Abstract

This article presents the Hungarian manifestations of a written devotional practice that emerged in the second half of the 20th century worldwide: the rite of writing prayers in guestbooks or visitors’ books and spontaneously leaving prayer slips in shrines. Guestbooks or visitors’ books, a practice well known in museums and exhibitions, have appeared in Hungarian shrines for pilgrims to record requests, prayers, and declarations of gratitude. This is an unusual use of guestbooks, as, unlike regular guestbook entries, they contain personal prayers, which are surprisingly honest and self-reflective. Another curiosity of the books and slips is that anybody can see and read them, because they are on display in the shrines, mostly close to the statue of Virgin Mary. They allow the researcher to observe a special communication situation, the written representation of an informal, non-formalised, personal prayer. Of course, this is not unknown in the practice of prayer; what is new here is that it takes place in the public realm of a shrine, in written form. This paper seeks answers to the question of what genre antecedents, what patterns of behaviour, and which religious practices have led to the development of this recent practice of devotion in the examined period in Hungarian Catholic shrines. In connection with this issue, this paper would like to draw attention to the combined effect of the following three factors: the continuity of traditions, the emergence of innovative elements and the role of the church as an institution. Their parallel interactions help us to understand the guestbooks of the shrines.

1. Introduction: A New Phenomenon in the Practice of Devotion

In 1950, the renowned German ethnologist, Rudolf Kriss, published an article on the cult that was growing around the Capuchin brother Konrad von Parzham of Altötting, who had been canonised in 1934 (Kriss 1950). In his study, Kriss wrote about the increasingly intensive veneration of the saint and drew attention to the appearance of a form of devotion that differed from the traditional. It had become an increasingly frequent element of devotion that the faithful visiting the site wrote long letters to the saint, and in their supplications as part of the Mass, the members of the local religious community said prayers based on the contents of those letters. As the number of letters increased, the communal prayer was discontinued, but the written prayers were carefully preserved (Kriss 1950). In the same year, on the other side of the world, in the Peruvian city of Cuzco, a similar ethnological report appeared on the subject of written prayers placed before the image of Christ in the city’s cathedral (Morote Best 1950). Meanwhile, if we returned to Europe, to the chapel of a tiny village in western Hungary in the same year, we could have made similar observations. Pilgrims to this site were able to write their personal requests and prayers of gratitude in a Guestbook placed there for that purpose (Frauhammer 2012). A few years later, Walter Heim, a Swiss researcher, found, in research carried out in 1961, that these were not cultural relics, appearing independently of each other. He had information on a similar practice found in 40 shrines and 5 parish churches of 16 countries in Europe and elsewhere (e.g., Peru, Ceylon). Further examples could be given, and, advancing both in space and time, we find a dynamic increase in similar devotional practices over the half a century under consideration here.

This study examines the genre precedents, behaviour patterns and religious practices that led to the emergence of this written form of devotion in the period concerned. Is it merely a new element that can be placed in the chain of traditional devotional practices related to the veneration of saints and visits to pilgrimage shrines? Or has it been influenced also by other factors and behaviour patterns far from the context of pilgrimage? The role of the church and its clergy also raises another question. As the keepers of shrines and parishes, what was their role in giving instruction regarding practices related to these cults? How, and to what extent, were they able to influence these processes?

2. The Research

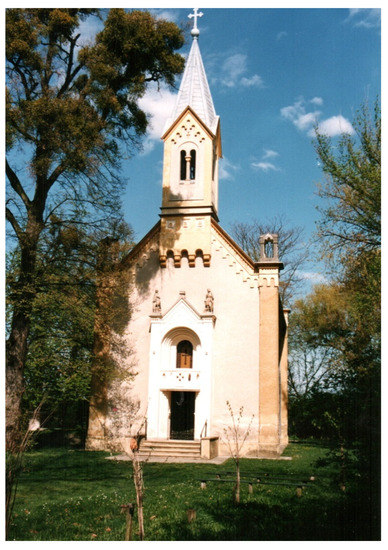

To answer my questions, I carried out research at five shrines in Hungary. The first site was a small village, Máriakálnok, in western Hungary, a lesser-known shrine with a small catchment area (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The chapel in Máriakálnok, Photo taken by Krisztina Frauhammer, 2008.

The faithful here wrote their personal prayers and requests in a thick book known as the Emlékkönyv (Remembrance Book). The parish priest of the village at the time placed it there in 1947, and entries were regularly made until 1952. During this period, 3190 entries were written on 324 pages. There is no information on whether the parish priest was guided by some kind of model in placing the book there, or whether it was his own idea. It was probably because of a few inappropriate entries that he removed it at the end of the five years. This stormy historical period, and the related prayers, lend special interest to the entries. They reflect the difficulties of reconstruction after the Second World War, the relocation of the Germans who had once lived there, and the crises of the newcomers who were settled there. The second research site is located in present-day Slovakia, the Hungarian-inhabited village of Egyházasbást-Vecseklő (Nová Bašta-Večelkov) (Figure 2) (Up to the end of the First World War, the settlement was part of Hungary, but, under the Trianon Peace Treaty of 4 June 1920, it became part of Slovakia.).

Figure 2.

The Chapel in Egyházasbást-Vecseklő, Photo taken by (Krisztina Frauhammer 2012).

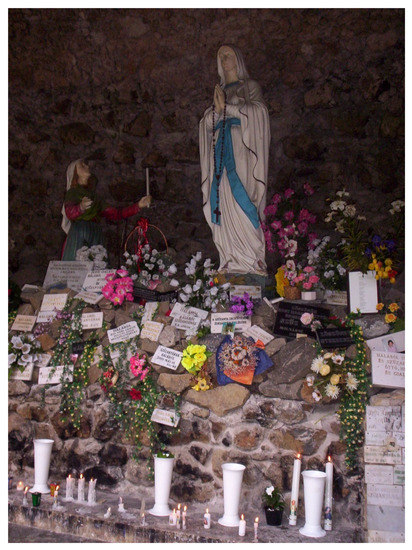

This is a little-known shrine, located in a forest near the village. According to oral tradition, its origin is linked to a miraculous apparition of the Virgin Mary and to the nearby spring with a tiny chapel that was built here (big enough for only an altar and one chair); then in 2012 a new, larger chapel was built. From the 1970s, the woman who cared for the shrine at the time placed small notebooks here to redirect the practice of pilgrims to the site who used to write or scratch their requests and words of gratitude on the walls of the chapel. Since the church had not provided a “guardian” for the shrine, zealous local women kept it tidy. They have always ensured that new exercise books are placed when needed. During my research in 2012, I also observed that the full books were given a new life. They were placed beside prayer books, booklets for pilgrims and rosaries, so that visitors to the place for private devotions also leafed through them, drawing prayer texts from them. Mátraverebély-Szentkút, one of the most famous places of pilgrimage in Hungary, was my third research site. Here, the practice arose spontaneously, under the guidance of the clergy. From the 1990s, people began to leave prayer request slips on the altar of a former hermit’s cave near the pilgrimage church (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The hermit’s cave in Mátraverebély-Szentkút, Photo taken by Gábor Magyar, 2002.

