Abstract

Business as Mission (BAM) is a subcategory of Social Entrepreneurship as it seeks cultural innovation from a Christian perspective focusing specifically on economic uplift and religious direction. Most BAM authors describe the kingdom of God as the reign of God. In a theological review, I will show that defining kingdom simply as God’s rule is not a complete view of the kingdom. Rather, a more robust definition of the kingdom is preferred in biblical and theological studies that focuses on God’s people in God’s place under God’s rule. Therefore, the BAM community can adopt a refined definition that helps them move forward in the core vision of holistic ministry. This research provides a biblical and theological understanding for business practitioners to pursue a spiritual bottom line alongside local churches.

1. Introduction

Business as Mission (BAM) is a for-profit business in a cross cultural setting with a goal to participate in God’s mission in the world (Johnson 2009). From a Christian perspective, BAM is a subcategory of Social Entrepreneurship (SE) as it focuses on cultural goals for the common good of communities within for-profit companies. This fits as a cultural goal in the research of Braunerhjelm and Hamilton (2009, p. 28) suggesting that SE seeks to develop “economic, cultural, or political goals.” BAM is postured as holistic, practicing business as a blessing of common grace in the world helping to alleviate poverty and fulfill Christian ministry (Tunehag et al. 2004). BAM practitioners desire to seek the common good of their community even in the context of religious pluralism (Jeremiah 29:7). Therefore, a BAM business is unique through its organizational objectives as it seeks holistic work which Johnson and Rundle (2006) clarify pursues economic uplift and spiritual benefit.

One question among the BAM community is how should spiritual or kingdom objectives be defined and measured (Albright et al. 2014)? Some, similar to the Lausanne Occasional Paper #59 call for kingdom growth, which mentions a wide range of Christian activity such as poverty alleviation, prayer, witness, and ethics. There is evidence that the purpose of holistic ministry for kingdom impact is described in BAM as economic uplift and Great Commission impact (Rundle and Steffen 2011; Baer 2006; Lai 2015; Gort and Tunehag 2018; Eldred 2005). However, the term kingdom is often loosely defined, perhaps better said it is often described, in BAM literature leaving the door open for mission drift. Most notably, the Lausanne Occasional Paper #59 on BAM uses kingdom 163 times while never defining the term. To gain clarity for future momentum, a robust definition needs to be established for kingdom, and its impact on how to define and measure “kingdom objectives”.

This paper’s purpose will be to answer the question, “What is the definition of the kingdom from a biblical theology point of view, and does this definition have implications for a BAM practitioner?” This paper suggests that the BAM community began using the word kingdom as a broad category to enlarge the potential connections of business and mission. Authors commonly used the word kingdom as an adjective to describe the Christian intent for the work, but often the term used an assumed definition meaning holistic ministry outside the walls of the church.1 When defined, authors often rely on a definition for kingdom steeped in Protestant liberalism that has its own ministry implications that do not fit the holistic trajectory of the BAM movement. This paper will introduce a definition of kingdom through the biblical theological work of Graeme Goldsworthy to show how it can forward the core vision of BAM.

This paper will develop three sections that end in a tight connection between BAM businesses and local churches for kingdom objectives. First, the historical conversation on the kingdom produced a consensus understanding in a view coined inaugurated eschatology, the view that Jesus preached a kingdom present on earth that will be fulfilled at the end of time. Second, a definition of kingdom based on biblical theology best suits the holistic ministry objectives of the BAM community that ends in the dual objectives of economic development and local church impact. Third, a robust definition of the kingdom will have practical implications on the spiritual planning processes for a BAM company.

My perspective is evangelical Protestant. By evangelical, I agree with Graeme Goldsworthy (2012) in describing a large group of people with a trust in the reliability of the Bible to inform my definition of kingdom. This perspective is important due to the modern historical conversation of the kingdom rising from a Protestant liberal perspective that did not trust the reliability or unity of the entire Bible. This will shade my interpretation of the conversation in the last century.2 In my reading, many practitioners, and scholars in BAM that view their social concern as a kingdom objective come from a similar perspective with a high regard for the Bible seeking for the practitioners’ business in some way to be connected to the Bible’s narrative. The following article seeks to provide concepts and clarity on the ways a business can be connected to the Bible’s narrative.

2. The History of Defining the Kingdom of God

While there have been excellent arguments for a biblical basis for BAM (e.g., Russell 2010), there is not a resource that helps a BAM practitioner define the crucial definition of kingdom in context of the historical conversation. The history of interpretation on the kingdom since the 19th century is a classic pendulum swing. For interpreting the kingdom, scholars argued that either the kingdom was entirely inaugurated (now) or the kingdom was entirely eschatological (future). Pendulums, however, come to rest in the middle over time. When scholars later came to a consensus on inaugurated eschatology, the pendulum rested in the center with a “both-and” view.

In this section, a summary will be given for interpreting the kingdom from the 1870s until now.3 The movement began with Albert Ritschl's emphasis on the kingdom as present. Scholars Schweitzer and Weiss represented a shift to thinking of the kingdom as primarily eschatological (future). Later, figures such as Dodd, Ladd, and Kümmel produced a middle way that connected both the kingdom present and the kingdom future into the message of Jesus and the church.

2.1. The Kingdom Present

Albert Ritschl began to write about the kingdom with his pupils in the 19th century, and originally established that the kingdom of God was entirely of this world. Ritschl was a representative of social liberalism which dominated the theological establishment of his day. He questioned whether Jesus really thought the kingdom was a future event or was Jesus more concerned about the social ethics of the people present? He concluded that the kingdom message of the historical Jesus was an ethical message that provides liberation for the people Jesus taught (Willis 1987).

