1. Introduction

The world we now inhabit is the consequence of interspecies relationships that have evolved over time. We usually think about this in terms of the scientific evolution of interactions between species and environments, shaping concomitant development. However, within this much larger evolutionary context, in which homo sapiens only emerged very recently, there is a crucial sub-category of evolving relationships: between human groups, the material environments in which they live, and the non-human beings that also inhabit these. These relationships contain diverse trajectories of development, in which changes in societal modes of engagement with the non-human world are simultaneously social, political, technical, and cosmological. Each societal trajectory is unique, and by no means as simple or linear as might be suggested by any reductive summary, but there are discernible recurrent patterns that a ‘big picture’ comparative analysis can reveal. Although this paper recognizes the limitations of larger cross-cultural comparisons, it seeks to make visible the recurrent factors that set societies on such different trajectories.

This calls for a methodological caveat. While such ‘big picture’ comparative analyses can reveal recurrent patterns in human development that are otherwise obscured by historical and ethnographic specificities, such an ambitious scope cannot realistically provide much substantiating detail within the length of a journal article. Even the related book (in press), which also rests on my long-term studies of this topic, is at best a hugely reductive summary. As an anthropologist, I am highly cognizant of the costs of sacrificing the ethnographic depth on which our theories generally rely, and the anxieties about generalizing theories that comparative analyses generate. However, a lifetime of studying human-non-human relations in multiple historical and cultural contexts has persuaded me that there are benefits in being able to discern and make visible the surprisingly consistent ways in which changes in social scales, technologies, and practices act upon religious and political ideas, and vice versa. I think that the larger patterns revealed are not only intriguing but can also contribute to our understanding of how we might compose more sustainable human-non-human relationships.

Some societies, particularly those safely ensconced in relatively remote areas, and thus only recently subjected to colonial invasions, have retained many of the features of early human societies illustrated in archaeological records. Despite the multiple and often highly disruptive effects of colonialism, and the increasing influence of being drawn into larger societies and their lifeways, they have remained small in scale, and reliant upon low-key economic practices such as hunting and gathering, horticulture, and subsistence farming. They have continued to uphold relatively non-hierarchical political structures, with cosmological beliefs that tend to be focused wholly, or at least substantially, on the worship of non-human deities. They have retained—for the most part—sustainable traditional practices, and a philosophical commitment to perpetuating sustainable environmental relations in the future.

Other societies, meanwhile, have embarked upon rapid developmental trajectories. In broad terms this has most often entailed transitioning first to larger-scale agriculture, enabling population growth, and moving on to urban developments and industry. They have exhibited increasingly hierarchical political arrangements and, having outgrown the places they inhabited originally, have often embarked upon hegemonic expansion. Their cosmological beliefs have changed radically along the way, most critically in shifting the focus of religious worship towards humanized rather than non-human ‘nature beings’, with similarly major shifts in the gender relations that religious beliefs express. In the process, they have adopted far less sustainable ideas and practices.

This paper, therefore, seeks to elucidate what these diverse trajectories have meant for human-non-human relationships, and for gender relations. Based on my own and others’ ethnographic research, and on historical and archaeological studies, it is fundamentally Durkheimian in its approach, taking as a foundational precept that societies’ cosmological beliefs and practices mirror their social and political arrangements (

Durkheim 1961). It adds to Durkheim’s tenets an additional hypothesis: that cosmological beliefs are also deeply influenced by people’s engagements with the material world, and the extent to which their technological developments are aimed at imposing instrumental control over it (

Strang, fothcoming). This provides us with a way to consider how, in many cases, societies have shifted from sustainable lifeways working in relatively egalitarian partnerships with the non-human world to highly unequal relationships seeking to achieve dominion over the material world and non-human species, to the extent that these modes of engagement have become exploitative and destructive.

As my use of the term ‘cosmological’ implies, I am not drawing a distinction between religious and other cosmological explanations of the creation of the world and its living kinds, or between religious and secular aims to promote particular lifeways guided by particular beliefs and practices. I would rather suggest that in all cases religion is highly political in defining and locating power and authority, and politics are permeated by religious assumptions about what constitutes proper social and material arrangements.

2. Sustainable Trajectories

It is helpful to consider the (loosely) shared characteristics of the early and remaining societies that practice what has popularly been described as ‘nature worship’, although this terminology erroneously implies a dualistic vision of culture and nature that has been imposed on them by others, and which does not reflect the holism of their own beliefs. Indeed, one of the most important aspects of the human-non-human relationships within such societies is that they make no conceptual division between human and non-human living kinds, or between human cultural life and the material world. What they envisage, instead, are relational cultural landscapes animated by both male and female totemic ancestors and non-human deities, and living kinds who, in many belief systems, shift readily between human and non-human forms. In such historical and cultural contexts, the non-human world is framed as a sentient, agentive partner in events, and non-human deities authoritatively manifest its powers. This traditional recognition of the agency of non-human beings, and their ‘democratic’ participation in the co-production of land and waterscapes, naturally inculcates respect for non-human needs and interests and encourages sustainable practices (

Lucero 2018, p. 327).

There are some important variations even within societies that have retained key elements of nature worship. Smaller-scale groups, such as hunter-gatherers in Australia, Africa, the Amazon Basin, and the Arctic regions, are often the most conservative, demonstrating circular economies, low-key resource use, and—along with careful population control—little impetus for expansion. An ethnographic example of just such a small-scale society is provided by my own fieldwork examining indigenous lifeworlds in Australia, where, although there are variations between the many language groups across the continent, traditional cosmological beliefs share common ground in valorising a great Rainbow Serpent, a supernatural being that manifests the powers of water (

Strang 1997,

2002;

Taçon et al. 1996).

