Alternate Narratives for the Tamil Yoginis: Reconsidering the ‘Kanchi Yoginis’ Past, Present, and Future

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. What Are Yoginis

The companions of the gods were alarmed by the vibrating resonance of their anklet bells as the Yoginis danced the distance between the sky and the earth. Their dark loose tresses splaying out across the daytime sky, darkened it, and their terrible yet glowing skull crowns stood out among the black tresses like stars at night.9

3. The Yogini Temple in Tamil Nadu and Its Deities

4. Siting the Yogini Temple

5. Building and Using the Temple

As abruptly as darkness descends at nightfall, even so, without warning did the Mahayoginis appear out of the sky, the earth, the depths of the nether regions, and the four corners of space … In their hands they held staffs topped with skulls and decorated with myriads of little bells which jingled furiously with the speed of their flight … Sparks issuing from the third eye on their foreheads were fanned into flames by the gasping of the helpless serpents ruthlessly enmeshed in the tangled masses of their hair; and these flames leapt forth so high as to singe the banners of the Sun’s aerial chariot. The ornamented designs on their cheeks were painted with blood which was being lapped up by the many snakes adorning their ears. Hovering over gruesome human skulls decorating their heads were vast numbers of giant vultures who obstructed the rays of the Sun. Tripping over one another in their haste, the Yoginis glowered repulsively and unleashed a host of tremendous and terrifying howls. Startled by the uproar, the Moon’s deer bolted off, trailing behind it scrambling constellations of stars entrusted with its care …29

6. Scattering the Temple

7. The Tamil Yoginis in the Twentieth Century

8. A Kanchi Yogini

9. Reuniting the Temple?

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | This article builds upon previous scholarship by authors including Vidya Dehejia (1986, 2021), James Harle (2000, 2008), Padma Kaimal (2012, 2013), Shaman Hatley (2012, 2013, 2014, 2019), Charlotte Schmid (2013), Debra Diamond (2013), and others. Our research has been generously supported by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art, the Detroit Institute of Arts, the Lilly Endowment, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and Colgate University. We are grateful for in-depth conversations with colleagues who participated in symposia and workshops held at the Annual Conference on South Asia (Madison, October 2019), the National Museum of Asian Art (online, May 2020), Colgate University (online, October 2020), and the Detroit Institute of Arts (online, June 2022), and to colleagues participating in ongoing conversations on this topic. For the purposes of this article we use conventional spellings for the names of places (Kanchipuram rather than Kāñcīpuram), deities (Shiva rather than Śiva), and dynasties (Chola rather than Cōḻa). For the names of temples and texts, we follow the Tamil Lexicon (University of Madras) or standard Sanskrit (Monier-Williams) systems of transliteration. |

| 2 | We will say more about the dating of these sculptures below. Most scholars who have published the group assign them a date within the tenth century. Kaimal (2012) dates them between 900 and 970 C.E. (p. 27), though she suggests the possibility of a late ninth-century date (p. 2). Dehejia (2021, p. 281) dates them to the early tenth century, a revision of her previous assessment that they belong to the second half of the tenth century (Dehejia 1986, p. 183). |

| 3 | Unpublished documents in the Jouveau-Dubreuil archives at the Musée Guimet (Paris) reveal that Jouveau-Dubreuil and Tangavelou found the yogini sculptures between August 1925 and May 1926—somewhat earlier than previously thought. Further, an undated report from Tangavelou himself, kept in a file of correspondence from 1927, shows his full name and the way he spelled it, at least while he was working with the French (Tangavelou, n.d.). In previous scholarship, he has been known as M. (Monsieur) Thangavelu (Harle 2000; Kaimal 2012). However, he signs his name “N. Tangavelou” and his letterhead presents him as “N. Tangavelou Pillai.” We are grateful to Cristina Cramerotti, Amina Okada, and Vincent Lefèvre for access to these archives in May 2022. |

