1. Introduction

Those born in present-day Spain, whose Islamic and Jewish history has been concealed from us, have a responsibility to discover our long-neglected authors, the ones who wrote in other languages—Hebrew and Arabic. For centuries, their linguistic and cultural perceptions shaped the ways of life and interpretations of the world that, in conjunction, gave rise to that crucible of knowledge, the Andalusian world [andalusí], characterized by riches and originality. As Fernando Mora says, “It is an ‘old vernacular disease’ to think that our cultural background consists exclusively of texts written in Spanish” (

Mora 2019, pp. 15–29). And it was the Spanish historian Sánchez Albornoz, in his book

Spain: a historical enigma, who declared that Ibn al ‘Arabi is “the personification of a Spaniard”. (

Mora 2019, pp. 15–29). The same can be said of Moses de Leon.

The purpose of this article is to address the subject of investigation within a broad historico-religious context whose written manifestation, as we know from Noah Kramer’s translation of the Sumerian hymns, dates back to the bridal rite of (

Ryan 2008, p. 7) Hieros Gamos

1. To support the thesis of a common origin of the mystics linked to our authors, it is necessary to investigate the symbolic concurrences, exegesis,

2 and the process employed by each of these hermeneutical seekers whose object is to gain access to Supreme Knowledge, in which Sophia plays the primary role.

The present investigation reveals the exceedingly ancient Presence of a Feminine Power of Divinity, as displayed in diverse currents that shaped the many religious, spiritual, and philosophical movements coexisting within Al-Andalus. Within that framework, despite a certain friction, Muslims and Hebrews were able to project their interpretation of spirituality and divine structure into Christian mystical theology, where it gave rise to a powerful and unique way of Knowledge whose originality consisted in the vision of a force emanating from the celestial order. This emanation results in a differentiated polarity that includes, yet transcends, the amorous entanglement that leads to an encounter with Unity. It is thus that a sort of irruption occurs within Hispanic mystical life, where the figure of Sophia linked to Love acquires enormous power and a singular means of expression. It is proposed to describe this original manifestation within the borders of Al-Andalus, focusing on the intimacy generated between the seeker and the Creative Force and on the ways in which this encounter is described in the three languages linked to the religions of the Book: Arabic, Hebrew, and Spanish. Underlying the Presence and manifestation of the Creative Force (known by various names, and to our authors as Ibn ‘Arabi’s,

Himma, Moses de León’s,

Shekhinah, and St. John of the Cross’, Wisdom), is the Science of Letters,

3 the knowledge of harmonic sounds, number, and sacred mathematics.

That said, the goal of this work will be to highlight the equilibrium of the Divine, the celestial hieros gamos that is projected into the human soul and into the Creation in a continuous circular flow, embracing differences and weaving them into a single manifestation that reflects, like a mirror, the unsayable.

The hypothesis is that diverse mystical paths suggest the existence of a universal entanglement that can be discovered by apparently divergent pathways, all leading to a common goal: intuitive, noetic knowledge. To those who undertake the voyage into uncertainty, Sophia grants this particular kind of knowledge in the form of Light. The current proposal will emphasize the original Unity, the power of the Cosmic Eros that guides the enamored soul toward an “experience” that takes place in dimensions of reality beyond time and space, incorporating harmonies and discrepancies, encounters and dis-encounters that emerge in an intermediary world between the spiritual and the material: the world of the soul.

It seems essential to investigate, beyond an anthropocentric and unidirectional vision, the relationship of the human being with Longing, with the Presence of a mysterious

Saudade,

4 and definitively with the seductive figure of Sophia, who precipitates those who “suffer” from love-sickness into another dimension. This perspective will necessitate a search for cultural variations in varying contexts, perhaps even a sacred language that connects us to all the inhabitants of the universe, in an attempt to reveal the common indicators underlying the diverse interpretations and expressions and their hidden messages. Something is summoning us, challenging us, calling attention to the paths that coincide with this search, to the convergence of itineraries that guides us to the fulfillment of a lack. The present study will examine, in short, the common threads and concurrences that speak to us of a community formed around the sacred lineage of gnosis, which inhabits a very particular spiritual and contemplative cartography. Despite the diversity of perspectives and historical or cultural dissonances, it calls our attention to the sense of a universal gnostic communion. As the Murcian Sufi Ibn ‘Arabi reminds us, the mystic souls of all historical epochs live out the same spiritual experience, though conditioned by the diversity of beliefs, by religious plurality. This diversity gives rise to what the

Sheikh denominates as “the god created through the creeds”, which is inevitably problematic, since according to a proverbial saying: “There are as many ways to God as there are human souls” (

Chittick 2003, p. 7). It is precisely Ibn ‘Arabi who emphasizes the diversity of opinions (

Chittick 2003, pp. 8–9) (

masʼala jilāf) that, according to him, has been established by the working of the divine

Wisdom and

Compassion; as he points out, “God himself is the source of all the diversity in the Cosmos” (

Chittick 2003, pp. 8–9). Consequently, the Murcian master considers all creeds, even the discordant ones, as emanating from the same god, since they, as well as the variety of methodological perspectives, all contribute something vital. It requires only a certain effort to distance ourselves from our habitual epistemological framework in order to situate ourselves on another plane on which, according to the professor Teresa Oñate y Zubia, there occurs the coupling of differences, of masculine/feminine, light/darkness, above/below, dense/subtle.

When considering the mystical phenomenon within the geographical boundaries of Spain, Federico García Lorca’s writings on duende are indispensable. It was the great Andalusian poet and dramatist who delineated the particular characteristics of the creators and seers native to this terrain in terms of their connection with duende, an overwhelming, indescribable, and irresistible Presence. This duende is nothing less than the relevant, magical divine feminine power that emerges in the texts of these Spanish mystics, leading through Sophia and her Wisdom to an intimate and theosophical encounter.

Thirteenth-century Spain experienced a very particular outburst of the mystical phenomenon, and any attempt to decipher the key points of the spiritual paths that channeled it demands the closest observation of the poetic and hermeneutic word, bearer of life yet foreign to rational discourse. A notable example would be the language of St. John of the Cross, where something that at first seems like nonsense turns out to be a cipher, a symbol, a key to unknown gateways and dimensions. Through this riddling use of language, the saint explored differentiated planes of reality: imaginal worlds, as in his Strange Isles

5 (Ínsulas Extrañas), or topographies of the frontiers where we find a phenomenology pregnant with sightings, revelations, locutions, visions, and other portents peculiar to the alchemical transmutation experienced by the Gnostic. These experiences foment the emergence of poetic language, allegory, and symbol, essential vehicles of a shared, alternative way of knowing linked to

noesis.

6It is also necessary to consider other texts, far removed in time, in which we detect antecedents and fundamental parallelisms and where we confront reflections on Wisdom, that universal, millenary notion that penetrates the Hispanic theology of the Sufi, Hebrew, and Christian mystics. In examining the origins and later development of a certain sacred transcendent polarity, one discovers that complementary categories replace the oppositional ones, effecting, a conciliatory coupling that is projected through various manifestations and leads at last to the achievement of a goal common to all three “mystics of the Book”: the Perfect Human Being. This Hispanic “symbolic nuptial process” is clearly opposed to the Rhenish “mystical theology of the essences”, although some of its aspects—like those related to the Unsayable and Unthinkable, that Nothing that is Everything, the Divine Darkness of Dionysius the Areopagite may occasionally converge. Varying linguistic and cultural codes account for the disparity between particular approaches, but it is evident that these mystics are following parallel, not divergent, routes. Their discursive results, occasionally influenced by dogmas and theologies, arise from interpretations of their sacred texts.

The Hispanic mystical paths are diverse (centuries later the Sufis and the adherents of the Kabbalah were to contribute to the Christian mysticism of St. Teresa, St. John of the Cross, and Miguel de Molinos); however, all refer to biblical texts, sometimes amplified by millenary currents already evident in the Sumero-Akkadian hymns

7 whose defining characteristics were perpetuated in the

Song of Songs. The metaphors, analogies, and double meanings of that supreme example of an erotico-spiritual text were in turn reflected both in the

Tarjumán al-Ashwáq (

The Interpreter of Desires) of the Murcian

sheikh, Muhyiddin Muhammad Ibn al-Arabi (الطائي الحاتمي عربي بن محمد بن علي بن محمد الله عبد أبو, Murcia, 28 July 1165-Damascus, 16 November 1240), and in the

Zohar attributed to the Spaniard Moses de León (?1240—Arévalo, 1305), known in Hebrew as Moshe ben Shem-Tov (משה בן שם-טוב די-ליאון). These texts describe the milestones of a spiritual journey with a common goal: the Union of the seemingly diverse, which is attained after an extremely personal itinerary that proceeds through dwellings, steps, stations, and wine cellars before arriving at Ibn ‘Arabi’s “Dwelling of Non-Dwelling”, or at the

Zohar’s “Opening of the Eyes”, a station similar to the Seventh Wine Cellar of St. John of the Cross. In these mystics, this entire process is conveyed through an array of connections, attributes, categories and Names that contain a multitude of meanings in which it can be detect echoes of not only the

Song of Songs8 and other biblical texts but of the Sumero-Akkadian Hymns (3400 B.C.) whether anonymous or attributed to the Akkadian priestess Enheduanna (2285–2250 B. C), in which the transforming Feminine Presence of the Divine plays a central role.

