Abstract

This article outlines the missionary methods of the Franciscan Bernardino de Sahagún, his interaction with Nahua communities in central Mexico, and the production of a text called the Florentine Codex. This article argues that the philosophical problem of universals, whether “common natures” existed and whether they existed across all cultures, influenced iconoclastic arguments about Nahua gods and idolatry. Focusing on the Florentine Codex Book 1 and its Appendix, containing a description of Nahua gods and their refutation, the article establishes how Sahagún and his team contended with the concept of universals as shaped by Nahua history and religion. This article presents the Florentine Codex Book 1 as a case study that points to larger patterns in the Christian religion, its need for mission, and its construal of true and false religion.

1. Introduction

Central Mexico as a Mission Field

In 2021, the country of Mexico will hold the 500th-year commemoration of the occupation of Mexico City by Hernando Cortés, his band of Spaniards, and the Indigenous allies that helped him to secure victory at Tenochtitlan, one of three city-states of the Aztec empire (I use Aztec here to center the reader to the region and time period of this case study. Moving forward, I use the term “Nahua”, which is a derived ethnic name from Nahuatl, the language of the area. It is my preferred term. The “Aztecs” were a political alliance between the city-states of Tenochtitlan-Tlatelolco, Tlacopan, and Tetztcoco. I distance myself from the term because it conflates different communities into a single culture and it perpetuates the idea of an ancient people, instead of highlighting that Nahuatl-speakers are vibrant community in the present-day. I am aware that readers are more familiar with “Aztec” than more specific terminology, such as Nahua or Mexica, Tlatelolcan, Tlacopan, or Tetzcocan. By the sixteenth century, nahuatlaca, literally “Nahuatl human”, was a colloquial term to refer to Indigenous people from Mexico City). Tenochtitlan was founded in 1325 and rose to power towards the middle of the fifteenth century. The events that took place a century after in 1521 are not only an epitome of the clash of culture, power, and opportunity, but also of deceit and misinformation. Not long after the abdication of Tenochtitlan’s power, news of marvelous civilizations had reached the eyes and ears of many in Europe. At least two German woodcut newspaper tracts, one possibly printed with the Augsburg press in 1522, published records and depictions of military scenes between Spaniards and Indigenous peoples of the Americas (items J520 A938e and J522 N543z[F], John Carter Brown Library). These early stories had a common source: Hernando Cortés. Beginning in 1519, Cortés commenced a series of letters to Charles V (Cortés 1986), documenting his movements, the peoples he met, and what he saw as the subjugation of Mesoamerican peoples to the will of Christendom. His letters are now considered to be extrapolated versions to favor Cortés’s own assumptions for his actions (Restall 2018).

While Cortés’s letters have come into scrutiny, his descriptions provided an explanation of the need for Christian missions in central Mexico. Nothing may have garnered more anticipation and fervor for missionary work than his description of the Main Temple of Tenochtitlan and the practices he witnessed (I am aware that “missions” and “missionaries” is an anachronistic term to use for Spanish ecclesiastical presence in the Americas (Lockhart 1992, p. 203). I use the term to center the reader). “Amongst these temples [mesquitas], there is one that is the principal one,” Cortés began, “which has no human tongue that can explain its grandeur and particularities” (Y entre estas mesquitas ay vna que es la principal que no ay lengua humana que sepa explicar la grandeza y particularidades della) (Cortés 1522, p. 29; The woodblock print of the original letter housed at the National Library of Spain is unnumbered. For referencing purposes of Cortés’s Segunda Relación, my numbering is based on the total number of pages) (all Nahuatl and Castilian Spanish translations are my own. For primary sources that are available to me, I keep the orthography of the original documents such as/ç/for/z/or/v/for/u/, but I modernize original abbreviations such as/q̂/with/que/and/-â/with/-an/. I keep the orthography used by editors with sources for which I have no access). Buildings in Tenochtitlan had specific architectural forms that dated to earlier centuries of Mesoamerican history (250–900 CE). Known by scholars as a talud-tablero style, the design is an arrangement that consists of an upwards panel (talud) with a protrusion perpendicular to the ground (tablero) that could be designed in various shapes and sizes. These colossal structures had wide staircases down the middle of them with a shrine at their upper-most platform. Cortés admired the prowess and admitted to the beauty of Tenochtitlan architecture, and his contemporary Díaz del Castillo, who wrote an account of the events later in life, did the same (Díaz del Castillo 2012, p. 191). However, their appreciation was short lived. Stone sculptures and effigies depicting the many Nahua divine entities were located throughout the temple precinct and inside the buildings Spaniards encountered. Cortés and his Spanish party dreaded at the sight of them. “The most principal of these idols,” Cortés pressed, “and who they had most faith and belief in, I toppled from their chairs: I threw them down the steps” (Los mas principales destos idolos y en quien ellos mas fe y creencia tenian derroque de su sillas: los hize echar por las escaleras abajo) (Cortés 1522, p. 30). Cortés then asked to have those buildings cleaned from the blood of sacrifices, going so far as to install images of the Virgin Mary and the Christian saints in their place. Destroying images and replacing them with Christian ones, or sometimes none whatsoever, represented one of the many goals of Christian colonialism in the New World.

This article documents how the facilitator of the Florentine Codex, the Franciscan Bernardino de Sahagún (1499–1590), imagined a Christian world in the Americas. It is a case study that points to larger patterns in the Christian religion, its need for mission, and its construal of “true” and “false” religion. In this article, I argue that notions of true and false religion and the concept of exclusive monotheism were entangled in the problem of universals. This was a centuries-old debate on whether the entity of qualities or relations existed, and whether they existed across all cultures. In the early modern period, however, these debates continued to entertain the intellectual curiosity of places such as the University of Paris and the University of Salamanca, centers that shaped European theology and Christian friars in the Americas. On the one hand, these philosophical categories arose in issues of translation for clergy that used Indigenous languages to translate Christianity. Lexicographers were concerned with whether the meaning of words, particularly ecclesiastical entries, could travel from Latin and their cognates in European languages to the many languages of Mesoamerica. On the other hand, part of their translation techniques involved making true and false qualifications to religious categories that did not fit with the vernacular expectations of each ecclesiastical group. The definitions of many entries, for example, were not always equivalent. While some glosses represented the semantic range of a specific headword, others actively falsified Indigenous rituals with idolatry. Scholars of early modern Mexico have approached Mexican religious campaigns with the goal of ascertaining how and why Christian friars used vernacular cues to present the Christian religion (Ricard 1966; Burkhart 1989; Gruzinski 1989; Lockhart 1992). Attention to commoners (Truitt 2018), politics (Crewe 2019), and language (Wasserman Soler 2020) have recently illuminated even more sweeping subtleties to this question. My contribution in the argument is to establish how the problem of universals shaped their strategies.

The iconoclastic scene spelled out by Cortés at the Main Temple of Tenochtitlan is an all too classic trope of Christian missions. Destroy non-Christian images, and replace them with Christian ones. The situation, however, says more about Christian missionary approaches that find their climax in the clash of religion and culture in central Mexico. First, Cortés depended on his own worldview to interpret Tenochtitlan temples. He called them mesquitas, the hispanization of the term mosque (masjid), even though Nahua temples looked nothing like early modern mosques nor closely resembled Islamic architecture. There is room to suggest that Cortés was orientalizing Indigenous peoples, pairing them with Muslims and for that reason establishing them as inferior in Cortés’s mind, but we must also remember that Arabic loanwords had entered the colloquial vernacular of medieval Spain. Cortés used the language he already knew to describe a context he did not. Second, his brief act involved implementing exclusive Christian monotheism. For the purposes of clarity, I define exclusive monotheism in the steps I already noted: destroy non-Christian images and replace them with Christians ones. The iconoclastic actions, however—really what drives iconoclasm then and now—is the intellectual formation to understand the difference between true and false religion (Assmann 2010; Bellah 2011; Leone 2016). An overwhelming characteristic of religions such as Christianity is the argument that their religion is true for simply being monotheistic. To this end, idolatry is a problem only for religions that demand exclusive monotheism, and as such, the concept would have been completely absurd to Mesoamerican communities at the time of contact.

