Abstract

The dissemination and acceptance of Chinese-language Buddhist films in China have not yet received much attention. This paper takes four Chinese-language Buddhist films as samples to analyze the Buddhist doctrines they contain and how they are reviewed by the Chinese working class. It points out that most Chinese working-class people are not Buddhists, their knowledge of Buddhist doctrines is relatively small and shallow, and they rely on their daily life experiences when enjoying Buddhist films, so they cannot understand Buddhist doctrines in Buddhist films that are too difficult or contrary to their daily life experiences. It argues that Chinese-language Buddhist films need to balance the missionary aspirations of Buddhism with the popular attributes of cinema so as to enhance the appeal and influence of Buddhism among the working class.

1. Introduction

Paul Weiss once said: “All human art is essentially religious art. To perceive beauty is to be moved by something in the emotional process, which is the same as the emotional process that accompanies the perception of God, and to create beauty is to some extent share the attributes of God” (Weiss and Von Ogden 1999). As an artistic style that acts on the mind, the film has natural religious potential, and its powerful “Subject Interpellation” function means it, similar to religion, has a considerable influence on the public. Therefore, since its inception, the film industry has been widely valued by various cultural forces, including Buddhism.

The combination of Buddhism and cinema has given rise to a large number of Buddhist films. Whether it is in the United States, Korea, India, Bhutan, China, Japan, Thailand, etc., many Buddhist films have been produced. However, because of the different national conditions of each country, the cultural concepts of audiences, and the Buddhist knowledge they possess, there are great differences in the understanding and commentary of Buddhist films among audiences in different countries. At present, the study of Buddhist films in the United States, Korea, Thailand, and other countries has made great progress, but the dissemination and acceptance status of Chinese-language Buddhist films in China has not yet attracted much attention.

Buddhism has a long history in China, and China has produced a large number of Buddhist films. However, after all, Buddhists are a minority in both the total Chinese population and the Chinese working class. The Chinese working class1, as the largest group in the Chinese population, is bound to be limited in its understanding and acceptance of Buddhist films by its own conditions, which creates a conflict between the uniqueness of Buddhist teachings and the universality of working-class values. This paper selects four Chinese-language Buddhist films for examination and verifies the validity of this argument by analyzing the movie reviews of the Chinese working class published on two movie review websites, Douban Movie, and Mtime.

2. Buddhist Film and Working Class

2.1. Buddhist Film

As a visual art, films can take on the role that has been played by traditional Buddhist icons and images. The film serves as one of the most recent contributions to the variety of Buddhist visual forms that can offer a perspectival shift in interpretation for its viewers akin to other meditative devices such as mandalas (Suh 2018). The film can articulate Buddhist teachings and, more significantly, Put them into Practice. This means taking the film seriously as a medium for cultivating certain ways of being in the world that has previously been attained through ritual and contemplative Practices (Cho 2017). The cinema allows viewers to go through a journey of individuation similar to that undergone by the protagonists of the films. While traveling together with the characters in the space of the cinema, viewers are presented with ideologies and symbols from Buddhism that have the potential to bring about transformations in their own minds (Low 2014). Since the silent movie The Light of Asia, a German-Indian co-production released in the USA in 1928, increasing numbers of films have been produced across the globe that is related in some way to Buddhism. Since 2003, when the first International Buddhist Film Festival was held in Los Angeles, there have been dozens of similar events around the world. The practice of exploring Buddhism through movies has since steadily increased, and similar events have been organized throughout the United States, in London, Amsterdam, Singapore, Calgary, Bangkok, Melbourne, Kuala Lumpur, and other global cities (Whalen-Bridge 2014). In the specific conditions of the modern period and an increasingly globalized world, a new field of research gradually formed, which has continued to develop to the present day (Renger 2014). As a relatively recent subject of study, Buddhist films present innovative opportunities to visualize the Buddha, Buddhism, and the self in nuanced ways. With a range of films with an explicitly Buddhist theme and content to more abstract films without obvious Buddhist references, Buddhist films have become the subject of scholarly studies of Buddhism as well as occasions to reimagine Buddhism on and off the screen. Buddhist films found in Asia and the West have proliferated globally through the rise of international Buddhist film festivals over the past nineteen years that have increased both the interest in Buddhism and the field of Buddhism and film itself (Suh 2018).

In recent years, a number of remarkable studies have emerged in the field of Buddhist film studies. The Bloomsbury Companion to Religion and Film, edited by William L. Blizek, offers the definitive guide to study in this growing area. The book covers all the most pressing and important themes and categories in the field—areas that have continued to attract interest historically, as well as topics that have emerged more recently as active areas of research (Blizek 2013). Ronald S. Green’s Buddhism Goes to the Movies (Green 2013) is a discussion of key concepts and major traditions of Buddhism in a variety of films. Buddhism and American Cinema (Whalen-Bridge and Storhoff 2014), edited by John Whalen-Bride and Gary Storhoff, is a collection of essays mostly written by specialists in various academic fields, particularly English. This book is a welcome and useful contribution to the growing area we may call representations of Buddhism in film. The articles are engaging, and the authors demonstrate an understanding of American pop culture and film criticism. Those interested in these topics will find the book quite valuable. Sharon A. Suh’s book Screen Buddhism: Buddhism in Asian and Western Cinema is priceless to the reader for its exaggerated critique of Orientalism, gender, and distortion of asceticism. It can help them understand representations of Buddhism in film and some of the wider implications of those representations (Green 2015b). The Journal of Religion & Film is a peer-reviewed journal that is committed to the study of connections between the medium of film and the phenomena of religion. Since its inception as one of the first academic peer-reviewed online journals in 1997, The Journal of Religion & Film has grown to become one of the most respected publications in the field. The journal has published numerous research papers on Buddhist cinema.

Much progress has been made in the country-specific studies of Buddhist cinema. In the field of American Buddhist film studies, many topics have been fully discussed (Reed 2007; Olmsted 2012; Feichtinger 2014; Mullen 2014, 2016; Struhl 2014; Whalen-Bridge and Storhoff 2014; Green 2015a; Barker 2022). Similarly, Korean Buddhist films have been studied in depth, and a series of excellent research have been achieved (Cuasay 1997; James 2001; Cho 2014; Mun and Green 2015, 2016; Green and Mun 2019; Suh 2022). Even in a country such as Thailand, where the film industry is not very developed, research on Buddhist films has received attention from scholars, and relevant research papers have been published one after another (Fuhrmann 2009, 2016; Sounsamut 2022). However, unfortunately, as a major film-producing country, China has produced a large number of Buddhist films that have not yet received the attention of the academic community. There is very little research on Chinese Buddhist cinema. Four Chinese Buddhist films, The Shaolin Temple, Shaolin, Green Snake, and Running On Karma, are selected for study in this paper, which can present a Chinese picture of Buddhist films and fill in the Chinese section of Buddhist film studies.

2.2. Working Class

In both Western countries and China, the connotation of the “working class” has evolved with historical development.

The emergence of the working class was linked to capitalist mass machine production and was the product of the great industrial revolution. The modern worker is proletarian. For the classical writers of Marxism, the working class has two distinctive characteristics: first, it is “proletarian,” and second, it has class consciousness. The Communist Manifesto clearly states that “the proletariat is the modern working class.” Engels explained the meaning of “proletarian”: the proletariat refers to the modern working class that has no means of production of its own and therefore has to sell its labor to make ends meet (Marx and Engels 1972). With the expansion of the socialization of capitalist production, the division of labor and the collaboration of labor processes became more and more complex, and the concept and connotation of the working class also developed and changed. After the Second World War, the developed capitalist countries in the West implemented the welfare state system in their social policies in order to weaken the increasingly intensified class contradictions. With the advancement of modernization, their socio-economic structures also underwent significant changes, and two significant changes in the composition of their working-class also emerged. First, the phenomenon of the “middle class” of the working class has emerged, and second, the class consciousness of the working class has faded, and a “working class subject crisis” has emerged (Ralf Dahrendorf 2001). The dramatic changes in the class structure of Western developed countries, especially the dual changes in the occupational and employment structures, have led to intense debates in Western academic circles on the formation of the working class, the decline of the working class, and the end of class.

