Abstract

This paper explores the religious projection and ethical appeal in the art and literature of Leda and the Swan created from ancient times to the contemporary era, so as to make a comparative review and reading on it, providing religious reflection and ethical enlightenment to today’s society. From ancient Greek vase paintings to contemporary English poems, the investigation shows that the story of Leda and the Swan has been continuously rewritten and revalued by history, religion and social ethics. The interaction between Leda and the swan goes from divinity to humanity, increasingly out of the cage of eroticism, symbolizing the process of transforming into a secularized life. Besides, Leda, as a representative victim of traditional patriarchy and religious persecution, goes from bondage to liberation, signaling the awakening of feminine consciousness and the gradual collapse of patriarchy; while the swan, an incarnation of power and desire under patriarchy, becomes an object of condemnation. However, as for who is the victim and who should be condemned, there are different religious and ethical standards in different historical periods, which reflects the development and evolution of religious rules and ethical orders in the historical process. By highlighting the Trojan War or woman’s sufferings, Leda and the Swan, in fact, reveals that the tragedy results from the uncontrollable animal factor and free will, and that women should face their ethical or religious identities to make correct choices.

1. Introduction

“Myth, a story of the gods, a religious account of the beginning of the world, the creation, fundamental events, the exemplary deeds of the gods as a result of which the world, nature, and culture were created together with all parts thereof and given their order, which still obtains. A myth expresses and confirms society’s religious values and norms, it provides a pattern of behavior to be imitated, testifies to the efficacy of ritual with its practical ends and establishes the sanctity of cult.”——The Problem of Defining Myth (Honko 1984, p. 49)

As a kind of artistic creation consisting of narratives produced in the early stage of human society, myth, or mythology, is an “account of social customs and values” (Sofroniou 2017, p. 102). It records the social religion, philosophy, politics, and cultural conventions at a certain time, and plays a fundamental role in people’s daily lives to establish religious and ethical values and norms. It is well known that Greek mythology is not only the arsenal of Greek art but its foundation. Greek art presupposes Greek mythology with its nature and social forms already worked over by folk imagination in an unconsciously artistic form.1 This kind of artistic form can stimulate human’s religious feelings in sacred rituals and exaggerate the solemn and mysterious spiritual atmosphere. This is because art renders the human situation, such as genesis, existence, death, and afterlife, comprehensible through visual or tangible representations in symbols of iconography or gestures of the human body. At the same time, theological thinking and ritual action are also transformed by the work of art, so that “art is not always merely the representation of the original theological ideas, but is constitutive of theology and ritual life themselves” (Apostolos-Cappadona 2017, p. 10). Thus, mythology, religion, and art actually are combined and integrated: the mythology endows religion and art with rich connotation; the religion and mythology provide artists with broad imagination and creative space, and the art in turn communicate religious beliefs, customs, and values to support an ideal path for salvation and spiritual inspiration.

Leda and the Swan, one of the most enduring subjects in art, religion, and literary creation in history, originates from ancient Greek mythology, which narrates that the god Zeus, in the form of a swan, seduces and rapes the beautiful mortal Leda, the wife of the Spartan king Tyndareus. Then, Leda lays two eggs that hatched four children: Helen and Polydeuces, Clytemnestra and Castor. Later, Helen causes the Trojan War, and Clytemnestra murders Agamemnon, the leader of the Greeks at Troy.2 This myth often falls into the trap of pornographic and violent propaganda no matter in ancient times or today due to its novelty and people’s curiosity (Cullingford 1994), but beyond that, it describes the relationship between the god and human beings, highlighting the religious values and ethical norms in society: (1) there is a god (or Zeus as a man), who controls the world, and mortals (or women) are dominated3; (2) human beings should recognize their differences from the animals (or the god) and liberate from them so as to make correct ethical choice4; (3) breaking the religious order and violating the ethical taboo in society will inevitably lead to (ethical) tragedy.5

These religious thoughts and ethical ideas embodied in Leda and the Swan from Greek mythology extend and vary with the changes of eras and religious or ethical norms in society. They are projected in the creation or recreation of Leda and the Swan in different forms, such as sculptures, paintings and poems since art, as a mode of creative expression, communication, and self-definition, is “a primordial component within human existence and an essential dynamic in the evolution of religion” (Apostolos-Cappadona 2017, p. 9). Initially, Leda and the Swan was just oral text popular among people in ancient Greece, often portrayed on potteries, sculptures, and mosaics, etc. Around the first century B.C., Ovid (43 B.C.–17 A.D.), an ancient Roman poet, wrote this myth in his epics for the first time. It then became a household story in Medieval Europe, and almost all the artists attempted to depict the sex and love scene with many symbolist and expressionist treatments, but their creations were mostly burned and destroyed due to religious intolerance. Afterward, there came the most famous paintings from Leonardo Da Vinci (1452–1519) and Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564) in the Italian Renaissance, and the most influential English poems from Irish modernist poet W.B. Yeats (1865–1939) and American poet Sylvia Plath (1932–1963) in the 20th century.

Because of the attractive themes and abundant creations of Leda and the Swan, the studies on this subject, from different perspectives, are incessant, especially on Yeats’s poem. For example, in recent years, scholars have discussed various topics of the seduction and rape ranging from (1) the perspective of feminism and (post-) colonialism to center on Leda’s sufferings as well as her pleasures (Neigh 2006; Chang 2017); (2) the historical and cultural view to highlight Leda’s resistance and underline the social environment and Leda’s (or the poet’s) identity (McKenna 2011; Babaee and Wan Yahya 2014); (3) to reveal the philosophical ideas and political appeal hidden in it (Hurley 2009; Hong 2018); (4) the style and structure of a painting or a poem to ponder over its creative motivation, like political, psychological and cultural factors (Gavins 2012; Guo 2018); and (5) even to make comparative studies to uncover the ekphrastic interaction and aesthetic experience between paintings and poetry (Ou and Liu 2017). Nevertheless, the religious values and ethical thoughts are yet to be further explored in these paintings and literary works. With respect to art, it is about “ethics” in nature (Nie 2014, p. 13). It is likely that “one will miss the artistic relevance of religious aims and ideas”, but in fact, religion and art have more “internal multiplicity” than has often been acknowledged, and they “exist and blend together seamlessly in the earliest stages of their development” (Brown 2014, p. 14). Therefore, this paper, returning to the religious values and ethical norms of the myth (from the perspective of ethical literary criticism, feminism, and visual grammar), aims to explore the religious projection and ethical appeal in art and literature of Leda and the Swan created by different people from ancient times to the contemporary era, so as to make a comparative review and reading on its paintings and English poems, and what is more, to give religious reflection and ethical enlightenment to today’s society.

2. Discussion

2.1. Patriarchy and Divinity: Leda and the Swan in Ancient Greece

Leda and the Swan is often linked with sex and violence because of Zeus’ rape of Leda. From the historical view on the development of human civilization, art or literature is only a part of human history and cannot be separated from history. If it is separated from the history for interpretation, there tends to be a kind of misunderstanding or erroneous judgment, or the moral paradox (Nie 2010, p. 14). Hence, it is of vital importance to return to the religious and ethical context of a certain period of history to interpret Leda and the Swan, to explore the objective religious and ethical causes and factors influencing the painting style, and the events and the fates of characters in its narratives. Ancient Greek religion was a mixture of nature worship and ancestor worship, with various rituals. The Greeks worshipped natural beings and spirits, such as animals, trees, rocks, and hills. Before the union of Greece, each nation had its own system of gods. After a long process of religious integration, the ancient Greek poet, Homer, wrote the Homeric epics—the Iliad and the Odyssey—so that the huge group of gods of different nations were woven into mythology in the form of clans. The main worship of the Greeks was centered on the 12 major Olympian gods and goddesses. Hesiod, another ancient Greek poet, created the Theogony, giving a comprehensive description of the origins and genealogies of the Greek gods, with Heaven and Earth bringing logos and order to the world. At this point, the gods and their stories in Homeric epics and Theogony are important components of Greek mythology, which also are the core of ancient Greek religion and ethics. In the course of these newly developed concepts, religious values and ethical norms were formed as follows:

(1) Polytheism or multi-deity worship, and Zeus as the king or ruler of the gods. This indicates that ancient Greeks have a wide range of religious beliefs and their ideology is not restricted so that greater freedom and equality in religion are developed; but by taking Zeus as the king of the gods, it foreshadows a fundamental origin of patriarchy and monocracy in Greek society. (2) Integration and harmony among human, god, and animal, or the combination of divinity and humanity. In Greek mythology, deities are visualized as human or half-human and half-animal in form, and they all share human feelings and experiences, which represents a kind of human-centered cognition. Besides, some deities often transform themselves into animals to interact with human. Thus, in the iconography, god and animal are intimately associated: the bull appears with Zeus, or the bull or horse with Poseidon (Burkert 1985, p. 65). In this regard, the integration of human and animal, or the recurring image of half-man and half-animal, such as the god Pan and satyrs, on the one hand, builds a close relationship between human and animal; on the other hand, it brings about the religious and ethical confusion of “to be a human or to be an animal”, similar to Hamlet’s dilemma of “to be or not to be.”6 This tends to make the human fall into ethical predicament and hard to make correct ethical choice. (3) Existence of female deity, or the goddess. The goddess in Greek mythology is often associated with beauty, love, sensuality, fertility, and motherhood, which shows the role of woman in society and sometimes suggests the origin of evil, death, or war.7 There were segregated religious festivals in Ancient Greece only for women, like the Thesmophoria festival for agricultural (or woman’s) fertility. It is “central to the polis’s construction of its religious identity” (Dillon 2003, p. 109) that makes women’s status inferior.

