Abstract

Objective: Tolerance is considered one of the most important values in any society. The present study aimed to validate the Tolerance Index on the Saudi society. Method: A 2019 Tolerance Index (56 items) by the King Abdulaziz Center for National Dialogue was used. A total of 1071 participants completed the survey. The sample was randomly selected using geographical sampling. The Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was used to validate the Tolerance Index. Result: The principal components analysis, along with the orthogonal rotation matrix (Varimax rotation) revealed that 35 items of the Tolerance Index were loaded on six main factors: twelve items were loaded onto two social and cultural factors; eight items were loaded onto two economic factors; four items were loaded onto one political factor; and 11 items were loaded onto one religious factor. Conclusion: The Tolerance Index is valid and is a reliable index that can be used in the Saudi society.

1. Introduction

Tolerance is a noble human value, a civilized behavior, and a means to achieving peaceful coexistence, social solidarity, coherence, and binding. This is especially true in societies with a wide variety of religious and cultural beliefs. To achieve this goal, people must respect and accept one another without discrimination; they must abhor all forms of discrimination, separation, or hatred (Al-Jumaili 2021). Generally, religion promotes love, forgiveness, understanding, and coherence among people (Streeter 2021; Friedmann 2003). Tolerance produced more human laws, and imposed new ways of thinking and brainstorming on nations in order to draw mankind away from violence and fanatism (Harris and Nawaz 2015; Hassan 2009).

Recently, tolerance has been attracting a lot of interest in the field of social sciences in general. Anyone interested in the history of tolerance will discover that it began as a theological dispute in the Middle Ages (the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries), evolved into a legal position, and eventually reached a point of stability. Throughout history, nations and civilizations have debated and argued about tolerance, making it a culturally contentious subject matter (Albraithen 2019).

The implementation of tolerance’s core principles—respect, appreciation, and acceptance of differences—stands out as the most significant aspect of Islamic history. This occurred when the Prophet Muhammad signed the Medina Document between the Muhajireen and the Ansar in the year 623. In it, he claimed the Jews of Medina, made a covenant with them, and approved of them regarding their religion and their wealth. The document also included an organisation of Medina’s social life, specifically the relationship between the people of Medina, Muslims, and non-Muslims (Salem 2003). Muslim scholars and thinkers took part in enriching the scientific and intellectual product of tolerance through their writings and theorizing. One such example is Al-Mawardi (1986), who addressed the moral aspect of tolerance; linking the virtue of tolerance with virtue (Harris and Nawaz 2015; Rizqiany 2017). In the sixteenth century and later, Europe realized that tolerance is a human virtue. Grace, in this regard, is due to some thinkers such as: Voltaire, Montesquieu, John Locke, etc. Their efforts helped to spread the message of tolerance. This was particularly the case with the tolerance philosopher, Voltaire, who “calls up Christians to make all people brothers, despite differences in the creed” (Tender 2013; Bödeker et al. 2008; Kwasnicki 2021). Philosophers in modern times have focused on the term “tolerance”, which arose as a result of the Religious Reform Movement in Europe in the 16th and the 17th centuries in response to the lack of tolerance within religious systems—particularly the Church towards its Christian opponents (Pratt 2002).

The UN indicated that “three-quarters of the world’s major conflicts have a cultural dimension”. Bridging the gap between cultures is urgent and necessary for peace, stability, and development (UN 2022). Spreading the culture of tolerance is a demanding cause embraced by modern societies. It is a measure of social progress. Tolerance being widespread among community members reflects the ability of a community to spread peace, love, fraternity, equality, justice, and the acceptance of differing views (Al-Jumaili 2021). Nations and governments seek to adopt necessary mechanisms for establishing tolerant values in young populations and to prepare current and future generations for cooperation and participation in development, peace, and social security (Hassan and Shalaby 2019). Spreading a culture of tolerance has emerged as a moral and human necessity in contemporary reality as a result of the emergence of violence and the breakdown of social relationships at all levels after everyone—adults and children—has become either victims or criminals. This is attributed to the prevalence of the language of violence in reality and the absence of religious/moral values and ideals, which puts the contemporary layman at a crossroads in dealing with one another, with whom they might be totally in agreement on ideology (Hegazi 2022).

Provisions stated in international constitutions and charters, such as the 1995 Declaration of Principles adopted by UNESCO, are among contemporary contributions that prohibit racial discrimination practices and support human tolerance as a global end. This declaration calls for international tolerance and considers the 16th of November as International Tolerance Day. Such implementation resulted in linking the concept of tolerance to pluralism, democracy, and peace. It also took part in separating the concept from its religious origins, thus transcending being a religious duty to being a political and legal one, too (Papastephanou 2005; Tender 2013).

Spreading the culture of tolerance and social security is a fact that cannot be subject to negotiation or negligence. It is not the responsibility of a specific authority. Rather, it is everyone’s responsibility to join the joint efforts of individuals, families, groups, institutions, and communities. Thus, different professional disciplines and religious, educational, social, cultural, media, and art authorities should collaborate to reinforce the culture of tolerance and establish straight moral values and principles in community members. Wang (2019) stated that variation in the world provided us with the opportunity to live with different people. Such variety not only adds excitement and adventure but also allows us to interact with people whose customs we disagree with. Further, he stated that tolerance is the common sense of people in modern societies. The importance of tolerance stems from one’s freedom to hold on to their beliefs and accepting the freedom of others to hold on to their beliefs; tolerance acknowledges that different people have the right to live in peace, regardless of their nature, appearance, position, language, behaviors, and values (Harris and Nawaz 2015). The bold heading “social rise” describes the culture of tolerance. It is the supreme virtue resulting from the progress of communities, the living evidence of their cultural growth and the establishment of peace, love, justice, and equality; such principles were emphasized by all divine religions (Albrifkani and Al-Obaidi 2020).