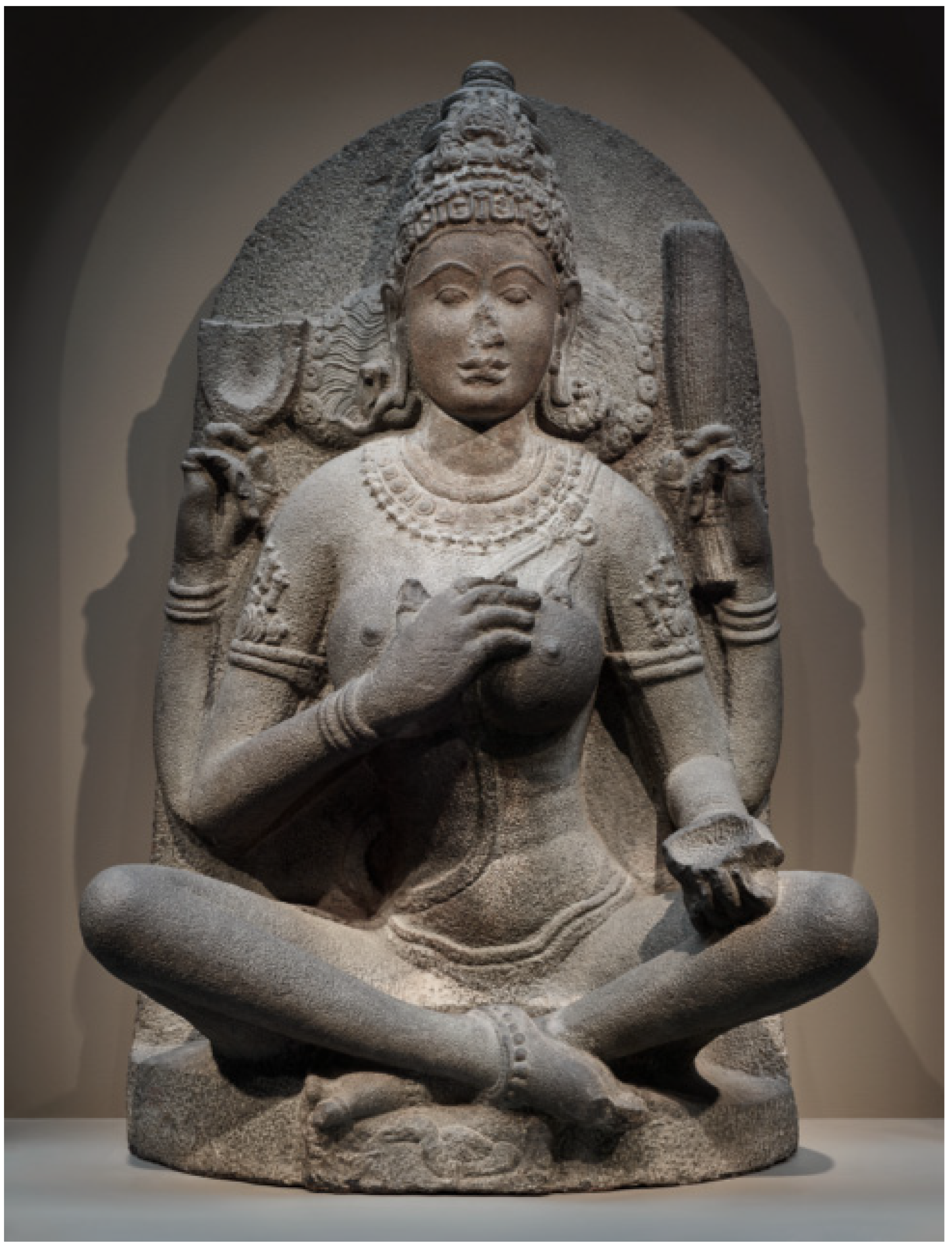

| 4 | Padma Kaimal has traced the twentieth-century travels of these yoginis and their companions, exploring with nuance how their story demonstrates the relationship between collecting and scattering (Kaimal 2012; see also Kaimal in this volume). |

