The Lutheran Military Chaplaincy in the Finnish Defence Forces’ Organisation Today. A Multi-Method Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Finnish Defence Forces as an Organisation and the Military Chaplains’ Position in It

3. The Change in the Operational Environment in the FDF’s Personnel Strategy

4. Research Procedures and Data Analysis

- SUM_durability (α = 0.713) referred to 5 items that focused on personal determination, discipline, and ability to bear pressure

- SUM_demands (α = 0.749) referred to 8 items concentrating on the expectations of the demands for the management of the profession in future

- SUM_less_interaction (α = 0.897) had 3 items that described the future expectations concerning decrease in interaction and feedback

- SUM_religious_calling (α = 0.910) consisted of 11 items describing religious aspects of vocation

- SUM_traditionalist (α = 0.835) included 3 items that focused patriotism, honouring traditions and obedience to authorities

- SUM_altruist (α = 0.535) included 2 items focusing on helping people in need

- SUM_religious_career (α = 0.776) had 5 items that described the reasons connected to religion in career choice

- SUM_personal_career (α = 0.680) referred to 4 items concentrating on individualistic purposes in career choices

- SUM_changes_tasks (α = 0.492) included 2 items that described how changes in society and globally affects the tasks of the military chaplain.

5. Results

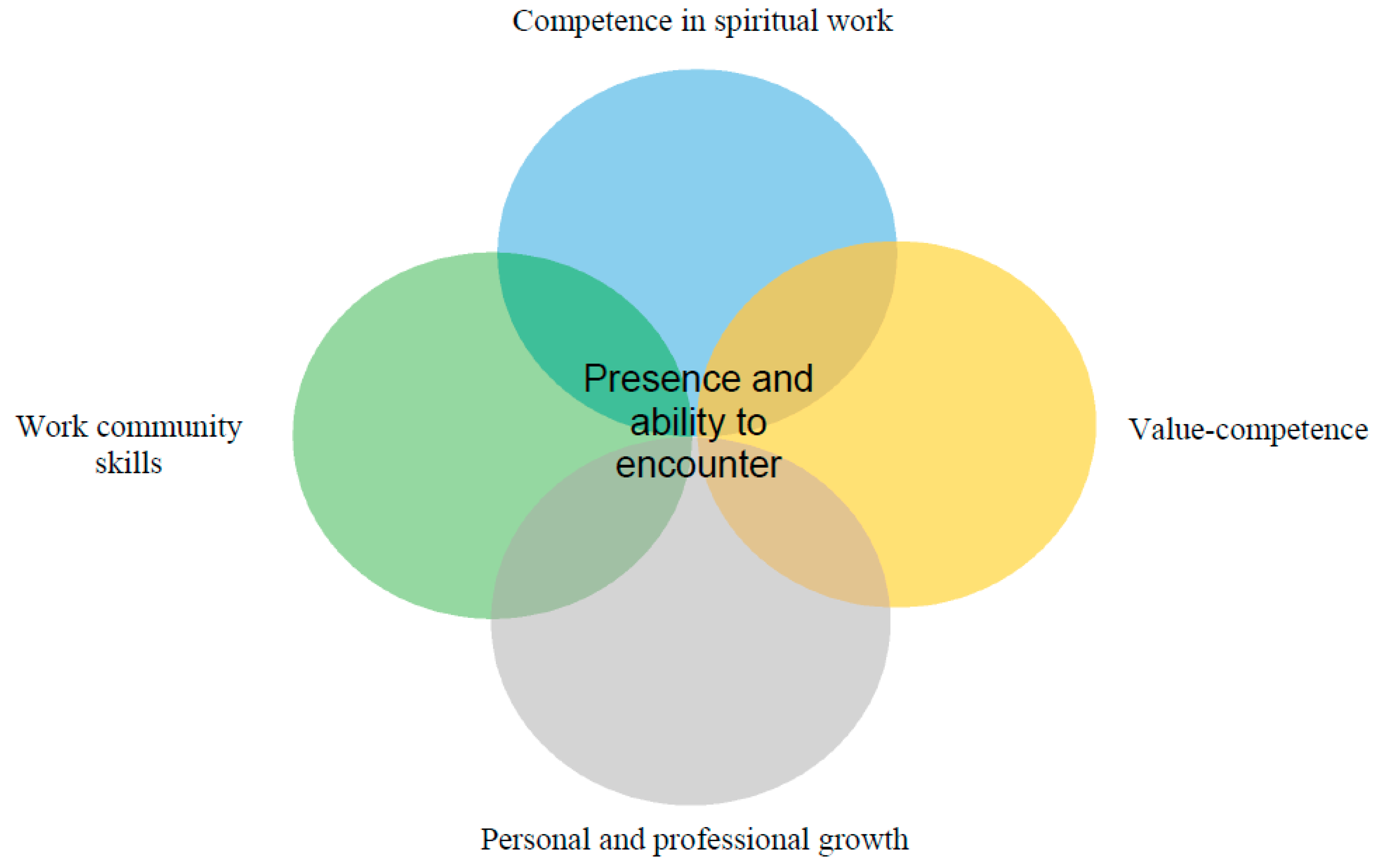

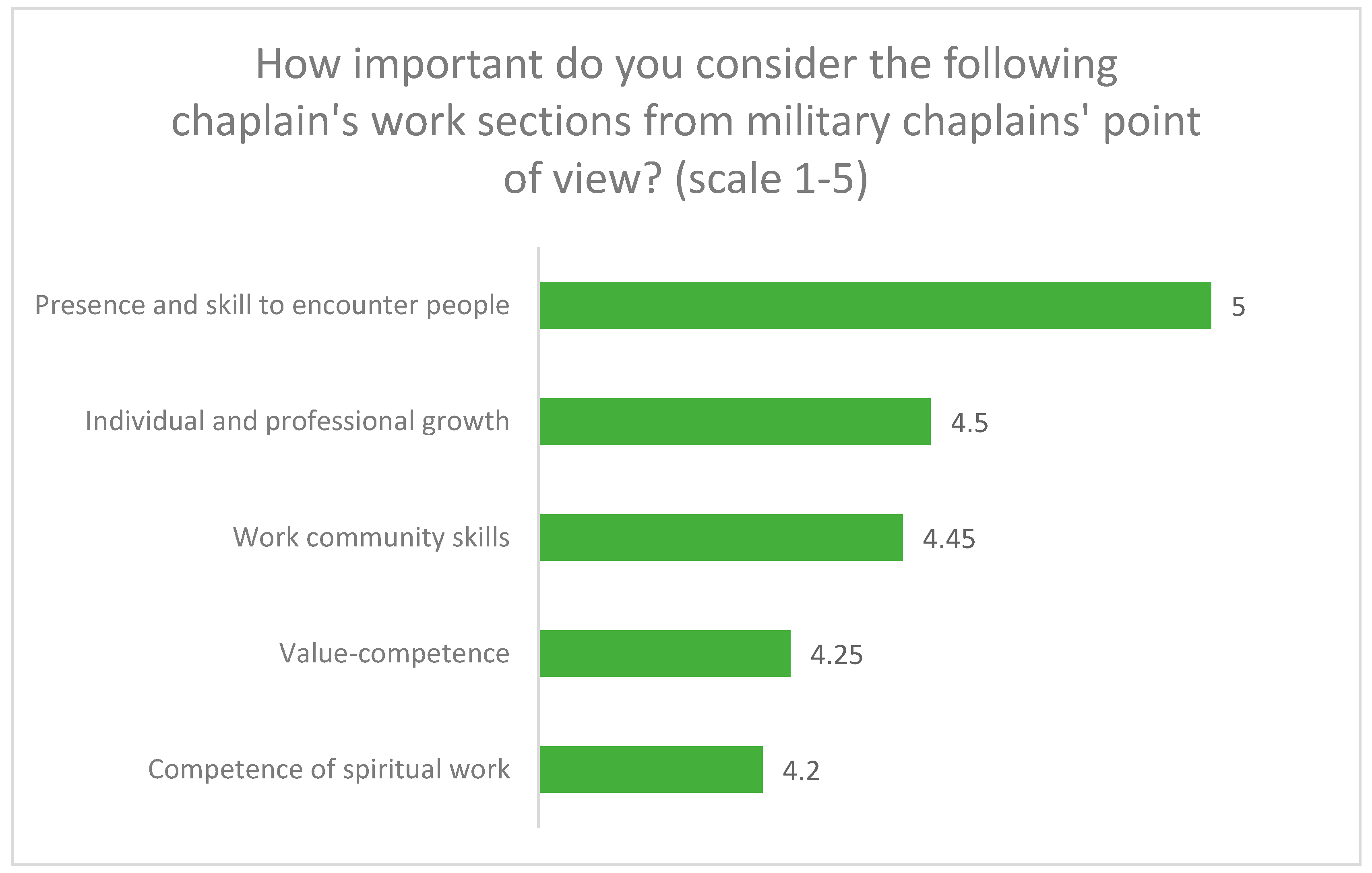

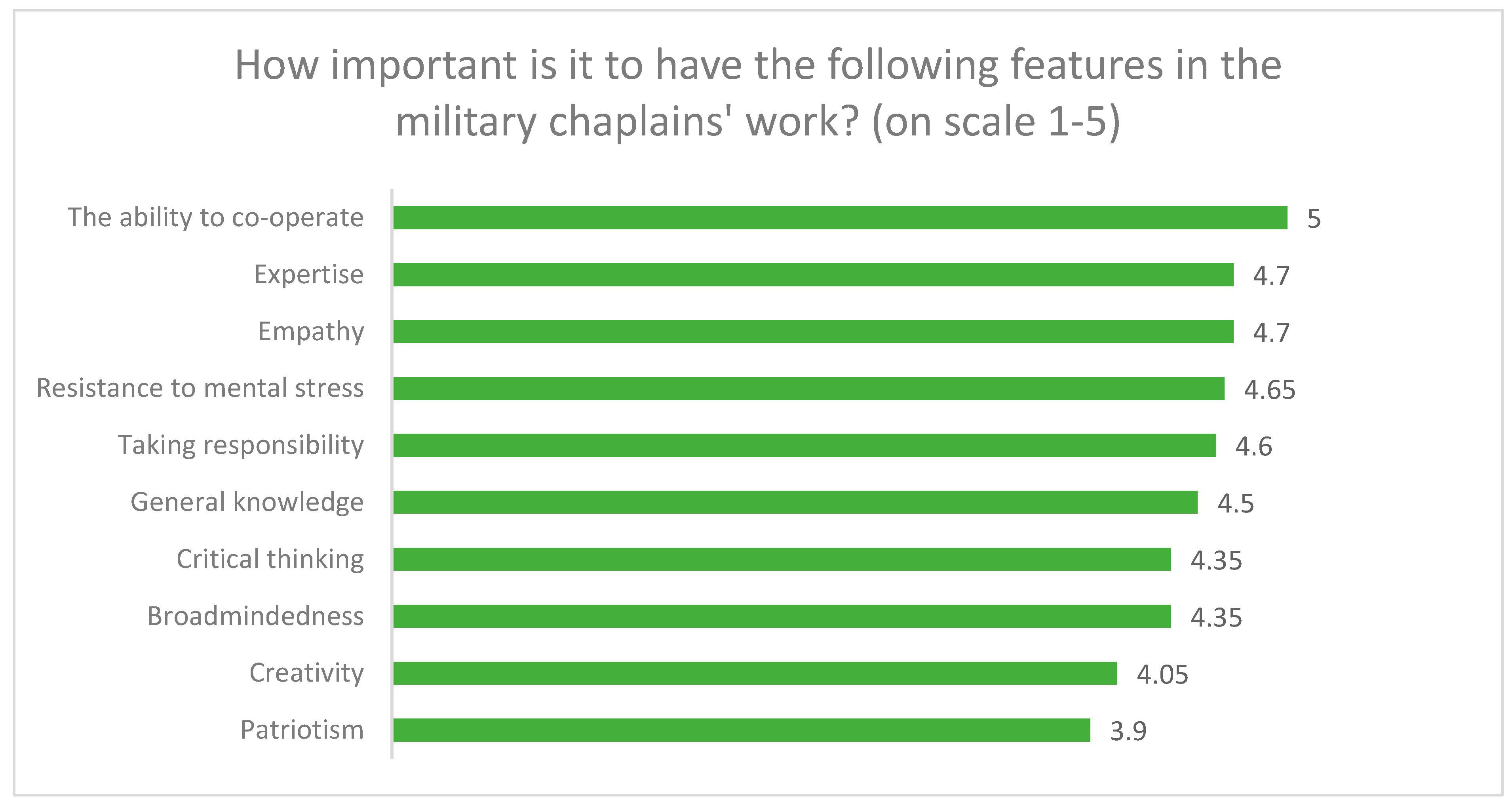

5.1. What Does It Take to Be “a Good Chaplain”?

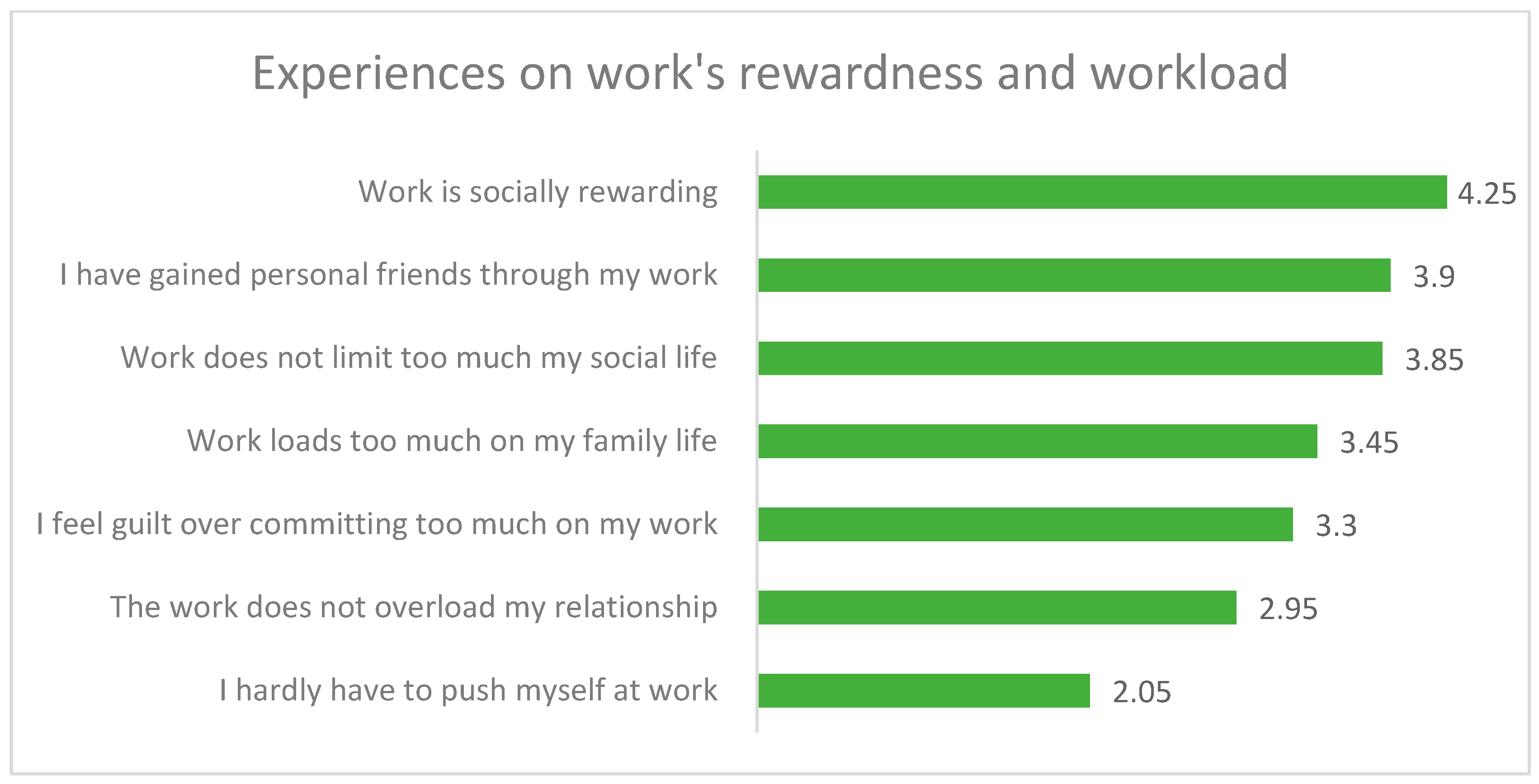

5.2. How Do the Military Chaplains Perceive Their Work?