Once the Mexican ruler Moteuczoma, and likely the ritual specialists of the Main Temple, warned Cortés about destroying stone sculptures “for if the communities learnt of it they would rise against me” (porque si se sabia por las communidades se levantarian contra mi) (Cortés 1522, p. 30), Cortés went on to demand and explain the conditions behind true religion. I quote in full:

I made them understand with the interpreters how fooled they were for having hope in those idols that were made by their hands from unclean things. And that they had to know that there was only one universal god, lord of everyone: who had created the sky and the earth: and everything: and made them and us. And that this one was [without?] beginning and immortal: and that they should worship and believe in him and not another creature: nor a thing itself. (Yo les hize entender con las lenguas quan engañados estauan en tener su esperança en aquellos ydolos que eran hechos por sus manos de cosas no limpias. E que avia de saber que avia vn solo dios vniuersal señor de todos: el qual avia criado el cielo y la teirra: y todas las cosas: y hizo a ellos y a nosotros. Y que este era su [sin?] principio y inmortal: y que a el avian de adorar y creer y no a otra criatura: ni cosa alguna).(Cortés 1522, p. 30)

It is hard to imagine early modern Christianity without the conditions set out in this statement. Cortés contended that soon after his exhortation, Moteuczoma and local Tenochtitlan officials removed stone sculptures from their temples and seized and desisted the ritual practice of human execution—which was most worrisome to him. Highly unlikely. Cortés may have added this brief synopsis to demonstrate to Charles V and his court that he was efficient and that a proper Christian ecclesiastical presence was imperative. It would not be long before Tenochtitlan turned on the Spaniards, however, especially after they captured Moteuczoma and held him hostage. Cortés’s explanation of Christian monotheism may have been the first sign of trouble. Hearing that only one god, the Christian one, was deserving of worship was unintelligible to the locals, but more frightening was the idea that all other gods must be destroyed (throughout this article I deliberately use “god” instead of “God”, unless I am quoting from a published source that I am unable to translate. This is not a typo or opportunity for irreverence. Capitalizing a generic noun like “god” as the official name for the Abrahamic deity seems problematic to me. This is especially true in encounters between Christians and Nahuas in the early modern period. God or gods were rarely capitalized in original sources themselves, whether in Franciscan literature from central Mexico or biblical sources, like the letters of Paul in the Christian scriptures. Paul for example, used the Greek phrase “the god” (ho theos), typically in connection to an activity or a person, such as “the god of Abraham”, the “god of the covenant”, or the “creator god”. These idiomatic expressions gave “god” differentiation between Paul’s god and others. As I explain below, one way that friars in central Mexico differentiated the Christian god from the Nahua gods, was by introducing the loan word dios instead of using its Nahuatl equivalent). By claiming that “true” religion was characterized by monotheism and “false” religion by its lack of it, Hernando Cortés and the Franciscan friars that arrived a few years later would map out an intellectual history of idolatry.

The present article moves forward in time to the 1560s, when the Florentine Codex was created, but Cortés theology is a reminder that Christian missions have components of religious exclusivity. Friars from the religious orders that arrived in central Mexico—Franciscans (1520s), Dominicans (1520s), Augustinians (1530s), and Jesuits (1570s)—were certainly more prepared than Cortés in matters of Christian doctrine and theology. They would fully flesh out the significance of true and false religion. It was also they who supervised the production and publication of printed Christian texts in Castilian Spanish and Indigenous languages of Mesoamerica. These included instructions and doctrines, histories, confession manuals and sermons, treatises of idolatry, bilingual dictionaries and grammars, and music and conversion plays. Christensen’s (2013, 2014) salient study of Nahua and Maya Christianity shows that religious orders initially acquired more authority than secular clergy, a contrast to episcopal organization in Europe. More importantly, Christensen notes that competition of territory and doctrinal matters among the orders and later with secular clergy (1550s) contributed to the diversity of Christian expressions. “The problem that religious and civil authorities repeatedly tried to prevent had occurred”, Christensen affirms, “instead of each genre of publication producing one work for all ecclesiastics to work from, multiple versions emerged, each claiming to solve the problems and treat the ailments previous works failed to address” (Christensen 2013, p. 62). Christensen famously identified the multifaceted waves of rules, texts, authors, and their contexts with the plural: Catholicisms. From an outsider’s point of view, the nuances found in the different religious texts may be small in comparison, but they characterized the perspective of each order, where they were stationed, and how they allied with Indigenous communities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Problem of Universals: From Salamanca to Mesoamerica

While debates ensued over which religious order wrote the most transparent Christian instruction, questions over language had long prevailed in Europe. At the onset of the Protestant Reformations, vernacular Christian texts also became a contested subject (Wasserman Soler 2020). The problem of universals was an attempt to explain ontological connections to things and concepts through discussions of natural philosophy, metaphysics, and epistemology. Language was a big part of this endeavor. Known as nominalists and realists, these two philosophical orientations parsed out subjects and predicates, created definitions, taxonomies, and classifications. Scholastic theologians such as Henry Ghent (1217–1293) and Thomas Aquinas (1255–1274), along with John Duns Scotus (1265–1308) and William of Ockham (1285–1347), shaped an entire generation of intellectual thought in Europe through their interpretations of Augustine, Aristotle, and Arabic philosophy. Heider (2014) demonstrates that medieval scholasticism—at least how people began to interpret it—continued to influence early modern philosophical training. Franciscans, Dominicans, and Jesuits of the sixteenth century, especially those coming from Spain, fully embraced the moderate realism of Aquinas and Duns Scotus.

By the sixteenth century, Salamanca became a prominent intellectual center where Bernardino de Sahagún enrolled for his studies, possibly in 1514 (Ríos Castaño 2014, p. 42). Although more prominent Thomistic theologians would not arrive at Salamanca until a decade later, such as the Spanish Dominicans Francisco de Vitoria (1486–1546) and Domingo de Soto (1495–1560), nominalists’ and realists’ debates were a hot topic. De Vitoria, for example, was a lecturer at the University of Paris before becoming chair of theology at Salamanca in 1526. Sahagún had moved on by then, but the University of Salamanca continued to train friars who were eventually stationed in the New World. The work of Castaño (2014), Balsera (2005, 2018), and Pardo (2006) provides a firm basis for connecting the intellectual training at Salamanca with the production of Christian texts in central Mexico. In particular, Ríos Castaño explains that Sahagún was not an anthropologists or participant observer, but a friar intending to instruct Nahuas in the Christian religion. Although it may seem obvious to state that Sahagún was a Christian with an agenda, previous historiography around him, particularly the influential writings of Portilla (1999, 2002), claim that he was a type of proto-anthropologist. Sahagún certainly based his projects on the intention of giving an account of Nahua ritual and religion. His documentary work, such as the Florentine Codex and the Primeros Memoriales (1560s), was a genuine attempt to describe the Nahua world around him. Books 10 and 11 of the Florentine Codex are some of the most beautiful documentations of daily life, flora, fauna, and material culture in central Mexico. However, Sahagún’s reasons behind these works have less to do with the desire for thick description or participant observation. From 1538 onwards, the Spanish Crown had instituted civility campaigns (policía) in the New World with the goal of documenting and instructing Indigenous peoples. One such royal decree the Viceroy of New Spain, Antonio de Mendoza, received asked local officials to center Indigenous peoples into common spaces to ”instruct them in divine things”, but also to “have more detailed knowledge of the things of Indigenous peoples, and clergy could see and know the best way to approach [Indigenous] doctrine and wellbeing” (Para que nuestra fe católica sea ampliada entre los indios naturales desta tierra, y mas aprocheada en ella, seria necesario ponerlos en policía humana para que sea camino y medio de darles a conocer la divina y que por esto se debría dar orden como viviesen juntos en sus calles y plazas concertadamente y que desta manera los prelados podrían tener mas conocimiento de las cosas de los dichos naturales y verían y sabrían la manera y mejor orden que con ellos se podría tener para su bien y doctrina) (AGI, Audiencea de Mexico 1088, (Konetzke 1953, vol. 1, p. 186)). To this end, Ríos Castaño’s intervention recenters Sahagún’s textual corpus. “It is Sahagún’s colonial position to create a corpus of works,” she writes, “that would subject the Nahuas to his Christian culture that propelled the translation of their world into a doctrinal reference text” (Ríos Castaño 2014, p. 32). With this in mind, it is important to consider how Bernardino de Sahagún fits in the overall intellectual formation of Franciscans from Spain who arrived in central Mexico.

When friars such as Sahagún documented “the things of Indigenous peoples”, they invariably turned to their own epistemological orientations. One way to think about the problem of universals in central Mexico is from the point of view of a brief but powerful problem highlighted by Burkhart (1989). “In the Nahua universe”, Burkhart writes, “how to align oneself with good and to avoid evil was not the basic problem of human existence. Rather, one had to discover the proper balance between order and chaos” (Burkhart 1989, pp. 37–38). Nahuas were less concerned about intellectual extrapolations of religion, and more concerned with how to equalize their world through ritual practices. While this is a cultural dilemma, it also presented Christian friars with a problem of translation. Burkhart notes that “good” and “goodness” were harmonized with the Nahuatl terms cualli and cualiztli, from the transitive verb “to eat” (cua). “Bad” (acualli) and “badness” (acualiztli) were not new categories, but only negations of the original nouns. Burkhart argues that Nahuas were relatively amoral, meaning that morality was not divided between an evil material world and a spiritually good one. These idiomatic expressions, moreover, did not have the theological range of good and evil that we find in Christian doctrine. At a basic level, they referred to whether something was edible or not. “These terms”, Burkhart concludes, “were not universal evaluative categories into which all phenomena could be placed. The friars treat them as if they were” (Burkhart 1989, p. 39). Although good and evil, and I add here, truth and falsehood, were concepts introduced by Christian friars, it did not mean that Mesoamerican communities did not have a moral compass. Cualli and cualiztli may have been terms denoting the eat-ability of something, but they functioned as categories of efficacy and non-efficacy. They represented a moral standard that affected how people experienced the world—people had it, divinatory fates had it, and gods had it (see Florentine Codex Book 10). In the end, I believe this is Burkhart’s overall proposal: that Nahua efficacy is not the same as Christian goodness. The imprecise and obviously superficial pairing of “good” and cualli has been the way that scholars interpreted how friars employed vernacular cues in their Christian texts in Indigenous languages.

