Kazimir Malevich’s Negative Theology and Mystical Suprematism

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. “The World as an Unencompassable Whole”: The Apophatism of Kazimir Malevich

- I am looking for God for myself in myself

- God all-seing all-knowing all-powerful

- the future perfection of the intuition of the universal

- global supermind

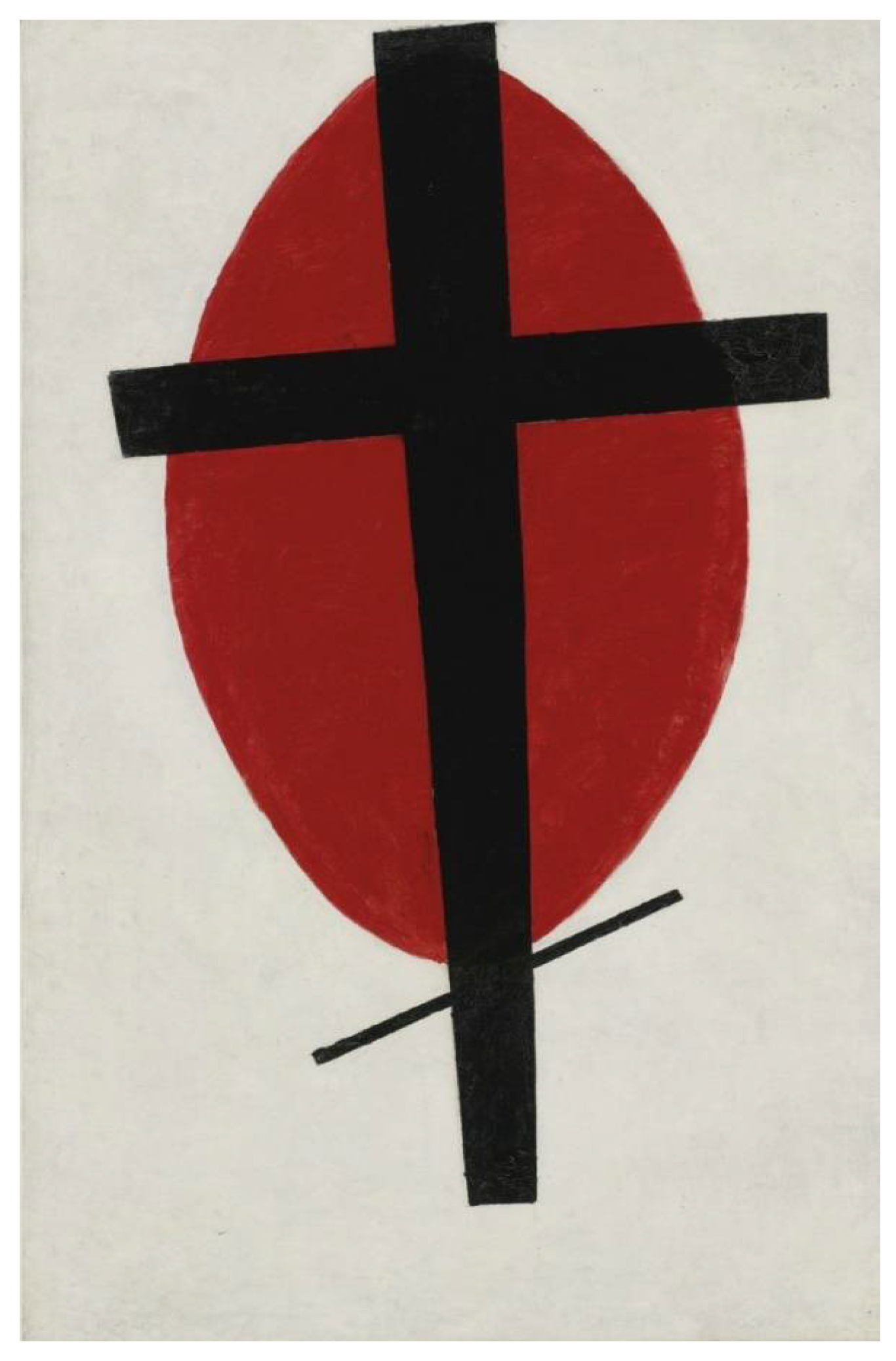

3. Sacred Mysteries of Suprematist Primary Forms: The Square, Circle and Cross

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | It must be added that elements of apophatic thought can be found in Plato’s Socratic dialogue “Parmenides”. The dialogue reproduces a talk between 65-year-old Parmenides, 40-year-old Zeno, Socrates who was 20 at the time, and Aristotle, then just a youth at the Great Panathenaea in 450 BCE. In the first hypothesis, the philosopher talks of the abstract and universal Unity which is “unlimited, if it has neither beginning nor end” (Plato 1997, p. 137d). In the dialogue between Parmenides and Aristotle we can easily discern the main tenet of negative theology: the via negativa as a means of postulating the Unity, “[P]: So neither name nor account belongs to it, nor is there any knowledge or perception or opinion of it. [A]: It appears not. [P]: So it is neither named nor spoken of, nor willit be an object of opinion or knowledge, nor does anything among things which are perceive it”. (Plato 1997, p. 142a) For more details, see (Dodds 1928; Rist 1962). |

| 2 | Theologians and scholars of religion are still debating the origin of the corpus of texts published under the name of Dionysius the Areopagite (including the Divine Names, Mystical Theology, Celestial Hierarchy, Ecclesiastical Hierarchy and Ten Epistles) and its dating. Some think they are 5th century forgeries, while others guess their putative real authors, such as Severus of Antioch, Dionysius the Great, Ammonius Saccas, Peter the Iberian, or John Philoponus. For more on this, see (Koch 1900; Stiglmayer 1928; Devreesse 1930; Puech 1930; Nutsubidze 1942; Honigmann 1952; Golitsin and Bucur 2013; Kharlamov 2016). |

| 3 | One of the first to address this issue was Galina Belaya in a small article titled “Avangard kak Bogoborchestvo” [Avant-garde as creating God] (Belaya 1992). |

| 4 | I. Klyun made an interesting point in his brochure “Tainye poroki akademikov” [Secret sins of academic artists]: “A huge challenge arose in its full might—to create form out of Nothing”. See (Kruchenykh et al. 1916, p. 29). |