5.3. How Do the Military Chaplains Reflect Their Religious Vocation with the Function of Military?

5.4. How Do the Military Chaplains Perceive Daily Tasks Related to Religion?

6. The Perceptions of the Future of the Profession of the Military Chaplaincy

7. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Reliability Statistics of the Summed Variables

Appendix A.1. SUM_Durability

| Reliability Statistics | |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | N of Items |

| 0.713 | 5 |

| Item-Total Statistics | ||||

| Scale Mean if Item Deleted | Scale Variance if Item Deleted | Corrected Item-Total Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha if Item Deleted | |

| 5F1 How important is it to have the following features in military chaplain’s work? Disciplinity | 16.80 | 3.642 | 0.485 | 0.669 |

| 5F2 How important is it to have the following features in military chaplain’s work? Resolve | 16.80 | 2.695 | 0.628 | 0.591 |

| 5F3 How important is it to have the following features in military chaplain’s work? Empathy | 15.75 | 3.461 | 0.632 | 0.627 |

| 5F9 How important is it to have the following features in military chaplain’s work? Resistance to physical stress | 16.65 | 2.766 | 0.478 | 0.677 |

| 5F10 How important is it to have the following features in military chaplain’s work? Resistance to mental stress | 15.80 | 3.853 | 0.256 | 0.741 |

Appendix A.2. SUM_Demands

| Reliability Statistics | |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | N of Items |

| 0.749 | 8 |

| Item-Total Statistics | ||||

| Scale Mean if Item Deleted | Scale Variance if Item Deleted | Corrected Item-Total Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha if Item Deleted | |

