What Kind of Islamophobia? Representation of Muslims and Islam in Italian and Spanish Media

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Islam in Western Media

2.2. What Kind of Islamophobia?

3. Methods

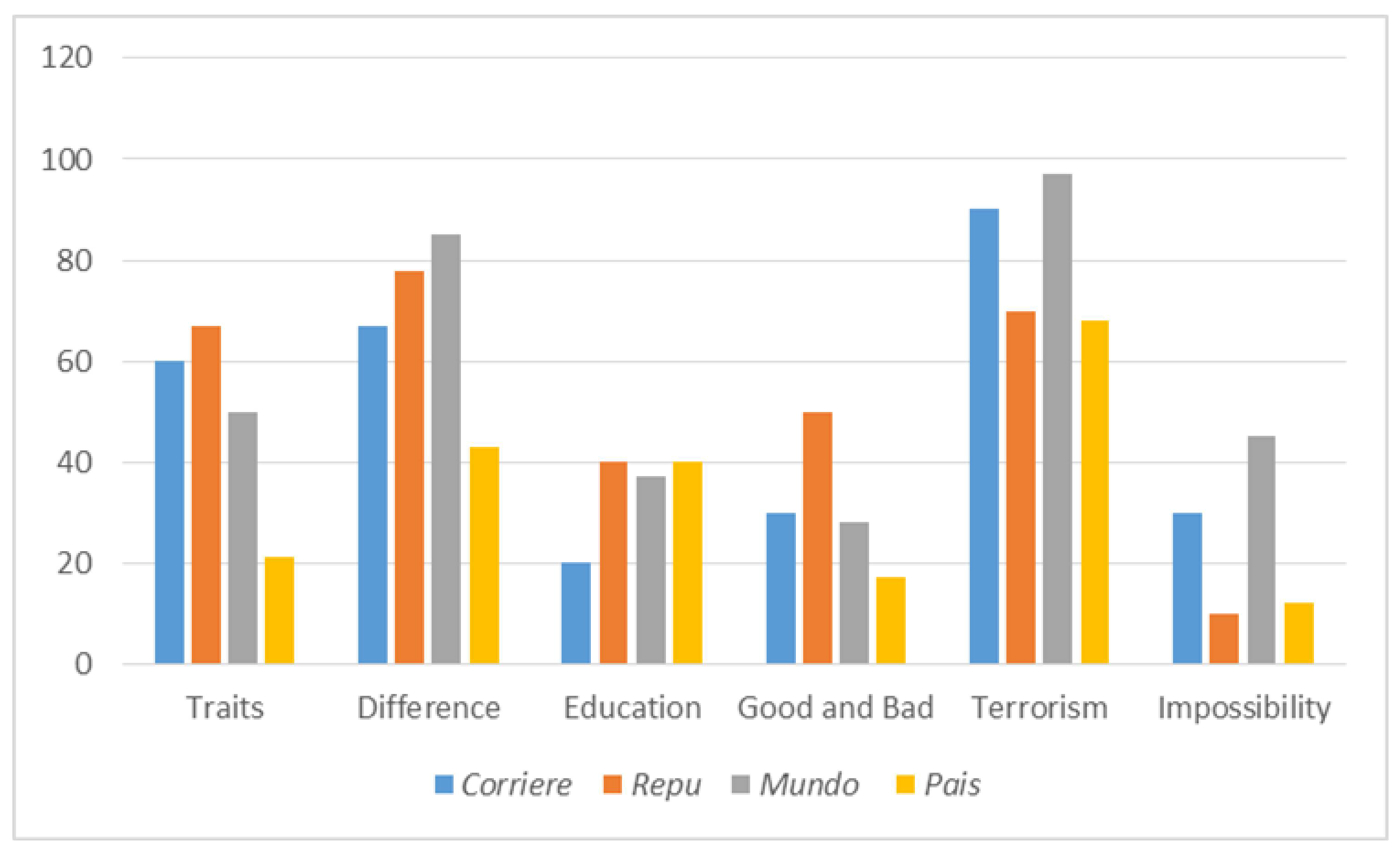

- Marker of reification: lack of differentiation (all Muslims are the same);

- Positive/negative/neutral tone;

- Marker of Banal Islamophobia: identifying Muslims with particular racial (race, skin tone) or visual (hijab; abaya) traits, habits, or attitudes;

- Marker of Banal Islamophobia: depiction of Islam/Muslims as different (from “us”);

- Marker of Banal Islamophobia: expressions referring to the “re-education” of Muslims;

- Marker of Banal Islamophobia: expressions referring to “Good Muslims” and “Bad Muslims”;

- Marker of Ontological Islamophobia: identifying Islam/Muslims with violence/terrorism/fanaticism;

- Marker of Ontological Islamophobia: explicit mention of the impossibility of coexistence.

