Abstract

This article examines perceptions of jin rituals in Tidore in order to explore how Austronesian perceptions of founders’ cults, arrival-order precedence, and stranger-kingship operate in determining social relations. Tidore origin narratives are significant historical texts that encode the social order and its power relations and so must be explored in greater depth. I analyzed rituals, origin narratives, and public discourse through interviews conducted with locals and particularly with four sowohi, the ritual specialists of jin worship. Additionally, I observed the public aspects of the jin ritual of inauguration of the sultan. The jin are the ancestral spirits and “true owners” of Tidore. Both the jin and sowohi are associated with the land and thus are the autochthonous leaders on the island. The sultan belongs to the stranger-king category, which was formed by later immigrant groups. During jin rituals of worship, the jin bless the sultan through the sowohi, who serve as mediums; this symbolizes the autochthonous flow of blessings to later immigrant groups. The rituals are also a recollection of a more primordial social order of heterogenous groups, which is based on the arrival-order precedence on Tidore.

1. Introduction

This article examines the jin worship in Tidore, North Maluku, Indonesia and investigates how this tradition is associated with Austronesian perceptions of the arrival-order precedence, founders’ cults, and stranger-kingship. I do so by scrutinizing how the relations binding the sultan and the sowohi (the ritual specialists of jin worship) can be understood in this context. Tidore is a small island located in the North Maluku Province. It is an economically and politically backwater of Indonesia, but the Tidore sultanate was one of the great maritime kingdoms in the premodern archipelago. The clove and nutmeg grown on sacred Kie Matubu (kie or kië means “mountain” in the Tidore language) brought the region fame as one of the legendary Spice Islands. Being an active participant in the Indian maritime trade, it began to embrace Islam from the mid-15th century (Baker 1988, p. 25), though local legends relate that Islam began to spread from the 9th century. The majority of the population is now Muslim.

The Tidore sultans were the religious and political leaders of the kingdom, and currently, a nominal sultan maintains symbolic authority as a regional emblem. Yet, there are the other types of symbolic leaders, called the sowohi, who have wielded great authority throughout Tidore history. While they are Muslims and hold the Islamic title of imam, the sowohi are considered the official channel for the public, including the sultan, to communicate with the jin, which refers to ancestral spirits in the Tidore context. Through summoning and propitiating the jin through trance and ritual prayers, which consist of Qur’anic recitations, these ritual specialists seek blessings for the entire island. Their fame is quite widespread in Tidore and neighboring islands. Due to their significant roles in society, they are known as the juru kunci negara (key of the state) as well as the polar leaders of society in parallel with the sultan. In recent years, the syncretic nature of Islam’s association with ancestor worship has been challenged by the reformist Muslim circle of society (Probojo 2010). Yet, most local people say that syncretic Islam is a tradition of Tidore, as is evinced by an interview Probojo (2010, p. 530) conducted with a Tidorese:

Being Muslim in Tidore means accepting, worshipping and believing in one’s ancestor; this is never against Islam, Allah or the Prophet. To the Tidorese, the local tradition, i.e., that of the jin, is as important and valuable as Islam itself. Thus, in Tidore, Islam must be accepted as having its origin in the spirit, jin, in their ancestor, gosimo [in Tid., ancestor]. To be Tidorese is to be ‘Islamic’ and Tidore is the home of Islam.

In this article, I analyze jin-worship practices in Islamized Tidore as well as the symbolic dual leadership of sowohi and sultan through multiple concepts related to Austronesian perception of territoriality and leadership. Austronesian culture was developed by Austronesian-speaking people, who began their migration from Taiwan in approximately 3000 BCE, reaching the Philippines, the Malay World, and more remote pacific islands of Micronesia and Polynesia to the east and Madagascar to the west over the course of thousands of years. While the Tidore language does not belong to the Austronesian family but to the Papuan phylum, the culture and people intermingled with Austronesians through socioeconomic interactions (Andaya 1993, p. 104).

Many scholars have noted that these widely dispersed Austronesian islands reveal some homogenous traditions, including founders’ cults and stranger-kingship traditions, both of which are based on the arrival-order precedence (Fox 1994; Fox and Sather 2006; Lewis 1988; Reuter 2006; Vischer 2009). Numerous scholars have argued that the earliest clans, which established domains in the uninhabited islands, legitimized their chiefly status and rights over the land and natural resources (Bellwood 2006; Druce 2009; Sudo 2006). As the founders of the domains, they are revered as the ancestors of the land by the later immigrant clans. Meanwhile, the later immigrant groups were not able to obtain chiefly status because of their inferior arrival-order precedence. This drove them or junior members to launch new voyages to find new uninhabited islands and obtain such rights as the “owners of the land.” This notion of precedence is different from the Indic notion of hierarchy, which was well elaborated by Dumont (1980). While Dumont posited that the South Asian social relations were built on the ‘encompassment of the contrary,’ the social relations based upon the precedence order is not a fixed order but ‘can be disputed, with competing claims calling upon different traditions and ancestors’ (Druce 2009, p. 160).

Yet, once these societies had grown to a point that a central authority was needed to unify these heterogenous immigrant groups, the Austronesians tended to invite a foreigner (from the later immigrant groups in many cases) to be the king, a phenomenon that can be explained in part by stranger-kingship theory (Fox 2008; Henley 2002; Henley and Caldwell 2008; Lewis 2010; Sahlins 1985, 2008, among others). As the foreign king’s political power was “endowed” by the autochthonous leaders, who are often called the “lords of the land,” the latter maintained their great authority in the realms of local customs and rituals. Thus, many scholars have posited that Austronesian societies developed dual leadership or a diarchy: the aristocracy (the king’s group) and the autochthonous leaders (Forth 1981; Henley and Caldwell 2008; Lewis 1988, 2010).

In this article, I examine how the perception of jin worship substitutes for primordial Austronesian notions of founders’ cults and arrival-order precedence. I argue in particular that such notions have determined the relationship between the sowohi and the sultan, which belong to the autochthonous and stranger-king group, respectively, and I investigate how jin worship is located in this context. To this end, I analyze jin rituals, origin narratives, and public discourses. The analysis of origin narratives is important because many scholars have noted that the narratives of Austronesian societies are significant historical texts that encode the social order of groups and its power relations (Reuter 2006).

The first section of this paper explains the brief description of the sultanate and the roles of sowohi; the second section addresses perceptions concerning jin worship and the roles of sowohi and how such practices are understood in the contexts of Austronesian perception of founders’ cults and arrival-order precedence. The third section investigates the location of sultan of Tidore within the context of arrival-order precedence, and the final section investigates how the arrival-order precedence is reflected in jin rituals.

