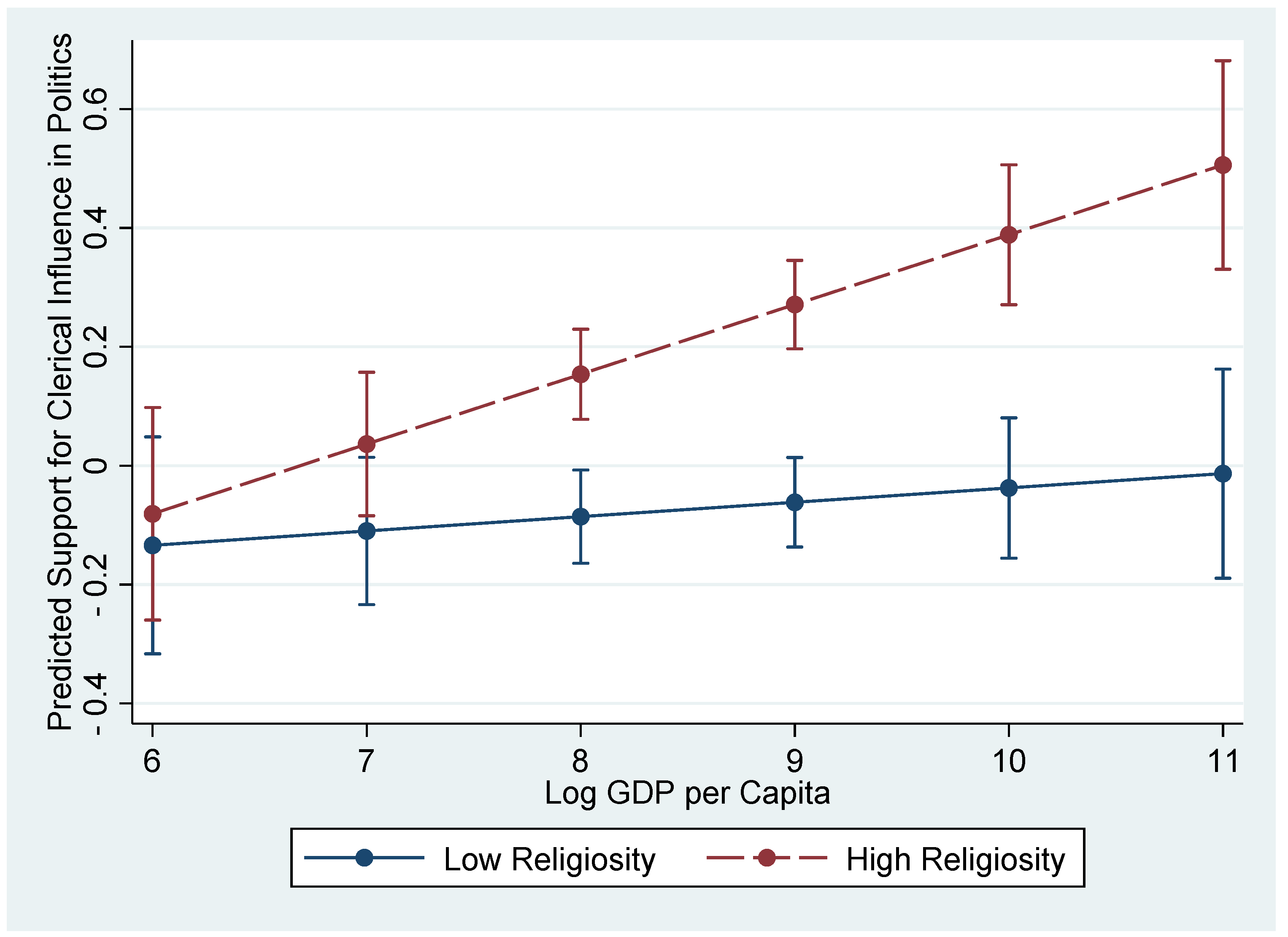

Economic Development Leads to Stronger Support among Religious Individuals for Clerical Influence in Politics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Data and Method

