1. Introduction

Southern African San forager worldviews exhibit topo-ontological domains characterised by persons who are human and persons who are not. There are places that are the realms of certain persons and their concordant ways-of-being, the inhabitants characteristic of the place, and vice versa. Human persons are those who occupy the human range of territory and behaviour, while non-human persons are those who occupy theirs respectively; an animal is what it is for being in certain habitats and expressing the behaviours of things you might expect to meet in such a place. Throughout, however, they remain persons irrespective of their habitats or behaviours, and as

Viveiros de Castro (

1998, p. 470) observes, this requires a break from the Western “implication of the unity of nature and the plurality of culture” (cf.

Willerslev 2007, p. 183).

This is because persons are the reproductive unit of culture: where there are persons, be it in nature or in ‘civilisation’, among communities of human persons or those of animal persons, there is culture, dissolving any potential binary separation between natural and cultural worlds (cf.

Descola 2013). This has interpretive implications for the world behind San rock art in southern Africa—as has been observed in other ethnological settings, the forager world is oft ‘multinatural’ in this sense, and San idioms are no different. The topographies of this ethnographic domain are both evidently practical but also vitally social (

Riley 2007;

Skinner 2017, pp. 101–5, forthcoming;

Guenther 2020b, pp. 71–79). Navigation of such a world is accordingly an exercise in negotiation—not of static boundaries, but in those moments an individual might find themselves in a boundary state, strung tenuously between the norms and expectations of the communities around them, the variant ways-of-being those communities express, and the places one encounters both these beings and ways.

The centrality of this idiom to foragers’ lives has recently come to the fore, at least in anthropological terms (

Guenther 2015). Archaeologists have been slow on the uptake, however, owing to the dominance of certain established interpretations of material culture, of which the shamanistic approach (e.g.,

Lewis-Williams 1980,

1992,

1998; inter alia) is the most well-known. The significant internal integrity of the approach is both reason for its longevity and part of why it may struggle to adapt to expanding ethnographic datasets (discussion in

Skinner 2021b; although see

McGranaghan and Challis 2016), and why the anthropological emphasis has taken so long to shift in southern Africa, a region known for its autochthonous shamanistic beliefs (discussion in

Guenther 2015).

Here we examine rock art, the material–cultural artefact whose study arguably made southern African archaeology, in light of recent developments in New Animist approaches. We illustrate the characteristics of relational ontology that anthropologists might recognise in San idioms. Using the lens of navigation, this process of movement across social topographies, we foreground the ontological consequences of place, position, and perspective. Most of all, we look to the social universe in which this painted imagery resides, and to the practices which have been so central in negotiating life within it, with the art being both a record of prior interaction between communities and outcome of mediations-in-progress, this animist shamanism (re)producing its norms in the art.

To this end, we first outline how shamanism in southern Africa has been seen, and how it is seen today by outsiders (scholars), as well as how it is seen by insiders (foragers) in the ethnographic present of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. From there, we develop an account of forager navigation-as-negotiation, and the ways in which certain San idioms resolve the consequences of presence on a social landscape, amidst its human and non-human cultures, through a process of constant brokering of relations between agencies. Finally, we present examples of rock art we argue was produced as part of this process of brokerage, the images produced to maintain ‘proper’ relations between the communities of these landscapes.

2. An Animist Shamanism

The cast of southern African forager arts as shamanistic is well-established (

Lewis-Williams 1972,

1980,

1998;

Dowson 1989; cf.

Vinnicombe 1976). The shamanistic framework notably rejected the account of the art as literal representations of ‘scenes of everyday life’ that had flourished in the early- to mid-twentieth century (e.g.,

Burkitt 1928;

Breuil 1948;

Willcox 1956; discussion in

Lewis-Williams and Pearce 2009, p. 49), and took issue with the common misconception that the art offered a glimpse into the pristine lives of a primordial human population (see

Gordon 1992, pp. 194–95). Perhaps ironically, the religious orientation marked a return to an earlier position, held a century earlier by George Stow and Joseph Orpen, that the images had a “mythological meaning” at the very least, and likely encompassed “certain quasi-religious rites” (

Orpen 1874, p. 1; cf.

McGranaghan et al. 2013, p. 151) and which Wilhelm Bleek (in

Orpen 1874, p. 13) thought was rather self-evidently “a truly artistic conception of the ideas which most deeply moved the Bushman mind, and filled it with religious feelings.”.

As it developed, the shamanistic, hermeneutic approach (following

Blundell 2004) envisioned the imagery as part representation of (

Lewis-Williams and Dowson 1988), part reference to (

Lewis-Williams 1998) the ritual experiences of shamans (see a recent summary of this position in

Lewis-Williams et al. 2021, p. 44; wider theoretical contexts in

Whitley 2014;

Whitley et al. 2020; wider applications in

Wallis 2002;

Rozwadowski 2014; deep-time application in the European Upper Palaeolithic in

Clottes and Lewis-Williams 1996;

Lewis-Williams 2002). In particular, it centred the altered states of consciousness achieved through ritual dance. The dances in turn permitted the shamans of various southern African forager societies to traverse a visionary, spiritual world, deploying animal potencies under their control, and using this power to make intercessions in the lives of their communities (

Lewis-Williams and Pearce 2004, p. 206) such as controlling the movements of game and weather, and healing disease and other social ills.

The hermeneutic model is not uncontested (e.g.,

Bahn 1988;

Solomon 2000;

Helvenston and Bahn 2003;

Hodgson 2006), though its neuropsychological implications are among its strongest facets (discussion in

Froese et al. 2014;

Froese et al. 2016) and there is good reason to continue self-aware implementation of its general principles (see discussion in

Wallis 2002). In this critical spirit, we are obliged to consider the representations the approach makes of both the ethnographic source domain—Qing in the Maloti-Drakensberg (

Orpen 1874); the Xam in the Karoo (e.g.,

Bleek and Lloyd 1911;

Hollmann 2004) and the many extant groups of the Kalahari (e.g.,

Marshall 1976;

Katz 1982;

Guenther 1999)—and the art to which it is applied in interpretation. In particular, the ways in which it models the world around the images. We are interested in the elements of other approaches that such an outlook might reject for their proximity to problematic positions—that it might, for instance, reject a ‘narrative’ or ‘representational’ implication on account of its resemblance to these earlier positions, rather than as a factor of their applicability or ethnographic support (see discussion on ‘reconfiguring hunting magic’ below, and in the New Animisms;

McGranaghan and Challis 2016).

Indeed, owing to the heuristic device that descends in tandem from the rejection of ‘empirical’ (viz. that they are quotidien visual-representative) perspectives of the images, and that of ritual dance = altered states = paintings, there has evolved a representation that altered states, and the ‘passage’ they provide between worlds, is evidence for a tiered and divided cosmos in the belief systems of the informants, reminiscent of

Eliade’s (

1972) axis mundi (see topical discussion in

Lewis-Williams 2004, pp. 29–30). In this, there is a realm in which spirit people and animals exist, inaccessible except through trance, separating the everyday from the extraordinary (e.g.,

Lewis-Williams and Dowson 1990) in a broadly equivalent form to those registers compartmentalised as either ‘real’ or ‘religious’ iconography in rock art. Correspondingly, the people who traverse in this way have their practises rendered distinct from domains of practicality (pace

Lewis-Williams and Challis 2011, pp. 192–99), enacting their craft in domains of sacredness discrete from those profane.