I conducted field research in 2018 in Tidore and Ternate and interviewed various people, including sowohi mahifa, Husain Sjah (the sultan of Tidore), Amien Faaroek (who holds a traditional office at the Tidore court equivalent to the prime minister), officers at the Tidore Tourist Office, local intellectuals like Mustafa Mansur, Budy Syahruddin, Zainal Rizal, Ibu Lily, and numerous local people. The interviews with three other sowohi (sowohi toduho, sowohi kie matiti, and sowohi makene malamo) were conducted through Mustafa Mansur, my research assistant-cum-local historian, in March 2021 in the village of Gura Bunga.

2. Dual Symbolic Leadership

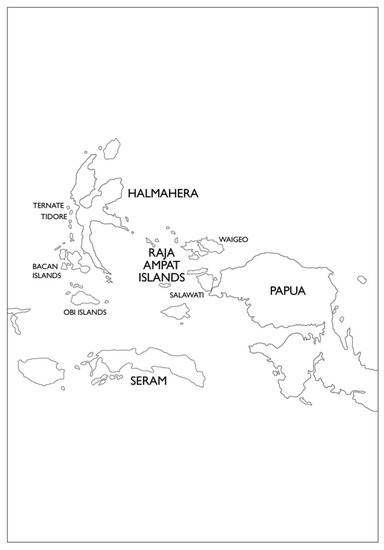

Tidore is a small, oblong-shaped island with a territory of 1550 km2. It has population of approximately 114,480 (BPS Kota Tidore Kepulauan 2021, p. xxvii). The much larger island of Halmahera is located to the east, while Ternate, an island almost identical to Tidore, is located to the north. Kie Matubu, with reaches a height of 1730 m, is located at the center of the Tidore (Figure 1). The people of Tidore are an admixture of heterogeneous ethnic groups that arrived on the island seeking their economic fortunes through the lucrative spice trade. Most inhabitants live along the narrow coast, but some villages are scattered on the slope of the mountain. Soa Sio on the coast is the administrative center and the former seat of the sultan’s kedaton (palace).1

Figure 1.

Map of North Maluku and Raja Ampat.

It is known that the Tidore Kingdom was established by Mohammad Nakel (also known as Sahyati) in the early 12th century (Rahman 2006, p. 4). Over the course of premodern history, the Tidore kings and sultans wielded great authority as the powerful overlords in central Halmahera and Papua, and they were called the dual leaders of the World of Maluku, together with the Ternate sultans (see Andaya 1993, pp. 47–112). The values of the cloves and nutmeg brought rival European powers and intervention into local politics from the 16th century, which continued until Indonesia was finally colonized by the Dutch in the early 20th century. After brief Japanese colonial rule (1942–1945) and a consequent revolution against the Dutch, who returned to the archipelago to recolonize it (1945–1949), the Indonesian Republic was established, and Tidore became a part of the republic. Due to the anti-feudal policies driven by the first president Sukarno (1945–1967), most feudal elites throughout archipelago had vanished by the late 1960s, and the Tidore sultanate also ended with the death of Sultan Zainal Abidin in 1967.

During the reign of Suharto, the second president of Indonesia (1967–1998), ethnic culture was promoted as a way of promoting local tourism, and a few feudal elites managed to sustain their symbolic kingships without substantial power. One of the examples is the late Mudaffar Sjah of Ternate (r. 1986–2015), who became sultan in 1986 (others were inactive) because of his strong support for Suharto and his ruling party, the Golkar. He revived forgotten Maluku traditions and rejuvenated symbolic kingship quite successfully. Immediately after Suharto resigned in 1998 as a result of the Asian financial crisis that swept over Indonesia from the previous year, Indonesia entered a new era of the promulgation of democracy and regional autonomy. Hundreds of regions revived nominal kingships as cultural and regional symbols. The Tidore court structure was also revived in 1999, following the model of the Ternate court. The current sultan, Husain Sjah, was inaugurated in 2012. While Tidore is under the administrative control of leaders typical of a republic, such as a governor and a mayor, the revived sultan exerts symbolic power among the people because of the traditional authority the sultanate amassed during the traditional era.2

Besides the sultan, there are the sowohi. Each village has a sowohi, whose role is to ritually serve villagers through jin worship. Of the many on the island, five particular sowohi (called fola sowohi in the Tidore language), whose privileged status results from their control over the jin ritual for the entire island, are the focus of this analysis. While other village-level sowohi require special rituals to communicate with the jin, the five sowohi can communicate with them without formal ritual, according to locals. The five sowohi include sowohi mahifa, sowohi kie matiti, sowohi toduho, sowohi tosofu malamo, and sowohi tosofu makene. They are said to come from the same mother clan.

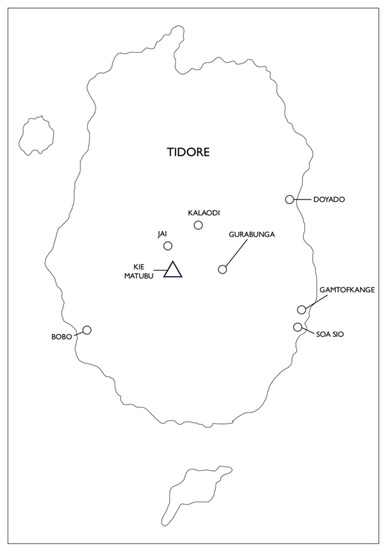

The five sowohi clans live in Gura Bunga, an isolated village located on the slopes of Kie Matubu (Figure 2). The original name of the village was Gurua Banga (lit., a lake in the forest), but in 1981, an official of the republic changed it to the more Malay-sounding Gura Bunga (lit., flower garden). The sowohi mahifa revealed that, before he received the mandate from the jin to be a sowohi, he worked as an ordinary physical education teacher at a school. From the jin, he inherited secret ancestral knowledge about and methods for conducting rituals. Typically, sowohi work as farmers, but every Wednesday and Sunday, they receive visitors who come for spiritual advice. The coastal people say that the people of Gura Bunga are uneducated and marginalized but good at magic. Achmad Mahifa, who was elected for two consecutive terms and was the first mayor of Tidore from Gura Bunga (2005–2015), wrote in his biography that Gura Bunga had special magical power (kekuatan gaib) and that he himself had observed numerous magical incidents when he was young. The tetua (elders, i.e., sowohi) had a good knowledge of herbal medicines and cured the sick through magic (Endah 2015, p. 46).

Figure 2.

Map of Tidore.

