Abstract

Atheists are among the most disliked “religious” groups in the United States, but the origins of this aversion remain poorly understood. Because the media are an important source of public attitudes, we analyze coverage of atheism and atheists in American and British newspapers. Using computational text analysis techniques, including sentiment analysis and topic modeling, we show that atheism is portrayed negatively by the print media. Significantly, we show that greater negativity is associated with atheism as a concept than with atheists as individuals. Building on this insight, and challenging arguments that prominent atheist intellectuals attract negative coverage, we also find that coverage of famous atheists is actually more positive than that of atheists or atheism in general. Overall, our findings add a new dimension to scholarship on differences between individual-targeted and group-targeted tolerance in public attitudes, establishing for the first time that media coverage mirrors such differences.

1. Introduction

Popular perceptions of atheism present a puzzle: even though non-belief has been rising steadily (Burge 2020), studies also find strong and persistent prejudice against atheists across many different countries (Edgell et al. 2006; Gervais et al. 2017). One possible source for such prejudice is media coverage, but until now there has been no systematic research into how the media cover atheists and atheism. Is coverage of atheism actually negative in ways that might help account for observed anti-atheist prejudice? If so, are there discernible differences in the target of the negativity, such as between atheism as a doctrine and atheists as individuals?

Answering such questions is crucial if we want to develop a better understanding of the origins and persistence of anti-atheist prejudice. Until now, most inquiries have focused on the nature of this prejudice, not its particular causes or components. One common explanation is that many people believe atheists are amoral, or even immoral: people see religious belief as a prerequisite for moral behavior (Franks and Scherr 2014; Gervais et al. 2011). More specifically, they appear to distrust atheists’ capacity for caring and compassion (Simpson and Rios 2017). In addition, a number of studies have shown that many people think atheists are more likely than non-atheists to steal, abuse animals, or even murder (Gervais et al. 2017; Giddings and Dunn 2016). These perceptions and beliefs hold across many different countries (Gervais et al. 2017) and exist to some degree even among atheists themselves (Gervais et al. 2017; Giddings and Dunn 2016).

As for the origins of the dislike many people feel for atheism and atheists, some scholars posit an important role for cultural evolution, arguing that a belief in a supreme being who is “omniscient, powerful, and morally involved” may facilitate social cooperation and may thus have conveyed cultural advantages over time (Gervais and Norenzayan 2013, p. 133; Norenzayan et al. 2016). However, a cultural evolution argument is an indirect explanation at best: We still require a more immediate account of where people acquire their beliefs about atheism and atheists.

It is well-established that the media serve as an important source for public attitudes in general (Mastro and Tukachinsky 2014), as well as for attitudes towards specific religions in particular (e.g., Dick 2019; Saleem et al. 2017; Schmuck et al. 2020). Indeed, this is the case especially for religious groups with which most people in Western societies do not have much conscious personal interaction, such as Muslims or Mormons (Pew Research Center 2007). It seems plausible, then, in light of pervasive general public antipathy towards and distrust of atheists, that media coverage of atheism and/or atheists would also be quite negative overall. However, we know neither whether this is true nor what such negative coverage might be about. Is coverage driven by negative philosophical assessments of atheism as the absence of religion? By negative accounts of major political actors often associated in the public mind with atheism, such as the Soviet Union or China? By major political controversies? Or by negative coverage of individual atheists?

Because so little is known, there is much to be gained from a detailed analysis of how the media portray atheism and atheists. In this article, we first gauge the extent to which coverage of atheism is negative; next, we systematically analyze the main topics present in the coverage of atheism and test various potential explanations for negative coverage. Specifically, using a corpus of more than 15,000 newspaper articles that mention atheism or atheists drawn from leading newspapers in the United States and the United Kingdom, we analyze the overall tone of coverage, the tone of the immediate context surrounding references to atheism or atheists, the topics of these articles, and the people (and type of people) they are most likely to identify as atheists. To do so, we deploy computational text analysis methods including sentiment analysis, topic modeling, and collocation analysis.

Our contribution to the literature is both empirical and theoretical. Empirically, we show that atheism is indeed portrayed negatively by the print media. Some of the most negative coverage is associated with foreign news, but domestic coverage is negative as well. Articles touching on domestic topics such as politics, education, and science are not necessarily negative in and of themselves. However, we show that the sentences mentioning atheism within such articles do tend to be negative even within articles that are neutral or positive overall. Most importantly in theoretical terms, we show that media coverage parallels public attitudes in displaying a “dilution effect”, in which people are less tolerant of abstract groups than of specific individuals. In the media, analogously, greater negativity is associated with atheism as a concept than with atheists as individual people. Relatedly, and challenging arguments that prominent atheist intellectuals attract negative coverage (Zenk 2013), we find that coverage of famous atheists is actually more positive than that of most references to atheists or atheism. This is the first study to demonstrate that the distinction between group-targeted and individual-targeted intolerance or prejudice exists not just within people’s minds but is also reflected in media coverage.

The article proceeds in four parts. We begin by providing a brief overview of the state of knowledge about the prevalence of atheism, public attitudes towards atheism, and the impact of media consumption on public attitudes. Next, we introduce our corpus of newspaper articles about atheism, after which we outline the text analysis methods we use. The final section presents the analyses and discusses the results.

2. Atheism, Public Opinion, Prejudice, and the Media

People who do not identify with any (organized) religion represent a growing share of the population in most countries in the Global North. For example, in 2007, 16% of the American population self-identified as religiously unaffiliated; by 2014, this number had climbed to 23%, and in the years since, it has risen further (Pew Research Center 2019, p. 3). The number of people who explicitly identify as atheist is far smaller, due to stigma associated with the label, at least in the United States (Scheitle et al. 2019); nonetheless, this group, too, is undeniably growing (Pew Research Center 2019, p. 4). In the United Kingdom, meanwhile, more than half of the population does not identify with an organized religion (Guardian 2021).

As these numbers suggest, it is impossible to pin down precisely the number of atheists in a society. Doing so depends in part on one’s chosen definition of the concept: Is atheism the absence of a belief in a god or, instead, the belief that there is no god? Or is it simply uncertainty about the existence of a god? The range of possibilities has led to a profusion of related terms—agnostic, secularist, humanist, and “none”, among others—along with scholarship attempting to clarify the distinctions (e.g., Quillen 2015; Burge 2020). While clarity is helpful, and crucial for those interested in the precise number of people who can be characterized as atheist, it is less important for our purposes. Our focus here is not on the precise meaning of the term, but rather on how and when it is used in the media.

Regardless of the precise number of atheists in society, there is little doubt that this number is rising in many countries around the world (e.g., WIN-Gallup International 2012). Yet, large portions of the general public view atheism and atheists with concern or dislike. The Pew Research Center regularly asks American respondents about their feelings towards different religious groups, using a feeling “thermometer” scale from 1 to 100. Precise feeling ratings fluctuate, but the ordering has remained stable, with Muslims and atheists at the bottom and Mormons a little higher. All three groups are ranked well below Jews and a variety of Christian denominations. In the most recent survey, in 2017, the thermometer rating for atheists was 50 (compared to 48 for Muslims, 54 for Mormons, and upper 60s for Jews and some Christian groups) (Pew Research Center 2017). This was an improvement over 2007, when the rating for atheists was just 35, compared to 43 for Muslims and 53 for Mormons (Pew Research Center 2007).