4. Results

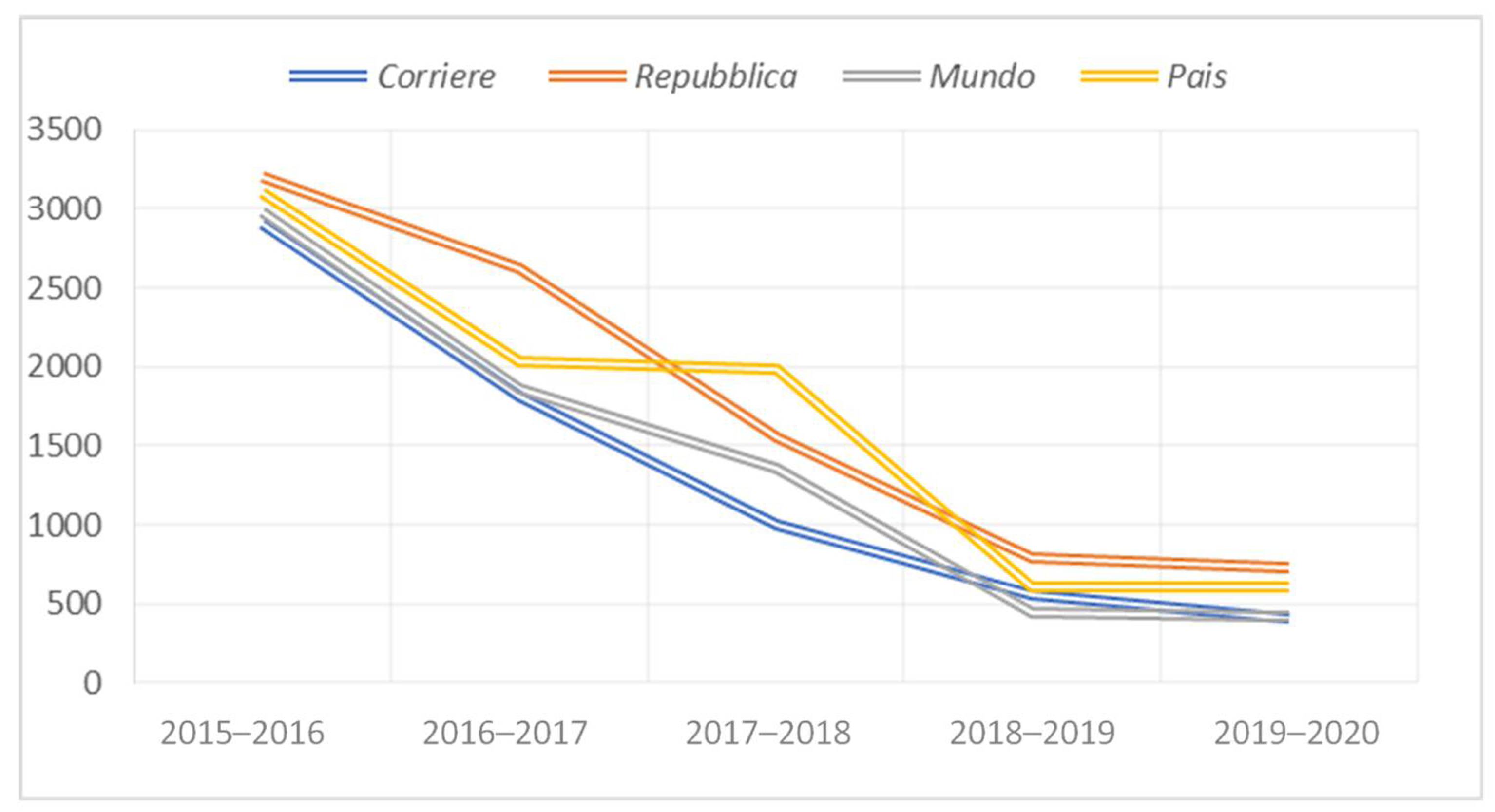

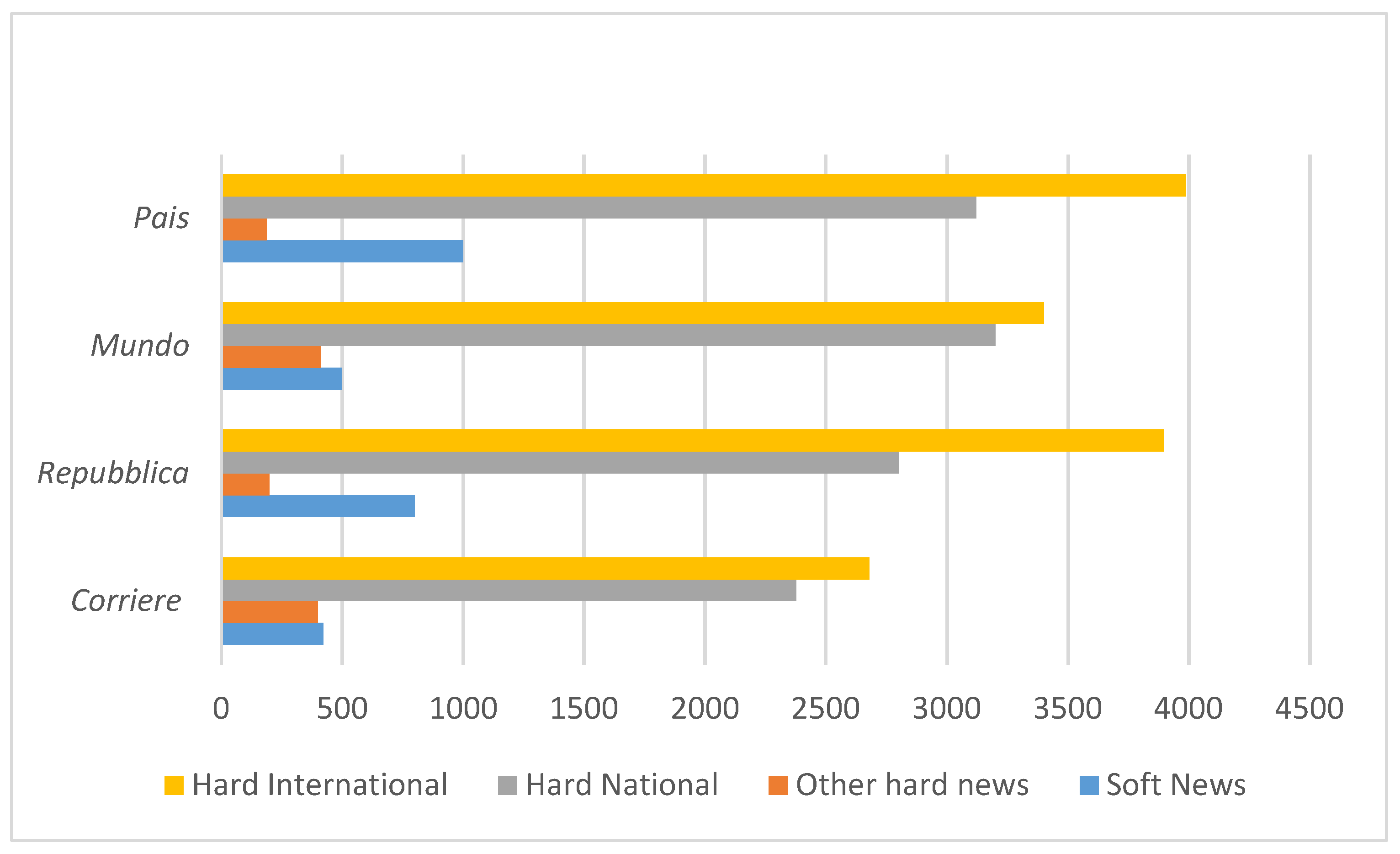

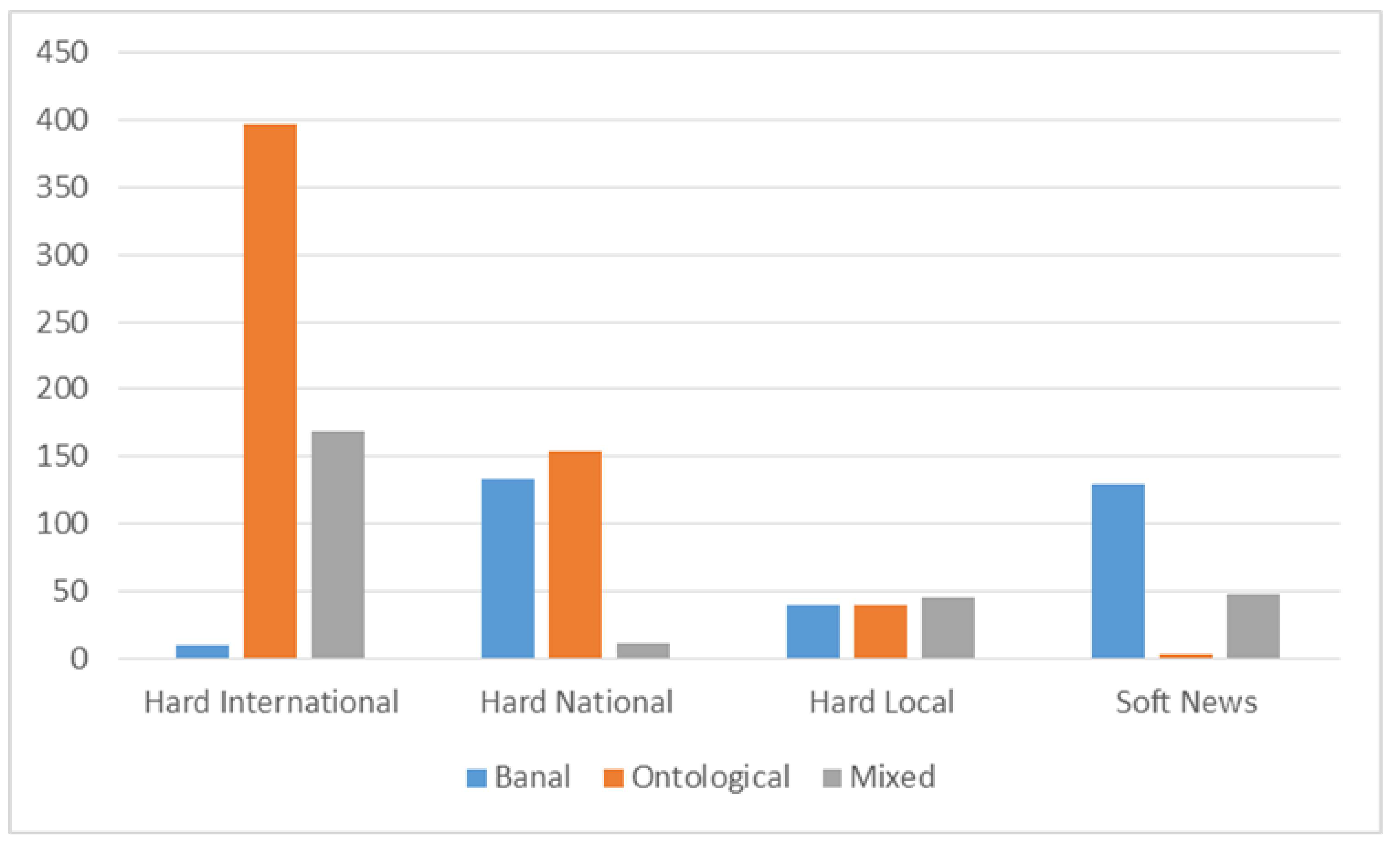

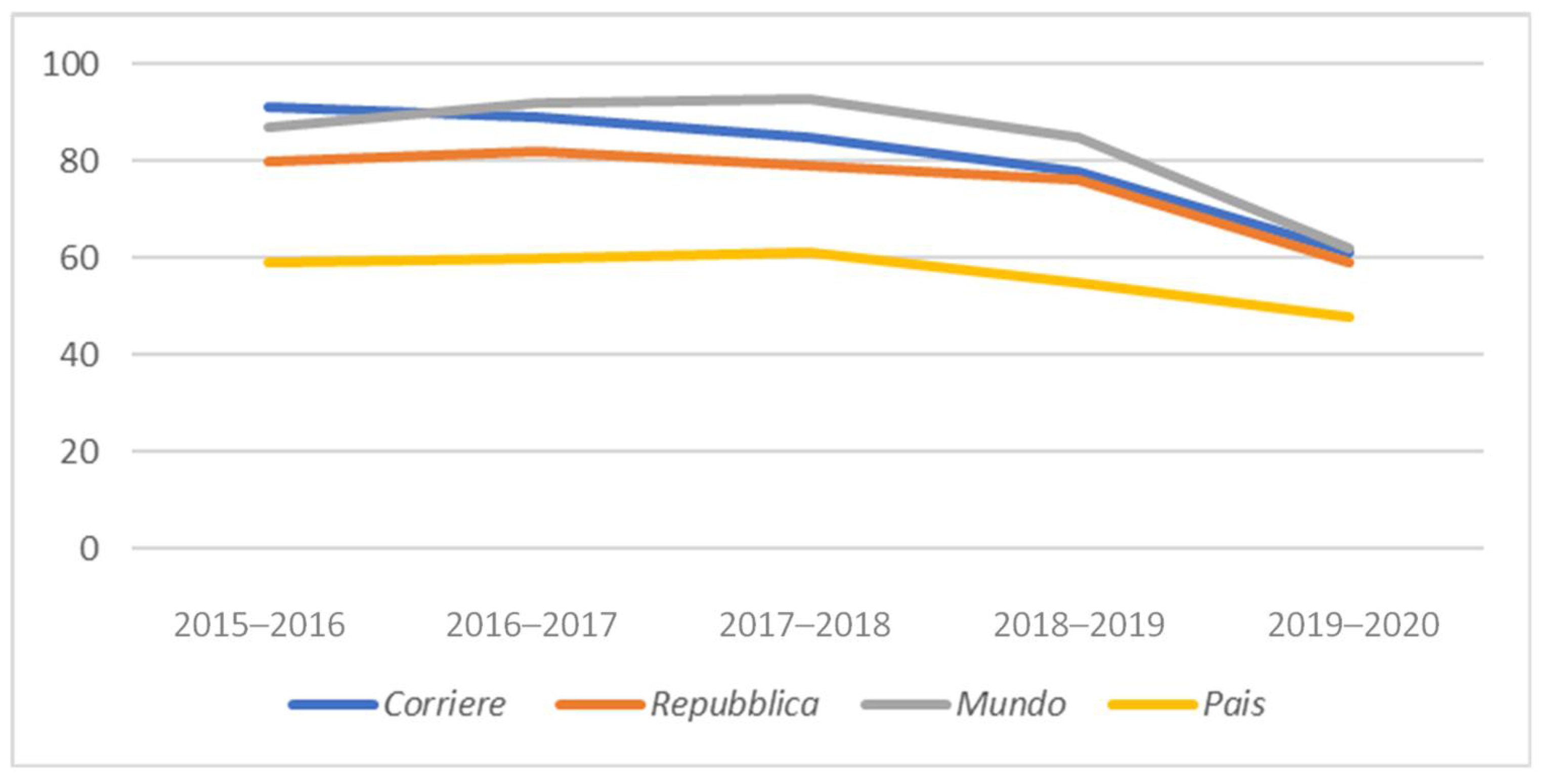

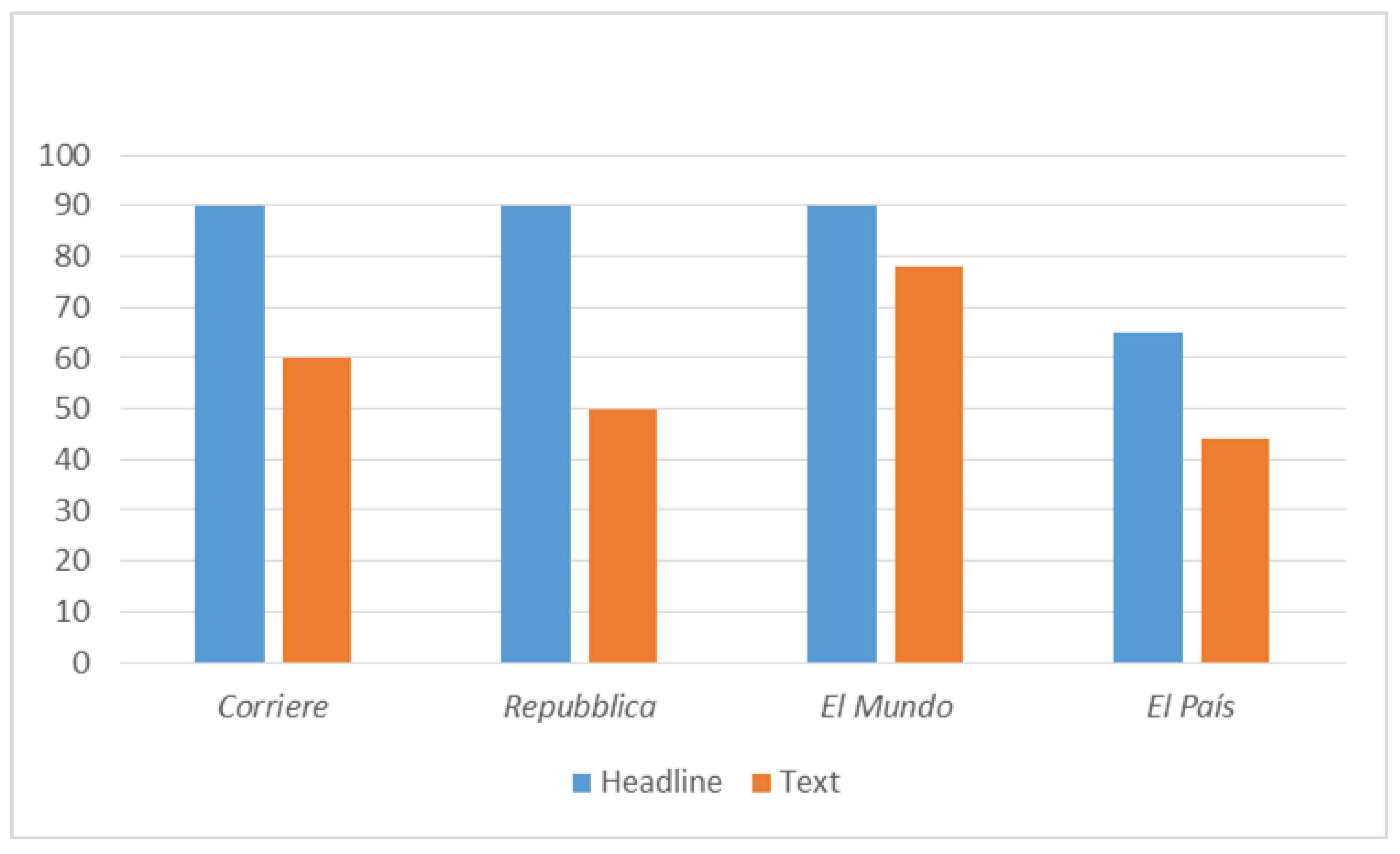

4.1. Quantitative Analysis

4.2. Qualitative Analysis

“Bruxellistan: un mondo a parte chiamato Molenbeek”(“Brusselistan: another planet called Molenbeek”. Raffaele Oriani, La Repubblica. 7th March 2016)

