2. Protective Mothers

N. N. Bhattacharya argues for the universality of worship of mother goddesses throughout all agricultural civilisations. He articulates the hypothesis that the material mode of life of a people ordinarily provides the rationale for the type of deity and the manner of worship prevalent in any given society (

Bhattacharya 1971, p. 3). Most scholars agree that it is with the rise of pastoral patriarchal societies that we find the evolution of male deities. However, this development has not resulted in the annihilation of the mother goddess cults; instead, many of these cults have become a part of the institutionalised patriarchal religions that drive the politics and set the norms for their respective societies. We see one example of this pattern in the incorporation of goddesses such as

Pṛthavī, Vāc, Aditī, Uṣās into the Brahmāṇical Vedic pantheon. Simultaneous to this development within the Vedic tradition, we witness a similar process unfolding within the Buddhist (with the goddesses such as Hāritī, Prajñāpāramitā, Tārā, etc.), Jain (such as Ambikā, Gaurī, Padmāvatī, etc.) and ‘folk’ traditions (such as the worship of yakṣiṇī, nāgina, river goddesses), which also witnessed a pattern of continuity and even the birth of many new goddesses.

A mother goddess, in most cases, is not a biological mother but a mother who is able to defend and sustain her children. Goddesses such as Kālī, Cāmuṇḍā, Caṇḍī, and Mahiṣāsurmardhinī, all follow this paradigm. The Sanskrit term used to refer to them, collectively, is

Mātṛkā, which literally means ‘mother’. However, it is only after the 5th century C.E. that we see an exponential growth in the visibility and popularity of mother goddess’ cults. As has been shown by B. D.

Chattopadhyaya (

1994), Kunal

Chakrabarti (

2001), and Tracy

Pintchman (

1994), many ‘regional’ goddesses across the Indian subcontinent were assimilated into several institutionalised religions (Brahmanical, Buddhism, or Jainism) and were thereby conjoined with a great range of stories, legends, rituals, and iconography. This assimilation of a variety of religious cultural traditions gave birth to an array of deities, particularly a diverse range of goddesses having very contradictory characteristics.

David Kinsley pointedly raises the question about the nature and purpose of this variety of goddesses.

What is one to make of a group of goddesses that includes a goddess who cuts her own head off, another who prefers to be offered polluted items by devotees who themselves are in a state of pollution, one who sits on a corpse while pulling the tongue of a demon, another who has sex astride a male consort who is lying on a cremation pyre, another whose couch has as its legs four great male gods of the Hindu pantheon, another who prefers to be worshipped in a cremation ground with offerings of semen, and yet another who is a hag-like widow?

These questions raised by Kinsley accurately encapsulate the growth and diversity of mother goddesses. Thomas Coburn makes two important observations about these goddesses. First, the Goddess

(devī) of the

Devī Māhātmya (Durgā saptaśatī)

5 is not specifically paired with either Śiva or Viṣṇu, thus making this one of the first truly

Goddess Tales (

Śākta Purāṇas) and thereby providing literary evidence for the emergence of an ‘independent warrior goddess’ no later than the middle of the first millennium C.E. Second, many of the goddess’ names are unique to this text, without any precedent in the Vedic corpus—a fact that clearly indicates not only assimilation within the Brahmāṇical tradition but also suggests the birth of new goddess cults altogether (

Coburn 1984). We see similar assimilation of the goddess tradition in other religious systems at this time period as well, most notably Buddhism (

Shaw 2006). In other words, by this time of

Devī Māhātmya, in the middle of the first millennium C.E., the goddess tradition seems to have assimilated itself into the larger Indic cultural nexus, transcending the limitations of such cultic labels as ‘Hindu’, ‘Buddhist’, ‘Jain’, etc.

Through this process of integration discussed above, by the end of the early medieval period in Indian history, we have goddesses of all kinds assimilated into the mainstream Brahmāṇical fold. This process of expansion and integration never ceased and continues on to this very day. During the medieval period, we witnessed the consolidation of the pilgrimage network of Power Seats (

Śākta pīthas) in various parts of the subcontinent.

