1. Introduction

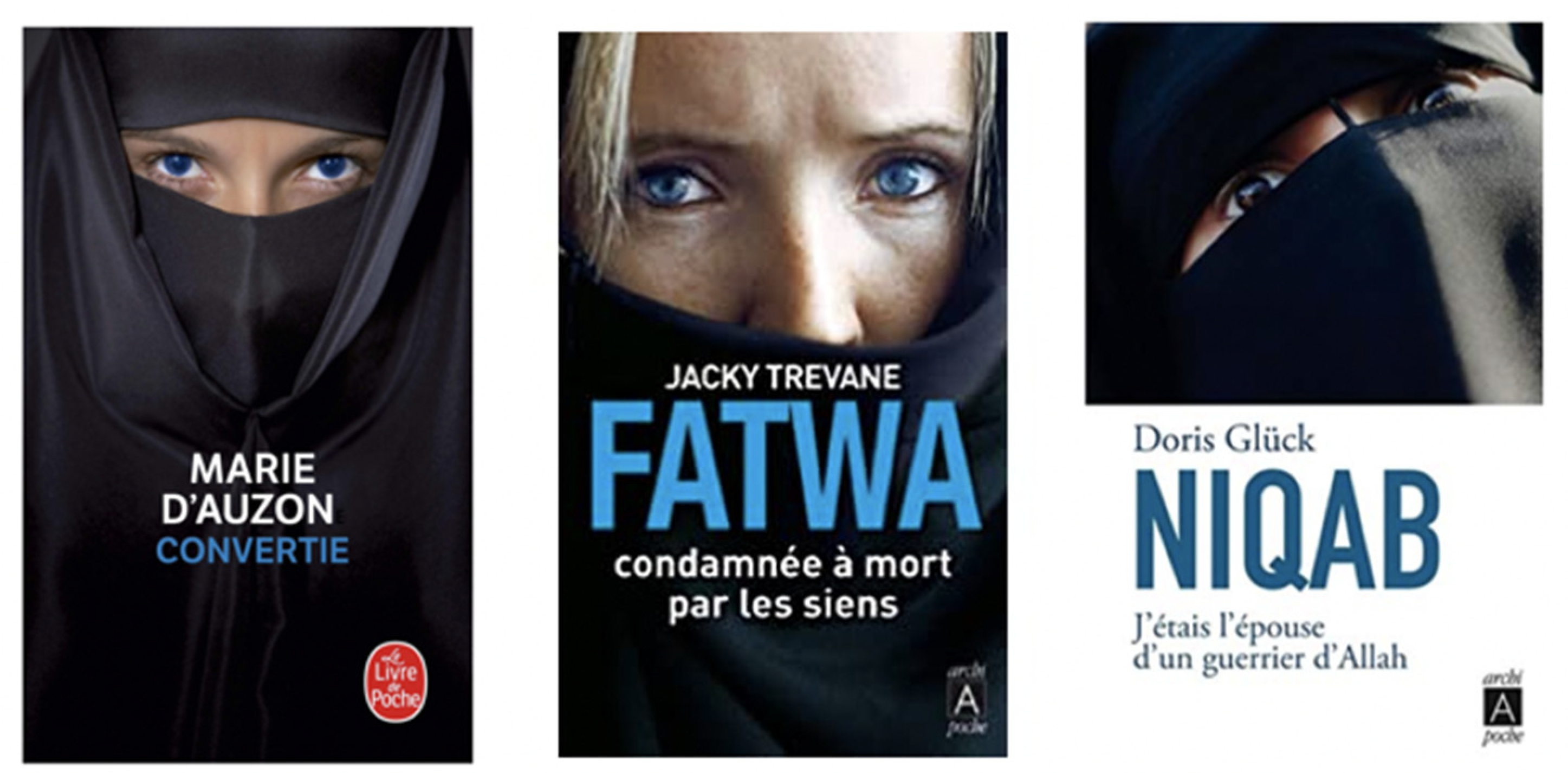

A pair of blue eyes peek out from behind a hijab, on the cover of a book emblazoned with “Convertie”. The blueness of her eyes is engulfed by the dark veil, underlining the meaning of the title: convert. Convertie is a horror story of a white French woman who converted to Islam, one in a series with similar covers featuring sexy yet suffering women, with titles like convert, “Fatwa,” “Niqab,” portraying them as victims of Muslim men—if not Islam itself (see

Figure 1, below).

These books are part of a genre I term true sex crime: they blend violence, sex, and Islamophobia, a kind of 50 Shades of Grey for The War on Terror or the refugee crisis. They tell the story of women who are victimized, abused, and sexually enslaved by Muslim men. Some are young French women, sexually and physically abused by Muslim husbands. Others tell violent tales of young Kurdish or Christian women, sold into sexual slavery by ISIL. All feature women reduced to objects of sexual violence, symbolized by the veil.

