Coronavirus-Driven Digitalization of In-Person Communities. Analysis of the Catholic Church Online Response in Spain during the Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The State of the Art

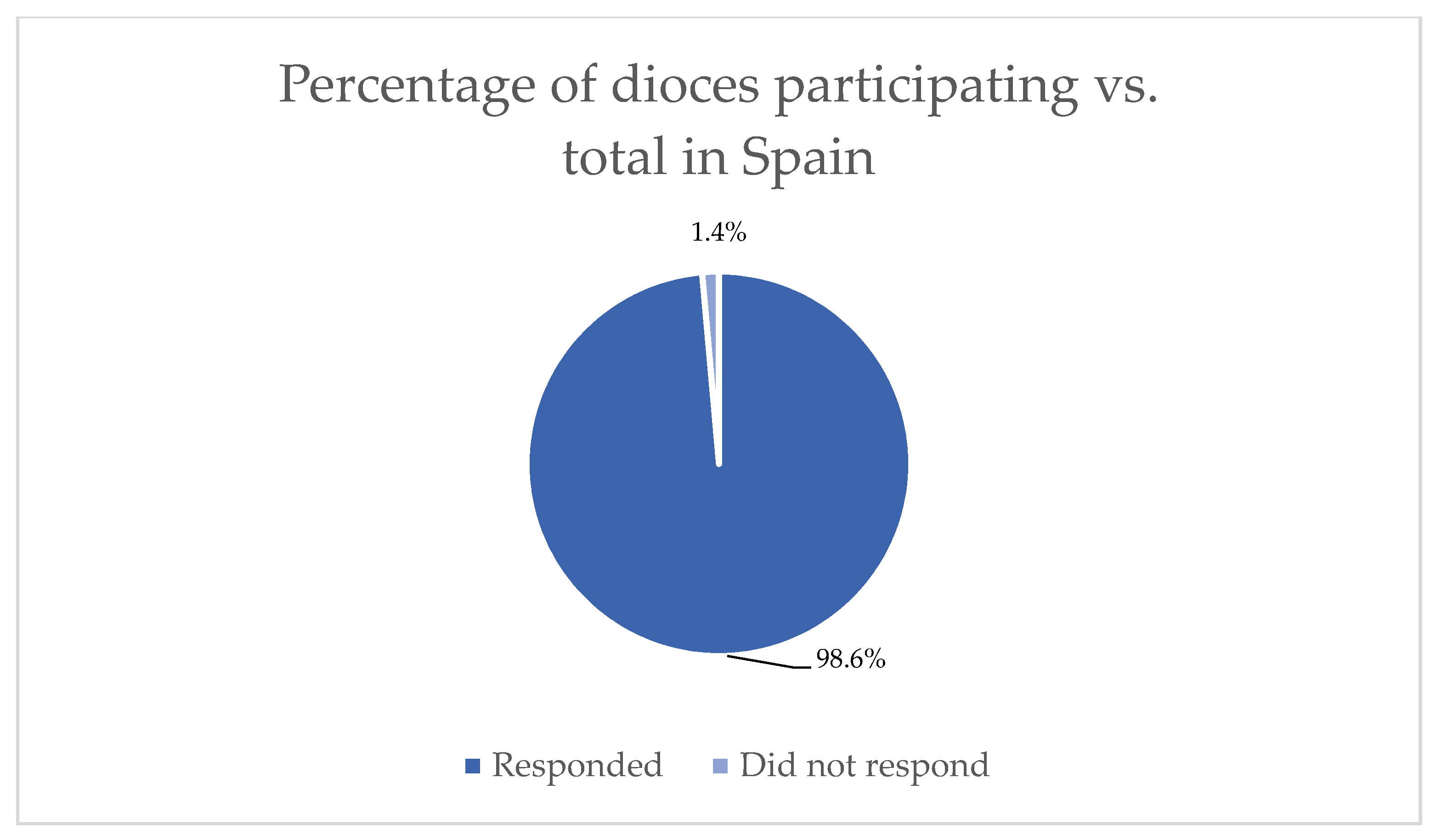

3. Methodology