Protestant liberalism, using historical critical analysis, tilted Jesus’s teaching on the kingdom of God as a present reality more than eschatological reality. Richard Hiers (1987, p. 16) wrote: “Liberal Christianity viewed Jesus primarily as teacher and exemplar of a timeless ethic of love who had either proclaimed that the kingdom of God was present in the hearts of individuals through the experience of communion with God, or who had called people of all times to the task of bringing the kingdom of God (or extending its influence) on earth through moral action and social reform.”

BAM practitioners who practice holistic ministry often cite God’s rule in the individual or often seek social reform as a goal for ministry similar to Hiers summary of liberal Christianity (Russell 2010; Ewert 2006; Gort and Tunehag 2018). This raises the question, “Is there a difference in perspective or objectives for an evangelical BAM practitioner to work towards holistic ministry?”

2.2. The Kingdom Future

In the 1890s, authors Albert Schweitzer and Johannes Weiss began to swing the academic pendulum by focusing on the future, eschatological kingdom. Weiss posited six characteristics of the kingdom: (1) It is radically transcendent and supramundane (not of this world). (2) It is radically future and in no way present. (3) Jesus was not the founder or inaugurator of this kingdom, but he waited for God to bring it. (4) The kingdom is in no way identified with Jesus’ circle of disciples. (5) The kingdom does not come gradually by growth or development. (6) The ethics that the kingdom sponsors are negative and world-denying (Willis 1987, p. 4).

These characteristics from Weiss offer a stark contrast against the liberal theological assertion of the day that the kingdom is equated to ethical conduct. These characteristics also developed a withdrawal mentality towards culture.

Schweitzer, also, wrote against the consensus of an ethical interpretation. He stressed an eschatological view of Jesus and the kingdom. Schweitzer taught Jesus preached “interim ethics” in that “the kingdom of God is super-moral”. Willis’s (1987) summary concludes that interim ethics, for Schweitzer, were to enter the kingdom, not the morality of the kingdom. Therefore, Schweitzer emphasized that the kingdom is not of this world and future oriented. I have never seen a BAM practitioner hold to a sole eschatological view of the kingdom. In fact, many correctly view holding only a future view of the kingdom does not adequately promote business objectives and creating business impostors with only shell companies which is not ethical.

2.3. The Kingdom–Inaugurated Eschatology

The thesis-antithesis context of the nature of the kingdom provided a path towards building a middle ground in the mid-20th century. C.H. Dodd was the anticipation of this middle way. He coined the term “realized eschatology,” meaning that the kingdom of God was present in the current time. For Dodd, the nature of the kingdom of God was the reign of God within the individual. Hiers (1987, p. 34) summarized Dodd’s unique position in the conversation as an anticipation of future scholars: “Dodd initially held that Jesus regarded the kingdom of God both as the future era of salvation that was coming, and as somehow already present. He thus anticipated the majority of later Anglo-Saxon scholars who maintained that for Jesus the kingdom of God was both present and in some (usually only unimportant) way future”.

Later, the fullness of the mediating position on the kingdom of God came from authors such as Werner Georg Kümmel and George Elden Ladd. For Kümmel, the message of Jesus was one of promise and fulfillment of the kingdom. Salvation was a reality through Jesus in whom God brought as a fulfillment in history. Moreover, through Jesus, God promised the fullness of the kingdom at the end of history. Kümmel treated the eschatological message as a true, world ending kingdom event that shaped Jesus’s views of God’s ethics (Epp 1987).

George Elden Ladd also saw promise and fulfillment in the kingdom of God, but he added a third component: Consummation (return of Christ). For Ladd, the kingdom is God’s kingly rule that has two moments: One moment is the fulfillment of Old Testament promises in Jesus, and the other moment is the consummation of the kingdom at the end of the age. Ladd’s framework differs decisively in implications than previous interpretations of the kingdom. Ladd diverged from the ethical view of the kingdom concluding it is God’s work, not man’s work. Ladd (1968, p. 53) writes, “God’s Kingdom is first of all his kingly rule, his sovereign redeeming activity, and secondarily the realm of blessing inaugurated by the divine act”. Therefore, while God is the divine actor of the kingdom, people experience the blessings in the “realm” of the kingdom presently. BAM proponents live in the tension of inaugurated eschatology. They know that work on earth matters and hope in the gospel of Jesus for eternal life. Yet the question remains, does the definition of kingdom adequately train practitioners to care about holistic endeavors?

Important to note for our conversation is the radical shift in philosophy of ministry one pursues depending on the definition of the kingdom one adopts. There are eventual implications for definitions. For example, Moore (2004, p. 27) shows how Carl Henry used inaugurated kingdom theology to avoid two extremes in his writing, “to avoid the social gospel and fundamentalist withdraw”. Avoiding these extremes also seems to be the interest of BAM practitioners as they seek holistic ministry (Baer 2006). Moore shows that Henry saw the social gospel, as presented by Walter Rauschenbusch, as an extension of “the anti-supernaturalistic presuppositions” that led to Protestant liberalism in the question of modernity during the larger secular Enlightenment. This view is based on a completely present kingdom concerned with kingdom ethics as proposed by Ritschl. However, Henry also denied fundamentalist withdrawal (to focus solely on conversion from the world) since the kingdom is fulfilled legitimately in the present age (Moore 2004). Therefore, Christians must engage our current age with a present and future hope of the kingdom. Henry’s use of inaugurated kingdom theology is an excellent example for BAM practitioners’ engagement today. Table 1 summarizes ministry emphases and implications based on a kingdom definition one adopts.

Table 1.

Historical implications based on kingdom of God definition.