6Among these newly emergent traditions, we find a great range of mothers who perform very specific tasks for their human children. For example, the Buddhist goddess Tārā, who saves her children/devotees from eight specific fears (

Beyer 2001), the Brahmanical goddess, Annapurṇā,

7 who monitors dietary practices and concerns, or the Buddhist/Brahmanical goddess Hāriti, who is a protectress of children (

Shaw 2006, p. 118). In this way, almost every aspect of life comes to have a presiding deity. In the midst of this centuries-long process of assimilation, a very notable and interesting relationship is formed between the body, health, disease, and their presiding deities. We witness this relationship in all the Indic religious traditions and across vast time periods in Indian history, starting from the Vedic texts in the third millennium B.C.E and extending to Mahābhārata to Suśrutasaṃhitā in the first centuries C.E. up into the present day.

In the Vedic texts, many diseases have been recognised as ‘god-sent’, and hence, gods are an integral part of the cure as well (

Zysk 1985, p. 14). Most significantly, Agni, the god of fire, is identified as both the root cause and cure for most diseases (Ibid., p. 29). Many of the early disease deities were male gods with only a few female deities also being present. A remarkable change in this pattern occurs after the 5th century C.E. when many tribal goddesses are assimilated into Brahmanism. It is at this point in Indian history that disease come to be to be predominantly associated with female deities. Indeed, Binny argues forcefully establishes the binary that from the early medieval period onwards, while medicinal developments came to be associated with the political structure, and therefore linked with male deities, disease, on the other hand, came to be associated with the divine in female form (

Binny forthcoming). It is important to note here that while the male disease deities in the earlier period came from the institutionalised Bramāṇical traditions, the female disease deities of the early medieval period tend to have regional/tribal origins.

This tradition of combining medical knowledge and divinities continues to this day in India. Depending on the time period and specific region, we see variations in terms of which are the newly emergent deities. As deities are symbolic foci for cultures, this pattern highlights the highly malleable and multicultural nature of Hinduism. For example, today, in the northern part of the subcontinent, Śitalā Mātā is a prominent disease-devī; meanwhile, in the south, it is Māriamman, along with a number of more localised goddesses, who commands centre stage in the landscape of Hindu religious imagination that links disease to divinity. In the Buddhist tradition as well, we find today the popular mention of Parnaṣabarī as the goddess of disease, even though she, like Śitalā Mātā and Māriamman, appear only as minor deities in Sanskrit texts.

It is in the

Skanda Purāṇa, a text that can be dated to the 8th century C.E., that we first find mention of Śitalā Māta as a deity who saves people from the pox. The text goes on to provide a description of how she looks and what she does. Like the Vedic male god Agni, she both inflicts and averts disease; hence, she is both benevolent and malevolent. Her worship is recommended for the avoidance of fatal diseases and evil spirits. The

Picchila Tantra describes this same goddess as white-complexioned and seated on an ass, holding a broom in her hands and carrying a pitcher. With her broom, she sprinkles the life-giving water from the ever-full pitcher in order to alleviate suffering (

Jash 1982, p. 190). In line with many other Tantric goddesses of the time, Śitalā Mātā is described here as being naked while carrying a winnowing fan on her head. She is embellished with gold and jewels and mitigates the terrible suffering arising out of painful eruptions. In the

Skanda Purāṇa, she is described as being mounted on a donkey and having as her garments the quarters of the world (i.e., naked). By worshipping her, one turns back the great fear of Pustules (Ibid.).

In her formative period, like many other such goddesses, Śitalā Mātā was worshipped only in an aniconic form as a piece of stone. One of her first artistic representations comes from the 8th-century C.E. Sachiyā Mātā temple at Osian in Rajasthan. In many instances, she is accompanied by the fever demon, Jvarāsur, who is sometimes referred to as her consort. Other times, he is believed to be her servant. Whether as husband or servant, Jvarāsur is an affliction and to fight him off the goddess needs to be placated (

Mukharji 2013).

8A few centuries later, in the southern states in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, we see an evolution of independent goddess shrines associated with the Āmman tradition; like its Sanskrit counterpart,

Āmman also means mother and comes to be associated with the general re-emergence of the goddess tradition in the late medieval period. Indeed, the growth of the Māriamman cult itself can be located in this ‘re-emergence’ of the goddess tradition, which Stein has termed the ‘universalisation of folk tradition’ (

Stein 1980, pp. 237–39). Among these independent goddesses’ shrines,

Āmman shrines have gathered strong popularity. Stein credits the extension of the ritual authority of the state for the development of regional goddess cults and the building of their temple shrines (Ibid.). Binny further argues that the revitalisation of the folk goddess traditions might be viewed as an indication of the incomplete nature of the project of brāhmaṇisation, reflecting a lower caste resistance to the upper caste agenda through the affirmation of folk goddesses such as Māriamman and Pēchiamman (

Binny forthcoming). However, she nuances her argument by pointing out that this binary between Brahmanical and non-Brahmanical communities may be a false premise, as there are also accounts which suggest that Māriamman temples were in existence in both brahmāṇical and non-brahmāṇical villages, even if there were differences in both the composition of the priesthood and aspects of rituality (Ibid.).

