1. Introduction

Karol Wojtyła is certainly one of the most recognisable Polish and Central European thinkers. Although worldwide his pontifical writings are primarily known, one cannot forget the philosophical and theological works he had published before he became the pope. His output was extensive and was devoted to various issues in the field of theology and philosophy. The earliest works, written during the period of education in theological seminary, were related to studies on the theology of spirituality. In the early 1950s, he turned to philosophy. Looking for inspiration for the theology of morality, he came across Max Scheler’s phenomenology. He combined the phenomenological approach with traditional Thomistic metaphysics, which resulted in an original synthesis, the fruit of which was Wojtyła’s personalism. In his both philosophical and theological and pastoral considerations, the question of European identity also appears. Furthermore, although he developed this idea during his pontificate, this subject was present in his work before he became pope. The language was certainly a barrier here as he published mainly in Polish, although some of his works, e.g.,

Osoba i czyn (the English title

The Acting Person) (

Wojtyła [1969] 1979) or

Miłość i odpowiedzialność (

Love and Responsibility) (

Wojtyła [1960] 1981), were translated into English and entered the world of philosophical and theological discourse. The considerations of non-Polish authors focus mainly on issues in the fields of philosophical anthropology, ethics or moral theology (

Schmitz 2001). The comments also relate to the papal encyclicals (

MacIntyre 2009). However, we can also find comprehensive, synthetic approaches to Wojtyła’s philosophical and theological concepts, e.g., in the case of Rocco Buitiglione’s work (

Buitiglione 1997).

The aim of this article is to present the spiritual heritage of Europe from the universalist perspective that emerges in the works of Karol Wojtyła, i.e., John Paul II. Although these themes appear in papal documents and speeches, such as the encyclical

Slavorum Apostoli, publications important to this topic, such as the article

Gdzie znajdują się granice Europy? [

Where Are the Borders of Europe?], have not yet been published in English, due to which this issue is poorly recognisable outside of Poland, where some interesting works on this subject have been written. In their work, Sławomir Sowiński and Radosław Zendrowski paid attention to John Paul II’s perception of the process of shaping European identity and the role of the Catholic Church in this process (

Swoiński and Radosław 2003). The role of Christianity and the Catholic Church in the process of European integration in the light of papal teaching has been thoroughly analysed by

Życiński (

1998a);

Muszyński (

2002) and

Ewertowski (

2003). Grzegorz Przebinda, in turn, pointed to Wojtyła’s perception of Ukraine and Russia as European societies and cultures (

Przebinda 2001), and

Górzna (

2013) to John Paul II’s positive attitude to the presence of Jews and Muslims in Europe. This article is not only a presentation of Karol Wojtyła’s (John Paul II) views on the identity of Europe and its spiritual heritage, but an attempt to show the philosophical and theological inspirations on the basis of which Wojtyła’s vision of Europe developed.

2. Methods and Materials

In my article I place the issue of European identity and the spiritual heritage of Europe in a broader context as a manifestation of Wojtyła’s personalistic and universalistic attitude. In fact, I refer to two interpretations that constitute the basic research method in my work. We are talking here about personalistic hermeneutics and civilisational interpretation. We can look for the sources of Wojtyła’s personalistic universalism in his intellectual fascination with the theology of spirituality, in which we find the genesis of personalism; Europe is understood in Wojtyła’s philosophical and theological thought as a universalist project that assumes a personalistic perspective, i.e., universality is attributed to a person as a unique and distinct being, entering into relations with other people and building a community based on the principle of attaining the common good and common values. In relation to Europe, the carrier of universalism is also Christianity with its inclusive character and universalist axiology. As Czesław Bartnik, one of the leading Polish personalists and also an expert on Wojtyła’s thoughts, notes: “Karol Wojtyła’s genius went beyond simple anthropology towards personalistic systematisation, mainly of a mystical type, and ethical personality was a model” (

Bartnik 1995, p. 153). For the so-called Lublin school, whose co-creator was Wojtyła, personalistic hermeneutics is not only an analysis of the text, but above all, a way to show the uniqueness of the person as a subject of all other categories, in his dynamics and relationality towards other people, including God himself (

Bartnik 2006, p. 20;

Dola 2017, pp. 827–28). For the personalistic system, the category of “person” is a hermeneutic key. Cognition focuses around him. The “person” is a cognitive model and method, that is, the construction of knowledge about him and his relation with the world, because he is treated as “the core of reality” and the “most essential being”. The person is thus a kind of “methodological paradigm” through whose perspective the whole reality is seen. The person gives the proper sense to the world (

Barth 2008, p. 361). In this sense, my research on Wojtyła’s thought is only meta-hermeneutic. I strive for a proper understanding of the essence of Wojtyła’s views on Europe, its identity and spiritual heritage. I do not create any original concept, but I recreate a vision that Wojtyła outlined himself. The key to understanding his perception of Europe is the category of the person. Referring to personalistic hermeneutics allows us to understand not only Wojtyła’s anthropological and ethical position, but also shows in the proper light his reflections on European identity and unity, fitting in the universalist vision of Europe not only as a common space for Europeans, but also as a space for interpersonal relations based on respect for the dignity of every human being, which is a fundamental social value.