The key concern for many people appears to be that they perceive atheists as lacking in terms of their caring and compassion for other people (Simpson et al. 2019; Simpson and Rios 2017) and that (for this reason) atheists cannot be trusted (Gervais et al. 2011). Relatedly, Franks and Scherr show that negative feelings are particularly driven by disgust, distrust, and fear and that atheists face more prejudice than do LGBTQ people or people of color (Franks and Scherr 2014). These negative perceptions have implications for outcomes: atheists are less likely to be accepted, both in private interactions and as public figures, than are members of a long list of other groups (Edgell et al. 2006, 2016). Moreover, atheists are at a particular disadvantage compared to other religious groups, as “increasing acceptance of religious diversity does not extend to the nonreligious” (Edgell et al. 2006, p. 211). Indeed, in a 2019 survey, 20% of respondents in the United Kingdom and 44% of respondents in the United States said, “it is necessary to believe in God in order to be moral and have good values (Pew Research Center et al. 2020, p. 3).

While a substantial number of studies have focused on the United States, Gervais et al. showed that many of the patterns identified above hold across countries. Their study finds anti-atheist prejudice in 12 of the 13 countries studied, with Finland being the lone exception (Gervais et al. 2017, p. 2). Other research looking at individual countries reinforces these findings. For example, Giddings and Dunn find anti-atheist prejudice to be robust in the United Kingdom (2016), and Clobert et al. find that while religious Taiwanese tend to be accepting of other religious groups, this tolerance does not extend to atheists (Clobert et al. 2014, p. 1522). Finally, analyses of the World Values Survey, covering dozens of countries, show that in most countries with religious majorities, people tend to doubt the fitness for public office of atheists (Inglehart et al. 2004).

As this last point suggests, for some people, the lack of religious belief itself appears to be the crucial issue—not the possible implications of that lack of belief for an individual’s behavior or morality. Scholars have identified a “dilution effect”, by which information about particular individuals serves to reduce the impact of prejudice against groups of which those individuals might be members (Nisbett et al. 1981; Hilton and Fein 1989; Fein and Hilton 1992). Golebiowska has shown that this dilution effect operates in political contexts, including when the group membership is not physically obvious, as is the case with atheism (Golebiowska 1996, 2003). In addition, it applies “even when people have essentially no information about the individual or collective they are judging” (Critcher and Dunning 2014, p. 687). In fact, a separate literature on perspective-taking shows that even exposing people to imagined interactions with individual members of a disliked outgroup reduces prejudice (Broockman and Kalla 2016; Paluck et al. 2020; Turner and Crisp 2010). In line with this literature, Swan and Heesacker find that it is the fact of not believing in a God, rather than individual actions or attitudes, that prompts dislike. Moreover, seeing an atheist as an individual, with additional characteristics besides simply that label, dramatically reduces dislike (Swan and Heesacker 2012, pp. 37–38).

On the other hand, some specific atheists may be subject to consistently negative coverage. As Taira notes, the media readily “criticize and even ridicule” people such as British evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, who has become prominent as one of the “New Atheists” (Taira 2015, p. 110). Similarly, Zenk finds it striking how many of the themes “found in the discourse on ‘New Atheism’ are negative” (Zenk 2012, p. 44). Finally, some have suggested that the atheist label itself is toxic (e.g., Dennett 2003). In fact, “atheist” appears as a negative word in a widely used lexicon of positive and negative words (Baccianella et al. 2010). Given these negative connotations, it is no surprise that the number of people who do not believe in a god is larger than the number who identify themselves as “atheist” (Kosmin et al. 2009, p. 14).

Media coverage is likely an important factor shaping public beliefs about atheists and atheism. Media consumers can glean negative information about groups even through skimming newspaper articles or headlines (Weinberger and Westen 2008), and the impact is greater if exposure is repeated (Fairclough 2013, p. 45). Once an opinion about another group—including a prejudice—takes root, it can be difficult to change (Lupia et al. 2015, p. 1; but see Mastro and Tukachinsky 2014; Schemer 2012). Media consumers may thus be left with conscious or subconscious negative attitudes (Erisen et al. 2014; Arendt and Northup 2015; Pérez 2016; Kroon et al. 2020). Scholars have shown how this dynamic operates with respect to marginalized groups in a wide variety of settings (Eberl et al. 2018).

We are not aware of any studies combining insights from the literature on individual-targeted versus group-targeted intolerance with analyses of media portrayals of groups. This is surprising because, given the close connection between media coverage and public beliefs, we might expect to find differences between individual-targeted and group-targeted references to (members of) groups. In particular, it seems plausible that the media might be more negative about a religion (seen as the characteristic shared by a group) than about individual adherents of the religion.

The idea that public dislike of atheism and atheists implies that the media are likely to be negative about them is at odds with some of the literature on religion in the media, which argues that the media in many Western countries have become increasingly secularized, following along with its respective society. As a result, the argument goes, many public and media figures have become skeptical and disparaging of religious practices (Casanova 2006; Cesari 2007; Roy 2016; Brubaker 2017). However, a closer look at the media in some of these countries suggests a more equivocal stance. Specifically, Silk asserts that “The American news media presuppose that religion is a good thing… As hostile, ham-handed, or ignorant as their approach may sometimes appear, the media will never be caught attacking religion as such” (Silk 1998, p. 57). Even in the case of the UK, Knott, Poole, and Taira suggest that the common notion of a secularist media “should be challenged or at least refined”, finding that “The media is rarely anti-religious” and “it is rare to find an overtly positive media representation of atheism and its supporters” (Knott et al. 2013, p. 117).

A small number of studies have looked, impressionistically, at the coverage of atheism in the media. In a historical overview, Drescher shows that the media long offered religious leaders a platform for disparaging atheism (Drescher 2014). Moreover, at the height of the Cold War, atheism was portrayed as foreign and linked to Communism. Over time, however, the coverage of atheism in the United States has shifted from “being that of a Christian heresy to an independent social movement with its own identity and culture” (Cimino and Smith 2014, p. 2). In the New York Times, at least, “The assumption of both news and opinion articles… is that atheism is an acceptable choice to be represented alongside religious belief” (Cimino and Smith 2014, p. 5).

Studying the United Kingdom, Knott, Poole, and Taira find the discussion of atheism and secularism to be centered around the place of religion in public life and around atheists’ campaigning for visibility. They note that prominent former Oxford University scientist and author Richard Dawkins has effectively “hijacked the media portrayal of atheists and of non-religious people in general.” Given Dawkins’ professional training, it is not surprising that Knott et al. find that discussions of atheism also focus on the (in)compatibility of religion and science (Knott et al. 2013, p. 107). Taira similarly highlights Dawkins’ visibility in the media’s coverage of atheists, noting that “media find it convenient to cover antireligious atheists, but difficult to render visible people of no religion who are not interested in campaigning against religion” (Taira 2015, p. 118).

The preceding overview gives rise to several hypotheses. We start with the possibility that coverage of atheists and atheism is not actually negative or perhaps is even positive, as the literature on secularization might lead us to expect. On the other hand, given what we know about public opinion regarding atheism and about the media’s impact on public attitudes, we expect coverage to be negative. In that case, it becomes crucial to examine in what ways and about whom it is negative. One possibility, still partly in keeping with the hypothesis that coverage is not negative, is that atheism is simply associated with negative topics: In other words, negative coverage might not be negative about atheism per se. For example, during the Cold War, atheism was associated with Communism and the Soviet Union; today, it might be associated with China. More broadly, foreign news is likely to be more negative than domestic news (Galtung and Ruge 1965; Harcup and O’Neill 2017). Negative coverage of atheism might thus be a result not of anything intrinsic to atheism or atheists but, rather, of their frequent presence in foreign news. Taken together, (H1) and (H2) constitute the null hypothesis for our study: that media coverage is not actually negative about atheism (and, accordingly, cannot directly account for negative public attitudes):

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Media coverage of atheism is not negative.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Media coverage of atheism itself is not negative, but atheism is associated with negative topics, especially foreign news.