Many states and international organizations have made treaties and agreements to support the principle of peaceful coexistence by adopting tolerance as an ideal model for solving various problems of racial, religious, and cultural variety, either directly or by addressing one aspect of achieving tolerance in society. In Geneva’s conference (1964), article 25 of the UN Charter endorsed protecting man’s physical and mental health without discrimination and equally for everyone. In 1948, article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights stated that each person has the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion (Gruber 2015). The General Assembly endorsed the Convention on the Political Rights of Women in 1953, which states that women’s rights to exercise political rights and hold public office are equal to men’s, without any gender discrimination (Al-Fatlawi 2018). In 1995, specifically on November 16th, UNESCO adopted the Declaration of Tolerance Principles in its 28th general conference in Paris. This declaration represents the goal of enhancing tolerance in people. This day has become the International Day of Tolerance (Broglio 1997).

1.1. Tolerance Dimensions

In this context, many studies deal with specific aspects of tolerance. For example, some of them focus on social tolerance, while others focus on religious tolerance, economic tolerance, or political tolerance.

Social tolerance is defined as “reconciliation with oneself; opening, accepting, respecting, and recognizing the rights of others even if they were against the values, directions, and behaviors of the group; and approving others’ rights to exist, be free and express their opinions and thoughts (AL-Geboory 2014, p. 377)”. It also means not to give or research a man’s beliefs. Rather, it is the freedom of a man to stick to what he believes and accept others’ freedom to stick to and accept the reality of men by nature and ethics in shape, position, language, and behavior—as well as their right to live in peace (Aslan 2018). Social and cultural tolerance means recognizing different affiliations and variations among community members according to different formations: tribal, linguistic, religious (Velthuis et al. 2021), or sexual (Chen 2017; Lee 2021), without such affiliations impacting the principle of loyalty to the same homeland and the same state. Social tolerance assumes that there is variation in society, whatever its nature, and that this variation manifests itself in the form of different ideas, opinions, and practices. Tolerance means tolerating and accepting something you do not love for the sake of progress, coexistence, and better harmony with others (Hjerm et al. 2020; Persell et al. 2001).

Economic tolerance is defined as respecting the physical and corporal property of individuals and groups, observing the veneration of public and private properties, maintaining the same, keeping deposits, considering others’ conditions in financial transactions, commercial handling of commodities, services, and utilities among all community groups, as well as preventing monopoly (Berggren and Nilsson 2016). It also means respecting their right to practice legitimate economic activities (García-Castro et al. 2020). Characteristics that make people tolerant also make them accept new ideas (Boudreau and MacKenzie 2018). Although people tend to reject inequality, they also tend to tolerate it and show more tolerance in countries with the biggest share of inequality (Boudreau and MacKenzie 2018).

Albrifkani and Al-Obaidi (2020) define religious tolerance as “averageness, accepting others, non-extremism, or opulence” (p. 1230). Religious tolerance is defined as the coexistence of religions, freedom to practice religious rituals, abandoning religious fanaticism, an intellectual openness towards others who practice different religions and beliefs, and respect for others’ beliefs in religious and mundane aspects (Ghazwan 2021). Hence, religious tolerance focuses on giving everyone the right to believe what they think is right. They must be free to do their rituals as they wish. Followers of different religions must be equal before the state’s law (Rahmat and Yahya 2022; Tasheva 2021). Religious tolerance is not limited to coexistence among different religions—the freedom of each religion’s followers to practice their rituals involves abandoning fanaticism against other religions. It includes accepting differences and variation in understanding the same religion, too (Yazdani 2020; Wijaya Mulya and Aditomo 2019).

Political tolerance means recognizing others, whether minority or majority, and their right to work, organize, and spread their political thoughts such as democracy, freedom, variety, and human rights (Albrifkani and Al-Obaidi 2020) without any oppression or pressure against them (Ghazwan 2021). The more the political culture provides a wide space of political variation, the more it is oriented toward tolerance (Djupe and Neiheisel 2021). In other words, the more one feels politically enfranchised, the more tolerant one tends to be, because such political effectiveness leads to more political participation, which, in turn, contributes to enhancing tolerance (Prati 2021).