The other method I refer to is civilisational interpretation. Thanks to this interpretation, Wojtyła’s concept is presented in a broader context, against the background of the discussion between universalist and pluralist visions of civilisation (

Chodubski 2008, p. 165). European issues, relating in particular to European identity or European heritage, are part of this, in fact historiosophical, discourse. Wojtyła’s position can be described as universalistic, and in its deepest form this universalism is personalistic. Wojtyła’s universalism was first noted by Janusz Kuczyński, a Marxist philosopher, who already in 1979 in the pages of

Dialectics and Humanism presented the possibility of beginning a dialogue between Marxist philosophy and the social doctrine of the Catholic Church, which would be facilitated by universalist inclinations that he saw in the Pope from Poland (

Kuczyński 1979). However, this author did not associate universalism with personalism, which was noticed much later by other interpreters of Karol Wojtyla’s (John Paul II) philosophical and theological thought, and he did not go beyond the interdoctrinal dialogue, which should be treated as only one aspect of Wojtyła’s universalism, not its essence (

Modrzejewski 2002;

Górski 2006).

Both approaches, i.e., personalistic and civilisational, are complementary here. Personalistic hermeneutics allows us to capture the proper sense of the concept of European identity and European spiritual heritage in Wojtyła’s philosophical and theological thought, in which the person has a superior place as the most important value. On the other hand, the civilisational interpretation makes it possible to see in this concept a socio-political construct in which universalist threads intertwine, the core of which is Christian axiology and anthropology with its supremacy of the person in the axiological system, as well as in the ontological sense, along with particular identities that constitute the cultural and spiritual richness of Europe.

In this article I refer both to Wojtyła’s pre-pontifical achievements, including works devoted to mysticism, anthropological ones and those in the field of philosophy of culture, as well as John Paul II’s documents, memoirs and papal speeches, the intellectual foundation of which was the philosophical and theological thought formulated before his papacy. I do not consider pre-pontifical and pontifical output separately. The Pope’s writings and speeches are strongly rooted in his earlier philosophical and theological works, to which he indirectly referred. Wojtyła’s reflections on mysticism are particularly interesting in the context of Europe’s spiritual heritage.

3. Europe in the Context of Dispute between Universalism and Pluralism

In the theory of civilisation, which is the most general definition of interdisciplinary studies concerning intercultural relations on a global or at least regional scale, we deal with two opposing views, i.e., universalism and pluralism. It seems necessary to supplement this dichotomous division with intermediate positions such as: (1a) extreme pluralism; (1b) moderate pluralism; (2a) moderate universalism; and (2b) extreme universalism (

Modrzejewski 2009).

Extreme pluralism recognises the existence of only so-called particular civilisations and thus particular historiosophic and civilisation optics. The very idea of universal civilisation is perceived either as an expression of Western expansionism or as postmodern illusoriness, which in fact leads to the standardisation of culture (

Koneczny [1935] 1997;

Kołakowski 1984;

Huntington [1994] 2011;

Barber 1995;

Tibi 1995). Moderate pluralism assumes the existence of particular civilisations, as well as particular historiosophic optics, but at the same time it takes into account the possibility of the emergence of a universal civilisation in the future, which is a form of a globalised particular civilisation. Western civilisation is most often mentioned here (

Maritain 1931;

Toynbee 1948;

Piskozub 2003). Another variant of moderate particularism treats the universal status of a specific civilisation, e.g., Christian, only in a symbolic sense (

Dawson [1948] 2013;

Ratzinger 2007).

Moderate universalism recognises both the pluralism of civilisations and particular cultures, as well as historical, cultural and civilisational universality (among others,

Coudenhove-Kalergi 1953). This position is also typical of Polish universalist thinkers, including Karol Wojtyła i.e., John Paul II (

Modrzejewski 2009). On the other hand, extreme universalism, which affirms the existence of only one civilisation, may take either an exclusive form as the domain of one cultural circle which is usually, but not always, the Western world or Christianity, as in the case of Gioacchimo Pecci, better known by the pontifical name of Leo XIII, who shortly before being elected Pope published pastoral letters as the bishop of Perugia, and in them he included his concept of civilisation as

ex definitione Christian (

Pecci 1991), or a syncretic form, when local cultures “melt” into a historical and civilisational unity (e.g., the Baháʼí Faith, the New Age movement). In the latter sense, universalism is a syncretic religion, social movement, and lifestyle, rather than a philosophical current or a theoretical position. Syncretism also has its linguistic and philosophical dimensions. It leads to a search for a primeval language, a kind of proto-language that would contain all the contemporary and extinct languages (cf.