3.1. Dependent Variable

3.2. Key Independent Variables

3.3. Control Variables

3.4. Model

4. Result

4.1. Main Analysis

4.2. Sensitivity Analyses

5. Conclusions and Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

Appendix A

| Country | Mean Support for Clerical Influence in Politics | Log GDP Capita | Polity Index | Aggregate Religiosity | Religious Fractionalization | Having Official Religion | Gini Index | Wave |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albania | −0.249488 | 7.515152 | 5 | −0.4316816 | 0.6034439 | 0 | 0.476 | 4 |

| Algeria | 0.6881459 | 8.135804 | −3 | 0.3860891 | 0 | 1 | 0.392 | 4 |

| Australia | −0.1170668 | 10.77743 | 10 | −0.9485121 | 0.7053581 | 0 | 0.48 | 5 |

| Bangladesh | 0.0126096 | 6.205823 | 6 | 0.5979469 | 0.1509351 | 1 | 0.385 | 4 |

| Brazil | 0.2452431 | 9.142708 | 8 | 0.2500831 | 0.5659658 | 0 | 0.587 | 5 |

| Bulgaria | −0.4126491 | 8.555276 | 9 | −0.6606858 | 0.4097842 | 0 | 0.365 | 5 |

| Canada | −0.1483017 | 10.66329 | 10 | −0.4212575 | 0.712308 | 0 | 0.467 | 5 |

| Chile | 0.0982304 | 9.280486 | 9 | −0.2984607 | 0.5530643 | 0 | 0.519 | 5 |

| Taiwan region | −0.3725775 | 9.713053 | 10 | −0.8442396 | 0.6496228 | 0 | 0.321 | 5 |

| Cyprus | −0.2993729 | 10.29441 | 10 | −0.173938 | 0.5450889 | 0 | 0.477 | 5 |

| Ethiopia | −0.1212688 | 5.371356 | 1 | 0.7216944 | 0.5202475 | 0 | 0.357 | 5 |

| Finland | −0.0738791 | 10.69836 | 10 | −0.7614214 | 0.2882941 | 1 | 0.471 | 5 |

| Georgia | 0.1042932 | 7.697381 | 7 | 0.2643952 | 0.1225969 | 0 | 0.481 | 5 |

| Germany | −0.0305474 | 10.55933 | 10 | −0.5595562 | 0.660979 | 0 | 0.503 | 5 |

| Ghana | 0.1402342 | 6.94943 | 8 | 0.8515619 | 0.6065158 | 0 | 0.455 | 5 |

| Guatemala | 0.1875306 | 7.877909 | 8 | 0.7856147 | 0.5772846 | 0 | 0.5 | 5 |

| Hungary | −0.2287762 | 9.439443 | 10 | −0.7394633 | 0.6280375 | 0 | 0.513 | 5 |

| India | −0.0232628 | 6.886822 | 9 | 0.2071664 | 0.3791364 | 0 | 0.477 | 5 |

| Indonesia | 0.0453334 | 7.791687 | 8 | 0.738721 | 0.1410488 | 0 | 0.422 | 5 |

| Iran | 0.2837504 | 8.634744 | −6 | 0.2995407 | 0.0282612 | 1 | 0.442 | 5 |

| Italy | −0.08131 | 10.52479 | 10 | −0.0347184 | 0.2193928 | 0 | 0.484 | 5 |

| Japan | −0.2799127 | 10.68445 | 10 | −1.037838 | 0.5123495 | 0 | 0.423 | 5 |

| South Korea | 0.1864124 | 9.823904 | 8 | −0.4762917 | 0.7568887 | 0 | 0.324 | 5 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 0.0442265 | 6.421447 | −3 | −0.3507998 | 0.4165829 | 0 | 0.456 | 4 |

