Abstract

The Door of the Apostles at the Cathedral of Valencia stands as a treasure of sacred Gothic architecture and sculpture. A modification to its original structure in 1599 removed the mullion and the stone image of the Virgin that is to be found today in the tympanum. However, regardless of her location, Mary Mater Dei presided over everything that was happening in the doorway. She guided those who crossed the temple’s threshold, placed as she was on the mullion so as to appear as a Porta Coeli. In addition, she was the conductor of the characters on the door such as apostles, prophets, patriarchs, virgins and angelic sonadors (sound-makers). The latter appeared playing various instruments from both profane and sacred medieval traditions. Their location in the tympanum, playing a role in the meaning of the message, showed the importance of music as a vehicle for conveying the revelation of the Incarnation of Christ.

1. Introduction

The object of study for this research is the visual program of the Door of the Apostles in the Gothic style of the Cathedral of Valencia. On the one hand, previous works explain the study of the architectural complex of the Cathedral and its parts. Sanchís y Sivera (1909, 1925, 1933) resorts to archival sources when reporting the historical, constructive and artistic origins of the metropolitan basilica. Oñate Ojeda (2012) presents a monograph on the historical-artistic scope of the Cathedral within its social and Christian context. On the other hand, authors such as Hani (1997) or Songel (2020) understand the construction of Christian temples as sacred symbolic architecture in the image of God. Serra (1991, 2012) considers questions about the technical knowledge of the medieval builder in Valencia, as well as how he approaches the urban environment at the time studied. It is important to highlight specific studies of Zaragozá (2000) and Bérchez and Gómez-Ferrer (2008). The latter reveals the characters of the repopulation, great master builders and the initial architectural plan of the Cathedral.

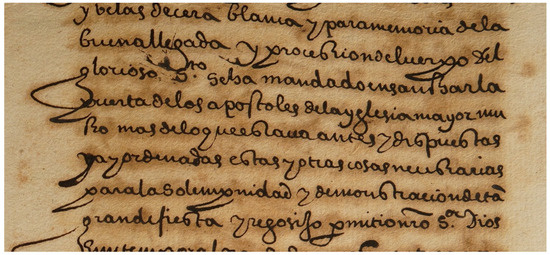

In 1599 the structure of the façade of the Apostles was formally altered and, therefore, the arrangement of the sculptures that made it up was modified. This study compiles some archival sources on the Doorway of the Apostles in order to understand what its original form was. Consequently, we provide the manuscript document that mentions the removal of the mullion from the gate of the Apostles. Furthermore, we have made a hypothetical photographic reconstruction of the façade structure before the mullion was demolished. Sources such as Lozano (2012) and the chronicler Felipe de Gauna (1926) provide important data on the Doorway of the Apostles for its physical reconstruction.

Starting from the reconstruction of the original façade, this study proposes an approximation as to the meaning of the visual program of the Doorway of the Apostles of of the Valencia Cathedral, where Mary Mater Dei surrounded by angelic musicians is represented as a gate of heaven. We do not find existing specific studies about angels’ instruments on Valencia Cathedral. Nevertheless, in this paper we establish a close relationship between music and the visual program. The theme of musical angels has been extensively studied by García Mahíques (2018), as well as Perpiñá (2018); these studies have been essential to establish conclusions, as have the Marian studies of Mocholí (2017).

2. Valencia Cathedral: Symbolic Sacred Architecture in the Image of God

Seldom did classical or baroque decorations fail to enter, conquer or hide in the Gothic skin of Valencia’s churches. As a paradigmatic example, the Doorway of the Apostles survived for the purpose of wall covering, preserving a treasure of Christian architecture and sculpture from the Middle Ages. The Doorway has survived to the current day, albeit with some changes and damage, as a monumental doorway indebted to the Gothic aesthetic trend imported from royal French lands in the first half of the 14th century: “The movement spreading [Gothic art] in the dioceses surrounding Paris […] would continue and spread in the 13th century [and] will affect neighbouring countries: England, the Empire and Spain” (Erlande-Brandenburg 1993, p. 133).

The documents that have been preserved providing news of the first construction work on the basilica (which could be related to the Doorway being studied here, from the mid-13th century until a century later) mention two master builders: A. Vitalis (1267) and Nicholas of Ancona (1304). The architecture of Valencia Cathedral, sited over the old mosque and begun around 1262—after the Christian colonisation of 1238—with the Dominican bishop Andreu de Albalat (1248–1276), came into contact with its first magister, A. Vitalis. Sanchís y Sivera (1933) states with certainty that “the first work was the Porta del Palau and the nave that it faces on the inside” (Sanchís y Sivera 1933, p. 8). “Construction was allowed to begin on the cathedral starting from this southern arm of the transept not only because of the outer presence of the Palau Doorway, but also because of the changes or shifts in the construction system […]” (Bérchez and Gómez-Ferrer 2008, p. 113). According to some studies (Zaragozá 2000), rather than being reminiscent of the Gothic or Romanesque, the Cathedral’s architecture was inspired by the Italian 13th century. In this vein, the construction between the initial part by Vitalis and the following could have been headed by the second architect, the Italian maestro Nicolás de Ancona—a name that Sanchís y Sivera (1925, p. 24) transcribed as “magisterium Nicholau de Autona”, bestowing upon him origins in French Burgundy. This maestro had worked in construction since 1304 and his mentor was Raimundo Despont (1289–1312), an authority in Ancona between 1289 and 1312. Although the chronology suggests that Ancona was the architect of the Doorway of the Apostles, the Cathedral’s preserved archive documents (ACV perg. 0440) only mention his obligation to carry out the relevant works on the Cathedral as a senior worker on it, as well as for stained glass windows, sculptures and paintings, as different studies have also pointed out. Hence, “he has been attributed the work […] from the area of the presbytery towards the naves […] with an impressive transept upon which the dome sits in the centre” (“[…] desde la zona del presbiterio hacia las naves […] con impresionante crucero sobre el que se voltea en el centro el cimborrio”) (Bérchez and Gómez-Ferrer 2008, p. 113).

[…] the breadth and moderate height of the main nave, as well as the unusually large width of the openings that connect said nave with the lateral ones, resulting in an unprecedented spatial unity in the architecture of the Crown of Aragon, are reminiscent of contemporary Italian architecture.(Zaragozá 2000, p. 66)

The result was a church with a low central nave, two generously broad aisles, a transept and an ambulatory resolved in a Gothic way, all with ornamental austerity in the Cistercian style: “The early temple, composed of an ambulatory, an outstanding transept and three stretches of naves along its length, was completed in 1356, the main altar being consecrated a year later by Bishop Vidal Blanes […]” (Vilaplana 1997, p. 5). To sum up, with regard to architectural spaciousness and length, the maestros who worked on the initial construction of the Valencian temple had in mind the concept of organising a unified space, not only as a space consecrated to liturgy but as an epicentre of congregation for the public audience of these acts of worship.

