Abstract

Based on the findings of mixed-methods research conducted with 279 Muslim prisoners in 10 prisons in England, Switzerland and France, this paper argues that contemporary European prisons are sites of intense religious change, in which many people born outside Islam and many born-Muslims believe in and practise Islam for the first time. In order to map this experience of intense religious change in prison, the paper articulates an original typology of conversion to identify Muslim converts as Switchers and Intensifiers. Both of these types of convert mobilise their Islam to turn to God in acts of repentance for their crime(s), to find a renewed purpose in life and to re-gain psychological balance and inner peace. By contrast, a minority of prisoners are Reducers, whose Islamic faith diminishes in prison. A minority of converts to Islam also persist or become more deeply entrenched in the Islamist Worldview of Us vs. Them. Therefore, while choosing to follow Islam in prison carries with it some criminogenic risk, conversion to Islam is significantly more likely to help than to hinder prisoners’ rehabilitation by enabling them to feel remorse for their crimes, reconnecting them with work and education and encouraging them to find emotionally supportive company.

Keywords:

conversion; switching; intensifying; Islam; Islamism; Muslim; prisoner; prison; rehabilitation; Worldview 1. Introduction

Religion and, in particular, Christian ideals of forgiveness and moral reform, have been seminal to the formation of modern models of incarceration (Ignatieff 1989; Rostaing et al. 2015).

This paper argues that European prisons remain religiously intense environments, characterised, to an unusual degree, by religious exploration and change, as exemplified by a typical sample of 279 Muslim prisoners in five English prisons and, comparatively, four Swiss prisons and one French prison. In order to map the dynamics of this religious conversion and change across our three jurisdictions, we articulate an original typology of conversion that draws both on the existing literature around inter-faith and intra-faith conversion and the idea of Worldviews as integrated ways of being-in and knowing-the-world.

Contrary to the cynical discourses that prisoners primarily choose to follow Islam for perks, protection and privileges, our research shows that Muslim prisoners are more likely to choose to practise Islam for reasons of piety, emotional coping and good company. These largely sincere motives for choosing to follow Islam impact in a significantly positive knock-on way on prisoners’ attitudes to rehabilitation in terms of a reconnection with work, education and an intention to avoid future crime.

2. Muslims in European Prisons

2.1. Mass Muslim Migration Leads to Mass Muslim Imprisonment

Post-colonial, post-World War geo-political and economic circumstances in the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries have seen millions of Muslims come to reside in Europe as citizens for the first time. There are c. 45 million Muslim residents of Europe, excluding Turkey, which represents c. 6% of the European population and c. 4% of the global Muslim population (Pew Research Centre 2017).

This mass Muslim migration has resulted in increasing numbers of registered Muslim in prisons in European jurisdictions. For example, between 2007 and 2019 in England and Wales there was a 47% increase in the Muslim prisoner population: from 8,864 in 2007 to 13,008 in 2019 (Sturge 2019). In England and Wales, for example, Muslims now make-up circa 5% of the general population but make up 17% of the male prison population (HMPPS 2020). Whilst male Muslim prisoners are significantly over-represented in prison, female Muslim prisoners are only marginally so. Female Muslim prisoners account for 6% of the total female prisoner population: of the 3,136 female prisoners in England and Wales, 219 prisoners are Muslim (HMPPS 2020). In short, Muslims, especially Muslim men, are significantly over-represented in European prisons.

2.2. The Over-Representation of Muslims in Prison

It is beyond the remit of this article to explore, in depth, the reasons for the over-representation of Muslims in prison, which are complex and contested. There has been a lot of research to suggest that Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) populations are disproportionately represented at all stages of the criminal justice system (Phillips and Bowling 2017; Irwin-Rogers 2018; Fatsis 2021), which, in turn, indicates that BAME populations are victims of racial and faith-based discrimination in many European jurisdictions. Additionally, it has been noted that Muslims make up a young community and young people (aged 16–30) are over-represented in prison populations (Lammy 2017).

Additionally, in Britain, France and other European jurisdictions, Muslims tend to come from poor communities and tend to suffer from low educational achievement, poor housing, and high levels of unemployment (Hussain 2008). The knock-on criminogenic effects of Muslim poverty have been aggravated by the collapse of industrial manufacturing in places of traditional Muslim migration, such as the North of England (Quraishi 2005). This collapse of the type of heavy labour that young Muslims have been educated to expect makes dealing in drugs and sex seem to some Muslims like the only viable and reliable money-making alternative to manual labour (Webster and Qasim 2018).

2.3. The Real and “Imagined” Link between Islam in Prison and Terrorism

Governmental and Muslim community concerns about the increasing numbers of incarcerated Muslims have been coupled with fears that the incarceration of well-known Muslim “hate preachers”, such as Abu Qatada, Abu Hamza al-Masri and Anjem Choudhary in prisons in “the West” is likely to provide a charismatic focal point for the spread of extremist radicalisation (Cohen 2016; HMIP 2010; UK Gov. 2016).

These concerns have recently sharpened to a point of intense political and media focus with the realisation that the terrorist attacks committed in France and Germany in late 2015 and 2016, in the UK in 2015, 2019 and 2020 and in Switzerland and Austria in 2020 were committed by second- and third-generation European Muslims, many of whom had spent time in prison for a range of petty or more serious crimes and some of whom had re-embraced extreme forms of faith in prison (Hunt and Solon 2016).

Micheron (2020) suggests, on the basis of 80 interviews with convicted terrorists, that Islamist terrorism in France has been generated at the intersection of the neighbourhood (quartier), a foreign site of conflict (in this case Syria) and prison (Micheron 2020). Moreover, adding fuel to this fire, the late head of Al-Qaeda in Iraq and progenitor of so-called Islamic State and its ideology, Abu Musab Az-Zarqawi (1966–2006), and the former leader of the so-called Islamic State group, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi (1971–2019), both identified incarceration as a key mechanism that led to their embrace of Islamist Extremism (McCants 2015). This association between prison and terrorism has generated a powerful discourse of prisons as "incubators" of Islamist Extremism (Rushchenko 2019). Moreover, it has been difficult for academics to confirm, nuance or challenge this discourse due to the dearth of original empirical evidence about extremism in prison (Silke and Veldhuis 2017) and, indeed, an absence of reliable understanding about what Islamist Extremism is (Wilkinson 2019).

2.4. Growing Islamic Virtues in Prison

By contrast to this both real and “imagined” connection between imprisonment and Islamist Extremism, Islam and incarceration have also existed in a productive relationship. Muslims affiliated with the Nation of Islam in the United States are accredited with limiting violence in prisons during periods of unrest during the Civil Rights movement (1954–1968) and with encouraging Black prisoners to engage in disciplined study and to avoid drugs, as in the famous case of the Civil Rights activist Malcolm X (Goldman 1974; Malcolm X 1998).

Recent research has also identified sincere Islamic piety and brotherhood in the High Security Estate in England (Williams 2018). Williams evidences different types of actions that individuals performed, which were geared towards the creation of an ethical, non-criminal self and “doing good”. These included internal acts, such as reading, and external acts of identification with Islam, such as growing a beard, relational acts of sharing gifts and food with others, and efforts towards developing an ethical community in which good acts are encouraged.

There is no doubt, therefore, that prisons are environments that possess the potential both to be productive and destructive for Islam and Muslims, particularly for those who embrace Islam in prison, and that Islam and Muslims in the future are going to become an increasingly significant part of the religious landscape of European prisons with knock-on effects for prison policy and chaplaincy.

3. Religious Conversion in Prison

Some of the fear and suspicion of Islam in prison is connected with the fact that a high proportion—c.30%—of Muslim prisoners in European prisons are converts to Islam, and converts to Islam have been disproportionately associated with terrorism (Moore et al. 2008). As outside prison, conversion to Islam in prison has garnered strong associations with extremism and terrorism (Hamm 2007, 2013). As we shall illustrate below, religious conversion of different types is a significant element of European prison life.

3.1. Extra-Faith and Inter-Faith Conversion

Religious conversion in contemporary contexts has tended to be understood from different disciplinary perspectives as the act of leaving one religious faith—inter-faith conversion—or no faith—extra-faith conversion—and its faith-based in-group and choosing to follow a different faith and, usually, belong to a different faith-based in-group (Rambo and Farhadian 2014). There has also been scholarly focus on the (sometimes gradual and sometimes abrupt) changes in identity, in self-understanding and values that form part of the process of conversion.