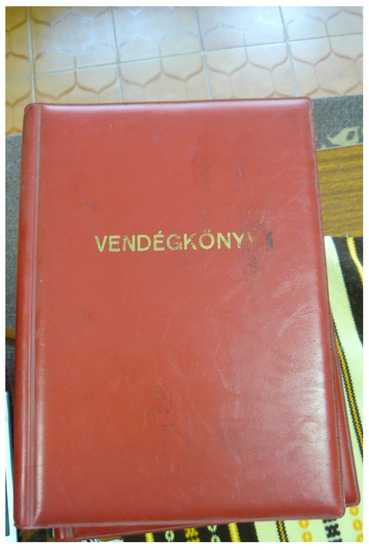

Those who had no paper often wrote on postcards, paper serviettes, pieces torn from diaries, cheques or any other scrap of paper they could find to write their prayer. Each year, when cleaning up in preparation for a major feast day, the paper slips that increased in number from year to year were collected and burnt. This did not hinder pilgrims’ zeal and the practice continued. For over ten years now, pilgrims have been able to write in thick books marked Vendégkönyv (Guestbook) placed within the church, close to the statue that is the object of the cult.

Finally, I chose the shrines at Máriagyűd and Máriapócs as research sites (Figure 4 and Figure 5). Together with Mátraverebély-Szentkút, these are the best-known places of pilgrimage in Hungary. Guestbooks have been kept in Máriagyűd since 1970. While it took 12 years for the first large book with around 200 pages to fill up with prayers, by the end of the period examined, new books had to be made available every year. At first, the names of visitors and donations were recorded in the books, but such data were soon replaced by prayers. The situation is similar at the famous Greek Catholic shrine of Máriapócs, where such books began to be kept in 1900, very early by international comparison. For a long while, entries were made only by persons invited to do so, and the books were only occasionally placed out in the church. This practice has changed since 2001; anyone can write in the book placed on a special stand near the statue.

Figure 4.

The Virgin Mary of Máriagyűd, Photo taken by Krisztina Frauhammer, 2008.

Figure 5.

The Goestbook in Máriapócs, Photo taken by Krisztina Frauhammer, 2008.

The number of books and prayer slips increased from year to year in all these places over the period examined, and this trend continued. The names used vary: Emlékkönyv (Remembrance Book), Látogatási könyv (Visitors’ Book), Vendégkönyv (Guestbook). Whatever the name given to the books, they serve not only to record a visit to the shrine and the date of the visit, but have also become fora for contact with the Virgin Mother, Jesus or other saints.

My precious Virgin Mother!I thank you for opening and smoothing my path so far. Thank you for opening my eyes and guiding me to the right path. I ask you to give me strength and health to continue to serve the health of others and protect the environment. I ask you to help my children too and guide them, give them happiness and family peace. Give my daughter the strength and determination to recover. Watch over my grandchild, my husband, my mother, protect them from self-destruction. I ask you to help me that I continue to have only love left in my heart and be able to cooperate with others too. I love you and your son Jesus. Thank you for everything.(Visitors’ Book of Máriakálnok)

The example cited shows how a distinctive prayer practice has arisen in the books, notebooks and prayer slips in the form of requests and words of gratitude addressed to the Virgin Mother, personal sincere prayers, individual thoughts and confessions. The way they are written has not been formalised either in content, form or style, thereby affording many people the opportunity to enter into contact with various heavenly beings. In this way, a distinctive sacral communication (Lovász 2002) has been achieved through them, in written form, in a public, sacred space of a communal nature.

3. Questions of Definition

On the basis of elements of their function, structure and content, the prayer slips and guestbooks in the shrines presented here can be defined by the term written devotion. The creation of this category can be linked to the authors of the first studies examining sources of a similar nature, Walter Heim (Heim 1961) and Rudolf Kriss (Kriss 1950). They included in this category also the texts of votive tablets, inscriptions and marble tablets on the walls of churches and chapels. Many common features justify the inclusion here of the guestbooks placed in churches and places of pilgrimage. What are these common features? Each of these possibilities creates a forum where visitors can express themselves in writing in a sacred place. The other common feature of these sources lies in the way they come into being and their function. Each manifestation bears witness to the religious devotion of the writer to the sacred, their gratitude, and its public expression. These two things are thus the lowest common denominator of these various text types that can be classified under the genre of written devotion (Kromer 1996, p. 21). If we wish to place the sources of these texts in a wider context, we must mention the votive customs to which they are linked by the act of making internal, religious devotion public. Kriss-Rettenbeck used the concept of promulgation borrowed from legal terminology to describe this act of making public (Kriss-Rettenbeck 1958, p. 98). In this sense, the act of leaving written prayers at shrines is a visible manifestation of the devotee’s reliance on the sacred and their desire to take refuge in a sacred space. It is also a written demonstration of gratitude and praise for the patron of the shrine and their miraculous intercession. It is also a manifestation in writing of gratitude and praise for the patron of the shrine and their miraculous intervention. This act of making public, and the expression of faith on which our definition is based, is characteristic of all devotional manifestations of faith. However, many researchers have pointed out that in the case of entries in shrine guestbooks, considerations of a profane nature pointing beyond religious faith can also be observed. For example, people visiting the shrine as tourists have also written entries in these books as a way of leaving a memory and recording their thoughts. The individual’s existential need also appears in this act: the desire to leave a sign, trace, memory. Other entries suggest that some people used this opportunity in the manner of a diary, and on several returns recorded their state of mind at the particular time in the books placed there. I myself found similar examples in Csíksomlyó (Şumuleu, Romania) the largest shrine of ethnic Hungarians in Transylvania. It is as though they served as a substitute for a missing conversation partner. However, this kind of use shifts the phenomenon away from devotional traditions (Ponisch 2001, pp. 201–12). Related to this use as a diary is a therapeutic aspect that also appears in a number of analyses. Writing down problems is a step towards their solution, it strengthens the feeling that the individual is not alone, and offers the reassurance that the possibility of divine aid exists even if all other explanatory systems fail (Frida 2005, p. 198).

Dear good Virgin Mother!I am very grateful that I can be here before you. I have had such a beautiful experience here it has made my whole soul as light as a feather. I have calmed down and returned with very great pleasure.(Visitors’Book of Máriapócs)

All these considerations indicate that this 20th-century manifestation of the phenomenon defined here as written devotion also has features differing from its traditional forms. Compared to the traditional written devotional forms, we encounter here a far more spontaneous phenomenon where the forms of expression are treated much more freely. This creates the possibility for profane elements and motivations to appear beside the sacred, to mingle with each other, and become blurred. This kind of profanisation could also be observed in the subject matter of the texts; the classical votive themes (sickness, natural catastrophes, wars) were increasingly pushed into the background and, parallel with this, increasing space was devoted to the whole spectrum of everyday life (love, study, workplace problems, family problems, personal conflicts). It is at these points that the difference between church guestbooks and traditional written devotional sources can be seen most clearly.

