The Background of Stone Pagoda Construction in Ancient Japan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Unusual Ancient Stone Pagodas

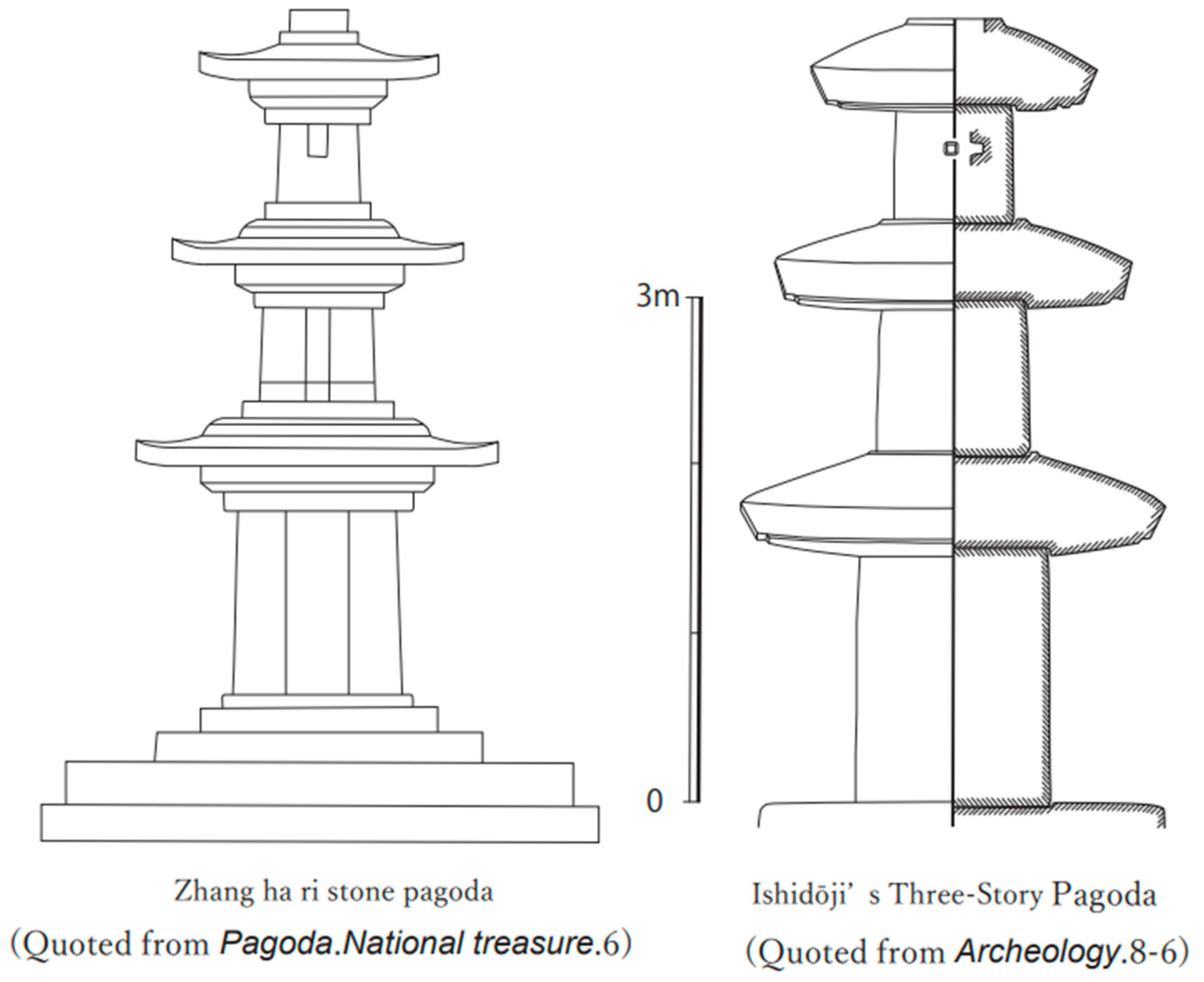

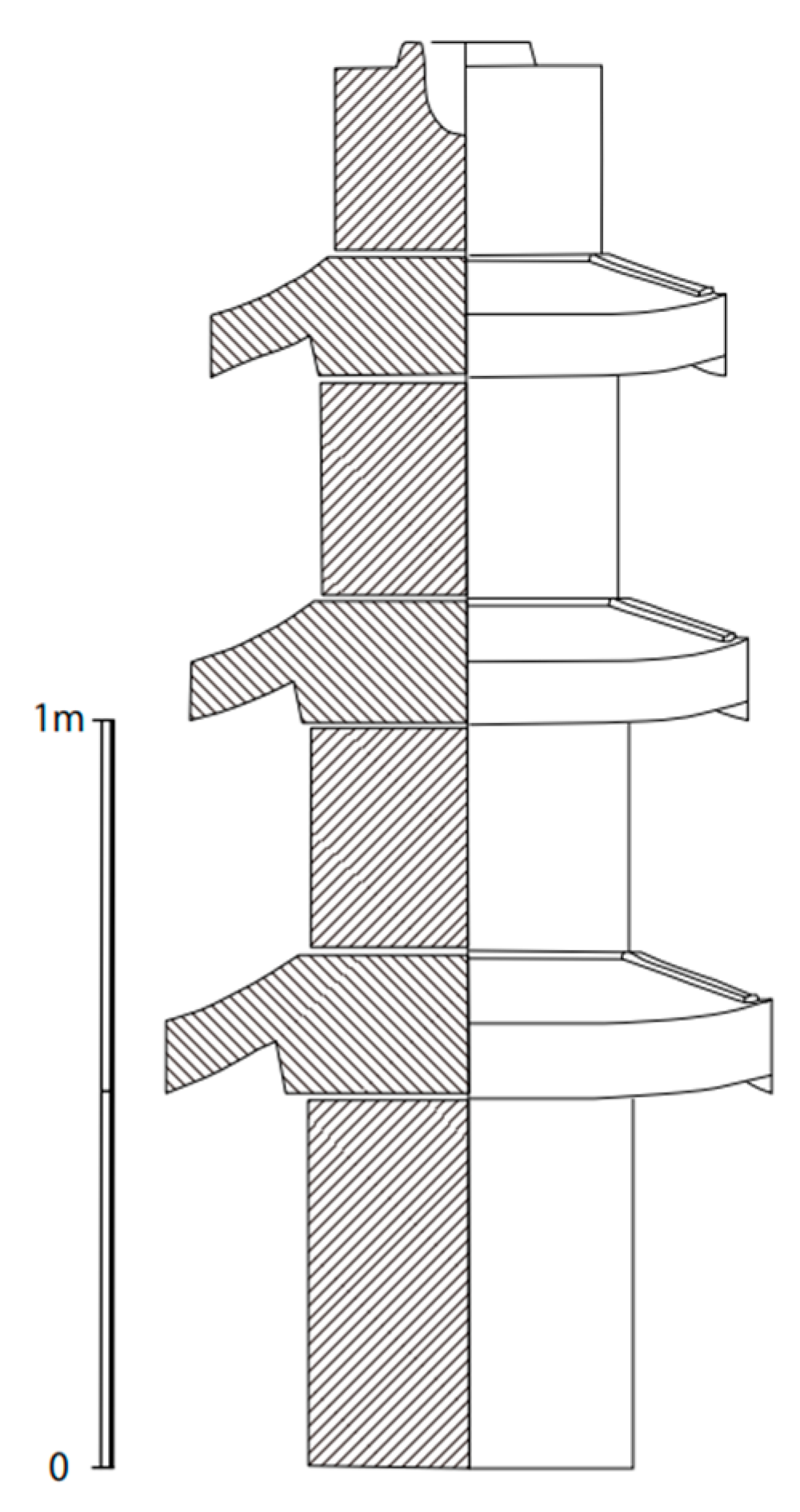