If women are victims, Muslim men are villains. This genre’s attitude towards Muslim men is clearly illustrated in one title: Ingrid Falaise’s “Le Monstre.” With the subtitle, it clarifies: M stands for Mari (husband), Manipulateur, and Monstre. She leaves out Muslim, but the implication is clear. Muslim husbands are predators, manipulators, who will target French women. M is for monster; M is for Muslim.

These true sex crime stories create a melodrama that resembles the Indian conspiracy of

Love Jihad. Love Jihad refers to the Indian conspiracy that Muslim men are strategically using love to entrap and manipulate women into converting to Islam, and creating an Islamic state in the bedroom (

Frydenlund and Leidig forthcoming). Frydenlund and Leidig show a broader use of love jihad as an analytic concept, showing the intersections of sex, gender, and nationalism in imaginaries of the Muslim Other (2021); Muslim men are violent; they will capture and rape women; this dominance, manipulation and violence allows them to outbreed others. Concepts of love jihad occur frequently in these French novels. First, they frame Islam as uniquely violent and dangerous. Second, they frame Muslim husbands as manipulators and violent, equating them with ISIL warriors. Love is always a kind of war: conquering or converting.

This conspiracy, which originated in India, echoes the French author Reynaud Camus’

Grand Remplacement, (Great Replacement), the theory that cultural decline is occurring because elites are replacing White French people with weaker immigrants, which has been expanded to all of Europe. (See

Tebaldi 2020 for further discussion of this in the French context). However, in love jihad it is Muslim men’s culture and sexuality which is the real threat rather than the nefarious elite.

These tales also focus on constructing an image of Islam as connected to sexual violence, and focus on saving (white) women, making them acceptable to readers who might not ever consider texts like

Le Grand Remplacement or the genocidal novel

Le Camp Des Saints. These sexualized horror stories of Islam are pulp (non)fiction, but they are more than Bush’s beach reads. Crime stories are important sites for the production and ratification of ideologies, especially cultural ideas of villainy and punishment (

Knight 1980). While violence against women in ISIL-occupied areas, or in France, is a serious issue, these stories are used to normalize tropes of the Muslim man as the “repugnant other” (

Harding 1991), who is hypersexual, misogynist, and violent. These circulating stories also have real consequences for immigration and cultural politics in France. They provide semiotic resources, which can normalize far-right political parties such as Marine Le Pen’s National Rally. Moreover, as Miriam

Ticktin (

2011) explains, dominant cultural narratives of Muslim women as victims of sexual violence influence mainstream asylum and immigration policy.

These “true stories” are tales of femonationalism, which

Farris (

2017) shows as a convergence of two ideological threads. The first is the instrumentalization of feminism for nationalist ends, as when Le Pen uses gender equality to elevate the French and attack Muslims and migrants as backwards. Second is the characterization by liberal feminists such as Elisabeth Badinter of Islam and Muslims as inherently oppressive and anti-women, meaning that Muslim women are in need of saving by White feminists—a discourse often seen in anti-veil polemics (

Fernando 2013). These texts illustrate this vision of an oppressive, backwards culture and, as Abu-Lughod notes in the American context, they echo older “civilizing mission discourses, characterizing Muslim women as in need of saving to justify Neo-colonial violence and control”.

These texts make femonationalist politics affective, giving readers a sense of compassion for their innocent victims—and a frisson of sex. In this paper, I analyze how these sex-crime stories construct affect, using cover art and text from 50 books, and a close reading of three. I then ask how affect, images or “public words” (

Spitulnik 1996) circulate in both strands of femonationalism: first, I address the use of women and femininity by the nationalist right by analyzing three of Marine Le Pen’s May Day speeches and the National Rally’s social media hashtag #laracailletueunefrancaise; next, I explore the mobilization of Islamophobia by mainstream French feminists in comments by three successive ministers for women’s equality. These stories and discourses reflect the themes of Love Jihad, positioning Muslim sexuality as uniquely dangerous and violent for the woman and the national body.

2. Materials and Methods

To approximate the way a reader might naturally encounter the books in this paper, I used Amazon.fr‘s recommendation algorithm. First, I chose their top-selling book in the rubric “terrorism and society”,

Ils Nous Traitaient comme des Bêtes, by an author known only as Sara. I then saved the titles and cover images for the next ten pages of recommendations. Second, I searched using the keywords “Daech” “Djihadiste” and “Niqab” (ISIL, Female Jihadi, and the full-face-covering veil), and recursively looked at the results for recommended books using those search queries. I excluded sexual crime books that were not about Islam, and books about ISIL that did not feature female victims. This created a corpus of 60 book covers and back texts. This corpus was then open-coded. Please see the

Appendix A for a list of titles and themes.

Of these books, I closely read three representative texts: Ils Nous Traitaient comme des Bêtes, the most popular text; Evadée de Daech (Escaped from ISIL), another text about Kurdish sex slaves; and Convertie (Converted), a text about a French woman who converts to Islam and suffers sexual violence. These books were open-coded for the most central themes (i.e., sex, violence, modernity, women’s rights) and then digitally searched for keywords representing these codes (i.e., terror, sex slave). Particular attention was paid to how themes such as innocence or modernity were realized in the discussion of sex.