This major ancestral figure is the primeval source of all of the other totemic beings that emerged from the land and water in the Dreamtime to form the world and its living kinds. Although this nomenclature suggests a long-ago creative era, Aboriginal concepts of space and time are more cyclical than linear, and the Dreamtime is generally referred to by Aboriginal elders as ‘where’ rather than ‘when’. Conceptually, therefore, it is a non-material domain that co-exists with the visible, material world of the present (

Morphy 1999, p. 256). Representing both genders, the Rainbow Serpent continues to generate human and non-human life in a continuous creative hydro-theological cycle, as well as providing The Law, a body of traditional knowledge providing a template for all aspects of life. Other totemic beings are similarly non-human in form and represent both genders. Beliefs in non-human ancestral beings, and adherence to the Law, have allowed Australian indigenous people to maintain highly conservative lifeways for millennia (

Flood 2010;

Mulvaney and Kamminga 1999;

Strang 1997).

I do not wish to romanticise early or contemporary hunter-gatherer and other small-scale societies as enjoying ideal gender equality. They typically ascribe different roles to men and women, and archaeological records and historical ethnographies suggest that, even prior to the influence of more patriarchal societies, men tended to dominate public interactions, most particularly those involving interactions with other groups. However, there are some important indicators of relative gender parity. In Aboriginal Australia, for example, property—the ownership of land and resources—is held in common by men and women alike, and all members of local clans have equal rights of access to these. Kinship lineages might be matrilineal or patrilineal, and formal marriage rules, such as a requirement for cross-cousin exchanges, entail a variety of marital arrangements in which a person of either gender might relocate to their spouse’s clan estate and kin. Aboriginal communities are gerontocratic in their political structures, being led by both male and female elders. Political status and power are conferred over time by the acquisition of secret sacred knowledge, often through key stages of initiation. Ritual practices, although also differentiated by gender roles, are carried out by both men and women to the extent that key ceremonies are typically categorized as ‘men’s business’ or ‘women’s business’.

The key point here is that in traditional place-based societies, such as those in Aboriginal Australia, substantial indicators of gender equality, including the rights of women to co-own land and resources, and to participate directly in democratic and equal decision-making, simultaneously promote egalitarian assumptions about the rights, and indeed the authority, of both male and female deities personifying aspects of the non-human world (

Strang 2005). Similar indicators of equality can be seen in other societies maintaining links with longstanding hunter-gatherer lifeways, such as Inuit communities in arctic regions (

Fienup-Riordan 2017), and the !Kung San in the Kalahari Desert areas of Africa (

Lee 1979), whose deities are similarly composed of both genders with complementary powers.

Critically, these societies compose convivial human-non-human relationships, to the extent of assuming that there is a human obligation to ensure the ongoing well-being of all living kinds, and a commensurate responsibility for the non-human world to care for humankind. Thus, many of the rituals I have recorded with indigenous groups in Cape York have focused both on expressing respect for local ancestral beings and soliciting their generosity in the provision of resources (

Figure 1).

Some societies, even as they settled and enlarged, retained a focus on nature religions. For example, cultural groups in Central America supported agriculture and increasing population levels with the introduction of irrigation (

Scarborough et al. 2011) but continued to worship deities of either (or combined) genders in the form of feathered serpents, water lily beings, jaguars, and so forth (

Ferguson 2000;

Walker and Lucero 2000). In the Pacific region, Māori groups settled into horticultural production, formed larger and more hierarchical tribes, but continued to valorise serpentine taniwhas, forest beings, sky beings, and other non-human male and female supernatural deities (

Barlow 1991). In parts of Asia indigenous communities also settled into agriculture, introduced increasingly sophisticated technologies, and enlarged but retained a keen sense of an animated and sentient non-human domain, as expressed, for example, in Japanese Shintoism (

Lee et al. 2018), in which water beings (in the form of dragons) traditionally appear as powerful supernatural beings. However, in such cases, the processes of transition described at the outset are visible. Following societal expansions, the Mayan cosmos shifted its focus to human or semi-human deities (

Diemel and Ruhnau 2000;

Schele and Miller 1986); Māori blended human and semi-human gods with their forest and water beings (

Barlow 1991); and across Asia, powerful dragon gods were displaced by deified human emperors (

Schafer 1980;

Strang, fothcoming;

Zhu 2014).

3. Expansive Trajectories

Other societies demonstrated more radical transformation in the trajectories of their relationships with the non-human world. Rather than maintaining sustainable lifeways, they embarked on modes of production that led to major increases in their populations and intensification in resource use. Jared Diamond describes agriculture as humankind’s worst mistake (

Diamond 1987), precisely because it sparked both of these trends, while also making increasingly instrumental changes to local environments involving land clearance, the drainage of wetlands, and the domestication and thus the prioritization of just a few plant and animal species. Enlarging societies produced more hierarchical social and political arrangements. Agriculture notably introduced greater gender inequality, both in gender roles (which became more closely aligned with public and private spaces) and through the more bounded enclosures of property that settlement required, which increasingly located land and resource ownership in male hands and lineages. Greater intensification and competition often led to appropriations and enclosures by more powerful groups, creating class structures dividing those holding land and resources from those who worked for them. Communities led by ‘big men’, ‘chiefs’ or privileged families transitioned, as their scale increased, to leadership by—most often male—religious leaders or monarchs whose primacy, along with technological developments requiring centralized governance, enabled the emergence of the nation state (

Engels [1984] 1972;

Hocart [1936] 1970).

Technological progression from agriculture to urbanization, along with the population increases permitted by these developments, sometimes led to societal ‘collapse’ as local environments ceased to be able to sustain commensurately high levels of resource use (

Diamond 2005). Societies that depended on irrigation to support such growth were particularly vulnerable: for example, in the Indus Valley, and in Central America, rapid expansions of early irrigation societies were brought to a juddering halt by long periods of drought (

Marris 2014;

Scarborough 1998, p. 135).