This presents a universe delineated into a Cartesian ‘nature-and-culture’, with nature being a realm of resources/bodies, and culture that of persons/minds, both governed by an ‘ontology of control’ (after

King and McGranaghan 2020) in which animals are controlled and their powers deployed for human endeavours, subordinated to those categories of human (visionary) experience which are central to interpretation. As Mathias

Guenther (

2020a, p. viii) has recently pointed out, this resembles the positivist

Man the Hunter (after

Lee and DeVore 1968) works of Kalahari anthropologists of the 1960s and 1970s, which has led southern African anthropology and archaeology down the materialist ‘optimal foraging’ route for decades. Even religion, it seems (see

Guenther 2020a, p. 2), has come to be analysed for its optimising characteristics (e.g.,

Lewis-Williams and Pearce 2004), one among a suite of tools and adaptations with practical outcomes in a human-centred world.

This paradigm has led researchers of San religion to focus symbolically and phenomenologically on how the shaman-dancer intensifies his human self through a neuropsychological experience of an Altered State of Consciousness, rather than being transported out of this self and into another, non-human being and subject, through a phenomenological experience of transformation (

Guenther 2020a, p. 2).

Following

Guenther (

2015,

2017,

2020a,

2020b),

McGranaghan (

2014a,

2014b), and our own related works (

McGranaghan and Challis 2016;

Skinner 2017;

Challis 2019;

Skinner 2021a,

2021b), we discern how the rock art reflects the artists’ interactions with ‘non-human’, or perhaps more accurately ‘other-than-human’ (after

Hallowell 1964, p. 36) entities, with whom their communities sought to broker relations.

The nature of the intercessions that shamans enact, and how these are negotiated, are factors by no means ignored in the hermeneutic approach, but they remain far from fully explored. Thus, we see good reason to pursue a New Animist analysis for its de-centring of human experience, its implications for a world characterised by the relationships between communities living within it, and analytical outcomes that expand our frame of reference beyond the inherently ritual elements of shamanistic practice. Elements of rock art that do not explicitly feature the dance have previously been explored in terms of sympathetic ‘hunting magic’ (

McGranaghan and Challis 2016) and the effects of excessive potency in certain landscapes (

Challis 2019) as expressed in the idiom of both the Karoo |Xam (

Skinner 2017) and the southern Maloti San (although cf.

Skinner 2021a,

2021b). In this contribution, we present an account of the ways the art ‘populates’ the landscape, affecting the relationships between communities by providing a material record and cultural reference point for interactions between them, drawing on the past to navigate their present, sometimes tenuous, social conditions (e.g.,

Skinner 2017). There is a spatial dimension to these occurrences; to hunt, for example, is to traverse boundaries between communities and ways-of-being in numerous respects, often incorporating dangerous transgressions of place, personal identity, and bodily integrity, the consequences of which are a central subject of inter-species negotiation. We look to the ethnographies of southern African shamanistic societies past and present, and consider the ways in which their contributors relate(d) to their worlds and how those relations structure(d) their experiences and intentions.

4. The Problem of Personal Property

A slow-burning axiom that has come to bear is the orthogenesis of hierarchies in erstwhile egalitarian societies; owing to cross-cultural contact with farmers and settlers, the changes wrought in forager societies endowed them with new approaches to personal accumulation. This has been extended to religious forms, through the suggestion that certain powerful shamans had unique accumulations of power, permitting them to rise to prominence, and creating a spiritual inequality of sorts. It is further argued that this is discernible in the art of the Maloti-Drakensberg (

Campbell 1987;

Dowson 1994,

1998;

Blundell 2004).

This position stems from (

Guenther’s 1975)

The Trance Dancer as an Agent of Social Change, in which he observed modern ‘Farm Bushmen’ achieving renown for his ritual abilities. To support this, some paintings have been presented as exhibiting the progression from egalitarian group, through consortia of powerful individuals, to singular pre-eminent shamans who were able to dominate their social groups (

Dowson 1994). Unfortunately, the model is simply not demonstrable, either as a response to contact or otherwise, since no dated paintings have been produced to support a chronological sequence that proceeds from (early) egalitarianism to (late) social stratification (cf.

Mitchell 2002, p. 407;

Smith 2010, pp. 348–49;

Mullen 2018;

Challis forthcoming).

In a resource-focussed discussion of the dance, ‘supernatural potency’ permits access to the ‘spirit realm’, harnessed from the essence of the animals being sung/summoned at the dances (

Lewis-Williams et al. 2021, p. 44). In this account, particular shamans might be able to accumulate this power in support of personal status. There is a question, then, about whether there can be an accumulation of the capacities of persons beyond themselves as resources—the energy comes from animals, yet if animals are persons, how are they to be accumulated? In this line of reasoning, they are in fact accumulated, conceptualised as ‘reservoirs’ of power (ibid.). Yet, as comes to light increasingly, relations are in fact maintained with individual non-human persons through shared understanding, the functions of consent, reciprocal obligation, and normative alignment (see ‘care’ in

McGranaghan 2015, pp. 537–38; ‘nice treatment’ in

McGranaghan and Challis 2016;

Guenther 2020c). Some of the language of a domesticated frame of reference applies (discussion in

McGranaghan 2015;

King and McGranaghan 2020), though where we find descriptions of a hunter ‘possessing’ an animal species, for example, this is not in the sense of ‘property’ but rather that of ‘influence’ (

Challis 2005, p. 18). It is through salient demonstrations of understanding between persons that ‘ownership’, in this idiom, is achieved (

McGranaghan and Challis 2016, pp. 583, 591).

It appears that shamans do this equivalently (

Challis 2005, pp. 12–14; see below). When they draw upon animal energies, they are appealing to specific agencies personally (

McGranaghan and Challis 2016, pp. 592–94), and responding to the ways such an agency would present itself and draw upon them in turn (see

Hoffmeyer 2008, pp. 15–16;

2010, p. 37;

McGranaghan 2012, p. 338; cf.

Viveiros de Castro 1998, pp. 470–71). This is particularly true if it occurs in ways that suggest the animals are ‘significant’ individuals (viz. those amenable to approach, or able to act on behalf of their community; discussion in

Skinner 2017, p. 185). The implication that animal capacities could be stockpiled robs them of personhood, rendering the non-human inhabitants of the landscape so much like those of a Westerner’s nature, replete with material to be harvested, as opposed to the “theatre” (after

Riley 2007), whose occurrences are characterised by the desires and intents of many forms of agency. Correspondingly, this historical-materialist emphasis characterises the world, and navigation of the world, in terms markedly reminiscent of a Western frame of reference (cf.

Challis forthcoming).

Is a landscape under control or domination one possessed of persons beyond the human frame? We would say not. However, in the ethnographic sources, we recognise a general contiguity between the ways humans assess the behaviours of other human communities, and those of other-than-humans. Notions of ‘sympathetic control’ (

McGranaghan and Challis 2016, p. 580) such as

!nanna-se, are one example. Their translation is as ‘respect’ practices (e.g.,

Hollmann 2004, pp. 66–75), less as the hard formulation of control, and rather something more like concentrated influence. This, in turn, we find representative of a world determined at the confluences of multiple agent-perspectives, its norms determined by the interrelations of those agents’ knowledge, attention, and forms of attachment (following

Descola 2012a).