“Le intercettazioni, Maria Giulia Sergio: Papà prendi mamma per i capelli e vieni in Siria”(“The telephone tapping: Daddy, grab mommy by her hair and come to Syria” La Repubblica, 2nd July 2015)

“Lo que esconde la presidenta con ‘burka’ de la mesa electoral”(“What the burqa- president hides” Lucas De La Cal and Ángeles Escrivá, El Mundo, 2nd June 2019)

“Islam e divisa un carabiniere di nome Badar”(“Islam and Uniform: a Carabiniere named Badar”Cristina Palazzo, La Repubblica, 23 June 2019)

“Islam, la sfida delle ragazze”(“Islam, a challenge for girls”. Francesca Caferri, La Repubblica. 25th May 2018)

“Machismo, represión y homofobia: así fueron mis tres meses de experimento en Tinder en un país musulmán “(“Sexism, repression, and homophobia: my three months experiment on Tinder in a Muslim country”. Lucas De La Cal, El Mundo, 7th October 2017)

5. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, Saifuddin, and Jörg Matthes. 2017. Media representation of Muslims and Islam from 2000 to 2015: A meta-analysis. International Communication Gazette 79: 219–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaraz, Antonia, and Malia Politzer. 2020. Islamophobia in the Spanish Press: An analysis of the media coverage of the Charlie Hebdo attacks. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodistico 26: 253. [Google Scholar]

