1. Introduction

The religious ceremony of “Huan Jia Yuan (HJY 還家願),”

1 also known as “Zuo Tang (做堂)” in the local dialect, involves seeking reciprocal favors from Panwang (or King Pan, 盤王). It is a ceremony carried out by Yao families, which involves ritual sacrifice. As they offer sacrifices to Panwang, their ancestors, and other gods, the Yao people pray for protection and an end to disasters. The practice of Huan Jia Yuan originated among the Yao people’s ancestors, who used to offer sacrifices to Panwang, who is considered the originator of the Yao people. Fan Chengda’s

Gui Hai Yu Heng Zhi (桂海虞衡志), dating from the Song dynasty, records that “at the beginning of each year,” the Yao people “worship Panwang, put fish, pork, liquor, and rice in a wooden groove, knock on the groove and shout together as a form of worship” (岁首,祭盘瓠杂糅鱼肉酒饭于木槽,扣槽群号为礼) (

Fan 2002).

King Ping’s Chapter (评皇券牒), which was collected in Qishutian, Chengbu County, Hunan Province, states that the Yao reciprocate the favors from Panwang: “The believers paint the gods in the shape of human beings to worship them” (描成人貌之容,画出鬼神之像,应(广)受子女祭祀) (

Guoshanbang 2016). The tradition of offering sacrifices to Panwang has a long history, which can be traced back to the Wei and Jin Dynasties (from 220 to 420 A.D.) (

Zhang 2010). To this day, the Huan Jia Yuan ritual is still observed frequently in Yao villages.

Until now, the academic research on Huan Jia Yuan has mostly focused on the nature, function, and structure of the ritual. The HJY ritual of the Yao people is closely related to Taoism, except that certain ethnic features enrich the ritual process. Scholars have examined the characteristics of the ritual and explored the relationship between Huan Jia Yuan and Taoism. Feng Zhiming (

Feng 2018), for example, has argued that the Yao ritual is a kind of human oath based on a model of reciprocity that combines the beliefs of Taoism and Meishanism with the traditions of ancestral worship. He noted that the practice embodies the cosmology and cognitive system of the Yao people, while also helping to maintain social order, alleviate emotional anxiety, and satisfy people’s spiritual needs. Zhao Shufeng analyzed the intertextuality of Huan Jia Yuan by focusing on the composition of the music and the text of the ritual. He pointed out that the first half of Huan Jia Yuan is a Taoist ceremony, whereas the second half is a sacrificial ritual for Panwang (

Zhao 2010). This reflects the traditional belief system of the Yao but also suggests that it absorbs and transforms some elements of Han culture. Xu Zuxiang (

Xu 2001) demonstrated that Huan Pangwang Yuan cooperated with Taoist rites, which developed into repayment rites. When worshipping Panwang, the Taoist gods are worshipped along with other supernatural powers. Li Yan and Liu Mi studied how the paper offerings made as part of Huan Jia Yuan have changed. They argued that Yao Huan Jia Yuan is composed of “gratitude for the sacred (xie sheng),” which is mainly connected to Taoist gods, and “gratitude for the king (xie wang),” which is mainly connected to Panwang (

Li and Liu 2020). This shows how the Yao ceremony has absorbed elements of the Taoist ceremony.

A series of studies have identified that Yao HJY is closely related to the Taoist repayment ritual. Indeed, there is a long history of Taoist repayment rituals and repayment rituals from ethnic groups in Southwest China influenced by Taoism. These include the “Kai Da Jing” (開大經) ritual of the Han people in YuxiYunan Province, the “Huan Fu” (還福) ritual of the She ethnic group, and the “Huan Tianwang Yuan”(還天王願) ritual of Miao. Those rituals are very similar to Yao HJY in that they stress the relationship and communion between humans and gods. However, there are some differences in the relationships in different regions. Lan divides repayment rituals into two sorts according to their purposes: one concentrates on “returning the favor from gods”; the other is more concerned with “asking for favors before granted” (

Lan 2016). Lan posits that the “Huan Fu” ritual of the She places more emphasis on expressing gratitude to the gods, which is the same as returning the favors of the gods, a true process of exchanging gifts. The “Kai Da Jing” ritual aims at receiving favors, as in humans receiving favors from gods, benefits being shared between participants, hosts receiving favors from masters, and various individuals repaying favors from gods (

Gu and Zhang 2014). The canon

Ling Bao Huan Tianwang Yuan Ke (靈寶還天王願科) records that “Huan Tianwang Yuan” bears a dual-function of returning favor and asking for protection (

Guo 2021). All these purposes of the repayment rituals are represented through different patterns. Therefore, we believe that there is a mutual cultural logic or some religious thoughts that are connected with repayment rituals, which make the communion between humans and gods possible.

To explore human–divine communion and giftexchange, Mauss proposed the theory of the "gift-exchange", arguing that gift-exchange is a holistic phenomenon that helps maintain collective and individual relations (

Mauss 2002). In another book with Hubert, Mauss posits that sacrifices are a significant way for humans to connect with gods; they argue that sacrifices have an important social function (

Mauss and Hubert 2007). Mauss focuses on the meaning of sacrifice and the connotation of sacrificial offerings. He points out that the communion involved in all kinds of sacrificial rites is meant to create a means for the gods and secular beings to communicate (

Mauss and Hubert 2007). This interaction between humans and gods is a key focus of the current study. Bell has classified the model of communication between human and gods. In her opinion, devotional offerings to the deity create a positive human–divine relationship that benefits the devotee spiritually and substantively (

Bell 1997). Bell also found that human–divine interactions involve the language of banking, bureaucratic hierarchy, and closed energy systems. They enable human beings to influence the cosmos by extending the meaning and efficacy of the activities that seem to organize the human world most effectively in China. From this perspective, the gift and information exchange between humans and gods would not only have a positive social function but would also reflect religious thoughts and sociocultural rules. There is no type of ritual that encompasses every individual ritual. Rather, there is a thick context of social customs, historical practices, and day-to-day routines that, in addition to the unique factors at work in any given moment in time and space, influence how and whether a ritual action is performed (

Bell 1997).

The complexity of sacrificial ceremony has also been identified. Each sacrificial ceremony is conducted under certain conditions, with certain specific purposes and functions (

Mauss and Hubert 2007). The complexity of rituals makes it more difficult to explore the structure and logic of HJY. Fortunately, Silva’s research on similarity in ritual classification has inspired us to deal with complicated rituals like this one (

Silva 2013). Silva concludes that there are no pure affliction rituals, nor pure divination rituals, nor pure object animation rituals that mirror their concepts. The thematic threads of ritual speak to modes of life as well as the various contexts and circumstances in which people plan and perform them. Therefore, the structure and social functions of HJY should be presented and analyzed under the specific context of Yao culture.

Chinese scholars have also made important discoveries concerning repayment rituals. Chu Jianfang (

Chu 2005) has demonstrated that the “Bai” ritual in Dai society is a sacrificial rite, which focuses on communication between humans and Buddha. The communication happens in a hierarchical structure and is a mutually beneficial activity that helps different members of the hierarchy to get what they need.

