Preliminary Research on the Social Attitudes toward AI’s Involvement in Christian Education in Vietnam: Promoting AI Technology for Religious Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Roles, Benefits, and Challenges of Implementing Artificial Intelligence in Education

2.2. The Application of Technological Advancement and Artificial Intelligence in Religious Education

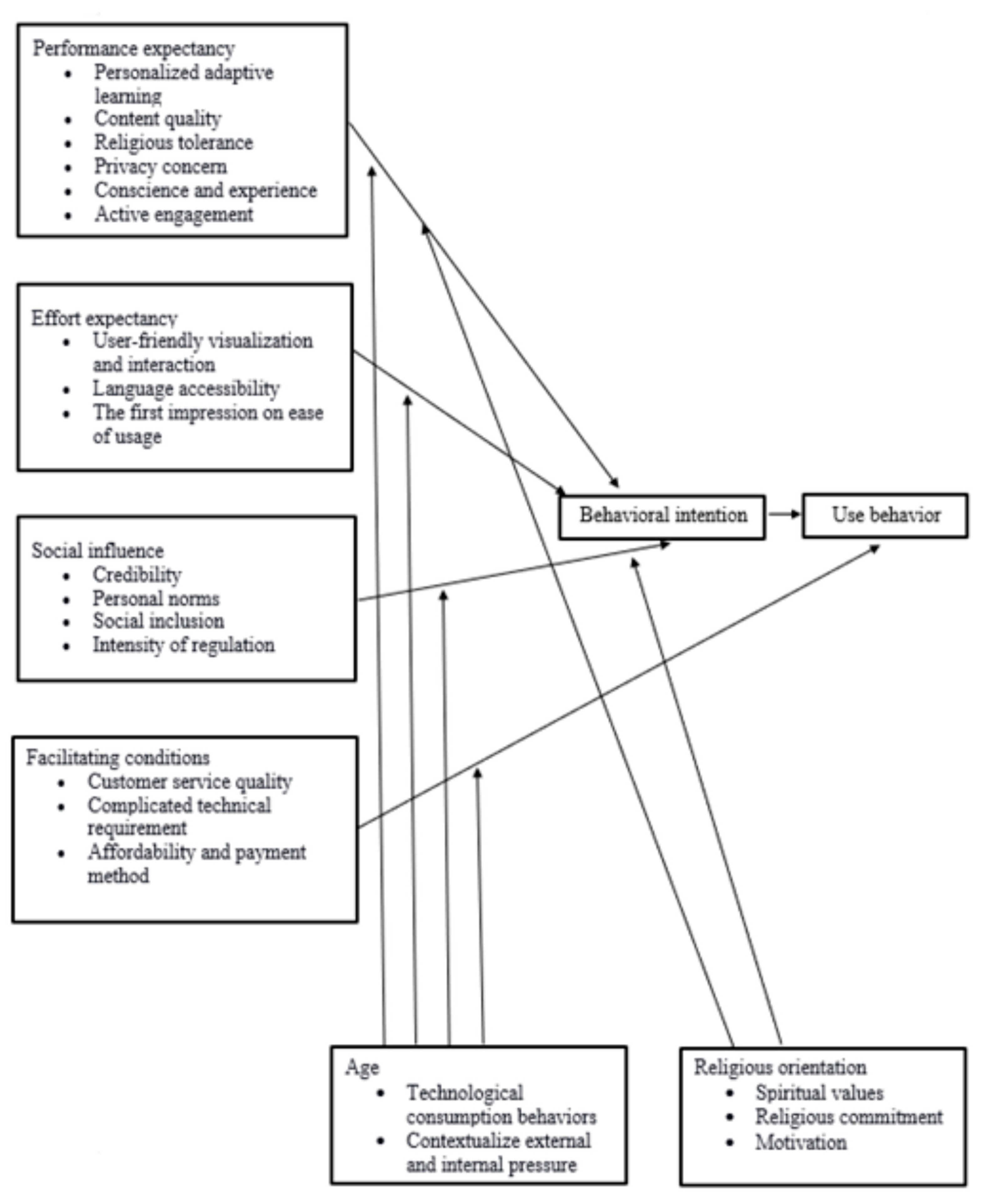

2.3. Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT)

