Abstract

This paper focuses on the iconography of “the Listener” in Buddhist prints that was adopted in Joseon dynasty Sakyamuni Preaching paintings. Regarding change in the Listener iconography from bodhisattva form to monk form, diverse research has been conducted on the Listener’s identity and origin. However, existing studies are limited as they fail to consider the circumstances of the time this iconography was first adopted and trends in Joseon Buddhism. As the first Joseon print where the Listener in bodhisattva form appeared was based on a print from the Chinese Ming dynasty, and considering trends in publication of Buddhist prints in China where pictures of the Buddha preaching were used repeatedly in sutras regardless of the contents, this paper argues that the Listener should not be identified with any particular figure and examines the current state and characteristics of Joseon Buddhist paintings where the Listener appears. It also explores the possibility that the Listener’s change from bodhisattva form to monk form was driven by monk artists such as Myeongok, who were exposed to diverse iconography as they participated in creating both Buddhist paintings and prints in a situation where monks who had received systematic education gained a new awareness of iconography.

1. Introduction

While inheriting the traditional style of the Goryeo dynasty, Buddhist paintings of the Joseon dynasty introduced wholly new iconography and developed a uniquely Joseon style. The new iconography exerted wide influence on Buddhist paintings produced for worship purposes throughout the Joseon period, and hence, finding the origin and identifying its significance is of great importance. One aspect that must not be overlooked regarding the new iconography introduced to Joseon Buddhist painting is the adoption of iconography from woodblock print sutras. Sutra illustrations in print form are the visual manifestation of the sutra contents. In some cases, a print was wholly adopted in a painting, and in other cases, some of the individual motifs only. Either way, Buddhist painting was enriched overall.

This paper focuses on the iconography of “the Listener”, who appears in Joseon dynasty paintings titled Sakyamuni Preaching (K. Seokgaseolbeopdo 釋迦說法圖) that were influenced by woodblock print texts. The Listener is generally depicted facing Sakyamuni, sitting with his back to the front. According to the contents of the Lotus Sutra (K. Beophwagyeong 法華經), the iconographic basis for Sakyamuni Preaching paintings, it can be reasonably deduced that the Listener is the disciple Sariputra in monk form receiving the teachings of the Buddha and the prophecy of enlightenment,1 content that appears in the first half of the sutra. However, in early Joseon paintings of Sakyamuni Preaching, the Listener appears not in the form of a monk but a bodhisattva, only later changing to monk form. Naturally, this point has been a subject of study for many researchers. Over a long time, researchers have presented diverse regarding the identity of the Listener icon and its origin.

While many researchers identify the Listener in bodhisattva form as Sariputra based on the contents of the Lotus Sutra rather than the actual appearance of the icon, various other opinions have been presented as well. For example, the first print to feature this iconography was commissioned by a woman of the Joseon royal court, and in this regard, some argue that the patron projected an image of herself onto the Listener in bodhisattva form, which is rather feminine in appearance.2 Moreover, as the name “Maitreya of great compassion” (K. Daeja miruekbosal 大慈彌勒菩薩) is inscribed in the bangje 傍題 (space containing the names of various figures) on the frontispiece illustration for the Sutra on the White Lotus of the True Dharma (K. Daeseung myobeop yeonhwagyeong 大乘妙法蓮華經) published in the Ming dynasty, some researchers have suggested that the Listener is the bodhisattva Maitreya questioning the bodhisattva Manjushri about the miraculous signs of the Buddha, described in the “Introduction of the Lotus Sutra”.3 Yet others have suggested that rather than decisively naming the icon Maitreya, it would be more reasonable to interpret the Listener as representation of the multitude of bodhisattvas listening to Sakyamuni’s sermon.4 However, prior studies overlook the background to the publication of the first Joseon print featuring the Listener in bodhisattva form, such as the fact that it was based on a print from China, and that prints with the same iconography were used in various sutras aside from the Lotus Sutra. Hence, they try to identify the Listener from the iconographic perspective only under the preconception that such prints were produced exclusively as a frontispiece illustration for the Lotus Sutra.

Regarding the source of the iconography for the Listener in monk form, it has been suggested that the side view of Subhuti (a prominent disciple) appearing in Diamond Sutra prints was adopted in Buddha Preaching paintings.5 Another view is that the Listener in monk form may have come from a scene in Seokssi wollyu 釋氏源流 (1673), a book of prints showing the life and activities of Sakyamuni produced at Buramsa Temple 佛岩寺, because the monk artist Beomneung 法能, who had taken part in painting Sakyamuni Preaching at Yeongsusa Temple (1653), participated in carving the woodblocks for the book (Figure 14).6 However, these opinions should be reconsidered. As Subhuti is depicted side on in Diamond Sutra prints, it does not seem likely that this iconography directly influenced the iconography of Sakyamuni Preaching paintings where the Listener is depicted with his back to the front, and the iconography in Seokssi wollyu has many differences to the iconography of Sakyamuni Preaching paintings. Moreover, previous studies vaguely presume that the Listener changed from bodhisattva form to monk form according to the contents of the Lotus Sutra without clearly exploring the background or reasons for such change.

Consequently, rather than trying to identify the Listener through the iconography, this paper explores the meaning of the Listener considering the source of the iconography and trends in the publication of Buddhist prints at the time. Additionally, examining movements in the Buddhist circle as the source of change in the iconography, this paper explores the possibility that monk artists who had worked on Buddhist paintings adopted the new iconography after being exposed to it while working on various Buddhist projects.

2. Iconography of the Listener in Joseon Dynasty Buddhist Paintings for Worship

So far, nine Joseon Buddhist paintings where the Listener icon appears have been identified. He appears in the form of a bodhisattva in five of them and in the form of a monk in four of them. While these paintings are different in their composition of the picture plane, iconography, and other details, except for Assembly of the Trikaya (K. Samsinbulhoedo 三身佛會圖; 1650) from Gapsa Temple 岬寺 in Gongju, they are all Sakyamuni Preaching paintings showing Sakyamuni sitting in the center with the Listener sitting down facing him, back to the front7 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Joseon Sakyamuni Preaching paintings featuring the Listener.

If we examine the introduction of the Listener icon and its process of change based on the works presented in Table 1, the Listener first appeared in Sakyamuni Preaching paintings of the Joseon dynasty during the sixteenth century in the form of bodhisattva. Some examples are the paintings preserved at Seiryoji Temple 淸涼寺 in Kyoto, Japan (1581), at Koshoji Temple 興正寺 in Nagoya, Japan (Figure 1), and the Honolulu Museum of Art in Hawaii.

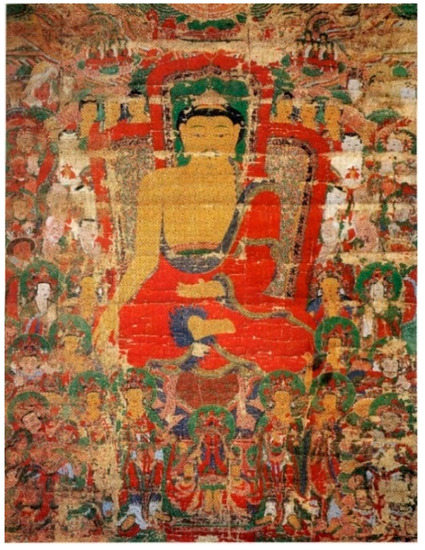

Figure 1.