If we consider Sahagún’s philosophical and theological training, particularly questions of language and meaning, it is very likely he was aware that Nahuatl did not always convey a Christian register. Debates about subjects and predicates and the taxonomies and classifications that nominalists and realists were producing in Spain surely influenced Sahagún’s own perception of the Nahua world around him. In the sixteenth century, the problem of universals became a Franciscan (as nominalists) and Dominican (as realists) disagreement. On the one hand, realists claimed that universals did exist and language was only an arbitrary, human invention of a metaphysical concept. This means that indigenous languages could be harmonized with Christian meaning without fundamentally changing the significance of terms, particularly ecclesiastical ones. Dominican realism features heavily in the work of Romero (2015b, 2019), Sachse (2016, 2019), and Sparks (2014, 2020). The main figure surrounding this ethnohistorical analysis is the Dominican Domingo de Vico (1519?–1555), who co-wrote and supervised a theological account of the Christian religion using K’iche’ Maya vernacular cues entitled the Theologia Indorum (Vico 2010, 2017) (Vico was a contemporary of Bartolomé de las Casas and joined the mission field upon de las Casas’s petition (Sparks 2020, p. 96). With an almost identical trajectory to Sahagún, Vico enrolled at the University of Salamanca where he was introduced to scholastic theology and emerging humanist theories of the early modern period. Unlike Sahagún, however, Vico became a Dominican and went to the Highlands of Guatemala). The Theologia Indorum and the Florentine Codex are vastly different documents, but they share some similarities. On the one hand, the Theologia Indorum is a story of Christianity and the Florentine Codex is an encyclopedia of Nahua ritual and practices, with Christian criticisms peppered throughout the 12 volumes. On the other hand, both works used Indigenous languages, a cohort of Indigenous novitiates, and paired Indigenous cultural cues with Spanish ones. In this work, de Vico went as far as to use the names of Maya deities “creator molder” (tz’aqol b’itol), as well as idiomatic expressions for abundance “yellowness and greenness” (q’anal raxal) to refer to the Christian god’s glory (Sparks 2014). Nominalists, on the other hand, emphasized differences across languages and cultures by claiming that universals could not be common to many beings and concepts, in such a way that they shared their act of being. This position bordered on emphasizing particularities, subjectivities, and relative perceptions of the world (Elliott 2011). Nominalists might argue that translation, especially in non-Latin languages, ran the risk of diluting Christian meaning. It is Duns Scotus’s moderate realism that became more prominent among Franciscans and Jesuits in early modern Spain (Heider 2014, pp. 11–12). Unlike William of Ockham’s nominalism, Duns Scotus tried to reconcile universalism, which he called “common nature”, with individuation or qualities that were unique to individuals, which he termed “haecceity”. For Duns Scotus, the universal was real, but it was always contracted and shaped by the individual (Williams 2019). Sahagún presents an interesting case study because he attended the University of Salamanca, a hub for Thomistic realism, but he was also a Franciscan trained at the Friary of San Francisco at Zaragoza in Aragon, where he consolidated his theological education with the works of Duns Scotus and Ockham (Ríos Castaño 2014, pp. 50–52).

At a time when religious orders in central Mexico were engaged in heated debates over language, Christian instruction, and certainly territorial representation, Sahagún’s training highlights how Christian friars tackled questions of culture, language, and religious authority. Could ecclesiastical terms such as “god”, “contrition”, “sin”, and “grace” be translated into non-Latin languages without risking their fixed meaning in the Christian religion? Did the Nahuatl cualli have the same range as goodness in the Christian sense? Nominalists and realists answered this question differently. The daunting task, however, entailed not only theories of language but also clear expectations of ritual formation in a new environment that friars had only heard about. Turley (2016) shows that not all Christian friars were excited to leave for the New World, in part because many considered the task to be overwhelmingly difficult in relation to maintaining their own religious rules. This was especially true of Franciscans who took a vow of poverty. “The eremitic habitus of so many Franciscan missionaries”, Turley writes, “was starkly incompatible with the intensive mission in new Spain, and the resulting mismatch explains much of the pervasive discontent that we shall see in their writings…the demands of mission work made it virtually impossible to maintain the contemplative practices that had sustained them in Spain” (Turley 2016, p. 55). Bernardino de Sahagún stands out in contrast to what Turley finds among the first Franciscans that arrived in central Mexico. Sahagún fought for his work among the Nahua to be highlighted, which included Nahuatl sermons (Sahagún 1540), admonitions against Nahua rituals (Sahagún 1560), a bilingual Christian doctrine in dialogical format (Sahagún 1986), Nahuatl commentaries on the New Testament (Sahagún 1574), and even Nahuatl songs (Sahagún 1583).

2.2. Alphabetizing Nahuatl

While the Florentine Codex is a completed bilingual work in Castilian Spanish and Nahuatl, the process of writing Nahuatl sounds with the Roman alphabet had its own development. Lockhart (1992) proposed three stages of Nahuatl linguistic change, in which Stage 1 (1519–1550s) had virtually no alteration to the language, but the periodization saw an important attention to alphabetization. This was a process whereby Nahuatl sounds were attached to combinations of Roman letters that transcribed similar or identical sounds in Spanish (Launey 2011). Alphabetization was not uniform, however, because Spanish grammar and orthography were not yet standardized, but also because some sounds had no counterpart to European languages. Nahuatl sounds like/sh/,/tl/, and/kw/required multiple consonants. In Guatemala, where Maya languages were spoken, Christian friars used Arabic characters to pronounce the famous K’iche’ Maya ejectives—voiceless glottalized sounds that produce dramatic sounds when released (Romero 2015a; Sachse 2016; Sparks 2020). The Arabic ayin ع was used for the glottalized/q’/, and the Arabic waw و was used for the glottalized/k’/. This would have been common to individuals coming from the Andalusian region of Spain, where they were exposed to Arabic characters and colloquial Arabic loanwords (Maíllo Salgado 1983). In the Otomi region, grammarians such as Antonio de Guadalupe Ramírez went so far as to create their own characters, borrowing general characterizations of the Roman alphabet but with intriguing modifications, all with the intent to reproduce Otomi sounds (Guadalupe Ramírez 1785; Garone 2013).

Using Roman, Arabic, or modified Roman characters to pronounce Indigenous languages of Mesoamerica was part of the Christian conversion project. It showed that Indigenous languages could be paired with Roman letters. However, writing as a concept was not new in this part of the world, nor was it new in the Nahuatl language (Boone and Mignolo 1994; Lacadena 2008; Zender 2013; Olko 2014). Hieroglyphic representations carved in stone monuments, reliefs, and ritual instruments, such as bones and regalia, or painted on paper made from tree bark, maguey fibers, and deer hide was a common practice of elite Mesoamerican culture. Many of the early colonial texts created in Nahuatl included ideographic and logographic writing, such as the Codex Mendoza, a text delineating the political history and social life of Tenochtitlan (Berdan and Rieff Anawalt 1997). The Florentine Codex also included many illustrations, some of which contained Nahuatl hieroglyphic registers. Kerpel (2014, 2019) argues that the illustrations in the Florentine Codex added layers of semantic meaning to the Castilian Spanish and Nahuatl columns, complementing the thematic descriptions of each chapter.

In central Mexico, Nahuatl became a powerful language, much like a lingua franca, which ecclesiastics and local officials chose as a primary means of communication (Olko 2018, p. 208; Wasserman Soler 2020, p. 104). Officials learned it from adults and children that affiliated themselves with friary education, who in turn learned Castilian Spanish, Latin, grammar, and logic. In the seventeenth century, the famous Franciscan historian, Juan de Torquemada, noted that he learned Nahuatl from Don Antonio Valeriano at the College of Santa Cruz in Tlatelolco, whom he described as learned in Latin, logic, philosophy, and grammar, but also as the man who would become the Nahua governor of Mexico in Torquemada’s lifetime (Torquemada 1615, vol. 1, pp. 114–15). Educating Indigenous children to be trilingual and learned in scholasticism and humanism was seen as the end goal and successful result of Christian instruction. These individuals became the next generation of converted Christians and they enforced their new religion as proxies of intense extirpation campaigns (Crewe 2019, p. 71).