3. The Kingdom Defined by Biblical Theology

George Ladd and Carl F. H. Henry’s work shifted a strand of studies of the kingdom from a Protestant liberal standpoint to an evangelical engagement (Moore 2004). Since then, evangelicals today have built upon their foundation through biblical theology.4 Biblical theology seeks meaning of the bible through the storyline of the bible interacting with the various literary and historical contexts (Goldsworthy 2012). Therefore, for our context, one must look at the progressive story of the Bible to define the kingdom. In a practical example, Tunehag writes about BAM through the three mandates in the Bible: The Cultural Mandate, the Great Commandment, and the Great Commission (Gort and Tunehag 2018).5 However, biblical theology points out that we cannot understand these three texts as separate commands, but one unified narrative. Myers in Walking with the Poor (Myers 2011), a classic work in development, connects holistic ministry with understanding the unity of the Bible’s whole story. It seems BAM practitioners are hungry for a biblical theological definition of kingdom.

This is important for BAM since evangelical authors are adopting a definition of the kingdom steeped in Protestant liberal conversation to motivate their work. Schreiner (2018, p. 15) writes of previous definitions of the kingdom, “Evangelicals have been prone to reduce the kingdom to God’s rule, power, or sovereignty”. This definition seems to apply to BAM practitioners’ understanding, as well. I cannot definitively say this is the common definition of kingdom to BAM practitioners. In fact, there is one definition found for kingdom (Russell 2010), the rest are descriptions. Therefore, I must deduce definition based on description. Describing the kingdom as extending shalom, flourishing, human dignity, etc. is in line with George Ladd’s “realm” of blessing in the kingdom of God in which people come into God’s reign. Thus, it is acceptable for the purpose of this article to posture the common definition of kingdom in the BAM community as the reign of God (see literature review below). For a BAM practitioner, if the reign of God is a reductionistic definition of the kingdom of God, the question becomes, “What is a robust definition of the kingdom of God?” At this point, Graeme Goldsworthy can provide an answer.

3.1. Kingdom Defined: God’s People in God’s Place under God’s Rule

Graeme Goldsworthy (2012) published The Gospel and the Kingdom in 1981 from a lecture series at Moore Theological College in Sydney, Australia in the 1970s. Goldsworthy taught biblical theology through his methodology in both the academy and parish ministry for the next several years. During this time, he developed another biblical theological resource: According to Plan. Both books are light in references. Therefore, later in his career Goldsworthy placed his academic work within the arena of other scholars such as C.H. Dodd, George Ladd, Donald Robinson, Charles Scobie, Dennis Johnson, and others. In his own words, Donald Robinson, C.H. Dodd, Geerhaus Vos and John Bright were instrumental in shaping his views on an evangelical perspective of biblical theology (2012, p. 78).

For Goldsworthy, biblical theology is finding the unifying thread to the inspired word. It is a discipline, he argues, evangelicals uniquely pursue due to our dedication to the Bible as authoritative. He writes, “The term evangelical is open to different meanings. However, it usually indicates a position that regards the Bible as the reliable and authoritative source of our knowledge of God and his will for us” (2012, p. 76). Goldsworthy’s developments are crucial for a modern understanding of the kingdom since he advanced the discussion on the grounds of the authority and unity of the entire Bible unlike the historical critical analysis sketched above. Goldsworthy states, “This implies that there is an essential unity that centers on Jesus Christ within the diversity of the range of biblical texts. It means that the whole Bible is accepted as God’s word to humanity revealing God’s plan and purpose for the salvation of his people and the establishment of his kingdom” (2012, p. 77). This is important for the BAM practitioner as they can utilize a definition of the kingdom not deduced by historical critical analysis but the biblical narrative.

Goldsworthy (2000) establishes the kingdom as the unifying thread that ties the unity of the Bible together. He sees three basic elements of the kingdom of God: (a) God’s people, (b) in God’s place, (c) under God’s rule. He also employs the “already-not yet” tension that evangelical predecessor’s such as Ladd used to connect the pieces of the story to one definition. For Goldsworthy, the unifying story of the kingdom is (1) the kingdom pattern established with Adam, (2) the kingdom promised to Abraham, (3) the kingdom foreshadowed in David and Solomon, (4) the kingdom at hand in Jesus, and (5) the kingdom consummated at the return of Christ.

Goldsworthy’s definition of God’s kingdom, God’s people in God’s place under God’s rule, can be seen as an early representative of an evangelical definition of kingdom. Bruce Waltke (2001, p. 18) uses a similar definition in the Kingdom of God in Biblical Theology: “A nation consists of a common people, sharing a common land, submissive to a common law, and having a common ruler”. Similarly, Patrick Schreiner (2018, p. 18) defines the kingdom as “the King’s power over the King’s people in the King’s place”. Peter Gentry and Stephen Wellum in their biblical theology work Kingdom through Covenant (Gentry and Wellum 2018, p. 513) footnote Goldsworthy as a seminal figure in defining kingdom. Likewise, Thomas Schreiner’s (2008, p. 41) work New Testament Theology looks to Goldsworthy as an early example of defining kingdom as the unifier of the Bible. One can see a generational effect on defining the kingdom in an evangelical perspective in Graeme Goldsworthy’s work. BAM practitioners can also find a definition of the kingdom defined through an evangelical perspective they have been asking for.

Goldsworthy’s work shows a more robust definition than God’s power or shalom. To be sure, God’s reign is a part of the equation. However, you cannot separate God’s reign from his people (Israel, the church) and his place (Garden, Promised Land, Temple, local church gathering).

3.2. Literature Review of Kingdom of God in BAM

At this point, it will be helpful to review the literature in BAM to show commonalities and differences with Goldsworthy’s definition. The sample size for this review is based on a bibliography produced by businessasmission.com, a leading resource group in the BAM community. Preference was given to works that are research based works, representative of BAM networks for practitioners or works specifically mentioning kingdom. While not exhaustive, this review gives an adequate sense of comparison to Goldsworthy’s definition of the kingdom among BAM.

