Abstract

This paper explores the narrative contribution of visual images of nonhuman animals, particularly their contribution to the biblical themes of desire and relation, by considering the exemplum of the Naḥash, commonly known as a serpent or snake. The Biblical textual depiction of this creature indicates that it is not different in kind from humans but only different by degree. Later artists expand upon these possibilities in creative and provocative ways. By using a visual critical approach, the paper reviews the Garden of Eden story, and then examines an array of images that expand and challenge the text.

1. Introduction

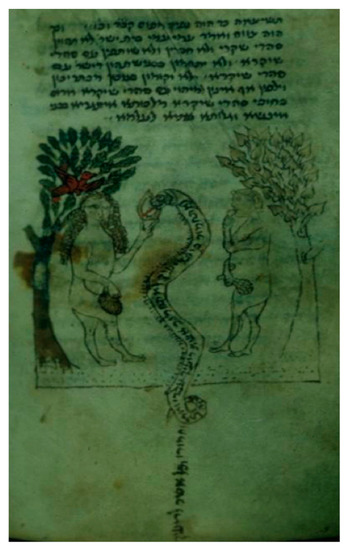

The image (Figure 1) is startling—for its location, visual content, and profound message. It was penned in a 13th Century edition of an Ashkenazi Jewish prayerbook for the High Holidays. The image shows Eve, naked, with a leaf in front of her groin, standing underneath a green tree aflutter with a red bird. On the right, naked Adam, with a leaf in front of his groin, stands beneath a withering tree, eating what may be a piece of fruit. Eve lifts her left hand to give (or take) a fruit from the mouth of a serpentine creature that vertically separates the humans. Its body appears tattooed with a Hebrew inscription of the Tenth Commandment: “You shall not covet your neighbor’s house, you shall not covet your neighbor’s wife or his male or female slave or his ox or his ass or anything that is your neighbor’s” (Exodus 20:14).

Figure 1.

Machzor Vitry (c1300), p. 129a1.

How surprising this image must have been. For in the middle of the holiest liturgical days of the year when Jews fast in penitence, a praying Jew would encounter naked human bodies!2 More, it links creation and revelation, two distinct aspects of Judaic theology that are not even found in the same Biblical book. Even more astonishing: a nonhuman creature looms large between the primordial humans, and despite its physical divisiveness its body conveys the potency of attraction. Its undulating body warns that coveting—desiring—pulses all the time, by everyone, everywhere, for most anyone and anything, and it can come in-between, like the creature itself. Desire itself is unconfinable. It transgresses boundaries, much as the text itself drips beyond the creature’s looping tail. The creature is no mere serpent, a nonhuman animal and nothing more. Rather, in a profound way, it is a “religious subject” by bodily instructing humans in a matter of revelation, and, as we shall see, being entangled in desire itself, just as humans are.

Appreciating the potency of such images is one of this paper’s goals. Another is exploring the narrative contribution of visual images of nonhuman animals, and of desire in particular, by considering the exemplum of the biblical naḥash, commonly known as a serpent or snake. This paper thus sits at the intersection of religion, art, and animals.

2. Imaging Theory

What we will observe vis à vis images of the naḥash are how text and image complement and challenge each other, how they variously explain their subject matter and narrate certain features of human experience. Along the way, questions understandably arise about the nature of the relationship between image and text, artist and author, viewer and reader, representation of and actual animals. As art historian J. Cheryl Exum puts it regarding a biblical story and an artist’s rendition of it: “The biblical writer has to make decisions about how to tell the story. The result is the text. The artist has to decide how to show the story, and the result is the painting” (Exum 2019, pp. 7–8). Since texts and paintings are the result of conscientious decisions, we can ask such questions as, what perspectives are highlighted and which suppressed? Who or what is considered a subject or agent? What does that subject do or indicate? A variety of theorical approaches have emerged that help think through some of these issues when analysing biblical art: visual exegesis, reception exegesis, and, the method used here, visual criticism.

Visual exegesis, for one, likens the artist as a reader of the text, so the image the artist develops is but one interpretation of that text.3 In a way, artists and authors are hardly different insofar as authors, like artists, also place signs and symbols on parchment or stone or wall for some audience to visually engage (Robbins 2017). Yet, in the case of biblical art, artists are never the originators of the story; they are commentators upon it. Theirs are visual readings of the original text. Often these visual readings are influenced by patrons who sought and encouraged visual exegeses that reinforced certain theo-political views.4

Reception exegesis is another, complementary, approach that illuminates a text by putting it into conversation with other genres and times.5 Such work demonstrates the myriad ways a text like the Bible is received or appears in cultural expressions. The meaning of a source, whether textual or visual, thus emerges from the “fusion that results from the dialogue between a reader and the text—a fusion of two historical and cultural interpretive ‘horizons.’” (Gray 2016, p. 407). Both dialogue and fusion serve as metaphors for the creation of something that is bigger, better, or different than either of the contributing parties, that is, something beyond both source and interpreter(s). It is the engagement between these two parties that fascinates the modern scholar in this methodological approach.6

Visual criticism, the approach employed here, deploys visual exegesis as a hermeneutical tool to extract lessons about a biblical text. In this method, visual images serve as tools to explicate, expand and challenge biblical sources; hence the term criticism.7 Instead of situating art and artists into their historical contexts as do the other approaches, what animates the scholar here is “the narrativity of images—reading them as if, like texts, they have a story to tell—and reading an image’s ‘story’ against the biblical narrator’s story” (Exum 2019, p. 7). This visual story “is not a representation, something ancillary to a document in another language. It is, rather, a presentation that permits a basic human theme to become manifest in the immediacies of the worshipper [or viewer]. It is, therefore, a true hermeneutic” (Dixon 1978, p. 40).

Art is thus understood to be and is used like all the “other forms of criticisms (historical, literary, form, rhetorical, etc.) in the exegete’s toolbox” (Exum 2019, p. 7). Critically understanding a biblical story thus involves both textual and visual commentaries—which is what this project aims to do.8 My effort here is to better understand the ways artists challenge and expand upon a biblical story (Genesis 2:4b–3:24), and especially the ways in which they portray and deploy the naḥash to highlight certain issues, like desire, that often go underappreciated in conventional (and textual) readings. As I discuss below in the conclusion, I am curious how these images get at the “deeper structures” of human experience, that is, how they participate in this larger narrative.

3. Imaging Animals

Depictions of nonhuman animals in religious art has a rich history. Perhaps most famous are medieval bestiaries. These colorful tomes catalogue animals according to biblical classifications: beasts, birds, reptiles, and fish. In addition to images of each animal, bestiaries offer “history, legend, natural characteristics, and symbolism” by pulling from Aristotle’s Historia Animalium and a third-century Alexandrian anthology of curious creatures called Physiologus.9 Bestiaries were intended to be instructive and pedagogical, often with moral overtones and lessons. In short, an animal’s image teaches something. This maps closely to what scholar of religion and animals Aaron Gross calls “symbolic” animals “who are invoked—whether in the world or in texts—overwhelmingly or at least primarily because of some other specific meaning that they designate for humans” (Gross 2015, p. 11). According to Gross, because they serve overwhelmingly as symbols of something other than the actual animal species the image represents, it is not “actual animals” but the lesson that predominates. The intended meaning of a textual passage may say nothing about biological animals. These “symbolic animals” stand in contrast to another species of animal Gross identifies: animals that function in part as “the animal”. These are contexts in which rather than, say, a dove symbolizing peace, the dove stands in for all animals in contrast to “the human”. Gross argues that animals depicted in religious contexts, art included, when not symbolic, often function at least in part as a representative of the category “animal” in contrast to the categories of “human” or “divine”.

The visual images of nonhuman creatures this paper will discuss are not only generally symbolic in Gross’s sense but also can be viewed to represent in one way or another something like what Gross calls “the animal”, a category “which configures animals as the root other of the human” (Gross 2015, p. 10). At stake in arguing that images of the naḥash engage “the animal” and go beyond bestiary-style symbolism is an insistence that, among other intentions and functions of such art is reflection, mediation, or perhaps even resistance to dominant Christian ideas about animality, humanity, and divinity as such. The naḥash functions as both a unique character and, simultaneously, as a representative of a being that is neither human nor divine. However, while the naḥash is not human, it nonetheless shares a great deal with humans, inviting us to wonder where similarity ends and otherness begins.

The naḥash, as it appears in the predominantly Christian art surveyed here, does seem to function to invite reflection on categories like animality, humanity, and divinity, but not in a way that simply supports ideas about these all-important Christian (but not necessarily biblical) categories already crystalized in Christian dogma. Images of the naḥash, as we will see, can productively be viewed as a form of narrative theology and biblical interpretation, and, as such, we cannot know in advance if a given image will, for example, imagine a world in which there is a hierarchal chain of being—divine-angelic-human–animal-demonic—or a world more porous and where different forms of life interact more fluidly. Indeed, whether to view these images as participating in anthropocentrism or challenging it can be a difficult matter of interpretation.