Sakyamuni Preaching (K. Seokga seolbeopdo), Joseon (16th century), Color on hemp, 278.3 × 276.1 cm, Koshoji Temple in Nagoya, Japan. Photo by Jeong Utaek.

From around the mid-seventeenth century to the first half of the eighteenth century, the Listener began to appear again in large outdoor hanging scroll paintings (K. gwaebul 掛佛) made at temples in Chungcheong-do Province. Among five gwaebul made in this region at the time, two examples—that painted at Bosalsa Temple 菩薩寺 in Cheongju (1649) (Figure 2) and that painted at Gapsa Temple 岬寺 in Gongju (1650) (Figure 3)—follow sixteenth-century tradition with the Listener appearing in bodhisattva form.

Figure 2.

Sakyamuni Preaching, Joseon (1649), Color on hemp and silk, 652.7 × 430.5 cm, Bosalsa Temple (Research Institute of Sungbo Cultural Heritage 2000b, p. 27).

Figure 3.

Assembly of the Trikaya (K. Samsinbulhoedo), Joseon (1650), Color on hemp, 1086 × 841 cm, Gapsa Temple (Research Institute of Sungbo Cultural Heritage 2000a, p. 15).

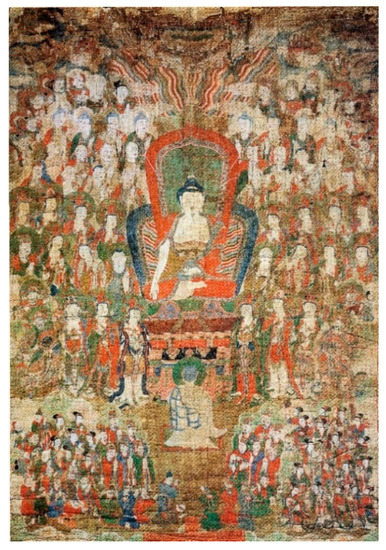

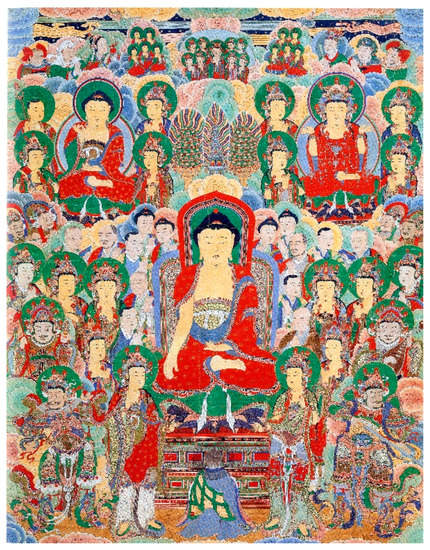

However, just three years later, as seen in Sakyamuni Preaching painted at Yeongsusa Temple 靈水寺 in Jincheon (1653) (Figure 4), the Listener changed from bodhisattva form to monk form. Later, the Listener appears again in monk form in Sakyamuni Preaching painted at Cheongnyongsa Temple 靑龍寺 in Anseong (1658), and Assembly of the Buddha Triad (K. Sambulhoedo 三佛會圖; Sakyamuni, Locana, and Amitabha) painted at Chiljangsa Temple 七長寺 (1710)8 (Figure 5). The Listener icon appears again for the last time in Sakyamuni Preaching painted at Songgwangsa Temple 松廣寺 in Suncheon (1725), but afterward, it seems it never appeared again in a Joseon Sakyamuni Preaching painting.9

Figure 4.

Sakyamuni Preaching, Joseon (1653), Color on hemp, 813 x 554 cm, Yeongsusa Temple (Tongdosa Museum 2008, p. 1).

Figure 5.

Assembly of the Buddha Triad (K. Sambulhoedo), Joseon (1710), Color on hemp, 544 × 422 cm, Chiljangsa Temple (Research Institute of Sungbo Cultural Heritage 2003, p. 39).

3. Origin and Background to the Iconography and Its Adoption in Buddhist Painting

3.1. Introduction of the Listener in Bodhisattva Form and Its Adoption in Buddhist Painting

Based on the above, the question is, “What is the exact identity of the Listener?” Sakyamuni Preaching paintings depict the assembly gathered on Vulture Peak (K. Yeongchuksan 靈鷲山) to hear the teachings of Sakyamuni based on the contents of the introduction to the Lotus Sutra. As such, it is most natural to deduce that the Listener who sits facing Sakyamuni is Sariputra, a disciple who receives the prophecy that he will attain enlightenment along with the teachings of the Buddha. However, in editions of the Lotus Sutra published during Joseon dynasty, the Listener first appeared in bodhisattva form rather than monk form. It was in a woodblock print of the Lotus Sutra dated to 1459 which was published by Gyeonseongam Hermitage 見性庵 (Figure 6) (hereafter the “Gyeonseongam edition”) in Gwangju, Gyeonggi-do Province (today’s Samseong-dong, Seoul), now preserved at Sairaiji Temple 西來寺, Japan. From then until the mid-seventeenth century, the identical iconography was adopted in Buddhist paintings of Sakyamuni Preaching. For this reason, as mentioned in the introduction, many researchers have been interested in why the Listener first appeared in bodhisattva form and presented various opinions regarding the identity of the icon.

Figure 6.

Lotus Sutra (Gyeonseongam edition), published at Gyeonseongam Hermitage, Joseon (1459), Sutra illustration 25.0 × 53.0 cm, Sairaiji Temple, Japan (Dongguk University Museum 2014, p. 39).

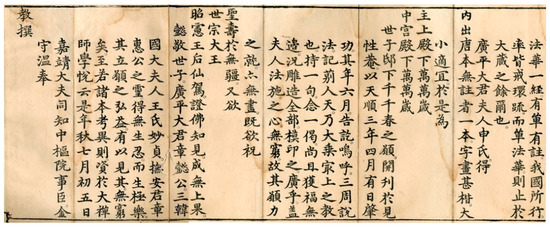

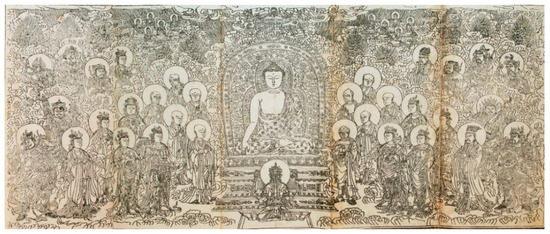

However, as the Gyeonseongam edition adopted intact the iconography of Ming dynasty prints, the question of identity must be examined in relation to woodblock print publication in China at that time. The postscript on the Gyeonseongam edition tells us that it was commissioned by Lady Shin, wife of Prince Gwangpyeong 廣平 (fifth son of King Sejong 世宗). That is, the woodblocks for the print were carved in 1459 at Gyeonseongam Hermitage (Figure 7),10 modeled on a Ming dynasty print published by the imperial court of China. Further, the fact that prints with the same iconography as the Gyeonseongam edition were used as frontispiece illustrations in the Mahaparinirvana Sutra (K. Daebanyeolbangyeong 大般涅槃經) and the Avatamsaka Sutra (K. Hwaeomgyeong 華嚴經) (Figure 8) published in the Ming dynasty shows that the iconography for the Gyeonseongam edition originated in Ming sutra illustrations. The inclusion of sutra illustrations identical to those in the Gyeonseongam edition not only in the Lotus Sutra but also other sutras published during the Ming dynasty provides clues to sorting out the various opinions regarding the identity of the Listener in bodhisattva form found in Lotus Sutra prints. The answer lies in the sutra illustrations found in Chinese Buddhist canons.