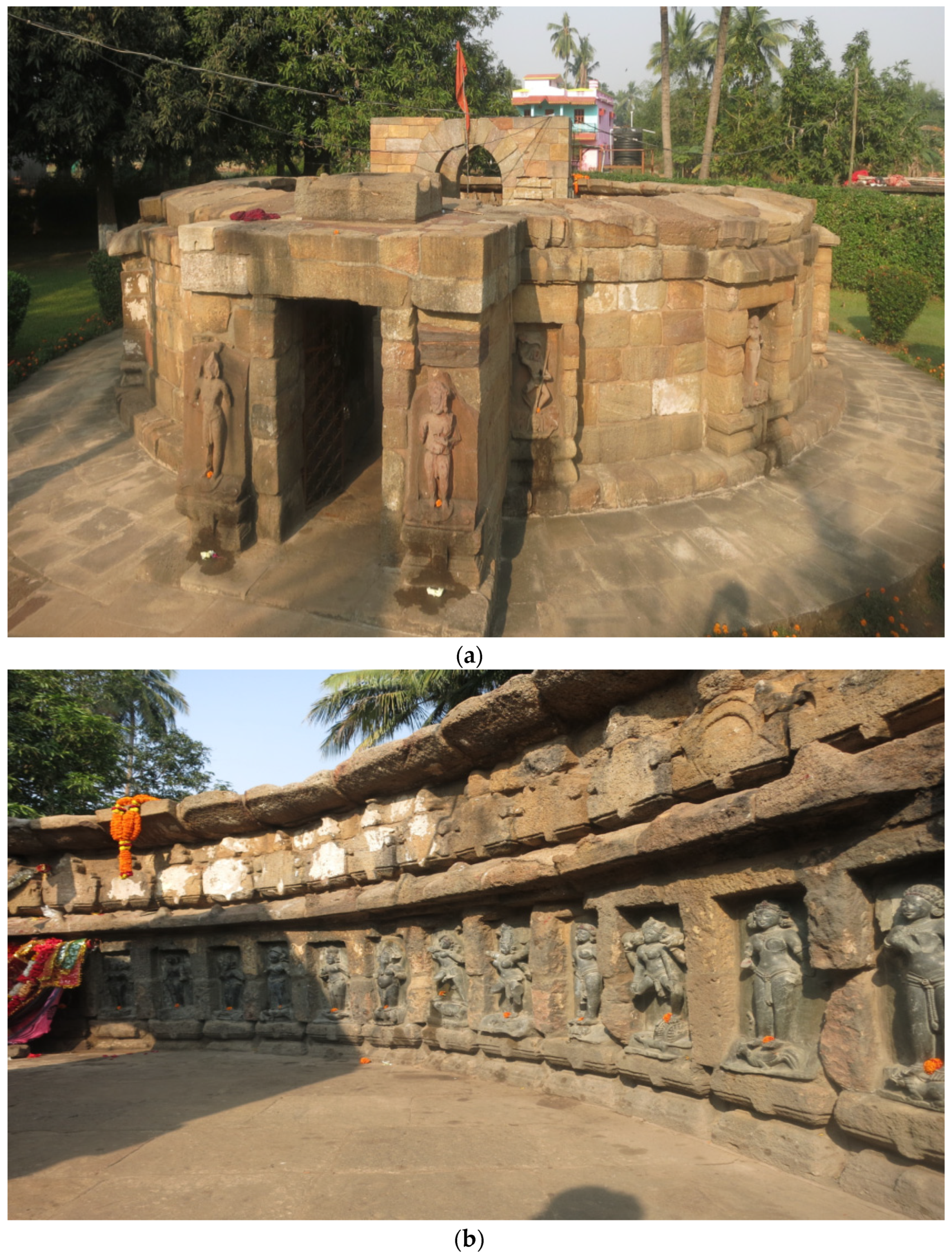

| 5 | Among the museum collections with sculptures from the set, the Musée Guimet (Paris) is the sole institution to house more than one. Its three yoginis are displayed together, less isolated than their dispersed companions. Kaimal charts the movement of the yoginis and related sculptures between 1926 and 2007 (Kaimal 2012, table 2, pp. 8–10). She includes nineteen sculptures in the set, five of which we omit from our count of fourteen in museum collections. Two sculptures (a lower fragment from a yogini and a headless matrika) are not presently located. Two door guardians have been shown to have come from another site, Dadapuram (Schmid 2013, p. 139). Lastly, we believe the Shanmuga sculpture in Kaimal’s list came from another temple (see n. 18 below). Among the fourteen sculptures now in museum collections, we include eleven yoginis (one of which may be comprised of the head of one sculpture and the body of another; see nn. 13 and 34 below), one Shiva-Vinadhara, and two matrikas. While we question the inclusion of the matrikas in the yoginis’ original temple (see below), these sculptures undoubtedly came to be associated with the yoginis at some point in time. |

