1. Introduction

We lay on our backs on the smooth, warm reindeer fur. The air smells of the smoke from the fireplace, and the soft rhythms of the leather drum surround us. We are asked to reach for our spirit animals. Could it be the totemic bear of the past or the reindeer that has been offered to sacred stones for centuries?

Saami shamanism is a contemporary phenomenon with links to the past. To invoke “tradition” in order to legitimize one’s religious beliefs and practices is central to Western religious history, from antiquity to the present. The aspiration to activate the past contains a creativeness in which people continually construct their traditions, values, and myths and, thus, a connection in their own lives (see

Fjell 1998;

Selberg 1999). The importance of the past can be seen, for example, in the celebration of early religious holidays and in the use of old sacred places, as well as in the reconstructions of drums (

Jonuks and Äikäs 2019;

Joy 2020).

The idea of fusing together cultures to create a shamanic expression can be said to originate from Mircea Eliade who invested shamanism with its current meaning in Western religious practice. Eliade, through his extensive work

Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy (

Eliade 1964), transformed the term shamanism into an academic category sui generis and established a cross-cultural “classic” pattern of shamanism (see

Znamenski 2007).

The “shaman” is an example of the complexities often involved in translation processes over time and across space (see

Johnson and Kraft 2017). As

David Chidester (

2018, p. xi) points out, the shaman is a religious specialist that initially was identified in Siberia, colonized by Russia, and later transferred to a global arena. The term is widely regarded as having entered Russian from the Tungus

samán, transferring to German as

schamane, and then into other European languages in the seventeenth century. It was added to academic vocabularies by anthropologists and historians of religions and further related to indigenous people elsewhere (see

Wilson 2014, p. 117). In the 1960s, the term spread to the neo-pagan milieu, where the shaman is not only recognized as an indigenous religious specialist, but as a potential enshrined in all humans. Based on Eliade and on the works by the anthropologist

Carlos Castaneda (

1968) and

Michael Harner (

1980), a view of shamanism as the oldest and most primal form of spiritual practice emerged. According to these scholars, shamans are found in all “traditional” cultures, but in Europe and America, these traditions have been bolstered by emerging Christianity and later industrialization. Even though shamanic practices are shaped in relationship to contemporary Euro-American society and rooted in the mythology and symbolism of Western culture, they also include a critique of Western, industrialized society (

Fonneland 2010). Shamans aim to reconstruct a lifestyle that has been disrupted and threatened by the industrialization process. Thus, in these communities, nature represents a source of power, a door-opener for establishing contact with the magical and spiritual world, and the goal for the individual is to move forward in his or her own spiritual development by being in close contact with nature, which in shaman circles is described as a force that can be used for the cultivation of self. The idea is that nature has the power to “release” ancient energy and knowledge.

One way to get in contact with the forces of nature is through power animals. The concept, power animal, was introduced by Michael Harner in the book

The Way of the Shaman (

Harner 1980, pp. 57–72) and is inspired by animistic practices in cultures from all over the world. In shamanism, power animals are often connected to inner personal growth, and they can be reached with the help of drumming (

Boekhoven 2013, p. 245). Power animals can present themselves in immaterial forms by making an appearance in thoughts and dreams. However, they are also presented in a more material form via artwork and crafts. Art can be used to bring forth one’s power animals, and power animals can be used as motives in art and craft in order to create a bond to the depicted animal. Immaterial art forms such as dance can also include presentations of power animals.

Animals were essential in the old Saami worldview. Offering rituals were often negotiations for success in livelihood, especially in fishing, hunting, and later reindeer herding, with the offerings consisting mostly of animals, their meat, and antlers (

Äikäs 2015). The world around humans was seen to be inhabited by different actors with whom people could communicate: animals but also sacred stones (

sieidi, SaaN),

stallo giants, and

gufihtar (the invisible people). Drawings of animals were present on the

goavdásat, the Saami drums, which were used by ritual specialists,

noaiddit, but probably also by other people

1. According to several sources,

Noaiddit had help from

sáiva animals, guardian or helping spirits living in sacred lakes, but ordinary Saami could also come in contact with these spirits (

Hultkrantz 1987;

Pulkkinen 2005).