| 5 | |

| 6 | It must be noted that, although Malevich has been the subject of numerous monographs and articles, his apophatic thought mostly stays under the radar in Russian scholarship. The reason for this goes beyond the difficulty of comprehending his vast philosophical and theoretical heritage: the very problem is quite provocative. For a long time, the art of the avant-garde has been studied in Russia solely in the context of theomachy and social utopianism. The issues of negative theology and Suprematism have been treated, albeit cursorily, in (Bychkov 1998; Mikhailova 2000; Shatskikh 2000; Levkova-Lamm 2004; Kurbanovsky 2007; Lozovaia 2011; Rostova 2021). |

| 7 | Miroslava Mudrak has noted a significant influence of Byzantine liturgy and Christian tradition of icon painting on Malevich’s early Symbolist frescoes. She also described a synthesis of Oriental and European iconographical motives in his art. See Mudrak, Miroslava. 2016. Kazimir Malevich i vizantiiskaia liturgicheskaia traditsiia [Kazimir Malevich and the Byzantine liturgical tradition]. Iskusstvo, № 2 (597). pp. 50–67. |

| 8 | See (Voronina and Rustamova 2015). |

| 9 | On the dating of Malevich’s Black Square, see (Goryacheva 2020). |

| 10 | This might be a reference to Robert Fludd’s “Utriusque cosmi maioris scilicet et minoris Metaphysica, physica atque technica Historia” (1617). Fludd, a mystic and astrologer, saw the black square as a symbol of the darkness of the Universe—a macrocosm where eternal Darkness reigns supreme. |

| 11 | It must be noted that the articles and treatises by Malevich devoted directly to the Black Circle have not yet been discovered. Tatyana Goryacheva has suggested that in his Vitebsk years, Malevich wrote an article titled Solntse i Cherny Kvadrat [The Sun and the Black Square], or, according to a different source, Beloe Solntse i Cherny Kvadrat [The White Sun and the Black Square], but no manuscript of it is currently known. See (Goryacheva 2020, p. 27). |

| 12 | |

| 13 | The Black Circle (1915) is now part of the collections of the State Russian Museum in St. Petersburg. It went on display together with the Black Cross and Black Square at the 0.10 exhibition. |

| 14 | Mandorla (Italian for “almond”), or “vesica piscis” (Latin for “swim bladder”)—a symbolic depiction of oval-shaped shining, or an almond-shaped halo around the body of the Savior, which appears on the icons of Transfiguration and Ascension. |