| Malaysia | 0.2281527 | 8.951677 | 3 | 0.8050887 | 0.6152129 | 1 | 0.46 | 5 |

| Mali | −0.1025772 | 6.473231 | 7 | 0.7741945 | 0.0992789 | 0 | 0.436 | 5 |

| Mexico | 0.447214 | 9.125952 | 8 | 0.2304932 | 0.4319671 | 0 | 0.478 | 5 |

| Moldova | 0.1229348 | 7.556458 | 8 | −0.2698564 | 0.1471106 | 0 | 0.565 | 5 |

| Morocco | 0.5463964 | 7.747246 | −6 | 1.034188 | 0.0116319 | 1 | 0.446 | 5 |

| New Zealand | −0.1924069 | 10.39306 | 10 | −1.023207 | 0.6812041 | 0 | 0.464 | 5 |

| Norway | −0.6790965 | 11.37089 | 10 | −1.065837 | 0.5003922 | 1 | 0.455 | 5 |

| Peru | 0.3365832 | 8.189522 | 9 | 0.1235698 | 0.4505062 | 0 | 0.548 | 5 |

| Philippi | −0.1788049 | 7.389787 | 8 | 0.6317183 | 0.4589064 | 0 | 0.476 | 4 |

| Poland | −0.4140203 | 9.170604 | 10 | 0.3127929 | 0.1027375 | 0 | 0.519 | 5 |

| Romania | −0.3540958 | 8.770152 | 9 | 0.1683259 | 0.2386505 | 0 | 0.423 | 5 |

| Rwanda | 0.1510123 | 6.074065 | −3 | 0.7227616 | 0.6145089 | 0 | 0.533 | 5 |

| Viet Nam | 0.00792 | 6.86218 | −7 | −0.9883463 | 0.6142151 | 0 | 0.41 | 5 |

| Slovenia | −0.137392 | 9.960676 | 10 | −0.7220406 | 0.4802308 | 0 | 0.396 | 5 |

| South Africa | 0.1847639 | 8.775257 | 9 | 0.3792233 | 0.5876378 | 0 | 0.683 | 5 |

| Zimbabwe | 0.4284406 | 7.329317 | −6 | 0.5938547 | 0.548572 | 0 | 0.525 | 4 |

| Spain | −0.2096974 | 10.3237 | 10 | −0.9483094 | 0.3132815 | 0 | 0.453 | 5 |

| Sweden | −0.3225363 | 10.80094 | 10 | −1.191893 | 0.4675993 | 0 | 0.468 | 5 |

| Thailand | 0.1050583 | 8.340572 | 9 | 0.4598396 | 0.0585343 | 0 | 0.471 | 5 |

| Trinidad | 0.2179921 | 9.499336 | 10 | 0.4009708 | 0.6997756 | 0 | 0.441 | 5 |

| Turkey | −0.0785363 | 9.106031 | 7 | 0.1369063 | 0.0206156 | 0 | 0.451 | 5 |

| Uganda | 0.1789983 | 6.259138 | −4 | 0.6706904 | 0.6423087 | 0 | 0.455 | 4 |

| Ukraine | 0.0538353 | 7.885588 | 6 | −0.5758852 | 0.5165529 | 0 | 0.238 | 5 |

| Tanzania | −0.1354793 | 6.214129 | −1 | 0.7967934 | 0.7164364 | 0 | 0.4 | 4 |

| United States | 0.4584492 | 10.764 | 10 | −0.1355668 | 0.7461435 | 0 | 0.488 | 5 |

| Burkina | −0.1241264 | 6.303274 | 0 | 0.7355806 | 0.6025797 | 0 | 0.482 | 5 |

| Uruguay | 0.0707868 | 9.041828 | 10 | −0.9799876 | 0.577112 | 0 | 0.532 | 5 |

| Venezuela | 0.2546787 | 9.451435 | 8 | 0.104834 | 0.4882758 | 0 | 0.445 | 4 |

| Serbia | 0.1905078 | 8.430487 | 6 | −0.3047742 | 0.217977 | 0 | 0.529 | 5 |

| Zambia | 0.4190331 | 6.982711 | 5 | 0.6077806 | 0.6510764 | 1 | 0.587 | 5 |

| Dependent Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key independent variables | |||