Māriamman is most often represented as a young goddess with fangs, a pockmarked face (indicating the scars left behind by pox), and having four arms which hold, respectively, a drum (ḍamarū), a trident (trisula), a scimitar, and a bowl. There are minor variations in her depiction across temples, including being fair-skinned in certain regions but dark-skinned in others (as a further example of India’s multicultural, regional diversity). She has either a five-hooded serpent or a studded arch (kīrti-mukha) above her. She is usually adorned with a necklace of lemon and coriander leaves. Margosa and neem leaves are also used to worship her. There is no mount or vehicle associated with her. In the context of North and Central Kerala, she is almost always depicted with Vāsurimālā, a minor female attendant deity who is regarded to be the agent of diseases as the one who carries the disease to the villages at Māriamman’s orders (Ibid.).

Among these goddesses associated with diseases, two categorisations can be seen very distinctly. One is when the goddess herself is the disease and, hence, can inflict as well as revert the disease; the second is when the goddess will protect (by reverting it) her followers from the disease. Of course, the boundaries between these two are not watertight, and they can have overlaps. Further evolution of the cult of both Śitalā Mātā and Māriamman experienced this overlapping.

Apart from these more prominent cults, each region in the Indian Subcontinent has its own set of local deities which protect and heal the people of the region. In central Uttar Pradesh, while Śitalā Mātā is worshipped more for the general well-being of the children, another Chechak Mātā is worshipped for safeguarding children against smallpox, sometimes also simply referred to as

Mātā. Another goddess, Agiyā-paniyā Devī (fire-water goddess), is worshipped for healing the summer boils on the back of the children. Unlike her more popular counterparts, she has not yet been anthropomorphised and is worshipped solely with a simple offering of water and dung cakes at any crossroad.

9In many parts of Orissa, one finds the worship of a stone kept under neem trees in association with the boils, epidemics and the general well-being of children. Here, we find the title

thākurāṇī10 being used to refer to these aniconic goddesses of diseases.

11 Meanwhile, in the neighbouring region of Bengal, we find the presence of Olādevī or Olābībī as a popular goddess of pox among both Hindu and Muslim communities (

Chatterjee 2021, p. 84), suggesting yet again that that these disease-deities represent and protect the people of a localised area, and are not simply abstract symbols for an entire religion. Indeed, the disease goddesses predominantly flourish within regions and appear transcendent to caste and even religious boundaries. Being expressions primarily of oral, not literary, cultures these goddesses express themselves through fluid, diverse, regionally specific iconographies and mythic narratives. Linked as they are to fluid, ever-shifting oral cultures, these disease goddesses can and often do appear in new forms, addressing newly emergent diseases, and in turn, these emergent forms can be and often are assimilated back into the older pantheons within the practicing communities.

Regional Goddesses

As recent as the late 1950s, in Andhra Pradesh in the village of Nandigudem, there was an outbreak of viral disease among the cattle herd of a herdsman by the name Venkannā. A

yādava (member of the cattle herder caste) tried to prevent the outbreak by sprinkling curd rice, believing that since the goddess who caused the outbreak was fond of it, she would be placated by the curd and quit the cattle. Later, Venkannā was possessed by the goddess Kanaka Durgāmmā and told the villagers that if a temple were constructed for her, she would protect the village. Funds were raised and a temple with the image of Kanaka Durgā was installed. Each year since then an annual ritual procession (

jātara) has been held (

Padma 2013, p. 186). Similarly, many tribes in Andhra such as the Koyas and Sugalis worship goddesses such as Sammakkā, Sonalāmmā, Peddāmmā, and Uppalāmmā, all of whom are regarded as the presiding deities of various viral diseases (Ibid., p. 191). Additionally, in the states of Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand, tribal communities such as Baiga, Pardhan, Santal and Gadaba also worship many goddesses of this nature. The religious universe of the Baiga, for example, comprised some twenty-one goddesses who cause and protect people from various diseases (Ibid.). Curiously, the relationship between the manifestation of the disease and the goddess has been seen in a variety of ways; sometimes, it is her anger, and at other times it is her playful nature that is associated with the respective disease and its cure. In most cases, it is believed that she has come to reside in the body and should be given appropriate respect upon her visitation, which will then lead to her happy departure and curing of the sick.

