Religious Identity and Family Practices in a Post-Communist Society: The Case of Division of Labor in Childcare and Housework

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Religious Identity and Religious Values in the Context of Social Transformations

3. Family Practices and Religious Identity

4. Family Values, Practices and Gender Equality from State-Imposed to Lived Reality

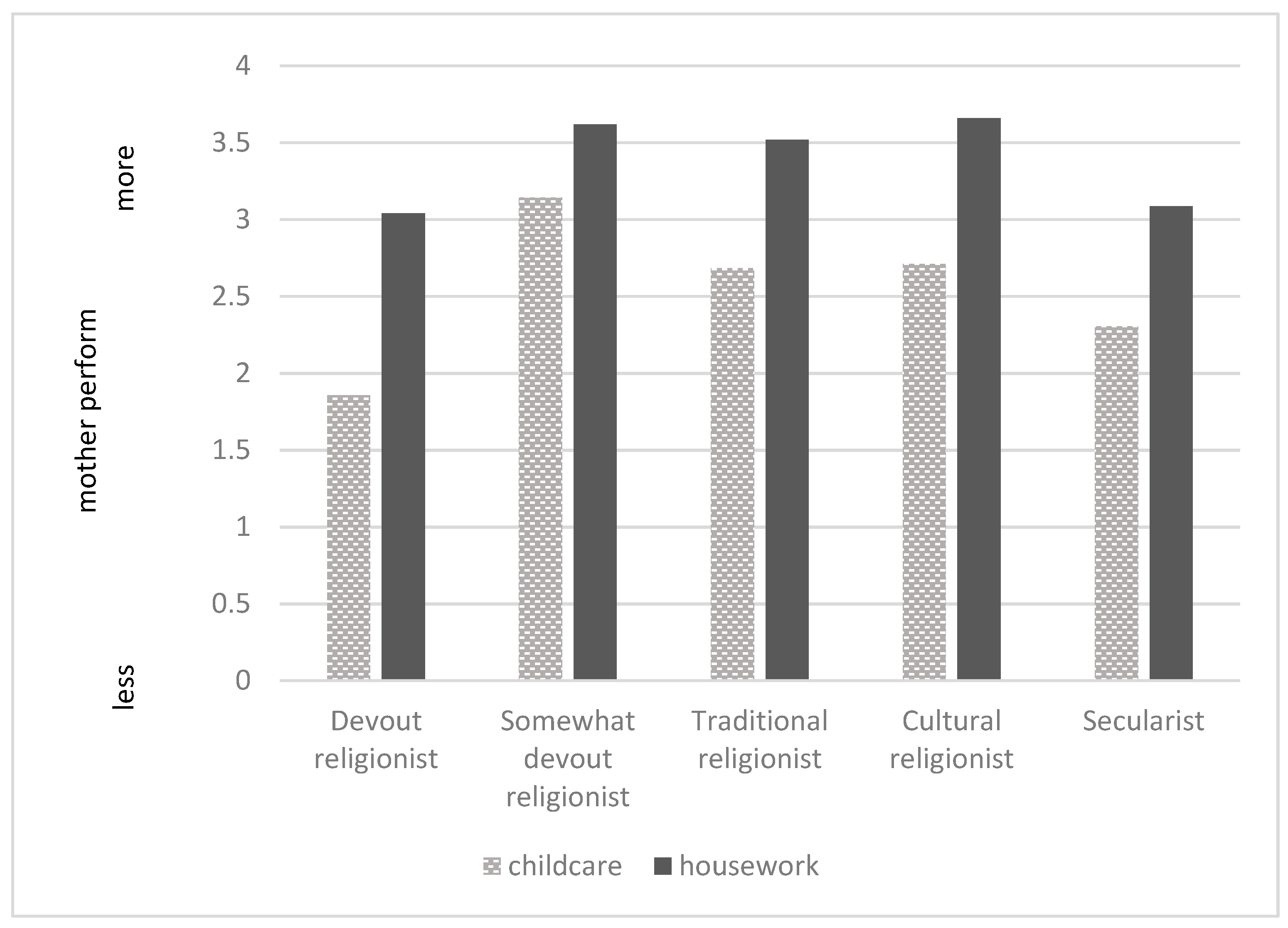

- Religiosity influences family practices in the division of housework and childcare: the more religious the individuals are, the more traditional and non-egalitarian family roles they sustain.

- Non-believers or secularists practice more egalitarian family practices manifesting in more equal childcare and housework division.