| Importance of God/Allah/Buddha… | −0.111 *** (0.025) | ||

| Religious service attendance | −0.099 * (0.040) | ||

| Importance of religion | −0.342 *** (0.084) | ||

| Logged GDP per capita | −0.085 * (0.038) | 0.009 (0.046) | −0.089 (0.057) |

| Importance of God/Allah/Buddha …* GDP | 0.016 *** (0.003) | ||

| Religious service attendance * GDP | 0.019 *** (0.005) | ||

| Importance of religion * GDP | 0.051 *** (0.009) | ||

| Individual level controls | |||

| Age | −0.000 (0.000) | −0.000 (0.000) | −0.001 * (0.000) |

| Women | 0.019 * (0.008) | 0.020 * (0.008) | 0.016 * (0.008) |

| Education | −0.063 *** (0.012) | −0.065 *** (0.012) | −0.063 *** (0.012) |

| Income | −0.003 (0.002) | −0.006 *** (0.002) | −0.003 (0.002) |

| Religious affiliation | |||

| Protestant | 0.112 *** (0.016) | 0.062 *** (0.017) | 0.100 *** (0.016) |

| Catholic | 0.098 *** (0.016) | 0.055 *** (0.017) | 0.089 *** (0.016) |

| Orthodox | 0.107 *** (0.027) | 0.077 ** (0.028) | 0.107 *** (0.027) |

| Jew | −0.005 (0.067) | −0.085 (0.066) | −0.029 (0.067) |

| Muslim | 0.181 *** (0.023) | 0.157 *** (0.024) | 0.179 *** (0.023) |

| Buddhist | 0.160 *** (0.030) | 0.112 *** (0.030) | 0.125 *** (0.031) |

| Hindu | 0.082 * (0.039) | 0.051 (0.039) | 0.082 * (0.039) |

| Other religions | 0.102 *** (0.023) | 0.072 ** (0.024) | 0.083 *** (0.023) |

| Religious none (reference) | |||

| Country level controls | |||

| Polity index | −0.012 (0.010) | −0.011 (0.012) | −0.012 (0.015) |

| Aggregate religiosity | 0.151 * (0.072) | 0.210 * (0.090) | 0.221 * (0.110) |

| Religious fractionalization | 0.123 (0.172) | 0.110 (0.209) | 0.210 (0.260) |

| Official religion | 0.005 (0.112) | 0.060 (0.139) | 0.005 (0.174) |

| Gini index | −0.022 (0.505) | 0.851 (0.633) | 0.975 (0.772) |

| Wave 5 (Wave 4 as reference) | 0.147 (0.110) | −0.015 (0.131) | 0.147 (0.164) |

| Intercept | 0.365 (0.342) | −0.680 (0.420) | −0.128 (0.523) |

| Variance components | |||

| Residual | 0.913 (0.005) | 0.908 (0.005) | 0.911 (0.005) |

| Intercept variance | 0.049 (0.013) | 0.091 (0.019) | 0.129 (0.030) |

| Slope variance | 0.001 (0.000) | 0.002 (0.000) | 0.010 (0.002) |

| Individual N | 61859 | 61043 | 61871 |

| Dependent Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key independent variables | |||

