1. Introduction

Religious itineraries and routes can be considered a reason for sharing ethical-religious values and feelings of peace and brotherhood but also an opportunity for the traveller to enjoy a spiritual and cultural experience. Those who practise religious tourism today are driven, as Monsignor Mazza points out, by “a desire for spirituality in response to the nausea of emptiness and bewilderment generated by the technological society” (

Mazza 2009, p. 592). They wish to experience the fascination of retracing ancient pilgrimage routes, fulfilling an emotional and intellectual need for authenticity, spirituality and culture. Indeed, as

Mambretti (

2014) recounts in her journey to Santiago de Compostela, the tourist travels with the aim of “seeing” something, while the pilgrim travels with the aim of “seeking” something, an experience, an opportunity to learn about both themselves and the territory visited. Clearly, understood in this way, even the use of the term “pilgrim” is obsolete (

Badone and Roseman 2004;

Gladstone 2005;

Digance 2006;

Timothy and Olsen 2006;

Collins-Kreiner 2010;

Gitlitz 2014;

Carbone et al. 2016). It is inconsistent with the new figure of the traveller who follows a route practised by ancient pilgrims but is also interested in the landscape, the deep and sincere perception of different communities and their cultural heritage, understood as a legacy that is key to the location’s identity (

Niglio 2014). This contribution focuses on the Via Francigena del Sud, in southern Italy, that enriches the historical-cultural itinerary, approved by the Council of Europe in 1994. Crossing different regions, the itinerary highlights the rich diversity of the contributions to cultural heritage and plays an important role in promoting dialogue, which, for the Council of Europe, is a potential tool for intercultural cooperation and an opportunity to consolidate the feeling of identity (

Berti 2012,

2013). Indeed, the itinerary makes it possible to identify and bring together “cultural, religious and humanist values, which are the roots of Europe, giving content to its memory and meaning to its identity” (

Bettin Lattes 2010, p. 38). European cultural heritage, with its various contradictions and plurality of dimensions, represents, as Bettin Lattes reiterates, an “extraordinary wealth” from which European identity can still draw “precious nourishment” (

Bettin Lattes 2010, p. 3). The literature on the value of cultural routes (see, for example,

Majdoub 2010;

Bruschi 2012;

Zabbini 2012;

Beltramo 2013;

Berti 2012,

2013;

Trono 2014;

Council of Europe 2015;

Pattanaro and Pistocchi 2016;

Trono 2017) and on the character of religious ones (among others, see:

Rizzo and Trono 2012;

Rizzo et al. 2013;

Rizzello and Trono 2013;

De Salvo 2015;

Trono 2017;

Trono and Oliva,

2017;

Trono and Olsen 2018) is considerable and growing.

Like pilgrimages, cultural routes and itineraries, with regard to their research aspects as opposed to the simple visit, are closely linked to the theme of authenticity and its various interpretations. The value of authenticity may be studied in accordance with several disciplinary approaches, whose focus ranges from the location to the individual. The historical-objective approach attributes value to the originality of the site or artefact; the sociological-constructivist approach links authenticity to the symbolic meaning associated with the culture of the user; disregarding the site, the existentialist approach searches for it in the state of mind of the subject (

Wang 1999). None of these approaches in themselves seem to be exhaustive. Indeed, while on an economic level (understood as the satisfaction of a need) the originality of the place is certainly important, we should neglect neither the culture of the walkers nor the stratification of meanings of the places that they are already partly familiar with and discover as they pass through, establishing individual and collective relationships with the contexts (

Belhassen et al. 2008). The place, therefore, cannot be seen as merely the container of what is original and has been preserved: on the contrary, as with the concept of landscape, it represents the complex and changing synthesis of temporal reality (events, transformations, interests), civilisation and social life (

Bronzini 1984, p. 202). Within this complexity, the traveller is transformed from user into actor (

Bachimon et al. 2016;

Tuan 2010). The location, the randomness of events (actions in a defined time) and the subjective components (culture and beliefs) of the walker(s) ultimately combine to determine authenticity as an integration of context, meaning and experience.

At a local level, cultural and/or religious routes represent good opportunities for the transformation of natural and cultural resources and sacred places into heritage and assets. In this context, the route is the unifying thread that creates a new system of knowledge and enables the promotion of little-known places, especially inland or marginal areas that have considerable tourism potential (

Meyer 2004;

Briedenhann and Wickens 2004;

Trono 2009;

Quattrone 2012;

Conti et al. 2015). These aims are shared by many national and regional governments, including that of Puglia, which sees the Francigena del Sud, a continuation of the European Francigena itinerary towards the Holy Land, as an opportunity for regional promotion. Together with the widely investigated Michaelian and Marian themes (

Calò Mariani 2019;

Calò Mariani and Pepe 2013), it could also provide a boost for other little-known paths that replicate the journeys of popular saints such as St. Peter the Apostle and St. Francis of Assisi from Jerusalem to Rome.

After a brief analysis of the paths of St. Peter the Apostle and St. Francis of Assisi, this paper presents the Southern Via Francigena and the characteristics that distinguish the new walker from the ancient anonymous pilgrim of Bordeaux, who, in 333 AD, on the way back from Jerusalem, decided to cross the Strait of Otranto and disembark in Puglia. Throughout the Middle Ages, the ports of Puglia were the preferred embarkation points for pilgrims heading to the Holy Land, at that time controlled by the Outremer kingdoms. On this topic, the sources are numerous and eloquent. Writing of Bohemond of Hauteville’s preparations for his departure for the Crusades, Robert the Monk states that the Franks arriving in Puglia embarked from Bari, Brindisi and Otranto. A few years later, the Anglo-Saxon merchant Saewulf, who was headed to Jerusalem, mentioned the ports of Bari, Barletta, Trani, Siponto and Otranto, the latter held to be the last useful port for crossing the Adriatic. An anonymous pilgrim recalled setting off from Brindisi for the Holy Land in the late 12th or early 13th century, and the same port is cited among those used by the crusaders following Richard the Lionheart. In the Crónica Catalana by Ramon Muntaner, Brindisi is described as the best port in the world, situated in a fertile and productive region not too far from Rome. Vessels sailed from this Adriatic port carrying goods and pilgrims to Acre, organised especially by the Knights Templar and Knights Hospitaller. In the mid-12th century, the monk Nikulas Bergsson conducted an extraordinary journey from his native Iceland to Brindisi, from where the future abbot of Munkathvera embarked for Acre, which he reached after 14 days sailing.