The progress of art in the Middle Ages did not involve expressing the maestro’s individual thoughts. Rather, the manifestations that we understand today as artistic were intended as an internal unity governed by a sacred and mystical value, a celestial archetype given by God the creator and regulated by a system of mathematical proportions and geometric studies that the maestro passed on to his apprentice: “You arranged everything with measurements, numbers and weights.” (Sb 11,20). The interpretation of the Book of Wisdom “became the key to the medieval vision of the world and served as the ideological basis for the constructions that were built as of the 12th century following the new Gothic language […] a composition based on numbers and measurements, both symphonic and architectural” (García Mahíques 2015, p. 861). In the West, Platonic ideas had been reaffirmed by Saint Augustine. In his treatise De Música, he likens music and architecture, in that both are based on numbers and harmony: “The builders of the Middle Ages knew the analogy between architectural proportion and musical intervals, and sometimes inscribed this analogy in stone” (Hani 1997, p. 33). The Christian temple stands as a sign and symbol of God perpetuating the sacred message through the architectural or sculptural form. Music and architecture are to share the same foundation, and the symbology of numbers devoted to Pythagorean musical harmonies and the intervallic relationship of fractions related to them is also related to geometric order and the measure of all things. The relationships between music and architecture in medieval times were based on the fact that “both were conceived as a product of mathematical proportions” (Perpiñá 2018, p. 86). In this way, Pythagorean, Platonic and the music of spheres was applied following a theological conception. “The establishment of geometric principles in art were to have a great influence on compositional aspects and their symbolism throughout the 12th and 13th centuries” (Songel 2020, p. 34). The use of geometry implied meticulousness and precision in construction; in the visible and non-visible forms, this was and is essential in any intention of architectural design.

The building’s foundation begins with its orientation, which is already in a certain way a rite, since it establishes a relationship between the cosmic order and the terrestrial order, or even between the divine order and the human order. The traditional and, we might say, universal method, since it is found wherever there is sacred architecture, was described by Vitruvius and was practised in the West until the end of the Middle Ages: the building’s foundations are oriented thanks to a gnomon that allows the two axes to be located (cardo, north-south; and decumanus, east-west).(Hani 1997, p. 28)

Out of the primary sources that exist from this period, the notebook of Villard de Honnecourt (1225–1235) gives an early mention of geometric knowledge as a construction item. This album, probably made after visits to different Gothic workshops, shows several design patterns used during the Middle Ages, that is, compositional grids that the maestros of architecture had in mind for their creations and which generated repertoires that varied according to geographical mobility. These geometric strategies were based on the shapes of the square, triangle and circle. Their symbolic geometric significance based its models on the octagram (eight-angled star polygon), like the grid traced by the dome of the Valencian Cathedral or the floor plan of the bell tower, El Miguelete, and the star of David, represented in the large rosette of the Doorway of the Apostles, known in Hebrew culture as the flower of life “whose infinitesimal extension is considered to be the representation of the universe” (Songel 2020, p. 30). In this symbolic sense of sacred architecture in the image of God, David the father of Solomon shows his son how things should be built according to God’s command: “a model of the holy tabernacle that You had prepared from the beginning” (Wis 9,8).

However, there are still certain controversies in relation to the builder’s education, oral transmission, techniques and knowledge, as well as constructive geometry (geometria fabrorum) (Serra 2012, p. 167). Professionals’ artistic mobility between states, the attraction of cities’ economic power and the protection afforded mostly by influential patrons is considered to be of vital importance for the exchange of knowledge and techniques. This occurred with the traffic among the builders of the western doorways of Nôtre Dame cathedral in Amiens and their move to the capital of Paris, hired to carry out minor works, and in the case of the builders in the Cathedral of Santa María de Regla in León who moved to the cathedral of León in Spain, while others went to work in Reims. (Williamson 1997, pp. 221–26). Specifically, at the end of the 14th century and the beginning of the 15th, Valencia established relations with the territories of the Crown of Aragon, as well as with Murcia and Andalusia (Gómez-Ferrer 1997–1998, p. 92). Despite not having any document to date to certify the authorship of the doorway of the Apostles, its formal style resembles the Gothic doorways of France. Various studies, such as the work dedicated to heraldry that appears on the cover, establish starting points for its chronology (Rodrigo 2013, p. 18), but none question the predominantly classic Gothic nature from the French school.

3. The Doorway of the Apostles at the Cathedral of Valencia

An adapted uniform façade was located in the transept, on the Gospel side and in the opposite direction towards the Portal de la Fruyta (Doorway of the Fruit), which was one of the names for the Romanesque Palau door. It opened up towards the outside, concealing another screen-façade made a priori—“it replaced another previous one, surely of Romanesque tradition” (Zaragozá 2000, p. 98)—being “built over a previous creation with a pre-existing restriction in the height of the vaults, as is evident in the difficult conjunction of the lower body with the rosette” (Esteban Chapapría 1993, p. 58).

This new construction, where architecture and sculpture merged, took a step towards the civic and religious centre of the city of Valencia, Plaza de la Seo, now Plaza de la Virgen. Furthermore, it was a doorway facing Caballeros street (the old Roman decumanus). In addition, this gate traced a connecting line towards one of the city’s main gates, the Portal dels Serrans (Serrano gate), which would between 1392 and 1398 be rebuilt as we know it today, according to the order from the junta de Murs i Valls (Walls and Fences Committee), by the mestre pedrapiquer (master stonemason) Pere Balaguer. The conception and formal inspiration for the imbrication of the Apostles’ façade with the urban space depended on the architectural models of the Île-de-France, such as Sens Cathedral and the Saint-Denis abbey church: “In Gothic man’s imagination, the cathedral was associated with an architectural reality based on […] its floor plan and its elevation, but perhaps even more with its external perception” (Erlande-Brandenburg 1993, pp. 178–79). The opulence and size of this architecture, together with the omnipresent dome (at that time comprising a single body) must have conquered the visual space of the medieval Valencian citizen. The great commercial and demographic development that the city of Valencia experienced in the late 14th century led the Municipal Consell or governing board to apply an urban policy based on improvements to show off the city’s wealth and power after events harmful to the city, including “a terrible situation experienced in Valencia during the black plague, especially aggressive in 1348” (Gómez-Ferrer 2012, p. 40).

Based on contempt for the Islamic past, still alive in many aspects of the [Valencian] urban landscape, the municipal government [the Consell] aspired to a different city with straight, wide streets, spacious squares adorned with outstanding civil and religious monuments; a clean and populous city offering the visitor a beautiful appearance.(Serra 1991, p. 74)

The basis for these types of façades was an architectural axis together with the construction of another structural element of the temple: the ambulatory or girola with chapels extending radially. In the case of Valencia, this was an original solution “where the even number of radial chapels was rounded off on the outside by a battery of niche chapels opening onto the street, surrounding the ambulatory” (Carrero 2019, p. 187).