In our ethnographic sources, we observe the extension of personhood between communities, and across species’ definitions, through the equivalent ways informants assessed the behaviours of (human) family, and those of hunted animals: animals treated as persons. While

!nanna-se “dealt primarily with non-human contacts” (

McGranaghan 2012, pp. 193–94), it bears close structural and practical resemblance to the

!k”werri:tǝn complex (v. to show respect, to be ashamed;

Bleek 1956, p. 510), tied into manners of address between kin, avoidances of conflict, and recognition of seniority within extended families (fathers/mothers in law; see

McGranaghan 2012, pp. 193–94).

!nanna-se enjoined hunters to meet their commitments to their prey, and from “dealing immodestly” with their kills (

McGranaghan and Challis 2016, p. 587), thus inviting ontological retributions for their inappropriate actions, or problematic entanglements of their identities with those of their prey (e.g.,

McGranaghan 2012, p. 140).

In similar terms, just as humans would shame noncompliant extended family members, and through shame mitigate problematic social consequences, it functioned in equivalent ways when applied to other-than-humans, with surprisingly little variation across species. Kicking a proud lion between the legs would shame it (LL.V.8.4593′) and neutralise it as a threat; telling a baboon that arrows or hunting dogs belonged to a girl would cause it to relent to a hunt (LL.V.20.5920–5922; LL.V.24.5953–5956). This extends further, applying to the likes of the rain, even, another force of the world capable of being shamed (see

McGranaghan 2012, p. 190); inasmuch as the failings of a family member would bring recrimination from their affines, the rain could be shamed, connected as it was to human communities by formalised obligation.

As humans in one’s own community could expect repercussions from social faux pas, failure to meet the reciprocal requirements placed upon them by another party’s observances would bring failure upon any inter-community engagement. Thus, in the way a hunter could expect failure from an inability to meet the requirements of prey, even prey animals could expect a range of problematic outcomes from non-compliances of their own, even if their obligations were to the humans predating upon them (

McGranaghan 2012; cf.

Willerslev 2007).

We can infer social continuity between human and non-human settings based on this principle. Shame is a function of taboo-recognition; one cannot shame something that does not present or experience social injunction, or that does not recognise the principle of reciprocity. Culture is the necessary milieu to these occurrences; it orders these injunctions and principles, and aligns and defines frames of reference. If one crossed into passive nature at the boundaries of human communities, there would be no reason for social frameworks to extend further into the world than those enacted by humans themselves. There is no nature/culture boundary as implied by materialist analysis that frames the world as resources outside, and persons inside, because culture is what orders social interactions between persons human and non-human and structures the world in terms of its social relationships.

Indeed, this “is why some specialists … prefer to use the term “procurement” rather than “production”, the better to underline that what we call hunting and gathering are primarily specialised forms of interaction that develop in an environment peopled with intentional entities that are comparable to humans” (

Descola 2012a, p. 458).

In this way, social skill is the requirement for any kind of traversal of space, as much as it is for dwelling in it. The logics of the home range (the places and behaviours with which a community is familiar) are reproduced at moments of understanding of the home-logics of social others, as they are encountered at various points of transit across a landscape. In so doing, they position themselves at various points on the social indices that species maintain of the other communities of the landscape with which they do or do not relate. Reproduction of specific behavioural tropes on demand is insufficient, however; skilful “understanding [of required social norms] was developed not only from having heard the requisite information, but by ‘agreement’ with it” (

McGranaghan 2012, pp. 180–81). Internalising social education, replicating cultural forms, and interpreting those presented by the world (e.g., LL.V.12.4937–4938) are essential to enacting safe passage, as it permits one to meet their obligations to those with whom they make contact, and preserving their agreeable forms with others. At once, those erstwhile others reciprocally offer their own understandings (e.g., LL.V.20.5544–5545).

Internalise and replicate these norms, and the world will act with you, and your navigation will proceed as planned. Fail, and it will judge your passage as transgression, and punish you for your failures to set up appropriate relationships, presenting a world that is capricious and full of dangerous intent.

Social norms are demonstrated and reinforced by the appropriate and inappropriate behaviours of personages in myth, persons enacting the everyday, persons in trance, and by animal-persons navigating their own social universes. Antisocial figures in myth were both risible and terrifying, and presented sometimes as models, though often as contrasts for personal behaviour. For the nineteenth-century |Xam, lions of the Early-Race were inappropriate with their food, killing indiscriminately, never sharing their meat and consuming immodestly and rapidly (WB.XIV.1367–1368; LL.II.1.256′–1258′ in

McGranaghan 2014a, p. 11), hardly different from ‘real’ lions observed today in the Kalahari, and to whom the Ju|’hoansi attribute a personhood that is powerful and malevolent. It is possible for people to change into lions during the dance, whether by accident or by design, and this transformation may carry all or any of the associations here mentioned, cumulatively the characteristics of social monsters. Monsters, in turn, are both the characteristic of, and characterised by their residence in, the dangerous and distant (viz. socially unintelligible) reaches of the world (discussed in more detail below). In rock art, such connotations can convey many meanings but, as we shall see, “all of this operates within a ‘connective cosmology’ underwritten by myth and belief” (

Guenther 2020a, p. 27), in which what one is is determined primarily by who they are to others, their ‘species’ such as it is, determined by their alignment with the norms of one or other community of persons. Accordingly, this landscape is one in “which human and animal identities are merged, thereby dissolving species boundaries and, more generally, Cartesian dichotomies. And underwritten by experience, whenever a shaman or initiand, painter or storyteller or hunter becomes him/herself an animal” (

Guenther 2020b, p. 27).

All of this points to a strongly reciprocal modelling of communities by one another. As the social/cultural units of topography that one may encounter, navigation by these communities leaves them all in a constant state of mutual definition, in accordance with their various states of normative conformance. Those communities, in turn, are predominantly determined by disposition, assessed equivalently between humans and non-humans. Where ‘Grass’, ‘Mountain’, and ‘Flat Bushmen’ were among the range of human iterations, they were evaluated by the ways their defining technological and behavioural traits would make them more or less compliant with social expectation (see discussion in

McGranaghan 2012, pp. 219–22).

In places furthest from familiar frames of reference can be found the communities least compliant and most hostile (see

Skinner 2017, pp. 156–57,

2021a), such as the archetype of the Korana (an historic raider combine of the northern cape frontier;

Engelbrecht 1936). The Korana were characterised by their possession of suites of violent material culture and correspondingly dangerous dispositions, though they still possessed sufficiently coherent ideologies to demonstrate their ‘difference’ from the |Xam in terms that the latter understood (

McGranaghan 2014b, p. 679). Colonists were similarly rendered in violent stereotype, likened to hyenas (another stereotypically antisocial creature), described as inclined to attack at night, and having “hair like lions” (

Raper and Boucher 1988, p. 194) in reference to their stereotypically blonde locks and beardedness (

McGranaghan 2012, p. 205;

2014b, p. 681).

It is notable that these physical characteristics were both cause and effect of their inclinations. This is demonstrated in the ways that social ‘difference’ (viz. strangeness, normative noncompliance; see |xarra; D.

