To Heaven through Hell: Are There Cognitive Foundations for Purgatory? Evidence from Islamic Cultures

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. The Balance Doctrine in Islamic Afterlife Teachings

Those who commit grave sins, in as much as God permits it, and then die persisting in them [i.e., without having repented], but whose good actions and evil actions are equibalanced (istawat), no additional evil action having been committed by them, are forgiven and will not be held responsible for anything they have done. God Exalted has said: “The good deeds will drive away the evil deeds.” (Q 11:114).(Ibn Ḥazm 2005, pp. 133–34, translated to English by Lange 2013)

The penalty of the Fire is waived for various reasons. I will list here more than ten reasons which are deduced from the Qur’an and Sunnah …The third means of pardon is provided by good deeds, for one good act will fetch ten equal rewards and one evil act will incur only one equal penalty. Woe, therefore, to those whose one-to-one penalties outdo their ten-fold rewards. Allah has said, “The good deeds remove those that are evil” [11:14], and the Prophet (peace be on him) said, “Do good after evil so that it may wipe out the latter.

2.2. Purgatory and Proportionality

2.3. Purgatory as Theological Incorrectness

2.4. Pilot Studies

2.5. Study Hypotheses

3. Results

3.1. Study 1: CTAP Belief among Jordanian Muslim Youth

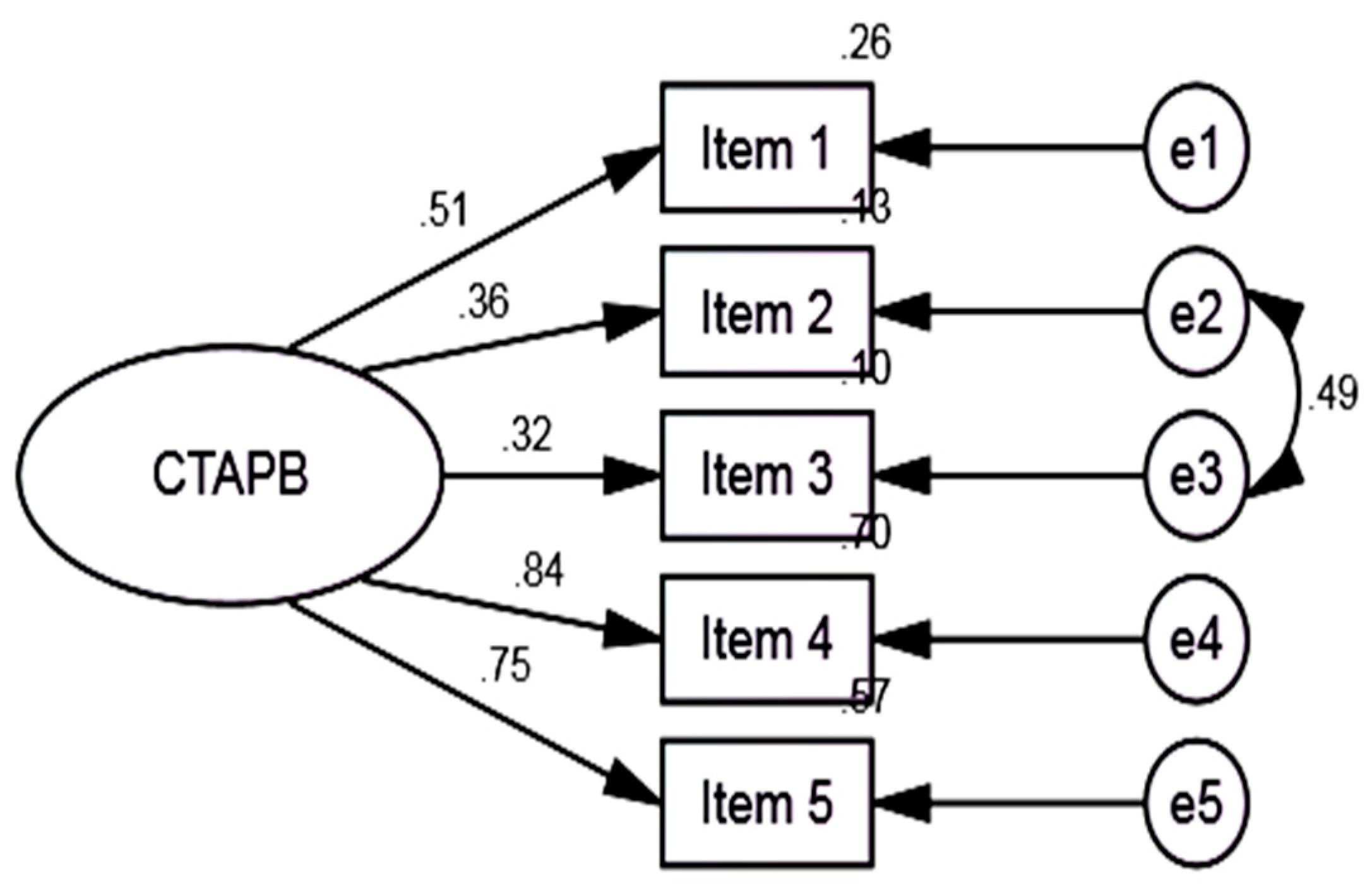

3.1.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

3.1.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

3.1.3. Size of Phenomenon

3.2. Study 2: CTAP Belief among Malaysian Muslim Youth

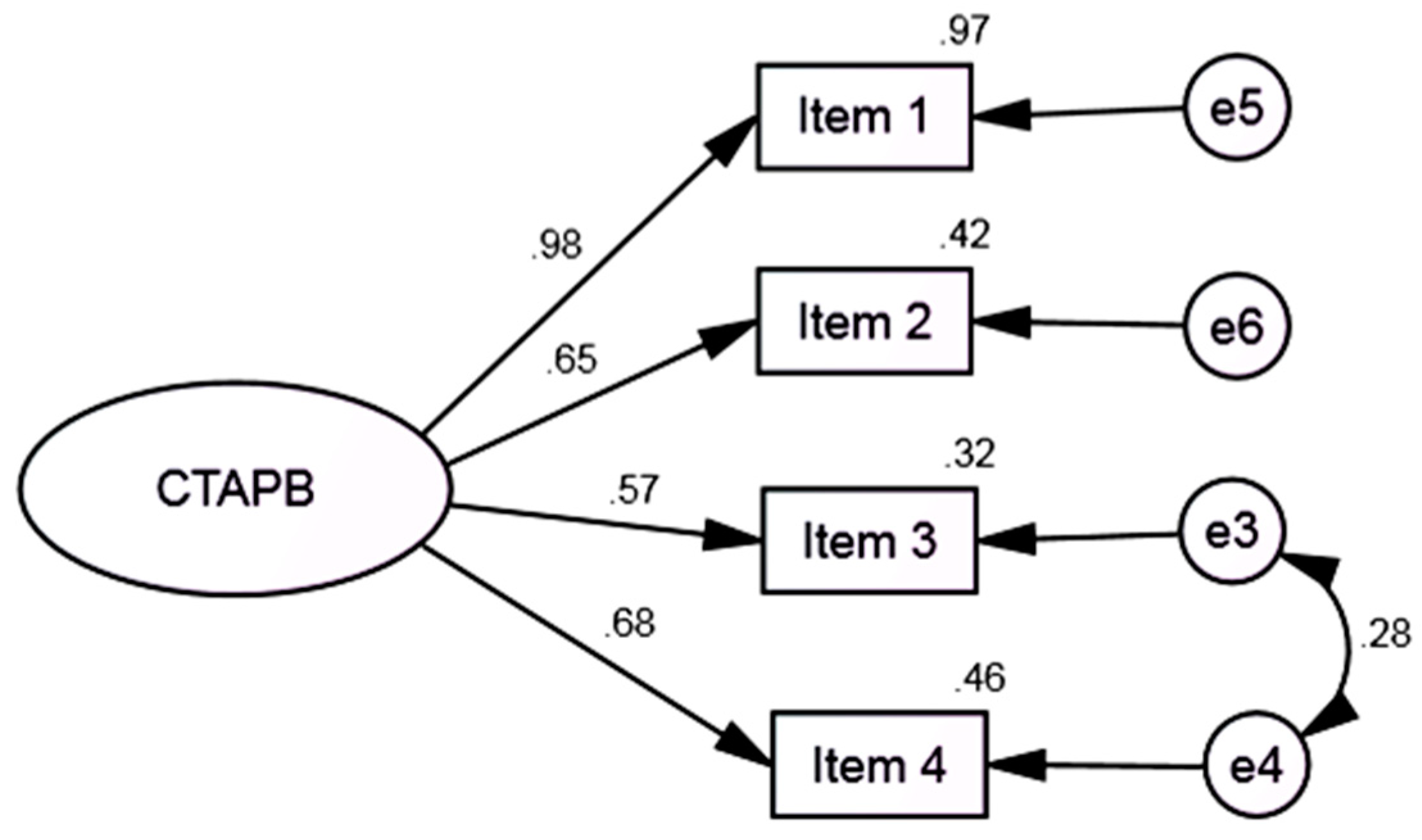

3.2.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.2.2. Size of Phenomenon

3.3. Study 3: The Familiarity of the Balance Doctrine among Jordanian Muslim Youth

4. Discussion and Directions for Future Research

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Study 1: CTAP Belief among Jordanian Muslim Youth

5.1.1. Participants and Procedures

5.1.2. Measures

5.1.3. Analytic Approach

5.2. Study 2: CTAP Belief among Malaysian Muslim Youth

5.2.1. Participants and Procedures

5.2.2. Measures

5.3. Study 3: The Familiarity of the Balance Doctrine among Jordanian Muslim Youth

5.3.1. Participants and Procedures

5.3.2. Measures

- Have you ever heard about the story of the People of the Heights in the Holy Qur’an? (Yes, No).

- Do you know who the People of the Heights are? (Yes, No).

- What is the source of your information about the People of the Heights story (you can specify more than one answer)? (School, Home, Media, Social media, and other)

- The People of the Heights are those whose: a—Good deeds are greater than their bad deeds. b—Good deeds are less than their bad deeds. c—Good deeds were equal to their bad deeds. d—I don’t know.

- According to the story, do the People of the Heights enter the fire of Hell? (Yes, No, I don’t know).