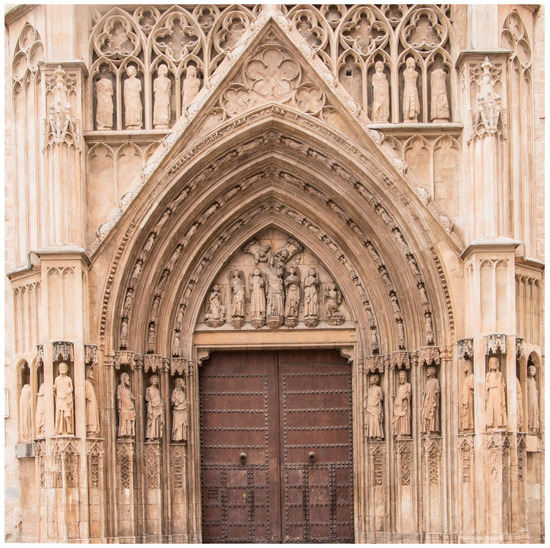

Although today the Doorway of the Apostles (Figure 1) has lost its polychromy and gilding, and has suffered damage along with imperfections on its carvings and figures, it still appears with all the grandeur with which it was conceived. It is named after the sculptures of the Apostles resting on the jambs located on both sides of the main entrance—along with other figures of local saints on the chamfers: Saint Sixtus, Saint Lawrence, Saint Valerius and Saint Vincent (Sanchís y Sivera 1909, p. 54). Today, the twelve original Apostles are resting in the Cathedral’s museum, having been replaced by resin replicas made by the sculptor José Esteve Edo. Following the pre-existing models by replacing the alternate rows of columns on the Romanesque façades, these characters formed the visual themes of the doorways as symbolic pillars of the Church, as in the case of the Cathedral of Amiens, whose central door shows an Old Testament scene, the Last Judgement, with Christ in the tympanum and the Apostles on the jambs. The name of the Valencian façade as we know it today appears in early archival documents. According to initial studies such as those by Sanchís y Sivera (1909), it is the portal dels apostols (Doorway of the Apostles) and, out of conviction, we assume it was also known thus colloquially among the people.

Figure 1.

Doorway of the Apostles, Cathedral of Valencia, author’s photograph.

This architecture is divided into two well-differentiated bodies. In the upper section, which forms part of the temple’s construction, there is a large oculus: the great Salomó, in other words a rose window, a “translucent painting” in Lampérez y Romea’s terminology. The light of celestial movement symbolically penetrates the coloured glass without causing destruction, running along a path that passes through the door until it irradiates the main altar with various multi-coloured beams. The colour, delimited in the sign of David and the rose of Jericho, is educational in conveying the message of harmony between the theological order and the cosmic order upon which the Christian temple is based. Hence, the rosette has the “character of a cosmic wheel as shown by the fact that it often has twelve spokes and that the signs of the Zodiac or the twelve Apostles are represented in the surrounding medallions […]” (Hani 1997, p. 80). The Salomó on the doorway of the Apostles, perched above the door, contains the Rose of Jericho constructed with twelve spokes. This Rose is the mother of the Messiah Jesus, son of David and son of God, and their figurative representation as mother and son presides in stone below in the doorway surrounded by musical angels, while the Apostles accompany them on the jambs.

In the lower part, a large chamfered body flares outwards, where the large ogival door opens up, composed of four increasingly bigger pointed arches that generate three archivolts full of visual themes with virgins, angels and prophets, becoming part of the antechamber to the temple, with the characteristic arrangement favoured by the Franco-Burgundian maestros who introduced French Gothic ways: “If these particular images provided the greatest emotional and spiritual appeal to the medieval viewer, the doorway sculptures were the means by which instruction and moral exegesis were conveyed” (Williamson 1997, p. 24). With its large number of sculptures arranged over a specific architecture, the Doorway of the Apostles forms a sacred rhetorical-educational theme characteristic of the Middle Ages.

Today, the visual scene on the tympanum shows modifications in the layout of the sculptures compared to their original arrangement. In its genesis, the entrance door to the temple was divided by a mullion (Figure 2) following the example of previous French models. In those, it was common to place a sculpture presiding over the entrance to the temple, which in the case of Valencia was the Virgin: “from 1200 onwards, Maria went from the tympanums to the mullions” (Mocholí 2017, p. 234). In turn, the column left two openings topped off with arches that acted as a transition. The care taken and interventions made on the doorway were constant, as reported by the Cathedral’s archive on the continuous cleaning and repainting of it: “[…] paint renovations […] Alcanyis master painter […]” (ACV sign. 1479, fol. 28r, 1431). “Martí Llobet […] cleaning the images of the Doorway of the apostles” (ACV sign. 1479, fol. 25, 1431); “But at the end of the same 16th century, the transformations in its architecture began, first by fitting wooden doors, commissioned by the Cabildo (council) on the occasion of the wedding of Felipe III in April 1599, and a few months later the mullion was removed […]” (Esteban Chapapría 1993, p. 58). Over the past century, restoration work was carried out in 1957, 1967 and 1992 by the architects Alejandro Ferrant, Joan Segura de Lago and Julián Esteban Chapapría.

Figure 2.

Hypothesis of the mullion with the Virgin, Doorway of the Apostles, Valencia Cathedral. Technical reconstruction by the author; graphic work by the architect Raquel Durán Milla.

At the end of 1599 the mullion with the stone image of the Virgin was removed from the Gothic façade of the Cathedral by order of the Patriarch and Archbishop of Valencia, Saint Juan de Ribera. The reason was to make the entrance into the temple easier for the lavish procession on 12 December 1599, transferring the remains of the young Roman martyr Saint Maurus to the Cathedral on the east of the peninsula, arriving from the Monastery of the Blood of Christ of Capuchin friars of the order of Saint Francis in Sagunto. The martyr’s remains were transferred by order of the Patriarch of Rome, exhumed from the catacomb of Pope Calixtus, through his intercessor in the Holy See, Fernando Niño de Guevara. Yet, they still could not rest in the chapel built expressly for them in the Church of Corpus Christi in Valencia, since its construction was not yet complete, so until February 1604, they were deposited in the Cathedral’s reliquary.

[…] in memory of the good arrival and procession of the glorious saint’s body, the Door of the Apostles of the main church has been ordered to be widened much more than it was before, arranging and ordering these and other things necessary for the solemnity and demonstration of such a great festivity and rejoicing.(ACCV sing. 10113, 1599) (Figure 3) Figure 3. Source: manuscript of the procession of Saint Maurus, 1599. (ACCV sing. 10113, 1599).

Figure 3. Source: manuscript of the procession of Saint Maurus, 1599. (ACCV sing. 10113, 1599).