The ports of Puglia, which had served the pilgrims at the time of the Crusades, became mere ports of call on this longer route, as did those of Dalmatia, Corfu and the Peloponnese (Methoni, Koroni, etc.), which the Venetians called Morea. Further stopping places included Chania on the island of Crete, Rhodes, Cyprus and finally Jaffa and Jerusalem. Numerous European travellers (Flemings, French, Italians, Germans, English) followed this route on their outward or return journeys. An interesting and highly complex itinerary was followed by two Flemish notables, John and Anselm Adorno, who set off for the Holy Land from Bruges in 1470. Anselm wrote a fascinating account of the journey, providing vivid images of their stopping-off points in the Mediterranean. The images of the ports of Puglia, the Aegean islands and Jerusalem were also evoked in their town of origin, Bruges, which is home to one of the most famous replicas of the Holy Sepulchre ever built (

Stopani 1992;

Davidson and Dunn 1993;

Cardini 2008;

Leo Imperiale 2012;

Federico 2014;

Trono and Leo Imperiale 2018).

This study analyses in detail the features of the route that runs along the eastern side of Puglia. This region forms the most eastern part of the Italian mainland, jutting out between the Adriatic and the Ionian seas towards Albania and Greece, thus forming a “bridge” between Europe and the countries of the eastern Mediterranean. The territory of the region is geographically attractive to human settlement, combining the hilly areas with the extensive and rich plains, which dominate the region. Puglia is a land with a complex history, whose roots go back to the Homeric rural idyll, the great pagan mystery of the Acropolis, the Mediterranean traffic of the Phoenicians, the Greek colonies known as Magna Grecia, the Romans and the control of Greek Byzantium, which left its mark on the local culture, crypts and underground churches, not to mention the voyages of the Crusaders, the multiform historical experience of central Europe and the conflicts with the Ottoman Empire, the empire of Frederick II of Swabia, who loved this land and gave it monuments of inestimable value (

Baldacci 1972;

Novembre 1979;

Trono 2003). Today, the region is still a destination for walkers who retrace the ancient pilgrimage routes but also for new travellers who cross the Mediterranean and head for Rome or other regions of Europe, no longer for reasons of faith but in the (frequently unfulfilled) expectation that Europe can ensure the well-being, peace and respect for human rights denied to them in their homeland.

2. Ancient Religious Itineraries

2.1. St. Peter the Apostle

The establishment of a religious-cultural itinerary that traces the transit of St. Peter the Apostle across the Italian peninsula has already been the subject of many studies, which are summarised and integrated in this section (

Oliva 2015;

Trono and Oliva 2017).

Peter of Bethsaida is a key figure for understanding the evolution of the Christian religion. The official Christian sources from which the Saint’s life may be reconstructed are the Gospels, the Acts of the Apostles and the Epistles. However, these contain only fragmentary data from which it is possible to draw little information about the places where the Saint conducted his evangelising work (

Donati 2000).

Historically, all the texts dealing with Peter are classified as Acta Petri in the Corpus Christianorum (

Geerard 1992, pp. 190–209). In the sources, as well as in the posthumous tradition, his journey towards the centre of Roman power unfolds through his preaching in the most important cities. In those places, where some inhabitants had probably already come into contact with the nascent religion, his presence served to introduce the apostolic version of the new faith and its liturgy (

Trono and Oliva 2017).

We have no contemporary sources, since the oldest start from the second century AD. (Hegesippus, 110–180; Clement of Alexandria, 150–215; Arnobius, 255–327; Eusebius of Caesarea, 265–340; Cyril of Jerusalem, 313–386; St. Ambrose, 339–397). The list of these sources expands considerably if we include the founding myths of many Italian dioceses (

Lanzoni 1927).

Written and archaeological sources agree on the fact that St. Peter arrived in Rome and that he spent the last twenty years of his life there before his martyrdom and burial (

Gnilka 2003;

Guarducci 1989). Many southern cities, particularly in Puglia, traditionally claim that he passed through them on his journey across the Italian peninsula to Rome, including Siponto, Venosa, Lucera, Canosa, Ruvo, Bari, Oria, Otranto, Galatina, S. Maria di Leuca, Gallipoli, Taranto and San Pietro in Bevagna (Manduria).

Regarding the identification of paths, in accordance with the constructivist approach, myths and legends are considered to be embedded in the territory, regardless of their actual relationship with real characters or documentable facts. These traditions are often associated with specific locations, forming a “mythical landscape”, which generally has its own organic coherence. The landscape of myth blends with the real landscape of complexity. In some cases, legendary traditions of millenary reach no longer have any link with the current state of the places. In other cases, the landscape of myth adapts and changes with the transformation of the real landscape (

Santangeli Valenzani 2012, p. 99).