Figure 7.

Lotus Sutra, published at Gyeonseongam Hermitage, Vol. 7 Postscript (Dongguk University Museum 2014, p. 25).

Figure 8.

Avatamsaka Sutra, Ming dynasty, private collection. Photo by the author.

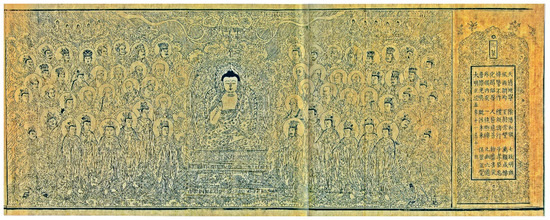

Recent studies have shown that in the Qisha Canon 磧砂藏, Puning Canon 普寧藏 and the Hexizi Canon 河西字大藏經, completed during the Yuan dynasty of China, no more than ten kinds of prints featuring the Buddha preaching in the center surrounded by his attendants were inserted in the text in turn, following the order of the Chinese characters, with no regard for the actual contents of the sutras.11 In light of the nature of Buddhist canons, which require the production of an immense number of woodblock prints at the same time, this was one way of relieving the burden of producing illustrations suited to the contents of each sutra. Prints of the Buddha preaching could be applied to all sutras and hence were commonly used as frontispiece illustrations for many printed sutras from the canon. The same practice continued in the canons published during the Ming dynasty. Among the three Ming dynasty canons, all complete renditions of the Yongle Northern Canon 永樂北藏 (1421–1449) remain and therefore enable changes over time to be accurately traced. All the sutras of the Yongle Northern Canon have a frontispiece illustration in the form of a print of the Buddha preaching, all with the same iconography, indicating that this picture was commonly used to represent many different sutras (Figure 9). This sheds light on why many Chinese woodblock print sutras published from the Yuan dynasty onwards include pictures of the Buddha preaching where the identity of the Listener is not connected with the contents of the sutras concerned. Therefore, considering the background to the publication of woodblock print sutras in China, the Listener in the Gyeonseongam edition, which borrows the iconography of Ming woodblock print editions of the Lotus Sutra, should not be seen as any particular figure but the all-embracing expression and symbolic representation of anyone who receives the Buddha’s teachings.12

Figure 9.

Madhyama Agama Sutra from the Yongle Northern Canon, 5th year of Zhengtong (1440), 38.0 × 13.0 cm, Zhihuasi Temple, Beijing (Beijing Cultural Exchange Museum 2007, pp. 110–11).

In addition, the circumstances in which Buddhist prints of the Ming dynasty were directly transmitted to the Joseon royal court and published in Buddhist sutras of Joseon can be deduced through records regarding the introduction of books from Ming and records about the people who traveled between Ming and Joseon. In the early Ming period, because of the so-called “gate restriction” (Ch. menjin, K. mungeum 門禁) policy13, Joseon had great difficulty importing books from Ming, so any necessary books were obtained either as gifts endowed by the emperor or purchased by envoys when they went on missions to China. The circumstances surrounding the introduction of Buddhist sutras published by Ming can be examined through records: the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty (K. Joseon wangjo sillok 朝鮮王朝實錄) states that during the reign of King Taejong 太宗 “envoys who traveled to Ming brought back Buddhist books endowed by the emperor, including 100 copies of Songs for the Names of Various Buddhas and Bodhisattvas (Ch. Zhu fo Shizun Rulai pusa zunzhe mingcheng gequ 諸佛世尊如來菩薩尊者名稱歌曲) and 300 copies of Biographies of Divine Monks (Ch. Shenseng zhuan 神僧傳)” and also mentions “conflict with Confucian officials during the King Seongjong 成宗 era when the queen dowager commanded that envoys bring back Buddhist sutras from China.”14 In addition, though not an official record, the poetry anthology Chugangjip 秋江集 by the early Joseon Confucian scholar Nam Hyo-on 南孝溫 says, “King Sejo 世祖 sent Kim Su-on 金守溫15 to the Ming capital to obtain Buddhist sutras that had not yet been introduced to Joseon.”16 This record indicates that Kim Su-on, who took a leading role in the publication of Buddhist sutras by the royal court at the time, went to Beijing to obtain sutras from China under royal command. Hence, the fact that envoys brought back Buddhist sutras as they traveled between Joseon and Ming, and that the king directly sent Kim Su-on to procure sutras from China, sufficiently explain how the prints from Chinese sutras were directly adopted in the sutras published by the Joseon royal court.

It was in this context that the Gyeonseongam edition was made as the reproduction (re-carving) of a sutra from the Ming dynasty. Then, four years later, the iconography of the Gyeonseongam edition was used in the frontispiece illustration for the Hangeul (native Korean script) edition of the Lotus Sutra published by Gangyeong Dogam 刊經都監 (Office of Sutra Publication) (1463). Later, it was also used in sutra illustrations for three subsequent editions of the Lotus Sutra commissioned by the royal court and from there spread among Buddhist temples. During the sixteenth century, prints of the same type as the Gyeonseongam edition are seen to have spread from temples such as Gwijinsa 歸眞寺 (1513) and Gwangheungsa 廣興寺 (1527), which reproduced prints produced by the court during the fifteenth century in close connection with the royal family. These prints continued to be reproduced or copied until the eighteenth century. 17

