Development and Validation of a Faith Scale for Young Children

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What are the factors of a faith scale for young children?

- What is the validity of the faith scale for young children?

- What is the reliability of the faith scale for young children?

2. Results

2.1. Data Screening

2.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

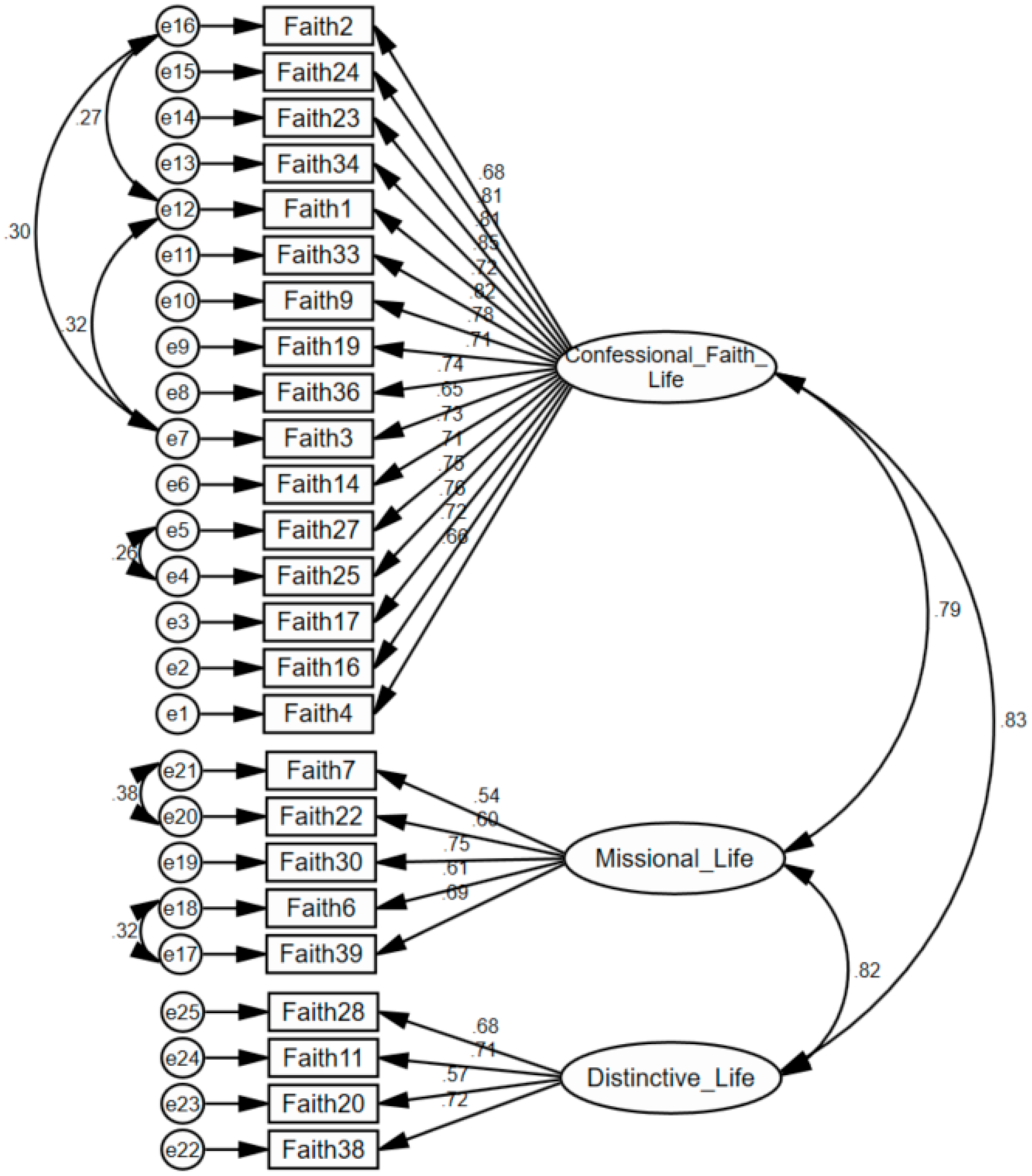

2.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

2.3.1. Model Fit

2.3.2. Validity Test

2.4. Reliability Test

2.5. Final Version

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Research Subject

4.2. Research Precedures

4.2.1. Factor and Item Generation

4.2.2. Content Validity Test

4.2.3. Pilot Study

4.2.4. Main Study

4.2.5. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anthony, Michael J. 2006. Putting children’s spirituality in perspective. In Perspectives on Children’s Spiritual Formation. Edited by Michael J. Anthony. Nashville: B & H Academic, pp. 1–43. ISBN 139780805427295. [Google Scholar]