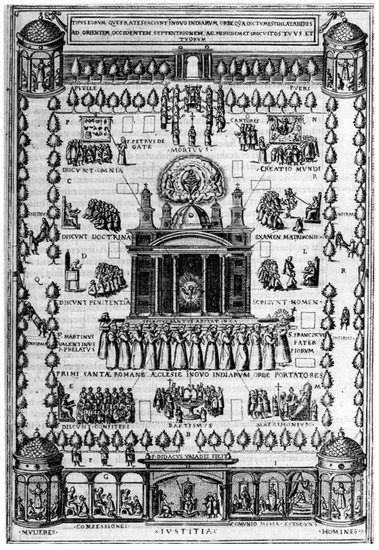

The place to learn how to alphabetize Nahuatl, along with Christian doctrine, history, and ritual formation was in friary colleges, such as the College of Santiago in Tlatelolco. This was a Franciscan center north of the cathedral of Mexico City where the Florentine Codex team gathered. These early Christian churches and colleges were built with the spolia of existing temples and installed directly on top of their perimeters. The use of already sacred spaces ensured that Nahuas were accustomed to the ritual function of its space, but also ameliorated the need for officials to gather people into a newly repurposed plaza (Truitt 2018). The Franciscan Valedés (1579) illustrated how he interpreted the presence of Franciscans in the New World (Figure 1). The image is famously known as “the Ideal Atrium” for its illustration of submissive vignettes of doctrinal activity, including teaching, baptisms, confessions, singing, and vows of matrimony. At the center of the illustration is a group of Franciscans representing the twelve Franciscans that arrived in 1524 with their leader Martín de Valencia, led by none other than St. Francis of Assisi. They carry a church with their backs while the inscription below them reads “The first to bring the Holy Roman church to the New World of the Indies”. Inside the church, a Holy Spirit dove connects all the ritual activity throughout the plaza, aligned vertically with a crucifix on top of the church dome and clouds representing the first person of the Trinity. These centers paved the way for Christianity in the Americas, but also acted as places of “civility” (policía) where Christian friars learned about Indigenous histories and cultures.

Figure 1.

The Ideal Atrium, Valedés (1579), Rhetorica Christiana, vol. 2, p. 106, Newberry Library, Chicago.

2.3. Book 1 of the Florentine Codex

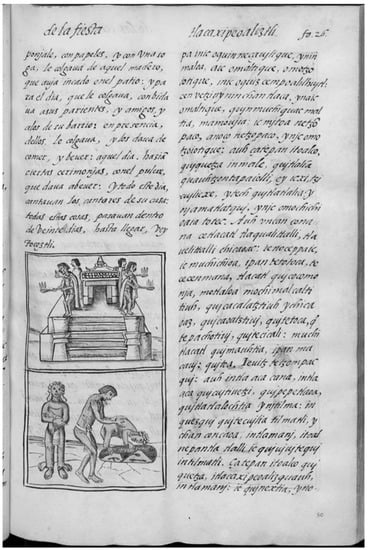

The Florentine Codex was a bilingual encyclopedia of Nahua history and culture, created between the 1540s and 1570s in central Mexico. It included twelve volumes, written by hand in a two-column format with Castilian Spanish on the left and alphabetized Nahuatl on the right. The volumes also contained ideographic and logographic illustrations of thematic scenes that characterized the chapters of each book. Figure 2 is a folio Book 2 (1951) on Nahua ceremonies and it showcases the format of the work. The project was painstaking and long. The Florentine Codex was so arduous, in fact, that some illustrations were unfinished and Nahuatl columns remained untranslated. Although typically attributed to the Franciscan Bernardino de Sahagún, the Florentine Codex was a team effort by multiple Nahua historians. We know some details about them and their training because Sahagún referenced them by name: Antonio Valeriano from Azcapotzalco, Martín Jacobita from Tlatelolco, and Pedro de San Benaventura and Alonso Vegrano, both from Cuauhtitlan. Townsend (2017) highlights that all four men were highly educated, both in their grasp of Nahua history and culture, but also in their handle of Latin and Castilian Spanish. When Sahagún enlisted their help for the Florentine Codex, “Alonso Valeriano from Azcapotzalco” Townsend notes, “had already worked as a teacher at the Colegio [of Tlatelolco]…and Martín Jacobito later became rector” (Townsend 2017, p. 122). These individuals were not unlike Don Antonio Valeriano, the learned Nahua who taught Juan de Torquemada at the same college. It is important to note that Nahuas such as Valeriano from Azcapotzalco, Jacobita from Tlatelolco, San Benaventura and Vegrano from Cuauhtitlan represented a unique type of Indigenous Christianity in central Mexico. Their work as collaborators of the Christian religion was far more public than others. Diel (2015, 2016, 2018) for example has written extensively on the Codex Mexicanus (1590s), a text produced by a Nahua leader of an Augustinian fraternity near to Mexico City. But this source was likely a hidden text. Although it contained conflations of European calendrics and divination, it also included practical applications of Nahua religion. Don (2010) equally identifies different engagements of Indigenous leaders to Christianity, like Martín Ocelotl, Andrés Mixcoatl, and Miguel Poctecatl Tlaylotla, who were accused of actively denouncing Christianity. The Florentine Codex team would see their writings confiscated on two separate occasions due to changing views on recording Indigenous histories and ritual traditions (Terraciano 2019, p. 3), but the Nahuas of the Florentine Codex team had a more amicable relationship to the friars. It is the 1577 confiscated copy that is known today as the Florentine Codex, now housed at the Medicea Laurenziana Library in Florence, Italy.

Figure 2.

Description of the ceremony of Tlacaxipehualiztli, Florentine Codex (1570′s), Book 2, fol. 26r, Medicea Laurenziana Library, Florence, Italy.

Interest in the Florentine Codex began with the paleography and translations of Charles Dibble and Arthur Anderson, but heightened by the New Philology movement of the 1980s (Burkhart 2017). In 2019, the Getty Research Institute announced a long-term initiative to analyze, translate, and launch a state of the art digital platform that would provide global access to the Florentine Codex (Rego Barry 2019). Attention to the magnum opus has involved seminars and conferences such as “Visual and Textual Dialogues in Colonial Mexico and Europe: The Florentine Codex” held in 2015 at UCLA and the Getty Center, which inspired Jeanette Favrot Peterson’s and Terraciano’s (2019) edited volume, The Florentine Codex: An Encyclopedia of the Nahua World in Sixteenth-Century Mexico. UCLA and the Getty Research Institute have sponsored similar conferences and workshops since then, involving scholars from many of disciplines including anthropology, linguistics, history, art history, and religious studies. In addition to a digital publication, the multidisciplinary initiative promises to deliver a lexicon of Nahuatl, Spanish, and English from the Florentine Codex, paired with present-day Nahuatl from the Huasteca region of eastern Mexico. A current digitized copy of the entire manuscript can be accessed through the World Digital Library (https://www.wdl.org/en/item/10096/, accessed on 1 March 2021) or the Medicea Luarenziana Library’s digital repository (http://mss.bmlonline.it/catalogo.aspx?Date=1577, accessed on 1 March 2021).

While the most well-known version of all 12 volumes is located in Italy, it is but one iteration of the completed work. According to Kevin Terraciano, the Florentine Codex team created a Nahuatl copy in 1569, a version that is now lost. It was not until 1575 that the Council of the Indies, the administrative body of Spain’s colonies in the Americas and Philippines, ordered the team to produce a bilingual reproduction (Terraciano 2019, p. 3). Between the first final draft and the second request, the authors gathered more information, made translations, and added pictorial representations to each thematic section. In Terraciano’s proposed chronology for all versions of the twelve volumes, Book 6 on traditional elder knowledge (huehuetlahtolli) was written first, then an account of the conquest of Tenochtitlan later edited as Book 12, and finally a collection of writings on religion, rulership, and human things (Terraciano 2019, p. 3). All twelve volumes were unequivocally encyclopedic. Sometimes these were lexicons, such as Book 11 on earthly things, descriptive studies, such as Book 2 on state-sponsored festivals and Book 4 on almanac interpretations, and historical narratives, such as Book 12 on the conquest of Tenochtitlan. The Prologues to each book were written last in the final editing procedures and without Nahuatl columns. The team arranged their magnum opus with profound intent, but they also engaged their audience by including quasi-parenthetical comments, explaining lexical entries, and even inserting Christian doctrinal standards where they saw fit. Some books even included appendices to substantiate the contents of each topic.