Rundle and Steffen (2011) use the word kingdom to describe “kingdom professionals,” which is an alternative for missionary in a BAM context without the former’s negative baggage. Kingdom professionals are intentional about Christian witness, and are called to the marketplace for vocation. The authors want to avoid liberal and evangelical extremes of all social action or all spiritual focus (i.e., saving souls) (pp. 38–39). They favor holistic objectives in a Great Commission Company that are described as socially responsible, income producing, glorifying God (ethics and witness), promoting church growth, and focusing on least developed and evangelized places in the world (pp. 46–47). While not formulating a definition for kingdom in the work, Rundle and Steffen seek compatible holistic objectives that a robust kingdom definition also produces.

Johnson (2009) uses the word kingdom to describe kingdom efforts, momentum, strategy, perspective, Kingdom Company, and bottom line. Johnson’s use of kingdom follows an explicit definition of BAM as a for profit company used for God’s mission in the world in a cross cultural environment. Moreover, Johnson mentions that any definition is limiting and therefore inadequate citing an example of a focus group’s conclusion in Lausanne Conference 2004 that there are an infinite variety of connections between business and mission (p. 28). Therefore, it seems that the term kingdom is adopted to welcome the infinite varieties of expression, while narrowing the scope of BAM to holistic ministry in cross cultural settings.

The Lausanne Occasional Paper #59 (Tunehag et al. 2004) on Business as Mission was the summary document from the Lausanne Conference 2004 mentioned above. Johnson’s earlier note on the committee finding endless connections between business and mission is helpful to understand the use of kingdom in the paper. Kingdom is used as a summary word to describe an imaginary for broad mission possibilities in and through business for positive Christian influence that includes evangelism, economic development, values, and justice.

Baer (2006) uses kingdom as a descriptor of the business to intentionally connect to establish the kingdom of Christ in the world (p. 14). Baer differentiates kingdom business with marketplace ministry by adding that a kingdom business will end in a connection to cross cultural engagement or in his words, world missions (p. 14). He also uses kingdom to describe the ethics and values the business should operate. For instance, the kingdom worldview of Jesus leads to a philosophy of servant leadership (p. 111).

Russell (2010) is the one resource in BAM where I can find an explicit definition of kingdom. He says, “The kingdom of God can be most simply defined as God’s reign. So, the kingdom is the manifestation of God’s ideals, principles, values, and will” (p. 47). Russell describes kingdom as tangible rather than intangible and says there is a historical unfolding to the kingdom. Here, he connects the kingdom with the concept in the Old Testament of shalom as a metaphor for holism in the kingdom.

Lai (2015) uses the term kingdom sparingly. He advocates for four bottom lines that a business should pursue. Lai attempts to keep both spiritual and economic goals forefront as the specific call for someone in BAM in holistic ministry. He even goes as far to say that if a business is succeeding in one, but not both, of their objectives in creating wealth and reaching the community, their network recommends closing the business.

Van Duzer (2010, p. 25) defines kingdom as “the place or places God reigns, where God is king”). He refers to Stevens (2006) to help describe four characteristics of the kingdom: Forgiveness of sins, restoration of life, restoring community across boundaries, and denouncing collective/institutional sin. While narrowing the definition of kingdom to reign, Van Duzer recognizes a holistic vision in spiritual healing through forgiveness and physical outworking through societal restoration.

Gort and Tunehag (2018) describe the kingdom as God’s reign. Kingdom work is redemptive as it reaches into the broken systems of our day (p. 12). Similar to Rundle and Steffen earlier, they theorize that evangelicals only minister in the spiritual realm of mission neglecting the holistic understanding (p. 10). They connect BAM to three mandates in Scripture: The Cultural Mandate, the Great Commandment, and the Great Commission. Seeing these as three scriptural priorities, they seek to correct the evangelical “omission” in the Great Commission focus (p. 109).

Adams and Raithatha (2012) view the kingdom as an indescribable reality, one that is understood but hard to communicate. They comment that Jesus’ stories about the kingdom do not define the kingdom, but each parable gives us a flavor of the kingdom. “The kingdom is recognized when it is seen, and missed when it isn’t seen” (loc. 286). Later, the authors give more specifics on the kingdom: It is where the King is recognized, rebels become subjects, and kingdom values are kept (loc. 463). In speaking of a spiritual bottom line, the authors say that keeping Christian values is a minimum requirement and can constitute as a spiritual bottom line since it promotes kingdom values (p. 679).

Stevens (1999, p. 183) defines the kingdom as the rule of God as king plus the response of his subjects as they submit. He draws from biblical scholarship that concludes that the original language of the kingdom of God in Mark refers to the act of kingship rather than a territory or place. He notes that there is an invisible and visible nature of the kingdom. First, the kingdom is in hearts and as God sways human affairs. Second, the church is the kingdom visible as an “outcropping” of the kingdom. He claims the church is not the kingdom in full, but is the agent of the kingdom that is now (p. 184).

Wong and Rae (2011) focus their perspective on the human flourishing side of the kingdom. They trace the mission of God to bring the full meaning of shalom to the kingdom (p. 73). As God’s co-creators, he gives us the mission of junior partners to steward and take dominion of his creation and later kingdom. In so doing, our work will have intrinsic value as it will last in some form or fashion into eternity as part of the new heavens and new earth (p. 74). For kingdom, they clarify that Jesus meant God’s reign and a reversal of the world’s values or ethics (p. 71).