Among the tribal peoples in India, the practice of worshipping goddesses without any image is common. Typically, we see the emergence of iconography only after the area of influence of the goddess increases and she becomes institutionalised. Most of these goddesses are rural in their origin with no or very little Brahmāṇical intervention, as Binny has highlighted in the case of Māriamman (

Binny forthcoming). Many of the disease goddesses are regarded as hot-tempered, demanding, and fiery. They are deemed ‘wilderness goddesses’ (Raudra Rūpa) and are primarily regarded as the localised deities of the lower castes, whether they be labelled Dalit, tribal or rural folk. High caste Hindus and those who mirror high-caste practices often ignore and shun these tribal-born disease goddesses, being fearful of the idea of possession and the other tantric rituals that are typically associated with low-caste worship (

Srinivas 2021). Regardless, the longstanding process of interaction and assimilation of these cults within the Brahmāṇical religion continues, reflecting the fact that upper-caste Hindus, while fearing the power inherent in tantric tribal practices also seek to harness and institutionalise that power (

Nath 2001, p. 41). The most popular disease goddesses have even come to be associated with the larger cult of goddess Durgā, thereby giving a highly tribal, tantric tone to this pan-Indian mainstream, upper-caste-associated goddess.

In this long series of tribally arisen protective mothers, the most recent addition is Corona Mātā, named after the COVID-19 virus. She currently stands at the centre of this historically rich interaction of folk and Brahmāṇical traditions. Her appearance on social media as well as in the temples at once broadens the approach of the goddess while also convoluting her character.

3. Coronāmātā and Coronāsur

Corona Mātā worship has been observed in various parts of the subcontinent, most notably in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, Assam, Bengal, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala. In many of these places, temples have been erected in honour of the goddess; in others, individual and collective worship (

pūjā)

and even formal Vedic sacrifice (yajñas) have been performed in order to seek spiritual forms of healing and protection from the virus. In yet other places, most notably, in the northern regions, worship has been offered to a goddess without any name or icon. For example, in the case of Agiyā-Paniyā Devī, people here, mostly women, have also gathered and offered water,

neem leaves and some sweets to the goddess for protection from the COVID-19 virus.

12In March 2020, during the first wave of the pandemic in India, we witnessed the erection of a fifty-foot-tall, blue-coloured effigy named Coronāsur

13 in Mumbai on the occasion of

Holī14 as a part of the

Holikā Dahan (ritual burning of Holikā). In 2020, instead of the usual

Holikā Dahan, the effigy of Coronāsur was burned as a form of

Holikā (representing evil). The name given to this entity, Coronāsur, is made up of two words: Corona (name of the virus) and

asur15 meaning ‘demon’ in Brahmanical mythology. Coronavirus here is imagined in the image of demons popular in Brahmanical mythology, having horns, protruding tongue, canine teeth, long black nails, and wearing a garland made up of many small red coloured coronaviruses replacing the traditional garland of skulls (

muṇḍamālā). However, these are not the only attributes carried by Coronāsur. In his one hand, he also carries a board with the text,

ārthikmandī, meaning ‘economic recession’. This addition to the iconography of the demon clearly indicates the awareness of the current circumstances among the makers of the idol. It is also interesting to note here that by giving this attribute to the demon, the responsibility for maintaining the economic stability has been taken away from the governing authorities and has been placed on the head of divine/demonic authority. This responsibility-shift reflects a broader, long-standing, systemic religious attempt to ward off a perceived evil in order to survive a period of medical and economic crisis.

On 20 April 2020, just a few weeks after the first wave of the pandemic hit India, the first painting of a personified SARS-CoV-2 virus emerges. Painted by Monal Kohad, this ‘protective’ goddess is named after the national goddess, Mother India (

Bhārat Mātā) and along with her more common attributes, this time she has a new element: she is holding a severed human head with the image of the spiked Coronavirus (

Kaur and Ramaswamy 2020, p. 75). The severed head here implies decapitation as a part of a ritualistic sacrifice (

āhutī). Right below the decapitated head in the fourth arm, the goddess holds a fiery bowl symbolizing the ritual, while her children pray to her from the corners of the painting. Here, we see an already existing mother goddess, Bhārat Mātā (the nation personified as the mother) taking on an additional duty of protecting her children (the nation’s citizens) from this new ‘demon’.