Research on conversion to Islam outside prison shows that conversion to Islam is not necessarily a sudden change; rather it often involves a long process of reflection and search for knowledge, whereby a person may initially reject previous belief and then, after several years, take up Islamic belief (van Nieuwkerk 2006; Hermansen 2014). Conversion can be prompted by several factors, these include an emotional, identity or spiritual crisis; a relational conversion, through marriage to a Muslim; a change which occurs due to reflective and intellectual engagement; as well as a form of political empowerment or resistance to a prevalent social order, as in the case of the Black nationalist, Nation of Islam (Hermansen 2014).

The literature suggests that the role of Islamic ritual in conversion is also often significant, converts can initially be attracted to observing Muslim rituals such as prayers, fasting or religious remembrance, such as reciting the names of God (dikhr). This is particularly relevant in the prison environment where prisoners live in close proximity to Muslims and Islamic beliefs are regularly articulated on the wings and Islamic rituals and objects are often on display. The community of Muslims, with which the convert is involved, can play a crucial role in influencing the beliefs and practices, i.e., Worldview, that the convert adopts (Hermansen 2014).

Importantly, religious conversion in prison often involves the construction of a new pious, non-criminal self (van Nieuwkerk 2014). The creation of a new pious self involves practising self-control and sacrifice, which is linked to a spiritual rebirth (Williams 2018). This new pious self can allow prisoners to adopt a new, non-criminal identity and move away from crime and criminal associates (Maruna et al. 2006; Spalek and El-Hassan 2007). Conversion involves a process whereby converts alter and reinterpret their own autobiography based on their new Worldview which influences all facets of a prisoner’s life (Snow and Machalek 1982).

3.2. Intra-Faith Conversion

Whilst it is more common for religious conversion to be understood as a change from one faith (or no faith) to another, intra-faith conversions refer to significant changes of interpretation, level of commitment and practice that can occur within a faith (van Nieuwkerk 2006). Sarg and Lamine’s (Sarg 2016; Sarg and Lamine 2011) research on religion in prison suggests that the use and understanding of religion by a single participant can vary over different sentences or even during a single experience of incarceration. This is important, as it points to the changing and shifting nature of religious belief in prison as a site in which many prisoners re-evaluate their core life-values (Hermansen 2014).

Again, with offenders, this intra-faith conversion may also be connected to a prisoner’s desire to leave behind a criminal identity and behaviour. Furthermore, for some serious offenders, e.g., terrorist and sex offenders, their crime has often been accompanied or justified by skewed or misunderstood versions of religion, together with a criminal in-group with a religious complexion, which makes a change in religious Worldview vital to their chances of leaving crime (Irfan and Wilkinson 2020; Wilkinson 2015a).

3.3. Cynical Interpretations of Religious Conversion in Prison

Contrary to academic findings which tend to identify pro-social potential in the process of religious conversion in prison, the image of the prison convert tends to provoke cynicism amongst prison staff and policy makers. For prison authorities, a sudden and complete positive change in the prison context can seem far too convenient to be believed (Maruna et al. 2006). Most frequently, sudden and dramatic change in the prison context is seen as inauthentic and linked to other strategic aims, such as gaining parole, getting time away from the cell or as a means of gaining sympathy (Clear et al. 2000). Prison ethnographies have raised concerns that conversion to Islam in prison is not sincere and can be a "fake identity" adopted for strategic purposes (Schneuwly Purdie 2020). Conversion to Islam in prison is often regarded as a means to receive protection and the safety of belonging to a group (similar to gang affiliation), or other perks and privileges, such as better food, power on the wings, as a means to intimidate staff or for time out of the cell for Friday prayers (Hamm 2009; Liebling et al. 2011; Phillips 2012; Spalek and El-Hassan 2007). Islam has been seen as the new “fast fame” religion adopted by converts to "look cool" without any sincere understanding or commitment to the faith (Phillips 2012, p. 97).

4. Generating the Empirical Data

4.1. The Background and Research Aims of “Understanding Conversion to Islam in Prison”

Set in this broader national and international context of pressing political concern about the presence of Islam and Muslims in European prisons, this paper is the outcome of the international research programme Understanding Conversion to Islam in Prison. This programme represents a large-scale, mixed-methods independently funded study undertaken between the years 2018 and 2020. The focus of the research was on the pro-social capacity for religious change to promote prisoner rehabilitation.

We structured our research interest in religious change into and within Islam into five research questions:

- Who are converts to Islam, broadly construed, in socio-demographic and religious terms?

- Why do many prisoners choose to follow Islam in European prisons?

- What types of Islam(-ism) are followed in prison?

- What are the benefits and risks of choosing to follow Islam in prison?

- How are processes of conversion and religious change managed by prison authorities and the Prison Chaplaincy?

4.2. Theoretical Framework: The Idea of Islam as a Worldview

A key element of our theoretical framework was to understand different types of Islam and Islamism as Worldviews. Worldviews are integrated ways of being in and knowing the world that draw together facts and fictions, laws, norms, generalisations and answers to ultimate questions. A Worldview represents the aspiration of the person to form a consistent idea of the self and its relationship to the world together with a concomitant way of behaving in the world (Naugle 2002; Orr 2001).

For this research, the idea of the Worldview was a useful theoretical framework. It encapsulated, in one concept and one word, both the idea of “religious praxis” which is the integrated combination of religious belief and practice and the Islamic notion of “deen” which is the individual’s moral and behavioural transaction with God and the world. Thus, on a point of research ethics, the idea of Worldviews as integrated ways of being in and knowing the world did justice in a non-religious way to the Islamic tradition of our research subjects.

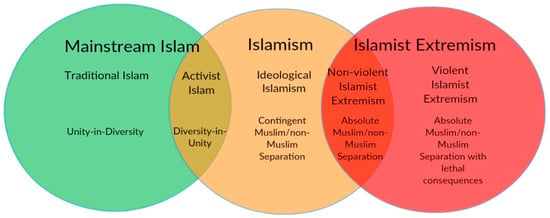

Using the earlier research of our Principal Investigator (Wilkinson 2019) and tested for its empirical utility with Muslim prisoners by means of a pilot study of 15 interviews, we defined these Islam-related Worldviews as follows (see Figure 1):

Figure 1.

The Worldviews of Mainstream Islam, Islamism and Islamist Extremism.

- Traditional Islam is the Mainstream Islamic Worldview of unity-in-diversity generated by the religious practice of those who accept and follow, to the best of their ability, the basic injunctions of the Qur’an and the Customary Prophetic Behaviour (Sunna) of the Prophet Muhammad, in a way that is appropriate to their circumstances without their aspiring to effect change in the public space.

- Activist Islam is the Mainstream Islamic Worldview, characterised by diversity-in-unity, and practised in part to effect transformative personal change and/or transformative structural change in the public space according to Islamic principles.Both Traditional Islam and Activist Islam were regarded as “Mainstream”.

- Ideological Islamism is Islam as revolutionary political ideology directed at overthrowing, rather than transforming, existing political structures and replacing them with an Islamic State governed by Sharia Law. It is the Worldview of exaggerated Muslim vs. non-Muslim separation and difference.

- Non-Violent Islamist Extremism is the Islamist Worldview as it sharpens antagonistically into an absolutely divided, Manichean Us vs. Them Worldview that stresses the absolute, irreconcilable difference between the “true” ideological Muslim “in-group” and the non-Muslim and “wrong” Muslim “out-groups”, who are afforded a less human or sub-human status.

- Violent Islamist Extremism is the absolutely divided, Manichean Us vs. Them Worldview by which the cosmos is constructed as a manifestation of the Eternal Struggle between Islam and Unbelief (Kufr). The non-Muslim and “wrong” Muslim, who do not struggle violently to establish a global Islamic state, are construed as eternal enemies of “true” Islam and, therefore, fit to be exterminated.

We tested this theoretical framework for accuracy and empirical utility in 15 pilot interviews which identified the fact that prisoners’ understanding and practice of their Islamic faith broadly mapped onto this interpretative theoretical framework and illustrated the themes that characterize each Worldview.

In particular, we noted in our pilot interviews how research participants articulated their belonging to Traditional, Activist and Islamist Worldviews. Importantly, these Worldviews were not pegged to any theological or denominational perspective; rather, they were characterized philosophically in terms of basic quality of being and behaving. Thus, we avoided the prejudices of some policy research on Muslim belief and behaviour, which often suggest, a priori, that Muslims are more likely to behave in an extreme way if they belong to one denomination, e.g., Salafi, as opposed to another, e.g., Sufi.