1.2. Tolerance and Saudi Arabia

The rise of Islam helped to further shape the culture of the Arabian Peninsula, and King Abdulaziz Al Saud established the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in 1932 after successfully uniting all the many socioeconomic groups under the banner of a single country (Salam 2021). For the remainder of the 20th century, it experienced the swift economic and social change (Al-Bakr et al. 2017). Whereas Saudi Arabia has various types of variety, including tribal, regional, and sectarian (Keshi 2022; Salam 2021), it has a long history and a very old culture. As a result, Saudi citizens take great pride in upholding Islamic and Arab customs (Alomiri 2015). The foundation of the Saudi culture’s legacy is found in its Islamic roots. Saudi society’s culture is based on Islam, culture, tribe, and geography (Saudi Press Agency 2022). According to Saudi Statistics Authority data from 2021, more than 36% of the population of Saudi Arabia is foreign, and more than 17 million Muslims from all sects travel to Mecca and Medina each year to perform the Hajj and Umrah (Saudi Statistics Authority 2021; Arab News 2020). It is critical to consider the various cultural forms that comprise Saudi society because they necessitate an appropriate amount of respect, appreciation, and acceptance of the differences in sect, region, tribal, and national identity. Saudi society has cultural diversity based on the tribe, the region, and the sect. It also has foreigners living there and receives visitors to the holy places of various Muslim sects.

The King Abdulaziz Center for National Dialogue was founded in 2003 and has since hosted national dialogue gatherings between people of all intellectual persuasions, including those who hold religious beliefs in all of their varieties and those who hold other viewpoints. The purpose of these meetings was to discuss national issues, and one of the topics covered there was the meeting “between us and the other”, which covered topics like how a Saudi citizen deals with people who are different from them, women’s issues, and many other delicate topics at the time. For ten years, this centre held these kinds of national meetings, debating a wide range of topics and delivering the outcomes to the king. Many of the proposals made in those outputs were put into action. Elites and intellectuals were the target audience for these events. Since 2015, the centre has developed social indicators and metrics for a number of subjects it cares about, including tolerance and national cohesion, coexisting, and safeguarding the social fabric, with an emphasis on individuals rather than elites. To empower the citizens of regions, governorates, and villages, KACND has been training a large number of trainers on dialogue skills in all fields. Hosting regular conversation gatherings where young people can discuss their problems, the centre also looks after them. Additionally, there is interest in conducting public opinion polls of Saudi society members on a variety of social concerns. It runs campaigns and initiatives aimed at teachers and students to spread the values of tolerance. As a result, this institution did an excellent job of defining several broad parameters on delicate subjects, including women, which helped foster the acceptance of the openness that we are currently witnessing since the commencement of work on the ambitious Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Vision 2030 (KACND 2022).

The Kingdom’s Vision 2030 will have several implications about respecting and appreciating differences and diversity, which underlies the concept of tolerance and emphasizing the link between respect for diversity and advancing the wheel of economic development and adherence to the laws of the country and respect for its customs and traditions. Many programs, projects, and initiatives launched by the vision are in the fields of tourism, entertainment, and others to emphasize that cultural diversity is the main driver of sustainable development for individuals and local communities (Saudi Vision 2030 2017).

Therefore, developing a comprehensive vision to achieve sustainable development in the Kingdom requires respecting cultural diversity in the present and future. About the most prominent implications in this context, the vision states, “To achieve the desired economic growth rate at a faster pace, we seek to create an attractive environment for the required competencies by facilitating living and working in our country and around the world, providing all the needs in a way that contributes to advancing development and attracting more investments (Saudi Vision 2030 2017, p. 37).” Many national transformation programs focus on activities and initiatives that promote the values of tolerance.

Finally, the National Transformation Program (NTP) introduced a Human Capability Development Program (HCDP), which included the strategic objective of promoting the values of tolerance, with a baseline and targets for the coming years. This in turn gives clear indications of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s intention to promote the values of respecting and appreciating difference and accepting diversity at the local and international levels, whether this diversity is social, cultural, economic, or religious (Saudi Vision 2030 2017; NTP 2022; HCDP 2022).

1.3. Tolerance Measurement

We find that the social tolerance index and some other studies have not addressed the sect of the same religion, nor does it address diversity according to the region, nor diversity according to the tribe; this is what the context means. It is useful to build measures that contribute to understanding tolerance according to the local context that the study was conducted in (Bangwayo-Skeete and Zikhali 2011; Das et al. 2008; Zanakis et al. 2016; Haerpfer et al. 2020).

Turkish researchers created a scale of tolerance among university students in a study that attempted to indicate the degree of tolerance in different contexts. The results of this measure were 11 items that measure tolerance with a sufficient level of validity and reliability (ERSANLI 2014). Another study revealed the growth of a measure of religious tolerance among young people in Pakistan, and another study revealed the development of a measure of tolerance among university students in Iran (Ersanli and Mameghani 2016; Batool and Akram 2020). A study on social cohabitation was carried out in Saudi Arabia by the King Abdulaziz Center, which resulted in the development of a scale with good validity and reliability (KACND 2017). Therefore, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no research has focused on creating a comprehensive index of tolerance that takes into account the following dimensions: the social and cultural dimension, the economic dimension, the religious dimension, and the political dimension, particularly in the Saudi context.

In this study, we seek to create indicators to aid academics, decision-makers, and policymakers in understanding Saudi society’s tolerance.

2. Results

Applying KMO and Bartlett’s tests to the measures of the study, a set of findings are concluded and shown in Table 1. The KMO value of the Tolerance Index is (0.932); it is higher than the unacceptable limit (less than 0.50) and more than the desired limit in the social sciences (0.70). This indicates the adequacy of the sample size used in the study.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics.

Findings shown in Table 2 state that the degree of statistical significance of Bartlett’s Test of measures is (<0.001) that is less than (0.05), showing a statistically significant correlation between all the variables sufficient for applying the factor analysis.