Li (

2016) has also analyzed the motives for sacrifices in Yao society by investigating the symbolism, social function, and change of social relationships involved in the practice of slaughtering pigs for ancestors. Li concludes that in different Yao villages across different regions, there are differences in the form, structure, and frequency of sacrificial rituals. These differences are not merely due to cultural affinities; rather, they reflect the cluster model of the Yao people, which is based on the practical needs of reproduction in each family. Li’s analysis is very compelling, but we need more case studies to assess whether her findings go beyond Yao rituals. Therefore, we investigated the HJY in Huangdong at the family level to prove that certain Yao rituals have a shared cultural logic and similar social functions.

It is also important to try and understand how the Yao people conceptualize HJY, as this will help to clarify the nature, structure, and function of the ritual. It is important to understand the cultural background of the ethnic group, as well as the religious thoughts that make up the ritual. As Mauss elucidated, the religious thoughts in sacrificial rituals are part of a social reality (

Mauss 2002). The current research will provide insight into the purposes of Huan Jia Yuan, thereby shedding more light on its cultural connotations and social functions and process transformation.

Towards the end of 2019, our team of five researchers visited Huangdong Township in Hezhou city, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. We observed two Huan Jia Yuan rituals, which took place between 27 and 30 December and 31 December and 2 January. We interviewed several Yao individuals and some Masters of the ceremony. The account of the ceremony provided in this paper is based on this fieldwork.

Huangdong Township, Hezhou city, is located in the eastern part of Guangxi. It administers four villages: Huangdong, Dujiang, Sanqi, and Shimen. Yao people make up 75% of the population in these villages (

Government, the County 2021), and they are the Mien branch of the Yao people. Xiaoqianjin Group and Shanpo village are two typical Yao villages. After the project for the national alleviation of poverty was launched (

Government, the County 2021), the living standards in these villages greatly improved. The villagers in both villages live in two-story buildings. The area is surrounded by beautiful mountains and rivers. The folk customs are simple, and traditional Yao rituals are commonly held. This trip would be an appropriate way to explore the social functions of religious rituals by studying Huan Jia Yuan.

The Yao people in Huangdong engage in three forms of Huan Panwang Yuan, depending on the scale of the ritual. The family-based Huan Panwang Yuan (called Huan Jia Yuan), is carried out by families. Its participants are the host family, their relatives, and neighbors. The community-based version is called Huan Panwang Yuan. It is held in a public hall or playground and attended by all the villagers. The largest Huan Panwang Yuan ritual is Panwang Holiday, which is held by the local government on each Lunar 16th Oct. Each version is slightly different from the others. Compared with the national- and community-level rituals of Huan Panwang Yuan, for example, Huan Jia Yuan reflects the religious activities of an ordinary family.

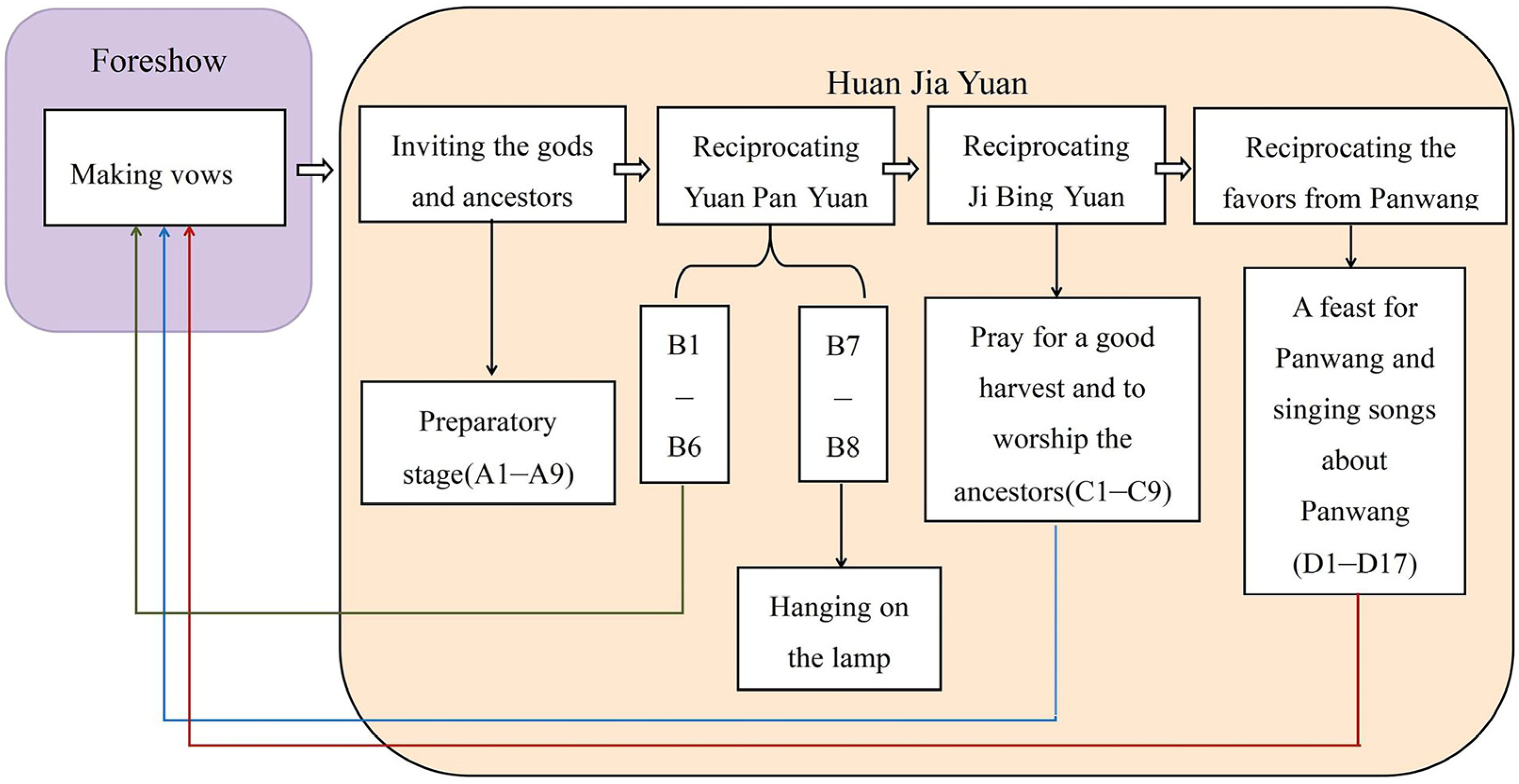

In the following sections of this paper, the ritual process of Yao HJY in Huangdong will be analyzed in detail, beginning with the preparation of HJY and followed by the four main parts: (1) inviting the gods and ancestors, (2) reciprocating Yuan Pan Yuan, (3) reciprocating Ji Bing Yuan, and (4) reciprocating the favors from Panwang. The symbolic meaning of HJY will be discussed as a ritual process, with a pattern proposed to illustrate the exchange of gifts between humans and gods and the form of communion involved. The final section of the paper focuses on the modern social functions of the ritual, namely strengthening cultural history, enhancing ethnic identity, and connecting the Yao people spiritually.