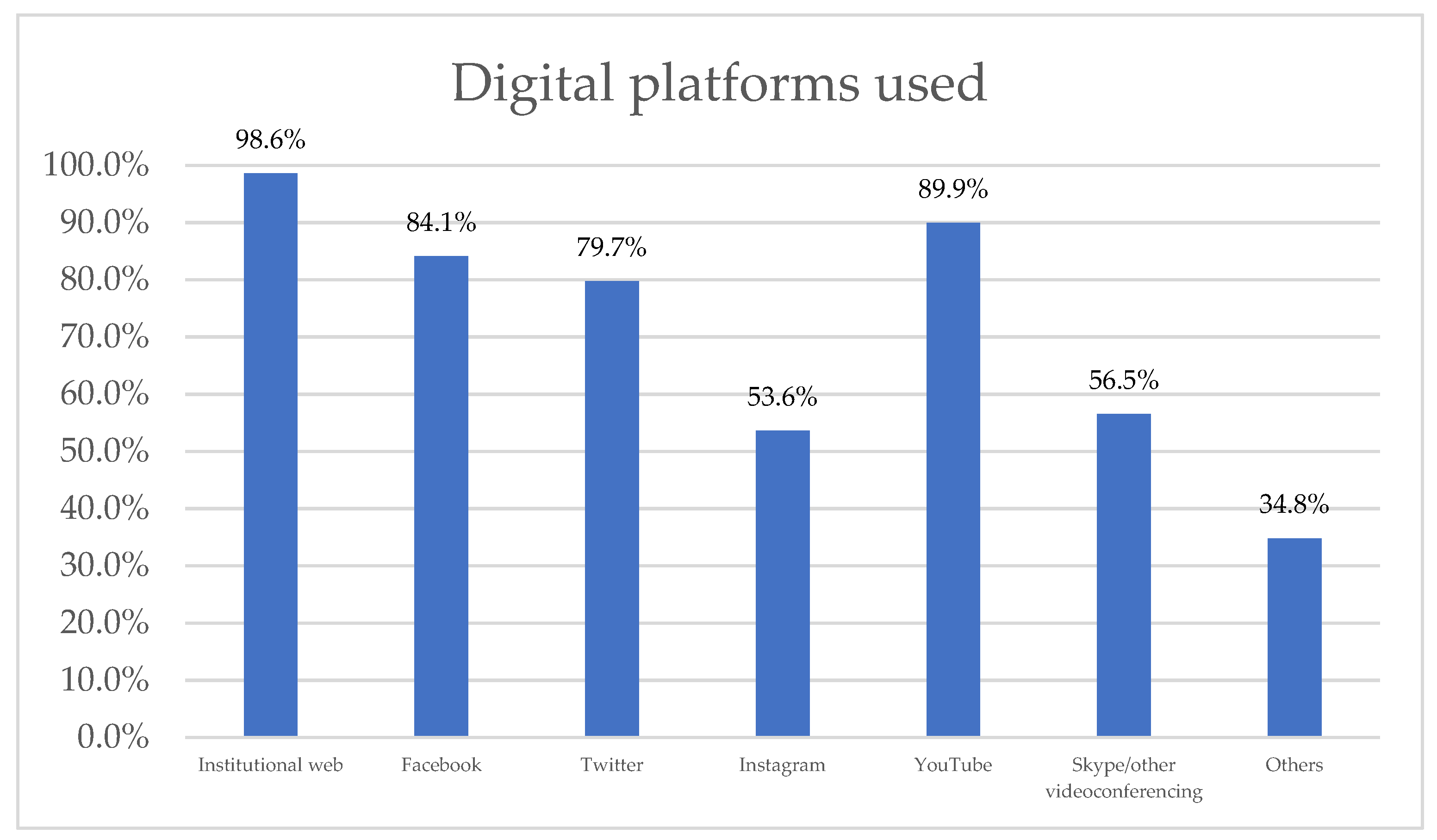

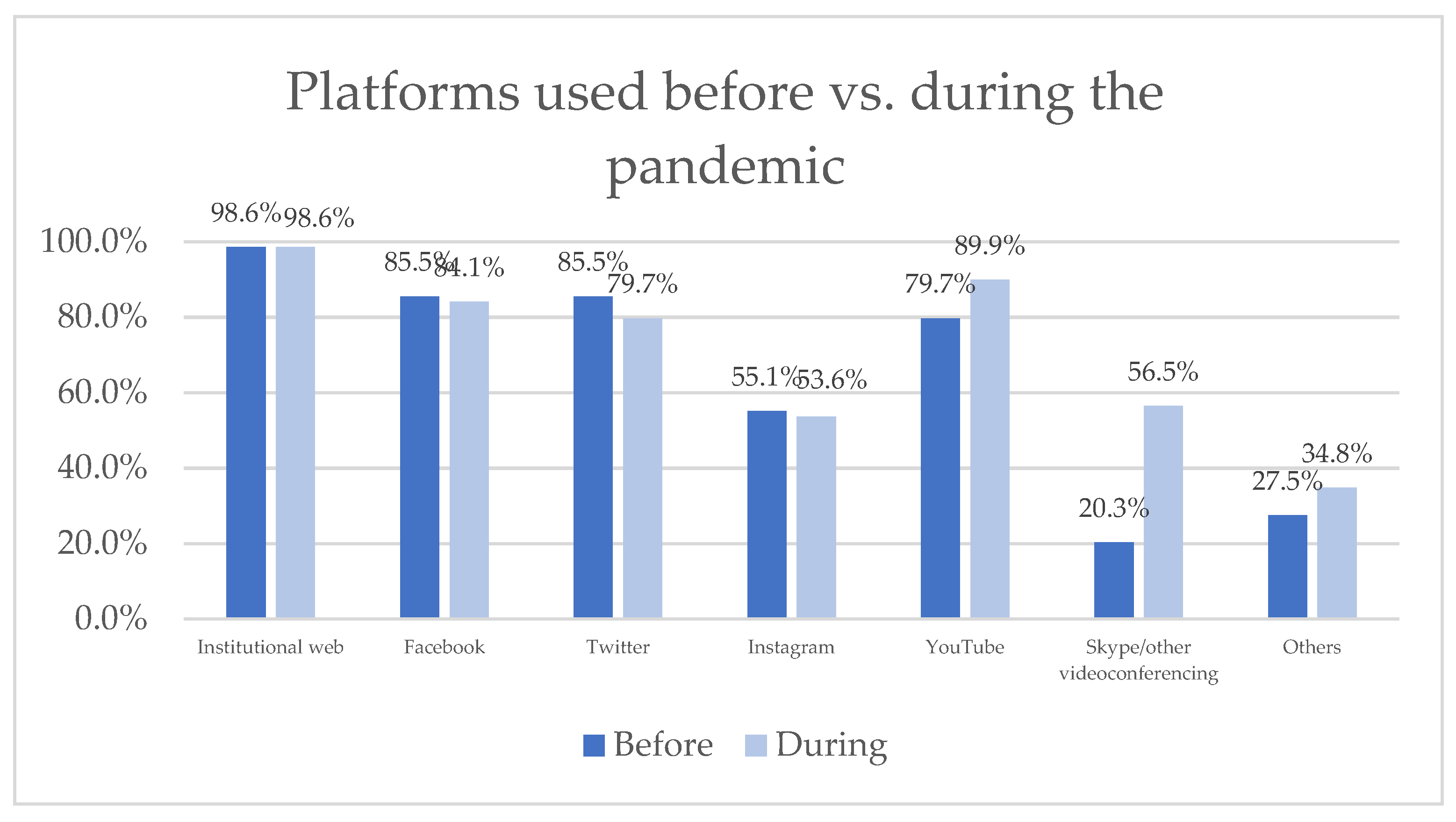

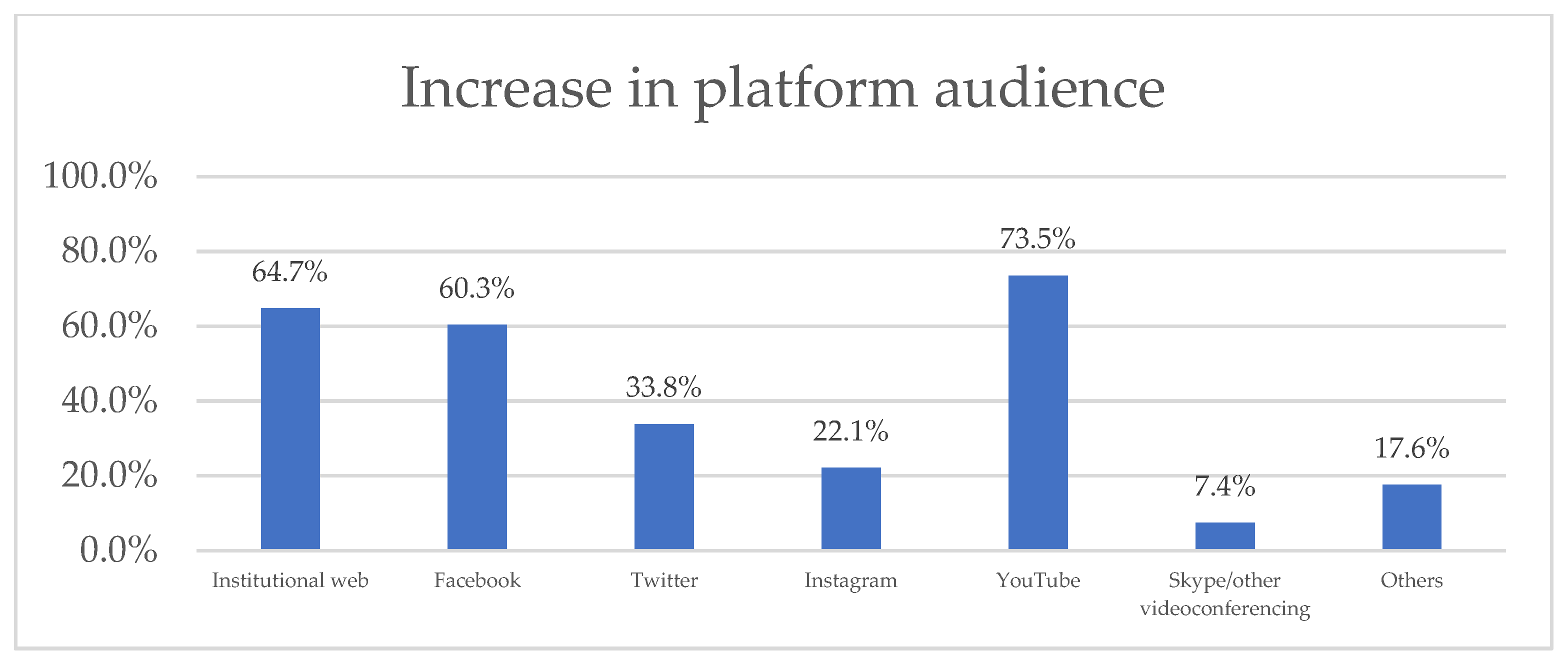

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Respond to believers’ religious needs;

- Be there for everyone, regardless of their religious beliefs;

- Attend to the needs of the media;

- Promote internal communication;

- Support transversal diocesan projects.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire Implemented

- 1. Does your diocese have a Crisis Committee or similar?