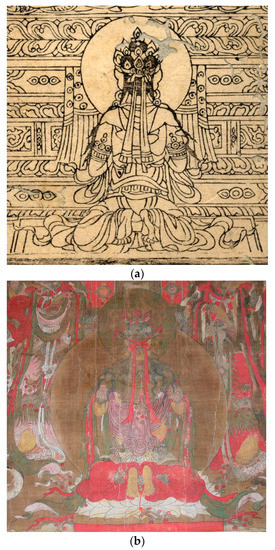

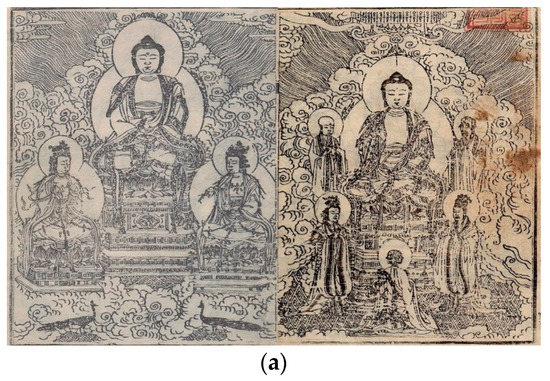

Furthermore, the three Sakyamuni Preaching paintings where the Listener in bodhisattva form first appeared in the sixteenth century are thought to be closely related to court Buddhist paintings from around the mid-sixteenth century considering their rich use of gold paint, the comparatively slim proportions of the figures, and their stylistic characteristics. The artists who produced the Sakyamuni Preaching paintings would have seen this iconography in the Gyeonseongam edition or in reproductions published by temples closely connected with the court. The iconography of the Listener is identical in composition and form in all three paintings mentioned above, being based on the Gyeonseongam edition, but some common differences can be seen in the expression of the attire and the halo (Figure 10). In the prints, the Listener has a halo around the head only, while in all the Buddhist paintings, the Listener has an aureole around the head and body. In addition, unlike the prints, in all the paintings, the skirt of the Listener’s heavenly robes draped in U-shaped folds wraps around the whole body and is tied at the back. Strands of the robes fall under the arms in the prints, while in the paintings, the robes are draped over both arms with the folds falling to either side. Moreover, in the prints, the Listener is sitting on a square cushion-like seat, but in the paintings, he is seated on a lotus pedestal. Considering these differences, therefore, the iconography of the Listener in bodhisattva form in sixteenth-century Sakyamuni Preaching paintings may have been influenced by the basic posture and arrangement of the Listener in prints. However, in details such as the clothing, halo, and pedestal, the method of expression is clearly different and unique to Buddhist paintings.

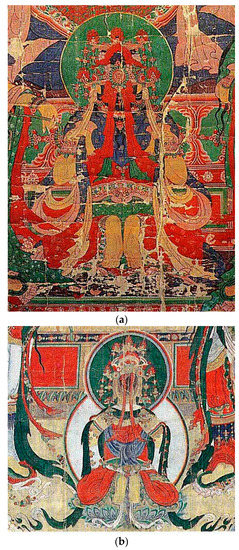

Figure 10.

The Listener iconography from (a) the Lotus Sutra published by Gyeonseongam Hermitage; (b) 16th-century Sakyamuni Preaching. Arranged by the author.

In contrast to the three sixteenth-century paintings, which share a common style, the seventeenth-century paintings Sakyamuni Preaching from Bosalsa Temple (1649) and Assembly of the Trikaya from Gapsa Temple (1650), produced only one year apart and in regions not far removed, are clearly different in type (Figure 11). First, the Bosalsa painting is the only example of a Buddhist painting featuring the Listener with a halo around the head only, as in the print in the Gyeonseongam edition. Moreover, in the attire and absence of a lotus pedestal, it seems to have greater affinity with the print than the aforementioned sixteenth-century Sakyamuni Preaching paintings. In contrast, in the Gapsa painting, the aureole, attire, and lotus pedestal all follow the method of expression seen in sixteenth-century Sakyamuni Preaching paintings. As different types of iconography were evidently produced around the same time, it can be presumed that the iconography in prints of the same type as the Gyeonseongam edition and the Listener in bodhisattva form commonly seen in sixteenth-century paintings of Sakyamuni Preaching were both transmitted to monk artists.

Figure 11.

The Listener iconography in (a) the Sakyamuni Preaching from Bosalsa Temple; (b) Assembly of the Trikaya from Gapsa Temple. Arranged by the author.

3.2. Adoption of the Listener in Monk Form and Changes

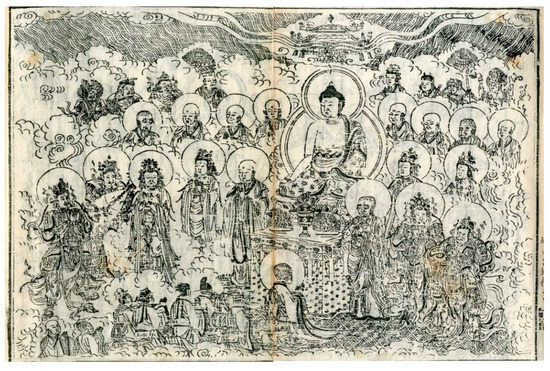

The iconography of the Listener in bodhisattva form which had been introduced to Joseon Buddhist paintings began to change to monk form from around the mid-seventeenth century. The reasons for this can be surmised from movements in the Buddhist circle at the time and trends in the publication of Buddhist texts. Regarding publication trends at temples during the first half of the Joseon period, taking 1520 as the baseline, publication of texts at temples gradually increased until 1550 and thereafter surged dramatically in number. As for the type of text, the focus was on publication of books for the education and training of monks.18 This indicates that systematic education of monks had been implemented, or in other words, a large number of monks received systematic education through these books. Then, from the seventeenth century, it is presumed that in Buddhist art, partial changes were made to the iconography of existing Buddhist prints and paintings thanks to these educated monks. The representative case would be Lotus Sutra prints. Among those from the seventeenth century, there are some where the existing frontispiece illustration for the Diamond Sutra (K. Geumgangyeong 金剛經) was adopted intact or with slight changes. The Songgwangsa Temple 松廣寺 edition (1607) (Figure 12) is the earliest example featuring exact reproduction of the frontispiece illustration of the Diamond Sutra.

Figure 12.

Lotus Sutra, published at Songgwangsa Temple, Joseon (1607), 26.7 × 19.5 cm, Dongguk University Library. Photo by the author.

The Neunginam Hermitage 能仁庵 edition of the Lotus Sutra (1604) at Ssanggyesa Temple 雙溪寺 in Hadong and the Cheonggyesa Temple 淸溪寺 edition (1622) (Figure 13) generally follow the iconographical composition of the Diamond Sutra print but show change in the mudra (hand gesture) of the principal icon from the earth-touching mudra to holding a flower in the hand. Such changes in the Buddha’s hand gesture represent visualization of the theory of seongyo ilchi 禪敎一致, meaning the congruence of the Seon 禪 and Gyo 敎 schools of Buddhism in the first half of the seventeenth century, through Lotus Sutra prints. This is seen as the result of combining the iconography of the Lotus Sutra, held important by the Gyo School, with the iconography of the Buddha holding a lotus flower, which is a symbol of the Seon school (indicating transmission of the dharma by holding up a flower, that is, through the mind rather than words).19 It is notable that the list of donors at the back of the Neunginam edition, where this altered iconography first appeared in 1604, includes the name “Great Seon Master Seonsu”. This refers to Buhyu Seonsu 浮休善修 (1543–1615), leader of the Buhyu lineage, one of the two major lineages of the Seon school of Buddhism during the latter half of the Joseon dynasty. Further, the carved inscription “Gakseong gyo 覺性 校” in the lower part of title of Fascicle 7 tells us that Buhyu Seonsu’s disciple Byeogam Gakseong 碧巖覺性 (1575–1660) also took part in proofreading this sutra.20 Therefore, it is possible that during publication of the Neunginam edition, under the lead of leading scholar monks of the Buhyu lineage, the iconography of the sutra illustrations was changed to reflect changes in Buddhist trends at the time. Consequently, in the same context, adoption of the Listener in monk form, which appeared in Diamond Sutra prints, in Lotus Sutra prints can be seen as the result of shared critical awareness among monks who had received systematic education and believed that in terms of iconography, it was not right for a bodhisattva to appear as the Listener in Lotus Sutra prints instead of the monk Sariputra.

