Abstract

The region of the Luofu Mountains in Guangdong, China, has long been a Daoist sacred place for centuries. In the Daoist sacred geographic system “Dongtian Fudi” (Grotto-Heavens and Blissful Lands), the Luofu Mountains are ranked as the seventh “Major Grotto-Heaven”, standing as an influential site for the practice Daoist immortals. Due to a sense of local pride and responsibility, the Guangdong literatus Han Huang (active approx. 1600–1639) compiled an important gazetteer named Luofu yesheng (The Unofficial Gazetteer of the Luofu Mountains) in 1639, which is largely underexplored. By investigating the texts and images within Luofu yesheng and by comparing them with other gazetteers of the Luofu Mountains compiled during the Ming dynasty, this article discovers that Han Huang compiled such a gazetteer and demonstrated the religious sacredness of the Luofu Mountains to advocate for recognition of their status as a grotto-heaven and by imaginatively reconstructing their lost religious sites in Luofu yesheng’s texts and images.

1. Introduction

Located in Boluo 博羅 County, Huizhou 惠州, Guangdong 廣東 Province, China’s Luofu Mountains (Luofu shan 羅浮山) have stood as a Daoist sacred site for centuries. Ever since the Zhou dynasty (c. 1046–256 BCE), the region of the Luofu Mountains has been a holy site for religious practitioners; furthermore, since the Tang (618–907) and Song (960–1279) dynasties, the region of the Luofu Mountains has been seen as a natural, cultural, and religious landmark located in Guangdong.1 In the Daoist sacred geographic system of “Grotto-Heavens and Blissful Lands” (dongtian fudi 洞天福地), Luofu is ranked seventh of the “Ten Major Grotto Heavens” (Shida dongtian 十大洞天) and are referred to as the “Grotto-heaven of Vermillion Brightness Shining Truth” (Zhuming yaozhen tian 朱明耀真天).2

During the late Ming (1368–1644) and early Qing (1644–1911) dynasties, Han Huang 韓晃 (1600 juren 舉人), a native literatus of Boluo, took the literary name (hao 號) “Woodcutter of the Seventh Grotto-heaven” (Diqi Dongtian qiaoke 第七洞天樵客) and compiled an important gazetteer of the Luofu Mountains with landscape illustrations, Luofu yesheng 羅浮野乘 (The Unofficial History of the Luofu Mountains, henceforth Yesheng),3 which is the core research material of this article.4 To Han Huang, reading and collecting the literary works and historical accounts of the Luofu Mountains is “refreshing for the heart and soul” (xinhun xidi 心魂洗滌).5 As a native literatus in Boluo, Han Huang, as a matter of local pride and responsibility, affirmed and documented the status of Luofu as a sacred region that accomodated numerous eminent literati and Daoist immortals.6

The Luofu Mountains have long been characterized by local writing and image-making in terms of their Daoist sacredness, and Yesheng has played an important role in the transmission of the Luofu Mountains’ significance in both literary and artistic traditions in later times. The early Qing painter Shitao 石濤 (1642–1707), in the late stage of his life, painted an album of the Luofu Mountains after the images from Yesheng, such as the Yunmu Feng 雲母峰 and Shangjie Sanfeng 上界三峰, due to his lasting aspiration to visit Luofu (Hay 1989, p. 405). Also, in Luofu shan zhi huibian 羅浮山志會編 (Combined Gazetteer of the Luofu Mountains, henceforth Huibian), the most comprehensive gazetteer of the Luofu Mountains, Luofu yesheng is listed as one of the important references.7 Additionally, in the early Qing, when the literati Wu Zhenfang 吳震方 (1679 jinshi 進士) missed the chance to be in Luofu due to heavy rain, he viewed Yesheng as an alternative way to “travel” among the Luofu Mountains. Later literati’s references as such indicate that Luofu yesheng can be seen as important material for learning about the Luofu Mountains.8

By investigating and comparing the texts and images within Yesheng with other gazetteers of the Luofu Mountains compiled during the Ming dynasty, this article explores why and how Han Huang, a local literatus in Boluo County, compiled Yesheng and demonstrated Luofu’s sacredness. Building on previous gazetteers, Yesheng supplements the historiography of previous writings about Luofu and revives the religious sacredness of the Luofu Mountains during the Ming dynasty by recording information about Luofu at its prime in texts and images delineating religious sites. In other words, applying Mircea Eliade’s theory, this article explores how Han Huang managed to imaginatively keep Luofu as a sacred space which is differentiated from a “profane space” (Eliade 1987, p. 15).

This article attempts to discover how Han Huang understood and interpreted the Luofu Mountains through the lens of four aspects, which are, respectively, discussed in four sections. Section 2 of this article describes the contents of Yesheng and investigates its creation, elucidating how its author drew upon previous gazetteers on the Luofu Mountains in that process. Section 3 examines Luofu’s reputation as a grotto-heaven, a Daoist sacred place, and it considers how such reputation is demonstrated in Yesheng. Section 4 scrutinizes Han Huang’s introduction to Yesheng and explains how, according to Han Huang, Yesheng is a contribution to the writing on the Luofu Mountains. Finally, Section 5 argues that although it is a gazetteer of a well-recognized Daoist sacred site, Yesheng should be considered a product of China’s syncretism of different traditions of belief among Buddhism and Confucianism.9 By comparing related sections in Yesheng with other historical documents regarding specific religious sites in the Luofu Mountains, this section investigates how Yesheng presents idealized images of the Luofu Mountains by reconstructing religious sites that had already been destroyed before Han Huang’s lifetime.

2. The Formation of Luofu Yesheng

2.1. The Content

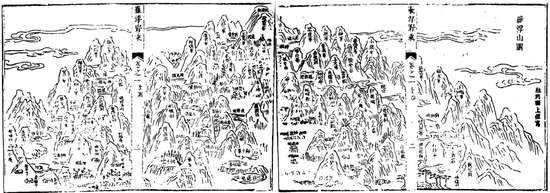

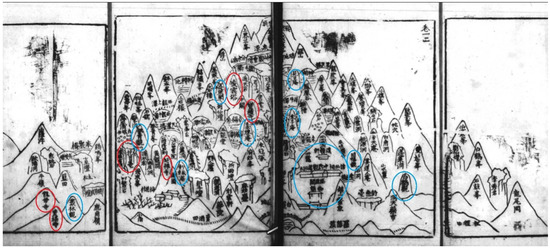

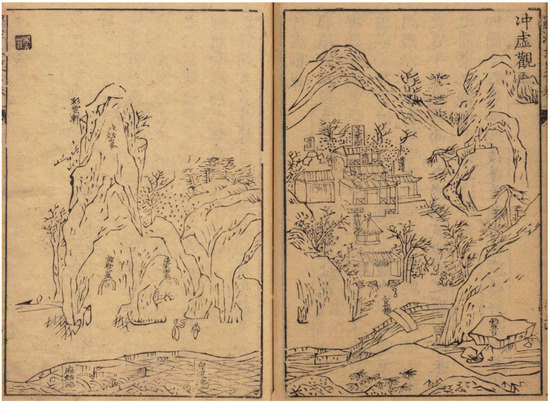

Han Huang passed the provincial civil service examination and was made juren in 1600.10 The government appointed him magistrate of Qingtian County in Zhejiang Province, where he served as an official of integrity until his retirement (Ibid.). After finishing his service, Han Huang returned to his hometown where the Luofu Mountains are situated, and he devoted his life to compiling Yesheng, which was first published in 1639.11 It is said that soon after he learned that the Qing took the throne, he died of a broken heart.12 Han Huang introduces the Luofu Mountains by elucidating six core aspects and showcasing records from different historical periods; as a personally compiled gazetteer, Yesheng focuses on the geographical and cultural features of separate topics and “transcends dynasties, whereas histories cover single dynasties” (Dennis 2015, p. 1). In Yesheng, the first juan 卷 (chapter) presents a four-page panorama (Figure 1) of the Luofu Mountains, which is followed by some general relevant historical and mythological information and poems by contemporaneous and previous literati.13 The second juan lists 24 natural sites scattered within the Luofu Mountains; each has a fentu 分圖 (individual image of specific sites), an introduction written by Han Huang, and several related poems written by literati in previous dynasties.14 The third juan elaborates on the natural sites in the second juan, introducing the human-made sites within each natural site by briefly describing the location and history and by cataloging more poems that illustrate the views within.15 The fourth juan familiarizes readers with the well-known Daoist immortals and Buddhist saints who had been cultivated in the Luofu Mountains since the Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE).16 The fifth juan introduces the local products and rare animals of the Luofu Mountains.17 Finally, the last juan presents related stories and strange events said to have occurred within the Luofu Mountains.18 Different from the first two, the third through sixth juans do not contain images and comprise only text.

Figure 1.

Panorama of the Luofu Mountains, 1639. Woodblock print. After Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, 1.2a–3b (480).

2.2. Where Was Yesheng Engraved?

The designer and engraver of the images in Yesheng remain anonymous; however, on the right of the panorama, there is an answer—an inscription that reads “written and engraved on the twin peaks of Longgang” (Longgang queshang kexie 龍岡闕上刻寫), which might at least indicate the location of the engraver. A poem titled Moling 秣陵 (referring to modern-day Nanjing, in Jiangsu Province) by the famous Guangdong poet Qu Dajun 屈大均 (1630–1696), may reveal the location of Longgang:

“The bull’s head cracked open the sky towers, while the dragon’s spine embraces the earth palace. Among the spring grasses of the Six Dynasties, flowers wither away into ten thousand wells.”牛首開天闕,龍岡抱地宮。六朝春草裡,萬井落花中。19

In Nanjing, the “bull’s head” and the “dragon’s spine” metaphorically refer to the Niutou Shan 牛頭山 (Bull’s Head Mountain) and Zhong shan 鐘山 (Bell Mountain), respectively, and the character que 闕 (tower), indicates the twin peaks that look like the twin towers flanking a royal palace (Zhou 2011, p. 1051). Nanjing was a center of book publishing during the late Ming dynasty, and its books were famous for their delicate engravings (Ōki 2014, p. 18). In fact,, the work of Han Huang’s brother, Han Sheng 韓晟, was done by engravers in Chizhou 池州 in modern Anhui 安徽 Province, which was in the same province as Nan Zhili 南直隸 (South Direct-Administered Municipality), a region filled with efficient and well-qualified engravers.20 In addition, as mentioned earlier, Han Huang served as an official in Qingtian in Zhejiang, a province that formed part of the wealthy, literate region named Jiangnan 江南 (South of the Yangtze River). Therefore, it is highly possible that the compilation of Yesheng was a result of Han Huang’s experience in both Boluo County, his hometown, and the Jiangnan region, and that the phrase “twin peaks of Longgang” refers to Nanjing, a widely reputable publishing center.