In the Saami worldviews, animals and all living creatures were seen as subjects, persons, and companions. (

Helander-Renvall 2008, 315–17, 330; also

de Castro 2004, p. 481) A worldview in which the relationship between humans, animals, and natural elements is seen as interactive has been called relational. Relational worldview is described by the idea that certain things that are considered non-living according to the current view had characteristics that made them a part of the network of social interactions. Spirits, animals, and natural elements were defined as living according to how they reacted and were reacted to (

de Castro 1998;

Bird-David 1999;

Herva 2006).

When searching for past traditions, animals have become a key concept within Saami shamanism, in the form of power animals that are said to be able to protect and guide the individual shamanic practitioner. Shamans in contemporary society, nevertheless, draw on a wide repertoire when looking for inspiration. Even though animals had a central position in Saami worldviews, the term “power animal” is not known from the sources depicting the old Saami religions. Sjamanforbundet (The Shamanistic Association), which in Norway is approved as an official religious association, equates it with the term “totem animals”—“spiritual beings that select human persons to follow and contact (during trance journeys or in other ways), and provide sources of wisdom, guidance and friendship.” (

http://sjamanforbundet.no/filosofi/2013/03/02/hva-er-totemdyr/, accessed on 30 March 2021). The Shamanistic Association emphasizes that even though there is no direct parallel to power animals in the old Saami worldviews, there are living beings with a similar function in both the Norse (

Fylgje) and Saami mythology:

In Saami they have several names (Noaidegàssi (Gadze) or Sueie are perhaps the most common). These can take the form of both a human and animal (and forms that are partially human and animal). Such helping spirits have different functions, but the common denominator is that they are there to provide learning, advice and guidance.

In this paper, we scrutinize the changing role of animals in Saami spirituality and how traces of the past are used in contemporary spirituality. We also explore how animals and their artistic presentations are entangled in shamanistic practices. Our data derive from material culture analyses, interviews, and participatory observations conducted at the shamanistic festival Isogaisa in Norway. Trude Fonneland has participated in the festival since it first opened its doors to the public in 2010. In 2017, we organized multidisciplinary fieldwork at Isogaisa together with Siv Ellen Kraft, Suzie Thomas, and Wesa Perttola with an aim to combine data gathered from the perspectives of religious sciences, heritage studies, and archaeology (

Äikäs et al. 2018). During this fieldwork, we conducted 15 semi-structured interviews with the festival participants and organizers.

2. Background: Isogaisa and Ritual Creativity

Shamanism is not a unified, organized movement, but a patchwork of shifting and elastic networks, stretching across both regional and national borders (

Fonneland 2010). There are still some events that can be said to act as focal points where shamans from all over the world meet to socialize and share their knowledge. The shaman festival Isogaisa is one such focal point. The festival saw the day of light in 2010 and has for the last ten years been arranged in the municipality of Loábak (Lavangen), Troms and Finnmark, northern Norway (

Figure 1).

Isogaisa provides a window to the processes of ritual creativity, which

Sabina Magliocco (

2014, p. 1) has defined as “the self-conscious crafting of new rituals, or the reinterpretation of existing ones, with the expressly subversive purpose of bringing about cultural change, in the context of both mainstream religions and new religious movements”. Creativity can include both invention of traditions and merging and fusion of traditions (

Palmisano and Pannofino 2017).

The Isogaisa festival is a clear example of how religious labels are formed in ever-changing contexts as a byproduct of broader historical processes. The festival can be described as a major venue for shamanic, as well as indigenous, religious meaning-making. According to the festival program, the motivation behind the festival is to unite an indigenous Saami worldview with modern ways of thinking and thus create “a spiritual meeting place where different cultures are fused together” (

https://isogaisa.org/, accessed on 31 March 2021).

At Isogaisa, different indigenous cultures and prehistorical traditions are highlighted as sources of inspiration for religious practice and an environmentally friendly relationship to the earth. This involves a projection of desired states or abilities of various indigenous populations, which are then perceived to provide the answer to what is experienced as an alienating and oppressive culture. What is expressed here are notions of a global indigenous spirituality, presented as a shared, symbolic repertoire for indigenous, as well as non-indigenous, people worldwide. Participants point out that this type of spirituality is colored by different local grounds, but, primarily, it is global and accessible to all. Presentations such as this are representative of how many non-native shamans choose to perform and market their services at the festival and reflect high regard for indigenous people and indigenous religious traditions in contemporary shamanism. This high regard has become increasingly visible since the late 1960s and is at present more prominent than ever. Isogaisa is precisely such a space where “performers, and audiences, public and individual subjects continually interact to shape emergent Indigenous identities” (

Graham and Penny 2014, p. 4). The Isogaisa festival in this perspective constitutes an intertwined stage where notions of being and belonging are recast.