After having determined the key themes of these texts, I searched Marine Le Pen’s archives, the National Rally Social, as well as the public statements by ministers in France for discourses on Islam, sex crimes, and veils. I chose Le Pen’s May Day speeches for her discussion of women and nation, and those by the ministers for women’s equality as a way to explore the ways in which feminism and Islam were opposed. Here as well, particular attention was paid to how the themes of sex, body, and fertility were used to discuss political issues.

I drew on the anthropology of mass media (

Spitulnik 1996) to explore the semiotic construction and circulation of affect, that is, how language and images create affect that attaches to some bodies, shapes borders, and moves between them. Data were coded and then analyzed using a framework drawing on Spitulnik and Sarah Ahmed’s understanding of affect, and analytic tools from Irvine and Gal’s discussion of the semiotic construction of difference. Ahmed’s work on affective economies (

Ahmed 2004) explains affect as ‘sticky’; like discourse, it circulates between bodies and sticks to some, thus shaping how we see and relate to them. Some bodies, such as those of veiled women, connect to affect regarding innocence, victimhood, or threat in French femonationalist imaginary. Ahmed allows us to understand how affect, especially fear, hate, love and desire, can be mobilized to create love for the nation. Spitulnik’s understanding of “public words” helps to elaborate on how affect can circulate; she shows how language from “minor media” such as radio or an unpopular twitter account like my own, or these true sex-crime stories, can make its way into broader discourse—bringing affect with it. Here, words such as burka, niqab, and especially veil and slave, circulate between sex-crime stories and ministers’ speeches.

I also draw on theories of linguistic differentiation from Irvine and Gal to help understand how these discourses shape differences between Muslim and French sexuality. Linguistic differentiation occurs in three movements: erasure, iconization, and fractal recursivity. Erasure hides all the internal differences within a group, erasing the difference between Muslim husband and ISIS warrior. It does so to highlight their difference to French men, creating a predatory, fundamentalist “repugnant other.” Iconization makes something that was merely pointing to a quality come to express its essence—the veil is no longer an index of Islam, but the essence of Muslim men’s view of women. This icon of oppression circulates widely. Fractal recursivity shows how differences are repeated across scales, so that these stories’ oppositions between the good Frenchman and the bad Muslim are scaled-up to stories of the good French nation and the bad Muslim immigrant in the political speech of Le Pen.

4. National Rally

These stories’ framing circulates to and from far-right discourses. Again, they mobilize discourses of difference between the Muslim male, with his violence and hypersexuality, and the good native French man. Following Irvine and Gal’s theory of fractal recursivity, they scale-up these differences to the level of the nation: not only will the single Muslim man violate a woman, but all migrants will violate the borders of la France. The cherished nation is imagined as a female body, threatened by the other, and the woman is imagined as the nation, whose purity and fertility must be protected. The national symbol of France is a beautiful young woman, called La Marianne.

Drawing on the same sexual constructions of violence and innocence as the sex-crime stories, far-right discourses frame the nation as the potential sexual victim of Muslim men. The sexualized stories provide

Ahmed’s (

2004) affect as “sticky”. Affects, especially love, sex and fear, work together to link the individual to the far-right politics of the nation. As Ahmed suggests in

Affective Economies (2004), hate for the other binds the body of the nationalist to the nation, creating love. This affective binding is essential. French far-right politics often are what

Holmes (

2010) calls integralist; they link a people, a land, and a culture together in one essential unit. This unit is often expressed in far-right discourses as female, as a mother who gives birth to the nation, cementing the link between land and people; the land serves as a vulnerable woman, whose purity must be protected. Many suggest that France is a land that should be loved like a woman, a theme frequently repeated in the speeches of far-right party leader Marine Le Pen.

Le Pen is the leader of the far-right party the National Rally, known in part for her “dediabolization” of far-right, nationalist and anti-immigrant politics, which she accomplishes in part through femonationalist discourses that instrumentalize both feminism and femininity. As a female far-right leader, she can mobilize women’s empowerment in her anti-immigration discourses; Le Pen is known for using the language of femininity and family (

Alduy and Wahnich 2015) to soften far-right discourses. These not only soften, they make the discourse deeply affective, drawing on similar tropes to the true sex-crime stories (see

Figure 2, below).