4.3. An Original Typology of Conversion

Our understanding of various forms of Islam/Islamism as Worldviews, together with analysis of our pilot data allowed us to conceive a typology of religious change that both accounted for extra-faith and inter-faith conversion, i.e., people choosing to follow Islam from another faith or none. It also enabled us to identify intra-faith conversion, i.e., the significant changes of understanding and practice of Islam that born-Muslims experience which we knew from the literature was likely to be a significant component of religious change in prison (Clear and Sumter 2002; van Nieuwkerk 2006, 2014). It also enabled us to factor in both the gradual and abrupt forms of conversion and the idea of religious conversion as all-encompassing change of identity.

Thus, we construed religious conversion broadly as any significant change of religious Worldview in terms either of type or intensity within a type. An abductive dialectic between our data and this definition generated a typology of the following types of conversion:

- Switching: Choosing Islam for the first time from another faith or none, i.e., extra-faith and inter-faith conversion. This was identified though our quantitative data.

- Intensifying: Becoming significantly more devout within an existing Islamic Worldview in terms of participants “strongly agreeing” that their faith was “more important” than before prison, and “strongly agreeing” that they were “praying more” in prison i.e., a form of intra-faith conversion. This was identified though our quantitative data.

- Shifting: Undergoing significant changes of Islamic Worldview in prison according to the framework in 4.2 above, i.e., a form of intra-faith conversion. This was identified though our qualitative data.

- Reducing: Those becoming significantly less devout in prison in terms of participants “strongly disagreeing” that faith was “more important” than before prison and “strongly disagreeing” that they were “praying more” in prison. This was identified though our quantitative data.

- Remaining: Unchanged Islamic Worldview and commitment to worship in prison. This was identified though our quantitative data.(“Switching” was identified through participants’ answers to Survey Question 3. Answer “Yes” to Q3: I have changed my religion in prison. “Intensifying”, “Remaining” and “Reducing” were calculated as follows: We calculated the average for the response to- Q6: “Compared to before I was in prison, NOW my religion is…” & Q7: “Compared to before I was in prison, NOW I pray”… Average of 4 or above was classified as an “Intensifier”. Average scores of between 3.5 and 2.6 were considered “Remainers”. This category included respondents who had answered “Same” to at least one of the two questions. Scores of 2.5 to 1 were respondents who felt that religion was “less important” in prison and also felt they “prayed less” in prison. They were classified as “Reducers”).

Although many prisoners’ lives exhibited more than one type of significant religious change, such as shifting and intensifying, cases whose experience of Islam in prison predominantly featured one type of change became categorised to that particular type of change. For example, prisoners predominantly characterised by a change in faith were switchers.

4.4. Methodology

Religious change amongst Muslims in prison as a subject of research exhibits both individual detail, intensity and depth and national and international breadth which mandated a mixed-methods approach. Our methodology took the form of the following sequence:

- Pilot Semi-Structured Interviews to test our theoretical framework and identify suitable quantitative variables.

- Quantitative Attitudinal Surveys.

- Full Semi-Structured Interviews.

- Observations of Friday Prayers and Islamic Studies classes.

4.4.1. Ethics

The research project was subject to rigorous ethical evaluation prior to data collection. This comprised approval via the researcher’s host university’s ethics board to satisfy, inter alia, issues of informed consent, confidentiality, engaging with vulnerable respondents through sensitive questioning, data protection and risk-assessments for prison-based research in line with the British Society of Criminology’s Statement of Ethics for researchers (https://www.britsoccrim.org/ethics/ accessed on 20 February 2021). In addition, the project required detailed scrutiny, formal approval and security clearance for each member by Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service National Research Committee for the English prisons. Similar approval was sought and granted for the respective Ministries in Switzerland and France.

4.4.2. Recruitment

Having identified prisons in each country with significant Muslim populations, the specific institutional recruitment of participants was enabled through the research team spending intense induction periods of five research days in each establishment. Not only was the induction period part of the security requirement for the researchers but it helped foster relationships between the team and key personnel and prisoners in each institution. Prisoner respondents were recruited via a combination of publicizing the research via distributing leaflets and in-person invitations at congregational prayers, religious classes and various work, training or education-based activities in each site. Chaplaincy teams and prison managers were instrumental in further publicizing the research aims and encouraging prisoners and staff to participate.

4.4.3. Analysis

Attitudinal Surveys were analysed using, as appropriate, basic descriptive statistics, including Frequencies, Correlations and Chi-Squares, Principal Component Factor Analysis and Linear Regressions. Semi-Structured Interviews were transcribed verbatim in the original languages (English, German or French). Each Semi-Structured Interview was first analysed with a focus on the respondents’ own narratives. Then the Semi-Structured Interviews were subjected to inductive, deductive and Axial Coding via NVivo.

The qualitative data—interviews, observation protocols and field notes—were triangulated with the quantitative data. Observations of Friday Prayers and Islamic Studies classes were particularly useful for understanding the institutional-level relationships between prisoners and prison chaplains. As well as interviewing 158 prisoners, we triangulated our data by interviewing 19 prison chaplains, 41 prison officers and 15 prison governors (see Table 1, below). Therefore, our study exhibited the triangulation of method and the triangulation of actor.

Table 1.

UCIP research prisons and sample by jurisdiction (all names of research prisons and participants are pseudonyms).

5. Basic Contours of the Research Sample

5.1. Prison Categories and Types

We researched in five English prisons, four Swiss prisons and one French prison in a variety of geographies, holding both sentenced and remand prisoners and covering all prison categories (for details of security categories see: https://prisonjobs.blog.gov.uk/your-a-d-guide-on-prison-categories/ accessed on 20 February 2021). Our research sample included all four security categories used in England and, to ease comparison, we adapted the equivalent security categories for use in Switzerland and France.

5.2. Socio-Demographic and Basic Religious Description of the Sample

Our sample was socio-demographically typical of prison populations in the three jurisdictions. The sample was overwhelmingly male (92%, n = 256) with females representing 8% (n = 22) of the sample. The sample clustered strongly in the 24–36-year-old age bracket.

The sample’s levels of education were also typical of a prison population with 19.3% (n = 45) having no qualifications mirrored exactly by the same number with a university degree 19.3% (n = 45). Half of the sample had either completed compulsory secondary school education (26.6%) or had done some vocational training (24.9%).

The sample’s sentence length and the seriousness of their conviction ranged from lesser offences carrying a few months of sentence to high-profile terrorist offenders and sex offenders with multiple life sentences. 10% (n = 29) of the sample were on remand.

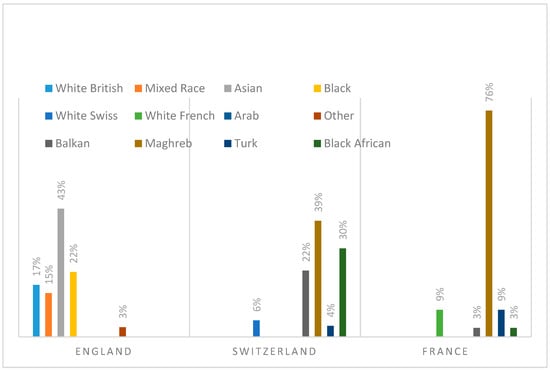

The sample was ethno-culturally highly diverse in a way that was highly indicative of the ethno-cultural background of Muslims in England, France and Switzerland, and also indicative in England and France of the over-representation of black communities in prison populations (for details, please see Wilkinson et al. (2021)) (See Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Ethno-cultural background of UCIP sample.

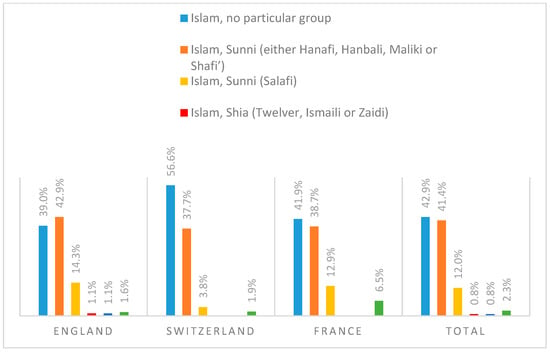

Denominationally (see Figure 3), the sample predominantly self-identified as:

Figure 3.

Denominational affiliation within Islam.

- “Islam, no particular group” (43%, n = 114).

- “Islam, Sunni” (39%, n = 110).… with a representation of those who identified with

- “Salafi Islam” (12%, n = 32).

- “Shia” denominations (2%, n = 4).

- “Islam, Other” (2.3%, n = 6).