2. The Preparation of Huan Jia Yuan

Huan Jia Yuan has to be held at least once in a generation, which means it must be held once every few decades. Master Zhao Guifu

2, the son of Master Zhao Youfu

3, stated that the ritual is typically held by a family when it suffers a severe accident or experiences difficulties. The dates on which the ritual is held is arranged by masters. As for the host family we observed, neither of the past two generations had held a HJY, even though the host family, headed by Pan Zude, had a long tradition of believing in HJY. Due to the recent passing of a core family member, a brother of Pan Zude, Pan’s family decided to host a HJY to ask for mercy and protection from the gods and their ancestors, praying for blessing to help them overcome their difficulties and misfortunes. The members of the family were Pan Zude and his wife, the brothers of Pan Zude, their spouses, and their children.

As a vitally important ritual of Yao people, HJY involves making certain vows beforehand. The host family first entrusted a master to make certain vows to the gods and ancestors. The master gave the gods and ancestors notice in advance that the family would host a HJY to ask for favors from them. The date for the rite was also set in advance. Then, the host family underwent a period of preparation. For rich families, the preparation does not take long, but families who are experiencing poverty or hardship may not be prepared for the ritual when they need it. In these circumstances, a master may be invited to ask the gods for permission to delay, which is called Bangyuan (幫願). Bangyuan involves explaining to the gods why the offering must be delayed and asking for more time. In return, the host family promises to offer more sacrifices than normal. If the preparatory work goes well, then the HJY ritual is conducted at the specified time. On the stated date, the host family first engages in prayer, led by a master. The basic rule of the ceremony is as follows: whatever you pray for, you also reciprocate for. There are two types of vows: an ancestor vow, in which a person prays to their ancestors for favors, and a Panwang vow, which involves praying to Panwang. The number and content of the vows must be consistent so that the contract between humans and gods can be fulfilled.

While the master prepares the implements and paper oblations for the ritual, the family prepares the following offerings: two raw pigs, chickens, ducks, tofu, and sticky rice cakes. All of the above are prepared according to a book called Eshu (額書), passed down across the generations. In Yao society, sacrifices define or divide social groups (

Li 2008). Li (

Li 2016) specified that different groups of Yao people can be differentiated by their system of gods, ritual processes, amount of sacrifices, shapes of sacrifices, and means of slaughter. These rules are recorded as a set of fixed practices that are passed down through history. Our research in Huangdong substantiates Li’s previous finding. Each Yao family has their own Eshu, which records the process of the ritual and the sacrifices required. This varies between families. The ritual that we observed was for the Pan Zude family in a village called Qianjin, conducted by Master Zhao Youfu (

Figure 1) and his team. The four masters were the Master of Shang Bing, Li Jinbao (religious name: Li Faying); the Master of Ji Bing, Zhao Wenfu (religious name: Zhao Fachi); the Master of Grain, Zhao Youfu (religious name: Zhao Fade); the Master of Huan Yuan, Zhao Guifu (religious name: Zhao Fafu). There were also three apprentices (called “Shiti” 師替, which means “backup men”); two cooks (one male and one female); two male representatives charged with hanging lamps (which represent the inheritance of tradition); one female singer; three boys; and three virgin girls (

Figure 2).

3. The Process of Huan Jia Yuan

Huan Jia Yuan is organized into four parts, each run by the masters: inviting the gods and ancestors (請聖到壇), reciprocating Yuan Pan Yuan (圓盤願), reciprocating Ji Bing Yuan (祭兵願), and reciprocating the favors from Panwang (盤王願). The preparatory stage of the ceremony is inviting the gods and ancestors. The main focus of this is arranging the altar and inviting the gods to construct a sacred space for the ceremony. Reciprocating Yuan Pan Yuan involves responding to the vows made before Huan Jia Yuan, as well as hanging lamps. It promotes the social status of the men in the family. Reciprocating Ji Bing Yuan involves collecting grain and offering sacrifices to sacred powers. It is a ceremony in which the family pray for a good harvest and worship their ancestors. The final stage of the ceremony involves reciprocating the favors from Panwang. This takes the form of a feast, during which many songs about Panwang are sung. This stage pays tribute to the ancestors of the Yao people by performing certain customs and offering sacrifices to Panwang.

3.1. Inviting the Gods and Ancestors (Qing Sheng Dao Tan)

A1, Departure (qi bing, 起兵). At about 5 p.m. on 27 December 2019, Master Zhao Youfu burnt incense and paper money as an offering to ancestors and explained the reason for conducting Huan Jia Yuan in his own house in front of the family niche (a wooden device installed in the wall in which the family’s memorial tablet is placed). He then walked to the host’s house with paintings of the gods, a shangyuan stave

4, and the army affiliated with the ancestors.

A2, Setting (luo ma, 落馬). This was the rite of setting the paintings of the gods, the shangyuan stave, and the affiliated army in the host’s house while chanting verses at the same time.

A3, Preliminary toast (luo jiao jiu, 落腳酒,

Figure 3). This was held in the guest hall at about 7 p.m. The masters and all those accompanying them chatted together while drinking the homemade rice liquor. A simple banquet was catered by the two cooks.

A4, Decorating the altar (bu zhi shen tan, 佈置神壇). The setting drinking lasted for about two hours. Afterwards, the masters began to decorate the altar. A desk was placed against the wall in front of the family niche, and collections of paper horses and paper money were placed on the desk. Four piles of tributes were carefully placed on top of the desk, in the center. Each pile consisted of one strip of bamboo leaves, two bamboo tubes, and seven glasses. The bamboo tubes were wrapped in red paper, with a bamboo branch in each tube.

A5, Hanging up the paintings of the gods (gua shen xiang, 掛神像,

Figure 4). Once the altar had been decorated, the band started to play. The masters began to hang the portraits of the gods up in time with the music and the drumbeats. The paintings were hung up in a specific order. The first one to be hung was a new painting that had not been consecrated. Then, the paintings brought by the Master of Huan Yuan, the paintings brought by the Master of Shang Bing, and the paintings brought by the Master of Ji Bing were hung up in sequence. As there was not enough space to hang up all the paintings, the masters only hung those of the Jade Emperor (Yudi, 玉帝) and the Three Pure Ones (san qing, 三清). The Three Pure Ones are The Primeval Lord of Heaven, The Heavenly Lord of Numinous Treasure, and The Heavenly Lord of Tao and Virtue. The other paintings were stacked behind these four most important paintings.

A6, Greeting the sacred pallet

5 (qing shen pai zhan, 請神排盞,

Figure 5). At 9:30 p.m., Master Zhao Youfu began chanting about the origins of the Huan Jia Yuan, communicating the hosts’ wishes to the gods, how they promised to repay them, and what they would be willing to offer to redeem the vows. Master Zhao Youfu took the pallet over to the niche and started inviting the gods to present themselves. This process lasted for more than an hour as the name of every god that was invited had to be called out.

A7, Blessing (he xin, 賀信,

Figure 6). After the greeting finished, at around 11 p.m., the three apprentices put on religious gowns, hats, and crests, and then performed the rite. The masters and their whole team gave red envelopes with money to the host families, blessing them, and asked for the favors to be granted.