Eco 1997). In Christian philosophy and phenomenology, French Catholic intellectual Teilhardom de Chardin referred to universalist syncretism when in his holistic vision he presumed the universal striving for union with God as the only one (

Teilhard de Chardin 1964). Although this universalism has primarily an eschatological dimension, it also takes place in the temporal world, taking the form of

evolutionary monism, based on the

substantial unity of the world (

Plašienková and Kulisz 2004, p. 37). A representative of extreme universalism, although not in a syncretic form, is another French intellectual, Alain Badiou, who, referring to the experience of St. Paul of Tarsus, speaks of establishing a universal truth taken out of its particular context and referring to all mankind, which brings with it social and political consequences (

Badiou 2003). Shortly speaking, extreme universalism treats universality as an immanent attribute of a specific civilisation or disregards civilisation specificity in favour of becoming

tout court universalism, which of course does not mean getting rid of being rooted in a specific intellectual culture.

In the context of the debate between pluralism and universalism, Europe or more broadly the Western world is generally perceived as either in fact the only universal civilisation, or as a civilisation with universal potential and ambitions. The universality of Europe is assessed in various ways. It is either a manifestation of Western expansionism, now primarily in the cultural dimension (e.g., Huntington, Tibi, Barber), or is a specific attribute of European culture that results from universal values, integrally connected with Europe and its Christian heritage (among others Dawson, Maritain, Coudenhove-Kalergi, Pecci, Wojtyła). The space of European civilisation is usually reduced to the West. Its boundaries in Europe overlap with those of Western Christianity at best. This is clearly visible in a conflicting concept of Samuel P. Huntington, who divided Europe into Western (European) civilisation and Orthodox, with its centre now located in Russia, and earlier in Byzantium. Even among Catholic intellectuals, European

limes overlaps with the borders of the influence of Western Christianity. An outstanding Pomeranian intellectual,

Pasierb (

2004), presented it vividly, claiming that a Gothic cathedral is a symbol of European civilisation. Thinking in terms of dividing the Old Continent into two parts is also characteristic of some anti-Westernism currents of Russian geopolitical thought (

Potulski 2010). In this way, Orthodoxy is deprived of its European character. This approach is in opposition to the concept presented in Wojtyła’s social thought, philosophy and theology. His universalist and personalistic vision of Europe, largely inspired by the studies of mysticism, may therefore constitute an alternative view in the intellectual discourse devoted to universalism and European civilisation. Not only is the concept of European values universal, but also the idea of Europe, which is an axiological unity composed of various cultural elements, including two traditions of Christianity, i.e., Latin and Byzantine.

4. Inspiration with the Theology of Spirituality

Wojtyła’s path to personalism and related universalism, so-called personalistic universalism, which was also the essence of Wojtyła’s vision of Europe, was led through research on the mysticism of St. John of the Cross and the phenomenological ethics of German philosopher Max Scheler. Metaphysical education in the Thomistic spirit was also significant for his intellectual formation. Wojtyła identified with Thomism and Thomistic personalism (

Wojtyła 1961), although there is a dispute among interpreters whether he was a phenomenologist or rather a Thomist. However, I am not going to resolve this contention here as this is not the aim of this article. Wojtyła referred to both positions. Nevertheless, it was the theology of spirituality that was the first research experience of the future Pope. Studies on the writings of the Spanish mystic, which resulted in a doctoral dissertation

1, later contributed to drawing attention to phenomenology, which Wojtyła treated as a method of philosophising, especially useful in the field of moral considerations

2. Already at that time he was interested in concrete and direct experience, giving him an opportunity to explore the essence of things. In the case of the analysis of John of the Cross’s work, the point was to experience the supernatural life of the mystic. This experience became the starting point for research into mysticism, but also, as Wojtyła himself noted in one of his articles, humanism as such (

Wojtyła 1951, p. 7).

The interest in mystical works was related to the analysis of the phenomenon of experience. That is why this period in Wojtyła’s intellectual formation is treated by his interpreters as “unconscious phenomenology” (

Kupczak 1999, p. 45;

Półtawski 2011, p. 189) or rather as “undefined phenomenology” or as “proto-phenomenology” (

Modrzejewski and Gálik 2016, p. 58)

3. Reaching for the work of the mystic, Wojtyła was looking for answers to two key and related questions: “

Who is man?” and “

Who can and should man become?”. The first question is anthropological in nature and touches upon the ontological issue—man as a specific being. The other is an ethical and existential question (

Pokrywka 2000, p. 23). For Wojtyła, mystical thought became a specific method of reaching statements about the essence of man and humanity. In the mysticism of St. John of the Cross, one can find such a type of anthropology that makes it easier to understand and explain the human phenomenon in what is essentially, in nature that is, human, i.e., an experience on which Wojtyła’s anthropology and ethics will focus later in his life (

Kupczak 1999, p. 22). A permanent trace of studies on the theology of spirituality of St. John of the Cross is a strong conviction in Wojtyła that spirituality is the essence of human existence. The experience of God as the source of our spirituality is also part of this spiritual dimension. Asking existential questions, man in fact seeks God in himself, with whom he establishes a relationship and dialogue. Thus, the human being in his deepest, spiritual dimension appears as both relational and dialogical. Union with God does not mean some form of losing oneself, a kind of objectification of man by God, but it enriches us and prompts us to act creatively, but always in accordance with our free will. By means of the process of internal purification thanks to love, man becomes united with God through the fact that God, his supernatural being, gradually gives himself to man. Man, experiencing a kind of divine enlightenment, participates in the Divine Being, in the life of God (