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdel-Khalek, Ahmed, and Joaquin Tomas-Sabado. 2005. Anxiety and death anxiety in Egyptian and Spanish nursing students. Death Studies 29: 157–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Khalek, Ahmed, David Lester, John Maltby, and Joaquin Tomas-Sabado. 2009. The Arabic scale of death anxiety: Some results from east and west. OMEGA Journal of Death and Dying 59: 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Khalek, Ahmed. 2002. Why do we fear death? The construction and validation of the reasons for death fear scal. Death Studies 26: 669–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Khalek, Ahmed. 2005. Death Obsession in Arabic and Western Countries. Psychological Reports 97: 138–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hilali, Muhammad, and Muhammad Khan. 1997. The Noble Al-Quran. English Translation of the Meaning and Commentary. Madinah: King Fahd Complex for Printing the Holy Quran. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Issa, Riyad, Steven Krauss, Samsilah Roslan, and Haslinda Abdullah. 2021. The Relationship between Afterlife Beliefs and Mental Wellbeing among Jordanian Muslim Youth. Journal of Muslim Mental Health 15: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Izz, Ali. 2000. Commentary on the Creed of at-Tahawi. Translated by Muhammad Abdul Haqq Ansari. Riyadh: Al-Imam Muhammad Ibn Sa’ud Islamic University. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qudai, Abu Talib. 2006. Tahrir al-maqal fi muwazanat al-’amal wa-hukm ghayr al-mukalafin fi al-oqbaa wa-lma’al. [“A Discourse Written on the Scale of Deeds “The Balancing of Good and Bad Deeds”, and the Judgment for the Unaccountable Persons in the Doomsday]. Abu Dhabi: Dar Imam Malik. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qurtubi, Muhammad. 2004. Al-Tadhkirah fī Aḥwāl al-Mawtá wa-Umūr al-Ākhirah. [Reminder of the Conditions of the Dead and the Matters of the Hereafter]. Riyadh: Dar Al-Menhaj. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Taftazani, Sa’ad al-Din. 1989. Sharh al-Maqasid [Explanation of Purposes, A Commentary of Islamic Creed]. Beirut: Aalam Alkutub, vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Alvard, Michael. 2004. Good hunters keep smaller shares of larger pies. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 27: 560–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Gary. 2009. Sin: A History. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arrunada, Benito. 2010. Protestants and Catholics: Similar Work Ethic, Different Social Ethic. The Economic Journal 120: 890–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baron, Jonathan, and Joan Miller. 2000. Limiting the scope of moral obligations to help: A cross-cultural investigation. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 31: 703–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baron, Jonathan. 1993. Heuristics and biases in equity judgments: A utilitarian approach. In Psychological Perspectives on Justice: Theory and Applications. Edited by Barbara Mellers and Jonathan Baron. London: Cambridge University Press, pp. 109–37. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, Justin, and Frank Keil. 1996. Anthropomorphism and God concepts: Conceptualizing a non-natural entity. Cognitive Psychology 31: 219–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barrett, Justin, and Rebekah Richert. 2003. Anthropomorphism or preparedness? Exploring children’s god concepts. Review of Religious Research 44: 300–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, Justin. 1998. Cognitive constraints on Hindu concepts of the divine. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 37: 608–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, Justin. 1999. Theological correctness: Cognitive constraint and the study of religion. Method & Theory in the Study of Religion 11: 325–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, Justin. 2007. Cognitive science of religion: What is it and why is it? Religion Compass 1: 768–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, Justin. 2011. Cognitive science of religion: Looking back, looking forward. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 50: 229–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, Justin. 2017. Religion Is Kids Stuff: Minimally Counterintuitive Concepts Are Better Remembered by Young People. In Religious Cognition in China: “Homo Religiosus” and the Dragon. Edited by Ryan Hornbeck, Justin Barrett and Madeleine Kang. Cham: Springer, pp. 125–37. [Google Scholar]

- Barro, Robert, and Rachel McCleary. 2003. Religion and Economic Growth. NBER Working Paper No. 9682, National Bureau of Economic Research. Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w9682 (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- Baumard, Nicolas, and Pascal Boyer. 2013. Explaining moral religions. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 17: 272–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumard, Nicolas, and Coralie Chevallier. 2012. What goes around comes around: The evolutionary roots of the belief in immanent justice. Journal of Cognition and Culture 12: 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baumard, Nicolas, and Pierre Lienard. 2011. Second or third party punishment? When self interest hides behind apparent functional interventions. Proceedings National Academic Science USA 108: 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baumard, Nicolas, Olivier Mascaro, and Coralie Chevallier. 2011. Preschoolers are able to take merit into account when distributing goods. Developmental Psychology 48: 492–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baumard, Nicolas. 2010. Has punishment played a role in the evolution of cooperation? A critical review. Mind & Society 9: 171–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelen, Alexander, Erik Sørensenab, and Bertil Tungoddenac. 2010. Responsibility for What? Fairness and Individual Responsibility. European Economic Review 54: 429–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carlsmith, Kevin, John Darley, and Paul Robinson. 2002. Why do we punish? Deterrence and just deserts as motives for punishment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 83: 284–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, Alex, and Cristina Bicchieri. 2013. Third-party sanctioning and compensation behavior: Findings from the ultimatum game. Journal of Economic Psychology 39: 268–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chittick, William. 2008. Muslim eschatology. In The Oxford Handbook of Eschatology. Edited by Jerry Walls. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 132–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Margaret, and Sarah Jordan. 2002. Adherence to communal norms: What it means, when it occurs, and some thoughts on how it develops. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development 95: 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church. 2005. What Is Purgatory? Available online: https://www.vatican.va/archive/compendium_ccc/documents/archive_2005_compendium-ccc_en.html#I%20Believe%20in%20the%20Holy%20Spirit (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Dastmalchian, Amir. 2017. Islam. In The Palgrave Handbook of the Afterlife. Edited by Yujin Nagasawa and Benjamin Matheson. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 153–73. [Google Scholar]