| 9F1 In my view, in the future: Changing work descriptions will increase the need for additional training for those who are already in work | 25.60 | 11.095 | 0.717 | 0.665 |

| 9F2 In my view, in the future: Increased language skills are required from the military chaplains | 26.20 | 9.958 | 0.725 | 0.654 |

| 9F3 In my view, in the future: More knowledge of other religions are required from the military chaplains | 25.85 | 11.818 | 0.646 | 0.684 |

| 9F4 In my view, in the future: The requirements for military chaplain’s education and profession increases | 25.60 | 13.516 | 0.424 | 0.727 |

| 9F8 In my view, in the future: The demands towards work increase | 25.60 | 14.568 | 0.457 | 0.734 |

| 9F12 In my view, in the future: Workload increases | 26.20 | 13.642 | 0.352 | 0.739 |

| 9F13 In my view, in the future: The work loads more | 26.20 | 14.905 | 0.093 | 0.783 |

| 9F14 In my view, in the future: I will get less feedback from my supervisors | 27.35 | 13.082 | 0.289 | 0.759 |

Appendix A.3. SUM_less_Interaction

| Reliability Statistics | |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | N of Items |

| 0.897 | 3 |

| Item-Total Statistics | ||||

| Scale Mean if Item Deleted | Scale Variance if Item Deleted | Corrected Item-Total Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha if Item Deleted | |

| 9F11 In my view, in the future: Interaction between people decreases | 4.90 | 3.253 | 0.738 | 0.903 |

| 9F14 In my view, in the future: I will get less feedback from my supervisors | 4.90 | 2.937 | 0.796 | 0.857 |

| 9F15 In my view, in the future: I will get less feedback from my colleagues | 4.90 | 3.147 | 0.866 | 0.799 |