The arrival of Saint Maurus’s remains in Valencia was celebrated with a large festive procession that attracted prominent figures to the scene such as Fernando Niño de Guevara, Baltasar de Borja, Francisco Tárrega, Sebastián de Covarrubias (ACCV sing. 10113, 1599) and more. The saint was honoured with a reception at the Serranos Towers, followed by an itinerary that wound through the main streets and points of a city carefully adorned with decorum, ephemeral architecture and a festival of sound. This transitory transformation was linked to another permanent one which, as mentioned above, altered the façade on the side of the transept that gave onto the Plaza de la Seo. The main entrance to the Cathedral in the 16th century was the Door of the Apostles. Located in the Plaza de la Seo, the Porta de la Seo (Cathedral Door, as it was also called) was strategically surrounded by centres of religious power such as the house of the Holy Inquisition, the Cathedral itself and others, as well as civic buildings such as those of the City Council (Casa de la Ciudad), the Provincial Council and the homes of significant prelates, nobility and prominent figures from the institutions of the kingdom and the city. In 1311, Jaume II authorised the Casa de la Ciudad to be moved to the Plaça de la Fruita adjacent to the Palau Doorway. It was then moved to the opposite side of the transept, at the beginning of Calle Caballeros, on the side of the Doorway of the Apostles (García Marsilla 2020).

With this reform, the future Viceroy of Valencia solved two necessary demands of the time. On the one hand, by widening the doorway he was able to achieve the desired grandeur and lavishness in the face of the danger posed by Moorish uprisings, as well as support from many nobles for the procession and for the moment the remains of the martyr would enter the Cathedral. On the other, it met the demand of the Counter-Reformation spirit that set out the guidelines for architecture noted by Carlos Borromeo: “The central entrance must be distinguishable from the others, mainly by its size and decoration, especially in a Cathedral basilica” (Borromeo 1985, p. 11). He continues by saying:

As regards the entrances and jambs of the sacred houses […] take care that they are not arched at the top; they must be different from the gates of the cities, quadrangular, as can be seen in the oldest basilicas. But they should not be lower than a humble structure, but twice as high as their latitude, as permitted by the type of architecture.(Borromeo 1985, p. 11)

With this modification to the Gothic structure, space was gained by removing the central column and the arches of the two previous entrance openings, and placing a lintel to support the tympanum. For the latter, as various researchers have discovered from the Cathedral’s archive, Vicent Leonart Esteve was sent to “lower the lintel of the doorway of the apostles” (ACV sign. 1390, fol. 54r, 1599).

Although, as we have mentioned, the wooden doors had been modified for the wedding of Felipe III to Margaret of Austria, in April 1599, the mullion of the Door of the Apostles was still in its original location according to the chronicles of Felipe de Gauna, who describes its physiognomy:

So by his order, they entered through the main door, known as of the Apostles, which is very well carved, though in the old way, with stone chiselled wonderfully, and at the top of it there was a choir of angels in the same stone with their musical instruments in their hands, and on the sides of said door were arranged the twelve apostles of Christ with the four evangelists and doctors of the Roman Catholic Church. In the middle of the same door… there was a column… that supported all… the choir of… beauty and… of Our Lady.(de Gauna 1926, p. 279)

Although there are incomplete fragments in Gauna’s text, the description notes on the one hand the column and the image of the Virgin, and on the other, the musical angels at the top of the Doorway, which the chronicler describes as a choir, possibly a conventionalised name according to sacred literature (since none of them is gesticulating by opening their mouths to sing), and as instrument players, which is their main activity in the tympanum. Similarly, he refers to other characters such as the Apostles, doctors of the Church and the four evangelists. The latter do not appear in today’s visual scene on the Doorway, raising doubts as to the veracity of the description, since no other documentary source has been found that mentions them, unless they were on the corbels of the arches to the two openings.

The Dietari or journal of Joan Pere Porcar (16th century) gives precise dates about the removal of the mullion:

Monday 15th, 1599, of November, they finished widening the opening to the Building of the Cathedral, of the Apostles […].

Thursday, on the 18th of said 1599, they began to knock down the pillar of the doorway to [the] Cathedral. And Friday, the 19th, they took away the figure of our Lady, who was on the pillar in the middle of the door, and the tiara that was on her head.(Lozano 2012, p. 100)

The tiara on top of the Virgin’s head referred to could be, on the one hand, the canopy that probably hung over the Virgin (a conventional decorative element in the figures on Gothic doorways), or on the other hand, the crown that Mary wore, an element that may originally have been made of carved stone and that was sometimes chiselled out to be replaced by a metal crown. In fact, “[…] at the end of the Middle Ages the crown was a very widespread attribute and used in numerous images of the Mother of God, regardless of the type to which they belonged” (Mocholí 2017, p. 332). In the Cathedral’s archive, there is news about this: “they put on her a crown of gilded copper made by a silversmith […] while Jesus also had a diadem, all of these pieces gilded with gold leaf […]” (García Marsilla 2020, p. 89). If the image of Mary was relocated in the tympanum, it is unlikely that it would have fitted with a crown onto the mullion due to the two angels flanking her above. However, due to a lack of documentary sources we do not know if the Virgin preserved today in the tympanum of the Doorway of the Apostles is the same as the one that rested on the mullion with her bouquet of silver-plated copper lilies in her right hand (ACV sign. 1479, folio 35, 1431). Nevertheless, the Cathedral’s archive describes the payment, on 24 November, 1599, to “Frances Torner Manya […] to support the image of Our Lady of the Doorway of the Apostles” (ACV sign. 1390, fol. 58v, 1599). Thus, if Porcar’s source is true in terms of dates, it could be referring to the placement of the same figure of the Virgin from the mullion into the tympanum six days after the mullion was knocked down. In any case, the sculptural style of the Virgin’s face, hair, clothing, etc., matches that of the figures on the façade, so it is probably the same sculpture. This is even more feasible when one takes into account the possibility that this Virgin was considered a cult image, since in the festivities of Mary she was covered with a mantilla: “[…] nine shillings for a ladder that I have bought […] for bidding to decorate the great jambs […] and to put the mantilla on the Virgin Maria at the Door of the Apostles in the annual festivities” (ACV sign. 1489, fol. 38, 1549). It is curious to observe that many of the archival sources refer to this figure by naming the Virgin and not the Virgin with Child. For example: “[…] to clean the dust off the image of the Virgin Maria, which is in the said mullion of the Doorway of the Apostles” (ACV sign. 1479, fol. 22v, 1431 in Oñate Ojeda 2012, p. 16); “[…] they took the figure of Our Lady” (Lozano 2012, p. 100); “[…] Such beauty and … of Our Lady” (de Gauna 1926, p. 279); “the image of the glorious Virgin Maria who is in the middle of the Doorway of the Apostles” (ACV sign. 1479, fol. 28, 1431 in Sanchís y Sivera 1909, p. 64).