For example, when the naḥash is portrayed textually or visually as a therianthrope, that is, as an entity that combines human features like, say, arms or buttocks, with nonhuman characteristics like, say, a serpentine tail, is this an expression of anthropomorphism, of an impulse to shape (other) creatures in and with human form? One could answer in the affirmative: it visually bespeaks a kind of anthropocentrism in which humankind is assumed to be the measuring stick against which other creatures are to be assessed and portrayed. It may also be possible to avow a converse position: humans look like animals and not the other way around. Or, following archeologist John Parkington who asserts that “therianthropes are visual examples of beings that cannot be distinguished as either human or animal”, it is better to speak in terms of indistinction (Parkington 2003, p. 141). Humans share in animal morphology, insofar as humans also have faces, bodies, limbs, etc., as do so many other nonhuman creatures, and therianthropic imagery testifies to this fact. A lesson of these images seems to be that whatever differences may exist between humans and others, they are differences of degree and not of kind. Humans are not a different kind per se than animals, only different from them in varying degrees.

Such issues lead into thorny discussions of the concepts of kind and species. When the Bible says God creates different types of flora (e.g., grasses, herb-yielding seeds, fruit-yielding fruit trees) and fauna (e.g., sea animals, swarming creatures, flying birds, creeping creatures, tannanim or sea monsters, and fish, and land animals such as cattle, creeping things, wild beasts) (Genesis 1:11–12, 20–21, 24–26)—it refers to them as kinds (minim). These nonhuman animal kinds are grouped by broad zoological niches: some are aquatic, others aerial, and many terrestrial. Could one kind breed with another kind? The biblical text seems to think so, even as it discourages doing so (See Leviticus 19:19). Later rabbinic sources go on to rule that even though two kinds may appear similar and mixing them may be plausible—it is impermissible.10 However, is a “kind” a “species” or perhaps a “variant”? This is not the place to get into that debate, fascinating as it may be.11 Rather, a different issue is at play here, the issue of preference. Specifically, is one kind or species preferrable to another? This begins to tread on the topic that in modern terminology is called speciesism. Though there are many forms of speciesism, what is meant by it here is the preference of one species (or kind) over another when they are juxtaposed or in conflict. Curiously, the story of the Garden of Eden offers both a divinely endorsed anti-speciesist perspective and a humanly embraced speciesist one. Later commentators—textual and visual alike—challenge the latter.

Another reason the naḥash is a good test case for this discussion of religions, animals and art is because it is a liminal creature that shares a great deal with the humans.12 In the Garden of Eden story, the naḥash is not a creature (to be) eaten by humans even though it knows a great deal about (human) eating. Though many might assume it to be a creature ruled by instinct, it knows about God and God’s rules and apparently has sufficient freedom of will to do otherwise. It is neither domesticated nor completely wild.13 As such, it is both sociable and troublesome. It initially appears in the story as a speaking creature yet leaves in silence. It moves from being familiar to being alien, a welcomed presence to one that is repulsed. Being neither completely like nor radically unlike the humans, the naḥash is an embodiment of continuity between humans and nonhuman animals.14 Its very existence and interactions with the humans throw open questions about humanness, otherness, and relating.

Readers less familiar with the biblical narrative may wish to skip to the overview of the Garden of Eden story provided in the Appendix A below before continuing.15 Our contention that relating is a, if not the, central theme of this narrative. In her comments on this creation story, Latin American feminist scholar Ivone Gebara argues that “everything that exists is relation and lives in relation, a vital energy in which we exist, a primary mystery that simply is”.16 Understanding existence and transcendence in terms of relation is, in her view, a form of disobedience encouraged by the naḥash. One feature of relating that the naḥash highlights is desire. This is evident both in the biblical text and in the visual depictions presented below. Desire simultaneously troubles and excites, and depictions of the naḥash indicate that desire flows in multiple ways, beyond binaries and past species.

4. Seeing Desire in Eden

Why desire? Desire, according to biblical scholar Carol Newsom, is “a quality intrinsic to our prehuman state and capable of mobilizing the will over against a prohibition. In this narrative [of the Garden of Eden] it is desire that serves as the mechanism by which decisive change is set in motion” (Newsom 2021, p. 122). Furthermore, how does this mechanism work? Newsom contends that “desire is always something for something, and so it is a form by which persons transcend themselves” (ibid.). Desire thus pulls, inspires, incites one to reach beyond oneself. Desire, according to philosopher Emmanuel Levinas, “is an aspiration that the Desirable animates; it originates from its ‘object’; it is revelation” (Levinas 1969, p. 62). This revelation is a rupture or interruption of the ego for which the ego may even sacrifice its own happiness. In desire, the self transcends itself for and toward the other. The uniqueness or hiddenness of the other serves as a kind of voluptuousness, an obscurity that ever tantalizes, never to be possessed, and yet paradoxically is considered necessary for and to the self (see Levinas 1969, pp. 264–65; Newsom 2021, pp. 122–23).

The therianthropic naḥash stimulates desire and itself desires. Through the art below we will see that in some instances the naḥash inspires the humans to transcend their speciesist attraction to and for each other, whereas in other scenes it transcends its own kind by seeking the humans’ attention and ardor. Either way, the art suggests that desire transcends species. The text arguably hints at this (again, see the Appendix A below for a more detailed review of the story). For why would God curse Eve so that her urge will be for her husband (v’el ’ishech t-shukatech), for a conspecific?17 Perhaps before this incident, her desire moved in a different direction other than toward or for Adam (alone).18 Recall, too, that just moments before this Eve perhaps implies the naḥash’s desire for her when she told God it duped her (hisi’ani), a verb that connotes marriage (Genesis 3:13). Indeed, many rabbinic interpretations found in Midrash and in medieval biblical commentaries contend that the naḥash wanted to marry her, 19 often adding that earlier in the biblical narrative when the naḥash saw Eve and Adam in their ’arum-ness, in their nakedness, it observed them engage in sexual relations, which aroused in it a desire for Eve if not both of them.20

Visible in the paintings below, desire also pulses in multiple directions in the Garden of Eden. These images were chosen—curated, if you will—from the myriad visual treatments that critically engage the Biblical text.21 They have been selected and organized chronologically not only as an example of a longstanding meditation on animals in the Christian context, but also for illustrating the ongoing presence and potency of desire in human and human-nonhuman relations. Collectively they challenge conventional presumptions that meaningful relating and desiring beyond “kind” or “species” cannot or should not be experienced, or that transpecific relations are not divinely sanctioned.22 In so doing, these few images offer generative readings of the Biblical text. Such tensions and differences between the textual narrative and these visual narratives can, according to Exum, “point to problematic aspects of the text and help us ‘see’ things about the text we might have overlooked, or enable us to see things differently, or even make it impossible for us to look at the text again in the same way” (Exum 2019, p. 7). What follows, then, is not art history as such but visual criticism, which contends that viewing an image can inspire new readings of text. As we hope you will see here, art of nonhuman and therianthropic animals can change how we understand not only the Garden of Eden story but also ourselves, others, otherness, relating and desire itself.

5. Seeing Edenic Desire Undulate

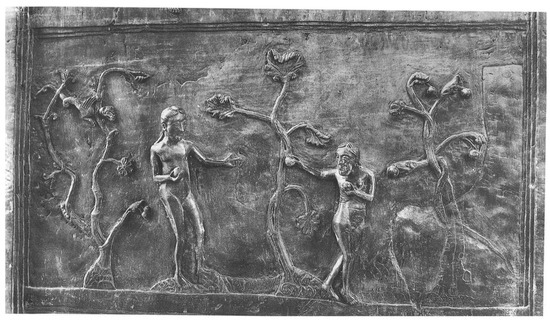

Consider, for example, the giant bronze doors forged and attached to St. Michael’s Church in Hildesheim about a thousand years ago (Figure 2). Made of two columns of eight panels each, one side depicts scenes from the Garden of Eden and the other side the birth, life, and death of Jesus.23 On the left-hand side, the third and fourth panels down from the top present Adam, Eve and the naḥash. In the third the naḥash is a serpentine creature, wound around the Tree of Moral Knowledge. It extends its head toward Eve with a fruit in its mouth. Though relatively close to the naḥash, Eve twists away from it. She has two fruits, one in each hand. She reaches with her right hand toward Adam, who with a slight lean away stands at a distance from both her and the naḥash. He already has one fruit in his right hand yet extends his left as if to grasp the one Eve offers. The artistic intent may be for each of the four images of interaction with the fruit to represent a different moment in time: the serpent pointing Eve to the fruit, Eve taking the fruit, Eve offering the fruit to Adam, and Adam receiving the fruit—which challenges the viewer to rethink the temporality of Genesis 3:6.

Figure 2.

St. Michael’s Church, Hildesheim (1001–1031)24.