The Tidore people generally say that the jin have their own spiritual kingdom on the summit of the mountain, which exists in parallel with the kingdom on the coast led by the sultan. Like elsewhere in the archipelago, a mountain summit is considered the place for the “invisible kraton [palace], the seat of gods and the ancestors who have led exemplary lives” (Triyoga 1991, p. 30; quoted by Wessing 2006, p. 26). Thus, a summit is an eerie and sacred place, which only hermits and holy men visit for meditation. The location of sowohi’s houses on the slope of the mountain indicate that they are at the center of mythical power (pusat keajaiban) and have an intermediary status connecting spiritual (mountain) and human worlds (coast).

The sowohi are often compared with the sultan in dichotomous ways. The former are called the leaders of the “unseen or hidden world” (dunia hakikat), whereas the latter is considered the leader of the “seen or Islamic’ world” (dunia shariah). Baker (1988, pp. 222–23) explained the perceptions of hakikat and shariah as they operate in the village, writing that the hakekat (hakikat), “as the hidden essence of the village community, is a way of referring to jins … while the sareat [shariah] refers to the other forms of political and Islamic authority.”3 He added that this perception is extended to the state level, with the sowohi having “authority over the hidden essence (hakekat), while the sultan in the past had authority over the governmental administration (religious and secular) of the island state (Baker 1988, pp. 222–23). By this logic, sowohi are called jou tina (lit., inland lord) in contrast to jou lamo (supreme lord), which refers to the sultan (Baker 1988). Another metaphor that is used to describe sowohi in their capacity as mediator for the ancestor spirits is jou kornono (lord of darkness), whereas the sultan is called the jou sita-sita (lord of brightness) (Probojo 2010, p. 99). The authority of sowohi overwhelms the sultan on some issues. When they visit the sultan’s palace, they sit on the sultan’s seat covered with a white cloth, while the sultan is seated in an ordinary chair. Probojo (2010, p. 99) further described the head sowohi’s status vis-à-vis the sultan:

The status of this sowohi is higher even than the sultan, for he is closer to the ancestor spirits. As sowohi, he is the highest spiritual authority and the only person allowed to take care of the sultan’s grave, which is seen as sacred and magical … From a cultural and political perspective, this sowohi is still the most important person in Tidore, and in North Maluku in general. All decisions must have his agreement as the ‘spiritual’ owner of the island.

The Tidore people expect the sowohi to pray for the jin to receive blessings. Mahifa wrote that the sowohi’s power to bless made Gura Bunga successful in the cultivation of the spices (Endah 2015, p. 56). When there are natural disasters or invasions, the sultan and the public ask sowohi to comfort them. Andaya (1993, pp. 72–73) described the task of sowohi kië (which might refer to one of the sowohi of Gura Bunga) in the premodern era to be as follows:

His task was to ensure the performance of the proper rituals for the maintenance of the welfare of the kingdom. As the most spiritually potent figure in the land, he was entrusted with the care of the state regalia. The ordinary sowohi responded to appeals by the people for differing needs, ranging from help in securing the love of an individual to interceding with the gods for rain. But it was in the courts that the sowohi kië’s function was especially valued. One of the groups, the Tosofu Lamo of the Soa Rumtaha, was traditionally entrusted with the making of iron, an occupation of great prestige because of the sacred nature of forging. Only the sowohi kië was sufficiently imbued with sacral powers to be able to place the spiritually potent crown on the ruler’s head or to maintain the royal cemetery. In times of war he summoned the spiritual forces to assist the ruler in combat.

The Tidore people believe that neglecting to conduct the proper jin ritual can be detrimental, resulting in, for example, crop failure or the death of children.

Below, I briefly summarize some of the many narratives related to me by sowohi mahifa concerning the spiritual roles of sowohi historically, although the role of their spiritual power in these historical events cannot be verified. The first episode regards the integration of Dutch Papua (the western half of Papua) into the Indonesian Republic. Though the Dutch transferred its colonial territories to Indonesia in 1949, it retained this territory until 1963, when Sukarno’s military invaded and seized it. Papua’s racial composition and historical trajectory differ from other parts of Indonesia. Papua’s original settlers were the Melanesians, whereas most Indonesians are Austronesians. This region remained intact from outside influences, and so, inland Papuans were still using stone tools until the early 20th century. Sukarno needed to legitimize his scheme to seize of this “different” world by finding its historical connection to the rest of Indonesia. He eventually found that the Tidore sultans acted as overlords to the Raja Ampat area of Papua (Andaya 1993, pp. 99–110; Widjojo 2009, pp. 2–3). Sukarno requested the then sultan of Tidore, Zainal Abidin, accompany him to Papua and persuade the tribal leaders to join the republic. Because of Abidin’s contribution (though to what extent the sultan played a vital role in the integration of Papua is questionable), Tidore was designated as the capital of the newly-created Irian Jaya province, and Abidin was nominated its first governor in 1956.4 The sowohi mahifa explained that, before the sultan went to Papua, he visited the sowohi to consult with them on the matter and get authorization from the jin. Traditionally, Papua was one of the territories under the sowohi’s ritual control, as the sowohi’s invisible “jin soldiers” controlled the regions under the Tidore overlord’s rule, including Beda, Maba, Patani, Seram, Kei, Tanimbar, and Raja Ampat Islands. It was the sowohi, who asked the sultan to go with Sukarno. After the successful integration of Papua into Indonesia, the jin asked the sowohi to conduct the legu gam, an ancestor (jin) worship ritual, which was actually held afterward.

The second episode regards the reinstallation of the Tidore sultan in 1999. When the feudal elites returned in the post-Suharto era, the jin asked the sowohi to find a royal descendant who would inherit the sultan’s crown. If there was no one, the jin would take the royal crown back from the kedaton. When a few candidates were chosen from some royal clans, the jin pointed out one man, Djafar Sjah (r. 1999–2012), who was nominated.

The third episode relates to the communal violence that swept entire Maluku region in the aftermath of Suharto’s downfall. In the absence of central control, Indonesians who were repressed under the previous authoritarian rule fell into disastrous ethnic and religious conflicts, and North Maluku was hit more severely than other regions (Wilson 2008). Many villages in Tidore were burned down during the religious war between Muslims and Christians, producing significant human casualties. It was the sowohi who sent their jin soldiers to coastal Tidore and neighboring areas to calm the situation, which did finally return peace to the region. These narratives demonstrate that sowohi operate not only as personal ritual specialists but also as the state’s spiritual leaders, saving the island from various threats.