5. Data and Methods

5.1. Dependent Variable

5.2. Independent Variable

5.3. Control Variables

6. Results

Descriptive Analysis

7. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aassve, Arnstein, Gulia Fuochi, and Letizia Mencarini. 2014. Economic Dependency and Gender Ideology across Europe Desperate Housework: Relative Resources, Time Availability. Journal of Family Issues 35: 1000–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ališauskienė, Milda. 2020. The Social History of Irreligion in Lithuania (from the 19th century to the present): Between Marginalization, Monopoly and Disregard? In Freethought and Atheism in Central and Eastern Europe. Edited by Tomáš Bubík, Atko Remmel and David Václavík. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 155–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ališauskienė, Milda. 2021. The Role of Religion in the Lives of the Last Soviet Generation in Lithuania. Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe 41: 16–34. [Google Scholar]

- Altintas, Evrim, and Oriel Sullivan. 2017. Trends in fathers’ contribution to housework and childcare under different welfare policy regimes. Social Politics 24: 81–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrozaitienė, Dalia, Rasa Balandienė, Natalja Nikiforova, Eglė Norušienė, Edita Onichovska, Vanda Vaitekūnienė, Julija Važnevičiūtė, and Asta Vildžiūnienė. 2013. Lietuvos Respublikos 2011 metų gyventojų ir būstų surašymo rezultatai. Vilnius: Lietuvos statistikos departamentas, p. 152. [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman, Nancy Tatom, and Wade Clark Roof. 1995. Work, Family and Religion in Contemporary Society Remaking Our Lives. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ammons, Samantha K., and Penny Edgell. 2007. Religious Influences on Work-Family Trade-Offs. Journal of Family Issues 23: 794–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwin, Sarah. 2000. Introduction: Gender, State and Society in Soviet and Post-Soviet Russia. In Gender, State and Society in Soviet and Post-Soviet Russia. Edited by Sarah Ashwin. London: Routledge, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Azhgikhina, Nadezhda. 2006. Russian Journalism after 2000: New Censorship, New Markets and New Communities. Keynote Speech, BASEES Annual Conference (Cambridge, 1–3 April 2006). In Gender, Equality and Difference during and after State Socialism. Edited by Rebecca Kay. London: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Banton, Michael. 1983. Racial and Ethnic Competition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, Eileen. 2006. We’ve Got to Draw the Line Somewhere: An Exploration of Boundaries That Define Locations of Religious Identity. Social Compass 53: 201–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, Ulrich. 2002. Individualization: Institutionalized Individualism and Its Social and Political Consequences. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker, Rogers. 2017. Between nationalism and civilizationism: the European populist moment in comparative perspective. Ethnic and Racial Studies 40: 1191–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buber-Ennser, Isabella, and Ralina Panova. 2014. Attitudes towards Parental Employment Across Europe, in Australia and in Japan, Vienna Institute of Demography Working Papers, No. 5/2014. Vienna: Vienna Institute of Demography.

- Casanova, Jose. 1994. Public Religions in the Modern World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin, Andrew. J. 2016. A Happy Ending to a Half-Century of Family Change? Population and Development Review 42: 121–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Shannon N., and Theodore N. Greenstein. 2020. Why Who Cleans Counts. What Housework Tells Us about American Family Life. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, Abby, and Lois Lee. 2014. Making sense of surveys and censuses: Issues in religious self-identification. Religion 44: 345–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edgell, Penny. 2009. Religion and Family. In The Oxford Handbook of the Sociology of Religion. Edited by Peter Clarke. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1038–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Institute for Gender Equality. 2020. Gender Equality Index, Index Score for European Union for the 2020 Edition. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/gender-equality-index/2020 (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- Frenkel, Michal, and Varda Wasserman. 2020. With God on Their Side: Gender–Religiosity Intersectionality and Women’s Workforce Integration. Gender & Society 34: 818–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, Anthony. 1990. The Consequences of Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider, Frances, Calvin Goldscheider, and Antonio Rico-Gonzalez. 2014. Gender Equality in Sweden: Are the Religious More Patriarchal? Journal of Family Issues 35: 892–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldscheider, Frances, Eva Bernhardt, and Trude Lappegård. 2015. The Gender Revolution: A Framework for Understanding Changing Family and Demographic Behavior. Population and Development Review 41: 207–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzymala-Busse, Anna. 2015. Nations under God: How Churches use their Moral Authority to Influence Policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gull, Bethany, and Claudia Geist. 2020. Godly Husbands and Housework: A Global Examination of the Association between Religion and Men’s Housework Participation. Social Compass 67: 389–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervieu-Léger, Danièle. 1998. The Transmission and Formation of Socioreligious Identities in Modernity: An Analytical Essay on the Trajectories of Identification. International Sociology 13: 213–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglis, Tom. 2007. Catholic Identity in Contemporary Ireland: Belief and Belonging to Tradition. Journal of Contemporary Religion 22: 205–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, Richard. 2014. Social identity. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, Rebecca, ed. 2007. Introduction: Gender, Equality and the State from ‘Socialism’ to ‘Democracy’? In Gender, Equality and Difference during and after State Socialism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Kraniauskas, Liutauras. 2009. Vyriškas ir moteriškas šeimos pasaulis: Struktūros poveikis ar tapatumo konstravimo strategija? In Lietuvos šeima: Tarp tradicijos ir naujos realybės. Edited by Vlada Stankūnienė and Aušra Maslauskaitė. Vilnius: Socialinių tyrimų centras, pp. 169–219. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznecovienė, Jolanta, Aušra Rutkienė, and Milda Ališauskienė. 2016. Religingumas ir/ar dvasingumas Lietuvoje: Religijos sociologijos perspektyvos: Mokslo studija. Kaunas: Pasaulio lietuvių kultūros, mokslo ir švietimo centras. [Google Scholar]