By gathering all this information, Christian friars desired to ascertain pre-existing activities to either eradicate them if they found them idolatrous or repurpose them if they appeared to coincide with the Christian religion (Burkhart 1989; Díaz Balsera 2005; Tavárez 2011). Sahagún began the Prologue to Book 1 by paraphrasing Augustine of Hippo’s Book 2 of the City of God: “The physician cannot with certainty apply the medicines to the patient without first knowing of what imbalance [humor] or from what cause the illness proceeds” (El medico no puede acertadamente aplicar las medicinas al enfermo sin que preimero conozca de qué humor o de qué causa procede la enfermedad) (Sahagún 1988a, vol. 1, p. 31) (Augustine of Hippo’s iteration is as follows: “If only the weak understanding of the ordinary man did not stubbornly resist the plain evidence of logic and truth! If only it would, in its feeble condition, submit itself to the restorative medicine of sound teaching, until divine assistance, procured by devout faith, effected a cure” (Augustine of Hippo 2003, p. 48)). To provide the remedy, Sahagún continued, “it is necessary to know how they used them in their time of idolatry, because through the lack of not knowing this, in our presence they do many idolatrous things without us understanding them” (menester es de saber cómo las usaban en tiempo de su idolatría, que por falta de no saber esto en nuestra presencia hacen muchas coasas idolátricas sin que lo entendamos) (Sahagún 1988a, vol. 1, p. 31). Friars such as Sahagún were concerned with the fluidity of meaning between Nahua and Christian cues. If Nahuas continued to venerate their own deities and believe non-Christian ideas through a Christian contour, ascertaining what those idolatrous things were was of primary importance. Sahagún’s moderate approach to universals likely gave him a sense of how common concepts across many cultures did in fact have unique meanings that were not all the same.

3. Results

Book 1 of the Florentine Codex had many moving parts, but I offer three subsections that help us analyze its content: illustrations and descriptions of the Nahua gods; a Christian theological challenge to the Nahua gods; and a brief and final confession for idolatry. The first and second sections are almost equal in size and, in a certain way, they were meant to parallel each other. The first described the Nahua gods and the second refuted them. Once the Florentine Codex team acquired momentum in their disapproval of non-Christian entities, they began to use the short-hand phrase, “still another” (oc no[uhquiya]) thing, devil, or god to demonstrate the confusion behind idolatry and false religion. The brief confession that ends the Appendix to Book 1 is a first-person singular (“I”) recitation, presumably to help readers repent for their idolatry. The confession was meant to accompany the rest of the texts for anyone ready to speak of Nahua ritual practices which they may have seen or heard about.

3.1. Book 1: The Gods

The Nahuatl word for god or divine entity is the morpheme teotl, a single unit of language that can be compounded into nouns or incorporated into verbs. That teotl is phonetically similar to the Greek theos is purely coincidental. Additionally, while Nahuatl bilingual dictionaries, such as Alonso de Molina’s (Molina 1571), did pair teotl with “god”, we must not assume total equivalency with a Christian idea of a transcendental entity or its temporal representation. Teotl is in fact a very fluid term. Bassett’s (2015) study of Nahua gods shows that the lexical entry evoked culturally specific properties, such as a teotl’s personal possessions, specific fate, exclusive and marvelous things, and valuables. A teotl, moreover, was brought to life by human beings (teixiptla). Women and men ritual specialists, volunteers, and city-state captives were conjoined to the gods through regalia transformation, a ritual procedure that could sometimes take up to a year to complete (Olivier 2008). Any Nahua god was inseparable from the rituals that gave these items importance, making the concept quite distinct from “god” in a monotheistic or theistic sense. Adding to the complexity of the term, teotl could change meaning when acting as modifier of another lexical entry. Teotetl, for instance, a compound of “god” (teotl) and “stone” (tetl), does not refer to a divine stone, but to “perfect blackness” (Bassett 2015, p. 145) or the material “jet” (Sahagún 1963, p. 228). Other compounds such as “yellow-leafed maguey” (teometl, “god” teotl + “maguey plant” metl) and “gold” (teocuitlatl, “god” teotl + “excrement” cuitlatl) used teotl to accentuate the yellowness of an item. This means that semantically teotl acted as an intensifier of a particular item or entity. The lexical entry had various functions, both as a concept for a god, but also as a modifier of other concepts—it is in compound nouns and verbal incorporations that we can see the full semantic range of the word (Bassett 2015, p. 94).

While teotl may have had a wide scope of meaning, in Book 1 it was generally used as a morpheme referring to Nahua gods, respectively. The direct loanword dios or its Nahuatlized variation, tiotzin, was used to refer to the Christian god, often accompanied with the idiomatic expression “our lord god” (totecuiyo dios). This was not systematic, however. The Florentine Codex team did use teotl to refer to the Christian god sparingly later in the Appendix to Book 1 (Sahagún 1970, pp. 61, 63, 69), but also in refence to “the word of god” (teotlahtolli) and “the light of god” (teotlanextli) (Sahagún 1970, pp. 63, 69). Sometimes the team used teotl to qualify between “true” and “false” gods. “There was no other god [teotl]”, they noted, “for only you [i.e., the Christian god] are god [titeutl]” (Sahagún 1970, p. 61) (the phoneme/o/also had the range of/u/, like in prove, and colonial Nahuatl orthography varied in its alphabetic representation teotl (Launey 2011, p. 4)). An entire paragraph is dedicated to the straightforward phrase: this god is no god. “Huitzilopochtli”, the patron deity of Tenochtitlan, the authors contended, “is no god. Tezcatlipoca is no god. Tlaloc or Tlalocateuctli is no god” (ca amo teutl, in vitzilubuchtli: amo teutl, in Tezcatlipoca, amo teutl in tlaloc, yn anoço tlalocatecutli) (Sahagún 1970, p. 63). We may wonder how effective it must have been to explain differences between a true and false teotl while using the same term to both affirm it and negate it. However, the Florentine Codex team did not leave things to chance. In the next section of Book 1, where idolatry was examined, the team planted a firm distinction between what was a true and false divine entity, by separating the ontological differences between the Christian god and the Nahua ones.

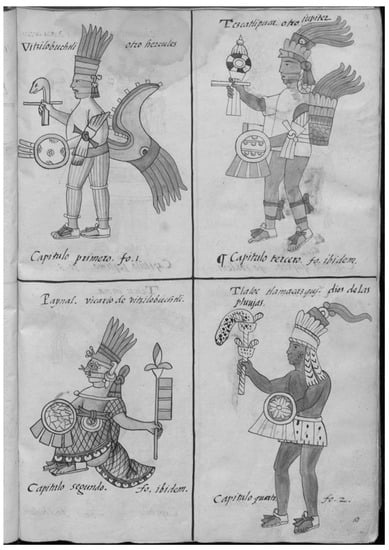

Encyclopedias of non-Christian deities existed in the early modern period, and it is possible that Sahagún was exposed to them in his training in Spain. Sources that Boone (2019) highlights in the creation of Book 1 is Georg Pictor’s Theologia Mythologica (1532), Lilio Gregorio Giraldis’ De Deis Gentium (1548), Natale Conti’s Mythologiae (1555), and Vincenzo Cartari’s Le Imagini con la Spositione de i Dei de Gliantichi (1556), which were descriptions of gods, their attributes, and iconographies. Boone also notes, however, the obvious use of Nahua pictorial codices from divinatory almanacs, such as the Codex Borgia or Codex Borbonicus. “Such studies, or the idea of such studies,” Boone writes, “probably helped Sahagún frame what questions he would ask of his informants, what information the team would ultimately include, and how it would be organized” (Boone 2019, p. 102). In the presentation of the gods of Book 1 (Figure 3), each cell contained a two-dimensional illustration of a Nahua deity that was specific unto itself, with particular body-paint, regalia, and attributes. Molly Bassett’s study (Basset 2015) demonstrates that gods possessed specific clothing and the Florentine Codex team applied such characteristics when they illustrated and described each divine entity in the Nahua pantheon of gods. The team included only twenty-four illustrations, twenty gods and four of the sacred bundles (tlaquimilloli) that acted as effigies of bodies, essences, and powers related to specific deities (Bassett 2015, 2019). By no means was twenty the total in the pantheon. In an earlier iteration, known as the Primeros Memoriales (Sahagún 1997), the team included thirty-six gods and five sacred bundles. The reason the list was reduced by almost a third was because some Nahua gods were characteristics of others or appeared as their representatives. Paynal, for example, was the representative of Huitzilopochtli, but he was nevertheless described as a separate entity in Book 1 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Illustrations of the gods Huitzilopochtli (top-left), Paynal (bottom-left), Tezcatlipoca (top-right), and Tlaloc (bottom-right), Florentine Codex, Book 1, fol. 10r, Medicea Laurenziana Library, Florence, Italy.

What is interesting in the presentation of the Nahua gods is how the team paired them with Roman deities. Their conflation was not uniform for all twenty-four of them, but the various pairings reveal how Sahagún may have found commonalities between two distinct ancient societies. The Florentine Codex team tried to describe a non-European world by referencing an ancient culture Europeans already knew and understood. Laird (2016) and Olivier (2008), who make similar cases, note that associations between Roman deities and Nahua ones were not meant to be substantive, but rather superficial and highly pejorative.