Contemporary shamans’ use of indigenous spiritual customs and objects have become a source of concern to indigenous political bodies, artists, and communities. From the very start, consciousness about ecology and fascination with the world’s indigenous peoples have been central in contemporary shamanism. Indigeneity here appears increasingly as a form of cultural capital (

Bourdieu 1973), which is valued and considered worth pursuing, owning, and consuming. Both Saami and non-Saami practitioners of shamanism at Isogaisa are introduced to Saami traditions. At the festival, old and local traditions are merged with global discourses on pagan rituals, spirituality, and indigeneity, practiced by Saami and non-Saami alike, and incorporated in a contemporary shamanic context. Still, to avoid accusations of cultural appropriation and colonization, there is a reluctance to don Saami clothing and to use the

joik among shamans who cannot display Saami descent. Festival leader, Saami shaman Ronald Kvernmo, emphasizes that his ambition is to bring Saami spirituality to life, after years of condemnation. In his view the festival is a means for Saami people to retrieve and control their own spiritual heritage. The festival leader presents Isogaisa as a learning arena where a dynamic process of remembering brings elements from the past forth and where religious traditions that have been lost can be retrieved and shared through the festival.

3. Power Animals and Shamans

Power animals, also often called guardian spirits, have a central position in the rituals and ceremonies performed at Isogaisa.

Drawing on Harner, shamans at Isogaisa highlight power animals as necessary for any shamanic work. The power animals that Harner chose to highlight when developing core shamanism are animals with a high symbolic capital in Western culture and mythology: bears, foxes, deer, and porpoises, as well as dragons (see

Harner 1980). At Isogaisa, some of these spirits are accompanied by animals grounded in an Arctic fauna, such as the ice bear, the reindeer (and particularly the white reindeer), the polar fox, and the eagle. The preferred guardian spirits seem to be wild and physically powerful animals that are related to heroic images of strength, smartness, and wisdom. Domestication, in this perspective, stands out as a sign of loss of power with the semi-domesticated reindeer making an exception with its long roots of ritual symbolism (

Äikäs 2015;

Heino et al. 2020).

A shaman is said to have the ability to speak with animals, and some of them express that they can shapeshift into animal forms by using hallucinogens or a combination of dancing, drumming, and singing. Dancing, drumming, and singing also have an important role in the festival program at Isogaisa, whereas drugs are forbidden. Even though special reference to shapeshifting is not made, drumming is used as a technique to enable contact with power animals.

Lately, several shamans have begun to oppose Harner’s emphasis on powerful, wild animals. As shaman Kyrre Franck from the Shamanic Association argues: “I need to talk to you about spirit animals. You know wolf is getting overworked. And squirrel, well squirrel, he’s getting a bit lonely”. The Shamanic Association has also published an article about power animals on their homepage, which emphasizes domestic mythologies and traditions and relates power animals to a Nordic and Saami context: (

http://sjamanforbundet.no/filosofi/2013/03/02/hva-er-totemdyr/, accessed on 31 March 2021)

All humans have power animals. One animal we are born with, while some are with us for a shorter or longer period of time. The power animal that often comes to us during a drum journey is an animal that possesses qualities that we need to be able to survive and continue our life path.

Power animals choose a person they want to follow, a friend. You may think that I want an eagle because it is powerful to believe that you can choose them. The power animal will choose you and announce its presence to you, not the other way around. All you have to do is pay attention. Having a power animal means that you have something to learn and you also have a powerful friend.

Our domestic mythologies and traditions have many helpers. They are often known as little people, elves, goblins or gufihtar and other names. All are the creatures that have coexisted with man at all times. If we stay with them, they are a great help to us, but you should not upset them. The helpers also include the ancestors. Every step we take is supported by generation after generation with ancestors, so it is important to take care of the inheritance after them.

The Shamanistic Association opens the category of “power animals” to a broader content, also embracing domestic mythological beings such as gufihtar and ancestors. In addition, the power animals’ agency is emphasized. They are spiritual powers that themselves choose to appear or not and who can be upset if man acts in certain ways. The personal connection to one’s power animal and the role of the power animal in presenting oneself is also evident at Isogaisa. The festival goers are told that each and every one of us can have a power animal. A relation to power animals is not restricted to shamans but can be achieved by all genuine spiritual seekers. This is an example of the universalizing turn within contemporary shamanism where spiritual concepts are presented as a shared symbolic repertoire.