2. Spanish Mystical Theology: A Mystical Theology with Duende

What is

duende9? Only someone who is conscious of its Presence, which dwells in the heart and liberates the creative force that is inherent to it will be able to decipher

The Interpreter of Desires, the

Zohar, and

The Spiritual Canticle. Duende seizes on the mystic writer and on the poet, emptying the heart of refletive thought.

Duende is related to the Socratic

daimon.

10 It pillages the soul and obliterates meaning, yet preserves the logic of reason even while transcending it, leading to the emergence of a “poetic rationality”, as María Zambrano once maintained (

El Hombre y lo Divino, Filosofía y Poesía). It is thus that Spanish philosophy, poetry, and symbolic texts invoke an obscure depth inhabited by the divine, the home of

duende. Poetic Reason understands truth not as an adjustment to the facts of physical reality, but as revelation. Therefore, when mystics or poets communicate their revelation in writing, what occurs is the unveiling of a symbolic, transcendent truth from personal experience, destined to attain “the universal”: the Unity of Being. As Zambrano says, poetic reason is a “half-awake thinking”. It belongs to a liminal space in which the human being is neither awake nor asleep. That topography corresponds to the imaginal world, which the “pilgrim” enters by way of the kingdom of Intermediary Being.

As previously indicated, the supreme theorist of the Hispanic

duende was Federico García Lorca (

Farré 1998, p. 82), who outlined his theory in a conference he gave in Buenos Aires and Havana in 1933. We defer to him. Our great poet reflects very beautifully and poetically on the notion of

duende, an idea linked to the Spain of a sensitive, poetic, impassioned, and overwhelming sentiment. It is normal, in reference to Lorca, that in referring to any splendid and sublime artistic creation one says, in our country, “it has a lot of

duende” (

Lorca 2003). The author of

Blood Wedding puts these words in the mouth of Manuel Torres, who, after hearing Manuel de Falla’s interpretation of his

Nocturno de Generalife [Nights in the Gardens of Spain], pronounces this magnificent sentence: “Anything that sounds dark has

duende” (

Lorca 2003). And listening and darkness always accompany

duende, as they do those mystic states in which light is born out of darkness to the accompaniment of the harmonic sound of silence, the “sonorous silence” of St. John of the Cross. García Lorca (

Lorca 2003) notes, in this sense, that “these dark sounds are the mystery, the roots sunk in the mire that we all know and we all ignore, but from which we receive everything that matters in art”. He is referring to the hidden place that Gaston Bachelard (

Bachelard 2000, p. 40) describes as “the sub-basements of the soul”. That unknown place, that point within the heart, is the dwelling of every soul that allows itself to be penetrated in solitude by a “mysterious Power that everyone feels and that no philosopher can explain” (

Lorca 2003).

This is the power that raises the indigent human from hearing to vision, and bestows on the pilgrim the eyes of the Creator, in a Return that deprives the sentient being of action and conceptual discourse. Thus, darkness, hearing, and mystery correspond to their etymological meanings: ὰ-μαυρόζ (invisible, somber, obscure, blind); ἀκούω (to pay attention, to hear a call, to be put to the test); and μυστήριον (arcane, secret, secret doctrine, secret cult).

Duende assumes the function of a power receptive, obscure and mysterious, feminine, impassioned, committed, and creative. It remains remote from any action except those that provoke a rebirth deriving from an inner trauma, and in the process of rebirth, it destroys the self, which is annihilated by its seductive and demanding potency. It is a receptacle, a goblet whose contours are greater or lesser according to the content of the stored-up force and its insistent pulsations. Consequently, for the poet from Granada, “

Duende is a power and not a labor, a struggle and not a thought”.

Duende, he says, “is not in the throat (from which sounds emerge): it rises inwardly from the soles of the feet” (

Lorca 2003); and, as can be observed, it bursts forth in a delirium of song, poetry, and celestial harmony unrelated to earthly human concordances. Although it operates in a realm beyond the mundane, nevertheless, through an irradiation of the Good and the Beautiful, the Presence of this force alters the nature of the most ordinary experience. From this point of view, one can speak of a relationship with the transcendent in terms of love and passion.

The

duende whose summons Lorca so eloquently describes resonates throughout Spanish mystical theology: vibrant, enigmatic, hermetic, and seemingly incoherent. For each individual, it is unique, inviting us to different paths, as many as there are human souls.

Duende makes use of an obscure, audible, and mysterious desire, manifesting through signs engendered by Sophia. Anyone capable of capturing something of its excessive force trembles before it. In order to understand texts produced within this state, we need a symbolic hermeneutics whose goal is “festival”, in the sense defined by Hans Georg Gadamer in

Truth and Method and

The Beauty of the Word. The sacred word is a milestone on the path, leaving coded messages; it sidles downward to the crypts of the soul along a spiral staircase that descends in a serpentine path towards the darkness where light is most concentrated. Undertaking this risky descent, the pilgrim discovers that it is, astonishingly, an ascent (see

Kingsley 2016) toward an encounter within an “inner Castle” (Saint Thérèse of Avila.), which harbors a diamond, in a

Templum, a palace of perfection, reached through states and stations or dwellings. In this displacement toward the heights of oneself, the

duende, the Socratic

daimon, impels the traveler who, like Odysseus, must pass the stormy seas in order to reach home: the point of origin, the Unity. It is not free from suffering, this voyage, because it requires a stripping away, a total abandonment, even of the ego itself, in order to reach, egoless, annihilated, the primordial I, the

Jungian Self.

Duende knows the instant because it occurs within it. It emerges from an eternal un-time and interrupts chronological succession. Its Presence irrupts in the

Kairós, an “opportune” time. Tearing the human being away from the known self, it suspends the quotidian, revealing subtle pathways that bifurcate in search of the bridegroom: God. Some of these pathways penetrate into an imaginal, intermediary world, the

barzakh, in which, as Ibn ‘Arabi (who, like Moses de León, was familiar with the Science of Letters) tells us, “the bodies are spiritualized and the souls materialized”. Alternatively, they may travel through “Strange Isles” (as St. John of the Cross suggests) thanks to another “science of words”, the sonorous play of alliteration; or they may end up conforming to an almost Riemannian geometry,

11 the Tree of Life, related to a sacred mathematics of the word, an alpha-numeric code known as Gematria,

12 as Moses de León insinuates.

Duende invariably arrives spontaneously, at just the right moment, when the ground has been prepared and the ego has learned to let go of itself, as the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa (1888–1935) informs us through the heteronymous master Alberto Caeiro (

see Pessoa 2001, p. 82).

Duende cannot be invoked; it lays down no pathways; it simply bursts forth, transmitting to the subject who experiences it, in the words of Kierkegaard (1813–1855), “a searing atom of eternity”. In this respect, Federico García Lorca (1898–1936) writes, “One only knows that the blood burns as if inflamed by an embrocation of broken glass, that

duende exhausts, that it rejects a gentle, familiar geometry, that it disrupts styles” (

Lorca 2003). The arrival of

duende is closely related to death, a death in life, since, as the poet from Granada tells us, “

duende won’t come without the possibility of death, if one doesn’t know that it is already prowling around one’s house, if one isn’t sure that it will shake those branches that we are all carrying and leave us inconsolable” (

Lorca 2003).

Duende is attracted to the very edge of the pit, in open war with the creator (

Lorca 2003). It moves through a horizon of events, bearer of the mystery of a “naked feminine and re-creative singularity” that inhabits every soul. Spain, says García Lorca, is the only country in which “death has become a national spectacle, where death greets spring with long bugle calls, and its art is always ruled by a heightened

duende that renders it distinctive and inventive” (

Lorca 2003). Death comes to the lovesick, the wounded heart. St. John of the Cross says, “Love is like dying”. “The wound and dying are two ways of suffering death” (

Cruz 2002, Cc. 7: 3,4,5, pp. 764–65).

Appropriating an expression of Lorca’s, and referring to Saint Thérèse of Ávila, it can be affirmed that the Sufi master Ibn ’Arabi of Murcia, the Hebrew Moses de León, and the Christian mystic St. John of the Cross, were all “

in-

duended”, possessed by

duende, enamored of an unsayable that summoned them through that indescribable impulse: the desire that awakes Eros in all of creation. There is an extract in the

Zohar that speaks, like the

Song of Songs, of a “Love strong as death, hard as the parting of the soul from the body” (

Laitman 2015, p. 204), and that severing presupposes a lack, a longing, a discontent, a fatal attraction that impels the human being beyond reason and disjunctive logic. Love has wings, it raises its creatures above the everyday; it delights in risk, accepts suffering, leads to the invisible, brings upper and lower worlds into conjunction. And the “kiss of Love”, in one paragraph of the

Zohar, is said to “expand in the four directions and the four directions join together and unite” (

Laitman 2015, p. 204). That death accompanying a spiritual journey, in Ibn ‘Arabi’s (

Chittick 2003, pp. 70–71) opinion, presupposes the abandonment of characteristically human limitations, so that the individual becomes “erased”, or in the words of St. John of the Cross, “effaced”, and within that “annihilation”, nothing remains, according to Ibn ‘Arabi, except the face of the

Wujud (

Chittick 2003, pp. 70–71), turned toward the Creation.