References

- Ampilova, Anna. 2009. Suprematizm i ikonopis’: k probleme formy i soderzhaniia v izobrazitel’nom iskusstve nachala XX veka [Suprematism and Icon Painting: On form and Content in Pictorial Art of Early 20th Centiry]. № 4. Moscow: Prepodavatel’ XX vek, MPGU, pp. 370–74. [Google Scholar]

- Andreeva, Ekaterina. 2019. Kazimir Malevich. «Chernyi kvadrat» [Kazimir Malevich: The Black Square]. St. Petersburg: Arka. [Google Scholar]

- Belaya, Galina. 1992. Avangard kak bogoborchestvo [The Avant-Garde as Theomachy]. № 3. Moscow: Voprosy literatury, pp. 115–24. [Google Scholar]

- Berdyaev, Nikolai. 1955. Kommunizm i khristianstvo [Communism and Christianity]. In Istoki i smysl russkogo kommunizma [The Origins of Russian Communism]. Paris: YMCA-PRESS. [Google Scholar]

- Berdyaev, Nikolai. 1990. Krizis iskusstva [The Crisis of Art: A Reprint Editon]. Moscow: SP Interprint. [Google Scholar]

- Bering, Kunibert. 1986. Suprematismus und Orthodoxie. Einflüsse der Ikonen auf das Werk Kazimir Malevics. No. 2/3. Minneapolis: Ostkristliche Kunst, Fortress Press, pp. 143–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlt, John. 1991. Othodoxy and the Avant-Garde. Sacred Images in the Work of Goncharova, Malevich and Thier Contemporaries. Christianity and the Arts in Russia. Edited by M. Velimirovic and W. Brumfield. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bulgakov, Sergii. 1994. Svet nevechernii: Sozertsaniia i umozreniia [Unfading Light: Contemplations and Speculations]. Mysliteli XX veka [20th Century Thinkers]. Moscow: Respublika. [Google Scholar]

- Bychkov, Victor. 1998. Ikona i russkii avangard nachala XX veka [The icon and the Russian avant-garde in early 20th century]. In KorneviShche OB. Kniga Neklassicheskoi Estetiki. Moscow: IF RAN, pp. 58–75. [Google Scholar]

- Devreesse, Robert. 1930. Denys l’Aréopagite et Severe d’Antioche. Archives d’histoire doctrinale et littéraire du moyen âge. Paris: Librairie Philosophique J. Vrin. [Google Scholar]

- Dionysius, Pseudo. 1987. The Complete Works. New York: Paulist Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, Eric. 1928. The Parmenides of Plato and the Origin of the Neoplatonic ‘One’. Classical Quarterly, No. 22. Cambeidge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 129–42. [Google Scholar]

- Epshtein, Mikhail. 2013. Russkaia kul’tura na rasput’e. Sekuliarizatsiia i perekhod ot dvoichnoi modeli k troichnoi [Russian culture at the crossroads. Secularisation and the tranfer from the dual to the ternary model]. In Religiia Posle Ateizma. Novye Vozmozhnosti Teologii [Religion after Atheism: New Opportunities for Theology]. Moscow: AST Press, pp. 159–222. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, Charlotte. 2016. A “Direct Perception of Life”. How the Russian Avant-Garde Utilized the Icon Tradition. IKON 9: 323–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golitzin, Alexander, and Bogdan G. Bucur. 2013. Mystagogy: A Monastic Reading of Dionysius Areopagita. Collegeville: Liturgical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goryacheva, Tat’iana. 1993. Malevich i Renessans [Malevich and the Renaissance]. Voprosy Iskusstvoznaniia 2–3: 107–18. [Google Scholar]

- Goryacheva, Tat’iana. 2020. Pochti vse o «Chernom kvadrate» [Almost everything about the Black Square]. In Teoriia i Praktika Russkogo Avangarda: Kazimir Malevich i ego Shkola [Theory and Practice of the Russian Avant-Garde: Kazimir Malevich and his School]. Edited by T. V. Goryacheva. Moscow: AST. [Google Scholar]