The high levels of “Islam, no particular group” 43% (n = 114) were indicative of a sample of whom 29% (n = 76) were converts to Islam and who are less likely to possess strong denominational affiliations than people born into Muslim families. 22% (n = 56) of the sample had converted to Islam in prison and 7% (n = 20) had converted to Islam outside prison.

The strongly Sunni representation was indicative of the fact that circa 85–90% of the Muslim population of Europe is Sunni rather than Shia, the other major Muslim denomination (Pew Research Centre 2017).

6. Significant Levels Religious Conversion in Prison: High Numbers of “Switchers” and “intensifiers”

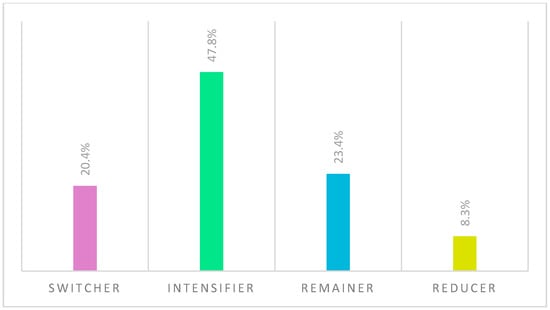

Our typical sample of Muslim prisoners was characterised by a high degree of significant religious change so that switchers and intensifiers predominated (see Figure 4):

Figure 4.

Types of conversion in the UCIP research sample of Muslim prisoners (%).

- ▪

- Switchers who had chosen to follow Islam for the first time from another faith or no faith in prison represented 20% of the sample (n = 56). (Decimals are rounded up or down).

- ▪

- Intensifiers who had become significantly more devout in terms of performing the Islamic Obligatory Prayer more regularly and finding their religion “more important” than before they went to prison represented 48% of the sample (n = 134).

- ▪

- By contrast, Remainers whose understanding and commitment to their faith remained broadly the same in prison as before represented 23% of the sample (n = 62).

- ▪

- Reducers whose commitment to their faith had decreased represented 8% (n = 22) of the sample.

6.1. The Significant Differences in Switching and Intensification Across Jurisdictions

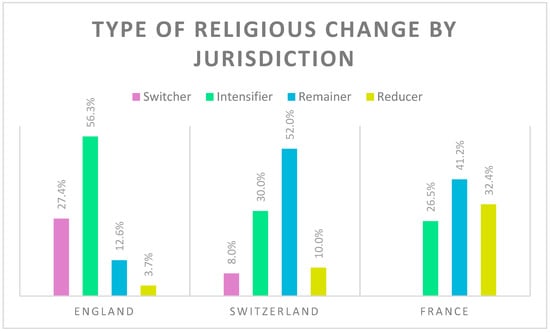

In all five English prisons, switching into and intensifying in Islam were the predominant feature in the religious life of our sampled prisoners (see Figure 5). In our English sample of 191 Muslim prisoners:

Figure 5.

Type of religious change in prison in different jurisdictions.

- ▪

- 84% were categorised either as switchers (28%) or intensifiers (56%).

- ▪

- 13% were categorised as remainers.

- ▪

- 4% were categorised as reducers.

Our samples in Switzerland and France were more characterised by remaining and reducing. In the Swiss our sample of 55 Muslim prisoners from five Swiss prisons:

- ▪

- 38% were categorised either as switchers (8%) or intensifiers (30%).

- ▪

- 52% were categorised as remainers.

- ▪

- 10% were categorised as reducers.

In the French our sample of 34 Muslim prisoners:

- ▪

- 27% were categorised as intensifiers (26.5%).

- ▪

- 0% were categorised as switchers, i.e., choosing Islam for the first time in prison.

- ▪

- 74% were categorised either as remainers (41.2%) or reducers (32.4%).

Post hoc analysis involving pairwise comparisons using the z-test of two proportions with a Bonferroni correction revealed statistically significant differences in median intensification scores between the England (4.5) and Switzerland (3.5) (p = 0.008), and England (4.5) and France (3.0) (p < 0.0005) but not between France (3.0) and Switzerland (3.5).This confirmed that prisoners in English prisons were significantly more prone to conversion to or within Islam than in their Swiss or French counterparts.

It should also be noted that the 8% of our sample who were women were more prone to reducing and remaining than the men, and that for women, prison was a much less conducive environment for conversion to or within Islam than it was for men for reasons that we report elsewhere (Wilkinson et al. 2021).

6.2. The significance of “Engagement with Chaplaincy”

6.2.1. Different Levels of "Engagement with Chaplaincy" across Jurisdictions

The higher levels of switching and intensifying in England were partly explained by the significantly lower baseline religious commitment to Islam from which prisoners in England started. For example, 30% (n = 56) of prisoners in England stated that "before I came to prison, my religion was very important to me" compared with 56% (n = 29) of our Swiss sample, and 44% (n = 15) of our French sample. This meant that, in England, compared to France and Switzerland, the conspicuously religious component of prison life in the form of formal chaplaincy provision made a greater impact on prisoners’ existing Worldviews.

In this respect, our factor Engagement with Chaplaincy which was built out of a number of significantly related variables that measured prisoners’ engagement with prison chaplaincy provision, was significantly predictive of intensifying. There were significant differences in Engagement with Chaplaincy across the jurisdictions, in particular between England and Switzerland.

- ▪

- In England, 55% (n = 104) had a “HIGH” level of Engagement with Chaplaincy.

- ▪

- In Switzerland, 42% (n = 23) had a “HIGH” level of Engagement with Chaplaincy.

- ▪

- In England, 6% (n = 12) had a “LOW” level of Engagement with Chaplaincy.

- ▪

- In Switzerland, 26% (n = 14) had a “LOW” level of Engagement with Chaplaincy.

6.2.2. Different Quality of “Engagement with Chaplaincy” across Jurisdictions

In terms of the differing quality of chaplaincy provision, in our English prisons those prisoners who registered as Muslim received:

- Weekly statutory visits from professional chaplains of a variety of faiths, including professional—usually full-time—Muslim prison chaplains;

- Regular Islamic Studies classes of at least two hours per week. In HMP Coquet (Category C) and HMP Severn (Category B) prisoners could choose to attend two 2-hour Islamic Studies classes per week;

- Regular Friday Prayers delivered by a professional and qualified Muslim prison chaplain.

This meant that, in England, many prisoners received formal, professional religious instruction in Islam for the first time.

In Switzerland, the chaplaincy provision was inconsistent and varied greatly from one prison to the other. With the exception of Mitheilen, which had the only full-time paid Muslim chaplain in Swiss prisons, the regular spiritual needs of the Muslim inmates were met by the Christian chaplains and there were no statutory visits by a professional Muslim chaplain. In most Swiss prisons, Muslim inmates had regular access to Friday prayers conducted by a community volunteer rather than a professional Muslim chaplain. In three of our four Swiss prisons, there were no Islamic Studies classes at all.

In our French prison, although both the Friday Prayer and a weekly study circle were organised, prisoners were only permitted to attend the study circle once a month. Our interviews showed that observant Muslim inmates often avoided attendance at official chaplaincy events, since the Muslim chaplains themselves were often looked at as “agents of the state” in its action plan against radicalisation (de Galembert and Béraud 2019; Rostaing et al. 2015) and thus were subject to suspicion. Conversely, prisoners also feared that if they attended chaplaincy events, they would be branded as religious and, therefore, as radical.

6.2.3. Religion in English Prisons More “the Done Thing” Than in Switzerland or France

These significant differences in levels of conversion and chaplaincy provision meant that, as became clear at interview, in England, converting to and within Islam were part of prisoners’ expected landscape of religious experience. In France and Switzerland, religion in general and the practice of Islam, in particular, was much less “the done thing”. For example, two French prisoners expressed the view at interview that “you don’t come to prison to do religion”. Whereas in England, no-one expressed a similar sentiment and, as we will see below, many prisoners felt that, in prison, they enjoyed, often for the first time, the formal religious teaching and the access to qualified chaplains which helped them (back) on the path to Islam.

These institutional differences in chaplaincy provision were also a reflection at the national level of the different legal and cultural status of religion in general, and of minority non-Christian religions, in particular, within the three jurisdictions. It is beyond the remit of this paper to discuss these legal–cultural differences further.

7. Reasons for Switching to or Intensifying in Islam in Prison

Having ascertained quantitatively that our prisons, especially in England, were sites of intense conversion activity into and within Islam we were keen to find out prisoners’ motives for choosing Islam. We have outlined (3.3, above) how recent research, media reporting and policy discourse has often focused on how choosing to follow Islam in prison is a strategic, opportunistic or an insincere choice.