The dramatic changes in the social class structure of developed Western countries after World War II have led to intense debates in Western academia on a range of topics surrounding the working class, particularly the working class decline thesis. French left-wing scholar André Gorz claimed that a non-class of non-workers or a “new proletariat” had emerged (Gorz 1997). Clark and Lipset even argue that the traditional hierarchical system of social stratification is in decline and that the reference to class is obsolete. Classes are in decline in the political, economic, and family spheres, social classes are dead, and new forms of social stratification have emerged (Clark and Lipset 1991). In the United States, neo-Marxist scholar Burawoy argues that the working class is identified as a class that has increasingly lost its historical significance. Working-class domination of traditional social movements would exit the stage of history, and new social movements would gradually emerge (Burawoy 1990). In Europe, Touraine similarly argues that in post-industrial societies, the working class is no longer the main force of social movements and social change and that new social movement subjects will certainly develop, leading new social movements and forming new social trends of thought (Wallis 1981). In contrast, other sociologists hope to revise the traditional class theory through careful empirical research. The British scholar Phil Hearse, for one, believes that the class consciousness of the working class may have declined in Western countries, but this does not mean the demise of the class; the relative size of the working class may continue to expand and still maintain the political energy and social role it used to have (Hearse 2009). In addition, for Broadway, neoliberal globalization has shaped a new, global working class in the form of an international reorganization of the industrial working class: the industrial working class, which had drifted away from the developed West, is rapidly emerging in the developing world, and China, in particular, is becoming the base for a global revival of the industrial working class (Burawoy 1990).

In China, the connotation of the “working class” has also been evolving. Before the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the Chinese working class emerged in close connection with socialized mass production. They generally did not have the means of production and were wage laborers who sold their labor to make a living. These characteristics were very similar to those of the working class in the early days of capitalist industry, presenting basic features consistent with those of the proletariat as described by classic Marxist writers. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the working class was transformed from an exploited and oppressed class in the past into the leading class of the state, and the condition of the working class underwent profound changes. At the beginning of the People’s Republic of China, the working class mainly referred to the industrial workers, and at that time, according to both political and economic criteria, China’s employees were divided into “four classes and one stratum,” namely, the working class, the peasant class, the petty bourgeoisie, the national bourgeoisie, and the managerial stratum. Then, in 1956, after the completion of the socialist transformation of the private ownership of the means of production, China entered a socialist society, and the ownership structure gradually tended to be homogeneous, with only a national and collective ownership economy. The social class structure then underwent significant changes, with the petty bourgeoisie and the national bourgeoisie gradually disappearing, the management stratum ceasing to be independent and becoming an integral part of the working class, and the social structure showing a trend of simplification. Only the working class, the peasant class, and the intellectual stratum remained in China, forming a social structure of “two classes and one stratum.” In addition, in January 1956, Zhou Enlai, on behalf of the Central Committee, proposed a conference on intellectuals that “the vast majority of intellectuals already serve socialism and are already part of the working class.” In 1978, Deng Xiaoping pointed out at the National Science Conference that intellectuals “are overwhelmingly the intellectuals of the working class and the working people themselves, and therefore can be said to be part of the working class.” In this way, the intellectual stratum also became part of the working class. There would be only the working class and the peasant class in China. After the reform and opening up, as China’s industrialization and urbanization accelerated, a large number of migrant workers began to emerge, bringing about new changes in the structure of China’s social class. In 2003, the 14th National Congress of Chinese Trade Unions proposed for the first time that “a large number of urban migrant workers have become new members of the working class,” and in 2004, the No. 1 Document of the Central Government emphasized again that “migrant workers who have moved to cities for employment have become an important part of China’s industrial workers. “This has further expanded the working class. After entering the information society, the development of technologies such as the Internet and big data has stimulated market vitality and given birth to a large number of new industries and new business models, creating a large number of new situations of flexible employment and further expanding the ranks of the working class in China (Li and Yu 2021). In contemporary China, the working class is divided into the class of state and social managers, the class of enterprise managers, the class of professional and technical personnel, the class of ordinary urban workers, the class of migrant workers, the class of laid-off and unemployed workers, and the class of flexible employment (Liu 2011). According to 2019 statistics, the size of China’s working class accounts for 74.9% of China’s working population (The Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security of the People’s Republic of China 2019).

3. Expressions on Buddhism: An Analysis of Four Chinese-Language Buddhist Films

3.1. A Selection of Four Chinese-Language Buddhist Films

There is no exact definition of what a Buddhist film is, but there is a roughly defined range of perception. In Chapter 1 of Silver Screen Buddha, the Introduction, Sharon A. Suh defines a “Buddhist film” as one that fits one or more of the following criteria:

- contemplation and inquiry about the eradication of thirst or desire;

- the virtues and limitations of monastic life;

- inclusion of elements of a prototypical Buddhist mise-en-scéne such as a monastery, hermitage, or lay community;

- exploration and application of Buddhist doctrines and philosophical concerns;

- offer of Buddhist interpretations of reality or a uniquely Buddhist solution to a social problem (Suh 2015).

Although this definition is not perfect, and further refinements exist (Green 2015b), it still roughly outlines the defining framework of Buddhist cinema for reference.

I selected four Chinese-language Buddhist films, namely The Shaolin Temple, Shaolin, Green Snake, and Running on Karma, as samples for analysis. There are two reasons for doing so: First, the four films are all typical Buddhist films with sufficient Buddhist elements and content. Secondly, the four Buddhist films were directed by well-known Chinese directors and performed by Chinese film stars. In their release years, they were all films with a wide audience and were generally well-received by the public. Then, many years after the public release, there were still a large number of fans who watched it through movie channels or DVD discs. Furthermore, there are a large number of film reviews published on Chinese film review websites, which makes it easier to gauge the acceptance among the Working-class audience of these Buddhist films.

3.2. What Do These Four Buddhist Films Say about Buddhism and How Do They Say It?

It is difficult to ascertain the exact time of the introduction of Buddhism into China. According to historical records, in the 7th year of the Yongping Era (64AD), the Emperor Ming of the Han Dynasty sent twelve emissaries to the Western Regions in search of the Buddha Dhamma. They returned to Luoyang and brought scriptures and statues of the Buddha back with them. They began to translate parts of Buddhist scriptures. The course of translating Buddhist scriptures into Chinese lasted 10 centuries, with no less than 200 famous Chinese and foreign translators involved. Through the persevering, industrious efforts of so many people, Buddhist theories were introduced into China, thereby forming the enormous treasures of Chinese Buddhism. The Chinese Buddhist canon was mostly translated from Sanskrit, with a few texts from Pāli. The Buddhist canons can be classified into three systems according to the languages employed: (1) Pāli, (2) Chinese, and (3) Tibetan (Zhao 2012). Because I am a Han nationality and studied Chinese, the sutras I read are all Chinese translations of Buddhist scriptures, so the Buddhist teachings quoted in this article are all Chinese versions.

The Shaolin Temple: Among the numerous Buddhist temples in China, the Shaolin Temple is undoubtedly one of the most famous. The Shaolin Temple is the ancestral home of the Zen sect of Chinese Buddhism. It occupies an important position in the history of Chinese Buddhism. The movie The Shaolin Temple focusses on Shaolin, which is closely related to Buddhism. It is set in the late Sui Dynasty, and the plot is based on the story of Wang Renze, the nephew of general Wang Shichong, who killed the rebellious “God Leg Zhang” while supervising the construction of river fortifications. The son of “God Leg Zhang,” Xiaohu fled to the Shaolin Temple and was rescued by a monk named Tanzong. In order to avenge his father’s death, Xiaohu worshipped Tanzong as his teacher, practiced Shaolin martial arts, and cut his hair to become a novice, taking the name Jueyuan. One day, Li Shimin (the future emperor of the Tang Dynasty) was besieged by Wang Renze when he was smuggled across the Yellow River, and Jueyuan and others tried to rescue him. Wang Renze then accused someone in the Shaolin Temple of collaborating with the enemy and planned to destroy the Shaolin Temple. The monks fought to the death, with Tanzong falling in battle. At this time, Li Shimin led his troops back and captured Luoyang after Wang Renze’s soldiers’ mutiny, and Wang Renze was killed by Jueyuan. Finally, in order to inherit the legacy of Tanzong, Jueyuan is ordained as a monk.