Yes, but Communications is not part of it.

Yes, and the Communication department is represented in it.

No, there is no Crisis Committee.

- 2. Has your diocese readjusted its communication activity since the beginning of the state of alarm in Spain caused by the COVID-19 pandemic?

Yes, it has.

No, it has not.

- 3. If yes, have you adapted initiatives and/or tools that were already in use or have new ones been implemented?

We have readapted initiatives and/or tools that we already used.

We have implemented new initiatives and/or tools.

Both the previous two: we have readapted some and implemented new ones.

- 4. Although not all communication services will have been incorporated at the same time, in general terms, how long did it take to adapt the communication strategy to the digital space?

Less than a week.

More than a week.

Less than a month.

More than a month.

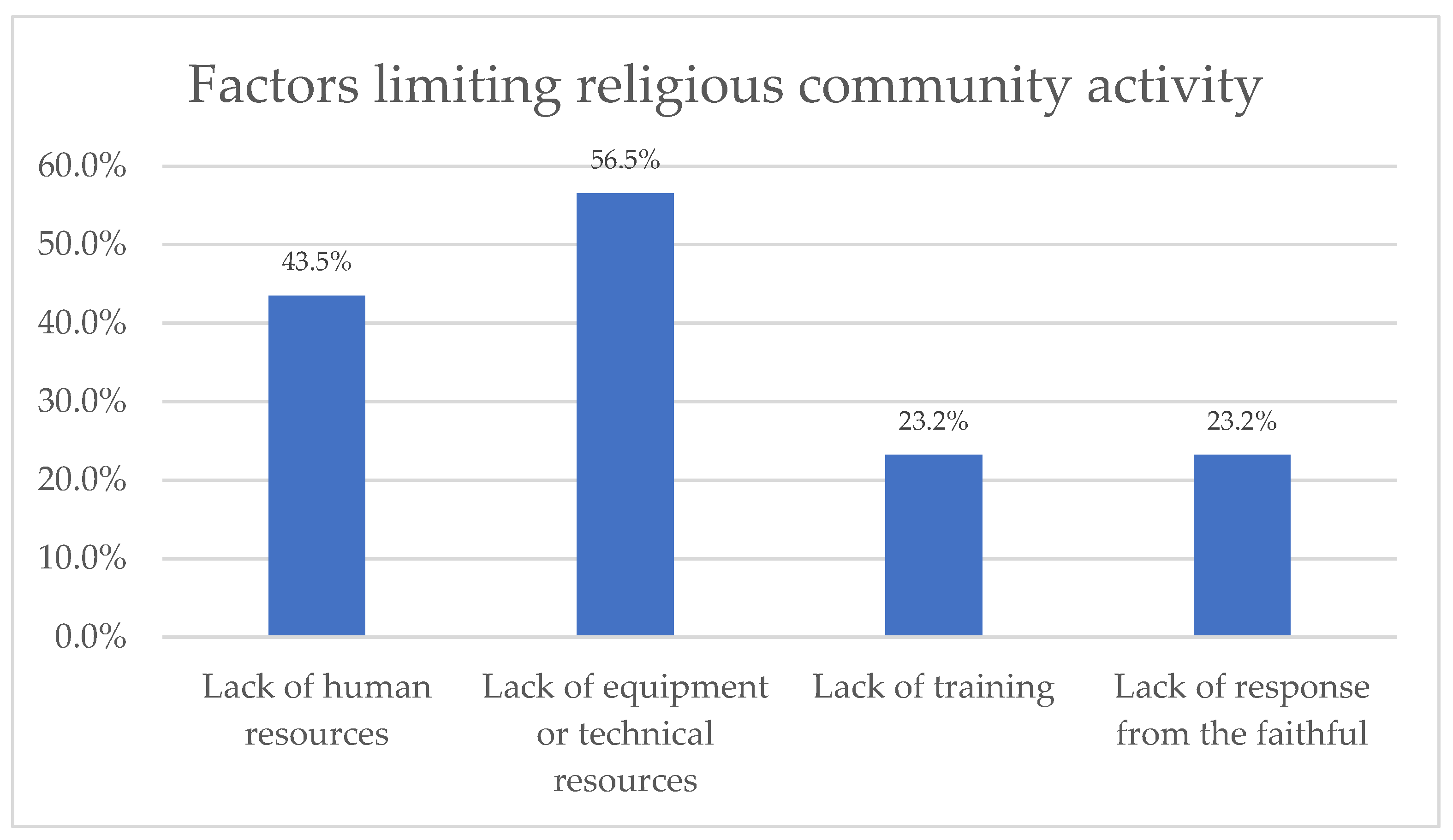

- 5. What difficulties did you encounter in articulating your communicative response? (You can check several options)

Lack of human resources.