The circumstances that led to the procurement and placing of such a book can also provide important information for a more precise definition of the books examined. In many cases, the different name given to these books is an unequivocal reference to this context. In Hungary they are called Vendégkönyv (Guestbook), Emlékkönyv (Remembrance Book). In Germany and Austria, the names are Fürbittenbuch, Anliegenbuch, Wallfahrerbuch, Pilgerbuch. In England too, they are also known as Intercessions Books. These local names often indicate the purpose for which they were originally placed there (Eberhardt and Ponisch 2000, p. 12). Concrete information and guidelines placed in them can also indicate the purpose of these books, as is the case in Máriakálnok:

In difficult times and with grave anxiety we open this book of remembrance to the glory of God, in veneration of the Blessed Virgin Mother and as a remembrance for later ages.

For years there was a similar book placed in a church near where I live. The following words could be read on a card placed beside the book:

Write down in this book your individual supplications and expressions of gratitude and the priest will include them in prayers during mass.(Visitors’ Book of Máriakálnok)

Here, through these instructions, the priest or the community encouraged the faithful to write. Here, we may also be reminded of the decisions on liturgy of the Second Vatican Council that attempt to revive the practice of common prayer. The purpose of the guidance set out in Article 53 of Sacrosanctum Concilium was to involve the faithful more fully in the liturgy and to create a certain connection between church thinking and the everyday problems of the lay faithful.

We also know of pilgrimage and parish churches (for example: in Egyházasbást-Vecseklő/Nová Bašta-Večelkov, Mariazell, Eszék/Osijek, Croatia) where a notebook and pen were put out to protect the walls of the chapel from pilgrims who wished to write their prayers on the wall (Lingens 1994, pp. 208–13; Kraack et al. 2001, pp. 21–22; Ponisch 1996, pp. 261–72; Žmegač 1994, pp. 67–76; Frauhammer 2010, 2012). This, too, was a possible way in which the church could channel the practice and motivate the faithful to pray in writing. However, it was not only the church or the parish priest who could motivate the faithful to write down prayers; often it could be the example of another person. At Mátraverebély-Szentkút small prayer slips appeared entirely spontaneously in the early 1990s on the altar of what was once a hermit’s cave near the shrine. The Franciscans who cared for the shrine did not remove them and so, in time, more and more paper slips appeared. Tristan Gray Hulse observed the same process in the St. Trillo chapel in Llandrillo-yn-Rhos, Wales. In 1992 the parish priest there found a paper slip in the chapel. He was so moved by what he read on it that he left it there. After a few weeks, new slips appeared, then more, and this continued without the parish priest encouraging anyone to act in this way (Hulse 1995, p. 33). It therefore seems likely that, even unconsciously, people themselves could also have activated and encouraged each other. What we can see here is quite clearly the spontaneous emergence and spread of the custom. It also shows that even without the conscious guidance of the church, following the traditional behaviour patterns of the veneration of the saints, and pilgrimage practice, the faithful found the forms of expression that helped them to express their everyday problems and needs.

4. Genre Precedents

In the opinion of Tristan Gray Hulse, although it was not until a few decades following the 1950s that church guestbooks spread more widely in Europe and Hungary, the spontaneously emerging practice of written prayers had its roots in centuries-old behaviour patterns, a tradition of cult actions reaching back to the Baroque Age and perhaps even to the Late Middle Ages. What were these genre precedents, and what behaviour patterns and religious practices led to the emergence of this distinctive practice of written prayer? In taking stock of these, we cannot avoid an examination of the intertwining and overlapping of the profane and sacred, as a number of factors indicate that this phenomenon drew from both directions. This is already apparent from the name given to the guestbooks and remembrance books that I examined.

4.1. Guestbooks

The books set aside in places of pilgrimage are most often called Guestbooks, Remembrance Books or Visitors’ Books. Often the book is the kind of large, officially inscribed guestbook used everywhere, and available in shops (Figure 6 and Figure 7). It is worth examining the guestbooks as a pattern because of the similarities of their function. The similarity appears unequivocal and very significant. Numerous entries indicate that many people wrote in these books in the same way as they would in a museum guestbook, presumably because they had come to the shrine principally as tourists, not as pilgrims. The best known of the guestbooks to be found in a profane environment are those in museums, but similar books can be found at exhibitions, events, in hospitals, hotels, shops, restaurants, homes and rented accommodation (Barna 2003, p. 43). What do they have in common? They all serve the purpose of enabling those who write in them, who have stepped out of their accustomed, everyday environment into a situation, event or place that is in some way special to record this fact and to express their feelings, impressions and remarks. The context in which these entries are produced naturally determines the whole nature of the guestbook. Accordingly, expressions of gratitude for recovery, kindness, and good care dominate in hospital guestbooks (Barna 2000, p. 35). In the guestbooks of pensions and hotels, people express thanks for customer service (Barna 2000, pp. 37–38). In the case of museums, the main emphasis is on recording the visit, supplemented by remarks on what has been seen, and expressions of thanks to the curators of the exhibition. These examples also show that the main emphasis in books placed in profane spaces is the expression of thanks, and thoughts related to the context. In his study on guestbooks of a profane nature, Gábor Barna evaluates this way of expressing gratitude differing from the routine, general, oral form as a strategy for the ritualised expression of gratitude (Barna 2000, pp. 40–41). These motivations can also often be found in the guestbooks of shrines and churches, but analysis of the content of the texts shows that this was not the principal function of the entry. They were used mainly to record requests (approx. 60–70%). In this way, the faithful entered into connection with the invisible heavenly powers and expressed the hope that they would help the petitioners in their crises. Examination of the different guestbooks also reveals a distinctive, one-sided communication in all of them. In the case of hotels, guest houses and museums, the person writing an entry sends a message to those who placed the book there, but does not expect an answer. This is another consideration where a distinction can be made between guestbooks used in churches and those in profane environments. The addressees of entries made here are usually not the keepers of the shrine, that is, not those who placed the book there, but a third person: the Virgin Mary, Jesus, or a saint. However, the person writing the entry also expects an answer to the request: the solution of their problems, spiritual consolation, strengthened faith.

Figure 6.

A Guestbook from the archive of Máriagyűd, Photo taken by Krisztina Frauhammer, 2008.

Figure 7.

A Guestbook from the archive of Máriagyűd, Photo taken by Krisztina Frauhammer, 2008.

4.2. Remembrance Books

In Máriakálnok the book placed in the shrine chapel was called Emlékkönyv (Book of Remembrance). In Máriapócs too this name appeared on the title page of a few books. Although not in large numbers, they contain a few commemorative verses as well as topoi often used in such verses (sea of life, storm of life, the thorny path of life). There are also a few drawings similar to those found in remembrance books.