As for the aforementioned sculptural work, the clothing of the main characters on this façade is tunics with fine, wavy folds reminiscent of the sculptures of the apostles at Sainte Chapelle in Paris. These bestow a dynamism on the figures which is accentuated even further by the expressions on their faces and their gazes raised to heaven which seem, like their arrangement, disorderly. It is interesting to note how the angel on the right of the motley Virgin is the only character dressed differently, standing erect and out of sync with the others. He is wearing a kind of dalmatic, a garment not repeated on any other angel, nor on any Apostle on the central jambs, nor on the Virgin. Likewise, on both sides of the two angels who stand flanking Mary, two iron hooks can be seen that usually served to hold up the sculptures. In 1431, orders were given to hold the figures of angels with iron due to the danger of them falling off (ACV sign. 1479, fol. 31, 1431). The figures were removed from the tympanum in order to fit hooks with iron, lead and plaster: “[…] the painters’ scaffolding where they had to lift out the images and the maestros had to be there to fix them in by putting in the iron hooks […]” (ACV sign. 1479, fol. 34bis, 1431). We do not know why two iron hooks have been left exposed and if they should have been covered up by sculptures which, hypothetically, would have been moved and relocated during the reform of 1599, when the lintel was ordered to be lowered, probably to hold up the image of Mary in the tympanum. In this latter modification, if we take into account that the lintel was higher, the images of the two angels kneeling at the ends must have been located more towards the centre, and in correlative order they would be followed by the continuous angels that would supposedly cover up the two iron holding hooks that we can see today in plain sight. However, there are no sources to corroborate this hypothesis.

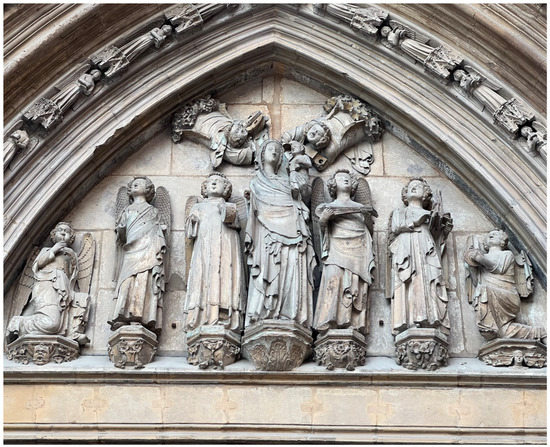

4. The Angelic Musicians on the Doorway of the Apostles

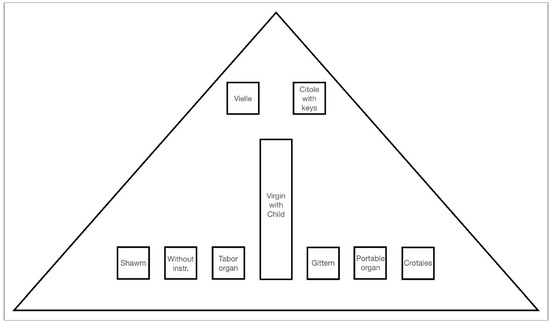

Today, we can see the image in stone of the Virgin standing with the Child in the centre of the tympanum, the latter holding an open book in his left arm, surrounded by angels playing music (Figure 4): to their right and left there are three angelic musicians either side, while above, flanking her head, there are two more, one on each side: “The 13th century marks the beginning of the success of the iconographic type of musical angel and its presence in monumental art” (Perpiñá 2018, p. 92). But the arrangement of the scene was different until 1599, as has been explained above, when the order was given to saw off the mullion, like the one in the Palau doorway and as happened with other Gothic doorways such as the one in Murcia’s Cathedral and Notre Dame, as revealed by sources from the Cathedral’s archive and which Sanchís y Sivera sheds light on (1909) (ACV sign. 1390, fol. 30r, 1599). In that image, the Virgin with Child rested on the central column “that is in the middle of the Doorway of the Apostles […]” (ACV sign. 1479, fol. 28r, 1431) and above that image, as described by the documentary sources, the musical angels or “sound-producing angels who are above said Doorway of the Apostles […]” (ACV sign. 1479, fol. 31r, 1431). In “[…] the Old Testament there is no explicit reference to the music of angels. Something similar occurs in the case of the New Testament […] there are apocryphal, liturgical and patristic sources that show that, at least as of the fourth century (and in some cases even earlier), the concept of angelic music was already present in certain Judeo-Christian sectors and in the early Church, especially in the eastern area” (García Mahíques 2018, p. 22). But there are mentions of praising God through musical instruments, as in the Book of Psalms (Ps 149, 1–3; Ps 150, 3–6). However, we cannot find an exact correspondence in the Psalm of Praise of King David (Ps 150, 3–6) with the angelic musicians’ musical instruments on the Doorway of the Apostles in the Cathedral of Valencia (Figure 5). The Psalm mentions a trumpet, a flute, a harp, a drum, a harpsichord, an organ, a zither and cymbals. Assuming that the one-armed angel on the Doorway of the Apostles, as will be explained later, is playing an instrument of medieval tradition such as a psalter, harp, rattle, triangle, etc., matching one named in the psalm, the trumpet does not appear in the Cathedral’s Doorway, nor do the cymbals as such, but rather they are finger cymbals. The drum and flute that are named in the psalm as individual instruments are considered on the Cathedral’s Doorway to be one instrument known as a tabor, which is being played by the same instrumentalist at the same time. The organ does match: it appears both in the literary source and in the visual theme of the angels, though the psalm makes no mention of the gittern or medieval guitar, the citole, the vielle or the shawm seen in the angelic hands of these characters.

Figure 4.

Tympanum over the Door of the Apostles. Author’s photograph.

Figure 5.

Diagram of the location of the instruments of the angelic musicians represented on the Door of the Apostles. By the author.

In any case, in general the musical angels’ mission was to exalt God and carry his message. There is a controversy regarding the name “choir of angels”, which it is important to note: “[…] the first Fathers of the Church conceived the angelic hordes arranged in choirs […] the arrangement in choirs refers to a circular layout whose point of reference lies in the ancient world’s cosmic conceptions. Therefore, we cannot ensure that, every time there is talk of celestial choirs, it is unequivocally referring to music” (García Mahíques 2018, pp. 30–31). That is why the musical angels in sacred literary sources appear a priori as singers, not as instrumentalists, though in the following centuries it was to be how we commonly find them in visual scenes.

The period when the Door of the Apostles was built was the musical period straddling the Ars Antiqua and the Ars Nova, that is, when musical notation systems were developing due to the need to annotate to meet the demands of compositions. The progress in polyphony would take place mainly in the ecclesiastical institution, also fostered by the creation of nobles’ private chapels as of the 14th century: “The history of Western medieval music, at least during the first millennium of our era, must necessarily be a history of Christian liturgy” (Hoppin 2000, p. 45). Sacred polyphony would need performers versed in the musical notation that had evolved. However, the equally rich instrumental repertoire would continue to be based on oral tradition to a great extent. In this sense, the minstrels were to be a fundamental professional group in medieval society, about which literary and iconographic sources reveal a great deal of information. Iconic visual arts scenes provide considerable documentation of medieval organography. The various instruments represented confirm the technical evolution of the instrumentalists, and hence the development of guilds of instrumental craftsmanship, as well as the importance of cultural exchange in developing organography and performance thanks to the mobility of the artists. The specialisation and professionalisation of musicians was increasing, partly due to this conjunction.