- Hadot, Pierre. 2005. Apofatizm, ili Negativnaia teologiia [Apophatism, or Negative Theology]. In Dukhovnye uprazhnenia i antichnaia filosofia [Spiritual/Per. s frants. pri uchastii V.A. Vorob’eva. Moscow]. St. Petersburg: Stepnoi Veter, pp. 215–26. [Google Scholar]

- Holy, Bible. 2010. Paul´s First Letter to Timothy, The Epistle of James. King James Bible: 400 th Anniversary Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Honigmann, Ernest. 1952. Pierre l’Iberian et les écrits du Pseudo-Denys l’Aréopagite. (Classe des leres et des scien-ces morales et politiques. Mémoires, 47, fasc. 3). Bruxelles: Con Académie royale de Belgique. [Google Scholar]

- Ichin, Cornelia. 2011. Suprematicheskie Razmyshleniia Malevicha o Predmetnom Mire [Malevich’s Suprematist Reflections on the World of Objects]. № 10. Moscow: Voprosy filosofii, Izdatel'stvo Nauka, pp. 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kern, Archimadrid Kiprian Кonstantin. 1996. Antropologiia sv. Grigoriia Palamy. [The Anthropology of St. Gregory Palamas]. Introduction Article by A. I. Sidorov. Moscow: Palomnik. [Google Scholar]

- Kharlamov, Vladimir. 2016. Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite and Eastern Orthodoxy: Acceptance of the Corpus Dionysiacum and Integration of Neoplatonism into Christian Theology. Theological Reflections. № 16. Euro-Asian Journal of Theology 2016: 138–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koch, Hugo. 1900. Pseudo-Dionisius Areopagita in seinen Beziehungen zum Neoplatonismus und Misterienwesen. Forschungen zur christlichen Litteratur und Dogmengeschichte. 1 Bd., t. 86, 2-3 Heft. Mainz: Verl. von Franz Kirchheim. [Google Scholar]

- Kovtun, Yevgeniy Fedorovich. 1990. Nachalo suprematizma [The Rise of Suprematism]. Malevich khudozhnik i teoretik. Moscow: Sovetskii khudozhnik. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, Verena. 1998. Von Der Ikone Zur Utopie: Kunstkonzepte der Russischen Avantgarde. Köln: Böhlau. [Google Scholar]

- Kruchenykh, Alexey, Ivan Klyun, and Kazimir Malevich. 1916. Tainye poroki akademikov [Secret Sins of Academic Artists]. igns: From Iconoclasm to New Theolo. Moscow: Budetlian. [Google Scholar]

- Krusanov, Andrei Vasilievich. 1996. Russkii avangard: 1907–1932. (Istoricheskii obzor) [The Russian avant-garde: 1907–1932: A historical survey]. In Boevoe desiatiletie [The Decade of Battles]. St. Petersburg: Novoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie, 3 vol., vol. I. [Google Scholar]

- Kurbanovsky, Aleksey. 2007. A. Malevich’s Mystic Signs: From Iconoclasm to New Theology. Sacred Stories: Religion and Spirituality in Modern Russia. Edited by Mark D. Steinberg and Heather J. Coleman. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levina, Tatiana. 2015. Ontologicheskii argument Malevicha: Bog kak sovershenstvo, ili vechnyi pokoi [Malevich’s ontological argument: God as perfection, or the eternal rest]. Artikul’t 19: 18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Levkova-Lamm, Inessa. 2004. Litso kvadrata: Misterii Kazimira Malevicha. [The Face of the Square: The Mysteries of Kazimir Malevich]. Moscow: Pinakoteka. [Google Scholar]

- Lissitzky, El. 2003. Suprematizm mirostroitel’stva [The Suprematism of World-Building]. In Al’manakh Unovis. [Almanach UNOVIS]. A Facsimile Edition. Preparation, Introduction and Comments by T. Goryacheva. Moscow: SkanRus. [Google Scholar]

- Lossky, Vladimir Nikolayevich. 2006. Bogovidenie [The Vision of God]. Translated by V. A. Reshchikova. Comp. and Introd. by A. S. Filonenko. Moscow: AST. [Google Scholar]