If the coverage of atheism and atheists is in fact negative, the literature on the dilution effect and individual-versus group-targeted tolerance suggests that this negativity should be associated more with atheism as a belief, or group characteristic, than with atheists as individual people. While these theories have not previously been tested on media coverage, the close connection between the media and public attitudes suggests that the same patterns might be evident in the media. Alternatively, specific atheists might be covered more negatively than the abstract idea of atheism. The media may be drawn to coverage of prominent atheists (Taira 2015, p. 118), and such coverage may well be critical of perceived militancy and aggressiveness (Zenk 2012). If so, we would expect coverage of prominent atheist intellectuals to be disproportionately negative, especially in terms of how they are described as people. We test each of these alternative hypotheses.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Negative coverage is primarily about atheism, not individual atheists.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Atheists are systematically described in negative terms, and coverage of prominent atheists is disproportionately negative overall.

These hypotheses have dramatically different implications for our understanding of both how the media cover atheism and how consumers may develop negative associations with atheists and atheism.

3. Data

We collected a corpus of all articles mentioning atheism or atheists in four major nation-wide United States newspapers and the three top British broadsheet newspapers, along with their Sunday counterparts, for the years 2000–2018. We selected these countries for two reasons. First, they have been the targets of a disproportionate share of scholarship about public attitudes towards atheism. In particular, studies and surveys in both countries confirm broad anti-atheist prejudice (Edgell et al. 2016; Giddings and Dunn 2016; Pew Research Center et al. 2020). Second, the literature on secularism and religion in the media suggests that the US media might be more negatively disposed towards secularism in general and atheism in particular than the UK media. Accordingly, some of our hypotheses may receive confirmation in one country but not the other, adding nuance to our findings.

Because it is impossible to sample every media source in both countries, we limited ourselves to leading, national non-tabloid newspapers in both countries. These are of particular interest because they have country-wide readership and because other media outlets often take cues from large, national papers (Vargo and Guo 2017; Golan 2006; Zhang 2018). In particular, the four US newspapers we selected included the two largest-circulation papers (USA Today and Wall Street Journal) and the two papers that are widely considered “newspapers of record” (New York Times and Washington Post).1 For the United Kingdom, we similarly selected the two “newspapers of record” (Times and Telegraph); because both lean right politically and we did not want to privilege a particular political ideology, we added the largest-circulation left-leaning national broadsheet (Guardian). To collect the articles for our corpus, we searched NexisUni for the word stem “atheis*”, so as to capture all possible endings: The asterisk is a wildcard indicating that we will capture any word beginning with the letters “atheis”—“atheism”, “atheist”, “atheistic”, etc. Table 1 shows the results by newspaper source.

Table 1.

Atheism corpus: number of articles by source.

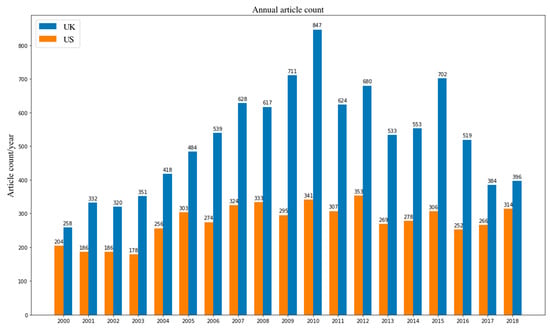

Although our hypotheses do not speak to over-time variation, it is worth briefly examining patterns in publication over time to make sure that unusual spikes in coverage do not bias our overall findings. Figure 1 shows the annual article count. Our corpus contains more articles from the United Kingdom each year; the difference in total articles between the two countries is highest around 2010, due to the emergence of the so-called “New Atheism” movement, spearheaded by authors such as Richard Dawkins. As Figure 1 makes clear, the resulting debates have produced a sustained increase in the media’s coverage of atheism and atheists: Even at the lowest point in recent years, in 2017, coverage remained noticeably higher than at the beginning of the century in both countries.

Figure 1.

Articles per year mentioning atheists by country.

4. Methods

To test our hypotheses, we used three computational text analysis techniques: sentiment analysis, topic modeling, and collocation analysis. Sentiment analysis aims to identify whether the tone of a text is positive or negative; this is a question of great interest across the social sciences, and the development of different sentiment analysis techniques has accelerated in recent years (e.g., Rice and Zorn 2019; Young and Soroka 2012). In this study, we applied a lexicon-based approach that provides information not just on whether a text is positive or negative, but also about how positive or negative it is. We scored each text based on the positive and negative words in eight widely used, general-purpose sentiment lexica. To gauge the overall positivity or negativity of each text, we scaled each of the eight resulting values against a representative corpus of newspaper articles (this constituted our neutral benchmark) and took the average of the resulting values to get a single sentiment measure.2

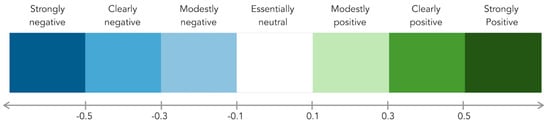

The representative corpus contains over 100,000 articles selected randomly from a range of US and UK newspapers over a period of two decades using neutral keywords. Validation tests have shown the average tone of these articles to be neutral (Bleich and van der Veen forthcoming). We scaled our single sentiment measure against the standard deviation of the representative corpus, making our sentiment values interpretable relative to those articles: A value of −0.33, for example, means that a text’s tone is equivalent to that of an article whose sentiment is one-third of a standard deviation less positive than the mean in the representative corpus. Because the tone of texts in the representative corpus follows a normal distribution, this means that our text in question is more negative than 63% of newspaper articles. The same sentiment analysis approach has been used successfully to assess the tone of media coverage of a number of different topics (including religious issues) in the US and UK media (e.g., Bleich et al. 2018a, 2018b; van der Veen and Bleich 2021). Based on these studies, it is possible to roughly classify the level of negativity represented by a particular sentiment score, as shown in Figure 2. Our sample text falls into the “clearly negative” range in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Sentiment score classification.

We combined our measures of the tone of texts with indicators of their subject. Topic modeling algorithms inductively identify sets of words that often occur together within a text across all texts in a corpus. Such clusters of words usually indicate specific topics common within the corpus. These, in turn, can be amalgamated into broader themes comprising multiple, logically related topics.3 A number of different topic modeling algorithms are widely used; of these, latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) (Blei 2012) and non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) (Lee and Seung 1999) are perhaps best known. Each algorithm has strengths and weaknesses, but generally they produce similar results. Here, we used NMF, which has the attractive feature of producing topics that are fairly stable: If a topic is found when the algorithm is asked to identify 15 different topics, it will generally also be present in the same form when the algorithm identifies 16 different topics. This is not always the case with LDA.

In addition, NMF tends to outperform LDA on measures of average topic coherence. This matters because coherent topics are topics that make sense to human beings as well as to the algorithm computing them. A topic is coherent when the words most strongly associated with it fit meaningfully together. To assess topic coherence, we relied on an algorithm that calculates how close a topic’s top words are to one another when all words are projected into a multidimensional semantic space. A number of such algorithms exist; we used word2vec, which is the best known and most widely used (Mikolov et al. 2013). Using the information this algorithm produces about how closely words are associated with other words, we can automatically calculate how coherent the top words in each topic are and produce an average coherence measure for the topic model as a whole.4 We chose the number of topics for which average topic coherence is highest. For our atheism corpus, that number is 16.