The traditions relating to Peter’s journey, even those that appear historically spurious, play a significant role in the light of certain cultural and geographical interpretations. The first concerns the documented presence of large Jewish communities in some of the settlements he is said to have passed through. Analysis of the New Testament apocrypha leaves little doubt about the primary role played by the Apostle in the Judeo-Christian context of the first evangelisations, in contrast with the figure of Saint Paul. Another interpretation concerns the episcopal primacy claimed by cities that had a prominent position during the late Roman imperial phase and late antiquity. For these dioceses, the Petrine tradition links them directly to the successor of Christ. Furthermore, it is important to keep in mind that the cult of the Saint has had a special value for the Roman Catholic Church since the late Middle Ages, especially in those regions affected for a long time by the spread of Orthodox Christianity or heretical movements in various periods (e.g., Lombard Arians, Poor Hermits and Little Friars, as well as schismatics). This seems to be a consolidated theme in current historiography, despite the important role that the figure of Peter played in the Christian Orthodox Church and despite the numerous late ancient and early medieval dedications referring to the Apostle in the Greek-speaking world. Further reasons for the spread of these traditions can be found in the role played by Peter “the fisherman” in the protection of sailors and seafarers. Finally, it is worth mentioning the singular material manifestations of the cult of Peter in connection with the presence of spring waters and protection against drought.

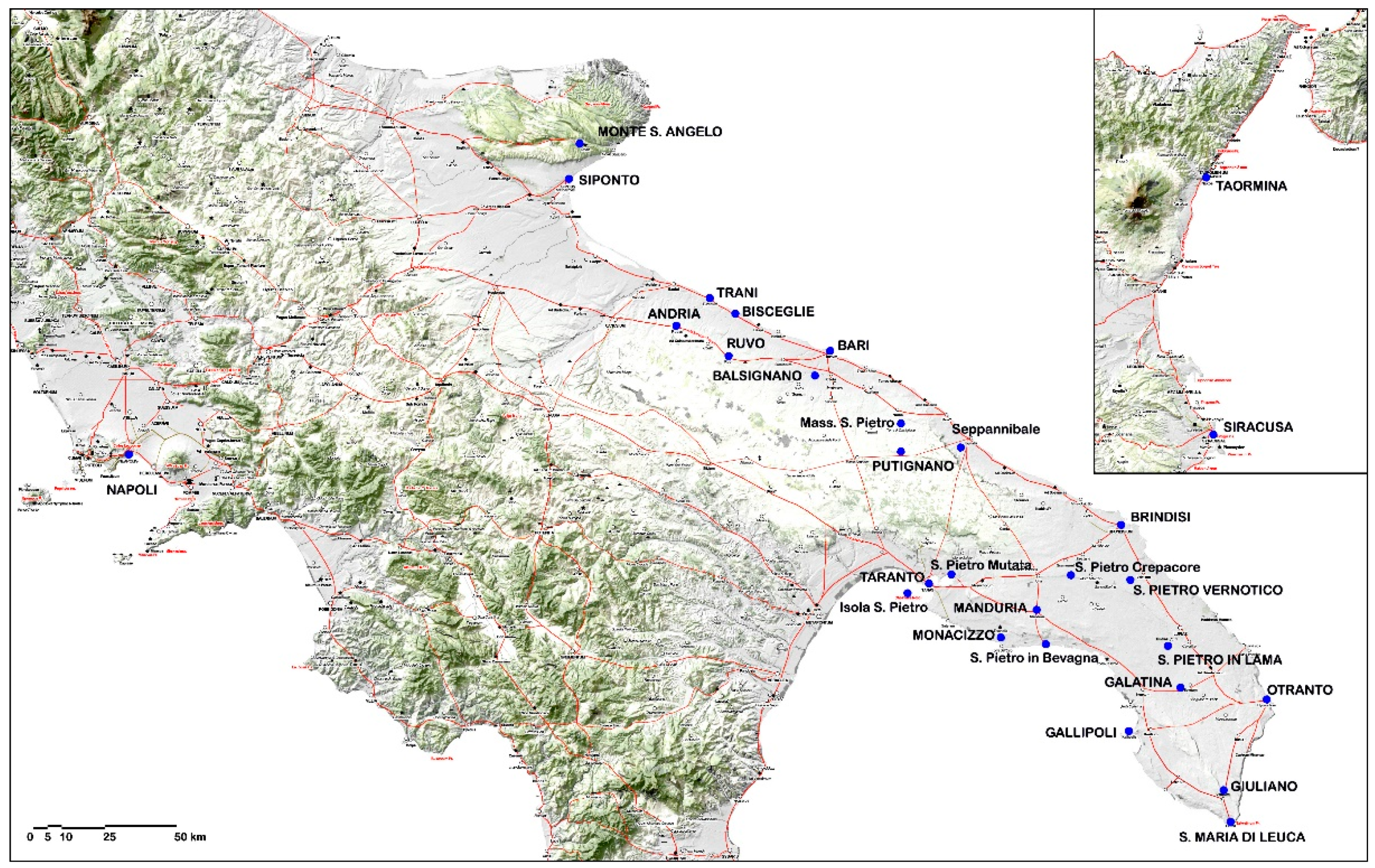

Aiming at greater involvement of users, the constructivist model needs to be integrated with references to the perceptual and experiential dimension. To this end, we selected sites that in various ways recall Peter’s physical presence. The selection criteria imply that these places currently exist and are geographically contiguous with each other, in order to establish possible itineraries (

Figure 1). Furthermore, we distinguished two possible approaches to the sites: a navigable coastal itinerary that recalls the theme of the Saint’s landing in the peninsula through coastal navigation and an inner land itinerary that shares most of its route with the existing network of regional cultural routes (

Figure 2).

The following cases, relating to two provincial capitals, Brindisi and Bari, exemplify the research method adopted in the case of sites and relics that bear the signs of contact with the first pontiff. In all cases, current knowledge is based on the echoes of remote oral sources or accounts handed down by modern documentation. Recently, possible new archaeological evidence has helped to extend the circumstantial framework.

The oldest source attesting to the apostolic evangelisation of the city of Brindisi is a passage by Paul the Deacon which dates to the eighth century AD (

Paolus Diaconus 1829, p. 261) and attributes the foundation of the city’s first Christian community to Leucius, a disciple sent directly by Peter after he had settled permanently in Rome. The places and relics of Leucius are therefore linked to the memory of the Petrine authority, which has been handed down in the local memory. In the tradition of faith, therefore, when Leucius fulfils the mission entrusted to him by Peter, he embodies and represents the consideration in which the Apostle held the city of Brindisi. We do not know whether this mission reflected the importance of the city for Christianity or the Saint’s own experience of the place, having passed through it on his way to Rome.