- Alietti, Alfredo, and Dario Padovan. 2013. Religious racism: Islamophobia and antisemitism in Italian society”. Religions 4: 584–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Chris. 2010a. Islamophobia. London: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Chris. 2010b. Fear and loathing: The political discourse in relation to Muslims and Islam in the contemporary British setting. Contemporary British Religion and Politics 2: 221–36. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Chris. 2020. Towards a Working Definition: Islamophobia and Its Contestation. In Reconfiguring Islamophobia. Edited by Christopher Allen. London: Palgrave, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Allievi, Stefano. 2006. How the Immigrant has become Muslim. Public debates on Islam in Europe. Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales 21: 135–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Paul, Costas Gabrielatos, and Tony McEnery. 2013. Discourse Analysis and Media Attitudes. The Representation of Islam in the British Press. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Balibar, Etienne. 1991. Racism and Nationalism. In Race, Nation, Class: Ambiguous Identities. Edited by Etienne Balibar and Immanuel Wallerstein. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Bayrakli, Enes, and Farid Hafez. 2020. European Islamophobia Report 2019. Istanbul: SETA. [Google Scholar]

- Bazeley, Pat. 2010. Computer assisted integration of mixed methods data sources and analysis. In SAGE Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research, 2nd ed. Edited by A. Tashakkori and C. Teddlie. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Beccaro, Andrea, and Stefano Bonino. 2019. Terrorism and Counterterrorism: Italian Exceptionalism and Its Limits. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 2019: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleich, Erik. 2011. What Is Islamophobia and How Much Is There? Theorizing and Measuring an Emerging Comparative Concept. American Behavioral Scientist 55: 1581–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleich, Erik, and A. Maurits van der Veen. 2018. Media portrayals of Muslims: A comparative sentiment analysis of American newspapers, 1996–2015. Politics, Groups, and Identities 9: 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleich, Erik, Hasher Nisar, and Cara Vazquez. 2018. Investigating status hierarchies with media analysis: Muslims, Jews, and Catholics in The New York Times and The Guardian headlines, 1985–2014. International Journal of Comparative Sociology 59: 239–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boomgaarden, Hajo G., and Rens Vliegenthart. 2007. Explaining the rise of anti-immigrant parties: The role of news media content. Electoral Studies 26: 404–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boomgaarden, Hajo. G., and Rens Vliegenthart. 2009. How news content influences anti-immigration attitudes: Germany, 1993–2005. European Journal of Political Research 48: 516–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowe, Brian J., Shaira Fahmy, and Jorg Matthes. 2015. Moving Beyond the Religion Next Door: Valence in News Framing of Islam. Newspaper Research Journal 36: 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo López, Fernando. 2011. Towards a definition of Islamophobia: Approximations of the early twentieth century. Ethnic and Racial Studies 34: 556–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo López, Fernando. 2016. Islamophobia. In The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity and Nationalism. Edited by John Stone, Rutledge M. Dennis, Polly Rizova, Anthony D. Smith and Xiaoshuo Hou. Oxford, Malden and Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, James, and Amanda Haynes. 2015. A Clash of Racializations: The Policing of ‘Race’ and of Anti-Muslim Racism in Ireland. Critical Sociology 41: 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesari, Jocelyne. 2010. Securitization of Islam in Europe. In Muslims in the West after 9/11: Religion, Politics, and Law. Edited by Jocelyne Cesari. London: Routledge, pp. 9–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cesari, Jocelyne. 2011. Islamophobia in the West: A comparison between Europe and the United States. In Islamophobia: The Challenge of Pluralism in the 21st Century. Edited by John Esposito and İbrahim Kalın. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Cervi, Laura. 2019. Similar Politicians, Different Media. Media Treatment of Sex Related Scandals in Italy and the USA. Medijske studije 10: 161–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervi, Laura. 2020. Exclusionary Populism and Islamophobia: A Comparative Analysis of Italy and Spain. Religions 11: 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervi, Laura, and Núria Roca. 2017a. Towards an Americanization of political campaigns? The use of Facebook and Twitter for campaigning in Spain, USA and Norway. Anàlisi 87: 7–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervi, Laura, and Núria Roca. 2017b. La modernización de la campaña electoral para las elecciones generales de España en 2015. ¿Hacia la americanización? Comunicación y Hombre 13: 133–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervi, Laura, and Santiago Tejedor. 2020. S. Framing “The Gypsy Problem”: Populist Electoral Use of Romaphobia in Italy (2014–2019). Social Sciences 9: 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervi, Laura, and Santiago Tejedor. 2021. “Toda África no cabe en Europa”: Análisis comparativo de los discursos de los partidos anti inmigración en España y en Italia. Migraciones. Publicación Del Instituto Universitario De Estudios Sobre Migraciones 51: 207–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, Monica. 2018. The Representation of the “European Refugee Crisis” in Italy: Domopolitics, Securitization, and Humanitarian Communication in Political and Media Discourses. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 16: 161–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, Caroline Mala. 2017. Terrorists Are Always Muslim but Never White: At the Intersection of Critical RaceTheory and Propaganda. Fordham Law Review 86: 455. Available online: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol86/iss2/5 (accessed on 2 June 2021).