Table 2.

Bartlett’s Test of measures.

According to the results of the two previous tests, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was applied to check the measure validity. EFA was used by analyzing the principal components analysis by Hotelling along with using the orthogonal rotation matrix according to Kaiser’s varimax rotation to hypothesize the independence of factors. This method was used in many previous studies to provide the convenient classification of variables and retest the measure and check it.

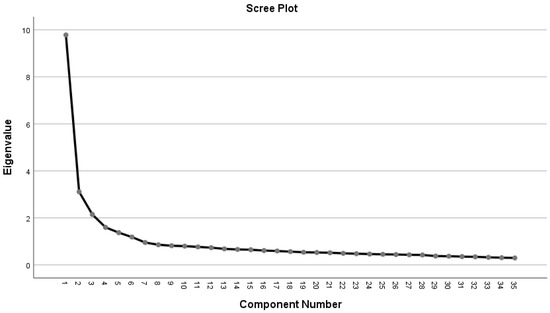

This study utilized the following criteria in order to define the extracted factors: (A) the Kaiser criterion, which is considered one of the most commonly used criteria which depends on the Eigenvalue being 1 or more,(B) the criterion proposed by Hair et al. (2010) of item factor loadings that is 0.50 or more on the condition that no loadings should be designed on more than one factor significantly, and (C) keeping factor loadings of at least three basic items.

EFA was applied to items related to the Tolerance Index (67 items). Primary findings yielded 10 factors or components with Eigenvalues of 1 or more. By examining item factor loadings, findings indicated that there are 17 items that did not get factor-loaded, therefore, they were deleted from the scale and EFA was re-applied.

Further stages of EFA were applied to the remaining items after deleting and ignoring items that were not factor-loaded significantly at (0.50)-0.50 —or those items which were loaded on one factor simultaneously; 35 items were intrinsically loaded on 6 factors.

As expected, using EFA—the principal components analysis along with the orthogonal rotation matrix (Varimax rotation) revealed that 35 items of the Tolerance Index were loaded on six main factors. The Eigenvalue of each item was more than 1. The total explained variance was 54.8% out of the total variance of the factor matrix, a value that exceeds the required limit (50%). Examining the coefficients of factor loadings of the different items after rotation, it is found that all items are of factor loading at 0.50 or more—it is a criterion value for this study.

Figure 1 Scheme of latent roots of the constituent factors of the tolerance index.

Figure 1.

Shows the diagram of Eigenvalues of Tolerance Index factors.

Table 3 outlines the factor matrix and items loaded by the six main extracted factors in addition to the Eigenvalues; the total explained variance and communalities of the scale items.

Table 3.

Shows an outline of Eigenvalues of Tolerance Index factors.

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn. The six main extracted factors are as follows:

The First Factor is the religious dimension that includes 11 items. Loading coefficients of each item were 0.50 or more. Furthermore, no item was loaded on more than one factor simultaneously. Such items focus on respecting and accepting the other’s religious groups, so this factor is called the religious factor. The Eigenvalue of this factor was (9.78), which participated in explaining 27.94% of variance; evidence to the strength of this factor can be found within the components of the Tolerance Index.

The second factor is the socio-cultural dimension (coexistence, integration, consolidation, and cohesion) that consists of eight items. Loading coefficients of each item were 0.50 or more. Furthermore, there was no item loaded on more than one factor simultaneously. Most of the items are related to coexistence, integration, consolidation and cohesion, thus it is so called. The Eigenvalue of this factor was 3.11, which played a role in explaining 8.88% of variance.

The third factor is the economic dimension (maintaining the money and property of others). It includes five items. Loading coefficients of each item were 0.50 or more. Furthermore, there was no item loaded significantly on more than one factor simultaneously. The dimension items focus on responsibility towards maintaining others’ money, keeping their property, and rationalizing the use of their possessions. That is why this is called the factor of maintaining money and property of others. The Eigenvalue of this factor was 2.146 that played a role in explaining 6.31% of variance.

The fourth factor is the political dimension— it consists of four items. Loading coefficients of each item were 0.50 or more. Furthermore, there was no item loaded significantly on more than one factor simultaneously. Most items are about acceptance of being criticized by others on one’s own political views, respect to other political points of view, and understanding some countries’ attitudes toward some political issues. That is the reason for this title. Eigenvalue of this factor was 1.59, which played a role in explaining 4.56% of variance.

The fifth factor is the also a social-cultural dimension (avoiding prejudice). It includes four items. Loading coefficients of each item were 0.50 or more. Further, there was no item loaded significantly on more than one factor simultaneously. Most items are related to supporting women and accepting others, so it is titled avoiding bias. The Eigenvalue of this factor was 1.37, which played a role in explaining 3.92% of variance.

The sixth factor is the economic dimension (economic exchange). It covers three items. Loading coefficients of each item were 0.50 or more. There was no item loaded significantly on more than one factor simultaneously. Most items are about accepting partnership and working with others, appreciating good products regardless of the producer’s identity, and accepting trading (purchase and selling) irrespective of the other party. That is the reason for this title. The Eigenvalue of this factor was 1.18, which played a role in explaining 3.39% of variance.

