Gogol’s “The Nose”: Between Linguistic Indecency and Religious Blasphemy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. God and Devil in “The Nose”

“Well, thank God nobody’s here.” he said. “Now I can take a look.” He went timidly up to the mirror and took a look: “The devil only knows! What rubbish!” he said, and spat. “If only there were something instead of my nose, but there’s nothing!”(III: 54/203)

3. Nosology as Rhinology: Noses in Russian Idioms and in Gogol’s Tale

3.1. The Problem: Why Is “The Nose” “Filthy”?

N. V. Gogol has objected to the printing of this jest for a long time; but we found in it so much that was unexpected, fantastic, merry, and original that we persuaded him to allow us to share with the public the enjoyment afforded us by his manuscript.(Gogol 1836, p. 54; quoted in Setchkarev 1965, p. 155)

3.2. “The Nose” as a “Linguistic Metaphor”

[the judge’s] nose unconsciously sniffed his upper lip, which it commonly did only from great satisfaction. Such perversity on the part of his nose caused the judge even more vexation: he took out his handkerchief and swept from his upper lip all the snuff, to punish its insolence.(II: 253/194–95)

“Tell me, by grace, […] why does the nose play such an enduring role here? The whole poem pivots on nothing but noses!”—“Because,” I reply as the poem’s insightful commentator, “the nose is perhaps the foremost source of ‘sublime, excited, lyrical laughter’.” —“I, however, can’t see anything funny in it,” you protest.—“You can’t but we can,” I argue back. “You must agree that this triangular piece of flesh which stands prominently in the center of man’s face is surprisingly, excitedly, lyrically funny. And it has already been proved that you can’t create anything truly amusing without a nose.(Senkovskii 1842, p. 37; also quoted in Vinogradov 1926, p. 151)

Do you believe that I often have a fierce desire to turn into nothing but a nose—so that there would be nothing else—neither eyes, nor arms, nor legs, just one super-tremendous nose the nostrils of which would be the size of big buckets so that I could inhale as much of the fragrance and spring as possible?(XI: 144; Gogol 1967, pp. 74–75; Shukman 1989, pp. 81–82 fn. 43)

Showing one’s nose, that is “going out”, as in “X doesn’t show his face/nose anywhere”: “But now I’ve gotten so terribly afflicted that I cannot show my nose anywhere [nikuda ne mogu nosa pokazat’]”.(X: 317)

Not seeing farther than one’s nose, that is “being narrow-minded”: “…who cannot see anything [nichego ne vidit] farther than his German nose [dalee svoego … nosa] and his merchantry”.(X: 341)

Sticking one’s nose in the air, or turning up one’s nose, that is “behaving arrogantly”, as in “X turns up his nose at everyone”: “Believe me, every human is a wader-bird [kulik], and if he sticks his nose up then his tail necessarily gets dunked. And so it must be, so that he not turn up his nose [at everyone] too much [ne slishkom podymal svoego nosa] and always bear in mind that he is mere rubbish”.(XII: 326)

Leading someone by one’s nose, that is “deceiving”: “…[to find out] who leads others by the nose [vodit za nos], who is just making fools of them [durachit], and who has or can have influence on them”.(XII: 409)

3.3. A Nose as a Phallus

For by the word Nose, throughout all this long chapter of noses, and in every other part of my work, where the word Nose occurs,—I declare, by that word I mean a Nose, and nothing more, or less.(Sterne 1761, p. 149; original emphasis)

Lechis’— il’ byt’ tebe Panglosom,Ty zhertva vrednoi krasoty —I to-to, bratets, budesh’ s nosom,Kogda bez nosa budesh’ ty.

Literally: “Get treatment, otherwise you will become a Pangloss,/you are a victim of harmful beauty,/and thus you surely will be ‘with the nose’/when you find yourself without one” (the translation of the two last lines is Erlich’s (1969, p. 86); Pangloss, a philosopher in Voltaire’s Candide, suffered from syphilis).

Ostat’sia bez nosu—nash Makkavei boialsia,Priekhal na vody—i s nosom on ostalsia.

Literally: “Our Maccabee15 feared finding himself without a nose./He came to the mineral waters for treatment and was left ‘with a nose’”.(see Okhotin’s commentary in Lermontov 2014, pp. 605–6).

Vozvratu tvoemu s pokhoda vsiak divitsia:Kak bez nosu poiti, a s nosom vozvratit’sia?

Literally: “Everyone is surprised by your return from the military campaign:/How could you leave without a nose and return with one?”

“My friend,” the visitor observed sententiously, “it’s sometimes better to have your nose put out of joint than to have no nose at all [s nosom vse zhe luchshe otoiti, chem inogda sovsem bez nosa], as one afflicted marquis (he must have been treated by a specialist) uttered not long ago in confession to his Jesuit spiritual director. I was present—it was just lovely. “Give me back my nose!” he said, beating his breast. “My son,” the priest hedged, “[…] If a harsh fate has deprived you of your nose, your profit is that now for the rest of your life no one will dare tell you that you have had your nose put out of joint [chto vy ostalis’ s nosom].” “Holy father, that’s no consolation!” the desperate man exclaimed. “On the contrary, I’d be delighted to have my nose put out of joint [ostavat’sia s nosom] every day of my life, if only it were where it belonged [na nadlezhashchem meste, literally, ‘on its proper place’]!” “My son,” the priest sighed, “[…] if you cry, as you have just cried, that you would gladly have your nose put out of joint [ostavat’sia s nosom] for the rest of your life, in this your desire has already been fulfilled indirectly; for, having lost your nose, you have thereby, as it were, had your nose put out of joint all the same [poteriav nos, vy tem samym vse zhe kak by ostalis’ s nosom]…”

You must agree that it is improper for me to walk around without a nose. […] with plans to obtain… and moreover being acquainted with ladies in many homes: Mrs. Chekhtaryova, the wife of a state councillor, and others… […] Forgive me… if one looks at this in conformity with the rules of duty and honor… you yourself can understand…(III: 56/205)

You also mention a nose. If you mean by this that I wished to lead you around by the nose [The idiom in the original reads “ostavit’ vas s nosom.”—IP] that is, to give you a formal refusal, I am amazed that you yourself are saying that, when I, as you well know, was of the exact opposite opinion, and if you are now asking in a legitimate fashion for my daughter’s hand in marriage, I am prepared this very minute to give you satisfaction, for this has always been the object of my most keen desire.(III: 71/221–22)

“Hey, Ivan!”—“What would you like, sir?“—“ What, wasn’t there a girl, a very pretty one, asking for Major Kovalyov?”—“No, sir!”—“Hmm!” said Major Kovalyov and looked in the mirror, smiling.(III: 399)

I must admit I do not understand why it has been ordained that women should take us by the nose as easily as they take hold of the handle of a teapot: either their hands are so created or our noses are fit for nothing better.(II: 241/184)

4. How the Table of Ranks Brought the Nose to the Kazan Cathedral

4.1. “The Nose” as a Cornerstone of the “Petersburg Text”

In “The Nose”, just as in the other “Petersburg Tales”, the main object of description is the satanic city taken in the confluence of both of its symbolic functions—secular (the brainchild of Peter the Great) and ecclesiastical (the city of the Apostle Peter), the latter being embodied in the Kazan Cathedral (which is, as is known, stylized as Saint Peter’s Basilica).

4.2. A Collegiate Assessor or a Major?

Kovalyov was a collegiate assessor of the Caucasus. He had only been at that rank for two years and therefore could not forget about it for a single moment, and so as to lend himself nobility and weight, he never called himself “Collegiate Assessor”, but always “Major”.(III: 53/202)

The collegiate assessors who receive that rank with the help of learned diplomas cannot at all be compared with those collegiate assessors who are created in the Caucasus. These are two quite particular types.(III: 53/201–2)

4.3. In Search of a Plumed Hat

Colonel Skalozub. The uniform’s the way to tell, ma’am.The braid, the shoulder-tabs, and gorget-tabs as well ma’am.