Lack of equipment or technical resources.

Lack of training.

Lack of follow-up by parishioners.

Other.

None.

- 6. What platforms have you used? (You can check several options)

Institutional website.

Facebook.

Twitter.

Instagram.

YouTube.

Skype or other video calling systems.

Other.

- 6.1 If you have answered “Others”, could you indicate which ones?

- 7. On what platforms do you usually operate?

Institutional website.

Facebook.

Twitter.

Instagram.

YouTube.

Skype or other video calling systems.

Other.

- 7.1 If you answered “Other”, could you indicate which ones?

- 8. Could you summarize what the communicative response of your diocese has been to this crisis? You can highlight new projects or services, others that have been interrupted or suppressed, the intensification of activity on specific platforms … Please give an open response to what you consider of interest.

- 9. Have you seen your audience increase?

Yes, we have.

No, we have not.

- 10. If you have answered “yes” to the previous question, could you estimate how much it has increased compared to the three months prior to the onset of the crisis? (You can answer by offering an approximate percentage).

- 11. Where has there been the greatest increase? (You can check several options)

Institutional website.

Facebook.

Twitter.

Instagram.

YouTube.

Skype or other video calling systems.

Other.

- 11.1 If you have answered “Others”, could you indicate which ones?

- 12. About the audience profile during this crisis …

They have always been the same readers/users.

They have remained the same readers/users and we have reached new ones.

We have lost regular readers/users, but we have gained new ones.

- 13. If you have reached new users, could you briefly outline the profile/characteristics of those new readers/users?

- 14. Do you think that, after this crisis, any communicative practices of those implemented will remain in your diocese?

Yes, this crisis will improve diocesan communication.

No, it will not.

- 15. Do you think that this crisis has made your diocese, especially the governance team, recognise the importance of having a well-defined communication strategy (solvent and responsive)?

Yes, I do.

No, I do not.

- 16. Beyond your diocese, do you think this crisis could help complete the adaptation of the Catholic Church to the contemporary media context?

Yes, I do.

No, I do not.

References

- Abdel-Fadil, Mona. 2017. Identity Politics in a Mediatized Religious Environment on Facebook: Yes to Wearing the Cross Whenever and Wherever I choose. Journal of Religion in Europe 10: 457–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirregomezcorta, Marta. 2020. La Iglesia pide a sus feligreses que no vayan a misa para evitar la propagación del coronavirus. Niusdiario.es. Available online: https://www.niusdiario.es/sociedad/sanidad/diocesis-iglesia-coronavirus-cierran-templos-no-asistir-misa-domingos_18_2914020046.html (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Arasa, Daniel. 2012. El magisterio de la Iglesia católica sobre la comunicación. In Introducción a la comunicación institucional de la Iglesia. Edited by José María La Porte. Madrid: Palabra. [Google Scholar]

- Augé, Marc. 1994. Los ‘no lugares’. Espacios del anonimato. Una antropología de la sobremodernidad. Barcelona: Gedisa. [Google Scholar]

- Baraybar-Fernández, Antonio, Sandro Arrufat-Martíin, and Rainer Rubira-Garcia. 2020. Religion and Social Media: Communication Strategies by the Spanish Episcopal Conference. Religions 11: 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, Elizabeth. 2020. Will the Coronavirus be the End of the Communion Cup? The New Yorker. Available online: https://www.newyorker.com/news/on-religion/will-the-coronavirus-be-the-end-of-the-communion-cup (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Barrionuevo-Almuzara, Leticia, Eva Estupinyà-Pinyol, Mª Carmen Martín Marichal, Helena Martín-Rodero, Javier Mezquita-Acosta, Brigit Nonó-Rius, and Cristina Vaquer Suñer. 2014. Manual de buenas prácticas en redes sociales. Madrid: CRUE Rebiun. [Google Scholar]

- Beramendi, Ariel. 2016. Apuntes para una pastoral de la comunicación hoy. Los desafíos del nuevo ambiente digital. Bogotá: PPC. [Google Scholar]

- Binder, Melanie. 2020. Online Community Value is Apparent Amid the COVID-19 Outbreak. Healthcare Financial Management Association. Available online: https://www.hfma.org/topics/hfm/2020/may/online-community-value-is-apparent-amid-the-COVID-19-outbreak.html (accessed on 29 March 2021).