In this quiet chapelDown on your kneesSay a silent prayerFor one most dear to you.18 April 1949, Etelka F. Moson(Visitors’ Book of Máriakálnok)

In addition to these external features, other similarities can be observed. In albums of commemorative verse, we can also witness a ritual communication taking place, principally between two people, but one that eventually becomes a collective creation. Opening the album and writing an entry is a rite of commemoration. The individual collects memories here, adds titles and ensures their safekeeping. This act of recording and leaving a trace, as a motivation, also appeared in the texts of the books examined (Keszeg 2008, p. 219).The remembrance book also has a function of reminding: it preserves a physical trace of persons who are no longer present in the life of the individual: “It is a collection and storehouse of memories, a place to find the thoughts, ideals, commonplaces and emotions of a particular period.” (Keszeg 2008, p. 219). In the case of guestbooks placed in shrines, this reminder function appears mainly as a need on the part of the keepers of the shrine. “In a difficult time and weighed down with serious concerns, we open this book of remembrance to the glory of God, in honour of the Blessed Virgin Mother and as a record for later ages.” This is what the parish priest in 1947 wrote on the first page of the Máriakálnok book. It is for the same purpose that the books are kept and placed in archives: as a reminder and commemoration of the pilgrims visiting the shrine.

4.3. Procession Registers

The genre of procession registers is also related to the remembrance function of the books. In his analysis of the venerated icon of Częstochowa, the Hungarian art historian Zoltán Szilárdfy writes a brief observation on this: “In Czestochowa the names of visitors were recorded in a codex from the Middle Ages.” (Szilárdfy 2003, p. 118). Presumably, this was not a unique case. In the first part of the Guestbook kept in Máriapócs from 1900, and in a separate unit at the back of the book, together with miracle stories, there are many pages containing lists of names. There is only a date and place beside the name, but for a few—mainly church dignitaries—titles are also given. However, after the 1980s, with increasing frequency, short supplications are also found beside the names, and eventually these become the main element. A similar trend occurred in Máriagyűd. The first book placed in the 1970s still contains a large number of lists of names, and, in many cases, the sum of money donated by the pilgrims was also noted beside the names. These numbers declined in later books and were supplemented with supplications. We can conclude from these examples that documentation of pilgrims and important guests and the registration of donations was not a unique phenomenon; this, too, could have been a starting point for the guestbooks full of prayers that later became established in shrines.

4.4. Texts of Votive Tablets and Gratitude Tablets

Throughout Europe there are places of pilgrimage to which pilgrims take donations for prayers, and grace answered or hoped for. For centuries these often took the form of hand-painted ex votos, votive images given as a sign of gratitude or in hope of receiving help (Figure 8). As Salvador Ryan points out: “These all constitute very powerful and deeply-held signs of personal belief. […] It is, in effect, the practice of religion and belief—religion that is ‘lived’ and embodied.” (Ryan 2012, p. 969). The images documented “miracles” worked by Mary or interceding saints, the situation of the person making the vow and the precise time of the emergency. Images of this kind appeared in Europe from the 1500s and already on the lower third had a written part setting out the reason for the request made or gratitude for the answer. The written part was later reduced to the inscription ex voto (from the vow), then from the 19th century, more and more often only the inscription remained, although these again became longer. Tablets of wood, cardboard, metal and most commonly marble, with neither image nor lengthy text, represent the final stage of this transformation. They bear formal, very brief expressions of gratitude or requests, such as “Mary help!” or “Thank you!”, and sometimes also a name, initials and a year (Figure 9 and Figure 10). For the most part, the individual life situation, or even miracle story behind this schematic formula have been completely forgotten. The life story behind such tablets only rarely comes to light. In Máriapócs and Mátraverebély-Szentkút, the keepers of the shrine have tried to record these stories. For this, of course, they needed to know the donors personally and question them about their story. The parish archive in Máriapócs has preserved such records, and in Mátraverebély they were placed among the entries in the Historia Domus. In all cases, these stories have been recounted second-hand. However, the notebook, guestbook or remembrance book placed in the church and accessible for all creates the possibility for anyone who wishes to write down the story behind their gratitude or request. Individuals can decide how much they wish to reveal. It is my conjecture that the spread of writing and its use as an everyday practice (écriture ordinaire) could have been one of the reasons why individuals took advantage of this possibility in the shrines. Écriture ordinaire is manifested in the following of spontaneous behaviour patterns, such as writing a letter, a message, a diary, in a remembrance book or guestbook. Through these forms of the use of popular writing we can document an individual’s life career or its different stages. They can reveal the everyday life world with its struggles, encounters and emotions. At the same time such writing also creates the possibility of maintaining interpersonal connections (e.g., letters), and also for communication of the self. All of these functions appear also in the case of church guestbooks.

Figure 8.

Ex votos in Máriapócs, Photo taken by Krisztina Frauhammer, 2008.

Figure 9.

Gratitude tablets in Máriagyűd, Photo taken by Krisztina Frauhammer, 2008.

Figure 10.

Gratitude tablets in Mátraverebély-Szentkút, Photo taken by Krisztina Frauhammer, 2008.

4.5. Inscriptions on Church Walls—Votive Graffiti

Writing on the walls of sacred spaces has a tradition reaching back many centuries. Inscriptions, scratching and scribbling on walls, buildings and trees are known from pagan times and the early Christian world. We also have data from the Middle Ages on the custom of writing on the walls of sacred places. Walter Heim mentions inscriptions on French and Spanish pilgrimage churches (Heim 1961, p. 12), but examples could also be cited from the Hungarian-speaking territories (Petőfiszállás-Szentkút, Gelence/Ghelina, Romania; Bögöz/Mugeni, Romania, etc.). Scratched inscriptions of this nature, known in the literature of art history as hic fuit also attracted the attention of the renowned Hungarian art historians Flóris Rómer and Géza Entz (Lángi 2004; Entz 1952): “It is a generally valid observation that in secluded places, in corners behind the altar or up on the gallery of mediaeval churches the walls are covered with names, dates and short texts or even drawings, and the scribblers did not disdain to use even mural paintings as ideal surfaces for graffiti.” (Entz 1952, pp. 131–32). Writing and scratching on the walls and objects of religious shrines could be observed continuously after the Middle Ages too, and numerous examples also confirm that it continued as a living practice in the 20th century. For example, at one of the research sites of this study, the shrine chapel at Máriakálnok, up to the early 1990 names (and occasionally also prayers) could be seen written on the drainpipe behind the drinking fountain next to the chapel, left as a memory of all those who drew from the water believed to have healing power. We know from the description given in 1903 by Antal Pávai, historian of the shrine, that this custom was practised by visitors already from the first years of the century: “Recently it seems that it is also a way of expressing gratitude for visitors to write their names on the outside wall of the chapel.” (Pávai 1903, p. 32). At another of our research sites, Egyházasbást-Vecseklő (Nová Bašta, Slovakia), the walls of the little wooden chapel were also used for this purpose and there were even carvings on the trunks of trees in the area. It was precisely because of these carvings that the former custodian of the chapel, Júlia Petrus decided to make a notebook available and so prevent writing on the wall (Barna 1985, p. 176). We still know of many similar examples for other shrines (Ryan 2020, pp. 13–16; Frauhammer 2010, pp. 255–70). Because of their religious content, their presence in sacred places and the figures often associated with them (heart, cross), such inscriptions are known in the literature as votive graffiti (Kraack et al. 2001, pp. 21–22).