2.3. Reference to Previous Gazetteers

According to his preface, Han Huang compiled Yesheng out of the regret for the Luofu Mountains’ “not having a gazetteer for a long time” (Luofu jiu wu zhi 羅浮久無志).21 Before Han Huang began working on Yesheng, his elder brother, Han Yinzhong 韓寅仲, published Luofu fumo 羅浮副墨 (A Copy of the Anthology of the Luofu Mountains), which is no longer extant.22 As Han Huang stated, his brother’s work mostly comprised contemporary poems instead of histories of previous dynasties, which could not be passed on to later generations.23 As the “Woodcutter of the seventh Grotto-heaven”, a local literatus who indulged in the marvelous views of the Luofu Mountains during his retirement, Han Huang felt obliged to compile a new, readable gazetteer to document the mountains in their prime (Ibid.).

However, it is important to note that Han Huang’s statement denying the existence of recent gazetteers of the Luofu Mountains is not true. Yesheng was first published in 1639 (Ibid.), at least three gazetteers were compiled before Han Huang’s work during the Ming dynasty, but Yesheng is the first and only to proclaim itself “unofficial”.24 The three gazetteers were completed by Chen Lian 陳槤 (active approx. 1470), Huang Zuo 黃佐 (1490–1566), and Han Mingluan 韓鳴鸞 (1582 juren).25 As records and poems by the above-mentioned authors are included in Yesheng and some of the writers had been to or were residents of Boluo County, it is quite likely that Han Huang was aware of their works.26

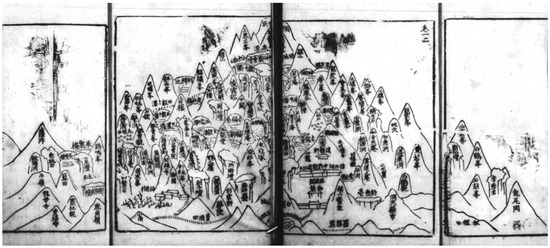

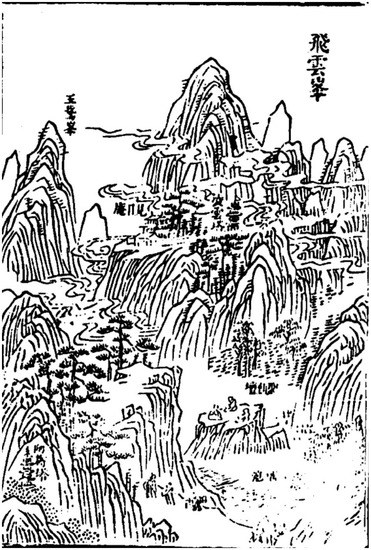

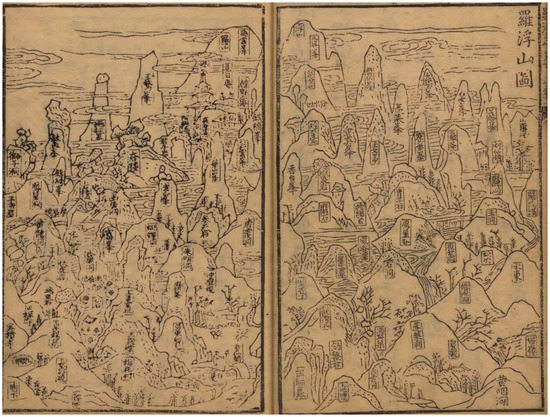

Evidence proving that Han Huang referred to previous gazetteers can be found by comparing Yesheng and other gazetteers that were previously published. First, Han Huang’s panorama shows clear similarity with Huang Zuo’s Luofu shan zhi 羅浮山志 (Gazetteer of the Luofu Mountains, Figure 2), published in 1552. Both panoramas are divided into four pages. Although Yesheng depicts the mountainous structure in a more detailed manner than that of Huang Zuo’s panorama, the natural sites along the contour of the mountain follow the same sequence on each page of the panoramas, shaping the Luofu Mountains with the same composition. From the bottom right to the top left on the first and second pages, that work illustrates the Baihe Feng 白鶴峰 (White Crane Peak), Xiannü Feng 仙女峰 (Fairy Peak), Zhiyun Feng 致雲峰 (Cloud Path Peak), Xiaoqi Feng 小旗峰 (Small Flag Peak), and nearby sites, with the Feiyun Feng 飛雲峰 (Flying Cloud Peak) at the very top. On the third and fourth pages, the work presents sites such as the Shangjie Sanfeng (Three Peaks of the Upper Realm), Fushan 浮山 (Floating Peak), Penglai Feng 蓬萊峰 (Penglai Peak), Yunmu Feng (Mica Peak), and Xiao Luofu 小羅浮 (Minor Luofu), which are sequentially located between the Feiyun Feng and the foothills. Additionally, important human-made sites are all placed at the same positions. For example, the Chongxu Guan 沖虛觀 (Unfathomable Emptiness Abbey) is situated below the Zhuming Dong 朱明洞 (Vermilion Brightness Grotto), the Baoji Si 寶積寺 (Treasure Accumulation Temple) is presented between the Zhong Ge 中閣 (Middle Pavilion) and Shutang Keng 書堂坑 (Study Hall Cave), and the Shuzhu An 黍珠庵 (Millet Beads Hermitage) is located between the Zhuoxi Quan 卓錫泉 (Tin Poking Spring) and Yele Chi 夜樂池 (Night Joy Pond).27

Figure 2.

Panorama of the Luofu Mountains in Huang Zuo’s Luofu shan zhi, 1552. Woodblock print. After Huang Zuo, Luofu shan zhi, 1.1b-3a.

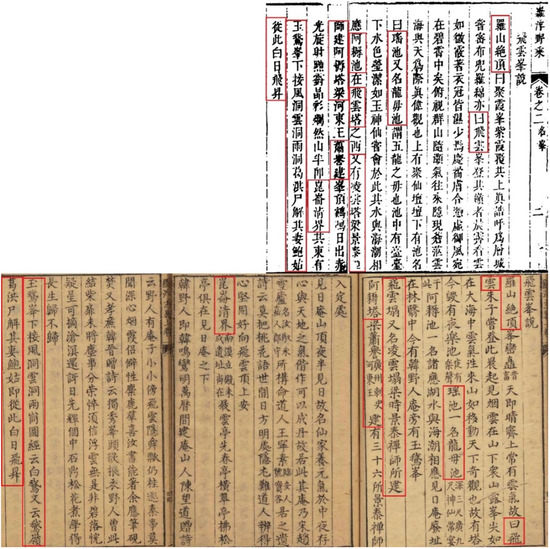

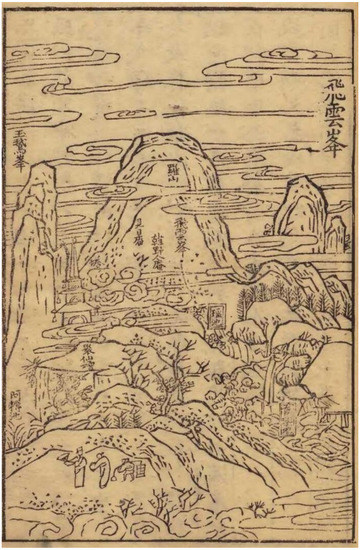

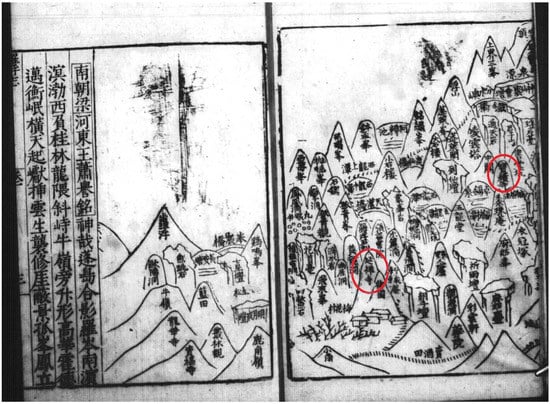

Second, in Yesheng, the texts introducing famous sites in juan 2 are similar to the related information in Han Mingluan’s Luofu zhi lue 羅浮志略 (Concise Gazetteer of Luofu), published in 1607, by comparing the texts in both gazetteers (Figure 3). Both Han Mingluan and Han Huang were members of the notable Han family of Boluo County, from which came many well-known officials who worked in the Ministry of Revenue (hubu, 戶部), the Ministry of Rites (libu, 禮部), and the local governments (Hou 2016). In his gazetteer, Han Mingluan collected two poems by Han Huang.28 As relatives and literati with mutual respect, it is reasonable to assume Han Huang and Han Mingluan were familiar with each other’s work. In Yesheng, Han Huang’s familiarity with Mingluan’s gazetteer can also be proven by a textual comparison. Taking Yesheng’s texts in juan 2 as a group of examples and comparing them to Mingluan’s related texts introducing natural sites, it can be found that much of the Yesheng text has significant similarities with Han Mingluan’s text.29 In texts of the Yesheng group, some of the core concepts are iterated in the same way as in Han Mingluan’s work, for example, “the Quanyuan Mountain is at the connecting point between the Luo and Fu Mountains, and the Tieqiao Feng is a peak at the west of the Quanyuan Mountain” (羅浮二山連接處為泉源山,鐵橋則泉源山以西峰也), and “when the phoenix bathes [in the Yele Chi], the five-colored mist gathers” (鳳來浴其中時,聚五色雲氣).30 The Yesheng text that shares the greatest similarity with Han Mingluan’s can be found in the text about the Feiyun Feng. A notable part of the description is transcribed word by word in the same order, including the narration of stories such as those of the construction of the Anou Ta 阿耨塔 (Anuttara Pagoda), the development of the grottoes below Yujiu Feng 玉鷲峰 (Jade Eagle Peak), and the deification of Ge Hong 葛洪 (283–343) and his wife Baogu 鮑姑 (c. 309–363).31

Figure 3.

Comparison between the Feiyun Feng texts in Han Huang and Han Mingluan’s books. The red frames mark the same expressions in both texts. Upper: after Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, 2.8b (503), 2.10b (504); below: after Han Mingluan, Luofu zhi lue, 1.51b, 1.75b. Image edited by the author.