- Laumenskaitė, Eglė Irena. 2015. Krikščioniškumas kaip socialinių laikysenų veiksnys totalitarinėje ir posovietinėje visuomenėje. Vilnius: Lietuvių katalikų mokslo akademija. [Google Scholar]

- Mannheim, Karl. 1952. The Problem of Generations. In Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge. Edited by Paul Kecskemeti. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 276–320. [Google Scholar]

- Maslauskaitė, Ausra. 2010. Lietuvos šeima ir modernybės projektas: Prieštaros bei teoretizavimo galimybės. Filosofja. Sociologija 21: 310–19. [Google Scholar]

- Maslauskaitė, Aušra. 2022. Lithuania’s gender revolution. Reversed and stalled. In Soviet and Post-Soviet Lithuania—Generational Experiences. Edited by Melanie Illic and Laima Žilinskienė. London: Routledge, pp. 191–209. [Google Scholar]

- Maslauskaite, Ausra, and Anja Steinbach. 2020. Paternal Psychological Well-being After Union Dissolution: Does Involved Fatherhood Have a Protective Effect? In Parental Life Courses after Separation and Divorce in Europe. Edited by Michaela Kreyenfeld and Heike Trappe. Berlin: Springer, pp. 215–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, Matthew, and Jeremy Reynolds. 2018. Religious Affiliation and Work–Family Conflict Among Women and Men. Journal of Family Issues 39: 1797–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouritsen, Per. 2006. The Particular Universalism of a Nordic Civic Nation: Common Values, State Religion and Islam in Danish Political Culture. In Multiculturalism, Muslims and Citizenship: A European Approach. Edited by Tariq Modood, Anna Triandafyllidou and Ricard Zapata-Barrero. London: Routledge, pp. 70–91. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, Lisa D., and Arland Thornton. 2007. Religious identity and family ideologies in the transition to adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family 69: 1227–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelkmans, Mathijs. 2009. Introduction: Post-Soviet Space and the Unexpected Turns of Religious Life. In Conversion after Socialism: Disruptions, Modernisms and Technologies of Faith in the Former Soviet Union. Edited by Mathijs Pelkmans. Oxford: Berghahn Books, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Perales, Francisco, and Gary Bouma. 2019. Religion, Religiosity and Patriarchal Gender Beliefs: Understanding the Australian Experience. Journal of Sociology 55: 323–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Petts, Richard J. 2018. Paternity Leave, Father Involvement, and Parental Conflict: The Moderating Role of Religious Participation. Religions 9: 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pew Research Center. 2018. The Religious Typology. A New Way to Categorize Americans by Religion. Available online: https://www.pewforum.org/2018/08/29/the-religious-typology/ (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Pollack, Detlef, Olaf Muller, and Gert Pickel, eds. 2012. The Social Significance of Religion in the Enlarged Europe. Secularization, Individualization and Pluralization. Farnham: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Ramet, Sabrina Petra, ed. 1992. Religious Policy in the Soviet Union. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ramet, Sabrina Petra, ed. 2014. Religion and Politics in Post-Socialist Central and Southeastern Europe. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Ramet, Sabrina Petra. 2010. Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Read, Jen’nan Ghazal. 2003. The Sources of Gender Role Attitudes among Christian and Muslim Arab-American Women. Sociology of Religion 64: 207–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roof, Wade Clark. 2009. Generations and Religion. In The Oxford Handbook of the Sociology of Religion. Edited by Peter Clarke. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 616–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwörer, Jakob, and Xavier Romero-Vidal. 2020. Radical right populism and religion: Mapping parties’ religious communication in Western Europe. Religion, State & Society 48: 4–21. [Google Scholar]