While paring Roman and Nahua gods together was meant to harbor negative connotations, Boone notes (2019) that the team made a significant effort to be objective. Some descriptions were longer than others, and the goal was to enlighten the reader on the regalia, associated rituals, and powers behind all twenty-four entities. As a bilingual text, however, the Castilian Spanish and Nahuatl descriptions were not the same. The conflation with Roman gods appears in two places, but never in the Nahuatl columns. First, they appear in brief captions over the illustrations that introduce Book 1. Based on the centering of the line-drawings, it is likely the captions were written after the fact, as the text moves in an awkward position in relation to each illustration (Figure 3). Second, the conflations form part of the Castilian Spanish columns in the text that follows. Castilian Spanish translations and paraphrases of the Nahuatl text helped bilingual readers and non-Nahuatl readers understand the content of the manuscript. In them, Sahagún paired Huitzilopochtli with Hercules, the strong man demi-god (Sahagún 1988a, vol. 1, p. 37), Tezcatlipoca with Jupiter, the god of the skies (Sahagún 1988a, vol. 1, p. 38), Chicomecoatl with Ceres, the god of agriculture (Sahagún 1988a, vol. 1, p. 40), Chalchiuhtlicue with Juno, the goddess of fertility (Sahagún 1988a, vol. 1, p. 42), Tlazolteotl with Venus, the goddess of beauty (Sahagún 1988a, vol. 1, p. 43), and Xiuhteuctli with Vulcan, the god of fire (Sahagún 1988a, vol. 1, p. 47). The Nahua god Tezcatzoncatl was paired with Bacchus, the god of wine and Cihuapipiltin, a cohort of promiscuous women, with nymphs in the illustrations, but not in their textual description.

By referencing Roman deities, Sahagún helped to explain a world that others did not or would not completely understand. The Florentine Codex team was trilingual (Nahuatl, Castilian Spanish, and Latin), but mentions of Roman deities do not appear in the Nahuatl columns, suggesting they served as cultural cues for Castilian Spanish readers. The descriptions of the Nahua gods were not a philosophical account on the similarities between Roman gods and Nahua gods, but we can imagine that a discussion must have ensued as to how best to present the information the team gathered. If Huitzilopochtli was a type of Hercules and Tezcatlipoca a type of Jupiter, it showed there were general commonalities that existed across cultures and languages. The problem of universals is evident in the fact that the team bestowed analogies between two distinct cultures. If Sahagún was sympathetic towards realism, insofar as Scotism allowed for universals to exist in particularities, analogy helped to bridge the gap between Huitzilopochtli and Hercules. In Thomistic realism, there are at least two forms of analogy, one in which a third concept or object connects the analogous items in question (indirect analogy), and another in which the items in question are analogous due to their relationship (analogy of proportion). Thomas Aquinas differentiated analogy by using health as an indirect and proportionate concept (Aquinas 1947, vol. 1, p. 13). We do not know what the Florentine Codex team had in mind when they paired Roman and Nahua gods because they do not explain it, but if the next section is any indication, it may be that “idolatry” was the indirect concept of analogy between them.

3.2. Book 1: The Idolatry

After the descriptions of all twenty-four entities that appear in Book 1, the Florentine Codex team moved on to establishing reasons to eradicate and refute their value. The Nahua gods were not like the Christian god and Book 1 is a Nahuatl Christian account of idolatry. Laird (2016) and Olivier (2016) both point out that the Appendix to Book 1 was meant to match similar refutations of idolatry in the Christian religion. Treatises like Justin Martyr’s First Apology (150s CE) and Augustine of Hippo’s City of God (426 CE) explained why Roman gods were false and the Christian god was true.

Sahagún took many cues from Augustine’s exclusive monotheism, quoting him in the Prologue to Book 1 with the metaphor of the physician. “They themselves [i.e., Romans],” wrote Augustine in the fifth century, “although realized the uselessness of such rites, believed that religious worship should be offered to the order of nature which is organized under the rule and government of the one true God” (Augustine of Hippo 2003, p. 172). Since the Christian god was the only target of veneration and worship, “Romans were, in the words of the Apostle, ‘serving the created order, instead of the creator, who is blessed for all eternity [Romans 1.25]” (Augustine of Hippo 2003, p. 172). Augustine contended that Romans worshiped personifications of nature instead of their true creator. In the Prologue to Book 3, focused on the origin of the Nahua gods, Sahagún once again compared his work to Augustine’s City of God, saying, “Just as he says [i.e., Augustine], knowing the fables and vain fictions that the gentiles had about their pretend gods, we may more easily give them to understand that those were not gods, nor could [these gods] give any such thing that would be beneficial to the rational creature” (No tuvo por cosa superflua ni vana el divino Augustino tartar de la teología fabulosa de los gentiles en el sexto libro de La cuidad de Dios, porque, como él dice, conocidas las fábulas y ficciones vana que los gentiles tenían cerca de sus dioses fingidos, pudiesen fácilmente darles a entender que aquéllos no eran dioses ni podían dar cosa ninguna que fueses provechosa a la criatura racional) (Sahagún 1988a, vol. 1, p. 201) (early modern Castilian Spanish lexicons paired the term gentiles with idolatry, paganism, and ignorance of Christian monotheism (Covarrubias 1995, p. 434)). The Florentine Codex team sat down at the College of Santiago Tlatelolco not to be ethnographers, but to record non-Christian knowledge, rituals, practices, and histories, for extirpation and idolatry campaigns. Comparing idolatry to an illness, Sahagún sought to identify “the root of where they [i.e., Nahua rituals] come from, which is mere idolatry” (…la raíz de donde salen, que es mera idolatría) (Sahagún 1988a, vol. 1, p. 31). In his mind, this information would help confessors and preachers who “do not even ask about nor think that there is such thing [i.e., idolatry]” (los confesores ni se las preguntan ni piensan que hay tal cosa) (Sahagún 1988a, vol. 1, p. 31).

The way that the Florentine Codex team centered their interpretation of idolatry was through the Vulgates’ Book of Wisdom. This is one of the few instances in which the accompanying columns to the Nahuatl text was composed in Latin, not Castilian Spanish. They copied Chapter 13 and 14 verbatim, but then interpreted the biblical texts in the context of the central Mexican experience. The authors hoped that their refutation of the Nahua gods would be heard among “the people of New Spain, the Mexica, the Tlaxcalans, Cholulans, Michoacans, and all the commoners [anmacehoaltin] who walk on the land of the Indies” (antlaca, in nueua españa: in anmexica, in antlaxcalteca, in ancholulteca, in anmjchoaque, yoan in amjxquichtin in anmacehoaltin, in njcan annemj in india tlalli ipan) (Sahagún 1970, p. 55). More importantly, they hoped that by hearing the word of god (teotlahtolli), readers would come to understand the difference between true and false religion.

“The people of this earth who do not know god [dios] are not counted as people,” is how the refutation began—“they are only unfortunate, useless…from them [i.e., god’s creations] they should have grasped the revered knowledge of god [dios]” (Jn tlalticpac tlaca, yn amo qujmiximachilia in dios, ca amo tlaca ipan pouj, ca çan nentlaca, nenquizque…intech qujcuizquja, in jximachocatzin dios) [Wisdom 13.1] (Sahagún 1970, p. 55). Instead, the text continued, “they were confused [by] god’s creatures [dios]. They worshiped the fire, the water, the wind, the sun, the moon, the stars” (çan ītech omotlapololtique yn jtlachioalhoan dios: oqujmoteutique in tletl, in atl, in ehecatl, in tonatiuh, in metztli, in cicitlalti) [Wisdom 13.2] (Sahagún 1970, p. 56). Readers more familiar with the English translation of this verse can note the awkward variation from Latin to Nahuatl, along with my own attempt to translate it to English (the choice to introduce a third language is not stylistic, but instead reflected the specialized use of scripture. It is a direct copy of the Latin Vulgate). The use of the Book of Wisdom was not arbitrary, but accentuated the team’s effort to highlight the problem of idolatry through biblical authority. Originally written in Greek and possibly at the turn of the first century CE, the Book of Wisdom encouraged its readers to maintain Jewish monotheism, specifically in the context of Greek and Egyptian ritual practices. Themes that appeared in later Christian sources, such as Justin Martyr, Augustin of Hippo, and Thomas Aquinas, affirmed analogous premises: the Christian god was not a material object. It offered the same message in the hands of the Florentine Codex team. “Miserable are they the great dead,” the team copied, “who worship as god the carved stone, the carved wood, the divine impersonators [teixiptla], the substitutes, things made from gold and metal” (Ointlaueliltic, in iehoanti, in tlacamjccapupul, in qujmoteutique, in tetlaxintli, in quaujtl tlaxintli, in teixiptla, in tepatillo: in teucujtlatl, yn anoço tepuztli, ic tlachiuhtli) [Wisdom 13.10] (Sahagún 1970, p. 57). In the same way that the author of the Book of Wisdom sought to correct deviancies against monotheism in relation to Greeks and Egyptians, the Florentine Codex team highlighted the importance of worshipping an eternal god—a god without beginning or end—compared with a god made from human hands.