Eve’s twisting body is significant and will be a visual trope repeated for centuries to come. Her lower half walks toward the naḥash, while her face and upper torso orient her gaze toward Adam. She is torn about which other—human or nonhuman—she desires or wants to be with. This ambivalence speaks to the notion of an ontological bifurcation, that humans are comprised of minds and bodies, and that they can and do lead people in different directions. Eve’s uncertainty centers and animates the scene.

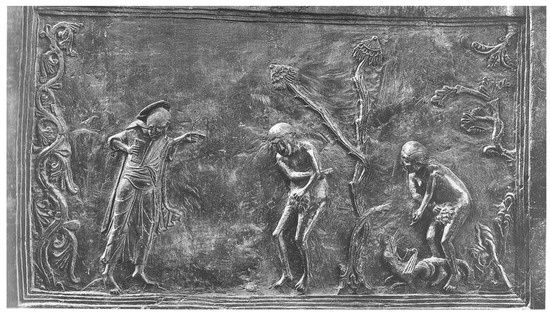

The scene in the next panel down (Figure 3) is of God interrogating Adam, Eve and the naḥash. At the far left, God stands with an aggressive posture and an accusatory left hand extended at them, the right hand holding some kind of document. Adam cowers in the center, his left hand holding leaves over his genitalia and his right pointing behind him toward Eve. Though her head is turned toward God, Eve crouches low, her right hand holding leaves over her groin and her left hand pointing down to the naḥash. The naḥash now is a hybrid creature, part dragon with wings and forelegs, a serpentine tail, and its snout spits flames up toward Eve.

Figure 3.

St. Michael’s Church, Hildesheim (1001–1031)25.

This may be one of the earliest depictions of the naḥash as something other than ophidian. Its tail sneaks between Eve’s legs, a gesture indicating a sexual encounter or the desire for such intimacy. By focusing on the moment God tests humans’ willingness to accept responsibility for their actions (see Genesis 3:11), the artist shows in three-dimensional detail the humans’ penchant to deflect (Genesis 3:12–13). Adam stands at the center, body bowed, eyes cast downward, exuding shame while casting blame upon Eve; Eve, though bent even lower, at least has the courage to face the accusing God while she moves the blame on to the naḥash. Being the last in the blame chain, the naḥash apparently explodes in hot protest.

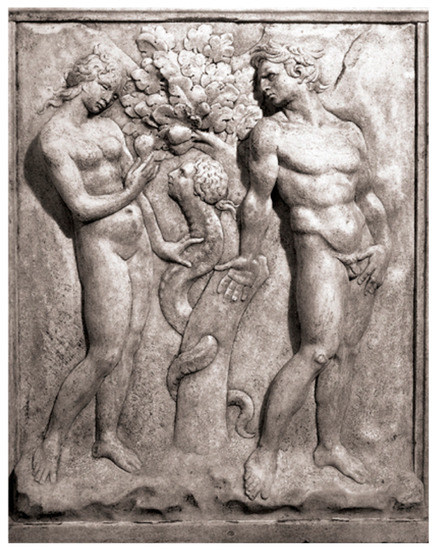

In the following stone relief (Figure 4) by Jocopo della Quercia in the mid-15th Century a therianthropic naḥash winds its way around and through the central tree between Adam and Eve. Though it has a serpentine body, its human head, face and tied back hair make it difficult to ascertain whether it is male or female.26 Its intense gaze up at Eve articulates a strong desire for her. For her part, Eve, on the left, looks down to contemplate a fruit in her upturned right hand. The action of the scene, however, hovers at her hips where her left-hand simultaneously touches and pushes away the naḥash. Her groin juts toward the creature, suggesting some desire on her part for it. Adam, by contrast, has his body positioned away from the two though he turns his head back to glower at Eve over his right shoulder. His left hand nearly fondles his exposed genitalia while his right-hand motions down toward where the naḥash penetrates the tree. Adam apparently feels in this situation both displaced and dissatisfied. Jealous could be another apt term. This could help explain the text’s terse treatment of Adam in Genesis 3:6. Despite its gender ambiguity and Eve’s apparent ambivalence, the naḥash has taken its presumptive place as Eve’s erotic and perhaps sexual complement.

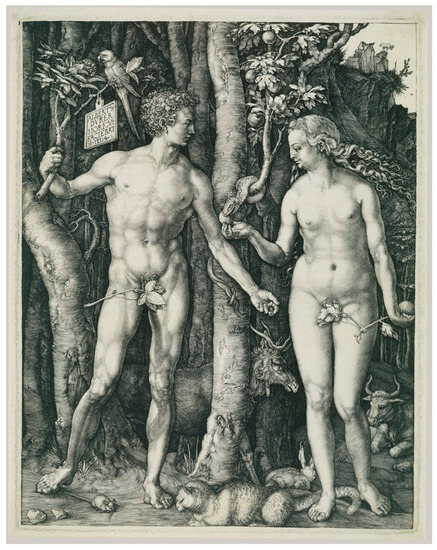

The crisscrossing of yearning is one theme in the followoing early 16th Century woodcut of by Albrecht Dürer (Figure 5). Muscular Adam stands with confidence on the left, grasping what is perhaps the Tree of Immortality in his right hand. He looks across at Eve, his left hand reaching down just shy of her hip and groin that is covered by an opportune branch. Eve stands on the right hiding a fruit in her left hand by her hip. She holds another fruit in her right hand, lifting it to feed the serpentine naḥash that is wound around the Tree of Moral Knowledge in between the humans. With a bemused expression, she looks down toward the naḥash, though her gaze may go beyond it to Adam’s groin that is similarly hidden by an opportune branch. These branches, it should be noted, are not the fig leaves attested to in Genesis 3:7. Could this scene thus depict the three just moments before the humans ate the fruit in Genesis 3:6? Perhaps. What attracts our attention here, though, is their attention.

Figure 5.

Albrecht Dürer, Adam and Eve (1504)28.

The intersecting lines of their sexual attention are clear, which invites the reader to revisit the role of eyesight in Genesis 3:5 and 3:7. Eve looks down toward the naḥash, who also looks down toward the fruit in its mouth, beyond which is Adam’s groin. A horizontal plane links the hidden fruit in Eve’s hand to her groin to Adam’s hand, across the naḥash’s tail, to Adam’s hidden groin. If Eve and the naḥash look upon Adam’s covered genitals with a similar desire, perhaps his reach is not for the fruit she hides but her hidden yet naked genitals.

While it is common not to cede much space in these pictures to nonhuman animals, Dürer does include a few. Most of them are sprinkled in the foreground and just behind the three main characters (mouse, rabbit, cat, bull, stag). Such creatures live in or near human settlements while the stag would perhaps be herded, as would the lone mountain goat in the distant top right. In Christian iconology, such animals represent more than their kind. According to religious art historian Diane Apostolos-Cappadona, a mouse signifies female sexuality, a rabbit fecundity, lust, and timidity, a cat passivity and lust, a bull brute force, strength, and fertility, a stag piety and religious devotion, and a white mountain goat represents “Jesus Christ in search of the church or of the all-seeing power of God”.29 Such associations heighten the already apparent sexual intrigues in the picture.

Perhaps the most famous depiction of the naḥash, Eve, and Adam is Michelangelo’s in the Sistine Chapel (Figure 6). On the left, Adam actively grabs at the tree with his left hand, and reaches toward a fruit with his right. Or perhaps he is stretching toward the therianthropic naḥash that holds onto the trunk of the tree. That creature sports a human face that appears female, hair wavy like Eve’s yet colored like Adam’s, a torso with breasts and arms, buttocks, and a two-trunked serpentine tail that winds down and off the trunk. The naḥash stretches its left hand out to Eve to pass her what may be a fruit. Eve lays perched below Adam atop her right elbow and twists her torso to look back and up at the naḥash while she lifts her muscular left arm to grasp the fruit.

Figure 6.

Michelangelo Sistine Chapel (1510)30.

So much of this picture is a departure from the biblical narrative. The gender of the naḥash, Adam’s agency, Eve’s position vis à vis Adam’s groin—to name just a few. The action of the scene opens many issues, too, that are not evident in the textual version. Contrary to Genesis 3:6, why is Adam so animated when it comes to the naḥash? Is he scrambling to get a fruit for himself, or does he point an accusing finger at the meddling naḥash? Eve’s location indicates a sexual connection with Adam and yet the familiarity of her expression suggests she welcomes the naḥash’s presence if not participation. The naḥash’s own expression hints at longing and urgency, though the object of its gaze is uncertain.

The right side of this picture shows Eve cowering and Adam grimacing as they are evicted from the Garden of Eden by a rose-robed flying angel foisting a sword at them (compare with Genesis 3:23–24). That the naḥash is the center of this bifurcated scene suggests that it serves as the fulcrum between Adam and Eve’s dynamic intimacy and their eventual desolation.