Since the ancient Greek religion is polytheistic, without the control and intervention of a special priesthood, or the restraint of a unified religious faith or creed that must be observed, artists, under the influence of myths and their religious values, could exert their own imagination and satisfy their desire for self-expression, self-appreciation, and self-worship in creation. Thus, there is a large number of vivid artistic images representing the divine and secular world, especially in the art of paintings and sculptures. Leda and the Swan is one of the most popular subjects. The following is one of the artistic works of Leda and the Swan in ancient Greek time.

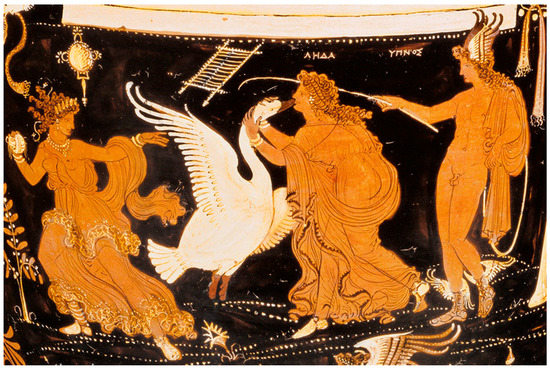

In Figure 1, it can be seen that Leda hugs the swan’s neck and head, and gently kisses the swan on its beak. There are two persons, a woman on the left and a man on the right, watching Leda’s interaction with the swan. Since images communicate meanings, when reading (visual) images, the analysis can be conducted from visual grammar on three aspects, namely representational meaning, interactive meaning, and compositional meaning.8 In a painting, something to be presented as center means that “it is presented as the nucleus of the information to which all the other elements are in some sense subservient” (Kress and Van Leeuwen 2006, p. 196). So, this ancient Greek vase painting narrates and pictures how the god Zeus, in the guise of a swan, seduces Leda, because the swan stands on tiptoe and Leda gives a kiss. It is the very beginning part of the whole story of Leda and the Swan.9 The whole scene is peaceful and natural as Leda bows slightly and kisses the swan with smile and tenderness, and with her eyes open and muscles relaxed, while the white and divine swan softly embraces and flutters his wings surrounded by natural plants. This representation or interaction projects a close relationship between the human and animal, or the god and human, not linked with pornography, conveying the Greeks’ animal worship and nature worship, as well as the integration between human and animal (or god), and displaying a kind of divinity and humanity.

Figure 1.

Apulian red-figure loutrophoros of Leda and the Swan, C4th B.C., © The J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu.

In addition, Leda and the white swan are in the middle of the painting. That is the dominant information of the whole to spotlight this sacred moment, and the information then can be expanded from the middle to the edge gradually. It can be noticed that the woman in the left (or Leda) is half-clothed and tilts backward; while the man on the right side, obviously taller than the two women, is naked, with his muscles and phallus clearly visible, and his one finger pointing at Leda (or a wand waving beside her head). The information from the two edges or margins to the center is related to given and new information, and usually “the elements placed on the left are presented as Given, the elements placed on the right as New” (Kress and Van Leeuwen 2006, p. 181). So, the given information is about the woman’s traditional role of labor and nurture in family and society as the left-side woman holds a ball of twines with part of her breast exposed; while the new information of the naked man represents the original (sexual) desire to control, implying the authority of paternity, a portrayal of the supremacy of patriarchy in ancient Greek religion through the male phallic worship for conquering over females; and the bowed Leda and the tilted woman indicate a kind of obedience. Moreover, the naked man wearing white boots and a headdress with wings is coincided with the swan and endowed with divinity like a god.10 Above the swan, there is a white ladder that humans can climb up to the residence of the gods in Greek mythology, revealing the Greeks’ respect and worship for gods, or the communication way with gods.

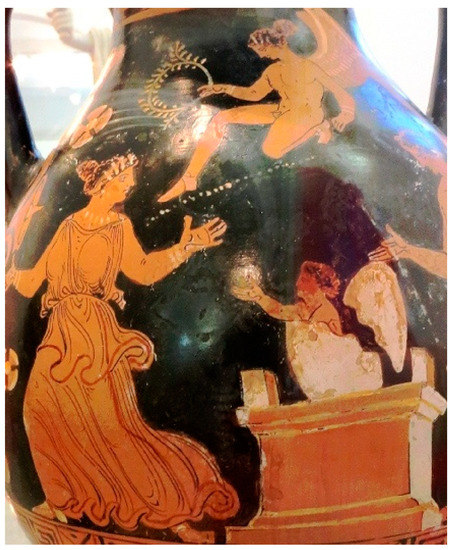

Figure 2 depicts the birth of a child (maybe Helen), belonging to the third part of the myth of Leda and the Swan. In this painting, Leda looks at the child and opens her arms in an embrace with her breast full and round, emphasizing fertility and motherhood; while the child, born on a large dais or altar from a white egg, is stretching out a hand to call her mother, which is solemn and sacred. This is a beautiful and peaceful picture of the birth of a new life, nothing to do with the sexuality, and the broken shell looks like the wings of a swan, suggesting that the child is the son of the swan or the god. In the right side, there is a naked man (shown partly here, not in form of a swan) with his hand touching the swan-form shell, showing his important role of paternity in making and witnessing the birth of the child. At the top of the painting, there is a naked child with wings hovering above, who could be Eros, the god of love and sex in Greek mythology.11 Kress and Van Leeuwen (2006, p. 186) propose that what has been placed on the top is presented as the Ideal, which tends to make some kind of emotive appeal and to show us “what might be”; while what at the lower section tends to be more informative and practical as Real, showing us “what is”. The birth of a new life is the “real” as the core of this painting, while the blessing of the God is the “ideal”. Eros brings the order, harmony, and peace to Leda and the swan (Zeus, or an ordinary man) as he holds a garland (or an olive branch) toward Leda. At the same time, he witnesses the birth of the child, which makes the interaction among Leda, the child, and the man divine and filled with love.

Figure 2.

Apulian red-figure loutrophoros of Leda and the Swan, C4th B.C., Photographed from the Art Museum in Kiel, Germany, © H. Föll.

2.2. Erotic Narrative and Original Sin: Leda and the Swan in Ancient Rome

Leda and the Swan in ancient Greece was merely the oral literature popular among Greeks. It had various versions, but they were not recorded in documents,12 so the artists could exert their own imagination to paint and their painting styles were not influenced by the written words. Around the first century B.C., Ovid, an ancient Roman poet during Augustus’ reign, collected the story into his works like Amores, Ars Amatoria, Heroides, and Metamorphoses. Then, there have been some related text records, and the painting styles are also displayed something different. In Ovid’s poems, Zeus (or Jove/Jupiter in Roman mythology) transformed into different kinds of animals to seduce the girls and rape them. As Ovid writes, “such as Leda was, whom her crafty paramour, concealed in his white feathers, deceived under the form of a fictitious bird”,13 and “beneath the swan’s white wings showed Leda lying by the stream” (Ovid 1922, p. 110). Often, Leda is portrayed as an innocent and pure girl who is deceived and raped by the swan under his white wings; while Zeus, in the guise of a swan, is cunning and sometimes violent. This depiction mainly belongs to the second part of the story, picturing the rape scene. What is more, in Heroides, Ovid gives some more detailed description to Leda’s body—her breasts are “whiter than pure snows, or milk, or Jove when he embraced your mother” (Ovid 1931, p. 253). Such lively and erotic depictions often appear in Ovid’s poems, representing the wickedly sensual and sexual mores, and providing a basis for the creation of paintings, sculptures, and artifacts in ancient Rome. For example, the rape scene in Ovid’s poem is vividly reproduced in the following Roman marble relief and Roman oil lamp of Leda and the Swan.