Appendix B. The Survey Tables

| Descriptive Statistics | |||

| N | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

| Presence and skill to encounter people | 20 | 5.00 | 0.000 |

| Individual and professional growth | 20 | 4.50 | 0.513 |

| Work community skills | 20 | 4.45 | 0.510 |

| Value-competence | 20 | 4.25 | 0.550 |

| Competence of spiritual work | 20 | 4.20 | 1.056 |

| Valid N (listwise) | 20 | ||

| Descriptive Statistics | |||

| N | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

| The ability to co-operate | 20 | 5.00 | 0.000 |

| Expertise | 20 | 4.70 | 0.470 |

| Empathy | 20 | 4.70 | 0.470 |

| Resistance to mental stress | 20 | 4.65 | 0.587 |

| Taking responsibility | 20 | 4.60 | 0.598 |

| General knowledge | 20 | 4.50 | 0.513 |

| Critical thinking | 20 | 4.35 | 0.671 |

| Broadmindedness | 20 | 4.35 | 0.671 |

| Creativity | 20 | 4.05 | 0.686 |

| Patriotism | 20 | 3.90 | 0.912 |

| Respect for the traditions | 20 | 3.85 | 0.745 |

| Resistance to physical stress | 20 | 3.80 | 0.834 |

| The ability to make friends easily | 20 | 3.80 | 0.768 |

| Readiness for sacrifices | 20 | 3.70 | 0.865 |

| Resolve | 20 | 3.65 | 0.745 |

| Disciplinity | 20 | 3.65 | 0.489 |

| Determination | 20 | 3.60 | 0.754 |

| Obedience to the authorities | 20 | 3.30 | 0.801 |

| Leadership | 20 | 3.20 | 1.056 |

| Valid N (listwise) | 20 | ||

| Descriptive Statistics | |||

| N | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

| Work is socially rewarding | 20 | 4.25 | 0.550 |

| I have gained personal friends through my work | 20 | 3.90 | 1.071 |

| Work does not limit too much my social life | 20 | 3.85 | 1.137 |

| Work loads too much on my family life | 20 | 3.45 | 1.050 |

| I feel guilt over committing too much on my work | 20 | 3.30 | 1.031 |

| The work does not overload my relationship | 20 | 2.95 | 0.945 |

| I hardly have to push myself at work | 20 | 2.05 | 0.999 |

| Valid N (listwise) | 20 | ||

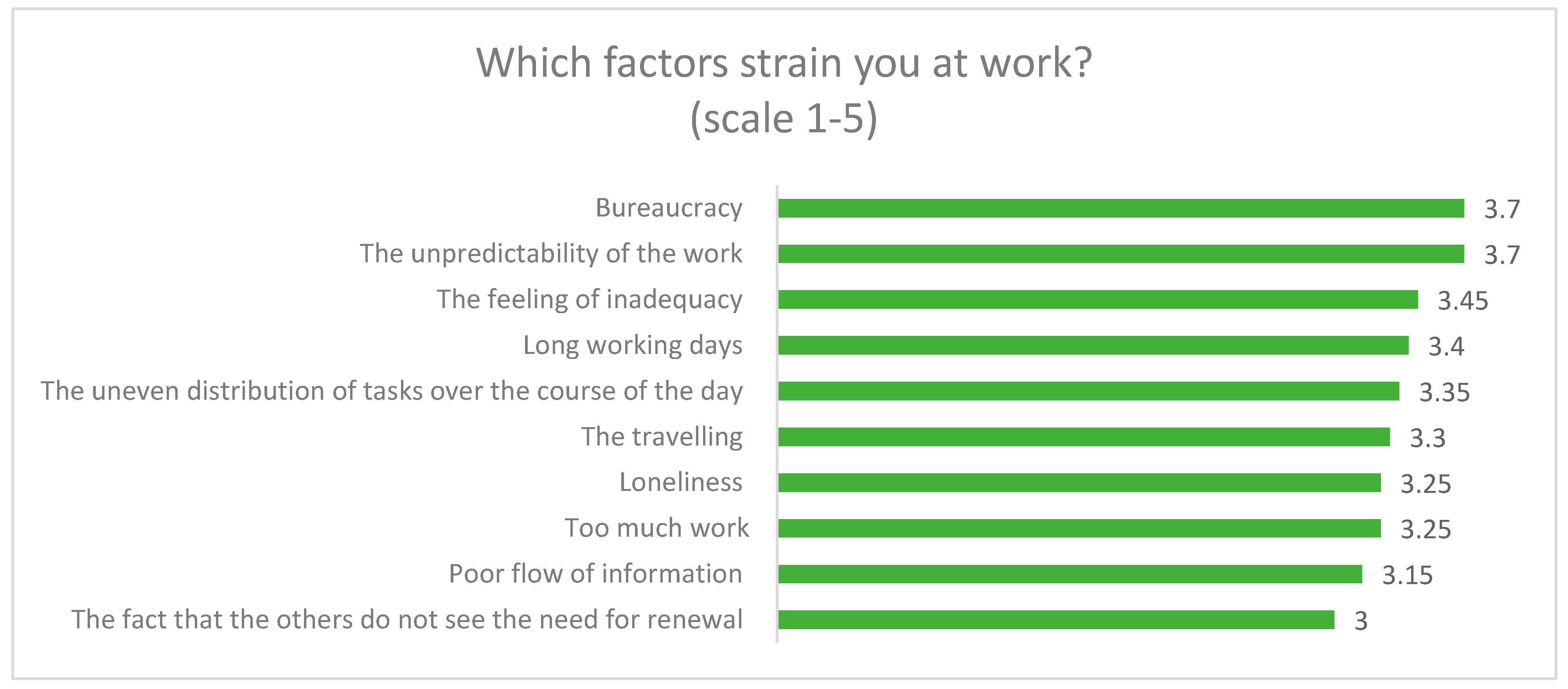

| Descriptive Statistics | |||

| N | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

| Bureaucracy | 20 | 3.70 | 0.801 |

| The unpredictability of the work | 20 | 3.70 | 0.801 |

| The feeling of inadequacy | 20 | 3.45 | 1.050 |

| Long working days | 20 | 3.40 | 0.821 |

| The uneven distribution of tasks over the course of the day | 20 | 3.35 | 1.089 |