- Simons, Greg, and David Westerlund, eds. 2015. Religion, Politics and Nation-Building in Post-Communist Countries. Farnham, Surrey and Burlington: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Stoeckl, Kristina. 2020. The Rise of the Russian Christian Right: The Case of the World Congress of Families. Religion, State & Society 48: 223–38. [Google Scholar]

- Streikus, Arūnas. 2012. The History of Religion in Lithuania since the Nineteenth Century. In Religious Diversity in Post-Soviet Society. Ethnographies of Catholic Hegemony and the New Pluralism in Lithuania. Edited by Milda Ališauskienė and Ingo W. Schröder. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 37–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, Oriel. 2011. An end to gender display through the performance of housework? A review and reassessment of the quantitative literature using insights form the qualitative literature. Journal of Family Theory and Review 3: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, Oriel, Jonathan Gershuny, and John P. Robinson. 2018. Stalled or uneven gender revolution? A long-term processual framework for understanding why change is slow. Journal of Family Theory & Review 10: 263–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voicu, Mălina, Bogdan Voicu, and Katarina Strapcova. 2009. Housework and Gender Inequality in European Countries. European Sociological Review 25: 365–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wike, Richard, Jacob Poushter, Laura Silver, Kat Devlin, Janell Ferrerolf, Alexandra Castillo, and Christine Huang. 2019. European Public Opinion Three Decades after the Communism. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2019/10/14/gender-equality-2/ (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- Wilcox, Bradford W. 2004. Soft Patriarchs, New Men: How Christianity Shapes Fathers and Husbands. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Žiliukaitė, Rūta, Arūnas Poviliūnas, and Aida Savicka. 2016. Lietuvos visuomenės vertybių kaita per dvidešimt nepriklausomybės metų. Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla. [Google Scholar]

| Column Percent | Means (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Childcare division (−1 to 5) | 2.6 (1.9) | |

| Housework division (−1 to 6) | 3.4 (2.0) | |

| Religiosity | ||

| Devout religionist | 11.4 | |

| Somewhat devout religionist | 11.4 | |

| Traditional religionist | 60.4 | |

| Cultural religionist | 8.5 | |

| Secularist | 8.3 | |

| Relative incomes | ||

| R earns more than P | 32.8 | |

| R earns less than P | 45.8 | |

| R and P equally | 21.4 | |

| R education | ||

| University | 33.4 | |

| Semi-tertiary | 29.6 | |

| Secondary or lower | 36.9 | |

| Household income | ||

| 1st quartile (lowest) | 16.0 | |

| 2nd quartile | 23.2 | |

| 3rd quartile | 29.0 | |

| 4th quartile (highest) | 31.9 | |

| Women | 59.2 | |

| Age of the youngest child living at home | 10.3 (5.8) | |

| Gender of children | ||

| At least one girl | 52.8 | |

| No girls | 47.2 | |

| Gender attitudes (traditional–egalitarian) | 2.42 (0.53) | |

| Living area | ||

| Urban | 66.0 | |

| Rural | 34.0 | |

| Number | 1268 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | (SE) | b | (SE) | b | (SE) | b | (SE) | |

| Religiosity | ||||||||

| Devout religionist | ||||||||

| Somewhat devout religionist | 1.08 *** | 0.22 | 0.96 *** | 0.22 | 0.80 *** | 0.20 | 0.76 *** | 0.20 |

| Traditional religionist | 0.63 *** | 0.15 | 0.60 *** | 0.16 | 0.51 *** | 0.14 | 0.48 *** | 0.14 |

| Cultural religionist | 0.74 *** | 0.24 | 0.71 *** | 0.24 | 0.59 ** | 0.22 | 0.54 ** | 0.23 |

| Secularist | 0.1 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.32 | 0.24 |

| Relative incomes | ||||||||

| R and P equally (ref.) | ||||||||

| R earns more than P | 0.50 *** | 0.15 | 0.51 *** | 0.15 | 0.055 ** | 0.18 | ||

| R earns less than P | 0.84 *** | 0.14 | 0.40 *** | 0.14 | −0.02 | 0.35 | ||

| R education | ||||||||

| University (ref.) | ||||||||

| Semi-tertiary | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.13 | ||

| Secondary or lower | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.13 | −0.01 | 0.13 | ||