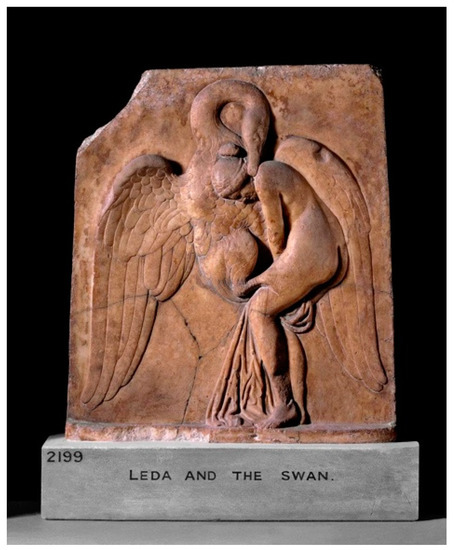

In Figure 3 and Figure 4, there is no “distance” between Leda and the swan compared to Figure 1. The naked Leda is leaning inwards and enveloped by the majestic swan’s wings. She curls up on the swan’s chest and clings to the swan, while the swan is grasping back of her neck with his beak (Figure 3) or is kissing her mouth (Figure 4), and having sex with Leda with his legs on Leda’s thigh. In Figure 4, there is one intact egg under Leda’s buttocks and a child with wings on the left side.14 The whole image is about the rape and is dominated by the swan as he locates at the center, presenting the initiative, force, or authority. Virtually, this direct and bold creation is associated with the ethical religious values in ancient Roman society. In Roman religion, gods are often seen as the manifestation of divine will and power, not having the characteristics of human emotion and behavior as in Greek religion. So, in paintings or sculptures, the divinity aspect is relatively less, and the artists mainly focus on the story itself. Since Roman government, politics, military, and religion were dominated by men, sex, love and marriage were all defined by the patriarchy, in which “religion contributes to a pervasive belief that such an arrangement was part of the natural order of things” (DiLuzio 2019). In the early days, Roman religion promoted sexuality for “fertility” and for state prosperity (Larson 2013, p. 214), and individual private religious practice and pornographic paintings featured among the art collections are popular under the “unlimited sexual license” (Edwards 1993, p. 65). The Leda and the Swan of Figure 4 is one of the products associated with these religious traditions.15 The given information of the egg and the child stands out the sexual intercourse for fertility. In addition, sexuality in Roman religion is linked with conquest and violence because “in contrast to the role of men as the impenetrable-penetrators of society, women are to provide the needed support to the men” (Goetting 2017, p. 3). Leda’s being in captivity, or obedience without resistance in Ovid’s poem, as in Figure 3 and Figure 4 reveals it in practice.

Figure 3.

Roman marble relief of Leda and the Swan, C1st A.D., © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 4.

Terracotta Roman oil lamp of Leda and the Swan, C1st A.D., © Staatliche Antikensammlungen, Munich.

Aside from the erotic description with religious values in the poems, Ovid also talks about Leda’s ethical choice in his Heroides16:

For, as to my mother’s seeming to you a fit example, and your thinking you can turn me, too, by citing it, you are mistaken there, since she fell through being deceived by a false outside; her lover was disguised by plumage. For me, if I should sin I can plead ignorance of nothing; there will be no error to obscure the crime of what I do. Her error was well made, and her sin redeemed by its author. With what Jove shall I be called happy in my fault?(Ovid 1931, Heroides, p. 43, translated by Grant Showerman)

Ovid holds that Leda is deceived by a false outside of Zeus; but her own error and sin in fact cannot be ignored, despite the fact that they are redeemed by the myth’s author. Leda’s error here is that she does not recognize her differences from the swan (or the god) due to her animal worship and does not free herself from it or even resist. Leda is caught up inside, and her sin is her animal factor embodied in her body. For example, the original desires of beauty, sex, and fertility are vivid in Paris’ flirtatious remark: “If power over character be in the seed, it scarce can be that you, the child of Jove and Leda, will remain chaste” (Ovid 1931, p. 291). It means that if a woman’s “animal factor” prevails over her “human factor”,17 her deeds will develop in accordance with her libido or desire, and then will get out of control and make her violate the ethical norms. The birth of Helen is driven by this sin, and Helen herself probably will get stuck into such a similar predicament. Thus, it is hard for her to make a correct ethical choice or remain chaste. However, Helen thinks Paris is mistaken to change her decision by taking the example of Leda, because she chooses to obscure her crime and pleads ignorance of nothing. This evil thought indeed is also a sin of original desire that controls Helen, as her elopement and abduction with Paris in the end give rise to the Trojan War. Later, Fabius Planciades Fulgentius (fifth or sixth century A.D.), an ancient Roman mythographer, in his Mythologies (Fulgentius 1971, p. 78) criticizes that, “Although love of lust is shameful in all men, yet it is never worse than when it is involved with honor. [...] But let us see what is produced from this affair, no less than an egg, for, just as in an egg, all the dirt which is to be washed away at birth is retained inside, so too in the work of reviling everything is impurity.” Fulgentius’s comments further extend Ovid’s thoughts on Leda’s ethical choice. Fulgentius considers that lust is the original desire that makes human born in sin and guilty, which is close to the notion of original sin in Christianity. To Seneca, this original desire for pleasure (libido) is a “destructive force” insidiously fixed in the innards, and if unregulated, becomes cupiditas, lust (Gaca 2003, p. 111).

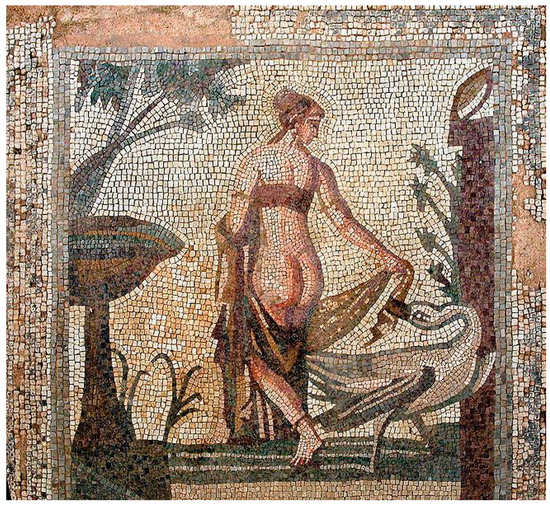

However, Ovid’s erotic poems such as Amores and Ars Amatoria, teaching the arts of seduction and love for men and women with examples of the gods from Greek mythology, were against Augustus’ religious reforms. Ovid himself was then banished to Tomis. In fact, Ovid’s time was one of profound transformation, from republic to autocratic monarchy. The religious conservative wants to maintain the traditional ethics and religious practice, while the new-school calls for pleasure, sex, and spiritual freedom. Confronted with political conspiracy, numerous cults, military rebellion, the extravagance in Roman social life, and the indifference in ethics among people, Augustus, known as the first Emperor of Rome, aimed to revive old Roman religious values to bring Rome back to the height of the Republic. Figure 5, an imperial Roman mosaic of Augustus’ time, can be a projection of the religious thoughts of Augustus.

Figure 5.

Imperial Roman mosaic of Leda and the Swan, C3rd A.D., © Cyprus Museum, Nicosi.

In Figure 5, Leda is the dominant figure, half-naked with her back facing us. Her clothes are taken off under her hips, which are made fully exposed. The swan grips and drags one side of Leda’s clothes with his beak, walking toward right on the ground; while Leda grabs and pulls it with her hand, heading forward on the steps. This picture belongs to the first part of the story, but it displays something different. Leda is not placed at the equal distance, or the same size with the swan, and she is given different direction from the swan, not like the intimate or dominant relation in Figure 1, Figure 3 and Figure 4. This mosaic uses this distance in a figurative way to highlight the scene of estrangement and alienation between Leda and the swan, even between Leda and her viewers, because distance and direction can be determined by social relations in interaction, and “non-intimates cannot come this close and, if they do so, it will be experienced as an act of aggression” (Kress and Van Leeuwen 2006, p. 124), just like that in Figure 3. In addition, the half-naked Leda is of full figure and fine presence, not fat but seemingly healthy, graceful, and elegant. Those erotic and sexy aspects, such as Leda’s naked hips, are placed at the center; but the distance between Leda and the swan makes it more mysterious and even ascetic, displaying the beauty of women and the role of fertility in society, which can be a projection of Augustus’ religious reform on the restraint of nudity or adultery.