| 6 | In previous scholarship, the group has frequently been called the “Kanchi yoginis” (Harle 2000, 2008; Kaimal 2012). The term “Tamil yoginis” as a geographical designation grew from a conversation with Debra Diamond and colleagues during the Annual Conference on South Asia in Madison, WI in 2019. It is not our intention to make a connection to modern Tamil nationalist politics. |

| 7 | On the Tamil yoginis’ hair and cultural meanings around female hairstyles in South Asia, see Kaimal (2012, pp. 93–94). |

| 8 | Kaimal and Dehejia have differing interpretations of the winnower, but both agree it is connected with acts of cleaning. Kaimal draws attention to the connection brooms and sweeping have to domestic work and to the labor of lower classes; she also highlights the dual nature of the broom, which is “useful for protecting creatures from dirt and illness, and for killing creatures that could import those threats” (Kaimal 2012, p. 91). Dehejia (2021, p. 280 and n. 9 p. 315) identifies the broom and dustpan as implements used to clean a temple, which “speak to [this yogini’s] elevated status, her authority, and her sanctity” (p. 280). |

| 9 | Translation by Vidya Dehejia, Mrs. Manikuntala Bhowmik, and Tyler Richard (Dehejia 2021, p. 279). We return to discussion of this text and its author below. |

| 10 | |

| 11 | |

| 12 | Among the Tamil yoginis, sizes range from approximately 100 to 134 cm in height (Kaimal 2012, table 6, pp. 21–23). |

| 13 | The twelfth, which consists of the damaged lower portion of a yogini sculpture, is attested in a photograph from Jouveau-Dubreuil, now in the Musée Guimet Photothèque (Kaimal 2012, pp. 17–18 and fig. 19, p. 43). Kaimal now counts these as thirteen because one of the yoginis at the Musée Guimet (MG 18508) appears to be composed of the head of one figure and the body of another (Kaimal, personal communication 12 April 2022). |

| 14 | |

| 15 | Kaimal wonders if the earlier matrikas were part of the original yogini temple at Bheraghat, “the product of a salvage operation” that “made the enormous project of accumulating eighty-one sculptures a bit easier” for those who built the temple (Kaimal 2012, p. 116). Dehejia attributes their place within the temple to a later time period (Dehejia 1986, p. 127). Masteller, who illustrates all the Bheraghat matrikas as well as discussing their relationship to the yoginis, also concludes that the eighty-one niches of the temple originally all contained yoginis (Masteller 2017, pp. 229–234 and figs. 4.36–4.40). |

| 16 | Many temples in South Asia have a life cycle of coming into and out of regular worship (Stein 2021, p. 268). |

| 17 | |

| 18 | Kaimal argues that the central shrine in the Tamil yogini temple was occupied by a Shanmuga (also called Subrahmanya, Skanda, or Karttikeya) now at the Government Museum in Chennai (acc. no. 71-5/37; Kaimal 2012, pp. 15–16, 19–20, 83–85). Although this sculpture shares certain stylistic features with the Tamil yoginis, we think the central shrine (if indeed there was one) was more likely occupied by a form of Shiva. In no other known instance does Shanmuga feature so prominently among a group of yoginis, whereas Shiva’s prominence is attested in multiple texts and temples (see Hatley 2014; Dehejia 1986). The Shanmuga sculpture is one of many in the Chennai Government Museum identified as coming from Kaveripakkam, and we suspect he once belonged to a different temple. Schmid also questions this Shanmuga’s place in the yogini temple (Schmid 2013, pp. 137–38, 149). |

| 19 | Kaimal provides a helpful table listing the sculptures she identifies as part of the Tamil yogini group in descending order of their likely original height (Kaimal 2012, pp. 21–23; chp. 1, table 6). The largest known yogini from the set, which Kaimal lists as 133.25 cm in height, is now at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (acc. no. 44-27). The Shiva-Vinadhara is next on the list, followed by the yogini at the National Museum of Asian Art, with a height of 116 cm. |

| 20 | The exterior of the yogini temple at Mitauli (eleventh century), some 35 km north of Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh, is articulated with moldings, niches, and figures similar to those of other temples in the region (see Dehejia 1986, pp. 121–24). Other extant yogini temples have starker exteriors (see Dehejia 1986, passim.). |