A8, Offering incense (shang xiang, 上香). Master Zhao Guifu lighted the first bunch of incense and placed it in the censer in the family niche. Subsequently, the master put the incense offering into the four bamboo tubes, which were each dedicated to the Jade Emperor and the Three Pure Ones.

A9, Inviting gods and ancestors (qing sheng dao tan, 請聖到壇). At about 0:05 a.m., master Zhao Youfu chanted the spell for inviting the gods (qing sheng zhou jing, 請聖咒經), asking them to present themselves. Nine groups of gods were invited: six from the family and three from outside the family. The inviting spell was cast twice, and the reasons for inviting the gods were clearly explained. Afterwards, spells for dispersing evil forces were cast to clear the altar.

3.2. Reciprocating Yuan Pan Yuan (Huan Yuan Pan Yuan)

B1, Greeting the sacred pallet (qing shen pai zhan, 請神排盞). Early the next morning, at around 5 a.m., Huan Yuan Pan yuan began. The first step of this ritual was offering the pallet, which involved rites such as taking out the pallet, taking over the pallet, chanting sculptures, and more.

B2, Absent spirits (shang guang, 上光). This part of the ritual began at 6 a.m. and was presided over by Master Zhao Wenfu and the two apprentices. The spirit was removed from the body of the master to communicate with the gods. Master Zhao Wenfu sat at the right side of the niche, chanting scripture, while the two apprentices, dressed in religious costumes, walked the Gang steps (steps in Taoism that are similar to walking on constellations). They walked side-by-side, circling each other, in front of the niche, chanting along with Master Zhao Wenfu. The first one, who stepped in front, held a crest with five gods and an embroidered strip. He also had a portrait of a virgin boy of guidance (yin guang tong zi, 引光童子) stuck in the crest. The second one, who stepped behind, also had a crest of five gods in his hands and a sculpture placed on top of it.

B3, Reciprocating the vow of Yuan Pan Yuan (huan yuan pan yuan, 還圓盤願). At 8:30 a.m., Master Zhao Guifu stepped forward in front of the altar. He announced to the gods that the hosts had fulfilled their promises by offering sacrifices. Master Zhao Youfu thanked the ancestors that presented themselves. Meanwhile, two apprentices poured liquor into a bowl and glasses, presenting them to each other in turn. This symbolized the process of pouring out liquor to the gods. Then, Master Zhao Youfu purified the water, performed divination, and chanted scriptures beside the altar. During the third divination, a symbol illustrated that the gods had accepted the sacrifices.

B4, Paying money (jiao zhi qian, 交紙錢). This is a rite in which paper money is burnt to give thanks to the gods. At 9:30 a.m., the masters counted the paper money and then burnt it in a sacrifice.

B5, Offering money (yun qian, 運錢). When all the paper money had been burnt, the band started to play. In combination with the Taoist music, Masters Zhao Guifu and Zhao Wenfu walked the Gang steps around the ashes of the money. Then they put down staves, walked the Gang steps without anything in their hands. They held up their hands to offer money to the gods. Afterwards, Master Zhao Guifu performed divination three times, and the results demonstrated that the gods had accepted the money.

B6, The return of the spirit (tuo tong, 脫童). This started at 10 a.m., when the spirit came back. Two masters sat in chairs in front of the altar, holding sculptures, an ivory tablet, and bronze rings. They sang the Song of the Return of the Spirit (tuo tong ge, 脫童歌). When they had finished the song, Master Li Jinbao led the two representatives in a dance.

B7, Empowering the paintings (shen xiang kai guang, 神像開光). The Yao people believe that paintings of gods that have not received spells are not sacred and do not possess spiritual power. In this session of Huan Jia Yuan, the masters enabled the new paintings of the gods to become sacred. Master Zhao Guifu used a religious sword to gesticulate, tracing the name of a god against the red candlelight. He cast spells in silence and then gently placed the red candle in front of the new portraits.

B8, Hanging on the lamp (gua deng, 掛燈). Traditionally, oil lamps must be hung by the son of the host. However, in this case, the host had no son, so two of his nephews, who were both representatives, took over the rite. At 12:40 p.m., Master Zhao Guifu put three oil lamps and two chairs in place for a rite of exorcism. The two nephews wore religious costumes and sat in the two chairs. They were surrounded by the chanting masters. Master Li Jibao lit the oil lamps and passed the lamps to the two nephews. Together, they prudently placed the lamps onto the desk. Then, Master Zhao Guifu and Master Zhao Wenfu enchanted the two nephews by encircling them, performing Taoist rites such as fen bing mi (the dispersal of rice, symbolizing the army, 分兵米), xue fa (symbolizing the process of learning magic arts in Taoism, 學法), and da gao (Taoist divination,打筶). The nephews were raised to their feet by the two masters with the help of the shangyuan staves. At the same time, the masters sang a short verse from a ballad: “the river’s stream outside the house, raise up the representatives to be big men” (门前江水转湾湾,抬起师男做大官). They issued a blessing, hoping that the nephews would improve their social status.

3.3. Reciprocating Ji Bing Yuan (Huan Ji Bing Yuan)

C1, Greeting the sacred pallet (qing shen pai zhan, 請神排盞). At 2:20 p.m., Master Zhao Youfu placed the pallet on the altar and made an invitation. This process was similar to the one described in B1. However, different scriptures were chanted.

C2, Absent spirit (shang guang, 上光). This session, the same as the one described in B2, was performed at 3 p.m. It was conducted by three masters using the following scriptures: Zhi Sheng Shang Guang (執聖上光).

C3, Inviting the grains (zhao he, 招禾). This process began at 5 p.m. It involved several procedures, such as hanging a streamer with five types of grain, inviting the gods of the five types of grain, lighting the incense of shuming, and opening the gate of heaven. The steamer of five grains was made using a whole bamboo branch with proliferous leaves (

Figure 7). During the rites, boys and girls attached rice panicles, corns, and paper money to the bamboo branch, symbolizing that the host family would be prosperous in the future and receive grain and money. The god of five grains is worshipped by the Yao people. This god is responsible for ensuring a good harvest, and a good harvest ensures that the family is prosperous. After lighting the incense of shu ming

6, Master Zhao Wenfu chanted outside the front gate, blew the ox horn, burnt the paper money, and opened up the gate of heaven. Afterwards, Master Zhao Wenfu da gao (forecasted) three times to ensure that the rite had been completed.

C4, Enchanting grains (bian he, 變禾). At 6:30 p.m., master Zhao Wenfu stood next to the front gate and cast spells on a bamboo basket filled with rice panicles. He chanted da gao. He then weighed the basket using a traditional Chinese steelyard balance. He placed strips of the steamer on the steelyard, knocked the steelyard using a religious sword, and chanted the god of five grains. The host couple greeted the god at the front gate, and Master Zhao Wenfu acted as if the god had arrived and was in possession of his body. The couple took the basket and carried it into the house. When this was done, firecrackers were lit up in celebration.