Augustus took religious reform as a way to improve morality and ethics. He is often thought to be “traditional”, in favor of piety, chastity, and monogamy in ancestral values (Scheid 2005, p. 177). So, Augustus encouraged fertility and regarded sex within marriage as an institution to help sustain social order. However, Augustus discouraged adultery or rape, punishing those who engaged in extra-marital affairs, which later became a “capital charge” instead of a personal crime (Gardner 1991, p. 118). Furthermore, when Augustus revived the Lupercalia,18 he opposed and suppressed the use of “nudity” in spite of its function on the fertility aspect (Newlands 1995, p. 60). Leda here in Figure 5, as the informative figure, is not bounded and imprisoned by the swan, and she pulls her clothes and steps forward, showing a kind of independence, liberation, and resistance against the swan (or the god, or man). This emergence of the feminine consciousness and the individual performance are also related to the Vestals revival at that time. In Augustus’ religious revivalism, he restored public monuments, especially the temples of the gods to revive religion and “reshape Roman memory” (Orlin 2007, p. 74). In order to do this, he promoted the priesthoods and celebrated the past ceremonies and festivals, in which some religious rituals could be held only by women—the famous Vestals who were given high-status and independence. As a matter of fact, both Ovid’s poems and Augustus’ religious reforms had a great influence on the art creations in Rome, which makes this mosaic an erotic and ascetic mixture.

2.3. Asceticism and Humanism: Leda and the Swan in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance

During Augustus’ religious reforms, lots of pornographic paintings or poems were banned and destroyed. At the same time, a kind of religious asceticism was gradually prevalent in Medieval Europe with the spread of Christianity. Although Leda and the Swan had become a household story in Medieval Europe, but few arts of it, especially the paintings, in that time were remained until the Renaissance in the 14th century. The asceticism on sexuality in the Middle Ages can be traced back to ancient Greece and Roman times. Plato claimed that “the body causes evil” and the evil that it causes is “disorder” or disunity, or lack of harmony (Wagoner 2019, p. 78). In the Phaedo, Socrates deemed that, “as long as we have a body and our soul is fused with such an evil we shall never adequately attain what we desire, which we affirm to be the truth” (qtd. Cooper 1997, p. 57). Thus, Socrates emphasized that we must strive to purify ourselves from our body as much as possible while we are alive. The Stoics in ancient Rome also viewed that “fleshly lusts” could make human beings become “the principal accomplice” in their own “captivity”, so they needed to be temperate because “each pleasure and pain is a sort of nail which nails and rivets the soul to the body” (Russell 2004, p. 140). Sexual desire, a libido, thus is regarded as a poison, rooted in the body and soul, and is the parent of all evils, which prevents human beings from acquiring knowledge and getting progress and should be in control.

In Genesis,19 God created Adam and took one of his ribs from his flesh to make a woman, Eve. Lured by the serpent, Eve ate the fruit from the tree that was pleasant to her eyes and was desired to make one wise, and she gave one to Adam. Then, God sent Eve and Adam forth from Eden, and made Eve be ruled by her husband and be in pain in order to bring forth children. From this perspective, woman is actually the flesh from man, and woman’s desire can be a manifestation of man’s lust. Thus, there are the virtues of renunciation, asceticism and restraint in the Old Testament days. Meanwhile, woman is also regarded as the origin of evil. Later, in Medieval Europe, women were often seen as the incarnation of sex and desire in Christianity, and their sexual desires are thought to be much stronger than men’s. In this way, the condemnation of sexuality inevitably leads to the discrimination and prejudice against women, and many artistic nude paintings of women and even men were excluded and condemned. Besides, in the Old Testament, there are many specific definitions of adultery, promiscuity, and indecency, and the corresponding severe punishments. For example, “Whosoever lieth with a beast shall surely be put to death” (Exodus 22: 19). Meanwhile, Christians are also required to abstain from ideological obscenity “that whosoever looketh on a woman to lust after her hath committed adultery with her already in his heart” (Matthew 5: 28). In Aurelius Augustine’s view, among all kinds of desires of human, the strongest is “sexual desire”, while the desire of ruling is the main enslaver of reason, will, emotion, and soul freedom (Ruokanen 2008, p. 6). So, the sexual desire and ruling desire of men toward women are evil self-performances, or just sins. Some godfathers even regarded marriage as the main means of lust and the continuation of human weakness, which gives rise to a kind of extreme asceticism in Christian religion at that time.

Having gone through long dreariness, in the Renaissance, the artists, poets, and writers held the great banner of “humanism” to revive the classical literature, culture, and art of ancient Greece and Rome. Most humanists of this period are religious and concerned to “purify and renew Christianity, rather than eliminate it” (McGrath 2013, pp. 85–86). Their works seek to get rid of the bondage of the religion on people’s thoughts, and advocate the liberation of the human mind, spirit, and nature. For example, Dante wrote Divine Comedy to criticize the religious obscurantism in the Middle Ages and express his pursuit of truth and knowledge; Boccaccio released Decameron to condemn the asceticism in the Catholic Church and praise love as the source of noble sentiment; while Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) and Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564) also created many works about the myth and religion in ancient Greece and Rome to express their religious appeals. Hence, Leda and the Swan was again picked up and painted. Unfortunately, both the original paintings of Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo have been lost or destroyed without knowing the reasons, possibly due to the erotic depictions that were still banned and not accepted at that time. The versions of Leda and the Swan preserved today are the sketches of Leonardo da Vinci’s and Michelangelo’s, while others are all the imitations or copies by later generations. However, through these copies, some of their religious appeals and ethical ideas in the original works can still be found.

In Leonardo da Vinci’s paintings or drawing sketches, there are few nude paintings of women, and his painting themes are basically related to religious content or secular life, like The Last Supper or Virgin of the Rocks, rarely involving mythology. However, Leda and the Swan is an exception, which makes us wonder why he chooses such a subject that seemingly deviates from his personality and interests. In Figure 6, Leda is the dominant figure. Her body is fully-naked and well-shaped, seemingly graceful and beautiful, serving as a challenge to the religious asceticism in Christianity. A black or gray swan stands beside Leda with his wings spread. He stretches the neck towards Leda, while Leda grabs the swan’s neck with her left hand and puts her right hand around the bottom of the swan’s neck, as if she controls the swan. Now, the naked Leda is facing toward the audience, located at the front without being restrained and oppressed like that in Figure 3, and not represented as equal in size, or placed at equal distance or oriented in the same way as the swan. This is an affirmation of the release of human nature. At the left of Leda’s feet, there are two broken eggs, and out of the eggs are four little children, which makes the whole story of Leda and the Swan complete and clear. The four children all look up with love at Leda; while Leda, slightly lowered, tilts to watch them, with a kind of Mona Lisa smile on her lips. There are flowers and grass surrounding them, making the whole picture natural and harmonious.

Figure 6.

Oil on canvas of Leda and the Swan, a copy by Cesare da Sesto after a lost original by Leonardo da Vinci, 1515–1520, © Wilton House, England.

This depiction belongs to the third part of the myth—the birth of a new life, full of love and peace. It is said that during or before the painting of Leda and the Swan, Leonardo da Vinci had “executed preparatory studies not only for the figures but also for a variety of marsh, field and woodland wild flowers” (Meyer and Glover 1989, p. 75). Charles Nicholl, in his biography, mentions that Leonardo’s zest for natural plants expresses “an idea of nature as the wounded, exploited victim of man’s rapacity” (Nicholl 2004). In addition, Leonardo has always been engaged in “anatomy” and tries to “understand how the human body worked, not just the bones and muscles, but nerves and heart and that mysterious, ominous, dangerous topic: the origin of human life in sex and the sublife of the foetus”, so this picture has often been seen as a “personification of nature and of the forces of natural life” (Keller 2006, p. 14). However, the birth of a new life (or its happiness) is just one part of this painting. More importantly, some religious thoughts embodied in it are worth discussing. Firstly, in Figure 6, the body color of the black or gray swan is in sharp contrast to the white or light Leda.20 The swan in ancient Greece and Rome is usually depicted as white and beautiful so that he can seduce Leda, but here the black or gray color serves as a symbol of evil, representing a kind of original sin from patriarchy, because in the Bible, Eve is just the personification of Adam’s rib, thus the evil or sin indeed comes from Adam, not Eve, or not the women. Leonardo here uses this to allude to the asceticism and prejudice against women in the Middle Ages. The white naked Leda can be regarded as woman’s natural state and innocence, a kind of liberation from man. Besides, Leda grabs the swan’s long neck and there is a garland on the swan’s neck, indicating the control and confinement of desire and evil.21

Secondly, the four children out from two broken eggs are the subservient elements in this painting. Sometimes, compared to the dominant position in the center, “communication” can be a marginal phenomenon (Kress and Van Leeuwen 2006, p. 196). So, the broken eggs and four children deliver some thoughts that Leonardo holds inside to his potential audience. In ancient Rome, the myth that “Leda lays two eggs” makes the egg have the meaning of “beginning” in the language usage. The ancient Romans often say “start from the beginning” as “start from the egg”, which is possibly because the ancient Romans always ate eggs first at meals. Here, Leonardo paints the broken eggs, implying that he is thinking about how to find a new start—to purify and renew the asceticism and darkness of Christianity in the Middle ages, or to release human nature and thoughts. The naked Leda, in fact, brings this painting back to the ancient Greek and Roman time, and also symbolizes a new start. It is not about the erotic, but a display of the essence, which represents the removal of the appendages covered on human body, and refers to returning to the essence and facing it directly—through nudity, people regain the essence of life and become permanent (Jullien 2000). This manifestation of the essence, or the reduction from the essence of the body, will be pure and non-desirous as the filtration of lust. From the presentations of the contrast of the color, the birth of a new life, and the release of human nature, Leonardo advocates the struggle against the restraint on the ascetic thoughts in Christianity in the Middle Ages, strives for human values and looks forward to a new start. Afterward, beginning from Michelangelo’s painting, for a long time, the eggs and children almost disappeared in the creations of Leda and the Swan. There is only the rape scene, and Leda is no longer chained, but emancipated and immersed in the joy of sexual love, which is the ultimate performance of advocating human nature under the guiding theme of humanism.