He was in a uniform with gold embroidery, with a large stand-up collar; he was wearing suede trousers and had a sword at his side. Judging by his plumed hat he bore the rank of state councillor.(III: 55/203–4)

Zhukovsky’s Saturdays are flourishing […]. Only Gogol […] livens them up with his stories. Last Saturday he read us a story about a nose which all of a sudden disappeared from the face of some Collegiate Assessor and turned up later in the Kazan Cathedral wearing the uniform of the Ministry of Education. Killingly funny! A lot of real humour.20 After having met his nose, the Collegiate Assessor tells him: “I am surprised at seeing you here; it seems to me you should know your place.(Viazemskii 1899, pp. 313–14; partly quoted in Gogol 1967, p. 7)

A dress of dark blue cloth with a stand-up collar and velvet cuffs of the same color; blue lining; the camisole and undershirt are white cloth; gilded plain buttons […] Gold embroidery in accordance with the attached pattern”.(quoted in Shepelyov 1999, pp. 311–12)

HIS IMPERIAL MAJESTY, upon the provision of this [issue] by the Committee, on 5th of this October, did MOST EMINENTLY deign […] to decree […] to the Civil Service that officials of the first five classes, who retired before 27 February 1834, be given the right to wear a plumed hat as before [nosit’ po-prezhnemu shliapu s pliumazhem] […] if they retired with the uniform approved for their last place of service.

[When Kotelnitsky] took a cab he would tell the cabman: “Look out, drive carefully—you are driving a state councillor!” The passion for ranks was then almost ubiquitous, and the good old boy Kotelnitsky was fascinated by the grandeur of his rank! […] [He] would go down after a full-dress function from the grand porch of the old university building wearing a uniform and triangular plumed hat [v treugol’noi shliape s pliumazhem] (at that time, officials of the 5th class and above wore plumes on their hats [pliumazh na shliapakh]) […].

4.4. The Two Thresholds

…this is the meaning of the story’s conflict: the struggle is between a man with the rank of collegiate assessor and a nose with the rank of state councillor. The nose is three ranks higher than the man. This conditions its victory, its invulnerability, and its superiority over the man.

4.5. To Know One’s Place

I tell you what, dear readers, there is nothing in the world worse than these high-class people. Because his uncle was a commissar once, he turns up his nose at everyone [nos nesyot vverkh]. As though there were no rank in the world higher than a commissar! Thank God, there are people greater than commissars. No, I don’t like these high-class people.(I: 195–96/90–91).

5. Liturgy, Sacrilege and the Calendar

5.1. The Problem: Why the Annunciation?

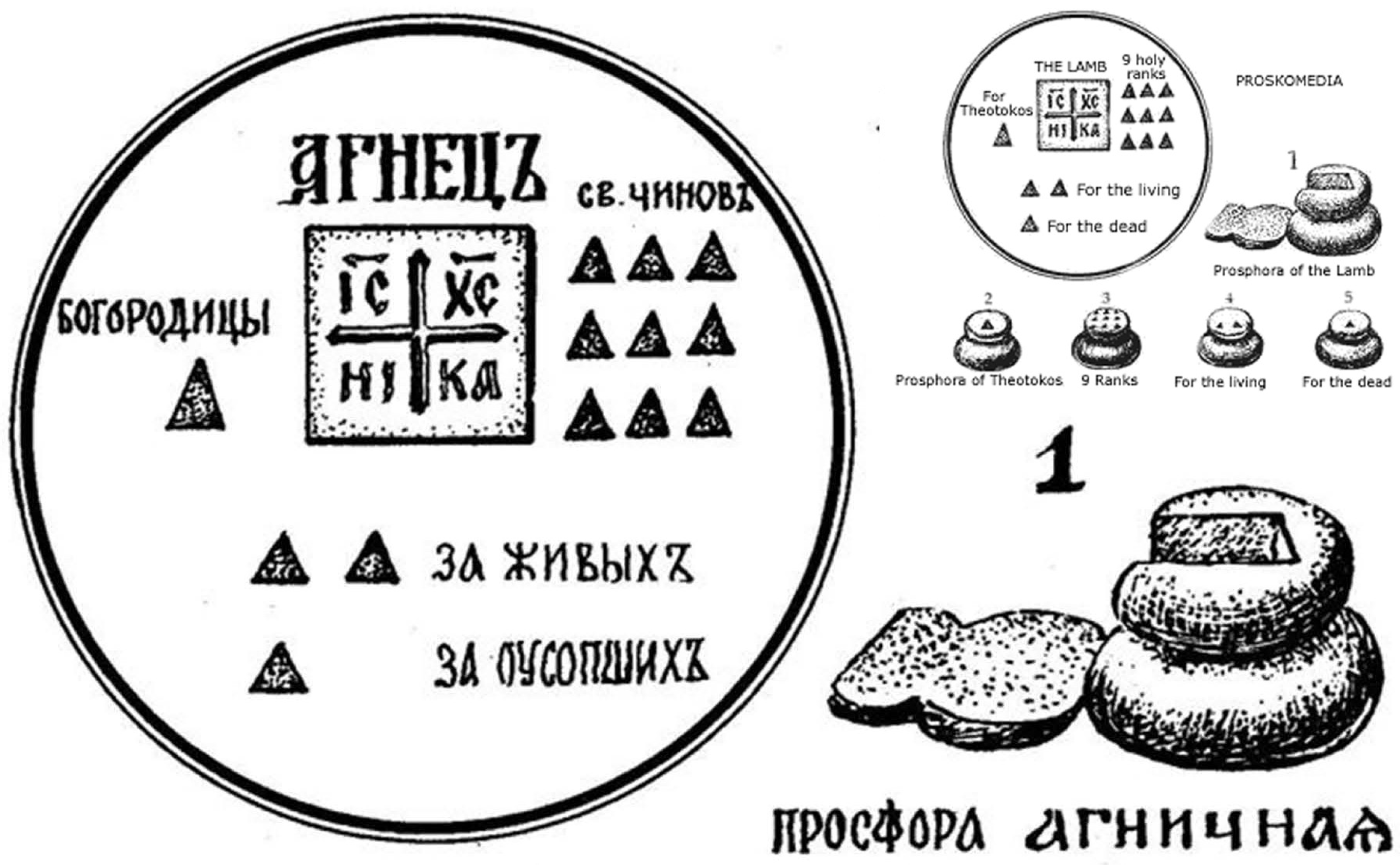

5.2. The Proskomedia in “The Nose” and in Meditations on the Divine Liturgy

All this part of the service consists in the preparation of what is required for the celebration, i.e., in the separation from the gifts, or little loaves of bread, of those sections which at first represent and are later to become the Body of Christ.

| IC | XC |

| NI | KA |

5.3. The Ascension and the Chronotope of “The Nose”

Therefore we were buried with Him through baptism into death, that just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, even so we also should walk in newness of life.(Rom 6:3–4)

Why then are they baptized for the dead? […] what you sow is not made alive unless it dies [KJV: “that which thou sowest, is not quickened except it die”]. […] So also is the resurrection of the dead. The body is sown in corruption, it is raised in incorruption. […] It is sown a natural body, it is raised a spiritual body.(1 Cor 15:29, 36, 42, 44).