7.1. The Views of Muslim Prisoners

Against this background discourse that prisoners choose to follow Islam for fast fame, perks and privileges (Easton 2010), we asked prisoners in our Survey to tell us why they chose to follow Islam. Survey Question 31 “I CHOOSE to follow Islam in prison because…” allowed respondents to choose from a range of reasons for their choice of Islam and included an open-option: “None of these, I follow my religion because” (please write here)… Respondents could tick as many options as they felt were applicable (see Table 2).

Table 2.

UCIP sample’s reasons for choosing to follow Islam in prison.

The reasons listed above that our indicative sample of prisoners selected for their choice of Islam clustered into five broader categories:

- Piety (Reasons: #4 + #8 + #9)40% of responses.

- Emotional coping (Reasons: #6+ #7+ #11)31% of responses.

- Company (Reason #1)7% of responses.

- Perks and Privileges (Reason #3)2% of responses.

- Protection (Reason #2)1.5% of responses.

Therefore, our data challenged the received “perks and privileges” discourse cited above, in that piety, emotional coping and seeking company were by far the most cited reasons by prisoners for choosing Islam. Indeed, “piety” and “emotional coping”—both essentially the seeking of intrinsic resources of spiritual and psychological support and far from “fast fame” or “perks”—were ranked top by a considerable margin.

7.2. The Views of Prison Officers

While the prisoners themselves expressed these largely sincere and pro-social motives for choosing Islam, prison officers were much more likely to view conversion to Islam—both switching and intensifying—as opportunistic, superficial and gang-related. Mark at HMP Parrett (Category B) typified the officers’ point of view:

I generally feel that a vast majority of these conversions are gang related. What tends to happen on some of the wings is, a prisoner will come in, and he will get a visit, and then he might be a Muslim the next day or say he’s a Muslim. Yes, and they might do it for protection. I dare say, there are cases when that isn’t the case, and I’m aware that it’s not always like that, but that’s generally what I feel happens here, if I’m honest.

This wide gap between prisoners’ and officers’ perceptions suggests that the officers tended to be over-suspicious of prisoners’ motives, especially in relation to Islam. The gap is also a reflection of the fact that the registered Muslims whose conversions were opportunistic probably chose not to engage with our research as much as those who were sincerely committed to their faith.

7.3. Piety, Good Company and Emotional Support

Even so, our data provided an important corrective to lazy assumptions about why prisoners choose to follow Islam. The data from our indicative sample strongly suggests that Muslim prisoners in European prisons are more likely to choose Islam for reasons of faith, good company and emotional support than for perks, privileges and protection.

8. The Evidence and Effects of Piety

Our qualitative data provided rich evidence of these intrinsic benefits of prisoners choosing to follow Islam in terms of piety, good company and emotional support, corroborating effects that had been identified more fleetingly in previous research (Clear et al. 2000; Liebling et al. 2011; Spalek and El-Hassan 2007; Williams 2018; Williams and Liebling 2018).

8.1. Making Repentance and Seeking God’s Forgiveness through Obligatory Prayer

Consistent with our quantitative survey results, “seeking forgiveness” and “making repentance” were cited in total 90 times in our 158 prisoner interviews. An important part of the emotional and spiritual appeal of Islam for switchers and intensifiers was the ability to ask forgiveness of God and to repent of their crime.

This relationship between intensifying in Islam and repentance was illustrated at interview and often enacted through prisoners’ returning to the Obligatory Prayer (Salah). For example, for Omair (35, Bangladeshi British, born Muslim, in HMP Severn Medium Security local prison)—an Intensifier—the act of asking repentance was specifically connected to his return to perform the Prayer in prison.

UCIP: …Has your practice of Islam made you think about that [your crime]? […] make tawba [repentance]?Omair: I did tawba every day and even though, I don’t know why it’s happening, I never ever prayed five times a day.UCIP: When you were outside?Omair: When I was outside, never. But since I’ve been in prison, if I miss one salat [Obligatory Prayer] or get late, I’m getting crazy.

These regular acts of repentance through Obligatory Prayer helped prisoners construct and then sustain a positive identity in which they could move past their crimes towards a more positive new life (cf. Maruna et al. 2006; Williams 2018).

8.2. Regaining Balance and Calm

The emotional release of asking forgiveness and making repentance meant that intensifying in Islam was strongly connected by prisoners with re-gaining balance, calm and inner peace. This connection was cited 121 times at interview, for example, by an intensifier, Fahd (34, Asian Pakistani, born Muslim, HMP Parrett Medium Security local prison):

UCIP: So tell me, what does the act of praying five times a day give you? What does it add to your life in prison?Fahd: It gives you like peace and that. How can I explain to you? It makes you feel better after you’ve done a prayer, because when I’m outside, I don’t pray. I don’t pray, to tell you the truth, and when I’m in prison, I do pray, I come to Jumu’ah and that. It’s very rare I pray outside or read the Qur’an […]it makes me feel better and that, it makes me feel cleaner and that, if you know what I mean?

As we will see (8.4, below), Fahd’s account was typical of a number of prisoners who contrasted the ease of practising their faith “inside” with the difficulties and distractions that they faced “outside”.

For a female switcher prisoner, Brigitte (Brigitte, 44, Black Caribbean British, Switcher, in HMP Parrett Medium Security local prison), exposure to the female Muslim chaplain brought her peace and joy and the ability to ‘cherish the moment’:

UCIP: And now that you’re in prison…what does Islam mean for you now?Brigitte: Well, Islam, honestly, all the time in prison and speaking to the chaplaincy, it pulled me closer. Because, how it makes me realise that […] They’re so peaceful, they’re really peaceful. They make me feel really joyful with the little, little time that they have with us. It don’t be much. So in that little time that we have with one another, I find we always cherish that moment, you know.

8.3. Finding Purpose

Related to the balance and peace brought about through the performance of the Obligatory Prayer was the sense that the lives of prisoners who switched to Islam or who intensified in Islam in prison had reconnected with a divine purpose. This included the feeling or belief articulated by intensifiers and switchers on many occasions that their conviction and sentence was part of a Divine Destiny which had spared them from a worse fate, e.g., death, and had given them the opportunity to find Islam. Bashir (Bashir, 33, Asian, born Muslim, in Coquet Low Security training prison), an intensifier, was unequivocal,

“I think I’m just being saved, God’s put me through the hardship, but only because he loves me, that’s what I believe. So, everyone around me, I try to say to them, “Whether you’re Muslim or non-Muslim, reflect on something and become something better.” Because this ain’t a punishment, the grave is your punishment, so if God’s given me the years to say, because there’s a saying I say, what would you rather do, ten years in prison or eternity of a hellfire? […] Allah is saving me, so maybe there was something bad going to happen around the corner or the next years, maybe it was on a plane journey or this or that. So, just have patience, because look where God’s put you. This is what you need to understand about life. Don’t take prison as a punishment. “

Seeing imprisonment as part of God’s plan helped participants move on from fixating on the circumstances of their conviction, including in many cases feelings of anger, resentment and injustice, and to reframe their lives in prison as an opportunity from God to bring about positive personal change. It was a belief that brought a number of prisoners a high degree of emotional support and was a powerful mechanism for coping with imprisonment.

8.4. Structuring Time

As reported above, a major factor in religious conversion in prison, including a return to the Obligatory Prayer, is the availability of time and the ability of Islam with its regular prayer times to mark it constructively. In the mundane routine of prison, particularly when prisoners spend long hours in their cells, prayers could help them mark the passing of time and to find purpose in their time alone.

UCIP: So, tell me how, how does the practice of your faith, the prayer, the wudhu [ritual ablution], how does that fit into your day?Wayne: (32, Mixed Race British, Switcher, in HMP Forth High Security Prison.) It gives you a regime and it gives you some continuity and purpose. Although, it can be more difficult within this environment where you’re out more, I’m used to being in my cell all day, you know, 22 plus hours a day, so you haven’t got an excuse for missing a prayer, you’re in the cell, you know, you can’t miss the prayer.

Prisoners found that, in prison, as opposed to outside, they had time to pray, including doing the Five Obligatory Daily prayers on time; time to read religious texts, including for prisoners who were dyslexic or who had suffered poor educational experiences at school, and time to reflect in their cells.