Figure 13.

Lotus Sutra, published at Cheonggyesa Temple, Joseon (1622), 20.2 × 13.5 cm, private collection. Photo by the author.

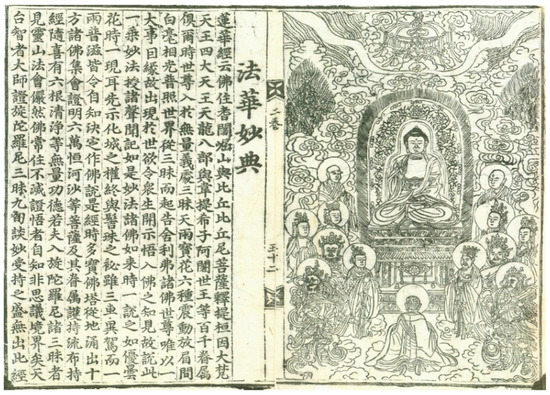

Moreover, reflecting circumstances in the Buddhist world, in Buddhist paintings, the Listener began to change from bodhisattva form to monk form starting with the large outdoor hanging painting of Sakyamuni Preaching at Yeongsusa Temple (1653). Regarding the iconographic source for the Listener in monk form, there are some Ming dynasty prints where the Listener is depicted in monk form rather than bodhisattva form. However, no evidence has been found for transmission of this iconography from China to Korea, and as the expression of details in Ming prints shows differences with the Joseon iconography, it seems reasonable to conclude that the iconography of the Listener in monk form emerged within Joseon. The most valid opinion presented in previous studies is that the monk artist Beomneung 法能, who had taken part in painting Sakyamuni Preaching at Yeongsusa Temple (1653), may have adopted the iconography of the Listener with back to the front from a scene in Seokssi wollyu 釋氏源流 (1673) at Buramsa Temple 佛岩寺, whose woodblocks he took part in carving (Figure 14).21

Figure 14.

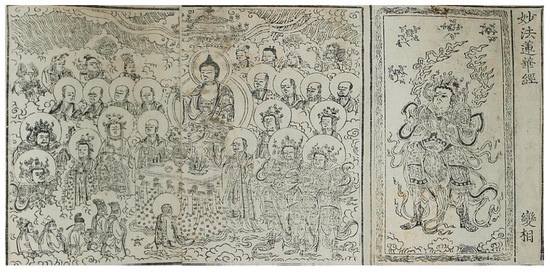

Seokssi wollyu, “Beophwa myojeon 法華妙典” Vol. 2, published at Buramsa Temple, Joseon (1673), private collection. Photo by the author.

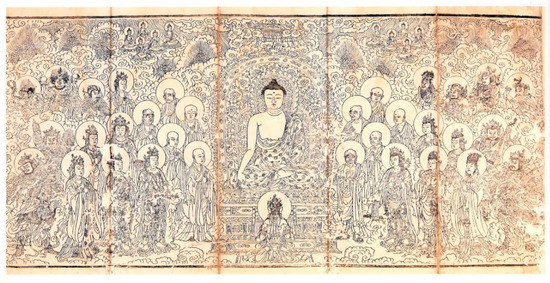

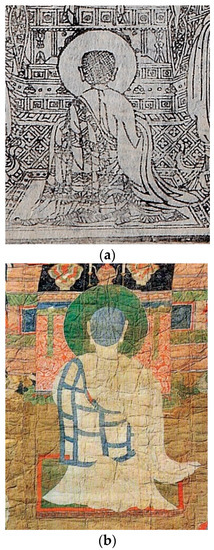

However, because of the many differences in details, it is hard to conclude that the iconography of the Listener in Seokssi wollyu was directly adopted in paintings. In this light, if we focus on the details of form, expression of the Listener in monk form in seventeenth-century Preaching Buddha paintings has greater affinity with the iconography in the Lotus Sutra print published at Gongsanbonsa Temple 公山本寺 (hereafter the “Gongsanbonsa edition”) than Seokssi wollyu. This print was made from four printing woodblocks (1531) (Figure 15). It was frequently published in later times in diverse ways, either from exact reproductions of the four original woodblocks, or mixed with other sutra illustrations, or from partially re-carved woodblocks, or partially adopted as a frontispiece illustration for other sutras. Lotus Sutra prints featuring the same type of iconography as the Gongsanbonsa edition that were made before the mid-seventeenth century, when the Listener in monk form appeared in Buddhist paintings, are listed in Table 2.

Figure 15.

Lotus Sutra (Gongsanbonsa edition), published at Gongsanbonsa Temple, Joseon (1531), 25.5 × 21.0 cm, ((a) first woodblock print; (b) second woodblock print; (c) third woodblock print; (d) fourth woodblock print), private collection. Photo by the author.22

Table 2.

Joseon Lotus Sutra print editions featuring the Listener in monk form (before the mid-seventeenth century).

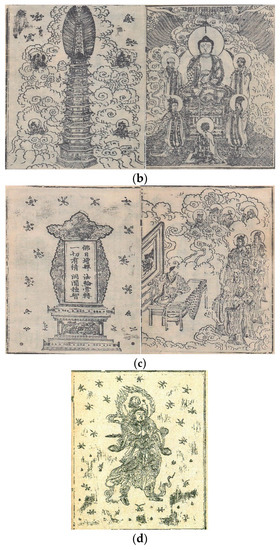

Sakyamuni Preaching prints of the Gongsanbonsa type show Sakyamuni sitting on a lotus pedestal and the Listener in monk form sitting in front of him, with back to the front of the painting. The Listener in monk form has a halo around the head only and is sitting on a square cushion dressed in a kasaya with the vertical strips expressed. Based on these features, some direct connection can be presumed with Sakymuni Preaching paintings from Yeongsusa Temple (1653) and Cheongnyongsa Temple (1683), where the Listener in monk form first appeared (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

Iconography of the Listener in (a) the Lotus Sutra, published at Gongsanbonsa Temple; (b) Sakyamuni Preaching from Yeongsusa Temple. Arranged by the author.