Lorca asks, And where is Duende? “Through the empty arc there enters a mental breeze that blows insistently over the heads of the dead, searching for new landscapes and unknown accents: a breeze that smells of a child’s saliva, of bruised grass and the stinging medusa’s veil, that announces the continual baptism of newly created things”.

In sum Ibn ‘Arabi, Moses de León and St. John of the Cross are captives of a duende that speaks of dying of love, of surrender and personal extinction. That is the only way to understand Ibn ‘Arabi’s nocturnal “Journey to the Lord of Power”; the Zohar’s “Opening of the Eyes”, the “I die of not dying” of St. John of the Cross, and Santa Teresa’s “I live without living in myself”.

3. The Supremacy of the Mystical Nuptial: Antecedents

The Great Queen (NINGAL) of queens born for the rightful Me,

born of a fate-laden body,

you are even greater than your own mother,

full of wisdom, foresight, queen over all lands,

who allows existence to many,

I now strike up your fate-determining song!

All powerful divinity suitable for the ME,

That which you have said magnificently is the most powerful!

Of unfathomable heart, oh highly driven woman

of radiant heart, your ME, I will list for you now!

The texts of ibn ‘Arabi’s Interpreter of Desires and of the Zohar attributed to Moses de León contain ancient wedding images derived from the cult of the Feminine Power of Divinity.

The first written testimonies of the heavenly wedding and its projection in the earthly order are originated in Sumer. The mythico-theosophical system of Mesopotamian and Egyptian religions, which was inherited by the Mediterranean culture, consists of an internal structure based on a reconciliation of sexual polarities. Therefore, at the heart of the divinity there is a dynamism imbued with eroticism and seduction. The channels established between the higher worlds and the one inhabited by created beings are generated by the projection of that bi-directional desire. True, the disparity and diversity of the models, as well as cultural tensions and their conceptual complexities, display remarkable differences, but from the Hispanic perspective, the most striking phenomenon is the existence of several paradigms of mystical eroticism that share a common theme: the Union of the Holy (masculine), with its Divine Presence (feminine).

To establish this fact, it will be necessary to return to the primal origins of the feminization of an aspect of the Divinity related to desire, love, and the creation of the universe; and which is, in addition, the depository of the laws that govern it. Noah Kramer’s works,

The Sacred Marriage Rite (

Wolkstein 1983, p. 62),

History begins in Summer (

Kramer 2010), and

Inanna Queen of Heaven and Hearth (

Kramer and Wolkstein 1983, p. 107), contain numerous poems about the courtship of the Sumerian goddess Inanna and her betrothal to her husband Dumuzi, as well as accounts of the deity’s descent into the Underworld (“Inanna and Dumuzi”, “Inanna queen of heaven and hearth”). While the first cuneiform texts describe the earthly erotic tensions of the nubile goddess, in those hymns that depict her journey to the underworld the divine Inanna, in her maturity, is obliged to pass through seven successive gates. To gain passage through each one, she must abandon something precious to her, until at the last she remains totally naked and silent, as the laws of the underworld are implacable. Nothing remains in her heart except an intense desire for rebirth. In this poem we find the three characteristic phases of the female power: the young woman, the mature woman, and the crone. These three figures could be correlated, in turn, with the three Marys of the Gnostic Gospel of Philip and with the three

Seefiroth of the

Zohar’s Tree of Life: the Mother,

Binah; the wife,

Tiferet; and the daughter,

Malkuth.

In the case of St. John of the Cross, there are also three female representations: the Soul (

Spiritual Canticle); the Church (

Romance 4; pp. 150–55) (as the bride of Christ, similar to the Community of Israel,

Keneset Yi-ra-el); and Wisdom herself (

Spiritual Canticle), associated with a higher realm, the breath of the Holy Spirit. This indicates the fundamental importance of these ancient bridal images in the development of a Hispanic mysticism that incorporates the three currents that demarcated the relationships between God and human beings. The entire mystical journey is oriented toward that encounter, the union of opposites, which—despite the various forms it may assume—is never destructive. Instead, it consists of a harmonious entanglement on an equal plane (

Cruz 2002, Cc.26,5–13;16–17, pp. 842–47) or even of a reversal of roles, as St. John of the Cross’ commentary on the

Spiritual Canticle demonstrates (

Cruz 2002, Cc. 27,1, p. 848).

In this respect, it is appropriate to add that, contrary to current opinion, parity between the two celestial polarities was quite common in the religions of the near East, and markedly so in primordial erotic relations. At the same time, we note a strikingly explicit description in the

Sefiroth of the Tree of Life in the

Zohar (see

Section 5 of this article), in that the male projections of the right branch of the Tree may at some point take on a female role or vice versa, so that the amatory functions are often interchangeable, which indicates that there is no radical separation of “genders” in this matter. Something similar occurs in the texts of St. John of the Cross

13 in relation to the figure of Wisdom, which sometimes resembles Christ. As for Ibn ‘Arabi, he draws no distinction between the Lord and the Lady (

Corbin 1958, p. 109).

In regard to the historical background, and in accordance with Moshe Idel and other researchers, there are grounds for questioning Gershom Sholem’s nationalist thesis which asserts that the divine feminine and creative principle (the Shekhinah of the Kabbalists) first assumes her role at the birth of the Kabbalah. On the contrary, its suspect that it is the contact sustained between the Hebrews and the Sumero-Akkadian culture after the Babylonian exile that explains why the figure of the hieros gamos, in which the amorous female power assumes a leading role, is so deeply imbued in the biblical Song of Songs. That text, in turn, retained an indisputable authority for our three Hispanic mystics. Consequently, it is possible to affirm that the amatory progress derived from these pathways of Spiritual Knowledge clearly originates in the Sumero-Akkadian compositions that inspired the supremely erotic biblical outpouring of the Song of Songs, as well as the remarkable references to the mystical wedding in the Hispanic spiritual traditions linked to the three religions of the Book. As for the distinctive role of the feminine in both the 13th-century texts of the Interpreter of Desires and the Zohar and in the 16th-century Spiritual Canticle, from the Middle Ages onward there is a parallel preeminence of women in western mystical traditions that should not be overlooked.

Arthur Green (

Yom et al. 2006, p. 350) defends the unmistakable feminization of the

Shekhinah14 in the Kabbalah of the thirteenth century, as a Jewish response to the heyday of devotion to Mary in the Western Church of the time. This inevitable transfer and mutual influence might explain, in part, three of the most striking creations of our Hispanic mystics: the powerful representation of the

Zohar’s Matronita (

Patai 1947); the projection of the feminine divine in

Nizam (Harmony) in the

Interpreter of Desires; and the central role of Sophia, which penetrates both creation and the soul in love in the texts of St. John of the Cross. In the prologue to

the Interpreter of Desires,

Tarŷumān al- Ašwāq, the Murcian Sufi master relates an encounter with the divine feminine (

Arabî 2002, pp. 16–19) during one of his circumambulations in Mecca. This apparition gives rise to a cryptic conversation that inspires the first qasida of that mystical-erotic poem. As Carlos Varona (

Arabî 2002, pp. 16–19) has emphasized, the composition is organized around the axis of the female protagonist. In fact, the beloved

Nizām (Harmony), protagonist of the epithalamion, manifests as an epiphany, a tangible reflection of the unnamable and unsayable Here we have an example of a process in which divinity is revealed by the “emanation” of “celestial archetypes” (

Arabî 2002, p. 16). By means of this revelation, indescribable spiritual forces take form and become embodied in creatures. From then on, this process enables Love to attain to the condition of a bearer of “knowledge” (

Arabî 2002, p. 101), and “the lover/beloved becomes the paradigm of a beauty beyond comprehension” (

Arabî 2002, p. 19).

Just as in Sumer, in the

Zohar the “face-to-face” sexual relationship is exalted. Luria (

Yom et al. 2006, p. 77) suspects that this is the basis of a cosmogonic principle of continuity that is accessed through Wisdom, itself a transformative genesis. Ibn ʿArabi sustains this same principle, as he avows that “creation is continuous and occurs at every instant, renewing itself” (

Chittick 2003, pp. 52–53). In the case of the Sufi master, this convergence between the masculine and the feminine is the cause of a “constant metamorphosis”, an alchemical transmutation of the self; therefore, it is also responsible for the continuous and “endless fluctuations” suffered by the heart (

qalb) and experienced by “perfect human beings” who are subjects of a “self-revelation that is never repeated” (

Chittick 2003, p. 52).