Bleek 1956, p. 363) manifests physically. This may be in foul odours (see LL.II.14.1442), hairiness (LL.II.2.333; LL.II.30.2693–2694; LL.V.3.4127–4128;

McGranaghan 2014b, p. 674), and yellowness (|kai:nja; ‘yellow, green, or shining’; D.

Bleek 1956, p. 297; LL.II.18.165;

McGranaghan 2014b, p. 674), which are all characteristics of a ‘beast of prey’. When, in myth, the primordial Caracal became embroiled in the identity of a hyena (i.e., began to reproduce its mores), it assumed the latter’s beastly mantle, and manifested yellowness and hairiness in the process (LL.II.18.1654–1657), taking on the definitional features of dangerous or antisocial things to accord with its behaviour. Form, in this way, accords with content, yet the two are each as mutable as the other. A shape is taken on account of tendency, intent, and the (in)ability to answer social obligations. This means that a judgement of species is, in effect, an assessment of what cultural characteristics an agent deploys at a given moment, and how those characteristics interface with their social surroundings.

This imparts a significant reliance on how one agent is perceived by others, as compliance and influence will render one more or less sociable, and thus, more or less alike in form and tendency. The landscape thus ordered is in shades of relative similarity, its proximities more enmeshed in one another, and more similar, its distal regions more different, replete with dangerous strangers, less inclined to operate in sociable terms. The general mirroring of ‘in-community’ social assessments over the landscape suggests that an assessment of ‘non-human’ largely mirrors the assessment of ‘non-|Xam’, for instance, suggesting they should be considered more or less equivalently, with relatively little impact on the ontological personhood they imply. A distant person (human or otherwise) is a bad and strange person, and all of those things in turn, but they remain a person nonetheless. Culture extends across them almost by necessity, as it is a determining feature of either classification; intelligibility is both the cause and effect of normative (mis)alignment.

It follows that discrete natural/cultural delineations are incompatible with a system in which “ways-of-being (or doing)” (

McGranaghan 2014b, p. 683) are so inherently connected to perceptions others make of one’s identity. An animal is itself by the expressions of specific animal culture, read as such by another. For socially skilful humans, these expressions can be understood if one has a “way into” (

McGranaghan 2014b, p. 683) the animal; that is, knowledge of its culture, and ability to recognise its behavioural signalling. Similarly, one is something other-than-animal by expressions of the forms of human culture, and reproduction of those defining human norms where others can recognise it. The differing extents of both human and animal are determined at moments of their mutual observation, constrained by their relative knowledge of one another and their respective abilities to understand. In this way, each is defined by the behaviours they manifest in moments of contact with the other, their social obligations met or missed as a factor of knowledge or ignorance.

Indeed, a human is |Xam, for instance, for all the reasons a hyena is a hyena, and a baboon a baboon. None of these are immutable categories, and no one of their communities have a unique claim on culture, nor surplus or paucity of internal social life. A good example of this is the baboon, a population given much attention by the |Xam as a (topographically and ontologically) neighbouring community. Baboons are accorded an explicit self-awareness and fear of death (LL.V.24-5957–5964); further, they have language (LL.V.24.5926; see

Bleek 1931, p. 167;

Hollmann 2004, pp. 10–11), practise marriage (LL.V.24.5924′), and utilise characteristic medicines (LL.V.24.5924′–5925′; cf.

Challis 2009, pp. 104–7;

2012, p. 276;

2014, pp. 259–60). These relative proximities to human communities place them on the border of the human definition, though partly ‘outside’ it as well, as a factor of their known violent tendencies.

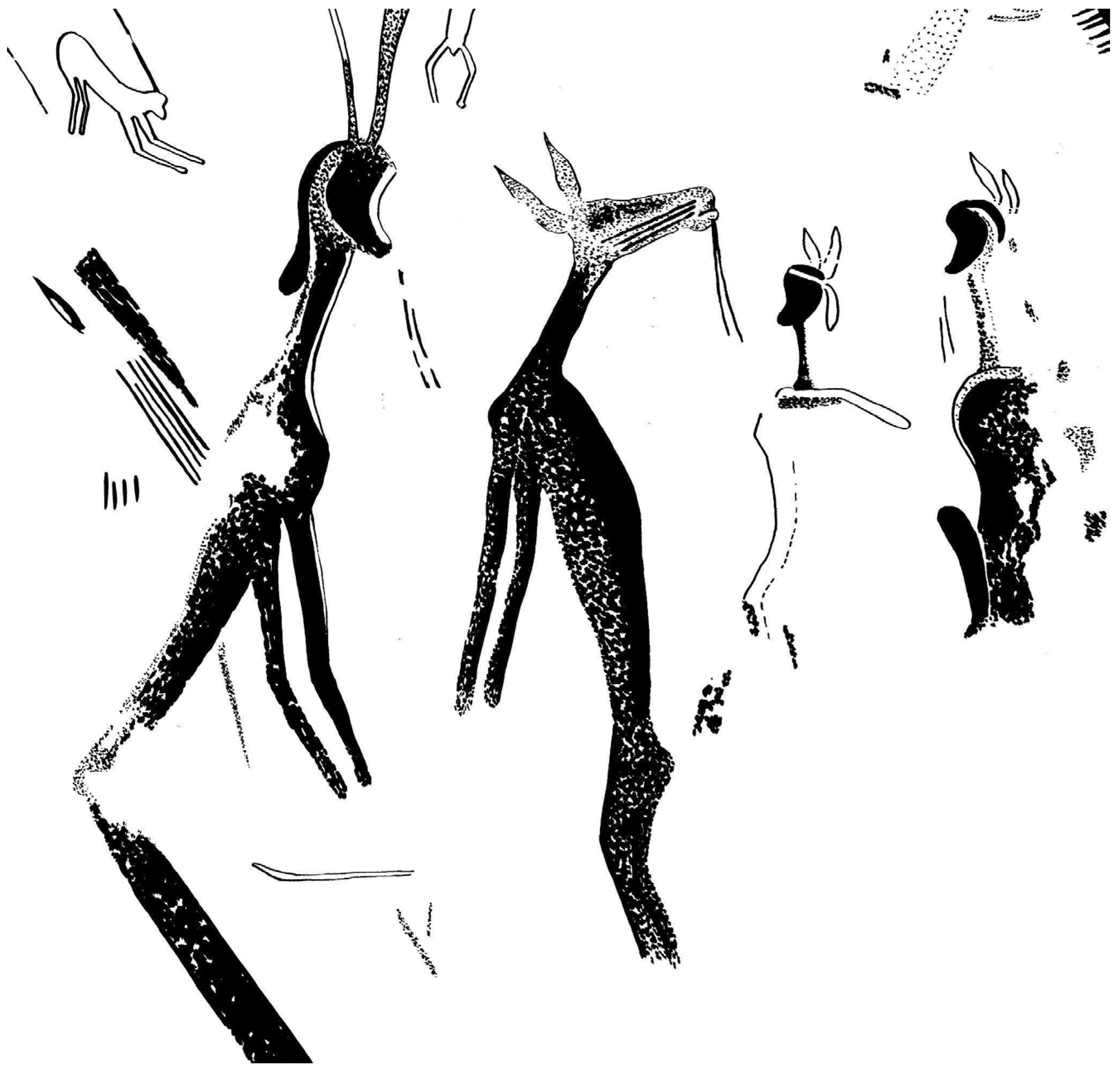

Of interest is that historic human communities have employed these logics to themselves. An example is the AmaTola, an ethnically composite community in the nineteenth century Maloti-Drakensberg who incorporated parts of Maloti San culture. They utilised the medicines that defined baboons and were known to herder and farmer societies as raiders, pillagers, and inhabitants of socially marginal conditions. Their arts acknowledged their humanity alongside a boundary condition determined by their violent ways of life, taking on baboon-ness (see