- Averbeck, Richard. 2008. Worship and spiritual formation. In Foundations of Spiritual Formation: A Community Approach to Becoming Like Christ. Edited by Paul Pettit. Grand Rapids: Kregel Academic, pp. 51–69. ISBN 9780825434693. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, Byung-Ryeol. 2017. AMOS 24 Structural Modeling. Seoul: Cheongnam, pp. 150–52. ISBN 9788959725526. [Google Scholar]

- Beers, V. Gilbert. 1986. Teaching theological concepts to children. In Childhood Education in the Church. Edited by Robert E. Clark, Joanne Brubaker and Roy B. Zuck. Chicago: Moody Press, pp. 363–79. ISBN 9780802412515. [Google Scholar]

- Boa, Kenneth. 2020. Conformed to His Image: Biblical, Practical Approaches to Spiritual Formation, Revised ed. Grand Rapids: Zondervan Academic, pp. 15–17. ISBN 031023848X. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, Richard H. 1995. On the use of a pilot sample for sample size determination. Statistics in Medicine 14: 1933–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Eun-Ha. 2012. Effects of Spiritual-Oriented Peace Education on the Depression and Self-Resilience of Young Children. Master’s Thesis, University of Ulsan, Ulsan, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Chul-Ho. 2016a. Structural Equation Modeling Using SPSS/AMOS. Seoul: Cheong Ram, pp. 181–84. ISBN 9788959724581. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Hye-Jeong. 2016b. The creation world view and practice of creativity in early child education. Christian Education & Information Technology 49: 233–54. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Young-Joo, and Jin-Joo Han. 2011. Exploring the Meaning of Spiritual Education for Young Children: Focused on Frobel and Montessori Pedagogy. Paper presented at the Korean Society for Early Childhood Education Conference, Kunkuk University Concert Hall, Seoul, Korea, March 26. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, Hee-Jung, and Yoon Jeong. 2014. The effects of the Alta Vista program based on a Christian worldview on young children’s God concept. Faith & Scholarship 19: 237–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkind, David. 1971. Cognitive growth cycles in mental development. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation 19: 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, John W. 2004. Feeling good, living life: A spiritual health measure for young children. Journal of Beliefs & Values 25: 307–15. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, John W. 2015. God counts for children’s spiritual well-being. International Journal of Children’s Spirituality 20: 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, James. 1981. Stages of Faith: The Psychology of Human Development and the Quest for Meaning. New York: HaperCollins Publishers, pp. 123–73. ISBN 97880060628666. [Google Scholar]

- Go, Eun-Nim. 2008. The Development of a Church Education Program Model Based on the Bible for Preschool-Aged Children. Ph.D. dissertation, Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Go, Eun-Nim. 2010. A development of a Christian church education program for young children. The Journal of Korea Open Association for Early Childhood Education 15: 189–212. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, Ronald. 1965. Readiness for Religion: A Basis for Developmental Religious Education. London: Routledge, pp. 77–223. ISBN 9780429056116. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, Ronald. 1984. Religious Thinking from Childhood to Adolescence. New York: Seabury Press, pp. 34–67, ASIN: B01NBQ1NL3. [Google Scholar]