| The travelling | 20 | 3.30 | 0.979 |

| Loneliness | 20 | 3.25 | 1.070 |

| Too much work | 20 | 3.25 | 1.020 |

| Poor flow of information | 20 | 3.15 | 1.226 |

| The fact that the others do not see the need for renewal | 20 | 3.00 | 1.124 |

| The lack of co-operation | 20 | 2.95 | 1.234 |

| Church’s secularisation, slipping from the basic task | 20 | 2.80 | 1.473 |

| Disadvantages of decision-making/design | 20 | 2.80 | 1.056 |

| The use of information technology (it) | 20 | 2.75 | 1.251 |

| Pressures for change | 20 | 2.75 | 1.070 |

| Challenges regarding the management | 20 | 2.70 | 1.261 |

| The difficulty of combining work and family life | 20 | 2.70 | 1.129 |

| Planning and organisation | 20 | 2.60 | 1.142 |

| Meetings and conferences | 20 | 2.60 | 0.995 |

| Encountering people | 20 | 2.60 | 1.273 |

| To get stuck in the routines | 20 | 2.55 | 1.146 |

| Other personal reasons | 20 | 2.50 | 1.277 |

| The lack of employees | 20 | 2.45 | 1.146 |

| Lack of guidance and support | 20 | 2.40 | 1.188 |

| Doing work that is not related to my field | 20 | 2.25 | 1.251 |

| To adopt new things | 20 | 2.25 | 1.020 |

| Poor management | 20 | 2.25 | 1.293 |

| The lack of holidays | 20 | 2.15 | 0.933 |

| Lack of motivation | 20 | 2.05 | 1.317 |

| The feeling that you can not influence on your job desricption | 20 | 2.00 | 0.973 |

| Lack of appreciation by subordinates/co-workers | 20 | 1.95 | 1.050 |

| Appearance | 20 | 1.90 | 0.912 |

| The uncertain work prospects | 20 | 1.80 | 1.056 |

| Lack of appreciation from the superior | 20 | 1.80 | 1.056 |

| Poor work atmosphere | 20 | 1.75 | 0.967 |

| Personal illnesses | 20 | 1.75 | 1.070 |

| Valid N (listwise) | 20 | ||

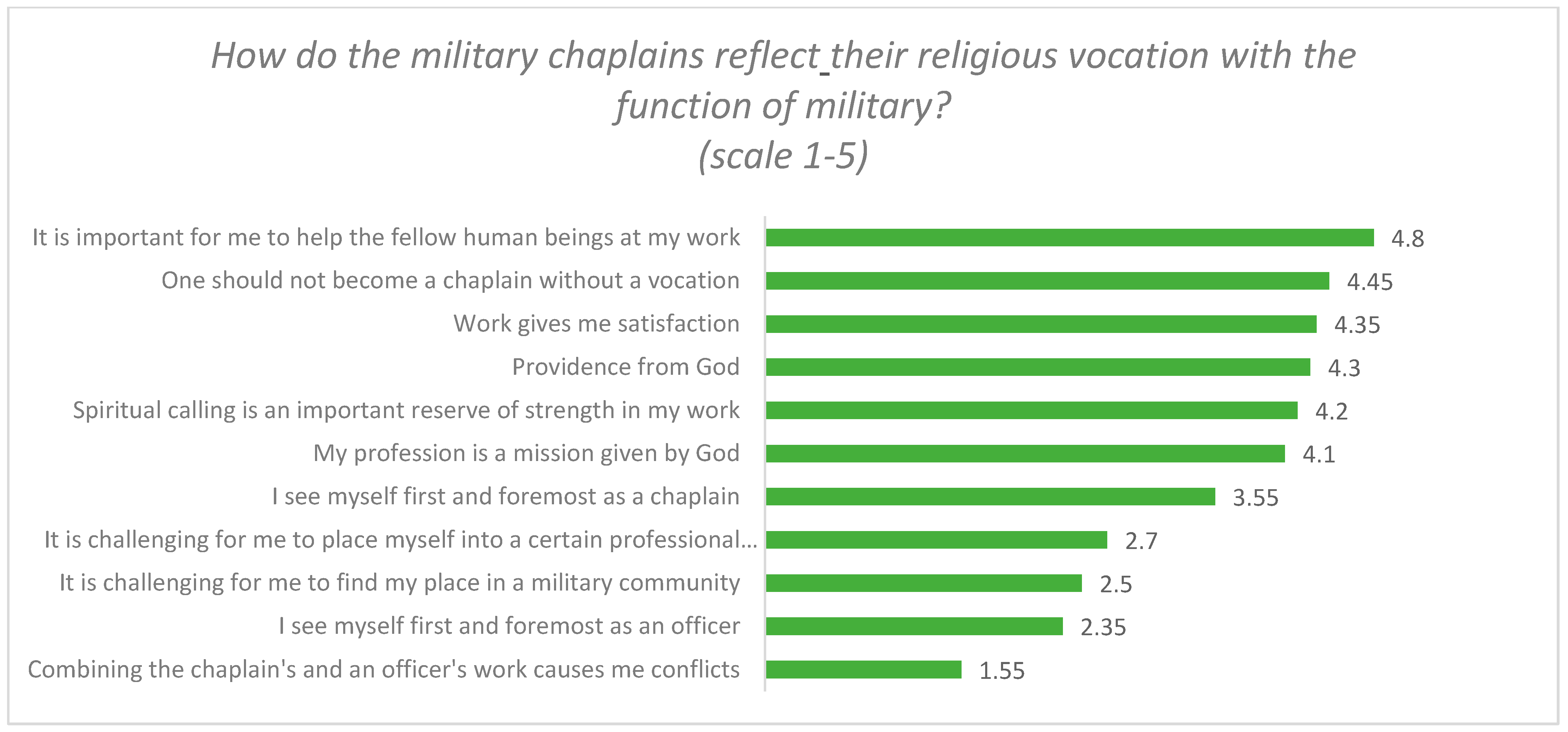

| Descriptive Statistics | |||

| N | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

| It is important for me to help the fellow human beings at my work | 20 | 4.80 | 0.410 |

| One should not become a chaplain without a vocation | 20 | 4.45 | 0.826 |

| Work gives me satisfaction | 20 | 4.35 | 0.587 |

| Providence from God | 20 | 4.30 | 0.733 |

| Spiritual calling is an important reserve of strength in my work | 20 | 4.20 | 0.951 |

| My profession is a mission given by God | 20 | 4.10 | 0.912 |

| I see myself first and foremost as a chaplain | 20 | 3.55 | 1.191 |

| It is challenging for me to place myself into a certain professional category | 20 | 2.70 | 1.380 |

| It is challenging for me to find my place in a military community | 20 | 2.50 | 1.147 |

| I see myself first and foremost as an officer | 20 | 2.35 | 0.813 |

| Combining the chaplain’s and an officer’s work causes me internal conflicts | 20 | 1.55 | 0.605 |