16The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic gave rise to a proliferation of images and content produced online covering a host of issues, ranging from the anthropomorphizing of the virus to the production of new government policies to deal with both the pandemic and the critiques of the created policies, as well as concerns for the plight of migrant laborers, just to name a few. Through this bombardment of cartoons, images and paintings, many were exposed to the idea of the emergence of a new disease goddess, this time associated with SARS-CoV-2.

Early in the pandemic another image of Bhārat Mātā appeared, this time taking on the role of ‘doctor’—thereby fitting the longstanding pattern of a Hindu deity being at once the affliction and the antidote thereof. As Ramaswamy has argued, this new incarnation

(avatāra) of Bhārat Mātā as a disease-fighting deity primarily manifested herself through the interventions of an apparently secular art practice (

Kaur and Ramaswamy 2020, p. 78). During the first wave of the pandemic, in 2020, no temples for this new goddess were built and no unique worship or ritual emerged. She mostly existed in the digital media and had varied appearances on the basis of the imagination of the artist. Her iconography, at this time, was still unstable, with elements borrowed from the old, the near-new, and the entirely novel; however, some distinguishing features started to emerge to accommodate the new, unique demands of the situation, including the emergent policy of social distancing with which she came to be associated. She is almost always a multi-armed goddess. Interestingly, in the artistic representation, despite the unstable iconography, Corona Goddess was imagined as a combination of Bhārat Mātā and Durgā. Of course, the iconography of Bhārat Mātā itself borrows heavily from the iconography of Durgā/Mahiṣāsurmardhinī (

Ramaswamy 2010).