Analysing graffiti on the walls of public spaces, James Grasskamp points out that the act of writing in special places raises the author above everyday life and adds greater value to his own person, thereby enabling him to avert a situation fraught with tension (Grasskamp 1986, p. 96). We are dealing with a similar phenomenon in the case of graffiti in shrines. All of the places discussed here are sacred places; pilgrims generally visit them because they believe in the grace and the divine presence that can be experienced here. By writing, persons visiting the church can make their presence visible and thereby seek the protection of the local saint. At the same time, later pilgrims can learn of visitors to the place and the frequency of visits. In this way, these memories are capable of transmitting ideals: they indicate and, at the same time, legitimate the sacrality of the place. In other words, they are evidence of the presence of a kind of communication and the leaving of a memory. The latter factor has a number of aspects. It can be motivated by a kind of existential demand: the need to leave behind a sign or trace: “My body has now decayed, but my handwriting can still be read here.” (Koren 1950, p. 29). Grasskamp regards these commemorative texts (I was here. Name. Date.) as a manifestation and even a routine belonging to the ritual of tourism (Grasskamp 1986, p. 94). This is significant because it is a known fact that visiting a shrine or a chapel in a beautiful natural environment is also a touristic undertaking: besides the religious motivations, it also involves moving out of the accustomed life space, recreation and the desire for physical and spiritual renewal.

4.6. Letters Written to Saints or to God and Heavenly Letters

Together with Walter Heim of Switzerland, Tristan Gray Hulse also regards letters written to God or saints as the primary precedents of the genre (Heim 1961, pp. 13–21; Hulse 1995, pp. 34–36). They saw the letters (these could be either classical letters sent by mail or written on paper and placed on the altar or grave of the saint or Mary) as substitutes for the votive images, or successors of the inscriptions on walls (Heim 1961, p. 13). Walter Heim’s article also contains information on a few shrines where it was the custom to leave name cards, postcards, or images of saints with requests or prayers of gratitude written on them. A similar thing happened in Mátraverebély-Szentkút too, where, in the absence of a notebook, pilgrims wrote on postcards, images of saints, or on any kind of paper that was to hand (paper handkerchiefs, invoices, scraps of newspaper, etc.).

The writing of letters addressed to a saint, to Christ, or the Virgin Mother, has historical roots. Such letters were known already in the 5th to 6th centuries and this kind of letter-writing practice was widespread also in the Middle Ages. The genre reached a peak in the Baroque Age. The faithful placed their letters written to a saint on the saint’s grave, or in a church dedicated to the saint, in a box placed there for that purpose (Heim 1961, p. 14). An image in the shrine chapel at Seppach in Bavaria is evidence of this. The image dates from 1770–1771 and records how people seeking help give little paper slips to the angel who takes them to Saint Joseph who, in turn, passes them to the Infant Jesus. He fulfils the requests written on them and then the angel takes the paper slips back to their writers (Heim 1961, pp. 14–15). It was only from the 19th century that the practice of writing letters became widespread, parallel with the spread of literacy. It was then, too, that the first examples of cheap devotional literature began to appear. These circumstances contributed to the continued existence of that form of letter writing and, as a whole series of examples demonstrate, in many places the custom survived into the 20th century (Hulse 1995, p. 35). Many examples of communication in the opposite direction from saints, God and the Virgin Mother can be mentioned from the practice of letter writing. These letters sent down from heaven, known as Himmelsbrief, appeared in German-speaking territory in the 19th century. They were products of cheap popular literature that spread in the form of small prints or hand-written copies. In Hungary these first came into circulation in the late nineteenth and early 20th century. They were believed to be of supernatural origin, and contained religious information expressed in a naïve, lay form, encouraging readers to respect the religious rules and holding out the prospect of remission of sins (Stübe [1931] 1932; Szojka 1990). Although prayers written in the guestbooks of shrines are not classical letters in form, some of their features do coincide. They usually begin with an address, a salutation, and end with a signature and date, indicating that the writers drew on the generally accepted formulas and patterns. Their style and personal, informal tone, are also often reminiscent of friendly letters.

4.7. Hand-Written and Printed Miracle Stories

In the opinion of many authors, the guestbooks found in shrines are late successors of the miracle books that became known from the Middle Ages (Wienker-Piepho 1993; Hannisch 1986, p. 62; Schneider 1990, p. 205). In these books, we can read records of answered prayers, miraculous healing and miraculous events drawing on features of form and content defined in detail. The stories were generally written and collected by the keepers of the given shrine in order to give greater validity to the special graces that could be experienced at the shrine. The genre was especially popular in the Baroque Age when many records of miraculous answers to prayers were also published in printed form (Tüskés 1993). The measures taken in the Age of Enlightenment in Hungary under the Habsburg ruler Joseph II (1740–1790), who imposed restrictions on shrines and monastic orders, led to the destruction not only of a multitude of relics and votive objects but also of many works of miracle literature (Bálint 1994, pp. 143–53). Although this genre was also present in the 19th century in Hungary, the recording of miraculous events did not recover its earlier intensity and undergo numerous transformations. It “retreated” to the pages of cheap printed literature and the printed material on shrines as a supplement to the history of the shrine and in the section on devotional literature. These publications met the demands of a wider reading public and, in addition, they also contained practical information on pilgrimage (rules for pilgrims, etc.), and on the state of the shrine, and in some cases also on current events. Brochures about the shrine and the place of pilgrimage had been produced for all the places I studied right into the 20th century. They all include a selection of the most famous miracle stories, although only in the form of simple reports. All these indicate that a certain continuity can be found in the recording of miracle stories, even if the intensity of this recording fluctuated. Although some authors question this continuity (Eberhardt and Ponisch 2000, pp. 13–14), my own research confirms that opinion. For example, a brochure on the shrine in Mátraverebély-Szentkút, published in 1999, reports on three miraculous cures that were recorded in 1998 by the parish priest at that time. The other example supporting continuity is the case of Máriapócs where, in 1900, the shrine’s guestbook was opens with the title: “Authentic history of the miraculous weeping icon of the Blessed Mother of Mária-pócs, 1696–1896”. In addition to documents on the origin of the shrine, the book also contains descriptions of miracles that occurred in the pilgrimage church between 1751 and 1959. I counted some thirty over the period mentioned. Some are 4–5 lines long, but others cover up to a whole page. In theme, they all follow the classical miracle subject matter: they report on recovery from an illness. All the miracle records in the book up to 1928 are of this kind, but, from that point on, most of the entries are general expressions of gratitude of varying length (Thanks to You, etc.). We can only assume the existence of a whole series of everyday and less extraordinary miracle stories behind such entries. Despite their common roots, it is possible to identify the points that justify treating the present-day guestbooks at shrines as a separate, independent phenomenon. The most striking difference is perhaps the way in which they are recorded. The miracle stories are always recorded by a church person, a member of the monastic order caring for the shrine, or the parish priest, on the basis of the personal account or written communication of the person experiencing the miracle. This also means that these texts are screened, their form and style edited, the content controlled. In contrast, the entries I examined were made first-hand; their formulation is entirely individual; often very direct; quite close to oral expression. The thematic emphases are also placed differently in the entries made in shrine guestbooks. They indicate that it is now no longer external, existential crises, such as illness, accident, war or natural calamities, that represent a threat, but a whole series of everyday problems. There has quite clearly been an increase in the number of emergency situations where people turn to God, the Virgin Mother or a saint for help. This, too, could explain why, rather than announcing that a miracle has happened and expressing gratitude, these short prayers focus on the longing and request for a miracle.