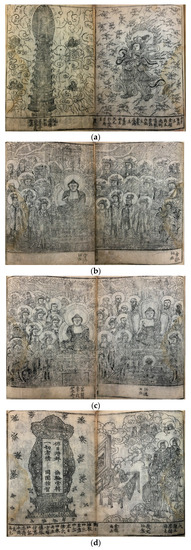

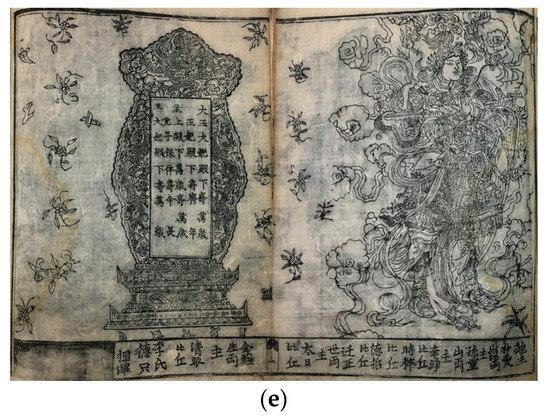

If so, then how did the iconography of such woodblock print texts come to be adopted in Buddhist paintings produced in Chungcheong-do Province in the seventeenth century? As shown in Table 2, there is no known case of a woodblock print text of the Gongsanbonsa type being published in Chungcheong-do Province before the mid-seventeenth century, and it is not known if the Gongsanbonsa edition existed in the region. However, a notable work in this regard is the Lotus Sutra published (1670) by Gapsa Temple 岬寺 in Gongju (hereafter the “Gapsa edition”) (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

Lotus Sutra (Gapsa edition), published by Gapsa Temple, Joseon (1670), 16.7 × 25.4 cm, ((a) first woodblock print; (b) second woodblock print; (c) third woodblock print; (d) fourth woodblock print; (e) fifth woodblock print), Jangseogak Archives. Photo by the author.

The frontispiece illustration for this text was made from five woodblocks and is a diverse mixture of the iconography of the Gongsanbonsa edition and prints from various other sutras. The first woodblock contains the scene of Skanda and the appearance of a pagoda from the Gongsanbonsa edition; the second and third woodblocks the Assembly of the Buddhas of the Three Ages (K. Samsebulhoedo 三世佛會圖; Sakyamuni, Amitabha and Bhaishajyaguru) from the Lotus Sutra published at Gaeheungsa Temple 開興寺 in Boseong (1649) and at Seonamsa Temple 仙岩寺 in Suncheon (1660); the fourth woodblock shows scenes of sutra translation and ancestral spirit tablets from the Gongsanbonsa edition; and the fifth woodblock features iconography adopted from the forms of Skanda and ancestral spirt tablets from the Sutra on Contemplation of Amitayus (K. Gwanmuryangsugyeong 觀無量壽經) published at Seokdusa Temple 石頭寺 (1558) and Silsangsa Temple 實相寺 (1611). As such, the composition is larger than that of any other extant Lotus Sutra print. Moreover, the postscript at the end of the Gapsa edition of the Lotus Sutra gives a detailed account of its publication. To sum up the contents, although there were many temples in Chungcheong-do Province, they had few sutras in their possession, even at Gapsa Temple, which was the central temple of the region; thus, under the lead of monks Solmae 雪梅 and Doseong 道性, artisans were gathered and funds raised to carve eight kinds of sutras on some 700 woodblocks.23 The postscript reveals that a major project to publish the sutras took place at Gapsa Temple.

The question is why a print with such diverse iconography was made for this edition of the Lotus Sutra. Because it is modeled on the Lotus Sutra published at Muryangsa Temple 無量寺 (1493), which has no illustrations, it appears that the monks in charge combined illustrations from sutras already existing in the Gapsa Temple collection and created a new composition. From this, it can be deduced that Gapsa Temple had a large collection of woodblock print sutras with diverse iconography, including not only the Lotus Sutra of the Gongsanbonsa type, but also the Lotus Sutra featuring the Assembly of the Buddhas of the Three Ages and the Sutra on Contemplation of Amitayus published in Jeolla-do Province.

Most notably, a list of the names of artisans who carved the woodblocks recorded in the imprint (gangi 刊記: the inscription giving the details of the woodblock) of the text features the “artist monk Myeongok 明玉”, who took the lead in painting Sakyamuni Preaching at Yeongsusa Temple and at Chongnyongsa Temple. This is a very important piece of evidence attesting in part to the fact that artist monks active in Chungcheong-do Province were mobilized to take part in carving the woodblocks for the great sutra publication project of Gapsa. In addition, it was mentioned above that the monk artist Beomneung, who took part in painting Sakyamuni Preaching at Yeongsusa Temple and Cheongnyongsa Temple with Myeongok, also participated in making Seokssi wollyu (1673). These points once again confirm that Myeongok, Beomneung, and other artist monks active in Chungcheong-do Province took part in producing Buddhist paintings and also directly carved woodblocks for sutra publication projects. While moving from one temple to another to take part in different projects, they would have come into contact with the diverse sutra editions kept at each temple or learned of varied iconography through exchange with others carving the printing woodblocks with them. In this context, although the Gapsa edition was made later than the Yeongsusa and Cheongnyongsa Sakyamuni Preaching paintings, it is highly likely that monk artists such as Myeongok had seen the Gongsanbonsa edition before participating in the production of the Gapsa edition. Hence, changes in the iconography of the Listener appearing in Sakyamuni Preaching paintings are considered to be the result of artist monks such as Myeongok, who had seen sutra illustrations where the Listener appears in monk form as in the Gongsanbonsa edition, adopting the same iconography in Sakyamuni Preaching paintings after the mid-sixteenth century, when a critical view of the form of the Listener was shared by monks who had received systematic education in the Buddhist sutras.

4. Conclusions

Among Joseon dynasty Buddhist paintings, there are some that adopt in various ways the iconography of prints from contemporaneous woodblock print sutras to create a richer picture. In the case of the Listener appearing in Sakyamuni Preaching paintings, the change from bodhisattva form to monk form has been the subject of study for many researchers. However, the interpretations offered so far have explored the issue from the iconographic perspective only, failing to take a comprehensive approach that includes issues such as the background to the iconography when it was first adopted and changes in iconography according to movements in the Buddhist circle at the time.

During the Joseon dynasty, the iconography of the Listener in Sakyamuni Preaching paintings first appeared in bodhisattva form in the print of the Lotus Sutra published at Gyeonseongam Hermitage (1459, Gyeonseongam edition), which was commissioned by Lady Shin, wife of Prince Gwangpyeong. It was first adopted in Buddhist paintings in the sixteenth century and continued to be used until the first half of the seventeenth century. Considering that the Gyeonseongam edition in which this iconography appeared was modeled on Ming dynasty editions of the Lotus Sutra, and that among extant Ming dynasty prints, the identical iconography is found in the frontispiece illustrations of sutras other than the Lotus Sutra, this author judged that the first task was to examine the sutra publication trends of the Ming dynasty. Hence, it was found that the repeated use of prints of the Buddha preaching throughout the Yuan and Ming Buddhist canons regardless of the content of the sutras indicated that the Listener in bodhisattva form is not the expression of a particular figure based on any particular sutra but a symbolic figure representing all those listening to the Buddha’s sermons.