The same can be said of the prodigal compliments and laments uttered by the bride, (the soul) in the

Spiritual Canticle, where she takes the initiative, just as in the

Song of Songs. In his commentary to songs 4 and 5 of the

Spiritual Canticle, St. John of the Cross exalts the divine creative act, telling us, in his exegesis of these poems, about the path to Knowledge, which springs from “a concern for creatures” (

Cruz 2002, Cc. 5,1, p. 760). This concern arises once the human being has descended/ascended “to the infernal regions”, and has acquired self-discernment, a process of rebirth/re-creation described in the

Ascent to Mount Carmel. The saint places it above all things, saying “this concern comes first of all, on that spiritual path of a progression toward the knowledge of God” because of “his greatness and excellence” (

Cruz 2002, Cc. 5,1, p. 760).

In the

Zohar as well, both the descent of the divine and the human ascent driven by the desire for union involve passing through several steps,

Sefiroth, which act as screens or veils of the Light of the Creator. Ascending to know oneself, through those ten steps, during which the obstacles that prevent true

sight are removed, also implies “being born at every moment of the process”. This “birth at every moment”, both of God in human creatures and of the creatures in God, is a consequence of the desire for transformation implanted by the Creator in order that the intensive point sheltered in the heart of the desiring self should be unfurled until it attains its goal: the perfect human being, free of restrictions and prejudices, free of self. That is the object of the spiritual path. For all three mystics, it marks the end of all “correction” and re-creation. In the texts under consideration, the “Creation”, or rather the “re-creation”,

autopoiesis, is the result of a divine, feminine, and mysterious exhalation through which a willing, speaking, and living God is revealed through theophanies. Accepting this premise leads us to a new “re-enchantment of the world”, to a sacrificial dimension that implies the abandonment of self, by the hand of

Sophia, in order to “die” into the primordial Self. This knowledge implies the perception of a state of equilibrium between the two functions of divinity, which in turn permits all creatures to respond to the soul with sympathy, “overflowing with thanks”, and “bearing witness”, as St. Augustine says, “to the greatness and excellence of God” (

Cruz 2002, Cc. 5, 1, p. 760).

The celestial marriage, the hieros gamos, descended to Earth and denoted the union between the upper and the lower worlds. In this way, two potencies combined to guarantee the order of the city and of the universe in a bi-directional movement of ascent (the human being) and descent (the divine). The driving force of this metaphysical dynamic was desire, brother of death, borne by the goddess who let her heart lead her along a path from which no traveler returns. The poet who speaks to us in the

Descent of Inanna to the Underworld describes the seven levels of knowledge, which correspond to a host of other dwellings, stations and interior wine-cellars (

Cruz 2002, Cc. 26, p. 842) celebrated by our mystics. The first line of the poem

The Descent of Inanna says: “From the Great Up she directed her mind to the Great Down”, and to the question that the poet Dianne Wolkstein asked N. Kramer: “What exactly does ‘mind’ mean?”, he replied, “Ear”, adding that in sum, the words “heard” and “wisdom” mean the same thing. “From the Great Up the goddess, ‘opened her ear,’ the recipient of wisdom, to the Great Down” (

Wolkstein 1983, p. 5). Inner hearing and vision, assume the function of senses that contribute knowledge, giving way later on to prophecy and to visionary states. In Sumerian, then, the “ear” is equivalent to Wisdom and this Wisdom is transmitted precisely through “auditions” and “visions”, fundamental theosophical devices in the works of Ibn ‘Arabi, Moses de León, and St. John of the Cross. The

Song of Songs recapitulates many of the metaphysical figures and symbols of the Sumerian accounts, full of mystery and seduction, such as the gallantries between the spouses, kisses sweet as honey, references to the orchard, to the bridal bed, and particularly to the initiative assumed by the wife. Today, the influence of this biblical text on the mystical vision of Ibn ‘Arabi, Moses de León, and St. John of the Cross is widely acknowledged.

15A reaffirmation of the deity’s power and her entanglement with the male aspect, topics that will recur in later bridal mysticism, is reflected in the hymn of Inanna and the God of Wisdom, topics that will recur in the later bridal mysticism. Thus, we see that the divine Inanna assumes the role of Queen of Heaven “in equality” with Enki, God of Wisdom, who, having “drunk beer” with her, imparts to the Queen (who is both his wife and his daughter) “the secrets”: the seven Mé that generate the order of the creation (

Kramer and Wolkstein 1983, pp. 101–3) The “journey” of ascent to Heaven also implies a descent, to the

Abzu, the lower regions. “Water”, as a

source of life, receives prayer. “Hearing” (

Cruz 2002, Cc. 14–15, pp. 793–97) is linked to knowledge. The “

festival” derived from the “intoxicating union” implies, in turn, the surrender of her crown, the giving up of all her powers: The poem says (

Wolkstein 1983, p. 10),

I, the Queen of Heaven, must visit the God of Wisdom(...)/I must honor Enki, the God of Wisdom, in Eridu./I must say a prayer in the deep fresh waters (

Idel 2009, p. 248).» “He, whose ears are widely open, He, who knows the Me, the sacred laws of heaven and earth, Enki, the God of Wisdom, who knows all things (…)

As we can see, the goddess assumes a primary role in everything pertaining to Knowledge. The feminine presupposes creative action, dynamism, movement, and the deployment of Wisdom, gifts ceded by the god Enki, husband and father. Similarly, in

Proverbs 8, 22–30, there is an explicit reference to the timelessness of the feminine aspect of divinity.

22 Aren’t you calling WISDOM? (…)

From the beginning, the Lord possessed me;

from before his works began.

30 I was next to you, ordering everything,

dancing joyfully every day,

always enjoying its Presence.

The “idea” of beauty linked to Wisdom exercises a theophanic function, and it is this intuition that gives rise to the Feminine Creator, where the spiritual and the sensitive converge. As it is already well known, these Platonic texts were adopted by Neoplatonism, a philosophical current that permeates the Tūryuman, the Zohar and also the Spiritual Canticle, insofar as it regards the role of divine emanations, which in these texts are linked to the knowledge that Wisdom bestows on the traveler, the seeker.

4. Ibn Al ‘Arabî: The Interpreter of Desires: Tarŷumān al-Ašwāq

My heart can assume all forms: a pasture for gazelles, and for the monk a monastery/It is a temple for idols, a Ka’aba for the pilgrim, the Tablets of the Torah and the book of the Qur’an/I follow only the religion of Love, and wherever its camels go I take that way, for Love is my only faith and my only religion.

Although Ibn al ‘Arabi, also known as the “the teacher” and dubbed the “Red Sulphur” [aš-Šayj al-Akbar wal-l-Kibrit al-Ahmar], is the author of more than 350 works, one of his many poetical productions deserves separate mention. We refer to The Interpreter of Desires [Tarŷumān al-Ašwāq], whose intimate congruity with the Zohar and the Spiritual Canticle lies precisely in the preeminence of a “mystical wedding” in which the feminine aspect of the divinity plays a leading role. Reynold A. Nicholson translated this work into English in 1911. Later, in 1931, the Arabist Miguel Asín Palacios published his Christianized Islam: a study of Sufism through the works of Abenarabi of Murcia, which marks the beginning of a consideration of the convergence between The Interpreter of Desires and Christian mysticism.

Professor Luce López-Baralt also certainly associates the

Canticle with the

Interpreter of Desires.Writers like St. John of the Cross and St. Thérèse of Ávila—to mention only the most exalted figures—reveal an astonishing consanguinity: they share many of their symbols and their most important esoteric mystical language with their Middle-Eastern counterparts. From a literary point of view, this is extremely significant, as it implies that numerous references in the vocabulary of these two Christian saints must be sought among the Sufis. We are faced with the phenomenon of a European literature with numerous literary keys that originate in Arab, and even Persian sources.

The

Tarŷumān al-Ašwāq consists of 61 poems, qasidas [kasîdes], which the author himself deciphered in an interpretative key to a commentary on it [

al-djhajā ir], where he clarifies some of the symbols and names. Like St. John of the Cross, Ibn ‘Arabi performed an exegesis of his own work, which makes it somewhat easier to comprehend. The text, preeminent within the amatory poetry of Muslim spirituality, belongs to the category of epithalamia or love lyrics, part of the cult of beauty. As in the

Song of Songs—similarly preeminent within Judeo-Christian wedding mysticism—the poem’s plot revolves around a journey through complex geographies. It too is full of amorous nostalgia, intense sensations, laments for the flight of the beloved (the beautiful

Nizām), states of intense dejection caused by separation, fleeting encounters, an urgent and longing search that follows a trail full of premonitory signs: birds, winds, mountains, trees, aromas, shops, fountains, roads, caravans, dunes, mirages, flowers, gazelles, fire, gardens, rain, lightning … It is within this atmosphere that the celestial archetypes manifest, leading on to Knowledge through Love and desire and impelling the seeker to continue the search. She, the Beautiful One, subjugates the enamored traveler, seducing him through fleeting glimpses. Her elusive Presence is located between light and darkness, leading Her pursuer through a world of contrasts and indistinct appearances:

Even at night, we are next to Her in the light of day/and through the locks of her hair the night turns to day.