Thus, the findings of EFA of the Tolerance Index indicated that 35 fundamental items were loaded on 6 main factors matching with the hypothesized 6 factors of the scale.

3. Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to develop a tolerance index for the measurement of tolerant values in Saudi society. This study used exploratory factor analysis to examine the factors’ structure and to determine the construct’s validity. To date, there is no index to measure tolerant values in Saudi society. In this index, several scales were reviewed to help building this index before examining the index validity for international organizations and other countries that differ in the culture. This study ends up with 35 items in 6 different factors. These factors were two social, two economic, one political, and one religious. The social domain had four items in avoiding prejudice and eight items in coexistence, integration, inclusiveness, and cohesion. The economic domain has five items in protecting others’ money and property and three items in economic exchange. The political domain has four items measuring freedom of expression and respect (respect for differences and political diversity). The final domain was the religious and has eleven items measuring respect for religious and doctrine differences.

The social-cultural dimension has two sub-dimensions. The first dimension is coexistence, integration, consolidation, and cohesion; it has eight items that were loaded and two items that were dropped because of inappropriate loading. The loading ranged between 0.563 for “I want to know about others’ customs and traditions” to 0.698 for “I respect others’ right to express their points of view about political issues” and “I respect the popular mode of dress of all the regions”. The second dimension is avoiding prejudice which has 4 items loaded and 12 items that were not loaded enough or which loaded in two dimensions. The loading ranged between 0.52 for “I accept holding international cultural events in my country” to 0.70 for “I am with women’s access to leading positions”. These items are consistent with the meaning of social and cultural tolerance as recognizing that differences between the individuals in the tribal, linguistic, religious, and sexual aspects of their life does not affect their loyalty to the same country (Velthuis et al. 2021; Chen 2017; Lee 2021). Additionally, this result is consistent with the Saudi context regarding the diversity in tribes, regions, and sects. The coexistence, integration, consolidation, and cohesion dimension covered the respect and acceptance of the difference with others regarding their culture and trip. The avoiding prejudice dimension covered the issues regarding accepting women to access leadership positions which is a great shift in Saudi society. Additionally, it covered the right to choose a life partner regardless of tribal affiliation which was a major cultural issue.

For the religious dimension, 11 items were loaded and only 2 items were dropped because of inappropriate loading. The loading was ranging between 0.537 for “I avoid making mockery of others’ religious rituals and practices” to 0.72 for “I accept working with people of different religions”. All these items were focused on respecting and accepting the other religious groups. These items are consistent with the definition of religious tolerance. According to Ghazwan (2021) religious tolerance focuses on respecting people who have different religious beliefs or practices. This result is appropriate in the Saudi context regarding religious issues since Saudi society has different doctrines and more than one-third of the population is from other countries, including non-Muslim countries.

The political dimension has four items that were loaded and three items that were dropped because of inappropriate loading. The loading ranged between 0.706 for “I recognize positions of other countries concerning some political issues” to 0.792 for “I accept criticism from others of my views on political issues”. The items were about accepting others’ criticism about political opinion as well as understanding other countries’ positions regarding political issues. These items aligned with the previous literature review as providing more space for different political opinions can lead to more tolerance (Djupe and Neiheisel 2021). This dimension is consistent with the current situation in Saudi society, especially with the popularity of using social media in Saudi Arabia. Using social media in Saudi Arabia is one of the most popular methods to discuss all types of issues including political issues.

The economic dimension has two sub-dimensions. The first dimension is maintaining the money and property of others and has five items loaded. The loading ranged between 0.627 for “I inform the concerned authorities in the event of an offence against others’ property” to 0.769 for “I maintain properties even if they belong to anyone in the community”. The second dimension is the economic exchange which has three items loaded and two items that were not loaded enough or that were loaded in two dimensions. The loading ranged between 0.634 for “I appreciate all products of high quality apart from the producer’s identity” to 0.738 for “When I sell anything, all what I care about is the financial value regardless of the purchaser”. These items were consistent with the definition of economic tolerance since the definition includes respecting public and private property as well as considering people’s situations when exchanging goods regardless of the differences between societies’ individuals (Berggren and Nilsson 2016). This dimension is appropriate with the current situation in Saudi society. According to the Saudi Vision 2030 (2017) Saudi Arabia needs to have an attractive environment in order to attract skilled people whether from Saudi Arabia or from other countries. Implementing the 2030 vision need a society with more tolerant values. This dimension includes both maintaining the money and property of others as well as the economic exchange which is important to attract skilled people from other countries.

Limitations and Strengths

Although the Tolerance Index was developed and validated based on a theoretical background and statistical procedures, it is important to pay attention to some limitations of this study. This study used exploratory factor analysis, which is one of the factor analysis methods, yet it is important to consider re-testing this index using both exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis by splitting the sample randomly into two equal sample sizes. This will give a more accurate result and will help to confirm the current result. Additionally, this study was based on self-report, so social desirability bias might have occurred. In addition, this was conducted in Saudi Arabia and the religious and cultural factors were considered while developing this index. Thus, it is important to consider these factors before using this index in other countries.

Regardless of these limitations, there are several strengths in this study. The large enough sample size is an advantage in this study. Additionally, the random sample size is another strength of this study since it exceeded the minimum sample size. In addition, this study included all types of living places (big cities, small cities, and villages) in all 13 administrative areas, so the ability to generalize the result for all the administrative areas is possible.