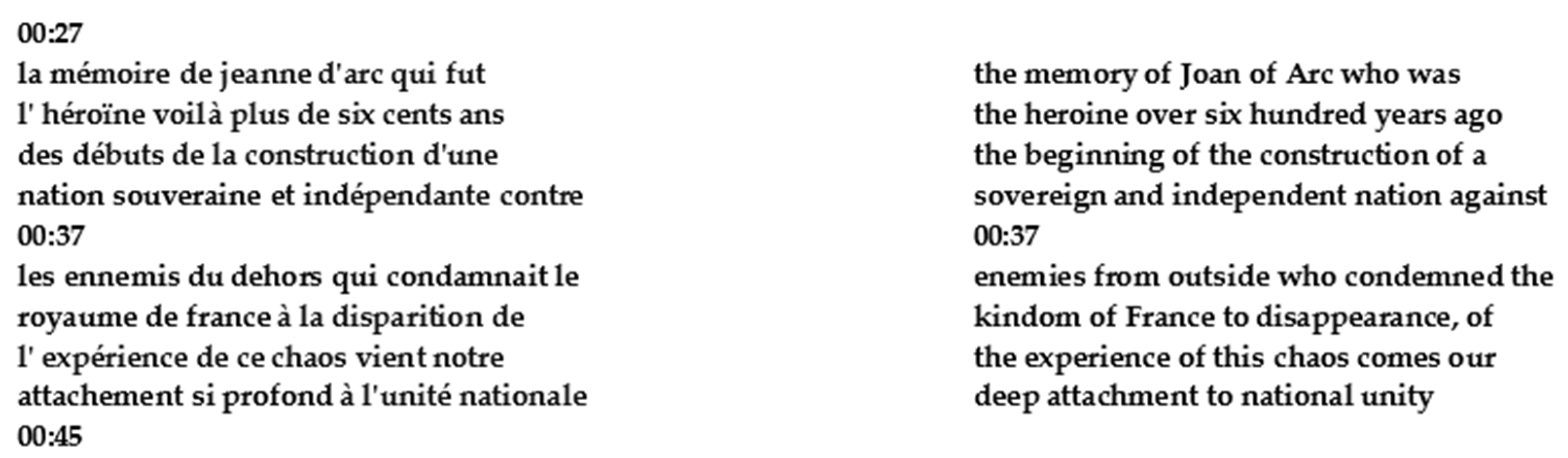

A close analysis of her May 1 speeches, using Youtube’s transcription functions, demonstrates how romance and sexuality are used to shape nationalist discourses, beginning with the evocation of Joan of Arc as the heroic woman and symbol of the nation. Here, Le Pen constructs a femonationalist (

Farris 2017) vision of a female France through Joan of Arc, who is both hero and victim, with the migrant as a villain. May 1 is celebrated as Joan of Arc’s birthday, and each year, Le Pen evokes her in the first few seconds of her speech, as in the example below from her 2019 speech.

Here, in less than 30 s, we evoke the symbol of the nation, which is immediately linked to a long tradition and history, threatened by external enemies. This threatened yet courageous female France is meant to prompt our deep attachment to the nation, as Le Pen continues “l’amour de la patrie c’est le premier amour” (love of country is the first love). Not only is this feminization of the nation linked to love, it is also compared to a threatened physical body, using the affect of love (and sex) to demonize the other. Le Pen directly compares the nation to a body, with borders like (white) skin: “Comme la peau humaine, elles laissent passer ce qui est bon et bloquent ce qui est nuisible ou dangereux” (like human skin, they let pass what is good and block what is harmful or dangerous). The nation as body promotes attachment to it, and exclusion of the other. Within this language of the nation as a (female) body, immigrants and migrants are dangerous or damaging—crossing a border without permission is similar to rape or sexual violence. Marine Le Pen’s emotive style is considered a key to her success (

Baider and Constantinou 2015).

Clifton (

2013) notes that Le Pen frequently uses these “adversarial standard pairs”, which paint all beloved objects as under threat; this language is designed to promote the circulation of affect—desire, love, hate and fear—and bond these to the country.