4.8. Expressions of Gratitude in Religious Papers, Printed Prayer Cards

In discussing related genres, mention must be made of the expressions of gratitude that appeared in religious devotional papers. In contrast to the guestbooks in shrines, here it was the editors of the papers concerned who drew readers’ attention to the possibility of writing down expressions of gratitude. They published the statements sent to them with the conscious aim of thereby strengthening the cult of the Sacred Heart. They differ from guestbooks also in that prayers of gratitude dominate in them. Such declarations of gratitude were known in devotional magazines in Hungary, such as “Jézus Szívének Szentséges Hírnöke” (Holy Herald of the Sacred Heart). The magazine appeared in sixty countries, including twelve times a year in Hungary between 1867 and 1944. Single issues contained 20–30 declarations. They were 2–20 lines long and the majority followed the same pattern (Pusztai 2003). Parallel European examples could be mentioned also from the second half of the 20th century. We also have data on printed forms, printed prayer cards that could be used by anyone to publish their expression of thanks or to write their prayer intention in a church (Hulse 1995, p. 35; Schmied 1997, p. 103). What we see here is a practice aimed at introducing and popularising the writing of individual prayers of request and gratitude.

5. Universal Anthropological Character

Recording individual prayers in writing and making them public in a sacred place is not restricted exclusively to Catholic Christianity. Communication with the sacred in written form is a basic demand and desire of mankind. A similar practice is known among Jews, Orthodox Christians, Coptic Christians, even among Muslims and Japanese Shintoists in given periods. Hand-written prayer slips were known as kvitli among people of the Jewish faith. The term means: little slip, “request slip”. Originally, people turned to miracle-working rabbis for advice, and pilgrims wrote down the reasons for their visit briefly on such slips of paper that were forwarded to the rabbi by his “secretary” before he received the visitors. Often money was expected for this mediation, known as a redemption payment, and the sum was later distributed among the poor. In some cases, the rabbi would write his answer on this slip. A hand-written or printed slip from the rabbi could also be called a kvitli. With some modification, this form of sacred communication continued in the resting place of miracle-working rabbis. By the final decades of the 20th century, this practice became characteristic among the different trends of Jewry, as well as among non-Jews visiting the graves of tsadiks (just men, generally deceased rebbes, orthodox rabbis, in some cases martyrs or their deceased relatives), and persons of other religions. Two variants spread in this connection. In the first case, slips containing requests were placed on the graves of just men by people visiting them. It was held that they had a place in the world to come and so could act as intermediaries, or their merits could serve as grounds for intercession. The other practice is the placing of slips containing requests between the stone blocks of the Wailing Wall. These can be addressed directly to the Everlasting (Gleszer 2005, p. 118). This practice spread both among Israelis and persons living in the Diaspora who were making a pilgrimage to the Wailing Wall. Indeed, in the 1990s such requests could be sent by fax and an organisation undertook to take them to the Wall (Kromer 1996, pp. 9–10).

In the period examined, parallels can also be found among the religious practices of the Japanese shintoists. The faithful paint or write their requests on small wooden tablets (ema) and hang them on the wall set up for this purpose. Earlier, in the Middle Ages it was customary for people to offer horses to the shrines when they asked the divinity, the kami for help in a big matter. In the case of smaller requests, they took the portrayal of a horse on a wooden tablet to the shrine; this became the origin of the 20th-century custom of placing on the wall set up for the purpose images drawn on small wooden tablets (there are no restrictions on what these images can portray). If a wish is fulfilled, another ema is placed on the wall as a sign of gratitude. In their subjects these tablets also covered the whole spectrum of everyday life, just like the church guestbooks we examined (Schmied 1997, pp. 99–100).

Prayer tablets and hand-written prayers also appear among Coptic Christians, and even appear in Muslim practice. In Turkey, it is a known practice that those suffering from a lack of something (most often the longing for a child and in cases of sickness), visit a renowned place of remembrance (a high rock, mountain, the grave of a famous religious leader), and together with the wish they leave a knotted scarf or ribbon. Nothing is written on this; the scarf is a symbolical representation of the request or prayer. Among the orthodox, the names of all the living and dead relatives, and friends for whom the writer would like the priest to pray in later ceremonies, are written on printed forms or blank sheets known as zapiski (Köllner et al. 2009, p. 18).

The practice of writing prayers arising in the course of the last decades of the 20th century not only among the cult of transcendent beings canonised by the different denominations. In the 1980s and 1990s a form of pilgrimage arose around the graves or monuments of stars from popular culture or public figures. Their places of remembrance became sacred places charged with performative power where the visitor could join in a more-or-less independent cult not attached to any further interpreting system—the cult of a star who had become an icon. Here, they could receive spiritual inspirations that could become sources of metaphysical experiences pointing beyond everyday life. Many people began to visit these places in the hope of such experiences, turning to the icon in whom they had invested special power (Margry 2010, pp. 138–39). In this way, the deaths of Jim Morrison, Steve Prefontaine, and Princess Diana—and also their memorial sites—became cult places where transformed elements of the offering and devotional customs of traditional places of pilgrimage also appeared (flowers, candles, leaving commemorative and gift objects, special rites). Among these, in all cases, were hand-written supplications to the star, addressed as a saint, or requesting their intercession (Bowman 2001; Gennet and Rowbottom 2009; Wojcik 2008; Margry 2010).

All these examples illustrate the universal anthropological culture of written devotions spanning religions and cultures. They show that there is a demand present in the culture, independent of religious allegiance, and even outside the field of reference of the given religion for written communication with the person regarded as a saint.