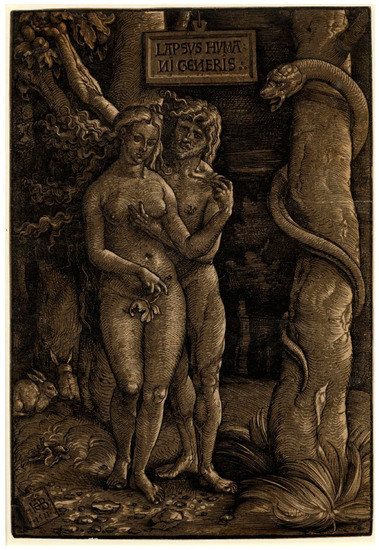

Nearly concurrent with Michelangelo’s work in Rome, Hans Baldung in Strasbourg entitled the woodcut below (Figure 7) as Fall of Humankind—to convey that its main subject is not the individuals but what their interactions produced. This portrayal highlights Eve and especially the serpentine naḥash on the right. Adam is partially covered by Eve, whose left breast he fondles with his left hand while his right reaches high to grasp fruit from the Tree of Moral Knowledge. Eve stands demurely even though she presses up against Adam’s chest and stomach. She holds a leaf in front of her groin in her right hand and a fruit in her upturned left. Both she and Adam gaze piercingly out of the frame as if to challenge the viewer’s gaze and invasion of their privacy. The naḥash does not care about such things: it stares menacingly at them, its mouth agape, perhaps in regard to Adam’s caress of Eve or to further encourage the humans to consume the fruit. Either way, the image inspires rethinking the proximity and dynamic between the three as portrayed in Genesis 2:25–3:6. Like his teacher, Dürer, in his aforementioned Adam and Eve (1504), Baldung includes rabbits behind the humans to reinforce the scene’s overt sexual tones.

Figure 7.

Hans Baldung, Lapsus Humani Generis (1511)31.

It is not the consummation of a relationship that Baldung considers to be the downfall of humanity, but desire and discontentedness. Adam, on the one hand (literally), grasps for the otherwise prohibited (fruit and its attendant knowledge) even as with the other hand he caresses Eve’s very present and pressing body. The naḥash’s unrequited yearning and Eve’s penetrating search for the viewer’s attention also demonstrate various forms of desiring what is not here and now. The story of Eden, Baldung apparently suggests, digs more into desire’s potency than disobedience, and this image encourages readers to revisit that story with this in mind.

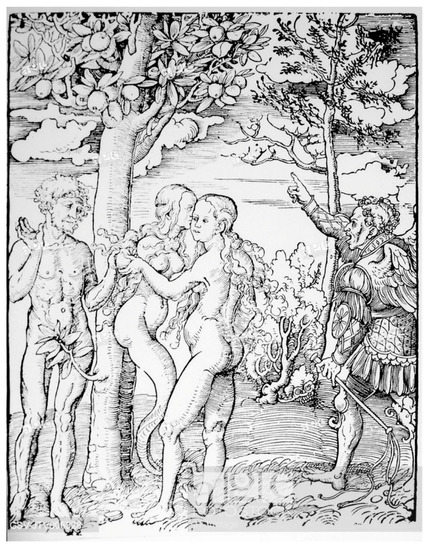

Over the course of his career in the 16th Century Germany, Lucas Cranach (the Elder) produced dozens of paintings of Adam and Eve, many of them with the naḥash in various forms. In the woodcut below (Figure 8) naked Eve stands at the frame’s center, flowing hair down her back, her belly protruding with what appears a mid-term pregnancy. She holds in her left hand a fruit that Adam, barely squeezed into the frame on the left side next to the Tree of Knowledge, grasps reluctantly with his left hand. His right hand is raised in a gesture of question or acquiescence. A branch conveniently ascends to hide his genitalia from view. Nestled between the Tree and Eve is a therianthropic naḥash. This creature has a female face, breasts, belly, and flowing hair much like Eve’s, and it stands atop a serpentine tail. It leans forward into Eve’s face kissing her right cheekbone as it looks past Eve toward an irate be-winged angel robed in garbs like those of royal servants, who gestures at the Tree with an expression of outrage that they were taking from it. The inclusion of the angel when Eve gives the fruit to Adam stitches together Genesis 3:6 and the appearance of the cherubim at the story’s end in Genesis 3:24.

Figure 8.

Lucas Cranach, Adam and Eve (1523)32.

Is the naḥash’s similarity to Eve an argument that there is no difference between it and Eve? Perhaps. On the other hand, Cranach may be opening the possibility that the naḥash existed physically, psychically, and emotionally between Eve and Adam and showered affection upon Eve, at least. This adds depth and tension to the already troubling curse of animosity it will now have toward Eve post-incident, as mentioned in Genesis 3:15. We will see momentarily that its attention and affection—desire, even—are not given exclusively to Eve.

In a mid-16th Century mural painting in the Church of St. Maria della Pace in Rome, Girolamo Siciolante da Sermoneta offers a provocative version of the “Original Sin” (Figure 9). Here, Eve takes center stage. Larger than all the others, she is luminous and turning. Her face turns toward Adam to her right, who is smaller and seated below her. She hands him a fruit with her left-hand that he grasps with his right. Adam, for his part, sits near the left frame with his hips and legs splayed and genitalia exposed, while his torso turns so he can better look up at Eve. Eve’s torso faces out toward the viewer as her left-hand gesture up to the right where, in the Tree of Knowledge, is the naḥash. This therianthropic creature has a dual serpentine tail wrapped and crisscrossed down the tree. It has a human head, male face, muscular back and buttocks, arms and hands, and male genitalia. It holds onto the tree with its right arm while reaching out toward Eve with its left.

Sermoneta follows other painters like Giuliano di Piero di Simone Bugiardini who insist on strong similarity between the naḥash and Eve.33 In Sermoneta’s setting, though, the similarity is between the naḥash and Adam. In addition to their comparable male musculature and genitalia, their hands (Adam’s right and the naḥash’s left) curve in a similar way and are aligned on the same plane as the fruit. They both look longingly at Eve as if hungry for her attention and affection. Furthermore, by inverting, tilting, and overlaying the naḥash’s face atop Adam’s, its visage is virtually the same as Adam’s. What does it mean that Adam and the naḥash are distinguishable only by their lower extremities? What might this mean about the ‘arum-ness the humans share with the naḥash in Genesis 2:25–3:1?

The striking similarity between Adam and the naḥash may explain Eve’s twisted pose and apparent ambivalence, a visual trope since the bronze doors at St. Michael’s Church in Hildesheim and especially on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. On the one side she looks toward Adam and shares fruit with him; theirs is a heady and risky connection. Yet, on the other side she turns her lower body toward the naḥash, as if to indicate a yearning for its embrace. Her outstretched arm and hand toward the naḥash coupled with her expression of genuine appeal toward Adam express a desire on her part to propose, perhaps, an expansive notion of relationship, one that transcends a dyad. In short, her ambivalence is no indifference; she is torn, pulled, and attracted in multiple directions, perhaps because she is the gravitational center for both their interests. This puts into starker relief God’s declaration in Genesis 3:16 that Eve’s urge post-incident will now be confined to her husband.

A 17th Century statue encased in a grotto in the Boboli Gardens in Florence by Michelangelo Naccherino offers a different vector of attraction (Figure 10). Here, of equal stature, Adam and Eve stand with forlorn expressions and garlands of leaves in front of their groins, suggesting that this moment comes after they have eaten the fruit, such as in Genesis 3:7. Adam’s right-hand rests gently atop his hip just shy of his genitals, while his left arm wraps around Eve’s head, his fingers fondling her hair. Eve rests her head on her crossed arms that lay on Adam’s left shoulder. Posed with an air of mutual reliance, they nonetheless appear with downcast eyes to be contemplating the immensity of their situation with some trepidation. Behind Adam’s heels rises the naḥash, a therianthropic creature presenting with a human head, female face and long hair, breasts, torso, arms and hands, and a serpentine tail. It looks up with a complex expression of desperation, yearning, dejection, and even hope. All this it directs at Adam.

Figure 10.

Michelangelo Naccherino (1616), Boboli Gardens35.

Naccherino’s naḥash appears fixated on Adam—a vector of attention altogether absent in the Biblical story. Even so, this attraction powerfully explains its motivation to get Eve into trouble.36 It wanted to be Adam’s ‘ezer kenegdo, his partner. If it could harm Eve or even get rid of her altogether, perhaps it could then receive Adam’s undivided attention and affection.

A century and a half later in France, the naḥash becomes even more aggressive in its lust for a human in Jean-Baptiste Marie Pierre’s “The Temptation of Eve” (Figure 11). This glistening, fully serpentine creature winds its way over and through Eve’s legs, over her left thigh, behind her and up over her right shoulder to whisper in her ear. Eve sits askew on blooming flowers, leaning upon her left hand with her right arm up in a shrugged gesture. Is that raised right hand to repel the naḥash’s advances or a reaction to being tickled by its breath upon her ear and nape? Her expression fluctuates between discomfort and curiosity. There is no revulsion or disgust, no fear or sadness, that complicate her wary yet playful smile and glazed gaze out at the viewer. Her face, half hidden in shade, flushes afresh. All this layers emotional color onto the otherwise unremarkable encounter of Genesis 3:1. For his part, such as it is in Genesis 3:6, Adam snoozes in the background behind the Tree of Knowledge.