- Heo, Kay-Heoung. 2017. Implementation strategies of church education to teach young Christians leading the era of the fourth industrial revolution. Faith & Scholarship 22: 227–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howden, Judy W. 1992. Development and Psychometric Characteristics of the Spirituality Assessment Scale. Ph.D. dissertation, Texas Woman’s University, Denton, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, Hae-Ik, Yeon-Sook Song, Hye-Jin Choi, and Won-Kyung Son. 2017. Easy-Learning SPSS Data Analysis. Go-yang, Kyoung-ki: Knowledge Community, p. 419. ISBN 9788963528991. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, Hwa-sun. 2002. A study on the development of Children’s faith. Journal of Christian Education in Korea 8: 155–85. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, Hwa-Sun. 2011. Children’s Faith Education Guide. Seoul: Bread of Life, p. 119. ISBN 9788988618578. [Google Scholar]

- Jeoung, Hee-Young, and Myeong-Sun Jin. 2017. The effects of utilizing the textbook for children’s faith development at preschool institution on preschool children’s personality development. Christian Education & Information Technology 55: 183–212. [Google Scholar]

- Joo, Yun-Soo. 2018. Christian education in infancy and early childhood for self-regulation and moral development. Christian Education & Information Technology 58: 199–231. [Google Scholar]

- Joo, Yun-Soo. 2019. Christian education and formation of spirituality in infancy and early Childhood. Journal of Christian Education in Korea 58: 243–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Dae-Hyun. 2010. The concept of Jesus in young children according to parents’ faith and attendance at church. Chongshin Journal 30: 408–29. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Yun, and Hee-Young Jeoung. 2015. A case study on the teacher’s experience in the applying of early childhood education curriculum based on the Christian worldview. Faith & Scholarship 20: 171–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Jamie M. 2010. An understanding of young children’s spirituality and its application to education. Christian Education & Information Technology 27: 383–403. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Kook-Hwan. 2006. Religious Development and Christian Education. Seoul: Korean Christian Education Association, pp. 29–30. ISBN 9788973690442. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Sung-Won. 2008. The children’s God concept questionnaire. Journal of Christian Education & Information Technology 13: 51–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Seon-A. 2010. Parents education for children connecting church with family. Christian and Cultural Studies 15: 223–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Mi-Gyeong. 2011a. The Effect of Spirituality-Oriented Gratitude Program on a Child’s Violent Behavior and Self-Control. Master’s Thesis, University of Ulsan, Ulsan, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Min-Seo. 2011b. The Effect of Spirituality-oriented Peace Program Using Picture Books on a Child’s Pro-social Behavior and Self-Control. Master’s Thesis, University of Ulsan, Ulsan, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Sung-Won. 2012. A discussion on the Christian education practice at early childhood institutions. Faith & Scholarship 17: 67–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Song-Hwa. 2014. The Effect of Montessori Spirituality Activities on Preschooler’s Perceived Competence, Spiritual Intelligence, and Self-Regulation. Ph.D. dissertation, Catholic University, Daegu, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Soon-Whan. 2015. A study on worship for infancy and early childhood. The Gospel and Praxis 34: 51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Sung-Won. 2020a. Perceptions of faith formation of young children: An exploratory qualitative study of church ministers. Theology and Praxis 68: 411–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Sung-Won. 2020b. A qualitative study of the young children’s perception of faith. Journal of Christian Education in Korea 63: 283–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Nam-Im, and Kay-heoung Heo. 2017. Applying psychology while teaching the Bible: Based on application of motivation theory. Faith & Scholarship 22: 31–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Eun-Yi. 2006. A Study of Co-Relations between Emotional Intelligence and Spiritual Intelligence for Children. Master’s Thesis, Jeju National University, Jeju, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Kweon, Mee-Ryang, Yeon-Hee Ha, and Young-Hee Kye. 2018. The meaning and direction of Christian early childhood education in the United States and South Korea. Faith & Scholarship 23: 5–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, Gi-Su. 2013. A Study on Measurement and Development of the Christian Concept for Young Children. Ph.D. dissertation, Paichai University, Daejeon, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Hye-Sang. 1993. A Study on the Development of a Model for Christian Early Childhood Education. Ph.D. dissertation, Seoul Women’s University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Hyai-Jung. 2002. A Study of Spirituality and Job Performance among the Workers in Catholic Social Welfare Organizations. Master’s Thesis, Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Young-Joo. 2007. The Influence of Parents’ God Concept, Religious Life, and Child-Rearing Attitude on Children’s God Concept. Ph.D. dissertation, Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Sung-Bok. 2011. A study concerning family worship in Christian family and children’s God concept. Calvin Forum 31: 259–92. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Sung-Bok. 2017. Early childhood developmental characteristics and faith education. Calvin Forum 37: 351–80. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Hae-Jung, and Mi-Kyung Kim. 2010. The effects of famous arts appreciation based on creation factors to faith development of children. Faith & Scholarship 15: 153–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Kyung-Woo, and Hye-Sang Lee. 1988. The Theory and Practice of Christian Education for Young Child. Seoul: Chang-Ji-Sa, pp. 150–56. ISBN 9788942600076. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Ji-Young, and Yu-Na Lee. 2016. The effects of sensory Bible play activities through Bible storybook on the Christian concepts and spiritual well-being for young children. Journal of Early Childhood Education 36: 343–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Da-Kyung, Young-Joo Kim, and Yoon-Kyung Kim. 2013. Effects of Spiritual-Oriented Gratitude Program on the Depression and Self-resilience of Young Children. Paper presented at the Spring Conference of the Korean Family Management Association, Seoul, Korea, May 12. [Google Scholar]