| Individual religious affiliation | |||

| Protestant (reference) | |||

| Catholic | −0.001 (0.014) | −0.039 (0.036) | −0.005 (0.020) |

| Orthodox | −0.004 (0.026) | 0.006 (0.063) | 0.044 (0.053) |

| Jew | −0.122 (0.067) | 0.046 (0.140) | −0.149 (0.112) |

| Muslim | 0.071 *** (0.022) | 0.081 (0.064) | 0.044 (0.065) |

| Buddhist | 0.062 * (0.031) | −0.019 (0.063) | 0.023 (0.050) |

| Hindu | −0.009 (0.039) | −0.078 (0.069) | −0.036 (0.055) |

| Other religions | 0.025 (0.023) | −0.026 (0.058) | −0.018 (0.042) |

| Religious none | −0.037 * (0.017) | −0.062 (0.049) | −0.021 (0.035) |

| Country Catholic size | −0.014 (0.128) | ||

| Country Muslim size | −0.263 (0.150) | ||

| Catholic * Country Catholic size | 0.109 (0.085) | ||

| Orthodox * Country Catholic size | −0.154 (0.259) | ||

| Jew * Country Catholic size | −0.518 (0.416) | ||

| Muslim * Country Catholic size | −0.050 (0.239) | ||

| Buddhist * Country Catholic size | 0.284 (0.309) | ||

| Hindu * Country Catholic size | 0.314 (0.360) | ||

| Other religions * Country Catholic size | 0.014 (0.162) | ||

| Religious none Country Catholic size | 0.143 (0.119) | ||

| Catholic * Country Muslim size | 0.094 (0.129) | ||

| Orthodox * Country Muslim size | −0.357 (0.220) | ||

| Jew * Country Muslim size | 0.422 (0.336) | ||

| Muslim * Country Muslim size | 0.146 (0.152) | ||

| Buddhist * Country Muslim size | 0.043 (0.210) | ||

| Hindu * Country Muslim size | 0.087 (0.180) | ||

| Other religions * Country Muslim size | 0.012 (0.188) | ||

| Religious none * Country Muslim size | −0.020 (0.182) | ||

| Individual level controls | |||

| Individual religiosity | 0.183 *** (0.006) | 0.182 *** (0.006) | 0.182 *** (0.006) |