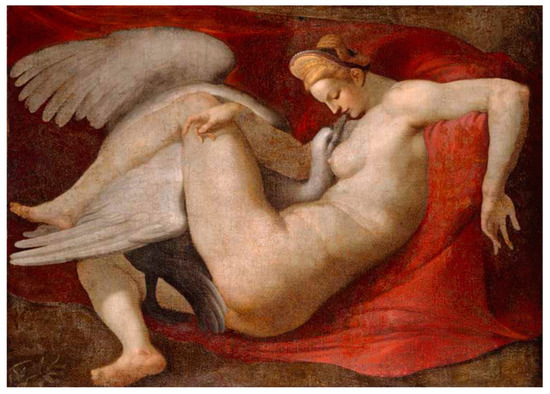

Michelangelo’s works are often about Christian mythology, linked with beauty, power, and passion. He is both a humanist artist and a devout Christian. Michelangelo advocates “a paradigm of human salvation through purgation and contemplation” and views “redemption as the consequence of an instantaneous and metaphysical transformation” (Prodan 2014, p. 4). Hence, when looking at Michelangelo’s works, people will not only get an instant perception of the image but also stay to think about the story behind it. In Figure 7, the naked Leda occupies a large space. The redness of Leda’s cheeks, the visible erection of the exposed nipple of her left breast, the comfort of her face, the extension of her fingers, and the relaxation of her muscles all show that Leda is deeply immersed in the joy of love-making with the swan. This is the consequence of an instantaneous perception: a full display of the liberation of human nature, completely contrary to the asceticism in the Middle Ages. In detail, Leda’s skin is pure and beautiful; her muscles are loose but vigorous, and her blonde hair is curly. Leda is lowering her head to kiss the beak of the swan with her cheeks flushed and one leg on the swan’s back, which means that she takes the initiative to have the intercourse with the swan; while the swan, standing between Leda’s legs, is leaning over Leda’s body with his feet and tail dark and dim in the bottom. The dark part is a symbol of evil—the sexual desire, deserving our careful thinking, similar to Leonardo da Vinci’s creation. However, this intercourse between the swan and Leda actually displays the love between human and animal. Leda’s obsession with the swan represents her ethical choice influenced by her Sphinx factor. Here, Leda’s animal factor indeed prevails over her human factor, so she has become an irrational animal driven by her free will, only for the pleasures of her primitive love and sexual desire. Thus, Figure 7 vividly recreates and records the erotic aspects and ethical ideas embodied in the art and literature of Leda and the Swan in ancient Rome.

Figure 7.

A 16th-century copy of Leda and the Swan after a lost painting by Michelangelo, © National Gallery, London.

2.4. Feminine Consciousness and Ethical Choice: Leda and the Swan in the 20th Century

After the Renaissance, with the rise of the Enlightenment in Europe, humanism (or liberalism) gradually reached a climax, and various versions of Leda and the Swan appeared. However, except for a few of Leonardo da Vinci’s contemporaries or his students, most of the artists, no matter what era, school, or style they belonged to, all focused on the erotic rape scene—the second part of the story, or the theme of giving birth to new beings. In the 19th century to 20th century, Leda and the Swan eventually attracted the attention of the poets and writers, who then started to create and release their works. Among them, the most famous and influential work is Irish poet W.B. Yeats’s Leda and the Swan in 1928. Notably, though, there are also some female poets writing for Leda and the Swan, like the American poet Sylvia Plath in 1962, the British poet Barbara Bentley in 1996, and others. In Gotthold Ephraim Lessing’s view, a painting “represents one simultaneous static relation of objects in space, whereas poetry imitates successive objects occurring in time” (Schütze 1920, p. 292). So, the artists can only draw one scene in the myth of Leda and the Swan, and what they choose might be the most intriguing and imaginative moment in all the actions; but differently, poetry can “develop a sequence of images that cannot avoid forming a minimal narrative” (Wallenstein 2010, p. 4) and can make the depictions in the painting a series of actions, which will inevitably show more thoughts and emotions, whether religious, ethical, or cultural, under the poet’s imagination. Therefore, the story of Leda and the Swan in the poetry will be dynamic, vivid and lively.

Yeats’s Leda and the Swan, written in Shakespearean sonnet, was first published in The Dial in 1924, and the original version of the poem was called “Annunciation”.22 In Christian tradition, the Annunciation is the announcement given by the Archangel Gabriel to the Blessed Virgin Mary, telling her that she would give birth to a child by the Holy Spirit in the form of a dove (Luke 1: 26–38). From this perspective, Yeats observes the rape dominated by Zeus in the form of a swan as an event parallel to the Annunciation to the Virgin Mary. The result of such union between the divine and human is Helen (or Jesus Christ), whose birth signals the destruction of an old order and ushers in a new era and a Greek (or Christian) civilization (Babaee and Wan Yahya 2014, p. 170). This sometimes is seen as a projection of Yeats’s religious and ethical thoughts. According to W.B. Yeats, art that includes mythology can reflect civilization, as it “seeks to impose order and comprehensibility upon the diversity and chaos of the experiential world” (Thanassa 2010, p. 114). As an Irish cultural-nationalist poet, Yeats combats the oppression of Ireland under the British rule. His revisions of Leda and the Swan can demonstrate his efforts for the post-colonial emerging Irish Free State. So, through the character Leda, “one can interpret Yeats negotiating his political investments in Western civilization as an Irish colonial subject symbolically raped by England” (Neigh 2006, p. 147). Besides, during the period that Yeats wrote the poem, Ireland was heavily regulated by the Catholic Church—sexuality was stifled, and the voice of women was largely in a state of silence. The title of “Annunciation” can be an allusion or attack to the Catholic Church, expressing Yeats’s ethical appeal for the reconstruction of social religious and ethical order for a new start—“an active reconstruction of that which fate destroys” (McKenna 2011, p. 425). Lady Augusta Gregory in her journal writes, “Yeats talked of his long belief that the reign of democracy is over for the present, and in reaction there will be violent government. [...] It is the thought of this force coming into the world that he is expressing in his Leda poem” (Foster 2003, p. 243).

In fact, Yeats’s poem is also linked with Leda’s ethical choices under the swan’s violence and rape, alluding to Ovid’s poems and showing “a significant subversive potential for women to fight up against patriarchy” (Chang 2017, p. 60). It foregrounds the mastery of the swan over Leda, and Leda’s complicity in this rape—“her erotic arousal or being in the grip of desire is indicated by her being caught up in the sexual act” (Neimneh et al. 2017, p. 34). Consisting of 15 lines, the poem is divided into three stanzas. The first stanza describes the swan’s sudden attack and Leda’s helplessness. The second stanza pictures Leda’s panic and her choices with a beating heart. The third indicates the disastrous consequences of the fall of Leda, namely the Trojan War and the destruction of Troy; and Yeats’s doubt about whether Leda can gain some wisdom or strength from the swan:

A sudden blow: the great wings beating stillAbove the staggering girl, her thighs caressedBy the dark webs, her nape caught in his bill,He holds her helpless breast upon his breast.How can those terrified vague fingers pushThe feathered glory from her loosening thighs?And how can body, laid in that white rush,But feel the strange heart beating where it lies?A shudder in the loins engenders thereThe broken wall, the burning roof and towerAnd Agamemnon dead.Being so caught up,So mastered by the brute blood of the air,Did she put on his knowledge with his powerBefore the indifferent beak could let her drop?(Yeats 2008, p. 182)

The first line describes the behaviors and physical characteristics of the swan. “A sudden blow” and “the great wings beating” foreground a strong sense of conquest, revealing the irresistible power of the swan. Then, the word “above” is more straightforward to highlight the relationship between Leda and the swan. Leda appears as a “staggering girl”, not completely obedient to the invasion of the swan, which, in fact, indicates a kind of resistance or reluctance in Leda’s mind. So far, the swan is reinforced as the central focus, an aggressive and violent attacker; while Leda is presented as an unwilling, non-passive, self-aware victim. Immediately, a series of actions and scenes, like “her thighs caressed”, “her nape caught in his bill”, and “he holds her helpless breast upon his breast”, suggest that the swan completely controls Leda’s body. Confronted with a sudden attack of powerful force and the instant oppression from the swan, Leda shows her horrors of “the dark webs” and feels “helpless”. This is because her human factor controls her animal factor. No matter how forceful the swan is, he does not completely conquer the girl. Now, Leda’s human factor prevails over her animal factor, or her rational will restricts her free will. She has ethical consciousness and the ability to distinguish between good and evil.