“It is not quickened except it die,” says the Apostle.31 It is first necessary to die in order to be resurrected.(VIII: 297; cf. Gogol 2009, p. 108)

5.4. The Psychological and Cultural Background of Gogol’s Religious Blasphemy

Imagine that all along the way, in all cities, the temples are poor, the worship too, the priests are ignorant and unkempt […], to say nothing about the taste and fragrance of the sacrifices […].Thus I must confess that, against my will, I am visited by free-thinking and apostatical thoughts, and I feel my religious rules and faith in the true religion are weakening every minute, so that if only another religion could be found with skilled priests and especially sacrifices, like tea or chocolate, then farewell to the last piety [nabozhnost’].(XI: 173; Weiskopf 1993, p. 538 note 348)

I don’t want to produce anything minor! I can’t seem to think up anything great! In a word, mental constipation. Send me sympathy and wish me the best! Let your word be more effective than an enema.(X: 257)

What a terrible year 1833 has been for me! My God, how many crises! Will there be a benign restoration for me after these destructive revolutions? How much I started, how much I burned, how much I gave up! Do you understand the terrible feeling of not being content with oneself? […] The person who has been possessed by this hell of a feeling [eto ad-chuvstvo] is turned all to anger, he alone forms the opposition to everything, he makes a terrible mockery of his own ineptitude. My God, may it all be to the good! Say this prayer for me, too.(X: 277)

5.5. The Calendar of “The Nose”

And about the ninth hour Jesus cried out with a loud voice, saying, “Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani?” that is, “My God, My God, why have You forsaken Me?”(Mt 27:46)

…he needed a Christian holiday to serve as the background against which the appearance of the Nose would be the ultimate expression of the idea of the devil’s triumphant onslaught. For such a holiday, he chose the Annunciation, March 25, the day which brings the tidings of the forthcoming advent of the Savior.

6. Nosology as Hypnology: HOC as COH in Documents and Legends

7. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | “Contact zone” is Mary Louise Pratt’s term for “social spaces where cultures meet, clash and grapple with each other, often in contexts of highly asymmetrical relations of power” (Pratt 1991, p. 34). |

| 2 | References are provided to Gogol’s fourteen-volume complete collected works (Gogol 1937–1952) cited by volume: page (volumes are given in Roman numerals, and pages in Arabic numbers). The translations of Gogol’s Petersburg tales used here are those by Susanne Fusso (Gogol 2020). Earlier stories are quoted in Constance Garnett’s translation revised by Leonard J. Kent (Gogol 1985, vol. 1). The translation pages are cited after the original pages and divided by a slash. Other translations from Russian are by Igor Pilshchikov and Ainsley Morse if not indicated otherwise. |

| 3 | Etymologically, “slanderer.” From διαβάλλω [δια- (“across”) + βάλλω (“throw”)], “throw over or across, bring into discredit, mislead, calumniate, slander” (LSJ). |

| 4 | An East and West Slavic word with uncertain etymology; not used in South Slavic languages, including Church Slavonic. The Proto-Slavic *čьrtъ (“demon”) may be cognate with either the Proto-Slavic *čьrta (“line, boundary”) and its descendants or—less likely—with *čьrъ/*čьra (“spell, magic”) and its descendants (Trubachev 1977, pp. 164–66), or with both, as in the Czech čára, which means “a borderline up to which something is permitted or magically prohibited, e.g., the line which marks the so-called magic circle (where the evil demons retain or lose their power)” (Jakobson 1959, p. 276). Compare Andrei Bely’s intuition that “Gogol’s ‘devil’ [chort] derives from a line [cherta], and a line is a boundary” (Bely [1934] 2009, p. 182, see also p. 227; one needs to consult the original (Bely 1934, pp. 148, 186) to get the point). The chort’s synonym *běsъ < *běd-s-, also meaning “demon” (Church Slavonic: běsъ; Russian: bes; Ukrainian: bis) is cognate with the Proto-Slavic *běda (“trouble, calamity”) and *běditi (“compel, persuade”) (Trubachev 1975, pp. 88–91, 54–57). The Russian word chort is more colloquial and folkloric than bes. The Old Believers in the town of Mogilev shared a folk-belief that the devil rejoices when he is called by the Russian word chort (pronouncing this word is itself a sin), but does not like to be called by the Church Slavonic and ecclesiastic Russian word běsъ/bes because he hates everything related to church (Zelenin 1930, p. 89; Uspenskii 2012, p. 26). |

| 5 | The word bes is not used in “The Nose” (there is only one occurrence of the verb vzbesit’ of the same root, meaning “enrage”). In Gogol’s works and letters, the word bes is used 23 times (and the Ukrainian bis once), whereas chort occurs almost ten times as frequently. Pushkin, whose style sets the norm for this period, used bes 59 times and chort 91 times (a 2:3 ratio). On Pushkin’s usage of these words, see Vinogradov (1956–1961, vol. 1, pp. 96–97, vol. 4, pp. 926–27). |

| 6 | Emphasis added here and below if not attributed to the author. |

| 7 | The olfactory aspects of “The Nose” has recently been studied by Klymentiev (2009). |

| 8 | |

| 9 | For example, Emperor Nicholas I suggested that Alexander Pushkin should change “too trivial passages” in the first version of his Boris Godunov, where phrases such as “bliadiny deti” were used (the latter, meaning “sons of whores,” was later changed for sukiny deti, “sons of bitches”, and, eventually, postrely, “scamps”) (Vinokur 1935, pp. 423, 426; Pushkin 1937–1949, vol. 14, p. 59). |

| 10 | The names of these characters mockingly refer to the German literary tradition, whose actuality for Gogol was discussed by his readers and critics (see Meyer 2000, pp. 69–70; Kutik 2005, pp. 59–60). Ironically, Lieutenant Pirogov, another character in “Nevsky Prospect” who saw this scene, “could not understand what was going on”—not for mystical reasons, however, but simply because they spoke German, whereas his “knowledge of German did not go beyond ‘guten Morgen’” (III: 37/143). |

| 11 | See Kutik (2005, pp. 69–76), for a discussion of the “moon” topic and, in particular its connection with Ariosto’s Orlando furioso, canto 34. |

| 12 | |

| 13 | Etymologically, nos in the idiom byt’/ostat’sia s nosom has perhaps nothing to do with the nose, being supposedly a suffixless substantive of the verb (pri)nosit’ “to bring” (compare the pairs like beg//begat’ and the like). If so, nos meant “what is brought (as a gift or bribe),” and the meaning of the whole idiom was “to be left with what is brought, i.e., to be rejected a gift or bribe (such as a ritual bribe in wedding mediation).” However, in modern usage the original meaning of the idiom has been lost, and the speakers interpret nos in this phrase as “nose,” just like in all other idioms of this series (Shanskii 1960, p. 77, 1963, p. 67 fn. 1). The situation was not different in Gogol’s time (Dahl and Baudouin de Courtenay 1903–1909, vol. 2, p. 1443). Compare Bierich et al. (1994, p. 180). |

| 14 | See also Pushkin (1984, p. 123). |

| 15 | |

| 16 | Roman Jakobson cited this Dostoevsky passage as an example of “the abrogation of the boundary between real and figurative meanings” of idioms in poetic language (Jakobson [1921] 1973, pp. 67–68). On the same issue in Spanish translations of Dostoevsky see Obolenskaia (1980, pp. 58–59). |

| 17 | “A Petersburg Tale” is the subtitle of Pushkin’s narrative poem “The Bronze Horseman” (1833). Gogol’s Tales (1842) started to be routinely called “Petersburg Tales” as early as the 1880s. This non-authorial title was codified in academic parlance by the Gogol scholar Vladimir Shenrok (1893, p. 78). |

| 18 | On the Table of Ranks in Gogol’s fiction see Reyfman (2016, pp. 102–16). |

| 19 | Khlestakov, an irresponsible, frivolous young man, who is mistakenly identified as an inspector by the corrupt officials of a small Russian town in Gogol’s comedy The Government Inspector (1836), is a liar par excellence. According to Yuri Lotman: “Lying intoxicates Khlestakov because, in his imaginary world, he can cease to be himself, escape from himself, become someone else. […] The split personality which was to become the central focus of Dostoevsky’s Double […] was already present in Khlestakov” (Lotman [1975] 1985, p. 162). Lotman compares Khlestakov with the protagonist of “The Diary of a Madman”: “The deliverance from self and flight to life’s summits that Khlestakov receives from ‘an uncommon addle-headedness in thinking’ and a potbellied bottle of provincial Madeira, Poprishchin experiences as the price of insanity” (ibid., p. 163 fn. 29). Kovalyov belongs to the same type; if “‘Diary of a Madman’ is a tragic parallel to The Inspector General” (ibid.), then “The Nose” is a surrealist parallel to both. |