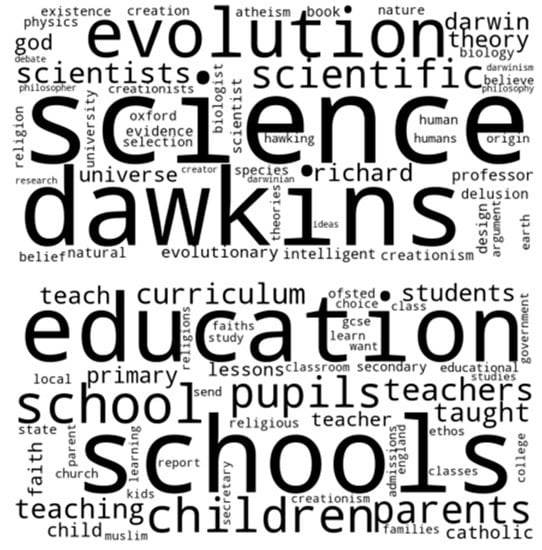

The topic modeling analysis provides an unrivalled overview of the substance of newspaper articles in which atheism or atheists are mentioned. It also enabled us to test our hypothesis about atheism’s association with negative and/or foreign topics (H2). Each topic consists of a number of words; the algorithm assigns each word a weight within the topic. One way to visualize these different weights is to look at the top words in a word cloud with their size scaled by their weight. Figure 3 shows examples of two such visualizations for topics about science and education, respectively. The first of these lends support to the claim, cited earlier, that Richard Dawkins has “hijacked” discussions of atheism: In the “science” topic, his last name is the second most salient word. The second illustrates one domestic issue area accounting for a lot of media coverage of atheism and atheists: schooling and curriculum issues.

Figure 3.

Word clouds for the “science” and “education” topics.

Table 2 provides a summary overview of the topics identified by our model. For each topic, it provides a category, a name, the top five words associated with the topic, and the share of articles in the corpus with that topic as the most important topic of the text for each country.5 For each newspaper article, our algorithm produced a weighted list of the topics present in that article. In most articles in our corpus, four to five topics are present, though only a few of them are prominent: the average weight of the top topic within each article is 56.7%. The percentages in Table 2 take into account only these top topics.

Table 2.

Overview of the 15 substantive topics in the atheist corpus.

The final computational method we used was collocation analysis, which examines word usages and contexts systematically. This allowed us to ascertain whether a word’s appearance in a particular context is statistically and substantively significant. For example, if we look at the immediate neighbors of the word “atheism”, do we encounter certain negative words more often than we would expect, given the overall frequency of those words in newspaper articles? If so, that indicates that such negative words are associated, in textual terms, with “atheism” and—as a result—may well become associated with atheism in readers’ minds.

5. Analysis and Discussion

We began by analyzing the tone of texts that mention atheists or atheism in British and American newspapers. As we saw in our overview of the literature, very little has been written about the tone of media coverage of atheism. Knott et al. argue that, in the United Kingdom, “it is rare to find an overtly positive media representation of atheism and its supporters” (Knott et al. 2013, p. 117), while Cimino and Smith note that in the United States (or, rather, in the New York Times) atheism is portrayed as “an acceptable choice to be represented alongside religious belief” (Cimino and Smith 2014, p. 5). These two assessments are not incompatible, but they leave a lot of room for interpretation: What tone do we expect to be associated with “overtly positive” or “acceptable choice” coverage?

Table 3, showing the average tone for different sets of articles and sentences in our corpus, offers an answer to these questions. The first row indicates that, in both the United Kingdom and the United States, articles that reference atheists or atheism are negative overall, albeit only mildly so. The next line, however, shows that those sentences that actually reference atheism or atheists are clearly negative on the scale introduced in Figure 2. We can thus reject our first null hypothesis (H1) that media coverage of atheism is not negative. Table 3 also provides insight into which types of reference are most negative. Sentences that mention “atheism” and “atheistic”, which refer to beliefs rather than people, are substantially more negative than those mentioning “atheists”, which refer to people; “atheist”, which can refer to either a belief (as an adjective) or a person (as a noun), falls in between. This serves as preliminary evidence in support of (H3) (negativity is about the idea) and against (H4) (negativity is about the people).

Table 3.

Sentiment analysis: the average tone of texts referencing atheism or atheists.

Next, we turned to the topics of the articles in our corpus: What are articles that mention atheism or atheists actually about? The initial overview of our topic model, shown in Table 2, already indicated that they are often not primarily about atheism or atheists. Table 4 lists the average valence of articles in our corpus by topic, allowing us to test our second null hypothesis (H2), that atheism is associated with negative topics, especially foreign news. Table 4 confirms our expectation that foreign news is negative overall: All three foreign topics are negative, as are the two topics about a particular religion, both of which are about religions that have a far stronger presence outside the UK and the US than they do inside.

Table 4.

Topic model: the average tone of articles about a topic by country.

It is difficult to say whether the salience of these five foreign topics is unusual. Moore (2010) finds that about 10% of UK newspaper coverage is dedicated to foreign news; comparable data for the US are lacking, but studies on the level of foreign news on television suggest that it is reasonable to assume that the US figure is in the same range (Aalberg et al. 2013). The sum of the shares of the three foreign topics is a little below that number: 8.2% overall across both countries. However, if we add in the two specific religion topics, which are often foreign news—articles in the Catholicism topic are often about the Vatican and the Pope, while articles in the Islam topic are often about Muslim-majority countries in the Middle East—its size nearly triples to 23%: significantly greater than the overall share of foreign news in the media.

We cannot conclude with confidence that atheism is disproportionately associated with foreign news: This depends on whether one judges articles about Catholicism or Islam to be foreign. However, we can infer that negative coverage of atheism is not driven uniquely by its connection to foreign topics. While the foreign topics are among the most negative in our corpus, they simply do not account for a large enough share of articles to explain the negativity associated with atheism at the sentence level shown in Table 3. Indeed, as we shall see below, even within the non-foreign topics, which are balanced between negative and positive, references to atheism at the sentence level remain negative in tone.

For the same reason, given the share of articles assigned to topics whose average tone is positive in our corpus, it seems implausible that the tone of sentence-level references to atheism and atheists is driven only by the association of atheism with negative topics. In fact, the average tone of such sentence-level references, for sentences in articles assigned to one of the six positive topics in Table 4 only, is −0.11: less negative than the overall figure, but modestly negative nonetheless. We can thus also reject our second null hypothesis: that negativity in the coverage of atheism is due to its association with negative topics, especially with foreign news.

Next, we examined whether the negativity associated with atheism and atheists in the media is associated more with ideas or with people. In order to avoid biasing results by the overall negative tone of foreign news, we excluded our five foreign topics from the following analyses. Of the remaining 10 topics, two are about general issues of religion and faith. Four are about politics: one topic each for UK and US politics in general, plus two about legal issues. One of these focuses on the US Pledge of Allegiance, which, since 1954, includes a reference to God and is often recited in schools. As is clear from Table 4, legal issues associated with atheism are far more salient in the United States than in the United Kingdom.8 The final four topics cover science, education, entertainment, and broadcast scheduling. Richard Dawkins figures prominently within the science topic; not surprisingly, this topic is almost twice as prominent in the UK media as it is in the United States. Education is a much more prominent topic in the UK than in the US; this is likely a result of US discussions of atheism in the context of education getting wrapped up into legal debates about the Pledge of Allegiance and the First Amendment.