As a “Shaolin Temple” movie, The Shaolin Temple has a strong Buddhist theme. On the one hand, The Shaolin Temple is full of Buddhist elements and images, such as ancient temples, morning bells and evening drums, solemn Buddha images, and old monks and abbots; meanwhile, The Shaolin Temple also adheres to many Buddhist doctrines, such as “giving” and “forbearance.” The old abbot in the movie donated his body to protect the temple and monks, resolutely stepping into the fire set by the thieves, reflecting the true nature and fearless generosity of eminent monks. Another example is “rebooting and abstaining from prostitution.” At the end of the film, although he and the shepherdess are in love, Jueyuan, who has already decided to be ordained as a monk, reluctantly gives up his love and devotes himself to Buddhism. However, at the core of the story, The Shaolin Temple is a movie about “revenge,” resulting in a film with more secular themes than other Buddhist narratives because, from the perspective of Buddhism,

All the signs we see are illusions. A sign is neither tangible nor intangible. Buddhas are free from illusions. A person has the insight into the truth if sees through a sign.(Kumārajīva 2020)

Cause and effect are reciprocal, good and evil circulate, and the three worlds will reincarnate. All people, whether good or bad, are treated equally by Buddhism, and they are regarded as people who can “cross,” and naturally, there is no “enmity” to repay.

Overall, as a Buddhist film, The Shaolin Temple not only promotes Buddhist doctrines but also leaves enough space for the expression of human nature. While it adheres to the strict rules and precepts of Buddhism as much as possible, to meet the general logic of film narrative rules, it “breaks” the “precepts.” Eating meat, killing and revenge are contrary, and even disrespectful, to Buddhist doctrines, especially in the final scene where Jueyuan kills Wang Renze. The sutra says:

You should understand that these people who eat flesh may gain some modicum of mental awakening that resembles samādhi, but they are all great rākṣasas who in the end must fall into the sea of death and rebirth. They are not disciples of the Buddha.(Dharma Realm Buddhist Association 2018)

No matter how much you may practice samādhi in order to transcend the stress of entanglement with perceived objects, you will never transcend that stress until you have freed yourself from thoughts of killing. Even very intelligent people who can enter samādhi while practicing meditation in stillness are certain to fall into the realm of ghosts and spirits upon their rebirth if they have not renounced all killing.(Dharma Realm Buddhist Association 2018)

However, The Shaolin Temple satisfies the basic requirements of film narrative rules for “punishing evil and promoting good,” including the audience’s psychology, which demands that “good people are rewarded, and bad people suffer.”

Shaolin: As the sequel to The Shaolin Temple, Shaolin was filmed 30 years later. It was funded by the Shaolin Temple and supervised by the current abbot of the Shaolin Temple, Shi Yongxin. Therefore, to a certain extent, it ensures that the film remains faithful to Buddhism. The film’s narrative is set during the period of the Republic of China, during which the great warlord Hou Jie performed vast evil deeds, including killing an unarmed opponent in front of the monks in the Shaolin Temple, as well as killing his long-term sworn brother. However, he was framed by his subordinate Cao Man, and his family was destroyed; subsequently, his beloved daughter was lost. Hou Jie took refuge in the Shaolin Temple. Later, he was ordained as a monk and became enlightened while reading Buddhist scriptures. In order to hunt down Hou Jie, Cao Man led his troops to bloodshed at the Shaolin Temple. In the face of a hostile enemy, Hou Jie demonstrates a compassionate heart and perseveres in persuading Cao Man to correct his wrongdoing and return to the right path to avoid repeating his karma. As a result, the Shaolin Temple was sacked during the war, and the abbot and other monks died in the process of protecting the temple and saving its people. Hou Jie also sacrificed his life in his mission to redeem the enemy, Cao Man.

Compared with The Shaolin Temple, Shaolin is no different in terms of story structure and Buddhist elements; however, its novelty is reflected in its ending. The ending of The Shaolin Temple is that Jueyuan kills Wang Renze and completes his revenge, while the ending of Shaolin is that Hou Jie pursues the redemption of his enemy Cao Man through self-sacrifice. Shaolin’s unusual ending is far from the narrative rules of Chinese cinema and, instead, adheres closely to the principles of Buddhist doctrines because, according to Buddhism,

What is entirely beyond all defining attributes—that is the entirety of Dharma.(Dharma Realm Buddhist Association 2018)

Ordinary people have real sins and real blessings, which are called two. Moreover, the sage realizes that there is no real sin and no real blessing. On the basis of eliminating evil and cultivating goodness, he realizes the emptiness of sin and blessings with a solid, sharp, and bright prajna wisdom akin to a diamond. Regarding this, the scriptures say:

“Arising all good dharmas is an illusion, and creating all kinds of bad karma is also an illusion”.(Lai 2010)

Good and Wise Friends, unawakened, Buddhas are just living beings. At the moment they awaken, however, living beings are Buddhas. Therefore, you should realize that the ten thousand dharmas are all within your own mind.(Dharma Realm Buddhist Association 2017)

In Buddhism, the emphasis is on cause and effect, not right and wrong. Buddhists believe that what the world shows is only an appearance, and mortals cannot clearly see the law of cause and effect. Therefore, judgments of good and evil are often not true. When someone receives bad results, it is because of the evil causes that were planted in the past, as good and evil have causes and effects, and they circulate in three generations. In Mahayana Buddhism, it is even more difficult to distinguish between good and evil because “all appearances are illusory,” and good and evil are also false. Only by removing the two sides and making no distinction can we approach the middle way, which is the holy truth of Buddhism.

Therefore, we can see that at the end of Shaolin, when Hou Jie, who has obtained the true meaning of Buddhism, faces the wicked enemy Cao Man, he does not have the impulse of revenge. Instead, he feels pity in his heart and attempts to “rescue” Cao Man and, by doing so, finally completes his conversion to Buddhism through his self-sacrifice. Shaolin is a movie about “redemption,” and Hou Jie has the spirit of the Earth Store Bodhisattva. Earth Store Bodhisattva has made the following great vow:

“From now until the end of future time throughout uncountable eons, I will use expansive expedient means to help beings in the six paths who are suffering for their offenses. Only when they have all been liberated, will I myself become a Buddha.”(Dharma Realm Buddhist Association 2020)

“Only after beings with such retributions have all become Buddhas will I myself achieve Proper Enlightenment.”(Dharma Realm Buddhist Association 2020)

But such an ending clearly contradicts the narrative rules of the film. The protagonists tragically die, and the villain, Cao Man, appears on the screen alone, challenging the audience’s deepest-held values, namely that “good is rewarded with good and evil is rewarded with evil.”

Green Snake: This is a movie about “lust.” In Buddhism, lust is a great obstacle to religious practice, and it is one of the five precepts of Buddhism. The rejection of lust among world religions is the most severe in Buddhism. In the Surangama Sutra, the Buddha earnestly taught that:

In all worlds, beings in the six destinies whose minds are free of sexual desire will not be bound to an unending cycle of deaths and rebirths. No matter how much you may practice in order to transcend the stress of entanglement with perceived objects, you will never transcend that stress until you have freed yourself from sexual desire. Even very intelligent people who can enter samādhi while practicing meditation in stillness will be certain to fall into the realm of demons upon their rebirth if they have not renounced sexual activity.(Dharma Realm Buddhist Association 2018)

Therefore, when you teach people to practice samādhi, first teach them to rid their minds of sexual desire. That is the first of four clear and definitive instructions on purity that have been given by the Thus-Come One and by all the Buddhas of the past, Worly-Honored Ones. Therefore, Ānanda, one who practices entering samādhi while practicing meditation in stillness without renouncing sexual activity is like one who cooks sands in the hope that it will turn into rice. A hundred thousand eons might pass and it would still be nothing but hot sand, since it wasn’t rice to begin with. It was merely sand.(Dharma Realm Buddhist Association 2018)

Therefore they should look upon sexual desire as upon a venomous snake or a brutal thief.(Dharma Realm Buddhist Association 2018)