| 20 | Humour: English word in the original. |

| 21 | It should be added here that the censor excluded the references to specific ministries in the Nose’s conversation with Kovalyov from the printed text, so that the phrase under discussion was reduced to “Judging by the buttons on your uniform [vits-mundir], you must serve in a different department” (III: 486; Gogol 1836, p. 65, 1842, p. 97). This censored variant, reproduced in some twentieth-century editions, is translated in all English versions from 1916–2020, except the en regard translation by Gleb and Mary Struve. |

| 22 | This statement was disputed on the both sides of the Iron Curtain: the émigré scholar Nicholas Oulianoff (Oulianoff [1959] 1967, p. 160) and the Soviet scholar Yuri Mann (Mann 1966, pp. 37–38) objected to Yermilov’s interpretation. |

| 23 | |

| 24 | “The barber’s wife baking bread can be likened to one of the minor characters behind the scenes who participate in the process of the Mass: the special woman who bakes the liturgic bread. There were specific rules fixed by the ecclesiastics which obliged them to ‘choose as bakers of liturgic bread’ either ‘widows living in purity’ or virgins no younger than 50 years of age” (Glyantz 2013, p. 99). She obviously was neither virgin nor widow—nor, in fact, did she live in purity, judging by “complaints of an erotic nature, addressed to her husband” (ibid.). |

| 25 | In Gogol’s times, the word nis could have spelled as нисъ (the spelling of the printed editions of Ivan Kotlyarevsky’s foundational mock-epic Eneyida [the Aeneid]), нісъ (the spelling of Oleksiy Pavlovsky’s 1818 Ukrainian grammar) or ніс (the “spelling of The Mermaid of the Dniester” introduced by Markiyan Shashkevych in 1837). See (Ohiyenko 1927, pp. 5–8; Nimchuk 2004, pp. 6–8). |

| 26 | As an example, in the Ukrainian spelling that Mykhaylo Maksymovych proposed in 1827, the word nis was spelled etymologically, as нôсъ. See Ohiyenko (1927, pp. 6–7). |

| 27 | On the differences between the manuscript and the first published version see Gogol (1889, pp. 593–94) (Nikolai Tikhonravov’s commentary) and Voropaev (2000, pp. 189–90). |

| 28 | It has been proposed that the phrase “it seemed that heaven itself made him see the light” and sent him “directly to the advertising department of the newspaper” (III: 58/208) to place an announcement (III: 58/208) can also be read as a travesty of the Annunciation (Cornell 2002, p. 276). This is a questionable claim. First, in Russian, there is no straightforward correspondence between the words for “announcement” (ob”yavlénie) and “Annunciation” (Blagovéshchenie). In the latter, the first part, blago-, reflects the Greek εὐ- in Εὐαγγελισμός. The other part, -veshchenie, is used with a different stress in the words like izveshchénie (“notice”) but not in the word for “announcement.” Second, this episode is already contained without any allusion to the Annunciation in the 1836 redaction of “The Nose,” in which the strange events begin on 25 April and not on 25 March (see below). |

| 29 | On the dogmatic and anagogical meanings of the Proskomedia and the Eucharist accepted by the Russian Orthodox Church see Ivan Dmitrevsky’s Historical, Dogmatic and Mysterious Explication of the Liturgy (Dmitrevskii [1803] 1807) and Archbishop Benjamin’s The New Stone Tablet (Veniamin [1803] 1823)—the two main sources for Gogol’s Meditations on the Divine Liturgy (Frank 1999, p. 87 fn. 3; Voropaev 2000, p. 186). |

| 30 | Mistranslated as “the Ascension bridge” in Gogol 1916, p. 78. |

| 31 | Gogol quotes the Slavonic version: “ne ozhivet, ashche ne umret.” |

| 32 | Compare Iampolski (2007, pp. 560–61), on excessive materiality and imaginary illusion as exaggerated extremes in Gogol’s travesties of the Transubstantiation. In his mockery, Gogol comes close to mis/reinterpretations of the Eucharist as symbolic cannibalism (see Kitson 2000; compare Utz and Baatz 1998). |

| 33 | |

| 34 | On horror in “The Nose” see Bely ([1934] 2009, pp. 20–21, 227–28). |

| 35 | We know that on 4 April 1836, Gogol read his story at one of the “Saturdays” at Zhukovsky’s, as Vyazemsky reported to Alexander Turgenev (discussed above; see also Mann 2012b, p. 41). |

| 36 | The nearest April 25 that fell on Friday occurred in 1830. |

| 37 | Čiževsky’s observation goes back to Merezhkovsky ([1906] 1974, esp. pp. 57–58). On Merezhkovsky’s Gogol and the Devil see Hashemi (2017, pp. 157–62). |

| 38 | “The most outdated and least reliable of [Gogol’s] biographies” (Karlinsky 1976, p. 320). |

References

- Afanas’ev, Aleksandr. 1997. Narodnye russkie skazki ne dlia pechati, zavetnye poslovitsy i pogovorki, sobrannye i obrabotannye A. N. Afanas’evym, 1857–1862. Edited by Ol’ga Alekseeva, Valeriia Eremina, Evgenii Kostiukhin and Leonid Bessmertnykh. Moscow: Ladomir. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtin, Mikhail. 1968. Rabelais and His World. Translated by Helene Iswolsky. Cambridge: MIT Press. First published 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtin, Mikhail. 1976. The Art of the Word and the Culture of Folk Humor (Rabelais and Gogol’). In Semiotics and Structuralism: Readings from the Soviet Union. Edited with an Introduction by Henryk Baran. New York: International Arts and Sciences Press, pp. 284–96. First published 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Belinskii, Vissarion. 1955. Polnoe sobranie sochinenii. Moscow and Leningrad: Izdatel’stvo AN SSSR, vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Bely, Andrei. 1934. Masterstvo Gogolia: Issledovanie. Moscow and Leningrad: GIKhL. [Google Scholar]

- Bely, Andrei. 2009. Gogol’s Artistry. Translated from the Russian and with an Introduction by Christopher Colbath. Foreword by Vyacheslav Ivanov. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. First published 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Bem, Alfred. 1979. “The Nose” and “The Double”. In Dostoevsky & Gogol: Texts and Criticism. Edited and Translated by Priscilla Meyer & Stephen Rudy. Ann Arbor: Ardis, pp. 229–48. First published 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Bierich, Alexander, Valerii Mokienko, and Liudmila Stepanova. 1994. Istoriia i etimologiia russkikh frazeologizmov (Bibliograficheskii ukazatel’) (1825–1994) = Bibliographie zur Gesсhichte und Etymologie der russischen Phraseme (1825–1994). Munich: Otto Sagner. [Google Scholar]

- Bocharov, Sergei. 1985. Zagadka “Nosa” i taina litsa. In Gogol’: Istoriia i sovremennost’: K 175-letiiu so dnia rozhdeniia. Edited by Vadim Kozhinov. Moscow: Sovetskaia Rossiia, pp. 180–212. [Google Scholar]

- Bocharov, Sergei. 1992. Around “The Nose”. In Essays on Gogol: Logos and the Russian Word. Translated by Susanne Fusso. Edited by Susanne Fusso and Priscilla Meyer. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, pp. 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bocharov, Sergei. 2009. Peterburgskii tekst Vladimira Nikolaevicha Toporova. In Peterburgskii Tekst. Essays by Vladimir Toporov. Pamiatniki Otechestvennoi Nauki. XX vek. Moscow: Nauka, pp. 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bojanowska, Edyta. 2007. Nikolai Gogol: Between Ukrainian and Russian Nationalism. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, Herbert E. 1952. The Nose. Slavonic and East European Review 31: 204–11. [Google Scholar]

- Budagov, Ruben. 1953. Ocherki po yazykoznaniiu. Moscow: Izdatel’stvo AN SSSR. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Peter. 2017. Up the Dnepr: Discarding Icons and Debunking Ukrainian Cossack Myths in Gogol’s “Strashnaia mest’”. Russian Literature 93: 199–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, Claude. 1972. Les Proverbes Érotiques Russes: Études de Proverbes Recueillis et Non-Publiés par Dal’ et Simoni. Slavistic Printings and Reprintings 88. The Hague and Paris: Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Čiževsky, Dmitry. 1938. O “Shineli” Gogolia. Sovremennye Zapiski 67: 172–95. [Google Scholar]