| Valid N (listwise) | 20 | ||

References

- Besterman-Dahan, Karen, Scott D. Barnett, Edward J. Hickling, Christine A. Elnitsky, Jason D. Lind, John Skvoretz, and Nicole Antinori. 2012. Bearing the Burden: Deployment Stress Among Army National Guard Chaplains. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy 18: 151–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenkner, David P., Peter D. Yeomans, Chris J. Antal, and J. Cobb Scott. 2020. A Pilot Study of a Moral Injury Group Intervention Co-Facilitated by a Chaplain and Psychologist. Journal of Traumatic Stress. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesur, Resul, Travis Freidman, and Joseph J. Sabia. 2020. War, Traumatic Health Shocks, and Religiosity. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 179: 475–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, Mark, Chris Shiels, Mari Lloyd Williams, and Michael Wright. 2004. A Prospective Study of the Roles, Responsibilities and Stresses of Chaplains Working within a Hospice. Palliative Medicine 18: 638–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, Michael S. 2011. Organizational Change and Employee Stress. Management Science 57: 240–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzioni, Amitai. 1973. Nykyajan Organisaatiot. Helsinki: Tammi. [Google Scholar]

- Finnish Defence Committee’s Memorandum. 2017. PuVM 4/2017. Puolustusvaliokunnan Mietintö PuVM 4/2017. Available online: https://www.eduskunta.fi/FI/vaski/Mietinto/Documents/PuVM_4+2017.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- Goffman, Erving. 1957. The Characteristics of Total Institutions. Symposium Presentation on Preventive and Social Psychiatry 15.-17.4.1957. Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Washington DC. Available online: https://is.muni.cz/el/1423/podzim2009/SOC139/um/soc139_16_Goffman.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- Grimell, Jan. 2020a. An Interview Study of Experiences from Pastors Providing Military Spiritual Care Within the Swedish Armed Forces. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimell, Jan. 2020b. Military Chaplaincy in Sweden: A Contemporary Perspective. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilverda, Femke, Rick van Gils, and de Graaff Miriam Carla. 2018. Confronting Co-Workers: Role Models, Attitudes, Expectations, and Perceived Behavioral Control as Predictors of Employee Voice in the Military. Frontiers in psychology 9: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, Dawn, and Terry L. Amburgey. 1991. Organizational Inertia and Momentum: A Dynamic Model of Strategic Change. The Academy of Management Journal 34: 591–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkon Ammattien Yhteinen Ydinosaamiskuvaus. 2010. Available online: https://evl.fi/documents/1327140/43561565/Kirkon_ammattien_yhteinen_ydinosaamiskuvaus_2020_pdf.pdf/803a8b5f-d968-c60c-a44c-c2a81d57eea1?t=1596644147400 (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- Kirkon hengellisen työn ammattien ydinosaaminen. 2010. Kirkon hengellisen työn ammattien ydinosaaminen. Helsinki: Kirkkohallitus. [Google Scholar]

- Lahti, Emilia E. 2019. Embodied fortitude: An introduction to the Finnish construct of sisu. The International Journal of Wellbeing 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinonen, Minna, Nikkanen Risto, and Otonkorpi-Lehtoranta Sami. 2018. Organizational Change and Employee Concerns in the Finnish Defence Forces. Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liuski, Tiia. 2019. The Interviews with the Finnish Military Chaplains, In author’s possession.

- Liuski, Tiia, and Ubani Martin. 2020. How Is Military Chaplaincy in Europe Portrayed in European Scientific Journal Articles Between 2000 and 2019? A Multidisciplinary Review 11: 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, Jessica Kelley, Laurel Hourani, Marian E. Lane, and Stephen Tueller. 2016. Help-Seeking Behaviors Among Active-Duty Military Personnel: Utilization of Chaplains and Other Mental Health Service Providers. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy 22: 102–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemelä, Kati. 2014. Pappien ja kanttorien suhde työhön, työhyvinvointi ja suhtautuminen ajankohtaisiin kysymyksiin Kirkon akateemisten jäsenkyselyssä 2014. Kirkon Tutkimuskeskuksen Verkkojulkaisuja 38. Available online: http://sakasti.evl.fi/julkaisut.nsf/25A061BE3EE694BCC2257E2E0012D562/$FILE/Julkaisu%2038.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- Nieuwsma, Jason A., George L. Jackson, Mark B. Dekraai, Denise J. Bulling, William C. Cantrell, Jeffrey E. Rhodes, Mark J. Bates, Keith Ethridge, Marian E. Lane, Wendy N. Tenhula, and et al. 2014. Collaborating Across the Departments of Veterans Affairs and Defense to Integrate Mental Health and Chaplaincy Services. Journal of General Internal Medicine 29 Suppl. 4: 885–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otonkorpi-Lehtoranta, Katri, Minna Leinonen, Risto Nikkanen, and Tuula Heiskanen. 2015. Intersections of Gender, Age and Occupational Group in the Finnish Defence Forces. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal 34: 593–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Personnel Strategy of the Finnish Defence Forces. 2015. [PVOHJEK—PE HK1027/19.12.2014]. Pääesikunnan henkilöstöosasto: Juvenes Print Oy. Available online: http://puolustusvoimat.fi/documents/1948673/2267766/PEVIESTOS-HESTRA_Julkaisu.pdf/8d909e64-5538-4366-b7fc-ba6f2c80c9bf (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- Pheysey, Diana C. 1993. Organizational Cultures: Types and Transformations. Available online: http://web.b.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.uef.fi:2048/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=4&sid=145fe754-a7f5-4ba6-9478-94dd83df4e77%40sessionmgr101 (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- Rauhanturvaajan Käsikirja. 2020. Porin prikaatin Kriisinhallintakeskuksen julkaisuja. PunaMusta Oy. Peacekeeper’s Handbook 2020. Publications of the Finnish Crisis Management Center Finland. Available online: https://puolustusvoimat.fi/documents/1948673/2015509/Rauhanturvaajan_opas_2019_web.pdf/6734afd9-5be9-434a-84be-2faae5fa8db2 (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- Rennick, Joanne Benham. 2011. Canadian Military Chaplains: Bridging the Gap Between Alienation and Operational Effectiveness in a Pluralistic and Multicultural Context. Religion, State and Society 39: 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research warrant AM22534. 2016. A personal research warrant for the dissertation study. Provider: The Finnish Defence Forces. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Daniel L., and Joann Kovacich. 2020. Male Chaplains and Female Soldiers: Are There Gender and Denominational Differences in Military Pastoral Care? The Journal of Pastoral Care & Counselling 74: 133–40. [Google Scholar]