If one cannot cut off lust and practice Buddhism, it is such as frying rice with sand and stones, and one cannot succeed in cultivating it anyway. Therefore, in Green Snake, the Buddhist monk Fahai, in the name of slaying demons and eliminating demons, must break up the marriage between Bai Suzhen and Xu Xian, no matter the cost. Among the four films selected as a sample, Green Snake is the film that most emphasizes human desires and ignores Buddhism. In the film, although it is a wicked love between a snake demon and a human being, the love between Bai Suzhen and Xu Xian is praised, while the monk Fahai, who is the representative of Buddhism, is portrayed as cold and unreasonable. It is especially worth mentioning that there are several plots in the film that show that although Fa Hai, as an enlightened monk with boundless mana, has suppressed the erotic love of Bai Suzhen and Xu Xian, he is still unable to suppress his own lust. For example, when he sees the naked body of a young woman giving birth in a bamboo forest, he cannot suppress the fire in his heart, and he subsequently falls into a demonic obstacle while meditating. In another scene, when he attempts to force the green snake to help him meditate, the charming and enchanting green snake entangles him in the water. In the end, Fa Hai, although confident in his strength, is defeated. Green Snake is a movie that is more affirming of human lust while adopting a certain attitude of disapproval of the Buddhist doctrines of “abstinence from prostitution and sex.”

The film concludes with the Jinshan Temple being destroyed because of the fighting between Fa Hai and the snake demon. In this scene, monstrous waves flood the temple, Buddha statues collapse, and the monks die. The destruction of the temple symbolizes the struggle and victory of human nature. Green Snake’s theme song is also an affirmation of love and desire: “Leave a few loves in the world, and welcome thousands of changes in life. Do happy things with lovers, regardless of whether it is calamity or fate”. It advocates the persistence of the eroticism of the human world.

Running on Karma: This is a film about “reincarnation.” The protagonist was originally a young, intelligent monk with the dharma name “Liaoyin” in a Buddhist temple on Mount Wutai. Later, his friend Xiaocui is killed. The murderer, Sun Guo, hides on the mountain. Liaoyin goes to the mountain to hunt him down; however, after several days, he is unsuccessful. Instead, he frantically kills a bird he finds at the foot of the mountain and then sits under a tree for seven days and nights. Realizing the cause and effect of life, he removes his cassock, ceases to be a monk, and travels to Hong Kong. There, the former monk becomes a stripper in a nightclub where he meets Li Fengyi, a kind-hearted female police officer. Upon discovering that Li Fengyi would soon die due to indiscriminately killing Japanese soldiers in a previous life, he is moved by compassion and attempts to change this cruel cause-and-effect process to save Li Fengyi’s life. However, all of his attempts are in vain. After being pushed several times to the edge of life and death, Li Fengyi finally believes in cause and effect; furthermore, she resolves that if she is going to die, she would first do something to help the former monk. She travels to the mountain to track down Xiaocui’s murderer. Here, she is finally killed by the murderer Sun Guo. The former monk rushes up the mountain to look for Sun Guo, searching for a full 5 years. In the end, he realizes that the cause of yesterday leads to the effects of today and that no force can change this. Buddha only cares about one thing: the cause of the present. At the end of the film, he once again puts on his cassock and returns to Buddhism.

The theme of Buddhist causal reincarnation is everywhere in the film. When the police officer and dog chase the fugitive, Liaoyin sees that the dog in their previous life was a little boy who had killed a dog. Consequently, he realizes that the bad karma of the previous life will be rewarded in this life. Liaoyin also had a vision of the life-long feud waged by the Indian brothers in the film who killed each other. Because in the previous life, the senior brother was brutally murdered by the junior, in this life, he came to seek revenge and killed his sibling. Additionally, the insect that was rescued from the water by the younger brother in the previous life turned into a female teacher in this life. Additionally, despite being the heroine, because of the sins in her previous life, Li Fengyi ends up being decapitated. As such, Running on Karma is highly adherent to the Buddhist doctrine of “karma and reincarnation.” In Buddhism, karma is an iron law.

To know the past life, this life is the recipient; to know if future generations, who made this life.(Pi 2020)

Despite the complicated relationships between various types of causalities, they are bound by orderly rules without the least confusion. Each category of causes produces effects of the same type. For instance, a good cause leads to a good effect. Causes give rise to concordant effects, and effects correspond to causes. One type of cause can not give rise to another type of effect. For instance, if one sows melon seeds, one reaps the fruit of melons, and not beans. Buddhism believes that the law of causality is determined and unalterable even by the Buddhas of the successive epochs (past, present and future).(Zhao 2012)

According to Buddhist scriptures, the Buddha, who is boundless in the Dharma, has three inabilities, one of which is that he cannot change the fixed karma of life in reincarnation. Therefore, in this film, we see that Liaoyin is doomed in his quest to alter the laws of cause and effect. Because the film faithfully and completely reflects the religious principles of Buddhism’s “reincarnation of cause and effect,” Running on Karma goes against the conventional narrative and rules of Chinese cinema. At the end of the film, the beautiful and kind policewoman Li Fengyi is brutally killed by Sun Guo, and her head is removed. Furthermore, Sun Guo leaves her hanging from a tree, which is completely against the norms of Chinese film rules.

3.3. Summary

In summary, if the four sample films are sorted according to the standards of faithfully and accurately promoting Buddhism, Green Snake is the least faithful. To a certain extent, it ridicules Buddhism’s “abstinence from adultery and sex” and affirms human lust. The Shaolin Temple intends to strike a certain balance between human nature and Buddhism. It adheres to some Buddhist doctrines, but it also affirms human revenge. Running on Karma is more faithful to Buddhism. It goes against the general narrative rules of Chinese cinema to abide by the Buddhist doctrine of “causal reincarnation.” However, Shaolin represents the most complete and accurate expression of Buddhism. Because this film was supervised by the current abbot of the Shaolin Temple, Shi Yongxin, both the theme and the narrative are focused on the Buddhist doctrine of “rescue.” In Shaolin, the Buddhist doctrines are perfectly interpreted, which makes the film a model for Buddhist cinema.

4. Comments on These Four Buddhist Films

The four Buddhist films I selected were all popular films, not “niche films” made for specific groups. Therefore, these films have a wide audience and garnered a strong response in Chinese-speaking regions. Many reviews have been published on Chinese-language film review websites, which can provide data on the public acceptance of Chinese-language Buddhist films. In the Chinese-speaking regions, the two most influential film review websites are Douban Movies and Mtime, and I evaluate these film review websites to judge the reception of Chinese-language Buddhist films.

4.1. About “Douban Movie” and “Mtime”

The two most representative movie review sites in the Chinese-speaking region are “Douban Movie” and “Mtime.” They are similar to IMDB and Rotten Tomatoes, or they are the Chinese versions of IMDB and Rotten Tomatoes.

Douban Movie is a community website founded in 2006 and is currently ranked #67 in the world and #2 in social networking sites, according to Alexa. Douban Movie provides movie introductions and reviews, including movie news and ticketing services. Users can record the movies they want to watch, are watching, and have seen, as well as rate and write reviews. According to users’ tastes, Douban Movie will recommend good movies. Mtime is also a widely influential movie review website in the Chinese language. Since its founding in 2005, Mtime has focused on serving the movie industry and has become a platform to meet the needs of Chinese moviegoers and enjoy movie-watching in all aspects.

Although both Douban Movie and Mtime were created in the twenty-first century, as film review sites, Douban Movie and Mtime have included introductions to most of the films made since the birth of cinema, as well as reviews of these films by critics in the Chinese-speaking world. Some movies may be decades old, and the critic may not have seen them at that time. It is possible that he/she may have watched these films later through movie channels or purchased DVDs and wrote a review.

Neither Douban nor Mtime has a “class” label for its users, so we cannot tell at a glance the class attributes of their users. We can only infer the class attributes of Douban and Mtime users through other means, such as the educational background.