- Čiževsky, Dmitry. 1952. Gogol: Artist and Thinker. The Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S. 2: 261–78. [Google Scholar]

- Čiževsky, Dmitry. 1952. The Unknown Gogol’. Slavonic and East European Review 30: 476–93. First published 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Complete Collection of the Laws. 1835. Polnoe Sobranie Zakonov Rossiiskoi Imperii. Seriia Vtoraia. Vols. 9.1 and 9.2: (1834). Saint Petersburg: The Typography of the Second Section of His Imperial Majesty’s Own Chancellery. [Google Scholar]

- Complete Collection of the Laws. 1857. Polnoe Sobranie Zakonov Rossiiskoi Imperii. Seriia Vtoraia. Vol. 31.2: (1856). Appendices. Saint Petersburg: The Typography of the Second Section of His Imperial Majesty’s Own Chancellery. [Google Scholar]

- Cornell, John F. 2002. Anatomy of Scandal: Self-Dismemberment in the Gospel of Matthew and in Gogol’s “The Nose”. Literature and Theology 16: 270–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwell, Neil. 1990. The Literary Fantastic: From Gothic to Postmodernism. New York and London: Harvester Wheatsheaf. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, Vladimir, and Ivan (Jan) Baudouin de Courtenay. 1903–1909. Tolkovyi slovar’ zhivogo velikorusskogo yazyka Vladimira Dalia, 3rd ed. Revised, and Substantially Enlarged. Edited by I. A. Baudouin de Courtenay. Saint Petersburg and Moscow: M. O. Wolf, 4 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Debreczeny, Paul. 1966. Nikolay Gogol and His Contemporary Critics. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. New Series 56.3; Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. [Google Scholar]

- Description of Changes. 1856. Opisanie izmenenii v forme odezhdy chinam grazhdanskogo vedomstva i pravila nosheniia sei formy. Saint Petersburg: The Typography of the Second Section of His Imperial Majesty’s Own Chancellery. [Google Scholar]

- Dilaktorskaia, Olga. 1984. Fantasticheskoe v povesti N. V. Gogolia “Nos.”. Russkaia Literatura 1: 153–66. [Google Scholar]

- Dilaktorskaia, Olga. 1995. Primechaniia. In Peterburgskie povesti. Tales by Nikolai Gogol’. Saint Petersburg: Nauka, pp. 258–95. [Google Scholar]

- Dmitrevskii, Ivan. 1807. Istoricheskoe, dogmaticheskoe i tainstvennoe iz”iasnenie na Liturgiiu, 4th ed. Moscow: The Synodal Typography. First published 1803. [Google Scholar]

- Dostoevskii, Fyodor. 1976. Polnoe sobranie sochinenii v 30 tomakh. T. 15. Leningrad: Nauka. [Google Scholar]

- Dostoevsky, Fyodor. 1991. The Brothers Karamazov. Translated from the Russian by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. New York: Vintage Classics. [Google Scholar]

- Dukes, Paul. 1978. Russia under Catherine the Great. Edited, Translated and Introduced by Paul Dukes. Select Documents on Government and Society. Newtonville: Oriental Research Partner, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Erlich, Victor. 1969. Gogol. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fanger, Donald. 1979. The Creation of Nikolai Gogol. Cambridge and London: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Feofan Prokopovich. 1961. Sochineniia. Moscow and Leningrad: Izdatel’stvo AN SSSR. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, Susi. 1999. Negativity Turns Positive: “Meditations Upon the Divine Liturgy”. In Gøgøl: Exploring Absence: Negativity in 19th-Century Russian Literature. Edited by Sven Spieker. Blsoomington: Slavica, pp. 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Galakhov, Aleksandr. 1886. Literaturnaia kofeinia v Moskve v 1830–1840 gg.: Vospominaniia. [Part 1]. Russkaia Starina 50: 181–92. [Google Scholar]

- Gillel’son, Maksim, Viktor Manuilov, and Anatolii Stepanov. 1961. Gogol’ v Peterburge. Leningrad: Lenizdat. [Google Scholar]

- Gippius, Vasilii. 1966. Tvorcheskii put’ Gogolia. Written in 1942. In Ot Pushkina do Bloka. Moscow and Leningrad: Nauka, pp. 46–200. [Google Scholar]

- Gippius, Vasilii. 1989. Gogol. Edited and Translated by Robert A. Maguire. Durham and London: Duke University Press. First published 1924. [Google Scholar]

- Glyantz, Vladimir. 2013. The Sacrament of End: The Theme of Apocalypse in Three Works by Gogol’. In Shapes of Apocalypse: Arts and Philosophy in Slavic Thought. Edited by Andrea Oppo. Boston: Academic Studies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gogol, Nikolai. 1913. Meditations on the Divine Liturgy. Translated by L. Alexéieff. London and Oxford: A. R. Mowbray & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Gogol, Nicholas. 1916. The Mantle and Other Stories. Translated by Claud Field, and with an Introduction on Gogol by Prosper Merimée. New York: Frederick A. Stokes. [Google Scholar]

- Gogol, Nikolai. 1836. Nos. Sovremennik 3: 54–90. [Google Scholar]

- Gogol, Nikolai. 1842. Sochineniia. Saint Petersburg: A. Borodin i K°, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Gogol, Nikolai. 1857. Razmyshleniia o Bozhestvennoi Liturgii. Saint Petersburg: P. A. Kulish. [Google Scholar]

- Gogol, Nikolai. 1889. Sochineniia, 10th ed. Edited by Nikolai Tikhonravov. Moscow: Knizhnyi magazin V. Dumnova, pod firmoiu “Nasledniki br. Salaevykh”, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Gogol, Nikolai. 1937–1952. Polnoe sobranie sochinenii. Moscow and Leningrad: Izdatel’stvo AN SSSR, 14 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Gogol, Nikolai. 1960. The Divine Liturgy of the Eastern Orthodox Church. Translated by Rosemary Edmonds. London: Darton, Longman & Todd. [Google Scholar]

- Gogol, Nikolai. 1967. Letters. Selected and Edited by Carl R. Proffer. Translated by Carl R. Proffer in Collaboration with Vera Krivoshein. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gogol, Nikolai. 1984. The Nose. Translated by Robert Daglish. Soviet Literature 433: 46–65. [Google Scholar]

- Gogol, Nikolai. 1985. The Complete Tales. Edited, with an Introduction and Notes, by Leonard J. Kent. The Constance Garnett Translation Revised by the Editor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Gogol, Nikolai. 1998. The Collected Tales. Translated and Annotated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. New York: Pantheon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gogol, Nikolai. 2004. Dead Souls: A Poem. Translated with an Introduction and Notes by Robert A. Maguire. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Gogol, Nikolai. 2009. Selected Passages from Correspondence with Friends. Translated by Jesse Zeldin. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gogol, Nikolai. 2020. The Nose and Other Stories. Translated by Susanne Fusso. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gregg, Richard. 1981. À la Recherche du Nez Perdu: An Inquiry into the Genealogical and Onomastic Origins of “The Nose”. Russian Review 40: 365–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griboedov, Aleksandr. 2006. Woe from Wit. A Commentary and Translation by Mary Hobson. Studies in Slavic Languages and Literature 25. Written in Russian in 1824. Lewiston, Queenston and Lampeter: The Edwin Mellen Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gukovskii, Grigorii. 1959. Realizm Gogolia. Moscow and Leningrad: GIKhL. [Google Scholar]

- Günther, Hans. 1968. Das Groteske bei N. V. Gogol’: Formen und Funktionen. Slavistische Beiträge 34. Minich: Otto Sagner. [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi, Oshank. 2017. Simvolistskie mify o N. V. Gogole (po materialam literaturnoi kritiki rubezha XIX–XX vv.). Russian Literature 93/94: 153–98. [Google Scholar]