| 21 | For discussions of the transfer of knowledge through mobility of artists, see the articles in (Chanchani and Sears 2015). |

| 22 | In her careful consideration of the yoginis’ dating, Kaimal drew attention to the same late ninth-century comparisons that we have cited, but she ultimately argued that the yoginis’ more pronounced projection into the space surrounding them is more of a tenth-century trend in northern Tamil Nadu, and she dated them to ca. 900–970 (Kaimal 2012, pp. 20–26). Dehejia has recently revisited the Tamil yoginis in her 2021 study of Chola bronzes. Looking to different stylistic parallels from the Kaveri delta region, she concludes that the yoginis date to the first quarter of the tenth century (Dehejia 2021, pp. 277–81), revising her previous dating of the sculptures to the second half of the tenth century (Dehejia 1986, pp. 182–3). |

| 23 | A bund is a raised mound that separates a reservoir from surrounding rice fields on one side. The outflow of water from the reservoir is controlled by means of a sluice that allows water to pass through the bund. |

| 24 | NMAA Conservation Scientist Janet Douglas conducted petrographic analysis on the museum’s yogini to determine that the type of stone is metagabbro (alternately known as basic granulite among geologists). Department of Conservation and Scientific Research Object Records, LRN 4268, 22 June 2012, National Museum of Asian Art. Dr. Sarah Brownlee, Associate Professor of Geology at Wayne State University, Detroit, analyzed a thin section of stone from the DIA yogini in 2015. She identified the stone as pyroxene gabbro, a variety of metagabbro. Documentation in curatorial object file at Detroit Institute of Arts, Department of Arts of Asia and the Islamic World, acc. no. 57.88. |

| 25 | Although inscriptions from parts of northern Tamil Nadu bear regnal dates of Krishna III up to the end of his reign (Swaminathan 2012, no. 10, p. 395; see also nos. 5–9, pp. 390–95), the latest he is attested at his Tamil capital, Melpadi, is ca. 960 (Sharma 1997, p. 106; Deoras 1957, p. 136). His actual presence in Tamil Nadu is likely more relevant in a consideration of possible patronage. |

| 26 | Kaimal leaves the identity of the temples patron(s) open-ended, questioning whether members of royalty were necessarily involved (Kaimal 2012, pp. 26–27). There is a large body of ongoing scholarship continually nuancing understandings of patronage in South Asia broadly, including southern India more specifically. See, for example, Lee (2012), Kasdorf (2013), and Francis and Schmid (2016). |

| 27 | See also Hatley 2014 for translated passages from both ritual and literary texts in support of these conclusions. Imma Ramos cites additional passages in her discussion of yogini temples and the Tamil yoginis (Ramos 2020, pp. 54–60). |

| 28 | For a summary of the Yaśastilaka and its narrative threads involving yoginis, see Hatley 2014, pp. 211–12. K. K. Handiqui historically situates the text and its author in chapter 1 of his extended study of the Yaśastilaka (Handiqui [1968] 2011, pp. 1–21). Somadeva states in his colophon that the text was completed in Śaka 881 (959 C.E.) while Krishna III was in residence at Melpāṭi (Melpadi), but elsewhere he indicates that he composed the text at a place called Gaṅgadhārā (Handiqui [1968] 2011, pp. 2–3). While Handiqui argues that Somadeva probably had no royal patron (Handiqui [1968] 2011, pp. 5–6), Dehejia suggests that Krishna III himself was the author’s patron (Dehejia 2021, p. 277). |

| 29 | Translation by Vidya Dehejia, Mrs. Manikuntala Bhowmik, and Tyler Richard (Dehejia 2021, pp. 277–79). |

| 30 | Previous discussions of the yoginis’ removal from their findspot and shipment to C. T. Loo have been based on correspondence between Jouveau-Dubreuil and Loo, preserved in the C. T. Loo archives, and on photographs from the Musée Guimet Photothèque (Harle 2000; Kaimal 2012). |

| 31 | This undated report is filed between letters dating to 27 January 1926 and 17 February 1926, and it appears to be referenced in the latter (a note from Jouveau-Dubreuil to the “Ami”). Although not attributed to a specific author, most of it seems to be written in Jouveau-Dubreuil’s voice. However, the letter of 17 February 1926 references an enclosed report that Jouveau-Dubreuil requested from his chief agent (i.e., Tangavelou). Perhaps Jouveau-Dubreuil based the “Report on Hindu Antiquities” on another document from Tangavelou. At the time of this writing, we are only beginning to analyze this newly available material. |