4. Materials and Methods

This study is a nationwide survey with a sample from every region of Saudi Arabia. The design of the study is cross-sectional. This method is appropriate because it makes it easier to objectively gather data and facts about a group of individuals living in a certain society or about a certain social issue. In order to accurately reflect the population throughout all Saudi regions, the index focuses on all Saudi society members who are 18 years of age or older in all significant regions, urban cities, peri-urban cities, and rural cities.

4.1. The Sample and Sampling

The study team sought to target a sample that represents the Saudi community (Saudi Statistics Authority 2021). The random sampling method was used in order to serve the objective of this index, which seeks to know the trends and perceptions of members of the Saudi society about the index and its domains and sub-domains. Geographical sampling was used in this study, which is a general case of the cluster sampling method, as it is a sample that is selected at different stages (Al-Qahtani 2015).

In First step, the 13 administrative regions in Saudi Arabia were selected as clusters, and in these regions, there are a group of main cities, a group of governorates, and centers that classified into two categories: Class A and Class B. These are considered sampling primary units (SPU), where the main city in each administrative region (cluster) was chosen in the sample. In addition, choosing a random sample with a proportional distribution from each of the governorates and centers was classified into two categories (A, B) because of their large number. The second step was considered sampling of secondary units (SSU). About 20% of the governorates was chosen from each region as well as 3% of the villages for each region using the simple or regular random sampling method.

The selected units of the sample (urban cities, peri-urban cities, and rural cities) were divided into neighborhoods or residential squares. Then, the researchers distributed the specified sample size for each unit over these residential squares or neighborhoods equally. They selected a sample of individuals in each neighborhood or residential square, and the number of housing units or houses in each residential square was counted and chosen. The number of individuals required of them was randomly assigned according to the reality of the houses and dwellings in each residential square after its numbering. The neighborhoods were targeted according to the division of cities and governorates into squares on the geographical maps, and then balanced squares were taken from each direction (east–west–south–north–center).

This sampling resulted in 1071 participants in this study (43.5% of them were females). When looking to the participants’ age group, we found the participants who were aged from 40 to less than 50 were the highest percentage (34.5%), while those who were aged 60 or older were the lowest percentage (3.1%). More than half of the participants have a bachelor’s degree, while only 0.20% have completed only their elementary school education. Additionally, the participants from Ar Riyadh consist of 24.8%, while those from Tabuk make up 1.80%. About 59.70% of the participants were from urban cities and only 10.6% were from rural cities.

4.2. Instrument

The first edition of the Tolerance Index (2019) by the King Abdulaziz Center for National Dialogue was used in this study. This index has the following domains: (1) The social and cultural dimension, which contains 2 sub-dimensions. (2) Detachment from prejudice consists of 16 items; (3) integration consists of 10 items. (4) The economic dimension contains 2 dimensions; (5) preserving the property of others consists of 5 items; (6) economic exchange consists of 5 items. (7) The political dimension, which is the respect and appreciation of difference and political diversity, consists of 7 items; and (8) the religious dimension, which is about respecting and appreciating religious and sectarian differences, consists of 13 items.

4.3. Statistical Analysis

This study used Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23 to analyze the data. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was used to validate the Tolerance Index. Before using the Factor Analysis, data should be verified for the two basic conditions when using this statistical method—such conditions are: (1) sufficient sample size and (2) availability of a statistically significant correlation between variables adequate for using the factor analysis. Adequacy of the sample size can be checked through Kaiser-Meyer- Olkin measure of sampling adequacy known as KMO. It compares between the observed correlation coefficients and the partial correlation coefficients. Sample size is considered fully adequate when the scores are higher than the unacceptable limit, i.e., less than 0.50. Furthermore, statistically significant correlation between variables sufficient for using the factor analysis can be deduced through Bartlett’s test of sphericity to check the overall significance of all correlations within the matrix. It can also ensure that the correlation matrix of the community is not the identity matrix where the value of components is 0.0 and the value for the diagonal components is 1; this infers that total significance of the test is less than 0.05 (Ashour and Salem 2005).

5. Conclusions

We have developed a 35-item, six-factor scale for evaluating the tolerance values in Saudi Arabia. This index reflects different aspects of tolerance including two social, two economic, one political, and one religious aspects. This index can help to evaluate the tolerance over time and compare the results to detect the tolerance trend. Additionally, the index can help to identify which aspects of the tolerance need improvement interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.A. and K.A.-M.; methodology, S.A., K.A.-M., and N.A; validation, S.A., N.A., K.A.-M. and M.A.; formal analysis, S.A. and M.A.; investigation, N.A.; resources, M.A.; writing—original draft preparation S.A., K.A.-M. and M.A.; writing—review and editing, S.A. and K.A.-M.; supervision, N.A.; project administration, K.A.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the King Abdulaziz Center for National Dialogue in Saudi Arabia, for funding this research work through project number N/6/3.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Central Institutional Review Board, Ministry of Health, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (HAP-01-R-059; 28 March 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request by contacting the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Al-Bakr, Fawziah, Elizabeth R. Bruce, Petrina M. Davidson, Edit Schlaffer, and Ulrich Kropiunigg. 2017. Empowered but Not Equal: Challenging the Traditional Gender Roles as Seen by University Students in Saudi Arabia. FIRE: Forum for International Research in Education 4: 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albraithen, Abdulaziz bin Abdullah. 2019. Tolerance from a social perspective: Emirati society as a model. Journal of Social Affairs, United Arab Emirates 36: 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Albrifkani, Ahmad Khawlah, and Ghosoon Khaled Al-Obaidi. 2020. Social tolerance and its relation to personal characters for the students of college of basic education. Journal of Education College Wasit University 3: 1223–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fatlawi, Suhail Hussein. 2018. Accepting the Other and Tolerance in the International Law of Human Rights. Journal of Law & Political Sciences 15: 8–44. [Google Scholar]