In the second stanza, Leda’s “terrified vague fingers” and her “push” imply that Leda tries to control her free will and resist the seduction of the swan. She hopes to get a balance between her rational will and free will. Moreover, the word “vague” itself also demonstrates that Leda’s body movements are slow and indecisive, which seems to be a refusal or a welcome. In the sixth line, Leda begins to change from the resistance—the natural instinct against the external forces—to compliance. It is a kind of animal instinct to follow the temptation. For example, the “feathered glory” is perhaps “a symbol of the phallus, making Leda get lost in a scene of hybridity” (Neigh 2006, p. 150), and the “loosening thighs” contain a kind of self-exile or self-indulgence, a kind of non-confrontational and welcoming state of the swan’s invasion. In the front of the swan’s seduction, Leda’s animal factor starts to germinate and swell, but at first, her ethical consciousness still reminds her that the intercourse between human and animal is against the ethical norms. However, in the face of the strong and aggressive oppression of the swan, Leda’s aphasia as a weak girl and desire for sex and love set obstacles for her ethical choice, which makes her fall into the ethical predicament of rejection or acceptance. Eventually, Leda’s animal factor bursts out uncontrollably. The words “laid in that white rush” and “strange heart beating” allude to Leda’s “free will” driven by her animal factor. Leda gradually gets rid of her rational will and loses in the pursuit of carnal desire. Finally, in the third stanza, with the free will released thoroughly, Leda makes her ethical choice—“a shudder in the loins” and becomes an irrational animal controlled by her animal factor. Then, Leda has sex with the swan and violates the ethical norms, which destroys the religious and ethical order. Thus, Leda plants the seeds of tragedy: “The broken wall, the burning roof and tower/And Agamemnon dead”. Just like in Greek mythology, Leda gives birth to Helen and Clytemnestra, who bring disastrous destruction to people’s lives.

Nevertheless, “the broken wall, the burning roof and tower” in the poem also symbolizes the collapse of the power or patriarchy. It expresses Yeats’s hope for the returning of Leda’s ethical consciousness and rational will from the strong violence originally depicted. Therefore, in the twelfth line, Yeats uses some blank space to distinguish the next lines from the above lines, and adopts a completely different tense and voice to propose his thoughts of Leda’s future. The first 11 lines are written in the present tense to emphasize the current situation of the event, so that the reader can feel as if they are personally on the scene, and the whole process is vivid; while the last three lines are created in the past tense to highlight the reflection of the event (Wang 2012, p. 40). Different tenses separate the definite fact from the uncertain reflection. In the last two lines, Yeats puts forward his confusion—“Did she put on his knowledge with his power/Before the indifferent beak could let her drop?”—to express his hope for Leda’s rebirth. As Yeats always longs for “spiritual redemption through the timelessness of art” (Ross 2009, p. 214), Yeats imagines that Leda will be wakened from her lust. He hopes that Leda’s human factor can return and restrain the animal factor, and her rational will and ethical consciousness can be back. Just like Adam and Eve, they are lured by the animal and eat the forbidden fruits from the tree of knowledge of good and evil; even though Adam and Eve are punished and driven out from their paradise, they get the wisdom or knowledge to distinguish between good and evil (Nie 2014, p. 35). They liberate themselves from the animal by using the fig leaves to cover their naked bodies, and they control their free will so as to come out from the ignorance and indulgence and become persons who have ethical consciousness, then to complete the ethical choice, and start a new life.

On the contrary, American poet Sylvia Plath answers Yeats’s question by portraying Leda as a traditionally passive and feminine victim in the rape as well as the patriarchy. Her poem Three Women: A Poem of Three Voices in 1962 is a combination of three poetic monologues, respectively, from a wife, a secretary, and a girl, revealing three different attitudes of women toward pregnancy, delivery, and infertility in a patriarchal world. The first voice is from a wife, and she has a successful natural delivery. Even though she is afraid of fertility, she believes that bearing children is a woman’s instinct—“I accomplish a work” (Plath 1981, p. 180). When the baby is born, she is full of tenderness and happiness: “I have never seen a thing so clear./His lids are like the lilac-flower/And soft as a moth, his breath/I shall not let go” (p. 181). The second is from a secretary, and she suffers a miscarriage: “I lose life after life. The dark earth drinks them” (p. 181). She feels a lack of enthusiasm and thinks she cannot control her life. However, when she comes back at home, she sees her husband is reading quietly; then she finds everything is beautiful and picks up the hope for life: “A tenderness that did not tire, something healing” (p. 186). Different from the ecstasy and pain of childbirth, the third voice is about the anxiety and fear of pregnancy after the rape, just as what Susan Brownmiller (1975, p. 391) writes, “rape is not a crime of irrational, impulsive, uncontrollable lust, but is a deliberate, hostile, violent act of degradation and possession on the part of a would-be conqueror, designed to intimidate and inspire fear.” This girl is often considered to be that of a college student who is impregnated, where Plath uses the myth of Leda and the Swan to describe it:

I remember the minute when I knew for sure.The willows were chilling,The face in the pool was beautiful, but not mine—It had a consequential look, like everything else,And all I could see was dangers: doves and words,Stars and showers of gold—conceptions, conceptions!I remember a white, cold wingAnd the great swan, with its terrible look,Coming at me, like a castle, from the top of the river.There is a snake in swans.He glided by; his eye had a black meaning.I saw the world in it-small, mean and black,Every little word hooked to every little word, and act to act.A hot blue day had budded into something.(Plath 1981, pp. 177–78)

The girl’s voice is related to “dangers”, with horror, anxiety, and disgust. The “showers of gold” is an allusion to the classical myth of Danae, who was impregnated by Zeus against her will. The swan with a “white, cold wing” is in a terrible look, and “the snake in swans” can be a traditional phallic symbol, or a symbol of evil in the Bible, which suggests the rape (Novales 1993, p. 41). Those all show that the girl’s pregnancy is not voluntary, and there is an irresistible force toward her. Since the girl is not ready for pregnancy, she has no reverence of giving birth. Thus, she worries about “what if two lives leaked between my thighs?” (Plath 1981, p. 180) and constantly asks herself “what is it I miss?” (p. 186). However, no one answers her and the swan goes away irresponsibly. So, “she is crying, and she is furious.” (p. 182). She sees the world in a “dark” meaning: “They are black and flat as shadows” (p. 186). Plath writes from the angle of Leda to present the girl’s fear and pain in the face of a sudden violent rape. She stresses the girl’s anxiety of childbirth, which actually happens in every girl. This is also a kind of portrayal of Plath’s own life, representing the women who are under repression but gradually become awake to revolt against patriarchy. Plath’s father died when she was a little girl. She grew up during World War II and in the shadow of patriarchy, where her thoughts are seduced and raped. Plath loved his father, but the highly publicized patriarchy had resulted in the obedience of traditional women to male chauvinism. The poet’s anxiety and fear in living in the society without a father gradually turned out to be distaste and hatred. In Plath’s later poem Lady Lazarus, the last line “And I eat men like air” (p. 247) shows that women are “dangerous” and they can also do harm to men. Thus, Plath “declares a war by calling on all women to be merciless toward those who threaten them” (De Assis 2007, p. 48). The next year after Plath wrote this poem, she decided not to be a passive “Leda” and committed suicide so as to get a kind of initiative for her own life in the way of death as a rebirth. However, it is undeniable that such a choice is negative, rather than that of the girl in the poem who finally returns to university and starts her life again—“I had an old wound once, but it is healing” (Plath 1981, p. 185).