Through this literature review, there are some noticeable commonalities the way BAM authors discuss the term kingdom. First, authors seem to identify as evangelical al-though lament a narrow view of spiritual mission rather than holistic mission opting for kingdom to describe a larger reality. Second, when a definition is postured, authors rely on God’s reign. Third, kingdom is mostly used as an adjective describing the nature of the activity rather than a noun focused on a particular reality (e.g., kingdom professional, kingdom business, kingdom bottom line). Fourth, kingdom is often used as a broad category to enlarge possibilities in either audience or opportunity for the purpose of abolishing the secular-sacred divide.

In comparing the use of kingdom to Goldsworthy’s definition there are three similarities. One, there is a vision for holistic ministry made possible. God’s mission is worldwide in redemptive scope reconciling all things to himself. Two, there is a focus on kingdom ethics and Christian values through God’s reign. Three, conversion is a necessary category for the kingdom. On this point, BAM authors typically spend the majority of their time defending holistic ministry, but it is clear from the review above that authors set a foundation assuming the gospel needs to be proclaimed to people who do not believe yet.

From the review, there is one key separation from Goldsworthy’s definition to the usage among the BAM community: God’s place. BAM authors speak of a sacred-secular divide that permeates Christian thinking. Therefore, they logically conclude, people need to be awakened to ministry outside the church and God’s reign connects the narrative between church and world. However, this is only an institutional vision of the church. In biblical theology, God’s place resides in his people in the New Testament. The Temple is found within the community of believers as they gather and scatter as the Body of Christ. Therefore, Goldsworthy’s definition sets a trajectory of focusing explicitly on church growth as the primary inaugurated location of the kingdom. However, this definition of church must be seen as organic following the trace of God’s people, not organizational following the trace of money or buildings. This nuance will fit well within the BAM community and further authors’ insistence on breaking the sacred-secular divide.

This review demonstrates that BAM advocates are ready for an evangelical definition that promotes holistic ministry. The Goldsworthy definition fits current BAM beliefs that ministry is holistic, and God’s reign is to be introduced to all. However, there is one refining nuance, from a biblical theology standpoint, that defining kingdom sets a trajectory to make God’s reign tangible through the gathering of Christians in communities called local churches. Currently, BAM use of the word kingdom as a catch-all word creates a broad trajectory for intangible, positive Christian influence. When used as a descriptive adjective, the kingdom becomes intangible as it only adds description to another reality and focuses only on the ethics of the kingdom (which was shown earlier as a symptom of a liberal protestant view of the kingdom).

3.3. Summary

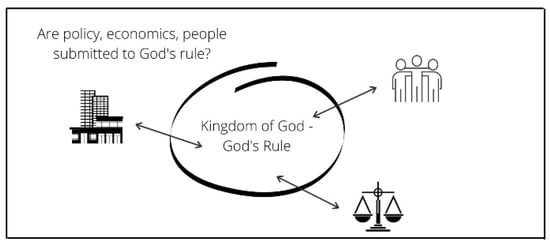

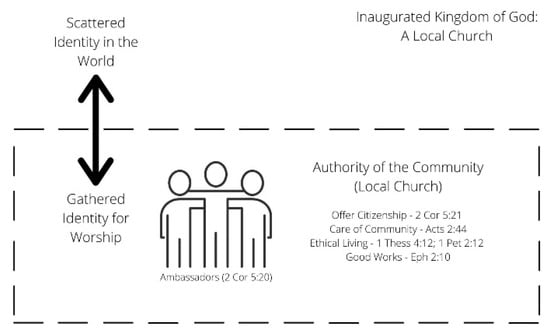

One could rightly ask in summary, “What is the difference between a reduced definition of kingdom simply as God’s rule vs. a robust definition as God’s people in God’s place under God’s rule?” First, in the reduced definition, the expression of the kingdom of God is through ethics—submission to God’s rule. Figure 1 illustrates the focus of a reduced definition as the world relates to God’s rule. In the robust definition, the expression of the kingdom of God is through redemption—a people created for worship and good works. Second, a reduced definition focused on ethics is by nature intangible and less measurable. A robust definition focused on people is tangible and measurable. Figure 2 illustrates the focus of the kingdom through the people of God as they interact within the world. The measures in a people-based approach show creates a reliable way of knowing the business is making progress in their spiritual bottom line (Sheehan 2010).

Figure 1.

Reduced definition of kingdom of God as God’s rule.

Figure 2.

Robust definition as God’s people in God’s place under God’s rule.

3.4. The Church as the Inaugurated Kingdom

Conversations and assertions on the kingdom have focused primarily on God’s rule (Schreiner 2018). However, the church is the only location that Scripture says represents the rule of God after the ascension of Jesus. Moore (2004) expounds, “The resurrection and ascension of Jesus are presented in the New Testament as indeed granting to Jesus the cosmic ruling authority promised to the Son of David (Eph 1:20–21), but this ruling authority is only visible, indeed in one sense only ‘already’ fulfilled, in the context of the regenerate community [local church] of those in voluntary submission to the kingdom of God in Christ (Eph 1:22)” (p. 152). The logic flows that authority in a kingdom rests in the King. If the church is the inaugurated reality of the King (Body of Christ), then the local body is the tangible, true manifestation of the inaugurated kingdom. Therefore, if a BAM organization wants to extend the kingdom of God as an organizational objective, the natural flow would include local church growth as a key, foundational metric.6 Otherwise, the organization is divorcing the concept of the kingdom from the unified biblical narrative of the kingdom in the Scriptures primarily by focusing on some passages over others (e.g., the Creation Mandate). The goal of uplifting churches was a key feature of early BAM writings. A robust definition of kingdom can help BAM organizations laser focus on their spiritual goal, while working for the common good in their community.