For the city of Bari, however, the first document affirming the local tradition dates only to the 18th century (

Selvaggio 1779, tome I, chp. 6, par. 3, pp. 44–45). This source reports an episode that in other versions took place in the city of Taranto: after the landing of the Apostle, he was secretly housed in a cave, in which he baptised and ordained the city’s first bishop (

Oliva 2015, pp. 179–80). In Bari, the cave is commonly located in the old town, below the complex of San Pietro Maggiore, attested in 1119. This place was later incorporated into the convent of San Pietro delle Fosse, built by the Observant Friars Minor, which took its name from it in the 16th century. During some excavations in 1910, what was believed to be the original cave was discovered. It was photographed by the Archaeological Museum of Bari and published in a city guide (

Colavecchio 1910, p. 110;

Dell’Aquila and Carofiglio 1985, pp. 123–26). The convent was heavily damaged during the Napoleonic occupation and was later definitively demolished in the 1960s. Some recent excavations have revealed some of its remains and made them accessible (

Ciminale et al. 2015).

2.2. St. Francis of Assisi

The myth of the voyage of St. Peter shows singular analogies with that of the voyages of St. Francis of Assisi: the former as the founder of dioceses, the latter as the founder of convents (

Giannone 1770, book XIX, chp. V, p. 333). This relationship can also be extended to the development of a variegated range of local manifestations of veneration and epiphanic references.

The methodology of research followed in both cases is similar, giving high importance to the landscape of myth as a way to re-semantize the geographical context with a discriminating approach that could bring the users closer to the historical dimension of the saints.

A “Way of Francesco” (

www.viadifrancesco.it, accessed on 23 November 2021) has already been established and set up in the historical footsteps of the Saint between Assisi and the sanctuary of La Verna, proceeding to Rome.

Regarding the documentary sources on the establishment of convents, the Series Provinciarum (from 1262 onwards), the Statistics of 1282 (

Golubovich 1913, vol. II, pp. 241–58) and Il Provinciale of Fra Paolino da Venezia of 1334 (

Eubel [1892] 2011) all show fewer foundations in Southern Italy than the rest of the peninsula. The disputes between the Swabian imperial dynasty and the friars are the most historically accepted reason for this difference, but recent historiography has shown that in the Kingdom of Naples, especially in the larger towns, there was a balanced presence of various orders at least until the early decades of the 14th century (

Serpico 2002;

Pellegrini 2010).

The most ancient and official biographical sources show a progressive mythicisation and institutionalisation of the figure of Francis, starting with the so-called Vita prima by Tommaso da Celano of1228 (

Intagliata 2020) and continuing with the Legenda antiqua, the Vita secunda, the Tractatus de miraculis and the Legenda Maior by Bonaventura da Bagnoregio. In contrast, the biographies written by the early “socii” (the term used to define the first members of the nascent Franciscan community) bring out the Saint’s anti-official and jocular aspects (

Bronzini 1984, p. 222;

Frugoni 1995). They include the De inceptione et actibus illorum fratrum minorum qui fuerunt primo ordinis et socii b. Francisci by friar Giovanni da Perugia, the Legenda trium sociorum and the later Actus beati Francisci et sociorum eius. These writings describe places and regions as the background to episodes in the life of the Saint, linking them to his preaching, his pilgrimages, his meetings at the Holy See and the management of his growing order.

Regardless of both the historical question of authenticity and the anthropological dimension of legends, the creation of one or more geo-devotional itineraries that retrace the places where the myth of Francis is preserved cannot ignore the correlation between the tangibility of this myth today and the late medieval infrastructural context.

The itineraries thus determined combine elements of interest and historical geography with the approach to the life of Francis himself and his posthumous veneration. On the devotional level, the proposals seek to correlate those places that preserve or project a dimension that evokes the founder’s original precepts (although sometimes it may also dilute them).

The Memorabilia Minoritica by Bonaventura da Fasano and the Cronica by Bonaventura da Lama cite many sites in the early Province of St. Nicholas, mainly corresponding to the actual Puglia. In these texts, we read of the presence of St. Francis at the extra-urban site of S. Maria del Casale near Brindisi, where (despite his love of animals) he cursed the spiders for their webs that covered an ancient Marian icon in a chapel dedicated to the Ascension (

da Lama 1724, pp. 8–10). The popular topos of the water source is re-proposed in the city of Oria, where the Saint created an inexhaustible source of water to quench the thirst of monks and pilgrims visiting the “Madonna di Costantinopoli” and “Madonna delle Grazie”. Later the use of that water was extended to the whole city (

da Fasano 1656). In Taranto, St. Francis established the new Franciscan community in the church dedicated to San Lorenzo, which he consecrated (

Merodio [1682] 1988, pp. 279–85). In the Trattato dei miracoli of 1252–1253 (

da Celano 2015), Tommaso da Celano tells of a deceased girl who was resurrected by the Saint in the town of Pomarico. Other miracles, evoked by prayers and dreams, are attributed to St. Francis even after his death. Marco da Lisbona in 1680 locates the miracle of the storm narrated by Tommaso da Celano in the city of Barletta. In the town of Celano, north of Puglia, St. Francis saves a boy who has fallen into a well. In Potenza, a cleric who doubted the presence of the stigmata on the hands of the Saint finds them on his own hands until he repents.