In our interviews with festival participants, they emphasized the shamanistic interpretation of power animals as individual helpers. No connection to Saami mythology was made with the exact framing of the words power animal. The festival promotes an agenda of emphasizing local roots and local connections. Our interviewees embraced both Saami and Norse traditions and underlined how important it is to connect to the Saami and Norse ways, for example, by talking about following the traditions of their ancestors. Similar mixing of elements from Saami and Norse traditions is evident on the top of Offerholmen, Norway, where a stick with carved runes is found at a Saami sacred site, which has been interpreted as a possible sign of contemporary pagan practices at the site (

Äikäs and Spangen 2016). Saami and Norse traditions have been connected for centuries; for example, Germanic runes were used in Saami areas and by Saami people in the Middle Ages (

Price 2001;

Äikäs and Spangen 2016, p. 12). On the other hand, to connect to both Norse and Saami traditions can be seen as a strategy of inclusion that dissolves the taxonomies of insider and outsider and of who has access to the traditions of the past. Norse traditions were eliminated by the expansion of Christianity; practitioners can thus see themselves not as oppressors, but as victims of the same forces that have marginalized indigenous peoples. As

Magliocco (

2004, p. 233) argues, this bit of historical revision is a powerful metaphor, which underlies their identification with oppressed or marginalized peoples: “Oppression such as that suffered by indigenous peoples at the hands of colonizers becomes an indicator of genuine spiritual knowledge or power—the same kind of spiritual authenticity they imagine pre-Christian European peoples must have had”.

At Isogaisa, the scenery, with its plains, lakes, and mountains, is interpreted as an open door into the world of the ancestors and the power animals. The landscape is interpreted as having the imprints and traces of the ancestors and the power animals, and this crossover between time and space gives places a touch of mystery. The interviews show how local pasts, places, and characters are woven into global discourses on shamanism, and in this melting pot, new forms of religion are taking shape.

The various cultural performances that are expressed at the festival can be simultaneously commodities, spiritual rituals, and transformative political projects: “these are not necessarily mutually exclusive, nor are they without occasional contradictions and tensions” (

Phipps 2009, pp. 32–33). Isogaisa, with its seminars, fair, and ceremonies, is similar to other festivals in that it is a place for socializing, enjoyment, and leisure; nevertheless, it is also a place where the local and global are merged, where power relationships come into play, where political interests are materialized, where cultural identities are tested, and where new visions take shape.

4. Staging Power Animals at Isogaisa

Sarah M. Pike (

2001) notes that Pagan identities are primarily expressed at festivals through music and dance. According to Pike, shamanic identities are performative. They seek to control the impression they make upon others in ways that vary according to the context. It is primarily at festivals and other major happenings that the performance of a shamanic identity reaches a peak point concerning both costuming and performances. This is highly relevant in terms of what is expressed at Isogaisa. From start to finish, Isogaisa is a festival packed with shamanistic ceremonies, rituals, and performances. Participants and performers dress up in clothing inspired by indigenous customs, indigenous religions are sought to be revitalized along with traditional handcraft, such as the making of ritual drums, and people taking part in the festival week have the opportunity to explore and cultivate their shamanic identities. Power animals are intertwined in all these performances, as they are approached via drumming and depicted in clothing and dancing.

One artist at Isogaisa is Saami musician Elin Kåven (

Figure 2), a Saami recording artist, who, for ten years, has aimed to bring listeners into the Arctic sphere of shamanic folklore and the mythology of Saami people. Through her music, she manifests the mythological creatures from the Arctic, and her concerts are described as fairy tales in notes. When performing at Isogaisa, Kåven, wears a pair of reindeer antlers on her head, and through dance and

joik, she highlights the reindeer’s movements and qualities.