| 32 | Previous publications have referred to him as M. (Monsieur) Thangavelu (Harle 2000; Kaimal 2012). |

| 33 | This is a brief synopsis of Tangavelou’s account of his acquisition of the sculptures. We do not have space within the scope of this essay to present his entire report or to fully consider its implications. We plan to present a more complete discussion, together with a translation, in a future publication. |

| 34 | The composite yogini, second from the left in Figure 15, is now at the Musée Guimet (acc. no. MG18508). If this sculpture was indeed part of the shrine, then the head and body were paired together before the sculpture entered the art market. Conservation and scientific research may be able to reveal more of this sculpture’s history—today it has repairs that are not seen in the photograph. |

| 35 | We plan to discuss these letters more fully in a future publication. |

| 36 | Kaimal notes that certain details pertaining to correspondence between Jouveau-Dubreuil and Loo, recorded in Harle’s handwritten notes, were omitted from Harle’s (2000) publication (Kaimal 2012, pp. 133–37, 242–43). One significant omission is the date of Jouveau-Dubreuil’s 29 September 1926 letter to Loo, the text of which appears in Harle’s publication directly beneath a letter from Loo to Jouveau-Dubreuil, dated 27 October 1926 (Harle 2000, p. 294; Kaimal 2012, p. 137 and n. 20, p. 243). |

| 37 | Letter from C. T. Loo to Benjamin March, 12 February 1929, in Detroit Institute of Arts Archives, *ASI 3-11. |

| 38 | Letter from Marion W. Riepe, a representative of C. T. Loo’s New York gallery, to Benjamin March, March 24, 1933, in Detroit Institute of Arts Archives, *ASI 3-12. A handwritten note on this letter reads “shipped March 29.” |

| 39 | Email correspondence from Michele Valentine to Katherine Kasdorf, 26 February 2021. |

| 40 | The following summary of the NMAA yogini’s twentieth-century travels is from Kaimal (2012, p. 164). |

| 41 | The yogini now in Chennai has long been established as part of the group (see Dehejia 1986, p. 181; Kaimal 2012, pp. 18–19 and n. 32, p. 222). |

| 42 | The sculpture’s accession number is 71/37. Kaimal confirmed with then-associate director of the museum, Mr. K. Lakshminarayanan, that museum records state that the sculpture entered the collection at that time, from the Kanchipuram district collector (Kaimal 2012, pp. 139–40 and nn. 28 and 30, p. 222). We have not had the opportunity to consult the museum’s records; perhaps they will reveal further details about this sculpture’s provenance. |

| 43 | Kaimal suggests that this yogini may be the sculpture described as “one headless statue” in the Jouveau-Dubreuil–Loo correspondence (Kaimal 2012, p. 19), but this description could instead refer to the Museum Rietberg’s yogini, a headless torso. If the sculpture was not sent to Loo, there would be no reason for Jouveau-Dubreuil to include it in the inventory of his shipment. (Kaimal makes a similar point about the absence of the Chennai yogini from Jouveau-Dubreuil’s photographs, pointing out that he would have had no reason to send Loo photographs of a sculpture not included in the shipment; Kaimal 2012, p. 18). |

| 44 | We are grateful to Ingrid Lao for discussing these ideas with us, and for her insight that our proposed arrangement of the sculptures resists imperialist modes of display. |

| 45 | For further discussion of community-centered practices contributing to this project, see Jean and Anila (2019). |

| 46 | See n. 1 above for a list of workshops completed through June 2022. In April–May 2022, the DIA distributed an online survey, aimed at broad audiences in Metro Detroit as well as South Asian and Hindu community members, to gauge initial responses to the exhibition project. In June 2022, DIA staff conducted four online focus group discussions (lasting about 1.5 hours each) to obtain more in-depth feedback from general audiences, individuals from local South Asian and Hindu communities, and yoga instructors. A more detailed account of these specific conversations is outside the scope of this article, but see Anila (2017b) for further discussion of community engagement strategies at the DIA. |