- AL-Geboory, Manaf. 2014. Intellectual Tolerance and Its Relation to Social Cohesion for University Students. Lark Journal for Philosophy, Linguistics and Social Sciences 14: 367–423. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jumaili, Talal Ahmed. 2021. The monotheistic religions and their impact on spreading tolerance: Christianity as a model. Journal of Historical and Cultural Studies 12: 109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mawardi, Abo al-Hasan al-Baghdadi. 1986. Literature of the World and Religion. Beirut: Life Library Publishing Hous. [Google Scholar]

- Alomiri, Hamdi. 2015. The Impact of Leadership Style and Organisational Culture on the Implementation of E-Services: An Empirical Study in Saudi Arabia. Doctoral dissertation, Plymouth University, Plymouth, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qahtani, Saad. 2015. Applied Statistics: Basic Concepts and Statistical Analysis Tools Most Used in Social and Human Studies and Research Using SPSS. Riyadh: Research Center of the Institute of Public Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Arab News. 2020. KSA Likely to See 30 Million Religious Tourists by 2025. Saudi Arabia. Available online: https://www.arabnews.com/saudi-arabia/news/814841 (accessed on 5 November 2022).

- Ashour, Samir Kamel, and Samia Aboul Fotouh Salem. 2005. Presentation and Analysis Using Advanced Applied Statistics. Cairo: National Book House. [Google Scholar]

- Aslan, Serkan. 2018. Relationship between the Tendency to Tolerance and Helpfulness Attitude in 4th Grade Students. International Journal of Progressive Education 14: 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangwayo-Skeete, Prosper F., and Precious Zikhali. 2011. Social tolerance for human diversity in Sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Social Economics 38: 516–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, Mehak, and Bushra Akram. 2020. Development and validation of religious tolerance scale for youth. Journal of Religion and Health 59: 1481–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berggren, Niclas, and Therese Nilsson. 2016. Tolerance in the United States: Does economic freedom transform racial, religious, political and sexual attitudes? European Journal of Political Economy 45: 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bödeker, Hans Erich, Clorinda Donato, and Peter Reill, eds. 2008. Discourses of Tolerance & Intolerance in the European Enlightenment. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau, Cheryl, and Scott A. MacKenzie. 2018. Wanting what is fair: How party cues and information about income inequality affect public support for taxes. The Journal of Politics 80: 367–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broglio, Francesco Margiotta. 1997. Tolerance and the Law. Ratio Juris 10: 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Wei-Lin. 2017. Social Desirability Bias and Social Tolerance: A Monte Carlo Simulation Analysis. International Journal of Intelligent Technologies & Applied Statistics 10: 257–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, Jayoti, Cassandra DiRienzo, and Thomas Tiemann. 2008. A global tolerance index. Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal 18: 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djupe, Paul A., and Jacob R. Neiheisel. 2021. The Dimensions and Effects of Reciprocity in Political Tolerance Judgments. Political Behavior 44: 895–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ERSANLI, Ercümend. 2014. The validity and reliability study of tolerance scale. Journal of Basic and Applied Scientific Research 4: 85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Ersanli, Ercümend, and Shiva Saeighi Mameghani. 2016. Construct Validity and Reliability of the Tolerance Scale among Iranian College Students. Journal of Education and Practice 7: 99–105. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, Yohanan. 2003. Tolerance and Coercion in Islam: Interfaith Relations in the Muslim Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- García-Castro, Juan Diego, Rosa Rodríguez-Bailón, and Guillermo B. Willis. 2020. Perceiving economic inequality in everyday life decreases tolerance to inequality. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 90: 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazwan, Anas Abdullah. 2021. The Role of Tolerance in Promoting a Culture of Peaceful Coexistence: An Analytical Study in Religious Sociology. Journal of Human Sciences 28: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, Aya. 2015. Zero-Tolerance Comes to International Law. AJIL Unbound 109: 337–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haerpfer, Christian, Ronald Inglehart, Alejandro Moreno, Christian Welzel, Kseniya Kizilova, Jaime Diez-Medrano, Marta Lagos, Pippa Norris, Eduard Ponarin, and Bi Puranen. 2020. World Values Survey: Round Seven–Country-Pooled Datafile. Madrid and Vienna: JD Systems Institute & WVSA Secretariat. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, Joseph F., Rolph E. Anderson, Barry J. Babin, and William C. Black. 2010. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Sam, and Maajid Nawaz. 2015. Islam and the Future of Tolerance: A Dialogue. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, Mazen, and Marwa Shalaby. 2019. Drivers of Tolerance in Post-Arab Spring Egypt: Religious, Economic, or Government Endorsements? Political Research Quarterly 72: 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Riaz. 2009. Interrupting a history of tolerance: Anti-Semitism and the Arabs. Asian Journal of Social Science 37: 452–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (HCDP) Human Capability Development Program. 2022. Human Capability Development Program Aims. Saudi Arabia, Riyadh. Available online: https://na.vision2030.gov.sa/v2030/vrps/hcdp/ (accessed on 5 November 2022).