After the release of Plath’s Three Women: A Poem of Three Voices, there are more and more women poets writing Leda and the Swan to emphasize Leda’s sufferings in a patriarchal society or her ethical choices after the rape. For example, Mona Jane Van Duyn’s Leda in 1971 describes Leda’s degradation: “in men’s stories her life ended with his loss” and answers Yeats’ question—Leda does not become stronger and more knowledgeable after the violation, but eventually she has recognized the difference between her and the swan (or god) and then “she married a smaller man with a beaky nose,/and melted away in the storm of everyday life” (Kossman 2001, p. 17). In Lucille Clifton’s Trilogy Leda 1, Leda 2, and Leda 3 in 1993, the poet highlights Leda’s sense of loss and abandonment as she lives alone in the backside of a village and has the recurring dreams about Zeus’ rape: “and at night my dreams are full/of the cursing of me” (Clifton 1993, p. 59). Nina Kossman’s Leda in 1996 depicts Leda’s fear and helplessness: “She recalled the fear that had overwhelmed her soul,/something had seized her throat so she couldn’t cry/out to them” and “the familiar landscape fleeing from her cry for help” (Kossman 2001, p. 18). Moreover, in Barbara Bentley’s Living Next to Leda in 1996, Leda is portrayed as a traumatized victim and has apparently become “mentally ill” after the rape (Neimneh et al. 2017, p. 39). So far, Leda and the Swan is no longer a common representation in paintings or literature mainly depicted by male artists, who focus on the violent rape of the swan, or the complicity of Leda influenced by her patriarchal worship or animal factor, and how their intercourse empowers Leda or results in the birth of a new life; instead, it gradually becomes an ethical appeal for the awakening of feminine consciousness—to revolt against patriarchy and to become strong and independent in social and religious life.

3. Conclusions

From the ancient Greek vase paintings to contemporary English poems, the myth of Leda and the Swan has been gradually rewritten, reviewed, and revalued by history, religion and social ethics. The interaction between Leda and the swan goes from divinity in ancient Greece to humanity in the Renaissance, showing the tendency of life and secularization in the contemporary world, increasingly out of the cage of eroticism prevailed in ancient Rome and the Middle Ages. Besides, Leda, as a representative of the victims of patriarchy and religious persecution, goes from bondage to liberation with more and more voices representing Leda’s sufferings—fears, anxiety, as well as helplessness, which can be the manifestation of the rise of feminine consciousness and the gradual collapse of patriarchy; while the attacker swan, an incarnation of power and desire, becomes an object of condemnation due to his violent rape and sexual desire. Although there are various religious projections and ethical appeals to the same event of Leda and the Swan in different historical periods, there are some things in common. Those are, firstly the religious concept on motherhood or the birth of a new life, such as Figure 2, Figure 4 and Figure 6; secondly, the ethical enlightenment of the occurrence of the rape, especially on Leda’s ethical choice. There is nothing so beautiful as the birth of a new life, but by highlighting the ethical tragedy of the Trojan War, Leda and the Swan warns us that as an individual of Sphinx factor, a person’s human factor can control and restrain the animal factor, but that the animal factor can also be stimulated by free will or irrational will. Once it is out of control, breaking the religious order or violating the ethical taboo, there will be punishment and the tragedy is inevitable. This “instruction” is the essential attribute and first function of literature or art (Nie 2014, p. 14). Furthermore, when confronted with violence and power, regardless of sex or other things, women should not give themselves up; instead, they should face up to their own ethical and religious identities so as to make correct choices to start a new life.

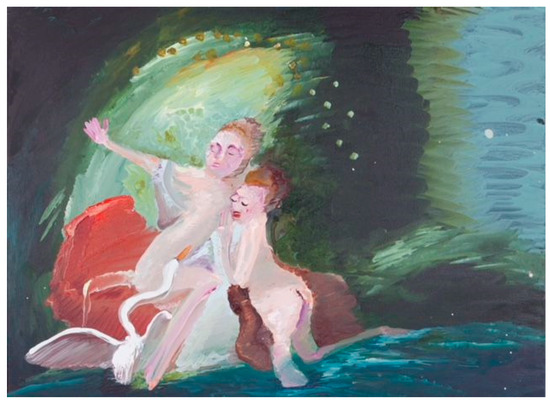

However, as for who is the victim and who should be condemned in the story of Leda and Swan, there are various religious and ethical standards in different times, mirroring the development and evolution of religious rules and ethical orders in the historical process. Walter Benjamin once mentioned that, “The genuine picture may be old, but the genuine thought is new. It is of the present. This present may be meager, granted. But no matter what it is like, one must firmly take it by the horns to be able to consult the past. It is the bull whose blood must fill the pit if the shades of the departed are to appear at its edge” (qtd. Arendt 2019, p. lvi). As Mircea Eliade summarizes, “myth is a ‘living thing’, where it constitutes the very ground of religious life; in other words, where myth, far from indicating a fiction, is considered to reveal the truth par excellence” (Eliade 1969, p. 73). Thus, myth can provide the most significant lessons for religious people, helping them return to the sacred origins, get rid of sins, and become renewed by participating in the primordial events with the times. For hundreds of years, the myth of Leda and the Swan has been continuously interpreted and recreated. In the modern era, the great changes of society and the corresponding religious and ethical environment also give Leda and the Swan some new meaning, such as in Figure 8. This painting foregrounds Leda and her child, who embrace together, while the swan is marginalized in a weak position. It can be seen that the child is no longer a baby, but a growing teenager. Both Leda and the child look at the same place, and Leda outstretches one of her hands, seemingly pointing out a direction for the child. When the violence and power of the swan gradually fade away, and the patriarchy falls apart, what kind of story of Leda and the Swan will be performed among the growing children? The previous generation provides experience for the next generation, and the tradition paves the way for the future, which probably makes Leda and the Swan a cross-era classic, going beyond nations and times.

Figure 8.

Acrylic on canvas of Leda and the Swan (after Boucher), 2018, © Genieve Figgis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.T. and X.C.; writing—original draft preparation, S.T. and A.P.; writing—review and editing, S.T., A.P. and X.C.; supervision: X.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the reviewers for their patient reading of the manuscript and valuable suggestions. We are grateful for the related museums, photographers and artists for the permission to use the paintings for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Apostolos-Cappadona, Diane. 2017. Religion and the Arts: History and Method. Brill Research Perspectives in Religion and the Arts 1: 1–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, Hannah. 2019. Introduction: Walter Benjamin: 1892–940. In Illuminations: Essays and Reflections. Translated by Harry Zohn. Edited by Hannah Arendt. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, pp. vi–lxiii. [Google Scholar]

- Babaee, Ruzbeh, and Wan Roselezam Wan Yahya. 2014. Yeats’ “Leda and the Swan”: A Myth of Violence. International Letters of Social and Humanistic Sciences 27: 170–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Frank Burch. 2014. Introduction: Mapping the Terrain of Religion and the Arts. In The Oxford Handbook of Religion and the Arts. Edited by Frank Burch Brown. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Brownmiller, Susan. 1975. Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape. New York: Ballantine Books. [Google Scholar]

- Burkert, Walter. 1985. Greek Religion. Translated by John Raffan. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Tsung Chi Hawk. 2017. Women, Power Knowledge in W.B. Yeats’ “Leda and the Swan”. Journal of Comparative Literature and Aesthetic 40: 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Clifton, Lucille. 1993. The Book of Light. Washington, DC: Copper Canyon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, John M. 1997. Plato: Complete Works. Indianapolis and Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Cullingford, Elizabeth Butler. 1994. Pornography and Canonicity: The Case of Yeats’s “Leda and the Swan”. In Representing Women: Law, Literature, and Feminism. Edited by Susan Sage Heinzelman and Zipporah Batshaw Wiseman. Durham and London: Duke University Press, pp. 165–87. [Google Scholar]

- De Assis, Luis Alfredo Fernandes. 2007. Sylvia Plath’s Fragmentation in the Voices of “Three Women”. Revista Ártemis 7: 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon, Matthew. 2003. Girls and Women in Classical Greek Religion. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- DiLuzio, Meghan. 2019. Religion and Gender in Ancient Rome. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Catharine. 1993. The Politics of Immorality in Ancient Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eliade, Mircea. 1969. The Quest: History and Meaning in Religion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, Robert Fitzroy. 2003. W. B. Yeats: A Life II: The Arch-Poet 1915–39. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fulgentius, Fabius Planciades. 1971. Mythologies. Translated by Leslie George Whitbread. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gaca, Kathy L. 2003. The Making of Fornication: Eros, Ethics, and Political Reform in Greek Philosophy and Early Christianity. Berkeley and London: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, Jane F. 1991. Women in Roman Law and Society. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gavins, Joanna. 2012. Leda and the Stylisticians. Language and Literature 21: 345–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetting, Cody. 2017. A Comparison of Ancient Roman and Greek Norms Regarding Sexuality and Gender. Honors Projects 211: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, Robert. 1988. The Greek Myths. New York: Moyer Bell. [Google Scholar]