3. Jin Worship and Founders’ Cults

In this section, I analyze the meanings of jin and how jin worship is associated with the sowohi’s clans through the frames of arrival-order precedence and founders’ cults. Jin originally referred to spirits that were part of the Islamic world view. According to the Qur’an, Allah created the jin from fire before he created human beings. Yet, in many regions in Arabia and Indonesia, the term encompasses a wide range of spirits, and so, a jin can be a “demon, angel, ancestor, or deity” (Moreman 2017, p. 155). As mentioned above, the jin that sowohi communicate with refer specifically to ancestor spirits. The sowohi said that those who form relationships with jin during their lifetime become jin after their death. Among the human-originated jin, there are the pious Muslim jin that the sowohi communicate with and from whom they seek blessings. They were exemplary political and religious leaders in Tidore history, including former sultans, momole (tribal chiefs before the formation of the kingdom), and Islamic leaders. Their lives are similar to the lives of human beings, that is, they have state structures with a sultan and court functionaries and they get married, have children, and even use cell phones and cars. Perceiving jin as ancestral spirits indicates that local ideas of ancestor worship were transformed by adapting broader Muslim traditions. This is reminiscent of what Bowen (1993, p. 137) observed in Islamized Gayo society in Sumatra:

Gayo generally use the term jin to refer to one or more harmful spirits, or the entire category of such spirits, as in the all-inclusive expression jin iblis śetan (jin, devils, Satan…). But there are good jin as well as harmful ones. These “Muslim jin” (jin Islam) are the souls of people who had been extremely pious during their lives and were therefore spared death and were instead transmuted into spiritual beings. Also referred to as aulië, “saints,” or salihin, “pious ones,” they live in certain clearings in the forest, where, rarely, a favored human may come across them.

The local population believe that these Muslim jin help and guide their descendants by entering their bodies. This public perception is reminiscent of Chambert-Loir and Reid’s (2002) observation that famous “dead” ancestors in Indonesia acted as the primary consultants for the generations.

In Tidore, the jin also have significance as the “true owners of the island.” Probojo (2010, p. 98) wrote that “the Tidore say that the island actually belongs to their ancestor, who is an Islamic spirit (jin Islam).” This perception is connected with the well-elaborated perceptions of founders’ cults, which refer to the tradition of worshipping the “founders” who cleared the forest and established human domains. In this cult, the land spirits (or jin in many Islamized regions) are considered as the original “owners of the land” (See Aragon 2003, p. 115; Geertz 1960, pp. 23–28; Lehman and Hlaing 2003; Tannenbaum and Kammerer 2003). Lehman and Hlaing (2003, p. 19) argued that this kind of spirit ownership of the land is a tradition of Southeast Asia, which is abundant in land but lacks manpower. Such a tradition is also found among the many islands of Austronesian-speaking regions.

Numerous local origin narratives in Southeast Asia, then, narrate how the first human, who outsmarted the spirits, took the land tenure from the spirits by manipulating them, deceiving them, or making social contracts with them, and the land was thereby transferred from “the wild” to the “human domain” (Aragon 2003, pp. 115–16). Instead of taking the land, these human founders made contracts with the spirits, in which the spirits were “gods,” that is, objects of worship (Wessing 2006, p. 85), and the spirits remained the owners of the land and had an effect on the fertility and safety of the region. In this vein, Geertz (1960, p. 24) described the Babad Tanah Jawi (The Chronicle [or Clearing] of Java), the Javanese court chronicle that narrates the process of rendering the lands of the spirits to the people, as the “colonization myth,” because it narrates how the steady streams of migrants pushed back the “harmful spirits into the mountains, uncultivated wild places and the Indian Ocean … all the while adopting some of the more helpful ones as protectors of themselves and their new settlements.” Wessing (2006, p. 34) further explains this logic:

Before land is claimed for human habitation, a divinatory ritual is conducted in which it is assumed that if the spirits do not actively object, they acquiesce in the occupation of their land by human beings. Once the humans move in, one of the spirits is appointed as leader of what was until then a leaderless mob of wild spirits; in other words, the invading people incorporate the formerly non-social spirits into their social system. Having been appointed, this spirit is given offerings and is celebrated as the object of a cult…. In other words, the guardian spirit is in essence the victim of human trickery and its own greed.

Many origin myths also describe the roles of the genealogical ancestors who first cleared the forest by confronting the spirits. Buijs (2006, pp. 45–46) introduced the narrative of a female priest, called a toburake, who is revered as the ancestor of Mamasa Toraja in Sulawesi:

To enter the forest meant a precarious confrontation with the world of the gods. This myth about the settlement of the forest mentions several times that a female priest, toburake, had to go in front … Her role as the one who led the way for men who wanted to settle in the forest shows that this action was not religious-neutral. The wilderness is inhabited. It belongs to the deities of the forest … People cannot occupy the domain of others without offering compensation … Courage is needed and a strong determination to ‘seize’ the place, but above all offerings, prayers and promises are necessary … To make a dwelling place in the wilderness means a lasting dependence on its gods. They are the owners of the land. This belief and its religious consequences are widespread among the peoples of Southeast Asia.

This belief in spirit ownership of the land generally entails that the descent group (hereditary heirs) of the founder’s clan maintains its significance in providing “reciprocal rights and obligations that legitimates the working of the land” and thus, they become the meditators between the spirit lords and human settlers (Coville 2003, p. 88). This indicates the formation of the first important origin structure of society, whereby the founder’s clan secured its sacred genealogy and ritual authority in perpetuity. These human founders themselves also became the object of ancestor worship, and the rituals associated with this worship were exclusively controlled by their descendants. There are countless examples of how the first settlers and their descent groups have wielded great authority as the ritual overseers for generations. For instance, in Sumba, the first clan is called the tana puan, which literally means the “lords of the land.” Their spiritual and ritual roles raise their social status to higher than that of other clans. Lewis (1988) reported how the first clan, the Ipir in Tana‘ Ai on eastern Flores, has a special relationship with the autochthonous forest spirits, nitu noang, who have “always been there”; “other clans which immigrated later are dependent upon Ipir in spiritual matters” (quoted by Schefold 2001, p. 367). The female descendants of the toborake of Mamasa Toraja have upheld their roles as the ritual specialists until the present (Buijs 2006).

The jin cult of Tidore is also understood as part of the founders’ cult. According to the local legend, the jin are perceived as the original owners of the island, inhabiting it for over 2000 years before the first human arrived. In the distant past, the jin and humans mingled together on the Earth, until Allah separated the jin from human beings for playing tricks on the latter (Baker 1988, pp. 223–24). All sowohi interviewed said that the jin are called papa se tete (lit., parents and grandparents). It is they who gave the mandate (mandat) to human beings to protect (menjaga) the island. The proximity of the sowohi clans to the world of deity seems to be derived from their arrival-order precedence because the clans are known as the first settlers in Tidore.