| Household incomes | ||||||||

| 4th quartile (highest) (ref.) | ||||||||

| 3rd quartile | −0.12 | 0.17 | −0.004 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.12 | ||

| 2nd quartile | −0.07 | 0.15 | 0,04 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.13 | ||

| 1st quartile (lowest) | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.26 | 0.187 | 0.30 | 0.18 | ||

| Women | 0.62 *** | 0.15 | 029 | 0.26 | ||||

| R’s age | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||

| Age of the youngest child | −0.03 ** | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.01 ** | ||||

| At least one girl in the family | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.10 | ||||

| Gender values (traditional–egalitarian) | −0.57 *** | 0.09 | −0.55 *** | 0.09 | ||||

| Housework division | 0.33 *** | 0.02 | 0.33 *** | 0.02 | ||||

| Urban | 0.28 ** | 0.11 | 0.28 ** | 0.11 | ||||

| Women*earns more than P (ref.) | ||||||||

| Women*earns less than P | 0.7 * | 0.42 | ||||||

| Women*earns same as P | 0.29 | 0.32 | ||||||

| R2 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.25 | ||||

| Number | 1043 | |||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | (SE) | b | (SE) | b | (SE) | b | (SE) | |

| Religiosity | ||||||||

| Devout religionist | ||||||||

| Somewhat devout religionist | 0.40 * | 0.24 | 0.30 | 0.24 | −0.05 | 0.22 | −0.11 | 0.22 |

| Traditional religionist | 0.30 * | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.01 | 0.16 | −0.04 | 0.16 |

| Cultural religionist | 0.30 | 0.26 | 0.19 | 0.26 | −0.03 | 0.24 | −0.07 | 0.25 |

| Secularist | −0.14 | 0.26 | −0.21 | 0.28 | −0.12 | 0.25 | −0.07 | 0.26 |

| Relative incomes | ||||||||

| R and P equally (ref.) | ||||||||

| R earns more than P | 0.39 ** | 0.16 | 0.52 *** | 0.17 | 0.43 * | 0.20 | ||

| R earns less than P | 0.44 *** | 0.15 | −0.09 | 0.15 | −1.35 *** | 0.38 | ||

| R education | ||||||||

| University (ref.) | ||||||||

| Semi-tertiary | 0.49 *** | 0.15 | 0.46 *** | 0.14 | 0.45 *** | 0.13 | ||

| Secondary or lower | 0.73 *** | 0.14 | 0.70 *** | 0.14 | 0.68 *** | 0.14 | ||

| Household incomes | ||||||||

| 4th quartile (highest) (ref.) | ||||||||

| 3rd quartile | −0.24 | 0.15 | −0.19 | 0.13 | −0.17 | 0.13 | ||

| 2nd quartile | -0.10 | 0.16 | −0.09 | 1.52 | −0.05 | 0.15 | ||

| 1st quartile | −0.27 | 0.21 | −0.40 ** | 0.19 | −0.32 * | 0.19 | ||

| Women | 0.62 *** | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.28 | ||||

| R’s age | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||

| Age of the youngest child | 0.04 *** | 0.01 | 0.04 *** | 0.01 | ||||

| At least one girl in the family | −0.24 ** | 0.11 | −0.23 ** | 0.01 | ||||

| Gender values | −0.10 | 0.10 | −0.05 | 0.10 | ||||

| Childcare division | 0.4 *** | 0.03 | 0.39 *** | 0.03 | ||||

| Urban | −0.11 | 0.12 | −0.11 | 0.12 | ||||

| Women*earns more than P (ref.) | ||||||||

| Women*earns less than P | 1.79 *** | 0.42 | ||||||

| Women*earns same as P | 0.25 | 0.34 | ||||||

| R2 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.22 | ||||

| Number | 1043 | |||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alisauskiene, M.; Maslauskaite, A. Religious Identity and Family Practices in a Post-Communist Society: The Case of Division of Labor in Childcare and Housework. Religions 2021, 12, 1040. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12121040

Alisauskiene M, Maslauskaite A. Religious Identity and Family Practices in a Post-Communist Society: The Case of Division of Labor in Childcare and Housework. Religions. 2021; 12(12):1040. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12121040

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlisauskiene, Milda, and Ausra Maslauskaite. 2021. "Religious Identity and Family Practices in a Post-Communist Society: The Case of Division of Labor in Childcare and Housework" Religions 12, no. 12: 1040. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12121040

APA StyleAlisauskiene, M., & Maslauskaite, A. (2021). Religious Identity and Family Practices in a Post-Communist Society: The Case of Division of Labor in Childcare and Housework. Religions, 12(12), 1040. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12121040