References

Primary Sources

Jouveau-Dubreuil, Gabriel to C. T. Loo. 1926. Folder for Correspondence from 1926, Jouveau-Dubreuil Archives, Musée National des Arts Asiatiques–Guimet, Paris.Loo, C. T. to Benjamin March. 1929. Box *ASI-3, Folder 11, Detroit Institute of Arts Archives.“Rapport sur les Antiquités hindoues” n.d. Folder for Correspondence from 1926, Jouveau-Dubreuil Archives, Musée National des Arts Asiatiques–Guimet, Paris.Riepe, Marion to Benjamin March, 24 March 1933, Box *ASI-3, Folder 12, Detroit Institute of Arts Archives.Tangavelou, N. to C. T. Loo, n.d., “Résumé des Opérations faites par M. Tangavelou pour essayer d’obtenir des antiquités pour M. Loo,” Folder for Correspondence from 1927, Jouveau-Dubreuil Archives, Musée National des Arts Asiatiques–Guimet, Paris.Secondary Sources

- Anila, Swarupa. 2017a. Inclusion Requires Fracturing. Journal of Museum Education 42: 108–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anila, Swarupa. 2017b. Polyvocality and Representation: What We Need Now. In Museum Education Roundtable. July. Available online: https://www.museumedu.org/polyvocality-representation-need-now/ (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Chance, Stacey Lynn. 2000. Investigation of the Goddess’ Ascetic Emanations: A Yogini Set from Tamilnadu. Master’s thesis, University of Missouri, Kansas City, MO, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Chanchani, Nachiket, and Tamara Sears, eds. 2015. Transmission of Architectural Knowledge in Medieval South Asia. Ars Orientalis 45. [Google Scholar]

- Dehejia, Vidya. 1986. Yogini Cult and Temples: A Tantric Tradition. New Delhi: National Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Dehejia, Vidya. 2021. The Thief Who Stole My Heart: The Material Life of Sacred Bronzes from Chola India, 855–1280. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deoras, V. R. 1957. Fresh Light on the Southern Campaigns of the Rāshṭrakūta Emperor Kṛishṇa III. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 20: 133–40. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, Debra, ed. 2013. Yoga: The Art of Transformation. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton, Richard M., and Phillip B. Wagoner. 2014. Power, Memory, Architecture: Contested Sites on India’s Deccan Plateau, 1300–1600. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, Emmanuel, and Charlotte Schmid, eds. 2016. The Archaeology of Bhakti II: Royal Bhakti, Local Bhakti. Pondicherry: Institut Français de Pondichéry and École Française d’Extrême-Orient. [Google Scholar]

- Handiqui, Krishna Kanta. 2011. Somadeva’s Yaśastilaka: Aspects of Jainism, Indian Thought and Culture, 2nd ed. New Delhi: Rashtriya Sanskrit Sansthan. First published 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Harle, James C. 2000. Finding the Kāñcī Yoginis. In Silk Road Art and Archaeology. Edited by Elizabeth Errington and Osmund Bopearachchi. Kamakura: Institute of Silk Road Studies, vol. 6, pp. 285–98. [Google Scholar]

- Harle, James C. 2008. Some New Light on the Kāñcī Yoginīs. In South Asian Archaeology 1999. Edited by Ellen M. Raven. Gonda Indological Studies. Groningen: Egbert Forsten, vol. 15, pp. 453–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hatley, Shaman. 2012. From Mātṛ to Yoginī: Continuity and Transformation in the South Asian Cults of the Mother Goddesses. In Transformations and Transfer of Tantra in Asia and Beyond. Edited by István Keul. Religion and Society. Boston: De Gruyter, vol. 52, pp. 99–129. [Google Scholar]

- Hatley, Shaman. 2013. What is a yogini? Toward a polythetic definition. In ‘Yoginī’ in South Asia: Interdisciplinary Approaches. Edited by István Keul. Routledge Series in Asian Religion and Philosophy 9; New York: Routledge, pp. 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hatley, Shaman. 2014. Goddesses in Text and Stone: Temples of the Yoginīs in Light of Tantric and Purāṇic Literature. In Material Culture and Asian Religions: Text, Image, Object. Edited by Benjamin J. Fleming and Richard D. Mann. New York: Routledge, pp. 195–225. [Google Scholar]