C5, Cultivating troops (yu bin, 育兵). This began at 8:55 p.m. Three boys and the three apprentices stood face-to-face at the front gate. The host held the shangyuan stave and stood in the center of the guest hall. The six men danced the yu bin dance, holding ears of rice in their hands, accompanied by chanting by Master Li Jinbao. When they had finished the dance, they presented the rice pinnacles to the host, who tied them onto the top of the shangyuan stave. The suobing dance (鎖兵舞) and the da ma dance (打馬舞) followed. At 9:15 p.m., Master Zhao Wenfu began to chant to invite the dragons of prosperity, flourishing, and security. Twenty-five minutes later, Master Zhao Wenfu issued a call to all the forces of power to come to the religious sword. He then placed the sword next to a deity jar, indicating that the forces of power had settled peacefully in the jar.

C6, Recalling the troops (he bing, 合兵). This rite, which started at 10:10 p.m., was intended to recall all the divine generals and soldiers. It was performed via a dance of recalling that was performed by two of the apprentices, while Master Zhao Guifu chanted.

C7, Worshipping the dragon (ji bing, 祭兵). This was a rite to worship the divine dragon. At 10:50 p.m., two of the apprentices chanted the scriptures of worship nine times (

Figure 8), after which Master Zhao Guifu performed da gao to forecast the harvest.

C8, Reciprocating Ji Bing Yuan (huan ji bing yuan, 還祭兵願). The masters started to prepare the altar at 0:22 a.m., on which they placed three sacrificial jars and lamps for hanging, shang bing and ji bing. Shang bing and ji bing are both rites to express gratitude to the troops brought by gods and ancestors. The masters would offer sacrifices to the troops for their protection and help. The masters invited the ancestors in a certain order, offering them libations and chanting. The three apprentices stood in front of the three jars, each hand holding a glass. They poured the liquid from one hand to the other, which represented the process of offering libations to the ancestors. Subsequently, the following rites were performed: qing qing yuan jiao (inviting the gods, 請清元醮,

Figure 9); kai gu zhen (distributing zongzi, a kind of traditional Chinese snack, to ghosts, 開古貞); suo yuan (confirming the content and number of the sacrifices, 鎖願); jiao zhi qian (offering paper money to the gods, 交紙錢).

C9, Promise completion (chai yuan sha zhu, 拆願殺豬). Beginning at 2 a.m., a virgin boy for vow-making (xu yuan tong zi, 許願童子) was asked to witness the prayers of the host. The host promised to offer certain sacrifices to the gods. Thereafter, the masters chanted to check the amount with the gods. At 3 a.m., in preparation for the sacrifice to Panwang, the masters and cooks slaughtered a pig, gathered the blood in a basin, doused the paper money in the blood, and burned everything. The pig’s guts were cleared, and its head was put aside. The rest of the pig was chopped into big pieces.

3.4. Reciprocating the Favors from Panwang (Huan Panwang Yuan)

This fourth session required the altar to be redecorated.

D1, Preparing the banquet for Panwang (bai Panwang yan xi, 擺盤王宴席). At 6 a.m. on 29th December, sticky rice wrapped in leaves was put on the altar along with pork and eight big bowls. Little flags made of colored paper were stuck in the rice wraps. The pig head was placed in the center of the altar, wrapped with the pig lung. The fried tofu was placed on top of the head, and an oil lamp was placed on top of the tofu. The pig’s guts were placed in two baskets on the left and right sides of the altar. The eight bowls were placed in front of them.

D2, Hanging up the red curtain (gua hong luo zhang, 掛紅羅帳). Master Zhao Youfu made a curtain out of red paper, using traditional techniques of Chinese paper cutting. He stuck this on the wall behind the altar. Two strings of paper money were hung on either side of the curtain.

D3, Housewarming party (he xin wu jiu, 喝新屋酒). The curtain represented a new house for Panwang. The decoration was completed by 8:20 a.m., which meant that the new house was built. The masters and the other people affiliated with the ritual drank a toast to the newly completed house.

D4, Greeting the sacred pallet (qing shen pai zhan, 請神排盞). This process was very similar to those described at B1 and C1. It was led by Master Zhao Youfu, who chanted scriptures about Panwang.

D5, Inviting Panwang (qing Panwang, 請盤王). At 10 a.m., Master Zhao Guifu stood on a cushion made of dry grass, dressed in a religious costume, holding sculptures. He sang a song in praise of Panwang, inviting him to present himself. When Panwang arrived, the guest hall became a sacred space in which Panwang and the believers were gathered. All the people in the hall had to wear the traditional hat of the Yao people and were allowed to speak only using the Yao language.

D6, Praising Panwang (dian yao dian nv, 點瑤點女). A rite was conducted by boys and girls in praise of Panwang. At 10:40 a.m., three boys and three girls stood facing each other in two lines of pairs. They fed each other tofu and gave each other rice wine.

D7, Taking seats (ru xi ge, 入席歌). The boys and girls sang songs to Panwang, at 11:06 a.m., asking him to take a seat at the banquet. At the same time, the master chanted on his knees, inviting Panwang to take the seat and enjoy the sacrifice.

D8, Absent Spirit (shang guang, 上光). At 11:23 a.m., Master Zhao Guifu started to chant while an apprentice walked the Gang steps, as described in B2.

D9, Inviting King Tang (qing tang wang, 請唐王). At 12:10 p.m., the masters invited King Tang. King Tang refers to Li Shimin (598–649 A.D.), the well-known and respected emperor from the Tang dynasty. Inviting Li Shimin to join in the ritual may reflect the ancient practice of reciprocating Panwang for favors.

D10, Performing construction (da tie xiu lu, 打鐵修路). This was a performance that showed how the believers overcame all kinds of difficulties to mend a road for Panwang. Starting at 12:19 p.m., the masters and apprentices acted out scenes of people mending roads, lumbering, casting iron, and building bridges. The acting was done in an exaggerated way to entertain the spectators.

D11, Inviting the God of Sweeping (qing Saodishen, 請掃地神). The God of Sweeping was invited to provide cleaning for Panwang, the other gods, and the ancestors. At 12:40 p.m., the ritual moved into the qing Saodishen session.

D12, Performing the slaughtering of a pig (biao yan sha zhu, 表演殺豬). This step, which began at 12:57 p.m., reproduced the scene of the pig slaughter from the previous night, allowing Panwang to witness it. Panwang is not pleased if he is unable to witness the slaughter.

D13, Greeting Panwang (jie Panwang, 接盤王). At 1:10 p.m., an apprentice pretended to be Panwang and knocked on the front door. After a series of questions and answers, Panwang was welcomed into the house.

D14, Performing the long-drum dance (tiao chang gu wu, 跳長鼓舞). The long-drum dance was a form of amusement for Panwang at 2:38 p.m. Master Zhao Guifu performed a solo dance, for he was the renowned heir of the intangible cultural heritage of the long-drum dance in Hezhou (

Figure 10). Meanwhile, Master Zhao Youfu sat in a chair and chanted as an accompaniment.

D15, The thanks–giving rite (wei ge tang, 圍歌堂). At 2:46 p.m., the boys and girls stood in two lines and the female singer stood at the head of them. They began to sing Yao ballads. Master Zhao Guifu, along with an apprentice, chanted and rang a bell. He stepped from the altar and circled around the people who were singing before returning to the altar.