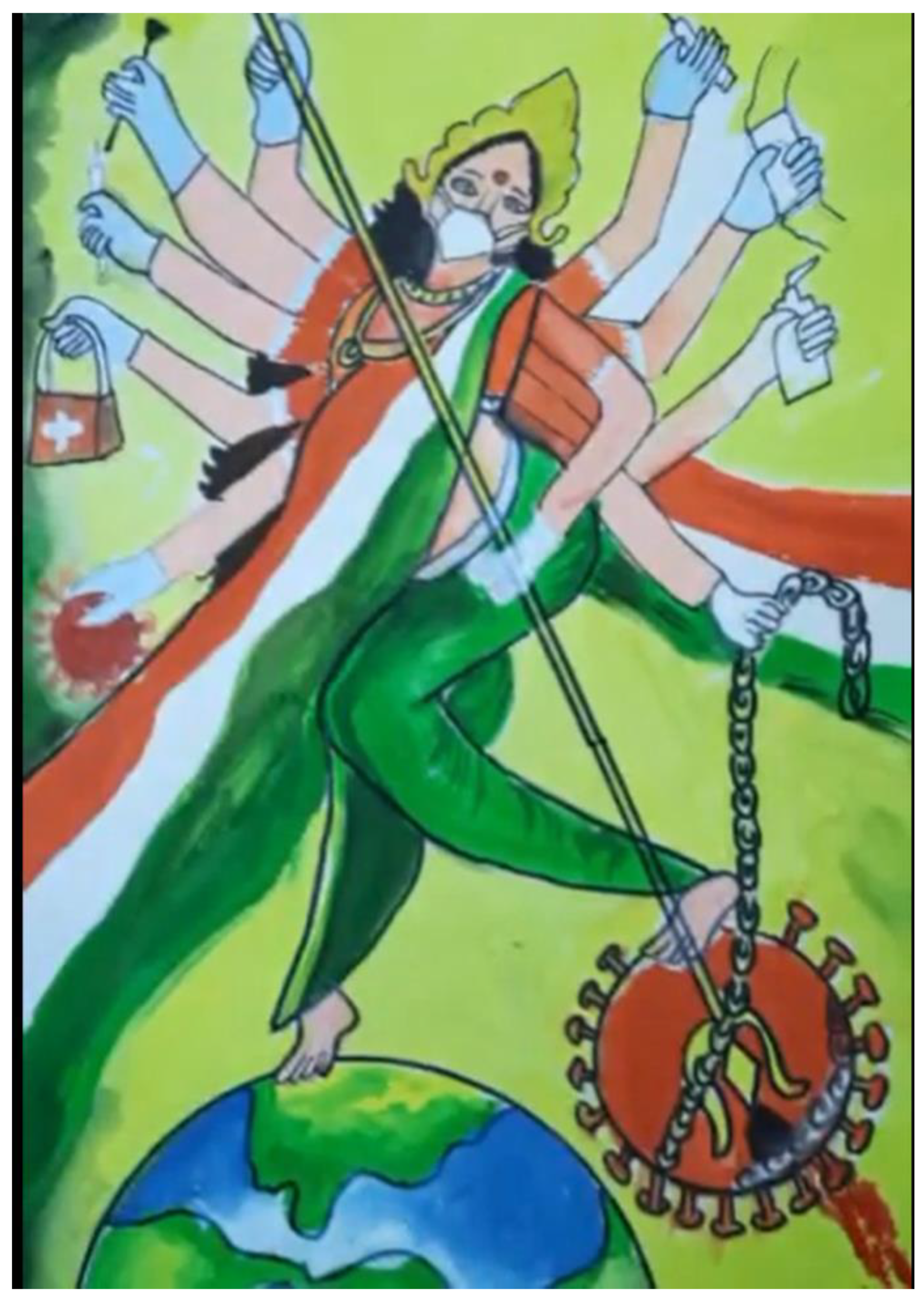

Thus, in Sandhya Kumari’s Mā Bhāratī (see

Figure 1), the new goddess is clothed in the colours of the Indian flag as she stands on a terrestrial globe. In Kumari’s painting, the iconography of the goddess is updated. Resembling the iconic 10-Armed Durgā (Daśabhujā Durgā), this new disease goddess holds unique symbols in her 10 arms, reflective of her context-specific power to ward off the emergent virus. Each of these items are essential to the work of modern secular medicine and public health but are now placed at the service of Bhārat Mātā in her new role as the Corona-disease vanquisher: gloves, sanitiser, mask, syringe, stethoscope, scalpel, and first-aid kit (Ibid., pp. 78–79). The intervention of faith comes in the form of the trident (

trisula), which she wields to kill the demon-virus, thereby reminding the faithful that while modern medical technologies may be divinely sanctioned, the traditional ancient technologies are still necessary.

In April 2020, we saw the insertion of a medical mask and stethoscope unto Abanindranath Tagore’s

Bhārat Mātā.17 This innovation sparked a great variety of diverse images associated with the Corona goddess expressed through electronic mediums. In this phase of development, we witnessed the virus demon identified as an outsider, demonic element with whom the goddess must fight and conquer just as she does in the countless stories of the goddess Durgā, the Demon Slayer. Till this point, our new goddess had not followed the older pattern of disease goddesses but rather that of the mother goddesses. As the goddess came out of the print and digital medium and found her place in the temple, the imagination of the goddess also changed. With this transition, the system of worship and idol making also began to play a role.

Development of Shrines

In the following month of June 2020, in the Kollam district of Kerala, the first installation of the Corona Goddess occurred. A man installed a thermocol sculpture of SARS-CoV-2 (the circular spiked image of the virus) in a shrine next to his household and started worshipping that as the Corona Goddess. He explained that he had been offering worship (

pūjā) for the ‘corona warriors’, or frontline workers, as was reported by

The Hindu.

18 Here, the popular image of the virus itself was deified.

Simultaneously, we also find folk traditions developing around Corona Mātā. Arnold observes that smallpox was conceptualized not as a disease but rather as a form of divine possession by Śitalā Mātā. Consequently, the signs of possession—burning fever and pustules which mark her entry into the body—demand ritual rather than therapeutic approaches (

Arnold 1993, p. 121). A similar practice and belief have also been seen in the case of SARS-CoV-2. In many parts of rural Bihar, rituals in agrarian fields have been offered to the supposed ‘Corona Māi’ (Corona mother) whose anger has been viewed as the cause of the outbreak.

19 As opposed to the digital media imagination, this idea of the goddess follows the tradition of disease goddesses of the Indian Subcontinent very closely, in terms of her iconography, role and associated rituals. In the same year, Maharashtra’s Sholapur district saw its first Corona Mātā temple built by the Pardhi community in order to offer worship and pacify the goddess, much like the beliefs popular in the state of Bihar.