3. The Grotto-Heaven

3.1. Luofu’s History as a Grotto-Heaven

Yesheng began to be circulated outside Guangdong after Li Yaogu 李遙穀 (dates of birth and death unknown) noted its demonstration of Luofu’s status as the seventh grotto-heaven. In 1701, Li Yaogu, the magistrate of Huizhou since 1695, was ordered to present a gazetteer of the Luofu Mountains to the Kangxi 康熙 Emperor (r. 1654–1722), for which Yesheng was collected and later officially published.32 In the preface written recommending Yesheng, Li recorded the following:

“[In the] winter of the xinsi year (1701), I was ordered by the emperor to visit heritage sites and collect gazetteers of Luofu.”辛巳冬,奉旨採訪羅浮遺跡及山圖誌書。33

Li Yaogu’s presentation of Yesheng was part of a national publication project. During the Kangxi reign, the Qing court began compiling the Comprehensive Gazetteer of Great Qing 大清一統志 (Daqing yitong zhi) (Qiao and Li 2018, pp. 236–37). To enrich and update the historical information, the court ordered officials to present gazetteers of various regions among the empire; as a result, a large amount of local historical accounts and gazetteers were transmitted to the Qing court (Wang 2016, pp. 332–33). Li Yaogu was one such official who accepted the order to contribute to the court’s project.34 To fulfill the mission in 1701, Li presented Yesheng to the emperor in 1701, and it remained in circulation at the court from that point on.35

Li Yaogu explained in his preface the main reason for choosing to present Yesheng: the book’s demonstration of Luofu’s status as the seventh major grotto-heaven. As the official who presented the book to the emperor, Li Yaogu wrote a preface to explain parts of Yesheng.36 In his preface, Li lamented that some of the famous sites of Luofu had already been ruined, and he asserted that Yesheng may have been one of the only gazetteers that provided a full picture of Luofu.37 Li Yaogu expressed a sincere hope that the Kangxi Emperor would come to know more about Luofu, the seventh Grotto-heaven in Daoism, through Yesheng:

[I] should definitely propose a destination for your future inspection, as the Luofu Mountains are inviting the emperor’s attention in viewing [one of] the Grotto-heavens; therefore, [I] humbly pay my respect and deliver my proposal by presenting this Yesheng.當寧獻幸,因羅浮一山,邀九重眷顧,俾得偏覽洞天福地,謹藉《野乘》,拜手上進。38

The Luofu Mountains have been described in holy tales since at least the Han dynasty (202 BCE–AD 220) and they have long had a reputation as the seventh grotto-heaven (Soymié 1956, pp. 25–26). Since the Jin dynasty (266–420), the list of the grotto-heavens contained thirty-six sites, among which the Luofu Mountains have been listed as the seventh, which can be proven by consulting Luofu shan fu 羅浮山賦 (Rhapsody on the Luofu Mountains) by Xie Lingyun 謝靈運 (385–433):

In all, there are thirty-six Grotto[-Heavens]:This one at the Luofu Mountains is the seventh.Light shines even in the dark night,The Sun illuminates the depths of the world.洞四有九,此惟其七。潛夜引輝,幽境朗日。39

Luofu’s status as a widely recognized major grotto-heaven underwent a few more rounds of changes. Although Xie had already named Luofu the seventh grotto-heaven, this designation had not yet been widely adopted. The list of the thirty-six grotto-heavens may be an early form of later categorizations.40 During the early Tang dynasty, a well-known Daoist priest Sima Chengzhen 司馬承禎 (647–735) first divided and derived the thirty-six grotto-heavens mentioned in Xie’s rhapsody into ten major grotto-heavens and thirty-six minor grotto-heavens in his treatise Tiandi gongfu tu 天地宮府圖 (Chart of the Palaces and Bureaus of the [Grotto-]Heavens and the [Blissful] Lands), in which the Luofu was officially categorized as the seventh major grotto-heaven.41 Later, court Daoist Du Guangting 杜光庭 (850–933) again listed the major and minor grotto-heavens in his Dongtian fudi yuedu mingshan ji 洞天福地岳瀆名山記 (Record of Grotto-Heavens, Blessed Places, Ducts, Peaks, and Great Mountains), the most comprehensive work of the Daoist worldview at that point, which finally systematized the Daoist grotto-heaven cosmology (Verellen 1995, pp. 272, 275; 1998, pp. 214–15).

Identifying a grotto-heaven such as Luofu involves a demonstration of its sacredness. The grotto-heavens are, as Franciscus Verellen summarized, a “place of refuge from civilization” (Verellen 1995, p. 268). In the Daoist imaginary, the grotto-heavens are natural utopias where the immortals live or earthly paradises that are immune from any kind of catastrophe.42 Areas that become grotto-heavens provide a secluded environment filled with elixirs for immortals, as grotto-heavens are defined as the most ideal place for giving offerings to immortals. The Daoist liturgist Zhang Wanfu 張萬福 (active around 712) in the Tang dynasty describes such offerings as follows:

The Offering is the means by which we present our sincerity to Heaven and Earth and pray for blessings to the unseen gods…The most excellent way to establish the altar is to avail oneself of a grotto among the Great Mountains.凡醮者,所以薦誠於天地,祈福於冥靈……凡設座,得名山洞穴是佳……43

Luofu’s grotto-heaven status represents a sacred sanctuary. The full title of Luofu in the Grotto-heaven system is “Zhuming Yaozhen”, the “Vermillion Brightness Shining Truth”, which specifically centers on the grotto Zhuming Dong, a secluded grotto located at the middle foot of Feiyun Feng, the main peak of the Luofu Mountains. In the works of Qing Dynasty writers Qu Dajun 屈大均 (1639–1696) and Shen Tingfang 沈廷芳 (1702–1772), the Zhuming Dong is located at the “acupoint” (shuxue 腧穴) of the Luofu Mountains and is considered the “root of the mountain”, a core site in the region of the Luofu Mountains, indicating that the geography of Zhuming Dong presents a secluded, ideal cave-like structure.44 In addition, according to Luofu Zhi written by Chen Lian, Zhuming Dong is “full of branches and thorns, so outsiders cannot enter” (Zhenmang buke ru 榛莽不可入), meaning that it is a natural, sacred barrier against the chaotic, mundane world, demonstrating Luofu’s sacredness by differentiating it from “profane” space, to borrow Eliade’s term.45

3.2. Demonstration of the Grotto-Heaven in Yesheng

Almost all previous Luofu gazetteers compiled in the Ming dynasty emphasized the significance of this grotto-heaven in a notable way. In Chen Lian’s work, the information about the grotto-heaven follows right after the general introduction to the geography of the Luofu, listing the area’s grotto-heaven reputation as the most important feature in the Luofu Mountains.46 In Huang Zuo’s Gazetteer, the grotto-heaven is described at the beginning of the introduction, showing Luofu’s sublime status in Daoism:

Luofu, the peak of Guangdong, is [a] Grotto-heaven and Blissful Land, [which is] notably recorded in Daoist scripts.羅浮粵望也,洞天福地,名列道書。47

In Han Mingluan’s Luofu zhi lue, the author expresses how regretful he would be if he did not introduce the Grotto-heaven well, which also appears at the beginning of his introduction:

It is lucky to have the seventh Grotto-heaven at [only] fifty li away from my hometown. What wonder [could] I discover if I only admired [places] far away instead of [those] nearby?第七洞天,幸在桑梓五十里。慕遠遺近,豈善探奇?48

Similar to what had been written in previous gazetteers, Yesheng also demonstrates the significance of a grotto-heaven. First, the literary works selected in Yesheng reveal a long history of Luofu being considered a grotto-heaven. Han Huang introduces the geographical features of Luofu by quoting the opinions of the Ming dynasty literati, highlighting that Luofu features both grotto-heaven and blissful land sites, suggesting that its surrounding landscape is a “world-class wonder” (Tianxia zhi qiguan 天下之奇觀).49 As the first chapter, which introduces its audience the general literary tradition of the Luofu Mountains, juan 1 pointedly demonstrates Luofu’s status as a grotto-heaven and as a sacred Daoist place. Many poems in juan 1 emphasize Luofu’s reputation as a grotto-heaven. The tradition of admiring Luofu as a grotto-heaven has existed since the Xie Lingyun in the Jin dynasty, as listed in the following chart (Table 1):

Table 1.

Poems Describing Luofu as a Grotto-Heaven Collected in Luofu Yesheng.

Second, Han Huang’s own words showed his attention to Luofu’s grotto-heaven status. At the beginning of the introduction to juan 2, Han Huang demonstrated that the famous grotto-heavens such the Mao Shan 茅山 (Mao Mountain), the Linwu Shan 林屋山 (Linwu Mountains), and the Luofu Mountains were interconnected.50 This theory was, as clarified by Han Huang, quoted from the Maojun neizhuan 茅君內傳 (Revealed Biography of the Lord Mao), one of the earliest texts that recorded the concept of the thirty-six grotto-heavens (Raz 2010, p. 1431; Robinet 1984, vol. 2, pp. 389–98). Such a description was also well documented in the Daoist classic Zhen gao 真誥 (Declarations of the Perfected):

“From the cave heaven of Gouqu [extend] great paths, to the east reaching Linwu, to the north Mount Dai (in Shandong), to the west Mount Emei (in Sichuan), and to the south Luofu (in Guangdong). Between them are numerous intersecting paths.”句曲洞天,東通林屋,北通岱宗,西通峨眉,南通羅浮,皆大道也,其間有小徑雜路, 阡陌抄會,非一處也。51

The conception of the grotto-heaven marks the sacredness of the Luofu Mountains. The interconnection among grotto-heavens was passed on to later Daoist classics, such as the scripture Shi taishang suling dongxuan dayou miaojing 釋太上素靈洞玄大有妙經 [Explanation of the Scripture of the Most High Unadorned Spirituality in the Pantheon from the Dayou], which suggested that a grotto can access all directions: “A grotto connects to the heavens and the earth; there is nowhere that a grotto cannot reach (洞者,洞天,洞地,無所不通也)”.52 As Li-tsui Flora Fu concluded, such an interconnected network formed an “interiorized world apart”, a world exclusively host to “exalted Perfected and divine immortals” (Fu 2009, p. 9). Such a construction of a conceptual world, in Eliade’s theory, is a reproduction of “the work of gods”, which is inferably the factor that makes a space sacred.53

4. Writing for the Luofu Mountains

4.1. Yesheng as a Supplementary Text

Despite his denial of the existence of previous Luofu gazetteers or his advocacy of Luofu as a Daoist sacred site, based on this article’s previous arguments on his reference to previous works, Han Huang had other reasons for compiling Yesheng. First, Han Huang’s statement indicating the lack of gazetteers on the Luofu Mountains does not truly mean that there were absolutely no Luofu gazetteers but that he was disappointed in the existing ones. Explaining the function of Yesheng, Han Huang emphasized that although the gazetteer had been completed in a rudimentary way, it still sufficiently depicted the Luofu Mountains’ scenery:

“[Although it is] roughly drafted, it still shows the scenery of Luofu sufficiently, [so I] named [it] The Unofficial History of the Luofu Mountains”.粗具崖略,足備覽觀,題曰《羅浮野乘》。54

Then, Han Huang introduced his proposition to document the famous mountains. Although Yesheng was an “unofficial” gazetteer, he emphasized that writing about a famous mountain focuses on balancing information about specific sites and related literary works:

“The Woodcutter states: “famous Mountains cannot be known without [being recorded] in literature, so the [information about] famous sites and literature works should be equally demonstrated.”樵客曰:“名山非文不傳,則勝概與詞章並重矣。”55

Hence, Han Huang showed his regret in seeing historical accounts written by his contemporaries that failed to obtain a balance between the famous sites of Luofu and related literary works. In contrast to the authors of existing Luofu gazetteers, Han Huang chose to focus on documenting both geographical features and the literary works compiled in earlier gazetteers instead of merely gathering large numbers of works as his contemporaries did:

“Old [Luofu] gazetteers collected arts and literature, focusing on the [achievements] of [related] figures. Currently, such works scatter into various [Luofu gazetteers] and focus on the mountains, which is merely piling up the works.”舊志集藝文為一書,以人重也。今則分附各種之內,大都以為名山重,鋪張盛而已。(Ibid.)