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Setting

3.2. Study Design and Data Collection

3.3. Thematic Analysis Process

4. Data Presentation and Analysis

4.1. Demographics of the Interview Participants

4.2. Motivations to Participate in Religious Education

4.3. The Results of Each UTAUT Construct on Reasons for the Readiness and Acceptance of AIED across Generations

4.3.1. Performance Expectancy

4.3.2. Effort Expectancy

4.3.3. Social Influence

4.3.4. Facilitating Conditions

4.3.5. Religious Orientations

4.3.6. Age

5. Discussion

5.1. The Factors Impacting the Acceptance of the Religious AIED Application

5.2. The Factors Impacting the Readiness to Adopt Religious AIED Application

5.3. Recommendations Improve the Acceptance, Readiness, and Adoption on AI Involvement in Religious Education

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ain, NoorUl, Kiran Kaur, and Mehwish Waheed. 2016. The influence of learning value on learning management system use: An extension of UTAUT2. Information Development 32: 1306–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemi, Minoo, Alireza Taheri, Azadeh Shariati, and Ali Meghdari. 2020. Social Robotics, Education, and Religion in the Islamic World: An Iranian Perspective. Science and Engineering Ethics 26: 2709–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barocas, Solon, and Andrew Selbst. 2016. Big Data’s Disparate Impact. California Law Review 104: 671–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendt, Bettina, Piotr Mitros, Xanthe Shacklock, Michael Blakemore, Allison Littlejohn, and Philippe Kern. 2017. Big Data for Monitoring Educational Systems. Directorate General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2766/38557 (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Berendt, Bettina, Allison Littlejohn, and Mike Blakemore. 2020. AI in education: Learner choice and fundamental rights. Learning, Media and Technology 45: 312–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutani, Ankita, and Preeti Wadhwani. 2018. Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Education. Selbyville: Global Market Insights. Available online: https://www.gminsights.com/industry-analysis/artificial-intelligence-ai-in-education-market (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Porral, Cristina, and Rogelio Pesqueira-Sanchez. 2019. Generational differences in technology behaviour: Comparing millennials and Generation X. Kybernetes 49: 2755–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Lijia, Pingping Chen, and Zhijian Lin. 2020. Artificial Intelligence in Education: A Review. IEEE Access 8: 75264–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, Judith, Amy Glasmeier, and Mia Gray. 2020. When machines think for us: The consequences for work and place. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 13: 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, James, and Dean Knudsen. 1977. A New Approach to Religious Commitment. Sociological Focus 10: 151–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimock, Michael. 2019. Defining Generations: Where Millennials end and Generation Z Begins. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/01/17/where-millennials-end-and-generation-z-begins/ (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Evans, Carol. 2013. Making Sense of Assessment Feedback in Higher Education. Review of Educational Research 83: 70–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firdaus, Endis. 2018. The Learning of Religious Tolerance among Students in Indonesia from the Perspective of Critical Study. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 145: 012032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foronda, Cynthia, Margo Fernandez-Burgos, Catherine Nadeau, Courtney Kelley, and Myrthle Henry. 2020. Virtual Simulation in Nursing Education: A Systematic Review Spanning 1996 to 2018. Simulation in Healthcare: The Journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare 15: 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geraci, Robert. 2013. Robotics and Religion. In Encyclopedia of Sciences and Religions. Edited by Anne Leona Cesarine Runehov and L. Oviedo. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 2067–72. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-1-4020-8265-8_1229 (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Hackett, Conrad. 2019. How Religious Composition Around the World Differs between Younger and Older Populations. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, John. 2018. Teaching Religion Using Technology in Higher Education. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, Wayne, Maya Bialik, and Charles Fadel. 2019. Artificial Intelligence in Education: Promises and Implications for Teaching and Learning. Boston, MA: Center for Curriculum Redesign. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Chi-Yo, and Yu-Sheng Kao. 2015. UTAUT2 Based Predictions of Factors Influencing the Technology Acceptance of Phablets by DNP. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2015: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Marian, Nicole Coviello, and Yee Kwan Tang. 2011. International Entrepreneurship research (1989–2009): A domain ontology and thematic analysis. Journal of Business Venturing 26: 632–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallgren, Carl A., Raymond R. Reno, and Robert B. Cialdini. 2000. A Focus Theory of Normative Conduct: When Norms Do and Do not Affect Behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 26: 1002–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klappe, Eva, Nicolette F. de Keizer, and Ronald Cornet. 2020. Factors Influencing Problem List Use in Electronic Health Records—Application of the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. Applied Clinical Informatics 11: 415–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, Jeremy. 2020. Artificial intelligence and education in China. Learning, Media and Technology 45: 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leswing, Kif, and Alexei Oreskovic. 2019. Anthony Levandowski, the ex Google engineer indicted on allegations of trade secrets theft, previously founded a church where people worship an artificial intelligence god. Business Insider. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/anthony-levandowski-way-of-the-future-church-where-people-worship-ai-god-2017-11 (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Liên, Claire Trần Thị. 2013. Communist State and Religious Policy in Vietnam: A Historical Perspective. Hague Journal on the Rule of Law 5: 229–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Carolyn A., and Tonghoon Kim. 2016. Predicting user response to sponsored advertising on social media via the technology acceptance model. Computers in Human Behavior 64: 710–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malapi-Nelson, Alcibiades. 2019. Transhumanism, Posthumanism, and the Catholic Church. Forum Philosophicum 24: 369–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthes, Jörg, Christine Davis, and Robert Potter, eds. 2017. The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods, 1st ed. Hoboken: Wiley. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9781118901731 (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- McDonough, Carol. 2016. The Effect of Ageism on the Digital Divide Among Older Adults. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine 2: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestechkina, Tatyana, Son Nguyen, and Shin Jin. 2014. Parenting in Vietnam. In Parenting Across Cultures. Edited by Helaine Selin. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Midson, Scott. 2018. Robo-Theisms and Robot Theists: How do Robots Challenge and Reveal Notions of God? Implicit Religion 20: 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulya, Teguh Wijaya, and Anindito Aditomo. 2019. Researching religious tolerance education using discourse analysis: A case study from Indonesia. British Journal of Religious Education 41: 446–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Hung Thanh. 2017. Buddhist-Catholic relations in Ho Chi Minh City. International Journal of Dharma Studies 5: 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Quang, Valčo Michal, Krokhina Julia, Ryabova Elena, and Cherkasova Tatyana. 2020. Religion, Culture, And Vietnam Seen From A Cultural-religious Point Of View. European Journal of Science and Theology 4: 137–49. [Google Scholar]