- Corral, Alfonso, Cayetano Fernández Romero, and Carmela García Ortega. 2020. Framing & islamophobia. Spanish reference press coverage during the Egyptian Revolution (2011–2013) (2011–2013). Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 77: 373–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, Christopher, Steven Hutchings, Galina Miazhevich, and Henry Nickels. 2012. Islam, Security and Television News. Basingstoke: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Ewart, Jaqui, Kate O’Donnell, and April Chrzanowski. 2018. What a difference training can make: Impacts of targeted training on journalists, journalism educators and journalism students’ knowledge of Islam and Muslims. Journalism 19: 762–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, Steve, and Saher Selod. 2015. The Racialization of Muslims: Empirical Studies of Islamophobia. Critical Sociology 41: 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghauri, Muhammad Junaid, and Salma Umber. 2019. Exploring the Nature of Representation of Islam and Muslims in the Australian Press. SAGE Open 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, Rebecca Ruth. 2019. The Limits of Liberal Inclusivity: How Defining Islamophobia Normalises Anti-Muslim Racism. Journal of Law and Religion 35: 250–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, Fred. 1999. ‘Islamophobia’ reconsidered. Ethnic and Racial Studies 22: 892–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntington, Samuel. 1996. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Imhoff, Roland, and Julia Recker. 2012. Differentiating Islamophobia: Introducing a New Scale to Measure Islamoprejudice and Secular Islam Critique. Political Psychology 33: 811–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khader, Bichara. 2016. Reflexiones sobre la islamofobia ‘ordinaria’. Afkar Ideas 50: 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, Klaus. 2004. Reliability in content analysis. Human Communication Research 30: 411–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, Göran, and Simon Stjernholm. 2016. Islamophobia in Sweden: Muslim Advocacy and Hate-Crime Statistics. In Fear of Muslims? International Perspectives on Islamophobia. Edited by Douglas Pratt and Rachel Woodlock. Heidelberg and New York: Springer, pp. 153–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, Göran, and Åke Sander. 2015. An Urgent Need to Consider How to Define Islamophobia. Bulletin for the Study of Religion 44: 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorente, Javier Rosón. 2010. Discrepancies around the Use of the Term “Islamophobia”. Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge 8: 11. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, Kenan. 2009. From Fatwa to Jihad: The Rushdie Affair and Its Legacy. London: Atlantic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Mamdani, M. 2004. Good Muslim, Bad Muslim. America, the Cold War and the Roots of Terror. New York: Pantheon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Marusek, Sarah. 2018. Inventing terrorists: The nexus of intelligence and Islamophobia. Critical Studies on Terrorism 11: 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzano, Arturo. 2011. Reading the Israeli Palestinian conflict through an Islamophobic prism: The Italian press and the Gaza war. Journal of Arab and Muslim Media Research 4: 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merolla, Jennifer, S. Karthick Ramakrishnan, and Chris Haynes. 2013. “Illegal,” “Undocumented,” or “Unauthorized”: Equivalency frames, issue frames, and public opinion on immigration. Perspectives on Politics 11: 789–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munnik, Michael B. 2017. From voice to voices: Identifying a plurality of Muslim sources in the news media. Media, Culture & Society 39: 270–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, Nic, Richard Fletcher, David. A. L. Levy, and Rasmus K. Nielsen. 2016. Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2016. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson, Connor. 2019. Media portrayal of terrorism and Muslims: A content analysis of Turkey and France. Crime, Law and Social Change 72: 547–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Observatorio de la Islamofobia. 2018. Una Realidad Incontestable: Islamofobia en los Medios. Available online: https://www.iemed.org/publicacions-es/historic-de-publicacions/coedicions/una-realidad-incontestable.-islamofobia-en-los-medios (accessed on 2 June 2021).

- Özyürek, Esra. 2005. The politics of cultural unification, secularism, and the place of Islam in the new Europe. American Ethnologist 32: 509–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. 2019. In the U.S. and Western Europe, People Say They Accept Muslims, but Opinions are Divided on Islam. Available online: https://pewrsr.ch/2IxucPY (accessed on 2 June 2021).

- Rafi, Muhammad Shaban. 2020. Dialogic Content Analysis of Misinformation about COVID-19 on Social Media in Pakistan. Linguistics and Literature Review 6: 131–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragozina, Sofya. 2020. Constructing the image of Islam in contemporary Russian print media: The language strategies and politics of misrepresentation. Religion, State and Society 48: 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, Barry, and Lorraine Brown. 2017. Evidence and ideology: Moderating the critique of media Islamophobia. Journalism Education 6: 12–22. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, Robin. 2009. Islamophobia or anti-Muslim racism—Or what? Concepts and terms revisited. Paper presented at the Conference on Islamophobia and Religious Discrimination: New Perspectives, Policies and Practices, Birmingham, UK, December 9; Available online: http://www.insted.co.uk/anti-muslim-racism.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2021).