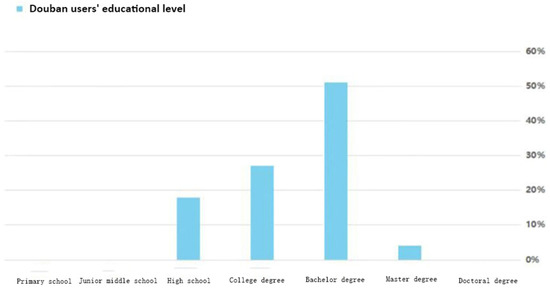

According to the 2018 statistics, the educational distribution of Douban APP users is as Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Educational level statistics of Douban APP users2.

The graph shows that the users of Douban Movie have a high school education or above, and most of them have received higher education. The situation is similar with Mtime. In the context of China’s employment situation, this group is basically distributed in enterprises and institutions as well as companies and factories and belongs to the “working class.” After the intellectual class is included in the working class, if we differentiate it from the class division, there are only the working class and peasant class in China.

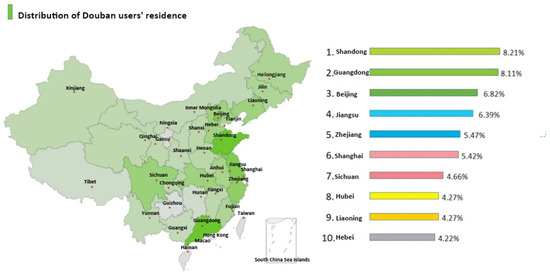

According to statistics from the China Bureau of Statistics, 87.8% of Chinese farmers are educated at junior middle school or below, and the vast majority of them have not received a high school education (Zhao 2008). Even for the “migrant workers” who have become the working class, their average education level is only 9.8 years (Tianya Finance 2022), i.e., they have only completed junior middle school education. In some western regions, this figure is even lower. For example, the average years of education of migrant workers in Qinghai Province in 2021 is nearly 8.7 years. That is, they have not even completed junior middle school education (Chen 2022). Then, comparing the education status of the user groups of Douban Movie and Mtime, i.e., all of them are in high school and above, we can conclude that the main user groups of Douban Movie and Mtime are not farmers, not even “migrant workers.” Under the current situation that Chinese society only has the working class and peasant class, after using the exclusion method to exclude the peasant class, it means that the user groups of Douban Movie and Mtime are working class. According to statistics, the user groups of Douban Movie are mainly distributed in various provinces in China, as follows. (see Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Residence statistics of Douban users3.

Judging from the user characteristics of Douban Movie and Mtime, most of their users belong to the Chinese working class, so the movie reviews published on the two sites can reflect the basic views of the Chinese working class.

4.2. Ratings of Four Buddhist Films

The ratings of the four Chinese-language Buddhist films The Shaolin Temple, Shaolin, Green Snake, and Running on Karma on Douban Movie and Mtime are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Site ratings for four Buddhist movies4.

The two film review websites have the same scoring order, indicating that the score is objective and fair and can truly reflect the working class’s acceptance of these four Chinese-language Buddhist films.

4.3. Commentary for Four Buddhist Films

The Shaolin Temple, Shaolin, Green Snake, and Running on Karma received numerous reviews on Douban Movies and Mtime, and the review angles were more diverse and scattered, covering almost all aspects from content to form. Because the research focus of this paper is to grasp the acceptance of Buddhist doctrines in the film among the working class, according to this principle, only relevant commentary texts will be selected here5.

For these four Chinese-language Buddhist films, the overall status of the film review texts basically coincided with their ratings.

4.3.1. The Shaolin Temple

Considered a classic work with pioneering and enlightening significance in Chinese-language films, upon release, The Shaolin Temple caused a huge sensation and received a flood of positive reviews. There are a lot of comments about The Shaolin Temple on Douban Movie and Mtime. Among them, film reviews involving religion mainly focus on the innovative expression of religious teachings. Many film critics have affirmed this. For example, Muran suggested that The Shaolin Temple shows a group of warrior monks full of humanity:

“they went to catch toads in order to supplement the seriously injured Jueyuan, but they were found by the old monk and punished and thought about it. Jueyuan accidentally suffocated the shepherdess. Bai Wuxia’s love dog. Just when he was about to eat dog meat after roasting, the master and his brothers suddenly appeared and began to share this taboo delicacy. Human feelings were magnified at this moment, the rules and regulations were put aside, and the film promoted a theme: no need to Sticking to the formalism of the rules and regulations, it must be people-oriented”.(Muran 2021)

Moumou believes that the film revolves around four questions: Do you drink or not? Eat meat or not? Kill or not? Do you love women?

“These are all taboos for monks, and the difficulty of choice is the driving force that drives the plot of this film. Of course, the film also answers these four questions during the development: wine, drink as much as you want, meat, eat as much as you want, Vengeance, it should be revenge, as for women, love should be loved. These answers transcend the moral framework restricted by Shaolin Temple, but they are human reactions. As long as it comes down to the starting point of human nature, the film will not be too bad”.(Moumou 2016)

Similarly, Azhi believes that The Shaolin Temple is a Shaolin Temple film that subverts tradition. In addition to clear rules and regulations, human nature is on display in the film—a challenge to a conservative, traditional culture that ignores human emotions (Azhi 2009).

However, critics also criticized some of the plot points in the film, especially those contrary to Buddhist teachings. For example, the Red Queen questioned the “reformed religious values” in the film. She proposed that:

“Master acquiesced to his apprentice to kill the frog, and then plausibly said that saving a life is better than building a seven-level pagoda, but he did not think about the life of the frog. How do you calculate it? After killing a dog, the monks sit and eat the dog meat; the warrior monks kill the enemy like hemp, aren’t those people ordinary people?”.(Red Queen 2015)

Xiao Jiang mentioned that there are several scenes of animal cruelty that are very uncomfortable to watch. One scene involves a frog’s head is removed with a knife, with the monk reasoning that saving a life is more important than building a seven-level pagoda. Another scene involved the suffocation of a dog. A further scene featured two sheep being stabbed while another had their neck broken (Xiao Jiang 2013). Although film critics have some objections to these killing behaviors against animals in the film, they fully understand and support the revenge killing of monk Jueyuan at the end of the film. One critic felt that bad people are ruthless and threatening; however, at the end of the movie, good people have good rewards, bad people have bad rewards, and evil cannot suppress the righteous, which he found quite gratifying (Huiheng 2015).

4.3.2. Shaolin

Shaolin was financed and filmed by the Shaolin Temple, and the current abbot of the Shaolin Temple, Shi Yongxin, is the film’s producer. Therefore, it has a more in-depth and accurate grasp of Buddhist doctrines. However, the implantation of the doctrines is too obvious. Accusing the film of ignoring human nature and feelings, film critics questioned and criticized it. Masheng thinks that: “In Shaolin, what we see more is the old abbot played by Hai, and the fire-headed monk played by Jackie Chan’s tireless teaching and enlightenment to Andy Lau, and more with Wu Jing and Shi Yanneng, Yu Shaoqun and other righteous monks who regard Buddhism as higher than life, make the whole film have a strong preaching meaning” (Masheng 2011). One critic also believes that even if we respect and appreciate the Buddhist doctrines espoused by Shaolin, the film suffers from a weak storyline. As such, Shaolin is largely seen as an advertisement that promotes the Shaolin Temple and Buddhism (Xifeng 2011). Additionally, another critic argued that the film’s prominent preaching of “causal punishment” is disgusting (Code 2011).