An alternative to collapse was to rely on resources traded from elsewhere or to seize the land and resources of others. Thus, for many centuries societies were able to maintain unsustainable lifeways by importing goods or by making hegemonic forays into other territories. Colonizing explorations and appropriations were largely led by men: they created multiple inequalities between conquerors and the conquered (the latter often being dispossessed of their homelands and/or enslaved) and, with the importation of more patriarchal ideologies, often encouraged more hierarchical relations between men and women. Thus, in African colonial history, for example, indigenous women previously holding relative gerontocratic parity in terms of property and political leadership (as queen mothers, chiefs, traders), found themselves doubly disempowered, losing their economic roles and being pushed into the structural social inequalities more familiar to the colonizers (

Meier zu Selhausen and Weisdorf 2016).

While acknowledging that this subsumes the real complexities of gender roles in earlier societies, it is fair to say that men more generally dominated the emergent spheres of engineering and infrastructure, and thus the process of exerting instrumental forms of control over the non-human world. Just as early technological advancements such as irrigation had permitted more intensive agricultural practices, so too did the invention of farming machinery, fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides, new industries, and new forms of energy and resource use. Just as colonial appropriation had introduced intercultural and gender inequalities, technological impositions enabling intensification in human resource use led to greater inequalities between humankind and the other species. Like indigenous human communities, non-human beings were either enslaved (by domestication) or displaced by the loss of their habitats, by the introduction of domestic crops and cattle, and by the environmental degradation caused by ‘infrastructural violence’ and exploitative practices (

Rodgers and O’Neill 2012).

Changes in religious beliefs and practices came hand in hand with all of these social, political, and economic transitions, most particularly with the preponderance of male religious leadership. The form ascribed to deities was therefore transformed over time. Early societies had worshipped and propitiated multiple deities representing the powers of the non-human world—serpentine water deities, storm gods, forest beings, totemic animal beings, and so forth (

Batto 1992;

Jastrow 1910, pp. 71–72). However, the gods of societies bent on growth-based trajectories underwent a process of humanization, first becoming semi-human (creating, for example, the serpent-tailed nāgas of Indian religions; the sea-serpent bodied, goat-footed or horned deities of early Greco-Roman and Celtic traditions) and then wholly human in form (as, for example, with the emergent Hindu gods (

Bolon 1992); and the later Greco-Roman pantheons (

Spretnak 1992). Within these religious pantheons, as societies became more patriarchal, formerly powerful goddesses were increasingly portrayed as either problematically unruly, or subservient to powerful male gods. The logical destination of this trajectory was reached when each of the major monotheisms placed all power in the hands of male/father deities (

Day 1985;

Reeves 2004;

Stavrokopoulou 2021).

4. The Emergence of the Other

The pattern of change in religious forms that asserted the rule of single male deities was, in accord with Durkheim’s thesis, concurrent with the establishment of patriarchal societies. This entailed some parallel processes of ‘othering’. Most obviously, it affected the status of women, who were recast as ‘Adam’s rib’ and infantilized by an overriding assumption of male authority (

Campbell 2001). The prevailing narrative tropes for women were disapproving of independence, self-expression, or failure to be socially (or sexually) compliant. Thus, an early Judeo-Christian figure of Lilith, who proved to be insufficiently biddable, came to be portrayed in a negative (jealous, vengeful) and sometimes serpentine form (

Riches 2005, p. 156), while—epitomized by the Virgin Mary—religious teaching valorised virginity, motherhood, nurturing, and obedience. The othering of women intensified in a medieval religious world that contained deep anxieties about ‘the flesh’. Women (if not virginal and virtuous) represented the temptations of the flesh and the potential corruption of the spirit, constituting a threat to social order that required authoritative containment (Galatians 5. 19–20). Misogyny was normalized to the extent that between 1580 and 1630 over 50,000 people, 80% of whom were older women, were tried and found guilty of witchcraft and burned at the stake (

Macfarlane 1999;

Pócs 1999).

A more subtle othering took place in relation to the non-human world. There was a critical process of spatio-temporal distancing: the non-human male and female deities who had previously lived in nearby rivers, wells, groves, and trees, rocks, and lakes, were simultaneously humanized and dislocated. Cosmological geographies began to place them elsewhere, for example in the lofty heights of Olympus. Thus, historians note the shifts from pre-Hellenic Bronze Age nature religions to the humanized Olympian pantheons of the Classical era (

Bonney 2011;

Henderson and Oakes [1963] 2020), with a related shift in the distributions of power in gender relations (

Gimbutas 2011;

Goettner-Abendroth 2009;

Spretnak 1992).

As concepts of time became more linear in form, deities also became more temporally distant, with their creative world-making seen as a long-ago era, and salvation located in a distant future (

Lippincott 1999). This spatio-temporal separation was further increased by transformations that absorbed all supernatural powers into an omniscient male God who shifted further upwards and outwards to dwell in a far-off celestial Heaven. Such spatialized relocation represented an important kind of ‘social distancing’, as it was accompanied by a sharper and more hierarchical conceptual division between humankind and the non-human ‘beasts of the field’ or ‘beasts of the forest’ (Isaiah 56:9).

Ancient religious texts present a particular view of historical contexts, offering a distillation of their dominant narratives and political arrangements. Like any system of law, they are reductive, obscuring historical and cultural variations and the contemporaneous complexities of gender and environmental relations (

Stavrokopoulou and Barton 2010). However, they do serve to highlight the dominant beliefs and practices that shaped the authoritative texts of the time. Thus, in ancient Biblical texts, monotheistic origin stories,

Genesis being the most obvious example, describe Man as having been created separately, in the image of God, with a clear gender division thrown in for good measure.

So, God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them. (Genesis 1:27)

In such accounts, only humankind receives the ‘breath of God’, i.e., the spirit, which confers immortality in that it returns to God upon death: ‘… and the dust returns to the earth as it was, and the spirit returns to God who gave it’ (Ecclesiastes 12:7). Only humankind is seen to have consciousness and the capacity for creative thought and communication with God through prayer. Although women might be permitted to pray, religious leadership became an exclusively male domain. Being located closer to the angels than to earthly life forms, ‘man’ (with the use of the masculine pronoun throughout) is given dominion over other living kinds:

Yet you have made him a little lower than the heavenly beings and crowned him with glory and honour.