Han Huang chose to compile the gazetteer to supplement the contents of previous gazetteers, against which he could compare his own work.56 However, how did Han Huang supplement the works of his peers? The question leads to Han Huang’s second reason for compiling Yesheng, which was to reconstruct the scenery of Luofu at its prime as it had been severely damaged during his lifetime.

4.2. As a “Relief” for the “Shame”

Han Huang’s second reason to pursue his gazetteer was to redeem the Luofu’s loss. Despite the safety of the grotto-heaven being assured in the Daoist texts, the Luofu Mountains had gone through disastrous periods in their history. As recorded by Chen Botao 陳伯陶 (1855–1930), in which he supplemented the gazetteer written by his forefather Chen Lian, a severe destruction occurred exactly during the late Ming dynasty in which Han Huang lived: “In the late Ming, thieves aggressively gathered at the mountains’ foot, thoroughly burning and looting whatever was left (明末群盜嘯聚山下,焚掠靡遺)”.57 In his preface, Han Huang also recorded that the Luofu Mountains suffered from being looted by fierce brigands, which caused a great range of destruction. In Han Huang’s words, this disaster was an “shame” (xiu 羞) to Luofu.58 For such a shame, Han Huang expressed his regret for not being able to see the sites’ original views in person:

“Although my body decays, my spirit is incredibly active, [but] I can no longer find the views within the images for recumbent travels, as they are all gone.”筋支雖衰,猶思騰踔,不能向臥遊圖討風景,沒沒也。59

With regard to the loss and embarrassment suffered by the Luofu Mountains, Han Huang sought to “relieve [the] shame” (jiechao) of such loss:

“Compiling this gazetteer is to relieve the shame of the famous mountains, [I am] just like the fisherman telling everyone about the Wuling Yuan without knowing anything but its peach blossom and flowing stream. [As for] the dynasty being the Qin or Jin, the villagers immortals or hermits, if the fisherman never knew, how can I know?”是編聊為名山解嘲,比如捕魚者語人以武陵源,知有桃花流水而已。代之以為秦為晉,人之為仙為隱,漁人不知也,余又嗚呼知之!60

Here, Han Huang compared himself to a fisherman who visited Wuling Yuan in the famous treatise Record of the Peach Blossom Land (Taohua yuan ji 桃花源記) written by the Jin hermit Tao Yuanming 陶淵明 (365–427), implying that he would forget the changes in Luofu. In “Peach Blossom Land”, Tao Yuanming depicted a fisherman from Wuling 武陵 who encountered an earthly paradise after walking through a grotto.61 In that paradise, the fisherman found that the villagers were not at all aware of anything that had happened in China since their isolation centuries ago (Nelson 1986, p. 23). After being invited to stay, the fisherman asked the villagers if they knew anything about the current dynasty, and the answer was no:

“Of their own accord they told him of their forefathers who had, during the troublous times of the Chins (Qin), sought refuge in this place of absolute seclusion together with their families and neighbors. After having settled down here they never thought of going out again. They had been so cut off from the rest of the world that knowledge of the times would be a revelation to them. They had not heard of the Han Dynasty, not to mention the Wei and the Tsin (Jin).”自云先世避秦時亂,率妻子邑人來此絕境,不復出焉;遂與外人間隔。問今是何世,乃不知有漢,無論魏晉。62

Before the fisherman returned to where he belonged, the villagers reminded him that his experience in their paradise was “not worth mentioning” to outsiders. The fisherman did not follow their instruction. He attempted to bring officials to that secluded village and finally found himself totally lost and unable to enter the village again.63

Han Huang’s final statement expresses the twofold attitude toward the Luofu Mountains like the fisherman in Tao’s treatise. On the one hand, Han Huang saw himself as the fisherman who had lost his way back to the utopian village. While he lived right below the Luofu Mountains, Han Huang, similar to the fisherman, did not know how to get back to Luofu as a utopian place, which was described by the late Mircea Eliade as a “‘pure region’ transcending the profane world.” (Eliade 1987, p. 41). Instead, what Han Huang selected to record in his gazetteer were the memories, personal or collective, of Luofu in its prime. During the time when Han Huang lived, private Confucian schools phenomenally increased in number, boosting innovative Confucian ideological discourse (Elman 1989, p. 387). However, such schools formed political parties, such as the Donglin dang 東林黨 (Eastern Woods Party), causing repeat attempts at suppression by the government and severe turmoil among society and intellectual circles during the last years of the Ming dynasty (Akin 2021, p. 166). As Max Weber concluded, “Confucianism was the status ethic of prebendaries, of men with literary educations who were characterized by a secular rationalism.”64 As a literatus official who was largely exposed to the Confucian ideologies, it is highly possible that Han Huang was also impacted by the instability and insecurity within society. Like the fisherman, Han Huang could also focus only on his memory of the “peach blossom and flowing stream,” insisting on derivatively depicting the sites of Luofu that had previously been intact and that could not be seen again, recalling the previous times of tranquility.

On the other hand, Han Huang also found himself in the position of the fisherman confused by the villagers’ perception of time. In Tao’s treatise, the villagers’ omission of the existence of the present dynasty indicated a “suspension of time and space” (Barnhart 1983, p. 16). By paying tribute to the imaginary of the peach blossom land, Han Huang demonstrated that Luofu should be the same kind of utopia or sacred site as the one in Tao Yuanming’s record, which is, to most worldly beings, highly inaccessible. Only by suggesting a suspension of time, as Tao’s villagers did, could Han Huang maintain the state of mind in which his focus was only on providing a complete picture of the landscape of Luofu without concerning himself with the dynastic changes that had been made to the sacred mountain. While destruction had breached the otherworldly barrier in Luofu, Han Huang chose to depict the rest of the Luofu sites to “relieve shame” to the place and to revive it as a grotto-heaven that resists disasters and thereby eventually present a complete picture of Luofu.

5. Reconstructing the Sites

5.1. Distribution of Luofu’s Religious Sites

Although he claimed to be a “woodcutter” of a Daoist grotto-heaven, Han Huang had a vision for the compilation of Yesheng, which should be considered a result of his belief in syncretism among Daoism and other mainstream traditions of belief, which are Buddhism and Confucianism. By bringing up other traditions in his book presumably dedicated to introducing a Daoist grotto-heaven, Han Huang put both Buddhism and Confucianism into the framework of the Daoist sacred geography, incorporating and sanctifying them into the protection provided by the grotto-heaven. Yesheng shows Luofu’s religious significance by emphasizing the grotto-heaven and presents the immaculateness of the grotto-heaven by visually and textually reconstructing religious sites that did not exist or were partly destroyed during Han Huang’s lifetime. In other words, his goal was to reconstruct sites of different traditions to show a grotto-heaven that was “inaccessible to outsiders”, as it had been described by Han Huang’s predecessor Chen Lian.65 Among the texts and images of the sites listed above, Yesheng highlights religious significance by reconstructing the religious sites in the gazetteers’ images, as Han Huang said, to “relieve” the “shame” of the destruction of the famous mountains.”66

Regarding Confucianism, Han Huang himself owns the identity of a Confucian scholar. As mentioned before, Han Huang passed the imperial examination and was made juren, the intermediate degree of this grand examination (Yü 2016, p. 192). In traditional Chinese societies, the imperial examination focused on “formalism and conformity to the state-set Confucian orthodoxy centering around the master Zhu Xi 朱熹 (1130–1200)” (Lin 2022, p. 297). During the late Ming dynasty, only those who showed “superior understanding” of the Confucian canonical texts could pass the imperial exam, which reflects Han Huang’s familiarity with traditional Confucian thoughts (Lin 2022, p. 300).

Luofu’s Buddhist significance is not to be neglected. In China, both Daoist and Buddhist monks chose eremitic cultivation in mountains in order to stay away from the mundane world (Paracka 2012, p. 87). As two religions that have long co-existed with and learned from each other, the sacred geographic systems of both religions may be developed from the same exact origin (Feng 2018, p. 144). As Han Huang recorded, since the Liang (502–557) dynasty when the Luofu Mountains were already recognized as a Daoist sacred place, there were already Indian Buddhist monks cultivating and contemplating in Luofu.67 The later Buddhist monks in the Tang, Song, and Ming continued to build Buddhist sites, leaving behind notable traces of Buddhist heritage.68 Especially in the late Ming dynasty, the monk Zongbao 宗寶 (dates of birth and death unknown) became the abbot of the main temple of the Huashou Tai 華首台 (Patriarch Terrace), placing Luofu at the center of the Caodong 曹洞 (Cao Grotto) Sect of Chan 禪 Buddhism in Guangdong, which later became the most influential Buddhist sect among the entire region of Lingnan.69 It is possible that Han Huang was an acquaintance of Shengren 剩人 (1612–1660), a Buddhist master practicing in the Huashou Tai. Shengren was the son of Han Rizuan 韓日纘 (1578–1636), a leading figure in the Han family and a contemporary to Han Huang.70 As relatives, Han Huang’s descendants participated in the compilation of Shengren’s anthology, reflecting the close relationships within the Han family, and suggesting Han Huang’s own exposure to Buddhist belief.71

In general, in addition to the essence of Luofu being a Daoist grotto-heaven, Han Huang demonstrated its sacredness not only to Daoism but also to Buddhism and Confucianism, as he also listed a considerable number of Daoist, Buddhist, and Confucian features. The visual presentation of sacred sites can be seen in the fentu section in juan 2. Fifteen of twenty-four prints of natural sites in Yesheng depict the forms, names, and locations of architecture that represent the three major traditions, including Daoist abbeys, Buddhist temples, and Confucian academies. With the information introduced and noted in texts and images in Yesheng, the chart (Table 2) below lists all the religious architecture marked within the prints of the natural sites, which are 27 in total, following the sequence of juan 2:

Table 2.

Poems Describing Luofu as a Grotto-Heaven Collected in Luofu Yesheng.

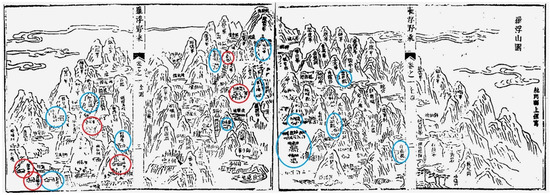

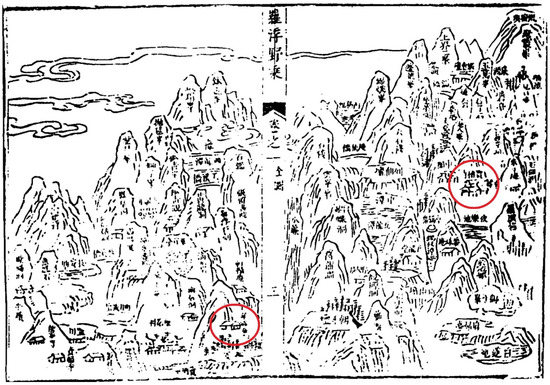

Among the abovementioned 31 buildings, 18 are Daoist, while 9 are Buddhist, and 4 Confucian. While the Luofu Mountains have long been considered a sacred Daoist site, Buddhist and Confucian sites are still worth noting, as both Buddhism and Confucianism played an important role in forming the sacredness of Luofu.72 Many of the buildings listed above are also marked in the Yesheng panorama (Figure 4). In comparison, such a list of religious sites is much shorter in Han Mingluan’s gazetteer. Compared with Yesheng, in which 15 out of 24 images of natural sites contain religious buildings, Han Mingluan’s images mark only 6 out of 29 natural sites that contain religious buildings. Among the 12 religious buildings marked in Han Mingluan’s images, only 8 are Daoist, 2 are Buddhist, and 2 Confucian. The chart (Table 3) below provides shows some relevant details:

Figure 4.