Figure 11.

Jean-Baptiste Marie Pierre, The Temptation of Eve (1740–1760)37.

Pierre puts in luminous hues the possibility that desire transcends species. The naḥash’s unrestrained envelopment of Eve shows the slipperiness seduction can have upon its intended target. There is little doubt it yearns for Eve, bodily and more. The vector of desire here is not just one way, however. Though her torso leans away from the naḥash, Eve also tilts her head back toward its mouth, as if intrigued by what she hears. Perhaps the caressing she senses upon her inner thigh arouses a hunger unsatisfied by the distant, mostly hidden and fully unconscious Adam. With and because of the naḥash, Eve wrestles with desire itself.

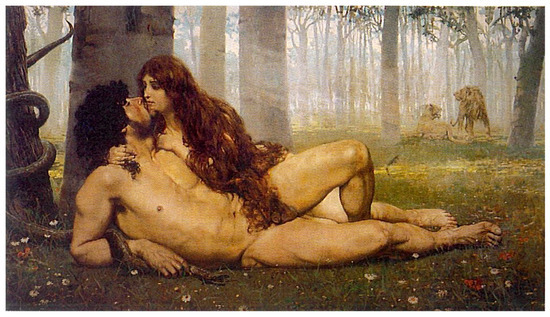

In the late 19th Century Spanish painter Salvador Viniegra suggests a completely different dynamic among the trio. In his “The First Kiss of Adam and Eve” (Figure 12), Adam lays in front of Eve, leaning back upon his right elbow. He tilts his head up, closes his eyes, and awaits the warmth of Eve’s kiss. Eve leans tightly upon Adam’s chest, her right arm wraps around his neck and her right hand holds his unkempt curly black hair. Her own reddish-brown hair cascades down her left shoulder to tickle but not hide his genitals as Adam’s left leg lifts. Eve gazes intently at Adam as she slowly moves in for that first, intense, kiss. So focused are the couple in their erotic embrace, they are undisturbed by the naḥash, a serpentine creature that winds multiple times around a tree off the frame’s left side. Its head slithers over Adam’s right forearm and through his loose fingers; its tail erect between the gap of trees. A lion and lioness cavort contentedly in the misty forest in the background. At first glance, Viniegra offers a generous, erotic rethinking of Genesis 2:25.

Figure 12.

Salvador Viniegra, The First Kiss of Adam and Eve (1891)38.

Though Adam is both central and passive, Eve is neither a diminutive dominatrix nor manipulating seductor. They appear as equals, both eager to connect physically. Their trusting and intensifying intimacy is but one part of the story, however. Insofar as Adam is not disturbed by the naḥash’s caresses and Eve is not threatened by its entanglements with him, the scene suggests multispecies sensuality and arousal. Viniegra thus challenges the dyadic relations advocated for in Genesis 2:24. Though such relations may be logical, they need not be limited to two; they can be more expansive and inclusive and could be no less intense. As in prides lions have harems of many lionesses, perhaps humans are naturally attracted to and by multiple forms of life and partners.39

6. Possibilities

Through the hands of these and other artists, the relationships between Eve, Adam and the naḥash appear as anything but dyadic or static. In some settings their relationships appear amicable whereas in others jealousy riddles them. Sometimes one is estranged or rejected while intimacy buds or eroticism throbs between the others. Often attraction and yearning transcend species. What these images share is the notion that desire pulses in Eden. More, desire is unconstrained, as suggested by that medieval prayerbook we saw at the beginning.

Irrespective if one views these images as provocations, heresies, laments, or, frankly, anything else, they invite further questions pertaining to their content, context, and pretext, that is, to the biblical text. Regarding content, such art offers powerful commentary about humanity’s natures (which are hardly monolithic) and connections with life beyond itself. Much may be at stake when depicting humans interacting with nonhuman creatures.

This is because, in part, human-made pictures (of animals) often convey narratives. According to scholar of religion and art John W. Dixon, a narrative goes beyond a story, which is a mere “recital of events as they develop in time”, and applies to “the deeper structures of our experience which emerge into story but also emerge into other aspects of experience as well” (Dixon 1978, p. 23). Whatever their nature, images serve as a location and mechanism for humans to communicate with each other and reflect over extended periods of time about these “deeper structures” of human existence and experience. Such images of the naḥash similarly indicate ongoing meditations on the deeper structures of relating and desire. They go beyond the mere story of Eden.

Furthermore, if texts tell a story or narrative, images show them. Both text and image use time, tension, and detail to convey their message, but a text unfolds diachronically with the reader encountering those features serially, one after another. By contrast, an image conveys a narrative or story largely synchronically or simultaneously. This leads Dixon to say, “art can define character and relation, intensify or quiet the rhythm of an act. Art can clarify an act beyond the possibilities of story because those things which must be set out in succession in the story can be shown, simultaneously, in a painting” (Dixon 1978, p. 29). Such simultaneity allows the viewer to engage details and tensions through shapes, colors and textures all at the same time, which allows the viewer to interpret them in and through their contemporaneous juxtapositions. This is how, according to Dixon, art clarifies acts “beyond the possibilities” of textual stories. In short, art’s explanatory and interpretive powers can not only articulate narratives as texts do but can interpret them in uniquely powerful ways. Furthermore, the few images surveyed above demonstrate such power through their exciting provocations. They help us think more deeply about how desire might function in a multiform existence.

Such images also encourage us to think about the contexts in which they emerged. Artists, like authors, exist within peculiar historical and terrestrial settings. Resources and power exogenously influence who thinks, draws, and sculpts what and how. How have contexts swayed (artistic) ideas about human natures, relations, and desires? In which ways do artists, like authors, resist or transcend extant dogmas and taboos? These kinds of questions may invite the scholarship of art history to converse even more with the study of biblical reception.

A pointed question for both fields to consider could revolve around how nonhumans and desire figure in such efforts. Biblical scholar Carol Newsom, for example, suggests that the very notion of “nakedness is one of the sharpest boundaries between the animal and the human. Animals make many things: shelters, tools, perhaps even weapons. But no animal makes clothes. Or, as Genesis might say, an animal is naked but not ashamed. Thus as the woman and the man confuse the boundary between themselves and the divine [by consuming a fruit that bequeaths to them divine knowledge], that action simultaneously establishes the definitive boundary between themselves and animals. If humans have become “like gods”, the consequence is that they are no longer like animals” (Newsom 2021, p. 123).

Yet, at least for the last one thousand years many artists resist depicting “the [or a] definitive boundary” between humans and the naḥash, much more between humans and “the animal”, that is, all non-human creatures, according to Gross. Indeed, some artists carefully include animals in their canvases to convey commonalities across species. How this is done, where and when—merit further investigation.

So, too, do the relationships between art and text also warrant further study. There is no doubt images enrich our understanding of earlier texts about which they offer visual meditations. At least in regard to images on biblical texts and themes, though, we should consider the ways they expand, challenge and even subvert that pre-text. Where, if anywhere, might the line between commentary and innovation lie? When is it best to use visual exegesis as a form of commentary, reception exegesis that historicizes visual commentary, or visual criticism that treats images as a true hermeneutic to critique the text? How might the presence, absence, and representation of nonhuman entities figure in this calculus?

It is not that the images selected above offer unique interpretations of this or that biblical verse, though many do this as well. Rather, they depict in startling ways complex and ongoing relations that invite us—the viewer—to revisit the biblical text (as readers) with new possibilities in mind. This, then, is the potency of visual criticism: it provides a dynamic engagement between text, image, self, and the deeper structures of human existence. When done and curated well, all (can) emerge altered, piqued, and fresh.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

The Bible opens with not just one but at least two creation stories, stories about the origins of the world and humanity’s location therein. The second story is the focus here. If the first creation story’s major focus is ontology, on how the cosmos and humanity came into being, the second story centers on the issue of relating.

This second creation story takes place in what is called the Garden of Eden, a bucolic idyll of aesthetically pleasing and nutritious plants, and two special trees: a tree of moral knowledge and a tree of life.40 God forms a human and places him there (twice) (Genesis 2:8 and Genesis 2:15). After commanding the human to be careful about what to eat lest he suffer mortal consequences, God articulates the central theme to this narrative: “It is not good for the human to be alone; I will make for him an ‘ezer kenegdo”.41 An ‘ezer kenegdo is often understood to be a ‘fitting helpmate’ or ‘companion’ or ‘partner.’ Whatever the term may be, it is to be in relationship with this human. The remainder of the text pivots to consider who or what is a fitting partner and what relating entails.