However, I was unable to collect detailed narratives of how the sowohi’s ancestors interacted with the jin and acquired the symbolic land tenure. Sowohi mahifa said that revealing such information without ritual authority was strictly forbidden (Tid.: foso boboso) because it would result in the jin’s retribution. In fact, the tradition of being reluctant to speak about origin narratives because of a fear of ancestral retribution is very common in Southeast Asia (see Baker 1988, pp. 60, 67). Sowohi toduho explained that the first man in Tidore, whose name is prohibited from being revealed, married a jin and became the ancestor of the sowohi’s clans. Their clans were assigned by the jin to guard the lives of all who live on Tidore and acquired the rights to be spiritual mediums between the jin and human beings. What is certain is that the sowohi’s clans represent the land as an autochthonous group.

Many scholars have pointed out that in Tidore and elsewhere in North Maluku, certain clans have been associated with the “land” and called the “lords of the land”; they have also explained how the dual leadership of stranger-kings and lords of the land has operated throughout history (Andaya 1993; Baker 1988; Platenkamp 2013; Widjojo 2009). Andaya (1993, pp. 174–75), for example, mentioned that until the late 16th century, the powers of court functionaries (i.e., the bobato, members of the deliberative bodies or adat council and the heads of the soa) were apparent in their capacity to elect sultans and check executive powers in North Maluku, especially in Ternate and Tidore. The heads of the bobato are called jojau on Tidore or jogugu on Ternate, terms that literally mean lords of the land (Andaya 1993, p. 69). It was related to me by the jojau that the bobato clans in Tidore originated from the first nine settlements. Andaya (1993, p. 71) described the bobato council as follows:

These elders [referring to the council members] were chosen from the bobatos, who were heads of the soa … The bobatos’ links to the land are nowhere more clearly captured than in a ceremony still practiced in Tidore where items of the regalia are referred to as “bobato.” This description accords with a general phenomenon in all of monsoon Asia where the deity of the soil is made immanent among humans in an object, which becomes part of the regalia. During the ceremony the leader of the group is identified with the deity and becomes the medium through which the powers of the deity flow to guarantee the fertility and hence prosperity of the community. The identification of both the leader of the soa and the regalia as “bobato” would be in accordance with this conceptual framework of Southeast Asian indigenous beliefs and explains the ritual alliance of the bobatos with the jogugu as principal lord of the land.

The bobato are divided into two groups: bobato shariah, who deal with worldly matters, and bobato hakikat, who are in charge of the spiritual concerns of the state (see Widjojo 2009, p. 47). The five sowohi belong to the latter category. Andaya (1993, p. 71) explained that sowohi kië, literally “guardian of the mountain/land/kingdom” was the ritual functionary, who had the closet links to the jogugu. One of a sowohi’s ritual titles, jou tina, is translated as tuan tanah (Malay, “lord of the land”), and this indicates a sowohi’s position within the autochthonous groups in Tidore. The sowohi toduho and sowohi mahifa both explained that papa se tete, the true leaders of Tidore, gave authority to the sowohi to operate the “unseen ruling” (pemerintahan hakekat). It is through the sowohi that the jin mandated the sultan to operate under shariah rule.

In sum, generally the founders’ cult entails two types of objects of worship: “the unseen guardian deities” and the “ancestral spirits of those individuals who made successful agreements with the guardian deities” (Aragon 2003, pp. 115–16). In the case of Tidore, the sowohi’s clans were the first arrivals, and their arrival-order precedence gives them rights to be the channel of communication with the jin, the true owners of the land. Both the jin and the sowohi represent the land, forming the autochthons of Tidore.

4. The Sultan in the Context of Arrival-Order Precedence and Jin Worship

In this section, I examine the place of sultan as the group in opposition to the autochthonous group through the frames of the arrival-order precedence and jin-worship traditions. According to the royal origin myth, an Arabic man named Jafar Sadek (also called Jafar Sadik or Jafar Noh), known as the direct descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, arrived in the 11th or 13th century. By marrying a princess or jin called Nursafa or Tasuma (identity and names are disputed), who is described as the ancestor of the Tidorese, Jafar Sadek gained the right to open the shariah (Islamic) world on the coast. Their sons are known to be the founder kings of the four central states of the Maluku World, including Tidore, Ternate, Jailolo, and Bacan. This means that the four courts share common ancestry (Song 2020).5 Probojo (2000, p. 530) explained the marriage between Sadek and Nursafa:

This marriage [between Sadek and Nursafa] is understood as an alliance between Islam and the local tradition of ancestor worship, and the Tidore argue that their Islam can only be understood in the context of this legend. To be Muslim in Tidore inevitably means accepting this ancestor, and her worship is never seen as being in conflict with Islam.

Jafar Sadek’s Arab origin and marriage to a local princess or jin indicate that he belongs to the stranger-king category. By examining the stranger-kingship types of origin myths and the use of Malay words for the title of king (i.e., kolano, which was the term used in the late 15th century when sultan came into use), Andaya (1993, p. 65) also deduced that the Maluku rulers were foreigners. Throughout the archipelago, numerous royal origin myths narrate that their first kings came from Arabia, India, China, or other civilized Javanese or Melayu kingdoms. Some scholars consider this a consequence of the invasion of later immigrant groups (see Howard 1985; Sahlins 1985). Yet, others have pointed out that the autochthons chose of their own accord to place strangers on the throne. They did so because of the beneficial results: it prevented incest taboos, overheated competition, and the corruption that occurred when consanguineal kindred were maintained and because of his ignorance of the local society, this allowed the king to be an impartial to lead judge (Sahlins 2008; Gibson 2008; Henley and Caldwell 2008). An equally important reason was generated from the belief that these strangers came from culturally superior and commercially advanced regions and so could promote the region as center of commerce (Kathirithamby-Wells 2009; Gibson 2008). Wessing (2006, p. 85) also pointed out that the Arab ancestors introduced the new religion of Islam, which presented itself as representative of a moral order superior to the local one.