6. Conclusions: Continuity, Innovation, and the Role of the Church

While searching for precedents of a new type of written devotion custom that appeared in the world in the second half of the 20th century, it became clear that there is an overlap and transition among certain traditional forms of devotion. It can be said that at the levels of content, form and function, countless elements of the known traditional written forms of devotion could be identified in the guestbooks. They appear in the 20th-century modern manifestation of written devotion simultaneously (Eberhardt and Ponisch 2000, p. 24). However, in many cases, it is not possible to follow which emerged from what, what replaced which, or what became a substitute for which. Indeed, the order varied from one shrine to another: inscriptions on church walls replaced votive images; the book replaced inscriptions. Elsewhere, the texts of votive images became separate forms and lived on as prayer slips and letters, and then as a book. Elsewhere again, the gratitude tablet and/or a book replaced the votive graffiti, while in still other places, letters written to saints replaced inscriptions on the walls. My investigations in Máriapócs found that supplications replaced the records of miracles. Further, in a number of places, it was the intention that the books should serve a similar purpose to that of guestbooks in museums. In some places, such as Máriakálnok, as examined in the study, books intended for prayers of the faithful appeared without any precedent. In Mátraverebély-Szentkút, another of the places studied, prayer slips began to accumulate spontaneously. How then should we evaluate this devotional practice that appeared in the second half of the 20th century, which draws on a variety of traditions but nevertheless also has new features?

The interactions with parallel phenomena can help us to better understand guestbooks in shrines. The evocation of traditional forms, their combination with specifically modern aspects, and “finally the intertwining of sacred and profane contents, elements and functions are all criteria that make the books a characteristically postmodern phenomenon, even if at first sight all this appears in a church context.” (Eberhardt and Ponisch 2000, p. 24). We must, therefore, consider the combined effect of three factors: the centuries-old traditions and patterns of the devotional practice supplemented with numerous innovative elements, and all this went together with an often conscious church strategy. The new kind of pilgrimage practice presented here arose from all these heterogeneous elements. Even if it is not possible everywhere and always to show a continuous connection with traditional devotional forms, it can be said that the aspiration hidden behind them—that in reality gives rise to these writings—has existed continuously for centuries: to enter into connection in written form with God, a saint or the Virgin Mary, and to make a request or give thanks for the actions taken. Naturally, this always happens in accordance with the demands and world picture of the given age, consequently the traditional forms are always and continuously undergoing transformation with ever newer and innovative elements. The church always follows with attention this popular religious practice and uses it to maintain the connection between the faithful and the church as an institution. Taking all this into account, it can be said that this is an invented tradition in the Hobsbawmian sense. We can find in it—although in a form adapted to the circumstances of our time—the ritual and symbolical elements, rules and motivations of the practice of written devotion that, through repetition, automatically create continuity with the past. Hobsbawm indicates that “these continuities of course are largely factitious, in reality they are responses to novel situations that take the form of reference to old situations.” (Hobsbawm and Ranger 1989, p. 2). Two tendencies come together in this: the constant change and renewal of the modern world; and the unchanging nature of certain behavioural norms of social life (Hobsbawm and Ranger 1989, p. 2). The guestbooks in shrines are good examples of how these two seemingly opposite processes are able to keep the practice of written devotion alive.

Funding

Support provided from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund of Hungary, NKFIH-OTKA Grants FK 21, 132785.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bálint, Sándor-Barna Gábor. 1994. Búcsújáró magyarok. A magyarországi búcsújárás története és néprajza. Budapest: Szent István Társulat. [Google Scholar]

- Barna, Gábor. 1985. Búcsújáróhely a Básti-hegyben. Gömör Néprajza 1: 163–78. [Google Scholar]

- Barna, Gábor. 2000. Gästebücher an Wallfahrtsorten, in Krankenhäusern und Hotels—neue, schriftliche Formen und Quellen ritualisierter Verhaltensweisen. In Konvergenzen und Divergenzen. Gegenwärtige volkskundliche Forschungsansätze in Österreich und Ungarn. Edited by Hrsg von Klára Kuti and Béla Rásky. Budapest: Österreichischen Ost- und Südosteuropa-Institut—Institut für Ethnologie der Ungarischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, pp. 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Barna, Gábor. 2003. Ich bedanke mich für meine Gesundheit. Gästebücher in einem Krankenhaus. In Ritualisierung, Zeit, Kommunikation. Edited by Hrsg von Barna Gábor. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, pp. 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, Marion. 2001. The people’s princess: Vernacular religion and politics in the mourning for Diana. Acta Ethnographica Hungarica 46: 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, Helmut, and Gabriele Ponisch. 2000. Hallo lieber Gott! Aspekte zu schriftlichen Devotionsformen in der Gegenwart. In Konvergenzen und Divergenzen. Gegenwärtige volkskundliche Forschungsansätze in Österreich und Ungarn. Edited by Kuti Klára and Rásky Béla. Budapest: Österreichischen Ost- und Südosteuropa-Institut—Institut für Ethnologie der Ungarischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, pp. 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- Entz, Géza. 1952. XV–XVIII. századi bekarcolások falfestményeken. Archeológiai Értesítő 79: 131–32. [Google Scholar]

- Frauhammer, Krisztina. 2010. Ha testem már az enyészeté, az írásom ott marad. A votív graffitiről a pálosszentkúti példa kapcsán. Ethnographia 2010: 255–71. [Google Scholar]

- Frauhammer, Krisztina. 2012. Írásba foglalt vágyak és imák. Magyar kegyhelyek vendégkönyveinek összehasonlító elemzése. Szeged: Néprajzi és Kulturális Antropológiai Tanszék. [Google Scholar]

- Frida, Balázs. 2005. A vallás és a szupernaturális. Valláskutatás és antropológia: Meghatározások és alapfogalmak. Világosság 7–8: 195–214. [Google Scholar]

- Gennet, Gillian, and Anne Rowbottom. 2009. Born a Lady, Married a Prince, Died a Saint: The Deification of Diana in the Press and popular Opinion in Britain. In Media & Folklore. Contemporary Folklore. Edited by Koiva Mare. Tartu: ELM Scholarly Press, pp. 217–87. [Google Scholar]

- Gleszer, Norbert. 2005. Kvitli. Írott szakrális kommunikáció a magyarországi cadik sírjainál. In “Szent ez a föld…”. Néprajzi írások az Alföldről. Edited by Gábor Barna, László Mód and András Simon. Szeged: Néprajzi Tanszék, pp. 146–55. [Google Scholar]

- Grasskamp, Walter. 1986. A kézírás árulkodó. Címszavak egy graffiti-esztétikához. In Budapesti falfirkák—A Műcsarnok és az Országos Közművelődési Központ közös kiállítása. Edited by Kovács Ákos. Budapest: Műcsarnok, pp. 91–103. [Google Scholar]

- Hannisch, Ernst. 1986. ‘Mama Maria!’ Die Eintragebücher von Maria Plain als Zeitgeschichtliche Quelle. In Salzburgs Wallfahrten in Kult und Brauch. Katalog zur XI. Salzburg: Sonderschau des Dommuseums zu Salzburg, pp. 61–64. [Google Scholar]