| Age | −0.001 * (0.000) | −0.000 (0.000) | −0.000 (0.000) |

| Women | 0.007 (0.008) | 0.008 (0.008) | 0.008 (0.008) |

| Education | −0.057 *** (0.012) | −0.055 *** (0.012) | −0.055 *** (0.012) |

| Income | −0.004 (0.002) | −0.003 (0.002) | −0.003 (0.002) |

| Country level controls | |||

| Log GDP per Capita | 0.056 (0.030) | 0.054 (0.031) | 0.062 * (0.029) |

| Polity index | −0.020 ** (0.008) | −0.020 * (0.008) | −0.024 ** (0.008) |

| Aggregate religiosity | 0.018 (0.060) | 0.022 (0.060) | 0.055 (0.059) |

| Religious fractionalization | 0.122 (0.137) | 0.276 (0.144) | 0.168 (0.148) |

| Official religion | 0.042 (0.091) | 0.074 (0.094) | 0.086 (0.091) |

| Gini index | 0.665 (0.420) | 0.465 (0.423) | 0.360 (0.408) |

| Wave 5 (Wave 4 as reference) | 0.021 (0.085) | 0.054 (0.087) | 0.043 (0.082) |

| Intercept | −0.685 * (0.279) | −0.684 * (0.284) | −0.590 * (0.283) |

| Variance components | |||

| Residual | 0.913 (0.005) | 0.907 (0.005) | 0.907 (0.005) |

| Intercept variance | 0.041 (0.008) | 0.036 (0.008) | 0.032 (0.007) |

| Catholic variance | 0.003 (0.002) | 0.003 (0.002) | |

| Orthodox variance | 0.023 (0.017) | 0.014 (0.012) | |

| Jew variance | 0.052 (0.047) | 0.055 (0.052) | |

| Muslim variance | 0.043 (0.016) | 0.042 (0.016) | |

| Buddhist variance | 0.007 (0.012) | 0.005 (0.010) | |

| Hindu variance | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | |

| Other religions variance | 0.023 (0.015) | 0.022 (0.015) | |

| Religious none variance | 0.025 (0.009) | 0.028 (0.009) | |

| Individual N | 59,951 | 59,951 | 59,951 |

References

- Berger, Peter. 2014. The Many Altars of Modernity. Boston: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker, Rogers. 2015. Religious Dimensions of Political Conflict and Violence. Sociological Theory 33: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, David. 2015. Demanding the Divine? Explaining Cross-National Support for Clerical Control of Politics. Comparative Political Studies 49: 357–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, Matthew, and Ola Listhaug. 2006. Public Opinion on the Role of Religion in Political Leadership: A Multi-Level Analysis of Sixty-Three Countries. Japanese Journal of Political Science 7: 251–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, Jose. 1994. Public Religions in the Modern World. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, Jose. 2006. Rethinking Secularization: A Global Comparative Perspective. Hedgehog Review 8: 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, John L. 1998. Islam and Politics. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, Jonathan, and Ephraim Tabory. 2008. Contemporary Evidence regarding the Impact of State Regulation of Religion on Religious Participation and Belief. Sociology of Religion 69: 245–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorski, Philip. 2017. Why Evangelicals Voted for Trump: A Critical Cultural Sociology. American Journal of Cultural Sociology 5: 338–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halman, Loek, and Erik van Ingen. 2015. Secularization and Changing Moral Views European Trends in Church Attendance and Views on Homosexuality, Divorce, Abortion, and Euthanasia. European Sociological Review 31: 616–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hout, Michael, and Claude S. Fischer. 2002. Why More Americans Have No Religious Preference: Politics and Generations. American Sociological Review 67: 165–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, Ronald, and Wayne E. Baker. 2000. Modernization, Cultural Change, and the Persistence of Traditional Values. American Sociological Review 65: 19–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, Ronald F., Christian Haerpfer, Alejandro Moreno, Christian Welzel, Kseniya Kizilova, Jaime Diez-Medrano, Marta Lagos, Poppa Norris, Eduard Ponarin, and Bi Puranen. 2014. World Values Survey: All Rounds—Country-Pooled Datafile Version. Madrid: Jd Systems Institute. Available online: http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/wvsdocumentationwvl.jsp (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Jacoby, William G. 2014. Is There a Culture War? Conflicting Value Structures in American Public Opinion. American Political Science Review 108: 754–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakoç, Ekrem, and Birol Başkan. 2012. Religion in Politics: How Does Inequality Affect Public Secularization. Comparative Political Studies 45: 1510–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liefbroer, Aart C., and Arieke J. Rijken. 2019. The Association Between Christianity and Marriage Attitudes in Europe. Does Religious Context Matter? European Sociological Review 35: 363–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckmann, Thomas. 1967. The Invisible Religion. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Minarik, Pavol. 2014. Employment, Wages, and Religious Revivals in Post-communist Countries. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 53: 296–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, Seyyed Vali Reza. 2001. Islamic Leviathan: Islam and the Making of State Power. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2011. Sacred and Secular. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Philpott, Daniel. 2007. Explaining the Political Ambivalence of Religion. American Political Science Review 101: 505–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Christian. 1996. Corrective a Curious Neglect, or Bringing Religion Back. In Disruptive Religion: The Force of Faith in Social Movement Activism. Edited by Christian Smith. New York: Routledge, pp. 13–45. [Google Scholar]

- Solt, Frederick. 2019. Measuring Income Inequality across Countries and over Time: The Standardized World Income Inequality Database. SWIID Version 8.2. Available online: https://fsolt.org/swiid/ (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Stark, Rodney, and Roger Finke. 2000. Acts of Faith: Explaining the Human Side of Religion. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tessler, Mark. 2015. Islam and Politics in the Middle East: Explaining the Views of Ordinary Citizens. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, Andrew L., Samuel L. Perry, and Joseph O. Baker. 2018. Make America Christian Again: Christian Nationalism and Voting for Donald Trump in the 2016 Presidential Election. Sociology of Religion 79: 147–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, Carrie R. 2011. The Muslim Brotherhood: Evolution of an Islamist Movement. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins-Laflamme, Sarah. 2016. Secularization and the Wider Gap in Values and Personal Religiosity between the Religious and Nonreligious. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 55: 717–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, Anne. 2017. Political Islam in Tunisia: The History of Ennahda. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Woodberry, Robert D., and Christian S. Smith. 1998. Fundamentalism Et Al.: Conservative Protestants in America. Annual Review of Sociology 24: 25–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Fenggang. 2005. Lost in the Market, Saved at McDonald’s: Conversion to Christianity in Urban China. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 44: 423–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean/Percent | Standard Deviation | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | ||||