D16, Singing the songs of Panwang (chang Panwang da ge, 唱盤王大歌). The songs of Panwang come from several chapters: hong shui sha qu; san feng xian; mu wan duan; he ye bei; nan hua zi; fei jiang nan; and mei hua da wan jiu. The traditional way of singing the songs of Panwang is to sing the chapters one by one. In this case, however, each of the masters took some of the songs and sang them synchronously, beginning at 6:59 p.m.. The modern way of singing was intended to reduce the time of the ritual and save some money for the host.

D17, A final toast (san xi jiu, 散席酒). The first step of ending Huan Jia Yuan, which started at 4 a.m., was to chant scriptures that would send Panwang back to his palace. Afterwards, all the people who participated in the ritual drank a toast and prepared to leave. The masters gave red envelopes to the host (with a small amount of money inside) as gifts to bless the family. The host family then distributed the pork to the masters and the other people affiliated with the ritual in thanks. When the masters left, the singer sang farewell.

4. The Structure and Ritual Symbolism of Huan Jia Yuan

Since ritual should be analyzed and understood in its real context (

Bell 1997), the following analysis and discussion are based on the Yao people’s perspective of HJY. For the Yao people in Huangdong, HJY is a ritual for worshipping their ancestors, getting through crises, and asking for protections. Reciprocation should be regarded as the response to the vows, the fulfillment of the promise to the gods and ancestors. The fulfillment of the promise is presented through sacrifices such as gifts given during the ritual. The whole process of HJY, although complicated, is tightly focused on a key point: to communicate with gods and ancestors, which, through the exchange of gifts, forms the core of the ritual. To ensure the whole process works as tradition dictates, the first thing that happens in HJY is the preparation of the sacred altar and the invitation of the gods and ancestors (from A1 to A9). The offering should be conducted in a sacred space. Therefore, at the beginning of the ritual, the masters perform a series of rites. They begin by decorating an altar for the gods and ancestors, inviting them to arrive. They place all the on the altar. Then, they call the names of the invited gods and ancestors, encouraging them to accept the sacrifices.

The first six steps in reciprocating Yuan Pan Yuan (B1 to B6) involve offering sacrifices to ancestors and fulfilling the promises of the vows. Pan Zude from the host family made vows to gods and ancestors through Master Zhao Youfu, asking them to protect the whole family from disasters and misfortunes. He also hoped that the family would not suffer from the loss of their family members and that they would become more prosperous. Although the favors have not yet been given, sacrifices are typically offered at this point.

HJY stems from the contract between humans and the gods. The offering is the concrete expression of this contract. The gift is given out of necessity because the recipient has some kind of ownership over what belongs to the giver (

Mauss 2002). Once the vows have been made, the ownership of the sacrifices shifts from the host family to gods. The spirits are a central part of the sacrifices that are offered to them; if they avoid the ritual, then the family will be worse off. At the same time, there is also a series of rights and obligations to enjoy and return (

Mauss 2002); the exchange of offerings between humans and gods is no exception. The Yao people who make vows are obliged to offer the sacrifice; the deity who accepts the sacrifice is obliged to fulfill the wish and bless the family that made the vow. The gods have the power to influence and control real life. They are the true owners of the wealth of the world. Therefore, for the Yao people, offering sacrifices to the spirits not only prevents them from slipping into a worse situation, but also provides them with rich rewards.

The Yao people believe that once they have offered sacrifices to the gods, the gods will bless them and respond to their needs. They believe that the real-life dilemmas they face will be naturally resolved by the intercession of the gods. This kind of strategy for resolving problems reveals the logic of material exchange in the human–divine contract. The Yao people have the belief that the sacred gods are still connected to humans since they are pleased to receive offerings from believers. In return, they provide them with protection and blessings. On the other hand, the Yao people believe that if the gods do not receive offerings, then they will provoke disasters. Hence, the Yao people have faith in the need to maintain integrity and respect the gods. They believe that this will help them to receive blessings from the gods, which explains why the first six steps involved reciprocation to the ancestors and the gods.

The human–divine contract also reflects the Yao perception of economics, along with the spirit of contract. The Bangyuan rite is a vivid example of this. “It’s like loan. You have to pay more interest to the bank for an extension.“explained Master Zhao Youfu. These economic thoughts are reflected in the Yao belief in the human–divine contract. If they make a vow, they must keep it, or there will be punishment for breaking the contract. For example, they will have to offer more sacrifices. This could be understood as the spirit of contract, but it is also about respecting, enchanting, and pleasing the gods and ancestors. The exchange of offerings and blessings makes for a spiritual communication between the humans and the gods. Per Bell, “Direct offerings may be given to praise, please, and placate the divine power, or they may involve an explicit exchange by which human beings provide sustenance to divine powers in return for divine contributions to human well-being”. (

Bell 1997) Each session of HJY has a specific topic and is focused on specific gods. Therefore, the offerings and the expected favors are different, even though the structure of the rituals is similar. Besides the core rites, there are some rites of passage and banquet in the ritual that do not seem to be directly related to exchange or communication. Nevertheless, they are for the purposes of exchange and communication.

The processes of hanging on lamps and empowering paintings in reciprocating Yuan Pan Yuan are supplementary rituals. If the party already has a statue of a consecrated deity in their home, or the male in the family has already hung the lamp, then there is no need to perform these supplementary ceremonies. Ceremonies involving the hanging of lamps are very popular among the Yao people in the Nanling Circuit (南嶺走廊)

7. To save costs, the acts of hanging on the lamps and empowering the paintings are usually combined. Both empowering the paintings (B7) and hanging on the lamp (B8) are rites to help the family members get closer to the gods.The Yao people believe that this will increase the capabilities and social status of the family members. Hanging on the lamps is a basic rite of passage for a young male Yao to get an identity that is invested with divinity. The rite empowers the young men, teaching them magic arts. It assigns 36 soldiers from the ancestors to them symbolically, giving them protectionfrom the family. HJY is not a ceremony of growing up for a young man. However, hanging lamps, which could be regarded as a supplementary rite of HJY, carries this function. The Yao people believe that the prospects of male members in a family are related to the destiny of the whole family.Therefore, a rite to empower the male members, to some extent, could be understood as a social debut, passed down as a tradition as part of an important ritual.

Reciprocating Ji Bing Yuan is a ceremony that theYao people use to worship the army of their ancestors and pray for a good harvest. The core meaning of this is communion. The ceremony imitates the traditional farming activities of the Yao people, connecting worship with agricultural production. The Yao people have lived in the mountains of the Nanling Circuit since ancient times. Rice farming has been their main source of food and income. The harvest directly determines whether they can afford to host a HJY ritual. The primitive, agricultural life of the Yao people is on display during the Huan Jia Yuan ceremony. The Yao people use rice and paper money to make five-grain banners, symbolizing prosperity and the prosperity of the family members. The rites of zhao he, yu miao, and bian he represent the process of cultivating seeds, growing them, and harvesting the grains. The rite of ji bing represents the process of worshipping and sacrificing to the Dragon King and the ancestors’ army. The ancestors’ army is thought to be the guardians of the family. The Dragon King is in charge of rainfall and is a god that symbolizes a good harvest. Reciprocating Ji Bing Yuan is a ceremony in which people pray for a good crop harvest and prosperity. Plentiful food is accompanied by the accumulation of material wealth, leading to a healthy population. The Yao people worship their ancestors, pray to the dragon gods, and pray for a good crop harvest to increase their ability to survive and decrease their risk.