Film critics have also highlighted problems with the film’s narrative logic. Because the film uses the Buddhist doctrine of “rescue” as the psychological basis for the behavior of the characters, it is quite different from the general consensus logic of cinemagoers, namely that “good and evil are different” and “good is rewarded with good, and evil is rewarded with evil.” Shaolin’s diversion from general consensus logic has provoked the ire of many critics. For example:

“I just don’t understand why this kind of bad ending: all the elite and good people died, but the big bad people survived”.(Xiaobao 2011)

Other criticisms include: “Why does the movie have to spend an entire episode, with all the sacrifices, to educate a villain?” (Tiptoe 2011); that the film seriously lacks normal logic, namely that the story is far-fetched, the preaching is blunt, the plot arrangement is too distorted, and it is full of flaws (Wang 2011); that “the plot is extremely unreasonable, it killed me!” (Undo 2011); and “most of the subsequent plots are beyond my logical scope” (Cavalry 2011). Finally, another critic summarized:

“I don’t know what kind of concept the director wants to convey, The so-called Buddhism? Anyway, my view of good and evil was confused by him.”.(Jason 2011)

In this regard, another critic pointed out that:

“in fact, similar to the theme of religious redemption, it is not unconvincing. I really hope that in similar films, the characters’ behavior is a little bit more logical”.(Crab 2011)

4.3.3. Green Snake

Film critics have made no secret of their love for Green Snake, and many people will directly point out that they have watched this film many times. The focus of film critics’ comments on the Buddhist doctrines in Green Snake is that the film affirms the world of love through the comparison between the monk Fahai and the snake demon sisters; furthermore, they criticize the inhumanity of Buddhism. For example:

“It took eighteen hundred years to grind all desires, sincerity, grievances and loves clean, resulting in the tranquility of this Buddhist land. It is better to learn from Bai Suzhen, fall into the mortal world and be brave. To love, be happy”.(Andra 2016)

Tail pointed out that although Bai Suzhen is a demon, she is more loyal to love than people, and she goes all out without reservation. She gave everything she had just to love someone before finally being crushed under the Lei Feng Pagoda and suffering endless pain. She never doubted whether the relationship was worth it, and she would never turn her back on love (Tail 2010). Fahai is the opposite of the white and the green snakes and is an object of disgust for film critics. For example, Yu argued that Fa Hai’s heartlessness had become a symbol of sexual perversion: while he vows to kill the snake to hide his desire, he also does not allow others to enjoy the human sexuality that he himself cannot enjoy—he insisted on Xu Xian becoming a monk and broke up the mandarin ducks. His sexual repression results in his almost perverted ruthlessness, which is also justified under the guise of Buddhist abstinence (Yu 2009). Another critic believes that Fa Hai is still in a state of unrealized insight:

“If you have never experienced love and being loved, how can you talk about sex as empty and empty as sex? Talking about it is empty. As Xu Xian said, it is simply jealous. The Buddha’s intention that the film wants to express is that goodness is Buddha, not Just wear a Buddha mask and a red cassock”.(Blue Sky 2014)

Furthermore, others questioned why Fa Hai was not punished:

“When Fa Hai induced the white snake to flood the Jinshan Mountains, causing death and unforgivable sins, all the responsibility was borne by Bai Suzhen, who just wanted to find her husband. It’s not fair. The Buddha said that there are causes and effects, but Fahai, who caused all these disasters to happen, was not judged, but instead stood on the moral high ground of slaying demons and eliminating demons to suppress the white snake”.(Jiemang 2015)

Chinese film critics fully affirmed the value of love represented by the white and the green snakes. As for Fahai’s behavior, “beating the mandarin ducks with a stick,” even considering the Buddhist justice of “killing and eliminating demons,” he cannot escape his fate of being criticized and denied. This also fully reflects the values of the movie-watching public; that is, the deep and unwavering love for the world. As a film critic said: “There are emotions and desires in the human world, the world is beautiful, the demons yearn for them, and the Buddhas are also moved” (Headshots 2016).

4.3.4. Running on Karma

As a Buddhist film devoted to faithfully expressing the doctrine of “causal reincarnation,” Running on Karma promotes the doctrine as completely and deeply as possible, even at the expense of violating general film narrative rules. However, although Running on Karma accurately represents Buddhist teachings, because of its excessive use of Buddhist doctrine as the logical driving force for story progression, it is inconsistent with real life. Generally, there are many conflicts in the real world, which makes the plot difficult to understand. The audience does not agree with the film’s teachings. Negative responses toward the film were strong, and Laicalg bluntly proposed that:

“After careful consideration and chewing, I feel that the logic of the plot is a bit absurd, and the final climax is even more incomprehensible, which is really disappointing”.(Laicalg 2008)

Arch-Murder also believes that the director is trying to express profound concepts, such as cause and effect; however, the execution is poor, and it is confusing to watch (Arch-Murder 2009). Other critics raised their own doubts about the film’s “causal” logic:

Li Fengyi went to Sun Guo for good reasons, but Sun Guo killed Li Fengyi for bad reasons (Li got bad results), but in the end Sun Guo got good results because of Li Fengyi’s perception of the big guy (not being killed by the big guy). Anyway, the causal relationship is completely reversed in Sun Guo and Li Fengyi. Sun Guo planted evil causes but got good results, and Li Fengyi planted good causes but got bad results. This causal logic is completely unacceptable.(Lmovie 2011)

Another critic argued that if you follow the causal logic of Running on Karma, it makes sense that a good person should die, not because he performed bad deeds but because he performed bad deeds in his previous life (Stupid Fish 2014). Furthermore, another critic, according to the causal logic of Running on Karma:

if a good man dies in a car accident, his relatives and friends sigh and say, “What kind of sin did this cause in the past life?” Maybe it can still make people feel “God’s will is hard to know”. But if this person was killed, first of all, not to investigate the right or wrong of the murderer, but to attribute it to “he may have committed too many sins in his previous life”, which is really unreasonable. No one can accept this statement.(Cocklebur 2020)

Such a logical setting is frustrating because:

“everything can’t be taken away, only karma can be carried. No amount of good deeds can change the coming bad retribution. In the film, when Cecilia Cheung turned into a little sister undercover, the logic she put forward is not unreasonable: since God is destined to make me suffer from evil retribution, then I simply do it to the end”.(Stupid Fish 2014)

From this point of view, the film runs the risk of misleading the audience’s values, and some film critics have said:

“After watching it, I told myself that I can’t believe in Buddhism, because what Buddha told me is the cause and effect of the past and this life. And that kind of cause and effect is unfair, just like a father’s debt to his son. Two people who are completely separated should not be connected by misfortune. I only believe in cause and effect in this life because it is only one person”.(Impostor 2008)

5. How to Balance the Missionary Aspirations of Buddhism and the Popular Attributes of Film?

In summary, if the four Buddhist films are sorted according to the criteria of their fidelity to Buddhist doctrine, the most faithfully conveyed and in-depth interpretation is found in Shaolin, followed by Running on Karma, The Shaolin Temple, and then Green Snake. However, the ratings and evaluations of the four Buddhist films on Douban Movies and Mtime, the two most representative film review websites in the Chinese-speaking region, are diametrically opposed to this ordering. The highest average score is awarded to Green Snake, and the lowest rated is Shaolin.

The main reason for this striking contrast is: Although Buddhism has a long history in China, the number of Buddhists who are actually registered is still a very small minority of the population and a very low percentage of the working class. The vast majority of the Chinese working class generally believes in the simplest universal values, and they uphold value judgments and emotional tendencies supported by their daily life experiences. The working class’s understanding of Buddhism does not go beyond a surface level of Buddhist doctrines, such as the equality of all living beings, charity, etc. The working class lacks a basic understanding of Buddhist doctrine contrary to their daily life. Consequently, when Buddhist movies are overly implanted with more difficult Buddhist doctrine, it is inevitable to encounter working-class resistance.