You have given him dominion over the works of your hands;

You have put all things under his feet, all sheep and oxen, and also the beasts of the field,

the birds of the heavens, and the fish of the sea, whatever passes along the paths of the seas.

(Psalm 8.5)

Even the materiality of non-human beings is differentiated: ‘For not all flesh is the same, but there is one kind for humans, another for animals, another for birds, and another for fish’ (Corinthians 15:39).

It is through these authoritative religious narratives that the division between human and non-human, culture and nature became firmly established. There was an implicit continuum in which those humans, purportedly driven more by instinct and emotion and lacking rationality—i.e., women, ‘other’ races, or lower/uneducated classes—were deemed to be closer to nature. This further enabled racist divisions in which human ‘others’ could be seen as less than human and created the conditions for a dominant worldview in which all ‘others’ required elite, white male direction and control.

As dualistic visions of rational (male) culture, and irrational (female) nature took hold, there was a feminisation of nature that replicated expectations of gender (

Griffin [1978] 2015;

Plumwood 1993). In multiple impositions of the beliefs of major religions over those of conquered ‘pagans’, the non-human serpent beings that had manifested the elemental powers of water were demonised and slain (

Charlesworth 2010;

Riches 2005). Nature came to represent both the Holy Mother in all of her virtue or Lilith and Eve, the fallen women of the Bible. She might offer gendered compliance, with reliable and moderate water flows, rich soils to support crops, forests to supply timber, and valuable rocks and minerals to extract. Or she might be recalcitrant and unruly, withholding rain or sending it in overwhelming amounts, delivering hostile weather, offering impenetrable jungles and untraversable deserts, dangerous predators, and stinging or poisonous species. Such an ambivalent view of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ Nature implies that if there is more recalcitrance than compliance, ‘the other’ must be subjugated (

Condren 1989;

Merchant 1980,

2010).

5. Unequal Relations

This vision, therefore, reproduced several related forms of inequality. It lent itself to colonial endeavours that dispossessed many place-based communities of their homelands and led to the enslavement of perceptually ‘other’ and ‘lesser’ humans and their labour to serve white, male masters. It led to a broader subjugation of women, whose time and labour were similarly directed into service. It established a form of anthropocentric power relations in which the world was recast as being there to provide ‘environmental services’ for humankind, thus justifying the exploitation of the non-human world via the extractive and unsustainable modes of engagement that have led to the mass extinction of species that we are currently witnessing.

A modern vision of the non-human world as something to be ‘acted upon’ was not merely religious in its form. The scientific thinking that emerged in different times and places was also influential. Even as the major monotheisms became dominant, ancient Chinese, Greek, and Roman natural philosophers were seeking to understand the material properties of the world, asking questions about the elements, what they were, and why they behaved in certain ways; how human bodies worked, and how medicines might assist them; how celestial bodies related to each other and to human lives. This deconstructive thinking foreshadowed the disenchantment of Cartesian science, in which, rather than manifesting the powers of the non-human world in the form of colourful water serpent beings, water became H

2O and—along with everything else in the non-human domain—a ‘material resource’ (

Linton 2010,

2013). A vision of the world as being purely material intrinsically challenges ideas about animism and sentience in the non-human world, reserving consciousness and agency for dominant human elites. Such objectification is, of course, a prerequisite for exploitation, whether of women, non-human beings, or a disenchanted material world recast as a passive subject.

There are ample historical examples of how these beliefs and values are manifested in practice, but Australia, where a mere two centuries of colonial settlement has had such extreme social and ecological impacts, offers perhaps the most dramatic illustration of how quickly inter-human and inter-species inequalities can be established. Even the most preliminary colonial encounters, as European ships reached Australian shores, resulted in the killing and kidnapping of indigenous people (

Flannery 1999). In the subsequent waves of exploration and settlement, such practices were expanded to constitute genocide. Indigenous Australians could remain on their traditional lands by providing free labour to the cattle industry but were only legally provided with wages in the early 1960s. With the influence of civil rights movements around the world, they finally gained Australian citizenship in 1967. Since then, indigenous efforts to regain traditional lands and resources, and greater social and political parity, have been a long and uphill struggle.

As indigenous communities in Australia absorbed the patriarchal assumptions of European settlers, along with pressure to adopt Christian religious impositions, the colonial encounter was particularly degrading for women. Since colonising efforts were largely male-led, and there were few European women in the outback, settlement was accompanied by the ‘concubinage’ of Aboriginal women, which continued well into the 20th century. Gender inequality was entrenched by State policies ensuring women’s ‘statutory subjugation’, which enabled the removal of their children fathered by settlers. There was further political disenfranchisement as settlers, assuming that indigenous communities echoed the political arrangements of their own society, engaged in negotiations exclusively with Aboriginal men (

McGrath and Stevenson 1996, p. 37).

Australia similarly provides one of the starkest examples of how beliefs about anthropocentric dominion encourage exploitative environmental engagements. The introduction of hard-hoofed cattle to a continent with a delicate soil ecology; widespread land clearance, and the introduction of crop farming, was accompanied by violently asserted gold rushes and the development of extractive industries that established a heavily ‘resource based’ economy. All of these colonially introduced practices have had major ecological impacts, including widespread soil degradation and salination, and the severe pollution of waterways and marine areas. The introduction of multiple invasive species of non-native plants and animals has also been devastating to indigenous species, as has the rapid urban growth that, concentrated around river deltas, has removed many key wetland areas. Australia’s rapidly expanding coastal cities contain most of its national population, currently numbering about 25.5 million people. They also contain sizeable ports, enabling the movement of cattle and produce to nearby Asian trading partners, but involving dredging and construction that has been hugely disruptive to delta areas and to vital marine habitats.