Regardless of whether Nursafa is identified as a local princess or jin, this indicates that she represented the autochthons, which formed in opposition to the stranger-king group (See Andaya 1993, p. 66). The union of Jafar Sadek and Nursafa, then, indicates that the later immigrant groups was inaugurated by the autochthonous population to be the king. Yet, installing a foreign king does not mean that the autochthons lost their significance within society, but the leadership did begin to diverge: the autochthonous leaders, who maintained authority as the ritual overseers and spiritual leaders, and the stranger-king group, which assumed control of secular politics. This tradition is often described as the diarchy (Forth 1981; Henley and Caldwell 2008; Lewis 1988, 2010; Sahlins 1985, 2008). Andaya (1993, p. 71) also mentioned that the influence of the sultan in Tidore in the premodern era “did not extend far beyond the boundaries of the royal settlement.” While most memory of the history of how these dual forces operated in Tidore politics has been lost, some traces of the symbolic representation of these diarchic elements remains, as Baker (1988, p. 16) has explained:

Such rule [secular rule] is always complemented by mediations with the supernatural—specifically, mediations with local spirits (jin) by the authority of the ‘lord of the land’ (the sowohi). The dualism is given in the very origin of the state. It is told that political order originated when a man from the Arab world, Jafar Sadek, came to the region and married a local jin, Nur Sifaa [Nursafa] … Since these origins, further divisions within the states have been made.

Andaya (1993, pp. 174–75) noted that European and Islamic perceptions of kingship led to a decline in the power of the lords of the land (bobato) while that of sultan’s power has strengthened in Ternate since the early 17th century (also see Widjojo 2009, pp. 30–52). Nevertheless, Tidore’s case shows a different historical trajectory. Andaya (1993, pp. 174–75) explained that the diarchic tradition was better preserved in Tidore, where the jojau, bobato, and the sowohi still maintain great authority. Baker (1988, p. 16) also explained that, in Tidore, at least, “the complementarity at all levels between political authority, ultimately derived from foreign sources, and spiritual authority, derived from local points of origin, has never been obscured.”

Sowohi’s control of the jin ritual indicates that the authority of the lords of the land still operates vis-à-vis the stranger-king group. By conducting and participating in the jin rituals, the two descent groups (the lords of the land and the stranger-king) confirm the affinal alliance and transfer of land ownership from the former to the latter. In this vein, Baker (1988, pp. 12–13) described the descent groups in Tidore as “comprehended as significant categories within an encompassing order by the continued fulfillment of alliance obligations,” which are “given viability by the rituals of alliance that at once differentiate and interconnect them.”6 In sum, the jin ritual is the representation of the historical alliance of two oppositional authorities of Tidore, each of which is derived from foreign sources and local points of origin. Thus, the sultan’s participation in jin rituals is important, as it is the fulfillment of this alliance obligation.

5. Jin Rituals, Seeking Blessings, and Land Ownership

The jin rituals in Tidore reflect the social relations established between the autochthons and later immigrant groups. The latter group seeks blessings from the jin through the sowohi, which is a recognition that the autochthonous group still has authority as the true owners of the land. This perception is vividly evinced in the current sultan’s inauguration process, which took place from April 2013 to June 2014. According to the Maluku tradition, the inauguration of the sultan follows a democratic procedure because it is the adat council, composed of bobato dunia and bobato hakikat, that elects the sultan (Usman et al. 2014, p. 2). On 15 April 2013, the bobato led by jojau invited four royal clans called fola raha to discuss the matter of election. They asked the four clans to recommend multiple qualified candidates, among whom Husain Alting was finally chosen. The next process is led by the bobato hakikat (bobato kornono), that is, the five sowohi. On 8 June 2014, Husain visited Gura Bunga in order to be “recognized” (diperkenalkan or dowaro) and receive authorization (restu) from the jin to be the sultan. The sowohi held a ritual, sodoa borero se suguci barakat papa se tete (lit., giving the messages and blessings of the ancestors). On June 15, Husain met sowohi kie matiti and participated in the ritual called sodohe ronga kolano toma bobato kornono (lit., concretizing/authorizing the title of sultan by the bobato kornono). Sowohi tomayou read the prayers of blessing (doa selamat), which finalized the hakekat aspect of the inauguration. After this “unseen” aspect of the inauguration, its shariah aspect (upacara penobatan sultan secara syareat) was held again at the court on the coast. It began with a reading from the Qur’an. The sultan entered the kamar puji (prayer room) where the royal crown was preserved.7 He put on the royal crown, and all the bobato at the court paid proper respects to the new sultan.

The other ritual that indicates that the autochthons are the source that blesses the stranger-king group is the annual royal ritual of legu gam, which is controlled by the five sowohi. Currently, it has been performed in commemoration of the creation day of Tidore sultanate in March and April.8 The apex of this ritual is the ake dango (lit., bamboo water) which is significant as the meeting of two polar leaders of Tidore, namely the sultan and the sowohi. The five sowohi deliver the sacred water contained in the bamboo tube to the sultan at the palace on the coast. The water source is located on top of the mountain. There is usually no water, but as the sowohi mahifa and tosofu malamo said that when the sowohi make a request to the jin, water suddenly begins to flow. The sowohi preserve the water in the bamboo barrel at the houses of the sowohi for a night. On that night, torchlights brightened the Sonine Gurua (an outdoor field in Gura Bunga that is used for rituals), and readings of borero gosimo (messages from the ancestors) commence. The next day, the water is brought to the palace by the sowohi, and the sultan drinks the water in front of the public. As Barnes (1974, p. 59) indicated, the water originates from the mountain indicating that is the “source of life,” and this ritual shows that life and authority flow from the mountain to the coast or from the autochthons to the later immigrant groups.

Bloch (1986) observed that water was also considered the source of blessings from an autochthonous group within the Austronesian-Merina group in Madagascar. He argued that the autochthon of the Merina region of Madagascar is the forest spirit called Vazimba, the female deity who is the owner of the lake. While explaining the importance of the circumcision ritual as the sources of society’s blessings, Bloch (1986, pp. 45–46) explained:

The other great ritual of blessing we must briefly consider in order to understand the circumcision ritual is the ritual of the royal bath … Until French rule, this was an annual ritual occurring at the turn of the lunar year. Its central aspect involved the ruler taking a bath in water brought from lakes where Vazimba queens were believed to have been buried. The water was brought to the palace by a group of youths ‘whose father and mother are still living’… who symbolised the continuation of descent.