When a certain concept can be perfectly interpreted at the level of Buddhism principles, it may not be accepted by the Working Class. As well, certain actions that are forbidden by Buddhist teachings are able to be approved by the Working Class. For example, Buddhism has a strict commandment against “killing.” This is clearly explained in the teachings of The Surangama Sutra, which we quoted in the previous section. Killing animals or people is forbidden by Buddhists. Why, then, did the critics of The Shaolin Temple criticize the killing of animals in the film but support Jue Yuan’s “revenge” for killing Wang Renze? Apparently, this is because although the killing of Wang Renze by Jue Yuan is inconsistent with the teachings of The Surangama Sutra, it is consistent with the working-class value of “good is rewarded with good and evil is rewarded with evil.” In contrast, the plot of Shaolin is also about “revenge,” in which Hou Jie gives up “revenge” in a self-sacrificing way to pursue “redemption” against the great villain Cao Man. Such a plot setting, as the teachings of the Sutra of The Past Vows of Earth Store Bodhisattva, quoted in our previous chapter suggest, is very much in line with Buddhist teachings, but it runs counter to working-class values and has therefore been criticized by critics. Similarly, although Running On Karma strictly adheres to the Buddhist doctrine of karma and reincarnation, as suggested by the teachings of the Longshu Jingtu Sutra quoted in the previous chapter, it also clearly contradicts the working-class value of “good is rewarded with good and evil is rewarded with evil,” and was therefore also questioned and criticized by critics. On the contrary, The Green Snake affirms “lust”, which is shown to be forbidden by Buddhist doctrine, a precept fully explained by the teachings of The Surangama Sutra quoted in the previous chapter, but because the real world is inherently a world of love and affection, the general public embraces lust passionately. Buddhist teachings are clearly at odds with working-class values on this point. In their review of Green Snake, critics praised the affirmation of “lust” and criticized the inhumanity of Buddhism as represented by Fahai. All this shows that the Chinese working class, as representatives of the masses, have values based on their daily life experiences, such as the belief that “good is rewarded with good and evil is rewarded with evil,” the belief in love, and the pursuit of desire fulfillment, etc. They are unable to understand and believe in Buddhist teachings as Buddhists do, both in their daily lives and in their appreciation of Buddhist movies.

Undoubtedly, Buddhist films, such as other religious films, such as Christian films, have missionary aspirations as their most basic characteristic. If a Buddhist film is not made for the purpose of purely commercial exploitation of Buddhism but with a devout heart of faith, it must have the basic demand of promoting the teachings of Buddhism. At the same time, as a film, it must meet the popular requirements of cinema and needs to be popularized, not just made for Buddhists. It is shown and disseminated to the general public. Buddhist cinema, as a special genre of subject matter, is, as its name suggests, a combination of Buddhism and cinema. Therefore, it also means that Buddhist films cannot ignore the other in order to highlight one of the two. By losing the undertones of Buddhism, a Buddhist film is not a Buddhist film. If the artistic rules of cinema are violated, Buddhist films will not be fully understood and accepted. Of course, the ideal state of Buddhist films is to combine Buddhism and cinema in an organic way, achieving a perfect balance between the missionary demands of Buddhism and the public attributes of cinema, satisfying the public’s appreciation needs, and achieving the purpose of promoting Buddhism.

In order to balance the missionary aspirations of Buddhist films with their popular attributes, Buddhist films in the Chinese-speaking region need to pay attention to at least the following points:

First of all, respect the artistic rules of cinema. A Buddhist film, such as other types of films, is, first of all, a film and then a Buddhist film. As a film, it should respect the established rules and conventions of film art. Cinema has a history of more than 100 years and has accumulated rich experience and formed stable artistic rules during its century-long creative practice. Whether at the level of audio-visual language or at the level of content expression, as well as genre style, cinema has formed its own artistic rules. The validity of these artistic rules is verified by the history of public viewing. How to make films that are more likely to be welcomed by audiences? How to tell a story to make it easier for the audience to understand? The answer to these questions has been clearly established in the history of film art. Then, Buddhist cinema, as a subcategory of cinema, should respect these artistic rules of cinema so as to make itself appear to be a pure work of cinema. Respect for the artistic rules of cinema can also give Buddhist films the desired potential for popularity. After all, the artistic rules of cinema are already embedded in the viewing experience of the audience, and respect for the artistic rules echoes the viewing expectations of the audience.

Secondly, to find the overlap between Buddhist teachings and daily life experiences. Although Buddhism has a long history in China, true Buddhists are still a minority in the country’s huge population, and few are able to study Buddhist teachings deeply, but only marginally. Therefore, for Buddhist films in the Chinese-speaking region, Buddhist teachings that are more detached from everyday experience are less appropriate, as most audiences do not fully understand them. They rely on their daily experiences when watching films. As we have seen in the reviews of The Shaolin Temple, Shaolin, Green Snake, and Running on Karma, the Buddhist teachings that are easy to understand are well understood and accepted by the critics because they fit the critics’ own daily life experience, while those that are contrary to their daily life experience are criticized and mocked by the critics. Therefore, finding the overlap between Buddhist teachings and daily life experience becomes a necessary task for Chinese Buddhist films. After all, Buddhist cinema, although it is a Buddhist film, is not a film made only for Buddhists but for the general public, and one of its very important missions is to spread the teachings among the general public, thus expanding the influence and appeal of Buddhism. This also determines that it cannot enjoy itself alone but must seek the resonance of the public.

Finally, if a Buddhist film has to choose a more difficult Buddhist doctrine for various reasons, it must fully combine human nature and human feelings to express it and make a good logical argument. Buddhist films, because of their mission, cannot completely avoid difficulties and cater to the audience. For those Buddhist films that choose to teach difficult Buddhist doctrines, they can also be welcomed by the public if they pay sufficient attention to and address the audience’s barriers to interpretation. The key is to combine human nature and human emotions and to make adequate logical arguments. Compared with superficial Buddhist teachings, difficult Buddhist teachings are generally more difficult to understand and even contradict the daily life experience of the general public. This requires Buddhist films to build extraordinary and special narrative situations and at the same time, fully integrate with daily life practices to find and lay a full psychological foundation for their unconventional behavior logic. The general audience will not view the film from the perspective of Buddhist teachings but will only use their own “human feelings” and “common sense” to sort out the plot and figure out the characters. Therefore, the expression of Buddhist teachings in films needs to be integrated with common sense and have sufficient self-justifying psychological and behavioral logic. At the same time, the teachings in Buddhist films should be explained and sorted out patiently and meticulously so that the general public, even if they are not Buddhists, can understand and appreciate the special logic of Buddhist teachings through the causes and consequences of the plot and its development. Buddhism is so profound that even Buddhists who have studied the scriptures for years cannot fully grasp it, let alone the general public who are not Buddhists! As a narrative art, the film is convenient in interpreting the doctrine of Buddhism, that is, by building a specific narrative scenario to implant and interpret the doctrine, by including the film characters who undertake the function of religious narrative into the action sequence, and by giving sufficient argumentation and display of the logic of their behavior, so that the cause and effect relationship is clearly shown, in this way, the audience can also understand the logic of the behavior of the characters in the drama. In essence, this is a process of religious persuasion, so the key lies in adequate argumentation and patient and detailed interpretation of the Buddhist doctrine, and the key points must be clearly shown and not just skimmed over.

6. Conclusions

The original intention of Buddhist intervention in cinema was to preach to a wider audience and expand the influence of Buddhism, not just appeal to practicing Buddhists, because Buddhism is not popular in Chinese-speaking areas and the working class does not fully understand the doctrines of Buddhism. When audiences accept Buddhist films, they often judge the quality of the movie according to their daily life experiences. Therefore, Chinese-language Buddhist films need to fully recognize this and try to balance the missionary aspirations of Buddhism and the popular attributes of film. Buddhist cinema must respect common sense rather than challenge it, and by doing so, ensure that Buddhist doctrine in cinema can be understood and accepted by the working class.

Given the differences in national conditions and audiences, the understanding and acceptance of Buddhist films in different countries are bound to differ. Therefore, Buddhist film studies need to form a pattern of country-specific studies. Based on the specific situation of the working class in Chinese-speaking regions, this paper finds the main problem in the dissemination of Chinese-language Buddhist films among the working class by analyzing the working-class comments on four Chinese-language Buddhist films, namely the inconsistency between Buddhist teachings and the daily life experiences of the working class. Buddhism is taught to Buddhists, while the audience of the films is the general public, and there is bound to be a difference in the understanding of Buddhism between the two. This problem is a common problem that exists not only for the working class in China but also for the working class in other countries. Studying the reception of Buddhist films among the working class in other countries, this paper can maybe form some insights.

The research has just begun on the problem of the dissemination and acceptance of Chinese-language Buddhist films among the working class in China. I intend to further refine it in a follow-up study to analyze the understanding and acceptance of female images in Buddhist films among the Chinese working class. This is a very interesting and valuable topic.