Not only did the team introduce scripture as an authoritative text, but also lexical entries that shaped the discourse of idolatry and false religion in Nahuatl. These entries became more pronounced once the team began to translate Chapter 14 from the Book of Wisdom, which explained why the worship of natural elements and objects were problematic. As I noted in the conversation that Cortés and Moteuczoma must have had, idolatry as a concept exists only in religious traditions that hold to the worship of one god. “Heresy is an impossibility,” David Tavárez notes as it applies to Mesoamerican religions (Tavárez 2011, p. 10). Idolatry and its derivative actions are not original to Mesoamerica, because they had many gods and those gods were manifestations of natural elements, elaborated in sculpture and perishable materials. To explain why representations of gods through raw materials were false, ecclesiastics introduced neologisms and repurposed existing terms that could acquire Christian meaning. In Book 1 of the Florentine Codex, the vocabulary of idolatry was “darkness” (tlaiooalli), “confusion” (netlapololtiliztli), “unbelief” (atlaneltoquiliztli), and of course, “idolatry” (tlateotoquiliztli). Some terms were original, such as “darkness” and “confusion”, but others had to be created, such as “(un)belief” and “idolatry”. Neologisms fit into the existing agglutinative structure of Nahuatl, whereby morphemes can be compounded and incorporated into nouns and verbs, respectively, to create new meanings and concepts. The Nahuatl term for idolatry (Table 1) was created from the noun “god” (teotl) and the verb “to follow without reason” (toca), after the gloss from the Nahua Jesuit grammarian, Horacio Carochi (Carochi 2001, p. 298) (the creation of the Nahuatl word for “unbelief” (atlaneltoquiliztli) was similar, but the term widened the semantic range of the verbal root toca, to mean “to follow” with no moral qualification and it introduced the emphatic “truly” or “often” (nel) to emphasize the action of the verb). The idea here was that idolaters followed a divine entity, certainly not the Christian one, without reason or grounds to stand on. The Florentine Codex team switched between using the Nahuatl teotl and the untranslated loanword dios to make semantic distinctions between the false Nahua gods and the true Christian divinity. Teotl and dios were different in pronunciation and alphabetic representation, and for that very reason, not the same.

Table 1.

Parsing of tlateotoquiliztli.

Once again, the problem of universals helps to illuminate how Sahagún may have approached his alignment of these two entries. Thomas Aquinas and Duns Scotus questioned whether the Christian god could be known through other things, particularly sensible creatures. In his Contra Gentiles (1260s), Aquinas concluded that although “God gave things all their perfections and thereby is both like and unlike them all”, which meant “the creature has what belongs to God” by virtue of being created, the reverse was not true, that “God is like a creature” (Aquinas 1955, vol. 1, p. 29). In the Summa Theologiæ, Aquinas asserted that “from the knowledge of sensible things the whole power of God cannot be known; nor therefore can his essence be seen” (Aquinas 1947, Part 1, Q. 12, Art. 12). Aquinas’s main concern was that people would confuse the Christian god, specifically what was unlike the divine entity, through their perception of other things. Duns Scotus disagreed. “Every such object is something sensible,” he wrote in his Ordinatio, “therefore God cannot be naturally known save through species of sensible things…For I say that God is like this [e.g., stone], and so I have of God a concept of being; but this could not be done unless the concept of being were univocal to God and stone, for otherwise I could not attribute to God the concept of being that the species of stone causes in me” (Duns Scotus 2016, Dist. 3, Q. 1–2, Art. 12). What Duns Scotus contributed to the argument is “univocality”, meaning that concepts with the same meaning could be applied to the Christian god and creatures (Williams 2019). This was a bold statement, but it used Aquinas’s own argument against him. Duns Scotus claimed that if we can only know god via other things, even if these things are unlike the Christian god, these sensible things are the only referents people have to understand the divine entity. To this end, some friars in the Americas whole-heartedly conflated indigenous and Christian concepts. The Theology Indorum, for example, used the K’iche’ Maya “creator molder” (tz’aqol b’tiol) to talk about the Christian god, and something similar was evident in early attempts to pair epithets of Nahua deities such as “possessor of near and far” (tloque nahuaque) and “giver of life” (ipalnemohuani). Sahagún was not as bold in Book 1.

Although Sahagún may have used the Nahua epithet “possessor of near and far” (tloque nahuaque) in his dialogical Christian doctrine (Sahagún 1986), the comparisons that the team undertook in their treatment of idolatry was teolt and dios. I noted earlier that the Florentine Codex team did use teotl sparingly in Book 1 and its Appendix (Sahagún 1970, pp. 61, 63, 69), but the context makes it clear that the subject of veneration is the Christian god. Christensen (2013, pp. 35–36) found that if teotl was used, it was always paired with dios and the phrase “the one” (ce nelli) as qualifications to the Nahua concept. Tavárez (2000) also shows that across Christian doctrines and confession manuals, the loanword dios was preferred over a Nahuatl translation or epithet. Dios explicitly differentiated commonalities and universal associations between Nahua deities and the Christian god. God may have been a universal being, but using terms that could potentially relate idolatry or confuse Nahua neophytes was a dangerous move.

If idolatry meant that people followed a false deity without reason, the Florentine Codex team found perfect examples in the Book of Wisdom. “The wood is good, it is needed, it is god’s creation [dios],” they affirmed, “but the wood which is used [in] idolatry is well detested” (Jn quaujtl ca qualli, ca monequj, ca itlachioaltzin in dios…Auh in quaujtl ynjc muchioa, in tlateutoqujliztli, vel telchioalonj) [Wisdom 14.7–8] (Sahagún 1970, p. 58). Not only the wood, the Book of Wisdom concluded, but also the wood-carver was equally at fault for making unnecessary objects that led people into “confusion” (tetlapololti). “Like this people in this earth were confused,” the team continued to translate, “the precious name, god [teotl], only the well honored god [dios] is the owner, thus they gave the name to divinity impersonators of stone and wood” (Jhujn yn omotlapololtique, in tlalticpac tlaca…in tlaçotli tocaitl in teutl, in çan vel izeltzin yaxcatzin in dios, ynic oqujntocaiotique in teixiptla, in quaujtl) [Wisdom 14. 21, paraphrase] (Sahagún 1970, p. 59). To help reinforce their point, the Florentine Codex team included an enigmatic illustration along with their translation (Book 1, fol. 26r) that portrayed the process of Nahua carvers chopping down a tree, giving it human form, dressing it in divinity regalia, and presenting it food offerings. While they used teotl and dios to convey an ontological distinction, the illustration showed the state of idolaters’ error: they used wood to falsely worship something that only a god without beginning or end deserved. The Book of Wisdom gave the Florentine Codex team enough reason to reinforce their preconceived notions about idolatry in the central Mexican context. “And now so that their hearts will be well watched [pachihuiz],” they wrote, “[because] they are not strong of heart, it is still necessary also that I declare the word of god [teotlahtolli] written above so that all people know it” (Auh yn axcan ynjc vel iniollo pachiuiz, yn amo cenca chicaoac in imjx, yn iniollo, oc monequj oc achi njmelaoaz, in teutlatolli, in tlacpac omjcuilo ynjc muchi tlacatl qujmatiz) (Sahagún 1970, p. 63). The first person singular (i.e., I declare) is curious, and it may refer to Sahagún’s dictation or the opportunity to use the text in a liturgical context, but literarily, it transitions the text from the translation of the Vulgate to its interpretation.

Using “the word of god”, the authors entered into a hermeneutical deliberation with Revelation (Sahagún 1970, p. 68), Leviticus (Sahagún 1970, p. 68), and the Book of Psalms (Sahagún 1970, p. 70), showing how idolatry was treated in biblical texts and how it would be treated for Christians in central Mexico. These were cited systematically in both the Castilian Spanish and Nahuatl columns of their refutation. Returning to Chapter 14 of the Book of Wisdom, the team unraveled its meaning in relation to the Nahua gods. “The blind idolaters,” they contended, “gave the name to stone, saying, ‘it is our god,’ to the wood, saying, ‘it is our god, our ruler’…the revered name of god [dios] in whom there is life, they gave to men and women, mortals who are rotten” (Auh yn jxpopoiome, in tlateutocanjme, qujtocaiotique, in tetl, qujlhujque: ca tinoteouh, qujlhujque, in quaujtl, ca tinoteouh, tinotlatocauh…yn jtocatzin dios ipalnemoanj, intech oqujtlalique, yn oqujchti, yn cioa: in miqujnj, in palanjnj) (Sahagún 1970, p. 69). Who was one of these gods, rulers, and mortals usurping the divinity of the Christian god? Quetzalcoatl, a compound noun that literally means “feathered serpent”. Although not explained in the description of Book 1, Quetzalcoatl was not only a god associated with wind. More than that, he was an old hero-deity from the Early Postclassic city-state of Tollan (900–1200 CE) in central Mexico. Tenochtitlan, like other neighboring city-states, was infatuated with Tollan culture. Quetzalcoatl became one of the many representatives of Tenochtitlan’s own ancient civilizations and reinforced their sense of prestige and cultured lineage. “They the old ones believed in Quetzalcoatl, who was a ruler of Tollan,” the Florentine Codex team attested, “He was a common man, he was a mortal. He died, his flesh became rotten. He was no god [teotl]” (Jn iehoantin in veuetque, oqujteutocaque in quetzalcoatl, in tollan tlatoanj catca… Jnin ca maceoalli, ca mjqujni, ca omic, ca opalan yn jnacaio, ca amo teutl” (Sahagún 1970, p. 69). The team admitted that the ruler Quetzalcoatl lived a good life (yecnemiliz), but his works were done with the commands of the devil (tlacatecolotlatoltica) (texts vary between using the Nahuatl tlacatecolotl, a repurposed Nahuatl term that means, “man-owl”, a type of ritual specialist who transformed into animals or things and the untranslated loanword, diablo). “His soul [anima] our lord god [dios] sentenced and threw to the land of the dead,” the team concluded, “There he is. Always it will suffer in flames” (auh yn janjma, oqujmotlatzontequjlili yn totecujo dios, mjctlan, qujmotlaxili, vmpa ca, cemjcac tleco tlaihiiouiz) (Sahagún 1970, p. 69).