2 Kåven’s choice of costume and adornment adds to a bond between power animals, ritual creativity, and shamanism. Kåven is also behind the Isogaisa festival dance. The dance was published on YouTube and on the Isogaisa homepage prior to the festival in 2011, and people are encouraged to learn the steps before arriving at the festival (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wXxqa_BJCOs, (accessed on 31 March 2021). Kåven describes the meaning of the dance and its connection to Saami tradition as follows:

I was asked to make a dance for the upcoming Isogaisa festival this year 26–28 august. The idea is that people will learn this dance before they come, or at the festival, and whenever they hear this song at the festival people can start dancing it. This dance is easy to learn, suits everyone, and has very typical Sami moves

The dance, which is accompanied by a

joik, imitates the journey to the Isogaisa festival by mimicking the movements and sounds of various Arctic animals and the natural elements. The

joik and dance portray the sparrow, the bear, the reindeer, the eagle, the sun, and the water and pictures Isogaisa as a power center where the animals and natural elements seek to gather. In the festival area, the dance imitating the animals’ movements and the

joik contribute to a sense of community and a bond to the portrayed natural elements and animals. The simple dance steps symbolize a project of coming together, in which participants of all age groups can take part according to their abilities. The Isogaisa dance and

joik also serve to highlight how formerly taboo cultural expressions, such as the

joik3, are currently entering popular culture. This was also evident as Kåven performed in the Eurovision Song Contest final in 2017 in a duo “Elin & The Woods”. In the performance, a

joik, a Saami shaman drum, and three “spirit animals”—a polar fox, a wolf, and a reindeer/stag—were present (

Kalvig 2020).

Isogaisa acts as a contact zone where people negotiate their identities, among other things through clothing. At the festival, shamans such as Lone Beate Ebeltoft through her design firm, Alveskogen, market new clothes and accessories inspired by the Middle Ages and Arctic indigenous clothing. Motifs from the animal world such as wolves, bears, eagles, and reindeer combined with Saami symbols found on drums, as well as symbols from prehistoric rock art, are depicted on the clothes and accessories that are sold at the festival. These clothes are popular among shamanic practitioners.

Miller (

2010, p. 136) states that “It is usually through the medium of things that we actually make people”. At Isogaisa, clothing does not represent people, but actually constitutes who they are. Ebeltoft herself underlines in our interview that, “Many people, inspired by Harner and his core shamanism, would choose a large, powerful animal like the bear, the eagle, and the wolf, and by decorating clothes with these animals, they would highlight and claim their ‘shamanistic identity’”. However, Ebeltoft also adds that in part of the Saami environment, this has been considered as something negative:

Some people criticized this type of design. They pointed out that it was unrighteous to have symbols on the clothes, and especially symbols of animals and from nature. In the old noaidi tradition, there was a saying that the most powerful noaiddit could bind an animal spirit to themselves and use this spirit as a helper in the spiritual world. Also the noaidi could send his or her free soul into a living animal, a bird, a fish, or an insect, and partly control it to find out things and gain insight. I still do not see many Saami shamans who put animal symbols on their clothes, but an awakening is happening right now. Due to the increasing presentation of Saami symbols in social media, more people request clothes with these kinds of motifs.

(Interview with Lone Beate Ebeltoft, February 2021).

An example of this change is a

luhkka (a Saami cloak with a hood) that Ebeltoft designed on commission by Saami shaman Eirik Myrhaug’s students for his 70th birthday in 2013. The

luhkka is decorated with the Saami

beaivi (sun) symbol on the front and a

noaidi symbol on the back (

Figure 3a,b). Ebeltoft’s clothes and design point to a material engagement in the production of Saami shamanism (see also

Kalvig 2020), in which contested symbols with roots in the pasts are highlighted to form shamanic identities in the present.

4 The symbols on the clothes show how global shamanic concepts and practices connected to power animals are slowly translated to a local Saami context and function as trademarks for shamanic identity.