Jin rituals, as the revelation of relations between autochthons and later immigrant groups, are also seen at the village level. Baker (1988, pp. 93–114) examined the jin ritual of Kalaodi Village in Tidore. The village was given by the sultan of Tidore sultan, Saefuddin (r. 1657–1687), to Tubulowone, a kapita (war leader) of Ternate in the premodern era. He helped the sultan who was seized by the Ternate and followed him to settle down in Tidore. The sultan asked the villagers of Doyado to give some land to Tubulowone, and Kalaodi Village was thereby created. Yet, the Kalaodi people have conducted the jin ritual propitiating the jin of Doyado (called legu Kalaodi, the local counterpart of the legu of the island) because the land is still considered to be in the ownership of the Doyado. Baker (1988, p. 293) explained this logic:

Because the soa of Doyado originally held possession of the land that Kalaodi received, members of this soa are still said to be its “owners.” This is so despite the Doyado’s relinquishment of all rights to make productive use of the land since their having turned it over to the Kalaodi under the authority of the sultan. What the Doyado have retained is their ritual authority as owners of the land; having this, their ritual leaders (gimalaha and joguru) are called upon by the Kalaodi when particular ceremony is required to help insure the productivity of the land and the well-being of the territory’s inhabitants. This original ownership, with its authority, is never lost or obscured by whatever subsequent land claims and divisions are made within the territory. But neither does it confer any control over how such subdivisions are made; it gives an historically embedded integrity and identity to the territory (and thus to the village) without cognizance of the divisions or organized use of land within the territory.

Baker (1988, p. 91) further noted that the villagers of Jai migrated from Tobaru, northwestern Halmahera, and were able to be the part of the division of the Gamtofkange subdistrict by meeting two criteria: conversion to Islam and participation in the legu of Gamtofkange. This indicates that, by participating in the jin ritual, the later immigrant groups were assimilated into the society of Tidore.

6. Conclusions

In this article, I examined how the Islamic jin perception replaced primordial Austronesian notions and how the sowohi and sultan are positioned in this context. Through the symbolism of jin worship, locals express their ideas about cosmogony and social relations, which are determined by the notions of the founders’ cult, arrival-order precedence, and stranger-kingship. Generally, the founders’ cult worshipped two entities: the spirits who are considered the true owners of the land and the ancestral spirits of individuals from the initially settled clans who were given tenure of the land.

In the case of Tidore, the sowohi’s clans were the first arrivals, and their arrival-order precedence gives them rights to be the channel of communication with the jin, the true owners of the land. They represent the lords of the land. Meanwhile, as the descendants of Prophet Muhamad, the sultans of Tidore belong to the stranger-king category. The relationship between the sultan and sowohi is considered to be like that between the lords of the land and immigrant groups. While the stranger-kings were given political roles, the sowohi—as the lords of the land—still controlled the adat and spiritual spheres. Their arrival-order precedence is reflected in the jin ritual, in which the former operates as the blessing-bestowing group while the latter is the blessing-receiving party.

This analysis is reminiscent of Durkheim’s (1960, p. 190) argument that “religion is seen as a symbolic expression of the reality of a society, which means that the ideas of a religion reflect social structures” (quoted by Buijs 2006, p. 38). The jin ritual is the recollection of the once established social order of heterogeneous immigrant groups in Tidore. By worshipping the local jin, the new groups gained membership to Tidore society.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2020S1A5A2A0104245812), and Hankuk University of Foreign Studies Research Grant of 2021.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The soa is the elementary territorial unit in Tidore, consisting of hali, which can be understood as an extended family or clan (Probojo 2000, p. 530). |

| 2 | Although their roles are symbolic, some traditional elites emerged as the important political actors in local politics (see Davidson and Henley 2007). The outstanding example is the late Mudaffar Sjah of Ternate. He was elected as a member of the National Parliament and local parliament. He sought election as the first governor of North Maluku Province, too. This success seems to have inspired sultans in the neighboring regions. The current Tidore sultan has been trying to be elected as the member of the National Parliament as well. However, I think that, by far, his role remains symbolic as the historical and cultural center of the island rather than a strong political actor in local politics. |

| 3 | The term, sharia, originally refers to the Islamic law based on the Qur’an. |

| 4 | The governor’s office was located on Tidore until it was moved to Jayapura in Irian Jaya Province in 1962. |

| 5 | While Nursafa was more often described as a jin or local princess in Tidore, three other regions describe her as the heavenly nymph (bidadari) (see Song 2020). |

| 6 | Yet, in some societies, these forest spirits are turned into something negative, rather than sources of blessing. Buijs (2006, p. 47) said that, in Mentawai, the wilderness has “become a negative element that is not able to produce blessings, but is often feared.” A similar pattern can also be seen in the origin myth of Pontianak, Kalimantan. In the myth, a Muslim man, a direct descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, came and expelled the fearful ghost, pontianak, establishing the Kingdom of Pontianak. Duile’s (2020) analysis showed that such female spirits were considered forest deities by the Dayak people, the original settlers of the forest, but because of Islamic influences, such deities were turned into fearful evil spirits. |

| 7 | The Tidore sultan said that this royal crown was inherited from Jafar Sadek, but further information is forbidden from being delivered. |

| 8 | Usually the rituals are held for two weeks in March–April, but the 2021 ritual was reduced because of the coronavirus pandemic. |

References

- Andaya, Leonard Y. 1993. The World of Maluku: Eastern Indonesia in the Early Modern Period. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aragon, Lorraine V. 2003. Expanding Spiritual Territories: Owners of the Land, Missionization, and Migration in Central Sulawesi. In Founders’ Cults in Southeast Asia. Edited by Nicola Tannenbaum and Cornelia Ann Kammerer. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 113–33. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, James N. 1988. Descent and Community in Tidore. Ph.D. thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, Robert Harrison. 1974. Kédang: A Study of the Collective Thought of an Eastern Indonesian People. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bellwood, Peter. 2006. Hierarchy, Founder Ideology and Austronesian Expansion. In Origins, Ancestry and Alliance: Explorations in Austronesian Ethnography. Edited by James J. Fox and Clifford Sather. Canberra: ANU Press, pp. 18–40. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, Maurice. 1986. From Blessing to Violence: History and Ideology in the Circumcision Ritual of the Merina. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, John R. 1993. Muslims through Discourse: Religion and Ritual in Gayo Society. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- BPS (Badan Pusat Statistik) Kota Tidore Kepulauan. 2021. Kota Tidore Kepulauan dalam Angka [Tidore Kepulauan Municipality in Figures]. Tidore: BPS Kota Tidore Kepulauan. [Google Scholar]

- Buijs, Cornelis W. 2006. Powers of Blessing from the Wilderness and from Heaven: Structure and Transformations in the Religion of the Toraja in the Mamasa Area of South Sulawesi. Leiden: KITLV Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chambert-Loir, Henri, and Anthony Reid, eds. 2002. The Potent Dead: Ancestors, Saints and Heroes in Contemporary Indonesia. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coville, Elizabeth. 2003. Mothers of the Land: Vitality and Order in the Toraja Highlands. In Founders’ Cults in Southeast Asia: Ancestors, Polity, and Identity. Edited by Nicola Tannenbaum and Cornelia Ann Kammerer. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 87–112. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, Jamie. S., and David Henley, eds. 2007. The Revival of Tradition in Indonesian Politics: The Deployment of Adat from Colonialism to Indigenism. London: Routledge, Contemporary Southeast Asia Series. [Google Scholar]