- LifeWay. n.d. Levels of Biblical Learning. Available online: https://www.lifeway.com/en/special-emphasis/levels-of-biblical-learning/older-preschool?intcmp=LOBL-OlderPreschool-DATE (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Lunn, Jenny. 2009. The role of religion, spirituality and faith in development: A critical theory approach. Third World Quarterly 30: 937–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Eun-Hee, and Nam-Im Kim. 2020. Web-based child-parent integrated worship practice and strategies in COVID 19 era: Focusing on Christian social emotional character developing program for young children. Christian Education & Information Technology 66: 197–220. [Google Scholar]

- Min, Si-In, and Mi-Suk Kim. 2011. Ethnographic research about Christian young children’s faith life in Korea: Focusing on preschool department worship service and nursery room. Faith & Scholarship 16: 75–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Kelsey, Carlos Gomez-Garibello, Sandra Bosacki, and Victoria Talwar. 2016. Children’s spiritual lives: The development of a children’s spirituality measure. Religions 7: 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradshahi, Michael, Todd W. Hall, David Wang, and Andrea Canada. 2017. The development of the spiritual narrative questionnaire. Journal of Psychology and Christianity 36: 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, Young-Hee, and Mi Jung. 2009. The effects of dramatic activities of the Bible story on young children’s faith and socio-emotional development. The Journal of Humanities 26: 123–49. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, Pok-Ja, and Kyong-Ah Kang. 2000. Spirituality: Concept analysis. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing 30: 1145–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Shin-Kyung. 2010. The significance of spirituality education for early childhood. Theology and Ministry 34: 95–119. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Sun-Hye. 2013. Effects of Montessori Peace Activities on the Improvement of Emotional Intelligence and Spiritual Intelligence of Young Children. Ph.D. dissertation, Daegu Catholic University, Daegu, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Eun-Jeong. 2014. A study on the development of the Gardner’s multiple-intelligences through the integrated learning of music-integrated class: Focusing on the children of church academy. Theology and Mission 44: 217–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Soon-Yong. 2017. The Essence of Worship. Seoul: Agape Books, pp. 26–28. ISBN 9788997713967. [Google Scholar]

- Paul-Victor, Chitra G, and Judith V. Treschuk. 2020. Critical literature review on the definition clarity of the concept of faith, religions, and spirituality. Journal of Holistic Nursing 38: 107–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, Seung-Hee. 2011. The Effect of Spirituality-oriented Music Activities on a Child’s Aggressiveness and Self-regulation. Master’s Thesis, Ulsan University, Ulsan, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Self, Margaret M. 1986. Understanding fours and fives. In Childhood Education in the Church. Edited by Robert E. Clark, Joanne Brubaker and Roy B. Zuck. Chicago: Moody Press, pp. 109–24. ISBN 9780802412515. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, Soon-Tae. 2013. A study on development of Preschooler’s leadership: Implementation and evaluation of Jochebed early childhood education and Jewish education. Early Childhood Education Research & Review 17: 119–42. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Ji-Youn. 2011. Early childhood “creation creed” education through nature: Focus on Ellen G. White’s writings. Scholarship and Christian Worldview 2: 113–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sifers, Sarah K., Jared S. Warren, and Yo Jackson. 2012. Measuring spirituality in children. Journal of Psychology and Christianity 31: 209–18. [Google Scholar]