This poem is as sinuous and difficult as the

Zohar and

The Spiritual Canticle, and like them, it reflects the painful soliloquy of an amorous soul, the soul of the pilgrim exiled from himself who wishes to apprehend an indefinable Reality: the Beloved. The text proceeds through a plethora of devices: symbolic codes, gnomic and knowing allusions that are suggestive rather than definitive [

Isāra]; intimate events expressed through external and literal references [

Ibāra]; obscure locutions (

Arabî 2002, Cas. XXIX-8, p. 22) in which the hidden sense of words [

bâtin] begets the existence of other, unfamiliar scenarios where words full of subtle nuances [

latīfa] preside, scenarios that allude to realities [

haqῑqa] even more substantial than those operative in everyday life. All of these factors complicate the poem’s interpretation, even for philologists who are experts in the Arabic Science of Letters

16. It seems appropriate, therefore, to apply a spiritual hermeneutics [

tawîl] in accordance with the revelations inspired by it. This is how the word acquires an existence beyond language, and the poet, an interpreter of himself, is inevitably overcome by what he intends to say.

The experience of an unsatisfied longing leads the author to describe an intense amatory process, a journey through “a shoreless sea” (

Arabî 2002, p. 67), during which a restrained force seems to overflow the words themselves. Still, it is through words that he attempts to reveal the discovery [

kašf] bestowed by an inner vision [

basira] conferred by Wisdom [

hikma], which becomes Presence [

hadra], thanks to which it is possible to taste [

dawq] a deep essential spirituality [

rūbāniyya]. It is this deep spirituality that gives access to the secrets of an enigmatic Reality represented by the figure of a young Persian woman, [

Nizām], an immaculate virgin. She is a true theophany of the Absolute, a prodigious and beautiful maiden suspended between reality and the interstitial world of creative imagination to which Ibn ‘Arabi as the Sage, [

Šayj] devotes verses of the highest mystical and symbolic tone. It can be deduced from these words that the true spiritual lover loves with both body and spirit, rejoicing in “the love of the seer, not of the blind” (

Arabî 2002, p. 34), It follows that this love “with the entire being” embraces “the entire being of the Beloved”. In his

Dhakari-al-a’laq (

Treasure of the Enamored), an interpretative introduction to the

Interpreter of Desires sponsored by his followers, Ibn ‘Arabi sets out to counteract the implicit danger of a literal, erotic-amorous interpretation of his verses, insisting explicitly (

Arabî 2002, p. 99), that the events described were actually experienced. That is, he speaks about an intimate experience replete with such senses as taste [

dawq], inner vision [

tabassur], and hearing, associated with the creative word [

kun].

It is precisely this inner vision that allows the opening [

futuhat] of gateways to another world, an imaginal universe [

alam al mithāl] linked to an intermediate plane of reality, the Isthmus, [

barzaj], a dimension in which there is a convergence of the corporeal senses with that which transcends them. This is also the site of theophanies and revelations, not unlike the

Strange Isles described by St. Jhon of the Cross. The qasidas radiate an elevated symbolic and gnostic content in which it is necessary to highlight the poet’s interpretation of the unique transcendent, personal, and non-transferable experience deriving from a theory of “seeing” Knowledge inspired by theosophical forms [

maz-hir]. As Henry Corbin maintains (

Corbin 1958, p. 13), the poem emphasizes the transmutation of the visible world into symbols. The intuition of “something” occurs in an image that corresponds neither to a universal logic, nor to an entity endowed only with earthly senses. Therefore, the symbolic plane refers us to a differentiated dimension of consciousness; it reflects the cipher to a mystery, the only means of saying what cannot be apprehended or explained. The mystery can only be deciphered, and consequently postulates an esoteric knowledge wholly foreign to ordinary evidence. In these qasidas full of antinomies (

Arabî 2002, Cas. XXIX, vs. 7, p. 238), paradoxes, contradictory and oscillating sentiments, Ibn ‘Arabi describes a spiritual journey along a path that introduces the traveler step by step to a sacred vision of the cosmos that unifies the multiple dimensions of being in a search for the Eternal Feminine: Wisdom. The tracks, the traces, the signs that the Beloved leaves along the way [

išārat], are clues that lead the traveler on towards the goal. These will inevitably differ according to the nature and disposition of the pilgrim, who searches for shortcuts and follows the signs without lingering overlong in the successive states [

hal] and stations [

maqamat].

The axis of the poem lies in the encounters and dissonances provoked by the fluctuations, absences, and Presences of the Beloved who cannot be seen by human eyes, but beheld only by a supra-sensible apprehension: “Human sight does not reach Him (…)” “It is subtle (…)” (

Koran 6,103). The mystic is valiantly seeking the encounter with Her, propelled by the desire for Union. When the traveler reaches the corresponding stage along the way, the veils that cover the face of the Beautiful One are lifted to reveal the dawn, warning of the danger of unmediated vision:

Cast her a glance through that veil/for (the vision) of such splendid beauty is too much to bear

When she raises her veil and uncovers her face she dims the brightest lights of morning.

Ah, Moon, who show yourself to us behind a veil/a timid blush on your cheeks!/You veiled yourself, for it would have been torture to behold your face unveiled.

The veils represent the insuperable distances between the diverse planes of Being. Whoever would to travel to “The Dwelling of No-Dwelling”, the seventh station, the meeting point, must suffer a symbolic death that presupposes the annihilation of the self [fanā] as a step toward knowledge. The Gnostic [sāalik] attains to the Lady’s subtle Presence through a tenuous mental perception in which the sacred—ever-present to the spirit—appears far away until it irrupts in the moment of theophany [tayallī ȳalālīˆ]. Only through the development of the spiritual heart [qālb] can the spiritual and material worlds communicate with each other, and the approach toward spiritual knowledge and Wisdom, marked by successive states [hal] and stations [maqām], takes place within this heart.

Just as in the Zohar and the Spiritual Canticle, Solomon is a fundamental reference in the Interpreter of Desires [Tarŷumān], while Wisdom, in the person of Nizām, the beloved object of Ibn ‘Arabi”s amorous laments, is a replica of Inanna, the Sumerian goddess praised by Akkadian poet Enheduanna in his ‘Nin-Me-Sar-Ra”, who is clearly related to Light (Sab. 7, 29–30).

For she is fairer than the sun, outshines every constellation of the stars/Compared to light, she is first of all/though night supplants light, wickedness does not prevail over Wisdom.

At the end of the day, the radiant Star, the Great Light that fills the sky, the Lady of the Sunset appears in the heavens.

You can see her, walking on crystal floors like a sun that mounts the firmament as far as the abode of Hermes

The profile of the Lady Wisdom, the object of the search in all three Hispanic spiritual traditions, is remarkably similar in each. She is remote; she inhabits the Mansion of Solitude, drawing near and then withdrawing, seducing the pilgrim by this game. She is elusive and majestic, demanding that her suitor await her patiently. Full of mystery, She is light and yet loves darkness and is sometimes deadly, as we will see in the next qasida where Ibn ʿArabi frames the description in this way: “You strike like Apollo’s lightning.” Her gaze is

The murderous look that kills. The sun of the highest sphere in the bosom of Hermes. It is the Torah, the splendor of Beauty. It is savage, and in its Presence there is no rest. It maddened the sages of our religion, just as it did the singers of the Psalms of David, the Christian monks, and the followers of the Torah.

As Henry Corbin says,

Nizām is invested with the theophanic function of Beauty, and from this apprehension there arises the idea of the Feminine-Creator not only as an object, but as an exemplary image of the sympathetic

devotio of the “faithful lover” [fideli d’Amore] (

Corbin 1958, p. 24). She truly possesses the secret of divinity [

sirr al rububiya], and she awaits the greeting of a lover maddened by nostalgia. She is the slender maiden whose smile radiates the

splendor of the sun ((

Arabî 2002, Cas. III-6, p. 111). Ibn Arabî speaks to us of an “orphan and exiled love”, “besieged by desires and pursued by swift arrows” (

Arabî 2002, Cas. IV-4, p. 113). There is no place for harmony in the time of rupture, and due to mis-encounters, the mountain and the riverbank diverge in a separation that only exacerbates the search for Union [

tawhid].

In a verse from sura Fussilat, it is said, “We will make them see Our signs on the horizon and in their souls” (41:53). The meaning of the statement for the Sheikh Al-Akbar is explained in a chapter where he deals with

sakina (peace, “serenity”, but also, like the Hebrew

Shekhina

h, the divine “Presence”): “The

sakina that God sent down for the children of Israel in the Ark of the Covenant [Qu’ran 2:248]” “was made to come down in the hearts of believers of Muhammad’s community [Qu’ran 3:110] …” (

Chodkiewicz 1993, p. 96).