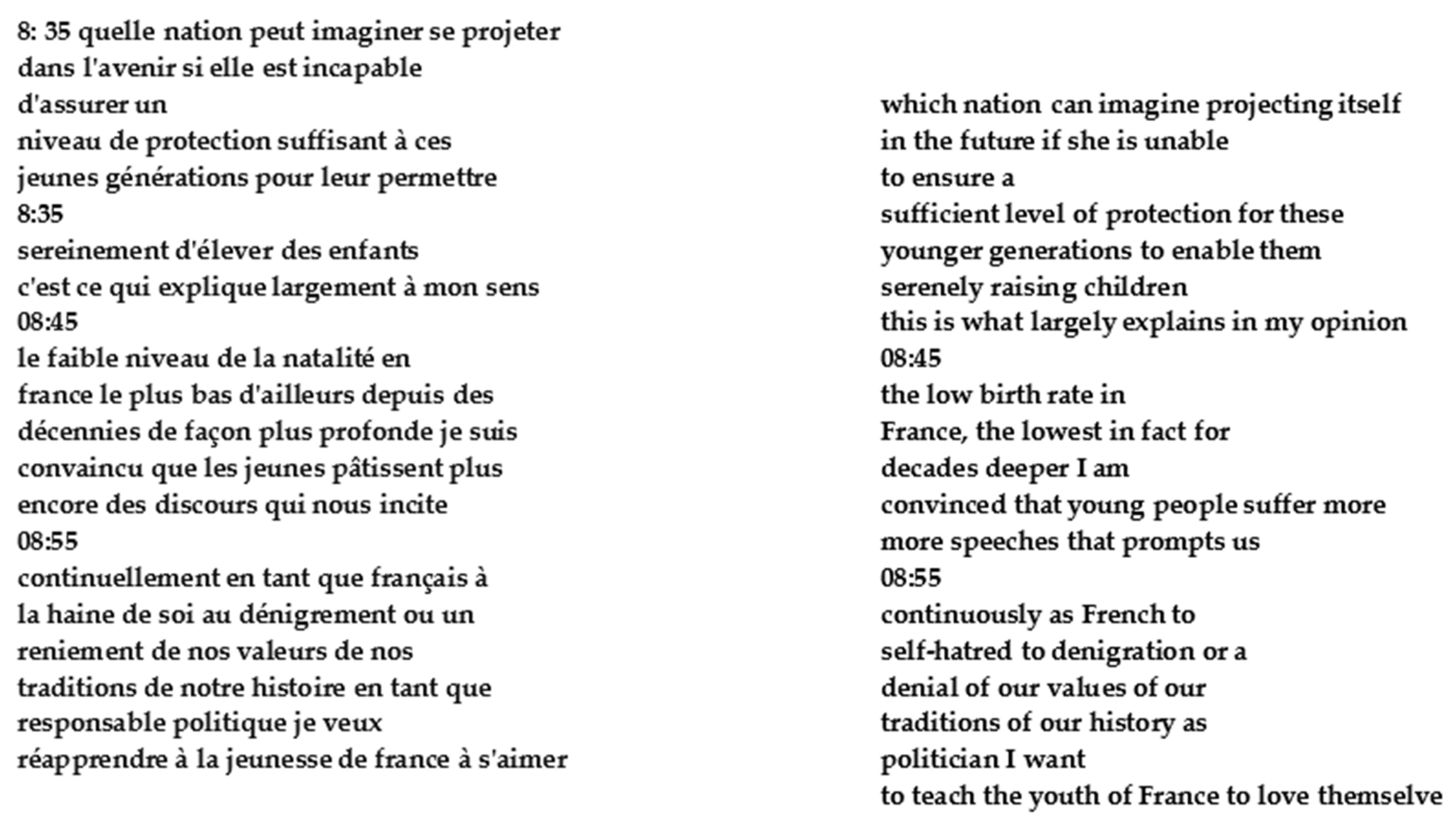

This is continued in her May 2021 speech, in which she explicitly links patriotism to pro-natalism, encouraging an increased birthrate, and portraying women as responsible for reproducing and strengthening the nation. This is linked to the conservative strand of femonationalism, which uses women as literal as well as metaphorical mothers of a nation (see

Figure 3, below).

At 8:35, Le Pen’s national body is a woman with few children, who cannot metaphorically ensure her future survival. This quickly connects with far-right fears about lower white birth rates and changing demographics, as in the conspiracy theory of The Great Replacement. Muslim traditionalism, while framed as negative in discussions of immigration, is also used to shame modern French women who do not have many children. This connection is confirmed when Le Pen continues, at 8:55, to show how the love of France, values, and traditions should result in more children, with the verb “s’aimer” suggesting that the youth of France should love themselves (as French) and love each other. This low birthrate is thus the result not of changing socio-economic conditions but of the lack of love for their country and French identity—babies are made for the nation, and loving the nation creates babies. With this emphasis on tradition and serenely raising children, Le Pen also suggests that women should return to this role. In Le Pen’s speeches, the nation is sexualized, and portrayed as either under the threat of rape or disease from the Other, or normatively producing (white) French babies.

These images also circulate beyond the far right, through what Spitulnik refers to as circulating “public words” and images. Public words take crumbs of affective language and circulate them in new contexts; this is especially interesting when applied to social media hashtags and memes, which are designed to travel widely. Here, in

Figure 4 below, in the national rally’s twitter feed, we can see how two images from these sex-crime stories circulate: the icon of the burka and the Muslim rapist; the victim and the villain.

First, the construction of the migrant as violent criminal is shown in the national rally’s hashtag #La Racaille Tue Un Francaise. Racaille

1 is like the English “thug”, a term which racializes criminality and has a long history of referring to Black and Brown French men. This hashtag was used to say that the “racaille” killed “une française”, a French woman, painting all “racaille” as a potentially violent menace and separating them from Frenchness (this was not un français tue une française). Reflecting the slogans of the far-right white nationalist group,

Generation Identitaire, this phrasing was taken up by Marine Le Pen’s party the National Rally (RN). This hashtag was used on their twitter to highlight violence committed by Black and Brown men. It was perhaps designed to reach beyond the RN, as evidenced by this phrase’s use in RN rallies and protests, as shown in

Figure 5. Much like the books linking ISIS and Muslim husbands, here, crime against women is racialized.