- Son, Eun-Hye, Young-Joo Kim, and Yeon-Sook Song. 2010. The effect of the program for sensory activities devised to encourage spirituality on young children’s self-efficacy. Journal of Korean Child Care and Education 6: 117–33. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Young-Ran. 2005. Development and Verification of Effect of The Biblical Story Activity Program to Facilitate Young Children’s Faith and Prosocial Behaviors. Doctoral Dissertation, Seoul Women’s University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Se-Ra. 2011. A study on praise activities of early childhood using Jaques-Dalcroze method: Focusing on 3–6 years old. Korean Dalcroze Study 2: 51–72. [Google Scholar]

- Stoyles, Gerard, Bonnie Stanford, Peter Caputi, Alysha-Leigh Keating, and Brendan Hyde. 2012. A measure of spiritual sensitivity for children. International Journal of Children’s Spirituality 17: 203–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toon, Peter. 1989. What Is Spirituality and Is It for Me? London: Daybreak, p. 15. ISBN 9780232518047. [Google Scholar]

- Tratner, Adam E., Yael Sela, Guilherme S. Lopes, Alyse D. Ehrke, Viviana A. Weekes-Shackelford, and Todd K. Shackelford. 2017a. Development and initial psychometric assessment of the childhood religious experience inventory: Primary caregiver. Personality and Individual Differences 114: 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tratner, Adam E., Yael Sela, Guilherme S. Lopes, Alyse D. Ehrke, Viviana A. Weekes-Shackelford, and Todd K. Shackelford. 2017b. Individual differences in childhood religious experiences with peers. Personality and Individual Differences 119: 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trent, John, Rick Osborne, and Kurt Bruner. 2000. Parent’s Guide to the Spiritual Growth of Children: Helping Your Child Develop a Personal Faith. Wheaton: Tyndale House Publishers, pp. 115–20. ISBN 9781561797912. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Valerie A. 1991. Infants and Preschoolers. In Christian Education: Foundations for the Future. Edited by Robert E. Clark, Lin Johnson and Allyn K. Sloat. Chicago: Moody Press, pp. 221–32. ISBN 0802416470. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Kum-Hee. 2008. Young children’s understanding the God and the direction of Christian early childhood education. Journal of Presbyterian Seminary 32: 111–53. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Kum-Hee. 2013. The orientation of the children’s spiritual education through the perspective of the relationship of children’ spirituality and emotion and sense. Journal of Christian Education in Korea 34: 31–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeon, Yo-Han. 2004. Faith development and spirituality. University and Mission 6: 203–44. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, Hee-Jin, and Hee-Young Jeoung. 2015. The analysis of Christian early childhood home-schooling curriculum: Bob Jones, Alpha Omega, and Christian liberty. Journal of Christian Education in Korea 44: 307–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Hae-Yong. 2009. Spirituality and spiritual theology. Korea Presbyterian Journal of Theology 36: 304–31. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Jong-Pil. 2012. Concepts and Understanding of Structural Equation Model. Seoul: Hannarae, pp. 164–66. ISBN 9788955661248. [Google Scholar]

| Developer (Year), Scale Name | Factor, Item | Characteristic | Improvement | Follow-Up Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Song (2005), Religious Development Interview Tool | - Good image - Belief in Jesus and resurrection - Heaven - Prayer - Forgiveness -28 questions | - Open-ended questions based on Fowler (1981) and Goldman (1984) - No response/don’t know 0 point; preoperational thinking 1 point; concrete operational thinking 2 points | - Logical and theological soundness - Subjectivity of scoring criteria | - Oh and Jung (2009) - Lee and Kim (2010) |

| Howden (1992), Spirituality Assessment Scale | - Energy in life, - Relationships with others and objects - Integrated energy - Positive perspective on the future -28 items | - 6-point Likert scale - 40–60 years olds | - Use for young children by translating and modifying the scale for agesd 40 to 60 -No questions about faith or God -Inappropriateness of the factor-question | - Oh and Kang (2000) - Lee (2002) - Ko (2006) - Park (2013) - Kim (2014) |