Challis 2014; e.g.,

Figure 1) in a way that reflected their status on the edges of other human communities (

McGranaghan and Challis 2016). They were humans whose social status, ontological status, and defining range of territory and behaviour overlapped the definitions of baboon communities. Thus, their relative intelligibility (mis)aligned with both other humans, and other baboons to varying extents, at any given moment changing both who and what they were. They used baboon potency, which at the same time held the essence of its qualities, to cheat death as the baboon does, and they signalled this in their rituals, paintings, and practices (

Challis 2014).

In this way, both presence and navigation of the landscape are acts contingent on the maintenance of relations. ‘Closeness’ with or to a given community, their behaviours, or their territories is what determines both the form and character of interactions with others, because one’s relative similarity or difference to others will practically determine what one is (cf.

Viveiros de Castro 1998). Correspondingly, humans do not extend unique agency into a passive world, nor represent isolated expressions of culture on an asocial plane, but are simply human nodes of relation in a socially relativistic universe. As relations in this space have causal impact on identity, so does the ability to understand others determine how dangerous a place is; failures to understand produce dangerous interactions, and populate the world with dangerous agencies, while knowledgeable means of approach reproduce favourable results. Thus, to traverse the landscape is to appeal not only to human perspectives, but to the animal ones that determine the character of a given experience in the world. Our sources recognised that they could not just go into the world and take, but that everything is transformative, contingent, momentary, and responsive, and all in need of negotiation, or brokerage, as we would have it.

5. The Social Basis, and Equivalence, of Practice

The world’s encultured character means that interactions between persons, human or otherwise, must be negotiated as normative performance. In ethnography, we observe this in the way that assessments of social efficacy apply to nearly all activities. This is the basis of the general “contiguity between ritual and mundane activity” (

McGranaghan 2012, p. 203) that accords with observations made by commentators on |Xam ethnography (

Hewitt [1986] 2008, p. 185;

Guenther 1999, p. 104;

Riley 2007, pp. 292–93;

Dowson 2009, p. 380;

McGranaghan 2012, pp. 202–3, 338;

McGranaghan and Challis 2016, p. 591; cf.

Lewis-Williams 1992, p. 57), and in discussions of the material collected in the Kalahari (

Katz 1982, p. 52;

Biesele 1993, pp. 21, 23;

Guenther 1999, p. 236; see also

Silberbauer 1981, p. 130). Realising desirable outcomes in any practice could be broadly described as ‘skill’. As social nous governs how favourably one’s endeavours will be, skilful behaviour of any kind is accordingly a display of social ability overall.

We can infer a social character, and thus imply a social environment to even what might otherwise be considered ‘spiritual’ activities. We extend these social conditions on the basis of the very clear equivalence in the assessments as social activities, irrespective of their apparently ‘spiritual’ or ‘mundane’ settings. Magical occurrences, and the application of magic (‘sorcery’; e.g., LL.V.20.5544–5545), has common, essential and overlapping restrictions of social logic that apply elsewhere. The central determiner of success is as that above; the salient demonstration of “proper relations between species [viz. persons]” (

Hewitt [1986] 2008, pp. 92–95; see

McGranaghan 2012, p. 148;

2014a, pp. 14–15;

2014b, pp. 678, 680–81) determined an action’s prospects of success, spiritual or not. This is a principle condensed as

ǁkwakka, the notion of behaving with ‘understanding’ (

Bleek 1956, p. 596;

McGranaghan 2012, pp. 169–70), as the social conditions of the world variably oblige.

Actions demonstrating this form of understanding were done ‘nicely’ (see

twai:ĩ;

Bleek 1956, p. 243), and thus met with favourable outcomes. The judgement of ‘niceness’ here broadly accords with what one might think of as ‘nice’ behaviour. For example, when making arrows,

Stones used to straighten the reeds imparted a ‘smoothness’ that allowed the arrows to fly ‘nicely’ (LL.VIII.14.7235), implying that within a technical trueness of trajectory lay a kind of socially objectified agreeableness; smooth arrows behaved themselves.

This follows the reciprocal cycles that both determine and cause intent and form. The ‘ugliness’ of iron-tipped arrows (LL.VIII.1.6086) contrasts the state of ‘looking well’ (

a:kǝn;

Bleek 1956, p. 7;

McGranaghan 2012, pp. 40, 139–40, 169–71;

McGranaghan and Challis 2016), that would have been achieved by the artful use of a more socially apt material. Materials are judged in the same capacities as species in this sense, aligning (or failing to align) socially in correspondence with their tendencies, and the ways in which others relate to and with them.

In this way, the perhaps most overtly ‘practical’ elements of the world are governed by essential social logics. The making of arrows to be used in hunting is not “a virtuoso fashioning of a raw material, but rather as an incomplete actualization, in slightly different forms” (

Descola 2012a, p. 460) of the elements of living things evoked as “transformed bodies” (

van Velthem 2001, p. 206), rendered into material objects. By virtue of their animated origins, they required as much social consideration as something more obviously sociable.

Within this framework, both hunting and trance are designated as domains of skilled (as above) behaviour, amenable to assessments of their relative ‘niceness’, or the ‘understanding’ they represented, both indicators of desirable states of (social) artfulness (e.g., LL.II.11.1111; LL.II.13.1308;

McGranaghan and Challis 2016, p. 588). Indeed, ‘magic’ could be seen as merely the communication of a particular social capacity that agents have (e.g.,

McGranaghan and Challis 2016, p. 594), which follows the same rules as everything else. This is demonstrated by the general equivalence between arrows and hunting; antelope could ‘fire back’, using ‘magic arrows’ that would cause illness (LL.VIII.15.7263′), to punish improper approach.

This, too, is the background to the ‘owning’ of animals. A hunter might ‘possess’ an animal through a salient demonstration of understanding that animal; often, in their capacity to enmesh themselves in the lives of that animal, recognise their obligations, and deploy the correct social cues (

McGranaghan and Challis 2016, p. 591). Shamans did so in similar terms when they engaged animal agencies (e.g.,

Challis 2005, pp. 12–14), rendering them ‘tame’ (

McGranaghan and Challis 2016, pp. 592, 594) through similar appeals to obligation.