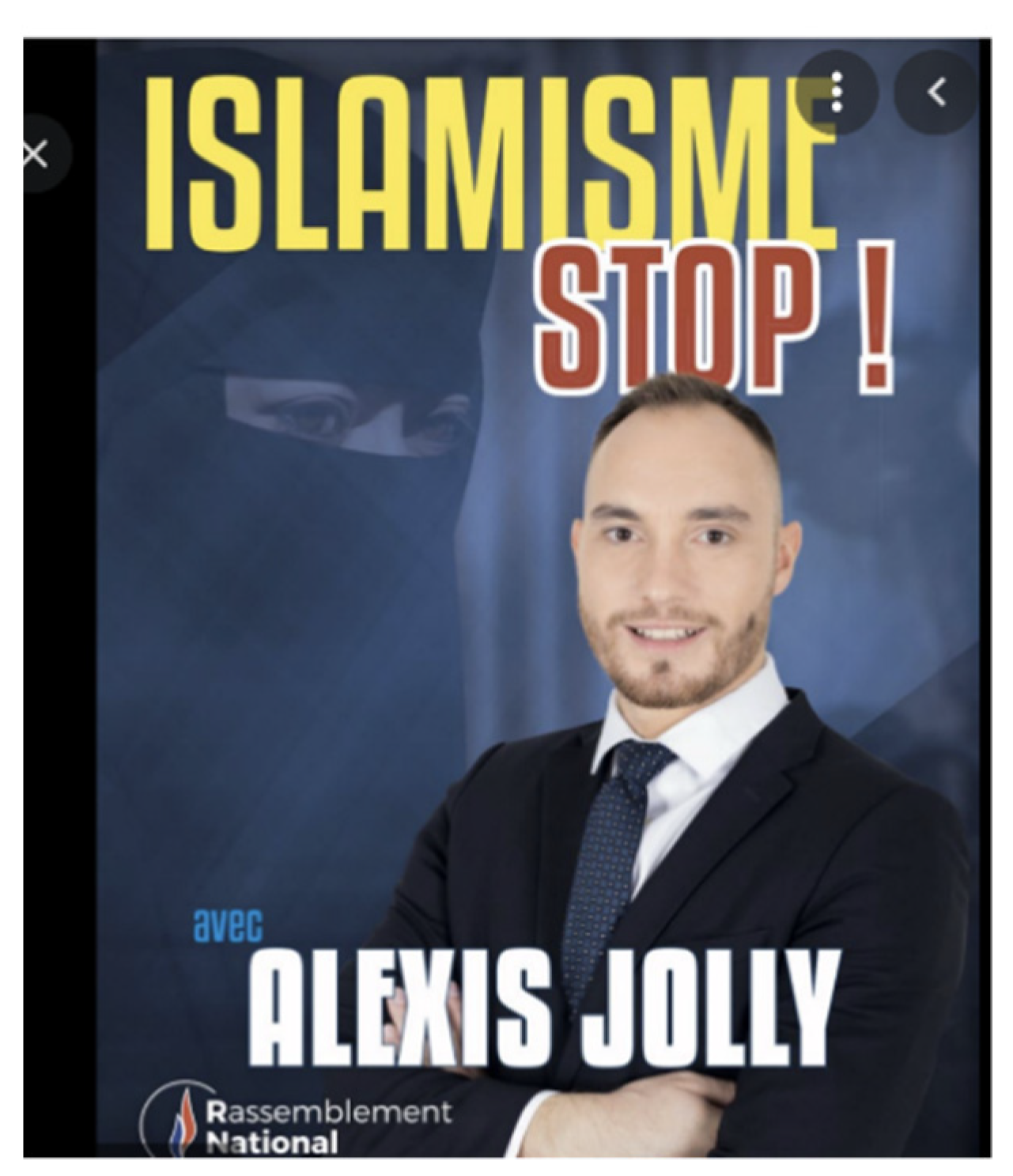

Second, the burqa is invoked as evidence of Muslim men’s inherent criminality against women—again, as a kind of icon of oppression. In

Figure 5 below, the images from a campaign poster by RN candidate Alexis Jolly are shown. Jolly is posed in a conventional candidate way, which is similar to the cover design of one of these popular

temoignages.

The background of the ad is a woman in a full-face veil, which is again portrayed as an icon of oppression and violence against women. Much like the book covers, the title is in a bold, high-impact font with few words—“Islamisme STOP! —and then a fuller explanation at the bottom. It follows all of the visual conventions of these books in terms of the font, color scheme and high contrast, and the conventional images of veiled woman. However, here, the woman seems almost more of a menace than a victim, with Alexis posed in between her and the viewer, as though to say I am what stands between you and this vision of womanhood, this future for France.

The veil represents a victimized woman but also a threat to the nation, as shown in

Figure 6 below from

Riposte Laïque. Riposte Laïque, in English secular retort, is a reactionary website, which frames itself as in defense of secular values, but is really anti-Islam, as shown by their front page’s elevation of far-right authors such as Eric Zemmour, who compared immigration to suicide. Using secularity as an arm against Islam is common, especially in debates about the veil. Here, the secular reactionary site’s image of a veiled Marianne—the national symbol of France—is used to shock. Marianne is the symbol of the French revolution; the beautiful female embodiment of the secular values of liberty, equality, and fraternity; for some, the goddess of liberty. Here, another revolution is shown, with a new symbol: Marianne veiled.