The poetic text tells us of a heart woun

ded by the grief of absence that wishes to die in the gaze of its Beloved. There are symbolic references common to both Ibn ‘Arabi’s

Interpreter of Desires [

Tarŷumān] and Moses de León’s

Zohar, as well as St. John of the Cross’

Spiritual Canticle and

Living Flame of Love. One of them is the significant Presence of water, as in “To the Water” (

Arabî 2002, Cas. XIII, 2, p. 130), where Ibn ‘Arabi refers specifically to the sacred well of

Zamzam, near the Ka’aba in Mecca, the meandering streams, the rain, the Living Source (

Arabî 2002, Cas. XIII-2, p. 130) the “fire”.

Whoever ignites this fire, beware!/This fire of passion belongs to you/take some of its flames too.

He also tells us of the thickets, the breeze that spreads the fragrant odors, of “Love” among the flowers of the Garden (

Arabî 2002, Cas. VIII, p. 121) of the “Ringdove” (

Arabî 2002, Cas. XI: vs.1, p. 124), of the thirst for Love, of the “veiled gazelles” whose eyes send signals/who pasture in the breast” (

Arabî 2002, Cas. XI, vs. 1, p. 124), of the

arāka and

bān trees (

Arabî 2002, Cas. XI, vs. 12, p. 125). It is worth noting, as well, an erotic reference to hair (

Arabî 2002, Cas. VII, 9, p. 118):

When they feel fear they let fall their hair/and with their tresses steal away into the darkness.

In the

Zohar and in the

Spiritual Canticle, just as in the Sumerian texts, mystical terms refer to the erotic qualities of human life. The instinctive engine that drives the journey is a relentless desire. The mystical itinerary speaks to us of an incarnation of divinity that becomes palpable in all things. The image of the Beloved cannot be captured; it can be seen only in an epiphany, yet it is reflected in nature and in the soul as in a mirror. Language, the mediator between the two planes, is situated on that borderline where the body ends and the spirit reveals itself. The Beloved is the paradigm of intangible beauty and wisdom. The poet must travel far along the path that leads to Knowledge, a trajectory that must be read in terms of Presence/absence (

Arabî 2002, p. 19) [

hadra/gayba]. The absence of love is fatal, and once the encounter takes place, the heaviest burden of love becomes easy to bear. As in the

Spiritual Canticle, the poet in love “dies of love and melts like snow” (

Arabî 2002, Cas. XV, vs. 2, p. 135).

For Ibn ʽArabi, all Creation is essentially a theophany [

tajallî], and as such is an act of the divine power of imagination. Accordingly, the organ of active human imagination is identical to the organ of the absolute theophanic imagination itself. The creative act proceeds from the primordial sadness and loneliness of an isolated divine being that impel Him to make Himself manifest in human beings who, in turn, reveal Him to Himself. Divine compassion leads Him to reveal Himself to the creatures through which His Names and attributes will operate and testify to his creative ability and supreme Wisdom. This epiphany is evident in the passage from the state of concealment, of implicit potency, to the luminous, externalized and revealed state (

Corbin 1958, p. 139). In short, life results from the dynamism linked to a recurring creation, renewed at every moment and resulting from an incessant theophanic imagination projected through a succession of theophanies [

tajalliyât], thanks to which beings are in continuous ascent. The names hidden in the Supreme (the “beautiful noble ones” referred to in sura 59:24), longed to manifest themselves. In a

hadith, Allah declares: “I was a hidden treasure and I loved to be known; so I created the creatures …”

Ibn ʿArabi holds that divine compassion embraces the God created within the creeds (

Corbin 1958, p. 91). The Gnostic, however, is faithful to his own Lord, to the divine name with which he is invested. Therefore, each form or path implies a link to a certain phenomenology of prayer [

dhikr] that refers to the emergence of the invisible being [

bâtin] and its eternal individuality, as manifested through the compassionate and merciful breath in the Worlds of Divinity and Humanity:

lâhût and

nâsût. Each being is an epiphanic form [

mazhar] of the divine being, his Lord, who manifests himself in a creature under one or more divine names (

Corbin 1958, p. 93). “The Supreme Secret” has two aspects: The Name manifests thanks to the servant, who is the fulfillment of that

pathos. There is, therefore, necessarily a correspondence between the Divine and His creature. This covenant of sympathy exists from pre-eternity, so that once beings come into existence, God praises Himself in all creatures; they are His theophanies. Consequently, the life of the mystic tends to realize this union of

simpatheia by which God establishes a dialogue with himself in terms of Love. Ibn ‘Arabi describes this beautifully when he says, “All creatures are wedding beds where God manifests Himself”. Furthermore, the Andalusian master does not shrink from asserting something that may sound heretical to the ears of the jurist: God is present only insofar as he is recognized (an assertion difficult to reconcile with absolute divine sufficiency). That is the magic of creation. It is precisely such participation that potentiates the perfect human being,

Insam al Kamil, who bears all the Names of God and realizes them harmoniously. This concept is also found in Jewish tradition, as well as in Fray Luis de León.

5. The Light of the Zohar: The Book of Splendor

With the help of the Zohar we will emerge from exile (89–90): “The wise will shine like the splendor of the firmament”

The

Sefer ha-Zohar is one of the most representative texts of the Jewish Kabbalah. Like the much older

Sefer ha-Yetzirah (the Book of Creation, or alternatively, of Formation), the text applies a metaphysical-poetic hermeneutics of the first moments of creation to the accounts found in the Torah, where the erotic echoes of the

Song of Songs resound:

The flowers are blooming, the season of the singing birds has come, and the lullaby of turtledoves fills the air. The fig trees begin to form their fruit, and the fragrant vines are in bloom.

Rise up, my beloved! Come with me, my beautiful woman!

(Song of Songs 2:8–13)

The

Sefer Ha-Zohar17, hereinafter the

Zohar, the greatest recopilation of the Hispanic Kabbalah, is transmitted in a theosophical-theurgic treatise that advocates a mystical path of knowledge and action whose objective is to describe the various manifestations of the God of Israel as implied in the revealed wisdom of the Torah. Not surprisingly, the

Zohar, as a kabbalistic text, was long regarded as a cryptic and unapproachable collection of secret knowledge, lacking a necessary exegesis and reserved solely for a minority of rabbinical scholars. It is unanimously acknowledged as “the deepest, darkest, most mysterious, and the principal work of all the books of the Kabbalah” (

Laitman 2011, p. 16).

There has been some controversy over the origins of the work, but Gershom Scholem (

Wolfson 2001, p. 171), Elliot R. Wolfson, and Moshe Idel, after a rigorous and methodical examination of the historical and philological elements, adhere to Isaac of Acre’s theory, which ascribes the work to Moshe ben’em Tob of León. Known to us as Moses de León, he was an outstanding figure within the world of Hispanic Sephardism. Most probably born in León, he lived in Guadalajara and died in Ávila, where some researchers believe that part of the

Zohar was written. In Abraham Zacutor’s

Sefer Yuhasim, Isaac of Acre (

Wolfson 2001, p. 171) attests that the work was written by Moses de León. For his part, Yehuda Liebes (

Wolfson 2001, p 173) promotes a widely accepted theory that attributes the work not to a single author, but to a mystical group or fraternity operating in Castile under the direction of Moses de León. This group of rabbis and leading Kabbalists would include Joseph Gikatilla (Yosef Chiquitillia) and Abraham Abulafia himself.

Whether the product of a single author or a group of mystics, most researchers agree that the book was written in Castile, and some, like Yitzahak Baer (

Wolfson 2001, p. 174), further assert that it is a reflection of the Castilian society of the time. The

Zohar, in this view, would be a record of the actual experiences of Jews living in that complex, multi-cultural Spain. Gershom Scholem takes a similar and perhaps more extreme position, maintaining that the authors of the

Zohar describe, under a kabbalistic interpretation, a compendium of the habits and customs of the Jewish community in 13th-century Castile (

Wolfson 2001, p. 174).

The work purports to consist of the teachings given by R. Simeon ben Yohai in the second century C.E. to a group of his followers hiding in a cave in Galilee during the Roman occupation. Its structure consists of sections and imaginative stories that interpret the Torah. As previously noted, researchers like Yitzahak Baer and Gershom Scholem regard these stories as reflections of the Jewish life of the time, with Scholem claiming that Moses de Leon dressed his interpretation of Judaism in “archaic robes” to make it more acceptable, while Isaac of Acre credits him with having, in a sense, turned the story into a novel to assure that it would be more widely read.

It is worth noting that Michel Laitman is a principal dissenter who prefers to ignore the prodigious and unique Castilian contribution and attributes the Zohar to the author identified as Simeon ben Yohai, declaring that the text remained concealed until “at the right time” (somewhere between 1930 and 1940), when the world was prepared to receive the teachings and his own teacher, Rabbi Yehuda Aslagh, composed the exegetical commentary Ha Sulam (“The Staircase”).