- Caldwell, Hellen, and Michelle Bugby. 2018. The use of technology to build digital communities. In Young Children and Their Communities: Understanding Collective Social Responsibility. Edited by Gillian Sykes and Eleonora Teszenyi. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Heidi. 2005. Exploring Religious Community Online. We are One in the Network. New York: Peter Lang Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Heidi. 2012. Understanding the relationship between religion online and offline in a networked society. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 80: 64–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Heidi. 2020. Religion in Quarantine: The Future of Religion in a Post-Pandemic World. Austin: Digital Religion Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Heidi. 2021. Digital Creatives and the Rethinking of Religious Authority. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Heidi, and Stephen Garner. 2016. Networked Theology. Negotiating Faith in a Digital Culture. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Carroggio, Marco. 2012. La oficina de prensa y la relación con los medios. In Introducción a la comunicación institucional de la Iglesia. Edited by José Maróa La Porte. Madrid: Palabra. [Google Scholar]

- Casero-Ripollés, Andreu. 2020. Impact of COVID-19 on the media system. Communicative and democratic consequences of news consumption during the outbreak. El profesional de la información 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, Manuel. 2001. La Galaxia Internet: Reflexiones sobre internet, empresa y sociedad. Barcelona: Plaza y Janés. [Google Scholar]

- Catela, Isidro. 2018. Me Desconecto, Luego Existo. Madrid: Encuentro. [Google Scholar]

- Catela Marcos, Isidro. 2017. La comunicación institucional de la Iglesia. In The Challenges of the Catholic Communicator. Edited by Rafael Ortega and Álvaro de la Torre. Madrid: CEU. [Google Scholar]

- Celia Perera, Ana, and O. Pérez Cruz. 2009. Crisis social y reavivamiento religioso. Una mirada desde lo sociocultural. Cuicuilco 16: 135–57. [Google Scholar]

- Celli, Claudio Maria. 2013. La comunicación de la fe en el horizonte de la nueva evangelización. Catholic.net. Available online: https://goo.gl/d5ov89 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Davidson, Theresa, and Lee K. Farquhar. 2014. Correlations of social anxiety, religion, and Facebook. Journal of Media and Religion 13: 208–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, Lorne, and Douglas Cowan. 2004. Religion Online. Finding Faith on the Internet. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- De la Cierva, Yago. 2014. La Iglesia, casa de cristal. Madrid: BAC. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz Merchán, Gabino. 2017. Evangelizar en un mundo nuevo. Reflexión pastoral sobre la nueva evangelización en España. Madrid: PPC. [Google Scholar]

- Díez-Bosch, Míriam. 2015. Perfil del informador religioso especializado en el Vaticano. Palabra Clave 18: 258–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Bosch, Míriam, Josep-Lluís Micó-Sanz, and Josep-Maria Carbonell-Abelló. 2015. Catholic Communities Online. Barcelona: Blanquerna Observatory on Media, Religion and Culture. [Google Scholar]

- Díez-Bosch, Míriam, Josep-Lluís Micó-Sanz, and Alba Sabaté-Gauxachs. 2018. Construcción de comunidades online a partir de comunidades presenciales consolidadas. El caso de la Iglesia católica en internet. El Profesional de la Información 27: 1699–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolphin, Richard R. 2000. The Fundamentals of Corporate Communication. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Eilers, Franz-Josef. 1994. Communication in Community. Manila: Logos Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Evolvi, Giulia. 2017. Hybrid Muslim identities in digital space: The Italian blog Yalla. Social Compass 64: 220–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentini, B. 2012. Accesso alla rete in corso. Dalla tradizione orale a internet, 2000 anni di storia della comunicazione della Chiesa. Bologna: EDB. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Sara. 2020. Social media use spikes during pandemic. Axios. Available online: https://www.axios.com/social-media-overuse-spikes-in-coronavirus-pandemic-764b384d-a0ee-4787-bd19-7e7297f6d6ec.html (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Francis Pope. 2018. La verdad os hará libres (Jn 8, 32). Fake news y periodismo de paz. Vatican.va. Available online: http://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/es/messages/communications/documents/papa-francesco_20180124_messaggio-comunicazioni-sociali.html (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Gabelas, José Antonio, Carmen Marta-Lazo, and Patricia González-Aldea. 2015. El factor relacional en la convergencia mediática: Una propuesta emergente. Anàlisi. Quaderns de Comunicació i Cultura 53: 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- González, Beatriz. 2020. La crisis del coronavirus reactiva el sentimiento religioso. Uoc.edu. Available online: https://www.uoc.edu/portal/es/news/actualitat/2020/189-crisis-coronavirus-reactiva-religion.html (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Government of Spain. 2020. Real Decreto 463/2020, de 14 de marzo, por el que se declara el estado de alarma para la gestión de la situación de crisis sanitaria ocasionada por el COVID-19. Boletín Oficial del Estado, n. 67. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2020-3692 (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Graham, Gordon. 1999. The Internet: A Philosophical Inquiry. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, Sumeet, and Hee-Woong Kim. 2004. Virtual community: Concepts, implications, and future research directions. Paper presented at 10th America’s Conference on Information Systems, Singapore, April 10. [Google Scholar]