The master craftsmen of musical instruments documented in the Crown of Aragon throughout the 14th century and the first half of the 15th century made string instruments above all, and in some cases keyboard instruments, especially positive organs. However, there are hardly any wind instrument craftsmen listed, except in the case of the flutes created by luthiers.(Gómez Muntané 2009, p. 265)

The eight angels on the tympanum of the Cathedral of Valencia are an instrumental ensemble in the medieval tradition, which with its variety of instruments suggests sounds with a wealth of timbres. The name we can find in the cathedral’s archive to refer to the musical angels on the tympanum is “angels sonadors”, in other words, minstrels. The Trastámara seal can be seen with the particular name that it gives to the minstrel musicians when they come to be called, depending on their specialisation, “sound makers”:

Along with the chapel singers and organists, there were performers of all kinds of instruments in the service of Ferdinand I of Aragón (1412–1416) and his son Alfonso the Magnanimous (1416–1458), who generally continued to be called minstrels. However, as of the second decade of the 15th century, next to some of their names there began to appear the name of their specialisation, in which case instead of minstrels they were called “sonadors”.(Gómez Muntané 2001, p. 281)

The angels are holding a total of three aerophones, three chordophones, an idiophone, a membranophone (which is played together with one of the aerophones), and there is an angel whose instrument is no longer preserved.

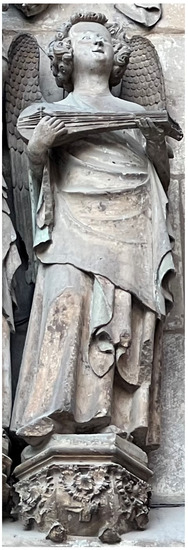

Beginning on the onlooker’s immediate right of the Virgin, the first angel is playing a gittern or guitar (Figure 6) that has been faithfully reconstructed by the specialist in medieval organography Jota Martínez. It is a chordophone with a neck, the sound box being a wooden box with no opening or sound hole. As Martínez (2019) points out, it has seven strings separated with three orders, two of which are triples that function as an accompanying bass, while the simple order is for the melody. The frets are delimited but have no tailpiece.

Figure 6.

Angelic musician with gittern on the Door of the Apostles. Author’s photograph.

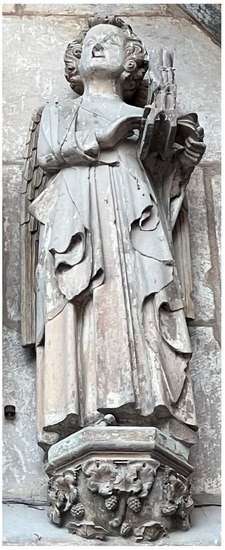

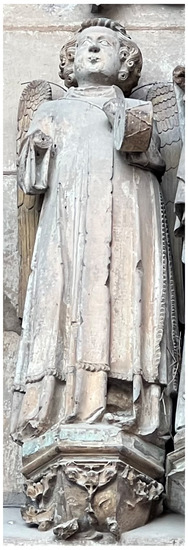

The next angel further along from the Virgin is playing a handheld portable organ held by a cord around his neck, a mechanically blown aerophone and a single set of pipes not exceeding two octaves (Figure 7). It has twelve tubes and a keyboard he is playing with his right hand while with the other one he is working the bellows, pumping air into them. It is a characteristic instrument of secular tradition that was widespread in Europe around the 12th century and highly exemplified in Spanish art as of the 13th century (Gómez Muntané 2001). The last musical angel kneeling on this side of the Virgin is playing the crotales (Figure 8), a round metal clashing idiophone struck by two symmetrical sonorous parts. The sound is created by clashing them outwards. Both discs have a triple-string grip on the back to hold each one in a hand. The Cathedral of Valencia itself preserves this very instrument in the alabaster altarpiece in the Chapel of the Holy Chalice.

Figure 7.

Angelic musician with portable organ on the Door of the Apostles. Author’s photograph.

Figure 8.

Angelic musician with crotales on the Door of the Apostles. Author’s photograph.

On the other side of the Virgin, to her immediate right, the angel is carrying a tabor, or snare drum and hand flute that were played at the same time. It is a membranophone with a free rod to rub the membrane (Figure 9). The rod that the angel must have been holding is no longer preserved. The aerophone uses a free embouchure, but the little flute has survived to the present day. It appears again on the Doorway of the Apostles in the bas-reliefs on the right below the Apostles. It was a common instrument in medieval society, and therefore widely represented. For example, we can see it on the façade of the Hospital de los Inocentes in Xàtiva, on the ogee arch.

Figure 9.

Angelic musician with tabor and flute on the Door of the Apostles. Author’s photograph.

The next angel’s arms have been severed, so we do not know what instrument he was playing; it could have been a psaltery (or zither), lyre, tambourine, open tambourine, etc., but not, apparently, an aerophone. The kneeling angel on this side is playing music with a shawm just as he is blowing into it (Figure 10). The instrument’s state of conservation is precarious. In the Cathedral of Valencia, in one of the corbels on today’s Chapel of the Holy Chalice, we can find a representation of a shawm, faithfully reconstructed by Jota Martínez. The shawm is a double-reeded aerophone made of wood with a disc at the top near the embouchure, close to the base of the bocal, which can be seen very clearly in the cathedral’s angel. Regarding the usefulness of this piece with regard to shawms, Martínez (2019) adds:

[…] it serves two purposes. On the one hand, it helps one put on and take off the instrument’s bocal without touching the reed, thereby avoiding the risk of damaging it. On the other hand, as the blowing power required is quite remarkable, the musician may rest their lips on it and thus exert greater pressure—and even use a continuous circular blowing technique.(Martínez 2019, p. 120)

Figure 10.

Angelic musician with shawm on the Door of the Apostles. Author’s photograph.

In some cases, the shawm or chirimia was played sketching out the melodic profile, together with percussion so as to accompany dances, so it is not odd to find it close to the angel playing the tabor with flute, another instrument often used for celebrations.