- Lozovaia, Lidia. 2011. Bogoslovskie aspekty russkogo avangarda: Kazimir Malevich i Vladimir Sterligov [Theological Aspects of the Russian Avant-Garde: Kazimir Malevich and Vladimir Sterligov]. No 950. Karazina: Koinoniia/Vestnik KhNU im. V. N, pp. 333–49. [Google Scholar]

- Malevich, Kazimir. 1995a. Suprematizm. “Iz kataloga desiatoi gosudarstvennoi vystavki bespredmetnoe tvorchestvo i suprematizm” [Suprematism. “From the catalogue of the 10th state exhibition “Non-objective art and Suprematism]. In Stat’i, manifesty, teoreticheskie sochineniia i drugie raboty. 1913–1929 [Articles, Manifestos, Theoretical Works and Other Texts, 1913–1929]. Moscow: Gileia. [Google Scholar]

- Malevich, Kazimir. 1995b. Ya prishel [I have come]. In Stat’i, manifesty, teoreticheskie sochineniia i drugie raboty. 1913–1929 [Articles, Manifestos, Theoretical Works and Other Texts, 1913–1929]. Moscow: Gileia. [Google Scholar]

- Malevich, Kazimir. 1995c. Ot kubizma i futurizma k suprematizmu [From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematis]. In Stat’i, Manifesty, Teoreticheskie Sochineniia i Drugie Raboty. 1913–1929 [Articles, Manifestos, Theoretical Works and Other Texts, 1913–1929]. Moscow: Gileia. [Google Scholar]

- Malevich, Kazimir. 1995d. Suprematicheskoe zerkalo [The Suprematist mirror]. In Stat’i, Manifesty, Teoreticheskie Sochineniia i Drugie Raboty. 1913–1929 [Articles, Manifestos, Theoretical Works and Other Texts, 1913–1929]. Moscow: Gileia. [Google Scholar]

- Malevich, Kazimir. 1995e. Bog ne skinut. Iskusstvo, tserkov’, fabrika [God has not been toppled: Art, Church and Factory]. In Stat’i, Manifesty, Teoreticheskie Sochineniia i Drugie Raboty. 1913–1929 [Articles, Manifestos, Theoretical Works and Other Texts, 1913–1929]. Moscow: Gileia. [Google Scholar]

- Malevich, Kazimir. 1995f. O poezii [On poetry]. In Stat’i, Manifesty, Teoreticheskie Sochineniia i Drugie Raboty. 1913–1929 [Articles, Manifestos, Theoretical Works and Other Texts, 1913–1929]. Moscow: Gileia. [Google Scholar]

- Malevich, Kazimir. 1995g. O novykh sistemakh v iskusstve [On new artistic systems]. In Stat’i, Manifesty, Teoreticheskie Sochineniia i Drugie Raboty. 1913–1929 [Articles, Manifestos, Theoretical Works and Other Texts, 1913–1929]. Moscow: Gileia. [Google Scholar]

- Malevich, Kazimir. 1995h. Suprematizm. 34 risunka [Suprematism in 34 drawings]. In Stat’i, Manifesty, Teoreticheskie Sochineniia i Drugie Raboty. 1913–1929 [Articles, Manifestos, Theoretical Works and Other Texts, 1913–1929]. Moscow: Gileia. [Google Scholar]

- Malevich, Kazimir. 1998a. «Nashe vremia iavliaetsia epokhoi analiza» ["Our time is the era of analysis"]. In Stat’i i Teoreticheskie Sochineniia, Opublikovannye v Germanii, Pol’she i na Ukraine. 1924–1930 [Articles and Theoretical Works Published in Germany, Poland and Ukraine]. Moscow: Gileia. [Google Scholar]

- Malevich, Kazimir. 1998b. Mir kak bespredmetnost’ (Fragmenty) [The World as Objectlessness (Fragments)]. In Stat’i i Teoreticheskie Sochineniia, Opublikovannye v Germanii, Pol’she i na Ukraine. 1924–1930 [Articles and Theoretical Works Published in Germany, Poland and Ukraine]. Moscow: Gileia. [Google Scholar]