Machniak 2008, p. 390). Following St. John of the Cross, Wojtyła emphasised the ontological difference between God and man. The Spanish mystic wrote that no creature possesses an essential likeness with God (John of the Cross: Ascent of Mount Carmel, available online:

https://www.ecatholic2000.com/stjohn/ascent29.shtml (accessed on 10 January 2021)). Interpreting Wojtyła’s thought, Buttiglione notes that the phenomenology of mystical experience leads to the irreducible centre of the person and shows the necessity of the person’s self-transcendence towards the truth which is God himself (

Buitiglione 1997, p. 86). Through the free and conscious choice of participation in God’s life, not only our inner world is enriched, but also our relationship with the world, our presence in the world (

Pokrywka 2000, p. 26). Faith is an effective tool for uniting man with God. It allows man to go beyond his limitations, takes man beyond the natural order towards supernatural reality. Union with God through faith is achieved thanks to the grace of love, which makes man similar to God, combines the will of man with God’s will, thanks to which man acts in accordance with God’s will. Love is the force that transforms man. However, in this transformation love always acts jointly with faith (

Machniak 2008, pp. 392–93).

Man’s meeting with God is, in fact, a personal meeting of two people. Thanks to the gift that man receives from God, man lives in the personal entrails of God, and God inside man. However, this does not blur the distinction between God and man. Each of them remains a person, and thus retains his individual substantiality (

Buitiglione 1997, p. 84). In the anthropological interpretation and in social philosophy this specific relationship is extended to other people. The other person does not, of course, play a role analogous to God, but by interacting with him, we remain, as in the case of the God–man relationship, a separate being, a separate person. By an act of our will, together with other people we are predestined to build a community of people. Buttiglione, quoted above, believes that the confrontation with the thought of St. John of the Cross strengthens Wojtyła’s conviction about the personalistic nature of Christianity. Faith is not born out of some all-encompassing theory, but of a person’s inner experience. That is why Christian faith accompanies the person’s freedom and protects him from any objectification and instrumentalization (

Buitiglione 1997, p. 92).

In the studies on mysticism, one can find not only the sources of Wojtyła’s phenomenology, but also personalism, and indirectly universalism and

European thought, which emphasised the spiritual dimension of Europe and a concept of man in which the human person understood as a unique and transcendent being constitutes the justification of all decisions and actions taken in politics, economy or culture. It is a being that is irreducible to the biological sphere, limited to biological and chemical processes taking place in the human organism or even the mental one, which consists of emotions and cognitive abilities, because in fact there is a rich spiritual sphere in man, encompassing human will, goodness and love. In this spiritual space of his existence, man opens himself to the action of God’s grace (

Machniak 2008, p. 398). He referred to the human being understood in this way in his spiritual dimension in many of his papal speeches, in which he often stated directly that “European culture is marked by the sense of transcendence of the human person, because it is rooted in the fertile soil of Christian faith, according to which man is created in the image and likeness of God […] Christianity nourishes this essential dimension of human life which is the spiritual dimension. Europe, like the nations that compose it, and the people who compose it, can be understood as a spiritual reality marked by a Christian stigma” (

Giovanni Paolo II 1991, no. 44).

Shortly speaking, Karol Wojtyła (John Paul II) saw Europe both in personalistic and spiritual terms closely related to Christianity (cf.

John Paul II 2012), which is a constitutive element shaping European identity and awareness. Hence, in John Paul II’s thought, Europe becomes a “community of spirit”, as he called it in one of his homilies (

Jan Paweł II 2006, p. 911 [no. 4])

5. The source of this way of thinking about Europe is certainly Wojtyła’s interest in the theology of spirituality, which made him sensitive to the spiritual aspects of human experience, seeing in them the essence of human nature and humanity, becoming the basis for his personalism. Precisely in the context of the theology of spirituality, in which Wojtyła, referring to the works of St. John of the Cross, perceives man in the dynamics of transcending himself through acts of cognition and love, as well as achieving new opportunities through union with God, to whom faith is the path (

Machniak 2008, p. 400), we see the proper sense of Europeanness and Europe as a universalist project. Its constitutive feature will therefore be the spiritual experience of man in his continuous process of improvement and self-realisation, as well as building a spiritual community of people, which does not come down to the material sphere, corresponding to the biological sphere of man, and does not even boil down to the sphere of symbols and signs common to the European cultural circle but it touches upon the deepest layers of human existence, the human spirit, which is the foundation for uniting people into the spiritual community that Europe is. Hence, the concept of Europe presented in Wojtyła’s thought and specified in John Paul II’s papal teaching refers to Christian faith and spirituality as a factor constituting Europe.