- OECD.ai. 2020. AI in Viet Nam. OECD AI Policy Observatory. Available online: https://oecd.ai/dashboards/countries/VietNam/ (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Oppong, Gladys, Yaa Saah, Saumya Singh, and Fedric Kujur. 2020. Potential of digital technologies in academic entrepreneurship—A study. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research 26: 1449–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossiannilsson, Ebba, ed. 2019. Ubiquitous Inclusive Learning in a Digital Era. Hershey: IGI Global. Available online: http://services.igi-global.com/resolvedoi/resolve.aspx?doi=10.4018/978-1-5225-6292-4 (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Pedreschi, Dino, and Ioanna Miliou. 2020. Artificial Intelligence (AI): New Developments and Innovations Applied to E-Commerce. Luxembourg: European Parliament Think Tank. [Google Scholar]

- Radenković, Miloš, Zorica Bogdanović, Marijana Despotović-Zrakić, Aleksandra Labus, and Saša Lazarević. 2020. Assessing consumer readiness for participation in IoT-based demand response business models. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 150: 119715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, Mahmudur, Mary Lesch, William Horrey, and Lesley Strawderman. 2017. Assessing the utility of TAM, TPB, and UTAUT for advanced driver assistance systems. Accident Analysis and Prevention 108: 361–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rami, Baazeem. 2020. How Religion Influences the Use of Social Media: The Impact of the Online User’s Religiosity on Perceived Online Privacy and the Use of Technology in Saudi Arabia. Kingston: Kingston University. [Google Scholar]