- Hegazi, Huda Mahmoud. 2022. Towards a Program for General Practice of Social Work to Promote a Culture of Tolerance as a Mechanism for Achieving Community Security. al-Fikr alShurti 31: 121–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjerm, Mikael, Maureen A. Eger, Andrea Bohman, and Filip Fors Connolly. 2020. A New Approach to the Study of Tolerance: Conceptualizing and Measuring Acceptance, Respect, and Appreciation of Difference. Social Indicators Research 147: 897–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King Abdulaziz Center for National Dialogue (KACND). 2017. Social Coexistence among Saudi Society. Riyadh: King Fahd National Library. [Google Scholar]

- King Abdulaziz Center for National Dialogue (KACND). 2022. King Abdulaziz Center for National Dialogue Website. Saudi Arabia, Riyadh. Available online: https://www.kacnd.org/ar/Details/index/19 (accessed on 5 November 2022).

- Keshi, Emad A. 2022. Tolerance, cohesion and coexistence: A conceptual reading in the Saudi social context. Journal of Research and Social Studies. National Center for Research and Social Studies, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia 2: 49–71. Available online: https://www.rssj.org/index.php/rssj/article/view/57 (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Kwasnicki, Witold. 2021. The role of diversity and tolerance in economic development. Journal of Evolutionary Economics 31: 821–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Sanghoon. 2021. Social Tolerance and Economic Development. Social Indicators Research 158: 1087–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Transformation Program (NTP). 2022. National Transformation Program Aims. Saudi Arabia, Riyadh. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/v2030/vrps/ntp/ (accessed on 5 November 2022).

- Papastephanou, Marianna. 2005. Rawls’ Theory of Justice and Citizenship Education. Journal of Philosophy of Education 39: 499–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persell, Caroline Hodges, Adam Green, and Liena Gurevich. 2001. Civil society, economic distress, and social tolerance. Sociological Forum 16: 203–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, Gabriele. 2021. The Relationship Between Political Participation and Life Satisfaction Depends on Preference for Non-Democratic Solutions. Applied Research in Quality of Life 17: 1867–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, John. 2002. Punishment and Civilization: Penal Tolerance and Intolerance in Modern Society. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmat, Munawar, and Wildan bin Yahya. 2022. The Impact of Inclusive Islamic Education Teaching Materials Model on Religious Tolerance of Indonesian Students. International Journal of Instruction 15: 347–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizqiany, Ukhiya. 2017. Religious tolerance value analysis perspective teachers of Islam, Christian and Catholic religious education in SMK Demak. ATTARBIYAH: Journal of Islamic Culture and Education 2: 236–55. [Google Scholar]

- Salam Project for Cultural Communication. 2021. Cultural Diversity in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Riyadh: King Fahd National Library. [Google Scholar]

- Salem, Al-Sayed A. 2003. The Political and Cultural History of the Arab State. Alexandria: University Youth Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Press Agency. 2022. His Highness the Crown Prince, in an Interview with the Atlantic Magazine, Confirms: Saudi Arabia Is Developing According to Its Economic and Cultural Foundations, Its People, and Its History. Kingdom Saudi Arabia. Available online: https://www.spa.gov.sa/2334337 (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- Saudi Statistics Authority. 2021. Population estimates for 2021. Kingdom Saudi Arabia. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.sa/sites/default/files/POP%20SEM2021A.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- Saudi Vision 2030. 2017. Arabia, Riyadh. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/media/rc0b5oy1/saudi_vision203.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2022).

- Streeter, Joseph. 2021. Conceptions of Tolerance in Antiquity and Late Antiquity. Journal of the History of Ideas 82: 357–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasheva, Marija. 2021. The Religious Tolerance in Medieval Spain. Balkan Social Science Review 17: 265–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tender, Lars. 2013. Tolerance: A Sensorial Orientation to Politics. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- United Nation. 2022. World Day for Cultural Diversity for Dialogue and Development. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/observances/cultural-diversity-day (accessed on 8 November 2022).

- Velthuis, E., M. Verkuyten, and A. Smeekes. 2021. The Different Faces of Social Tolerance: Conceptualizing and Measuring Respect and Coexistence Tolerance. Social Indicators Research 158: 1105–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Pei. 2019. Towards a morally defensible concept of toleration: Insights from ancient Chinese thinking. Philosophy & Social Criticism 45: 461–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya Mulya, Teguh, and Anindito Aditomo. 2019. Researching religious tolerance education using discourse analysis: A case study from Indonesia. British Journal of Religious Education 41: 446–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, Abbas. 2020. The culture of peace and religious tolerance from an Islamic perspective. Journal of Philosophy & Theology 47: 151–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zanakis, Stelios H., William Newburry, and Vasyl Taras. 2016. Global social tolerance index and multi-method country rankings sensitivity. Journal of International Business Studies 47: 480–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).