5. Culture of Europe in the Personalistic Perspective

In the above mentioned article

Gdzie znajdują się granice Europy? [

Where Are the Borders of Europe?], Wojtyła pointed to two types of borders that determine the European space. He spoke about geographical borders—Europe is a space between the Atlantic and the Urals, and in the East the border between the European and Asian continents is rather conventional. That is why we can speak

de facto about the Eurasian continent and Europe as a peninsula of that continent. Wojtyła claimed, however, that such a definition of Europe was insufficient (

Wojtyła [1978] 1994, pp. 28–29). It is much more important for the spiritual history of Europe to define borders “which are within the people themselves”. Wojtyla did not mean mental borders which are a barrier separating “my own” from “strangers”

6, but people aware of belonging to the European cultural community, feeling a bond with spiritual European heritage, and calling themselves Europeans. Through the professed system of values and a sense of belonging to Europe, these people set the right borders of the European space, which deserve to be called more cultural or even axiological than geographical. Such borders do not always correspond to geographic frontiers. This is a deeply personalistic belief; through the experience of being a European the person manifests his Europeanness and as such determines the borders of the European world, which we can basically reduce to the system of values and spiritual heritage from which these values are derived.

Europe is in fact a cultural space in which European consciousness and European values are realised, within which the European community is created, as a deeply relational being created by people linked by the bond of cultural and axiological kinship. Wojtyła’s idea of Europeanness is close to an understanding of Europe which “finds the source of its image in the heart of a person, and not in structures or things. […] The key, centre and sense of Europe is the full self-realisation of man as a person on the individual, community and universal plane” (

Bartnik 1994, p. 136). Europe as a “community of persons” is thus determined by culture, not geography. In Wojtyła’s philosophy and John Paul II’s social doctrine, culture primarily has a personalistic dimension. He reduced culture to a set of facts “in which man expresses himself over and over again more than in anything else. He expresses himself for himself and for others. Works of culture that last longer than man bear witness to him. It is a testimony of spiritual life—and the human spirit lives not only by being in control of matter, but also lives in itself through content that is accessible only to it and that has meaning for it. Thus, he is absorbed in truth, goodness and beauty—and he is able to express his inner life outwardly and objectify it in his works. That is why man, as the creator of culture, bears witness to humanity” (

Wojtyła 1964, p. 1154). Thus, by creating European culture, a person testifies to his Europeanness. Europe in its personalistic understanding is therefore the work of culture or, more precisely, of human culture-creating activity. There is also this feedback here: “Man who in the visible world is the only (ontic) subject of culture, is also its only proper object and goal” (

Jan Paweł II 1988, pp. 54–55). In the European dimension, this means that a person creates European culture, but European culture shapes a “European” person, i.e., his system of values, ethical and aesthetic sensitivity, ideals, etc. This is similar to the nation, which is a great community of people, connected primarily through culture thanks to which and for which the nation exists (

Jan Paweł II 1988, p. 66).

The individual culture of a person emerges in the collective culture of society, which binds individuals and generations. John Paul II believes that: “Society receives it, creatively transforms it and tirelessly transmits it in the process of the succession of generations” (

Jan Paweł II 1988, p. 405). The culture of societies is therefore a niche in which individuals live and grow. The Pope claimed that “culture is the specific way of man’s

existence and

being. Man always lives in accordance with a culture he finds as his own, and which, in turn, creates among men relationships they also find of their own, determining the inter-human and social characteristics of human existence. Hence, the

unity of culture as the proper way of human existence is at the same time the origin of the

multiplicity of cultures among which man lives. Man develops in this multiplicity, without losing essential contact with the unity of culture as the basic and essential dimension of his existence and life” (

Jan Paweł II 1988, p. 54). Thus, John Paul II does not see the possibility of the existence of culture outside society. Culture, which is an attribute of a person, a product of human rationality, is at the same time an inherent necessity in man to live in society. By participating in various levels of social life, i.e., in the family, local community, professional group, nation, supranational European community, etc., a person is prepared to create works of culture. Society makes it possible to educe potential rationality from a person, which is, after all, a factor that constitutes culture. Wojtyła argued that “a community of the human <<I’s>> in their many dimensions expresses that configuration of the human plurality in which the person as a subject is realised to the maximum” (

Wojtyła 2000, p. 407).

Karol Wojtyła formulated the principle of

communio personarum (the community of persons), which also presupposes the final realisation of a universal community encompassing the whole humanity: “The human

I’s in these different dimensions have a disposition, not only to think about themselves in the categories of

we, but to realise what is essential for the

we, and therefore for the social community. Within this community as human, this implies a readiness to realise the subjectivity of many in a universal dimension, and therefore the subjectivity of all” (

Wojtyła 2000, p. 408). The formation of culture, which takes place in a community and through a community, and the recognition of the gradation of communities ultimately leading to humanity as the final community, allows us to conclude that culture in Karol Wojtyła’s philosophy has the features of universal culture.

Personalism is therefore a direct source of universalism in Wojtyła’s philosophy. Personalist universalism begins with the individual, in whom the entire universe of man is focused, i.e., his rationality, spiritual world or culture-forming abilities. In the European dimension, universalism is related both to the universal culture-creating potential of man—a person and the community dynamics of creating culture, manifested in the interpersonal relationship, and the inclusive nature of European culture and its pluralism, binding the diversity of European cultural experiences, which John Paul II repeatedly emphasised during his pontificate. This is what I present below.