- Guzek, Damian. 2019. Religious memory on Facebook in times of refugee crisis. Social Compass 66: 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, Anders, Simon Cottle, Ralph Negrine, and Chris Newbold. 1998. Mass Communication Research Methods. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Helland, Christopher. 2005. Online religion as lived religion. Methodological issues in the study of religious participation on the internet. Online-Heidelberg Journal for Religions on the Internet 1: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hjarvard, Stig. 2011. The mediatisation of religion: Theorising religion, media and social change. Culture and Religion 12: 119–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtzman, Steven R. 1994. Digital Mantras. The Languages of Abstract and Virtual Worlds. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover, Stewart M. 2006. Religion in the Media Age. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover, Stewart M. 2016. The Media and Religious Authority. University Park: Penn State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover, Stewart M., and Nadia Kaneva. 2009. Fundamentalisms and the Media. New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Igartua, Juan José, Félix Ortega-Mohedano, and Carlos Arcila-Calderón. 2020. Communication use in the times of the coronavirus. A cross-cultural study. El profesional de la información 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, John. 2002. In-depth interviewing. In Handbook of Interview Research: Context and Method. Edited by Jaber F. Gubrium and James A. Holstein. London: Sage, pp. 103–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Amy-Jo. 2000. Community Building on the Web: Secret Strategies for Successful Online Communities. Boston: Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Koeze, Ella, and Nathaniel Popper. 2020. The Virus Changed the Way We Internet. The New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/04/07/technology/coronavirus-internet-use.html (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Kołodziejska, Marta. 2015. How Catholic internet forums are changing Catholicism. The Polish experience. In Catholic Communities Online. Edited by Miriam Díez-Bosch, Josep Lluís Micó-Sanz and Josep Maria Carbonell Abelló. Barcelona: Blanquerna Observatory on Media, Religion and Culture, pp. 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kołodziejska, Marta. 2020. Mediated Identity of Catholic Internet Forum Users in Poland. Journal of Religion, Media and Digital Culture 9: 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porte, José María. 2012. Introducción a la comunicación institucional de la Iglesia. Madrid: Palabra. [Google Scholar]

- Lajoie, Mark. 1996. Psychoanalysis and cyberspace. In Cultures of Internet. Virtual Spaces, Real Histories, Living Bodies. Edited by Rob Shields. London: Sage Publications, pp. 160–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lövheim, Mia. 2004. Intersecting Identities: Young People, Religion, and Interaction on the Internet. Uppsala: Uppsala University Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lövheim, Mia, and Evelina Lundmark. 2019. Gender, Religion and Authority in Digital Media. Essachess: Journal for Communication Studies 12: 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenthal, Patrick, Jared Borup, Richard West, and Leanna Archambault. 2020. Thinking Beyond Zoom: Using Asynchronous Video to Maintain Connection and Engagement During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education 28: 383–91. [Google Scholar]

- Lundmark, Evelina. 2019. “This is the Face of an Atheist”: Performing Private Truths in Precarious Publics. Uppsala: Uppsala Universitet. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, Andrew, Ed Stetzer, Tod Wilson, and Daniel Yang. 2020. How Church Leaders are Responding to COVID-19 Challenges: 2nd Round Survey. Christianity Today. Available online: https://www.christianitytoday.com/edstetzer/2020/april/how-church-leaders-are-responding-to-challenges-of-covid-19.html (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Minichiello, Victor, Rosalie Aroni, and Terrence Hays. 2008. In-Depth Interviewing: Principles, Techniques, Analysis. French Forests: Pearson Education Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Mora García de Lomas, Juan Manuel. 2006. Dirección estratégica de la comunicación en la Iglesia. Revista Comunicación y Sociedad 9: 165–84. [Google Scholar]

- Morello, Gustavo, Catalina Romero, Hugo Rabbia, and Néstor Da Costa. 2017. An enchanted modernity: Making sense of Latin America’s religious landscape. Critical Research on Religion 5: 308–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oesterheld, Jorge. 2016. No basta con un clic. Iglesia y comunicación. Madrid: PPC. [Google Scholar]

- Orlandis, José. 1985. Antropología y humanismo cristiano. Dios y el hombre. Pamplona: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Navarra. [Google Scholar]

- Oyarvide-Ramírez, Harold P., Edwin F. Reyes-Sarria, and Milton R. Montaño-Colorado. 2017. La comunicación interna como herramienta indispensable de la administración de empresas. Dominio de las Ciencias 3: 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parish, Helen. 2020. The Absence of Presence and the Presence of Absence: Social Distancing, Sacraments, and the Virtual Religious Community during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Religions 11: 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, Javier María. 1976. Los medios de comunicación en la doctrina social de la Iglesia. Madrid: Servicio de Publicaciones del Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research. 2020. 53% of Americans Say the Internet has been ess¥ential during the COVID-19 Outbreak. Pew Research. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2020/04/30/53-of-americans-say-the-internet-has-been-essential-during-the-covid-19-outbreak/ (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Piff, David, and Margit Warburg. 2005. Seeking for truth. Plausibility alignment on a Baha’i email list. In Religion and Cyberspace. Edited by Morten Hojsgaard and Margit Warburg. London: Routledge, pp. 86–101. [Google Scholar]