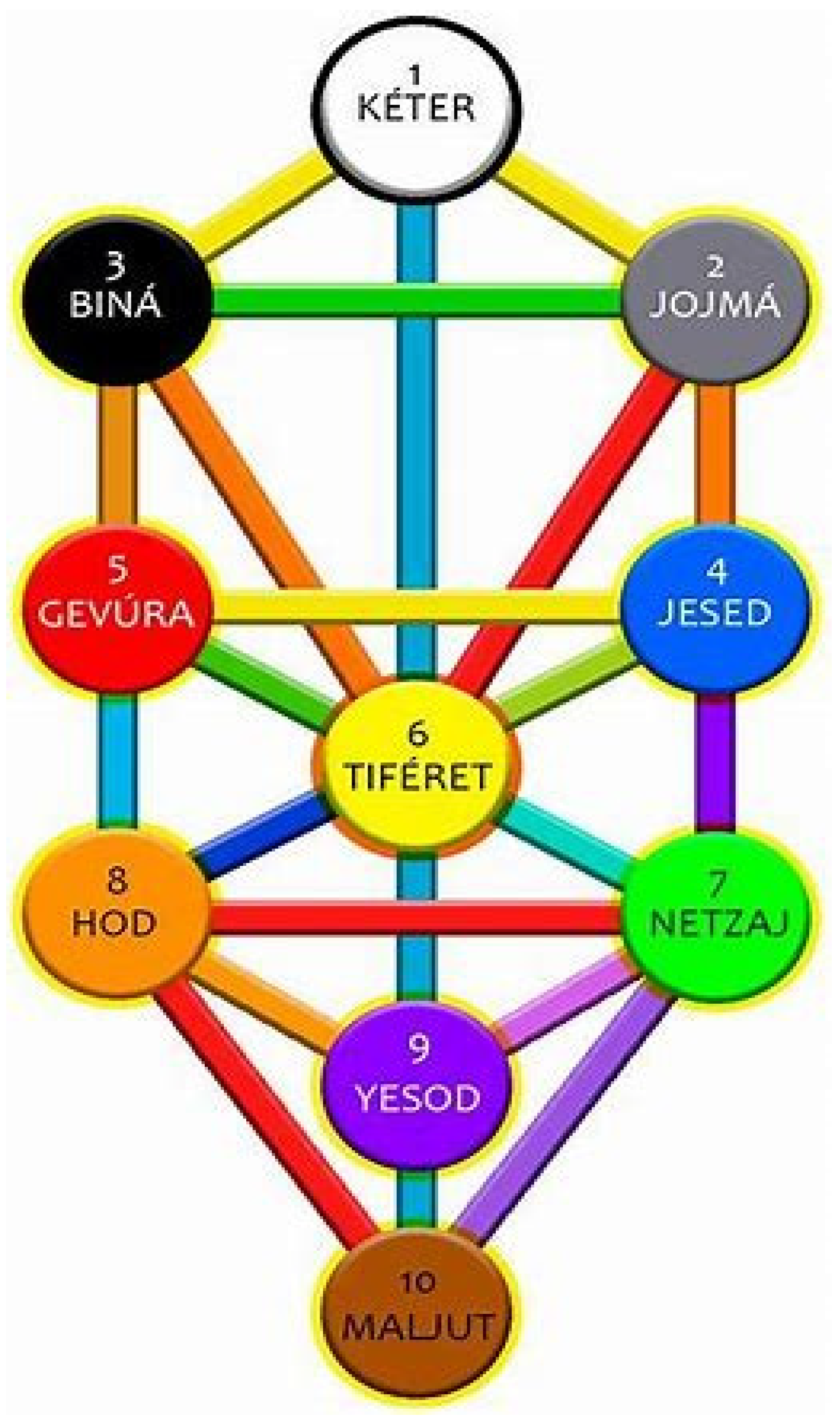

In order to penetrate the meaning of the stories related in the

Zohar, one must remember that in it the Torah is perceived as a game of enigmatic puzzles through which the Creator speaks to His people by means of an esoteric numerology of letters, Gematria, in which the secrets of life and of the Universe are first concealed and then gradually revealed by the ascending knowledge of the emanations of divine Wisdom: the

Sefiroth, which shape de Tree of Life

18 (see

Figure 1). Any analysis of the work requires the reader to implement a poetic and symbolic hermeneutics and apply them to the elucidations of the Torah performed by the Kabbalists around Moshe de León. The truth is that the “Book of Splendor” speaks to us of a resplendent reality linked to the mystery of divine Wisdom (

Sod Hokmah ʼĔlohit) and to an enlightening gnosis that aims to decipher the most sacred of the divine names: YHWH, the Unity of God. The mystic who “receives” enlightenment,

Maśkil, understands with “the eye of the intellect” (

‘En Ha-Ṥekel) thanks to a noetic, intuitive, and non-discursive knowledge. This sense of mystical “vision” is as fundamental to Hebrew mysticism as to the corresponding Sufi or Christian version, a fact emphasized by Fabio Samuél Esquenazi (

Esquenazi 2020, p. 417 and ss.). Specifically, in the

Zohar the ecstatic experience is associated with divine powers that are visualized as refulgent letters inscribed in a book written by God, the Torah, identified with the Tetragram.

Wolfson (

2001, p. 165), considers that within the minority group in which the

Zohar was born, this mystical interpretation of letters bears an unmistakable imprint of Joseph Gikatilla.

19 Concerning the wisdom of the Kabbalah, Wolfson suggests that it may be a theosophical application of what was originally a philosophical concept (

Wolfson 2001, p. 169). As Wolfson himself indicates, although Moses de León began as a follower of Maimonides, and particularly his

Guide for the Perplexed (an antithesis to the

Zohar20), he subsequently evolved through a process of ecstatic contemplation. This process took the form of the emanating images that shape The Tree of Life, a diagrammatic ordering in which the feminine and masculine components complement each other, constituting a complex geometry through which the sacred manifests in the ten

Sefiroth, or planes of being. These

Sefiroth are polar powers derived from the sacred tetragram YHWH, and their interplay represents the dynamic and bi-directional flow of the original principle whose objective is to make the Primordial Man, the

Adam Qadmon, sprout from the depths of each soul. In this way, the

Zohar provides a guide to the spiritual path, a map condensed in the Tree of Life, in which Reality is structured in terms of descending spiritual worlds.

The Tree of Life also corresponds to an anthropomorphic image of the relationship between divine energies. Not in vain “God created man in His image and likeness”, and the Hebrew letters form a model equivalent to the structure of a human body, which is identified as the actual celestial metaphysical order, seen through its reflection in a mirror. Thus, the human representation can be understood only in the light of the divine, composed of the letters of the Hebrew alphabet summarized in the Tetragram, a theonym, or proper name of God, the root of the mystical language and essence of the Torah.

Aritmosophy is essential to Zoharic rhetoric, just as it is to Sufism. In this sense, we refer to the connotation of the very term

Sefiroth, (sₑfar), “numbers”, referring to the separate intellects and linked to each of the celestial spheres (

Wolfson 2001, p. 167). The word can also represent

sappir (luminosity, sapphire) and

sefer (speech, book). Wolfson explains (

Wolfson 2001, p. 176) that “no word in English or Spanish can account for all the semantic connotations associated with the term

Sefiroth”.

The group of planes or

Sefirah that Laitman denominates as ZA

21,

Zeir Anpin, (

Laitman 2011, p. 31), are located between the upper spheres

Keter,

Hokmah and

Binah; while the lower position,

Malkuth, is united around the Balanced Beauty of

Tiferet to

Yesod (ego sphere),

Hod (mental sphere),

Netzah (emotional sphere),

Yesod (compassion) and

Gevurah (severity). As the heart,

Tiferet occupies a central place in the Tree of Life, replica of the human being. It is in

Tiferet that the spiritual correction of the process occurs, and thus it is the culmination of the lower

Sefiroth.

Therefore, taking ZA into account, the Sefiroth can be reduced to five. Keter (the Crown, first Sefirah) represents the pure potential of any manifestation. Prior to all mental processes, it cannot be captured by thought, and it occupies a central position in the Tree. Hokmah (Unlimited Wisdom) is the second Sefirah and the first intermediate step between Keter, the Crown, and the other Sefiroth. It represents the primordial idea. Binah (black as the womb where life thrives) is the rational process and the limitation of Hokmah. ZA represents the meeting of the five Sefiroth previously mentioned in Tiferet with Malkuth. The last of the 10 Sefiroth, Malkuth symbolizes the desire to receive for oneself. It is the lowest layer of manifestation and corresponds to the human being). All the Sefiroth are interconnected, and each of the 10 Sefirah includes all the others within itself. Each, in turn, consists of ten sub-Sefiroth.

The process of knowledge is as follows: ZA requests the Light for Malkuth from Binah, who receives it from Hokmah, the depository of the Creator’s Light; and subsequently “the opening of the eyes” occurs in Malkuth. During this entire process, it is imperative to “listen” to action, and then “the eyes” will rise from Malkuth to Hokmah, in a return to the Creator. The “One who opens the eyes” is MI, and above Him no questions remain. In this process Hokmah, the seed of creation, acts through Binah which is placed under Hokmah and transfers the Light to Malkuth, the feminine recipient. Malkuth must rise up to Binah, who receives the Light of Hokmah. Once Malkuth (thanks to the fact that Keter and Hokmah descend toward her) “becomes equal to” her husband with “the opening of the eyes”, she rises beside Him to AVI (Hokmah and Binah), where the spouses are enveloped in its Light.