The last stage of Huan Jia Yuan, reciprocating the favors of Panwang, is highly symbolic. Anthropologists (

Turner 1969) believe that symbolic things are often connected with empirical things that relate to the past experiences of a group. Reciprocating the favors from Panwang is no exception. The ceremony originated with the legend of

The Voyage across the Sea at the Mercy of the Waves (piao yang guo hai). According to this legend, the migrating Yao people encountered bad weather at sea. In their moment of need, they made a bequest to their ancestor Panwang, promising to offer a fat pig to Panwang if they reached land safely. They got out of trouble and then fulfilled their promise by offering a whole pig to Panwang. This story provides the social memory for the origin of the ceremony of reciprocating the favors of Panwang. Yao people who have migrated to all parts of the southwest and even the southeast of Asia have maintained this ancient tradition of Huan Jia Yuan.

The sacrifice to Panwang has a very long history, so it needs to be emphasized that there is a difference in the ritual pattern between the traditional story and the ceremony of Huan Jia Yuan that is conducted in Huangdong Township. The current research compared the process of Yao HJY in ancient times recorded by Li Mo in the Yao legend with the investigation of HJY in Huangdong, finding that the structures of the rituals have changed throughout history. Roughly, the story in which Panwang helped the Yao goes as follows (

Li 2005):

Pattern 1: There is a crisis. The people make a vow to Panwang. Panwang manifests his spirit. The crisis is lifted. The ceremony of Huan Jia Yuan is carried out.

Repayment rituals in Chinese folklore follow Pattern 1. People make vows to the gods in temples. Then, once their favors have been granted, they return to the same temple to repay the favor and thank the gods. The pattern of the Yao Huan Jia Yuan conducted in Huangdong Township is as follows:

Pattern 2: There is a crisis. The people give notice to the gods in advance for the favor. Huan Jia Yuan is carried out. The gods are expected to appear and lift the crisis.

By comparing the two ritual modes, it can be seen that the sequence of offering gifts and giving blessings has changed. This reveals the mutual trust that has been built between the Yao people and the gods. In the former mode, the gods saved the Yao people without receiving any gifts in advance, thereby winning the trust and worship of the Yao people. In the ritual studied here, the Yao people stressed the importance of keeping their promise, which was regarded as a guarantee of protection from Panwang. Since Panwang had proved that his mercy had been effective in the past, the Yao are willing to offer sacrifices in advance to express their gratitude and respect for Panwang. In return, they expect a Panwang to save them from real predicaments. People who conduct HJY on time receive more favors from Panwang. In contrast to Pattern 1, the purpose of HJY is not constrained to “returning the favor”. Rather, it is performed in anticipation of receiving favor for the gifts that the Yao have offered. When HJY was held, the crisis had not yet disappeared. Even though the ceremony expressed gratitude to the gods, the real purpose was to relieve the crisis. To the Yao people, the payback that they receive from the gods is help to eliminate a crisis; to the gods, accepting the gifts is a symbol that reminds them to bestow their blessing. This model of repayment is similar to that employed by other ethnic groups. For example, in the Kai Da Jing ritual mentioned above, vows and repayments are made in advance, before the favors are bestowed. The “repayment first” model of the HJY does not violate what Mauss described as the model of “offer–accept–repay”. It echoes this model in that it contains the basic elements of “offer”, “accept”, and “repay”. However, because of the solid relationship established between the Yao people and Panwang, the Yao believe that Panwang will help them, so repayment is assured in advance. They therefore offer payment before receiving the gods’ help. HJY demonstrates the symbolic meaning of human–divine exchange throughout. This consolidates Mauss’s model, since the three elements of gift–giving are present and are central to the ritual.

The story of Panwang’s appearance in the legend reflects the inner cultural logic of the Yao people in Huangdong. Huan Jia Yuan repeats the Yao people’s original experience of migration. The ceremony showcases how the Yao people attempt to cope with their crises and expresses their wish for peace. Although each session of Huan Jia Yuan has a different symbolic meaning, the ultimate purpose of these different sessions is the same (

Figure 11). At first glance, HJY appeared complicated because it contains three reciprocating rites, one identity–shift rite, and a few other performances. The sacrifices and targeted gods change during the ritual. However, all the elements (including offering sacrifices, performing, enchanting gods, empowering participants, and more) are connected by certain core elements: exchanginggifts and communicating with the gods, that is, making offerings and expecting favors in return.

5. The Social Functions of Huan Jia Yuan

During HJY, the Yao people express their trust in the gods for their sacred powers. They hope for a payback in return. They believe that the ritual will help them with the difficulties they face in real life, just like in the story of Panwang saving the Yao people’s ancestors several thousand years ago. When we asked about the purpose of Huan Jia Yuan during our investigative fieldwork, Master Zhao Youfu said, “When a family is experiencing misfortune, they will come to us and ask us to perform Huan Jia Yuan”. The host, Pan Zude, said, “After the ceremony, the family’s situation will improve”. Master Zhao Youfu added, “In the past, someone here was mentally ill, and there was no way to solve the problem. After he conducted the ritual, he has been improving ever since. He gained lots of energy after the ritual and seemed to be cured. He lived until last year, ten or twenty years after the ritual. Also, there used to be a party secretary from Zhijiang Village who used to get very frustrated as members of his family would often get sick. He asked us for divination and we recommended the Huan Jia Yuan ceremony. A month later, he won more than 10,000 yuan in the lottery. Since then, no one in his family has been ill, and he has not needed to take medicine for more than a year. Huan Jia Yuan can sometimes be very magical”. This statement demonstrates people’s sincere belief in the power of Huan Jia Yuan, explaining why the Yao people continue to perform this ritual. Although the advancement of modern social sciences and medicine has meant that many Yao people no longer rely on religious rituals to resolve their problems, stories about the effectiveness of the rituals continue to circulate in the local area. When they encounter problems that they cannot solve, the Yao people still often turn to Huan Jia Yuan.

The structure and social functions of Huan Jia Yuan have changed throughout history. Social development has impacted the kinds of requests that people make. The former issues of poverty and the lack of medical treatment are no longer the major crises faced by the Yao people in Huangdong Township. As of 2020, the poverty rate has been reduced to 2.18%, and the new rural cooperative medical system covers more than 98% of the population (

Government, the County 2021;

Lei 2019). As living conditions have improved, the Yao people have encountered another major social issue: namely, identification. The Yao people, like all other ethnic groups, face problems such as a decline in cultural confidence, a weakening of group connectivity, and a deviation from traditions. All of these are more worrying to the Yao people than natural disasters or poverty. Therefore, one of the most significant functions of Huan Jia Yuan today is to foster social connections.