| Fisher (2004), Feeling Good Living Life | - Self-concern - Family - Environment - Relationship with God - 4 items for each factor | - Ssubjects: 2018 children aged 5–12 - 5-point Likert scale | - 75% of the questions are about family, environment, self-emotions | - Lee and Lee (2016) |

| Stoyles et al. (2012), The Spiritual Sensitivity Scale for Children | - Outward focus - Inward reflective focus -23 items | - 4-point Likert scale | - No question related to faith or God. | |

| Moore et al. (2016), Children’s Spirituality Measure | - Comfort - Omnipresence - Duality - 27 items | - Subject: Children from various religious backgrounds - Exploratory factor analysis only - Measured by parents | ||

| Tratner et al. (2017a), Childhood Religious Experience Inventory | - Assurance - Disapproval and punishment - Social involvement - Encouraged skepticism - 16 items | - Subject: 18–34 years old | - Measuring parental influence, not child’s spirituality - Adult’s recalling as a child - Exploratory factor analysis only |

| Items | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Communality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1: Confessional Faith Life | ||||

| 2. I feel that God loves me. | 0.762 | 0.253 | -0.034 | 0.646 |

| 24. God is precious to me. | 0.753 | 0.222 | 0.249 | 0.678 |

| 23. I believe that God is alive. | 0.753 | 0.246 | 0.229 | 0.674 |

| 34. I am glad I believe in Jesus. | 0.745 | 0.236 | 0.341 | 0.726 |

| 1. God knows my thoughts and feelings. | 0.739 | 0.173 | 0.184 | 0.611 |

| 33. I know that the Bible is the word of God. | 0.738 | 0.155 | 0.366 | 0.703 |

| 9. I believe that Jesus died on the cross to forgive my sins. | 0.708 | 0.230 | 0.256 | 0.620 |

| 19. I, who believe in Jesus, will go to heaven. | 0.689 | 0.278 | 0.116 | 0.566 |

| 36. God wants everyone to know and worship Him. | 0.677 | 0.135 | 0.333 | 0.588 |

| 3. I want to be a proud child to God. | 0.665 | 0.125 | 0.222 | 0.508 |

| 14. I think that God is the one who gives sunshine and rain. | 0.652 | 0.162 | 0.331 | 0.561 |

| 27. I am a precious person, created by God. | 0.642 | 0.135 | 0.347 | 0.551 |

| 25. God created me through my parents. | 0.641 | 0.300 | 0.298 | 0.589 |

| 17. I am grateful to see the world God has created. | 0.629 | 0.232 | 0.372 | 0.588 |

| 16. I am happy when I think about God. | 0.574 | 0.300 | 0.372 | 0.557 |

| 4. God helps me when I feel distressed or sad. | 0.544 | 0.321 | 0.284 | 0.480 |

| Factor 2: Missional Life | ||||

| 7. I can tell anyone in the kindergarten or childcare center I believe in God. | 0.085 | 0.824 | 0.097 | 0.695 |

| 22. I tell my friends about Jesus. | 0.166 | 0.747 | 0.175 | 0.616 |

| 30. I think and talk about God. | 0.332 | 0.663 | 0.234 | 0.604 |

| 6. I like going to church and I wait for it. | 0.353 | 0.547 | 0.158 | 0.448 |

| 39. I like to worship. | 0.398 | 0.477 | 0.337 | 0.449 |

| Factor 3: Distinctive Life | ||||

| 28. I feel sorry toward God when I do something bad. | 0.351 | 0.052 | 0.742 | 0.677 |

| 11. I ask God for forgiveness when I do something wrong. | 0.244 | 0.229 | 0.742 | 0.662 |