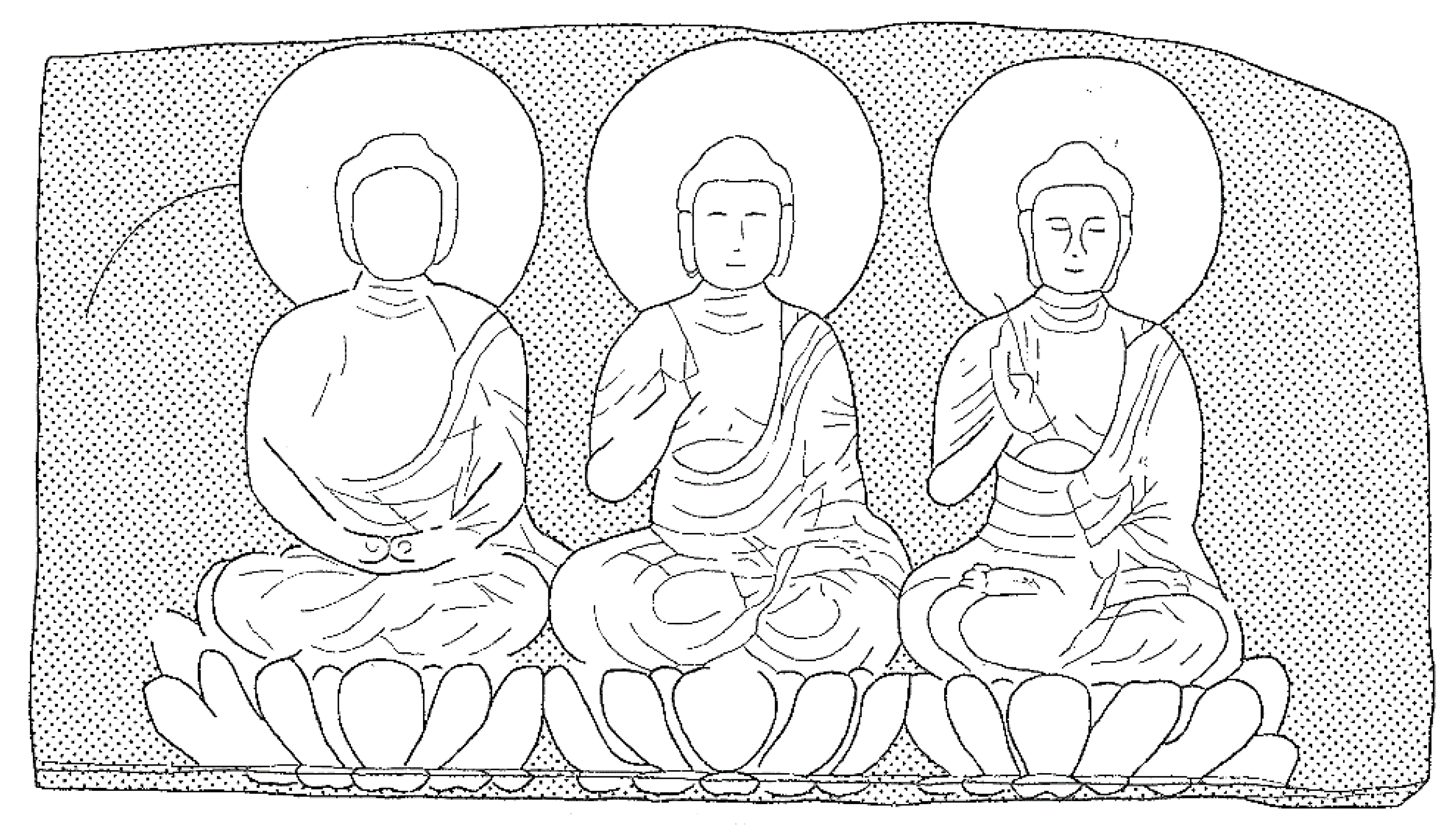

2.1. Ishidōji’s Three-Story Pagoda

2.2. Okamasu Ishindō

3. Other Ancient Stone Pagodas

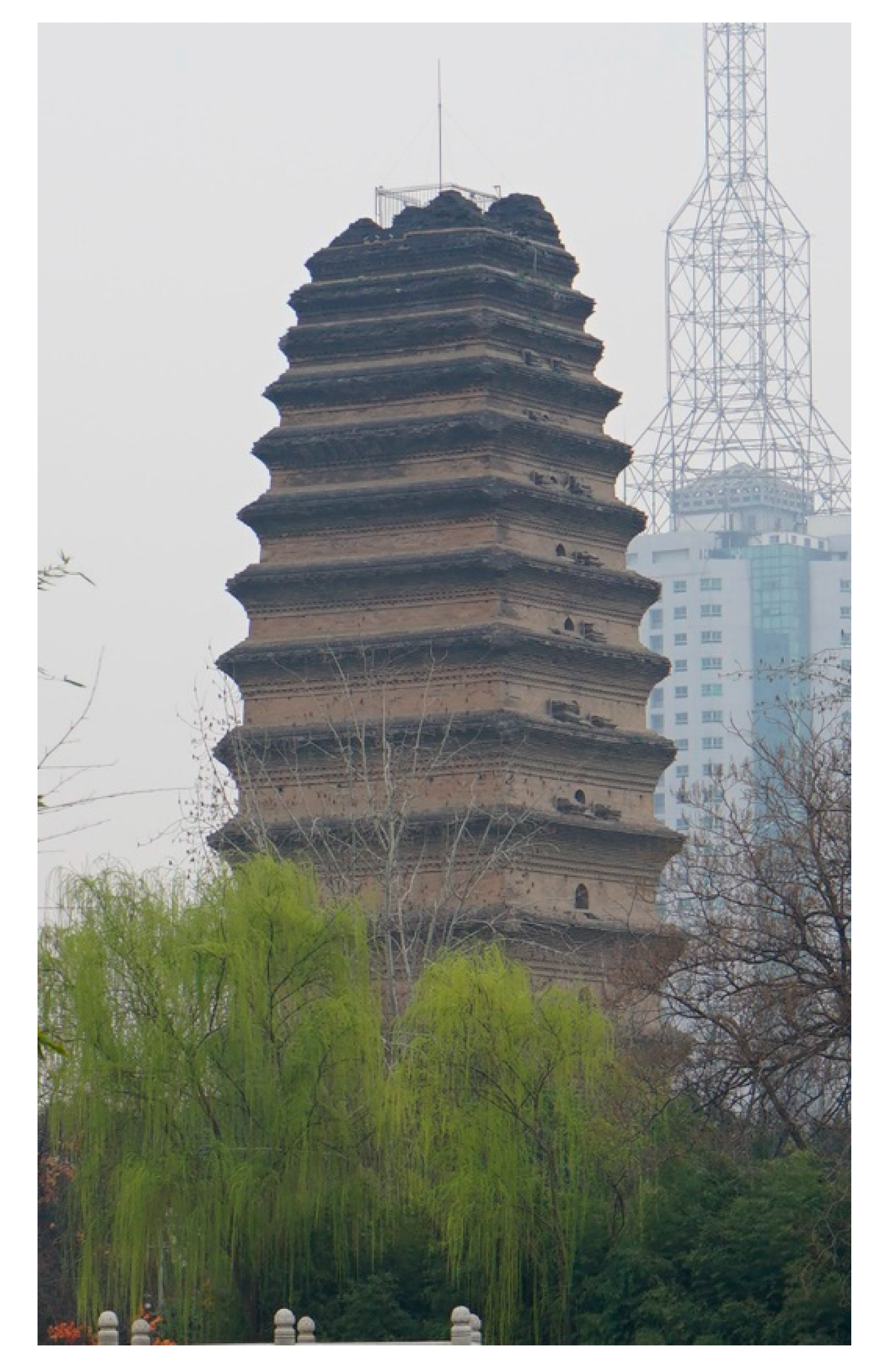

4. The 13-Story Pagoda at the Rokutanji Ruins and the Background of Its Creation

5. The Adoption of Stone Pagodas in Ancient Japan

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | An entry for the third month of Monmu 4 (700; 56th year of the sexagenary cycle) in Zoku Nihonki 続日本紀 states that many of the scriptures brought by Dōshō were stored at Zen’in 禅院 in the Heijō-kyō’s Sakyō area, which was the predecessor of Tōnan Zenin 東南禅院. |