- Pou-Amérigo, María José. 2008. El hecho religioso y su tratamiento periodístico: Limitaciones y dificultades. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico 14: 561–73. [Google Scholar]

- Preece, Jenny. 2000. Online Communities: Designing Usability, Supporting Sociability. Industrial Management & Data Systems 100: 459–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reising, Richard. 2006. Church Marketing 101: Preparing Your Church for Greater Growth. Grand Rapids: Baker. [Google Scholar]

- Rheingold, Howard. 1993. Virtual community: Homesteading on the electronic frontier. Reading: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Camacho, Jesús. 2020. El Covid-19 y la Iglesia: Una respuesta ciberreligiosa sin precedentes. Fpablovi.org. Available online: https://www.fpablovi.org/index.php/covid-19-en-la-era-digital/963-el-covid-19-y-la-iglesia-una-respuesta-ciberreligiosa-sin-precedentes (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Serrano Oceja, José Francisco. 2019. La sociedad del desconocimiento. Comunicación posmoderna y transformación cultural. Madrid: Encuentro. [Google Scholar]

- Soberón, Leticia. 2015. What we can learn from Secular Social Media Networks. Deliberating together: A new paradigm of dialogue in the net. In Catholic Communities Online. Edited by Míriam Díez-Bosch, Josep Lluís Micó-Sanz and Josep Maria Carbonell Abelló. Barcelona: Blanquerna Observatory on Media, Religion and Culture, pp. 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Sorice, Michele. 2012. Social media e Chiesa. Il tempo del dialogo. In L’etica della comunicazione nell’era digitale. Edited by Ignazio Sanna. Roma: Studium, pp. 123–41. [Google Scholar]

- Spadaro, Antonio. 2012. Cyberteologia. Pensare il cristianesimo al tempo della rete. Milán: Vita e Pensiero. [Google Scholar]

- Spanish Episcopal Conference. 2020. Iglesia en España. Available online: https://conferenciaepiscopal.es/iglesia-en-espana/mapa-eclesiastico/ (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Statista. 2020a. COVID-19/Coronavirus. Facts and Figures. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/page/covid-19-coronavirus (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Statista. 2020b. Increases in Online Media Usage during the Coronavirus Pandemic in Germany, Spain, Netherlands, Italy, and Poland, as of March 2020. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1110864/online-media-use-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic-europe/ (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Tridente, Giovanni, and Bruno Mastroianni. 2016. La Missione Digitale. Comunicazione della Chiesa e Social Media. Roma: Edizioni Santa Croce. [Google Scholar]

- Turkle, Sherry. 1995. Life on Screen. Identity in the Age of the Internet. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Vera, José G. 2017. Introducción. La Iglesia y la comunicación. In Los retos del comunicador católico. Edited by Rafael Ortega and Álvaro de la Torre. Madrid: CEU, pp. 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Vera, José G. 2020. Personal interview. June 8. [Google Scholar]

- Viana, Antonio. 1997. Organización del gobierno de la Iglesia. Pamplona: Eunsa. [Google Scholar]

- Viganó, Darío E. 2017. En salida. Francisco y la Comunicación. Barcelona: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Volf, Miroslav. 2015. Flourishing. Why We Need Religion in a Globalized World. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Volf, Miroslav, and Ryan McAnnally-Linz. 2016. Public Faith in Action. How to Think Carefully, Engage Wisely and Vote with Integrity. Grand Rapids: Brazos Press. [Google Scholar]

- Voutsina, Chronoula. 2018. A practical introduction to in-depth interviewing. International Journal of Research & Method in Education 41: 123–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellman, Barry, Janet Salaff, Dimitrina Dimitrova, Laura Garton, Milena Gulia, and Caroline Haythornthwaite. 1996. Computer Networks as Social Networks: Collaborative Work, Telework, and Virtual Community. Annual Review of Sociology 22: 213–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sabaté Gauxachs, A.; Albalad Aiguabella, J.M.; Diez Bosch, M. Coronavirus-Driven Digitalization of In-Person Communities. Analysis of the Catholic Church Online Response in Spain during the Pandemic. Religions 2021, 12, 311. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12050311

Sabaté Gauxachs A, Albalad Aiguabella JM, Diez Bosch M. Coronavirus-Driven Digitalization of In-Person Communities. Analysis of the Catholic Church Online Response in Spain during the Pandemic. Religions. 2021; 12(5):311. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12050311

Chicago/Turabian StyleSabaté Gauxachs, Alba, José María Albalad Aiguabella, and Miriam Diez Bosch. 2021. "Coronavirus-Driven Digitalization of In-Person Communities. Analysis of the Catholic Church Online Response in Spain during the Pandemic" Religions 12, no. 5: 311. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12050311

APA StyleSabaté Gauxachs, A., Albalad Aiguabella, J. M., & Diez Bosch, M. (2021). Coronavirus-Driven Digitalization of In-Person Communities. Analysis of the Catholic Church Online Response in Spain during the Pandemic. Religions, 12(5), 311. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12050311