One obvious counterargument to this implication of church-focused kingdom objectives will be, “Doesn’t this perpetuate a sacred-secular divide in life?” Narrowing the agency of the kingdom of God in the church actually widens the opportunity for BAM practitioners to work through a holistic paradigm. It seems many authors think of the church as institutional when they think of the existence of the secular-sacred divide. An institutional view of the church would be an organization with leadership of pastors and deacons and members consisting of everyone else promoting the mission of the organization. However, the organic metaphors of the church such as the body of Christ with many members and various gifts (1 Cor 12:12–31) extend a vision of the community of people not the organization. The organic metaphors remind us that the church is composed of people that scatter throughout the week, while keeping the identity as the church or people of God. Therefore, the secular-sacred should not be seen as competing philosophies but correlating spheres that expand and contract with the church gathering for worship on Sunday and scattering through the week still identified as the local church. The emphasis on the people of God will help keep the focus on local church, while continuing to promote the priesthood of believers and abolish the secular-sacred divide.7

Using kingdom language without a clear, robust definition creates a blurred vision of mission where people assume that many business activities fit. However, the blurred definition may produce less creativity. Schreiner reasons that a clearer definition will give freedom to pursue more kingdom objectives. He says, “If the kingdom is merely God’s sovereignty, then what role do his people play? Do they exist only to tell others about the King’s power? The mission of the church is to bring people in union with a real King and into a real kingdom, not just to assent to some immaterial theocracy. Disciples are people who go out and give shape to every space. Jesus brings people into place [the church], and he gives them a law that structures their interactions. If the mission of the church is reduced to an intellectual assent of a sovereign God but does not mold how we use our hands and feet, then the church and the kingdom become a monastery rather than a world-forming force. The kingdom of God is the mission of God, and we must not limit this mission” (Schreiner 2018, pp. 15–16).

Likewise, expanding the definition of kingdom from simply “God’s rule” to more robustly “God’s people in God’s place under God’s rule” expands the opportunity for holistic ministry. This empowers BAM to champion the economic development side of holistic ministry alongside the spiritual component.

A tighter correlation between kingdom objectives and the local church will give more freedom for people to exercise gifts, excellence, dominion, and creativity in other spheres of God’s creation in the name of Jesus through the body of Christ. The organic metaphor of the body of Christ with various gifts increases the ability for every member to serve. This definition of kingdom focused on the people extends the goal of every-member ministry to increase the maturity of the body, the local church, both in quality and quantity (Eph 4:11–13). Another way to say this in a BAM context is to create and measure local church focused kingdom objectives.

4. Implications

What is the importance of defining the kingdom of God for BAM organizations? There are two practical implications that can be suggested from our review. First, a robust definition will help BAM avoid mission drift. Second, it will assist in creating accountable spiritual plans for BAM companies.

4.1. Refine Language to Avoid Mission Drift

Mission drift is when an organization starts with a clear mission and then slowly alters their trajectory over time. Mission drift is inevitable unless leaders of an organization purposefully prevent it (Greer et al. 2015). There is clear evidence that BAM started with a defined holistic purpose to produce economic development and Great Commission impact (Rundle and Steffen 2011; Johnson and Rundle 2006; Johnson 2009; Tunehag et al. 2004; Baer 2006). However, the holistic purpose of BAM is becoming less clear.

Rundle (2003, p. 229) notes that the Creation Mandate and Great Commission are becoming blurred to where verbal witness or spiritual objectives are not explicit is potential among BAM companies. Wealth creation or economic development is specifically becoming more popular as an inherent mission without holistic, explicit mention of discipleship and evangelism (Van Duzer 2010; BAM Global 2017; Grudem 2003). Rundle rightly sees the problem in our fuzziness on how the three mandates (Creation Mandate, Great Commission, and Great Commandment) work together. Rather than blurring the mandates though, the review above shows that we are separating them and treating them as separate goals to build a holistic paradigm. However, if they are separate, the logic flows that it is ok to excel at one without the other. With a robust definition of kingdom that shows the unified narrative from the three mandates, BAM authors can theologize and theorize in a holistic paradigm where it is expected to pursue both sides of holistic ministry.

When considering the potential for mission drift in BAM, a reduced definition of kingdom as God’s rule possesses no guardrails to direct the trajectory of future mission. A person can divorce the mission of God with the gospel of God through good endeavors such as economic development claiming the Creation Mandate. However, when God’s gathered and redeemed people are inherent in the definition of kingdom, then the guardrails are set to keep BAM true to a holistic vision of economic development and Great Commission impact.

4.2. Create a Clear Spiritual Mission Plan

BAM best practices include choosing what their bottom lines will be and drafting a spiritual mission plan on how they will execute the objectives (Johnson 2009, p. 403). However, there is evidence that practitioners skip this step in the BAM planning process and often do not have a clear plan articulating the spiritual bottom line (Bosch 2017). Perhaps, the vague nature of kingdom objectives observed in companies is a symptom of a reduced or vague definition of kingdom as the ultimate goal for BAM? For instance, Adams and Raithatha claim that the kingdom is difficult to communicate, and even suggest that tracking kingdom advancement maybe antithetical to the kingdom (loc. 723). How does one then expect someone to write a clear goal for a spiritual bottom line? This teaching illustrates the logic that if the kingdom is hard to define, it is hard to measure. A robust definition of kingdom that is focused on local churches can provide clarity on what to measure.

Yukl argues that vision needs vivid imagery and exciting language to clearly communicate vision (Yukl 2010, p. 289). The growth of the body of Christ (local churches) provides more vivid imagery than the reduced definition of kingdom in God’s reign for spiritual bottom line vision. Two questions come to mind when measuring God’s reign. First, how does God grow in his reign over creation? How does God’s kingdom grow in this paradigm? It is not truly God’s rule that we are measuring, but the response to God’s rule. Therefore, second, how do you measure ethics without people? One cannot observe love, generosity, faith, prayer or any other kingdom virtue without a person or community demonstrating the ethic. Therefore, at the end of the day, a spiritual bottom line will measure people one way or another. A reduced definition of God’s reign does not adequately teach or train how to measure kingdom goals. However, tying the spiritual bottom line to the growth of a local church through a biblical theological definition of inaugurated kingdom will help make tangible spiritual planning documents measurable. We can observe and report on the tangible, public Christian witness of God’s reign to the community through the church. Then, the company can do the review, audit, and refining step of their spiritual bottom line that is key to effectiveness (Johnson 2009, p. 413).