References

- Fujisawa, Kazuo 藤澤一夫. 1985. Santai Mirokuzō o honzon to suru Nihon kodai jiin: Kin Samuyuon sensei no kakō o ga shite 三体弥勒像を本尊とする日本古代寺院-金三龍先生の華甲を賀して- [Japan’s ancient temples with Miroku triads as the main object of veneration: Celebrating the sixty-first birthday of Kim Samryong-sensei]. In Han’guk munhwa wa wŏn Pulgyo sasang: Munsan Kim Sam-nyong Paksa hwagap kinyŏm 韓國 文化 와 圓佛教思想: 文山 金 三龍 博士 華甲 紀念 [Korean Culture and Won Buddhist Thought: Marking the Sixty-First Birthday of the Prolific Writer Dr. Kim Sanryong]. Iri-si: Wŏn’gwang Taehakkyo Ch’ulp’anbu, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuzawa, Kunio 福澤邦夫. 2002. Shinano Shinonoi shozai kosekitō no yōshiki 信濃篠井所在古石塔の様式 [The styles of ancient stone pagodas in Shinano’s Shinonoi]. In Fujisawa Kazuo sensei sotsuju kinen ronbunshū 藤澤一夫先生卒寿記念論文集 [Article Collection Marking the Ninetieth Birthday of Fujisawa Kazuo-Sensei]. Nara: Tezukayama Daigaku Kōkogaku Kenkyūjo, pp. 452–62. [Google Scholar]

- Futaba, Kenkō 二葉憲香. 1957. Taika no kaishin no shūkyō kōzō. 大化改新の宗教構造 [The Religious structure of the Taika Reforms]. Bukkyō shigaku. 仏教史学 [Buddhism History] 6: 171–98. [Google Scholar]

- Gamōmachi Kokusai Shinzen Kyōkai 蒲生町国際親善協会, ed. 2000. Ishidōji sanjū sekitō no rūtsu o saguru 石塔寺三重石塔のルーツを探る [Exploring the Roots of Ishidōji’s Three-Story Stone Pagoda]. Hikone: Sanraizu Shuppan. [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara, Hajime 萩原哉. 2007. Sanzebutsu no zōzō: Shōzan sekkutsu dai 3 gō kutsu no sanbutsu o chūshin to shite 三世仏の造像-鐘山石窟第3号窟の三仏を中心として [Visualizing the buddhas of the three times: The three buddhas at Zhongshan Cave No. 3]. Indo bukkyōgaku kenkyū 印度仏教学研究 [Indian and Buddhist Studies] 56: 489–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hishida, Tetsuo 菱田哲郎. 2013. Hakusuki no e igō Nihon no bukkyō jiin ni mirareru Kudara imin no eikyō 白村江以後日本の仏教寺院に見られる百済遺民の影響 [The influence of Baekje survivors seen in Buddhist temples of Japan from Baekgang onwards]. Dongyang misulsahak 동양미술사학 [Journal of Asian art History] 2: 32–75. [Google Scholar]

- Honma, Takehito 本間岳人. 2021. Yamagami tajūtō shōkō 山上多重塔小考 [Some thoughts on the Yamagami multi-story pagoda]. Hibiki 日引 [Hibiki] 16: 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Inaba Man’yō Rekishikan 因幡万葉歴史館, ed. 2006. Okamasu Ishindō: Ima, Toikakeru Mono 岡益石堂いま、問いかけるもの [Okamasu Ishindō: What It Asks Us Now]. Tottori: Inaba Man’yō Rekishikan. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, Kaoru 井上薫. 1982. Izumi no kuni Ōnodera dotō no genryū 和泉国大野寺土塔の源流 [The origins of the earthen pagoda of Ōnodera temple in Izumi Province]. Bunkazai gakuhō文化財学報 [Cultural Properties Academic Bulletin] 1: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Iwanaga, Shōzō 岩永省三, ed. 2001. Shiseki zutō hakkutsu chōsa hōkoku 史跡頭塔発掘調査報告 [Report of the Zutō Historical Site Excavation]. Nara: Nara Kokuritsu Bunkazai Kenkyūsho 奈良国立文化財研究所 [Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties]. [Google Scholar]