Australia’s rapidly enlarged population also requires domestic water supplies and food. As its climate was characterised by highly volatile patterns of rainfall even before climate change exacerbated these, the response of governments and farming sectors has been to impose intensely directive water infrastructures. With a religious zeal for ‘greening the desert’, the early to mid-1900s saw the building of major dams and irrigation schemes (

Hill [1937] 1958), and this trend continued as the population increased further, and global markets exerted increasing pressure for more intensive farming practices. Thousands of bores were drilled to extract water from the Great Artesian Basin to provide for sheep and cattle, to the extent that its levels have fallen dramatically, and many people living around its periphery (particularly indigenous communities in the north) have found it increasingly difficult to access potable freshwater.

Food producers also invested in on-farm water retention schemes (small dams and bunds to ‘harvest’ water), and abstracted water from rivers to the extent that flows have regularly dropped to non-viable levels (

Connell 2007). In the Murray-Darling Basin, Australia’s major farming area, key wetlands have vanished, and millions of fish have died because low flows have led to eutrophication.

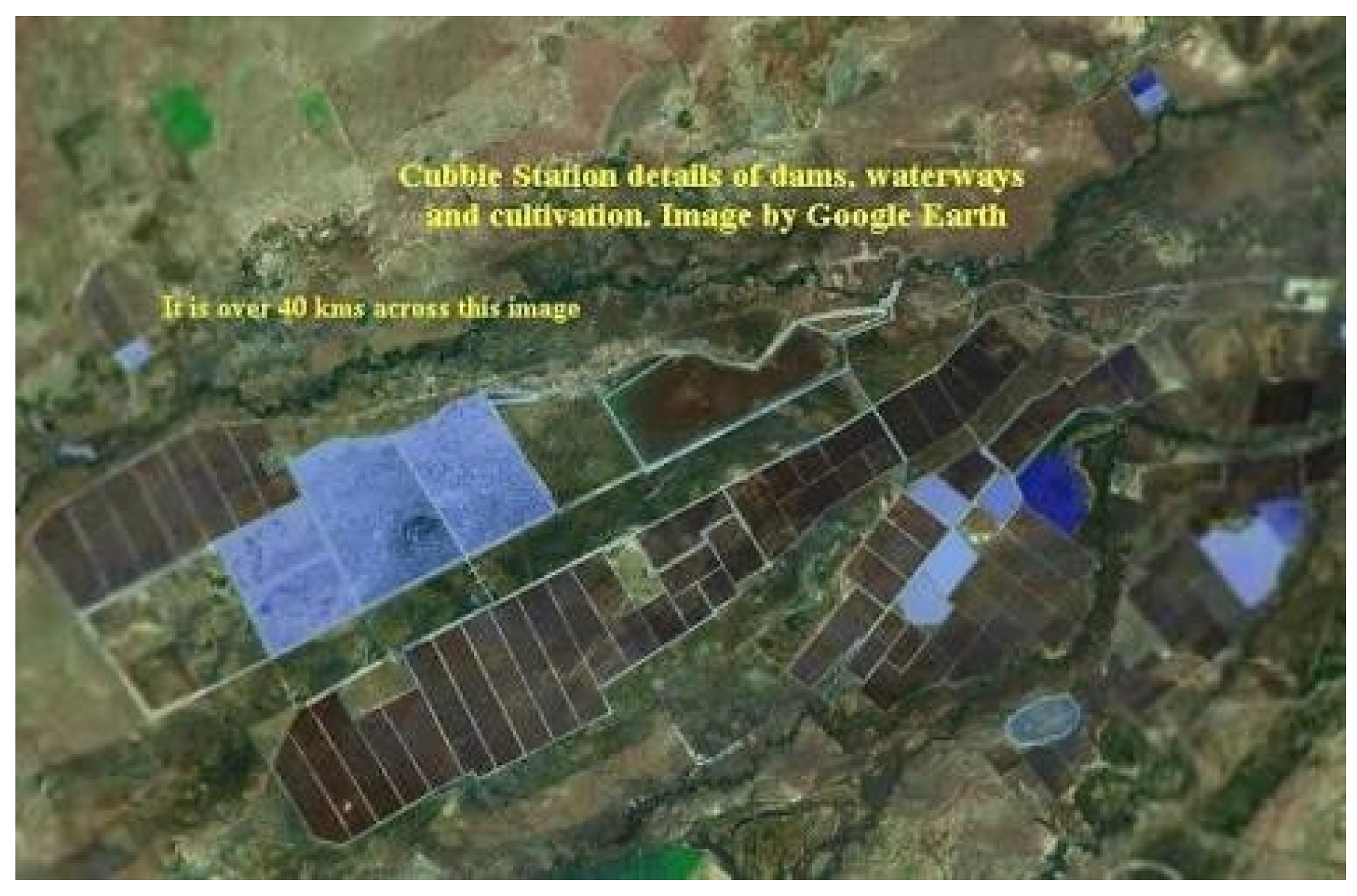

1 Additionally, located in the Murray-Darling Basin are vast irrigation corporations, such as the notorious Cubbie Station which, having bought over 50 abstraction licences with the acquiescence of the Queensland Government, built a series of dams large enough to be seen from space (

Figure 2). To grow thirsty and soil damaging (but highly profitable) crops such as cotton, the station annually abstracts from the river about a quarter of the water that would otherwise flow southwards into the Murray-Darling Basin (

Strang 2013).

6. Infrastructural Relations

The imposition of water bores, dams, irrigation channels, pipes, and related material interventions provides a perfect illustration of how societies choose to prioritize human needs and interests above those of non-human beings. All such concrete infrastructural arrangements are intended to direct water into serving human aims and activities, and thus away from its normal flows supporting ecosystems and their non-human inhabitants. As Ballestero observes, infrastructures also have a non-material dimension, in bureaucratic ‘devices’ such as indices linking water charges to consumption. (

Ballestero 2019).