The idea that God was giving them time to reflect enabled intensifier and switcher prisoners to construe even unpleasant circumstances, such as isolated periods in segregation, as opportunities for study and reflection. Bashir (33, Pakistani British, born Muslim, in HMP Coquet Low Security Training Prison) explained,

“Well, you’ve got life experience as well, isn’t it, so sometimes you have to experience the bad to understand what is good. Here, we get punished, we go to segregation units and that gives you time to reflect and think of what have I done? And then, even in those places, they give you chances, you don’t just have the Qur’ān, you can read books, other books, and maybe understand and learn things. So, He’s [God] giving me that time to say, “Read, understand, learn, but don’t do it for the sake of doing it, do it because you’re sincere about it.” Do you understand?

A number of prisoners expressed the view that the absence in prison of the affairs of this world (dunya) gave them time and space to concentrate on the spiritual affairs of the Next World (akhira):

Owais (43, Pakistani British, born Muslim, HMP Stour, Open Prison.): Yeah. First of all I was just sitting in my cell and I thought I’ve just got to start praying and just get back to normality basically because out there in dunya we’re just all focusing about who’s got the biggest car and who’s got this and who’s got that and at the end of the day that’s nothing. If you die tomorrow that’s going to stay behind. What’s going to get you into akhira is what you’ve got in your, your prayers, you know. That’s your bank balance. Not your real bank balance that was out there.

This element of conversion to or within Islam as a rejection of materialism often reflected an identity-shift of the prisoner sloughing off a previous life of crime which had been driven by an excessive desire for material gains (Maruna et al. 2006). Other non-materialist values which prisoners credited at interview to their increased connection to their faith, included ▪ Courage, 15 citations. ▪ Empathy, 74 citations. ▪ Equality and Fairness, 50 citations. ▪ Gratitude, 22 citations. ▪ Hope, 49 citations. ▪ Humanism, 61 citations. ▪ Humility, 17 citations. ▪ Patience, 35 citations. ▪ Peace and non-violence, 73 citations. ▪ Politeness and respect for others, 70 citations. ▪ Responsibility and duty, 68 citations. ▪ Sincerity, 14 citations. ▪ Tolerance, 33 citations. ▪ Trust, 15 citations. ▪ Work Ethic, 25 citations.

As well as the prisoners, Governor David at HMP Parrett (Category B) expressed the view that the timed shape of Islam itself—with Obligatory Prayers at prescribed moments (Qur’an, 4:103)—was conducive for prisoners doing time in prison and enabled prisoners whose lives outside had often been chaotic to bring order and structure to their day.

9. The Evidence and Effects of Good Company

64% (n = 179) of the sample said that they had either “always” or “sometimes” turned to other prisoners for religious knowledge or advice. In line with these quantitative findings, the company of other prisoners was both valuable for psychological support and instrumental in nudging prisoners towards an intensified religious practice. We heard multiple accounts at interview of how the company of other prisoners had been a source of religious encouragement or example.

The company of Muslim brothers and sisters (for a discussion on gender differences within our sample, see Wilkinson et al. (2021) was important in a number of ways. It helped participants maintain their prayers, learn more about their religion through discussions and the sharing of books and other educational material. It also provided mentoring support to take up pro-social activities and avoid involvement in illicit activity, which was often framed in terms of being religiously forbidden (haram).

Mahfuz (Mahfuz, 24, Turkish, Intensifier, HMP Coquet Low Security Training Prison) explained: Then when I come here and I met loads of brothers, there’s actually quite a few brothers here, over 50 brothers, and any workshop you go to, any workshop … you could be doing anything, brothers always invite you to pray. Yes, so I see big changes from selling drugs, not caring about many things, to not doing anything and believing in Islam […] so I was getting more into Islam, hanging around with the brothers more. Then they showed me guidance.UCIP: So, what type of guidance? Tell me, what form did that take? I mean, were they talking to you about what’s halal and haram?Mahfuz: Yes, of course, they were showing me that selling drugs is no go […] So, the brothers have showed me what’s right, what’s wrong, what’s haram. So yes, like that’s it.

This framing of certain activities as forbidden by God, and not simply as illegal, added a protective layer against offending. This was especially the case when it was done in the company of other trusted and respected Muslim prisoners.

10. The Rehabilitative Tendency Inherent in Conversion to and within Islam

The sense of discipline, renewed purpose, and a determination to avoid crime by following their faith that switchers and intensifiers expressed at interview was strongly borne out in more detailed analysis of the Questionnaire Surveys. This was particularly the case in relation to our factor Attitude to Rehabilitation. A multiple linear regression established that the factors Religious Intensification and Engagement with Chaplaincy could successfully predict Attitude to Rehabilitation in the form of a renewed commitment to work and education and to giving up "bad behaviour". In fact, Religious Intensification and Engagement with Chaplaincy explained 30% of the variation in Attitude to Rehabilitation (R2 for the overall model was 31.5% with an adjusted R2 of 30.9%, a moderate size effect (Cohen 1988). The regression model is statistically significant, F (2269) = 61.72 p < 0.0005).

Moreover, there was a statistically significant relationship between the stronger levels of Attitude to Rehabilitation in England compared with France and Switzerland and the higher levels of Religious Intensification in England compared with France and Switzerland. This post hoc analysis revealed statistically significant differences in median “Attitude towards Rehabilitation” scores between the England (3.0) and Switzerland (2.33) (p < 0.005), and England and France (2.0) (p < 0.005) but not between France and Switzerland.) These differences add weight to our finding that intensifying in Islam was a significant driver of positive attitudes to rehabilitation in the form of a commitment to work, education and the avoidance of crime.

(Attitude to Rehabilitation was calculated by adding and calculating mean scores on response to the following questions: Q20 Because of my Islam, I have taken up a class, a training course or some private study in prison; Q21 Because of my Islam, I am motivated to work hard in prison; Q10 I give up bad behaviour for my religion. Religious Intensification was calculated by adding and calculating mean scores on response to the following questions: Q6 Compared to before I was in prison, NOW my religion is…much more important; more important; equally important; less important and much less important and Q7 Compared to before I was in prison, NOW I pray… much more; a bit more; the same; less; I do not pray).

10.1. Work

These rehabilitative benefits of switching to and intensifying in Islam in terms of an increased commitment to education and work were illustrated strongly at interview and in observations. Our data contain numerous reports from prisoners who claimed that their faith provided them with focus and patience but also encouraged a positive work ethic.

For example, we observed a carpentry workshop at HMP Stour (Category D) during which a Muslim switcher prisoner said, “I choose carpentry ‘cos I like to do things with my hand. If I done it before I wouldn’t have ended up here.”

We asked him if his work was connected to his Islamic faith, he replied, “Yeah… This keeps you on the straight and narrow.” The implication of his response was that the combination of learning a trade and maintaining his Islamic faith was instrumental in, “keeping him on the straight and narrow”.

10.2. Reading and Education

The beneficial effects of time spent by intensifiers and switchers on religious reading and reflection (noted in 8.4, above) had knock-on effects in more general renewed commitment to education. Religious Intensification was strongly (0.348) and significantly (p < 0.000) positively correlated with a renewed commitment “to take up a course of training or some private study”, even though educational provision was often far from satisfactory.

For other prisoners, the values of their faith engendered a respect for books and learning more generally.

UCIP: Do you not have access to other, broader books from the library?Aaban (40, Pakistani British, Intensifier, in HMP Coquet Low Security Training Prison.): Very, I mean, there are good books in there but I’m probably the only one who’s ever going to read them. There’s a book on Sufi-ism, I’m the only one who’s read them. There’s a book by, you know, the Dutch Somali lady who left Islam and talked about what’s wrong with Islam, I’ve read that book, they would never read it. I’ve read Satanic Verses on the 30th anniversary of Satanic Verses. A prisoner saw it in my cell and said, “Brother, I want to burn it,” I had to bring it back. Now, this is where my din (religion) helped me. Even though that is something sacrilegious in my religion, I know that, I still have the sense of duty that I have an amana (religious trust) from the library that I have to give back to the library and I’m not going to burn it. Sticks and stones.

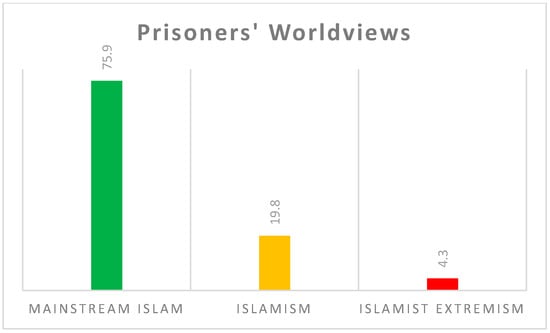

This account was typical of the fact that, for many of the prisoners that we interviewed, their religious faith was more likely to moderate their behaviour than it was to make it more extreme, and also that prisoners with a sincere commitment to Mainstream Islam played an important role of moderating others’ extreme views. In this respect, it is to be noted that 76% of our sample fell within a Mainstream pro-social Islamic Worldview of Unity-in-Diversity that tended towards pro-social behaviour (20% fell in the Islamist Worldview and 4% fell in the Worldview of Islamist Extremism) (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Basic Worldviews of the UCIP sample.