- Holquist, James M. 1967. The Devil in Mufti: The Märchenwelt in Gogol’s Short Stories. PMLA 82: 352–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iampolski, Mikhail. 2007. Tkach i vizioner: Ocherki istorii reprezentatsii, ili O material’nom i ideal’nom v kul’ture. Moscow: Novoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie. [Google Scholar]

- Ilchuk, Yuliya. 2021. Nikolai Gogol: Performing Hybrid Identity. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobson, Roman. 1959. Marginalia to Vasmer’s Russian Etymological Dictionary (R–Ya). International Journal of Slavic Linguistics and Poetics 1/2: 265–78. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobson, Roman. 1973. Modern Russian Poetry: Velimir Khlebnikov [Excerpts]. In Major Soviet Writers: Essays in Criticism. Edited by Edward J. Brown. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 58–82. First published 1921. [Google Scholar]

- JMP. 2010. Izdatel’stvo Moskovskoi Patriarkhii provelo prezentatsiiu sobraniia sochinenii Nikolaia Gogolia v Kieve. Zhurnal Moskovskoi Patriarkhii 5: 86–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kalinin, Il’ya. 2010. “Peterburgskii tekst” moskovskoi filologii. Neprikosnovennyi Zapas 70: 319–26. [Google Scholar]

- Karlinsky, Simon. 1976. The Sexual Labyrinth of Nikolai Gogol. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kirsanova, Raisa. 1989. Rozovaia ksandreika i dradedamovyi platok: Kostium—veshch’ i obraz v russkoi literature XIX veka. Moscow: Kniga. [Google Scholar]

- Kitson, Peter J. 2000. “The Eucharist of Hell”; or, Eating People is Right: Romantic Representations of Cannibalism. Romanticism on the Net 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klymentiev, Maksym. 2009. The Dark Side of “The Nose”: The Paradigms of Olfactory Perception in Gogol’s “The Nose”. Canadian Slavonic Papers 51: 223–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondakova, Yuliya. 2009. Tekhnika “zavualirovannoi fantastiki” v proizvedeniiakh Gogolia. In N. V. Gogol’ kak germenevticheskaia problema. Edited by Oleg Zyrianov. Ekaterinburg: Ural University Press, pp. 137–56. [Google Scholar]

- Koropeckyj, Roman, and Robert Romanchuk. 2003. Ukraine in Blackface: Performance and Representation in Gogol’s Dikan’ka Tales, Book 1. Slavic Review 62: 525–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kutik, Ilya. 2005. Writing as Exorcism: The Personal Codes of Pushkin, Lermontov, and Gogol. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lachmann, Renate. 1999. The Semantic Construction of the Void. In Gøgøl: Exploring Absence: Negativity in 19th-Century Russian Literature. Edited by Sven Spieker. Bloomington: Slavica, pp. 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lanskoi, L., ed. 1952. Gogol’ v neizdannoi perepiske sovremennikov (1833–1853). In Pushkin. Lermontov. Gogol’. Literaturnoe Nasledstvo 58. Moscow: Izdatel’stvo AN SSSR, pp. 533–772. [Google Scholar]

- Lavrin, Janko. 1926. Gogol. London: George Routledge & Sons, New York: E. P. Dutton & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton, David. 1993. Blasphemy. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lermontov, Mikhail. 2014. Sobranie sochinenii v 4 tomakh. Volume Editor: Nikita Okhotin. Saint Petersburg: Izdatel’stvo Pushkinskogo Doma, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, Leonard W. 1981. Treason against God: A History of the Offense of Blasphemy. New York: Schocken Books. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, Leonard W. 1993. Blasphemy: Verbal Offense against the Sacred, from Moses to Salman Rushdie. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Lotman, Yuri. 1968. Problema khudozhestvennogo prostranstva v proze Gogolia. Uchenye zapiski Tartuskogo universiteta 209: 5–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lotman, Yuri. 1976. Gogol’ and the Correlation of “The Culture of Humor” with the Comic and Serious in the Russian National Tradition. In Semiotics and Structuralism: Readings from the Soviet Union. Edited with an Introduction by Henryk Baran. New York: International Arts and Sciences Press, pp. 297–300. First published 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Lotman, Yuri. 1985. Concerning Khlestakov. In The Semiotics of Russian Cultural History. Essays by Iurii M. Lotman, Lidiia Ia. Ginsburg, Boris A. Uspenskii. Translated from the Russian. Edited by Alexander D. Nakhimovsky and Alice Stone Nakhimovsky. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, pp. 150–87. First published 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Lotman, Yuri. 1990. Universe of the Mind: A Semiotic Theory of Culture. Translated by Ann Shukman. London and New York: I. B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Lounsbery, Anne. 2021. Nikolai Gogol, Symbolic Geography, and the Invention of the Russian Provinces. In The Palgrave Handbook of Russian Thought. Edited by Marina F. Bykova, Michael N. Forster and Lina Steiner. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 491–506. [Google Scholar]

- Lubensky, Sophia. 2013. Russian-English Dictionary of Idioms, Revised Edition. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, Robert A. 1994. Exploring Gogol. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, Yuri. 1966. O groteske v literature. Moscow: Sovetskii Pisatel’. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, Yuri. 1973. Evoliutsiia gogolevskoi fantastiki. In K istorii russkogo romantizma. Edited by Yuri Mann, Irina Neupokoeva and Ulrich Vogt. Moscow: Nauka, pp. 219–58. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, Yuri. 1996. Poetika Gogolia: Variatsii k teme. Moscow: Coda. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, Yuri. 2012a. Gogol’. Kniga 1: Nachalo, 1809–1835. Moscow: RGGU. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, Yuri. 2012b. Gogol’. Kniga 2: Na vershine, 1835–1845. Moscow: RGGU. [Google Scholar]

- Martinsen, Deborah A. 2004. Shame’s Rhetoric, or Ivan’s Devil, Karamazov Soul. In A New Word on The Brothers Karamazov. Edited by Robert Louis Jackson. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, pp. 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Mashinskii, Semën, ed. 1952. N. V. Gogol’ v vospominaniiakh sovremennikov. Moscow: GIKhL. [Google Scholar]

- Merezhkovsky, Dmitry. 1974. Gogol and the Devil. In Gogol from the Twentieth Century: Eleven Essays. Selected, Edited, Translated, and Introduced by Robert A. Maguire. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 55–102. First published 1906. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Priscilla. 1999. Supernatural Doubles: Vii and The Nose. In The Gothic-Fantastic in Nineteenth-Century Russian Literature. Edited by Neil Cornwell. Amsterdam and Atlanta: Rodopi, pp. 189–209. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Priscilla. 2000. The Fantastic in the Everyday: Gogol’s “Nevsky Prospect” and Hoffmann’s “A New Year’s Eve Adventure”. In Cold Fusion: Aspects of the German Cultural Presence in Russia. Edited by Gennady Barabtarlo. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books, pp. 62–73. [Google Scholar]

- Mochul’skii, Konstantin. 1934. Dukhovnyi put’ Gogolia. Paris: YMCA Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mondry, Henrietta. 2003. Gogol’s Body, Rozanov’s Nose. In Gogol 2002: Gogol Special Issues in Two Volumes. Edited by Joe Andrew and Robert Reid. Essays in Poetics Publication 8. Keele: Keele Students Union Press, vol. 1, pp. 72–87. [Google Scholar]

- Morson, Gary Saul. 1992. Gogol’s Parables of Explanation: Nonsense and Prosaics. In Essays on Gogol: Logos and the Russian Word. Edited by Susanne Fusso and Priscilla Meyer. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, pp. 200–39. [Google Scholar]

- Morson, Gary Saul. 1998. Russian literature. In The New Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th ed. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., vol. 26, pp. 1003–11. [Google Scholar]