For the next analysis, we focused on articles whose main topic is one of these 10 non-foreign topics (a total of 6769 articles).9 In addition, we pooled articles from the United Kingdom and the United States together, because Table 4 shows that coverage of atheism is comparable across these two countries: The correlation between the two countries in terms of the average tone of the different topics is a very high 0.96, and even the prominence of different topics (as shares of all articles) is correlated, albeit at a lower 0.53.10 The possibility, raised earlier, that the UK media would be more positive about atheism because they are more secularist than their US counterparts is not borne out by the data presented above in Table 3.

We began by comparing how “atheism” and “atheistic” are covered compared to “atheist” and “atheists”: The latter are generally used to refer to people; the former more abstractly to beliefs. Table 3 already indicates that the latter are associated with more negative coverage; however, this could be due to their disproportionate presence in foreign coverage. Table 5 presents comparable data for the part of the corpus whose main topic is one of the 10 non-foreign topics. Rather than present data on every subset, we show data for the most consequential division: those articles that contain the words “atheism” or “atheistic” and that thus reference ideas, compared to those that do not and that thus reference people. Table 5 also lists the top 10 common adjectives that are most strongly associated with these terms, as indicated by a collocation analysis comparing words in sentences containing each term to the full texts of the newspapers from which we drew our corpus.11

Table 5.

Tone and top collocates in articles on non-foreign topics: atheism vs. atheist(s).

These data offer additional support for (H3) (negativity is primarily about atheism as a set of ideas) and against (H4) (negativity is primarily about atheists as individual people). The valence data reinforce the message from Table 3: Within non-foreign articles, the average tone of full articles remains close to neutral, while that for sentences referencing atheism is clearly negative. Moreover, that negativity is greater for sentences mentioning “atheism” or “atheistic” than it is for those mentioning “atheist” or “atheists”, where the average tone is only modestly negative.12 The difference is accentuated when we examine the top adjectives listed in the right-hand column. For “atheism” and “atheistic”, this includes the clearly negative terms “dogmatic” and “insulting”, along with the arguably negative terms “godless”, “fundamentalist”, and “militant”. To give just one example of a sentence with one of these negative terms, an article titled “Is atheism just a rant against religion?” in the Washington Post (26 May 2007) contains the sentence “Atheism’s new dogmatic streak is not that different from the religious extremists it calls to task, he said.”13 In contrast, for “atheist” and “atheists”, the list in Table 5 only contains one arguably negative term: “godless”. Sentences containing “atheist” and “atheists” are still negative overall, however, because (similar to sentences containing “atheism” and “atheistic”) they also include words that do not stand out as much for their presence in this context but that do have a strong negative tone or connotation.

The second part of (H4) predicted coverage of prominent atheists to be disproportionately negative overall and, relatedly, for such atheists to be described in negative terms. Public intellectuals who are known in part as a result of their outspoken atheism include Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, Christopher Hitchens, Sam Harris, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, and Bill Maher—the first five have all written books in which atheism features prominently; the last produced a movie challenging religion, Religulous. In addition, our corpus contains repeated references to one leading politician widely known to be (and described as) atheist: former British Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg of the Liberal Democrats. Table 6 lists the average tone of articles and sentences in our full corpus—not excluding the foreign categories—in which Clegg or any of the six public intellectuals appear. We added a separate row for Richard Dawkins by himself in light of his prominence.

Table 6.

Sentiment analysis: the average tone of texts containing the names of prominent atheists.14

Table 6 shows that prominent atheists are not covered in unusually negative terms. Sentences including a word beginning with “atheis” are only mildly negative—less negative than the overall values shown in Table 5. Strikingly, in articles where these prominent atheists are explicitly identified with atheism—their name appears in a sentence also containing an “atheis” word—the average tone of atheis* sentences is actually positive. This is a marked contrast to every other sentence-level measure we have seen so far, all of which were negative. Even in non-foreign articles not mentioning “atheism” or “atheistic”, Table 5 showed that the mean sentence-level valence for sentences mentioning atheist(s) was −0.20. In other words, well-known atheist intellectuals are described in terms that are decidedly less negative compared to other atheists. The same applies even more strongly to the politician most explicitly associated with atheism, Nick Clegg: Both sentence-level measures are actually positive. For example, a 24 December 2007 article in The Guardian noted that “If anything, the religious are overrepresented in politics, so there should be opportunities for atheists such as Mr. Clegg.” Based on the results presented in Table 5 and Table 6, we can confidently reject (H4) (that negativity associated with atheism is about specific atheists).

One implication of this last finding is that in articles not mentioning highly visible atheist intellectuals, sentences mentioning atheism or atheists must actually be more negative than we saw in Table 5. In fact, the adjusted values are −0.44 (was −0.33) and −0.23 (was −0.20), respectively. In other words, the difference in the tone of coverage between articles mentioning “atheism” or “atheistic” and those that do not looms even larger when we take away texts that mention the most prominent atheists. This adds further support to (H3) and to the group versus individual intolerance dynamic that the hypothesis represents.

As a robustness check for our rejection of (H4), we investigated one final possibility: that the coverage of atheists in general is more similar to that seen in Table 6 than the aggregate data shown in Table 5. Specifically, it might be that the average tone of sentences referencing atheists is pulled down because the media frequently identify people who do something dislikable as atheist. If that is the case, it might be that more general references to atheists are not as negative as the aggregate data suggest. For example, we know that African Americans are overrepresented as criminals in the news compared to crime statistics (Dixon 2019, p. 246), and it has been shown that this has an effect on public attitudes (Gilliam and Iyengar 2000). An analogous process might be at work with media portrayals of atheists.

If the media over-identify atheists who do something dislikable, we would expect the phrases “who is (an) atheist,” “who are atheist(s),” and “, an atheist,” (including the commas at the start and end) to be associated frequently with negative descriptions or accounts of the person(s) in question. In our corpus, a total of just 70 articles (out of more than 15,000) contain one of these phrases. Of those, not one is used to identify as atheist someone who has done something that makes them a criminal or untrustworthy. Instead, the phrasing is used to identify leaders such as British politicians Nick Clegg and Ed Miliband when they interact with religious figures (the Pope, the Archbishop of Canterbury, etc.) or other people whose atheism may help explain why they find themselves in a particular situation (a cartoonist or a chess player each perceived to have made fun of Christianity, for example).15

There is a single example of the phrase “who are atheists” being used in a way that might seem to cast aspersions on atheists: “Doctors who are atheist or agnostic are twice as likely to take decisions that might shorten the life of somebody who is terminally ill as doctors who are deeply religious.” However, the article in question takes pains to point out that shortening life might in fact be the choice desired by a patient who is suffering. In other words, the problem is not doctors who are atheists, but rather those whose views are at odds with those of their terminally ill patients, whether religious or not.16 An interesting contrast is offered in another article, from the same newspaper later that same year, about the possibility of non-atheists being problematic. That article, about scientific experimentation on animals, argues that “scientists who are atheists need to be morally more rigorous than those who believe animals were created for our use and exploitation.”17

6. Conclusions

Although scholars have established a widespread pattern of anti-atheist prejudice, until now no study has systematically analyzed one plausible driver of such prejudice: media coverage of atheism and atheists. We have done so here, analyzing print media coverage of atheism over a twenty-year period in the United Kingdom and the United States in terms of its overall tone, its topics, and its treatment of prominent and less prominent atheists. As such, the present study contributes to the broader literature on public prejudice against atheists and atheism, which has until now largely focused on characterizing and measuring this prejudice (Edgell et al. 2016; Gervais et al. 2017; Norenzayan et al. 2016). The findings presented here offer important insights into one likely source of public attitudes.