| 20. I, a child of God, do not lie. | 0.201 | 0.318 | 0.563 | 0.458 |

| 38. I pray to God when I have difficulties. | 0.329 | 0.382 | 0.540 | 0.546 |

| % of Variance | 33.038 | 13.330 | 13.028 | |

| Eigenvalues | 12.214 | 1.592 | 1.043 | |

| Factor | Item | Standardized Regression Weight | t-Value | CR (Construct Reliability) | AVE (Averaged Variance Extracted) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confessional Faith Life | Faith 4 | 0.657 | Fix | 0.993 | 0.893 |

| Faith 6 | 0.72 | 13.556 | |||

| Faith 17 | 0.757 | 14.139 | |||

| Faith 25 | 0.754 | 14.102 | |||

| Faith 27 | 0.711 | 13.413 | |||

| Faith 14 | 0.731 | 13.732 | |||

| Faith 3 | 0.646 | 12.328 | |||

| Faith 36 | 0.74 | 13.882 | |||

| Faith 19 | 0.713 | 13.442 | |||

| Faith 9 | 0.78 | 14.513 | |||

| Faith 33 | 0.825 | 15.188 | |||

| Faith 1 | 0.72 | 13.554 | |||

| Faith 34 | 0.849 | 15.549 | |||

| Faith 23 | 0.813 | 15.018 | |||

| Faith 24 | 0.807 | 14.915 | |||

| Faith 2 | 0.676 | 12.831 | |||

| Missional Life | Faith 39 | 0.692 | Fix | 0.963 | 0.84 |

| Faith 6 | 0.606 | 13.404 | |||

| Faith 30 | 0.747 | 12.974 | |||

| Faith 22 | 0.597 | 10.753 | |||

| Faith 7 | 0.536 | 9.717 | |||

| Distinctive Life | Faith 38 | 0.716 | Fix | 0.971 | 0.894 |

| Faith 20 | 0.575 | 10.891 | |||

| Faith 11 | 0.715 | 13.37 | |||

| Faith 28 | 0.68 | 12.778 | |||

| χ2(266) = 814.166, p = 0.000; SRMR = 0.042; GFI = 0.870; | |||||

| CFI = 0.919; TLI = 0.909; RMSEA = 0.069 | |||||

| KERRYPNX | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | 0.893 | |||

| Factor 2 | 0.714 ** | 0.840 | ||

| Factor 3 | 0.638 ** | 0.606 ** | 0.894 | |

| Total | 0.958 ** | 0.830 ** | 0.802 ** |

| Items | M (SD) | Cronbach’s α | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | 1–16 | 4.56 (0.58) | 0.95 |

| Factor 2 | 17–21 | 4.04 (0.79) | 0.77 |

| Factor 3 | 22–25 | 4.06 (0.80) | 0.80 |

| Total | 1–15 | 4.38 (0.59) | 0.95 |

| Factor | Item |

|---|---|

| Confessional Faith Life | 1. I feel that God loves me. 2. God is precious to me. 3. I believe that God is alive. 4. I am glad I believe in Jesus. 5. God knows my thoughts and feelings. 6. I know that the Bible is the word of God. 7. I believe that Jesus died on the cross to forgive my sins. 8. I, who believe in Jesus, will go to heaven. 9. God wants everyone to know and worship Him. 10. I want to be a proud child to God. 11. I think that God is the one who gives sunshine and rain. 12. I am a precious person, created by God. 13. God created me through my parents. 14. I am grateful to see the world God has created. 15. I am happy when I think about God. 16. God helps me when I feel distressed or sad. |

| Missional Life | 17. I can tell anyone in the kindergarten or childcare center I believe in God. 18. I tell my friends about Jesus. 19. I think and talk about God. 20. I like going to church and I wait for it. 21. I like to worship. |

| Distinctive Life | 22. I feel sorry toward God when I do something bad. 23. I ask God for forgiveness when I do something wrong. 24. I, a child of God, do not lie. 25. I pray to God when I have difficulties. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, S. Development and Validation of a Faith Scale for Young Children. Religions 2021, 12, 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12030197

Kim S. Development and Validation of a Faith Scale for Young Children. Religions. 2021; 12(3):197. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12030197

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Sungwon. 2021. "Development and Validation of a Faith Scale for Young Children" Religions 12, no. 3: 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12030197

APA StyleKim, S. (2021). Development and Validation of a Faith Scale for Young Children. Religions, 12(3), 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12030197