In addition, this iconography first appeared in Joseon Buddhist painting in three Sakyamuni Preaching paintings dating to the sixteenth century. Making rich use of gold paint, they show a close connection with Buddhist paintings commissioned by the court in the comparatively slim proportions of the figures and their stylistic characteristics. For this reason, it is thought the iconography spread from the court. Though the Listener in bodhisattva form appearing in the three paintings has the same composition and form as the Listener in the Gyeonseongam edition, they all show common differences with prints of the Gyeonseongam edition type in terms of their halo or the expression of the pedestal and robes. Hence, it seems a method of expression unique to Buddhist paintings was created, different from what is seen in prints. Additionally, examples of Buddhist paintings from Bosalsa Temple and Gapsa Temple, which adopted the method of expression of Buddhist prints and Buddhist paintings, respectively, show that both methods of expression coexisted and were handed down together until the mid-seventeenth century.

Then, around the mid-seventeenth century, the Listener changed from bodhisattva form to monk form, the reason for this iconographic change presumably based on movements in the Buddhist world and trends in publication of Buddhist texts at the time. The Buddhist circle, which declined somewhat under the suppression of Buddhism following the foundation of the Joseon dynasty, from the sixteenth century gradually began to focus on publication of Buddhist texts for monks’ training and education. This means that a large number of educated and knowledgeable monks were cultivated. Through these monks, from the seventeenth century, changes began to appear in the existing iconography of Buddhist prints and paintings. In the midst of such movements, the Listener in Joseon Buddhist paintings changed from bodhisattva form to monk form, starting with Sakyamuni Preaching from Yeongsusa Temple (1653). Regarding introduction of the iconography of the Listener in monk form, nobody questions the influence of Buddhist woodblock prints, but opinions vary as to exactly which woodblock print sutra provided the motif. In terms of similarity, the iconography adopted in Buddhist paintings seems to have the closest and most direct connection to the Listener depicted in the Lotus Sutra print published by Gongsanbongsa Temple (1531, Gongsanbonsa edition). Furthermore, the existence of the Lotus Sutra published at Gapsa Temple in Gongju (1670, Gapsa edition), which partially adopts the iconography of the Gongsanbonsa edition, confirms that the Listener in monk form spread throughout Chungcheong-do Province, where the same iconography was actively adopted in Buddhist painting. It is particularly notable that the artist monk Myeongok, who took the lead in producing the Sakyamuni Preaching painting at Yeongsusa Temple, the first Buddhist painting to adopt this iconography, and at Cheongnyongsa Temple, also took part in carving the woodblocks for the Gapsa edition of the Lotus Sutra. This is corroborative evidence that artist monks of the time, while taking part in various Buddhist projects, came into contact with the diverse sutra editions kept at each temple or learned about varied iconography through exchange with the artisans who carved the printing woodblocks. Therefore, although the Gapsa edition was produced later than the Sakyamuni Preaching paintings of Yeongsusa and Cheongnyongsa temples, artist monks such as Myeongok who had taken part in various Buddhist projects probably knew of the Gongsanbonsa edition before making the Gapsa edition. That is, the iconography of the Listener in Sakyamuni Preaching paintings changed in a situation where monks who had received systematic education shared a critical view of the form of the Listener, and artist monks such as Myeongok, who had seen prints of the Listener in monk form as in the Gongsanbonsa edition, directly applied the same iconography to Sakyamuni Preaching paintings.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | T 09, 262_01:5b25-02:16b06 |

| 2 | (S. Kim 2007, pp. 95–100). |

| 3 | T 09, 262_01: 02c03. When Sakyamuni reaches the state of samadhi before the assembled crowd miracles began to take place, and the bodhisattva Maitreya asks Manjushri why such things are happening (T. Kim 2008, p. 45). |

| 4 | (S. Lee 2014, pp. 149–50). |

| 5 | (J. Lee 2006, p. 11; S. Kim 2007, pp. 91–95). |

| 6 | (T. Kim 2008, pp. 76–78) |

| 7 | Assembly of the Trikaya from Gapsa Temple is different in iconographic terms as it features the triad of Vairocana, Locana, and Sakyamuni in the center as the principal icon. Nevertheless, in terms of meaning, it can be included in the category of Sakyamuni Preaching paintings based on the doctrine that Sakyamuni is the incarnation of Vairocana. |

| 8 | In this painting, Sakyamuni is large and arranged in the center. To the left and right at the bottom are Locana and Amitabha, respectively, which is why this work is titled Assembly of the Buddha Triad. However, as the inscription clearly identifies it as a painting of the sermon on Vulture Peak and the Listener is placed in the center facing Sakyamuni, this painting can be categorized as a Sakyamuni Preaching painting with the Listener in the center. |

| 9 | For a more detailed discussion of the nine Joseon paintings where the Listener icon appears, see (J. Kim 2018, pp. 38–46). |

| 10 | Postscript of the Lotus Sutra published at Gyeongseonam Hermitage (1459). It includes the phrase “內出唐本” (meaning “book provided by neifu [內府, the imperial household]”), which refers to a book published by the court of Ming China. This means the Gyeongseonam edition was based on the Chinese court edition of the Lotus Sutra. For further details, see (J. Kim 2015, pp. 18–20). |

| 11 | (Weng and Li 2014, pp. 89–95). |

| 12 | (J. Kim 2017, pp. 110–11). |

| 13 | This refers to a set of curfews that prevented Joseon envoys from freely leaving their accommodations and trading with local merchants, implemented because of the private trade and smuggling of embargoed goods by Joseon envoys. (King Sejong the Great Memorial Society 2001, pp. 643–44). |

| 14 | (J. Kim 2015, pp. 33–37); Taejong sillok 太宗實錄, 20th day of the 12th month, 17th year of the reign of King Taejong; Songjong sillok 成宗實錄, 21st and 22nd day of the 1st month of the 2nd year of the reign of King Songjong. |

| 15 | Kim Su-on (1410–1481), the younger brother of monk Sinmi 信眉, had great learning in Buddhism despite being a scholar at Jiphyeonjeon 集賢殿 (Hall of Worthies), a research institute that existed during the reign of King Sejong and played a large role in court-led translation and publication of Buddhist sutras. He wrote the postscript for the Gyeonseongam edition of the Lotus Sutra as well as many other sutras commissioned by royal family members and relatives. |

| 16 | (Nam and Park 2007, p. 197). |

| 17 | For further information on texts published at Gwinjinsa Temple and Gwangheungsa Temple, See (J. Kim 2017, pp. 50–51, 57–58). |

| 18 | (S. Son 2007, pp. 16–17). |

| 19 | (M. Jeong 2004, p. 175); It was possible for the iconography of the Lotus Sutra and the iconography of Buddha holding a lotus flower to be combined in sutra illustrations for the Lotus Sutra because Sakyamuni’s sermon in both cases took place on Vulture Peak. It is thought that the iconography of Sakyamuni holding a lotus flower was published and spread by Seon Master Buhyu Seonsu and the monks of his lineage (Y. Lee 2014, pp. 188–93). |

