: Qilu Shushe. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ganany, N. Writing and Worship in Deng Zhimo’s Saints Trilogy. Religions 2022, 13, 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13020128

Ganany N. Writing and Worship in Deng Zhimo’s Saints Trilogy. Religions. 2022; 13(2):128. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13020128

Chicago/Turabian StyleGanany, Noga. 2022. "Writing and Worship in Deng Zhimo’s Saints Trilogy" Religions 13, no. 2: 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13020128

APA StyleGanany, N. (2022). Writing and Worship in Deng Zhimo’s Saints Trilogy. Religions, 13(2), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13020128