- Malevich, Kazimir. 2000. Suprematizm. Mir kak bespredmetnost’, ili Vechnyi pokoi: s prilozheniem pisem K. S. Malevicha k M. O. Gershenzonu (1918–1924) [Suprematism. The World as Objectlessness, or the Eternal Rest; with an Appendix of Letters from K.S. Malevich to M.O. Gershenzon (1918–1924)]. Moscow: Gileia. [Google Scholar]

- Malevich, Kazimir. 2004a. «Ia nachalo vsego» ["I am the beginning of everything"]. In Proizvedeniia Raznykh Let: Stat’i. Traktaty. Manifesty i Deklaratsii. Proekty. Lektsii. Zapisi i zametki. Poeziia [Works of Various Years: Articles, Treatises, Manifestos, Declarations, Projects, Lectures, Notes and Records. Poetry]. Moscow: Gileia. [Google Scholar]

- Malevich, Kazimir. 2004b. Zametka o tserkvi [A note on the Church]. In Proizvedeniia Raznykh let: Stat’i. Traktaty. Manifesty i Deklaratsii. Proekty. Lektsii. Zapisi i Zametki. Poeziia [Works of Various Years: Articles, Treatises, Manifestos, Declarations, Projects, Lectures, Notes and Records. Poetry]. Moscow: Gileia. [Google Scholar]

- Malevich on himself (Malevich o sebe). 2004. Sovremenniki o Maleviche: pis’ma, dokumenty, vospominaniia, kritika [Contemporaries on Malevich: Letters, Documents, Memoirs, Criticism]. Moscow: RA (OAO Tip. Novosti). [Google Scholar]

- Marcadet, Jean Claude. 2000. Malevich i Pravoslavnaia Ikonografia [Malevich and Orthodox Iconography]. Moscow: Yazyki knizhnoi kul’tury, pp. 167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Mikhailova, Maria. 2000. Apofatika v Postmodernizme [The Apophatic Thought in Post-Modernism]. St. Petersburg: Eidos, pp. 166–79. [Google Scholar]

- Milner, John. 1996. Kazimir Malevich and the Art of Geometry. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mudrak, Miroslava. 2016. Kazimir Malevich i Vizantiiskaia Liturgicheskaia Traditsiia [Kazimir Malevich and the Byzantine Liturgical Tradition]. Iskusstvo, № 2 (597). Moscow: Alya Tesis, pp. 50–67. [Google Scholar]

- Nakov, Andrei. 2010. Malevich: Painting the Absolute. Burlington: Lund Humphries. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas of Cusa. 1979. Ob uchenom neznanii (De docta ignorantia) [On Learned Ignorance (De docta ignorantia)]. In Filosofskoye Nasledie [The Philosophical Heritage Series]. Moscow: Mysl’. [Google Scholar]

- Nutsubudze, Shalva. 1942. Taina Psevdo-Dionisiya Areopagita [The Mystery of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite]. Tbilisi. Tbilisi: Academy of Sciences of the Georgian SSR. [Google Scholar]

- Plato. 1997. The Dialogues of Plato. Parmenides: Yale University Press, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Puech, Henri-Charles. 1930. Liberatus de Carthage et la Date de L’apparition des Écrits Dionysiens. Annales de l’École des Hautes Études, section des sciences religieuses. Paris: Gand, L’Ecole. [Google Scholar]

- Rist, John. 1962. The Neoplatonic «One» and Plato’s Parmenides//Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, vol. 93, pp. 389–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rostova, Natalia. 2021. Religioznaia taina «Chernogo kvadrata» [The religious mystery of The Black Square]. In Filosofia Russkogo Avangarda: Kollektivnaia Monografia [The Philosophy of the Russian Avant-Garde: A Collective Monograph]. Moscow: RG-Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sarabyanov, Dimitri Vladimirovich. 1993. Russkii Avangard Pered Litsom Religiozno-Filosofskoi Mysli [Russian Avant-Garde and the Religious-Phil Dimitri Vladimirovich Osophic Thought]. Iskusstvo Avangarda: Materialy Mezhdunarodnoi Konferentsii. Aleksei Stukalov: Ufa, pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sarabyanov, Dimitri Vladimirovich. 1998. Kandinskii i russkaia ikona [Kandinski and the Russian icon]. In Mnogogrannyi mir Kandinskogo [Kandinski’s Multifaceted World]. Moscow: Nauka, pp. 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Sarabyanov, Dimitri, and Alexandra Shatskikh. 1993. Kazimir Malevich: Zhivopis’. Teoriia. [Kazimir Malevich: Art and Theory]. Moscow: Iskusstvo. [Google Scholar]