Funding

This research was funded by Huaqiao University’s Academic Project Supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [Grant Number: 17SKGC-QG08].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The meaning of “working class” has evolved over time, both in the West and in China. This will be elaborated in detail in the section on the working class in later chapters of this paper. The “Chinese working class” in this paper is a definition based on the current social structure of China, which includes the class of state and social managers, the class of enterprise managers, the class of professional and technical personnel, the class of ordinary urban workers, the class of migrant workers, the class of laid-off and unemployed workers, and the class of flexible employment. |

| 2 | The statistics are from the Tencent Index, available at https://www.jianshu.com/p/df68f60e4af4 (accessed on 6 September 2022). |

| 3 | See note 2. |

| 4 | This table was created by the author based on the ratings of these four Buddhist films by Douban Movie and Mtime. |

| 5 | All the reviews of these four films quoted in this article are from “Douban Movie” and “Mtime” and can be retrieved at https://movie.douban.com/ (accessed on 6 September 2022) and http://www.mtime.com/ (accessed on 6 September 2022) to search by movie title. No longer label them separately. |

References

- Andra. 2016. Love between Two Women. Available online: http://content.mtime.com/review/7967513 (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Arch-Murder. 2009. Running on Karma. Available online: https://movie.douban.com/subject/1300359/comments?sort=new_score&status=P (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Azhi. 2009. The Shaolin Temple. Available online: https://movie.douban.com/review/1897219/ (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Barker, Jesse. 2022. ‘Disembedded’ Buddhism in a Techno-Global Cosmology: The Case of Spike Jonze’s Film Her (2013). Journal of Global Buddhism 23: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blizek, William L. 2013. The Bloomsbury Companion to Religion and Film. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Blue Sky. 2014. Only with Love Are People. Available online: http://content.mtime.com/review/7782177 (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Burawoy, Michael. 1990. The Politics of Production. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalry. 2011. Only Two Points. Available online: http://content.mtime.com/review/5722286 (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Chen, Xingtao. 2022. Brilliant decade of Qinghai’s livelihood construction achievements. Qinghai Daily, September 16. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Francisca. 2014. The Transnational Buddhism of Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring. Contemporary Buddhism 15: 109–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Francisca. 2017. Seeing Like the Buddha: Enlightenment through Film. Albany: SUNY Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Terry Nichols, and Seymour Martin Lipset. 1991. Are social classes dying? International Sociology 6: 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocklebur. 2020. Only Cause and Effect? Available online: https://movie.douban.com/review/13088399/ (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Code. 2011. Comment on “Shaolin”. Available online: http://content.mtime.com/review/5811339 (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Crab. 2011. Shaolin. Available online: http://content.mtime.com/review/5737769 (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Cuasay, Joseph Paul L. 1997. Social and Political Struggle: Buddhism and Indigenous Beliefs in Contemporary Korean Cinema. Athens: Ohio University. [Google Scholar]

- Dahrendorf, Ralf. 2001. Class and Class Conflict in Industrial Society. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dharma Realm Buddhist Association. 2017. The Sixeh Patriarch’s Dharma Jewel Platform Sutra. Beijing: Religious Culture Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dharma Realm Buddhist Association. 2018. The Surangama Sutra. Beijing: Religious Culture Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dharma Realm Buddhist Association. 2020. Sutra of the Past Vows of Earth Store Bodhisattva. Beijing: Religious Culture Press. [Google Scholar]

- Feichtinger, Christian. 2014. Space Buddhism: The adoption of Buddhist motifs in Star Wars. Contemporary Buddhism 15: 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrmann, Arnika. 2009. Nang Nak—Ghost wife: Desire, embodiment, and Buddhist Melancholia in a contemporary Thai ghost film. Discourse 31: 220–47. [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrmann, Arnika. 2016. Ghostly Desires: Queer Sexuality and Vernacular Buddhism in Contemporary Thai Cinema. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gorz, André. 1997. Farewell to the Working Class: An Essay on Post-Industrial Socialism. London: Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Ronald. 2013. Buddhism Goes to the Movies: Introduction to Buddhist Thought and Practice. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Ronald S. 2015a. Buddhism and American Cinema. Journal of Global Buddhism 16: 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Ronald S. 2015b. Silver Screen Buddha: Buddhism in Asian and Western Film. Journal of Religion & Film 19: 4. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Ronald S., and Chanju Mun. 2019. Representing Buddhism through Mise-en-scène, Diegesis, and Mimesis: Kim Ki-duk’s Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring. International Journal of Buddhist Thought & Culture 29: 177–203. [Google Scholar]

- Headshots. 2016. Green Snake. Available online: http://content.mtime.com/review/7990922 (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Hearse, Phil. 2009. “Self-existence” or “self-activity”: Has working-class consciousness disintegrated? Marxist Studies 10: 139–42. [Google Scholar]

- Huiheng. 2015. Loyalty. Available online: https://movie.douban.com/review/7639716/ (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Impostor. 2008. One’s Cause. Available online: http://content.mtime.com/review/855562 (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- James, David E. 2001. Im Kwon-Taek: Korean National Cinema and Buddhism. Film Quarterly 54: 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jason. 2011. Insanity. Available online: https://movie.douban.com/review/4655364/ (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Jiemang. 2015. Wait a Thousand Years. Available online: http://content.mtime.com/review/7905717 (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Kumārajīva. 2020. The Diamond Sutra. Shanghai: Shanghai Classics Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Yonghai. 2010. The Vimalakirti Sutra. Beijing: Zhonghua Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laicalg. 2008. One-Sentence Review of the Movie “Running on Karma”. Available online: http://content.mtime.com/review/972941 (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Li, Peilin, and Jianwen Yu. 2021. Changes and Responses to the Composition of China’s Working Class under New Historical Conditions. Academic Monthly 53: 129–38. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Haijun. 2011. The Structural Changes of the Working Class in Contemporary China and Their Practical Implications. Ph.D. thesis, Dalian Maritime University, Dalian, China. [Google Scholar]

- Lmovie. 2011. Messed up Logic. Available online: https://movie.douban.com/review/4818504/ (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Low, Yuen Wei. 2014. Religion in Cinema: Buddhism and Taoism in Popular Films through a Jungian Lens. Ph.D. thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Nanyang, China. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, Karl, and Frederick Engels. 1972. Selected Works of Marx and Engels, vol. I. Beijing: People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Masheng. 2011. Flattery Does Not Wear, so Does Buddha. Available online: http://content.mtime.com/review/5482931 (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Moumou. 2016. Difficulty in Choosing Made Shaolin Temple. Available online: https://movie.douban.com/review/8150036/ (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Mullen, Eve. 2014. Buddhism, Children, and the Childlike in American Buddhist Films. Buddhism and American Cinema 2: 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mullen, Eve. 2016. Orientalist commercializations: Tibetan Buddhism in American popular film. Journal of Religion & Film 2: 5. [Google Scholar]

- Mun, Chanju, and Ronald S. Green. 2015. Buddhism, Uncertainty and Modernity in A Hometown in Heart. 불교문예연구 5: 155–200. [Google Scholar]

- Mun, Chanju, and Ronald S. Green. 2016. Buddhism in Korean Film during the Roh Regime 1988∼1993). 불교문예연구 6: 225–68. [Google Scholar]

- Muran. 2021. My Buddha Is Compassionate and Punishes Evil. Available online: https://movie.douban.com/review/13566361/ (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Olmsted, Marc. 2012. Nothing & Everything: The Influence of Buddhism on the American Avant-Garde 1942–1962, by Ellen Pearlman. Journal of Global Buddhism 13: 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Pi, Rixiu 皮日休. 2020. Longshu Jingtu Sutra 龙舒净土文今译. Beijing: Religious Culture Press. [Google Scholar]

- Red Queen. 2015. A Simple, Beautiful and Responsible World. Available online: https://movie.douban.com/review/7610440/ (accessed on 6 September 2022).

- Reed, Charley. 2007. Fight Club: An Exploration of Buddhism. Journal of Religion & Film 11: 5. [Google Scholar]

- Renger, Almut-Barbara. 2014. Buddhism and Film—Inter-Relation and Interpenetration: Reflections on an Emerging Research Field. Contemporary Buddhism 15: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sounsamut, Pram. 2022. Searching for Love: Junction between Thai Buddhism, Consumerism and Contemporary Thai Film. Rochester, NY. Available online: https://so06.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/Jiabu/article/view/204860 (accessed on 6 September 2022).