- Nabokov, Vladimir. 1961. Nikolai Gogol, Corrected edition. New Directions Paperbooks 339. New York: New Directions. First published 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, David. 1999. Blasphemy in Modern Britain: 1789 to the Present. Aldershot and Brookfield: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, David. 2007. Blasphemy in the Christian World: A History. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nimchuk, Vasil’. 2004. Perednie slovo. In Istoriia ukraïns’koho pravopysu XVI–XX stolittia: Khrestomatiia. Edited by Vasil’ Nimchuk and Nataliia Puriaieva. Kyiv: Naukova Dumka, pp. 5–26. [Google Scholar]

- Obolenskaia, Yuliya. 1980. Kalambury v proizvedeniiakh F. M. Dostoevskogo i ikh perevod na ispanskii yazyk. In Tetradi perevodchika 17. Mosow: Mezhdunarodnye Otnosheniia, pp. 48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ohiyenko, Ivan. 1927. Narysy z istoriï ukraïns’koï movy: Systema ukraïns’koho pravopysu. Populiarno-naukovyi kurs z istorychnym osvitlenniam. Warsaw: Zakłady Graficzne E. i dr K. Koziańskich. [Google Scholar]

- Oulianoff, Nicholas. 1967. Arabesque or Apocalypse? On the Fundamental Idea of Gogol’s Story “The Nose”. Canadian Slavic Studies 1: 158–71. First published 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Peace, Richard. 1981. The Enigma of Gogol: An Examination of the Writings of N. V. Gogol and Their Place in the Russian Literary Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pilshchikov, Igor. 2019. K poetike i semantike gogolevskogo “Nosa”, ili Chto skryvaiut govoriashchie detali. In Literaturoman(n)iia: K 90-letiiu Yuriia Vladimirovicha Manna. Moscow: RGGU, pp. 218–37. [Google Scholar]

- Pilshchikov, Igor. Forthcoming. Russkii mat: Chto my o nem znaem? (O proiskhozhdenii i funktsiiakh russkoi obstsennoi idiomatiki). Matica Srpska Journal of Slavic Studies, 100.

- Pletnyova, Aleksandra. 2003. Povest’ N. V. Gogolia “Nos” i lubochnaia traditsiia. Novoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie 61: 152–63. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, Mary Louise. 1991. Arts of the Contact Zone. Profession 91: 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Pumpianskii, Lev. 2000. Gogol’. Written in 1922–1923. In His Klassicheskaia traditsiia: Sobranie trudov po istorii russkoi literatury. Moscow: Yazyki russkoi kul’tury, pp. 257–379. [Google Scholar]

- Pushkin, Aleksandr. 1937–1949. Polnoe sobranie sochinenii. Moscow and Leningrad: Izdatel’stvo AN SSSR, 16 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Pushkin, Aleksandr. 1984. Epigrams and Satirical Verse. Edited and Translated by Cynthia Whittaker. Ann Arbor: Ardis. [Google Scholar]

- Putney, Christopher. 1999. Russian Devils and Diabolic Conditionality in Nikolai Gogol’s “Evenings on a Farm near Dikanka”. New York: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Rancour-Laferriere, Daniel. 1982. Out from under Gogol’s Overcoat: A Pychoanalytic Study. Ann Arbor: Ardis. [Google Scholar]

- Raskin, David. 1989. Chiny i gosudarstvennaia sluzhba v Rossii v XIX–nach. XX vv. In Russkie pisateli: Biograficheskii slovar’, 1800–1917. Moscow: Sovetskaia Entsiklopediia, pp. 661–63. [Google Scholar]

- Reyfman, Irina. 2016. How Russia Learned to Write: Literature and the Imperial Table of Ranks. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, William Woodin. 1976. Through Gogol’s Looking Glass: Reverse Vision, False Focus, and Precarious Logic. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rozanov, Vasilii. 1995. Genii formy (K 100-letiiu so dnia rozhdeniia Gogolia). In O pisatel’stve i pisateliakh. Moscow: Respublika, pp. 345–52. First published 1909. [Google Scholar]

- Seifrid, Thomas. 1993. Suspicion toward Narrative: The Nose and the Problem of Autonomy in Gogol’s “Nos”. Russian Review 52: 382–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senkovskii, Osip. 1842. Review of: Pokhozhdeniia Chichikova, ili Mertvye Dushi: Poema N. Gogolia. Biblioteka dlia Chteniia 53: 24–54. [Google Scholar]

- Senkovskii, Osip. 1936. Rukopisnaia redaktsiia stat’i o “Mertvykh dushakh.” Written in 1842. Annotated by Nikolai Mordovchenko. In N. V. Gogol’: Materialy i issledovaniia. Edited by Vasilii Gippius. Moscow and Leningrad: Izdatel’stvo AN SSSR, pp. 226–49. [Google Scholar]

- Setchkarev, Vsevolod. 1965. Gogol: His Life and Works. Translated by Robert Kramer. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shanskii, Nikolai. 1960. Iz russkoi frazeologii: Frazeologicheskie oboroty s tochki zreniia ikh leksicheskogo sostava. russkii yazyk v natsional’noi shkole 1: 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Shanskii, Nikolai. 1963. Frazeologiia sovremennogo russkogo yazyka. Moscow: Vysshaia shkola. [Google Scholar]

- Shapovalov, Veronica. 1988. A. S. Pushkin and the St. Petersburg Text. In The Contexts of Aleksandr Sergeevich Pushkin. Edited by Peter I. Barta and Ulrich Goebel. Lewiston, Queenston and Lampeter: Edwin Mellen Press, pp. 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Shenrok, Vladimir. 1893. Materialy dlia biografii Gogolia. Moscow: Tipografiia A. I. Mamontova. [Google Scholar]

- Shepelyov, Leonid. 1977. Otmenennye istoriei: Chiny, zvaniia i tituly v Rossiiskoi Imperii. Leningrad: Nauka. [Google Scholar]

- Shepelyov, Leonid. 1991. Tituly, mundiry, ordena v Rossiiskoi Imperii. Leningrad: Nauka. [Google Scholar]

- Shepelyov, Leonid. 1999. Chinovnyi mir Rossii: XVIII—nachalo XX v. Saint Petersburg: Iskusstvo-SPB. [Google Scholar]

- Shukman, Ann. 1989. Gogol’s The Nose or the Devil in the Works. In Nikolay Gogol: Text and Context. Edited by Jane Grayson and Faith Wigzell. Basingstoke and London: Macmillan, pp. 64–82. [Google Scholar]

- Slobodskoi, Serafim. 1967. Zakon Bozhii: Dlia sem’i i shkoly so mnogimi illiustratsiiami, 2nd ed. Jordanville: Holy Trinity Monastery. [Google Scholar]

- Slonimskii, Aleksandr. 1974. The Technique of the Comic in Gogol. In Gogol from the Twentieth Century: Eleven Essays. Selected, Edited, Translated, and Introduced by Robert A. Maguire. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 323–74. First published 1923. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel, Ruth. 1998. The Nose: Nos: Short story. In Reference Guide to Russian Literature. Edited by Neil Cornwell. London and Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn, pp. 334–35. [Google Scholar]

- Spycher, Peter. 1963. N. V. Gogol’s “The Nose”: A Satirical Comic Fantasy Born of an Impotence Complex. Slavic and East European Journal 7: 361–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statute on Civil Uniforms. 1834. Polozhenie o grazhdanskikh mundirakh. Saint Petersburg: The Typography of the Second Section of His Imperial Majesty’s Own Chancellery. [Google Scholar]

- Statutes of Civil Service. 1833. Svod Zakonov Rossiiskoi Imperii, poveleniem Gosudaria Imperatora Nikolaia Pavlovicha sostavlennyi: Uchrezhdeniia: Svod uchrezhdenii gosudarstvennykh i gubernskikh. Chast’ 3. Ustavy o sluzhbe grazhdanskoi. Saint Petersburg: The Typography of the Second Section of His Imperial Majesty’s Own Chancellery. [Google Scholar]

- Statutes of Civil Service. 1834. Prodolzhenie Svoda Zakonov Rossiiskoi Imperii. 1832 i 1833 gody. Saint Petersburg: The Typography of the Second Section of His Imperial Majesty’s Own Chancellery. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, Lawrence. 1761. The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman. London: R. and J. Dodsley in Pall-Mall, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Struve, Gleb. 1961. Russian Stories = Russkie Rasskazy: Stories in the Original Russian. Edited by Gleb Struve. With Translations, Critical Introductions, Notes and Vocabulary by the Editor. A Bantam Dual-Language Book. New York: Bantam Books. [Google Scholar]