| 20 | (W. Jeong 2012, pp. 50–51). |

| 21 | (T. Kim 2008, pp. 76–78). As Seokssi wollyu was published 20 years after Preaching Sakyamuni was painted at Yeongsusa Temple, the argument in this paper is based on the fact that the monk artist Beomneung, whose activities centered around Gapsa temple, belonged to the Seosan 西山 lineage, the same lineage as the monk Chunpa 春坡 (the first person in Joseon to receive the Ming woodblock print edition of Seokssi wollyu from Jeong Du-won 鄭斗源, an envoy who had traveled to Ming in 1631). It is likely that Beomneung saw the Ming Dynasty edition of Seokssi wollyu before carving the Buramsa edition. |

| 22 | Images are arranged to reflect their original order from right to left, which is a characteristic of old texts of East Asia. |

| 23 | Postscript of the Lotus Sutra, published at Gapsa Temple (1670). |

References

Primary Sources

Annals of King Taejong (Taejong sillok) 太宗實錄Annals of King Songjong (Songjong sillok) 成宗實錄Nam Hyo-on, Chugangjip 秋江集Lotus Sutra 妙法蓮華經, T 09, no. 262.Lotus Sutra 妙法蓮華經, Published by Gyeonseongam Hermitage, Joseon (1459)Lotus Sutra 妙法蓮華經, Published by Gongsanbonsa Temple, Joseon (1531)Lotus Sutra 妙法蓮華經, Published by Gapsa Temple, Joseon (1670)Secondary Sources

- Beijing Cultural Exchange Museum. 2007. Zhihuasicang yuan mung qing fojing banhua shangxi (智化寺藏元明淸佛經版畵賞析). Beijing: Beijing Yanshan Press (北京燕山出版社). [Google Scholar]

- Dongguk University Museum. 2014. Gakjeukbulsim—The Buddha Mind Carved in Woodblocks (Gakjeukbulsim—Panbone saegin bulsim 刻卽佛心-판본에 새긴 佛心). Seoul: Dongguk University Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, Myeonghee (정명희). 2004. Study on Gwaebul Paintings of the Latter Half of the Joseon Dynasty (Joseon hugi gwaebultaengui yeongu 조선후기 괘불탱의 연구). Korean Journal of Art History (미술사학연구) 242–243: 159–95. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, Wanggeun (정왕근). 2012. Study Joseon Dynasty Woodblock Print Editions of the Lotus Sutra (Joseon sidae myobeop yeonhwagyeongui panbon yeongu朝鮮時代 <妙法蓮華經>의 板本 硏究). Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Library and Information Science, Chung-Ang University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jahyeon (Kim Jahyun 김자현). 2015. Sutra Illustration Prints of Royal Commission of the 15th Century and Introduction of New Iconography (15 segi wangsil balwon byeonsangpanhwawa saeroun dosang yuip 15세기 王室發願 변상판화와 새로운 도상의 유입). Dongak Art History (동악미술사학) 17: 7–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jahyeon (Kim Jahyun 김자현). 2017. Study on Buddhist Sutra Illustration Prints of the First Half of the Joseon Dynasty (Joseon jeongi bulgyo byeonsangpanhwa yeongu 조선전기 불교변상판화 연구). Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Art History, Dongguk University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jahyeon (Kim Jahyun 김자현). 2018. Origin and Adoption of the Listener Iconography Seen in Sakyamuni Preaching Paintings of the Joseon Dynasty (Joseon sidae seokgaseolbeopdoreul tonghae bon cheongmunja dosangui yeonwongwasuyong 조선시대 <석가설법도>를 통해 본 청문자도상의 연원과 수용). Dongak Art Historye (동악미술사학) 23: 37–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Suyeong (김수영). 2007. Study on Joseon Sakyamuni Preaching Paintings of the 16th and 17th Centuries (Joseon 16-17 segi seokga seolbeopdo yeongu, 조선 16-17세기 석가 설법도 연구). Master’s dissertation, Dong-a University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Tae-hyeong (김태형). 2008. Study on Lotus Sutra Illustration Prints of the Joseon Dynasty (Joseon sidae beophwagyeong byeonsang panhwa yeongu조선시대 법화경 변상판화 연구). Master’s dissertation, Dongguk University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- King Sejong the Great Memorial Society. 2001. Dictionary of Korean Classics (Hanguk gojeon yongeo sajeon 한국고전용어사전). Seoul: King Sejong the Great Memorial Society. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Jongsu (이종수). 2006. Gwaebul Painting of Cheongnyongsa Temple in Anseong (Anseong cheongnyongsa gwaebuljeong 安城 靑龍寺 掛佛幀). Tongdosa Museum Special Exhibition of Gwaebul 15: Gwaebul Painting of Cheongnyongsa Temple in Anseong (Anseong cheongnyongsa gwaebuljeong 安城 靑龍寺 掛佛幀). Yangsan: Tongdosa Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Seung-hui (이승희). 2014. Changes in Early Joseon Buddhist Culture Reflected in Prints of Assembly on Vulture Peak (Yeongsanhoesang byeonsangdo panhwareul tonghae bon Joseon chogi bulgyo munhwaui byeonhwa 영산회상도변상도 판화를 통해 본 초기 불교 문화의 변화). Journal of Art History (미술사연구) 28: 135–67. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Yongyun (이용윤). 2014. Study on Buddhist Painting and Monastic Clans of Yeongnam in the Latter Half of the Joseon Dynasty 조선후기 嶺南의 佛畵와 僧侶門中연구). Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Art History, Hongik University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Hyo-on Nam (남효온), and Dae-hyeon Park (박대현), transs. 2007, Korean Translation of Chugangjip (Gugyeok chugangjip 국역추강집). Seoul: Institute for the Translation of Korean Classics, vol. 2.

- Research Institute of Sungbo Cultural Heritage. 2000a. Korean Buddhist Paintings (Hangukui bulhwa 한국의 불화). Seoul: Research Institute of Sungbo Cultural Heritage, vol. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Research Institute of Sungbo Cultural Heritage. 2000b. Korean Buddhist Paintings (Hangukui bulhwa 한국의 불화). Seoul: Research Institute of Sungbo Cultural Heritage, vol. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Research Institute of Sungbo Cultural Heritage. 2003. Korean Buddhist Paintings (Hangukui bulhwa 한국의 불화). Seoul: Research Institute of Sungbo Cultural Heritage, vol. 29. [Google Scholar]

- Son, Seongpil (손성필). 2007. Publication of Buddhist Texts in the 16th Century Joseon Dynasty (16 segi joseonui bulseo ganhaeng 16세기 조선의 불서 간행). Master’s dissertation, Dongguk University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Tongdosa Museum. 2008. Tongdosa Museum Special Exhibition of Gwaebul 20: Gwaebul of Yeongsusa Temple in Jincheon (Jincheon yeongsusa gwaebuljeong 鎭川 靈水寺 掛佛幀). Yangsan: Tongdosa Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, Lianxi, and Hongbo Li, eds. 2014. (翁連溪, 李洪波 主編). Complete Works of Chinese Buddhist Prints (Zhongguo fojiao banhua quanji 中國佛敎版畵全集). Beijing: Zhongguo shudian (中國書店). [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).