- Kasano, Tsuyoshi 笠野 毅, Fukuo Masahiko 福尾正彦, Nakahara Hitoshi 中原斉, Yamamasu Masayoshi 山枡雅美, and Tsugawa Hitomi 津川ひとみ. 1999. Ubenoryōbo sankō chinai ‘Okamasu no Ishindō’ no hozon shori chōsa hōkoku 宇倍野陵墓参考地内「岡益の石堂」の保存処理・調査報告 [Report on Preservation Measures for and Survey of Ubeno Imperial Mausoleum Reference Site’s ‘Okamasu Ishindō’]. Shoryōbu kiyō 書陵部紀要 [Archives and Mausolea Department Bulletin]. Tokyo: Archives and Mausolea Department, p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- Kawakatsu, Masatarō 川勝政太郎. 1957. Nihon sekizai kōgeishi 日本石材工芸史 [The History of Japanese Stone Craftwork]. Kyōto: Sōgeisha. [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi, Hiroki 菊地大樹. 2020. Nihonjin to yama no shūkyō 日本人と山の宗教 [Japanese People and Mountain Religion]. Tōkyō: Kōdansha Gendai Shinsho. [Google Scholar]

- Kishi, Kumakichi 岸熊吉, and Suenaga Masao 末永雅雄. 1955. Uda-gun Murō-Mura Murōji Nyoimine Shutsudo ibutsu [Artifacts Unearthed from Mt. Nyoi at Murōji temple in Uda District’s Murō Village]. Nara-ken Shiseki Meishō Tennen Kinenbutsu chōsa shōhō 奈良県史跡名勝天然記念物調査抄報 5 [Report on Nara Prefecture Historical Site and Famous Natural Monument Surveys] 5. Nara: Naraken Kyōiku Iinkai奈良県教育委員会 [Nara Prefectural Board of Education]. [Google Scholar]

- Kokuritsu Rekishi Minzoku Hakubutsukan 国立歴史民俗博物館. 1997. Kodai no hi 古代の碑 [Ancient Period Monuments]. Chiba: National Museum of Japanese History. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, Tomoyoshi 松田朝由, and Hiroshi Kaibe 海邉博史. 2009. Shikoku no kodai sōtō 四国の古代層塔 [Shikoku’s ancient multi-story pagodas]. Kagawa kōko 香川考古 [Kagawa Archaeology] 11: 75–94. [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno, Masayoshi 水野正好. 2006. Okamasu no Ishindō kara sugata naki tō o okangaeru 岡益の石堂から姿なき塔を考える [Thinking about Absent Pagodas from Okamasu’s Ishindō]. Tottori: Inaba Man’yō Rekishikan, pp. 48–66. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, Akira 森 章. 1994. Iwatakiyama sanjū sekitō: Tsūshō ‘Shakutō-sama’ no seisaku nendai 岩滝山三重石塔-通称<釈塔様>の制作年代 [The time of creation of the three-story pagoda of Iwatakiyama, commonly known as the Śākyamuni pagoda]. Shiseki to bijutsu 史迹と美術 [Historical Sites and Art] 650: 396–407. [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura, Tei 西村貞. 1942. Nara no sekibutsu 奈良の石仏 [Nara’s Stone Buddhist Figures]. Ōsaka: Zenkoku Shobō. [Google Scholar]

- Nomura, Takashi 野村隆. 1985. Ōmi Ishidōji sanjū sekitō no sōritsu nendai 近江石塔寺三重石塔の造立年代 [The time of the creation of Ōmi Ishidō’s three-story stone pagoda]. Shiseki to bijutsu 史迹と美術 [Historical Sites and Art] 55: 342–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ogasawara, Yoshihiko 小笠原好彦. 1992. Ōmi no bukkyō bunka 近江の仏教文化 [Ōmi’s Buddhist culture]. In Kodai o kangaeru: Ōmi 古代を考える近江 [Thinking about the Ancient Period: Ōmi]. Edited by Mizuno Masayoshi 水野正好. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, pp. 156–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sagawa, Shin’ichi 狭川真一. 2006. Okamasu Ishindō to kodai no sekitō 岡益石堂と古代の石塔 [Okamasu Ishindō and Ancient Stone Pagodas]. Tottori: Inaba Man’yō Rekishikan, pp. 88–116. [Google Scholar]