11. The Islamist Risk Inherent in Switching to and Intensifying in Islam

The values encouraged by switching to or intensifying in Islam were not, however, uniquely conducive to prisoners expressing a Mainstream Muslim Worldview of Unity-in-Diversity and to encouraging a renewed commitment to rehabilitation. We also identified an element of risk in both conversion to and within Islam. For example, there was a statistically significant over-representation of switchers and intensifiers in the exaggeratedly separate “Us” versus “Them” Worldview of Islamism and in the absolutely divided “Us” versus "Them" Worldview of Islamist Extremism.

Switchers and intensifiers together constituted 68% (n = 185) of the whole sample. However, switchers and intensifiers together constituted 81% (n = 43) of those in the Worldview of Islamism with an exaggerated “Us” versus “Them” Worldview.

Moreover, switchers and intensifiers together constituted 83% (n = 9) of those in the Worldview of Islamist Extremism with an absolutely divided “Us” versus “Them” Worldview. The only recorded Violent Islamist Extremist (100%, n = 1) was a switcher from HMP Coquet, Category C, England.

This showed up some risk in terms of adopting an “Us” versus “Them” Worldview connected to conversion to and within Islam, which can on occasion exacerbate the existing “Us” (The Prisoners) versus “Them” (The Officers) of the existing prison environment. We observed occasions of this prison Islamist Worldview enacted on the wings and in Islamic Studies classes when prisoners mobilised their Islam to emphasise their difference and even hostility to prison authorities, including prison chaplains, by, for example, refusing to pray behind prison chaplains at the Midday Prayer in HMP Forth or by aggressively trashing copies of the prison magazine for Muslims in HMP Coquet. Our interviews also showed up the fact that some intensifiers chose to justify their crime using a false Islamist rationale that crime against the infidel (kuffar) was sanctioned in Islam.

We explore the Islamist risk connected with switching to and intensifying in Islam and its implications for prison practice more deeply elsewhere (Wilkinson et al. 2021).

12. The Reducers

As well as needing to be honest to our data by articulating the Islamist tendency inherent in some Islamic switching and intensifying, our prisons were not always environments that were conducive to an intensification of Islamic practice and belief. Incarceration could also result in a reduction in commitment to Islam. In total, 8% of our survey respondents were Reducers who found their Islam significantly less important and prayed significantly less than before prison. Reducers constituted

- ▪

- 4% (n = 7) of the total sample in England;

- ▪

- 10% (n = 5) of the total sample in Switzerland;

- ▪

- 32% (n = 11) of the total sample in France.

At interviews, several of these prisoners spoke about becoming less devout as they moved closer to release. When they felt that they had a long sentence ahead of them, religion had been more important in helping to cope. Furthermore, they spent more time in their cell at the start of their sentence when they felt that there were fewer distractions. Some participants also felt that their commitment to following their religion was linked to being part of a religious community, which had been a stronger presence in the High Security Estate than in the Low Security Estate.

Hussain (35, Asian Pakistani, born Muslim, HMP Coquet Low Security Training Prison): [My Islam became less] Because I became a Cat-B prisoner. I came out of the maximum-security conditions, now I’m not surrounded by these motivational brothers as much, now I’m putting, the sheitan (devil) putting the excuses, “Forget salat [prayer] right now, I’ll do it later.” I’m not, I haven’t got a cell to, I’ve to be there otherwise a brother’s going to be looking for me, there’s none of that no more. Now it’s all on my own and slowly my resolve is getting weaker, slowly I want to watch EastEnders a little bit more, I can’t be arsed to wake up, I had a late night last night, fuck it. Someone’s give me some puff, I’ve just smoked a spliff, I can’t pray for 40 days now anyway, forget it, yeah? But I’m not stopping smoking, so now I’m enjoying it, do you see what I’m saying?

This is an example of what Wilkinson (2015b), following Hegel, calls the Unhappy Muslim Consciousness: the prisoner is aware that he is drifting away from his religion, feels that he is in the grip of "Satan" and yet feels powerless to do anything about it.

Shaun, a TACT offender, had started his sentence in the High Security Estate and had moved down to a Low Security Training Prison. He felt that religion had become less important for him in the dispersal prison as there were not as many practising Muslims on his wings.

UCIP: Do you find that your practice of Islam has changed in prison?Shaun (32, Mixed Race British, born Muslim, HMP Coquet Low Security Training Prison): Yes it’s become weaker I think […] Because it’s hard not having the support of your family and you don’t get much support in here. Like people in here the people that I know who pray, they seem to be quite scared of praying in congregation here. And in dispersal … do you know what I mean by that?

Shaun’s experience corresponded to the view expressed to us informally three times in English prisons that, as the security category decreased, so did the level of commitment to Islam. However, this anecdotal evidence/feeling from some prisoners that prisoners’ faith became less intense as they moved "down" Security Categories was not confirmed by our quantitative data, which showed, to the contrary, that Intensification in Islam was significantly and inversely related to Security Category (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Type of religious change by security category.

In the sample,

- ▪

- Intensifiers were 79% (n = 15) of the D Open Category sample;

- ▪

- Intensifiers were 53% (n = 30) of the C Low Security Category sample;

- ▪

- Intensifiers were 46% (n = 64) of the B Medium Security Category sample;

- ▪

- Intensifiers were 36% (n = 21) of the A High Security Category sample.

Although it should be noted that our D Category data came from one prison, these correlations, especially when read alongside the inverse trajectory of remaining, suggest that, if prisoners retain their faith throughout their prison sentence, the faith is likely to have intensified as they come closer to release.

Additionally, whilst many of the prisoners seemed to understand the outward identifiers of Islam, such as clothes and a long beard, as indicators of religious intensification, our variables that measured inner commitment to the Obligatory Prayer and finding religion “important”. Therefore, triangulating the two findings, we can hypothesise that, rather than reducing, switchers’ and intensifiers’ faith tended to mature and become less overt over the course of their sentence, but no less strong.

13. Summary

Prisons in Europe are sites of intense religious reflection and change often enacted powerfully through the medium of Islam. In a “new” Abrahamic register, many prisoners in European prisons who choose to follow Islam are enacting some of the founding religious penitential purposes of state incarceration, such as repentance, moral reform and a rehabilitative commitment to work and education.

Despite populist and journalistic discourse, which tends cynically to cite opportunistic reasons for prisoners choosing to follow Islam, prisoners are more likely to choose to follow Islam in prison for reasons of piety, as a mechanism for emotional coping and for good company rather than for perks, protection and privileges.

Switching to and intensification in Islam are significantly connected to improved attitudes to rehabilitation in terms of engagement with work, education and the avoidance of crime. Nevertheless, switching to or intensifying in Islam in prison also carry some risk of prisoners shifting towards an “Us” versus “Them” Islamist Worldview.

Our research shows that choosing to follow Islam in prison presents prisoners both with significant rehabilitative opportunities and some criminogenic risk. Both types of outcome of conversion to and within Islam merit further research and action in terms of prison policy and practice, so that the criminogenic risk of this religious choice can be minimised, and its rehabilitative tendency enhanced.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.W., M.Q., L.I., M.S.P.; Methodology, M.W., L.I., M.Q., M.S.P.; Formal Analysis, M.W., L.I., M.Q., M.S.P.; Investigation, M.W., M.Q., M.S.P., L.I.; Data Curation, L.I.; Writing—original draft preparation, M.W., L.I., M.Q., M.S.P.; Writing—review and editing, M.Q., M.S.P.; Project Administration, M.W.; Funding Acquisition, M.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was generously funded by the Dawes Trust.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support and input of the Steering Group of Understanding Conversion to Islam in Prison and, in particular, James Beckford and Eoin McLennan Murray for their sage advice and dynamic support. We would like to acknowledge the trust placed in us by Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service, UK and the Prison Services of Switzerland and France by granting us access to prisons to conduct our research. In particular, we would like to acknowledge the contributions of prison governors, prison chaplains, prison officers and prisoners from the ten prisons without whose friendly participation this research would not have happened but who, for reasons of anonymity, must sadly remain nameless.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Clear, Todd R., and Melvina T. Sumter. 2002. Prisoners, Prison, and Religion. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation 35: 125–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clear, Todd, Patricia Hardyman, Bruce Stout, Karol Lucken, and Harry Dammer. 2000. The Value of Religion in Prison. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 16: 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Jacob. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. New York: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, David. 2016. The Jihadi Training Camp Right in the Heart of London. Evening Standard. Available online: http://www.standard.co.uk/news/london/the-jihadi-training-camp-right-in-the-heart-of-london-a3249941.html (accessed on 28 September 2016).