- Raza, Syed Ali, Nida Shah, and Muhammad Ali. 2019. Acceptance of mobile banking in Islamic banks: Evidence from modified UTAUT model. Journal of Islamic Marketing 10: 357–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, Betty. 1997. Tolerance: The Threshold of Peace. Paris: UNESCO Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Renaud, Karen, and Judy van Biljon. 2008. Predicting technology acceptance and adoption by the elderly: A qualitative study. In Proceedings of the 2008 Annual Research Conference of the South African Institute of Computer Scientists and Information Technologists on IT Research in Developing Countries Riding the Wave of Technology-SAICSIT ’08. New York: ACM, pp. 210–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, Ulrich, and Sarah Delling. 2019. Dealing with worldviews in religious education: Thematic analysis on the topical structure of German RE. Journal of Beliefs and Values 40: 403–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roblek, Vasja, Maja Mesko, Vlado Dimovski, and Judita Peterlin. 2019. Smart technologies as social innovation and complex social issues of the Z generation. Kybernetes 48: 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roll, Ido, Daniel Russell, and Dragan Gašević. 2018. Learning at Scale. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education 28: 471–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rourke, Sue. 2020. How does virtual reality simulation compare to simulated practice in the acquisition of clinical psychomotor skills for pre-registration student nurses? A systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies 102: 103466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, Benjamin, Julius Sim, Tom Kingstone, Shula Baker, Jackie Waterfield, Bernadette Bartlam, Heather Burroughs, and Clare Jinks. 2018. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality and Quantity 52: 1893–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin-Baden, Maggi, and John Reader. 2018. Technology Transforming Theology: Digital Impacts. Chester: William Temple Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Singler, Beth. 2018. An Introduction to Artificial Intelligence and Religion For the Religious Studies Scholar. Implicit Religion 20: 215–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumarni, Woro, Zulfatul Faizah, Bambang Subali, W. Wiyanto, and Ellianawati Ellianawati. 2020. The urgency of religious and cultural science in STEM education: A meta data analysis. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education (IJERE) 9: 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syarif, Syarif. 2020. Building plurality and unity for various religions in the digital era: Establishing Islamic values for Indonesian students. Journal of Social Studies Education Research 11: 111–19. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, Trung, Manh-Toan Ho, Thanh-Hang Pham, Minh-Hoang Nguyen, Khanh-Linh P. Nguyen, Thu-Trang Vuong, and Thanh-Huyen T. Nguyen. 2020. How Digital Natives Learn and Thrive in the Digital Age: Evidence from an Emerging Economy. Sustainability 12: 3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileiou, Konstantina, Julie Barnett, Susan Thorpe, and Terry Young. 2018. Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Medical Research Methodology 18: 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., M. Morris, G. Davis, and F. Davis. 2003. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly 27: 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogels, Emily. 2019. Millennials Stand Out for Their Technology Use, but Older Generations also Embrace Digital Life. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/09/09/us-generations-technology-use/ (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Wright, James, and Andrea Headley. 2021. Can Technology Work for Policing? Citizen Perceptions of Police-Body Worn Cameras. The American Review of Public Administration 51: 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Tao, Yaobin Lu, and Bin Wang. 2010. Integrating TTF and UTAUT to explain mobile banking user adoption. Computers in Human Behavior 26: 760–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 17 (53) |

| Female | 15 (47) | |

| Age | Generation X | 8 (25) |

| Generation Y | 15 (47) | |

| Generation Z | 9 (28) | |

| Educational attainment | No formal education | 0 (0) |

| Less than a high school diploma | 6 (19) | |

| High school diploma | 8 (25) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 17 (53) | |

| Graduate degree | 1 (03) | |

| Working industries (multiple answers) | Religion-related industry | 5 (14) |

| Technology-related industry | 6 (18) | |

| Education-related industry | 10 (29) | |

| Others | 14 (40) | |

| Religious orientation | Christianity | 17 (53) |

| Atheism | 9 (28) | |

| Other religions | 6 (19) | |

| The number of years engaged with Christianity | 30+ years | 11 (61) |

| 21–30 years | 3 (17) | |

| 11–20 years | 3 (17) | |

| 1–10 years | 0 (0) | |

| Less than a year | 1 (5) | |

| The frequency of internet usage | Daily | 28 (87) |

| 1–6 times a week | 3 (10) | |

| Less than once a week | 1 (3) | |

| Never | 0 (0) | |

| The exposure level to artificial intelligence | Experts in fields (AI developers, AI researchers) | 2 (6) |

| Recognize AI applications and engage with AI daily | 6 (19) | |

| Engage with AI daily, but do not recognize the AI applications | 16 (50) | |

| Never heard of the AI concept | 8 (25) | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tran, K.; Nguyen, T. Preliminary Research on the Social Attitudes toward AI’s Involvement in Christian Education in Vietnam: Promoting AI Technology for Religious Education. Religions 2021, 12, 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12030208

Tran K, Nguyen T. Preliminary Research on the Social Attitudes toward AI’s Involvement in Christian Education in Vietnam: Promoting AI Technology for Religious Education. Religions. 2021; 12(3):208. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12030208

Chicago/Turabian StyleTran, Khoa, and Tuyet Nguyen. 2021. "Preliminary Research on the Social Attitudes toward AI’s Involvement in Christian Education in Vietnam: Promoting AI Technology for Religious Education" Religions 12, no. 3: 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12030208

APA StyleTran, K., & Nguyen, T. (2021). Preliminary Research on the Social Attitudes toward AI’s Involvement in Christian Education in Vietnam: Promoting AI Technology for Religious Education. Religions, 12(3), 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12030208