- Sagawa, Shin’ichi 狭川真一. 2018. Enichiji-den Tokuitsu-byō gojū sekitō no saifukugen 慧日寺伝徳一廟五重石塔の再復原 [Re-restoration of the Enichiji temple Tokuitsu mausoleum five-story stone pagoda]. In Gankōji Bunkazai Kenkyūsho kenkyū hōkoku元興寺文化財研究所研究報告 [Gangoji Institute for Research of Cultural Property Research Report]2017. Nara: Gangoji Institute for Research of Cultural Property, pp. 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Sagawa, Shin’ichi 狭川真一. 2021. Kodai no sekizōbutsu 古代の石造物 [Ancient stonework]. Hibiki 日引 [Hibiki] 16: 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai, Toshio, and Fujisawa Fumihiko. 1989. Basic Planning of the Stone Pagoda at Ryufukji-Temple in Asuka. Journal of the Faculty of Science and Technology, Kinki University 25: 251–59. [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu, Toshiaki 清水俊明. 1984. Nara-ken shi 奈良県史 [History of Nara Prefecture]. vol. 7. Sekizō bijutsu 石造美術 [Stone Art]. Tōkyō: Meicho Shuppan. [Google Scholar]

- Sonoda, Kōyū 園田香融. 1981. Heian bukkyō no kenkyū 平安仏教の研究 [Research on Heian Buddhism]. Kyoto: Hōzōkan. [Google Scholar]

- Takei, Akio 竹居明男. 1980. Butsumyōe ni kansuru sho mondai: Jū seiki matsu made no dōkō (jō) 仏名会に関する諸問題-十世紀末までの動向-(上) [Various issues related to buddha name recitation rituals: Developments up through the end of the tenth century (part 1)]. Jinbungaku 人文学 [Studies in humanities, Doshisha University] 135: 21–46. [Google Scholar]

- Takei, Narumi 武井成実. 2021. Chūbu chihō no kodai sekizōbutsu: Nagano-shi Shinonoi shozai no sekizō tasōtō [Ancient stonework of the Chūbu region: A multi-story stone pagoda in Nagano city’s Shinonoi. Hibiki 日引 [Hibiki] 16: 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Taketani, Toshio 竹谷俊夫. 1989. Kawachi Rokutanji ato shutsudo no ibutsu 河内鹿谷寺址出土の遺物 [Artifacts unearthed from the site of Rokutanji temple in Kawachi]. Kobunka dansō 古文化談叢 [Plethora of Ancient Culture Topics] 20: 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Tottori-ken Maizō Bunkazai Sentā 鳥取県埋蔵文化財センター. 2000. Okamasu haiji 岡益廃寺. [Okamasu Abandoned temple]. Kokufu Town (Tottori Prefecture): Tottori Prefecture Embedded Cultural Properties Center. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, Masateru 山口正晃. 2018. “Chūgoku bukkyō” no kakuritsu to butsumyōkyō 「中国仏教」の確立と仏名経 [The establishment of “Chinese Buddhism” and buddhas’ names sutras]. Kansai Daigaku Tōzaigakujutsu Kenkyūsho kiyō 関西大学東西学術研究所紀要 [Bulletin of Kansai University’s Institute of Oriental and Occidental Studies] 51: 233–59. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, Yoshitaka 山本義孝. 1993. Nijōsanroku no sekkutsu jiin: Rokutanji, Iwaya no shiryōka to haikei 二上山麓の石窟寺院-鹿谷寺・岩屋の資料化と背景- [Stone cave temples at the foot of Mt. Nijō: Turning Rokutanji and Iwaya into materials and their background]. Shigaku ronsō 史学論叢 [Historical studies review of Beppu University] 23: 17–41. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, Jun 山本潤. 2018. “Kodai ni okeru keka no juyō no hen’yō: Zange kara shūzen e” 古代における悔過の受容と変容-懺悔から修善へ― [The adoption and transformation of transgression repentance in ancient times: From repentance to the cultivation of goodness]. Bukkyōshi kenkyū 仏教史研究 [Buddhism History Studies of Ryukoku University] 56: 26–54. [Google Scholar]