- Schuhmann, C. M., J. Wojtkowiak, R. van Lierop, and F. Pitstra. 2020. Humanist Chaplaincy According to Northwestern European Humanist Chaplains: Towards a Framework for Understanding Chaplaincy in Secular Societies. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seddon, Rachel L., Edgar Jones, and Neil Greenberg. 2011. The Role of Chaplains in Maintaining the Psychological Health of Military Personnel: An Historical and Contemporary Perspective. Military Medicine 176: 1357–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Smaliukiene, Rasa, and Svajone Bekesiene. 2020. Towards Sustainable Human Resources: How Generational Differences Impact Subjective Wellbeing in the Military? Sustainability 12: 10016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldier´s Mind and Soldier´s Body. 2020. Available online: https://puolustusvoimat.fi/en/soldier-s-mind-and-soldier-s-body (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- Tervo-Niemelä, Kati. 2016. Clergy Work Orientation Profiles and Wellbeing at Work: A Study of the Lutheran Clergy in Finland. Review of Religious Research 58: 365–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | (Liuski 2019). |

| 2 | (Liuski 2019). |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | |

| 8 | |

| 9 | |

| 10 | |

| 11 | |

| 12 | |

| 13 | |

| 14 | |

| 15 | Training 2020 Programme. |

| 16 | Private e-mail-conversation with a MC; (Soldier’s Mind and Soldier´s Body 2020). |

| 17 | Private e-mail conversation with a MC. |

| 18 | Military Chaplaincy, Military Chaplains = the whole occupational group, that consists of military chaplains and senior chaplains. |

| 19 | |

| 20 | |

| 21 | |

| 22 | |

| 23 | |

| 24 | Puolustusvoimien henkilöstöstrategia 2015. |

| 25 | |

| 26 | |

| 27 | (M = 5.00, SD = 0.00). |

| 28 | (Liuski 2019). |

| 29 | (Liuski 2019). |

| 30 | |

| 31 | (Liuski 2019). |

| 32 | It should be noted, that there has been changes in the professional group of MCs after the interviews and they have become younger. This might have an effect on how the results would appear today. |