In addition to these episodes, the cult of St. Michael and the sanctuary dedicated to him on Gargano should not be overlooked, although there are no contemporary texts that mention a real pilgrimage to that place. In the Vita Seconda di San Francesco d’Assisi, Tommaso da Celano, dating back to 1246/1247, (

Intagliata 2020) reports the pilgrimage to the sanctuary of St. Nicholas in Bari, during which the miracle of the bag containing a snake took place. Much later, this city also became the setting for the legend of the temptress at Frederick II’s court. The same source identifies the instrument used by Francis to call people during his preaching with a small bell kept in the church of S. Maria degli Angeli (Bonaventura

da Lama 1724, p. 261). Other posthumous traditions link the presence of the Saint in Puglia to his travels to the Holy Land. On the historical level, it is likely that he landed in one or more ports of that region on his return from his mission to Damietta, in 1219–1220.

Almost all the aforementioned places lie on important trans-regional routes, which are cited by the geographer Guidone in 1119 (

Pinder and Parthey 1860). The legacy of ancient roads is strongest in the south of the peninsula, connecting the regions and influencing the fortunes of cities and ports (

Uggeri 1983;

Oliva 2013;

Marchi 2019). Above all, the Appian Way, the Via Traiana and the connection with Gargano seem to constitute the infrastructural backbone on which kings and saints such as Francis and Peter (in reality or in myth), pilgrims and armies, merchants and travellers crossed the region to stop or embark for the eastern and southern Mediterranean (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

2.3. The Via Francigena del Sud

Following the Via Traiana variant of the Via Appia, the Southern Via Francigena corresponds to the pilgrimage route from Rome to Jerusalem and vice versa.

Jerusalem was described by medieval commentators as the capital of God’s earthly kingdom and was considered by them to be the “image of all perfection and the pivot of all cosmological conceptions of their time” (

Dupront 1993;

Marella 2014, p. 124). Unequivocally representing the very essence of Christianity, Jerusalem was therefore the primary goal of the ancient pilgrims. After the granting of freedom of worship to Christians under the edicts of Galerius (311) and Constantine and Licinius (313), churches were built and a considerable flow of pilgrims towards the Holy Places was seen (

Dalena 2014). This increased in the period from Theodosius I to Theodosius II (378–450) and after the construction of important churches such as the Holy Zion Basilica, completed between 392 and 394, the Tomb of Mary, completed shortly afterwards, and others.

The pilgrims on their way to Jerusalem were from “various walks of life, monks, clerics and members of the nobility, especially from Gaul; they made their way to the Holy Places: Apodemius of Burdigala, Deacon Sisinnius of Toulouse, Postumianus, Honoratus of Lérins, the Roman ladies Paula and Fabiola, Deacon Niceas of Aquileia, the Brescian priest Gaudentius, the Breton Pelagius and Deacon Heraclius and Castrician from Pannonia” (

Dalena 2014, p. 12). The travel diaries analysed by

Marella (

2014) provide a detailed description of the Christological monuments and liturgical rites that the ancient pilgrims saw in the Holy Land. Above all, however, they allow us to discover the most popular routes by land and sea, the journey times and the role played in that context by the settlements along the route. Generally speaking, pilgrims travelled by the road system that had been created throughout Europe by the Roman administration, which was still in full working order in late antiquity and indeed was used without interruption until the Middle Ages. In order to reach Jerusalem, pilgrims from Central and Northern Europe had two options at their disposal: they could either descend along the Italian highways to the ports of Puglia and then continue by sea, or they could travel across the Balkans to Constantinople and then either head for Jerusalem along a coastal maritime route or continue overland through present-day Turkey and Syria. The second option was no doubt the shorter route, but it was also fraught with danger and impossible to use in some months of the year (from March to November). The first option was thus preferred. The Anonymous pilgrim from Burdigala (Bordeaux), author of one of the very first travel accounts—the famous Itinerarium Burdigalense—used both options depending on their convenience at the time (

Itineraria romana 1929;

Marella 2012, p. 200).

From his home town, he and a group of pilgrims walked the Via Domitia from Toulouse to Arles, crossed the Alps at Mont Cenis, travelled through northern Italy from Turin to Aquileia, entered the Danube valley and turned south along the Via Diagonalis, which ran diagonally across the Balkan Peninsula. After passing through some inland towns in Slovenia, Hungary, Croatia, Serbia, Bulgaria and present-day Turkey, he reached Constantinople, crossed the Bosporus and continued overland along the inland stretches of the Roman road system, passing through Anatolia and Syria and finally reaching Palestine. On his return journey, the Anonymous palmer travelled with his companions back along the same Middle Eastern roads as on his outward journey, but once he had reached Constantinople, he took the Via Egnatia through Thrace, Macedonia and Epirus to Vlora, where he embarked and crossed the Strait of Otranto, landing in the City of Martyrs. He then travelled up the Salento peninsula along the Via Traiana Calabra, stopping at Brindisi and Bari, thereafter following the Via Appia to Benevento and finally Rome. Other members of the group continued along the Via Flaminia to Rimini and finally along the Via Emilia to Milan, where the “Itinerarium” ends (

Figure 5).

The Itinerarium Burdigalense “recalls in general terms the Iitinerarium Antonini and the Tabula Peutingeriana and is the oldest and most complete odeporic document, a kind of ‘Guide’ for Christian pilgrims going to Jerusalem at a time–the fourth century–when pilgrimage from the West to the holy places assumed significant proportions” (

Dalena 2008, p. 41).

In southern Italy, and Puglia in particular, the itinerary partially follows the consular road known as the Via Traiana (

Dalena 2014), which, in its coastal and inland variants, “was not identified with the Appian-Trajan consular road alone, but also with the Adriatic coastal highway (from Sipontum to Barium) and the inland transhumant herding routes (‘or white roads’)” (

Copeta and Marzulli 2012, p. 238). From Egnatia, the route turned south towards Brindisi (Via Traiana) and from there descended to Otranto (Via Traiana “Calabra”), branching out into various “circuits” throughout Salento and often intersecting with other ancient devotional routes.