In response to the comment by the former (nominally) socialist president of France, Francois Holland, that Marianne could wear a veil in future, this image is reimagined to show Islam as a threat of violence to French women. It also shows the veiled woman as i that threat incarnate. Muslim men are imagined not only as hurting or killing French women, but converting or replacing them with these veiled women. Marianne, as symbol of the nation, represents the Islamization of France when portrayed in a veil.

In the far-right discourse, we see one thread of femonationalism: the link between woman and nation, and the mobilization of some pro-women language for conservative ends. This is particularly evident in their concerns regarding birthrates and purity, with the desire for women to have many children being at odds with the feminist language they deploy. Similarly, the rights of women and their security quickly become mobilized towards anti-Islamic fear and national power. This is the feminized version of the great replacement theory.

5. In Mainstream

These true sex-crime stories do not merely parallel far-right discourses that construct the Muslim male as violent and sexually predatory, and the French nation as his victim, but also circulate within more mainstream French liberal femonationalism. The French right focuses on violence and anti-immigration, but these same themes of the veil as an icon of slavery and oppression circulate in liberal feminism’s anti-veil discourses.

As

Ticktin (

2008) notes, these affective metaphors unite liberal feminists and right-wing anti-immigration activists. This is particularly evident in French liberal feminism’s polemics against the veil. While the right’s femonationalism holds up women as mothers of the nation who must be protected, echoing far-right conspiracies about Muslims replacing native born babies, French liberal feminists hold up women’s rights as a symbol of the country’s tolerance, progress, modernity and value. This becomes femonationalist when it suggests that France, unlike Iran or Iraq, for example, is a valuable, enlightened country because of its feminism and secularism. The modernity of the country is proven by the modernity of its women, shown by their lack of veil. This vision of the veil as an icon of sexual and social oppression, of the woman transformed into

femme-objet, is shown in French ministers speeches on women’s equality on the left and the right, as well as in broader policy discourses on veils and sexual trafficking.

Mainstream discourses often take on greater institutional power, and so the consequences of discourses framing veiled women as victims and Muslim men as villains are also clearly felt. As

Blommaert (

2009) explains, asylum seekers’ discourses and stories need to align with dominant understandings of the nation and national order. These must be legible as the type of story that immigration officials expect and can empathize with, not too similar to, but reflecting, the culturally dominant categories of victim and villain (as in these novels). Ticktin points out that these circulating stories of Muslim women as victims of sexual crime clearly influence what types of crimes are seen as real and serious, and which crimes are seen as necessitating asylum—most often sexual.

In Ticktin’s analysis of migration policy, perceived innocence and exclusion from the economic sphere, as well as conformity to cultural narratives, create the deserving asylum seeker. The ultimate innocent is the sexual victim, such as the one in these love jihad books, who has no agency, choice, or capacity as a worker. She is the “whore of the caliphate,” not your cleaner or babysitter. Sexual victimhood instead highlights right-wing discourses of female purity and national sovereignty. Sexual threat is racialized; white French men are not the criminals. Prominent liberal feminists such as Elizabeth Badinter defend white males, calling sexual harassment charges a “witch hunt

2”, while hundreds of wealthy French women signed an open letter calling for the “liberté d’importuner” or the freedom to hit on people and celebrated the French tradition of seduction. The stories that asylum seekers tell need to paint them as the right kind of victim, of the right kind of crimes, so that they can reinforce narratives that paint French sexuality as moral and Muslim sexuality as criminal.

FitzGerald and Freedman (

2021) note that this dominant narrative also shapes current trafficking policies. The EU policy focuses on sexual trafficking, again portraying Muslim women as the victims of sexual violence and dehumanization. While this is true of women from many countries, such as Thailand or Russia, the asylum discourses emphasize women not as sex workers but as sexual victims. This erasure of work and agency also erases the use of immigrant labor in homes and service industries, creating a dominant image of the sex-trafficking victim, one that again paints minoritized men as criminal and encourages carceral feminist solutions to migration. This reflects Farris’ intertwining threads of femonationalism: the nationalist mobilization of feminism, such as the language of dehumanization, in nativist politics, and the feminist uptake of these politics and discourses. Both frame outsiders as the true sexual and social threat, not the white, upper class French

frotteur: a businessman who rubs up on women in the metro.

This link between the veil and sex crimes and the objectification and commodification of women is also reflected in policy discourses regarding the ban on the full-face veil.

Patton (

2014) shows how official policy draws on (despite misreading) Levinas’ understanding of the face as central to humanness. Covering the face, then, is an essential refusal to see women as human, their reduction to objects who can then be bought and sold. The veil itself is the dehumanization, the reduction to

femme-objet. This is also expressed by the condemnation of the veil from ministers for equality under both center-left and center-right administrations.

Yvette Roudy, the minister for women’s equality under the Socialist party from 1981 to 1986, the translator of

The Feminine Mystique into French and the sponsor of an equal pay law, stated quite baldly, “Moi, j’interdirais le voile”—that she would ban the veil and that a Muslim feminism was impossible.