Panorama of the Luofu Mountains in Yesheng, marked with Daoist (blue) and Buddhist (red) sites. Image edited by the author.

Table 3.

Religious Architecture Depicted in Illustrations of Han Mingluan’s Luofu zhilue.

In addition to the fentu, Han Huang’s panorama indicates his attention on religious architecture too, depicting the topography where the three traditions, Daoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism, co-existed harmoniously. According to the panorama, while the Daoist buildings are scattered across both the left and right parts of the panorama, Han Huang placed the Buddhist sites mainly on the left. This panorama reveals information on how the distribution of religious sites was designed. In investigating the distribution of these religious buildings, it is important to first refer to the geographical situation of the Luofu Mountains and panoramas in previous gazetteers. As mentioned at the beginning of this article, the Luofu Mountains consist of two peaks: Luo Mountain and Fu Mountain. The sites mentioned in the above list are separately located across the two mountains. On Luo Mountain, the main sites are around the Zhuming Dong, where Chongxu Guan lies, while on Fu Mountain, Buddhist sites such as Yanxiang Si and Baoji Si are the most visited (R. Li 2021, pp. 254–255). In the panorama in Huang Zuo’s gazetteer (Figure 5), the Fu and Luo Mountains are located on the left and right parts of the composition, respectively.73 As imitated by Han Huang, the Huang Zuo panorama also locates Buddhist sites on the left, while the Daoist buildings are scattered across the entire composition. As for the Confucian sites, the Zhang Liu Shuyuan and Yuzhang Shuyuan located around the Huanglong Dong are both placed at the very far left of the panorama. Following the distribution of these sites, by marking the Luo and Fu Mountains on the top of each side of Luofu, Huang Zuo’s panorama seems to indicate that the left two pages mainly contain the sites on Fu Mountain, while the right two mainly contain the sites on Luo Mountain. In reviewing the Han Huang panorama, it is evident that although the peak indicating the Luo Mountain has been wiped out, it still follows the basic distribution of the panorama in Huang Zuo’s gazetteer, depicting sites on both Luo and Fu Mountains. As a result, while Han Huang scattered Daoist sites across all of Luofu, he distributed the Buddhist sites mainly in the region of Fu Mountain.

Figure 5.

Panorama of the Luofu Mountains in Huang Zuo’s gazetteer, marked with Daoist (blue) and Buddhist (red) sites. Image edited by the author.

5.2. Visual Reconstruction of Religious Sites

5.2.1. The Xianri An

The Xianri An is the first example showing Han Huang’s reconstruction of destroyed sites. In the first fentu in Yesheng (Figure 6), directly below the Feiyun Feng and to the left of the Buddhist pagoda Lingyun Ta, the Xianri An is erected on the top of a mountainous terrace.74 As described by the Song Daoist priest Zou Shizheng, the hermitage was named Xianri An, as visitors could see the sun rising during the night from there.75 However, during Zou’s time in the Song dynasty, the Xianri An had already been destroyed and hidden deep in the forest (Ibid.). Built in the Song dynasty by Zhao Xuelu 趙雪廬 (dates of birth and death unknown), the Xianri An was principally hosted by Zhao’s contemporary, the Daoist priest Wang Ningsu 王寧素 (dates of birth and death unknown).76 However, the Xianri An was destroyed immediately after Wang Ningsu passed away.77 The destroyed Xianri An remained is disrepair until at least the early Qing, when Pan Lei 潘耒 (1646–1708) traveled among the Luofu Mountains.78 In Han Mingluan’s gazetteer (Figure 7), although the Xianri An is also recorded as a site showing the other worldly view of the night-sun, the author described it as a “ruin.”79 Its ruined state is also shown in the fentu in Han Mingluan’s gazetteer: behind the pagoda, only the name of the Xianri An is marked, leaving an empty area below the monumental Luo Mountain. In contrast, the Xianri An in Yesheng remains intact and undamaged. From the image, the structure of the Xianri An is identifiable: outside is a gate and surrounding flora, while inside is a lower and upper area with two-story temples.

Figure 6.

Image of the Feiyun Feng, 1639. Woodblock print. After Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, 2.2a (500).

Figure 7.

Image of the Feiyun Feng, 1607. Woodblock print. After Han Mingluan, Luofu zhi lue, 1.43a.

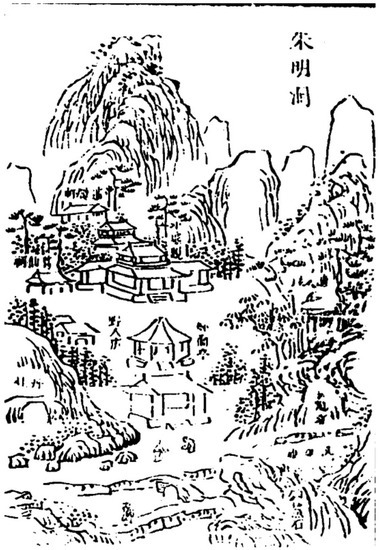

5.2.2. The Zhuming Dong and Chongxu Guan

The image of the Zhuming Dong can be taken as another example. Depicted in the image (Figure 8) are sites such as the Gexian Ci, Yiyi tan 遺衣壇 (Terrace of Leftover Clothes), Dan Zao 丹竈 (Elixir Hearth), Yiguan Zhong 衣冠冢 (Tomb of the Attires), Xiyao Chi 洗藥池 (Pond for Medicine-Washing), and the leading site Chongxu Guan, a sacred site of the Lingbao 靈寶 (Numinous Treasure) sect of Daoism before the Qing dynasty.80 Legend has it that the Chongxu Guan was first named Duxu Guan 都虛觀 (Metropolitan Emptiness Abbey) or Xuanxu Guan 玄虛觀 (Mysterious Emptiness Abbey) and built by the elixir master Ge Hong during the Jin dynasty; in 1087, the abbey was finally renamed Chongxu Guan.81 Few historical accounts regarding the reconstruction of the Chongxu Guan during the Ming dynasty survive today (C.-T. Lai 2007, p. 80). However, supplementarily, based on knowledge from previous gazetteers, the late Qing literatus Chen Botao summarized the situation of the Chongxu Guan in the Ming:

“The Chongxu Guan was at its prime during the Longqing and Wanli reigns and was gradually in decline during the Tianqi and Chongzhen reigns… In the late Ming, thieves aggressively gathered at the mountain’s foot, burning and looting everything. The abbey was destroyed, and only the central hall survived.”自永樂至隆萬間,觀為最盛。啟禎時,漸圮……明末群盜嘯聚山下,焚略糜遺,觀被毀,惟中殿存。82

Figure 8.

Image of the Zhuming Dong, 1639. Woodblock print. After Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, 2.24a (511).

After the Tianqi 天啟 (1621–1627) and Chongzhen 崇禎 (1628–1644) reigns, the situation of the abbey continued to decline. The abbey was not renovated until 1687, the twenty-sixth year of the Kangxi reign (C.-T. Lai 2007, p. 79). At that point, the Guangdong poet Chen Gongyin 陳恭尹 (1631–1700) wrote about the dilapidation of the Chongxu Guan in his poem Su Chongxu Guan 《宿沖虛觀》 (Overnight Stay at the Chongxu Guan):

“Now the carved beams are the termites’ house, while the Daoists can live only in huts built with weeds. I drank [with] and spoke [to the Daoists] under the plum, and such a Blissful Land is now as inaccessible as our mundane world.”幾穴雕樑巢白蟻,一家衰草住黃冠。山尊對語梅花下,福地而今路亦難。(Liu and Zhou 1980, p. 201)

Han Huang visually reconstructed the Chongxu Guan by imitating a previous image. According to Chen Botao, during the Wanli 萬曆 reign (1573–1620), the Chongxu Guan was intact and famous.83 In Han Mingluan’s gazetteer, the Chongxu Guan (Figure 9) was individually pictured on two pages, as it was one of the grand sites.84 In this image, crossing the Bailian Chi 白蓮池 (White Lotus Pond) by walking down the Huixian Qiao 會仙橋 (Immortal Gathering Bridge), the viewer comes to the gate of the abbey, on which is displayed a plaque with the inscription, “Grotto-Heaven of Vermillion Brightness” (Zhuming dongtian 朱明洞天). Through the gate, the Yujian Ting 御簡亭 (Imperial Writing Pavilion) stands in front of the main hall, the hearth on the left, the terrace on the right. Finally, at the innermost part, there stands the Penglai Ge, located directly at the foot of the peak, which stands behind it (Ibid.). As Han Mingluan said, this was a time when all tourists “stopped to appreciate the abbey”.85 In contrast, during the Chongzhen reign, when Han Huang lived, the Chongxu Guan had already been ruined after being looted by the brigands, and only the main hall had survived. However, except for Han Huang’s picture showing the terrace instead of the Penglai Ge, which may have been destroyed by then, and the Gexian Ci replacing the hearth, which was relocated to the left of the image, the bridge, the pavilion, and the halls flanking the main hall are still depicted as intact as they are in Mingluan’s print.

Figure 9.

Image of the Chongxu Guan, 1607. Woodblock print. After Han Mingluan, Luofu zhi lue, 1.24b-25a.

5.2.3. The Penglai Ge

The Penglai Ge may also reveal Han Huang’s past-tense focus on the Luofu Mountains. As recorded by Song Guangye 宋廣業 (1649–1720) and a later comprehensive gazetteer of Guangdong, the Penglai Ge, the place where Daoist Zhu Lingzhi 朱靈芝 gained enlightenment and became immortal, was first built near the Penglai Feng. However, the Penglai Ge was destroyed and subsequently moved to the Chongxu Guan.86 Over thirty years before Han Huang, the image of the Chongxu Guan in Han Mingluan’s gazetteer had already included the Penglai Ge, which may indicate that the Penglai Ge had already been moved to the Chongxu Guan.87 However, in Yesheng, the Penglai Ge is depicted still within the image of the Penglai Feng, and the information on destruction is not mentioned at all; instead, Han Huang describes the geography based on the original location of the Penglai Ge.