6. Axiological Community and Cultural Pluralism

Although John Paul II noticed the importance of pre-Christian traditions and cultures in shaping European identity, and even mentioned the contribution of Judaism and Islam to the development of European culture, for him Christianity was an element constituting Europe, which he emphasised many times during his pontificate. As understood by the Pope, it has the power to harmonise, consolidate and develop other traditions (

John Paul II 2003, no. 19). Europe grows straight out of the spirit of Christianity, hence the conclusion that the borders of Europe coincide with the scope of evangelisation, which he directly indicated during his homily in Santiago de Compostela (

Jan Paweł II [1982] 2008, no. 2). Addressing his papal teaching to Europeans, he spoke of Christian values as the axiological foundation of European identity. European universalism meant for him as much as the universalism of European Christianity. The existence of values common for Europeans, the source of which is the biblical tradition, especially the Gospel tradition, is the foundation of European unity. In 1986, in an appeal to the inhabitants of the Old Continent in Mont Chetif, John Paul II stated explicitly: “The roots of the unity of Europe lie in the common heritage of values individual national cultures hold. The truths of Christian faith are the essence of this heritage. A look at the history of the formation of European nations allows us to see that the progressive inculturation of the Gospel played a decisive role in the life of each nation” (

Jan Paweł II [1982] 2008, p. 160 [no. 3]). Common Christian faith and the values derived from it are therefore, in the opinion of the Pope, the thing that unites all Europeans. The catalogue of fundamental values, due to which the soul of Europe “remains united”, includes primarily such values and social principles as human dignity, commitment to the idea of justice and freedom, diligence and entrepreneurship, family love, respect for life in all its forms, tolerance, solidarity and peace (

Jan Paweł II [1982] 2008, p. 133 [no. 2]).

Both cultural pluralism and the great traditions of European Christianity, Latin and Byzantine, fit in with this axiological unity. Europe consists of two organically related traditions, namely Latin and Byzantine, a different approach from that of previously mentioned Janusz Pasierb, representing the same generation as Wojtyła

7. The West and the East are—as he metaphorically said—two lungs of one organism. He saw culturally different Western Christianity as “more logical and rational”, while Eastern Christianity was “more mystical and intuitive”—they create a complementary whole, a perfect unity of faith and values that finds theological meaning in the person of Jesus Christ (

Giovanni Paolo II 1981, no. 2). There is a spiritual bond between the Church of the West and the Church of the East, just like between the West and the East of Europe. Despite the drama of the division of European Christianity into two separate entities, and in the times closer to us, also the division into two hostile ideological and political blocs, in the opinion of John Paul II, these two great traditions of European Christianity create cultural “osmosis”, constituting the richness of different, but complementary values (

Giovanni Paolo II 1989, no. 3). When he was still the cardinal and archbishop of Kraków, in the above cited article

Gdzie znajdują się granice Europy? [

Where Are the Borders of Europe?] Wojtyła accused especially Western European “people and environments”

8 of limiting themselves to thinking and talking about Europe only in “Western” terms. In his opinion, it was a manifestation of one-sided thinking and, as he put it, “professional malcontentedness” (

Wojtyła [1978] 1994, p. 27). When he became a pope, he expressed a fairly firm belief that the negation of any traditions—in fact, he meant denying the Europeanness of Eastern (Orthodox) Europe—leads to the negation of Europeanness as such. Using a metaphor, he said that Europe cannot breathe without any of its “lungs” (

Giovanni Paolo II 1989, no. 3). Thanks to such a broad perception of the European horizon, not only the Orthodox nations of the Balkans, Eastern Slavs and Romanians, but also Orthodox Caucasian peoples, including Georgians, belong to the European family of nations and cultures. In an address to the Patriarch of Georgia and the Holy Synod, John Paul II stated that Georgia was part of Christian Europe (

John Paul II 1999, no. 3).