3 The veil was proof of Muslim feminism’s impossibility: a symbol of “submission” of women and the “regression” of French society. Here, they invoke what

Scott (

2011) terms sexularism, the use of a liberal feminist vision of women’s economic and sexual freedom to prove French modernity and progress; this secular, sexual modernity is framed less in opposition to French tradition than in opposition to a vision of Islam as anti-modern. Why was it Muslims, rather than Mitterand’s abandonment of socialism, that made French society regress?

The minister for women’s equality under the mainstream right president Nicolas Sarkozy, Laurence Rossignol, compared women who were wearing veils to

«nèg--s qui étaient pour l’esclavage» “n—-rs for slavery”

4, taking language that could be directly taken from the books that frequently compare veil-wearing Muslim women to sexual slaves, whose covers directly recall black Muslim women slaves. She compared the veil to a set of manacles, again making it an icon of oppression, but any veneer of progressivism is removed by the use of an anti-black slur to refer to these women.

Slave becomes a circulating public word, used to designate the oppression of women, not by French people, but by Muslim predators.

Marlene Schiappa, the minister under current president Emmanuel Macron, continued to insist on the ban on headscarves in school. She introduced bans on street harassment and “wolf whistles” and increased the penalties for sexual crimes, a carceral feminism that explicitly envisioned Muslim and other minoritized men as the villains—as shown in the bill’s promotion of the loss of citizenship and deportation of men convicted of sex crimes

5. This was critiqued as femonationalism, as it blended race, migration, religion, and integration with a vision of protecting women—however, Schiappa was rewarded for this by a promotion to Minister for citizenship.

Words, icons and affect recirculate between these stories and mainstream political discourses. They portray the veil as an icon of oppression and the sexualization of female submission. They recirculate the use of the word slave to refer to the objectification and total domination of women, and reflect its use in the books as “sexual slave”, with a focus on migrant women in sex trafficking and Muslim men as sexual criminals. Finally, they link Islam to regression and paint it as a danger to the country. The center may not say “love jihad” out loud, but they reflect many of the themes of these stories and the broader right. These paint Muslim men and Islam as uniquely dangerous for women.

Here, we see the intertwining threads of femonationalism, as French liberal feminists attack Muslim and migrant men in the name of women’s safety and women’s rights. These align with the right’s mobilization of womanhood as a symbol of national purity, which is in need of defense. The conflicts between these two groups—liberal secular feminists, and the traditionalists worried about motherhood and birthrates—are resolved or suspended by a mutual demonization of Muslims. We do not need to ask about sexual harassment, spousal abuse, or the limits of liberal feminism. When native-born French men are the perpetrators, this is our cherished French seduction.

6. Nationalism, A Love Story

A deeply affective set of images are constructed within these true sex-crime stories. Muslim women are victims, innocent, with their veils serving as icons of a submission that is both social and sexual. Muslim men are predators, raping, objectifying, and enslaving women, icons of an atavistic anti-modern Islam. Within far-right immigration discourses, these are extended to the nation; the nation is imagined as a body whose borders can be penetrated, and violated. Immigration both brings in potential rapists, and is itself made analogous to a kind of rape. Liberal discourses also frame Muslim men as criminal and their crimes as often sexual while describing the veil as a form of submission or slavery. Uniting these forms of discourse is a deep sexualization; the books tell the story of the caliphate’s “whore”, not its prisoner, and stresses her “sexual slavery”. These are discourses of fear and desire that, as Ahmed explains, affectively link the body of the reader to the body of the nation.

If the victims are veiled women, marked with this sign of submission, and villains are predatory soldiers and ISIL fighters, the heroes are the readers of these books. They position the (female) reader as a heroine who would also go out and save the children or rescue a veiled woman. As

Selby (

2014) notes, this vision of the veiled woman also creates the ideal white body by contrast. These stories elevate or titillate the reader, but they also warn her what would happen if she were to marry the wrong kind of man—not only her own victimization, but that of the nation. Le Pen positions her listener as Joan of Arc, who guards her own borders and keeps her legs shut to foreign men. She is a heroine if she loves her country and produces ‘native’ non-Muslim children, or if she joins with ministers for equality to ban the veil and deport presumed Muslim sex criminals. Stories such as these help to promote the affective investment of white women in these nationalist politics.

These kind of true sex-crime stories, or love jihad romances, may mainly exist in France, but the use of sex scandals to promote women’s investment in nationalist or capitalist politics extends beyond this. As

Abu-Lughod (

2002) notes, this vision of the white hero saving the veiled woman gained broad cultural traction after 9/11, at a time of growing American militarism.

Goodwin (

2020) shows how, in the American context, films such as

Not Without My Daughter promote “contraceptive nationalism”, which taught women that a good romance was one with a white, Protestant man. Stories like these may serve as warnings for will happens if women do not marry a white Protestant man, and encourage women to police these boundaries. More research is needed on the ways in which sexuality and nationalism are linked, through popular culture, to make nationalist politics seem normal, virtuous, or even sexy.