- De Cruz, Helen. 2013. Cognitive Science of Religion and the Study of Theological Concepts. Topoi 33: 487–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eire, Carlos. 2010. A Very Brief History of Eternity. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Lee, Eshah Wahab, and Malini Ratnasingan. 2013. Religiosity and fear of death: A three nation comparison. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 16: 179–99. [Google Scholar]

- Ghayas, Saba, and Syeda Shahida Batool. 2017. Construction and Validation of Afterlife Belief Scale for Muslims. Journal of Religion and Health 56: 861–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, Nima, P. J. Watson, Ghramaleki Framarz, Morris Ronald, and Hood Ralph. 2002. Muslim-Christian religious orientation scales: Distinctions, correlations, and cross-cultural analysis in Iran and the United States. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 12: 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, Nima, P. J. Watson, and Shahmohamadi Khadijeh. 2008. Afterlife Motivation Scale: Correlations with maladjustment and incremental validity in Iranian Muslims. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 18: 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, William, and David Schroeder. 2015. Gaining the Big Picture: Prosocial Behavior as an End Product. In The Oxford Handbook of Prosocial Behavior. Edited by David A. Schroeder and William G. Graziano. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 721–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, Paul. 2008. Purgatory. In The Oxford Handbook of Eschatology. Edited by Jerry Walls. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 427–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, Sebastian. 2020. Eschatology and the Qur’an. In The Oxford Handbook of Qur’anic Studies. Edited by Mustafa Shah and Muhammad Abdel Haleem. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gurven, Michael. 2004. To give and to give not: The behavioral ecology of human food transfers. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 27: 543–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hamza, Feras. 2016. Temporary Hellfire Punishment and the Making of Sunni Orthodoxy. In Eschatology and Concepts of the Hereafter in Islam. Edited by Sebastian Günther and Toff Lawson. Leiden: Brill, pp. 371–406. [Google Scholar]

- Hermida, Richard. 2015. The problem of allowing correlated errors in structural equation modeling: Concerns and considerations. Computational Methods in Social Sciences 3: 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge, Mitch. 2011. On imagining the afterlife. Journal of Cognition and Culture 11: 367–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoebel, Adamson. 1964. The Law of Primitive Man: A Study in Comparative Legal Dynamics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn ʿAshūr, Muammad al-Tahir. 1984. al-Taḥrīr wa-’l-tanwir. Tunis: Al-Daral-Tunisiyya li’l-Nashr, vol. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn Ḥazm, al-Andalusi. 1903. Al-Fisal fi al-Milal wa-al-Nihal [The Separator Concerning Religions, and Sects]. Cairo: Al-Khanji Library, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn Ḥazm, al-Andalusi. 1981. Rasa’i Ibn Hazm Al-’andalusi [Letters of Ibn Hazm Al-Andalusi]. Beirut: Arab Institute for Research & Publishing, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn Ḥazm, al-Andalusi. 2005. Risalat al-Talkhis fi wujuh al-takhllis. [A Concise Epistle on the Ways toward Salvation]. Riyadh: Dar Ibn Hazm. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn Kathir, Abu al-Fida’. 1997. Al-Bidāya wa-al-Nihāya [The Beginning and The End]. Cairo: Hagar, vol. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn Qayyim, al-Jawziyya. 1974. Tariq al-hijratayn wa-bab al-sa’adatayn [The Road of the Two Migrations and the Gate Leading to Two Joys]. Cairo: Al-dar al-salafiyah. [Google Scholar]

- Ibn Rajab, Abu al-Faraj. 2001. Jami’ al-’Ulum wa-l-Hikam fi Sharh khamsina Hadithan min Jawami al-Kalim [The Compendium of Knowledge and Wisdom in the Explanation of Fifty from the Words Concise]. Beirut: Alrisalah. [Google Scholar]