As we have previously indicated and as we will later see, the erotic echo of the Song of Songs continues to resonate through the text attributed to the circle of Moses de León. Thus, we can affirm that the axis of the Zohar is articulated around a polar structure of the single divine principle in the form of a couple. This polarity implies a theosophical sensuality in which the feminine power acquires supreme relevance, as a luminous beacon and complementary creator of the unreachable and unspeakable essence. It is this that allows the human soul redeemed from exile and vivified by the Light of Wisdom, after a relentless search, to fully adhere to the incomprehensible primal Force,

Under the auspices of the two polarities, male and female, and full of encounters and dis-encounters, laments, compliments, and seductions, the search is marked by the tireless and desiring vivacity of the spiritual Sapience, the Divine Presence or Glory of God: the

Shekhinah. She loves secrecy, enigma, and concealment, as can be seen in the discourse that Simeon ben Yohai develops from the parable of the princesses (Ex. 21–24), the principal passage of the Zoharic story of the

Princess who is identified with the

Torah, pure love.

The Torah can be compared to a beautiful and majestic maiden who is held in an isolated bedroom of the palace, and has a lover of whose existence only she is aware. For her love, he continually passes by the bars and looks around in all directions to discover her.

She knows very well that he is forever hanging around the palace and what does she do about it? She opens wide a small door in her secret bedroom, for an instant reveals her face to the lover, and then quickly retreats. Only he, no one else, is aware of this; but he knows that it is out of love that she has revealed herself to him, and his heart, soul and everything within him are directed towards her.

A striking characteristic of this parable is the way in which it addresses themes identical to those of Ibn ‘Arabi and Saint John of the Cross, two other Hispanic mystics, as well as the frequency of symbols common to all three: signs, messengers, locutions behind the veil, and glimpses. In all of them, there is a traveler who gradually progresses along a journey motivated by longing, and as he progresses, a “maiden” appears, hinting at some of the secrets behind the veil. The Zoharic story speaks of a beautiful princess (reto behimatá = beloved) who, concealed in her palace, cries out for the love of her lover (rehimáh) and in her lament brandishes her seductive weapons. Her goal: a union in marriage. This account, replete with a powerful and archaic symbolic density, emphasizes the game of concealment and incitement that constitutes the axis of the “journey” in both Ibn ‘Arabi’s The Interpreter of Desires and the Spiritual Canticle of St. John of the Cross.

In this sense, Fabio Samuel Esquenazi

22 conducts an extremely refined hermeneutics of the

Zohar. In lingering over a particularly enigmatic

Zoharic story, the “Maiden without Eyes” (the Torah in this example) he refers us to Is. 43,4. The exegete is the sage “full of eyes” (

Esquenazi 2020, p. 432) who knows how to decipher the riddles of a serpent that flies through the air with an ant lodged in its mouth; of an eagle that inhabits a tree that never existed, from whose nest were stolen eaglets as yet unborn, and which remain, still uncreated, somewhere; and the enigma of the maiden without eyes, whose body is both hidden and revealed, who emerges in the morning, is in hiding during the day, and is adorned with non-existent ornaments. The ancient rabbis considered the Torah to be the

Shekhinah herself, the manifestation of Yahweh’s Presence in the world, not only as the wife, bride, or daughter sent into exile by the King in the context of the Jewish symbology of exile, but as a maiden who “has no eyes”, or has cried her eyes out on account of the loss of her homeland (

Esquenazi 2020, p. 432). This celestial sexual polarity in which the metaphysical senses of sight and hearing become more acute, is in all these terms consubstantial with the human being. As a reflection of the supernal entity, and like Her, the human being conjugates within itself both the masculine and feminine.

Consequently, our world as a whole is a mirror, a reflection of what occurs in metaphysical realms, in boundless spaces in which the entire existing universe is combined in pairs, as implied by the Pythagoreans with their list of opposites. That said, the whole of the Zohar can be seen as a wager on the Union of those opposites without synthesis or annulment of the extremes; it envisions the coupling of different elements in the One. To know oneself involves discovering the complexity and concurrence of opposites within an identity that is assumed as one’s own, and to this end, metaphysical vision and hearing are activated.

The

Zohar says:

Man is the inclusion of masculine and feminine, for he in whom masculine and feminine are joined is called, “Adam” and then worships God. Moreover, there is humility in him. And even more, there is mercy in him.

Upon the arrival of the Messiah (the Union in Light, or the reception of supreme Knowledge), humanity, the Eyeless Maiden, will abandon spiritual exile, which is linked to the self and to the destruction of the Temple. Access to transcendent knowledge requires irradiation and luminous reception in each of the souls that act as “vessels” brimming with the desire to receive: that is what the term Kabbalah means.

Thus, the content of the work deals with the loving relationship of the human being with his Creator, through the mediation of his wife, who assumes various identities: Wisdom;

Shekhinah (Presence of the Glory of God);

Binah (understanding and delimitation of the Light);

Keneset Yiśraʼel (The Community of Israel); and

Malkuth (the human being). The feminine, Wisdom, is the Creator of life both in heaven and on earth and in the

Zohar the earthly is a reflection of the heavenly. The heavenly copulation (

Zivug) means the union of the supernal spiritual male and female, from Light to Light. (

Zohar, 201): “The union of the sexes in this world will be from body to body, and the righteous who follow the right path “are rewarded with the pleasures of that world” (

Laitman 2015, p. 219). (

Zeir Anpin, the masculine, joins

Nukva, the feminine =

Malkuth, once it has descended to the last step.)

Ishah, woman, means

Esh, fire of the Creator,

Alef-Shin, and this fire is connected with the letter

Hey, which is

Nukva (

Laitman 2015, p. 216), the feminine, plenitude of the left enlightenment due to the irradiation of the male

Sefiroth Hokmah. Thus, the feminine receives the “luminosity of

Hokmah” (

Or Hokmah Hasidim), and from that “reception” (

Lekabel=Kabalha) arises a similarity (

Laitman 2011, p. 107) to the Creator, derived from the enjoyment of pleasure in the Union. “And the Light of the Creator will turn to fire” (

Laitman 2015, p. 216).

Zohar 146 states that when the

Sefiroth Sefira Binah, located on the left, which represents the understanding that comes out of Eden, and

Hokmah, the Light of Wisdom on the right, come together under

Keter, the Crown of the Tree of Life, they adhere to the world of

Malkuth in Love. Therefore, the Congregation of Israel, the

Nukva,

23 the wife, appears in the

Zohar (

Laitman 2015, p. 207) as the bride of the

Song of Songs. “Thus, the Congregation of Israel said, set me as a seal upon your heart (

Zohar 731) because “Love is strong as death” (

Zohar 732) (

Laitman 2015, p. 207).

Another line from the

Song of Songs (1, 2) collected in the

Zohar (371), says: “He will kiss me with the kisses of his mouth” (

Laitman 2015, p. 204). Laitman/Aslach (

Laitman 2015, p. 204) interprets this verse

24 as King Solomon’s words expressing the love between the higher world,

Zeir Anpin, and the lower world (ZON) composed of all the

Sefiroths linked to

Tiferet and the last

Sefiroth of the Tree of Life,

Malkuth. One spirit adheres to another with a “kiss” and “the kiss on the mouth is the entrance and exit of the Spirit”. When the kiss occurs, the Union is sealed.

The wife is the essence of the house, (

Zohar, 231) and when “the house is corrected”, the masculine and feminine are also corrected, and then the masculine comes to the

Nukva, and they join together (

Laitman 2015, p. 216). Laitman/Aslagh (

Laitman 2015, p. 205) refers to another fragment of the

Zohar (70): “See life with the woman you love”, in which “the woman you love” denotes the Congregation of Israel, the

Nukva, because love is written about her; and it is linked to Mercy, the

sefiroth Yesed, on the right side of the Tree of Life. The Assembly of Israel assumes the role of wife of the divinity, just as the Church does when it becomes the bride of Christ. However, when the community disobeys the Creator’s precept, the

Shekhinah retires, and the exile and rigor of the masculine prevail over Mercy.

In this respect, there is a curious paragraph (327) in the

Zohar referring to women. When Israel deviates from its path, the prophet says,

Indolent women, how can they be calm? Why do they remain seated and do not wake up the world? Stand up and rule over men.

A further mention of the feminine souls in the

Zohar (195–202) describes six Palaces of feminine souls and four others that are hidden (

Zohar 201): the ten

Sefiroth. Every midnight all the Palaces, both heavenly and terrestrial, are gathered together (

Zohar, 201) in the heavenly and terrestrial coupling (

Zivug):

I was shown six palaces with various pleasures and delights in the place where the curtain is displayed in the garden, since no man may enter beyond that curtain (…) There are four hidden palaces of the holy mothers that were not taken into exile. Every day they are alone.

The

Zohar (145–147) also reproduces the Palace of Love (

Laitman 2015, p. 205): the Temple, Paradise, the Garden, the

PaRDéS. Everything is founded on amorous coupling. When the higher,

Zeir Anpin, and the lower,