During the Middle Ages, and in particular from the First Crusade in 1096 until the fall of Acre in 1293, the itinerary following the antiquam Rome viam remained the most popular among those heading to the Holy Land, the ancient road network of the Roman age forming the central core of a bundle of often alternative roads. Throngs of crusaders and pilgrims from the north passed through Rome on their way down to the ports of Brindisi and Otranto. Once they had fulfilled their vow, they would return to their homeland, retracing the route in reverse: as had been the case in late antiquity, therefore, for returning pilgrims landing in Italy, the Via Traiana constituted the initial stretch of an ideally “Francigena” road, which, after Rome, continued towards the Alpine passes following the consular roads and the so-called “via di Monte Bardone” (

Marella 2014).

The current Via Francigena del Sud connects with the European Vie Francigene cultural itinerary (which follows the stages of the return journey from Rome to Canterbury of the archbishop Sigeric, after receiving the investiture from Pope John XV in 990 AD) in Rome.

The Southern Via Francigena, on the other hand, reproduces the route from Otranto to Rome taken in 333 AD by the anonymous French pilgrim, who, while crossing the Apennines, listed the stages with their relative names, position and distances on the cursus publicus of the late Roman period (

Hunt 1982).

Concerning the name of this route, which links the Apostolic See to the ports of embarkation in Puglia, it should be clear that there is a good reason for identifying it as the continuation of Sigeric’s Francigena, with whose consolidated popularity as an organised route it aspires to be associated. On the basis of the sources, but also in accordance with a constructivist reading of the places, it can be shown that from late antiquity to the Middle Ages and beyond, this particular journey was undertaken via multiple roads that varied over time and that the same name can be found in areas that are quite distant from the route that is now being developed. Taking into account the substantial unity of the Christian world in the view of the ancient pilgrims, it would perhaps have been appropriate to consider a single, unified route, a great European artery linking the three major centres of Christianity (

Oliva 2012, p. 227).

3. The Via Francigena del Sud: From Religious Pilgrimage to Spiritual Route

In the rapid transformation of modern society, in which social and economic innovation seems to be a driving force, there is a need to make room for the demands of the spirit and clearer manifestations of human freedom.

We are witnessing a sort of “anthropological shift”, which is restructuring the person and human societies in terms of lifestyles, outlooks and perspectives. The uniformity of its spiritual motives makes it possible to view it as something that cuts across different cultures with comparable patterns and unifying themes and concepts. It acts as a calming factor with respect to tradition and modernisation, showing that the spiritual motive that animates it can be more than just a ritual: it is a response to the widespread need for spirituality and identity but also for convivial socialisation in contrast to the many negative factors that afflict today’s society (dissonance, discord and conflict). There is a need to enjoy life experiences made up of emotional expectations, associations and nuances, mediated by the knowledge, experience and subjective perception of each individual, which make it possible to manage reality by meeting the growth needs of the individual.

It would seem that walking the trails, which are based on ancient religious pilgrimage routes but have undergone profound transformations over time, fulfils these objectives (

Josan 2009;

Collins-Kreiner 2009,

2010). From the ancient practice of “devotional marches” towards illustrious burial places associated with women and men worthy of veneration to the medieval pilgrimage, we have now come to a new approach: via a long process of transformation affecting the physiognomy of the pilgrims and the routes they cross, the travellers have taken on the features of the “pilgrim-tourist”, i.e., a person who makes use of modern tourism facilities in the areas crossed by the route. What remains firmly anchored to the original meaning of pilgrimage is the aspect of the journey, which has two specific features determined by the variable motives for undertaking it: the first concerns the traveller who enters unusual contexts, while the second is about the recovery of a more interior, spiritual dimension. While the medieval pilgrim set off towards some sanctuary out of faith (causa orationis) or a need for inner mortification (causa poenitentia) or to beg for divine or saintly intervention (peregrinatio pro voto) from the eponymous saint of the place of worship (

Vantaggiato 2012), today’s walkers have other motives (

Singh 2013). These include faith, but above all, they concern spiritual needs, which

Castegnaro (

2018) describes as a vast and invisible “middle ground” lying between the two extreme positions of fundamentalists and atheists/agnostics, occupied by those who sense a spiritual meaning in nature, culture, art and socialisation (p. 127). Lacking any confessional tradition, many set out in search of their own identity, as well as stability, clarity and a way to shed some of their baggage; they are on an inner quest, seeking an intimate sense of security that allows them to face everyday life with greater serenity and wisdom (

Barber 1993). The motives for the journey have thus changed, shifting from an essentially religious endeavour to a “search for meaning”. This process may thus rightly be called “spiritual”, as it is more “inclusive” and perhaps reflects more precisely the experiential motives of many contemporary “travellers”. It is also more closely related to the “tourist traveller” who looks with admiration and nostalgia on the heroic figures of pilgrims. Seemingly disillusioned, yet fascinated by mystery, today’s traveller seeks out ancient testimony that responds to a wide range of needs: for identity, companionship and culture. Those who follow ancient pilgrimage routes have eliminated the extraordinary hardships and pains, both material and spiritual, that characterised the medieval pilgrim, and yet they appreciate the charm of the unexpected, have a taste for adventure and value the rich opportunities for acquiring new knowledge.

Today’s traveller seeks to recover the meaning of the journey as an experience that is fundamental to existence, a meaning which unfortunately today is frequently a pale imitation, a facsimile of places, people and emotions that has become part of a simple ritual, presented by the media and assorted commercial interests, resulting in the sort of standardisation and replication that is typical of organised trips.