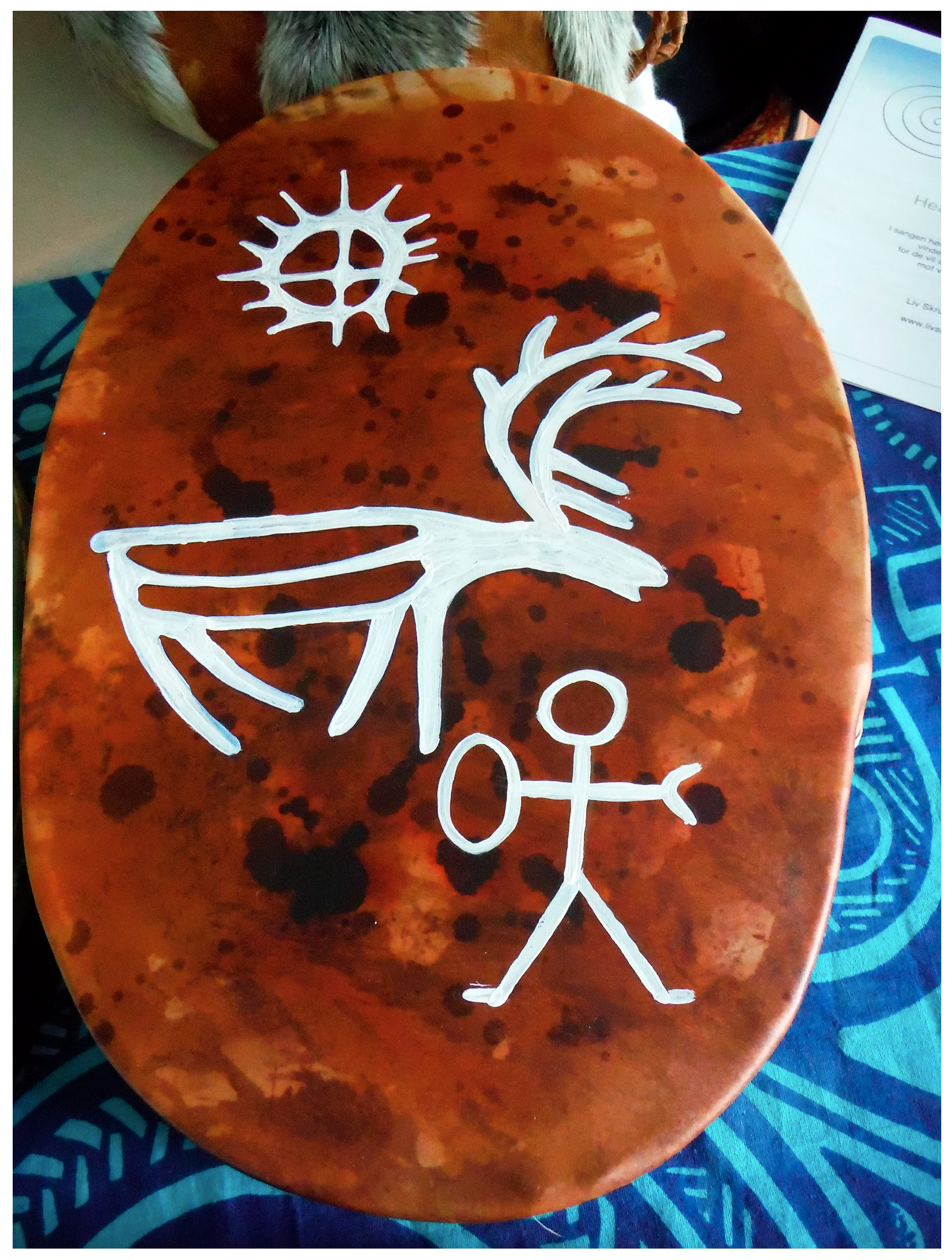

Power animals are not used as decorative motifs only on clothes, but also on Saami drums,

goavddis (SaaN). Professional

duodji (Saami traditional handcraft) artist, Fredrik Prost from Viikusjärvi—a small village in the northernmost part of Sweden—has held several workshops in the making of ritual drums at Isogaisa. Prost trains participants for three days in creating their own ritual drums inspired by the traditional Saami

goavddis. These drums, according to festival organizer Ronald Kvernmo: “Will be very special and exclusive drums with enormous energy”. On the other hand, ready-made drums are also sold at Isogaisa (

Figure 4). These also contain depictions of power animals. Selling ready-made

goavddis can be seen to democratize the spiritual experience as it also makes the drums available to those who do not have the time or ability to make one (cf.

Meskell 2004, pp. 177–219), but in the drum-making course, the personal relationship with the drum is emphasized as an important feature.

The old ritual practices at

sieiddit are mainly evident in archaeological data and written sources, the latter which date to the late period of the use of the offering places. Written sources depict that rituals at

sieiddit could include joiking, slaughtering an animal, and eating at the

sieidi (

Äimä 1903;

Paulaharju [1922] 1962). The offerings consisted mostly of animal offerings. In some cases, alive animals were left at the

sieidi, but more often, meat, bones, or antlers were offered. Offered animals were often connected to livelihood, such as fish, birds, sheep/goat, deer, and reindeer (

Äikäs 2015).