5. Conclusions

As the conversation of the kingdom rested in the middle on inaugurated eschatology, theologians such as Graeme Goldsworthy developed a robust definition of kingdom as God’s people in God’s place under God’s rule. In biblical theology, the church is seen as possessing the blessings and authority of the inaugurated kingdom in a preparatory role as God’s people in God’s place under God’s rule. Moreover, the church importantly demonstrates the coming kingdom through the anticipation of God’s final consummation. Therefore, the local church is the authoritative agent of the inaugurated kingdom of God in the present.

The review of the historical definition of the kingdom shows that ministry implications occur depending on one’s view of the kingdom. When one views the kingdom as totally present, societal transformation, ethics, and justice are the main concerns. On the other hand, when one views the kingdom as totally future, a withdrawal from engaging the world in areas such as work can result focusing on merely the salvation of the soul. However, the view of inaugurated eschatology promotes a healthy tension of holistic ministry.

This article shows that BAM practitioners can utilize a biblical theological definition of kingdom to relate in tangible ways to a local church in order to promote the kingdom of God. BAM practitioners can unashamedly adopt church growth (qualitative or quantitative) as a primary metric for kingdom growth. The BAM movement started with a holistic vision of economic development and Great Commission impact through churches. While the term kingdom was first used to expand the vision for ways business and mission can intertwine, it is possible that practitioners are not truly connecting holistic ministry and failing to promote the tension of the already, not yet kingdom. The time has come to adopt a clarified definition of kingdom that fits the commonalities in BAM ventures showcased in the literature review to better encourage practitioners to adopt both economic and spiritual bottom lines faithful to the BAM community’s emergence.

A robust definition will help a BAM company with practical implications such as avoiding mission drift. Moreover, the spiritual plan of the company will be measurable as it is tied to people in churches rather than a vague idea of God’s rule. These implications will help clarify the holistic goals of BAM for effectiveness that has been a part of the movement since the very beginning.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | Myers (2011) describes holism as a reaction to the modern worldview’s split between the spiritual and the material. Therefore, holism is a worldview including the whole person both spiritual and material, seen and unseen (see pp. 5–7). |

| 2 | For instance, Michael Humphries (1999) points out that NT scholarship today is still practicing comparative exegesis in a historical critical analysis of the text. Biblical theology that sees unity in the Bible with a divine author leads to different conclusions, not to mention bibliographies. |

| 3 | This historical sketch of representative figures in the history of the conversation concerning the kingdom follows the full summary in The Kingdom of God in 20th Century Interpretation edited by Wendell Willis. My historical sketch will take a detour from the historical critical analysis after Ladd venturing into biblical theology definitions of the kingdom. The historical critical analysis of the conversation could continue through scholars such as NT Wright. |

| 4 | There is a noticeable academic lineage from Ladd to prominent evangelical biblical theologians. Ladd interacted with Geerdahus Vos (see Moore’s The Kingdom of Christ, pp. 30–31), who along with Edmund Clowney, Graeme Goldsworthy interacts with consistently, see Christ Centered Biblical Theology, pp. 78–99. These authors are also influential in the works of more modern works from Bruce Waltke, Stephen Dempster, GK Beale, Patrick Schreiner, Tom Schreiner, Peter Gentry and Stephen Wellum, and Oren Martin. However, as mentioned earlier, liberal-critical scholarship does not interact with these works due to the presupposition in biblical theology in the unity of the bible. Therefore, until recently a definition of the kingdom built on the Bible’s credibility has not been a conversation within grasp. |

| 5 | Tunehag does a great job pointing out the biblical texts to help those who simply reduce all of ministry life to evangelism and discipleship. My point is that biblical theology will help the BAM community not to go towards “mission drift” to exclude evangelism and discipleship, which is unclear in documents such as the Wealth Creation Manifesto (BAM Global 2017). Systematic study separates the three mandates logically which could be used to separate the definition of mission or BAM bottom lines leading to a focus on one of mandates, while biblical theology unifies the narrative which will inherently produce a more holistic vision. |

| 6 | By local church, I mean the reality of a community of believers who commit to one another following the example of the New Testament. The size, shape, and visibility (i.e., underground church) is outside the limitations of this article. However, the BAM community could use further research about the ways in which a local church is expressed in Restricted and Closed Access Nations. |

| 7 | In a separate work, I would tie the dual existence of the people of God as gathered and scattered to a concept in sociology known as salient personalities in identity theory. The idea is that a person does not have a primary identity, but they are a rolodex of personalities that are available for them to use (Hart and Sheldon 2007). A person is a range of parent, employee, volunteer, follower, leader, etc. The goal is not to truncate our personalities, but to become more fluent in the ability to utilize our personalities according to social cues. I believe this train of research could help answer some key questions to the secular-sacred divide. For instance, how does one be a leader in their business yet a follower in their church for the advancement of the kingdom? Or how does one allocate time among kingdom pursuits as well as business and family pursuits? |

References

- Adams, Bridget, and Manoj Raithatha. 2012. Building the Kingdom through Business: A Mission Strategy for the 21st Century. Watford: Instant Apostle. [Google Scholar]