In Australia, an important device of this kind has been the introduction of volumetric water allocations to commercial water users. Initially, these were aligned with riparian access and designed to set some limits, aiming to ensure the fair distribution of water to farmers along the course of each river. Efforts by conservation organizations to push for allocations ‘for the environment’, for example, to maintain wetlands and prevent fish kills, were largely met with debates about what constituted a ‘minimum flow’ sufficient to sustain aquatic ecosystems. However, Australia’s politics are more Conservative than conservative, and ecosystems such as the Murray-Darling Basin have continued to suffer. The situation was made more extreme in the 2000s, by the introduction of water trading. This new ‘device’ severed the tie between land and water, first by effectively privatizing water allocations that had previously merely constituted licenses to abstract specific amounts, and second by detaching them from the land so that they could be traded in a virtual water market, potentially leaving ‘dry blocks’ without any access to water.

In such a market, non-commercial organizations, such as conservation groups, can rarely compete financially with commercial players aiming to gain major profits by irrigating high-value crops. Nor can they compete politically in a system where powerful commercial interests dominate government agencies at every level. Wealthy landowners in Australia formed a ‘squattocracy’ in the colonial era, and these social networks remain powerfully influential. This firm hold on power is maintained, according to informants belonging to this group, because farming dynasties have established a tradition of ensuring that family members are elected to federal and state governments and that they also take a leading role in bodies focused on water management. A similar influence is exerted by the mining industry, as the ‘backbone of the economy’, and commercial fishers and the tourist industry are also important players. It is difficult for any non-commercial groups to challenge those able to stand on their contributions to the economy, and although conservation groups and indigenous communities strive to be heard, they are persistently marginalized, not least because they cannot afford to commit similar time and resources to being directly involved in governance.

The result is material and non-material infrastructures enabling highly exploitative practices that deprive non-human beings and ecosystems of the water that they need to sustain and reproduce themselves over time. There is now talk about ‘natural water infrastructures’ referring to aquifers, forests, or wetlands that capture and store water or regulate its flows. More often than not, these are seen as an opportunity to extend human control and access to resources by utilizing the material capacities of aquatic ecosystems, for example in storing water for irrigation, or ameliorating the effects of floods and droughts on human populations and urban areas (

Figure 3).

In this realm of thinking nature is still castas ‘the other’. This usefully brings home a realization that, while science has been conventionally represented as being opposed to religion, they share important common ground in a determination to separate culture and nature. Some efforts have been made to rejoin these domains. Studies of ecology have necessarily been concerned with anthropogenic pressures, and in recent decades there has been increasing recognition that cultural diversity and biodiversity depend upon each other. Efforts to establish Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) have sought to reconcile social and environmental concerns and to encourage interdisciplinary perspectives. But the emphasis has been on making connections between domains, rather than dissolving their boundaries.

This dualism also underpins environmental legislation that, echoing the disciplinary divides between the social and natural sciences, presents the non-human domain as a separate sphere of responsibility. It could be argued that environmental legislation does seek to promote and protect non-human interests and that its enactment, through bureaucratic processes, has some representational capacity to support non-human rights. However, because it remains largely dominated by visions of ‘natural resources’ as the passive subject of human decisions, it falls a long way short of providing the non-human domain with the kind of explicit rights and democratic equality that might genuinely challenge anthropocentric priorities.

In reality, most environmental legislation to date has done little more than ameliorate the most extreme effects of exploitative practices, and this is not enough to create a more sustainable trajectory for all living kinds. This is plainly illustrated in Australia, where multiple efforts to regulate water use have failed to protect the Murray-Darling Basin or indeed any of the continent’s ecosystems. The performative superficiality of much legislation purporting to uphold environmental well-being is reflected in the failure of almost all nations to achieve social and ecological sustainability, and in humankind’s collective failure to halt anthropogenically-caused climate change.

All such efforts are flawed in that they not only retain assumptions about separate natural and cultural domains, but also continue to employ the language of ownership (saving ‘our’ world), and concepts of guardianship that cast humankind hierarchically in a senior (male) parental role. In these terms, nature continues to be cast as a feminized, infantilized other, and non-human rights are only those doled out by Daddy.

7. Nature-Based Solutions

The newly fashionable notion of ‘nature-based solutions’ reaffirms dualistic visions of culture and nature and remains located within an anthropocentric view that the major objective is to utilize the material properties of the non-human world to maintain or improve its service to humankind. However, it also gives more room to an understanding that ecosystems have their own methods of regulating water flows, and that these constitute major agentive capacities. It is therefore a potentially useful point of connection between conventionally dualistic ideas about water and land management and critiques aiming to encourage a less anthropocentric stance, in which humankind seeks to understand and respect not just the powers of the non-human world, but also its needs and interests. In seeking a more egalitarian relationship, attempts to make a paradigmatic shift away from anthropocentricity challenge deeply embedded notions of human and male hierarchy and priority, as well as the dualism of a foundational concept that divides human and non-human beings into separate worlds.

As noted earlier, such dualism has long been challenged by alternate worldviews in which human and non-human beings inhabit a single world where their lifeways are not conceptually detached from one another but depend instead on a shared responsibility for collective human and non-human well-being. As indigenous communities have promoted their own beliefs and values with increasing vigour, often assisted by anthropological cultural translation, they have had a profound influence upon those groups in larger societies who seek both social and ecological justice. The close ties between early feminism and early environmentalism are often forgotten, but these movements have been hand-in-hand since the outset, underlining a reality that both are concerned with equality and critical of exploitative power relations. While civil rights movements seeking racial equality have emerged more independently, and there are multiple complex issues in their intersections with feminism and environmentalism, there is some conceptual common ground between all countermovements addressing inequality and injustice.

This coherence is most obviously the case with indigenous communities who seek not only to gain greater social equality but also to restore their traditional, more egalitarian relationships with the non-human world. In Australia, these aims are inseparable, with political enfranchisement providing the starting point for the long struggle towards regaining Native Title and an increasingly vocal critique of the exploitative practices that have devastated Aboriginal homelands (

Toussaint 2004). Similar endeavours can be seen around the world, for example in the USA where, at Standing Rock, Sioux tribes have protested against the imposition of oil pipelines on their land while also—like many other First Nation groups—seeking greater self-determination and a more influential role in protecting the environment.