Specifically, we have shown that coverage of atheism is negative overall. While articles in which atheism or atheists are referenced have, on average, a nearly neutral tone, sentences directly mentioning atheism or atheists are decidedly negative. While a number of scholars have argued that the US and the UK have become increasingly secularized and therefore perhaps less pro-religion, our findings indicate that such secularization has not led to positive treatment of atheism or atheists. Our analysis also shows that coverage of atheism is not specifically associated with negative topics. While references to atheists and atheism may be comparatively more common in foreign news coverage, which is often negative, most coverage in our atheism corpus is not about foreign topics, and a number of those non-foreign topics are not negative: faith, science, and education, for instance.

The key theoretical contribution of this article is to demonstrate, for the first time, that media coverage mirrors an important difference in public attitudes between individual-targeted and group-targeted tolerance. Specifically, the literature on the dilution effect shows that people tend to think less negatively about individual members of a group than they think about the overall group and its characteristics. Given the close links between media content and public attitudes, it was plausible that media coverage would reflect a similar difference; however, this had not previously been demonstrated. We show that negativity in the media is more strongly linked to the coverage of atheism (the idea that constitutes the group) than it is to atheists, as individual people. Sentences referencing “atheism” or “atheistic” are notably more negative than those referencing “atheist” or “atheists” on average. This is true both for the entire corpus and for the subset that is not about foreign news.

In addition, among the words whose presence in sentences referencing “atheism” or “atheistic” stands out most, we find clearly negative words such as “dogmatic” and “insulting”; no such similarly negative words appear in the corresponding list for “atheist” and “atheists”. Finally, we show that coverage of the most visible atheist public intellectuals is neutral—more positive, in other words, than the coverage of lesser-known or unnamed atheists. This finding cuts directly against the alternative hypothesis that the negative connotation of atheism is driven to a considerable degree by negative impressions people have of prominent atheist figures.

Most of the literature on anti-atheist prejudice has glossed over the possibility that this prejudice is attached more to the idea of atheism and to the abstract group it represents than to specific individuals who subscribe to that idea. For example, the largest cross-national source of data about anti-atheist prejudice is the World Values Survey, which contains a question about whether a respondent deems someone who does not believe in a god fit for public office (Inglehart et al. 2004). Negative responses to this question have traditionally been interpreted as evidence of prejudice against atheists (e.g., Gervais 2011, p. 546); however, in light of our findings here, such responses might more accurately be interpreted as reflecting prejudice against atheism.

This is not to suggest that there is no prejudice against atheists: Clearly prejudice against atheism and prejudice against atheists are related. However, our findings indicate that the media do not communicate strong negativity vis-à-vis famous atheist individuals, and while coverage of less well-known or unnamed atheists is modestly negative, it is measurably less negative than coverage of atheism. In sum, our findings suggest that public dislike—at least, in so far as it is reflective of media coverage—may be centered around an aversion to non-belief, rather than of individual atheists or of any perceived implications of atheism for a person’s character or behavior. Given that the number of people who do not believe in a god continues to grow around the world and that more and more of them are likely to seek public office, among other activities, accurately identifying the root causes and contents of anti-atheist beliefs appears more important than ever.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/rel12050291/s1, Table S1: Sentiment analysis—average tone of texts in our corpus, by decade, Table S2: Topic model: overview of the 16 topics in the atheist corpus, Table S3: Tone of coverage and top adjective collocates in articles on non-foreign topics: atheism vs. atheist(s).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.v.d.V. and E.B.; Data curation, A.M.v.d.V.; Formal analysis, A.M.v.d.V.; Investigation, A.M.v.d.V and E.B.; Methodology, A.M.v.d.V. and E.B.; Project administration. A.M.v.d.V. and E.B.; Writing—original draft, A.M.v.d.V.; Writing—review & editing, A.M.v.d.V. and E.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions on disseminating data obtained from LexisNexis/NexisUni.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1. | Circulation data from https://www.agilitypr.com/resources/top-media-outlets/top-10-daily-american-newspapers/ (accessed on 31 March 2021). “Newspaper of record” information from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Newspaper_of_record (accessed on 31 March 2021). |

| 2. | We excluded positive and negative words directly associated with our topic of interest from the sentiment calculation. Specifically, we ignored “atheist”, which appears as negative in one lexicon, as well as “christian” (two lexica) and “church” (one lexicon), which appear as positive terms. For more information about all eight lexica and the sentiment analysis algorithm, see Bleich and van der Veen (forthcoming). |

| 3. | A useful way to think of topic modeling algorithms is that they attempt to reduce the complexity of texts by identifying a specified number of semantic features: They summarize texts, in a way. |

| 4. | Specifically, we calculated average mutual coherence (as measured by cosine distance) of the top 10 words in the topic. |

| 5. | NMF topic models tend to produce one or more “junk” topics; these can be seen as aggregates for all smaller topics whose contents do not fit nicely into one of the topics generated. As the number of topics produced by the model increases, these “junk” topics will become less and less significant. In our case, there is one such topic. More than 40% of all the texts in our corpus have this “topic” as their top topic. Because we could not meaningfully assign these articles to a particular topic, we ignored them in the analyses presented below. Including them instead did not change our substantive findings. The Supplementary Materials provide replication information including these articles. |

| 6. | Sally Quinn writes about religion for the Washington Post. |

| 7. | Michael Newdow filed a prominent lawsuit against the reciting of the Pledge of Allegiance in US in public schools. |

| 8. | This can be explained in part by the explicit separation of church and state in the First Amendment of the US Constitution; a similar separation does not exist in the United Kingdom. |

| 9. | The Supplementary Materials provide the analogous results if we also include those articles whose top “topic” is the generic (non-meaningful) topic. All substantive findings remain the same for this larger corpus of 13,092 articles. |

| 10. | Both correlation values exclude the two country-specific topics. |

| 11. | A word has to occur at least 10 times in our corpus to be included. The words are ranked in order of how disproportionate their presence is in sentences including one of our key terms. All of these associations are statistically significant. Not all words listed are pure adjectives: a number of the words can be used in either adjective or noun form. The list includes single words only; hyphenated adjectives (e.g., “non-religious”) are ignored. |

| 12. | The difference between the two values is statistically significant (p-value = 0.03). |

| 13. | In religious discussions, dogmatic can also have a positive connotation. However, in newspaper coverage, it is almost invariably associated with the negative colloquial meaning of expressing opinions strongly and perhaps arrogantly, as if they were fact. |

| 14. | These data reflect our full corpus, not just the articles about non-foreign topics included in Table 5. The values for the non-foreign subset are even more positive. |

| 15. | The cartoonist example is from “Online cartoons challenge stereotypes” (Washington Post, 27 December 2014). The chess player example is from “Grandmaster under fire after mocking chess player prayer” (Daily Telegraph, 12 March 2018). |

| 16. | “Atheist doctors more likely to hasten death” (Guardian, 26 August 2010). |

| 17. | “Blood, smoke, and rubble” (Guardian, 13 November 2010). |

References

- Aalberg, Toril, Stylianos Papathanassopoulos, Stuart Soroka, James Curran, Kaori Hayashi, Shanto Iyengar, Paul K. Jones, Gianpietro Mazzoleni, Hernando Rojas, David Rowe, and et al. 2013. International TV News, Foreign Affairs Interest and Public Knowledge: A Comparative Study of Foreign News Coverage and Public Opinion in 11 Countries. Journalism Studies 14: 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, Florian, and Temple Northup. 2015. Effects of Long-Term Exposure to News Stereotypes on Implicit and Explicit Attitudes. International Journal of Communication 9: 2370–90. [Google Scholar]