- Druce, Stephen C. 2009. The Lands West of the Lakes: A History of the Ajattappareng Kingdoms of South Sulawesi 1200 to 1600 CE. Leiden: KITLV Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duile, Timo. 2020. Kuntilanak: Ghost Narratives and Malay Modernity in Pontianak, Indonesia. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land-en Volkenkunde 176: 279–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, Louis. 1980. Homo Hierarchicus: The Caste System and Implications. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, Émile. 1960. Les formes élémentaires de la vie religieuse, 4th ed. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

- Endah, Alberthiene. 2015. Laki-Laki dari Tidore: Diangkat dari Kisah Nyata Achmad Mahifa [A Man from Tidore: Based on the True Story of Achmad Mahifa]. Jakarta: Gramedia Pustaka Utama. [Google Scholar]

- Forth, Gregory R. 1981. Rindi: An Ethnographic Study of a Traditional Domain in Eastern Sumba. The Hague: Nijhoff. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, James J. 1994. Reflections on ‘Hierarchy’ and ‘Precedence’. History and Anthropology 7: 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, James J. 2008. Installing the ‘Outsider’ Inside: The Exploration of an Epistemic Austronesian Cultural Theme and its Social Significance. Indonesian and the Malay World 36: 201–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, James J., and Clifford Sather, eds. 2006. Origins, Ancestry and Alliance: Explorations in Austronesian Ethnography. Canberra: ANU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, Clifford. 1960. The Religion of Java. New York: The Free Press of Glencoe. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, Thomas. 2008. From Stranger-king to Stranger-shaikh. Indonesia and the Malay World 36: 309–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henley, David, and Ian Caldwell. 2008. Kings and Covenants: Stranger-kings and Social Contract in Sulawesi. Indonesia and the Malay World 34: 269–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henley, David. 2002. Jealousy and Justice: The Indigenous Roots of Colonial Rule in Northern Sulawesi. Amsterdam: VU Uitgeverij. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, Alan. 1985. History, Myth and Polynesian Chieftainship: The Case of Rotuman Kings. In Transformations of Polynesian Culture. Edited by Antony Hooper and Judith Huntsman. Auckland: Polynesian Society, pp. 39–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kathirithamby-Wells, Jeyamalar. 2009. ‘Strangers’ and ‘Stranger-kings’: The Sayyid in Eighteenth-Century Maritime Southeast Asia. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 40: 567–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, Frederick K., and Chit Hlaing. 2003. The Relevance of the Founders’ Cult for Understanding the Political Systems of the Peoples of Northern Southeast Asia and its Chinese Borderlands. In Founders’ Cults in Southeast Asia: Ancestors, Polity, and Identity. Edited by Nicola Tannenbaum and Cornelia Ann Kammerer. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 15–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, E. Douglas. 1988. People of the Source: The Social and Ceremonial Order of Tana Wai Brama on Flores. Dordrecht: Foris Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, E. Douglas. 2010. The Stranger-kings of Sikka. Leiden: KITLV Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moreman, Christopher. M. 2017. Rehabilitating the Spirituality of Pre-Islamic Arabia: On the Importance of the Kahin, the Jinn, and the Tribal Ancestral Cult. Journal of Religious History 41: 137–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platenkamp, Jos D. M. 2013. Sovereignty in the North Moluccas: Historical Transformations. History and Anthropology 24: 206–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probojo, Lany. 2000. Between Modernity and Tradition: ‘Local Islam’ in Tidore North Maluku, the Ongoing Struggle of the State and the tradçitional Elites. Prosiding Symposium International Jurnal Antropologi Indonesia, 529–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probojo, Lany. 2010. Ritual Guardians versus Civil Servants as Cultural Brokers in the New Order Era: Local Islam in Tidore, North Maluku. Indonesia and the Malay World 38: 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, Maswin. 2006. Mengenal kesultanan Tidore [Understanding the Tidore sultanate]. Tidore: Lembaga Kesenian Keraton. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter, Thomas. 2006. Land and Territory in the Austronesian World. In Sharing the Earth, Dividing the Land: Land and Territory in the Austronesian World. Edited by Thomas Reuter. Canberra: ANU Press, pp. 11–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sahlins, Marshall. 1985. Islands of History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sahlins, Marshall. 2008. The Stranger-king or, Elementary Forms of the Politics of Life. Indonesia and the Malay World 36: 177–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schefold, Reimar. 2001. Three Sources of Ritual Blessings in Traditional Indonesian Societies. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land-en Volkenkunde 157: 359–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Seung-Won. 2020. A Heavenly Nymph Married to an Arab Sayyid: Stranger-kingship and Diarchic Divisions of Authority as Reflected in Foundation Myths and Rituals in North Maluku, Indonesia. Indonesia and the Malay World 48: 116–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudo, Ken-ichi. 2006. Rank, Hierarchy and Routes of Migration: Chieftainship in the Central Caroline Islands of Micronesia. In Origins, Ancestry and Alliance: Explorations in Austronesian Ethnography. Edited by James J. Fox and Clifford Sather. Canberra: ANU Press, pp. 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Tannenbaum, Nicola B., and Cornelia A. Kammerer, eds. 2003. Founders’ Cults in Southeast Asia: Ancestors, Polity, and Identity. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Triyoga, Lucas. 1991. Manusia Jawa dan Gunung Merapi. Persepsi dan Sistem Kepercayaannya [The Javanese and Mountain Merapi. Perception and Belief System]. Yogyakarta: Gadjah Mada University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Usman, Djumati, Yakub Husain, and Syofyan Saraha, eds. 2014. Tahapan Prosesi Pengangkatan Sultan Tidore ke-37 Hj. Husain Syah [Stages of the Procession of the Inauguration of the 37th Sultan of Tidore, Hj. Husain Syah]. Tidore: Rama Printing. [Google Scholar]

- Vischer, Michael P., ed. 2009. Precedence: Social Differentiation in the Austronesian World. Canberra: ANU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wessing, Robert. 2006. A Community of Spirits: People, Ancestors, and Nature Spirits in Java. Crossroads: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 18: 11–111. [Google Scholar]

- Widjojo, Muridan. 2009. The Revolt of Prince Nuku: Cross-Cultural Alliance-Making in Maluku, c.1780–1810. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Chris. 2008. Ethno-Religious Violence in Indonesia: From Soil to God. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).