Indigenous activism has also taken more reciprocal visions of partnership with the non-human world into the political arena. There has been a productive exchange of ideas between culturally diverse worldviews and academic debates similarly questioning the logic of dualistic visions of nature and culture. This has also brought into question the categories of ‘natural’ and ‘social’ science that reify a foundational worldview that these are separate domains. Academic critiques of the dualistic ‘othering’ of culture and nature have therefore come from several directions. ‘Scientific’ visions of the interdependence of all organic beings and ecosystems include Vernadsky’s notion of a holistic ‘biosphere’, conceived in the 1920s (

Vernadsky [1929] 1986), which provided a starting point for the notion of Gaia promoted by James

Lovelock (

2000), although in presenting humankind as the brains of the planet, this failed to reject the established hierarchical arrangements.

Indigenous ontologies, fully acknowledging the participation of the non-human domain in co-creating shared lifeways with humankind, have inspired many of the ideas underpinning social science theories concerned with relationality. For example, a more egalitarian vision of a single human-non-human world, conceptualized in fluid relational terms, is provided by Socio-Technical Systems thinking (STS) (

Harvey et al. 2019), and other work on complex systems (

Marres 2012;

Savaget et al. 2019), and by Actor Network Theory (ANT), in which Latour promotes a notion of governing without mastery (

Latour 2004,

2005). New materialism has brought with it a keen sense of the agentive capacities of non-human beings and things (

Coole and Frost 2010), and the communicative capacities of ecosystems (

Tsing 2004), as well as the ways in which non-human elements act upon the world through their material properties and behaviours (

Edgeworth 2011;

Strang 2014).

Greater appreciation of non-human powers has also revived a lively debate about animism and agency (

Harvey 2005). These terms have excited some controversy, partly because they raise both religious and scientific hackles about definitions of consciousness and intentionality, and where and how these might be located. Acknowledging forms of agency and consciousness in non-human beings constitutes a direct challenge to the most dominant religious beliefs: that spiritual consciousness is what differentiates humankind from ‘the beasts of the field’. Similarly, ideas about ‘vital’ materialism (

Bennett 2009) unsettle the certainties of a disenchanted Cartesian view of a materially passive world.

Animism has traditionally been defined as a belief that plants, animals, places, and things are enlivened by a spiritual essence or soul (

Bird-David 1999). This sits readily with belief systems in which non-human beings, water, and places can be personified as non-human deities, such as the Rainbow Serpent, which generates life and imparts spiritual ‘aliveness’ to other beings and to sentient living land and waterscapes. However, metaphorical narratives of spiritual being and presence are not so far removed from more secular ideas about what is ‘alive’. While Cartesian visions of materiality fail to encompass ideas that specific places, rocks, waterways, and so forth might also be ‘alive’, and may categorize both indigenous beliefs and neo-paganism as ‘animism’, when such concepts are expressed through more abstract ecological views of ecosystems as ‘living systems’ they are not really so controversial.

This takes us into some wider questions about personhood, and the extent to which this is understood as depending on some kind of soul or spiritual essence. While monotheistic religions generally take the view that only humans have souls, this is leavened, to some degree, by their retention of a more generalized notion of spiritual consciousness (albeit located in a male father deity) that is ‘omnipresent’. The concept of ‘presence’ is helpful. It highlights the metaphorical similarity between Judeo-Christian ideas about an ever-present God watching and judging human lives, and more definitively ‘animistic’ beliefs, such as Aboriginal visions of a sentient cultural landscape imbued with ancestral beings that are similarly watching over its inhabitants and generating the laws and moral order by which they are meant to live. Another conceptual link might readily be made with emerging ideas from the cognitive sciences, about notions of extended mind (

Clark 2008).

Without wishing to revisit lengthy and impassioned arguments about agency, it may be that these can be defused, to some extent, by an acceptance that there are multiple forms of consciousness and intentionality, most of which do not match the extreme reflexivity that human cognitive capacities allow. Other species demonstrably share some aspects of consciousness, such as complex social interactions and emotive responses to stimuli, and even plants seeking the light, or viruses colonizing other bodies, demonstrate forms of intentionality. Thus, consciousness might be best conceived as a continuum of diverse possibilities. Our closest primate relatives hint at some shared capacities for reflexive understanding, but humans—the cleverest monkeys—are still the extreme outliers. However, while perhaps located at the other end of the continuum, even material things, such as water, have considerable capacity to act upon the world and all of its living kinds, and to ‘behave’ in predictable ways as a result of their particular material properties (

Strang 2014).

Anthropological studies of human-animal relations (

Serpell 1996) have shown that most societies acknowledge non-human beings as persons, with domestic pets being most readily included as kin within families. Recent multi-species ethnographies have also considered the complex social and material interactions between other species and between human and non-human beings (

Haraway 2008;

Kirksey and Helmreich 2010). Material culture specialists have shown how objects can be imbued with notions of personhood (

Knappett and Malafouris 2008) and the idea that sacred objects, places, rivers, and so forth can personify supernatural deities is unproblematic in many cultural contexts.

Societies that see non-human species and elements as totemic ancestral beings are naturally more comfortable with wider concepts of personhood. A useful example is provided by recent Māori activism in New Zealand, which has succeeded in persuading the courts to define forests and rivers as ‘living ancestors’ (

Muru-Lanning 2016). This has led to a decision to confer legal personhood on, for example, the Whanganui River, providing it with the rights and responsibilities of persons equivalent to that offered to bodies such as corporations. Similar efforts have been made to declare rivers as persons with the Ganges, and with the Atrato River in Colombia. Such rulings have been controversial internationally precisely because they transgress both Christian beliefs and established scientific beliefs, about spiritual being, or consciousness, being confined to human persons. In doing so, they open the door to an assertion of non-human rights.