The Florentine Codex team’s exposition of idolatry highlights their mastery of scripture, their ability to incorporate existing concepts such as “darkness” (tlaiooalli), and “confusion” (netlapololtiliztli), but also create new ones such as “unbelief” (atlaneltoquiliztli) and “idolatry” (tlateotoquiliztli). One of the things that it is critical to highlight is that the refutation of the Nahua gods lived in both the Castilian and Nahuatl columns of the Florentine Codex. While this section of Book 1 points to Sahagún’s overall goal to create a work that was similar, if not with the same intentions, as Augustine’s City of God, the Nahua historians likely shared the same concern. In the Florentine Codex, we typically find pejorative qualifications to Nahua ritual in the Castilian Spanish columns, but Book 1 is different in that regard. The question of meaning between teotl and dios is a typical trope in the problem of universals and the team highlighted their approach to meaning and translation. Quetzalcoatl, or any of the other gods presented in Book 1, were not arbitrary representations of the Christian god’s reality, and little to no attempt was made to create univocal or analogical connections between them. The Florentine Codex team considered them devilish entities that led people astray.

3.3. Book 1: The Confession

While the confession that ends Book 1 does not reiterate any information from the rest of the Book, it did hope to stimulate local officials and Christian authorities who heard it. The confession did not follow other liturgical Franciscan variations. It was not a questionnaire, like we find in Alonso de Molina’s brief and major confession manuals (Molina 1565a, 1565b, 1577, 1578). Neither did it parallel the general confession in the Códice Franciscano from the 1570s (García Icazbalceta 1889), a liturgical manual for Franciscan ecclesiastical ritual formation in central Mexico. It is a confession of Nahua Christian tropes. “Alas, much [does] my heart cry, my tears greatly settle on my face,” the confession began, “my tears are like hailstones when it snows, as soon as I remember much the many things, the falsehood [iztlacatlahtolli], as people here of New Spain were led to falsehood [iztlacahuiloque]” (Iioiave, cenca chocan niollo, vel njxaio njxtlan moteteca: iuhqujn pixavi njxaio, ynjc niqujlnamjquj, ca cenca mjec tlamantli, iztlacatlatolli, ynjc iztlacaviloque, in nican nueua españa tlaca) (Sahagún 1970, p. 76). At fault for fabricating false things was none other than Satan, the antagonist in the Christian tradition. “Because greatly he [i.e., Satan] voluntarily does it with all his power, walking to bring us down to our end,” the Florentine Codex team continued, “our instrument to light the fire under, our damnation to us the children of Adam. Thus it is he [who] had put [us] through falsehood” (iehica vel yiollocopa, vel ixqujch ytlapal qujchioa, ynic qujtemotinemj, yn tipilhoã Adan: injn ca teiztlacaujliztica, teca) (Sahagún 1970, p. 76). In this instance, the figure Satan was paired with an unrestrained force known as tzitzimitl, a cohort of Nahua deities that appear during cosmological events such as eclipses to unleash disorder on people (Molina 1571; Tavárez 2011, p. 54). It is worth highlighting the decision to use tzitzimitl and not a loan word to refer to Satan. Throughout the refutation of the Nahua gods, the Florentine Codex team either used teotl pejoratively, the repurposed figure of the “man-owl” (tlacatecolotl), or the loanword “devil” (diablo) to demonstrate that Nahua gods were no gods. However, here the team found a universal concept. The Nahua forces that brought chaos to the land were not unlike the chaos that Satan brought to the lives of Christian people in Europe.

4. Conclusions

Assessing the overall argument of the Florentine Codex Book 1 in its entirety, readers were meant to travel from a description of the Nahua gods, to their refutation, and arrive at accepting they were ultimately false. In the team’s treatment of idolatry, the problem of universals comes to bear as they decided how to present the Nahua gods (whether commonalities existed with other ancient societies) and how to exact their differences with the Christian god’s divine reality (whether such realities had unique individual forms). The Florentine Codex team treated universal concepts and their singularities as best they could and with the techniques they perceived would work best. These included ontological differences between teotl and dios, analogies of Nahua gods with Roman gods, translating and interpreting biblical texts, creating neologisms by taking advantage of agglutination, and repurposing existing terminology to convey Christian meaning. Some techniques were superficial, others were awkward, and others clearly imparted exclusive monotheism. Sahagún’s training at the University of Salamanca and the Friary of San Francisco at Zaragoza in Aragon shaped his view of the Nahua world, as much as Antonio Valeriano, Martín Jacobita, Pedro de San Benaventura, and Alonso Vegrano shaped him.

When Cortés’s exhorted Moteuczoma and the ritual specialists at El Templo Mayor about the exclusive worship of one god, the Christian one, it was possibly the first time that Nahuas heard of idolatry. Later, Sahagún would notice that it was not enough to topple effigies from their chairs, but to ascertain how Nahua ideas and ritual practices affected the Christian religion. Sahagún was concerned with meaning and how best to know if meaning behind Nahua-Christian concepts carried idolatrous intentions. In the prologues to the Florentine Codex Book 10 on people and their vices and Book 11 on earthly things, Sahagún acknowledged that Nahua taxonomies and classifications were different because of the language that people spoke (Sahagún 1988b, vol. 2, pp. 583, 677). “And to give major opportunity and help to the preachers of this new church, in this volume I have treated the moral virtues, in accordance with the intelligence, practice, and language that this same people [i.e., Nahuas] have…I do not carry in this treatise the order that other writers have carried in treating this matter” (Y para dar mayor oportunidad y ayuda a los predicadores desta nueva iglesia, en este volume he tractado de las virtudes morales, según la inteligencia y práctica y lenguaje que la misma gente tiene dellas. No llevo en este tractado la orden que otros escriptores han llevado en tartar esta materia) (Sahagún 1988b, vol. 2, p. 583). The Nahuatl language shaped the universal concepts of the Nahua. That Sahagún was keenly aware of these subtleties shows that he saw the particularities that might have shaped the Christian religion, and by defining and explaining Nahua rituals, a better Christian instruction would come to light. Centering the Florentine Codex team in the early modern debates about universals underlines the multifaceted, intellectual environment that gave life to Nahua Christianities in the sixteenth century.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Aquinas, Thomas. 1947. Summa Theologiae. Translated by Fathers of the English Dominican Province. New York: Benzinger Brothers. [Google Scholar]

- Aquinas, Thomas. 1955. Contra Gentiles. Edited by Josepth Kenny. Translated by Anton C. Pegis. New York: Hanover House. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, Jan. 2010. The Price of Monotheism. Translated by Robert Savage. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bassett, Molly. 2015. The Fate of Earthly Things: Aztec Gods and God-Bodies. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bassett, Molly. 2019. Bundling Natural History: Tlaquimilolli, Folk Biology, and Book 11. In The Florentine Codex: An Encyclopedia of the Nahua World in Sixteenth-Century Mexico. Edited by Jeanettte Favrot Peterson and Kevin Terraciano. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 139–51. [Google Scholar]

- Bellah, Robert N. 2011. Religion in Human Evolution: From the Paleolithic to the Axial Age. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berdan, Frances F., and Patricia Rieff Anawalt. 1997. The Essential Codex Mendoza. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boone, Elizabeth. 2019. Fashioning Conceptual Categories in the Florentine Codex: Old-World and Indigenous Foundations for the Rulers and the Gods. In The Florentine Codex: An Encyclopedia of the Nahua World in Sixteenth-Century Mexico. Edited by Jeanettte Favrot Peterson and Kevin Terraciano. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 95–109. [Google Scholar]