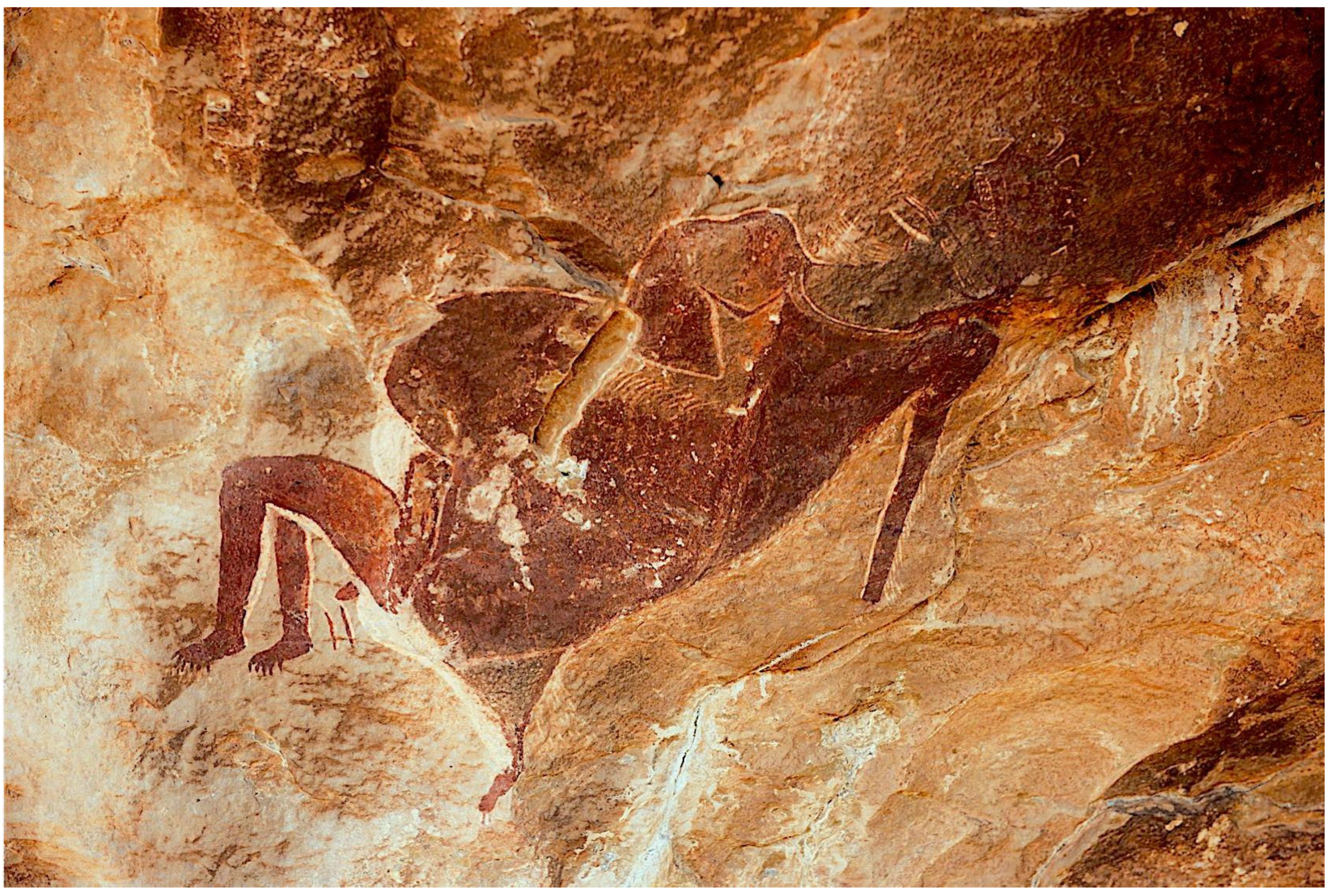

To have the understanding of an animal was to be particularly adept at dealing with it, to observe all social protocols and rituals; carrying the correct accoutrements, smelling the correct way, and using respect terms or, as ||kabbo put it to Lucy Lloyd in 1872, “we must approach nicely. Our killing the springbok … [we] approach with understanding” (LL.II.10.1111). Springbok hunting specialists among the nineteenth-century |Xam had special insignia; Springbok-eared caps were real items of material culture made from the animal’s scalp. In Maloti-Drakensberg paintings, such caps are commonplace, although importantly they are often found alongside and in a spectrum of equivalence with therianthropes; that is, human–animal composites, in which shamans partially transform into antelope (

McGranaghan and Challis 2016; see

Figure 2 below). Both the caps and the antelope transformations are overwhelmingly rhebok (as Qing made plain to Joseph Orpen in 1873,

McGranaghan et al. 2013). The eared caps denote the specialist’s inclination towards that antelope, the transformation shows the inclination the specialist has to take on the form, and thus the qualities of that antelope:

For sorcerors have things whose bodies they are. These things which they have seem to see. When these things seem to have seen something which the sorceror does not know the sorceror feels in his senses that something is happening (Dia!kwain to Lloyd, LL.V.25.6011–6013).

In this passage, Dia!kwain emphasises part of the purpose of the relationship insofar as the animal (whose body the specialist has) helps the specialist to become attuned to its perspective. In the Kalahari, the healer Kxau Giraffe told Megan

Biesele (

1993, p. 70) that his animal, the giraffe, facilitates travel when in trance: “Just yesterday, friend, the giraffe came and took me again”.

Conversely, just as hunters transferred destructive energies through arrow-media in the hunt, so too did particular kinds of shaman (as well as other anti-social agencies) cause sickness and death through ‘arrows’ of their own (

McGranaghan 2012, p. 204). The word for “shoot with magic arrows”,

|xãu (

Bleek 1956, p. 363), is particular to such transfers enacted by shamans, but descriptions of the action of shooting occur extensively as metaphors for the transfer of energy in practically all settings, nearly exclusively through arrow-like media. These transfers, in turn, are of a great stature in the idiom, as they represent a transgression of boundaries; the influence that one agent may perhaps forcibly, often problematically, place upon the body of another.

The topological element implied by such transgressions is apt. Both hunters and shamans traverse the semantic, symbolic, and topological demarcations of species, their skilfulness determined by their abilities to read the turn of the social landscape, and navigate it appropriately. Because of the relationship between form and intent—inasmuch as predatory, ‘monstrous’ behaviour makes one a monstrous predator (

McGranaghan 2012, p. 413;

2014a)—this would likely involve changing form, as they aligned themselves with the norms of another community or invoked the behaviours of social others. As they would probably be enacting energy transfer across species/community demarcations as well, the likelihood of success and mitigation of problematic (monstrous, predatory) consequences would be determined by how socially adroit they were able to be in the process.

The traversals and transfers made by both hunting and ritual disciplines encounter the same prominent tension. Approach to other communities is a normal part of life, both as one merely traverses physical or metaphorical domains, and as one engages in the transfers of energy and substances that drive shamanic, forager life. Yet, such an approach requires a simultaneous mimesis and distinction (cf.

Willerslev 2007, p. 191). ‘Nice’ approach is that which permits one to realise their intended outcomes and requires the reproduction of norm and form. Where one begins within a human frame of reference, one does the things that humans do to contrast oneself to others (cf.

Descola 2012b); to traverse the boundaries between communities and achieve the uptake of useful energies (meat/calories, fat/power), one must as both shaman and hunter temporarily invert their defining contrasts, and come as close as possible to their ontological target.