- Heim, Walter. 1961. Briefe zum Himmel. Die Grabbriefe an Mutter M. Theresia Scherer. In Ingenbohl. Ein Beitrag zur Religiösen Volkskunde der Gegenwart. Schriften der Schweizerischen Gesellschaft für Volkskunde. Basel: Krebs Verlag, p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- Hobsbawm, Eric, and Terence Ranger, eds. 1989. The Invention of Tradition. Cambrige, New York, Port Cester, Melbourne and Sydney: Cambrige University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hulse, Gray Tristan. 1995. A Modern Votive Deposit at a North Welsh Holy Well. Folklore 106: 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keszeg, Vilmos. 2008. Alfabetizáció, Írásszokások, Populáris Írásbeliség. Kolozsvár: KJNT—BBTE Magyar néprajz és antropológia Tanszék. [Google Scholar]

- Köllner, Tobias, Komáromi Tünde, Ladikowska Agata, Tocheva Detelina, Zigon Jarett, and Benovska Sabkova Milena. 2009. Spreading grace’ in post-Soviet Russia. Anthropology Today 25: 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Koren, Hanns. 1950. Sitte oder Unsitte? Bemerkungen zu Inschriften auf Kapellenwänden. Blätter für Heimatkunde 24: 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kraack, Detlev, Peter Lingens, and Peter Lingens. 2001. Bibliographie zu Historischen Graffiti zwischen Antike und Moderne. Krems: Gesellschaft zur Erforshung der materiellen Kultur des Mittelalters. [Google Scholar]

- Kriss, Rudolf. 1950. Die heilige Verehrung des Hl. Konrad von Parzham. In Bayerisches Jahrbuch für Volkskunde. München: Institut der Volkskunde, pp. 86–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kriss-Rettenbeck, Lenz. 1958. Das Votivbild. München: Callvay. [Google Scholar]

- Kromer, Hardy. 1996. Adressat: Gott. Das Anliegenbuch von St. Martin in Tauberbischofsheim. Eine Fallstudie zur schriftlichen Devotion. In Studien & Materialien des Ludwig Uhland-Instituts der Universität Tübingen 17. Tübingen: Tübinger Vereinigung für Volkskunde E.V. [Google Scholar]

- Lángi, József. 2004. Partiumi falképek kutatása és restaurálása. Siter. In Örökségünk Védelmében. Edited by Emődi Tamás. Nagyvárad: Királyhágómelléki Református Egyházkerület Műszaki Osztálya, pp. 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lingens, Peter. 1994. Zu den historischen Graffiti an den Portalen der Kerzenkapelle in Kevelear. In Historischer Verein für Geldern und Umgegen (Hrsg.) Geldrischer Heimatkalender. Geldern: Landkreis Geldern, pp. 208–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lovász, Irén. 2002. Szakrális kommunikáció. Budapest: Európai Folklór Intézet. [Google Scholar]

- Margry, Peter Jan. 2010. Ein Fest der Fans. Der Kult um Jim Morrison auf dem Friedhof Père Lachaise in Paris’. In Alternative Spiritualität heute. Edited by Mohrmann von Ruth-E. Münster, New York, München and Berlin: Waxmann, pp. 113–41. [Google Scholar]

- Morote Best, Efrain. 1950. Las cartas a Dios. (Folklore Peruano). Separata de la Revista de la Universitaria del Cuzco 97. Cuzco: Universidad del Cuzco. [Google Scholar]

- Pávai, Antal. 1903. A kálnoki csodatevő Mária-szobor, kegykápolna és szentkút története, 1553–1903. Budapest: Stephaneum Nyomda és Könyvkiadó. [Google Scholar]

- Ponisch, Gabriele. 1996. ‘Bitte um weiters Glück!’ Anliegenbücher als Möglichkeit zeitgenössischer Devotion. In Schatz und Schicksal. Steirische Landesausstellung. Edited by Eberhardt Helmut and Heidelinde Fell. Graz: Das Kulturreferat, pp. 261–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ponisch, Gabriele. 2001. ‘Danke! Thank you! Merci!’ Die Pilgerbücher der allfahrtskirche Mariatrost bei Graz. In Grazer Beiträge zur Europäischen Ethnologie Bd. 9. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Pusztai, Bertalan. 2003. Ex voto szövegek. Írott kegyesség a Jézus Szíve kultuszban. In ‘Oh Boldogságos Háromság’Tanulmányok a Szentháromság Tiszteletéről. Edited by Barna and Gábor. Szeged: Paulus Hungarus—Kairosz Kiadó, pp. 267–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, Salvador. 2012. Some reflections on theology and popular piety: A fruitful or fraught relationship. The Heythrop Journal 53: 961–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Salvador. 2020. A little-known Marian Shrine, but one loved by St Teresa of Calcutta, carries the story and hopes of a people. Reality Magazine 2020: 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Schmied, Gerhard. 1997. Lieber Gott, gütigste Frau … Eine empirische Untersuchung von Fürbittbüchern. Konstanz: Universitätsverlag. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Ingo. 1990. Belohntes Vertrauen. Überlegungen zu Struktur und Intention gegenwärtiger Gebetserhörungen. In Volksfrömmigkeit. Edited by Eberhardt Helmut, Hörander Edith and Pöttler Burkhardt. Wien: Selbstverlag des Vereins für Volkskunde, pp. 203–18. [Google Scholar]

- Stübe, Rudolf. 1932. Himmelsbrief. In Handwörterbuch des deutschen Aberglaubens IV. Berlin and Leipzig: Gruyter, pp. 21–27. First published 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Szilárdfy, Zoltán. 2003. Ikonográfia—Kultusztörténet. Képes Tanulmányok. Budapest: Balassi Kiadó. [Google Scholar]

- Szojka, Emese. 1990. ‘Szent levél’ a Bács-Kiskun megyei Tataházáról és lánclevelek Bajáról. In Múzeumi Kutatások Bács-Kiskun Megyében. Kecskemét: Bács-Kiskun Megyei Múzeumigazgatóság, pp. 178–91. [Google Scholar]

- Tüskés, Gábor. 1993. Búcsújárás a barokk kori Magyarországon a mirákulumirodalom tükrében. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. [Google Scholar]

- Wienker-Piepho, Sabine. 1993. Lieber Gott, sei so Fromm, lass uns gut nach Hause komm! Mediavel traditions and modern storytelling in Motorway-Church Manuscripts. In Storytelling in Contemporary Societies. Edited by Hrsg von Lutz Röhrich and Wienker-Piepho. Freiburg: Scriptoralia, pp. 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Wojcik, Daniel. 2008. Pre’s Rock: Pilgrimage, Ritual, and Runners’ Traditions at the Roadside Shrine for Steve Prefontaine. In Shrines and Pilgrimages in Contemporary Society, New Itinerares into the Sacred. Edited by Peter Jan Margry. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam Press, pp. 201–37. [Google Scholar]

- Žmegač, Jasna Čapo. 1994. Mother help me get a good mark in history. Ethnological Analysis of Wall Inscriptions in the Church of St. Peter and Paul in Osijek (Croatia). Ethnologia Europaea 24: 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).