5.2.4. The Yanxiang Si and Baoji Si

The same visual restoration also exists in Yesheng’s image of Buddhist temples. Additionally, Chen Botao’s work documents temples such as the Yanxiang Si (Lasting Auspiciousness Temple) and the Baoji Si, which were both destroyed during the Hongwu 洪武 reign (1368–1398).88 In fact, the destruction time may have been much earlier. As Wu Qian 吳騫 (1691 jinshi) documented, the Yanxiang Si may have already been destroyed during the late Tang dynasty.89 In the early notes of Qing literati figure Pan Lei (1646–1708), Yanxiang Si was recorded as a ruined site, where only the “base of Yanxiang Si” (Yanxiang Si ji) remained.90 In Han Mingluan’s gazetteer, Yanxiang Si and Baoji Si are not marked in all images in either the panorama (Figure 10) or the fentu. Both Yanxiang Si and Baoji Si can be noted in Huang Zuo’s panorama (Figure 11) but in a form that indicates only the locations and names. However, Han Huang attempted to represent the temples visually. In his words, Han Huang introduced the locations of “today” as if all the sites were still there.91 In Han Huang’s panorama, both Yanxiang Si and Baoji Si are pictured as existing temples (Figure 12). As documented in Yesheng, the temples were located around the region of Zhuoxi Quan (Figure 13), as shown in Yesheng’s fentu.92 In this image, the temples are, along with their associated pavilion and academy, pictured as undamaged sites. At the foot of the stairs to the terrace where the Baoji Si is situated, three figures walk from the Xizhang Tan (Tin Cane Pond), picturing a peaceful, undisturbed site where the scene was still intact, just as described by Han Huang.

Figure 10.

Panorama of the Luofu Mountains, 1607. Woodblock print. After Han Mingluan, Luofu zhi lue, 1.10b-11a.

Figure 11.

The Yanxiang Si (left) and Baoji Si in the panorama in Huang Zuo’s gazetteer, 1557. Woodblock print. After Huang Zuo, Luofu shan zhi, 1.1b-3a.

Figure 12.

The Yanxiang Si (left) and Baoji Si in the panorama in Yesheng, 1639. Woodblock print. After Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, 1.2a-b (480).

Figure 13.

Image of the Zhuoxi Quan, 1639. Woodblock print. After Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, 2.35a (517).

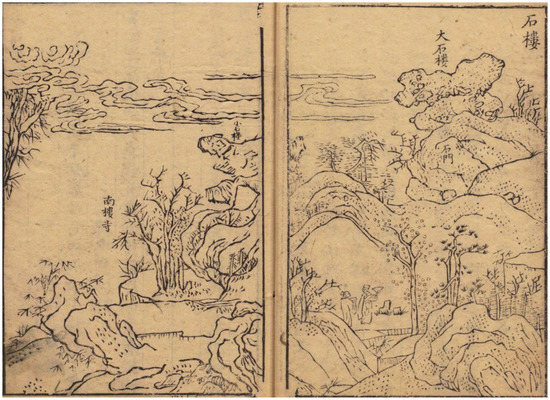

5.2.5. The Nanlou Si

Another Buddhist temple, the Nanlou Si (South Tower Temple), is another example of Han Huang’s reconstruction of Buddhist sites. Documents recording the Nanlou Si, which was located south of the Shilou Feng 石樓峰 (Stone Tower Peak), can be traced back to the Tang dynasty, and noted a type of orange that grew around the temple and was often offered as a tribute to Emperor Xuanzong (r. 713–741).93 Unfortunately, similar to the Yanxiang Si, the Nanlou Si was also ruined during the Hongwu reign.94 Han Huang was clearly aware of the early history of the Nanlou Si, as according to Yesheng’s juan 3, the Nanlou Si was first built during the Liang dynasty, ruined and rebuilt during the late Tang dynasty, and relocated during the Yuan dynasty.95 However, Han Huang did not mention the Nanlou Si’s destruction during the early Ming dynasty. Instead, in Yesheng’s fentu, the Nanlou Si (Figure 14) is still standing below the stone towers, and Han Huang’s text does not mention the destruction of this temple either.96 In contrast, the part of the Shilou Feng in Han Mingluan’s gazetteer marked that the Nanlou Si comprised only a remaining ruin site.97 In addition, although the name of Nanlou Si is marked in the image of the Shilou Feng at the exact location as the image in Yesheng, the shape of the temple is missing, leaving a void behind the trees below the Shilou Feng (Figure 15).98

Figure 14.

Image of the Shilou Feng, 1639. Woodblock print. After Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, 2.46a (522).

Figure 15.

Image of the Nanlou Si, 1607. Woodblock print. After Han Mingluan, Luofu zhi lue, 2.4b-5a.

5.2.6. The Sixian Ci

The Sixian Ci is an example showing Han Huang’s conceptual reconstruction of a Confucian site. Built by Zhan Ruoshui 湛若水 (1466–1560), one of the most influential Confucian scholars of the Ming dynasty, the Sixian Ci was constructed on the ruins of the ancient Tianhua Gong 天華宮 (Celestial Flora Palace), in memory of Zhou Dunyi 周敦頤 (1017–1073), Luo Congyan 羅從彥 (1072–1135), Su Shi 蘇軾 (1037–1101), and Chen Xianzhang 陳獻章 (1428–1500), four great Confucian gentries from earlier times.99 After he started living in Luofu in 1540, Zhan Ruoshui wrote the treatise Dian Tianhua Sixian Ci wen 奠天華四賢祠文 (Treatise on the Foundation of Four Worthies Shrine of the Celestial Flora) marking that the construction of the Sixian Ci was first begun in early 1543 (Y. Li 2009, pp. 266, 280). As recorded by Song Guangye, the Sixian Ci was also a site in ruins.100 As Song Guangye stated regretfully, it is unfortunate that the Sixian Ci could not be adequately restored, as among many notable Daoist and Buddhist temples, the Sixian Ci was the only grand site of Confucianism (Ibid.).

In Yesheng’s fentu of the Huanglong Dong (Figure 16), among the Ciji An, Longhua Si, and Yuzhang Shuyuan, the Sixian Ci remains an undamaged complex consisting of two single-story shrines. Placing the Sixian Ci with such sites shows Han Huang’s subjective redesign. In fact, the Longhua Si nearby was moved and re-assigned as a part of another Buddhist temple, the Yanqing Si 延慶寺 (Everlasting Celebration Temple) in 1392, the 25th year of the Hongwu reign, which is 151 years before the Sixian Ci was built.101 By anachronistically displaying the historical sites, Han Huang deliberately pictured a landscape where Buddhist and Confucian sites synchronically thrived.

Figure 16.

Image of the Sixian Ci in the Huanglong Dong image, 1639. Woodblock print. After Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, 2.41a (520). Image edited by the author.

6. Conclusions

This article investigates the compilation of the book by late Ming dynasty literati member Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, through the lens of five aspects. Compared with earlier gazetteers of the Luofu Mountains, although Han claimed that his work was “unofficial”, Yesheng is still a concise yet inclusive gazetteer of Luofu that, like all previous gazetteers, demonstrates the sacredness of the region due to its status as a major grotto-heaven and its significance as a great religious site in Guangdong.

In conclusion, by recalling and paying tribute to previous times, Han Huang achieved his goal of idealizing the Luofu Mountains in his editing of literary and woodblock print works. As brought up at the beginning of this article, Han Huang, based on the information he obtained from previous gazetteers, truly “supplemented” the writing and depiction of the Luofu Mountains. Outlining the primary content of Yesheng and comparing the number of examples across topics such as sites, literary works, and anecdotes, this article discovers Han Huang’s purpose in editing Yesheng: to supplement the lack of information in previous gazetteers. After scrutinizing the previous related historical records and comparing the information on the sites recorded therein to the texts and images in Yesheng, it can be concluded that by restoring the ruined sites to obtain a complete picture of the Luofu in its heyday, Han Huang achieved his goal of supplementing previous Luofu gazetteers from the Ming dynasty.

As one who thought himself obliged to present the Luofu Mountains in perfect condition, Han Huang expressed his ideal of the complete Luofu and in a work that distinguished him from his contemporaries. Consequently, Han Huang chose to interpret the Luofu as a grotto-heaven that had not suffered from destruction. In addition, besides Luofu’s significance to Daoism, Han Huang displayed the syncretism of religions within the Luofu region by paying attention to Buddhist and Confucian sites. By imaginatively reconstructing sites that were then in ruins, Han Huang’s ideal display of the undestroyed Luofu Mountains manifested his general concern over the intactness of an environment where the three major religions harmoniously co-existed. In Han Huang’s mind, the sacred space created by the grotto-heaven may be an ideal protection for all the sacred sites of the religions that thrived in Luofu against the profanity of the turmoil outside.

Funding

This research receives no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | (Kirkova 2016, p. 184). Zhang Junfang 張君房 (active 1001), Yunji qiqian 雲笈七籤 [Seven Tablets from a Cloudy Basket] (Beijing: Zhongyang bianyi chubanshe, 2020), 122 juan, vol. 1, 27.301. |

| 2 | To ensure conciseness and readability, in the following parts of this article, the term “Luofu” refers to the region that formed by the Luofu Mountains, which is synonymous with “the Luofu Mountains”. The name Luofu, as a symbol of its sacredness, stands for the Luo 羅 and Fu 浮 mountains which join together from afar; the Fu peak was, according to Daoist mythical tales, deified as a floating island that originally belonged to Penglai 蓬萊, the divine realm that confers immortality to visitors through herbs and mineral substances found on the island. (Goossaert 2013, vol. 1, p. 723; B. Lai 2010, p. 2; Zhang and Chen 2020, p. 13; Koon 2014, p. 49; Littlejohn 2019, pp. 16, 155). Han Huang (1600 juren), Luofu yesheng 羅浮野乘 (Unofficial History of the Luofu Mountain), 6 juan, Qing Kangxi keben, repr. in Siku quanshu cunmu congshu, ed. Siku quanshu cunmu congshu bianzuan weiyuanhui 四庫全書存目叢書編纂委員會 (Jinan: Qilu Shushe, 1996), Shibu, vol. 232, 1.4a–b (482). |

| 3 | Most references to Luofu yesheng are to the version reproduced in the Catalog of the Complete Writings of the Four Repositories (Siku quanshu cunmu congshu 四庫全書存目叢書), which is the most widespread version. Detailed information on this version will be given in the second section of this article. On a separate note, unless specifically indicated, the translations are the author’s own. |

| 4 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, xu 序 2, 3a–4b (477). The word yesheng 野乘 means yeshi 野史, literally means “unofficial history”, and represents the gazetteers or historical records that were privately edited, printed, and published without the support of the local administration. See (Dennis 2015, p. 128). The character sheng has two pronunciations, shèng and chéng. The correct pronunciation can be seen in (Zhang 1997, p. 39). In the bibliography of his monograph, Timothy Brook mistakenly dated Luofu yesheng as a work edited after 1644, but Han Huang’s own foreword clearly stated that this was completed in the yimao year of the Chongzhen Reign (1611–1644), which would be 1639. See (Brook 2020, p. 389). For the birthplace of Han Huang, see Song Guangye 宋廣業 (1649–1720), Luofu shan zhi huibian, 22 juan, Qing Kangxi keben 清康熙刻本, repr. in Luofu shan zhi, Huqiu shan zhi, Huqiu zhuiying zhi lue 羅浮山志、虎丘山志、虎邱綴英志略 (Gazetteer of the Luofu Mountains, Gazetteer of the Huqiu Mountain, and Concise Gazetteer of Selected Sites of the Huqiu Mountain), ed. The Palace Museum 故宮博物院 (Haikou: Hainan Chubanshe, 2001), 6.28a–b (121). |