| Support for clerics’ influence in politics | 0.035 | 1.000 | −1.273 | 2.802 |

| Key Independent variables | ||||

| Individual religiosity | 0.035 | 0.990 | −2.110 | 1.185 |

| Logged GDP per capita | 8.525 | 1.514 | 5.371 | 11.371 |

| Individual level controls | ||||

| Age | 40.409 | 16.154 | 15 | 97 |

| Women | 0.504 | 0.500 | 0 | 1 |

| College education | 0.145 | 0.352 | 0 | 1 |

| Income | 4.676 | 2.292 | 1 | 10 |

| Religious affiliation | ||||

| Protestant | 0.184 | 0.388 | 0 | 1 |

| Catholic | 0.241 | 0.428 | 0 | 1 |

| Orthodox | 0.115 | 0.319 | 0 | 1 |

| Jew | 0.004 | 0.060 | 0 | 1 |

| Muslim | 0.213 | 0.410 | 0 | 1 |

| Buddhist | 0.046 | 0.209 | 0 | 1 |

| Hindu | 0.025 | 0.156 | 0 | 1 |

| Other religions | 0.050 | 0.217 | 0 | 1 |

| Religious none (reference) | 0.122 | 0.327 | 0 | 1 |

| Country level controls | ||||

| Polity index | 5.958 | 5.289 | −7 | 10 |

| Aggregate religiosity | 0.032 | 0.624 | −1.192 | 1.034 |

| Religious fractionalization | 0.438 | 0.230 | 0 | 0.757 |

| Official religion | 0.159 | 0.366 | 0 | 1 |

| Gini index | 0.469 | 0.768 | 0.238 | 0.683 |

| Wave 5 (Wave 4 as reference) | 0.863 | 0.343 | 0 | 1 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Key independent variables | ||

| Individual religiosity | 0.149 *** (0.021) | −0.253 * (0.108) |

| Logged GDP per capita | 0.073 * (0.031) | 0.071 * (0.031) |

| Individual religiosity * GDP | 0.047 *** (0.012) | |

| Individual level controls | ||

| Age | −0.001 ** (0.000) | −0.001 ** (0.000) |

| Women | 0.008 (0.008) | 0.008 (0.008) |

| College education | −0.058 *** (0.012) | −0.058 *** (0.012) |

| Income | −0.003 (0.002) | −0.003 (0.002) |

| Religious affiliation | ||

| Protestant | 0.010 (0.018) | 0.009 (0.018) |

| Catholic | 0.007 (0.017) | 0.006 (0.017) |

| Orthodox | 0.029 (0.028) | 0.027 (0.028) |

| Jew | −0.106 (0.068) | −0.107 (0.068) |

| Muslim | 0.089 *** (0.024) | 0.089 *** (0.024) |

| Buddhist | 0.081 ** (0.031) | 0.080 * (0.031) |

| Hindu | −0.007 (0.040) | −0.009 (0.040) |

| Other religions | 0.007 (0.024) | 0.004 (0.024) |

| Religious none (reference) | ||

| Country level controls | ||

| Polity index | −0.016 * (0.008) | −0.016 * (0.008) |

| Aggregate religiosity | 0.053 (0.062) | 0.053 (0.061) |

| Religious fractionalization | 0.157 (0.143) | 0.163 (0.142) |

| Official religion | 0.067 (0.095) | 0.069 (0.094) |

| Gini index | 0.851 (0.435) | 0.836 (0.432) |

| Wave 5 (Wave 4 as reference) | −0.037 (0.089) | −0.035 (0.088) |

| Intercept | −0.881 ** (0.290) | −0.857 ** (0.288) |

| Variance components | ||

| Residual | 0.902 (0.005) | 0.901 (0.005) |

| Intercept variance | 0.044 (0.009) | 0.043 (0.009) |

| Slope variance | 0.022 (0.005) | 0.017 (0.004) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, Y. Economic Development Leads to Stronger Support among Religious Individuals for Clerical Influence in Politics. Religions 2022, 13, 1053. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111053

Lu Y. Economic Development Leads to Stronger Support among Religious Individuals for Clerical Influence in Politics. Religions. 2022; 13(11):1053. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111053

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Yun. 2022. "Economic Development Leads to Stronger Support among Religious Individuals for Clerical Influence in Politics" Religions 13, no. 11: 1053. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111053

APA StyleLu, Y. (2022). Economic Development Leads to Stronger Support among Religious Individuals for Clerical Influence in Politics. Religions, 13(11), 1053. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111053