Flanking the Virgin overhead are two angels appearing down from two clouds with their wings now amputated. The one to the Virgin’s right is an angel playing a vielle resting on his shoulder (Figure 11). This instrument is a chordophone with handle. Its four simple strings are played with a bow. Its soundboard is a flat wooden box with two C-shaped sound holes. The waists are smooth and slightly pronounced to allow the bow to pass through. The neck, headstock and bow have not been preserved. The angel on the other side, above the infant Jesus, is playing a rare, unusual instrument in iconographic musical representations: a citole with keys (Figure 12). It is a short-necked chordophone that resonated via a wooden box tapering from the neck to the opposite end with a wedge shape, if looking at the instrument in profile. As mentioned, this instrument is peculiar in that it has five keys at the top of the neck. The citole is plucked with a plectrum or stroked with a bow. The left hand’s thumb is placed over a hole in order to grip the instrument’s neck and free the fingers to play. The citole achieved fame in the 13th century, appearing “in the doorways of churches and cathedrals built during the second half of the 13th century and subsequent decades. […] more widespread in the kingdoms of Galicia, León and Castile than in the rest of the peninsula” (Rey and Navarro 1993, p. 39). The top of the neck is no longer preserved. A priori, its organography seems to be a hybrid between a citole (in this case with holes in its sound box) and a five-key viola, though violas usually have the keys at the bottom of the neck to be easily played while stroking with the bow. One example can be found in a musical angel in the frescoes of the Capellina di Palazzo Pubblico in Siena (Italy), painted by Taddeo di Bartolo in 1408. The keys at the top of the neck generally appear in another medieval instrument, the organistrum, played with a crank at its lower end. Future investigations will shed more light on this, since it is currently very difficult to see the complete instrument without scaffolding.

Figure 11.

Angelic musician with vielle on the Door of the Apostles. Author’s photograph.

Figure 12.

Angelic musician playing citole with keys on the Door of the Apostles. Author’s photograph.

Placing the Virgin in the tympanum altered the compositional arrangement of the work. In fact, the two Apostles who regularly stand on their respective sides of the Regina, Saint Peter and Saint Paul, have been gazing into the air at no fixed point since Mary disappeared from the mullion. As for the significant quality of the work, the rhetorical function of the image of Mary in the mullion welcoming the faithful at the entrance and exit to the temple as “Mary, the gate to heaven” (Porta coeli) was to be significantly altered—though not annulled. The symbolic passing into the temple was through Mary as the gate of light between the earthly and the heavenly, by whose intermediation she lets her son Immanuel enter.

She opened anew the gate of paradise that had once been shut by Eve. Mary was often thought of as the woman who redeemed the sins of Eve, and she was understood to have “opened the gate of heaven” in two senses. In the first sense, she allowed God to descend to earth in the form of Christ, whom she carried in her womb—one is reminded of the Ave regina caelorum, which calls Mary the “gate out of whom the light of the world came forth” (“porta ex qua mundo lux est orta”). In the second sense, she became keeper of the gate through which mortals could ascend to paradise when she was crowned Queen of Heaven—here one thinks of the Alma redemptoris mater, which calls Mary the “gate of heaven” (“porta caeli”).(Rothenberg 2011, p. 36)

Maria Mater Dei is the temple itself (Mater Ecclesiae), and contains the message of the Incarnation, announced on the opposite door, the Palau Door whose iconographic theme is based on the Old Testament. The Door of the Apostles is proclaimed in analogy to the virginity of Mary who, within closed doors, allowed the Redeemer to enter and leave, as early patristic authors such as Hesychius of Jerusalem believed: “Indeed, you made the King of locked doors enter and you also made him leave. For this reason, I call you Gate, because you were the gate of the present life for the Only Begotten of God” (Pons 1994, p. 152). Mary appears carrying in her right hand the flower that underlines her immaculate purity, her virginity. In this way, Saint Roman the Melodist, Byzantine hymnographer, says in the kontakion that upon the presentation of Jesus in the temple Simeon said to Mary: “You are the closed gate, oh Mother of God; the Lord passed through you, entering and leaving, and the gate of your chastity did not open or move” (Pons 1994, p. 202). Early Hispanic Marian liturgies include antiphons on the Virgin Mary as the gateway of heaven: for example, the Breviarium cisterciense from Tarragona (Twomey 2019, pp. 189–90).

Beyond this main significance of the iconographic scene on the Doorway, music plays a prominent role in it by exalting the Regina, proclaiming Mary to be the conductor or teacher of the orchestra, regardless of her location on the Doorway. Perhaps there is some parallelism between the Doorway of the Apostles and a literary source written in the 7th century. In his Encomium Assumptionis sanctae Deiparae, Theotechnos wrote: “So that with confidence she rejoices with Him with the choirs of angels, with a multitude of prophets, with the apostles, leading the song herself, who is a teacher, prophetess and joy of virgins” (Álvarez Campos 1979–1981, pp. 377–78). Prophets of the Old Testament, apostles, kings, patriarchs and virgin martyrs are displayed on the three archivolts, jambs and gallery, while the musical angels—or angelic choir—are placed in the heavenly tympanum, all led by Mary the conductor of the choir, together with Christ on her arm. Early patriarchs like Hippolytus (3rd century) likened the prophets to musical instruments, this time conducted by God: “It was these [the prophets], in fact, who were, all of them, endowed with prophetic spirit and were honoured with dignity by the Logos himself, in agreement among themselves like musical instruments, with the Logos always within them as a plectrum, and plucked by Him they announced what God wished” (Hipólito 2012).

Bearing in mind that the documentary sources only mention angelic musicians above the Virgin, as has been confirmed in the cathedral’s archival sources, the tympanum was dedicated exclusively to the angelic-musical sculptural ensemble. The stone orchestra is playing the conventionally traditional instruments of the Middle Ages, commonly used in the festivities or celebrations of the city where civil music was interwoven with sacred music, as we know from literary sources. The fact that the musical reality in the urban environment was involved in acts of devotion, celebrations and processions meant that music played a part in religious spirituality. The rich visual scene of the musical instruments of the minstrel angels, the performers in the tympanum of the Doorway of the Apostles in the Cathedral of Valencia, reflects on the one hand the development of the appearance of musical angels together with the conceptual image of the Virgin Mary in iconographic scenes, especially as of the 13th century, and on the other, the musical tradition that defines a part of Valencian culture’s identity. The Door of the Apostles presents the message of God’s legacy as a festive celebration that rejoices to the sound of music, to the tempo that shows all that the city can offer to whoever arrives under it, and what is most important within it.

5. Conclusions

The Door of the Apostles was integrated into the urban area, giving onto the Plaza de la Seo, as an important civil and religious point in the city of Valencia. In this vein, sacred architecture and sculpture had an educational and moral purpose, where the order in construction, the cosmic-theological order and the musical order all fell into harmony so as to carry the same message: the Incarnation of Christ with the Virgin Mary in the mullion, with Mary as the gate to heaven, the guide between the earthly and the heavenly when entering the temple of God. Mary Mother of Jesus proclaimed herself as the door of light, emphasising her virginity: the light penetrates without its rays breaking up, with her letting her son enter and leave her womb. With the door’s remodelling in 1599, the rhetorical function of the image of Mary at the entrance to the church was to be altered on removing the mullion where the stone image of the Virgin rested, although this meaning is preserved even now since the figure is in the tympanum. However, regardless of her location, she was still the director of everything happening in the Doorway, guiding those who crossed the threshold. Furthermore, she was the guide of prophets, apostles, virgins and musical angels. The latter seen in the tympanum as protagonists showed the great significance of music for divine glory, habitually accompanying the conceptual image of the Virgin as of the 13th century, and represented as minstrel angels or sonadors (sound-makers), using the instruments of both urban and sacred tradition to reflect a civil society with a deep-rooted musical heritage that took part in religious spirituality.