- Todorov, Tzvetan. 1975. The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre. Translated from the French by Richard Howard. With a Foreword by Robert Scholes. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. First published 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Tolstoy, Mikhail. 1881. Vospominaniia. Chapters IV and V. Russkii Arkhiv II.1: 42–131. [Google Scholar]

- Toporov, Vladimir. 1984. Peterburg i peterburgskii tekst russkoi literatury. Uchenye zapiski Tartuskogo universiteta 664: 4–29. [Google Scholar]

- Toporov, Vladimir. 2009. Peterburgskii Tekst. Pamiatniki Otechestvennoi Nauki. XX vek. Moscow: Nauka. [Google Scholar]

- Trubachev, Oleg, ed. 1975. Etimologicheskii slovar’ slavianskikh yazykov: Praslavianskii leksicheskii fond. Moscow: Nauka, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Trubachev, Oleg, ed. 1977. Etimologicheskii slovar’ slavianskikh yazykov: Praslavianskii leksicheskii fond. Moscow: Nauka, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Tynianov, Yuri. 2019. Dostoevsky and Gogol (Toward a Theory of Parody). In his Permanent Evolution: Selected Essays on Literature, Theory and Film. Translated and Edited by Ainsley Morse and Philip Redko. Boston: Academic Studies Press, pp. 25–61. First published 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Tynianov, Yuri. 2019. On Plot and Fabula in Film. In His Permanent Evolution: Selected Essays on Literature, Theory and Film. Translated and Edited by Ainsley Morse and Philip Redko. Boston: Academic Studies Press, pp. 235–36. First published 1926. [Google Scholar]

- Uspenskii, Boris. 2004. Vremia v gogolevskom “Nose” (“Nos” glazami etnografa). Welt der Slaven 49: 335–46. [Google Scholar]

- Uspenskii, Boris. 2012. Oblik cherta i ego rechevoe povedenie. In Umbra: Demonologiia kak semioticheskaia sistema 1. Moscow: Indrik, pp. 17–65. [Google Scholar]

- Utz, Richard J., and Christine Baatz. 1998. Transubstantiation in Medieval and Early Modern Culture and Literature: An Introductory Bibliography of Critical Studies. In Translation, Transformation and Transubstantiation in the Late Middle Ages. Edited by Carol Poster and Richard J. Utz. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, pp. 223–56. [Google Scholar]

- Veniamin. 1823. Novaia Skrizhal’ ili Dopolnenie k prezhdeizdannoi Skrizhali s tainstvennymi ob”iasneniiami o tserkvi, o razdelenii eia, o utvariakh, i o vsekh sluzhbakh v nei sovershaemykh. Saint Petersburg: The Typography of the Imperial Orphanage. First published 1803. [Google Scholar]

- Veresaev, Vikentii, ed. 1933. Gogol’ v zhizni: Sistematicheskii svod podlinnykh svidetel’stv sovremennikov. Moscow and Leningrad: Academia. [Google Scholar]

- Viazemskii, Pëtr. 1893. Polnoe sobranie sochinenii. Saint Petersburg: M. M. Stasiulevich, vol. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Viazemskii, Pëtr. 1899. Ostaf’evskii arkhiv kniazei Viazemskikh. Edited by Vladimir Saitov. Saint Petersburg: M. M. Stasiulevich, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradov, Viktor, ed. 1956–1961. Slovar’ yazyka Pushkina. Moscow and Leningrad: Gosudarstvennoe Izdatel’stvo Inostrannykh i Natsional’nykh Slovarei, vols. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradov, Viktor. 1926. Etiudy o stile Gogolia. Voprosy Poetiki 7. Leningrad: Academia. [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradov, Viktor. 1929. Naturalisticheskii grotesk: Siuzhet i kompozitsiia povesti Gogolia “Nos.”. In Evoliutsiia russkogo naturalizma. Gogol’ i Dostoevskii. Leningrad: Academia, pp. 7–88. First published 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradov, Viktor. 1987. Gogol and the Natural School. Translated by Debra K. Erickson, and Ray Parrott. Introduction by Debra K. Erickson. Ann Arbor: Ardis. First published 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Vinokur, Grigorii. 1935. “Boris Godunov”: [A Commentary]. In Polnoe sobranie sochinenii. Edited by Aleksandr Pushkin. Leningrad: Izdatel’stvo AN SSSR, vol. 7, pp. 481–96. [Google Scholar]

- Virolainen, Maria. 2004. Gorod-mir i sakral’nyi siuzhet u Gogolia. In Gogol’ i Italiia. Edited by Rita Giuliani and Mikhail Weiskopf. Moscow: RGGU, pp. 102–12. [Google Scholar]

- Voropaev, Vladimir. 2000. Posledniaia kniga Gogolia (K istorii sozdaniia i publikatsii “Razmyshlenii o Bozhestvennoi Liturgii”). Russkaia Literatura 2: 184–94. [Google Scholar]

- Weiskopf, Mikhail. 1987. Nos v Kazanskom sobore: O genezise religioznoi temy. Wiener Slawistischer Almanach 19: 25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Weiskopf, Mikhail. 1993. Siuzhet Gogolia: Morfologiia. Ideologiia. Kontekst. Moscow: Radiks. [Google Scholar]

- Whickman, Paul. 2020. Blasphemy and Politics in Romantic Literature: Creativity in the Writing of Percy Bysshe Shelley. London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward, James B. 1981. The Symbolic Art of Gogol: Essays on his Short Fiction. Columbus: Slavica. [Google Scholar]

- Yermakov, Ivan. 1921. Posleslovie. In N. V. Gogol’. Nos: Povest’. Moscow: Svetlana, pp. 83–129. [Google Scholar]

- Yermakov, Ivan. 1974. “The Nose”. In Gogol from the Twentieth Century: Eleven Essays. Selected, Edited, Translated, and Introduced by Robert A. Maguire. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 156–98. First published 1924. [Google Scholar]

- Yermilov, Vladimir. 1952. N. V. Gogol’. Moscow: Sovetskii Pisatel’. [Google Scholar]

- Young, Donald. 1979. Ermakov and Psychoanalytic Criticism in Russia. Slavic and East European Journal 23: 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelenin, Dmitrii. 1930. Tabu slov u narodov vostochnoi Evropy i severnoi Azii: II. Zaprety v domashnei zhizni. Sbornik Muzeia Antropologii i Etnografii 8: 1–166. [Google Scholar]

- Zhatkin, Dmitrii. 2002. Makkavei: Opyt osmysleniia bibleiskogo obraza. Tarkhanskii Vestnik 15: 50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Zhivov, Viktor. 1981. Koshchunstvennaia poeziia v sisteme russkoi kul’tury kontsa XVIII—nachala XIX veka. Uchenye zapiski Tartuskogo universiteta 546: 56–91. [Google Scholar]

- Zyrianov, Oleg. 2009. Traditsiia “fantasticheskogo realizma”. In N. V. Gogol’ kak germenevticheskaia problema. Edited by Oleg Zyrianov. Ekaterinburg: Ural University Press, pp. 120–37. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pilshchikov, I. Gogol’s “The Nose”: Between Linguistic Indecency and Religious Blasphemy. Religions 2021, 12, 571. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12080571

Pilshchikov I. Gogol’s “The Nose”: Between Linguistic Indecency and Religious Blasphemy. Religions. 2021; 12(8):571. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12080571

Chicago/Turabian StylePilshchikov, Igor. 2021. "Gogol’s “The Nose”: Between Linguistic Indecency and Religious Blasphemy" Religions 12, no. 8: 571. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12080571

APA StylePilshchikov, I. (2021). Gogol’s “The Nose”: Between Linguistic Indecency and Religious Blasphemy. Religions, 12(8), 571. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12080571