The route of the Via Francigena del Sud is not exempt from these risks. The arrival of travellers is creating a tourist destination composed of places with a strong religious connotation, whose attractions are cultural and/or spiritual, as well as frankly naturalistic and social. The route integrates with cultural tourism via a co-mingling of motives, needs and trends that are highly heterogeneous and entail continuous interaction between spiritual, cultural, naturalistic, social and leisure aspects. It is open to memory but above all to the present and to the region as it is currently configured. Its value lies in its orientation towards testimony of the past and spirituality and towards regional characteristics and the complexity of experience conveyed through regional heritage. Such heritage manifests the past by means of the traces of ancient pilgrimage routes, but it is seen above all in the testimony of spirituality manifested in the locations via the material and immaterial heritage generated by the communities. Along the southern Via Francigena, spirituality and religion derive not only from the route of medieval pilgrims, along with the celebrated places of worship linked to the Virgin Mary and the paths of saints: they also represent a form of knowledge and understanding of the religious issues arising within a community, exemplified by the celebration of festivals and local cults. This shows how the religious dimension can be detached from specific events in favour of an expression of spirituality inherent to the customs and traditions of each region (

Piersanti 2014). This involves participatory interaction with local communities, their artistic and craft activities and the life of small villages, where there is a strong sense of community, sharing and pilgrim and family hospitality. These represent the immense submerged resources of the Francigena del Sud, which crosses small towns, sometimes in the process of being abandoned, where time stands still and the landscape holds elements of a nostalgic return to the past (

Trono et al. 2017). This can be seen, for example, in the manifestations and expressions of modernity among the hospitable and welcoming people of Salento, where the ancient soul survives, and the flavour of remote times, of a world now too far away, with its rites, myths and magic, is manifested in the prehistoric cults of fire and stone. A central element of the landscape and the expression of a primitive conception of peasant culture, an element of shelter, an enclosure for a once-barren land made fertile by immense toil, but also the material of humble yet monumental architectural forms, stone is also a sacred and propitiatory symbol. It flourishes in the dolmens and menhirs found everywhere, among the olive trees, in front of churches and Byzantine crypts, on the side of the road, a nostalgic reminder of prehistoric cults and times long gone. It is the heightening of that feeling of loss and recovery of the past that is reaffirmed in the beauty of the hilly landscape of Murgia, with its fantastic conical whitewashed buildings, standing out against the intense green of the ancient olive trees. Here, the agricultural landscape appears finely woven with dry stone walls and enriched by the “masserie”, the nerve centres of the old cereal and grazing farms, whose functions evoke a long-since vanished feudal economic organisation (

Formica 1982, p. 140).

Myths, legends and folk traditions recur along the Via Michaelica (St Michael’s Way) of the Francigena del Sud. Climbing the green and rugged mountains of Gargano, it reaches Monte Sant’Angelo, the national sanctuary of the Lombards which united in worship Langobardia Maior (whose capital was Pavia) and Langobardia Minor (whose capital was Benevento) with the Holy Land. Popular folklore, religious festivals and fertility rites of pagan origin (seen in the procession of the “fracchie” (torches)) in San Marco in Lamis intertwine with each other to the point of blending with the existing culture. Along the entire Via Francigena del Sud, modernity and memory merge in forms both ancient and new in a succession of archaeological remains, churches, towers and castles, all the way to the cobblestones at the gates of Castel Gandolfo, where the Via Appia Antica ends, marked on either side by tombstones, mausoleums and stone blocks that have been there since ancient times.

Considering the spiritual motive, as global as it is intimate and subjective, the Via Francigena del Sud lives and develops in the physical places situated along the route, giving rise to a retroactive dimension that excludes the idea of “reproduction”. Its originality derives from local contexts and from cultural and social phenomena with a “glocal” dimension, in which the local cultural aspects constantly interface with a “transcultural” dimension hybridised by external factors (

Trono and Castronuovo 2018).

4. From the “Ancient” to the “New” Travellers of the Mediterranean

What makes the route of the Southern Via Francigena even more valuable is that it is intended as a transit route towards the East, the Holy Land, Jerusalem, via the Mediterranean. The Mare nostrum is the end result of a historical, cultural, emotional and sensorial process. Pondering the value of this sea means engaging with a huge variety of expressive and cultural forms that have helped build the history of Europe (

Zerbi 1991), whose identity lies precisely in the maritime and coastal origins of its civilisation and its constant openness to the rest of the world (

Dematteis 1997, p. 21). Once the centre of civilisation, characterised by its universality, over the years, the Mare nostrum has lost the absolute centrality conferred on it by the pilgrimages to the Holy Land until the 11th century and the subsequent “armed pilgrimage” of the crusaders (

Cardini 2007). For almost two thousand years, Christian pilgrims set out on their journey, sailing the Mediterranean to reach the Holy Land and visit the places where Christ lived, preached and made his final journey to Calvary. They became part of the long encounter between Christianity and Islam aimed at producing positive cultural and economic results (

Cardini 2007), which Venetian and Genoese traders were able to keep alive in the following centuries (

Cardini 2002,

2007). The Christians of Europe indicated in their travel diaries the faith that had driven them to undertake such a long and dangerous journey, a motive that still has a clear spiritual justification even today. Today’s travellers are prompted by the search for inner wellbeing, the recovery of the soul, the desire to experience transcendence or to escape from everyday life and family duties. There is also a desire for growth, to get back into shape, to overcome loss and recharge their batteries via a sense of autonomy and freedom, but a role may also be played by a desire for adventure and curiosity, for companionship and human contact or, more simply, the religious motive.

However, these are not the only motives of those who still attempt to sail the Mediterranean, today considered one of the riskiest crossings for migrants in the world. The Mare nostrum, which continues to play a role in the destiny of peoples, is today the scene of naval traffic, commercial challenges and flows of men and women. They are no longer pilgrims travelling to and from the Holy Land but African and Asian migrants, who follow invisible routes that oblige them to attempt to cross the Mediterranean. Its waters are now affected by serious environmental pressures, and strong economic and criminal interests are intertwined. There is a frenetic and unregulated race to seize precious resources on the seabed, destabilising the region, which is already collapsing under the weight of the socio-political unsustainability of regimes in the Arab world, while Europe struggles to find its own dimension and to confront its own past and history. That history—as Pellitteri points out—“is also a political product, derived from the mastery of the past and the consciousness of time”, which is now obliging Europe to face its “historical responsibilities” (

Pellitteri 2018).