That there is bleed-over is inevitable, and this is reflected in ritual observances that impart these norms to adolescents in rites of passage. In a review of examples in which Kalahari foragers equate themselves with animals, Mathias

Guenther (

2015, p. 292) highlights the girl’s initiation ceremony in which she is named both hunter and eland—the mimesis and metamorphosis of eland lending itself to, and in some ways creating, the socially tense, liminal state that the initiand occupies between adolescence and adulthood. A similar sympathy bond is inculcated in the boy’s initiation, during which he is imbued with eland medicine rubbed into cuts in his skin, and his anointment with eland fat, rich with the agency and power of the antelope. These actions prime the young man for the connection that he might possibly achieve with the antelope during his lifetime, and offer a glimpse into what it is to be eland—an intrusion of its body into his.

This process will be reciprocal; the ontological target will align their norms and thus their forms in turn, the shared moment of understanding one in which each comes close to the other (see

Figure 3).

For hunters and shamans to return to their frame of reference at the end of this process, there must be an invocation of their original contrasts once again, and a return to what made them what they had been before. To do so safely, there is a need to ‘broker’ relations, to appeal to established relationships, give guarantee of what will come after, mitigate the contrasts where they appear, and make the norms match the forms, or vice versa, as social contexts dictate.

6. Powering Social Navigations: The Role of Potency

Navigation is thus an inherently transformative experience, bridging multiple ways-of-being and multiple spheres of existence, and in so doing, changing who and what one is. Successful application of

!nanna-se-type respect observances permit hunting transformations, in which a tracker ‘becomes’ the animal desired—whose energies are acquired in its meat and fat; and dancing transformations in which the dancer ‘becomes’ the animal desired—whose potency is acquired for the purpose of transcendence. It is not possible to undertake any of these acquisitions of potency without ‘understanding’, or what some might call a sympathy bond (

Guenther 2015, p. 278). The bond with any particular species, however, is not a privilege afforded indefinitely, but one that follows the general relativity of social judgements made elsewhere, and thus needs to be routinely re-established. The brokerage of relations between people whose skill permits them to connect with animals lies at the heart of the ‘understanding’ mentioned by |Xam informants, and informs our understanding of rock art that features it. Thus, when people who have the ‘understanding’ of an animal take on its characteristics, interior and/or exterior (

Guenther 2015, p. 306), they are not summoning something that is rightfully theirs, but negotiating and asking respectfully from someone with whom they have built up relations over the course of many encounters.

If these relations mean the animal’s social obligation is to give up its body to the hunter, then so be it—the protocols have been observed (cf.

Willerslev 2007, pp. 102–4). If the animal entity that is being summoned to the healing dances by the women who dance and clap its song is summoned ‘nicely’, the dancers who have an affinity with that animal may access its supernatural power to enter the trance healing state. In so doing, they feel themselves become that animal and, like the hunter who feels himself become the prey, the deliberate mimesis becomes a metamorphosis that can facilitate travel, supernatural feats and perspectives otherwise unachievable (

Guenther 2015, p. 291; cf.

Willerslev 2007, pp. 12, 94). Perhaps the best visual representation of the hunter’s experience of becoming the animal desired is in the Foster brothers’ Kalahari documentary film

The Great Dance: a hunter’s story (

Foster and Foster 2000), in which Karoha, the !Xo hunter, called the Runner, ‘becomes Kudu’ while persistence hunting. These are traversals and transformations brought about in the dance and in the hunt, sharing “neuropsychological [and] psycho-phenomenological [characteristics]—which in turn produce changes in body state and consciousness … Altered states of consciousness arising as a result of physical exertion as practised in the healing dance find expression in San painted imagery” (

Rusch 2016, p. 891). The rigors of one experience recall both the neurological state and phenomenological characteristics of the other. The energies that govern one govern the other. The availability of the energies that permit these traversals is subject to social assessments, with the consequences of mismanagement or normative misalignment shared in these contexts as well.

We can observe these principles in the example of J08 in Highland Lesotho (see

Figure 4). The image is located in a shelter overlooking a valley noted for its richness of game during the summer months (

Challis 2019, pp. 173–74), and thus possessed a richness of agencies able to offer their powers. In this case, we see the struggle to ameliorate the difficult and dangerous, overtly monstrous characteristics imbued in its form by the social and spiritual consequences of consumption: claws, hair, tusks, and a bulbous stomach. An overabundance of supernatural potency in this valley landscape, so full of eland—spiritually and literally housed in the

!gi (potency) of the eland fat. At a very high altitude (2387 m), we find this image in a setting far from the normal spaces of human life, in a place defined by its inhabitation by the powerful, ur-shaman deity

kaggen. Characterised by this formidable inhabitant, and by its distance and thus strangeness, access to this place would challenge all but the most skilled practitioners. Painted in this setting, we find a figure whose monstrous expressions are undoubtedly the result of uncontrollable forces and potency acting on hunter and/or dancer, and the problematic consequences of their consumption. It is apposite, then, that in the same shelter there are painted two figures with rhebok- and eland-eared caps—individuals bearing expressions of the ability to tame (

Challis 2019, pp. 179–80); that is, to mitigate these problematic outcomes.

7. An Atlas of the Social Universe

Taking these principles in aggregate, we can begin to map the social universe that surrounds the images. At its core, it is socio-centric (following

Viveiros de Castro 1998, p. 474), in the sense that the inhabitants of the world mutually define each other, their aligned norms and expressed forms both assessed by one another, and in the process, determined by each other. To be ‘tame’ is for this alignment to be more complete, while to be ‘wild’ is to fail to meet obligations, intentionally or otherwise, or to respond negatively to another’s breach of taboo, often with aggression (see ‘axis of wild-to-tame’ in

McGranaghan and Challis 2016, p. 584), and to take the correspondingly contrasting form (e.g., a leonine one). Intelligibility is in this way a key part of how the world determines itself; if an actor within it cannot understand the others to whom they relate at a given moment, and there is thus no way to align, the world is wilder as a factor of their ignorance (see

Orpen 1874; discussion ‘failures of intent’ in

Skinner forthcoming).

The relationship of form to intent means that social aptness comes also from the ability to read what is presented; a predator is known by its antisocial indicators, while ‘human’ is a constitution through human behaviour and perspective, just as animals are of theirs. That these inclinations are responsive is what drives relations in the world; if an animal will be tame, it will thus take a corresponding form. By this form they make themselves known in a format intelligible to an observer, hypothetically able to understand them and their social signals, and skilfully enact the correct responses. The world is in this way a “field of relations” (

Olwig and Hastrup 1997, p. 8;

Jiménez 2003, p. 139), its varied conditions determined by the ways agencies engage within it. By interpreting environmental responses and characteristics, and enacting an above all cultural assessment of them, “the things of the world will tell [a skilled observer] what they are, and, in so doing, who” (

Skinner 2021c, p. 191; following

Viveiros de Castro 1998, p. 480;

Descola 2013, pp. 121–22).

Engaging socially, understanding one’s obligations and meeting them would render the world safe and stable: it is then a place less predatory, and that thus permits navigation. The longer one has resided in situ, and spent time meeting their obligations, the greater the precedent in that place for familiar forms of behaviour, the more knowledge one would have to negotiate future encounters. Traversing away from this familiar state and these established conditions would elicit ‘different’ responses from the environment; that is, socially unintelligible, strange ones (see

McGranaghan 2014b), scaling in difference and danger as those familiar locales slowly faded from view.