- Riffe, Daniel, Stephen Lacy, and Frederick Fico. 2014. Analyzing Media Messages: Using Quantitative Content Analysis in Research, 3rd ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Runnymede Trust. 1997. Islamophobia: A Challenge for Us All. London: Runnymede Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Said, Edward W. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Salaita, Steven George. 2006. Beyond orientalism and Islamophobia—9/11, anti-Arab racism, and the mythos of national pride. CR: The New Centennial Review 6: 245–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, Muniba, Sara Prot, Craig. A. Anderson, and Anthony. F. Lemieux. 2017. Exposure to Muslims in media and support for public policies harming Muslims. Communication Research 44: 841–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaie, M., and B. Malmir. 2017. US news media portrayal of Islam and Muslims: A corpus-assisted Critical Discourse Analysis. Educational Philosophy and Theory 49: 1351–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, A., and A. Ibrahim. 2018. Recent developments in systematic sampling: A review. Journal of Statistical Theory and Practice 12: 290–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyid, S. 2018. Islamophobia and the Europeanness of the Other Europe. Patterns of Prejudice 52: 420–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunar, Lufti. 2017. The Long History of Islam as a Collective “Other” of the West and the Rise of Islamophobia in the U.S. after Trump. Insight Turkey 19: 35–52. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/26300529 (accessed on 17 January 2021). [CrossRef]

- Tarchi, Marco. 2015. Italy: The promised land of populism? Contemporary Italian Politics 7: 273–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejedor, Santiago, Laura Cervi, Fernanda Tusa, Marta Portales, and Margarita Zabotina. 2020. Information on the COVID-19 Pandemic in Daily Newspapers’ Front Pages: Case Study of Spain and Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 6330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, Alberto, and Gary Armstrong. 2012. We Are Against Islam! SAGE Open 2: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull-Dugarte, Stuart. J. 2019. Explaining the end of Spanish exceptionalism and electoral support for Vox. Research and Politics 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, Teun A. 1987. Mediating racism: The role of the media in the reproduction of racism. In Language, Power and Ideology: Studies in Political Discourse. Edited by R. Wodak. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 199–222. [Google Scholar]

- Younes, Zein Bani, Isyaku Hassan, and Mohd Nazri LatiffAzmi. 2020. A Pragmatic Analysis of Islam-related Terminologies in Selected Eastern and Western Mass Media. Arab World English Journal 11: 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Newspaper | Most Mentioned Places | Most Mentioned Organizations | Most Mentioned Individuals |

| Il Corriere della Sera | Siria (356); Italy (264); France (231) Paris (215); Europe (200); USA (198); Iraq (150); Germany (121); Middle East (113); UK (88) | Charlie Hebdo (165); Al Qaeda (158); UN (138); Isis (133); EU (89); Facebook (94); Twitter (69) | Matteo Salvini (123); Pope Francis (98); Maometto (Muhammad) (87); Donald Trump (78) Barack Obama (72); Osama Bin Laden (57); Hillary Clinton (32); Matteo Renzi (29) Magdi Cristiano Allam (21); Vladimir Putin (19) |

| La Repubblica | Siria (300); Italy (264); France (247) Paris (235); Europe (190); Roma (180) USA (168); Iraq (150); Germany (121); Middle East (113) | Charlie Hebdo (145); Al Qaeda (107); UN (101); EU (98); Isis (89); Al Qaeda (82); Facebook (76); Twitter (62) | Donald Trump (161); Barack Obama (142); Papa Francesco (98) Matteo Salvini (97); Angela Merkel (78); Matteo Renzi (57) Osama Bin Laden (47); Abu Bakr (45) Saddam Hussein (34) |

| El País | Siria (387); Spain (301); France (247) Barcelona (212); Europe (190); Israel (180) USA (145); Palestine(131); Germany (121); Raqqa (113) | Charlie Hebdo (185); Al Qaeda (147); UN (131); EU (121); Isis (100); Al Qaeda (92); Police (86); Interpol (62) | Barack Obama (154); Donald Trump (147); Hillary Clinton (138) Angela Merkel (128); Bashar Asad (120) Osama Bin Laden (97) Al Bagdadi (94) |

| El Mundo | Siria (300); Spain (264); Barcelona (247) USA (225); Paris (193); Europe (181) Israel (155); Palestine (150); Germany (121); Madrid (113) | Charlie Hebdo (145); Al Qaeda (107); UN (101); Police (99); EU (98); Isis (89); Al Qaeda (82); CIA (74); Mossad (65) | Donald Trump (177); Barack Obama (154); Hillary Clinton (138) Angela Merkel (128); Bashar Asad (120) Osama Bin Laden (97) Al Bagdadi (94) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cervi, L.; Tejedor, S.; Gracia, M. What Kind of Islamophobia? Representation of Muslims and Islam in Italian and Spanish Media. Religions 2021, 12, 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12060427

Cervi L, Tejedor S, Gracia M. What Kind of Islamophobia? Representation of Muslims and Islam in Italian and Spanish Media. Religions. 2021; 12(6):427. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12060427

Chicago/Turabian StyleCervi, Laura, Santiago Tejedor, and Monica Gracia. 2021. "What Kind of Islamophobia? Representation of Muslims and Islam in Italian and Spanish Media" Religions 12, no. 6: 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12060427

APA StyleCervi, L., Tejedor, S., & Gracia, M. (2021). What Kind of Islamophobia? Representation of Muslims and Islam in Italian and Spanish Media. Religions, 12(6), 427. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12060427