- Jakiela, Pamela. 2015. How fair shares compare: Experimental evidence from two cultures. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 118: 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnson, Dominic. 2009. The error of God: Error management theory, religion, and the evolution of cooperation. In Games, Groups, and the Global Good. Edited by Simon A. Levin. Cham: Springer, pp. 169–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanngiesser, Patricia, Nathalia Gjersoe, and Bruce Hood. 2010. The effect of creative labor on property ownership transfer by preschool children and adults. Psychological Science 21: 1236–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Harold, and Arndt Bussing. 2010. The Duke University Religion Index (DUREL): A five-item measure for use in epidemiological studies. Religions 1: 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Konow, James. 2000. Fair shares: Accountability and cognitive dissonance in allocation decisions. American Economic Review 90: 1072–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lange, Christian. 2013. Ibn Ḥazm on Sins and Salvation. In Ibn Ḥazm of Cordoba: The Life and Works of a Controversial Thinker. Edited by Camilla Adang, Maribel Fierro and Sabine Schmidtke. Leiden: Brill, pp. 429–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, James. 1994. Encyclopedia of Afterlife Beliefs and Phenomena. Detroit: Gale. [Google Scholar]

- Lugo, Luis. 2010. Tolerance and tension: Islam and Christianity in Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, Gordon, Adam Swift, David Routh, and Carole Burgoyne. 1999. What is and what ought to be: Popular beliefs about distributive justice in thirteen countries. European Sociological Review 15: 349–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCleary, Rachel. 2007. Salvation, damnation, and economic incentives. Journal of Contemporary Religion 22: 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minois, Georges. 1994. Histoire de l’Enfer [History of Hell]. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, Gareth, and Tina McAdie. 2009. Are personality, well-being and death anxiety related to religious affiliation? Mental Health, Religion and Culture 12: 115–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nähri, Jani. 2008. Beautiful reflections: The cognitive and evolutionary foundations of paradise representations. Method and Theory in the Study of Religion 20: 339–65. [Google Scholar]

- Nakissa, Aria. 2020a. The Cognitive Science of Religion and Islamic Theology: An Analysis based on the Works of al-Ghazālī. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 88: 1087–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakissa, Aria. 2020b. Cognitive Science of Religion and the Study of Islam: Rethinking Islamic Theology, Law, Education, and Mysticism Using the Works of al-Ghazālī. Method & Theory in the Study of Religion 32: 205–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, Shaun. 2004. Is Religion What We Want? Motivation and the Cultural Transmission of Religious Representations. Journal of Cognition and Culture 4: 347–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pew Research Center. 2021. Religion in India: Tolerance and Segregation. June 29. Available online: https://www.pewforum.org/2021/06/29/religion-in-india-tolerance-andsegregation/ (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- Pyysiäinen, Ilkka. 2004. Intuitive and Explicit in Religious Thought. Journal of Cognition & Culture 4: 123–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Paul, Kurzban Robert, and Jones Owen. 2007. The origins of shared intuitions of justice. Vanderbilt Law Review 60: 1633–88. [Google Scholar]

- Roubekas, Nickolas. 2014. Whose Theology? The Promise of Cognitive Theories and the Future of a Disputed Field. Religion and Theology 20: 384–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, Marco, and Jessica Sommerville. 2011. Fairness expectations and altruistic sharing in 15-month-old human infants. PLoS ONE 6: e23223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafer, Grant. 2012. Al-Ghayb wa-l‘Akhirah: Heaven, Hell, and Eternity in the Quran. In Heaven, Hell, and the Afterlife: Eternity in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Edited by J. Harold Ellens. Westport: CT Praeger, vol. 3, pp. 9–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sloane, Stephanie, Renéeand Baillargeon, and David Premack. 2012. Do infants have a sense of fairness? Psychological Science 23: 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slone, Jason. 2004. Theological Incorrectness: Why Religious People Believe What They Shouldn’t. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sperber, Dan. 1996. Explaining Culture: A Naturalistic Approach. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Teiser, Stephen. 1994. The Scripture on the Ten Kings and the Making of Purgatory in Medieval Chinese Buddhism. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Upal, Afzal. 2005. Towards a Cognitive Science of New Religious Movements. Journal of Cognition and Culture 5: 214–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Elk, Michiel, Bastiaan Rutjens, and Frenk van Harreveld. 2017. Why Are Protestants More Prosocial Than Catholics? A Comparative Study among Orthodox Dutch Believers. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 27: 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walter, Tony. 1996. The Eclipse of Eternity: Sociology of the Afterlife. Basingstoke: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Chang-Da. 2018. Student enrolment in Malaysian higher education: Is there gender disparity and what can we learn from the disparity. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 48: 244–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Claire. 2016. The cognitive foundations of reincarnation. Method & Theory in the Study of Religion 28: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Claire. 2017. What the cognitive science of religion is (and is not). In Theory in a Time of Excess—The Case of the Academic Study of Religion. Edited by Aaron W. Hughes. London: Equinox Publishing, pp. 95–114. [Google Scholar]