- Baccianella, Stefano, Andrea Esuli, and Fabrizio Sebastiani. 2010. SENTIWORDNET 3.0: An Enhanced Lexical Resource for Sentiment Analysis and Opinion Mining. Paper presented at LREC 2010, Valletta, Malta, May 17–23; pp. 2200–4. [Google Scholar]

- Blei, David M. 2012. Probabilistic Topic Models. Communications of the ACM 55: 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleich, Erik, James Callison, Georgia Grace Edwards, Mia Fichman, Erin Hoynes, Razan Jabari, and A. Maurits van der Veen. 2018a. The good, the bad, and the ugly: A corpus linguistics analysis of U.S. newspaper coverage of Latinx, 1996-2016. Journalism. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleich, Erik, Julien Souffrant, Emily Stabler, and A. Maurits van der Veen. 2018b. Media coverage of Muslim devotion: A four-country analysis of newspaper articles, 1996-2016. Religions 9: 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleich, Erik, and A. Maurits van der Veen. Forthcoming. Covering Muslims: American Newspapers in Comparative Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Broockman, David, and Joshua Kalla. 2016. Durably Reducing Transphobia: A Field Experiment on Door-to-Door Canvassing. Science 352: 220–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brubaker, Rogers. 2017. Between Nationalism and Civilizationism: The European Populist Moment in Comparative Perspective. Ethnic and Racial Studies 40: 1191–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burge, Ryan P. 2020. How Many ‘Nones’ Are There? Explaining the Discrepancies in Survey Estimates. Review of Religious Research 62: 173–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, José. 2006. The Long, Difficult, and Tortuous Journey of Turkey into Europe and the Dilemmas of European Civilization. Constellations 13: 234–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesari, Jocelyne. 2007. The Muslim Presence in France and the United States: Its Consequences for Secularism. French Politics, Culture & Society 25: 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimino, Richard P., and Christopher Smith. 2014. How the Media Got Secularism—With a Little Help from the New Atheists. In Oxford Handbooks Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clobert, Magali, Vassilis Saroglou, Kwang-Kuo Hwang, and Wen-Li Soong. 2014. East Asian Religious Tolerance—A Myth or a Reality? Empirical Investigations of Religious Prejudice in East Asian Societies. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 45: 1515–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critcher, Clayton R., and David Dunning. 2014. Thinking about Others versus Another: Three Reasons Judgments about Collectives and Individuals Differ: Thinking About Others versus Another. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 8: 687–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennett, Daniel. 2003. The Bright Stuff. New York Times, July 12. [Google Scholar]

- Dick, Hannah. 2019. Mitt Romney, Mormonism, and the Media: Popular Depictions of a Religious Minority. The Journal of Popular Culture 52: 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, Travis L. 2019. Media Stereotypes: Content, Effects, and Theory. In Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research, 4th ed. Edited by Mary Beth Oliver, Arthur A. Raney and Jennings Bryant. Routledge Communication Series; New York: Routledge, pp. 243–57. [Google Scholar]

- Drescher, Elizabeth. 2014. Nones by Many Other Names: The Religiously Unaffiliated in the News, 18th to 20th Century. In Oxford Handbooks Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberl, Jakob-Moritz, Christine E. Meltzer, Tobias Heidenreich, Beatrice Herrero, Nora Theorin, Fabienne Lind, Rosa Berganza, Hajo G. Boomgaarden, Christian Schemer, and Jesper Strömbäck. 2018. The European Media Discourse on Immigration and Its Effects: A Literature Review. Annals of the International Communication Association 42: 207–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgell, Penny, Douglas Hartmann, Evan Stewart, and Joseph Gerteis. 2016. Atheists and Other Cultural Outsiders: Moral Boundaries and the Non-Religious in the United States. Social Forces 95: 607–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgell, Penny, Joseph Gerteis, and Douglas Hartmann. 2006. Atheists As ‘Other’: Moral Boundaries and Cultural Membership in American Society. American Sociological Review 71: 211–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erisen, Cengiz, Milton Lodge, and Charles S. Taber. 2014. Affective Contagion in Effortful Political Thinking: Affective Contagion. Political Psychology 35: 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, Norman. 2013. Language and Power, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fein, Steven, and James L. Hilton. 1992. Attitudes toward Groups and Behavioral Intentions toward Individual Group Members: The Impact of Nondiagnostic Information. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 28: 101–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Franks, Andrew S., and Kyle C. Scherr. 2014. A Sociofunctional Approach to Prejudice at the Polls: Are Atheists More Politically Disadvantaged than Gays and Blacks? Journal of Applied Social Psychology 44: 681–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galtung, Johan, and Mari Holmboe Ruge. 1965. The Structure of Foreign News: The Presentation of the Congo, Cuba and Cyprus Crises in Four Norwegian Newspapers. Journal of Peace Research 2: 64–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervais, Will M. 2011. Finding the Faithless: Perceived Atheist Prevalence Reduces Anti-Atheist Prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 37: 543–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervais, Will M., and Ara Norenzayan. 2013. Religion and the Origins of Anti-Atheist Prejudice. In Religion, Intolerance and Conflict: A Scientific and Conceptual Investigation. Edited by Steve Clarke, Russell Powell and Julian Savulescu. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 126–45. [Google Scholar]

- Gervais, Will M., Azim F. Shariff, and Ara Norenzayan. 2011. Do You Believe in Atheists? Distrust Is Central to Anti-Atheist Prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 101: 1189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gervais, Will M., Dimitris Xygalatas, Ryan T. McKay, Michiel van Elk, Emma E. Buchtel, Mark Aveyard, Sarah R. Schiavone, Ilan Dar-Nimrod, Annika M. Svedholm-Häkkinen, Tapani Riekki, and et al. 2017. Global Evidence of Extreme Intuitive Moral Prejudice against Atheists. Nature Human Behaviour 1: 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddings, Leah, and Thomas J. Dunn. 2016. The Robustness of Anti-Atheist Prejudice as Measured by Way of Cognitive Errors. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 26: 124–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gilliam, Franklin D., and Shanto Iyengar. 2000. Prime Suspects: The Influence of Local Television News on the Viewing Public. American Journal of Political Science 44: 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golan, Guy. 2006. Inter-Media Agenda Setting and Global News Coverage: Assessing the Influence of the New York Times on Three Network Television Evening News Programs. Journalism Studies 7: 323–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golebiowska, Ewa A. 1996. The ‘Pictures in Our Heads’ and Individual-Targeted Tolerance. The Journal of Politics 58: 1010–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golebiowska, Ewa A. 2003. When to Tell?: Disclosure of Concealable Group Membership, Stereotypes, and Political Evaluation. Political Behavior 25: 313–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardian. 2021. The Guardian View on ‘post-Christian’ Britain: A Spiritual Enigma | Editorial. The Guardian. March 28 Sec. Opinion. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/mar/28/the-guardian-view-on-post-christian-britain-a-spiritual-enigma (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Harcup, Tony, and Deirdre O’Neill. 2017. What Is News?: News Values Revisited (Again). Journalism Studies 18: 1470–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, James L., and Steven Fein. 1989. The Role of Typical Diagnosticity in Stereotype-Based Judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57: 201–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, Ronald, Miguel Basanez, Juan Diez-Medrano, Loek Halman, and Ruud Luijkx, eds. 2004. Human Beliefs and Values: A Cross-Cultural Sourcebook Based on the 1999–2002 Value Surveys. Mexico City: Siglo XXI. [Google Scholar]