- Schreier, Lotar. 1966. Die Ikone Wassily Kandinsky. In Errinerungen an Sturm und Bauhaus. Edited by L. Schreier. München: Langen Müller, pp. 72–85. [Google Scholar]

- Shatskikh, Alexandra. 2000. Malevich posle zhivopisi [Malevich after painting]. In Suprematizm. Mir kak Bespredmetnost’, ili Vechnyi Pokoi: s Prilozheniem Pisem K. S. Malevicha k M. O. Gershenzonu (1918–1924) [Suprematism. The World as Objectlessness, or the Eternal Rest; with an Appendix of Letters from K.S. Malevich to M.O. Gershenzon (1918–1924)]. Moscow: Gileia. [Google Scholar]

- Spira, Andrew. 2008. Avant-Garde Icon. Russian Avant-Garde Art and the Icon Painting Tradition. Aldershot and Burlington: Lund Humphries. [Google Scholar]

- St. Gregory Palamas. 2009. Polemika s Akindinom [Gregorii Acindyni refu Tationes Duae Operis Gregorii Palamae]. Series: Smaragdos Philocalias; Holy Mt. Athos: The New Thebais Monastery. [Google Scholar]

- St. John of Damascus. 2010. Writings. The Fathers of the Church Series; Washington: CUA Press, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, vol. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglmayer, Joseph. 1928. Der Sogenannte Dionysius Areopagita und Severus von Antiochien. Moscow: Scholastic, III, Freiburg, pp. 1–27, 161–89. [Google Scholar]

- Strigalev, Anatoliy. 1989. «Krest’ianskoe», «Gorodskoe» i «Vselenskoe» u Malevicha [The «Peasant», «City» and «Universal» in Malevich]. № 4. Moscow: Tvorchestvo, Moscow Uchpedgiz, pp. 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tarasov, Oleg. 1992. Ikona v Russkom Avangarde 1910–1920-kh Godov [The Icon in the Russian Avant-Garde of the 1910s and 1920s]. № 1. Moscow: Iskusstvo, Alya Tesis, pp. 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Tarasov, Oleg. 2002. Icon and Devotion. Sacred Spaces in Imperial Russia. Translated and Edited by Robin Milner-Gulland. London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Tarasov, Oleg. 2011. Framing Russian Art. from Early Icons to Malevich. Translated by R. Milner-Gulland, and A. Wood. London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Tarasov, Oleg. 2017. Spirituality and the Semiotics of Russian Culture: From the Icon to Avant-Garde Art. Modernism and the Spiritual in Russian Art. New Perspectives. Edited by Louse Hardiman and Nicola Kozicharow. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, pp. 115–29. [Google Scholar]

- Vakar, Irina. 2015. Kazimir Malevich. “Chernyi kvadrat”. [Kazimir Malevich: The Black Square]. Moscow: Gos. Tret’iakovskaia galereia. [Google Scholar]

- Voronina, Elena, and Iina Rustamova. 2015. Rezul’taty tekhnologicheskogo issledovaniia «Chernogo suprematicheskogo kvadrata» K.S. Malevicha (prilozhenie) [The outcomes of a technological study of the Black Suprematist Square by K.S. Malevich: An appendix]. In Vakar I. Kazimir Malevich. Chernyi kvadrat [Kazimir Malevich: The Black Square]. Moscow: Gos. Tret’iakovskaia galereia. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sakhno, I. Kazimir Malevich’s Negative Theology and Mystical Suprematism. Religions 2021, 12, 542. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12070542

Sakhno I. Kazimir Malevich’s Negative Theology and Mystical Suprematism. Religions. 2021; 12(7):542. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12070542

Chicago/Turabian StyleSakhno, Irina. 2021. "Kazimir Malevich’s Negative Theology and Mystical Suprematism" Religions 12, no. 7: 542. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12070542

APA StyleSakhno, I. (2021). Kazimir Malevich’s Negative Theology and Mystical Suprematism. Religions, 12(7), 542. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12070542