- Albright, Brian, Ming Dong Paul Lee, and Steve Rundle. 2014. Scholars Needed: The Current State of Business as Mission Research. Bamthink.org. Available online: https://www.bamglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/BMTT-IG-BAM-Scholarship-and-Research-Final-Report-May-2014.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- Baer, Michael. 2006. Business as Mission: The Power of Business in the Kingdom of God. Seattle: YWAM Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- BAM Global. 2017. Wealth Creation Manifesto. Available online: https://www.businessasmission.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Wealth-Creation-Manifesto-April-2017.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- Bosch, David. 2017. The Gap Between Best Practices and Actual Practices: A BAM Field Study. Christian Business Academy Review 12. Available online: https://cbfa-cbar.org/index.php/cbar/article/view/446 (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- Braunerhjelm, Pontus, and Urika Stuart Hamilton. 2009. Social Entrepreneurship: A Survey of Current Research. Swedish Entrepreneurship Forum. Available online: https://entreprenorskapsforum.se/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/WP_09.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- Eldred, Kenneth. 2005. God Is at Work: Transforming People and Nations through Business. Ventura: Regal. [Google Scholar]

- Epp, Jay. 1987. Mediating Approaches to the Kingdom: Werner Georg Kümmel and George Eldon Ladd. In The Kingdom of God in 20th Century Interpretation. Wendell Willis Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Ewert, Norm. 2006. God’s Kingdom Purpose for Business: Business as Integral Mission. In Business as Mission: From Impoverished to Empowered. Tom Steffen and Mark Barnett, Evangelical Missiological Society 14. Pasadena: William Carey Library. [Google Scholar]

- Gentry, Peter, and Stephen Wellum. 2018. Kingdom through Covenant: A Biblical Theological Understanding of the Covenants, 2nd ed. Wheaton: Crossway. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsworthy, Graeme. 2000. The Goldsworthy Trilogy: Gospel and Kingdom, Gospel and Wisdom, The Gospel in Revelation. Exeter: Paternoster Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsworthy, Graeme. 2012. Christ-Centered Biblical Theology: Hermeneutical Foundations and Principles. Downers Grove: IVP Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Gort, Gea, and Mats Tunehag. 2018. BAM Global Movement: Business as Mission Concept & Stories. Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Greer, Peter, Chris Horst, and Anna Haggard. 2015. Mission Drift: The Unspoken Crisis Facing Leaders, Charities, and Churches. Grand Rapids: Bethany Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Grudem, Wayne. 2003. How Business Itself Can Glorify God. In On Kingdom Business: Transforming Missions through Entrepreneurial Strategies. Edited by Tetsunao Yamamori and Kenneth A. Eldred. Wheaton: Crossway Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, Anne, and George Sheldon. 2007. Personality Tests Decoded. Franklin Lakes: Career Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hiers, Richard. 1987. Pivotal Reactions to the Eschatological Interpretation: Rudolf Bultmann and C.H. Dodd. In The Kingdom of God in 20th Century Interpretation. Wendell Willis Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Humphries, Michael. 1999. Christian Origins and the Language of the Kingdom of God. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C. Neal, and Steve Rundle. 2006. Distinctives and Challenges of Business as Mission. In Business as Mission—From Impoverished to Empowered. Pasadena: William Carey Library. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C. Neal. 2009. Business as Mission: A Comprehensive Guide to Theory and Practice. Downers Grove: IVP Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd, George Elden. 1968. The Pattern of New Testament Truth. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Patrick. 2015. Business for Transformation: Getting Started. Pasadena: William Carey Library. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Russell. 2004. The Kingdom of Christ: The New Evangelical Perspective. Wheaton: Crossway. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, Bryant. 2011. Walking with the Poor: Principles and Practices of Transformational Development. Maryknoll: Orbis Books. [Google Scholar]

- Rundle, Steve, and Tom Steffen. 2011. Great Commission Companies: The Emerging Role of Business in Missions. Downers Grove: IVP Books. [Google Scholar]

- Rundle, Steve. 2003. Preparing the Next Generation of Kingdom Entrepreneurs. In On Kingdom Business: Transforming Missions through Entrepreneurial Strategies. Edited by Tetsunao Yamamori and Kenneth Eldred. Wheaton: Crossway Books, pp. 225–47. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, Mark. 2010. Missional Entrepreneur. Birmingham: New Hope Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner, Patrick. 2018. The Kingdom of God and the Glory of the Cross. Wheaton: Crossway. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner, Thomas R. 2008. New Testament Theology: Magnifying God in Christ. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, Robert M. 2010. Mission Impact: Breakthrough Strategies for Non-Profits. Hoboken: Wiley and Sons Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, R. Paul. 1999. The Other Six Days: Vocation, Work, and Ministry in Biblical Perspective. Grand Rapids: W. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, R. Paul. 2006. Doing God’s Business: Meaning and Motivation in the Marketplace. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Tunehag, Mats, Wayne McGee, and Josie Plummer. 2004. Lausanne Occasional Paper #59: Business as Mission. Lausanne Committee on World Evangelization. Available online: https://www.lausanne.org/wp-content/uploads/2007/06/LOP59_IG30.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- Van Duzer, Jeffrey. 2010. Why Business Matters to God: And What Still Needs to Be Fixed. Downers Grove: IVP Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Waltke, Bruce. 2001. The Kingdom of God in Biblical Theology. In Looking into the Future: Evangelical Studies in Eschatology. Edited by David Baker. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, Wendell. 1987. The Discovery of the Eschatological Kingdom: Johannes Weiss and Albert Schweitzer. In The Kingdom of God in 20th Century Interpretation. Wendell Willis Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Kenman L., and Scott B. Rae. 2011. Business for the Common Good: A Christian Vision for the Marketplace. Downers Grove: IVP Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Yukl, Gary A. 2010. Leadership in Organizations. Germany: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).