- Knott, Kim, Elizabeth Poole, and Teemu Taira. 2013. Media Representations of Atheism and Secularism. In Media Portrayals of Religion and the Secular Sacted: Representation and Change. New York: Taylor & Francis, pp. 101–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kosmin, Barry A., Ariela Keysar, Ryan Cragun, and Juhem Navarro-Rivera. 2009. American Nones: The Profile of the No Religion Population, A Report Based on the American Religious Identification Survey 2008. Hartford: Trinity College. [Google Scholar]

- Kroon, Anne C., Toni G. L. A. van der Meer, and Dana Mastro. 2020. Confirming Bias Without Knowing? Automatic Pathways Between Media Exposure and Selectivity. Communication Research 48: 180–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Daniel D., and H. Sebastian Seung. 1999. Learning the Parts of Objects by Non-Negative Matrix Factorization. Nature 401: 788–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupia, Arthur, Logan S. Casey, Kristyn L. Karl, Spencer Piston, Timothy J. Ryan, and Christopher Skovron. 2015. What Does It Take to Reduce Racial Prejudice in Individual-Level Candidate Evaluations? A Formal Theoretic Perspective. Political Science Research and Methods 3: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastro, Dana, and Riva Tukachinsky. 2014. The Influence of Media Exposure on the Formation, Activation, and Application of Racial/Ethnic Stereotypes. In The International Encyclopedia of Media Studies. Edited by Angharad N. Valdivia and Erica Scharrer. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, vol. 5, Available online: https://learning.oreilly.com/library/view/the-international-encyclopedia/9781118733561/190_vol-05-chapter-13.html (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Mikolov, Tomas, Kai Chen, Greg Corrado, and Jeffrey Dean. 2013. Efficient Estimation of Word Representations in Vector Space. arXiv arXiv:1301.3781. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Martin. 2010. Shrinking World: The Decline of International Reporting in the British Press. London: Media Standards Trust. Available online: http://mediastandardstrust.org/publications/shrinking-world-the-decline-of-international-reporting-in-the-british-press/ (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Nisbett, Richard E., Henry Zukier, and Ronald E. Lemley. 1981. The Dilution Effect: Nondiagnostic Information Weakens the Implications of Diagnostic Information. Cognitive Psychology 13: 248–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norenzayan, Ara, Azim F. Shariff, Will M. Gervais, Aiyana K. Willard, Rita A. McNamara, Edward Slingerland, and Joseph Henrich. 2016. The Cultural Evolution of Prosocial Religions. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 39: e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluck, Elizabeth Levy, Roni Porat, Chelsey S. Clark, and Donald P. Green. 2020. Prejudice Reduction: Progress and Challenges. Annual Review of Psychology 72: 533–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, Efrén O. 2016. Unspoken Politics: Implicit Attitudes and Political Thinking. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. 2007. Public Expresses Mixed Views of Islam, Mormonism. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewforum.org/2007/09/26/public-expresses-mixed-views-of-islam-mormonism/ (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Pew Research Center. 2017. Americans Express Increasingly Warm Feelings Toward Religious Groups. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewforum.org/2017/02/15/americans-express-increasingly-warm-feelings-toward-religious-groups/ (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Pew Research Center. 2019. U.S., Decline of Christianity Continues at Rapid Pace: An Update on America’s Changing Religious Landscape. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center, Christine Tamir, Aidan Connaughton, and Ariana Monique Salazar. 2020. The Global God Divide: People’s Thoughts on Whether Belief in God Is Necessary to Be Moral Vary by Economic Development, Education and Age. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Quillen, Ethan G. 2015. Discourse Analysis and the Definition of Atheism. Science, Religion and Culture 2: 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rice, Douglas R., and Christopher Zorn. 2019. Corpus-Based Dictionaries for Sentiment Analysis of Specialized Vocabularies. Political Science Research and Methods 9: 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, Olivier. 2016. Rethinking the Place of Religion in European Secularized Societies: The Need for More Open Societies. Fiesole: European University Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem, Muniba, Sara Prot, Craig A. Anderson, and Anthony F. Lemieux. 2017. Exposure to Muslims in Media and Support for Public Policies Harming Muslims. Communication Research 44: 841–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheitle, Christopher P., Katie E. Corcoran, and Erin B. Hudnall. 2019. Adopting a Stigmatized Label: Social Determinants of Identifying as an Atheist beyond Disbelief. Social Forces 97: 1731–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schemer, Christian. 2012. The Influence of News Media on Stereotypic Attitudes Toward Immigrants in a Political Campaign: Influence of News Media on Stereotypes. Journal of Communication 62: 739–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmuck, Desirée, Raffael Heiss, and Jörg Matthes. 2020. Drifting Further Apart? How Exposure to Media Portrayals of Muslims Affects Attitude Polarization. Political Psychology 41: 1055–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silk, Mark. 1998. Unsecular Media: Making News of Religion in America. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, Ain, and Kimberly Rios. 2017. The Moral Contents of Anti-Atheist Prejudice (and Why Atheists Should Care about It): The Moral Contents of Anti-Atheist Prejudice. European Journal of Social Psychology 47: 501–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, Ain, Caitlin McCurrie, and Kimberly Rios. 2019. Perceived Morality and Antiatheist Prejudice: A Replication and Extension. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 29: 172–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, Lawton K., and Martin Heesacker. 2012. Anti-Atheist Bias in the United States: Testing Two Critical Assumptions. Secularism and Nonreligion 1: 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taira, Teemu Patrik. 2015. Media and the Nonreligious. In Religion, Media, and Social Change. Edited by Kennet Granholm, Marcus Moberg and Sofia Sjö. New York: Routledge, pp. 110–25. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Rhiannon N., and Richard J. Crisp. 2010. Imagining Intergroup Contact Reduces Implicit Prejudice. British Journal of Social Psychology 49: 129–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Veen, A. Maurits, and Erik Bleich. 2021. A New Approach to Sentiment Analysis in the Social Sciences. Williamsburg, VA: Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo, Chris J., and Lei Guo. 2017. Networks, Big Data, and Intermedia Agenda Setting: An Analysis of Traditional, Partisan, and Emerging Online U.S. News. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 94: 1031–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, Joel, and Drew Westen. 2008. RATS, We Should Have Used Clinton: Subliminal Priming in Political Campaigns. Political Psychology 29: 631–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WIN-Gallup International. 2012. Global Index of Religiosity and Atheism. Zurich: Gallup International. [Google Scholar]

- Young, Lori, and Stuart N. Soroka. 2012. Affective News: The Automated Coding of Sentiment in Political Texts. Political Communication 29: 205–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenk, Thomas. 2012. Neuer Atheismus: New Atheism in Germany. Approaching Religion 2: 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zenk, Thomas. 2013. New Atheism. In The Oxford Handbook of Atheism. Edited by Stephen Bullivant and Michael Ruse. Oxford: OUP, pp. 245–60. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Xiaoqun. 2018. Intermedia Agenda-Setting Effect in Corporate News: Examining the Influence of the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal on Local Newspapers. Journal of Applied Journalism and Media Studies 7: 245–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).