| 33 | (Liuski 2019). |

| 34 | (M = 5.00, SD = 0.00). |

| 35 | (M = 4.20, SD = 1.06). |

| 36 | (M = 4.45, SD = 1.06). |

| 37 | (M = 4.50, SD = 0.51). |

| 38 | (M = 4.25, SD = 0.55). |

| 39 | (M = 3.89, SD = 0.94). |

| 40 | (M = 3.92, SD = 0.64). |

| 41 | (SD = 0.71). |

| 42 | (M = 4.53, SD = 0.44). |

| 43 | (SD = 0.84). |

| 44 | (M = 2.70, SD = 0.87). |

| 45 | (M1 = 3.86, SD = 1.28; M2 = 3.89, SD = 0.47; M3 = 3.97, SD = 0.29). |

| 46 | (M1 = 3.30, 1.25; M2 = 3.17, SD = 1.21; M3 = 3.53, SD = 0.52). |

| 47 | (Liuski 2019). |

| 48 | (Liuski 2019). |

| 49 | (M = 5.00, SD = 0.00). |

| 50 | (M = 4.70, SD = 0.47). |

| 51 | (M = 4.70, SD = 0.47). |

| 52 | (M = 4.65, SD = 0.59). |

| 53 | (M = 4.60, SD = 0.60). |

| 54 | (M = 4.50, SD = 0.51). |

| 55 | (M = 3.20, SD = 1.06). |

| 56 | (M = 3.30, SD = 0.80). |

| 57 | (Liuski 2019). |

| 58 | (Liuski 2019). |

| 59 | (Liuski 2019). |

| 60 | (χ2(2) = 17.500, p < 0.05). |

| 61 | (M = 4.08, SD = 0.64). |

| 62 | (M = 3.29, SD = 0.76). |

| 63 | (M1 = 4.00, SD = 0.63, M2 = 3.62, SD = 3.33, M3 = 3.65, SD = 0.75). |

| 64 | (M1 = 3.00, SD = 1.06, M2 = 2.83, SD = 0.92, M3 = 3.20 SD = 1.06). |

| 65 | (M1 = 3.67, SD = 0.82, M2 = 4.38, SD = 0.52, M3 = 3.17, SD = 0.75). |

| 66 | (χ2(2) = 7.575, p < 0.05). |

| 67 | (M1 = 4.83, SD = 0.41, M2 = 4.75, SD = 0.46, M3 = 4.17, SD = 0.75). |

| 68 | (M1 = 3.67, SD = 0.52, M2 = 4.25, SD = 0.71, M3 = 4.17, SD = 0.75). |

| 69 | (M1 = 3.33, SD =.52, M2 = 4.13, SD = 0.99, M3 = 3.50, SD = 0.84). |

| 70 | (M1 =3.00, SD = 0.89, M2 = 3.63, SD = 0.92, M3 = 3.17, SD = 0.41). |

| 71 | (M1 = 3.20, SD = 0.45, M2 = 3.63, SD = 0.52, M3 = 4.00, SD = 0.00). |

| 72 | (χ2(2) = 7.830, p < 0.05). |

| 73 | (M1 = 4.80, SD = 0.45, M2 = 4.25, SD = 0.89, M3 = 4.14, SD = 0.38). |

| 74 | (M1 = 3.20, SD = 0.84, M2 = 3.88, SD = 0.84, M3 = 3.71, SD = 0.49). |

| 75 | (M1 = 3.00, SD = 1.58, M2 = 3.50, SD = 0.93, M3 = 3, SD = 0.82). |

| 76 | (M1 = 3.20, SD = 0.84, M2 = 4.13, SD = 0.64, M3 = 3.86, SD = 0.90). |

| 77 | (M1 = 3.00, SD = 0.00, M2 = 3.63, SD = 1.06, M3 = 3.14, SD = 0.70). |

| 78 | (M = 4.25, SD = 0.55). |

| 79 | (M = 3.90, SD = 1.07). |

| 80 | (M = 2.05, SD = 0.99). |

| 81 | (M1 = 3.69, SD = 0.95, M2 = 3.00, SD = 1.16). |

| 82 | (M1 = 3.17, SD = 0.75, M2 = 3.25, SD = 1.17, M3 = 4.00, SD = 1.10). |

| 83 | (U = 14.000, p < 0.01). |

| 84 | (M1 = 2.46, SD = 0.97, M2 = 1.29, SD = 0.49). |

| 85 | (Liuski 2019). |

| 86 | (Liuski 2019). |

| 87 | (Liuski 2019). |

| 88 | (Liuski 2019). |

| 89 | (Liuski 2019). |

| 90 | (M = 3.70, SD = 0.80). |

| 91 | (M = 3.70, SD = 0.80). |

| 92 | (M = 3.45, SD = 1.05). |

| 93 | (M = 1.75, SD = 0.97). |

| 94 | (M = 1.75, SD = 0.97). |

| 95 | (M = 1.80, SD = 1.06). |

| 96 | (M =1.80, SD = 1.06). |

| 97 | (M = 1.90, SD = 0.91). |

| 98 | (M = 1.95, SD = 1.05). |

| 99 | (M = 2.00, SD = 0.97). |

| 100 | (M = 2.05, SD = 1.32). |

| 101 | (U = 75.500, p < 0.05). |

| 102 | (U = 71.000, p < 0.05). |

| 103 | (M = 1,77 SD = 0.60). |

| 104 | (M = 2.86, SD = 1.07). |

| 105 | (M1 = 3.00, SD = 1.00, M2 = 3.71, SD = 0.95). |

| 106 | (M1 = 2.38, SD = 1.12, M2 = 3.29, SD = 0.95). |

| 107 | (M1 = 2.00, SD = 1.27, M2 = 2.25, SD = 1.28, M3 = 2.50, SD = 1.38). |

| 108 | life (χ2(2) = 6.393, p < 0.05). |

| 109 | (M1 = 1.60, SD = 0.55). |

| 110 | (M2 = 3.00, SD = 1.20). |

| 111 | (M3 = 3.14, SD = 0.90). |

| 112 | (M1 = 1.60, SD = 0.89, M2 = 3.25, SD = 1.04, M3 = 2.43, SD = 0.98). |

| 113 | (χ2(2) = 6.579, p < 0.05). |

| 114 | (M1 = 3.80, SD = 0.84, M2 = 3.38, SD = 0.92, M3 = 2.86 SD = 1.07). |

| 115 | (M1 = 2.60, SD = 1.14, M2 = 4.00, SD = 0.54, M3 = 3.43, SD = 1.13). |

| 116 | “In the Nordic country of Finland, a cultural construct known as sisu has been used for centuries to describe the enigmatic power that enables individuals to push through unbearable challenges.” (Lahti 2019). |

| 117 | (M = 3.55, SD = 1.19). |

| 118 | (M = 2.35, SD = 0.81). |

| 119 | (M = 4.00, SD = 1.16). |

| 120 | (M = 2.29, SD = 0.76). |

| 121 | (M = 3.31, SD = 1.18; M = 2.38, SD = 0.87). |

| 122 | (M = 1.71, SD = 0.76). |

| 123 | (M = 1.46, SD = 0.52). |

| 124 | (M = 2.50, SD = 1.15). |

| 125 | (M = 2.70; SD = 1.38). |

| 126 | (M = 2.14, SD = 0.90). |

| 127 | (M = 2.69, SD = 1.25). |

| 128 | (r = 0.488, p < 0.05). |

| 129 | (M = 2.00, SD = 0.71). |

| 130 | (M = 2.13, SD = 0.99). |

| 131 | (M = 2.86, SD = 0.38). |

| 132 | (r = 0.507, p < 0.05). |

| 133 | (M = 3.33, SD = 1.03). |

| 134 | (M = 2.38, SD = 1.19). |

| 135 | (M = 1.83, SD = 0.753). |

| 136 | (Liuski 2019). |

| 137 | (SD = 0.70). |

| 138 | (SD = 0.79). |

| 139 | (M = 3.85, SD = 0.81). |

| 140 | (M = 3.15, SD = 1.18). |

| 141 | (M = 2.25, SD = 0.97). |

| 142 | (M = 1.80, SD = 0.83). |

| 143 | (The liberty to religion is in danger to weaken the military: M = 2.90, SD = 1.21). |

| 144 | (M = 2.55, SD = 1.00). |

| 145 | (Liuski 2019). |

| 146 | (Liuski 2019). |

| 147 | (M = 3.42, SD = 0.56). |

| 148 | (M = 4.20, SD = 0.70). |

| 149 | (M = 4.20, SD = 0.89). |

| 150 | (M = 2.35, SD = 0.99). |

| 151 | (M = 2.25, SD = 1.11). |

| 152 | (M1 = 4.00, SD = 1.00, M2 = 4.57, SD = 0.54). |

| 153 | (M1 = 3.69, SD = 0.86, M2 = 4.43, SD = 0.54). |

| 154 | (M1 = 2.85, SD = 0.90, M2 = 3.71, SD = 0.95). |

| 155 | (M1 = 3.00, SD = 1.23, M2 = 3.57, SD = 0.54). |

| 156 | (M1 = 2.85, SD = 0.80, M2 = 3.43, SD = 0.78). |

| 157 | (M1 = 3.62, SD = 1.04, M2 = 4.43, SD = 0.54). |

| 158 | (M1 = 4.17, SD = 0.75, M2 = 3.50, SD = 0.93, M3 = 3.17, SD = 1.47). |

| 159 | (M1 = 3.67, SD = 1.03, M2 = 3.38, SD = 0.52, M3 = 2.33, SD = 1.03). |

| 160 | (M1 = 3.67, SD = 0.52, M2 = 3.00, SD = 0.54, M3 = 3.67, SD = 0.52). |

| 161 | (M1 = 3.60, SD = 0.89, M2 = 2.50, SD = 0.54, M3 = 2.29, SD = 0.95). |

| 162 | (M1 = 3.00, SD = 1.00, M2 = 3.88, SD = 0.64, M3 = 3.71, SD = 0.49). |

| 163 | (M1 = 4.20, SD = 0.84, M2 = 3.50, SD = 1.07, M3 = 4.14, SD = 0.90). |

| 164 | |

| 165 | |

| 166 | |

| 167 | |

| 168 | |

| 169 |

| WorkXPgrouped | ||

|---|---|---|

| N | % | |

| 1.00 | 5 | 25.0% |

| 2.00 | 8 | 40.0% |

| 3.00 | 7 | 35.0% |

| BirthYrgrouped | ||

|---|---|---|

| N | % | |

| 1.00 | 6 | 30.0% |

| 2.00 | 8 | 40.0% |

| 3.00 | 6 | 30.0% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liuski, T.; Ubani, M. The Lutheran Military Chaplaincy in the Finnish Defence Forces’ Organisation Today. A Multi-Method Approach. Religions 2021, 12, 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12040243

Liuski T, Ubani M. The Lutheran Military Chaplaincy in the Finnish Defence Forces’ Organisation Today. A Multi-Method Approach. Religions. 2021; 12(4):243. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12040243

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiuski, Tiia, and Martin Ubani. 2021. "The Lutheran Military Chaplaincy in the Finnish Defence Forces’ Organisation Today. A Multi-Method Approach" Religions 12, no. 4: 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12040243

APA StyleLiuski, T., & Ubani, M. (2021). The Lutheran Military Chaplaincy in the Finnish Defence Forces’ Organisation Today. A Multi-Method Approach. Religions, 12(4), 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12040243