- Grimal, Pierre. 1986. The Dictionary of Classical Mythology. New York: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Hua. 2018. “Leda and the Swan”’s Revisions: A Cognitive Stylistic Analysis. International Journal of English Linguistics 8: 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Anna Maria. 2018. Brute Blood: On Reading William Butler Yeats’s “Leda and the Swan”. Ecotone 13: 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honko, Lauri. 1984. The Problem of Defining Myth. In Sacred Narrative: Readings in the Theory of Myth. Edited by Alan Dundes. London: University of California Press, pp. 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hurley, Michael D. 2009. How Philosophers Trivialize Art: Bleak House, Oedipus Rex, “Leda and the Swan”. Philosophy and Literature 33: 107–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, King. 2000. The Holy Bible. New York: Bartleby.com. Available online: https://www.bartleby.com/108/ (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Jullien, François. 2000. De L’essence Ou Du Nu. Paris: Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Kamenka, Eugene. 2015. The Ethical Foundations of Marxism (RLE Marxism). London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, Alex. 2006. Was Leonardo a Christian? History Today 56: 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kossman, Nina. 2001. Gods and Mortals: Modern Poems on Classical Myths. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kowaleski-Wallace, Elizabeth. 2009. Encyclopedia of Feminist Literary Theory. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, Gunther, and Theo Van Leeuwen. 2006. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design, 2nd ed. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, Jennifer. 2013. Sexuality in Greek and Roman Religion. In A Companion to Greek and Roman Sexualities. Edited by Thomas K. Hubbard. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 214–29. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, Alister E. 2013. Historical Theology: An Introduction to the History of Christian Thought, 2nd ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, Bernard. 2011. Violence, Transcendence, and Resistance in the Manuscripts of Yeats’s “Leda and the Swan”. Philological Quarterly 90: 425–44. [Google Scholar]

- Medlicott, Reginald Warren. 1970. Leda and the Swan—An Analysis of the Theme in Myth and Art. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 4: 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Barbara Hochstetler, and Alice Wilson Glover. 1989. Botany and Art in Leonardo’s Leda and the Swan. Leonardo 22: 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neigh, Janet. 2006. Reading from the Drop: Poetics of Identification and Yeats’s “Leda and the Swan”. Journal of Modern Literature 29: 145–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimneh, Shadi S., Nisreen M. Sawwa, and Marwan M. Obeidat. 2017. Re-tellings of the Myth of Leda and the Swan: A Feminist Perspective. Annals of Language and Literature 1: 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Newlands, Carole Elizabeth. 1995. Playing with Time: Ovid and the Fasti. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholl, Charles. 2004. Leonardo da Vinci: Flights of the Mind. London and New York: Viking Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, Zhenzhao. 2010. Ethical Literary Criticism: Its Fundaments and Terms. Foreign Literature Studies 32: 12–22. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, Zhenzhao. 2011. Ethical Literary Criticism: Ethical Choice and Sphinx Factor. Foreign Literature Studies 33: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, Zhenzhao. 2014. Introduction to Ethical Literary Criticism. Beijing: Peking University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Novales, Marta Pérez. 1993. The Theme of Female Creativity in Sylvia Plath’s “Three Women. A Poem for Three Voices”. Bells: Barcelona English Language and Literature Studies 4: 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Orlin, Eric M. 2007. Augustan Religion and the Reshaping of Roman Memory. Arethusa 40: 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Rong, and Xiaofang Liu. 2017. “Leda and the Swan”: Ekphrastic Interaction of the Sister Arts. Foreign Literature Studies 39: 108–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ovid, Publius N. 1922. Metamorphoses. Translated by Brookes More. Boston: Cornhill Publishing Company. Available online: https://www.theoi.com/Text/OvidMetamorphoses1.html (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Ovid, Publius N. 1931. Heroides. Translated by Grant Showerman. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Available online: https://www.theoi.com/Text/OvidHeroides1.html (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Ovid, Publius N. 2014. The Amores, or Amours. Translated by Henry T. Riley and Produced by David Widger. December 16, The Project Gutenberg Ebook. Available online: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/47676/47676-h/47676-h.htm (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Plath, Sylvia. 1981. The Collected Poems. Edited by Ted Hughes. New York: Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- Prodan, Sarah Rolfe. 2014. Michelangelo’s Christian Mysticism: Spirituality, Poetry and Art in Sixteenth-Century Italy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, David A. 2009. Critical Companion to William Butler Yeats: A Literary Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File. [Google Scholar]

- Ruokanen, Miikka. 2008. Theology of Social Life in Augustine’s City of God. Beijing: China Social Sciences Press. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, Bertrand. 2004. History of Western Philosophy. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Scheid, John. 2005. Augustus and Roman Religion: Continuity, Conservatism, and Innovation. In The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Augustus. Edited by Karl Galinsky. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 175–94. [Google Scholar]

- Schütze, Martin. 1920. The Fundamental Ideas in Herder’s Thought. II. Modern Philology 18: 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, William. 1867. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Vol. II. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Sofroniou, Andreas. 2017. Mythology Legends from Around the Globe. Morrisville: Lulu Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thanassa, Maria. 2010. In the Embrace of the Swan: The Poetry and Politics of Corruption in Yeats and Lawrence. In In the Embrace of the Swan: Anglo-German Mythologies in Literature, the Visual Arts and Cultural Theory. Edited by Rüdiger Görner and Angus Nicholls. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter, pp. 111–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wagoner, Robert. 2019. Two Views of the Body in Plato’s Dialogues. Journal of Ancient Philosophy 13: 74–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallenstein, Sven-Olov. 2010. Space, Time, and the Arts: Rewriting the Laocoon. Journal of Aesthetics & Culture 2: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Qi. 2012. “Leda and the Swan”: Yeats’ Subversion of the Traditional Western Narration. Foreign Language and Literature 28: 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Yeats, William Butler. 2008. The Collected Poems of W.B. Yeats. London: Wordsworth Editions Ltd. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | See The Ethical Foundations of Marxism (Kamenka 2015, pp. 134–35). It firstly appears in Karl Heinrich Marx’s Grundrisse in 1844. |

| 2 | There are many variations to the myth of Leda and the Swan. The version of Leda and the Swan in this paper is one of the most famous and generally accepted folktales in Greek mythology; while some other versions sometimes identified Leda as Nemesis (Graves 1988, The Greek Myths, p. 126), or claimed that Leda loved Zeus and was willing to have sex with him (Grimal 1986, The Dictionary of Classical Mythology, p. 255). |

| 3 | The god Zeus as a man who seduces or rapes Leda as a woman sometimes is regarded as a manifestation of the rudiment of religious order and patriarchy. In this patriarchal society, “Zeus is fully in command of everything whereas Leda is a helpless victim” (Neimneh et al. 2017, p. 38), and “the birth of Greek civilization is a woman being raped” (Kowaleski-Wallace 2009, p. 476). |

| 4 | See Introduction to Ethical Literary Criticism (Nie 2014, pp. 34–39), the essence of ethical choice of human beings is “to be men or to be animals.” Since men evolved from animals, everybody is a combination of Sphinx factor—human factor and animal factor. The animal factor is driven by the original desire; and human factor, which can control animal factor, helps to get ethical consciousness and human nature, thus human beings can distinguish good from evil and become men from animals. What we call the original sin of Adam and Eve eating the forbidden fruit in the Bible is actually the animal factor that still exists in the human body after human beings liberate themselves from animals through ethical choices. |

| 5 | The sexuality of the swan and Leda, or the sexual relationship between the gods and human beings, is considered as “an extension of the parent-child relationship”, which is “consequently incestuous” (Medlicott 1970, p. 15). Helen’s elopement and abduction with Paris and Clytemnestra’s murder of her husband with her lover all represent their ethical choices, which indeed break the religious order and violate the ethical taboo, thus leading to the destructive Trojan War. |

| 6 | This is about “the riddle of the Sphinx”, and the image of half-man and half-animal in Greek mythology actually is the artistic portrayal of human’s evolution from the ape as well as the original image of human being after natural selection (Nie 2011, p. 5). In the process of human evolution, when human beings obtained human shape through natural selection, they also found that they still retained many animal characteristics, such as the instinct of survival and reproduction. The Sphinx realized that she was different from an animal because of her human head, but the original desire embodied in her lion body and snake tail made her feel herself like an animal. She longed to know whether she was a human or an animal, so she expressed her confusion to people by asking questions. Finally, she got the answer “human” and jumped off a cliff in shame and died (Nie 2014, p. 37). |

| 7 | In the Homeric epics, the Trojan War starts with the “Golden Apple of Discord”, a debate of “who is the fairest or most beautiful woman” among the goddesses Hera, Athena, and Aphrodit, and then continues as the fight for the most beautiful woman in the world, Helen. |

| 8 | See Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design (Kress and Van Leeuwen 2006). The representational meaning is divided into narrative and conceptual (p. 59) to describe the story; the interactive meaning has four important factors: contact, social distance, attitude and modality (p. 149) to highlight the relationship; while the compositional meaning emphasizes the information value, salience and framing (p. 177) to present the focal point. This paper will take these into analysis when reading the images, especially the paintings of Leda and the Swan so as to look back at their religious projection and ethical appeal. |