- White, Claire. 2018. What Does the Cognitive Science of Religion Explain? In New Developments in the Cognitive Science of Religion. Edited by Hans van Eyghen, Rik Peel and Gijsbert van den Brink. Cham: Springer, pp. 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, Carol. 2006. Careless responding to reverse-worded items: Implications for confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 28: 189–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Factor Loading | Communalities |

|---|---|---|

| On the Day of Judgment (Resurrection), if a Muslim’s good deeds out-weigh his/her bad deeds, Allah will torment them in Hell and then will admit them to Paradise | 0.74 | 0.54 |

| On the Day of Judgment (Resurrection), if a Muslim’s good deeds out-weigh his/her bad deeds, Allah will forgive their sins and admit them to Paradise without being tormented in Hell (Rev.) | 0.71 | 0.51 |

| There is a promise from Allah that a Muslim whose good deeds outweigh their sins will enter Paradise without being tortured in Hell for their sins (Rev.) | 0.63 | 0.39 |

| I understand from the words of Allah “and whosoever has done an atom’s weight of evil will see it” that a Muslim will get punished for their sins in Hell even if their good deeds outweigh their sins | 0.76 | 0.57 |

| I understand from the words of Allah “There is not one of you but will pass over it (Hell)” that before a Muslim is admitted to Paradise, he/she will be punished for their sins in Hell even if their good deeds outweigh their sins | 0.76 | 0.58 |

| Model | χ2 | df | p | CMIN/DF | GFI | AGFI | CFI | TLI | NFI | RMSEA | PCLOSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.30 | 4 | 0.679 | 0.577 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.0 | 1.00 | 99 | 0.00 [0.00–0.06] * | 0.88 |

| 2 | 24.38 | 5 | 0.000 | 4.87 | 0.96 | 0.90 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.11 [0.07–0.16] | 0.009 |

| 3 | 18.36 | 2 | 0.000 | 9.18 | 0.97 | 0.85 | 0.96 | 0.89 | 0.96 | 0.16 [0.10–0.55] | 0.002 |

| 4 | 1.4 | 1 | 0.237 | 1.4 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.036 [0.00–0.16] | 0.39 |

| Familiarity of the Balance Doctrine | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | Total | |

| Do not believe in CTAP | 35 | 135 | 170 |

| Believe in CTAP | 9 | 38 | 47 |

| Total | 44 | 173 | 217 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Issa, R.S.; Krauss, S.E.; Roslan, S.; Abdullah, H. To Heaven through Hell: Are There Cognitive Foundations for Purgatory? Evidence from Islamic Cultures. Religions 2021, 12, 1026. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12111026

Al-Issa RS, Krauss SE, Roslan S, Abdullah H. To Heaven through Hell: Are There Cognitive Foundations for Purgatory? Evidence from Islamic Cultures. Religions. 2021; 12(11):1026. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12111026

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Issa, Riyad Salim, Steven Eric Krauss, Samsilah Roslan, and Haslinda Abdullah. 2021. "To Heaven through Hell: Are There Cognitive Foundations for Purgatory? Evidence from Islamic Cultures" Religions 12, no. 11: 1026. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12111026

APA StyleAl-Issa, R. S., Krauss, S. E., Roslan, S., & Abdullah, H. (2021). To Heaven through Hell: Are There Cognitive Foundations for Purgatory? Evidence from Islamic Cultures. Religions, 12(11), 1026. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12111026