God’s first effort to attend to this divinely perceived problem (that is, lack of relationship) is the creation of nonhuman animals, specifically wild beasts and birds of the sky.42 God brings all these newly formed creatures to Adam to see if any would suffice for the role of being Adam’s partner. This reads like a profound (divine!) expression of an anti-speciesist worldview: God holds no preconceived notion that excludes Adam’s partner being from the domain of nonhuman animals. Indeed, God’s first impulse embraces the possibility that it could be a creature quite different from Adam. In short, relating or connecting in some meaningful way with an other matters more than the form of that other. Even though Adam names all the cattle, birds of the sky and wild beasts, no ‘ezer kenegdo was found among them.43 That no fitting partner emerged seems to be a second failure on God’s part.

Undeterred, God puts the human Adam to sleep, extracts a rib, fashions a new entity called woman, and presents this woman to Adam. After Adam describes her existence as derivative from him, as if describing a fact, a gloss interrupts the narrative both underscoring its unifying theme—relationships are at the center of creation—and adding this normative observation: “Thus a man leaves his father and his mother and clings to his wife and they become one flesh”.44 Both Adam and the interrupting gloss thus embrace a speciesist perspective: at least when it comes to mate selection, it is preferrable for a human to select a fellow human.

The story resumes as though that narrative break did not exist. It says the two humans were ‘arumim, typically translated as naked, and unashamed, and the “naḥash was the most ‘arum of all the wild beasts that God made”.45 We should pause for a moment. Millennia of commentary impress upon us to think that the naḥash as the most wily, conniving, shrewd creature of all the wild beasts.46 If this is what ‘arum means, as many English translations would have us believe, then it must also be a characteristic of the humans, as they are also ‘arum. Or, since the humans and the naḥash share in this quality (‘arum), it could very well be that the naḥash is naked just like them.47 Either way, the humans and the naḥash are more alike than the humans are to other creatures that Adam encountered yet found unsatisfactory to be his ‘ezer kenegdo.

So alike are they that this naḥash speaks with the woman. Unsurprised that this creature speaks and speaks a language she understands, the woman responds to its question about whether God really said, “you shall not eat of any tree in the garden” (Genesis 3:2). The woman clarifies that they are permitted to eat of the garden’s trees except for the tree in the middle of the garden, about which (she asserts) God said, “You shall not eat of it or touch it, lest you die” (Genesis 3:2–3). The naḥash responds that “You are not going to die, but God knows that as soon as you eat of it your eyes will be opened and you will be like divine beings who know [or, God, who knows] good and bad” (Genesis 3:4–5).

The rest of the story is rather famous: She observes the tree, thinks it looks good to eat, takes a piece of fruit, eats it, gives it to her husband, he eats, then their eyes are opened and they observe their nakedness, and continue on to sew fig leaves together and make loincloths for themselves.48 They then sense God rustling in the garden and hide. God calls out to the man where he is, to which the man replies that he was afraid because he was naked and so he hid. God asks who told him he was naked, and did he eat from the prohibited tree. The man blames the woman whom God put at his side. God asks the woman what she did. She replies that the naḥash duped (hisi’ani) her and she ate (Genesis 3:8–13).

God then speaks to the naḥash, which also warrants pause. This is the first and only non-human creature God speaks to in the Bible.49 This indicates that the naḥash, unlike all other non-human animals, shares with humanity sufficient moral worth to merit divine attention and direct verbal engagement. God says to the naḥash,

Because you did this, more cursed shall you be than all the cattle and all the wild beasts. On your belly shall you crawl, and dirt shall you eat all the days of your life. I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and hers. They shall strike at your head, and you shall strike at their heel (Genesis 3:14–15).

Since the context implies all this is a radical change for the naḥash, it must mean that prior to this incident it was not a cursed creature any more than others, it ambulated vertically, it ate things other than dirt, and most significantly, it shared an intimate and trusting relationship with the woman and her offspring. In brief, the naḥash was very much (like a) human (or should we say: the humans are very much like the naḥash?).50

The story plunges on. God then promises the woman that her childbirth will be painful, her urge will be toward her husband, and he shall rule over her (Genesis 3:16). Furthermore, to the man God says that since he did as his wife said and ate from the prohibited tree, the ground will be cursed, by the sweat of his brow he will have to extract his nourishment, and ultimately he will return to the ground “for from it you were taken, for dust you are, and to dust you shall return” (Genesis 3:17–19).

The man names his wife Eve, because she’s the mother of all the living, and God makes garments of skin for Adam and his wife, and clothes them (Genesis 3:20–21). God wonders aloud what might occur were the man, who now knows good and bad and is more “like one of us”, to also take from the tree of life and live forever (Genesis 3:22). God banishes him from the Garden of Eden (twice51, as if echoing his double placement into it), to till the soil from which he had been taken, and stationed cherubim with fiery rotating swords at the eastern side to guard the way to the tree of life (Genesis 3:23–24).

Since the text does not say whether Eve is also banished, or what happens to the naḥash, it appears that for the biblical narrator God is particularly uncomfortable with Adam remaining in Eden. The physical distance God imposes upon Adam inverts the psychical similarity they now share—knowing good and bad. God’s worry about Adam becoming immortal could go beyond the possibility that they would become even more alike and be closer to a fear that they would be indistinguishable. In God’s view, relationships can only exist in the “in between”—between different/distinct entities. Just as the woman had to be a separate(d) entity to be Adam’s ‘ezer kenegdo, Adam would need to remain distant and distinct for God to be Adam’s (and humanity’s) ‘ezer kenegdo. To its end, this creation story’s prime concern is relating, a concern that has animated human existence ever since.52

Being the unique creature that it is, the naḥash serves a critical role in this early meditation on relating. It exemplifies similarity and difference. Like God, it knows what will (not) happen when the humans eat from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Bad. Like Eve, it is created after Adam. Like Adam, it is made from earth and is responsible for the consequences it must endure (God says to both, “because you did X”, but does not say this to Eve). Like the humans and God, it speaks, is understood, and understands when spoken to. Like the humans, it is naked and/or cunning (‘arum). By sharing these and other features with Adam, Eve and God—and by not being exactly like them, the therianthropic naḥash is able to relate with each. Furthermore, as seen above, desire ripples across these relationships in perhaps surprising ways.

Notes

| 1 | Machzor Vitry (Horowitz edition), JTS MS 8972. Photo 0149025. https://cja.huji.ac.il/browser.php?mode=alone&id=3540 (accessed on 29 September 2022). |

| 2 | On viewing naked bodies during prayer, see Crane (2010). |

| 3 | See, for example, Paolo Berdini (1997) and Martin O’Kane (2007). |

| 4 | See discussion in O’Kane (2007, p. 34ff). |

| 5 | See, for example, Joyce and Lipton (2012); Edwards (2012); Lipton (1999). |

| 6 | See, for example, Crowther (2010); Flood (2011). |

| 7 | See, for example, Exum (2019). |

| 8 | Exum (2019, p. 12), sharpens the distinction between this approach from art history and reception history studies this way: “matters of concern…such as conventions, trends, and developments in the history of art, social and cultural influences that shaped an artist’s interpretation, and the way viewers in the artist’s time would have understood these paintings, are not relevant for the questions I want to raise about the text and its visual representations”. |

| 9 | Apostolos-Cappadona (2020, p. 178). Conrad Gessner published Historia Animalium in mid-16th Century Zurich—a massive encyclopedic work of what might be considered natural zoology, though the multivolume series does include fantastical and mythical creatures. In the eyes of the Catholic Church, Gessner’s Protestantism polluted the text, so it was officially banned and its doctrinal errors were cleaned and edited out. |

| 10 | Regarding animals, see Mishnah, Kilayim 1.6. Indeed, as testified by the very existence of this tractate of laws and subsequent expansions upon it, the rabbis consider it important to protect the integrity and supposed boundaries of (certain) kinds. |

| 11 | For more on this discussion, see essays in Wilson (1999). |

| 12 | Of course, the naḥash is not the only therianthropic creature in Jewish sources. See Kulik (2013) and Slifkin (2007) for others. |

| 13 | See Neis (2019) for the significance of this distinction in tractate Kilayim. Whereas Jewish legal texts like Kilayim declare distinctions, similarities, and membership in “kind” categories by fiat, the commentators surveyed below appear comfortable with considering the naḥash beyond such conceptual limitations. |

| 14 | For more on (dis)continuity between humans and nonhuman animals in Jewish sources, see Slifkin (2006); Wasserman (2017); Berkowitz (2018); Neis (2019). |

| 15 | Detailing the biblical story will help the reader who may not be familiar with the story better appreciate the images and vice versa. As Exum says, “Obviously the better one knows the biblical story the better equipped one is to analyse and to appreciate an artistic representation of it” (2019, p. 12). On the other hand, she continues, “our knowledge of the biblical story can inhibit our freedom in interpretation, causing us to read a work of art according to convention and predetermined notions of what it is ‘about.’ Thus there are advantages in taking a painting as our starting point for interrogating the biblical text” (2019, pp. 12–13). For those already familiar with the biblical story or for those who feel they are familiar with it, it may be prudent to continue on to the images themselves to see firsthand the divergent ways artists understand the story and comment upon its central themes in ways unconfined by “convention and predetermined notions.” |