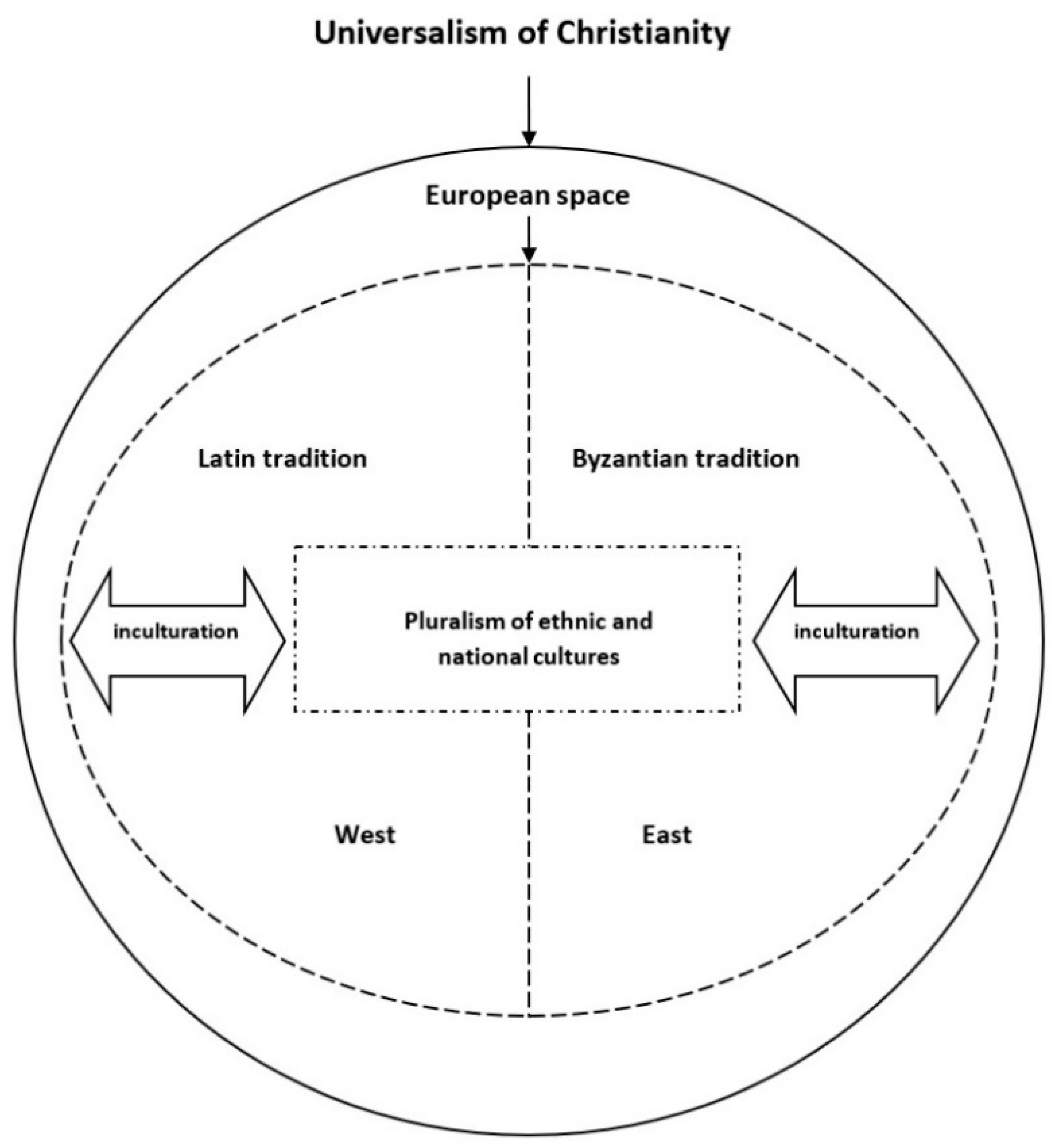

The idea of European unity, understood primarily as axiological unity, emerges from the philosophical, social and theological reflection of John Paul II. Therefore, for the Pope Europe was above all a community of values. Real European unity is not limited to the institutional and legal framework, economy or politics, but includes a system of values common to European peoples and nations. One is a European not only because of the institution of European citizenship or participation in the common market, but also because one shares common values that underpin European identity. These values arise from the universal Christian spirit that coexists with the European richness of spiritual traditions (Latin and Byzantine) and the pluralism of ethnic and national cultures. European universalism, which is in fact axiological universalism, does not negate cultural differences, but strengthens them. As he noted in his last book: “Europe continued to live by the unity of founding values, amid the pluralism of national cultures” (

John Paul II 2012). Ethnic and national cultural particularisms are an immanent part of the universal axiological space defined by Christian universalism created by two great ecclesial traditions, which also enrich the cultural face of Europe. The channel of interaction between Christianity in its two varieties, i.e., Latin and Byzantine, and particular ethnic and national cultures, is interculturation, assuming a feedback between religion and its system of values and principles, but also rituals and rites, and individual cultures. European unity, which in fact can be reduced to axiology, is in fact unity in multiplicity. The model of European unity emerging from the philosophical, theological and social thought of Pope John Paul II is presented in the figure below (

Figure 1).

7. Discussion and Conclusions

Three objections can be formulated to John Paul II’s perception of Europe and its universalist cultural heritage. The first is the fact that despite the internal coherence of the Pope’s philosophy and social doctrine, the universalism contained in it, which is in fact the most original part of his European thought, is disorganised. The universalist reflection permeates Wojtyła’s views and is present especially clearly in his papal teaching. Despite this, we will not find in all his writing any publication that would be a systematic lecture devoted to his universalist inclinations. It is a specific paradox that one of the greatest gardeners of universalism did not devote any separate text to this issue. Nevertheless, the role of the interpreters of his philosophical and theological thought and social doctrine is to perceive the overall picture of universalism in the fragments of thoughts scattered in many philosophical, theological texts and papal speeches. Perhaps Wojtyła himself was not aware of the importance of his considerations for the development of universalist thought. Interpreters and commentators are able to look at the papal thought from the outside, and thus join together scattered threads.