| № | Name of Pagoda | Period | Location | Type of Location | References | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ishidōji’s three-story pagoda | latter half of the 7th century | Shiga Prefecture’s city of Higashi Ōmi | Hills | (Gamōmachi Kokusai Shinzen Kyōkai 2000) | |

| 2 | Okamasu Ishindō | 7–9th century | Tottori Prefecture’s city of Tottori | Hills | (Inaba Man’yō Rekishikan 2006) | |

| 3 | Yamagami’s multistory pagoda | 801 | Gunma Prefecture’s city of Kiriu | Hills | (Honma 2021) | |

| 4 | Hōda pagoda | 9th century | Nagano Prefecture’s city of Nagano | Level ground | (Fukuzawa 2002; Takei 2021) | |

| 5 | Kannonji’s three-story pagoda | End of the 8th century | Kyoto Prefecture’s city of Kyōtanabe | Hills | Original position unknown | |

| 6 | Ōganji Temple’s multistory pagoda fragment | End of the 9th century | Nara Prefecture’s city of Nara | Mountain | (Shimizu 1984) | |

| 7 | Tōnomori’s hexagonal thirty-story pagoda | latter half of the 8th century | Nara Prefecture’s city of Nara | Mountain | (Shimizu 1984) | |

| 8 | Zutō’s multistory pagoda fragment | 8 or 9th century | Nara Prefecture’s city of Nara | Level ground | (Iwanaga 2001) | |

| 9 | Ryūfukuji temple’s five-story pagoda | 751 | Nara Prefecture’s town of Asuka | Hills | (Kokuritsu Rekishi Minzoku Hakubutsukan 1997) | Estimated position from inscription |

| 10 | Murōji temple’s wish-granting jewel pagoda | End of the 8th century | Nara Prefecture’s city of Uda | Mountain | (Kishi and Masao 1955) | |

| 11 | Rokutanji’s thirteen-story pagoda | Middle of the 8th century | Osaka Prefecture’s town of Taishi | Mountain | (Taketani 1989; Yamamoto 1993) | |

| 12 | Iwaya’s three-story pagoda | 8th century | Osaka Prefecture’s town of Taishi | Mountain | (Yamamoto 1993) | |

| 13 | Iwatakiyama’s multistory pagoda | 8 or 9th century | Okayama Prefecture’s city of Kurashiki | Hills | (Mori 1994) | |

| 14 | Zentsuji Tanjōin’s multistory pagoda | 9th century | Kagawa Prefecture’s city of Zentsuji | Level ground | (Matsuda and Kaibe 2009) | |

| 15 | Shusshakaji’s multistory pagoda | 9th century | Kagawa Prefecture’s city of Zentsūji | Mountain | (Matsuda and Kaibe 2009) | |

| 16 | Sanuki Kokufu excavated multistory pagoda | 8th century | Kagawa Prefecture’s city of Sakaide | Level ground | (Matsuda and Kaibe 2009) | |

| 17 | Enichiji’s multistory pagoda | 9th century | Fukushima Prefecture’s town of Bandai | Mountain | (Sagawa 2018) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Satō, A. The Background of Stone Pagoda Construction in Ancient Japan. Religions 2021, 12, 1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12111001

Satō A. The Background of Stone Pagoda Construction in Ancient Japan. Religions. 2021; 12(11):1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12111001

Chicago/Turabian StyleSatō, Asei. 2021. "The Background of Stone Pagoda Construction in Ancient Japan" Religions 12, no. 11: 1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12111001

APA StyleSatō, A. (2021). The Background of Stone Pagoda Construction in Ancient Japan. Religions, 12(11), 1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12111001