In Yao society, the gift–exchange with pork and rice strengthens the relationship among families in the same worshiping group (

Li 2016). The expenses of HJY are not borne only by the victim’s core family but by their extended family. Pan Shuai told us that due to a recent surge in pork prices, it would have cost a lot of money to buy two fat pigs. To reduce the financial burden, the reciprocation ceremony was jointly organized by the host’s brothers. By spreading the cost, they were able to pay for the two pigs. During the ceremony, a number of the family’s relatives also gifted them money and paid visits. Thus, Huan Jia Yuan combined the family’s interpersonal capital and material resources.

The Yao people who participate in the ritual that we observed believed that Huan Jia Yuan is an important tradition for the Yao people. As members of the Yao people, they felt obliged to participate in the ceremony. Li Shu, the nephew of the host who participated in the lamp hanging rite, said, “This ‘Huan Jia Yuan’ is a tradition of the Yao people”. Another representative, named Pan Shuai, told us, “I heard that they were going to do a ceremony, and my uncle asked me to experience it so that I would be able to keep our traditions alive in a profitable way”.

The Huan Jia Yuan ceremony gathered together many different Yao people who were scattered around the city. They were joined together to worship their ancestors and review the people’s history of migration. Pan Shuai’s family, who participated in the ceremony, had settled in the city a long time ago. Today, they rarely return to their hometown. Pan Shuai said, “I only go back once every six months. I come back to help out during Chinese New Year or when there are ceremonies at home”. The ritual brings together the descendants of the Yao people who are far away from their hometowns. These people voluntarily participate in Huan Jia Yuan and contribute their money and energy.

The ceremony brought the family together and allowed them to combine their resources. Pan Shuai and Li Shu acquired their exclusive religious names and inherited the sacred power of their ancestors. Thus, the ritual not only helps people to understand their Yao identity but also ensures that Yao traditions can be passed down from generation to generation. There is widespread evidence that participation in collective rituals promotes social cohesion among the participants. The advantage of rituals is that they produce social cohesion due to their impact on people’s property and the size of people’s social network. However, rituals are perceived as more efficacious because they motivate participants to attend them repeatedly regardless of their the social impact (

Kaše and Hampejs 2016). The ceremony also provides a sense of historical memory and cultural inheritance (

Leach 1954;

Malinowski 1962;

Lightstone and Bird 1995). Pan Shuai said, “When my child grows up, he will also be taken to experience Huan Jia Yuan”.

Master Zhao Guifu said, “A nation may fall apart if it does not have its own culture and beliefs. Take us as an example, some Yao people do not care about their ancestors. They have not conducted Huan Jia Yuan for many years. They have nothing to do and no connection with their ancestors. Generally, people like that jeopardize their wealth and live inharmonious lives. Sometimes, even when a family is rich and wealthy, they may still lead an unhappy life. We have a lot of people who are dedicated to respecting our ancestors. No matter how poor they are, they will eventually overcome this”. In his view, Huan Jia Yuan is a ceremony that marks the inheritance of the Yao people’s culture and beliefs. It allows people to worship their ancestors. If a family neglects their cultural inheritance, they will probably lose their faith and experience difficulty in their life.

The Yao people believe that Huan Jia Yuan is a festive ceremony. Relatives, friends, and people from the same village attend the ritual and help out. Many Yao people take pictures of the ceremony and upload them to social media platforms such as WeChat and Weibo. This means that Huan Jia Yuan not only helps the organizers of the ritual to connect but also allows the connections to spread among people who observe the ritual remotely. Many Yao people watch the performance online and are proud of their traditional rituals and culture. A young Yao person, aged 26, who was a relative of the host family, told us, “This is our tradition. We all come here to play and are very happy”. Ritual is considered to be a kind of social convention made up of group norms and moral values (

Chan 2012). Its functions include nurturing and inspiring group members with abundant educational thoughts. Ritual plays a vital part in the life of an ethnic group due to its social functions. For example, it can help with identifying group members, ensuring commitment to the group, facilitating cooperation, and maintaining group cohesion (

Watson-Jones and Legare 2016). The widespread use of social media has also made it possible for Yao people to remain closely connected as a society. On the third day of the ritual, a person named Zhao Guizhen posted a video of the ceremony on a “we media” account on WeChat. The video was entitled “Yao culture” and received more than 3000 views. Many Yao people left comments on the video. A netizen named “Han Zi” left a message saying, "I hope that the Yao culture will be passed on from generation to generation”. A netizen named “Qingshan” also left a message, saying, “[We have to] inherit the traditional customs of the Yao people. This ritual is the spirit of the Yao people”. The sense of national identity and pride contained in these messages is clear. This finding is in accordance with what was identified in other religious rituals, “opening a world in which these events are configured in new ways for the current participants, so that they can enter them, imagine themselves within them, and bring them into their lives” (

Gschwandtner 2021.)

6. Conclusions

Huan Jia Yuan is a traditional ritual for the Yao people that has considerable symbolic significance and important social functions. It highlights the unique religious beliefs and ritual activities of the Yao. The function of the ceremony is to ensure the survival of the ancient wisdom of the Yao people and help them to solve problems through the help of the gods. HJY has helped the Yao people to stay connected with the gods for several thousand years. It helps them ensure that the gods will be benevolent. The Yao people have received more form the gods than they had anticipated, because their rituals have strengthened their sense of cultural history, enhanced their ethnic identity, and created a spiritual connection among them.

The Yao people have developed the model of human–divine exchange into a regular religious ritual, which they have enriched throughout their history. Before the development of modern society, relief from disaster was the most important social function of Huan Jia Yuan since many of the Yao people used to live in rugged conditions. Today, however, the ritual has developed into an activity that not only helps to relieve disasters but also allows diverse groups of Yao people to connect as an ethnic group. The ritual helps to maintain spiritual bonds between the Yao people and their gods, awakening people’s faith in their community. It also helps to connect Yao people who have moved away from their homes. It keeps people united and communicates a shared sense of history, thereby restoring national identity and confidence in their culture.

The inheritance of Huan Jia Yuan in Hezhou and the changes in the ceremony demonstrate the inner logic of the ritual: reciprocating and connecting. To some extent, the functions of maintaining cultural inheritance and fostering connections between people are more important than the spiritual act of eliminating disasters. Human beings are well accustomed to learning from the past to solve problems in the present. Huan Jia Yuan is a part of this general human tendency to solve problems. By worshipping ancestors and gods as a solution to real problems, as well as by repeating past experiences so that favors been granted, the Yao people bring their inherited traditions into connection with modern life. Thus, we can conclude that ancient rituals and traditions help people to deal with issues in modern society. This is worthy of further research.

There are certain limitations to the current study related to the mutualistic relationship between transitions in living conditions and the evolution of religious rituals. However, this also demonstrates the anthropological importance of studying rituals. One limitation is that there are several sub-branches of Yao people (such as Pan Yao, Tu Yao, Landian Yao, and more). The Huan Jia Yuan rituals of these groups are slightly different. This research analyzed the process in Huangdong Township, but it was unable to present all the characteristics or functions of Huan Jia Yuan in all the different sub-branches of the Yao people. The other limitation of this research is that it was not able to cover both historic and geographic perspectives in its exploration of the social functions and connotations of Huan Jia Yuan. Due to the limited focus of the current study, this paper was not able to extend its analysis in these directions, but we hope that future studies will take them up.