The second objection is related to the fact that while emphasising the importance of the spiritual heritage of Christianity in shaping the axiological community, which Europe is, he does not perceive or marginalise other religions and secular thought. One can agree that his writings often argue with intellectual or secular or atheistic views and attitudes that frequently depreciate the meaning and value of Christianity. Although he recognised the achievements of secular thought, including of the Enlightenment, propagating the postulates of freedom, equality, fraternity and social justice, he saw evangelical roots in them, believing that what is positive in European secular thought is also permeated with the spirit of Christianity (

John Paul II 2012, pp. 112–13). However, in relation to non-Christian religions, the Pope mentioned their contribution to the development of European culture, but also spoke of the openness of Europe as an inherent feature of the Christian heritage. He expressed this best in the already mentioned Exhortation

Ecclesia in Europa, where, also quoting his letter to Czech Cardinal Miroslav Vlk, he stated: “Saying

Europe must be equivalent to saying

openness. Despite experiences and signs to the contrary, which it has not lacked, European history itself demands this: ‘’

Europe is really not a closed or isolated territory; it has been built by expanding overseas and meeting other peoples, other cultures, other civilizations’’. Therefore, it needs to be an

open and welcoming Continent” (

John Paul II 2003, no. 111).

Certainly, however—and here the third objection may be the most serious—Wojtyła’s thinking was Eurocentric. Despite the fact that on the ground of anthropology his universalism is universalism in the strict sense, in the sphere of axiology and ethics it is not only European universalism, but it even takes on a Eurocentric form. Życiński does not agree with this thesis and claims that “

The papal vision of the spiritual unity of Europe is by no means a manifestation of Eurocentrism” (

Życiński 1998b, p. 184). European universalism, as John Paul II himself and his interpreters repeatedly pointed out, is based on the foundations of axiology that stem directly from the Gospel. However, it is not the evangelical roots that determine Eurocentrism, but the conviction that Europe, being the depositary of Christian values, is predestined to a special role in the world. As he noted in a speech to the European Parliament in 1988: “the integrated Europe of tomorrow, open to the Eastern part of the continent and generous towards the other hemisphere, should take up its role as a beacon in world civilisation” (

John Paul II 1988, no. 12). This is certainly not a manifestation of some expansionist ideology, but a strong conviction that European values born of Christianity are indeed universal values. However, a doubt arouses here as to how this axiological universalism can be perceived by representatives of non-European cultures. Even if we recognise that the values born of Christianity or Christian Europe are inherently universal, they are marked with a certain stigma of the culture from which they arise. As Joseph Rathiznger, the Wojtyła’s successor in the Holy See, argues, both Christianity and the European secular-Enlightenment tradition can be considered universal only

de jure, because in fact they are understandable only to few circles of humanity (

Ratzinger 2007, p. 75).

In the case of Wojtyła’s deliberations on culture and its relationships with the personal life of man, universalism takes the form of tout court universalism, universalism as such, or simply universalism. Although Wojtyła’s personalism is inspired by the theology of spirituality, in its mature phenomenological-Thomistic form it transcends religious contexts, touching the personal life of man, which is the source of universality. And, although European or national culture is also present in these considerations, personalistic universalism oversteps the boundaries of individual cultures. The core of the deliberations on Europe, on the other hand, focuses on Christianity as a constitutive factor of the European community of spirit. Although it fits into the universalist vision, at this point universalism becomes in fact European or Christian universalism, which also crosses national borders, and is characterised by openness and an inclusive attitude, though it is connected with a specific religion and civilisation understood as a cultural circle within which different national cultures and traditions coexist. Thus, Wojtyła’s universalism has two faces, while remaining moderate universalism. In his vision of the world, and also of Europe, universalistic elements are intertwined with the pluralism of cultural experiences, the richness of the diversity of cultures and civilisations. With regard to Europe, we are talking about the pluralism of ethnic and national cultures, as well as two different spiritual traditions, i.e., Latin and Byzantine. The affirmation of the existence of various cultural forms protects universalism, also in the European dimension, against standardisation or against the annihilation of distinctiveness, ultimately also of unique features specific to the individual. Just like man—referring to his theology of spirituality taken from the mysticism of St. John of the Cross—does not lose his individuality, his personal, i.e., separate life in the process of uniting with God, so particular cultures and civilisations do not melt into a universal community, regardless of whether it is Europe or the whole world. Cultures live by the power of the spiritual life of man understood as a person. Their vitality will be determined by the spiritual and moral condition of people, members of the community who create and participate in a particular culture and civilisation. The role of Europe or any European nation in Wojtyła is not any political, economic or cultural supremacy. For the world Europe is to be an example of personalistically understood universalism, in which the particular is connected with the universal, that is, first of all, with the affirmation of the person as the highest value, whose good, both material and, above all, spiritual, should be subordinated to political systems and economics which enables him to fully realise himself. This is, in fact, the role of Europe as “a beacon in world civilisation”.