| 5 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, xu 2, 1b (476). |

| 6 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, xu 2, 1a (476). |

| 7 | Song Guangye, Luofu shan zhi huibian, shumu 書目, 3b (26). |

| 8 | Wu Zhenfang 吳震方 (1679 jinshi), Lingnan zaji 嶺南雜記 (Random Records of Lingnan), 2 juan, Qing Kangxi keben, repr. in Siku quanshu cunmu congshu, ed. Siku quanshu cunmu congshu bianzuan weiyuanhui (Jinan: Qilu Shushe, 1996), Shibu, vol. 249, 1.20a-b (507). |

| 9 | It should be pointed out at first that although discussing Confucianism together with Buddhism and Daoism, two major religions, this article does not exactly refer Confucianism as a religion but a system of ethics with religiosity. As Zongli Tang argued, Confucianism “is not a religion but plays a religious role in China”. However, Confucianism, as a core aspect of Chinese civilization, requires Chinese people to follow a series of moral and ethical codes and conduct familial or heavenly rituals, giving religiosity to its architecture, which is the reason this article refers Confucian architecture as “religious sites” in following sections, just as what Nancy Steinhardt summarized, Confucian architecture “may be considered among shrines or may be included in religious architecture”. See (Tang 1995, p. 270; Steinhardt 2014, p. 52). |

| 10 | Song Guangye, Luofu shan zhi huibian, 6.28a–b (121). |

| 11 | Ibid; a fragment of a court memorial was presented to the Chongzhen 崇禎 Emperor (r. 1627–1644), by a group of officials that included Han Huang, who signed his name as “Magistrate of Qingtian” (Qingtian zhixian Han Huang 青田知縣韓晃), see Bi Ziyan 畢自嚴 (1569–163), Duzhi zouyi 度支奏議 [Memorials of the Ministry of Finance], 119 juan, Ming Chongzhen keben 明崇禎刻本, repr. In Xuxiu siku quanshu 續修四庫全書, ed. Xuxiu siku quanshu bianzuan weiyuan hui 續修四庫全書編纂委員會 (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1995), vol. 485, 19.117b (499). |

| 12 | Song, Luofu shan zhi huibian, 6.28a–b (121). |

| 13 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, 1.1a–41b (479–499). |

| 14 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, 2.1a–54a (500–526). |

| 15 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, 3.1a–25a (527–539). |

| 16 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, 4.1a–37b (539–557). |

| 17 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, 5.1a–23a (558–569). |

| 18 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, 6.1a-21a (569–579). |

| 19 | Liang Shanchang 梁善長 (1739 jinshi), Guangdong shicui 廣東詩粹 [Selected Poems in Guangdong],12 juan, Qing Qianlong keben 清乾隆刻本, in Siku quanshu cunmu congshu, ed. Siku quanshu cunmu congshu bianzuan weiyuanhui (Jinan: Qilu Shushe, 1996), Jibu, vol. 411, 10.13a (250) |

| 20 | Song, Luofu shan zhi huibian, 6.28a–b (121); (J. Li 2016, p. 94). |

| 21 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, xu 2, 1–2 (476). |

| 22 | See note 10 above. |

| 23 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, xu 2, 2b (476). |

| 24 | The earliest one that contains such images of specific sites is Han Mingluan’s 韓鳴鸞 (1582 juren) Luofu zhilue 羅浮志略 (Concise Gazetteer of Luofu), which was published in 1611. This gazetteer will be discussed in later sections of this article in comparison to Yesheng. See Han Mingluan, Luofu zhilue (Tokyo: National Archives of Japan Digital Archive, printed in 1611, the thirty-ninth year of the Wanli reign). |

| 25 | The existing editions include these below: Chen Lian 陳槤 (active approx. 1470), Luofu zhi (Gazetteer of Luofu), 10 juan, repr. in Congshu jicheng chubian (First Edition of the Complete Collection of Books from [Various] Collectanea), ed. Wang Yunwu (Beijing: Commercial Press, 1939), vol. 3000; Huang Zuo 黃佐 (1490–1566), Luofu shan zhi 羅浮山志 (Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Microform Resource mic/890, printed in 1557, the thirty-sixth year of the Jiajing reign); Han Mingluan, Luofu zhilue. Much earlier, during the Song dynasty (960–1279), two influential Daoist priests Zou Shizheng 鄒師正 (active approx. 1225) and Bai Yuchan 白玉蟾 (1134–1229) also wrote Luofu gazetteers. Zou Shizheng’s work may contain detailed images of sites in Luofu; however, its original version and images are unfortunately lost. The main texts by Zou and Bai Yuchan exist only in later historical transcriptions. |

| 26 | Their works can be found in Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, 1.7b–11a (482–484), 1.14a–15a (486), 1.18a-21a (488–489), 1.21a–23a (494–495), 1.36a–b (497), 2.3a (501), 2.4a (501), 2.6b (502), 2.14b–15a (506–507), 2.16b–17a (507–508), 2.21a (510), 2.25b (512), 2.28 (513), 2.31b–32a (515), 2.33b–34a (516), 2.44a (521), 2.52a (525), 3.7a (530), 3.13b–14a (533), 3.15b (534), 3.17a (535), 3.33a-b (538), 34b–35a (538–539). |

| 27 | For further information on Huang Zuo’s panorama and gazetteer, see Huang Zuo, Luofu shanzhi, 1.1b–3a. |

| 28 | Han Mingluan, Luofu zhi lue, 1.105b, 2.12b. |

| 29 | The four sites are the Feiyun Feng, Shangjie Sanfeng, Fenghuang Gu 鳳凰谷 (Phoenix Valley), and Tieqiao Feng 鐵橋峰 (Iron Bridge Peak). Han Huang’s texts can be found in Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, 2.2b–11b (500–505). |

| 30 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, 2.8b (503), 2.10b (504); Han Mingluan, Luofu zhi lue, 1.51b, 1.75b. |

| 31 | The similarities shown in Han Huang and Han Mingluan’s Feiyun Feng texts can be seen in the comparison image. Han Mingluan’s texts can be found in Han Mingluan, Luofu zhi lue, 1.43b, 1.51b, 1.54b, 1.75b, |

| 32 | More information about Li Yaogu can be found in Li Mingwan 李明皖 (dates unknown), Feng Guifen 馮桂芬 (1809–1874), Tongzhi Suzhou fu zhi 同治蘇州府志 [Gazetteer of Suzhou during the Tongzhi Reign], 150 juan, Qing Tongzhi keben 清同治刻本, repr. in Zhongguo difang zhi jicheng 中國地方志集成 [Compilation of Chinese Gazetteers] (Nanjing: Jiangsu Guji Chubanshe, 1991), vol. 8, vol. 2, 64.9b (691); Zhao Hongen 趙宏恩 (?–1759), Qianlong Jiangnan tongzhi 乾隆江南通志 [Complete Gazetteer of the Jiangnan Region during the Qianlong Reign], 204 juan, Qing Qianlong keben, repr. in Siku quanshu 四庫全書 (Taipei: The Commercial Press, 1983), Shibu, vol. 510, 132.17b (859). |

| 33 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, xu 1, 1a–3b (474–475). |

| 34 | In 1701, the year he presented Yesheng to the throne, the Comprehensive Gazetteer entered its second phase. Li was appointed by the emperor to collect gazetteers in Guangdong, which was, presumably, a mission to compile the Comprehensive Gazetteer. For more information on different phases of the compiling of the Comprehensive Gazetteer, see (Dong 2018, pp. 124–25). |

| 35 | It seems that while the Qing court did not cite Yesheng in the Comprehensive Gazetteer, the work was later reproduced by the court in Siku quanshu cunmu anyway. In the Comprehensive Gazetteer, the content regarding Boluo County and the Luofu Mountains briefly introduced the locations, sites, and related myths of the Luofu Mountains and surrounding areas and referred only to the Gazetteer of Commanderies and Empires in the Han Dynasty 漢郡國志 (Han junguo zhi) and Maps and Records of Prefectures and Counties during the Yuanhe reign 元和郡縣圖志 (Yuanhe junxian tuzhi), instead of recording Yesheng. However, Yesheng was held in storage and later collected in the Siku quanshu cunmu during the Qianlong (1736–1796) reign. Being collected in the Siku quanshu cunmu may indicate that Yesheng did not meet the requirement for being referred to and compiled in royal publications. This may be why Yesheng was not mentioned in the Comprehensive Gazetteer. See (Zhongguo Chuban Nianjian She 1995, p. 172); Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, xu 1, 2; Mujangga 穆彰阿 (1782–1856), Jiaqing chongxiu yitong zhi 嘉慶重修一統志 [Re-edition of the Comprehensive Gazetteer of Great Qing during the Jiaqing Reign] (Shanghai: Commercial Press, 1934), 560 juan, Qing Jiaqing keben 清嘉慶刻本, 445.8b–10a. Although the Jiaqing version is a re-edition of the previous Comprehensive Gazetteers published during the Kangxi and Qianlong reigns, it is considered the most comprehensive version, as it includes the content of previous versions. Related information on the Jiaqing Comprehensive Gazetteer can be found in (Niu and Zhang 2008, pp. 144–46). |

| 36 | Although Han Huang’s original version is lost, two Qing versions still exist. One is in the collection of the National Library of China, the other in the Shanghai Library. The National Library version was published during the Kangxi reign (1661–1722), earlier than the Shanghai version, which was published during the Qianlong reign (1736–1796). Both were printed based on Han Huang’s original form and contain two prefaces, the first being a recommendation of the book written by Li Yaogu and the second a general introduction by Han Huang. The two versions have three slight differences from each other. The first is in the preface. In books printed in dynastic China, prefaces were usually placed before the main text and accompanied by their author’s official ranking and name on the last page. In the Shanghai version which is compiled and reproduced in the Siku quanshu cunmu congshu, the first preface seems to be anonymous, while it is clear that the second preface was written by Han Huang. However, in the National Library version, the first preface has one additional page that shows the name of the author of the preface, Li Yaogu, along with his official position, magistrate of Huizhou, and the date he wrote the preface, 1701. In comparison, the Shanghai version is entirely missing the page documenting Li Yaogu’s information. The author records the additional content in the Shanghai version as follows: “…in its [the Luofu Mountains] prime. On the changzhi day [the winter solstice, the twenty-second day] of zhongdong [the second month of winter, December] in the xinsi year [the fortieth year] of the Kangxi reign of the Qing dynasty, on an official mission on the main peak during the term of the Magistrate of Huizhou, Li Yaogu, the Grand Master Exemplar, meticulously wrote this preface (……逢其盛時焉。康熙四十年歲次辛巳仲冬長至日,中憲大夫知惠州府事主峰李遙穀謹撰)”. The second is the list of compilers. The National Library version was compiled by Hang Huang, his song Han Lütai 韓履泰, and his grandsons, Han Yinguang 韓寅光 and Han Shenrui 韓申瑞, but in the Shanghai version, in addition to these names, there appears another compiler, Han Huang’s great-grandson Han Weilei 韓為雷. Han Huang’s grandsons lived during the Kangxi reign, while his great-grandson, Weilei, lived during the Qianlong reign, as Weilei was appointed as an official in 1756, the twenty-first year of the Qianlong reign. Therefore, the Shanghai version was reproduced after the National Library version. See Chen Shouqi 陳壽祺 (1771–1834) et al., Fujian tongzhi 福建通志 (Comprehensive Gazetteer of Fujian), 277 juan, Qing Tongzhi keben, repr. in Zhongguo shengzhi huibian 中國省志彙編 [Compilation of Chinese Provincial Gazetteers] (Taipei: Huawen Shuju, 1968), vol. 9, 109.6b (2077). |