It is ‘strangeness’ in this sense that seems to define encounters that occur in particularly distant (from one’s social frame of reference) locales, amidst unintelligible expressions of culture and identity, and correspondingly dangerous conditions. This is also the setting in which magical occurrences come about. ‘Magic power’ (

ǀko:ξoξ-de; D.

Bleek 1956, p. 320) is the term used to describe this, referring to the capacities of sorcerers, especially in the extents to which they cause illness (e.g., LL.V.19.5484–5485; retaining the equivalence to hunting as it takes the form of “invisible arrows”; D.

Bleek 1956, p. 318). It is also the form that the environment enacts expressions of danger and caprice in moments of violated taboo or social failure (an example being the case of the rain’s ‘magic power’, manifest alongside the dangerous/taboo capacities of New Maidens; LL.V.6.4400′; LL.V.13.4989), so consistent in the ethnography that ǀko:ξoξ-de was originally mistranslated as ‘evil things’ (LL.V.19.5528–5529;

McGranaghan 2012, p. 409).

Read within a framework that positions capacity and behaviour as markers of identity, ‘magic’ functions ably as both cause and indicator of danger, and thus it is naturally a thing that comes about at the margins of social agreeableness, intensifying as social conditions reach their terminal, antisocial locales. Indeed, there are various points of confluence between magic and illness, coming about in raised and choking dust (e.g., LL.V.20.5537–5546, 5557; “that ‘earth/dust’ is not a ‘good/friendly’ thing”, LL.V.20.5542; the “haze that brings illness”, LL.V.20.5557), and expressed in the actions of predatory animals, such as lions (e.g., LL.II.20.1775). They are brought about at the overlaps of antisocial and different behaviours, assessed as magical and dangerous in equivalent extents, and for the same reasons (exemplified in the ǁkhã:-ka-mumu, a “lion ghost”; WB.XIII.2190′;

McGranaghan 2012, p. 447; see also D.

Bleek 1956, p. 139;

Skinner 2017, p. 83).

At the conceptual apex of distance, one could find the

|nu-ka-!k’e (LL.II.36.3242), translated as “spirits of the dead” (D.

Bleek 1956, p. 350), a term representing archetypal villains, and figures suffused with magic. In contrast to the connotation that ‘spirit’ has in Western idiom, this was a community that lived within obtainable reach (specifically, some way north of the |Xam informants’ home range, across the Orange River; D.

Bleek 1956, p. 352; LL.VIII.10.6892′), their identities assessed in the same way as any community would be; through assessment of the culture they expressed, and the norms to which they did (not) align.

They were thought to shoot arrows into the sky, which would fall down upon the |Xam (LL.VIII.22.7972–7974), and are in this way a cornerstone of |Xam theories of disease; they are the ‘dead people’ from which sickness originated (see

McGranaghan 2012, pp. 222–23; cf. “harm’s things,”

Lewis-Williams 1980, p. 471;

Lewis-Williams 1992, p. 57; “arrows of sickness,”

Lewis-Williams 1998, p. 94). Their behaviours are explicable in terms of their distance from the communities assessing them, and thus their implied inability to perform or interpret social cues. Their danger stems from their lack of understanding, which is both cause and effect of their inclination to transfer destructive energies through arrows, in almost exactly the equivalent forms as hunters, vis-a-vis prey, and shamans, vis-a-vis other antisocial agencies (e.g.,

McGranaghan 2012, p. 204). What is important is that the

|nu-ka-!k’e were a distant and antisocial community that could be encountered when travelling too far from home (LL.VIII.22.6892′), or when travelling in trance, for both were inherently transgressive and transformational, and indeed, dangerous by virtue of the distances covered, and the magical implications of such distance (LL.VIII.26.8309′).

In as much as there is a “basic contiguity” between ritual and mundane activities (as above), there is a profound overlap in their theatres. A person far enough from home could experience “numinous” encounters on the hunting ground (e.g., LL.VIII.8.6713–6715), and observe similarly ‘non-real’ mechanisms playing out (cf.

McGranaghan 2015, p. 277;

Skinner 2017), but remain firmly in a standard state of consciousness. This is because, ultimately, the world is not demarcated by its spiritual or profane dimensions, but by its gradients of sociability, the experiences of which would be profoundly determined by one’s own abilities and relations.

Responsibility to one’s obligations determined success in the hunt and in trance; thus, sensitivity to the cultured communities of the landscape, and the ability to put into practice the fundamentally social assessments of those communities, determined not only the outcomes but also the experiences of both. While there would certainly be some sensory differences between foot-travel (running) and trance (flying), it is not the precise mechanisms involved, nor the field in which they occur, that differentiates them. Accordingly, when we consider the atlas of social fields that surrounds the art, or is implied by the oral record, it is one notable for its continuous character between these planes, lacking specifically sacred or profane dimensions. Indeed, its dangerous and magical reaches are accessible under varying conditions, though all require a fundamentally social understanding to traverse.

This offers a tantalising avenue for understanding what rock art is, by the factors of what it does. By representing an animal in an image, and perhaps including elements of its substance in paint for instance, such as blood, a record is made of an interaction between hunter/painter and animal communities. As so much of what a place is depends on the agreements and arrangements that have previously defined it, this suggests that traversal can be guaranteed, and ‘common ground’ engineered. By recording these past interactions in a way that makes them capable of being referenced in present and future interactions, the essential function of brokerage—pointing to mutual understanding—is replicated. Establishing precedent: ‘See, we have met here before’, is served well by showing an imagistic record of human–animal relations in paint or stone. An example of this can be found in the engraved hilltops of the Strandberg, in the Northern Cape, South Africa, a site with great prominence in the ‘heartland’ of the |Xam (see

Deacon 1986;

Skinner 2017).

Particularly notable of the site is its steady decay, the doloritic formation slowly becoming a field of boulders (see

Figure 5 and

Figure 6), themselves developing a dark patina of iron and manganese oxides. Upon these boulders are hundreds of horses, engraved through the patina, and into the pale dolerites beneath (see

Figure 7).

Their marked contrasts make them visible under specific lighting conditions, and at certain angles this causes them to ‘pop’ into view as the solar angle changes (

Skinner 2017). Although this style of engraving is not typical of San art, the site possesses deep connections to the source community and their context and is amenable to interpretation within the corresponding idiom (

Skinner 2017). More to the point, their distribution and the construction of the site as a whole, within the social conditions described above, is one that ‘populates’ the landscape. As previously, significant others are those with whom a human community may entreat, and they will reveal themselves in ways that can be interpreted. This will often be in particular and “conspicuous degree[s] of volitional motility” (

McGranaghan 2012, p. 338), and the images do that here. An animal intentionally revealing itself, or hiding itself from view, is practically represented here by the slow appearance and disappearance of their images from the landscape they have been used to populate. This constitutes the images as those of (significant) individual horses, and the horse-community implied by their distribution across this landscape, in such a way that would signal amenability to negotiation. This, in turn, positioned the animal community as one with a history of contacts with the human one, the erstwhile tenuous conditions of the colonial frontier, in which these images originate, are negotiated in moments of interaction between significant individuals. This, in turn, solidified common ground; the place was a site of communication, characterised by the relations agencies had upon it and more importantly, within it. This site is an engineered social context that permits an open opportunity for humans and animals alike to present their understandings and be understood in turn. (

Figure 8)