Through Isogaisa, parts of old Saami religious practices and symbols are incorporated into new contexts and interpretive frames. One such symbol is the sieidi and the heritage site Rikkagallo. Every year since 2012, during the festival, shaman Eirik Myrhaug has organized a hike to the sieidi to conduct a ritual inspired by the traditions of his Saami ancestors.

On the first page of the note that Myrhaug hands out to the participants is a story about Rikkagallo written by

Carl Schøyen (

1943):

Right in the valley where people, reindeer and dogs had their trails, the nomadic “Lapps” [sic] did sacrificial offerings to big stones deeply embedded in the soil, stones that never had been touched by human iron-tools but rough and untouched by God’s hand. Vuoitas-gallo, the anointed stone stands in Budalsskaret close to the water drain, tall and freighting and surrounded by the cold from the springs that fall in the shadow of the mountain. Different is the accursed stone, Rikkagallo—it dwells heavy and resting as well as open in its own valley close north of Harvečokka. In addition other sacrificial stones existed—and with these, in our landscape, the nomads rested, they splattered these with reindeer blood, and to these stones they brought animals antlers and other gifts, while begging the God in the stone for luck, prosperity and good fortune (reindeer luck) on the summer trails. These stones in addition had an outreached hearing capacity, supporting the Lapps’ ability to call upon the stone from miles away and out in the sea-mountains, turning to the east and after joiking (chanting) to these stones they would strengthen their capacity and prosperity for their herd.

The story strongly binds the trip to Rikkagallo to old Saami offering traditions and especially to the lifestyles of reindeer herding Saami. It also describes stones as interacting entities in the Saami landscape.

On the journey to Rikkagallo, the participants are advised to reach for their power animals, which could present themselves during the walk. Hence, animals are part of the whole journey, not just at the offering site, and the journey itself is highlighted as important, not just the ritual at the sieidi. This became evident when the first author was forced to turn back halfway due to the difficulty of the terrain combined with her pregnancy, and she was told that this was her journey and meaningful as such. The connection with a sieidi and personally meaningful animals was highlighted in one of the interviews: “My uncle he talks about that every day I should go there [to the family sieidi], and I will go there […], I’m really looking forward to go[ing] there. And to see the white hawk who’s there. It’s my grandfather’s, well every time he was there, the white hawk was there”.

Before the offering ritual at Rikkagallo, Myrhaug gathers the group in a circle, and with the use of a bird wing and sage smoke, he cleanses each participant (

Figure 5). Then, the forces from all directions are invoked. Myrhaug calls on the serpent from the south, the white reindeer from the north, the polar bear from the east, the eagle from the west, mother earth, and the forces within the human world. This call is a regular feature that introduces many of the ceremonies and rituals at the shaman festival of Isogaisa and can be seen as part of an established repertoire of shamanistic rituals. After the forces have been summoned, participants go to the stone and make their personal sacrifice by throwing a gift into a large crack in the

sieidi.

Animals have typically been sacrificed at

sieidi stones (

Äikäs 2015). During the Isogaisa festival, offerings were also made to the fire in the middle of the main festival

lavvu. As in the old Saami worldview, here, some offerings were also related to livelihood. One of the interviewees told us how he made an offering to the fire when he was preparing food—for example, meat. When he arrived at the festival, some moose hunters had killed a moose, and together, they gave some of it to the mountain, to the earth, and to the fire. He told us that he also made offerings when he was hunting: “And when I play a drum, I hunt, I go out into the woods at night and make offerings, make fire, ask for, for good hunting. […] So I can offer the heart of the animal, usually I offer that. I dry it, salt it, dry it, keep it…”. One of the interviewees told us how the relation to the offered animals had nevertheless changed: “I sometimes use blood, you know blood. And that blood can come from me or it can come […] from the shop. You know today you won’t have to cut the head out of something. You can buy the blood from the shop. It’s very modern”.

Buying blood does not diminish the ritual’s importance but makes this kind of offering more accessible to those who do not want to kill an animal or who do not have the means to hunt, similar to the ready-made drums. A personal connection to one’s power animal could also be attempted in the sense

lavvu (a Saami tent) in the festival area, where festival goers could relax and try to evoke their senses. There, participants are asked to close their eyes, listen to the drumming, feel the warmth of the fire, and try to connect to their personal power animal (cf.

Boekhoven 2013, p. 245). Some of the participants described seeing or feeling the presence of a power animal. Here, power animals are connected to a multisensoral bodily experience of the festival goers. Thus, the relaxing atmosphere of the sense

lavvu is more of a retreat from the modern rhythm of life than in any way connected to past ritual traditions.