| 16 | Gebara (1993), p. 178. Emphasis in the original. |

| 17 | Genesis 3:16. See also Song of Songs 7:11. |

| 18 | The Hebrew word teshukah can refer to desire that crosses species boundaries. See Genesis 4:7. |

| 19 | Bereshit Rabbah 20.5; BT Sotah 9b and Rashi, ad loc, s.v., naḥash hakdamoni; Avot d’Rabbi Natan, 1.10; Rashi, Genesis 3:15, v’eivah asit. |

| 20 | For Eve, see Bereshit Rabbah 18.6; BT Sotah 9b, and Rashi, ad loc, s.v., naḥash hakdamoni; Rashi, Genesis 3:1, s.v., v’hanaḥash hayah ’arum; Genesis 3:20, s.v., vaykra ha’adom; Siftei Chaḥamim, Genesis 3:1, s.v., mah ‘inyan ze l’can. For both Adam and Eve, see Bereshit Rabbah 85.2; Zohar, Bereshit 1:52a. Insofar as copulation can be one behavioral indication of desire, many textual sources contend that a great deal of sex was had in the Garden of Eden. Some sources hold that the naḥash engages in sex face to face like humans (Bereshit Rabbah 20.3; BT Bechorot 8a; Pesikta Zutarta (Lekach Tov) on Genesis 3:14), had learned about sex by watching Adam engage with Eve (Bereshit Rabbah 22.2), had sex with Eve (BT Yevamot 103b; BT Shabbat 145b-146a; BT Avodah Zarah 22b; Zohar, Bereshit, 1:36b, 37a, 52a, 54a, 122b) and with Adam (Hippolytus, Refutations of All Heresies, 5.21). For his part, Adam had sex with all creatures before doing so with Eve—all to determine his ’ezer kenegdo (BT Yevamot 63a; Rashi, Genesis 2:23, s.v., zot hapa’am). Eve had sex with an angel (Targum Jonathan on Genesis 4:1), with Sammael (who rode atop the naḥash) and then Adam (Pirkei d’Rabbi Eliezer, 21.2; Zohar, Bereshit 1:37a), and with the naḥash and then Adam (Zohar, Bereshit, 1:36b). Beyond references to this narrative, it was understood that a naḥash might desire a woman and have sex with her (4 Maccabees 18:7–8). The Talmud offers guidance for the situation when a woman is confronted by a naḥash indicating it wants to have sex with her (BT Shabbat 110a). Trans-specific sex before the Flood can be found in Bereshit Rabbah 28.8, and in commentary by Rashi, Ramban, Chizkuni and Mizrachi on Genesis 6:12. That humans engaged in such abundant antediluvian trans-specific sex, see BT Sanhedrin 108a; Midrash Tanḥuma, Noaḥ §12.3. |

| 21 | Hundreds of images of the Eve, Adam and the naḥash are readily available. Collections, like the blogpost by R. L. Cummings (2020), are wonderful but often driven by ideology (Cummings, for example, insists the naḥash is an instantiation of the devil and, by extension, evil). In his blogposts, Nilsen (2018a, 2018b, 2018c) offers art history commentary to the images he supplies, but only offers a thin analysis of them in light of the Biblical story. Lily Fisher’s Pinterest collection (https://www.pinterest.com/lilysonoma/art-adam-and-eve/, accessed on 29 September 2022) is devoid of organization and analysis. |

| 22 | Philosophers like Haraway (2003, 2008) and Willet (2014) and theologian Deane-Drummond (2019) offer exciting challenges to these conventional assumptions. |

| 23 | https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f2/20141024_HildesheimCathedral_Niedersachsen_BernwardsTuer_DSCN0138_PtrQs.jpg (accessed on 29 September 2022). |

| 24 | https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bernwardstür_(5).JPG (accessed on 29 September 2022). |

| 25 | https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Bernwardstür#/media/File:Bernwardstür_(7).JPG (accessed on 29 September 2022). |

| 26 | The idea that the naḥash had a humanoid face at all was perhaps first articulated by Peter Comestor in his Historia Scholastica (c1170). See discussion in Flood (2011, pp. 72–73). For Comestor, it was a female face “because like applauds like” (p. 22). For more on Comestor, see Karp (1978) and Flores (1981). See also Kelly (1971). |

| 27 | https://lanuovabq.it/it/adamo-ed-eva-linizio-della-storia-della-redenzione (accessed on 29 September 2022). |

| 28 | https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/336222 (accessed on 29 September 2022). |

| 29 | Apostolos-Cappadona (2020, p. 183). For the other animals, see pp. 180–88. |

| 30 | https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/21/Adam_and_Eve%2C_Sistine_Chapel.jpg (accessed on 29 September 2022). |

| 31 | https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=1424340&partId=1&images=true (accessed on 29 September 2022). |

| 32 | https://www.agefotostock.com/age/en/Stock-Images/Rights-Managed/GSV-jtv005328 (accessed on 29 September 2022). |

| 33 | See, for example, Burgiardini’s Adam and Eve (~1520) at https://library.artstor.org/#/asset/SS7731421_7731421_11815413;requestId=115324b5ef2a7f6e19794b2169552383 (accessed on 29 Setpember 2022). |

| 34 | |

| 35 | https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Boboli,_Grotta_di_Adamo_ed_Eva_02.JPG (accessed on 29 September 2022). |

| 36 | For other possible motivations, see note 50 below. |

| 37 | https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pierre,_Jean-Baptiste_Marie_-_The_Temptation_of_Eve.jpg (accessed on 29 September 2022). |

| 38 | https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:El_primer_beso_Salvador_Viniegra_y_Lasso_de_la_Vega_(1891).jpg (accessed on 29 September 2022). |

| 39 | See note 20 above for classic sources on trans-specific desire and sex. |

| 40 | While latter is situated in the garden’s center, the former’s location is unspecified (Genesis 2:9). All translations will be by this author, unless otherwise noted. |

| 41 | Genesis 2:18. Much can be wondered about God’s statement. Is this an expression of divine lack of foresight that some kind of partner is needed? Or does it convey the musings of an artist who “discovers” during the creative process that more needs to be done? Or does God admit failure to create a “good” situation? What does it mean that God projects onto the human that its isolation is not good (note that the human does not bemoan this fact)? |

| 42 | This second creation story does not use the term “kind” (minim) when describing animals, as does the first creation story at Genesis 1:21, 24–25. |

| 43 | Genesis 2:19–20. The idea that nonhuman animals can serve as meaningful companions or partners to humans is picked up in the parable Nathan uses to rebuke King David for getting Uriah killed so to get access to Bathsheba. See II Samuel 12:1–10. On Nathan’s view, thinking about transpecific partnership is morally instructive. In the Islamic tradition, God instructs Adam on what the names of the animals should be (Qur’an 2:30–34). For more on the complexity of naming animals, see Brock (2017). The epic of Gilgamesh offers another ancient meditation on the beauty, meaningfulness, and profundity of transpecific relating. Such notions transcend civilizations: Indigenous environmental scientist Jessica Hernandez (2022) shows that indigenous communities understand nonhuman animals and the environment more broadly to be relatives to humans, not resources available for exploitation. |

| 44 | Genesis 2:24. See Tosato (1990) for a fascinating study of this verse’s late Persian period insertion to promote anti-polygamist, matrimonial legislation then making the rounds. Though this verse was not, on Tosato’s reading, “an etiology concerning sexual drive or love” (p. 409), it nevertheless reinforces the narrative’s overarching themes of relating and (non-erotic) desire. |

| 45 | Genesis 2:29–3:1. If the biblical author wanted to connect a sense of shame to nakedness, the word ‘ervah would be more apt. That neither Adam nor Eve experience shame here in/through/because of their own or the other’s nakedness does not automatically mean they do or would once they become aware of their own (and the other’s) nakedness a few verses later. Indeed, the text only says their eyes were opened and they perceived their nakedness (Genesis 3:7). In fact, Genesis 2:29 is the only instance shame (from the root bosh) appears in the Torah. It only reappears, with gusto, among the 8th Century prophets. For more on this and rabbinic ambivalence about shame, see Crane (2011). Claims that shame is a central theme to this narrative thus stand on thin to nonexistent evidence. |

| 46 | Millennia after the biblical story was canonized, the Masoretes inserted a dagesh in the mem for the human’s ‘arum, so to visibly distinguish the otherwise identical Hebrew root of these two words (‘arumim and ‘arum). In this way they made a graphical difference where none had been before to explain or justify the increasingly conventional lexical interpretation that one instance of ‘arum meant naked and the other meant wily. See Cassuto (1944), vol. 1:143–144; Lerner (2007), pp. 90–91; Zevit (2013), pp. 163–65. |