| 37 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, xu 1, 1–3 (476–477). |

| 38 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, xu 1, 1 (476). |

| 39 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, 1.4b–5a (481). The translation is by Kunio Miura, see (Miura 2013, p. 368). |

| 40 | Gil Raz demonstrated that the original notion was of a single group of 36 cavern heavens. See (Raz 2010, p. 1430). |

| 41 | Zhang Junfang, Yunji qiqian, 27.301. |

| 42 | The system of the grotto-heaven refers to the categorization within the “Grotto-Heavens and the Blissful Lands”: ten “Major Grotto-Heavens”, thirty-six “Minor Grotto-Heavens” (xiao dongtian 小洞天), and seventy-two “Bllissful Lands” (fudi 福地). The concept of a grotto-heaven may originate from a former sacred geographic system, the twenty-four dioceses (zhi 治) listed by the nascent Way of the Celestial Masters (Tianshi Dao 天師道) during the Han 漢 dynasty (202 BCE–AD 220). Inspired by the local mythology surrounding holy sites in the Jiangnan 江南 region, the Shangqing lineage began to methodically catalog the grotto-heavens. Over the Jin 晉 dynasty (266–420), the system of the grotto-heavens was already founded and widely circulated, but only thirty-six grotto-heavens were listed, instead of being divided into three categories. Throughout the historical accounts, the list of thirty-six grotto-heavens appeared earlier than the “Grotto-Heavens and the Blissful Lands”. See (Miura 2013, p. 368; Raz 2010, p. 1432; Xu 2021, p. 283). |

| 43 | Zhang Wanfu 張萬福 (active around 712), Jiao sandong zhenwen wufa Zhengyi mengwei lu licheng yi 醮三洞真文五法正一盟威籙立成儀 (Complete Ritual for Offering to the Gods of Registers of the Three Caverns, the Five Methods, and the One and Orthodox Covenant), in Zhengtong Daozang 正統道藏 [Daoist Canon in the Zhengtong Reign] (Tapei: Shin Wen Feng Print Co., 1985), vol. 48, 1 (203). The translation is in (Verellen 1995, p. 280). |

| 44 | By elaborating on this environmental condition, Qu Dajun explained the meaning of the words “Zhuming Yaozhen” and linked it to the geographical location of the Zhuming Dong and its fengshui situation. Qu explained that the Zhuming Dong is surrounded by mountains and peaks, forming the “Aoshi 奧室” in feng shui 風水 (geomancy) theory, which refers to the layout of a deep, secluded residence, which the Aoshi constructed in the middle of the void. Attributed to the Aoshi is a trigram of “Li 離” symbolizing burning fire. Therefore, the so-called “Zhu Ming Yao Zhen” is the central area where air and fire converge. See (Guangzhou Shi Daojiao Xiehui 2018, p. 6). |

| 45 | Chen Lian, Luofu zhi, 1.3; (Eliade 1987, p. 10). |

| 46 | Chen, Luofu zhi, 1.1. |

| 47 | Huang, Luofu shan zhi, xu, 1a. |

| 48 | Han Mingluan, Luofu zhi lue, xu 2, 4b. |

| 49 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, 1.4a–b (481). |

| 50 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, 2.1a–b (500). |

| 51 | Tao Hongjing 陶弘景 (456–536), Zhen gao 真誥 [Declarations of the Perfected] (Changsha: Commercial Press, 1939), 11.142. The translation can be found in (Raz 2010, p. 1435). |

| 52 | Zhang Junfang, Yunji qiqian, 8.141. |

| 53 | Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane, 29. |

| 54 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, xu 2, 3b (477). |

| 55 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, quanci, 1a–b (478). |

| 56 | The category of unofficial history was considered supplementary historical materials for the official history, which may be why Han Huang named his book Yesheng. During the Ming dynasty, literati such as Wu Kuan (1435–1504) and Ji Zhenlun (active approx. 1600) acknowledged that unofficial history is just as important as official history:

See Wu Kuan 吳寬 (1435–1504), Jiacang ji 家藏集 (Anthology of my House), 77 juan, Ming Zhengde kanben 明正德刊本, repr. in Sibu congkan chubian 四部叢刊初編 [First Edition of the Selected Publications from the Four Categories] (Taipei: Commercial Press, 1967), Jibu, vol. 83, 25.152b; Ji Zhenlun 紀振倫 (active approx. 1600), “Xu yinglie zhuan xu” 續英烈傳敘 (Preface to the Sequel to the Legends of Heroes), in Xu yinglie zhuan 續英烈傳 [Sequel to the Legends of Heroes] (Taiyuan: Shanxi Renmin Chubanshe, 1998), 5. |

| 57 | Chen Botao 陳伯陶 (1855–1930), Luofu zhinan 羅浮指南 (Guidebook of Luofu), 1 juan, repr. in Zhongguo daoguan zhi congkan 中國道觀志叢刊 [Compilation of the Gazetteers of Chinese Daoist Abbeys] (Nanjing: Jiangsu Guji Chubanshe, 2000), vol. 36, 1.8a (545). |

| 58 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, xu 2, 3a (477). |

| 59 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, xu 2, 4a–b (477). |

| 60 | See note 59 above. |

| 61 | Tao Qian 陶潛 (365–427), Tao Yuanliang shi 陶元亮詩 [Poems by Tao Yuanliang (Yuanming)], 4 juan, Mingmo keben 明末刻本, repr. in Siku quanshu cunmu congshu, ed. Siku quanshu cunmu congshu bianzuan weiyuanhui (Jinan: Qilu Shushe, 1996), Jibu 集部, vol. 3, 4.34a–35b (216). |

| 62 | The translation can be found in (Fang 1980, pp. 180–81). |

| 63 | Tao Yuanliang shi, 4.34a–35b (216). |

| 64 | (Weber 1946, p. 268). Furthermore, as argued by Ying-shih Yü, the influence of Confucianism ideologies was ubiquitous in both bureaucratic and business worlds, making the thoughts of Confucianism more prevalent in Chinese society. See (Yü 2016, p. 214). |

| 65 | Chen Lian, Luofu zhi, 1.3. |

| 66 | See note 58 above. |

| 67 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, 4.29a–b (553). |

| 68 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, 4.30a–32b (554–555). |

| 69 | The word Lingnan refers to the region mainly includes Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan Provinces, as well as Hong Kong and Macau. See (Zheng 2015, p. 129). |

| 70 | Yuan Fu 元賦 (active around 1654), Qianshan Shengren heshang yulu 千山剩人和尚語錄 (Quotes of the Monk Qianshan Shengren), 6 juan, Qing Kangxi keben, repr. in Siku jinhui shu congkan 四庫禁燬書叢刊 [Destroyed Books from the Complete Writings of the Four Repositories] (Beijing: Beijing Chubanshe, 2000), zibu 子部, vol. 35, 6.29 (701). |

| 71 | Shen Dacheng 沈大成 (1700–1771), Xuefu zhai ji 學福齋集 (Anthology of the Studio for Learning Fortune), 57 juan, Qing Qianlong keben, repr. in Xuxiu siku quanshu (Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Cubanshe, 1995), jibu biejilei 集部·別集類, vol. 1428, shiji 詩集, 5.10b (282). |

| 72 | Regarding the Buddhist influence on the Luofu Mountains, see (Boluo Xian Difangzhi Bianzuan Weiyuanhui 2011, p. 66); for the Confucian influence, see (Chen 2016, p. 43). |

| 73 | Huang, Luofu shan zhi, 1.1b–3a. |

| 74 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, 2.2a (500). |

| 75 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, 1.9a (483). |

| 76 | Han Mingluan, Luofu zhi lue, 1.44a. |

| 77 | Song, Luofu shan zhi huibian, 5:12b–13a (97–98). |

| 78 | Pan Lei 潘耒 (1646–1708), You Luofu ji 遊羅浮記 [Record of Traveling in Luofu] (Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, 1985), 1 juan, 1.4. |

| 79 | Han Mingluan, Luofu zhi lue, 1.43b. |

| 80 | (C.-T. Lai 2007, p. 79); Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, 2.24a (511). |

| 81 | Huang, Luofu shan zhi, 5.4b. |

| 82 | Chen Botao, Luofu zhinan, 1.8a (545). The text and the development of the Chongxu Guan are comprehensively discussed in Lai, Guangdong Local Daoism, 79. Although relatively late, Chen’s text has long been a major source of information for scholars investigating Daoism in Guangdong, see (C.-T. Lai 2019, p. 31). |

| 83 | Chen Botao, Luofu zhinan, 1.8a (545). |

| 84 | Han Mingluan, Luofu zhi lue, 2.24b–25a. |

| 85 | Han Mingluan, Luofu zhi lue, 2.74a. |

| 86 | Song Guangye, Luofu shan zhi huibian, 3.13a–b (75); Ruan Yuan 阮元 (1764–1849), Chen Changqi 陳昌齊 (1743–1820), Daoguang Guangdong tongzhi 道光廣東通志 (Comprehensive Gazetteer of Guangdong during the Daoguang Reign), 337 juan, Qing Daoguang keben 清道光刻本, repr. in Xuxiu siku quanshu (Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Cubanshe, 1995), vol. 673, 221.611a. |

| 87 | Han Mingluan, Luofu zhi lue, 2.74b–75a. |

| 88 | Chen, Luofu zhinan, 1.1b (532). |

| 89 | Wu Qian 吳騫 (1691 jinshi), Huiyang shanshui jisheng 惠陽山水紀勝 (Marvelous Landscape in Huiyang), 2 juan, Qing Kangxi keben, in Siku quanshu cunmu congshu (Jinan: Qilu Shushe, 1996), Shibu, volume 241, juan 1, Tasi 塔寺, 4a–b (55). |

| 90 | Pan Lei 潘耒, You Luofu ji, 1.2. |

| 91 | Han, Luofu yesheng, 2.35b (517). |

| 92 | Han, Luofu yesheng, 2.35a (517). |

| 93 | Bai Juyi 白居易 (772–846), Baikong Liutie 白孔六帖 [Six Volumes of Bai (Juyi) and Kong (Chuan)], 100 juan, Tang Bai Juyi yuanben 唐白居易原本, repr. in Siku quanshu (Taipei: The Commercial Press, 1983), zibu, volume 892, 99.13a (606). |

| 94 | Chen, Luofu zhinan, 1.4a (537). |

| 95 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, 3.5a (529). |

| 96 | Han Huang, Luofu yesheng, 2.46a–b (522). |

| 97 | Han Mingluan, Luofu zhi lue, 2.4b. |

| 98 | Han Mingluan, Luofu zhi lue, 2.5b–6a. |