5. Conclusions

Our article shows how material culture plays a central role in tying together Saami traditions and contemporary shamanistic practices. At Isogaisa, the traditional Saami drums,

goavddis, the Saami

sieidi, clothes, dance, and the

joik are used as the basis for new constructs, and they become symbols of continuity with the traditions of the past. In shaping their festival drums, taking part in an offering at the

sieidi, and learning to

joik, Isogaisa provides the festival attendants with access to a first-hand personal taste of the past. The “objects”, the Saami drum,

sieidi, and the

joik are, in this context, messengers that enable a dialogue between the past and the present. As folklorist

Jonas Frykman (

2002, p. 49) says about the role of objects in cultural production: “Things like this—and many more—have become something more than symbols. They bear secrets and have to be induced to speak”. At Isogaisa, the performances, objects, and spiritual beings are ascribed to indigenous “characteristics” that are associated with an indigenous past that has significance in the present.

This article highlights how the role of power animals is intertwined with the use of traditional objects in ritual creativity. Power animals are present in many forms—both material and immaterial. They are approached in thoughts, music, and dance, but also depicted in drums and on clothes. Together with power animals, the role of offered animals takes multiple forms from self-hunted game to bought blood. At sieidi offering sites, various non-human actors are present: the offered animals, power animals, and other spirit animals.

The sieidi is an example of the importance of the past, not just as material traces, but as living ideas. Even though during the festival, an old offering site was visited, some of the interviewees told us that for them it was not important to visit old sieiddit but to find their own sieidi places as their forefathers had done: “In my belief, you make your own sacred places. Because when my ancestors were shamans and they had a sacred place they built themselves. And I have my sacred place, in my place. So, it’s, I don’t think it’s necessary to go to the old ones when you can make your own”. However, the past also had its value; another interviewee said that there is special energy at places that have been used for centuries. She added that places can become important because of an individual connection or because they have been acknowledged by multiple people for many generations.

Similarly, the importance of reindeer and bears as power animals emphasizes the connection to past traditions. Reindeer have been the most important offerings since the fifteenth century. Semi-domesticated reindeer replaced wild deer as an offering material at a time when the herding was at its early stage in the area (

Heino et al. 2020). Hence, it was ritually significant already before it became an important part of livelihood. As a semi-domesticated animal, reindeer set themselves apart from the idea of wild power animals. The ritual meaning of the bear is evident both in bear offerings, the bear cult, and in special bear graves (

Äikäs 2015;

Piha 2020). However, animals with no historical background as ritual animals have also gained the role of power animals in contemporary shamanic practices, such as wolves and squirrels.

Ritual creativity and the use of new symbolic animals can be seen as a way to democratize rituals and make them available to all. New offering traditions, such as buying blood, the commercial distribution of drums and clothes with power animal symbols, and festival dances performed on YouTube, make it easier for people to participate in these ritual activities and to highlight their shamanic identity. At Isogaisa, there are different actors performing spiritual relations to animals in various ways. The organizers created an arena that enable the merging of shamanistic elements from different parts of the world. They encouraged a symbiotic view of shamanism, where not only different indigenous traditions, but also different religions meet. Not all festival goers identified themselves as shamans, but they had a background in, for example, nature religions, Norse ways, and Catholicism, with others coming in search of their spirituality and/or as spiritual tourists. The performers each brought to the venue their personal way of performing shamanism and interacting with animals. These varied from personal experiences in the sense lavvu to performances organized for festival goers, as well as to commercial activities. At Isogaisa, people communicate with the animated world around them in various ways, including offerings to the sieidi and to the fire and seeking a connection to power animals. Spirituality, art, and animals are intertwined in the festival dance, drumming, and decorative use of animal motifs in clothes and drums. Influences from the past and ritual creativity are entangled as people personalize such rituals. The role of personal experience is central; the sieiddit and power animals choose people and present themselves to individuals. Power animals were present in many ceremonies, performances, and rituals, as well as in the decorations of the drums and clothes. People were encouraged to find their power animals during the festival and present them in different artistic ways from clothes to dance. At the festival, art, shamanism, and animism are re-deployed in creative ways to empower the individual participant, as well as the shamanic community. Animals are given new meanings through their use as decorative elements in clothes, as well as through their inclusion in performances, from offering rituals to the festival dance.