The paradigm of anthropomorphized disease goddess associated with the Corona demon-virus continued through the multiple waves of SARS-CoV-2. In the intervening period between the first and the second wave in India, in the month of October 2020, another

Coronāsur appeared during the celebration of Durgā Pūjā, prominently celebrated in the region of Bengal and some parts of Bihar (see

Figure 2). During Durgā Pūjā, Durgā herself adopted a new role and iconography. In some of the marquees (

pāṇḍālas) designed for the occasion, she was depicted as a doctor similar to Bhārata Mātā, as was discussed above. In this case as well, Durgā left behind her traditional weaponry and instead adorned medical instruments. Along with the goddess, we again see the anthropomorphized form of the virus. Similar to the Coronāsur of Mumbai, the traditional demon, Mahiṣāsur has been replaced with Coronāsur and is being slayed by the goddess (see

Figure 2).

The evolution of Corona Mātā as a separate deity took a more concrete form in the month of June 2021, when two temples were erected and specifically dedicated to her: one in Pratapgarh, Uttar Pradesh, and a second near Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu. As opposed to the first shrine in Kerala, in these temples, the goddess was anthropomorphized and received a whole set of iconographical symbols, including a skull garland (

muṇḍamālā) and a trident (

triśula) (see

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) combined with medical items such as a mask, which by then had become a part of her unique iconography. Due to the spontaneous variations inherent to the goddess and her cult, the iconography in both temples is not homogenised. Hence, we witness different features assigned to the goddess, specific to each cultural context in which her images are produced. The common aspects between the two images are those which have been borrowed from the older iconography of the traditional iconography of Durgā, just as we saw in the case of Bhārāt Mātā.

5. Conclusions

In the 20th century, despite the advances in modern medical technologies, the Indian goddesses still hold an important place in Indian society and culture. For most believers—alongside medical assistance—visiting the temple and asking for blessings is still an equally important aspect of the healing process. Some of the traditional Indian disease goddesses have changed their character over time. Srinivas cites the case of Māriamman in Bangalore and argues that once the threat of plague passed, the goddess became a protector of the drivers in a city with suffocating traffic and now known as ‘Traffic Circle

Amman’. Similarly, on 1 December 1997, World AIDS Day, AIDS Āmma was created by a schoolteacher to spread awareness about AIDS (

Srinivas 2021).

The emergence of these goddesses must therefore be located firmly within the ‘Hindu’ religious system. Being a multicultural, polytheistic system, Hinduism, by its very nature, tends to invent, adapt and re-write the characteristics of its traditional divinities. This innate, creative fluidity stands in stark opposition to the image of the static, rigid tradition proposed by the right-wing ideology in India.

Despite the historical tradition of disease goddesses in the Indian Subcontinent, the circumstances of Corona Mātā are uniquely shaped by the presence of digital media. While the rural form of aniconic worship continues, the new platform of social media provides a completely different and far-reaching platform for the idea of the Corona Goddess to flourish and spread. As we have seen, the first appearance of the goddess was not in a temple or shrine but on social media in the form of a painting. This suggests that we have entered into a new era in which the iconography of a Hindu goddess is no longer solely the jurisdiction of Brāhmins. With universal access to technology, anyone is able to construct images of this new goddess. This caste-transcendent access to technologies for the construction and spread of goddess images has transformed and widened the demography of who can be not just a ‘worshipper’ but a ‘creator’ of the goddess.

In the first phase of this new digitalized era, we see that the goddess was fighting the demon in a way akin to the great goddess, Durgā. In the second, temple phase, she followed the patterns of Indian disease goddesses, whereby the virus became a part of her so that she could conquer it. In this stage, the goddess herself became angry and needed to be pacified with worship and offerings in order to control the pandemic. The second stage appears to have brought on a change in the very nature of the goddess herself. Historically, we see the goddess being classified in the form of either institutionalised Brahmāṇical goddesses or rural/folk goddesses. However, classifying Corona Mātā according to this simple binary is simply not sufficient. With the changes in the mediums and modes of religious beliefs and worship the goddess has also moved beyond the traditional mould of both the pan-Indic ‘Great Goddess’ as well as the localised, rural disease goddess. She is now Corona Mātā, Bhārat Mātā and Mahiṣāsurmardhinī all in one, which not only points towards the intermingling of the religious and political imagination, but also gives it a singular homogenised form.