8. Conclusions

Activists around the world have called for the UN to issue a declaration of the ‘rights for nature’. As with the universal UN Human Rights established in 1948, this would confer upon non-human species some basic rights to survive and be protected from extinction; to reproduce; to live safely and without mistreatment. In a complementary effort, legal activists have been pushing the International Court of Criminal Justice to include ecocide—the destruction of ecosystems, and the driving of non-human species to extinction—as an international crime (

Higgins 2019).

Although these endeavours retain some problematic vestigial assumptions about a separate domain of ‘nature’, they are symbolically important, opening the door to the new thinking that, in envisaging a dynamic interrelated world, challenges anthropocentric assumptions that separate humankind from ‘nature’. Relational models, like those of more holistically integrated cultural contexts, foreground the agentive capacities of non-human beings and things and strengthen their active ‘presence’ in events. This vision of collective participation provides more promising conceptual foundations for sustainable human-non-human relations. However, the achievement of sustainability surely depends upon some form of pan-species democracy that, unlike more conventional notions of ‘stewardship’ or ‘guardianship’, advocates more equal relationships between human and non-human beings (

Grusin 2015;

Hinchliffe et al. 2005).

It is usual to assume that democracy requires a capacity to participate explicitly in decision-making processes. Although animal behaviouralists and certainly many pet owners might argue that ‘dumb animals’ have considerable communicative ability, there are obvious limits to the capacities of most species to represent their own needs and interests. Humans also vary radically in their abilities to articulate their needs and interests, and a parallel problem is presented by the lack of capacities of small children to speak for themselves. Models for upholding children’s rights assume that they do have human rights and that we have a collective social responsibility for protecting these rights by speaking on their behalf. In deliberative ecological democracy, non-human democratic rights are similarly upheld by the provision of effective representation of ‘those who can’t speak’ (

Eckersley 2000, p. 119).

Speaking for ‘the other’ has some practical application in discursive fora (

Meijer 2019), but it is not a complete solution. As Barad has observed (

Barad 2007), it is difficult to maintain ontological equality between those who cannot speak and those representing their interests. Pan-species democracy requires a paradigmatic shift: an understanding that democratic participation is not merely about being ‘spoken for’. Non-human beings and the material world—and water is a prime example—are intimately involved in flows of material exchange with human beings, and with each other (

Alaimo 2010;

Dobson 2010). Thus, they are not passive subjects awaiting human voices to speak for them and represent their interests: they are social and material agents in themselves—co-participants in the production of land and waterscapes, and in the making of human and non-human lifeworlds (

Hinchliffe 2015;

Neimanis 2017). Recognizing this active co-production is a vital step towards accepting the case for non-human rights and democratic inclusion.

Once non-human rights are agreed, the question then is how to ensure that they are democratically upheld and carried into everyday practices. For interspecies political relationships that respect non-human agency, we can return to indigenous exemplars demonstrating more reciprocal ways of engaging with the non-human world. As described above, in Aboriginal Australia, non-human beings, and the non-human domain are readily acknowledged as having agency and power (

Muecke 2007). The immediate presence of authoritative non-human ancestral beings permeates all decision-making processes, such that conserving resources and protecting future generations (human and non-human) is integral to indigenous models of ‘caring for country’.

In larger societies, we need more explicit mechanisms that ensure that non-human needs and interests are voiced in the composing and enactment of laws, and in decision-making processes. How, in practical terms, can non-human beings and ecosystems be included in pan-species democratic processes to the extent that their rights are properly represented and balanced in relation to the fulfilment of human needs and interests? How is it possible to achieve an ethical and sustainable balance in the distribution of costs and benefits?

A useful representational model is provided by New Zealand’s bi-cultural decision to extend rights to forests and rivers. The case of the Whanganui River led to the formal establishment of a role in which members of the local

iwi (tribe), who regard the river as their living ancestor (

Te Awa Tupua) are elected to represent and ‘speak for’ the river in all decision-making and legal fora. An appropriate gender balance in this role was also achieved, in the first instance, by the election of a woman and a man with appropriate expertise and experience to carry a joint responsibility for representing the rights of the river (

Strang 2020).

Building on this model, I have proposed elsewhere a concept of ‘re-imagined communities’ in which the idea of imagined communities (

Anderson 1991) is extended to include the non-human domain (

Strang 2017). This wider inclusive vision provides a non-anthropocentric starting point that relocates humankind within the world and extends notions of equality and democracy to all living kinds. Thus, in river catchment management, rather than decisions being dominated by commercial or political interests, both human and non-human rights and interests would be democratically represented by a diverse group of people with appropriate expertise (social scientists, biologists, geologists, botanists, etc.) who would not have a direct conflict of interest in the outcomes.

There is no single formula as to how this might be arranged: various permutations—councils of elders, catchment expert groups—could be appropriate in different social and cultural contexts. However, there are some key ingredients. These representatives would have a clear appreciation of the role and agency of the non-human domain in co-creating a shared lifeworld. They would provide diverse expertise about a strong cross-section of non-human species, and about the material world—the soils, the hydrology, and the geology—within the river catchment area. They would have a remit to articulate non-human needs and interests in decision-making processes, and they would seek outcomes achieving a sustainable balance of human and non-human rights and interests. This suggests that all representatives—speaking for human and non-human participants—should have some parity in the process and that the composition of such groups should also be founded on principles of equality and diversity, most particularly with a remit to strengthen the inclusion of women in leadership and decision-making.

An approach underpinned by principles of parity and partnership has implications both for gender relations and for human-non-human relations. It has Durkheimian implications for the religious and secular belief systems underpinning social action. It must be hoped that, with gender parity, with a non-anthropocentric worldview, and with robust pan-species democratic representation of ‘other’ living kinds, it will be possible to achieve more sustainable modes of human-non-human engagement.