Questioning the future of Europe means confronting the history and cultural heritage of the Mediterranean, assembling the pieces of a complex mosaic whose common motif is an emphasis on cultural heritage, while respecting the environment, legality and human rights (

Matvejevic 2006;

Braudel [1987] 2017).

The Mediterranean is currently being crossed by human beings who wish to fulfil a dream of freedom and democracy: their voyage is not linked to flight as a search for refuge, as in the myth of Ulysses, but to the journey of Abraham, justified by a “need to go beyond, for something more […] a race to which we are driven by an irrepressible need to “get out”: “leave your land and go!”; cast off your own being and its immobility, respond to the need to go beyond, to escape, to get away from yourself”. We are thus dealing with a metaphysical desire, which sees the Mediterranean as a “sea of complexity [… a sea ] in which it is still possible to find positive signs and perspectives regarding both memories and projects, the past and the future, allowing the continuation of history [and ] an alternative renewal: freed from the tranquilising notion of the great lake (a dead sea!), having become a sea that boils, crossed by different cultures and religions and not only by the dinghies of desperate people and the fast vessels of smugglers […]. And it is precisely by passing through the Mediterranean that we Europeans can examine what we have been, what we are and what we could be, setting in motion a healthy exercise of memory, which for us is nothing other than the grounding of the values by which our culture is supposed to be inspired. This task is unavoidable for us Westerners today. By immersing ourselves, so to speak, in the Mediterranean, it is possible to grasp those characteristics of western civilisation that only the most distracted reading of the events of recent decades could allow us to culpably neglect” (

Signore 2007, p. 20).

5. Conclusions

Cultural and religious itineraries are gaining more and more importance in contemporary approaches to slow tourism. In their blend of spirituality and the search for knowledge, these itineraries combine the faith motive with interest in nature and the landscape, with its varying complexity, from the scenic-perceptive level to knowledge of its links to regional identity.

Following the ancient routes of the Via Appia and Via Traiana through regions and contexts that for medieval pilgrims constituted the harshest and most tiring stretch of the journey, for today’s travellers, the Via Francigena del Sud offers the social and cultural values of discovery and enrichment. The route can be seen as a quest, involving personal growth, wonderful landscapes, “a true human quality-of-life resource” and a “primary encyclopaedia of our knowledge” (

Croce and Perri 2009, p. 60), which still manages to convey the idea of lost harmony and the metaphysics of beauty. Walking it helps recover the memory of places, its users experiencing a dimension of the past involving aspects that are quite different from the classic “pilgrimage”. It offers cultural and experiential enrichment by intercepting the demands of society and religion in a cultural context pervaded by complexity, cultural pluralism and a “polytheism of values”.

In the creation of religious-cultural itineraries, as described in the previous sections, the places’ elements of originality are intertwined with socio-cultural values and the subjective components (interior and cultural) of the walker through the experience of anthropological liminality (

Turner and Turner 1997). The authentic dimension goes beyond what is measurable with an objectivist approach based on the reliability of the sources with respect to the research theme that drives the journey. As a matter of fact, when it is able to evoke in the user its matrices of culture and faith, this experience is enriched with symbolic meanings and interior implications.

From this point of view, if properly structured, the paths of the “epiphanies” of St. Peter and St. Francis, both real and those based on more or less ancient local traditions, take on their rightful importance. The Petrine cult as handed down to the modern day is closely linked to the roots of Mediterranean and European evangelisation. This ancestral relationship is evident in the reference to footprints and in the association with the presence of water sources used to baptise the first Christians. The tradition of St. Francis, on the other hand, although linked to a conventual and more cultured environment, always finds new strength due to the power of renewal of the faith that the Saint introduced in all communities. His message of serenity and inner simplicity made the need for “communitas” resonate in the cities of the late Middle Ages, persisting even in the following centuries. For this reason, his preaching and miracles are mainly associated with convents, squares and natural places of particular charm.

The path of the “Via Francigena del Sud” to Rome,

Caput mundi, is located at the centre of a journey between two

Finis terrae, Santiago and Jerusalem, at a time when Europe was the centre of the world. For some current wayfarer, the “Via Francigena del Sud” is the journey towards Jerusalem. For many others, it has a social and cultural value, filled with discovery and enrichment. The wayfarer who sets off today along that route is interested above all in more dynamic and participatory ways of learning about historical events and the various components of the region’s identity, the perception of which is filtered by the traveller’s culture. In this context, the traveller’s interpretation of “Via Francigena del Sud” is mediated by the travel experiences of people who are “on the road” and involved in a dialogue that is open to local cultures (

La via Francigena Nel Sud 2021). Retracing the dense and extensive network of roads and paths associated with ancient and medieval mobility is a powerful way to enhance the historical, cultural and anthropological values of its most important localities. The “Via Francigena del Sud” adds knowledge of heritage and sites to the travellers. Moreover, it not only serves as a common thread to link essential components of the physical and human landscape (e.g., nature, art, architecture, archaeology, rural settlements) but also brings together gastronomical traditions, ancient crafts and distinctive local products, local feasts and folklore.

For modern travellers, completing it today can represent the end of a pilgrimage, where anxiety is banished, the soul is freed, toil ends, and they can imagine being reborn to a new life. That rebirth is what those who cross the Mediterranean today yearn for, pursuing their European dream to ensure the rights of the person and peaceful integration between different peoples (

De Cesaris 2017, p. 22). Finally, this is the underlying meaning of the Francigena (

Ricciardi 2011). It is the recovery of the awareness of a common cultural and spiritual matrix that connects the East to the West, on which the European identity has been built and a “new Europe” can be built: a community no longer founded only “on the identity of origins or on belonging to a place, but on that equally true and profound identity that is realised by crossing borders, in that construction of oneself, which is change, encounter, interbreeding, contamination with the other. There is no civilisation, […] there will be no European identity, without this continuous going out of oneself and meeting with the other, without that feeling at ease in the complexity of differences” (

Diodato 2017, pp. 71–72).