- Hatley, Shaman. 2019. Yoginī. In Hinduism and Tribal Religions, Encyclopedia of Indian Religions. Edited by P. Jain, R. Sherma and M. Khanna. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatley, Shaman. 2020. Tantra, Overview. In Hinduism and Tribal Religions, Encyclopedia of Indian Religions. Edited by P. Jain, R. Sherma and M. Khanna. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean, Alison, and Swarupa Anila. 2019. Whose Museum Is It Anyway? Towards More Authentic Community-Centered Practices in Creating Exhibitions. Exhibition 38: 42–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kaimal, Padma. 2012. Scattered Goddesses: Travels with the Yoginis. Asia Past & Present: New Research from AAS 8. Ann Arbor: Association of Asian Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Kaimal, Padma. 2013. Yoginīs in stone: Auspicious and inauspicious power. In ‘Yoginī’ in South Asia: Interdisciplinary Approaches. Edited by István Keul. Routledge Series in Asian Religion and Philosophy 9; New York: Routledge, pp. 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Kasdorf, Katherine E. 2013. Forming Dōrasamudra: Temples of the Hoysaḷa Capital in Context. Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Kasdorf, Katherine. 2016. Transporting Sculptures and Transferring Prestige: Hoysaḷa-Style Reuse in the Belur Āṇḍāḷ Shrine. South Asian Studies 32: 99–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keul, István. 2013. Introduction: Tracing yoginīs—Religious polysemy in cultural contexts. In ‘Yoginī’ in South Asia: Interdisciplinary Approaches. Edited by István Keul. Routledge Series in Asian Religion and Philosophy 9; New York: Routledge, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Risha. 2012. Constructing Community: Tamil Merchant Temples in India and China, 850–1281. Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Mahalingam, T. V. 1985. A Topographical List of the Inscriptions in the Tamil Nadu and Kerala States: North Arcot District. New Delhi: Indian Council of Historical Research. [Google Scholar]

- Masteller, Kimberly Adora. 2017. Temple Construction, Iconography, and Royal Identity in the Eastern Kalachuri Dynasty. Ph.D. dissertation, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Nagaswamy, R. 2006. Art and Religion of the Bhairavas illuminated by Two Rare Sanskrit Texts, Sarva-siddhānta-vivēka and Jñāna-siddhi. Chennai: Tamil Arts Academy. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, Imma. 2020. Tantra: Enlightenment to Revolution. London: The Trustees of the British Museum and Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, Charlotte. 2013. Aux frontiers de l’orientalisme, Scattered Goddesses, Travels with the Yoginis. Arts Asiatiques 68: 135–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M. J. 1997. Tirumalaicheri Inscription of Rashtrakuta Krishna III. Journal of the Epigraphic Society of India 23: 105–9. [Google Scholar]

- Sivaramamurti, C. 1955. Royal Conquests and Cultural Migrations in South India and the Deccan. Calcutta: Indian Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Emma Natalya. 2021. Constructing Kanchi: City of Infinite Temples. International Institute for Asian Studies Publications, Asian Cities Series; Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan, S. 2012. South Indian Inscriptions. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India, vol. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Venkataraman, K. R. 1973. Dēvī Kāmākshī in Kāñchī: A Short Historical Study. Tiruchirapalli: Sri Vani Vilas Press. [Google Scholar]

- White, David Gordon, ed. 2000. Tantra in Practice. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stein, E.N.; Kasdorf, K.E. Alternate Narratives for the Tamil Yoginis: Reconsidering the ‘Kanchi Yoginis’ Past, Present, and Future. Religions 2022, 13, 888. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13100888

Stein EN, Kasdorf KE. Alternate Narratives for the Tamil Yoginis: Reconsidering the ‘Kanchi Yoginis’ Past, Present, and Future. Religions. 2022; 13(10):888. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13100888

Chicago/Turabian StyleStein, Emma Natalya, and Katherine E. Kasdorf. 2022. "Alternate Narratives for the Tamil Yoginis: Reconsidering the ‘Kanchi Yoginis’ Past, Present, and Future" Religions 13, no. 10: 888. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13100888

APA StyleStein, E. N., & Kasdorf, K. E. (2022). Alternate Narratives for the Tamil Yoginis: Reconsidering the ‘Kanchi Yoginis’ Past, Present, and Future. Religions, 13(10), 888. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13100888