- de Galembert, Claire, and Celine Béraud. 2019. La Fabrique De Aumonerie Musulmane Des Prisons En France. 217.04.19.06. Paris: Mission De Recherche: Droit and Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Easton, Mark. 2010. BBC Mark Easton’s blog UK: Islam Prison Conversions. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/blogs/thereporters/markeaston/2010/06/islam_prison_1.html (accessed on 26 February 2021).

- Fatsis, L. 2021. ‘Policing The Union’s Black: The Racial Politics of Law and Order in Contemporary Britain’. Chapter 10. In Leading Works in Law and Social Justice. Edited by Faith Gordon and David Newman. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, Peter Louis. 1974. The Death and Life of Malcolm X. London: Gollancz. [Google Scholar]

- Hamm, Mark. 2007. Terrorist Recruitment in American Correctional Institutions: An Exploratory Study of Non-Traditional Faith Groups Final Report. Washington DC: National Institute of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Hamm, Mark. 2009. Prison Islam in the Age of Sacred Terror. British Journal of Criminology 49: 667–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamm, Mark. 2013. The Spectacular Few: Prisoner Radicalization and the Evolving Terrorist Threat. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hermansen, Marcia. 2014. Conversion to Islam in theological and historical perspectives. In Oxford Handbook of Religious Conversion. Edited by L. Rambo and C. E. Farhadian. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 632–66. [Google Scholar]

- HMIP. 2010. Muslim Prisoners’ Experiences: A Thematic Review. London: Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons. [Google Scholar]

- Her Majesty’s Prison & Probation Service. 2020. Prison Population Statistics December 2020. GOV.UK. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/offender-management-statistics-quarterly-july-to-september-2020 (accessed on 26 February 2021).

- Hunt, Kim W. E., and Olivia Solon. 2016. French Priest’s Killer Was Freed from Jail despite Aiming to join jihadis. The Guardian. July 27. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jul/27/teenager-who-murdered-french-priest-was-like-a-ticking-time-bomb (accessed on 28 September 2016).

- Hussain, Serena. 2008. Muslims on the Map. London: Tauris Academic Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Ignatieff, Michael. 1989. A Just Measure of Pain: The Penitentiary in the Industrial Revolution, 1750–1850. Harmondsworth: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Irfan, Lamia, and Matthew Wilkinson. 2020. The Ontology of the Muslim Male Offender: A Critical Realist Framework. Journal of Critical Realism 19: 481–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin-Rogers, Keir. 2018. Racism and racial discrimination in the criminal justice system: Exploring the experiences and views of men serving sentences of imprisonment. Justice, Power and Resistance 2: 243–66. [Google Scholar]

- Lammy, David. 2017. The Lammy Review: An Independent Review into the Treatment of, and Outcomes for, Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Individuals in the Criminal Justice System. London: Lammy Review. [Google Scholar]

- Liebling, Alison, Helen Arnold, and Christina Straub. 2011. An Exploration of Staff—Prisoner Relationships at HMP Whitemoor: 12 Years on Revised Final Report; London: Ministry of Justice, National Offender Management Service.

- Malcolm X. 1998. The Autobiography of Malcolm X, Reissue edition. New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Maruna, Shadd, Louise Wilson, and Kathryn Curran. 2006. Why God Is Often Found Behind Bars: Prison Conversions and the Crisis of Self-Narrative. Research in Human Development 3: 161–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCants, William. 2015. The ISIS Apocalypse: The History, Strategy & Doomsday Vision of the Islamic State. London: St. Martin’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- Micheron, Hugo. 2020. French Jihadism: Neighborhoods, Syria, Prisons. Paris: Gallimard. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Kerry, Paul Mason, and Justin Lewis. 2008. Images of Islam in the UK The Representation of British Muslims in the National Print News Media 2000–2008. Cardiff: Cardiff School of Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Naugle, David K., Jr. 2002. Worldview: The History of a Concept, 1st ed. Michigan: Eerdmans. [Google Scholar]

- Orr, James. 2001. The Christian View of God and the World. London: Regent College Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Centre. 2017. Muslim Population Growth in Europe. Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project. Available online: https://www.pewforum.org/2017/11/29/europes-growing-muslim-population/ (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Phillips, Coretta. 2012. The Multicultural Prison: Ethnicity, Masculinity, and Social Relations among Prisoners. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, Coretta, and Ben Bowling. 2017. Ethnicities, Racism, Crime and Criminal Justice. In The Oxford Handbook of Criminology. Edited by Alison Liebling, Shadd Maruna and Lesley McAra. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Quraishi, Muzammil. 2005. Muslims and Crime: A Comparative Study. Aldershot: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Rambo, Lewis, and Charles E. Farhadian. 2014. The Oxford Handbook of Religious Conversion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rostaing, Corinne, Céline Béraud, and Claire de Galembert. 2015. Religion, Reintegration and Rehabilitation in French Prisons. In Religious Diversity in European Prisons: Challenges and Implications for Rehabilitation. Edited by Irene Becci and Olivier Roy. Berlin: Springer, pp. 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Rushchenko, Julia. 2019. Terrorist Recruitment and Prison Radicalization: Assessing the UK Experiment of ‘Separation Centres’. European Journal of Criminology 16: 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarg, Rachel. 2016. L’expérience Carcérale Religieuse Des Pointeurs, Ou La Recherche Du Salut. Champ Pénal XIII. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarg, Rachel, and Anne-Sophie Lamine. 2011. La religion en prison. Archives de Sciences Sociales des Religions 153: 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneuwly Purdie, M. 2020. Quand l’islam s’exprime En Prison. Religiosités Réhabilitatrice, Résistante et Subversive. In Prisons, prisonniers et spiritualité (Hémisphères Edition). Edited by Philippe Desmette and Philippe Martin. Paris: Hémisphères Editions, pp. 83–99. [Google Scholar]

- Silke, Andrew, and Tinka Veldhuis. 2017. Countering Violent Extremism in Prisons: A Review of Key Recent Research and Critical Research Gaps. Perspectives on Terrorism 11: 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Snow, David A., and Richard Machalek. 1982. The Convert as a Social Type. Sociological Theory 1: 259–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalek, Basia, and Salah El-Hassan. 2007. Muslim Converts in Prison. The Howard Journal of Criminal Justice 46: 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturge, G. 2019. UK Prison Population Statistics. London: House of Commons Library. [Google Scholar]

- UK Gov. 2016. Summary of the Main Findings of the Review of Islamist Extremism in Prisons, Probation & Youth Justice- GOV.UK; London: Minstry of Justice.

- van Nieuwkerk, Karin, ed. 2006. Women Embracing Islam. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- van Nieuwkerk, Karin. 2014. Conversion’ to Islam and the Construction of a Pious Self. In The Oxford Handbook of Religious Conversion. Edited by Lewis Rambo and Charles E. Farhadian. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, Colin, and Mohammed Qasim. 2018. The Effects of Poverty and Prison on British Muslim Men Who Offend. Social Sciences 7: 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, Matthew L. N. 2015a. Complementary Partners or Competing Alternatives? English Law, Islamic Sharia’ and Serious Crime. Presented at the Serious Crime Conference, Judicial College, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK, September 17. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, Matthew L. N. 2015b. A Fresh Look at Islam in a Multi-Faith World: A Philosophy for Success through Education. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, Matthew L. N. 2019. The Genealogy of Terror: How to Distinguish between Islam, Islamist and Islamist Extremism. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, Matthew L. N., Lamia Irfan, Muzammil M. Quraishi, and Mallory Schneuwly Purdie. 2021. Islam in Prison. Bristol: Bristol University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Ryan J. 2018. Islamic Piety and Becoming Good in English High Security Prisons. British Journal of Criminology 58: 730–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Ryan J., and Alison Liebling. 2018. Faith Provision, Institutional Power, and Meaning among Muslim Prisoners in Two English High-Security Prisons. In Finding Freedom in Confinement: The Role of Religion in Prison Life. Edited by Kent R. Kerley. Santa Barbara: Praeger, pp. 269–91. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).