Funding

This research was funded by Conselleria de Innovación, Universidades, Ciencia y Sociedad Digital (Generalitat Valenciana): research project “Los tipos iconográficos conceptuales de María” GV/2021/123.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

Primary Sources

Archivo de la Catedral de Valencia (ACV). Llibres d’obra sign. 1479, año 1431. Llibres d’obra sign. 1489, año 1549. Llibres d’obra sign. 1390, año 1599; pergamino nº 0440.Archivo del Corpus Christi de Valencia (ACCV). Protocolo Jaume Cristòfol Ferrer, sign. 10113, año 1599.Secondary Sources

- Álvarez Campos, Sergio. 1979–1981. Corpus Marianum Patristicum. Volumen 4-2 Traducción al español de José María Salvador González. Burgos: Ediciones Aldecoa. [Google Scholar]

- Bérchez, Joaquín, and Mercedes Gómez-Ferrer. 2008. Traer a la Memoria. La Época de Jaume I en Valencia. Valencia: Ruzafa Show ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Borromeo, Carlos. 1985. Instrucciones de la Fábrica y del Ajuar Eclesiásticos, Introducción, Traducción y Notas de Bulmaro Reyes Coria, Nota Preliminar de Elena Isabel Estrada de Gerlero, notas contextuales. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma. [Google Scholar]

- Carrero, Eduardo. 2019. La Catedral Habitada. Bellaterra: Edicions UAB. [Google Scholar]

- de Gauna, Felipe. 1926. Relación de Las Fiestas Celebradas en Valencia con Motivo del Casamiento de Felipe III. Valencia: Acción Bibliográfica Valenciana. [Google Scholar]

- Erlande-Brandenburg, Alain. 1993. La Catedral. Madrid: Akal. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban Chapapría, Julián. 1993. Algunas notas sobre la restauración de la puerta de los apóstoles de la Catedral de Valencia. (España). CSIC Informe de la Construcción 45: 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Mahíques, Rafael. 2015. Los Tipos Iconográficos de la Tradición Cristiana 1. La Visualidad del Logos. Madrid: Encuentro. [Google Scholar]

- García Mahíques, Rafael. 2018. Los Tipos Iconográficos de la Tradición Cristiana 4. Los Ángeles III. La música del cielo. Madrid: Encuentro. [Google Scholar]

- García Marsilla, Juan Vicente. 2020. Accessos a l’infinit. Les portades gòtiques valencianes i la seva iconografía. In Iauna Coeli: Portalades Gòtiques a la Corona d’Aragó. Coordinado por Francesca Español Bertrán y Joan Valero Molina. Congrés Internacional: Actes. Barcelona: IEC, pp. 81–104. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Muntané, Maricarmen. 2001. La Música Medieval en España. Kassel: Edition Reichenberger. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Muntané, Maricarmen. 2009. Música y corte a fines del Medioevo: El episodio del Sur. In Historia de la Música en España e Hispano América. De los Orígenes Hasta c. 1470. Edited by Maricarmen Gómez. Madrid: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Ferrer, Mercedes. 1997–1998. La cantería valenciana en la primera mitad del XV: El maestro Antoni Dalmau y sus vinculaciones con el área mediterránea. Anuario del Departamento de Historia y Teoría del Arte 9–10: 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Ferrer, Mercedes. 2012. El Real de Valencia (1238–1810). Historia Arquitectónica de un Palacio Desaparecido. Valencia: Institució Alfons el Magnànim. [Google Scholar]

- Hani, Jean. 1997. El Simbolismo del Templo Cristiano. Barcelona: Olañeta editor. [Google Scholar]

- Hipólito. 2012. El Anticristo. Introducción, traducción y notas de Francisco Antonio García Romero. Madrid: Ciudad Nueva. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppin, Richard H. 2000. La Música Medieval. Madrid: Akal. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, Josep. 2012. Pere Joan Porcar, Coses Evengudes en la Ciutat y Regne de València. Dietari (1585–1629). Valencia: Universitat de València. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, Jota. 2019. Instrumentos Musicales de la Tradición Medieval Española (s. V al s. XV). España: Círculo Rojo. [Google Scholar]

- Mocholí, Elvira. 2017. Las Imágenes Conceptuales de María en la escultura Valenciana Medieval. Ph.D. dissertation, Universitat de València, Valencia, España. [Google Scholar]

- Oñate Ojeda, Juan Ángel. 2012. La Catedral de Valencia. Valencia: Universitat de València. [Google Scholar]

- Perpiñá, Candela. 2018. Formación y difusión del ángel músico. In Los Tipos Iconográficos de la Tradición Cristiana 4. Los Ángeles III. La Música Del Cielo. Dirigido por Rafael García Mahíques. Madrid: Encuentro. [Google Scholar]

- Pons, Guillermo. 1994. Textos Marianos de los Primeros Siglos. Antología Patrística. Madrid: Ciudad Nueva. [Google Scholar]

- Rey, Juan José, and Antonio Navarro. 1993. Los Instrumentos de púa en España. Bandurria, Cítola y “Laúdes Españoles”. Madrid: Alianza. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo, Mateu. 2013. La heráldica en la puerta de los Apóstoles de la Catedral de Valencia. Archivo de Arte Valenciano XCIV: 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Rothenberg, David J. 2011. The Flower of Paradise. Marian Devotion and Secular Song in Medieval and Renaissance Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchís y Sivera, José. 1909. Valencia Cathedral. Guía Histórica y Artística. Valencia: Imprenta Francisco Vives Mora. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchís y Sivera, José. 1925. Maestros de obras y lapicidas valencianos en la Edad Media. Archivo de Arte Valenciano 11: 23–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchís y Sivera, José. 1933. Arquitectos y escultores de la Catedral de Valencia. Archivo de Arte Valenciano 19: 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Serra, Amadeo. 1991. La Belleza de la ciudad. El urbanismo en Valencia, 1350–1410. Ars Longa 2: 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Serra, Amadeo. 2012. Conocimiento, traza e ingenio en la arquitectura valenciana del siglo XV. Anales de Historia del Arte 22: 163–96. [Google Scholar]

- Songel, Gabriel. 2020. El Cáliz Revelado. Valencia: Tirant Humanidades. [Google Scholar]

- Twomey, Lesley K. 2019. The Sacred Space of the Virgin Mary in Medieval Hispanic Literature. From Gonzalo de Berceo to Ambrosio Montesino. Woodbridge: Tamesis Books. [Google Scholar]

- Vilaplana, David. 1997. La Catedral de Valencia. León: Turismo Everest. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, Paul. 1997. Escultura Gótica 1140–1300. Madrid: Manuales de Arte Cátedra. [Google Scholar]

- Zaragozá, Arturo. 2000. Arquitectura Gótica Valenciana Siglos XIII-XV. Tomo I. Valencia: Generalitat Valenciana. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).