| 47 | We should take another pause to acknowledge that though these two verses (2:29–3:1) span two chapters, this separation is another imposition onto the biblical text. Torah scrolls were and are to this day devoid of vowels, punctuation, chapter headings and verse numbers. All these were added later, much later. The idea of breaking the text into big chunks like chapters emerged only in the 13th Century and verse numbers appeared with the advent of the printing press a few centuries later. Hence, in the earliest versions of the text (still visible in extant sifrei torah) such demarcations between these two verses are not visible. Nor are there closed breaks (stuma) or open breaks (petucha) interrupting the visual flow of the handwritten Toraitic narrative from what we now know as Genesis 2:4b all the way to Genesis 3:15. Closed breaks occur after Genesis 3:15 and 16, an open one after 3:20, and a closed one after 3:24. Such lexicographic evidence suggests that at least for the earliest scribes, this narrative begins at 2:4b and runs continuously until Genesis 3:15. |

| 48 | Genesis 3:6–7. In Chapter 5 of her recent book, biblical scholar Carol A. Newsom (2021) situates these verses and Genesis 2–3 generally among the “speculative intellectual literature” of the early 6th Century BCE wherein will, desire, and knowledge explain “the distinctive human cognitive capacity to make deliberative judgments” (p. 117). Specifically, with the shift to Eve’s response to the naḥash, “what the narrator’s words describe is simply the moment of desire. Furthermore, desire is not the same as discriminating judgment”, as the verbs connect appetite and attraction (p. 122). “The desire for wisdom”, Newsom contends, “is not truly a rational choice but is folded into a more enveloping experience of desire that operates on a prerational level….Desire [as noted above] is thus a quality intrinsic to our prehuman state and capable of mobilizing the will over against a prohibition” (p. 122). |

| 49 | God speaks through Balaam’s donkey but does not address her directly (Numbers 22:28). Though God commands the fish that spews Jonah out, there is no textual evidence of the content of God’s command (Jonah 2:10). |

| 50 | Zevit (2013) offers some speculative explanations for the naḥash’s actions. Perhaps it was “attempting to take revenge against the woman responsible for changing Adam’s relationship with animals” (p. 166); or maybe it “was a plot to supplant humans from their position in the divinely established hierarchy of authority on earth” (p. 201). Another possibility—tweaking Zevit’s first with more specificity—is that it desired to be Adam’s ‘ezer kenegdo and thus sought to get Eve in trouble for usurping (or, being given) that position. |

| 51 | One time (3:24) is with the verb va’ygaresh, which also means to divorce. The other time (va’yishlaḥehu, in 3:23) also connotes being sent out free. |

| 52 | As noted above, Gilgamesh is another ancient religious source that focuses on relating as a central theme. More recently and in more secular tones, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is also a painful meditation on this topic. In Franz Kafka’s short story, “A Report for an Academy”, the German-speaking Hominidae hero, Red Peter, bemoans his vitiated relations with duped trained animals and yearns for more meaningful and stimulating relations even if that means relating with human beings. Contemporary social media and dating sites are but the latest instantiation of humanity’s hungry search for (meaningful, stimulating) relationships. Curiously, Gilgamesh, Frankenstein, and Kafka’s story are like the Bible: they situate therianthropic entities at the core of their meditations on these topics. |

References

- Apostolos-Cappadona, Diane. 2020. A Guide to Christian Art. London: T&T Clark. [Google Scholar]

- Berdini, Paolo. 1997. The Religious Art of Jacopo Bassano: Painting as Visual Exegesis. Cambridge: Cambrdige University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz, Beth A. 2018. Animals and Animality in the Babylonian Talmud. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, Brian. 2017. ’To See What He Would Name Them…’: Naming and Domination in a Fallen World. In Fallen Animals: Art, Religion, Literature. Edited by Hadromi-Allouche Zohar. London: Lexington Books, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Cassuto, Umberto. 1944. A Commentary on the Book of Genesis. Translated by Isarel Abrahams. Jerusalem: The Magnes Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, Jonathan K. 2010. Judaic Perspectives on Pornography. Theology & Sexuality 16: 127–42. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, Jonathan K. 2011. Shameful Ambivalences: Dimensions of Rabbinic Shame. AJS Review 35: 61–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowther, Kathleen M. 2010. Adam and Eve in the Protestant Reformation. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, R. L. 2020. Serpents and Sex: “The Temptation of Eve” in Art Through the Ages. Andaman Inspirations. September 6. Available online: https://andamaninspirations.com/2020/09/06/serpents-seduction-and-sin-the-fall-in-art-through-the-ages/ (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Deane-Drummond, Celia. 2019. Theological Ethics through a Multispecies Lens: The Evolution of Wisdom. New York: Oxford University Press, vol. I. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, John W. 1978. Art and the Theological Imagination. New York: The Seabury Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Katie B. 2012. Admen and Eve: The Bible in Contemporary Advertising. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press. [Google Scholar]

- Exum, J. Cheryl. 2019. Art as Biblical Commentary: Visual Criticism from Hagar the Wife of Abraham to Mary the Mother of Jesus. London: T & T Clark. [Google Scholar]

- Flood, John. 2011. Representations of Eve in Antiquity and the English Middle Ages. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, Nona C. 1981. “Virgineum Vultum Habens”: The Woman-Headed Serpent in Art and Literature from 1300 to 1700. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Illinois-Champaign, Champaign, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Gebara, Ivonne. 1993. The Face of Transcendence as a Challenge to the Reading of the Bible in Latin America. In Searching the Scriptures, Volume One: A Feminist Introduction. Edited by Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza. New York: Crossroad, pp. 172–86. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, Alison. 2016. Reception of the Old Testament. In The Hebrew Bible: A Critical Companion. Edited by Barton John. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 405–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, Aaron. 2015. The Question of the Animal and Religion: Theoretical Stakes, Practical Implications. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, Donna. 2003. The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, Donna. 2008. When Species Meet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, Jessica. 2022. Fresh Banana Leaves: Healing Indigenous Landscapes Through Indigenous Science. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce, Paul M., and Diana Lipton. 2012. Lamentations Through the Centuries. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Karp, Sandra Rae. 1978. Peter Comestor’s ‘Historia Scholastica’: A Study in the Development of Literal Scriptural Exegesis. Ph.D. Dissertation, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, Henry Ansgar. 1971. The Metamorphoses of the Eden Serpent During the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Viator 2: 301–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulik, Alexander. 2013. How the Devil Got His Hooves and Horns: The Origin of the Motif and the Implied Demonology of 3 Baruch. Numen 60: 195–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, Anne Lapidus. 2007. Eternally Eve: Images of Eve in the Hebrew Bible, Midrash, and Modern Jewish Poetry. Waltham: Brandeis University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levinas, Emmanuel. 1969. Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority. Translated by Alphonso Lingis. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lipton, Diana. 1999. Images of Intolerance: The Representation of Jews and Judaism in the Bible moralisée. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Neis, Rachel Rafael. 2019. ’All That is in the Settlement’: Humans, Likeness, and Species in the Rabbinic Bestiary. The Journal of Jewish Ethics 5: 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsom, Carol A. 2021. The Spirit Within Me: Self and Agency in Ancient Israel and Second Temple Judaism. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen, Richard. 2018. Lady and the Snake, Part I. January 17. Available online: https://richardnilsen.com/2018/01/17/eve-and-the-snake-part-1/ (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Nilsen, Richard. 2018. The Lady and the Snake Part 2. January 22. Available online: https://richardnilsen.com/2018/01/22/the-lady-and-the-snake-part-2/ (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- Nilsen, Richard. 2018. Lady and the Snakes, Part 3. January 24. Available online: https://richardnilsen.com/2018/01/24/lady-and-the-snakes-part-3/ (accessed on 29 September 2022).

- O’Kane, Martin. 2007. Painting the Text: The Artist as Biblical Interpreter. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parkington, John. 2003. Eland and Therianthropes in Southern African Rock Art: When Is a Person an Animal? The African Archeological Review 20: 135–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, Vernon. 2017. New Testament Texts, Visual Material Culture, and Early Christian Art. In The Art of Visual Exegesis: Rhetoric, Texts, Images. Edited by Vernon K. Robbins, Walter S. Melion and Roy R. Jeal. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, pp. 13–54. [Google Scholar]

- Slifkin, Natan. 2006. Man & Beast: Our Relationships with Animals in Jewish Law and Thought. Brooklyn: Yashar Books. [Google Scholar]

- Slifkin, Natan. 2007. Sacred Monsters: Mysterious and Mythical Creatures of Scripture, Talmud and Midrash. Brooklyn: Yashar Books. [Google Scholar]

- Tosato, Angelo. 1990. On Genesis 2:24. The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 52: 389–409. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman, Mira. 2017. Jews, Gentiles, and Other Animals: The Talmud After the Humanities. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Willet, Cynthia. 2014. Interspecies Ethics. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Robert. 1999. Species: New Interdisciplinary Essays. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zevit, Ziony. 2013. What Really Happened in the Garden of Eden? New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).